Submitted:

22 September 2024

Posted:

23 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Definitions

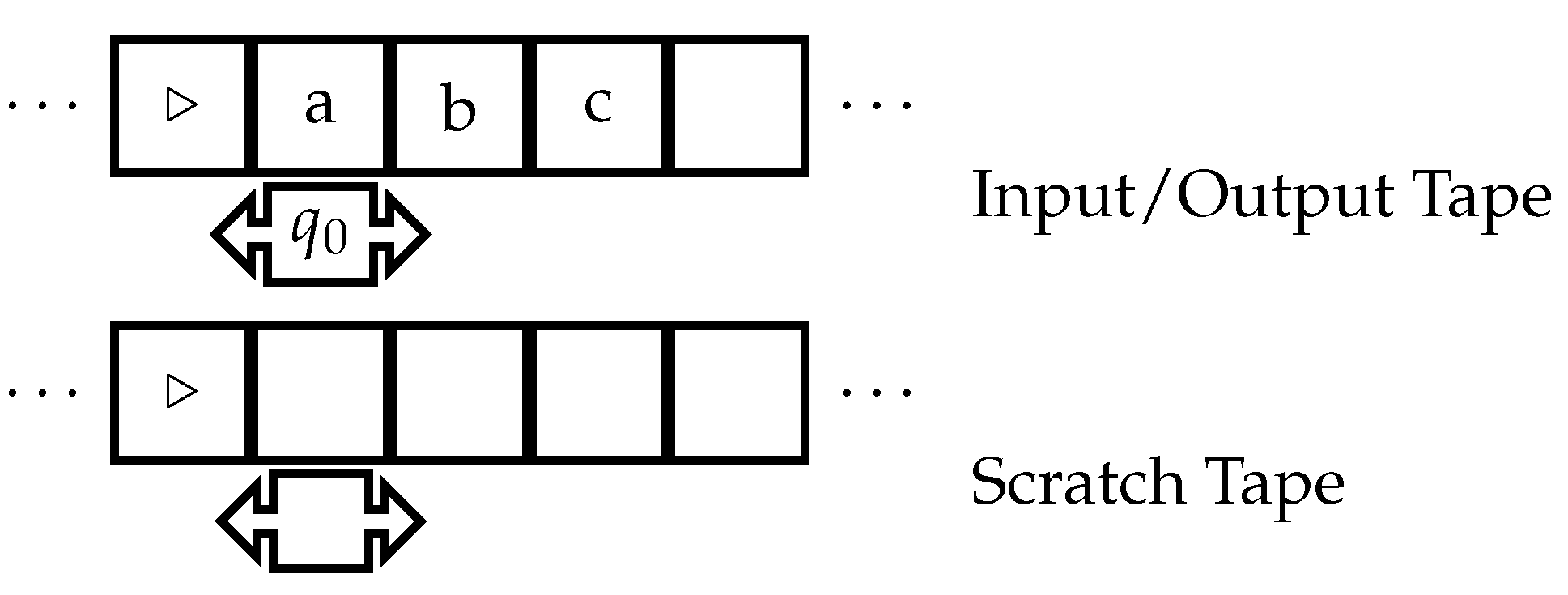

3.1. Traditional Turing Machines

- Tape alphabet , with blank symbol ⊔, start symbol ▹.

- Set of states Q, initial state , halting states .

- Tape heads, initially positioned at the leftmost cells.

- Transition function .

- Tape 1 contains the input in cells to the right of ▹. Other tapes have only ▹.

-

At each step:

- uses the current state q and symbols under the heads to determine the next state , write symbols , and head moves .

- Heads move left or right, according to . They cannot move left from ▹.

- Write unless it is ▹.

- Halting in state gives the output: non-blank contents of tape 1.

