Submitted:

22 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

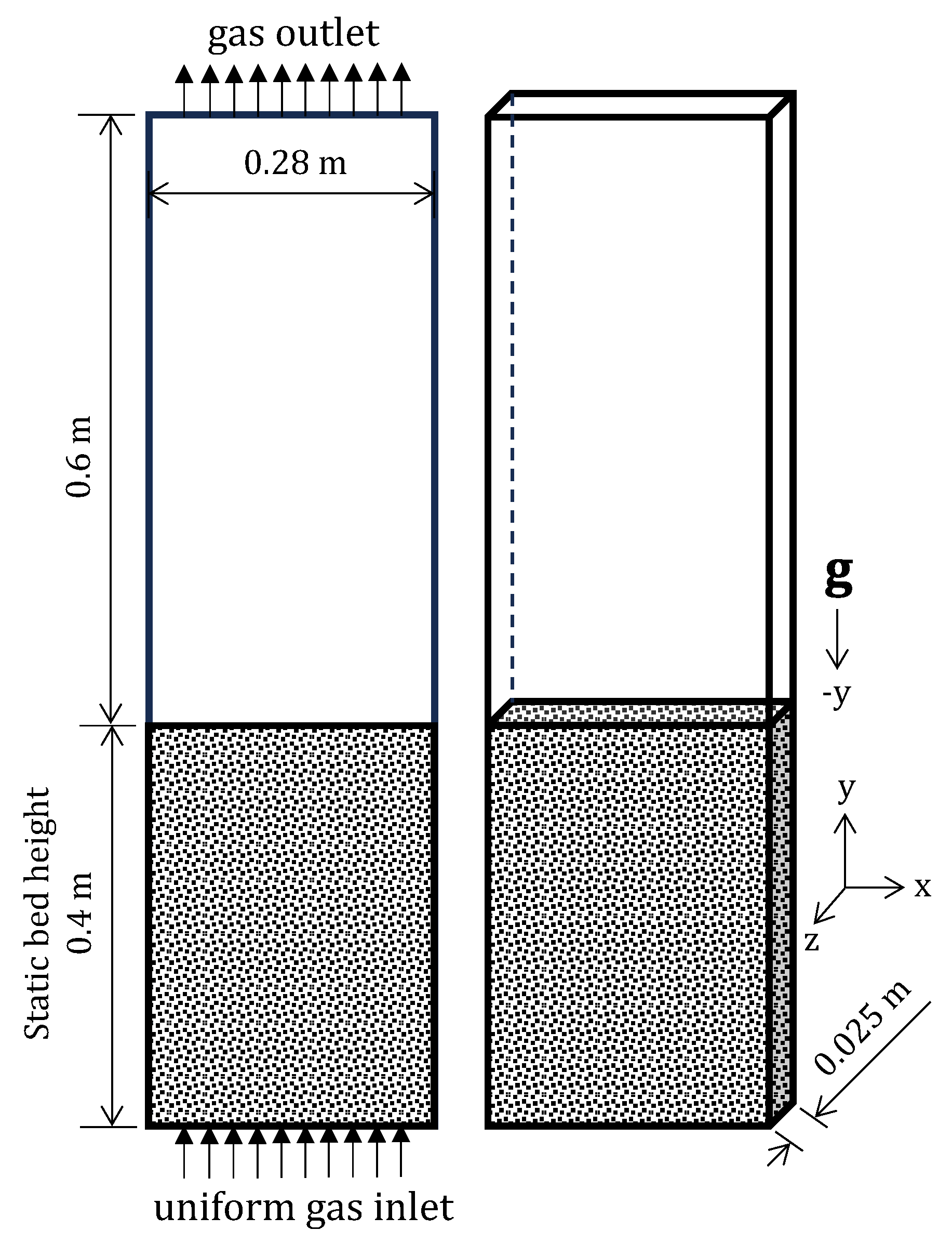

2. Problem Description

3. Computational Model

3.1. Governing Equation

Mass balance equations

Momentum balance equations

Syamlal-O`Brien drag model [20]

Gidaspow drag model [5]

Solid phase fluctuating energy equations [28]

