1. Introduction

The main geometrical methods in the sciences go back to ancient times, and are based on lines and circles. The ubiquitous contemporary use of Fourier methods in physics and engineering, is mathematically equivalent to the methods used by Ptolomy.

Euclidean geometry has mainly evolved into Riemannian geometry, with local Euclidean geometry in the tangent spaces [

1]. Another extension is in Minkowski-Finsler geometry, also referred to as Riemannian geometry without the quadratic restriction [

2]. Just as Euclidean geometry in two dimensions is based on the circle as the basic figure for the isotropic determination of distances, Lamé curves (also referred to as supercircles and superellipses) form the basis of the simplest definitive Minkowski-Finsler geometries. Generalizing superellipses to any symmetry (Gielis transformations) extend the methods for the natural sciences to describe various natural anisotropies for different symmetries

s (

, etc. or any real value), as observed in starfish or diatoms [

3]. Applying Gielis transformations to the "most “natural” curves and surfaces of Euclidean geometry, e.g. circles under the closed curves and logarithmic spirals under the non-closed curves in two dimensions, one obtains many shapes observed in nature in biology, crystallography, physics, and other fields [

3,

4].

In the past decade these curves and transformations have been used successfully to model of a wide variety of natural shapes, from plant leaves and tree rings to starfish and avian eggs [

5]. Further applications of Finsler geometry in the natural sciences involving superellipses or Gielis curves, are found in forest ecology [

6,

7], seismic ray paths in anisotropic media [

8], and the spreading of wildfires [

9]. This has inspired various researchers to study various geometrical transformations, including inversions [

10], whereby the inversion occurs with Lamé-Gielis curves as inversion circles.

Inversions are area-preserving transformations, whereby the area of a rectangle formed by the two distances from the center is equal to the area of the square on the radius of the circle. This is very similar to the parabola, a machine for transforming rectangles into squares with same area. In Euclidean geometry parabola, ellipse and hyperbola are related directly to the application of areas in Euclid’s Book II. Since the basics shapes of our simplest Minkowski-Finsler geometries are a one-step generalization of the classic conic sections, it is of great interest to return to the methods used in ancient times. While in Euclidean geometry the image of a point under circular inversion can be found by a synthetic method, in another type of geometry that “stands next to and is a relative of Euclidean geometry (which is called Minkowki geometry)” synthetic methods for circular inversion are not well known.