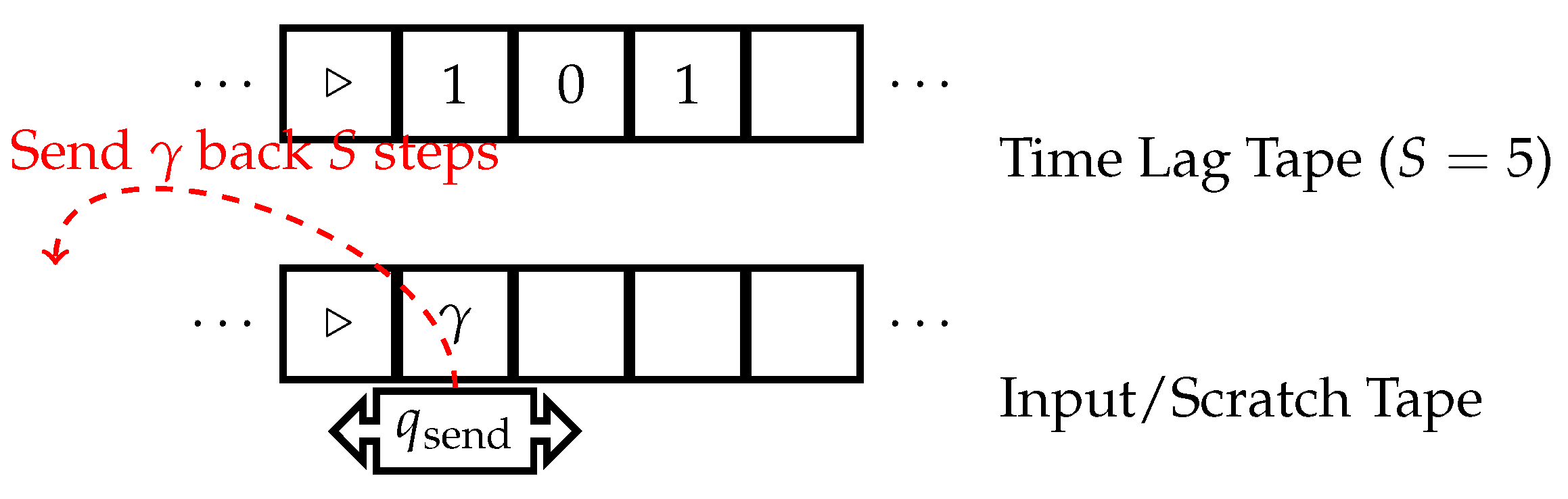

3.2. Single Symbol Time-Traveling Turing Machine

- Tape 1 holds a non-negative integer S in binary using all symbols except blank.

- Tape 2 holds the input and scratch workspace.

- Special internal state to send a symbol back in time.

- Computation proceeds as normal, except tape 1 holds the "time lag" S.

- Upon entering , the symbol under the tape 2 head is sent S steps back in time on tape 2.

- If the current timestep , the machine transitions to a special error state .

- Otherwise, is placed on tape 2 at the same position corresponding to past configuration in timestep , overwriting the symbol that was there.

- Computation continues in timestep from , potentially in a new timeline.

- As before, halting in H gives the output from tape 1.