3.2. Simulation Setup

4. Results

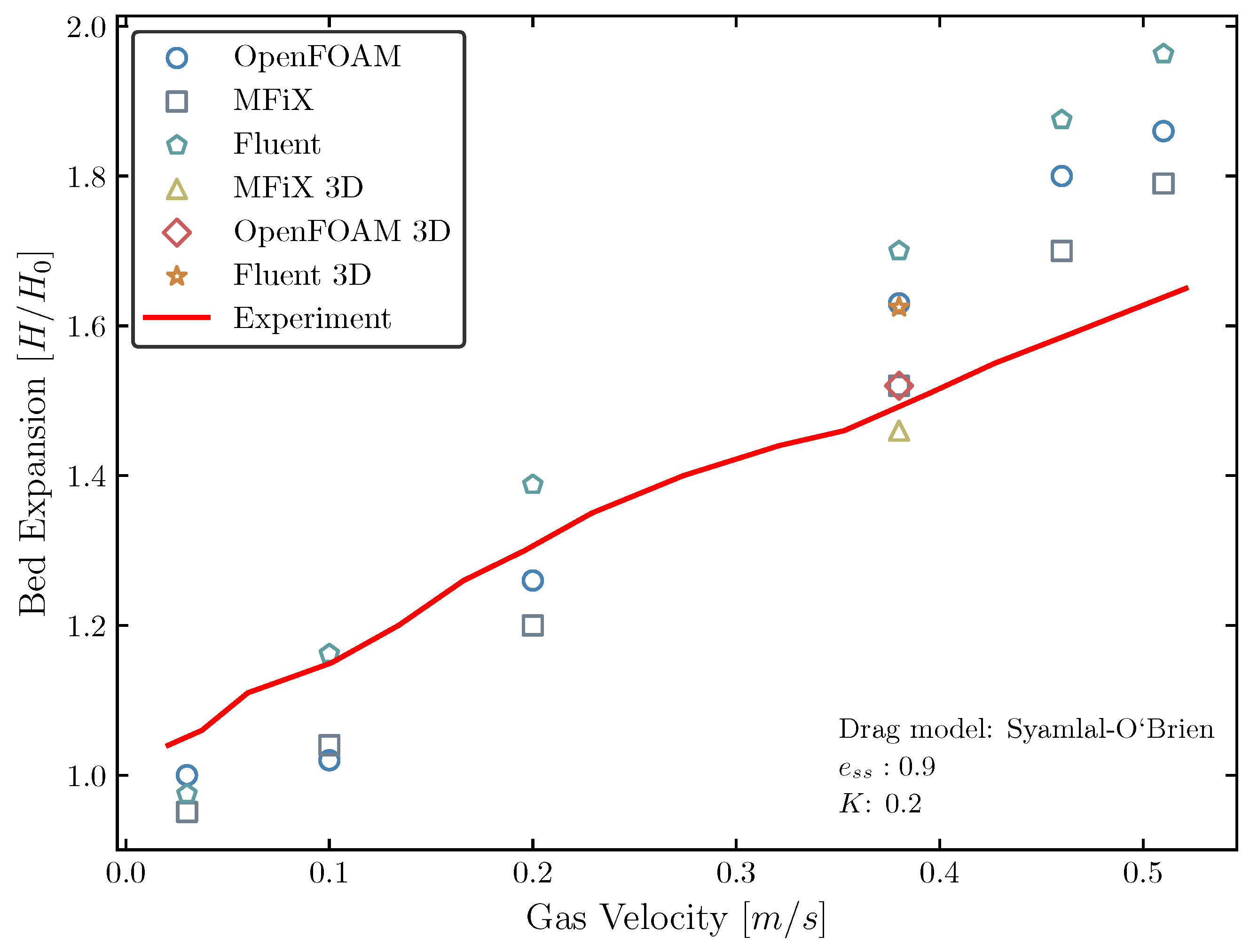

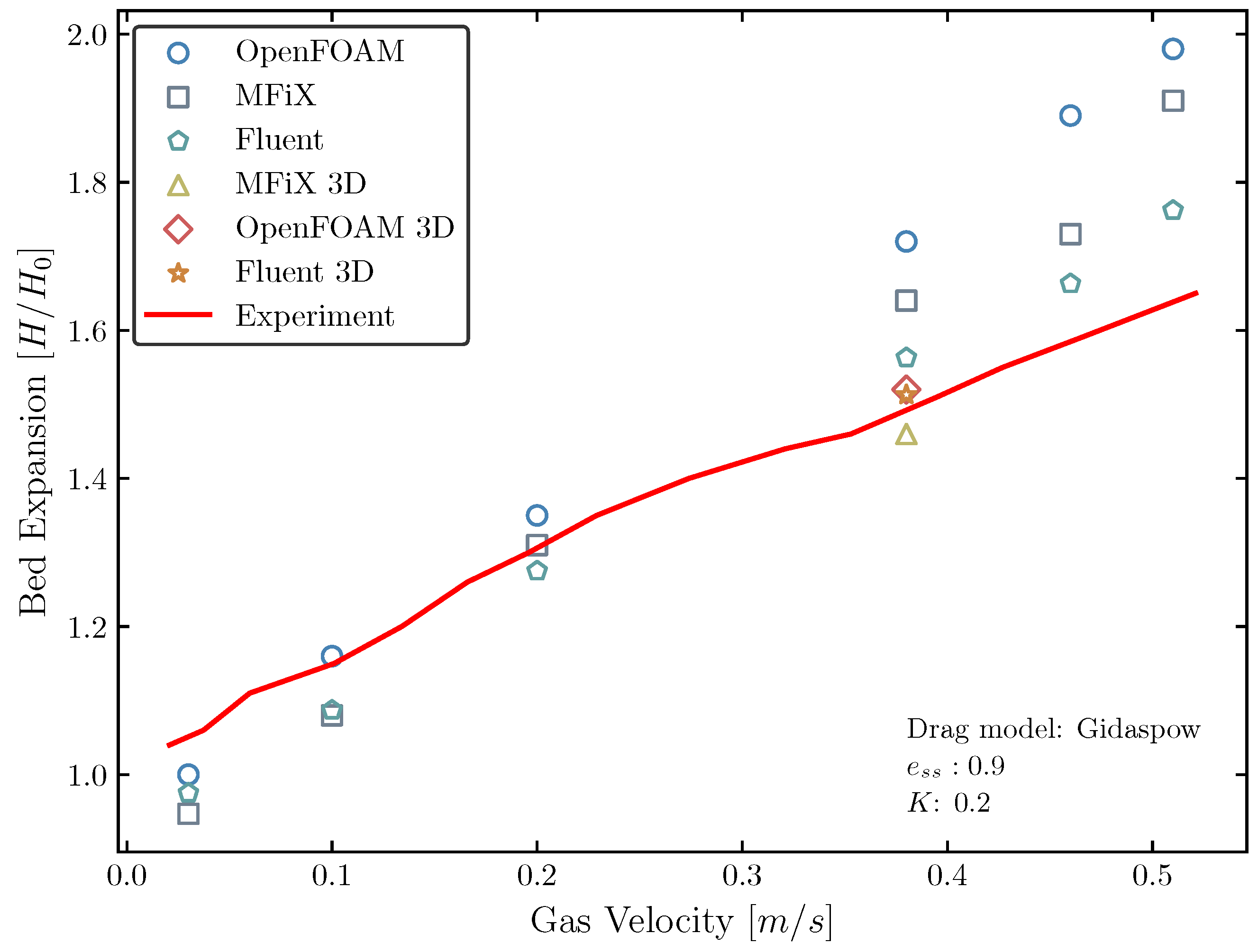

