1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which emerged at the end of 2019, spread rapidly all over the world and caused the largest pandemic disease of humans in the past century (1,2,3). Currently, SARS-CoV-2 continues to generate novel variants and threaten global public health, causing morbidity and mortality (4,5,6). SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus of the genus betacoronavirus, which has the largest genome (about 30,000 nucleotides) among single-stranded RNA viruses (7,8). Genetic studies have documented that SARS-CoV-2 has 79% and 50% sequence similarity with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV which are also konown to cause severe diseases in humans, respectively (7). SARS-CoV-2 virion consists of spike (S), nucleocapsid (N), matrix (M), and envelope (E), which are structural proteins. The S protein plays critical role in the life cycle of the virus and the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 disease (7,8,9). Following the binding of the S glycoprotein to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is widely expressed by a variety of human cells, acts as the primary entry receptor, leading to SARS-CoV-2 entering host cells (4,5,6,9). The S protein is a homotrimeric class I fusion glycoprotein that has two subunits, S1 and S2: S1 comprises the receptor-binding domain (RBD), which is responsible for the recognition of host cell surface receptors that enable virus entry, while S2 mediates membrane fusion (4,5,6,9)). The entry of SARS-CoV-2 requires furin-mediated cleavage at the polybasic-furin cleavage site (FCS) enabling membrane fusion. (4,5) Therefore, the FCS is a determinant of the high transmission rates of SARS-CoV-2 (4,5). TMPRSS2, a type II transmembrane serine protease, facilitates virus-host fusion by cleavage of the viral S protein (4). The clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infections are highly variable, ranging from severe disease, which is characterized by multiorgan dysfunction and a high mortality rate, to mild or asymptomatic disease (6,10). Comorbidities such as older age, metabolic syndrome, and ethnicity are major contributors to the immunopathogenesis of severe disease and clinical outcomes (1,6,10).

The immune system plays a central role in the pathogenesis, clinical course, and clinical outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as the effectiveness of vaccines (10,11,12,13). Immune cells may play a dual role in SARS-CoV-2 infection; while they function as an essential driver in the elimination of the virus, they also participate in the pathogenesis of severe disease by promoting the inflammatory process (13,14,15). Innate immune cells, whose main functions are mitigating the entry of the virus into the host cells, block the replication of the viral genome, and hamper the emergence of novel infectious virions, making them the most important players in building an effective immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection (10,12,14,15). In addition to this fundamental function, the innate immune system recognizes and eliminates virus-infected cells and accelerates the development of adaptive immune responses (10). Following infection, innate immune cells sense specific molecular structures, such as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on SARS-CoV-2 through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and activate antiviral mechanisms, such as the production of type I and type III interferon (IFN) and proinflammatory molecules in bystander cells, thus limiting viral replication and spread (16). High levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), generated by innate immune cells, are implicated in the pathogenesis of severe disease, worse outcomes, and poor survival (14,15,16). In addition, high levels of chemokines, such as CXCL8, CXCL9, and CXCL16, magnify the immunopathology and increase the severity of infection by recruiting immune cells such as neutrophils, macrophages, CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells at the location of infection (17). Multiple studies have documented a strong correlation between immune dysregulation, such as granulocyte dysregulation, and severe disease and unfavorable clinical outcomes (17). Innate immune cells recognize the SARS-CoV-2 virus through two distinct mechanisms: a) through a variety of toll-like receptors such as TLR-3, and TLR-7, the plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) sense the genomic viral RNA, and myeloid cells perceive endocytosed dsRNA b) cytosolic RNA sensors such as RIG-I and MDA5 or RIG-I receptors (RLRs) sense dsRNA intermediates (10,15,16). Consistent with the vast majority of viral infections, the first step of the innate immune response against SARS-CoV-2 is the expression of inflammatory mediators along with IFN-I and IFN-III (10,15,16). At the onset of COVID-19, mounting a potent IFN response is crucial to generate protective immunity, and blocking interferon signaling may pave the way for severe infection to develop (10,15).

The adaptive arm of the immune system can kill virus-infected cells and generate protective immune memory, which is the basis of vaccination strategies (14,15,16,17). The adaptive immune system consists of B and T cells, which are important in controlling viruses and the development of immunity (14,15,16). The magnitude of the adaptive immune response is determined by drivers such as the pathogenicity of the virus, the extent of inflammation, the frequency of adaptive cells, and the kinetics of viral replication (12,14,15,16). T cells are a major part of the adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, with profound CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell response observed in most infected patients (12,14,15,16). Following infection, naive T cells differentiate into CD4+ helper, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTCs), and memory cells (14,16,18). CD4+ T cells participate in the clearance of the pathogen by activating innate immunity, enhancing the CD8+ T cell function, and promoting B cells to produce antibodies (16,18). Additionally, CD4+ T cells are essential in the activation of proinflammatory macrophages and effective CD8+ T cell response (16,18,19). Following infection, CD4+ T cells differentiate into several different subsets that produce different surface molecules and cytokines, including Th1, Th2, Treg, follicular helper T (Thf), and CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (14,16,18). CD8+ T cells play crucial roles in the clearance of viral infection by preventing the replication of the viral genome and by recruiting inflammatory cells to the location of infection (15,16,18,19). In response to infection, naive CD8+ T cells differentiate into effector CD8+ CTLs and memory CD8+ T cells (15,16,18,19). CTLs can directly clear pathogen-infected cells by producing a variety of chemokines and effector molecules (12,18,19). Memory T cells play a critical role in mounting a strong and permanent immunity (18,19,20). Effector CD8+ T cell proliferation slows down over time, the majority of effector CD8+ T cells undergo apoptosis, and in the contraction phase (8-15 days), and in the memory phase, a small number of effector cells survive and differentiate into distinct types of memory cells (20). CD8+ T cell responses are similar to distinct microorganisms in terms of their proliferation kinetics, effector function, and memory-inducing capacity (18,19). However, the extent and persistence of inflammation varies depending on the pathogen (16,18,19). CD8+ memory T cells contribute to immune protection against invading pathogens (20). Dendritic cells (DCs) present viral peptides to T cells and viral proteins to B cells, together they initiate the development of effector cells to clear the virus (16,18,19). In chronic infection and cancer, persistent antigenic stimulation leads to the exhaustion of CD8+ T cells, which is characterized by the weakening or loss of cytotoxic functions of CD8+ T cells (12,14,15,16,18). In addition to neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 by blocking the binding of the S protein to the ACE2 receptor, antibodies also promote effector function by binding to the complement and Fc receptors (16,18). The magnitude of the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 is heterogeneous and declines rapidly after 4 months from the onset of infection, however, SARS-CoV-2-specific memory B cells increase 4-5 months after the beginning of infection (16,17,18).