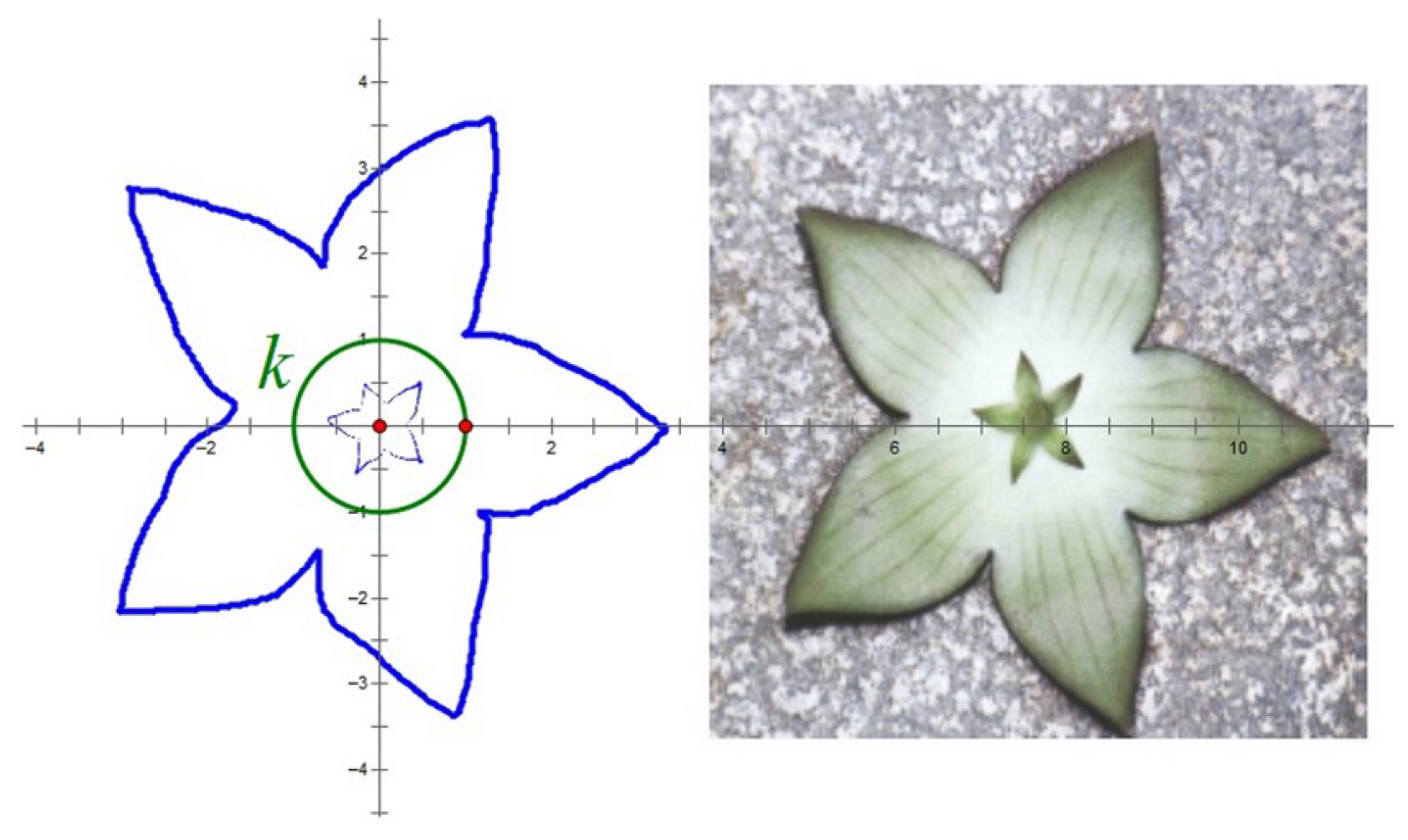

Figure 1.

Huernia flowers and how the outer edges of the corolla (blue) are obtained by inversion of the sepals (light blue) over the green circle

k (see [

10] for details).

Figure 1.

Huernia flowers and how the outer edges of the corolla (blue) are obtained by inversion of the sepals (light blue) over the green circle

k (see [

10] for details).

The concept of Euclidean distance can be generalized to any linear space by the introduction of a norm. In this sense, the geometry that reveals with the help of norms in finite-dimensional Banach spaces is called Minkowski geometry (we refer the reader to [

11,

12,

13] for a wider treatment). This is often confused with spacetime geometry, also called Minkowski geometry. Hermann Minkowski (1864–1909) was a pioneer in both geometries, and the general structure of Minkowski space was introduced by Minkowski while working on some problems in number theory [

14]. However, considering that Riemann mentioned

norm in [

15], it can be said that the first step towards Minkowski Geometry was taken by Riemann. A norm on a vector space

V is a function

for which the following hold for any

V and

:

i. (positive definite, ),

ii. (positive homogeneity ),

iii. (triangle inequality ).

A normed space is a set V with a norm defined on V. The most important thing that explains the relationship between normed spaces and metric spaces is the following proposition:

Lemma 1.

A normed linear space is a metric space with the distance

Proof. The metric properties (nonnegative and symmetry) of

are quite obvious from the norm axioms. From the triangular inequality property of the norm

for any

. □

Also, the most well-known examples of normed spaces are normed space and normed normed space, whose definitions are given below.

Let

be a vector in the

dimensional real vector space

. The

norm defined as

Also, the pair

is called

normed or

normed space. The

norm is defined by

where

,

and

. The pair

is called

normed space (we refer the reader to [

16,

17,

18] for a wider treatment).