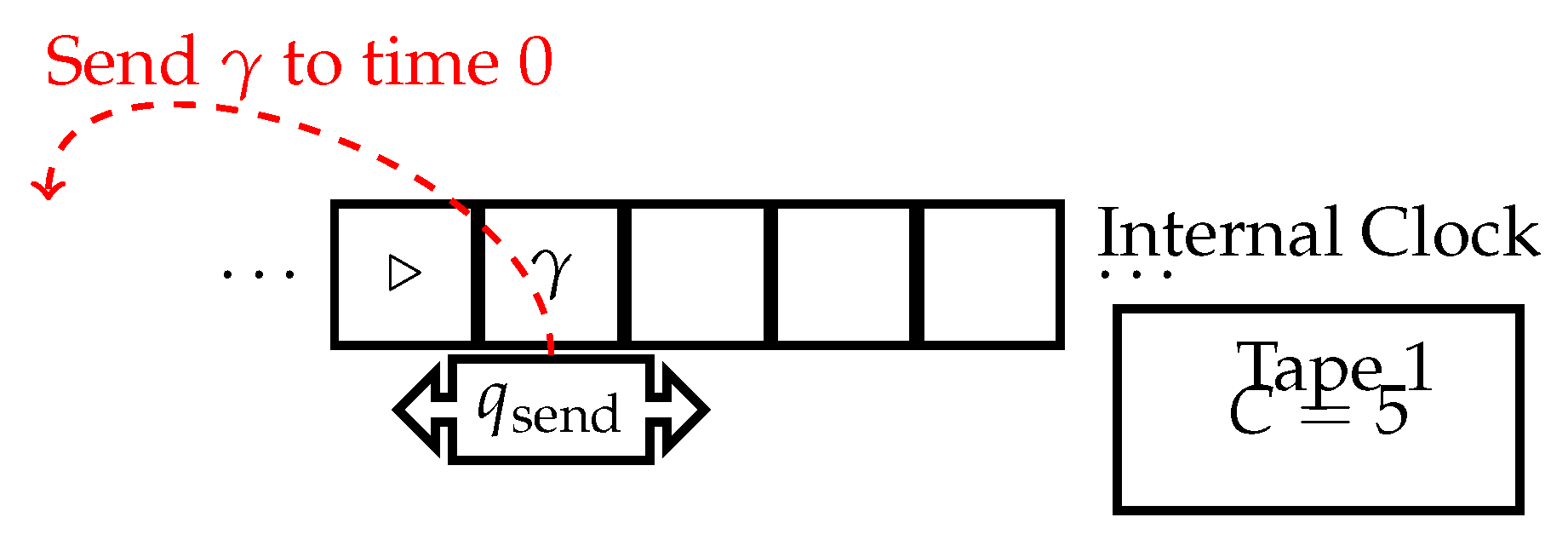

3.3. Internal Clock Time-Traveling Turing Machine

- Internal timestamp counter C incrementing at each step.

- Special state to optionally send the tape 1 symbol to time 0.

- C starts at 0 and increments at each timestep.

- Computation proceeds normally until optionally entering .

- Upon entering , the current tape 1 symbol is sent to the same tape position at time 0, overwriting what was there.

- Computation continues from .

- Halting gives the output on tape 1.

- has tape alphabet , where the additional symbols encode the tape contents, head position, and state of M at each step.

- has states , where is used for simulating M, is used for sending symbols back in time, is used for retrieving the sent symbol, and is used for writing the retrieved symbol to the simulated tape of M.

- has initial state and halting states .

- uses tape 1 for the time lag and tape 2 for simulating the tape of M and encoding the computational history.

- starts in state with input w on tape 2 and time lag S on tape 1.

- In state , simulates one step of M using the transition function . It updates the current state, tape contents, and head position on tape 2 according to .

- After each simulated step, writes the current tape symbol , state q, and head direction d as to the scratch tape to record the computational history.

- If M enters state , transitions to state and sets its time lag on tape 1 to the binary encoding of the current step number C.

- In state , sends the current symbol on tape 2 back C steps in time. It then moves the head to the position on tape 2 corresponding to time 0.

- transitions to state and reads the symbol from the scratch tape at the position corresponding to time 0.

- transitions to state , writes to tape 2, moves the head in direction d, and updates the current state to q.

- transitions back to state and continues the simulation of M.

- If M enters a halting state in H, also halts, and its output is the contents of tape 2, which represents the final tape of M.

- M starts with input "01" on its tape.

- At step 3, M enters state and sends the current symbol "1" to time 0.

- M continues its computation and halts at step 5 with output "11".

- starts with input "01" on tape 2 and time lag 3 (binary "11") on tape 1.

- simulates steps 1 and 2 of M in state , writing the computational history to the scratch tape: "(0, , R)", "(1, , R)".

- At step 3, M enters , so transitions to and sends the current symbol "1" back 3 steps in time.

- moves the head on tape 2 to the position corresponding to time 0, transitions to , and reads "(0, , R)" from the scratch tape.