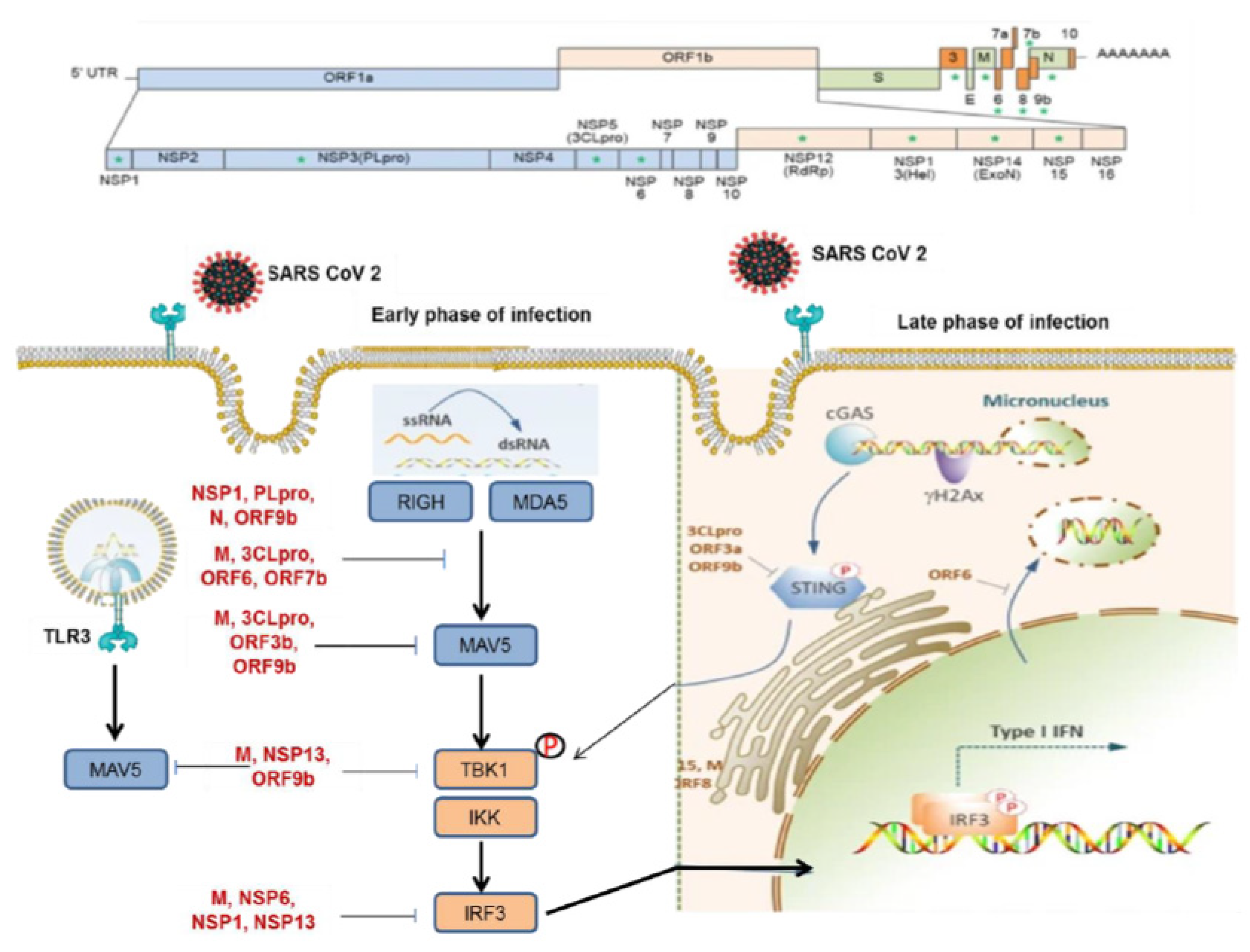

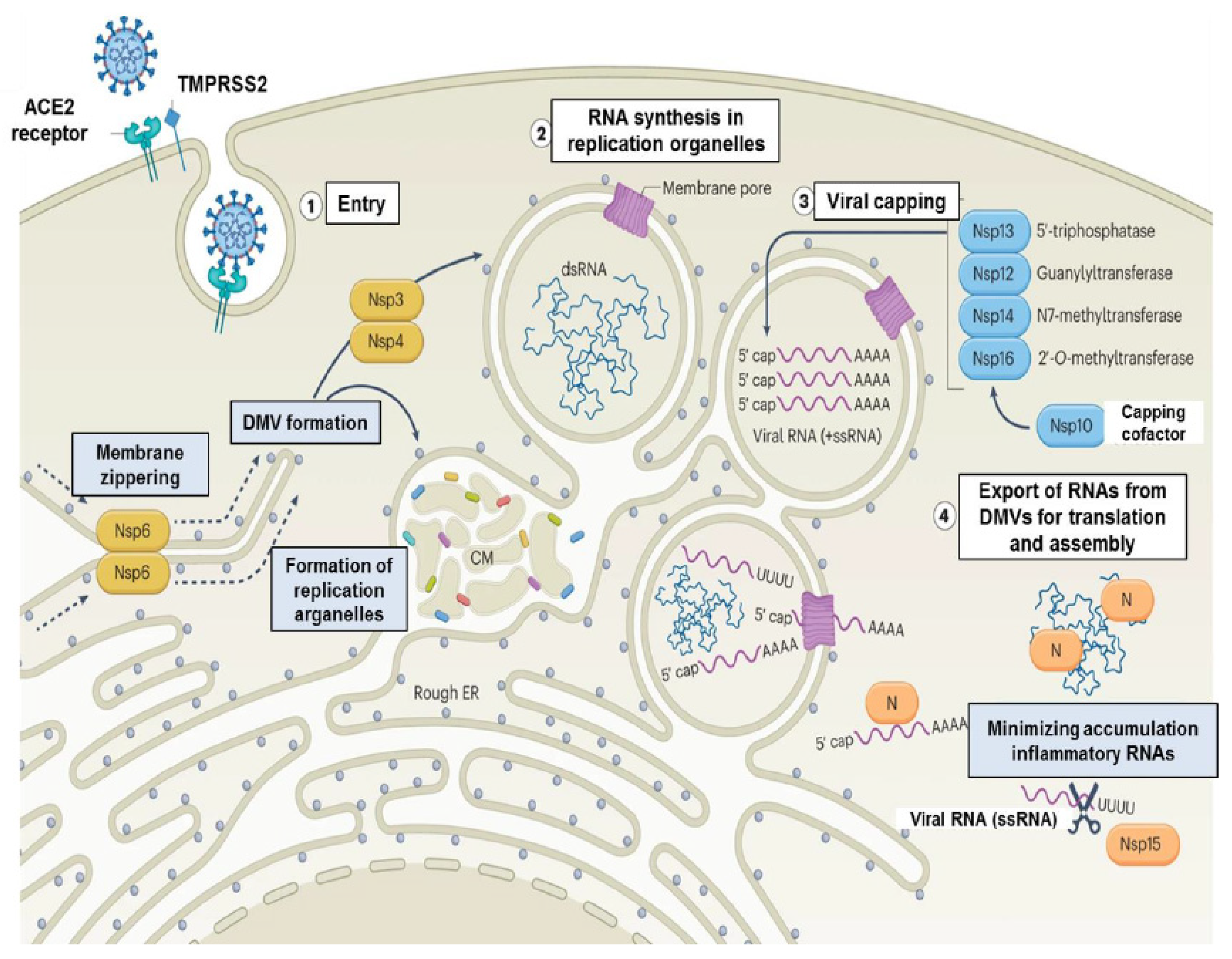

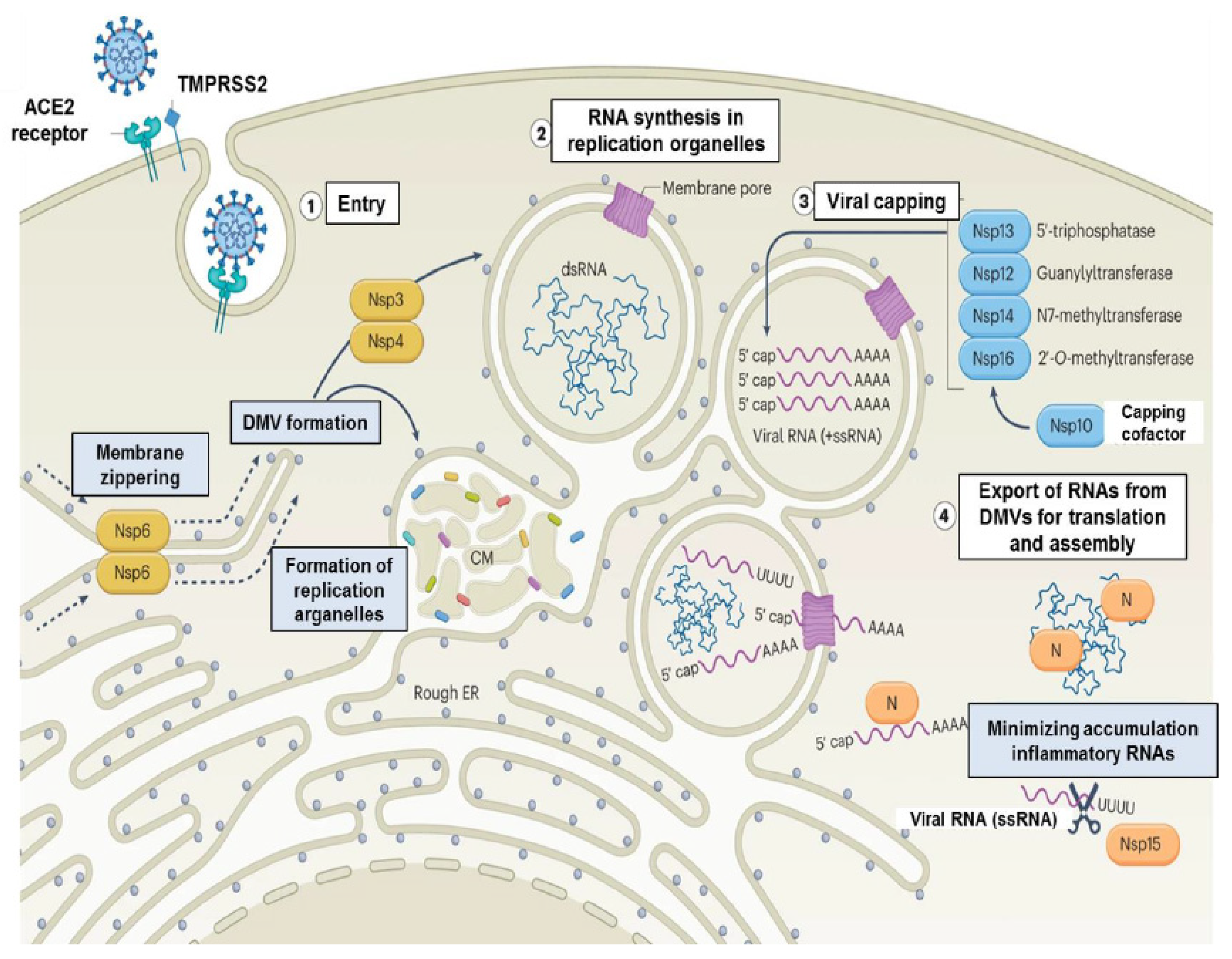

Detecting the immune evasion mechanisms of a virus is essential to understanding the pathogenesis of the viral infection as well as the challenges facing adaptive immunity and candidate vaccines (21,22,23). Consistent with the vast majority of viruses, SARS-CoV-2 can evade immune surveillance by a variety of mechanisms, including modulating inflammatory mechanisms, viral antagonism, and inhibiting interferon signaling and nuclear transport (10,21,22). SARS-CoV-2 can evade host recognition by altering the 5′-triphosphate (pppA) of its genomic RNA and sgRNAs via capping and methylation (21,23). Recent experimental trials revealed that Nsp10, Nsp13, Nsp14, and Nsp16 proteins participate in the capping event (10,22). Induction of antiviral defense before the virus completes its life cycle mitigates the virus to only the first infected cells (21,22). Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 delays the emergence of antiviral immunity by minimizing dsRNA assembly or hiding it from host sensors. Upon recognition of viral RNA, downstream activation by mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVs) promotes phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor (IRF), and nuclear translocation, resulting in the activation of antiviral response (10,21,22,23). SARS-CoV-2 M protein attenuates the antiviral response by limiting the assembling of MAVS (21,22,24). As viral replication accelerates, the host generates advanced sensing sensors, completely blocking the immune escape of the virus 810,21,22) The mounting of stress granules that trigger RLR signaling can be restrained by Nsp5 and N protein (21,22). Nsp3 plays a key role in evading the cellular sensors due to its ability to modify post-translational modifications, including ubiquitin and/or ADP-ribose conjugation (21,22). Additionally, SARS-CoV-2, through some of its proteins, interferes with the biology of host factors further downstream in the signaling cascade, thus allowing the virus to evade antiviral surveillance mechanisms (10,22). Furthermore, the virus can evade the host immune surveillance by interfering with nuclear transportation mechanisms (25).