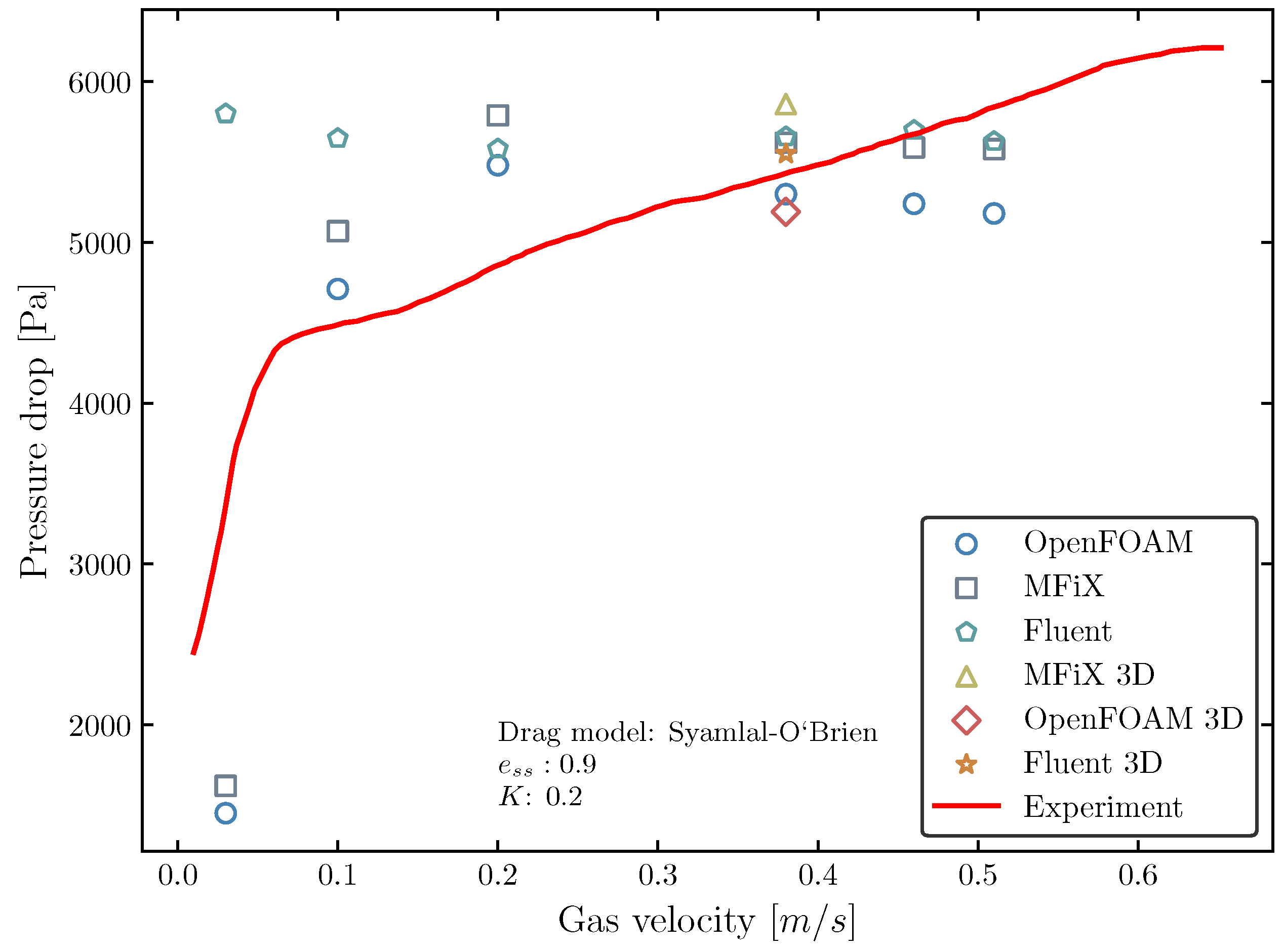

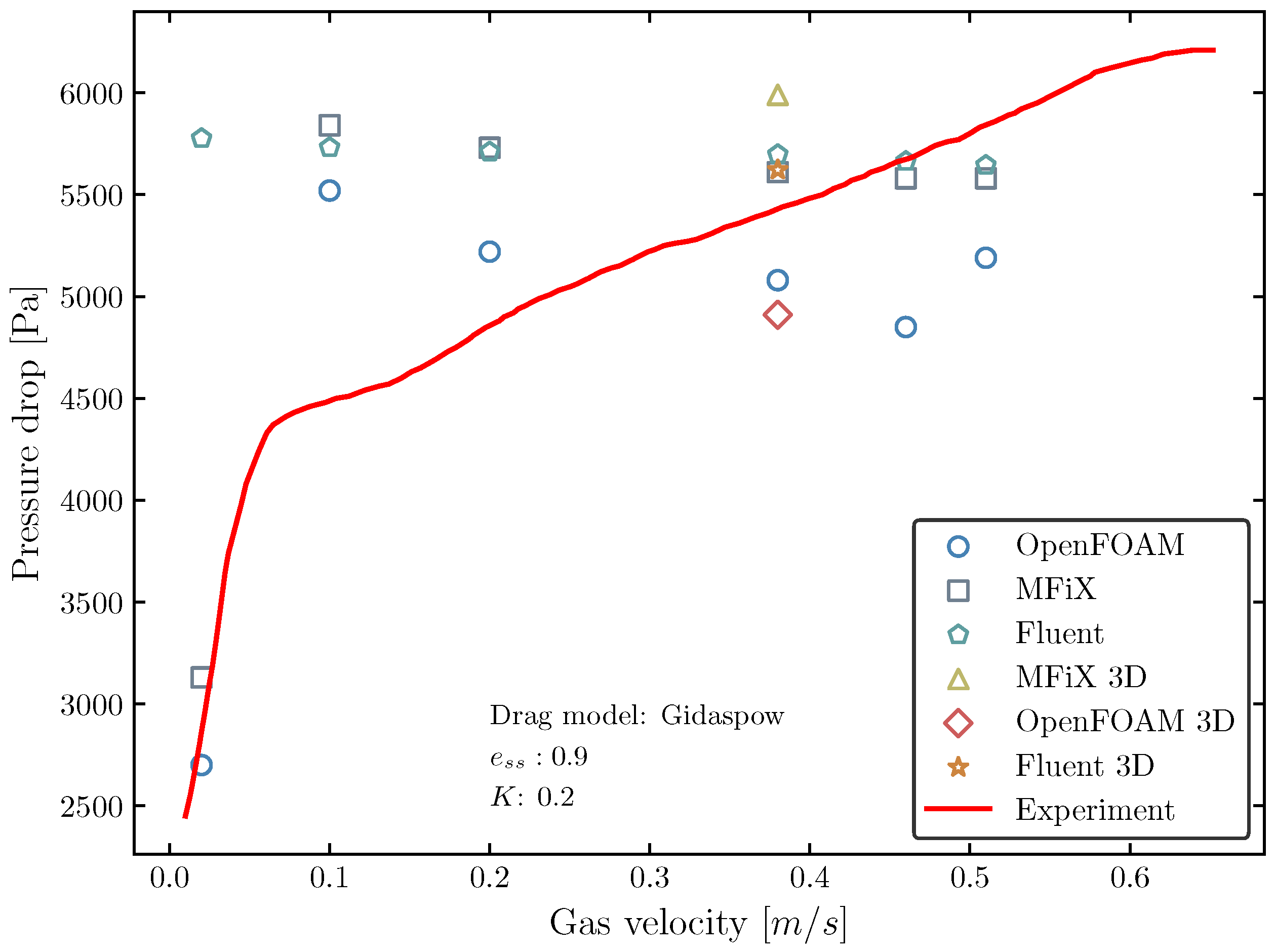

4.1. Bed Expansion Ratio and Pressure Drop