- transitions to , writes "1" to tape 2, moves the head right, and updates the current state to . The scratch tape now contains "(1, , R)" at the position corresponding to time 0.

- transitions back to and continues simulating M from state with tape contents "11".

- simulates steps 4 and 5 of M, writing the computational history to the scratch tape: "(1, , R)", "(1, , R)".

- At step 5, M enters a halting state, so also halts with output "11" on tape 2.

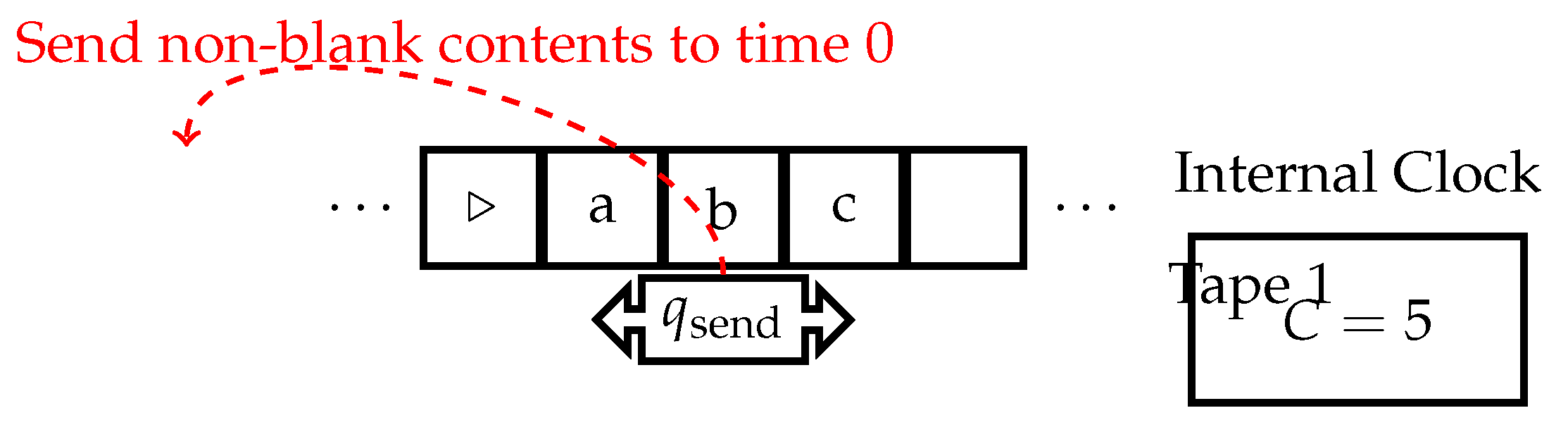

3.4. Full Tape ICTTM

- Internal counter C incremented each step.

- State to send all non-blank contents of tape 1 to time 0.

- C increments each timestep.

- Upon entering , the entire current non-blank contents of tape 1 are sent to the same positions at time 0, overwriting what was there.

- Computation continues from .

- Halting gives the output on tape 1.

- has tape alphabet , where the additional symbols encode the tape contents and their positions at each step.

- has states , where is used for simulating M, is used for initiating the sending of symbols back in time, is used for iterating through the scratch tape history, is used for retrieving the sent symbol, and is used for writing the retrieved symbol to the simulated tape of M.

- has initial state and halting states .

- uses tape 1 for simulating the tape of M and encoding the computational history, and a scratch tape for storing the symbols and their positions to be sent back in time.

- starts in state with input w on tape 1.

- In state , simulates one step of M using the transition function . It updates the current state, tape contents, and head position on tape 1 according to .

- After each simulated step, writes the current tape symbol and its position i as to the scratch tape to record the computational history.

- If M enters state , transitions to state and moves the head to the beginning of the scratch tape.

- In state , iterates through the scratch tape, reading each symbol one at a time.

- For each , moves the head on tape 1 to position i, transitions to state , and sends back to time 0 at position i.