2. Innate Immunity to SARS-CoV-2

Innate immune responses are essential in generating an effective response to SARS-CoV-2 (10,11,15,16,18). The innate immune system utilizes a variety of PRRs to sense specific molecular structures (10,11,15,16,18,21). The innate immune response plays a key role in the immunopathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection (10,15,18,21,22). The innate immune response mitigates the entry of the virus into the host cell and its replication within the cells and plays a critical role in the clearance of the virus-infected cell (15,18,21,22,23). Additionally, innate immunity mediates the emergence of adaptive immune responses (10,11,16,25). The innate immune system comprises various immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) such as natural killer (NK) cells (10,11,16,18,25). These cells densely harbor PRRs that recognize PAMPs and DAMPs to trigger inflammatory signaling pathways, programmed cell death, and immune cells that mitigate SARS-CoV-2 infection and promote viral elimination (10,11,15,16,18). Like other RNA viruses, SARS-CoV-2 is detected by two distinct mechanisms (16,26). One mechanism is through the use of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and myeloid cells which can sense the viral genomic RNA and endocytosed double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) or single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), respectively, using a variety of toll-like receptors (TLRs) (16,26). The other mechanism acts by recognising the dsRNA intermediates in the infected cell during viral replication via cytosolic RNA sensors such as RIG-I and MDA or RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) (16,26). Engagement of TLRs and RLRs activates type I and type III interferons and NF-κB-related proinflammatory soluble molecules (16,26).

PRRs are structures that detect the specific molecular patterns on the surface of microorganisms and damaged cells (10,11,15,16,26,27). Following sensing and engaging with ligands, PRRs exert their immunoprotective effects against infections (10,11,27). PRRs are classified into five types according to protein domain similarity: Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic-acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptors (ALRs) (10,11,16,25). PRRs contain ligand recognition domains, intermediate domains, and effector domains, and able to detect and bind to their ligands, as well as recruit adaptor molecules through their effector domains and activate downstream signals to exert their effects (18,27). Innate immune cells sense PAMPs, which are well-conserved molecular structures that have specific molecular properties that are vital for the survival of the microorganism, through PRRs (25,27). PAMPs are composed of nucleic acids, including viral RNA and DNA, but they also include surface-exposed glycoproteins, lipoproteins, and various membrane components (15,18,25,27). However, some proteins and metabolites formed as a result of tissue damage and cell necrosis, called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are detected by PRRs, and the innate immune system is activated, leading to inflammation (18,27).

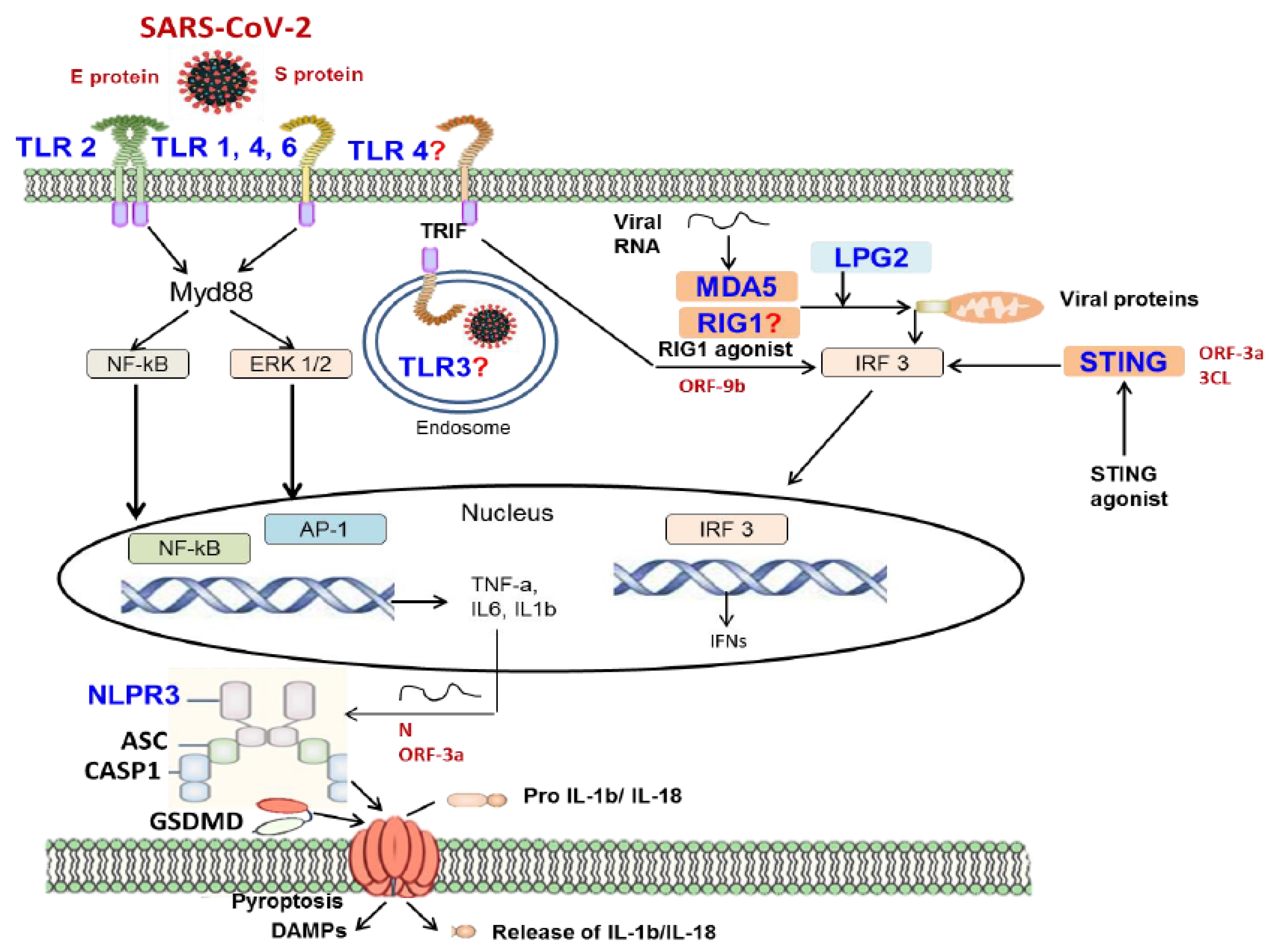

TLRs are a family of PRRs, that play critical roles in recognizing and eliminating PAMPs derived from bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens (11,16,18,27). They also detect and eliminate DAMPs released from dying or lytic cells (10,11,18,27). TLRs are expressed at high levels in a variety of cells, such as DCs, macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (11,18,27). This family of receptors is closely associated with the induction of initial innate immune responses following bacterial and viral infections (11,15,27) TLRs promote the activation of proinflammatory cytokines and type I interferons, which play a critical role in the induction of the host immune response against bacterial, fungal, and viral infections (11,15,27). TLRs are type I transmembrane glycoproteins and are composed of an extracellular region, a transmembrane region, and an intracellular region (11,15,18,27). The TLR expression pattern of innate immune cells varies between cells, for example, TLR3 is expressed extensively in NK cells, whereas TLR4 is secreted at higher levels from macrophages (28). TLRs transduce signals via MyD88 and TRIF, which are key signaling adaptors for TLRs, to induce inflammatory cytokine expression (28,29). TLR1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 10 are produced on the surface of immune cells, in the form of heterodimers or homodimers, which generally perceive the membrane components of pathogens, including lipids, lipoproteins, and proteins, whereas TLR3, 7, 8, 9 are produced in the form of homodimers, which essentially sense the nucleic acids of pathogens (27,28). Sensing the viral ligands by TLRs triggers the recruitment of MyD88 or TRIF adaptor proteins and induces activation of NF-κB and interferon (IFN) regular factors (IRFs) (10,11,15,16,18,27,28,29).

TLR4 can bind and activate MyD88, NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and IRFs (28,29). Nuclear translocation of these molecules triggers the production of some pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF, IL-6, and IL-1, as well as transcription of genes encoding other immune sensors and secretion of IFN (11,27,28,29). Signaling through TRIF initiates IFN expression and some TLR4- and TLR-3-dependent transcription factors (27,29). In TLR2-deficient murine macrophages, activation of SARS-CoV-2-dependent pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and cytokine expression are weakened, and TLR2-treated human macrophages following stimulation with SARS-CoV-2 E protein; this suggests that TLR2 senses E protein to magnitude inflammatory responses (30,31). SARS-CoV-2 E protein stimulates TLR2-dependent inflammation by reducing serum IL-6 levels in mice (30). The study using single-cell technologies to investigate the factors that modulate the innate immune response during SARS-CoV-2 infection revealed that TLR2 participates in the activation of innate immunity (31). The protective role of the TLR3 signaling pathway has been demonstrated in both clinical and experimental studies (32,33). In the experimental trial conducted on Tlr3-/- mice, it was shown that the level of SARS-CoV-2 RNA increased and pulmonary functions were impaired compared to control mice during infection with mouse-adapted SARS-CoV (34). In the clinical study, stimulation with TLR3 agonists reduced SARS-CoV-2 viral load in alveolar epithelial cells (32). Although in silico studies reveal that the S protein can bind TLR1, TLR4, and TLR6, the roles of these TLRs in SARS-CoV-2 infection have not been completely elucidated (35,36,37).

