3.1. Underwater Image Brightness Consistency Recovery

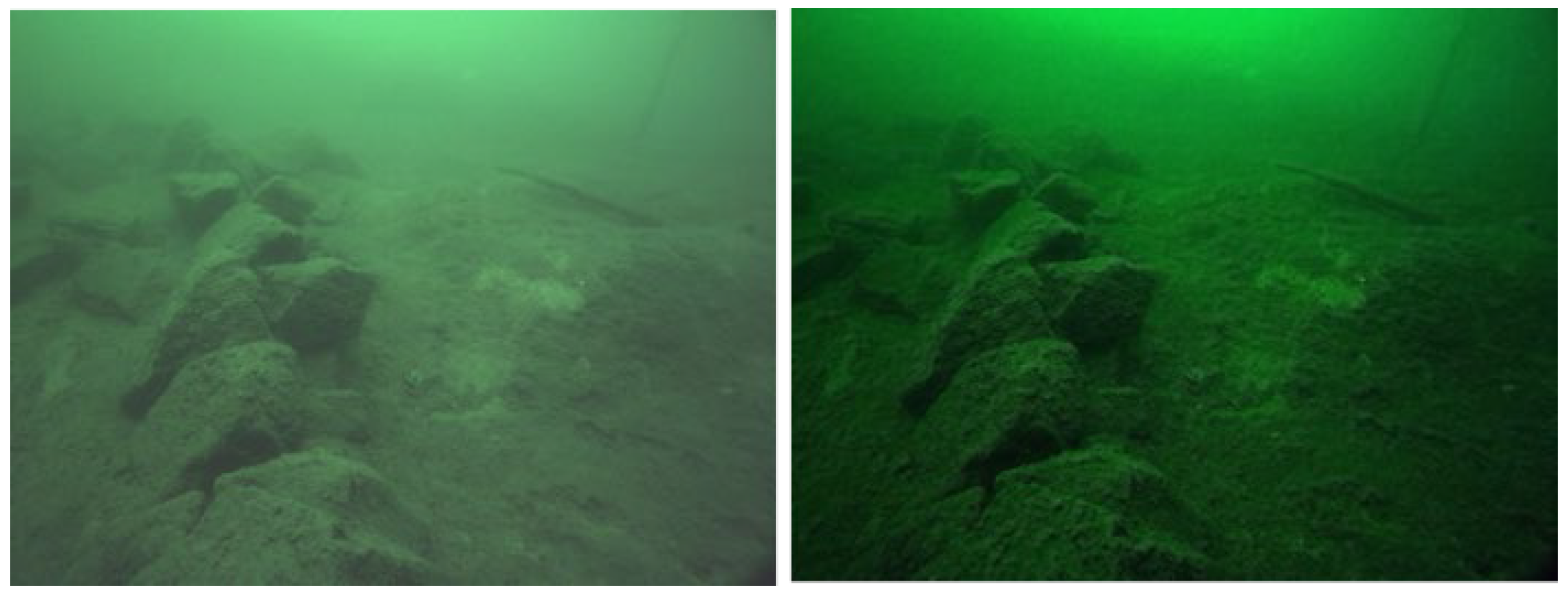

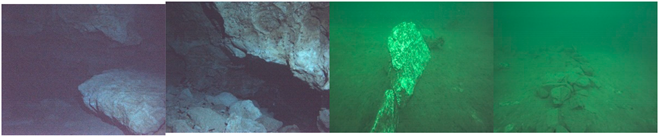

Visual odometry is more sensitive to changes in light, and the uneven absorption of light in the water body will greatly affect the extraction and matching of feature points by the feature checker. Different wavelengths of light in the water have different attenuation characteristics, in the visible range, the longer wavelengths of red light in the water has a larger attenuation rate, the weakest penetration rate, usually only 3-4 meters, and blue light, green light and other shorter wavelengths of light can be propagated in the water for a longer distance, the uneven attenuation of this light will lead to underwater optical image distortion, usually manifested as the image of the bluish, greenish. This color distortion will lead to a reduction in image contrast and increase the difficulty of feature point extraction.

In the underwater cave environment, the main source of light is the searchlight carried by the exploration platform, which is an artificial light source with strong directionality, limited by the power of the light source, the brightness difference between the inside and outside of the artificial light source illumination range is large. The use of searchlights in the illumination of the designated target, but also because of the light path of the mask blocking, resulting in more shadow areas. These influences are manifested in the image as an uneven distribution of brightness, i.e., the image is roughly characterized by high brightness in the central area and low brightness in the surrounding area. And part of the protruding object back to the light source is a low brightness black area.

To improve the contrast of underwater images, image contrast enhancement processing is usually performed using the HE (histogram equalization) method. However, in use, if the algorithm is used directly to process underwater images, it will appear to increase the brightness of high-brightness regions and decrease the brightness of low-brightness regions, thus exacerbating the overexposure and underexposure of the image. In order to reduce the occurrence of such situations, it is necessary to restore the light intensity of the underwater image before image enhancement to reduce the brightness differences in the image regions caused by uneven illumination of the artificial light source.

To establish an underwater light model, the image information recorded by the camera is regarded as the superposition of the reflected light in the scene and the scattered light in the water, and the light intensity at each position in the image can be expressed as the following equation:

Where

represents the light intensity of the image at the

position, the gray value of the image at that position.

is the reflected light intensity at the location,

is the scattered light intensity, and

is the component weight. Due to the limitation of the irradiation range of the artificial light source resulting in different light intensity at different locations, the light range attenuation coefficient

is introduced to represent the attenuation coefficient at the image location

.

The maximum value

of the mean gray value of the pixel points in the coverage range of each window is selected as the base brightness, and the range attenuation coefficient at this position is considered to be 1. According to the invariance of the light distribution, the mean and the standard deviation of the pixel distribution of each window should be roughly the same in the case of sufficient light. Therefore, the light attenuation coefficients at different positions can be obtained from the difference of each window

.

Since the range of the window

is small, it can be approximated that the scattered light intensity

within the range of

is unchanged, at any position within the window, the scattered light intensity is constant, so the variance

can be deduced as the following equation:

where

is the variance of the reflected light distribution in window

and

is the mean of the reflected light in that window. Find the maximum value of the standard deviation

after removing the effect of the attenuation coefficient in all windows, denoted as

.

Approximating the weight of the scattered light at this position as 0, i.e.,

, based on the standard deviation invariance assumption

, the weight of the receivable reflected light

satisfies the following equation:

In the absence of natural light interference, the minimum value of the reflected light pixel gray value

in each window

is close to 0:

under these conditions:

where

denotes the minimum value of the light intensity of the image in window

. So the light attenuation coefficient

at each position in the image can be expressed as:

Based on the attenuation coefficient

and the scaling coefficient

, the pixel

can be calculated:

After performing the necessary calculations on the pixel points, it is possible to restore the image pixel values to reflect conditions of uniform and sufficient lighting. This approach helps to mitigate the problem of insufficient contrast enhancement caused by uneven illumination to a certain extent.