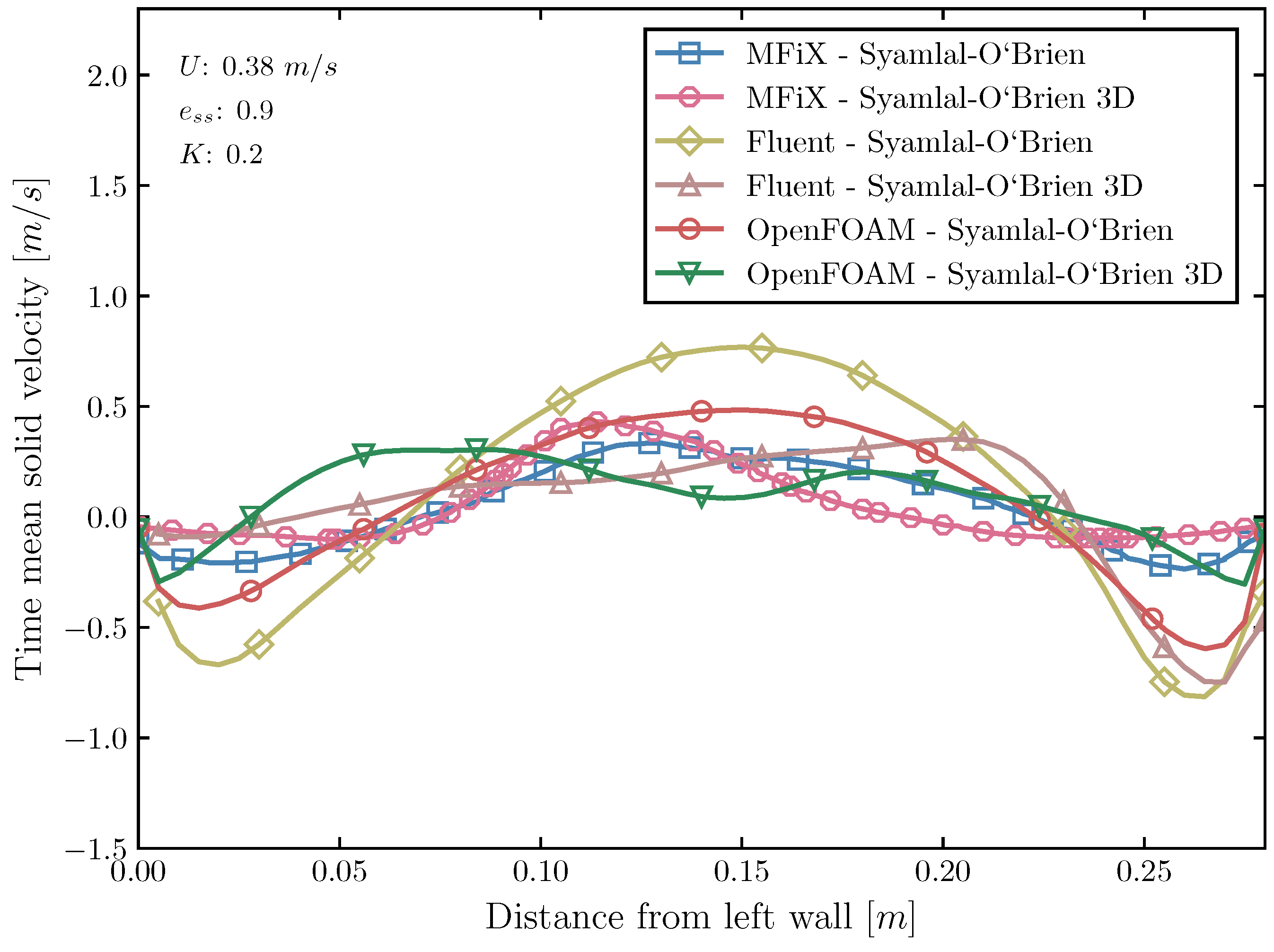

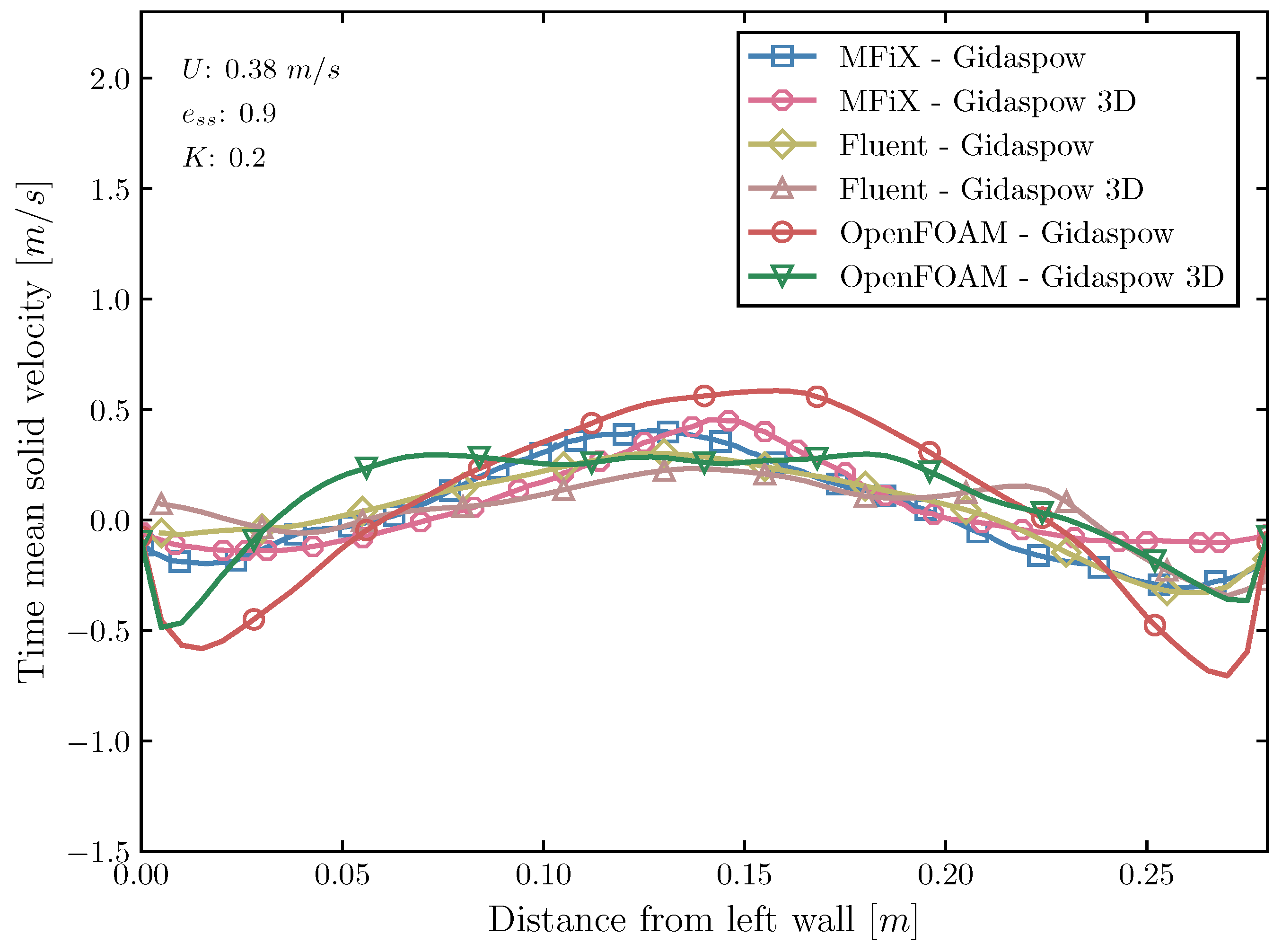

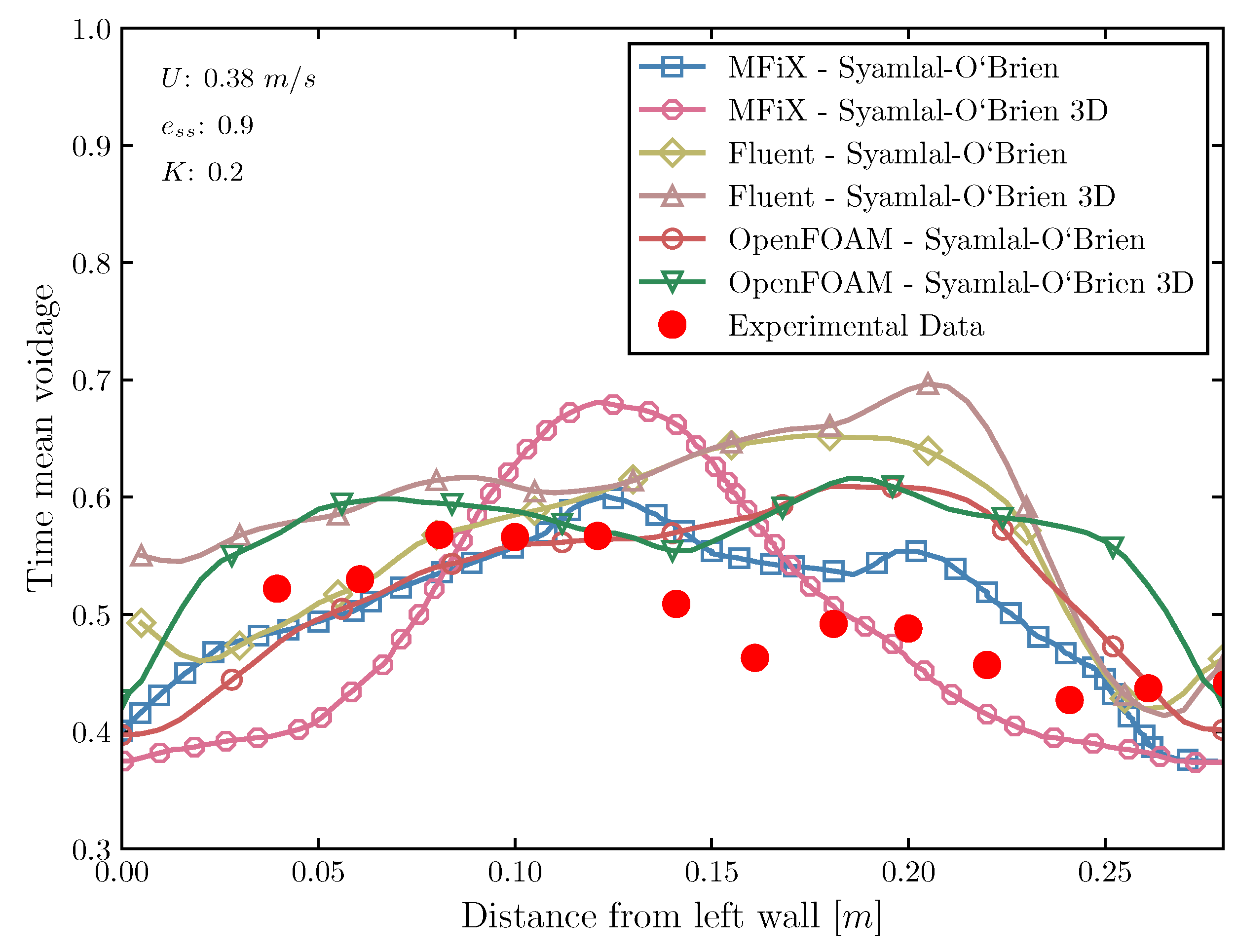