Figure 1

RLRs are also intracellular PRRs that contain a family of RNA-binding helicases comprising intracellular sentinels, namely melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), RIG-I, and laboratory of genetics and physiology (LGP2), which can sense positive-stranded RNA originating from genomic, subgenomic, or replicative intermediates of SARS-CoV-2 (38). Although they display structural similarities, RLRs have distinct binding sites, enabling them to build a diversified and complementary defense system (38). RIG-I and MDA5 are key drivers of IFN pathways (21). In general, RIG-I senses RNAs with a 5′-triphosphate, a common feature of negative-strand RNA viruses, while MDA5 activation is mediated by binding of dsRNA, a common motif generated during viral replication of all viruses (38). Sensing of SARS-CoV-2 triggers the accumulation of adaptor proteins and the production of IFN-I and IFN-III (11,39). RLR activation occurs following the production of viral subgenomic RNA (sgRNA), which can engage the genomic template and form dsRNA structures (40). Upon post-translational activation, MDA5 assembles on dsRNA structures and then binds the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), resulting in the accumulation of ubiquitin ligases and serine/threonine kinases that orchestrate the activation of two relevant transcription factors, which are NF-κB and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) (18,21,22,27). The process of MDA5 assembly on dsRNA structures and binding to MAVS results in the formation of MAVS signalosome which triggers TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF)3, TANK-binding kinase (TBK)1, and IkB kinase (IKK) to promote phosphorylation of IRF3, which contributes to its nuclear migration and the transcription of interferon genes (41,42).

As in other viral infections, the first step of the innate immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is the production of type I and type III interferons (IFNs) along with the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (11,15,43,44,45,46). Type I and type III IFNs are produced by various cell types upon recognition of PAMPs and/or DAMPs by PRRs (11,15,43,44). IFN-I and IFN-III have different biology in terms of the structure and distribution of their surface receptors, the magnitude of their response, their kinetics, and their anatomical location (47). IFN I can prime all cells to induce the antiviral response, but IFN III activity is restricted to epithelial barrier tissue only (11,47). IFN I and IFN III signaling induces upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) such as IRF7, a transcription factor related to IRF3 (48,49,50). Stimulation of ISGs is mediated by IFN I-dependent and IFN III-dependent receptor dimerization, resulting in the recruitment and activation of a transcriptional complex termed IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3), which encompasses members of STAT1 and STAT2 family (11,15,16,21,48,49). Activated ISGF3 regulates the transcription of hundreds of ISGs that have antiviral effects, such as suppression of viral replication and transcription and degradation of viral nucleic acids (51). SARS-CoV-2 can evade innate immune recognition, signaling, IFN induction, and ISGs through the production of viral proteins blocking these pathways (15,21). Subsequently, compared with other respiratory viruses, patients with COVID-19 infection have lower levels of IFN I and IFN III in the lung or peripheral blood (15,21). IFN III and ISGs are expressed in the respiratory tract of patients with low-risk or severe disease, whereas IFN I expression may be high in the respiratory tract of patients with severe COVID-19 infection (15,16). Prolonged IFN secretion in the late phase of the disease is associated with worse clinical outcomes through the induction of chemokines recruiting inflammatory cells (16). Additionally, COVID-19 is accompanied by a relevant decrease in the number of pDCs and conventional DCs (cDCs) in the blood and lungs (52,53). MDA5 and LPG2 RNA sensors are key regulators in the induction of antiviral IFN I and play a role in limiting COVID-19 (54,55,56). Silencing or deleting genes encoding MDA5, LPG2, or MAVS in pulmonary tract epithelial cells leads to reduced IFN I production during COVID-19 (54,55,56).

Figure 2

During SARS-CoV-2 infection, NLRs and inflammasome signaling play an important role in immune defense (13,15). Inflammasome is an intracellular multiprotein complex that can be assembled by the recruitment of a variety of NLRs (11,13,15). Different inflammasome sensors are triggered in response to PAMPs and DAMPs, metabolites, potassium, and intracellular nucleic acids (11,13,15,18). The NLRP3 inflammasome can be induced downstream of TLR signaling and participates in innate sensing of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein (13,15). Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by various stimuli such as PAMPs and DAMPs results in activation of caspase-1, expression of IL-1b and IL-18, and cleavage of gasdermin (GSDM) D (57,58). NLRs respond to SARS-CoV-2 and stimulate the expression of IFN I and proinflammatory cytokines (16). High levels of IL-1b and IL-18 are associated with more severe disease and worse clinical outcomes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (59,60). SARS-CoV-2-derived PAMPs, which may be of ORF3a, ORF3b, the E protein, and viral RNA, can trigger the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome (61). NLRP3 and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-activating and recruitment domain (CARD) (ASC) puncta in monocytes and lungs in patients with COVID-19, indicating that the NLRP3 inflammasome forms in these patients (16,39). SARS-CoV-2-infected monocytes demonstrate NLRP3-dependent caspase-1 and GSDMD cleavage and IL-1b maturation (16,39). SARS-CoV-2-derived PAMPs may play a role in NLRP3 inflammasome recruitment and subsequent cytokine secretion (11,16,39). SARS-CoV-2 genome-originated single-stranded RNA, ORF3a and N protein induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human cell lines (62,63). N protein plays a dual role, on one hand, it activates the NLRP3 inflammasome, and on the other hand, it inhibits GSDMD to prevent pyroptosis and IL-1b secretion (62,63). Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 E and S proteins participate in important biological processes in macrophages (30). The E protein induces TLR2 signaling, which upregulates the production of Nlrp3 and Il1b mRNA in macrophages (30). The S protein upregulates NLRP3 inflammasome production and triggers IL-1b secretion in macrophages in patients with COVID-19 (63). In addition to NLRP3, the AIM2 inflammasome sensor, a DNA sensor found monocytes in patients with COVID-19, and the NLRC1 sensor, an intracellular sensor of bacterial peptidoglycan, may contribute to the SARS-CoV-2 response and cytokine production (64). Silencing the gene encoding NLRC1 in lung epithelial cells reduces IFN-b expression during COVID-19 infection (64). Aside from, TLRs, RLRs, and NLRs, cytosolic sensors that detect viruses and activate pro-inflammatory signaling pathways have also been identified (15,16). The cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) signaling pathway plays an important role in inhibiting the replication of both DNA and RNA viruses (65,66,67,68,69). Mitochondrial damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection releases mitochondrial DNA into the cytoplasm and activates cGAS2, promoting innate immune responses (70,71). On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a and 3CL proteins act as cGAS-STING antagonists possibly by suppressing the antiviral immune response (71).

Innate immunity triggered by PRRs activates effector immune cells to eliminate the SARS-CoV-2 virus (16). NK cells have a critical role in detecting and eradicating virus-infected cells (53). However, in patients with severe COVID-19 infection, the number of NK cells in the blood greatly reduces and there is defect a in the control of viral replication, cytokine secretion, and cell-related cytotoxicity of these cells (53). Studies conducted with single-cell RNA technologies show that NK cells display distinct gene expression signatures throughout COVID-19 infection (16). Data from a recently published study demonstrate that early expression of TGF-β is a characteristic feature of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and that this growth factor inhibits NK cell function (53). The number of alveolar macrophages, which detect the pathogen in the respiratory tract and activate other innate immune cells, is significantly reduced in severe COVID-19 (72,73). The innate immune system becomes deregulated in some individuals during severe disease (11,16,39). For example, the complement, kinin-kallikrein, and coagulation pathways are triggered in severe COVID-19 patients (15,16,74,75). The basis of this complex pathophysiology is complement C3 deregulation, which is the majority of various fatal thrombo-inflammatory processes caused by platelets, neutrophils undergoing NETosis, and inflamed vascular endothelium (74,75,76). Genetic alterations, particularly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), in genes involved in the sensing of the virus and the emergence of the innate immune response play a critical role in the pathogenesis of infection, the quality of the innate immune response, and clinical outcomes (74,75,76). Anti-interferon antibodies, observed in a small population of patients, inhibit the functions of IFNs, increasing the replication fitness of the virus, and the risk of developing severe disease and mortality rate (74,75). Recent studies have revealed that genetic alterations, especially SNPs, in genes involved in the complement and coagulation cascades predispose to severe COVID-19 (77,78,79).

3. Adaptive Immunity to SARS-CoV-2

It is well documented that adaptive immunity is a pathogen-specific immunity, which is critical in clearing SARS-CoV-2 infection and generating long-term memory (12,13,15,80,81). The adaptive immune response occurs early and is quite strong but its effectiveness decreases in severe disease (12,13). Adaptive immunity is required to restrain and eradicate SARS-CoV-2 infection (11,12,13,15,16,39). Studies with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections revealed that T cells are key players in controlling the disease and that high antibody levels lead to inflammation and worse clinical outcomes (12,13,16). The baseline viral load and, the impact of the type I interferon-mediated innate immunity are critical drivers in both the emergence of adaptive immunity and clinical outcomes (82,83,84). Persistent inflammation with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-α, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, and high levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA are among the key characteristics of severe COVID-19. Recent studies revealed that active interferon signaling contributes to the progression of acute infection to chronic disease (85).

Besides the key role of innate immunity, cellular immunity plays a critical role in the control of SARS-CoV-2 infection (26,86). Specific T cell immunity is mediated by T cells. CD8+ T cell response generally develops within 7 days, peaks at 14 days, and is associated with viral eradication and subclinical symptoms (87,88). Part of this cellular immunity may originate from bystander CD8+ T cells that are not specific to the virus but produce an NKG2D+ IL-7R+ phenotype and, in some cases, participate in limiting infection (88). While the majority of patients develop a strong cellular response, approximately 20% of patients with COVID-19 demonstrate a weak adaptive immune response and could potentially benefit from early antibody therapy (12,13). Lymphocytopenia is observed in many patients with acute infection, which is believed to promote the disease progression (12,13,15,16). Although the mechanisms underlying lymphocytopenia are unclear, the weakening of the proliferation capacity of lymphocytes and their apoptosis may be the main reasons for the decrease in the number of lymphocytes (12,13,15,16,39). Additionally, because lymphocytes express very low levels of ACE2 receptors, lymphopenia is not thought to result from SARS-CoV-2 targeting lymphocytes. Lymphopenia observed in patients with COVID-19 infection develops faster, is more pronounced, and lasts longer than those detected in other viral infections (12,13). In parallel with clinical improvement, the number of lymphocytes increases and it may take several weeks to reach the normal number (15). The functional capacity of T cell immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is a key driver of clinical outcomes (16). While type 2 CD4+ T cell phenotype is frequently detected in severe COVID-19 patients, the type I CD4+ T cell profile forms dominant CD4+ T cells, in which viral infection is effectively limited (89,90,91). The presence of high numbers of effector CD8+ T cells in acute infection results in clinical improvement, but aberrant activation of effector CD8+ T cells can have devastating consequences, for example, excessive CD8+ T cell activation in moderate disease can result in worse clinical outcomes (12,13,16,90). Due to permanent stimulation by SARS-CoV-2 antigens, CD8+ T cells can become exhausted cells, which express immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1, and PD-L1, and clinical outcomes are worse in patients with high exhausted CD8+ T cell counts (13,92). In cases of severe disease, inflammation emerges early and the adaptive immune response occurs late and is exaggerated (16). Although the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of severe infection are not clear, suboptimal activation of the type I interferon pathway as well as comorbid conditions such as older age are thought to play a critical role in the development of severe disease by suppressing the emergence of the adaptive T cell response (12,13,15,16,39).