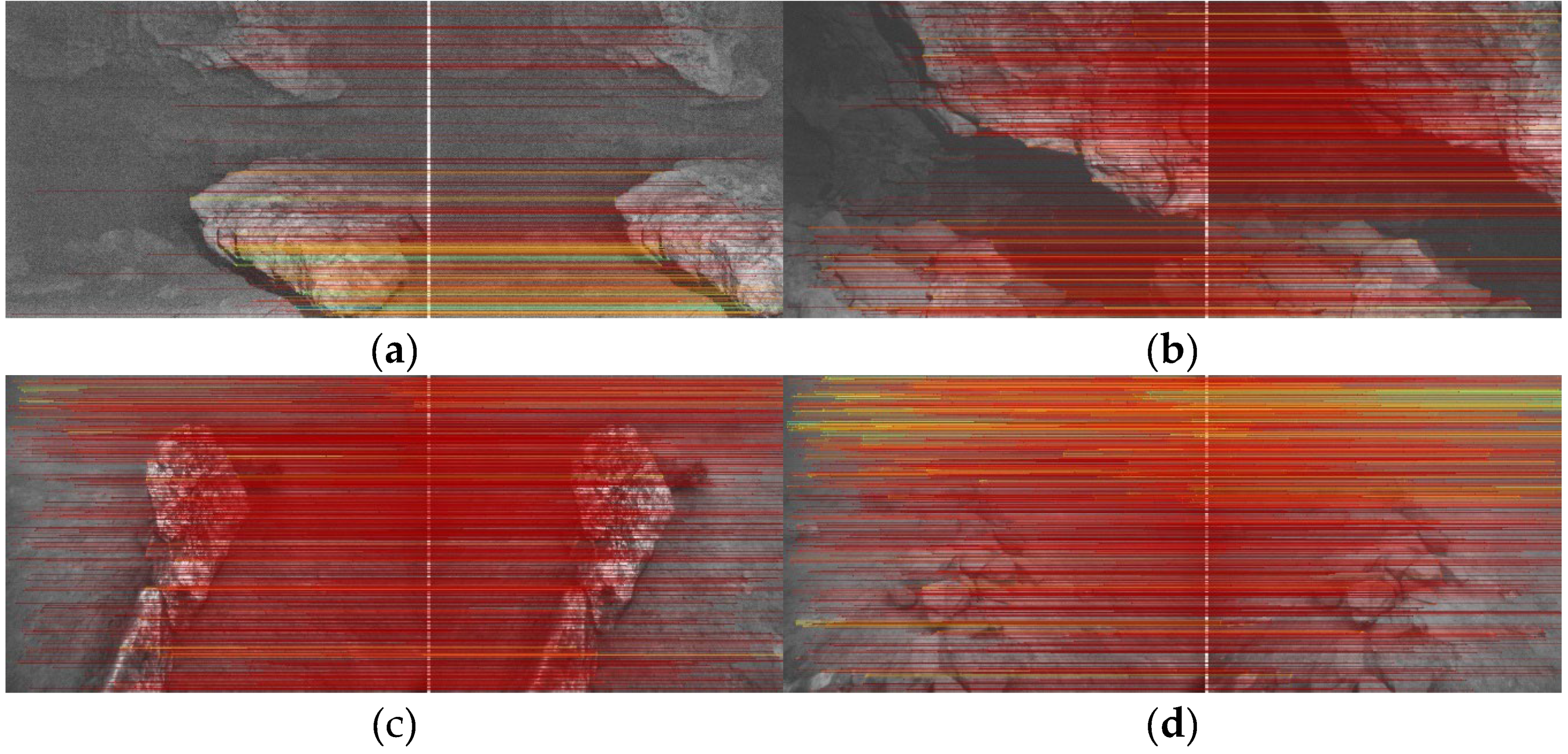

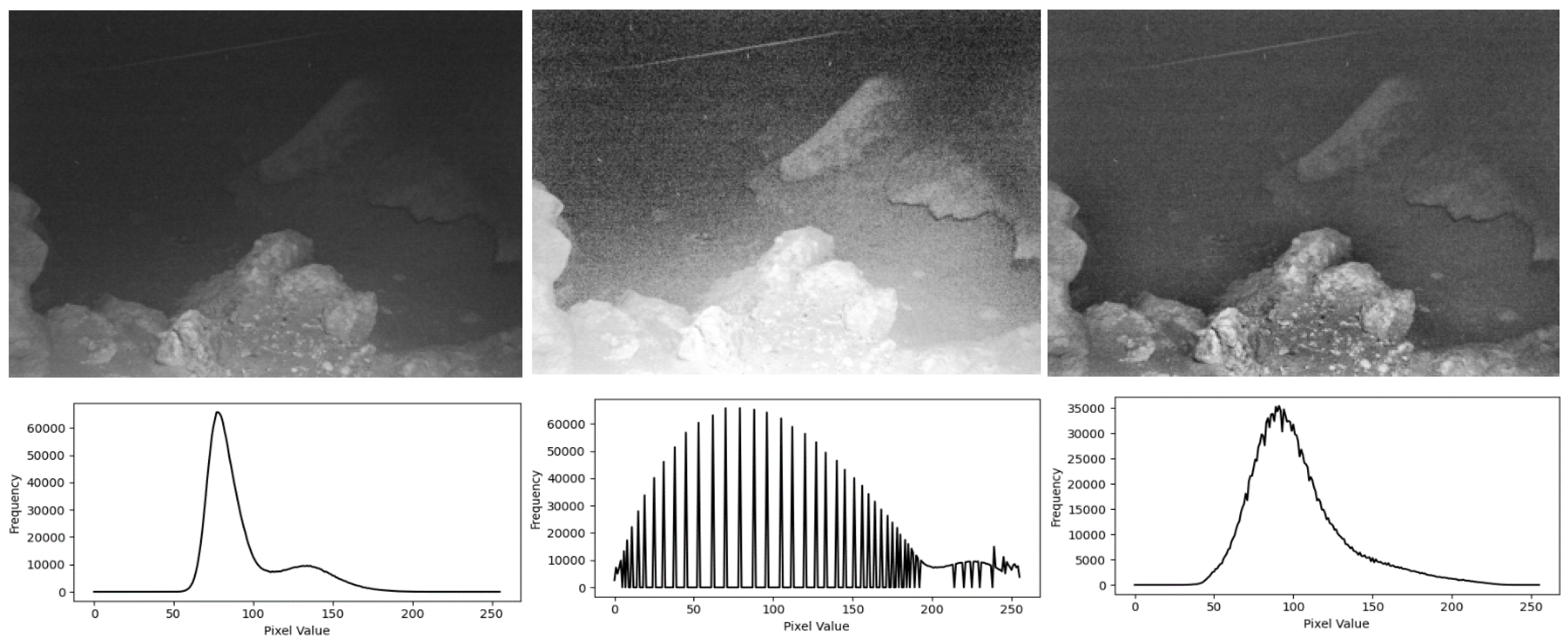

Then, the underwater images are processed using an adaptive histogram equalization (AHE) algorithm based on illumination consistency reduction. Initially, the images are divided into numerous small regions, and each region undergoes histogram equalization (HE) tailored to its local characteristics. For darker regions, the brightness is increased to enhance contrast and visual effect, while for brighter regions, the brightness is reduced to prevent overexposure or distortion.