- then moves the head back to the scratch tape, transitions to state , and reads the next symbol .

- transitions to state , moves the head on tape 1 to position , writes , and transitions back to state .

- After processing all symbols on the scratch tape, transitions back to state and continues the simulation of M.

- If M enters a halting state in H, also halts, and its output is the contents of tape 1, which represents the final tape of M.

- M starts with input "01" on its tape.

- At step 3, M enters state and sends the entire non-blank contents of the tape, "011", back to time 0.

- M continues its computation and halts at step 5 with output "0111".

- starts with input "01" on tape 1.

- simulates steps 1 and 2 of M in state , writing the computational history to the scratch tape: "(0, 0)", "(1, 1)".

- At step 3, M enters , so transitions to and moves the head to the beginning of the scratch tape.

- transitions to and reads the first symbol "(0, 0)" from the scratch tape.

- moves the head on tape 1 to position 0, transitions to , and sends "0" back to time 0 at position 0.

- moves the head back to the scratch tape, transitions to , and reads the next symbol "(1, 1)".

- transitions to , moves the head on tape 1 to position 1, writes "1", and transitions back to .

- reads the next symbol "(1, 2)" from the scratch tape, moves the head on tape 1 to position 2, transitions to , and sends "1" back to time 0 at position 2.

- After processing all symbols on the scratch tape, transitions back to and continues simulating M from time 0 with tape contents "011".

- simulates steps 4 and 5 of M, writing the computational history to the scratch tape: "(1, 3)".

- At step 5, M enters a halting state, so also halts with output "0111" on tape 1.

4. Properties

4.1. Self-Consistent Computability

- if does not cause a new bifurcation

- if causes a single new bifurcation

- , i.e., no symbols are sent to the past by , and halts normally with output .

- , i.e., symbols are sent to the past, causing bifurcations, but . That is, all branches halt with the same output on tape 2. We consider this a halting computation with the common output.

- If there exist l and m such that the outputs of halting branches are not equal, , then we consider this computation to be non-halting.

- At step 3, M sends the symbol "1" back to step 1, overwriting the original "0".

- M continues its computation and halts at step 5 with output "11".

- At step 3, M sends the symbol "0" back to step 1, overwriting the original "0".

- At step 4, M sends the symbol "1" back to step 2, overwriting the original "1".

- The branch that starts with the original input "01" halts at step 5 with output "00".

- The branch that receives the symbol "0" at step 1 halts at step 5 with output "01".

- If M has a unique timeline with no time travel, the output is the tape 2 contents upon halting.

- If M bifurcates timelines by time travel, the output is the common tape 2 contents across all branches when halting.

- If M bifurcates timelines by time travel but some branches have different traditional outputs, we consider the self-consistent computation to be non-halting or entering an error or rejecting state.

- Create an initial configuration of M on input w.

- Set list to track configurations.

-

While L is non-empty:

- (a)

- Remove the first configuration C from L.

- (b)

- Simulate one step of C to generate configurations .

- (c)

-

If C halts, compare the output tape to C’s previously saved output tape.

- If equal, continue to the next C.

- If unequal, reject.

- (d)

- Add all to the end of L.

- If L empties with no rejection, accept.

- Each C depends only on its parent configuration, so T can correctly recreate C.

- The branching factor of M is finite, so is at most exponential in runtime.

- The branching factor of M is finite as it is an SSTTM. Thus, is at most exponential in the runtime, i.e., for some constant c and runtime t.

- U can correctly recreate any configuration C from its parent.

- As L is finite, U will eventually simulate all possible configurations of .

- N simulates T on input to obtain T’s prediction of whether on input will result in a finite or infinite number of bifurcations.

- If T predicts that on input will result in a finite number of bifurcations, N simulates on input but introduces a time travel paradox that causes an infinite number of bifurcations. N achieves this by sending a symbol back in time that contradicts the symbol that was originally present at that position, creating a scenario similar to the grandfather paradox. This contradiction leads to an infinite number of bifurcations, each corresponding to a different resolution of the paradox.