The pattern of excessive T cell activation in acute infection suggests that the cellular response may lead to immunopathology. In the initial phase of SARS-CoV-2-induced pneumonia, high viral replication directly leads to tissue damage (93). The severity of tissue damage is the key driver in the pathogenesis of the second phase, which is characterized by the recruitment of effector immune cells leading to local and systemic inflammation (12,15,16,93). Inflammatory responses may persist after SARS-CoV-2 clearance. Severe disease is characterized by a variety of extrapulmonary diseases, such as gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary diseases, olfactory dysfunction, and cardiac diseases, as well as life threatening events including microthrombosis depozition and increased vascular permeability (94,95,96)). In addition to the direct effect of the virus on cells and vessels, secretion of soluble molecules, autoantibody-derived tissue damage and intestinal microbiota may contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of extrapulmonary disease (96). In the pathogenesis of severe disease and worse clinical outcomes, the inability of the host to mount a timely and effective immune response against SARS-CoV-2 is paramount (93,94,95,96,97). It is difficult to determine the effect of viremia levels on the course of SARS-oV-2 infection because the measurements and viral dynamics used in the studies are different (6,112,16). Early establishment of type I IFN immunity suppresses viral fitness and elicits antiviral immune responses (98). In some cases with severe disease, autoantibodies to IFN-α and IFN-γ have been detected, as well as some alterations in type I IFN-expressing genes (99,100,101). Low DC count and significant lymphocytopenia, which are important findings of severe disease, attenuate T-cell-mediated viral clearance (10,18,19). The fact that severe disease is often accompanied by an inadequate type I response and exaggerated type II immunity suggests that inappropriate adaptive immunity to the virus contributes to delayed viral elimination and disease progression (12,13,15,16). Deficiency in the modulation of inflammatory processes caused by SARS-CoV-2 is a key determinant of the pathogenesis of severe infection and worse clinical outcomes (16,102). In deceased COVID-19 patients, the fact that the active infection is mild but the recruitment of active immune cells is quite intense suggests that organ failure is not due to the virus but to overactivated immune cells and vascular damage (16). One of the landscapes of severe disease is the intense presence of immature monocytes, neutrophils, and myeloid progenitors in the circulation (103,104). Circulating myeloid cells overexpress inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, leading to vascular and organ damage (12,15). The presence of autoantibodies against nuclear antigens, phospholipids, and immune cell antigens in severe disease is an important finding of the involvement of these autoantibodies in the immunopathogenesis of severe disease (99,100). Although the underlying mechanisms are not fully known, hypercoagulable states and arterial and venous emboli are common in severe disease (105).

The antibody response is a significant arm of the adaptive immune system against viral infection and SARS-CoV-2 quickly induces the expression of IgM, IgG, and IgA Abs (15,16). Almost every individual with COVID-19 begins producing IgM and IgG Abs within two weeks of the onset of symptoms (15,16,39). Abs can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 by blocking binding of the S protein to the ACE2 receptor and can induce effector function by binding to the complement and Fc receptors (12,16). The majority of neutralizing Abs bind to epitopes in the RBD of the S protein, particularly in the receptor binding motif (RBM) (12,15,16). Although the effective neutralization level varies among individuals, neutralizing Abs are detected in convalescent sera (12,15,16). The serum titer of neutralizing anti-SARS-CoV-2 Abs is usually high in patients with severe disease (12,13,15,16). There is a strong link between neutralizing Ab levels, which block the ACE2-mediated entry of the virus into the host cell, and the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines (15,16,39). Serum titers of neutralizing Abs peak within the first few weeks following infection or vaccination and decline later, resulting in reduced protection and an increased risk of re-infection by the original strain or novel VOCs (15,16,39). Cross-reactive antibodies due to previous exposure to other coronaviruses can influence the production of neutralizing Abs to SARS-CoV-2 (12,13). The effectiveness of the humoral immune response against SARS-CoV-2 is determined by factors, such as the timing of B cell activation, and initiation and maintenance of antibody production (12,13,16). Neutralizing Abs decrease to a certain level and can remain stable for months; IgG is more stable than IgM and IgA antibodies (12,13,15,16). These kinetic properties are thought to arise from the accumulation of EF plasma cells as well as the contribution of a more long-lasting plasma-cell compartment (12). Considering that severe disease begins with high viremia, as reported in many studies, the higher antibody levels detected in these patients may result from a potent antigen-driven EF response (106). In addition to circulating antibodies, mucosal antibodies, particularly IgA, may play an important role in preventing respiratory transmission of the virus (107,108). Neutralizing IgA antibodies in nasal secretions were detected in seronegative individuals, indicating a strictly local response in the nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (109,110,111).

SARS-CoV-2 shares a low level of genome sequence similarity, including the RBD, with other human coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, but this sequence identity is immunologically important (12,16). RBD is the primary target of neutralizing antibodies (112,113). Cross-reactive memory B cells generated during previous coronavirus infections may accelerate antibody response (106). Neutralizing Abs to SARS-CoV-2 isolated from COVID-19 patients were demonstrated to cross-react with human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 (114). Neutralizing Abs binding the spike proteins were detected in blood samples obtained from healthy controls before the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that it is linked to cross-reactivity with human coronaviruses that cause common cold (115). Studies conducted in healthy cohorts in Canada and sub-Saharan Africa revealed the presence of antibodies cross-reactive with spike protein in the blood of healthy individuals (116,117). These cross-reactions are likely due to antibodies that target the S2 domain of the S protein; thought to be by the strong selective pressure of the immune system (118). The presence of high levels of cross-reactive antibodies may contribute to a milder clinical picture (119,120). Considering that cross-reactive T cells are common among SARS-CoV-2 naive individuals, these cells are likely an important variable in shaping the clinical picture of COVID-19 (12). Autoantibodies are frequently detected in viral infections, which arise as a result of autoantibody secretion from dying cells, inflammation, and molecular mimicry (121,122). SARS-CoV-2 causes a significant increase in the levels of autoantibodies, which target a broad spectrum of autoantigens, such as complement peptides, and cytokines (123). Bastard et al. reported the frequency of autoantibodies against type I IFN as 10,2% in COVID-19 patients (101). Autoantibodies against type I IFN that emerged during SARS-CoV-2 infection can recognize and neutralize type I IFNs, a key cytokine in the regulation of antiviral defenses (101,123). In another study, autoantibodies against IL-1R were found in 62% of children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (124). Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of previous COVID-19 disease in preventing re-infection and subsequent severe disease (123,124,125). A recently published meta-analysis investigating the protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection showed that protection was a high infection caused by ancestral, alpha, beta, and delta variants, but significantly lower in the Omicron BA.1 variant (126).

4. Immune Evasion Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2

For the virus to escape immune recognition, the viral genomic RNA must be translated according to host translation rules (21,22). To achieve this, SARS-CoV-2 modifies the 5′-RNA triphosphatase of their genomic RNA and sgRNA through capping and methylation (21,22). Initially, the virus can evade host recognition by disguising its mRNA as the host’s mRNA, but, over time, viral RNA production increases, and dsRNA intermediates are formed, which are detected by PRRs (127,128). The assembly of RNA transcripts increases dsRNA formation, which is perceived by the host immune system before the virus can complete its life cycle, limiting viral infection to the first infected cells (21,22). Therefore, before dsRNA generation, the virus uses mechanisms to prevent the assembly of dsRNA and hide it from the host immune recognition (21,22). Studies have revealed that the Nsp15 decreases the assembly of negative-stranded RNA and dsRNA through its endonuclease function (129,130). The virus also alters its replication kinetics in its favor by promoting the recruitment of double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) (131,132). These structures reduce the capacity of the host immune system to recognize pathogens by using autophagy mechanisms (133,134,135,136). Nsp3 and Nsp4 mediate the accumulation of DMVs, while Nsp6 constitutes a link to the endoplasmic reticulum that provides the flow of lipids (135). SARS-CoV-2 can achieve optimal infection with low infection multiplicity, so the virus does not produce large amounts of dsRNA before DMV generation (137).

Figure 3.

Restrain of host recognition is one of the relevant immune evasion strategies of SARS-CoV-2. Following the formation of viral DMVs, viral transcripts leave these structures and enter the cytosol, where they are translated and virion aggregation begins (138). As viral replication accelerates, it becomes impossible for the virus to escape detection by host sensors, and once recognized, the virus can evade immune screening by inhibiting cellular signaling pathways and delaying the generation of innate and adaptive immune responses (138). The N protein, an RNA-binding protein is crucial during the packing of the viral genome into virions and evading the virus from the cellular and humoral immunity (139,140). Additionally, the ability of N to engage free RNA may contribute to the virus evading the immune response (141,142,143). Recent trials have demonstrated a strong relationship between the potent IFN antagonism observed in the Alpha (B.1.1.7) VOC and high levels of N protein production (144,145).

Another evidence that the N protein functions as an IFN antagonist is that a recent study showed that N protein fragments produced by host caspase 6 inhibited the host IFN response (146).