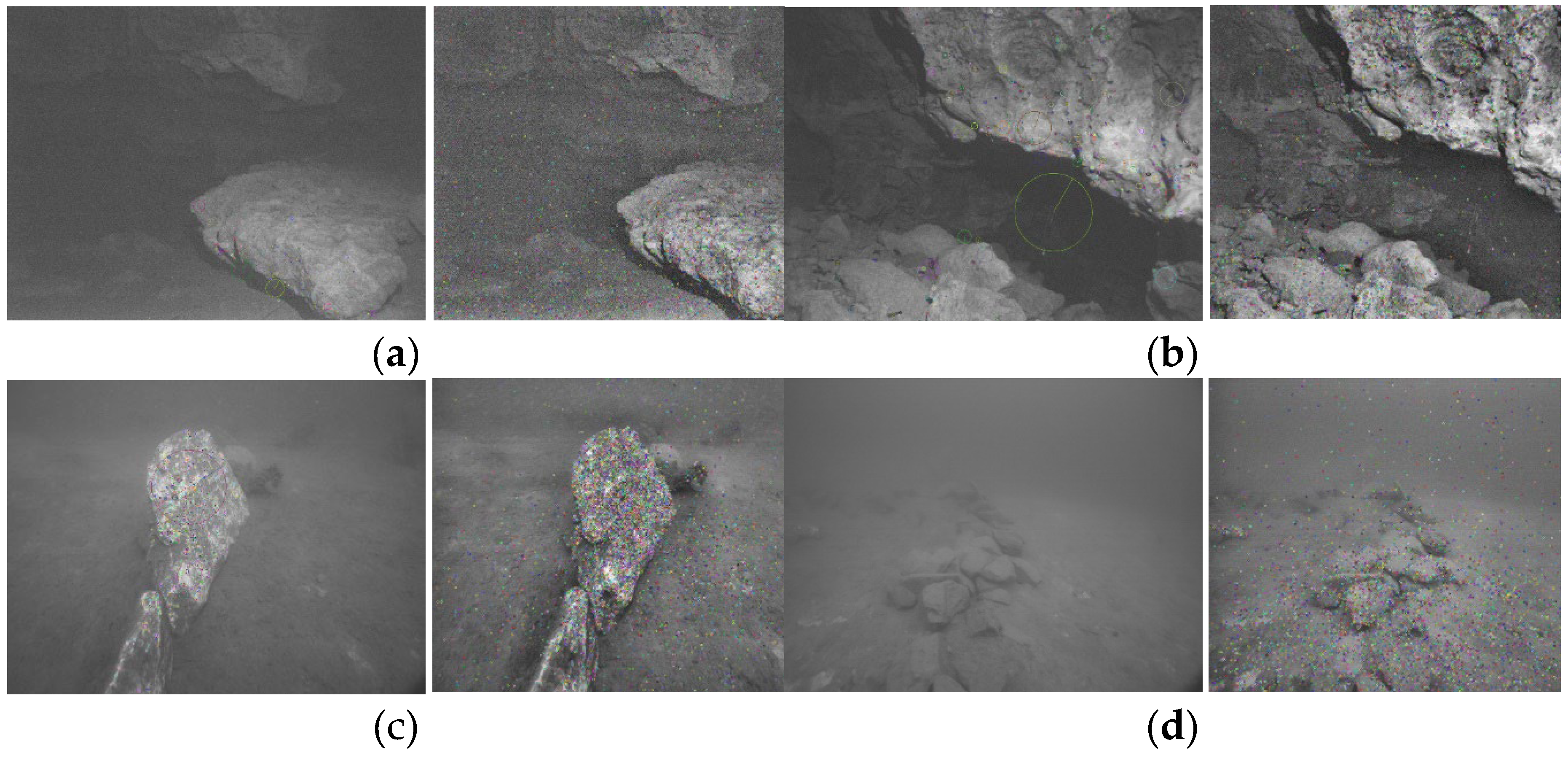

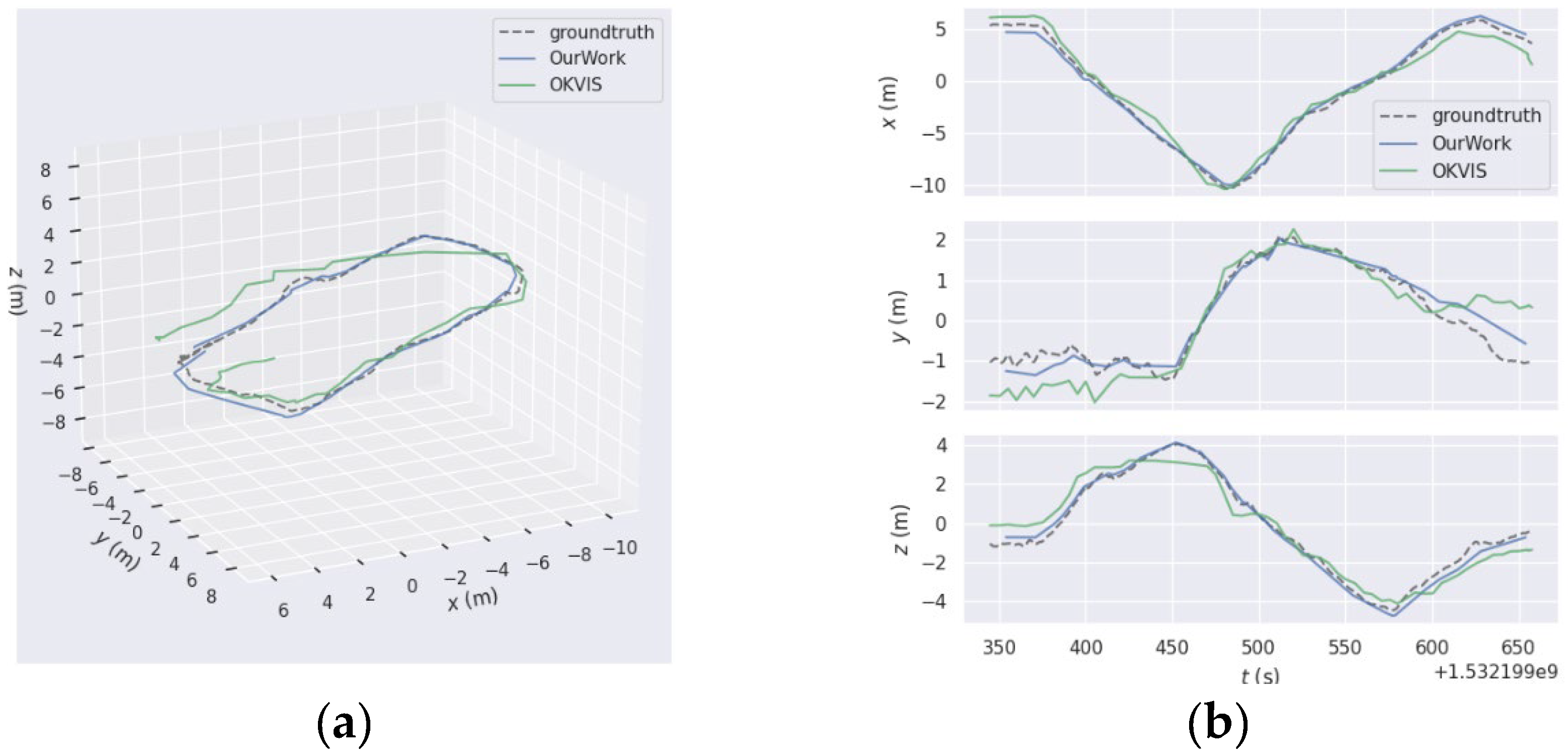

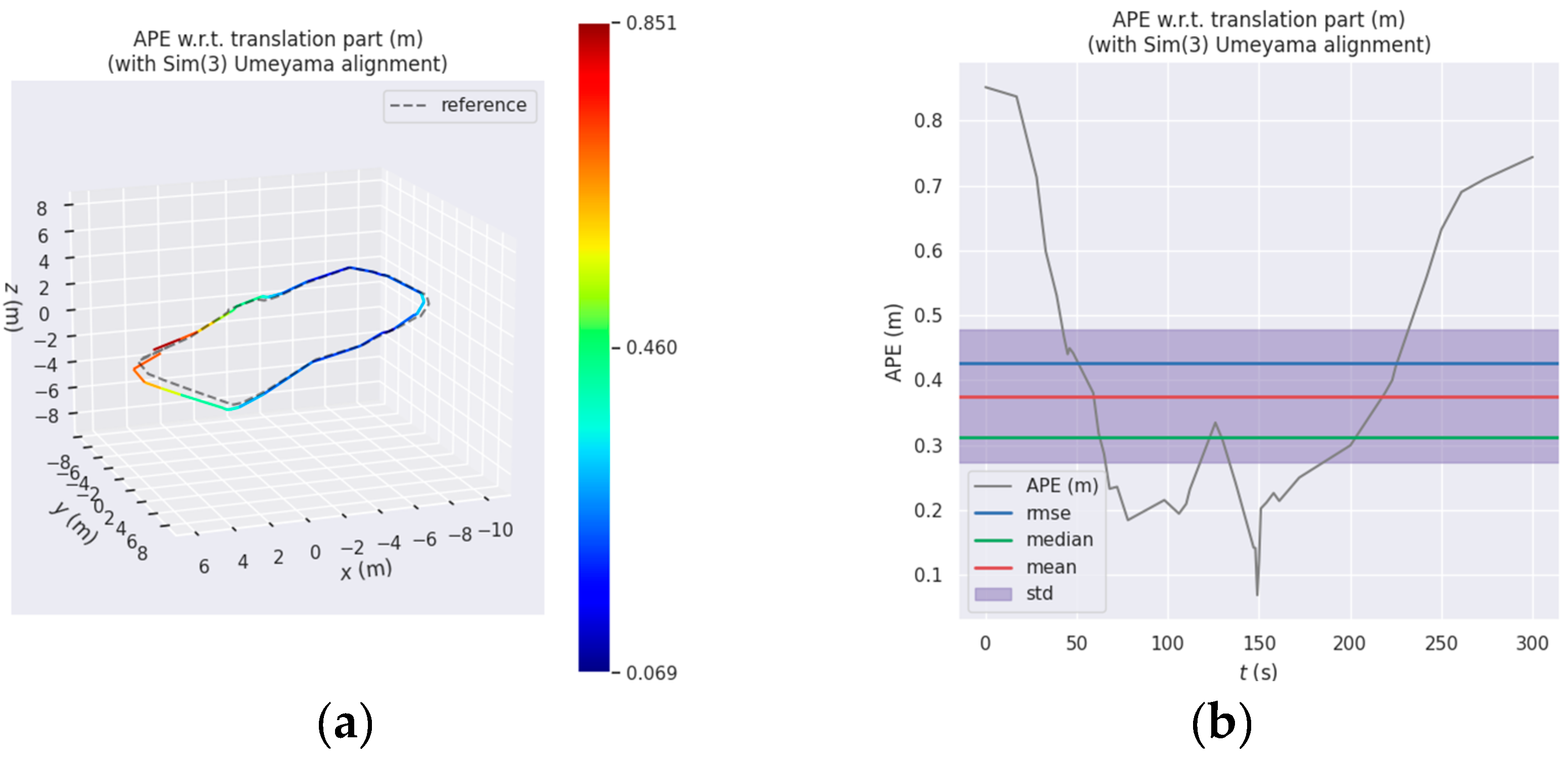

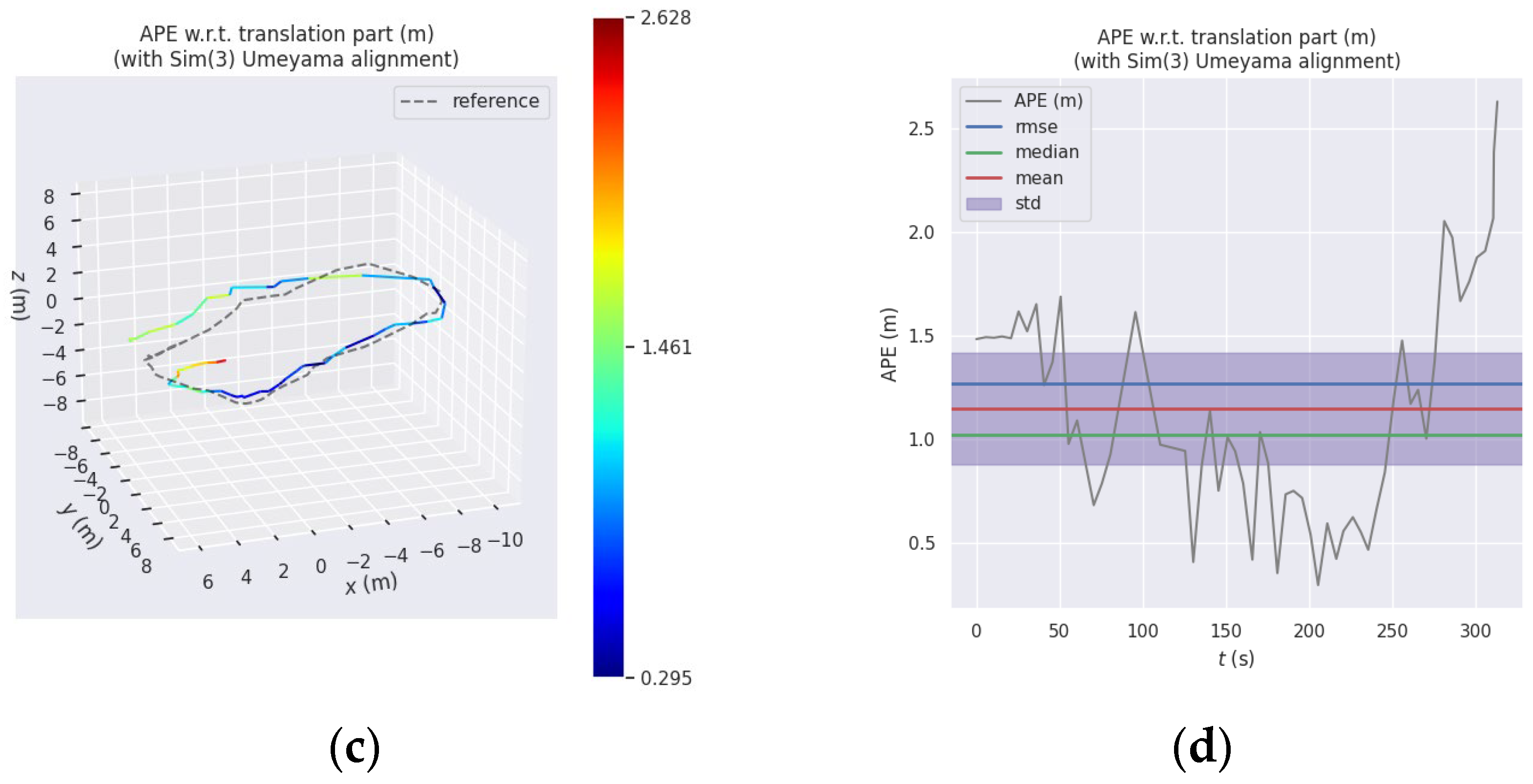

Figure 2 presents the results of the original image, HE processed image, and AHE processed image. It is evident that the image directly processed by HE exhibits a larger area of overexposure and white noise. This occurs because the HE algorithm processes the entire image globally, directly adjusting the gray level distribution across the entire image. When higher brightness areas exist in the original image, enhancing the overall contrast results in the brightness values of these highlighted areas being further amplified, leading to overexposure and noise. Conversely, for darker regions, the gray levels are reduced, diminishing the contrast of useful information, which leads to the loss of some fine image details and a reduction in the number of feature points. In contrast, after AHE processing, the contrast near the rock surface is improved, and the contours of objects in the distant background become clearer. Compared with using the HE algorithm directly, AHE avoids the problems of brightness anomalies and white noise caused by global histogram equalization.

Histograms are often utilized to infer the quality of an image. An image that includes all possible gray levels and has uniformly distributed gray levels across its pixel values is characterized by high contrast and varied gray tones. Consequently, if the gray values of an image are randomly distributed, its histogram should ideally resemble a normal distribution. In the case of the HE processed image, the corresponding histogram exhibits a trend resembling a normal distribution. However, the presence of an unusually large number of pixels with certain gray levels, which are transitionally broadened during the equalization process, leads to the appearance of spikes in the