- If T predicts that on input will result in an infinite number of bifurcations, N simulates on input without introducing any additional time travel. In this case, N will have the same number of bifurcations as , which is finite.

4.2. Complexity Constraints

- simulates for steps, recording the output as o.

- At the end of the simulation, sends the pair back in time to the initial configuration.

- then halts with output o.

- The original branch where is simulated for the full steps before halts.

- The new branch starting with the output pair sent back in time.

- The worst-case runtime of branch is to simulate .

- The runtime of branch is constant as it starts with the output.

- To be self-consistent, the output o must be produced in full in branch .

5. Conclusions

- Single Symbol Time-Traveling Turing Machines (SSTTMs) can simulate other restricted models like Internal Clock Time-Traveling Turing Machines and also models with arbitrary size data traveling. This establishes a robust foundation for studying temporal effects in computation.

- Determining computational consistency is possible within the SSTTM model itself. We have Universal SSTTMs that can function as watchers and controllers of SSTTM consistency. The ability to send outputs back in time allows verifying correctness across branches.

- Requiring self-consistent outputs prohibits using time travel to speed up computation in the worst-case time complexity. We cannot restrict a longer computation into a shorter computation by removing some of the parallel time bifurcations.

- Our models only allow sending limited symbols or tape contents back in time. Extending the model to allow more general message passing, such as sending entire programs or algorithms, could reveal new insights into the relationship between time travel and computational complexity. For example, what are the implications of sending optimized machines from the future back in time? This could lead to new connections between time travel, compression, and algorithmic information theory.

- Our models focus on deterministic computation with a limited form of non-determinism introduced by time travel. Exploring the interplay between time travel and other forms of non-determinism, such as probabilistic or quantum computation, could yield new insights into the nature of computation and the role of time. For example, how does the introduction of time travel affect the computational power of Probabilistic or Quantum Turing Machines?

- Our models consider time travel within a single computational system. Extending the model to allow interactions between multiple SSTTMs could lead to new questions about the nature of causality, consistency, and communication in the presence of time travel. For example, how can multiple SSTTMs coordinate to achieve a common computational goal while maintaining consistency across their respective timelines?

Acknowledgments

References

- Gill, J.T. Computational Complexity of Probabilistic Turing Machines. Proceedings of the Sixth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1974; STOC’74; pp. 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Benioff, P. Models of Quantum Turing Machines. Fortschritte der Physik 1998, 46, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, I.D. Time machine and self-consistent evolution in problems with self-interaction. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 45, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, S.; Watrous, J. Closed timelike curves make quantum and classical computing equivalent. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2008, 465, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, T. Hypercomputation: computing more than the Turing machine. arXiv 2002, arXiv:math.LO/math/0209332. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C.H. Logical Reversibility of Computation. IBM Journal of Research and Development 1973, 17, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. Unpredictability and undecidability in dynamical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 2354–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanehsar, S.B.; Didehvar, F. Turing Machines Equipped with CTC in Physical Universes. CoRR 2023, abs/2301.11632. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, D. Quantum mechanics near closed timelike lines. Phys. Rev. D 1991, 44, 3197–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, R.; Ivanov, S. How to Go Beyond Turing with P Automata: Time Travels, Regular Observer w-Languages, and Partial Adult Halting. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Brainstorming Week on Membrane Computing 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, R.; Say, A.C.C. One Time-traveling Bit is as Good as Logarithmically Many. 34th International Conference on Foundation of Software Technology and Theoretical Computer Science (FSTTCS 2014); Raman, V., Suresh, S.P., Eds.; Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Dagstuhl, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Manchak, J.B. Can We Know the Global Structure of Spacetime? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2009, 40, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamkins, J.D.; Lewis, A. Infinite time Turing machines. Journal of Symbolic Logic 2000, 65, 567–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, S.; Bavarian, M.; Gueltrini, G. Computability Theory of Closed Timelike Curves. 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).