SARS-CoV-2 can also evade the advanced immune surveillance mechanisms by inhibiting cellular innate immune signaling (22). SARS-CoV-2 generates replication intermediates and promotes the mounting of stress granules, which function as a platform for activation of the RLR signaling pathway (40,147). Recognition of viral PAMPs by host sensors, including single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), induces recruitment of the MAVS-orchestrated mitochondria-localized signaling center and results in the production of host kinases IKKα, IKKβ, and TBK1 (21,147). Kinase activation promotes the expression of IFNβ by IRF3 and NF-κB transcription factors. IFN1β triggers antiviral activity in cells (21,147). Nsp5 protein can inhibit the generation of these stress granules by engaging both RNA and a specific factor called G3BP1 (147). SARS-CoV-2 proteins, among their many biological functions, can inhibit PRR function (21,22). Recent studies have shown that N protein binds to the DExD/H box RNA helicase domain of RIG-I and interrupts its crosstalk with TRIM25, a cellular ubiquitin ligase that accentuates RLR signaling (147,148,149). Additionally, the Nsp3 protein may exert an antagonistic effect on the conjugation of an ISG to MDA5 (150,151). The Nsp3 protein may play a more critical role in the immune evasion of the virus due to its ability to interfere with alterations of other proteins, including ubiquitin and/or ADP-ribose conjugations (150,151). The virus cannot completely evade host immune surveillance, so some viral components target host factors further downstream in the signaling pathway, allowing the virus to inhibit the mounting of antiviral immunity (21,26). Several studies have reported that SARS-CoV-2 may inhibit MAVS biology by its proteins, such as N, M, Nsp5, and ORF7b (147,148,149,150,151,152,153). N may interfere with MAVS polyubiquitination and assembly depending on the N dimerization site which is required for liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) of N (154). LLPS of N crosstalks with stress granules and NF-κB signaling pathway and promotes immune escape of virus (154). Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 can cause direct ubiquitination and degradation of MAVS via Nsp5 protein (155). Similarly, it has been suggested that the M protein inhibits the capacity of MAVS to form the scaffolding required for downstream transcription factor activation (156). Experimental studies have shown that M, Nsp6, Nsp13, ORF7a, and ORF9b interfere with the function of host factors that participated in MAVS signaling such as TBK1 that trigger IRF activation (157,158,158,159). Nsp6, Nsp13, and ORF9b block the phosphorylation-mediated activation of TBK1, while M and ORF7a reduce TBK1 expression (160,161,162). SARS-CoV-2 induces NFκB activation despite involvement in antiviral signaling (163). It has been reported that S, Nsp3, and Nsp5 proteins reduce the production of IRF3, while Nsp5, Nsp12, ORF3b, and M hamper the nuclear migration of IRF3 (164,165,166). Although the mechanism is not clear, Nsp1 has also been shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of IFR3 (167).

Another innate immune evasion mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 is that the virus restrains interferon signaling (168). Single-cell RNA technologies revealed that approximately 60% of the total mRNA in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells was of virus origin (168). The key dynamics of this finding are that the Nsp1 protein mediates hos mRNA repression and transcription of high levels of viral genomic RNA and sgRNA (169). Nsp10 and Nsp14 proteins may also contribute to this process (170,171). Although the host has strong antiviral mechanisms, the virus eventually leads to cell death via a variety of pathways, allowing the virus to be recognized by phagocytic cells (172,173). This biology can explain the high levels of IFN I and IFN III observed in COVID-19 (174,175). Since, this biology is difficult to inhibit, SARS-CoV-2 may target the signaling pathway responsible for responding to IFN I and IFN III and promoting ISG production (174,175). Nsp13 and Nsp19 proteins block IFN-I signaling by decreasing the production of the IFNAR1 subunit (176). Nsp13 and S crosstalk with STAT1 signaling, preventing its binding to the receptor and activation (165,177).

Additionally, Nsp1, Nsp10, and Nsp14 also interfere with ISG expression by reducing the production of host transcript (168,169). Interference with the generation of ISG is important for viruses; because the replication capacity of the viruses is quite low in cells primed with IFN I and IFN III, and it also gives time for the host to strengthen its immune response.

(178). The virus can also escape immune surveillance and clearance by blocking the nuclear transport mechanism (18,20). Some virus lineages use the nuclear pore complex (NPC) machinery to block the host effect on limiting viral replication ((179,180,181). Many SARS-CoV-2 proteins, such as Nsp9, ORF6, and M protein can interact with the host nuclear transport mechanism (182,183). Recently, researchers have demonstrated that ORF6 inhibits nucleocytoplasmic transport and exerts a potent anti-IFN activity (184,185,186)

Many viruses, in addition to interfering with the activation of the host antiviral mechanisms, also inhibit host protein synthesis to increase replication capacity (187). Recent trials have revealed that Nsp1 is a protein that shuts down host translation and blocks mRNA entry into the ribosome by different mechanisms (188). Even in the absence of other viral proteins, a strong reduction in the translation of endogenous proteins is observed in cells (21). It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 Nsp8 and Nsp9 proteins engage the signal recognition particle (SRP) complex and interfere with its function, disturbing the integrity of the protein and causing degradation of novel translated proteins (187,188). This process results in reduced integration of SRP-dependent membrane proteins into the cell membrane (188).

The Nsp1 protein prevents the mRNA entry channel to the ribosome by binding to the 18S ribosomal RNA component of the 40S ribosomal subunit (189,190). The C terminus of the Nsp1 protein displays significant structural similarity to SERBP1 and Stm1, which prevent mRNA from reaching the entry channel of the 40S ribosome (189). When the C-terminal domain of Nsp1 is mutated to prevent the interaction with the ribosome, translational repression is abolished (189,190). This interaction between Nsp1 and ribosome is accompanied by a strong reduction in the translation of endogenous proteins in cells (189,190,191). Despite many studies, it has not been elucidated whether mRNA containing 5′ viral leader sequence is protected from Nsp1-mediated translation inhibition (191,192,193,194). In these studies, the 5′ and/or 3′ untranslated region of SARS-CoV-2 were fused to a reporter gene, so other properties of the viral mRNA may play a role in escaping translational shutoff (190). The inclusion of the viral 5′ UTR increases reporter mRNA translation by 5-fold, indicating that viral mRNA is more efficient than host mRNA in reporter mRNA translation (190). Alternatively, the Nsp1 protein can trigger the degradation of mRNAs that lack the viral 5′ viral leader sequence, thus enabling viral mRNAs to be translated over cellular mRNAs (194).

Figure 4.

5. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines-Generated Immunity and Variants

The knowledge that attenuated pathogens or pathogen fragments stimulate the host immune response has been known for approximately 1000 years (195). Over the last 200 years, many vaccination methods have been developed to protect people against different infections (12,16,39). The COVID-19 pandemic has provided unprecedented insights into the interaction of the immune system with SARS-CoV-2, and this information has paved the way for the development of highly effective vaccines approximately 1 year after the onset of infection (15,16,24,196)). The first vaccines were produced with mRNA technology and provided strong antiviral immunity against SARS-CoV-2 (15,16). However, the antibody response that develops due to vaccines rapidly drops below the productive level (187,197,198,199,200,201,202,203). When the first vaccines were administered the pandemic was already well-established in populated parts of the world (80,81,204). The development of 100,000 new infections every week worldwide has led to the emergence of novel variants that can cause infection in vaccinated people (81). The decrease in the level of nAbs in the vaccinated population and the emergence of novel variants led to breakthroughs in the pandemic (80,81).

Considering those current COVID-19 vaccines generally neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 prototype and have limited effects on VOCs, such as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron, it is clear that vaccines with broad neutralizing effects are needed (12,15,24,39,120). Recently, researchers have reported the development of antibodies targeting RBD that can neutralize all VOCs (15,81). After the 3rd dose of the vaccine, an increase in the level and effectiveness of nAbs is observed (15,24). Vaccination programs implemented in hundreds of thousands of people have demonstrated that COVID-19 vaccines protect against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs in addition to wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (201,202,203,204,205). In the phase 3 trial in the USA, before the omicron variant, the protective effectiveness of the mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 was determined as 94%, and the protective effectiveness of the Ad26 vaccine was determined as 95% (203,206,207). While 70% of people in developing countries are vaccinated, the rate of vaccinated individuals in Africa is 15% (203,206,208). Adenovirus vector-based vaccines are more stable than mRNA vaccines, do not require freezing, and are generally used in developing countries (206). The rate of development of severe disease in vaccinated people is lower than in unvaccinated individuals, so it is critical to strengthen the protective effectiveness of the vaccine (209,210). In developed countries, the third dose of vaccine is administered to strengthen and prolong the immune response (211,212). Additionally, a 4 th dose of vaccine is recommended for people at high risk of developing severe disease (212). The protective value of immunity provided by vaccines against the omicron variant is low (213,214,215).

In vaccinated people, SARS-CoV-2 can cause a mild disease that resolves without causing fatal complications (81,209). It has been shown that people who have had COVID-19 have nAb levels comparable to the individuals who have been vaccinated 3 doses (216,217,218).

In breakthrough infection that develops in vaccinated individuals, there is heterogeneity in terms of the total number of antigens and variants (81,216). A recent study reported that the immunity profiles of patients infected with the variant virus after administering 2 doses of mRNA vaccine and those of people administered 3 doses of the vaccine were different (81). The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines is poor in patients with chronic disease and patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy (80,219,220,221,222,223). These studies generally investigated the level of specific immune response induced by the COVID-19 vaccine in patients with specific diseases (219,220,221,222,223). In a recent prospective study, researchers investigated cellular and humoral immune responses to COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, and 12% of patients failed to develop nAbs, while 27% developed low levels of nAbs (80). Although cross-reactive T-cell responses persisted in all participants, nAb responses to the omicron variant have been detected to be reduced. BNT162b2 generated higher antibodies but lower T cell responses compared to ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination (80).