histogram. These spikes indicate the presence of noise or specific textures and details in the image, reflecting the limitations of global histogram equalization in handling diverse image regions uniformly. For the AHE processed image, the histogram distribution is closer to a normal distribution compared to the original image. The peaks of the gray values of the pixels are also reduced to a certain extent, indicating that the brightness uniformity processing has been effective. This improvement helps avoid issues of excessive brightness values in local areas of the image, resulting in a more balanced and visually coherent image. The enhancement provided by AHE thus effectively mitigates the problems associated with global histogram equalization, such as overexposure and noise, while preserving fine image details and improving overall feature detection.

3.2. B. Underwater Suspended Particulate Filtration

Image blurring caused by underwater suspended particulate matter is induced by irregular tiny particles floating in the load-bearing object, similar to the image blurring caused by haze conditions on the ground. Therefore, the suspended matter in the water can be regarded as a kind of noise and processed using an image defogging algorithm. The underwater environment is complex and dynamic. Even within the same body of water, variations in factors such as season, water temperature, and light conditions can affect the quality of images captured by the camera. Consequently, it is essential to determine the necessity of filtering suspended particulate matter based on specific image conditions. The presence of suspended particulate matter introduces a gray haze, which can be identified through blurring detection techniques.

By detecting the image gradient, the degree of blurring in an image can be assessed. The image gradient is calculated by determining the rate of change along the x-axis and y-axis of the image, thereby obtaining the relative changes in these axes. In image processing, the gradient of an image can be approximated as the difference between neighboring pixels, using the following equation:

A Laplacian operator with rotational invariance can be used as a filter template for computing the partial derivatives of the gradient. The Laplacian operator is defined as the inner product of the first-order derivatives of the two directions, denoted as

:

In a two-dimensional function

, the second-order differences in the x and y directions are:

The equation is expressed in discrete form to be applicable in digital image processing

If the pixels have high variance, the image exhibits a wide frequency response range, indicating a normal, accurately focused image. Conversely, if the pixels have low variance, the image has a narrower frequency response range, suggesting a limited number of edges. Therefore, the average gradient, which represents the sharpness and texture variation of the image, is used as a measure: a larger average gradient corresponds to a sharper image. Abnormal images are detected by setting an appropriate threshold value to determine the acceptable range of sharpness. When the calculated result falls below the threshold, the image is considered blurred, indicating that the concentration of suspended particulate matter is unacceptable and requires particulate matter filtering. If the result exceeds the threshold, the image is deemed to be within the acceptable range of clarity, allowing for the next step of image processing to proceed directly.

The issue of blurring in underwater camera images resulting from suspended particulate matter can be addressed by drawing parallels with haze conditions on the ground. Viewing suspended particulate matter in water as a form of noise, an image defogging algorithm (DCP) can be employed to mitigate the blurring effect.