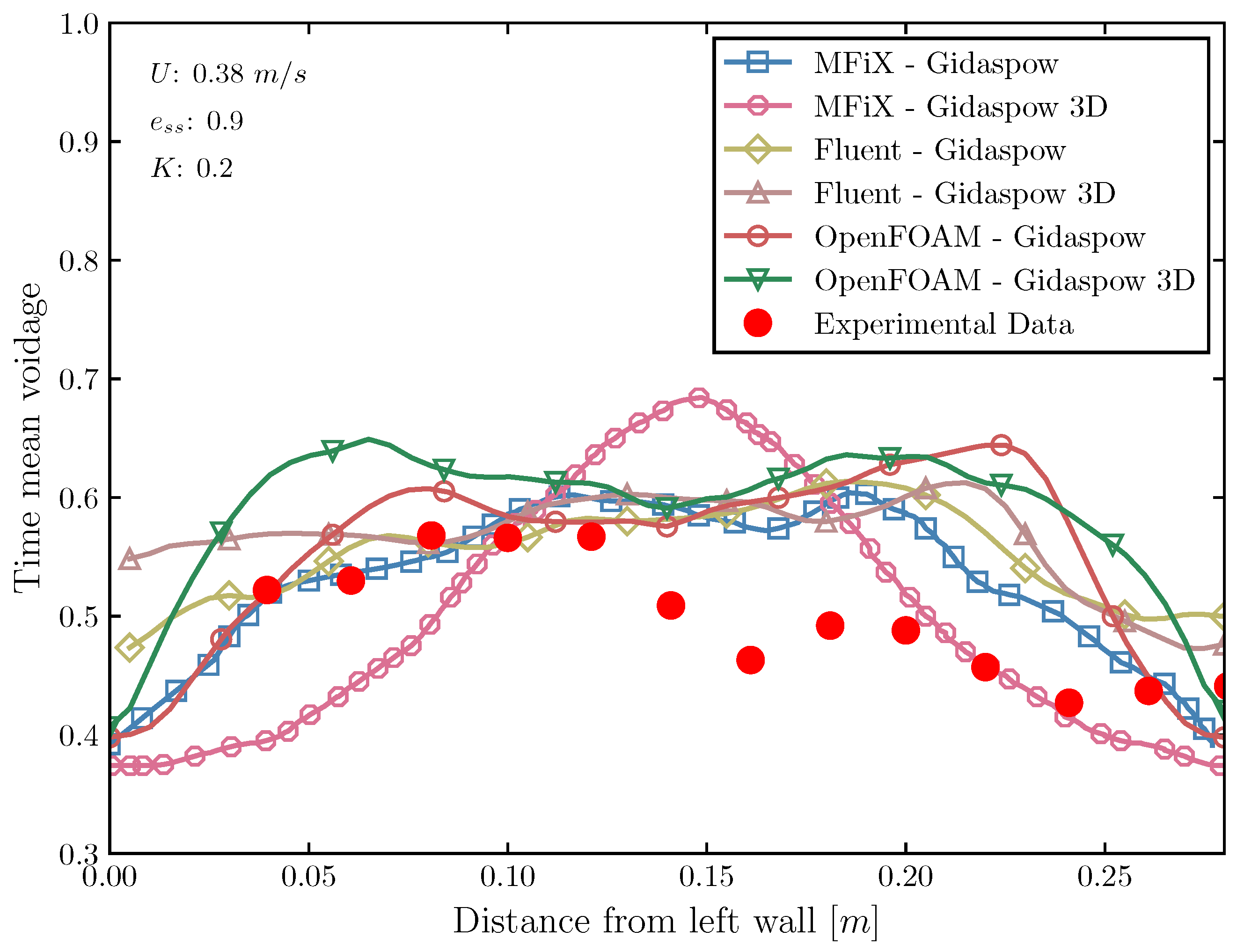

4.2. Solid Velocity and Voidage

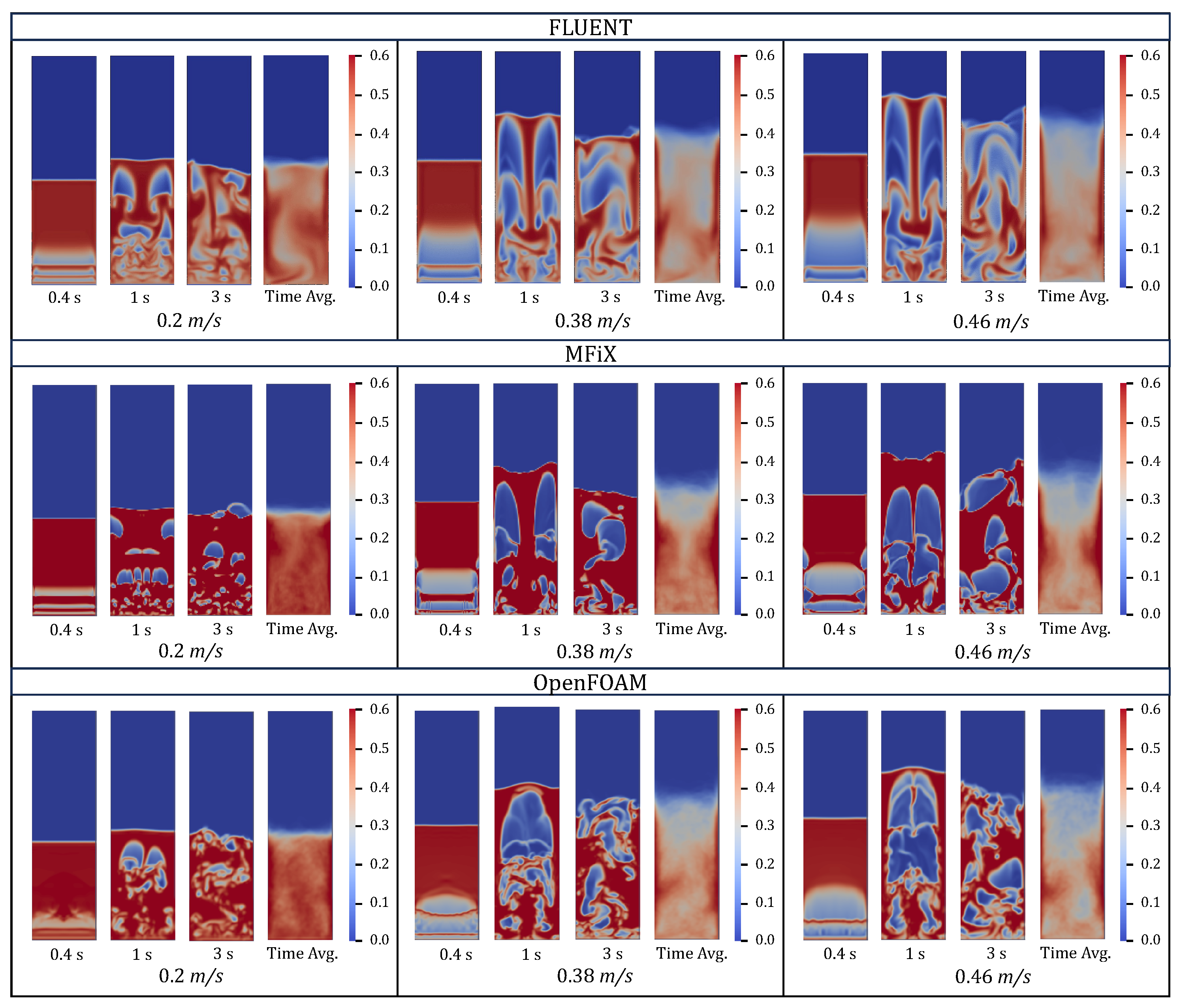

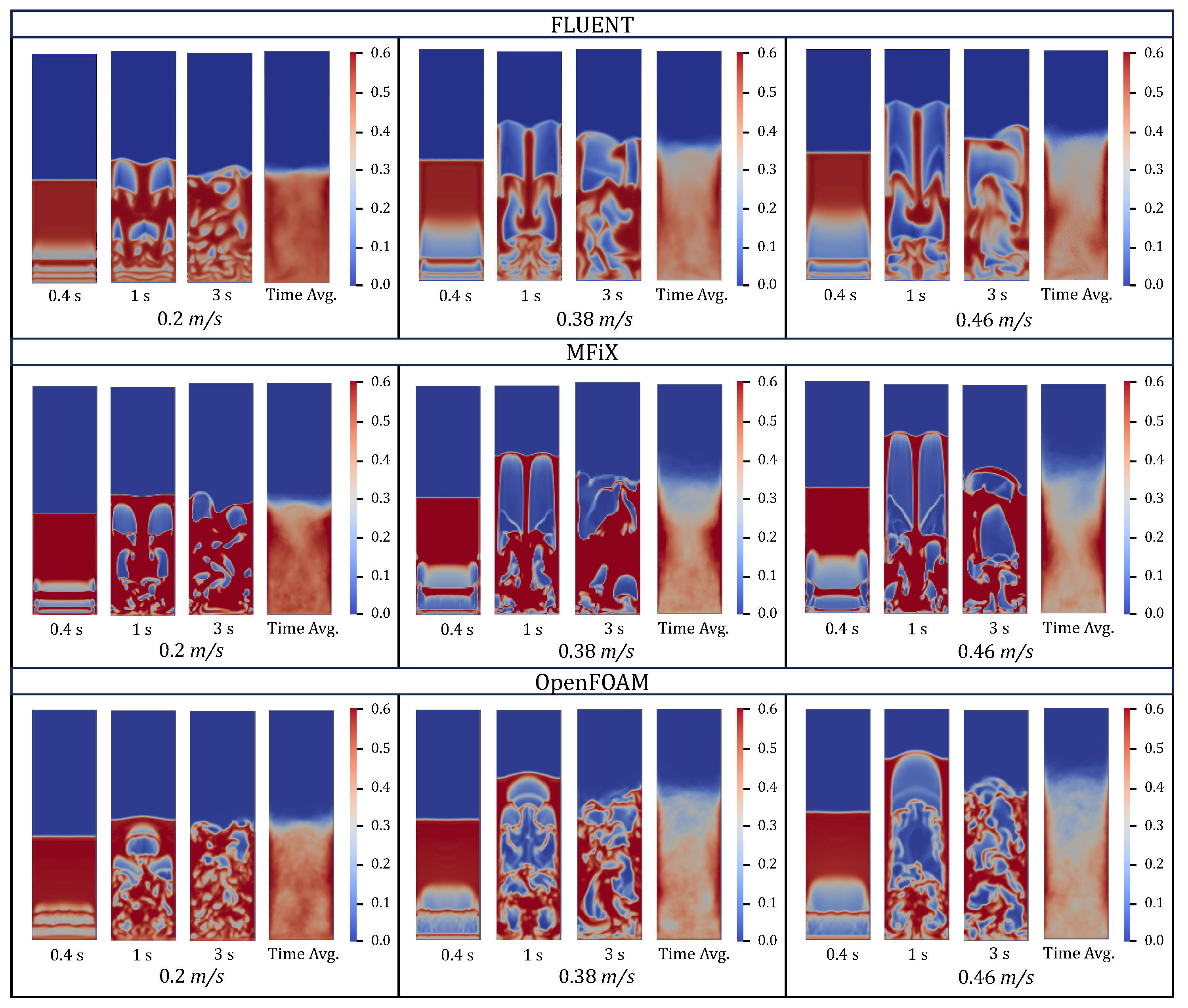

4.3. Solid Volume Fraction

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative study of different codes