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines trigger the production of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) (202,203). mRNA vaccines induce the production of high levels of nAbs, but neutralizing antibodies begin to wane within 3-6 months (202,203). In contrast to mRNA vaccines, Ad26 COV2.S vaccines lead to lower levels of nAbs production (202,203,206). nAbs induced by Ad26.COV2. S vaccines are more stable and long-lasting than mRNA vaccines (206). At 8 months antibody levels are similar between BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2. S (224,225). The waning of mRNA-induced immunity is accompanied by an increase in the frequency of breakthrough infection (211,225,226). Several studies have demonstrated that hybrid immunity (i.e., the immunity conferred by the combination of previous infection and vaccination) elicits higher levels of nAbs and enables stronger protection against infection than immunity provided by vaccination or infection alone (211,219,225,226,227,228). COVID-19 vaccines, particularly Ad26.COV2. S, induce a strong and long-lasting long-lasting CD8+ T cell response, usually 6-8 months (219,229,230). Since CD8+ T cells can significantly limit the replication rate of SARS-CoV-2 the protective effect of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines continues for a long time, even if serum nAbs levels decrease (231,232). Germinal center B cells can be detected in the serum 6 months after BNT162b2 vaccination (229,230).

SARS-CoV-2 VOCs Alpha, Delta and then Omicron became dominant globally (205,234). VOCs can evade the nAb response produced by previous infection or vaccination through in RBD, the key antigenic region of the S protein (205,234). Omicron is the most vaccine-resistant and is the first VOC to form different globally dominant subvariants (205,234). Omicron harbors 30 mutations in RBD (14,16,17,234). Boosted vaccination provides a notable increase in the titer of Omicron nAbs, but the Ab titer usually decreases after 4 months of the 3rd vaccination (14,16,219). Hybrid immunity enables more permanent protection (211,219,235, 236,237,238,239,240, 241). Vaccine-generated nAbs have limited cross-reactivity to Omicron but vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell responses display potent cross-reactivity to Omicron (231,241). Although the two-shut COVID-19 vaccines, BNT162b2.S and BNT162b2 vaccines, administered during the omicron surge in South Africa, did not lead to the production of high levels of Omicron-neutralizing antibodies, the significant decrease in hospitalization rates indicates that other immunological variables, such as CD8+ T cell responses, also play a role (240).

6. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has had a dramatic impact on global health, affecting 0,75 billion people worldwide and causing the deaths of 7 million people. SARS-CoV-2 infections can lead to a wide range of clinical manifestations including asymptomatic, mild, and severe cases. The rapid detection of the virus and the development of highly effective vaccines in unprecedented cooperation at the beginning of the pandemic were impressive achievements of researchers. However, challenges remain, such as inadequate vaccine distribution, especially in Africa, and the possibility of novel variants emerging.

Innate and adaptive immunity are essential in mounting an effective response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and clearing the virus; however, they can contribute to inflammation resulting in unfavorable clinical outcomes. Although recent studies have indicated that the severity of the disease correlates with immune dysregulation, the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and the molecular mechanisms of inflammation have not been fully elucidated. Innate immunity is crucial in building an effective response to SARS-CoV-2. Innate immune cells perceive the virus through PRRs and activate the antiviral response by the production of type I and III interferon (IFN) and proinflammatory soluble molecules. Although its critical role in viral clearance is known, the function of adaptive immunity in the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 is unclear. mRNA-, adenoviral vector-, and recombinant protein-based vaccines show 74% to 95% efficacy against symptomatic disease, however, antiviral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 weakens over time due to waning immunity and the emergence of novel variants that evade immune recognition and clearance. In addition to having strong immunogenicity, mRNA vaccines have been shown to cause persistent germinal center reactions and excessive IgG4 antibody production. Vaccine adaptations need to be developed for variants that can escape immune attacks. mRNA and viral vector vaccines are effective in inducing T-cell immunity as well as humoral responses. It would be valuable for future studies to investigate the contributions of other adaptive immune responses, such as non-neutralizing antibodies and T cells, in protection. The mucosal immune response is important in protecting against infection, and unfortunately, current COVID-19 vaccines can not generate sufficient numbers of memory T cells in the mucosa. Therefore, intensive research on mucosal vaccine platforms is required to achieve mucosal immunity through vaccination.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowlegment

I would like to thank Nilgün Akkız, MD, PhD, for her scientific contributions to the preparation of this review article, and Anıl Delik PhD, Biologist, who prepared the up-to-date Figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 19, SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, PAMPs: pathogen-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs; danger-associated molecular patterns, PRRs: pattern recognition receptors, RLRs: RIG-I-like, TLRs: Toll-like receptors, VOCs: variants of concern, RBD: receptor-binding domain, ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, ORFs: open reading frames, NSPs: nonstructural proteins, ILCs: innate lymphoid cells, NK. natural killer, pDCs: plasmacytoid dendritic cells, dsRNA: double-stranded RNA, ssRNA: single-stranded RNA, NOD: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, AIM2: absent in melanoma 2, MAPKs: mitogen-activated protein kinases, IFN: interferon, IRFs: regularly factors, sgRNA: sub genomic RNA, MAVS: mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein, TRAF: TNF receptor-associated factor, TBK: TANK-binding kinase, ISGs: interferon-stimulated genes, GSDM: gasdermin, CARD: caspase-activating and recruitment domain, DMVs: double-membrane vesicles, LLPS: liquid-liquid phase separation, NPC: nuclear pore complex.

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World-Health-Organization. (https:/covid19.who.int/,2023), vol. 05-01-2023.

- Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Kakizaki, M.; Shiwa-Sudo, N.; Okura, T.; Tahara, M.; Fukushi, S.; Maeda, K.; Kawase, M.; Asanuma, H.; Tomitaet, Y.; et al. Essential role of TMPRSS2 in SARS-CoV-2 infection in murine airways. Nat Commun, 2022; 13, 6100. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkız, H. Implication of the Novel Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Genome for Transmission, Disease Severity, and the Vaccine Development. Front Med 2021, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, R.; Kumari, S.; Pandey, B.; Mistry, H.; Bihani, S.C.; Das, A.; Prashar, V.; Gupta, G.D.; Panicker, L.; Kumar, M. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J Mol Biol 2021, 433, 166725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesier, D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 180, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, B.L.; Chen, MT.K.; Csiba, K.; Meng, B.; Gupta, RK. SARS-CoV-2 and innate immunity: the good, the bad, and the ‘’goldilocks’’. Cell & Mol immunobiology 2024, 21, 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, M.S.; Kanneganti, T.-D. Innate immunity: the first line of defense against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. the humoral response and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol 2022, 23, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapuente, D. B-cell and antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2: infection, vaccination, and hybrid immunity. Nat Cell & Mol Immunol 2024, 21, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Knopf, J.; Herrman, M. , lin, L. ; Jiang, J.; Shao, C.; Li, P.; He, X.; et al. Immune response in COVID-19: what is next? Cell Death & Dis 2022, 29, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Merad, M.; Blish, C.A.; Sallusto, F.; Iwasaki, A. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science 2022, 375, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbiakha, B.; Sahler, J.M.; Buchholz, D.W.; Ezzatpour, S.; Jager, M.; Choi, A.; Monreal, I.A.; Byun, H.; Adeleke, R.A.; Leach, J. , et al. Adaptive immune cells are necessary for SARS-CoV-2-induced pathology. Science 2024, 10, 5461. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X. , and Zhang, B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduction & Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 235–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hope JL and Bradley, LM. Lessons in antiviral immunity. Science 2021, 371, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, L.; Piontivska, D.; Figueiredo-Campos, P.; Fanczal, J.; Ribeiro, S.P.; Baptista, M.; Ariotti, S.; Santos, N.; Amorim, M.J.; Pereira CS, et al. CD8+ tissue-resident memory T-cell development depends on infection-matching regulatory T-cell types. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Minkoff JM & tenOever, B. Innate immune evasion strategies of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thome, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, Y.; Zhu, B.; Jang K & Yoo, JS.; Jang K & Yoo JS. Innate immune sensing of coronavirus and viral evasion strategies. Exp Mol Med. 2021, 53, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Gan, H.; Ma, Y.; Xu, L.; Cheng, Z.J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Sun, J.; Sun, B. and Hao, C. The molecular mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 evading host antiviral innate immunity. Virology Journal 2022, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, M.S.; Lambris, J.D.; Ting JP and Tsang, JS. Considering innate immune responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, E.A.; Diamond, MS. Host cell-intrinsic innate immune recognition of SARS-CoV-2. Curr Opin Virol 2021, 52, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. & Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and disesases. Signal Transduction & Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 291. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. & Zhao, Y. Toll-like receptors and immune regulation: their direct and indirect modulation on regulatory CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Immunology 2007, 122, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akira S & Takeda, K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2004, 4, 499–511. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Karki, R.; Williams, E.P.; Yang, D.; Fitzpatrick, E.; Vogel, P.; CB Jonsson, TD Kanneganti. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, I.; Kanneganti TD & Del Sol, A.; Kanneganti TD & Del Sol, A. Fostering experimental and computational synergy to modulate hyperinflammation. Trends Immunol 2022, 43, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.; Zhao, J.; Fleming, E.; Lane, T.E.; McCray Jr, P.B. , & Perlman, S. (2012). Intranasal treatment with poly (I· C) protects aged mice from lethal respiratory virus infections. Journal of virology, 86(21), 11416-11424.