It is hypothesized that in a clear image devoid of suspended particulate matter, certain pixels within non-water regions, such as rocks, consistently exhibit very low intensity values:

Dark channels in underwater images stem from three primary sources: shadows cast by elements within the underwater environment, such as aquatic organisms and rocks; brightly colored objects or surfaces, like aquatic plants and fish; and darkly colored objects or surfaces, such as rocks. Hence, the blurring observed in these images can be likened to the occlusion experienced in haze-induced scenarios. Consequently, suspended particulate matter can be regarded as noise and filtered accordingly.

Before applying the DCP method to filter suspended particles from underwater images, it is crucial to acknowledge a significant disparity between underwater images and foggy images. The selective absorption of light by the water body results in a reduced red component in the image, which can potentially interfere with the selection of the dark channel. To effectively extract the dark channel of the underwater image, the influence of the red channel must be mitigated. Therefore, the blue-green channel is selected for dark channel extraction.

The imaging model of foggy image is expressed as

where is the image to be de-fogged, is the fog-free image to be recovered, the parameter A is the optical component, which is a constant value in Eq. and is the transmittance. The two sides of the equation are deformed by assuming that the transmittance is constant within each window and defining it as , and then two minimum operations are performed on both sides to obtain the following equation

The imaging model of the image with the presence of more suspended particulate matter is expressed as:

Where denotes each channel of the color image, denotes a window centered on pixel , denotes the R, G and B color channels. Since imaging is different from foggy day imaging, in order to avoid the uneven attenuation of light interfering with the selection of the dark channel, it is necessary to exclude the influence of the red channel and select only the blue-green channel for dark channel extraction.

According to the dark primary color theory, the intensity of the dark channel of the fog-free image tends to zero. It means the intensity of the dark channel in the fogged image is greater than that of fog-free image. Because in foggy environments, the light is subjected to scattering by particles, which results in additional light, and the intensity of the fogged image is higher than that of the fog-free image.

and it can be deduced that:

The intensity of the dark channel of a fogged image is used to approximate the concentration of fog, which is expressed as the density of suspended particulate matter in the underwater image. Considering the situation in the actual underwater environment, retaining a certain degree of suspended particulate matter, the transmissivity can be recorded as:

For each pixel the minimum value in the color channel component is deposited into a grayscale image of the same size, and then this grayscale image is minimum filtered. However, in some cases, extreme values of the transmittance can occur. In order to prevent the value

from being abnormally large when the value

is very small, leading to the overall overexposure of the image screen, a threshold value

is set, and the final image recovery formula is as follows:

The defogging algorithm proves effective in reducing noise and halo effects. As depicted in

Figure 3, it is evident that post-processing with the dark-channel priority algorithm enhances object details and sharpens object edges, thereby improving clarity.

3.3. Acoustic and Visual Feature Association for Depth Recovery

The demanding underwater conditions pose significant challenges to the extraction and tracking of visual feature points, resulting in a noticeable degradation in the accuracy of depth direction information estimation. Leveraging the precise distance information provided by the sonar, the camera’s feature scale can be effectively recovered. This study enhances the feature extraction capability through image-level processing and subsequently utilizes sonar distance data to further augment the matching proficiency of feature points.

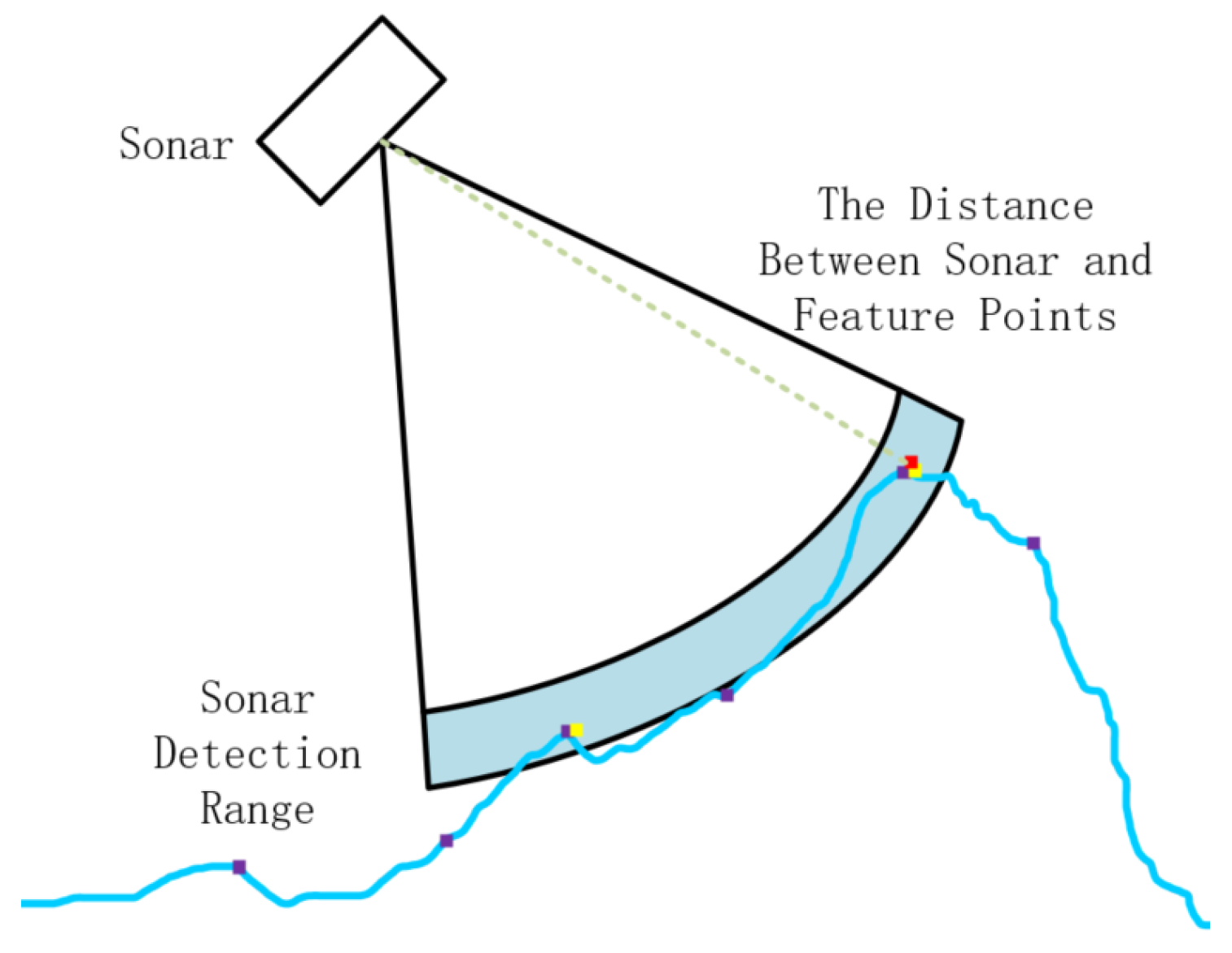

The sonar’s spatial detection range is typically visualized as a spherical configuration with the sonar device at its center. When targeting a specific direction, this detection process effectively confines the search area to a prism-shaped region. Leveraging the sonar’s horizontal resolution, individual beams are associated with a fan-shaped ring in cross-section, facilitating target range determination. As a result, the sizing of these fan-shaped rings serves as a criterion for filtering candidate matches between the sonar and camera feature points.