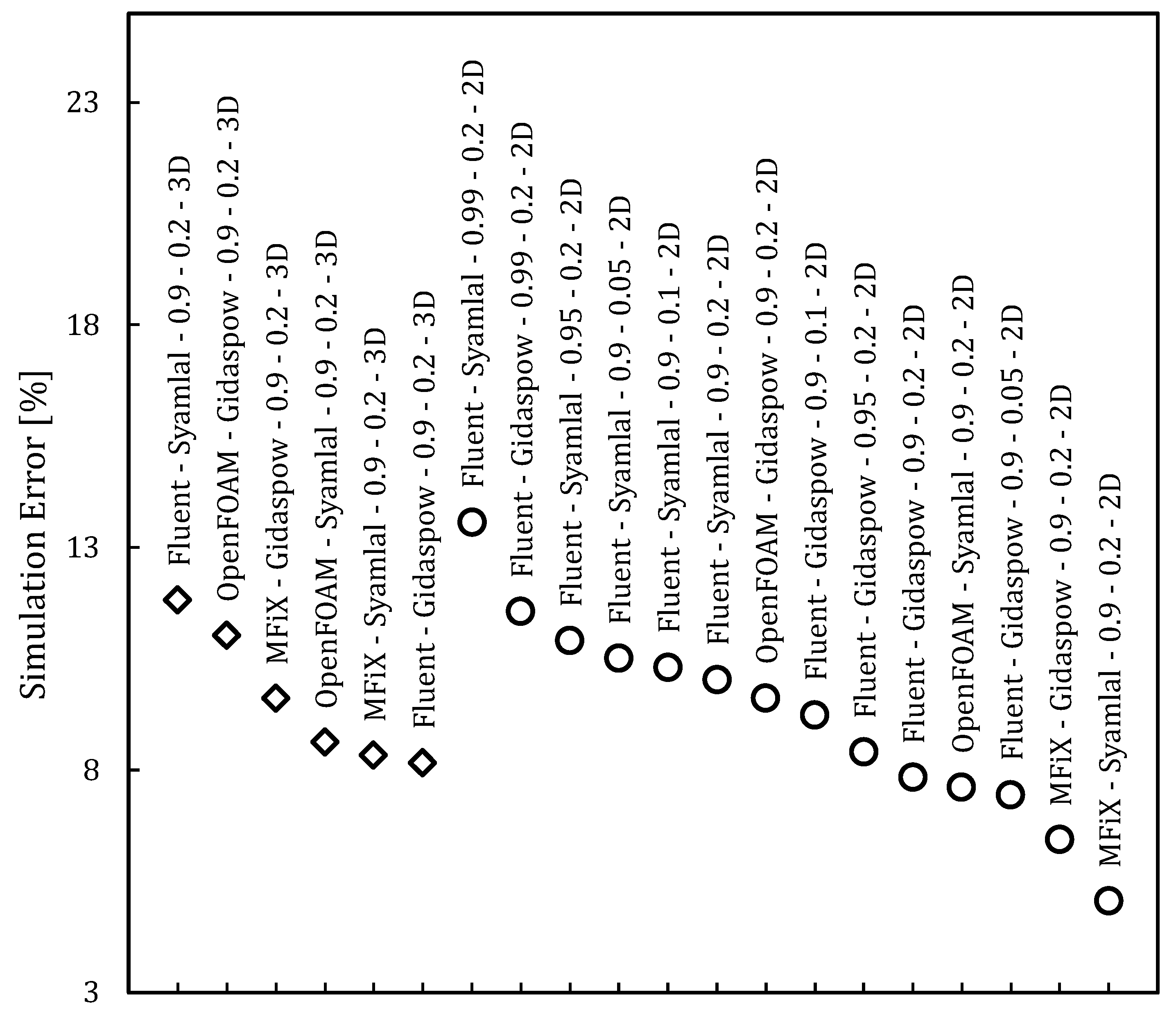

5.2. Simulation Error

5.3. The Effect of Restitution and Specularity Coefficient

6. Conclusions

- The assessment of ANSYS Fluent, MFiX, and OpenFOAM showed they could achieve reasonable agreement with experimental data across both drag models, offering insights into fluidized bed hydrodynamics. This comparison underscored specific strengths and weaknesses, revealing MFiX and ANSYS Fluent as more consistent and accurate in simulating fluidized bed dynamics, thereby emerging as preferable choices. OpenFOAM has shown maturity in predicting fluidized bed phenomena, yet it necessitates further validation and exploration to fully grasp the impact of various numerical settings and boundary conditions on its outcomes. This approach underscores the importance of fine-tuning and accurately assessing OpenFOAM’s capabilities for enhanced reliability in fluidized bed simulations.

- The analysis of the Syamlal-O’Brien and Gidaspow drag models revealed significant differences in their predictions, particularly in terms of bed expansion and pressure drop. The Syamlal-O’Brien model, when used with MFiX and OpenFOAM, typically resulted in lower simulation errors compared to the Gidaspow model. However, ANSYS Fluent showed a preference for the Gidaspow model, indicating that the choice of drag model can significantly influence simulation outcomes and should be carefully considered based on the CFD software being used.

- The transition from 2D to 3D simulations introduced notable variations in bed expansion and pressure drop predictions. While 3D simulations offer a more detailed representation of fluidized bed dynamics, they do not always guarantee improved alignment with experimental data. In some cases, 2D simulations provided better fits, suggesting that the dimensionality of the simulation should be chosen based on specific study requirements and the expected flow behavior.

- The study showed that while higher restitution coefficients led to increased bed expansion, indicating their significant impact on particle-particle collisions, variations in the specularity coefficient, which affects particle-wall interactions, had a subtler influence on bed dynamics, particularly noted in the Gidaspow drag model. A restitution coefficient of 0.9 was identified as optimal, balancing accuracy and computational efficiency, whereas the specularity coefficient’s effect, though present, was less pronounced within the examined range. This emphasizes the necessity of carefully selecting these coefficients to accurately model the complex behaviors in fluidized beds.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Volume fraction of the gas phase | |

| Volume fraction of the solid phase | |

| The maximum packing fraction of the solid phase | |

| Drag coefficient | |

| Diameter of the solid particles | |

| The rate of deformation tensor components for the solidphase | |

| A factor incorporating the restitution coefficient | |

| The restitution coefficient for solid-solid collisions | |

| Dissipation rate of fluctuating energy in the solidphase | |

| Collision dissipation of energy | |

| The radial distribution function at contact for solid-solidinteractions | |

| Gravitational acceleration vector | |

| The second invariant of the deformation tensor | |

| K | The specularity coefficient |

| Momentum exchange coefficient or interphase drag forcecoefficient | |

| Thermal conductivity of the solid phase for thefluctuating energy | |

| The thermal conductivity of the solid phase for granulartemperature | |

| Granular bulk viscosity | |

| Dynamic viscosity of the gas phase | |

| The viscosity coefficient of the solid phase | |

| Solid collision viscosity | |

| Solid frictional viscosity | |

| Solid kinetic viscosity | |

| ∇ | Nabla operator, representing vector differential operations |

| p | Pressure in the gas phase |

| Solid phase pressure | |

| Velocity vector of the gas phase | |

| Velocity vector of the solid phase | |

| Deviatoric stress tensor of the gas phase | |

| Solid phase shear stress tensor | |

| The identity tensor for the gas phase | |

| Gas phase shear stress tensor | |

| Deviatoric stress tensor of the solidphase | |

| Density of the gas phase | |

| Density of the solid phase | |

| ∅ | The angle of internal friction |

| t | Time |

| Fluctuating energy of the solid phase | |

| Relative velocity between phases | |

| Energy exchange rate between gas and solid phases | |

| Transfer of kinetic energy between gas and solid phases | |

| x | The spatial coordinate in the direction of the gradient |

| The transpose of the velocitygradient tensor of the gas phase | |

| Reynolds number for the solid phase, characterizing the flowregime |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Gas phase shear stress tensor |

| Solid phase shear stress tensor |

| Granular bulk viscosity |

| Solid shear viscosity |

| Solid collision viscosity [32] |

| Solid kinetic viscosity |

|

Syamlal-O`Brien [32]

|

| Solid frictional viscosity [27] |

|

|

| Solid phase pressure [26] |

| Radial distribution function [26,37] |

References

- Werther, J. Fluidized-Bed Reactors. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007; p. Article Number.

- Witt, P.M.; Hickman, D.A. Fluidized-bed reactor scale-up: Reaction kinetics required. AIChE Journal 2022, 68, e17803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunii, D.; Levenspiel, O. Fluidization Engineering; Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991.

- Alobaid, F.; Almohammed, N.; Massoudi Farid, M.; May, J.; Rößger, P.; Richter, A.; Epple, B. Progress in CFD Simulations of Fluidized Beds for Chemical and Energy Process Engineering. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2022, 91, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidaspow, D. Multiphase flow and fluidization: continuum and kinetic theory descriptions; Academic Press: Boston, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stroh, A.; Alobaid, F.; Hasenzahl, M.T.; Hilz, J.; Ströhle, J.; Epple, B. Comparison of three different CFD methods for dense fluidized beds and validation by a cold flow experiment. Particuology 2016, 29, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüner, C. Kopplung des Einzelpartikel-und des Zwei-Kontinua-Verfahrens für die Simulation von Gas-Feststoff-Strömungen; Shaker, 2004.

- Moin, P.; Mahesh, K. DIRECT NUMERICAL SIMULATION: A Tool in Turbulence Research. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 1998, 30, 539–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Inc.. ANSYS FLUENT. Commercial software, 2023.

- ANSYS Inc.. ANSYS CFX. Commercial software, 2023.

- The OpenFOAM Foundation. OpenFOAM. General Public License, 2023.

- National Energy Technology Laboratory. MFiX. General Public License, 2023.

- CPFD Software. BARRACUDA Virtual Reactor. Commercial software, 2023.

- CFDEM project. LIGGGHTS CFDEM coupling. General Public License, 2023.

- COMSOL Inc.. COMSOL Multiphysics. Commercial software, 2023.

- CD-adapco. STAR-CCM+. Commercial software, 2023.

- Altair Engineering. EDEM. Commercial software, 2023.

- Shi, H.; Komrakova, A.; Nikrityuk, P. Fluidized beds modeling: Validation of 2D and 3D simulations against experiments. Powder Technology 2019, 343, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, F.; Ellis, N.; Wong, C. Experimental and computational study of gas–solid fluidized bed hydrodynamics. Chemical Engineering Science 2005, 60, 6857–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamlal, M.; O’Brien, T.J. Simulation of granular layer inversion in liquid fluidized beds. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 1988, 14, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.T.; Taghipour, F.; Escudié, R.; Ellis, N.; Grace, J.R. CFD modelling of a liquid–solid fluidized bed. Chemical Engineering Science 2007, 62, 6334–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Grace, J.; Bi, X. Study of wall boundary condition in numerical simulations of bubbling fluidized beds. Powder Technology 2010, 203, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, N.; Schreiber, M.; Egbers, C.; Krautz, H.J. A comparative study of different CFD-codes for numerical simulation of gas–solid fluidized bed hydrodynamics. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2012, 39, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Daun, P.F. A Comparative Study of Different CFD-codes for Fluidized Beds. Master’s thesis, NTNU, 2023.