- Bernard, D.L.; Day, C.W.; Bailey, K.; Heiner, M.; Montgomery, R.; Lauridsen, L.; Chan, PK.S.; Sidwell RW, et al. Evaluation of immunomodulators, interferons and known in vitro SARS-CoV inhibitors for inhibition of SARS-CoV replication in BALB/c mice. Antivir Chem Chemother 2006, 17, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totura, A.L.; Whitmore, A.; Agnihothram, S.; Schäfer, A.; Katze, M.G.; Heise, M.T.; Baric, R.S. Toll-like receptor 3 signaling via TRIF contributes to a protective innate immune response to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. mBio 2015, 6, e00638–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury A & Mukherjee, S. In silico studies on the comparative characterization of the interactions of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein with ACE-2 receptor homologs and human TLRs. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Kuang, M.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Jia, Z.; Guo, X.; Y Hu, J Kong, H Yin, X Wang, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein interacts with and activates TLR41. Cell Res 2021, 31, 818–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruk, G.; Puthia, M.; Petrlova, J.; Samsudin, F.; Strömdahl, A.C.; Cerps, S.; Uller, L.; Kjellström, S.; Bond, P.T.; Schmidtchen, A. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and boosts proinflammatory activity. J Mol Cell Biol 2020, 12, 916–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoresen, D.; Wang, W.; Galls, D.; Guo, R.; Xu, L. , & Pyle, A.M. The molecular mechanism of RIG-I activation and signaling. Immunol Rev 2021, 304, 15168. [Google Scholar]

- Yaugel-Novoa, M.; Bouriet T & Paul, S. ; Bouriet T & Paul, S. Role of the humoral immune response during COVID-19: guilty or not guilty? Mucosal Immunology 2022, 15, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Onomoto, K.; Onoguchi, K.; Yonayama, Y. Regulation of RIG-I-like receptor-mediated signaling: interaction between host and viral factors. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo YM & Gale, M. Immune signaling by RIG-I like receptors. Immunity 2011, 34, 680–692. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, S.M.; Liu, H.; Park, H.S.; Briley, J.; Gale, M. Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, 14590–14595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMicking, J.D. Interferon-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Ding, C.; Qian, K.; Liao, Y. The interplay between coronavirus and type I IFN response. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 805472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Dong, X.; Ma, R.; Wang, W.; Xiao, X.; Tian, Z.; C Wang, Y Wang, L Li, L Ren, et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Shin, EC. The type I interferon response in COVID-19: implications for treatment. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins JW & Diamond, MS.; Schoggins JW & Diamond MS. Shared and distinct functions of type I and type III interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Genin, P.; Mamane Y & Hiscott, J. ; Mamane Y & Hiscott, J. Selective DNA binding and association with the CREB binding protein coactivator contribute to differential activation of alpha/beta interferon-A genes by interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20, 6342–6353. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, P.; Bragança, J.; Bandu, M.T.; Lin, R.; Hiscott, J.; Doly, J. , & Civas, A. Preferential binding sites for interferon regulatory factors 3 and 7 involved in interferon-A gene transcription. 2002, 316, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Marie, I.; Durbin JE & Levy, DE. ; Durbin JE & Levy DE. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-α genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO 1998, 17, 6660–6669. [Google Scholar]

- Platanitis, E.; Demiroz, D.; Schneller, A.; Fischer, K.; Capelle, C.; Hartl, M.; Müller, M.; Novatchkova M & Decker, T. A molecular switch from STAT2-IRF9 to ISGF3 underlies interferon-induced gene transcription. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Park, S.; Jeong, H.W.; Ahn, J.Y.; Choi, S.J.; Lee, H.; Choi, B.; Nam, S.K.; Sa, M.; Kwon J-S, et al. Immunophenotyping of COVID-19 and influenza highlights the role of type I interferons in development of severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol 2020, 5, eabd1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withkowski, M.; Tizian, C.; Ferreira-Gomez, M.; Niemeyer, D.; Jones, T.C.; Heinrich, F.; Frishchbutter, S.; Angermair, S.; Hohnstein, T.; Mattiola I, et al. Untimely TGFB responses in COVID-19 limit antiviral functions of NK cells. Nature 2021, 600, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Riva, L.; Pu, Y.; Martin-Sancho, L.; Kanamune, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; K Sakai, S Gotoh, L Miorin, De Jesus PD, et al. MDA5 governs the innate immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in lung epithelial cells. Cell Rep 2021, 34, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Geng, T.; Harrison AG & Wang, P.; Harrison AG & Wang, P. Differential roles of RIG-I like receptors in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mil Med Res 2021, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebendenne, A.; Chaves Valadão, A.L.; Tauziet, M.; Maarifi, G.; Bonaventure, B.; McKellar, J.; Planès, R.; Nisole, S.; Arnaud-Arnould, M.; Moncorgé, O.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 triggers an MDA-5-dependent interferon response which is unable to control replication in lung epithelial cells. J Virol 2021, 95, e02415–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christgen S & Kanneganti, TD. Inflammasomes and the fine line between defense and disease. Curr Opin Immunol 2020, 62, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki, N.; Kornfeld, O.S.; Lee, B.L.; Stowe, I.B.; O’Rourke, K.; Li, Q.; Sandoval, W.; Yan, D.; Kang, J.; Xu, M.; et al. NINJ1 mediates plasma membrane rupture during lytic cell death. Nature 2021, 591, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; C Xie, K Ma, K Shang, W Wang. ; et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, A.G.; Lorenc, A.; Del Molino Del Barrio, I.; Das, A.; Fish, M.; Monin, L.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; McKenzie, D.R.; Hayday, T.S.; Francos-Quijorna, I.; et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.S.; Nabar, N.R.; Huang NN & Kehrl, JH.; Huang NN & Kehrl JH. SARS-coronavirus open reading frame-8b triggers intracellular stress pathways and activates NLRP3 inflammasomes. Cell death Discov 2019, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, P.; Shen, M.; Yu, Z.; Ge, W.; Chen, K.; Tian, M.; Z Wang, J Wang, Y Jia. ; et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation to induce hyperinflammation. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, M.; Shao, F.; Yu, D.; Ma, J.; Z Wang, J Wang, Y Jia. ; et al. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid suppresses host pyroptosis by blocking gasdermin D cleavage. EMBO 2021, 40, e108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, C.; Crespo, Â.; Ranjbar, S.; Lewandrowski, M.; Ingber, J. , de Lacerda, L.B.; Parry,B.; Ravid, S.; Clark, S.; Hoet, F, al. SARS-CoV-2 infects blood monocytes to activate NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes, pyroptosis and cytokine release. Preprint at medRxiv 2021.

- Franz, K.M.; Neidermyer, W.J.; Tan, Y.J.; Whelan SPJ & Kagan, JC. STING-dependent translation inhibition restricts RNA virus replication. Proc Acad Sci USA 2018, 115, E2058–E2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W.; MacDuff, D.A.; Imanaka, N.; Gainey, M.D.; Shrestha, B.; Eitson, J.L.; Mar, K.B.; Richardson, R.B.; Ratushny, A.V.; Litvak, V.; et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature 2014, 505, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Jacobs, S.R.; West, J.A.; Stopford, C.; Zhang, Z.; Davis, Z.; Barber, G.N.; Glaunsinger, B.A.; Dittmer, DP and Damania, B. Modulation of the cGAS-STING DNA sensing pathway by gammaherpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015, 112, E4306–E4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briard, B.; Place DE & Kanneganti, TD.; Place DE & Kanneganti TD. DNA sensing in the innate immune response. Physiology 2020, 35, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen X & Chen, ZJ.; Chen X & Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Chaubey, G.; Chen JY & Suravajhala, P.; Chen JY & Suravajhala, P. Decoding SARS-CoV-2 hijacking of host mitochondria in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Am J Physiol 2020, 319, C258–C67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Y.; Su, J.; Shen, S.; Hu, Y.; Huang, D.; Zheng, W.; M Lou, Y Shi, M Wang, S Chen. ; et al. Unique and complementary suppression of cGAS-STING and RNA sensing-triggered innate immune responses by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wen, Y.; Xu, G. ; Zhao, L Cheng, J Li, X Wang, F Wang.; et al. (2020). Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nature medicine, 26(6), 842-844.

- Delorey, T.M.; Ziegler, C.G.; Heimberg, G.; Normand, R.; Yang, Y.; Segerstolpe, Å.; Abbondanza, D.; Fleming, S.J.; Subramanian, A.; Montoro, DT.; et al. COVID-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature, 2021;595(7865): 107-113. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf, J.; Leppkes, M.; Schett, G.; Hermann, M.; Munoz, LE. Aggregated NETs sequester and detoxify extracellular histones. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, C.; Janko, C.; Munoz, L.E.; Zhao, Y.; Keinhofer, D.; Frey, B.; Lell, M.; Manger, B.; Rech, J.; Naschberger, E.; et al. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat Med 2014, 20, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppkes, M.; Knopf, J.; Naschberger, E.; Lindemann, A.; Singh, J.; Hermann, I.; M Stürzl, L Staats, Mahajan, A. ; Schauer, C.; et al. Vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. EBiomedicine 2020, 58, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pairo-Castineria e, Clohisey, S. ; Klaric, L.; Bretherick, A.D.; Rawlik, K.; Pasko, D.; Walker, S.; Parkinson, N.; Fourman, M.H.; Russell, CD.; et al. Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in COVID-19. Nature 2021, 591, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative: Mapping the human genetic architecture of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 600, 472–477. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalil, A.C.; Mehta, A.K.; Patterson, T.F.; Erdmann, N.; Gomez, C.A.; Jain, M.K.; Wolfe, C.R.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Kline, S.; Pineda, JR.; et al. Efficacy of interferon beta-1a plus remdesivir compared with remdesivir alone in hospitalized adults with COVID-19: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021, 12, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.; Goodyear, C.S.; Willicombe, M.; Gaskell, C.; Siebert S, de Silva, T. I.; Murray, S.M.; Rea, D.; Snowden, J.A.; Carrol, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific immune responses and clinical outcomes after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with immune-suppressive disease. Nat Med 2023, 29, 1760–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusnik, J.; Monzon-Posadas, Zorn, J. ; Peters, K.; Baum, M.; Proksch, H.; Schelüter, C.B.; Alter, G.; Menting T & Streeck, H. SARS-CoV-2 humoral and cellular immunity following different combinations of vaccination and breakthrough infection. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pujadas, E.; Chaudhry, F.; McBride, R.; Richter, F.; Zhao, S.; Wajnberg, A.; Nadkarni, G.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Houldsworth, J, and-Cardo, C. SARS-CoV-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality. Lancet Respir Med. 2020, 8, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]