The uncertainty linked to sonar detection range escalates in tandem with the separation between targets. As targets move farther away, a single sonar beam encompasses a broader expanse, especially evident in the vertical dimension where the aperture of the sonar beam widens. In earlier processing approaches, a common practice involved extracting the point with the highest bin value within a beam and then calculating the spatial distance to its centroid, deemed as the spatial feature point for the sonar. However, the uncertainty linked to sonar features stems from two key factors. Firstly, the sparse resolution of sonar, coupled with the influence of the underwater environment on the distortion of bin values, hampers the accurate reflection of the true distance to targets. Secondly, as one moves away from the center of the sonar, a bin value corresponds to a spatial region rather than a precise point, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

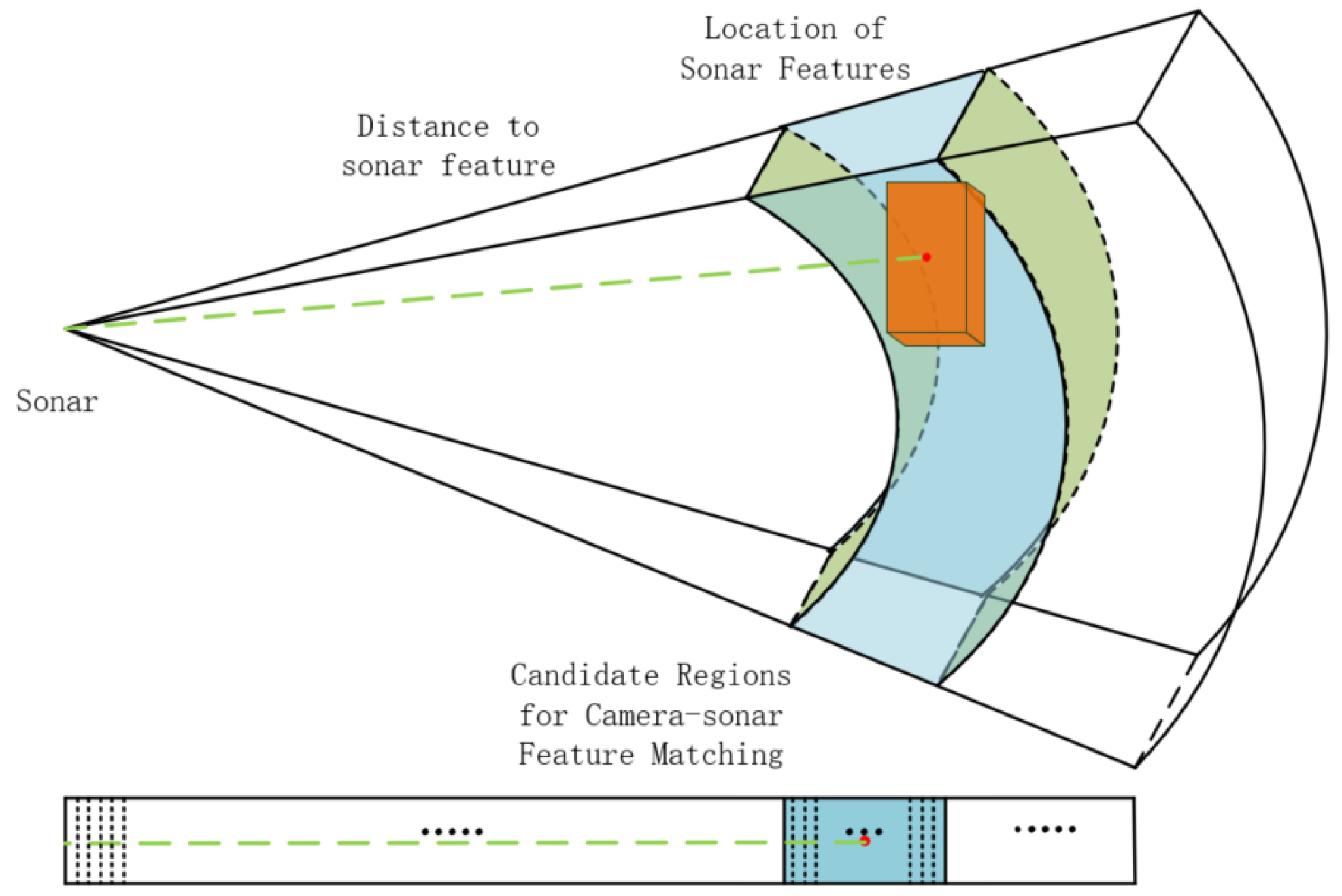

Therefore, accurately correlating sonar feature points with visual feature points is challenging, and this paper explores an alternative approach. Firstly, the spatial position of a coarse visual feature point is calculated. Then, for each beam, the maximum bin value is identified. In the sequence, the two values before and after this maximum bin value are also considered, totaling five bin values. A joint spatial region is constructed from the geometry of these five bin values within the sonar’s beam structure. Any feature points falling within this region are considered the candidates to be mutually correlated with the corresponding sonar feature point, as shown in

Figure 5.