- ANSYS, Inc.. Ansys Fluent Theory Guide. ANSYS, Inc., release 2021 r1 ed., 2021.

- Lun, C.K.K.; Savage, S.B.; Jeffrey, D.J.; Chepurniy, N. Kinetic theories for granular flow: inelastic particles in Couette flow and slightly inelastic particles in a general flowfield. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1984, 140, 223–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.G. Instability in the evolution equations describing incompressible granular flow. Journal of Differential Equations 1987, 66, 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Gidaspow, D. A bubbling fluidization model using kinetic theory of granular flow. AIChE Journal 1990, 36, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Umemura, A.; Oshima, N. On the equations of fully fluidized granular materials. Zeitschrift für angewandte Mathematik und Physik ZAMP 1980, 31, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS, Inc.. Workshop: Modeling Uniform Fluidization in a 2D Fluidized Bed. ANSYS, Inc., release 2023 r1 ed., 2023.

- Johnson, P.C.; Jackson, R. Frictional–collisional constitutive relations for granular materials, with application to plane shearing. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1987, 176, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamlal, M.; Rogers, W.; O`Brien, T. MFIX documentation theory guide. Technical report, National Energy Technology Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, 1993.

- El Ajouri, O.; Lahlaouti, M.L.; Kharbouch, B. CFD-simulation of gas-solid flow in bubbling fluidized bed reactor. E3S Web of Conferences 2022, 336, 00059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboudaoud, S.; Touzani, S.; Abderafi, S.; Cheddadi, A. CFD Simulation of Air-Glass Beads Fluidized Bed Hydrodynamics. Journal of Applied Fluid Mechanics 2023, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hinrichsen, O. CFD modeling of bubbling fluidized beds using OpenFOAM®: Model validation and comparison of TVD differencing schemes. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2014, 69, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gidaspow, D.; Bezburuah, R.; Ding, J. Hydrodynamics of Circulating Fluidized Beds: Kinetic Theory Approach, 1991.

- Carnahan, N.F.; Starling, K.E. Equation of State for Nonattracting Rigid Spheres. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1969, 51, 635–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Value | Remark |

| Bed width | 0.28 m | Fixed value |

| Bed height | 1 m | Fixed value |

| Static bed height | 0.4 m | Fixed value |

| Grid interval spacing | 0.005 m | Specified |

| Particle density | 2500 kg/m | Glass beads |

| Gas density | 1.225 kg/m | Air |

| Gas kinematic viscosity | m/s | Fixed value |

| Mean particle diameter | 275 m | Uniformly distributed |

| Initial solids packing | 0.6 | Fixed value |

| Maximum solids packing | 0.63 | Fixed value |

| Superficial gas velocity | 0.03 - 0.51 m/s | Parametized |

| Restitution coefficient | 0.9; 0.95; 0.99 | Parametized |

| Specularity coefficient | 0.05; 0.1; 0.2 | Parametized |

| Min. fluidization velocity | 0.065 m/s | Experiment |

| Viscous model | Laminar | Specified |

| Drag model | Syamlal-O’Brien; Gidaspow | Parametized [5,20] |

| Granular bulk viscosity | Lun et al. | [25,26] |

| Kinetic viscosity | Syamlal-O’Brien; Gidaspow | Parametized |

| Granular temperature | Algebraic; PDE; PDE | ANSYS Fluent; OpenFOAM; MFiX |

| Frictional viscosity | Schaeffer | [25,27] |

| Frictional pressure | Based-ktgf | [25] |

| Radial distribution | Lun et al | [25,26] |

| Inlet boundary condition | Velocity | Superficial gas velocity |

| Outlet boundary condition | Outflow | Fully developed flow |

| Time steps | 0.001 s | Specified |

| Time averaged range | 3 - 12 s | Specified |

| Transient formulation | First order | Specified |

| Solution algorithm | SIMPLE; PIMPLE; MFiX algorithm | ANSYS Fluent; OpenFOAM; MFiX |

| Case | Software | u, m/s | Drag force | K | Geomery | , Pa | ||

| 1 | Fluent | 0.03 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 0.975 | 5800* |

| 2 | Fluent | 0.1 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.162 | 5647 |

| 3 | Fluent | 0.2 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.388 | 5581 |

| 4 | Fluent | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.700 | 5657 |

| 5 | Fluent | 0.46 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.875 | 5697 |

| 6 | Fluent | 0.51 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.963 | 5628 |

| 7 | Fluent | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.95 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.762 | 5613 |

| 8 | Fluent | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.99 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.813 | 5577 |

| 9 | Fluent | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.05 | 2D | 1.700 | 5633 |

| 10 | Fluent | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.1 | 2D | 1.700 | 5514 |

| 11 | Fluent | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3D | 1.513 | 5551 |

| 12 | Fluent | 0.03 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 0.975 | 5776* |

| 13 | Fluent | 0.1 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.087 | 5731 |

| 14 | Fluent | 0.2 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.275 | 5710 |

| 15 | Fluent | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.563 | 5697 |

| 16 | Fluent | 0.46 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.663 | 5663 |

| 17 | Fluent | 0.51 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.762 | 5644 |

| 18 | Fluent | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.95 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.550 | 5608 |

| 19 | Fluent | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.99 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.625 | 5661 |

| 20 | Fluent | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.05 | 2D | 1.525 | 5554 |

| 21 | Fluent | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.1 | 2D | 1.539 | 5604 |

| 22 | Fluent | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3D | 1.625 | 5622 |

| 23 | OpenFOAM | 0.03 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.000 | 1450 |

| 24 | OpenFOAM | 0.1 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.020 | 4710 |

| 25 | OpenFOAM | 0.2 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.260 | 5480 |

| 26 | OpenFOAM | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.630 | 5300 |

| 27 | OpenFOAM | 0.46 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.800 | 5240 |

| 28 | OpenFOAM | 0.51 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.860 | 5180 |

| 29 | OpenFOAM | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3D | 1.520 | 5190 |

| 30 | OpenFOAM | 0.03 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.000 | 2700 |

| 31 | OpenFOAM | 0.1 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.160 | 5520 |

| 32 | OpenFOAM | 0.2 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.350 | 5220 |

| 33 | OpenFOAM | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.720 | 5080 |

| 34 | OpenFOAM | 0.46 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.890 | 4850 |

| 35 | OpenFOAM | 0.51 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.980 | 5190 |

| 36 | OpenFOAM | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3D | 1.520 | 4910 |

| 37 | MFiX | 0.03 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 0.951 | 1620 |

| 38 | MFiX | 0.1 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.040 | 5070 |

| 39 | MFiX | 0.2 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.200 | 5790 |

| 40 | MFiX | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.520 | 5620 |

| 41 | MFiX | 0.46 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.700 | 5590 |

| 42 | MFiX | 0.51 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.790 | 5580 |

| 43 | MFiX | 0.38 | Syamlal-O’Brien | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3D | 1.460 | 5860 |

| 44 | MFiX | 0.03 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 0.947 | 3130 |

| 45 | MFiX | 0.1 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.080 | 5840 |

| 46 | MFiX | 0.2 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.310 | 5730 |

| 47 | MFiX | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.640 | 5610 |

| 48 | MFiX | 0.46 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.730 | 5580 |

| 49 | MFiX | 0.51 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 2D | 1.910 | 5580 |

| 50 | MFiX | 0.38 | Gidaspow | 0.9 | 0.2 | 3D | 1.460 | 5990 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).