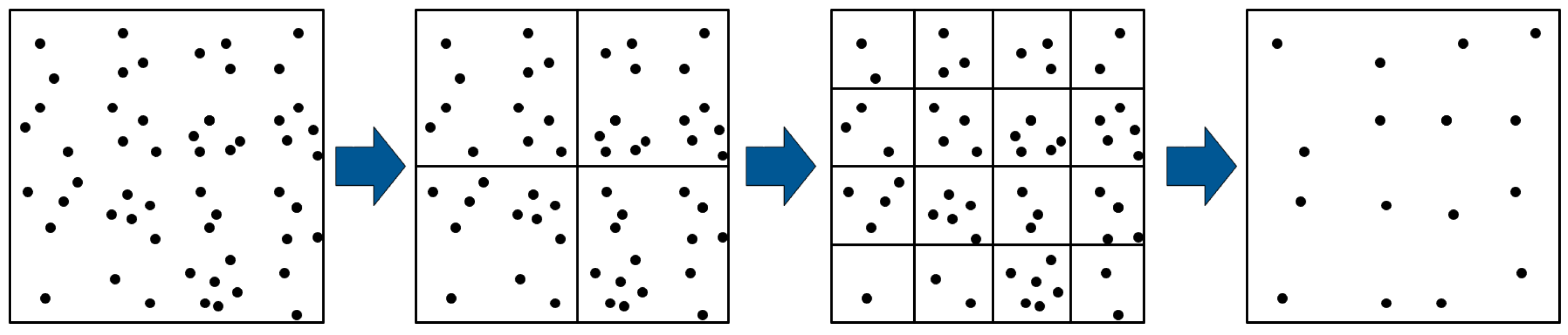

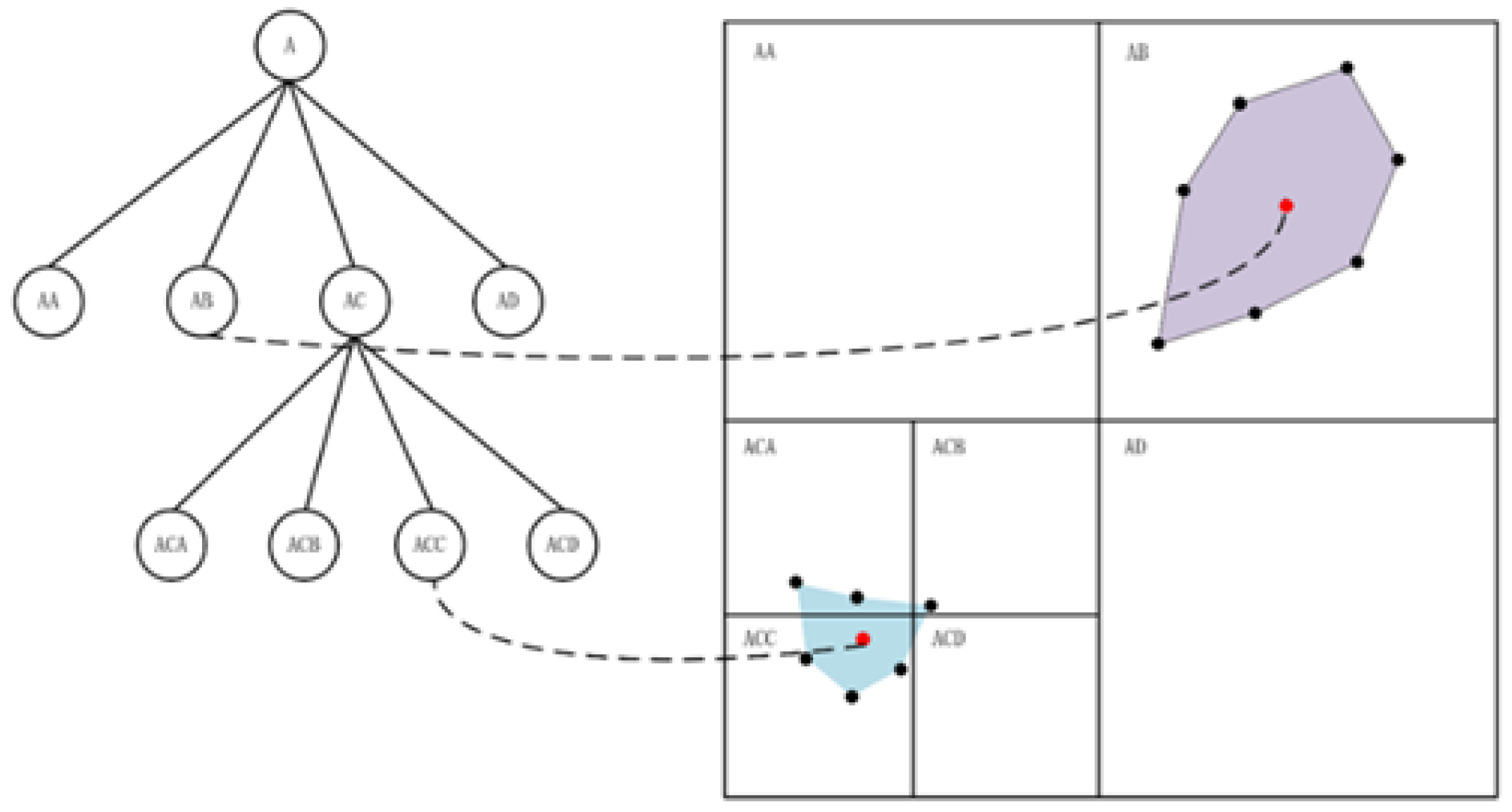

Typically, the distribution of feature points in an image exhibits strong randomness, with local areas containing more edges and corners, resulting in a higher concentration of extracted feature points. To enhance computational efficiency, a quadtree method is commonly employed to achieve a uniform distribution of feature points. Traditional quadtree homogenization involves recursively partitioning the feature points in the image into four equally divided regions. The recursion terminates based on a predetermined condition related to the number of feature points in the image. Ultimately, only one feature point is retained in each final segmented region after equalization.

Figure 6.

Using Quadtree for features unification.

Figure 6.

Using Quadtree for features unification.

After undergoing the aforementioned association method, the visual features associated with a single sonar feature may be one or multiple. In the case of multiple visual features, these visual features may span across multiple image regions after quadtree segmentation. During the partitioning process, when a group of mutually correlated points are connected to form a polygon, the quadtree’s partitioning region for this group of points should be larger than its Minimum Bounding Rectangle (MBR). As shown in

Figure 7, In the partitioning process shown in the bottom-left corner, although it ensures that each small area contains visual feature points, the visual feature points associated with a sonar feature are divided into different child node regions. However, as shown in the top-right corner, one node’s region contains the entire set of points.

In traditional quadtrees only leaf nodes can be assigned object (one polygon), hence an object may be assigned to more than one leaf node,it means these leaf nodes share same depth from sonar feature. While in the proposed quadtree segmentation, if the range matrix of a node contains the MBR of an indexed object and the range matrices of its four child nodes do not contain the MBR of that indexed object (intersecting or diverging), the object is added to that node. In this way, the root node intermediate nodes are able to be assigned indexed objects and the objects assigned to each node are not duplicated.

The termination condition for quadtree recursion in this method does not solely rely on the number of feature points but must also consider the resolution capabilities of the sonar. By incorporating the detection distance and resolution of the sonar, the maximum detection range of its sonar opening can be calculated. When the size of the divided area in the quadtree becomes smaller than the area of the polygenes, simple image segmentation becomes ineffective in providing optimal information for feature matching between the sonar and the camera. Thus, image segmentation is terminated to conserve computational resources.