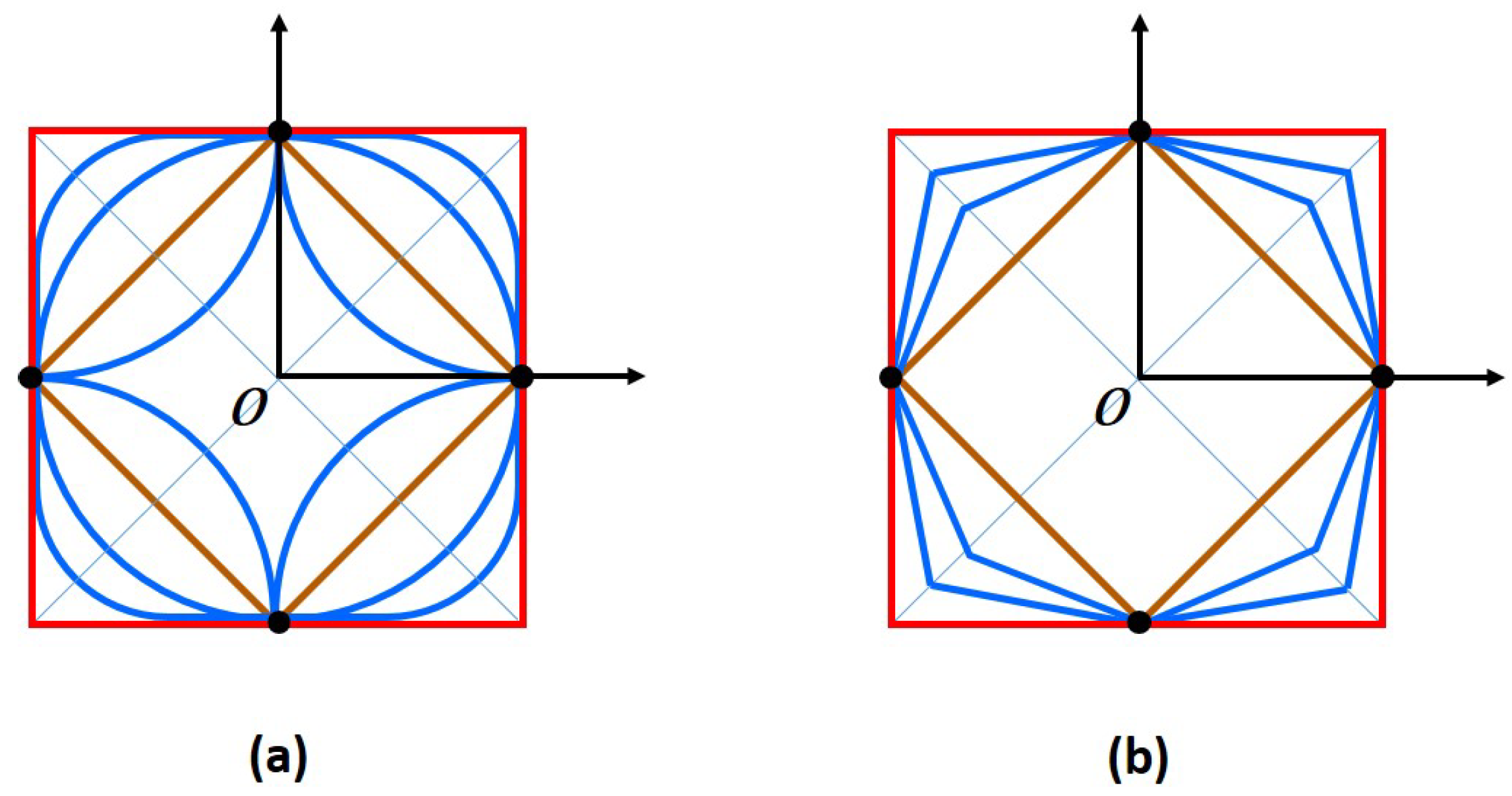

Figure 1 shows that the unit balls are convex with non-empty interior and centrally symmetric sets according to the

and

norms. However, norms that have unit balls that are centrically symmetric but not mirror symmetric can be defined as follows (see

Figure 3):

Figure 2.

(a) Unit circles for varying norms, (b) Unit circles for varying norms.

Figure 2.

(a) Unit circles for varying norms, (b) Unit circles for varying norms.

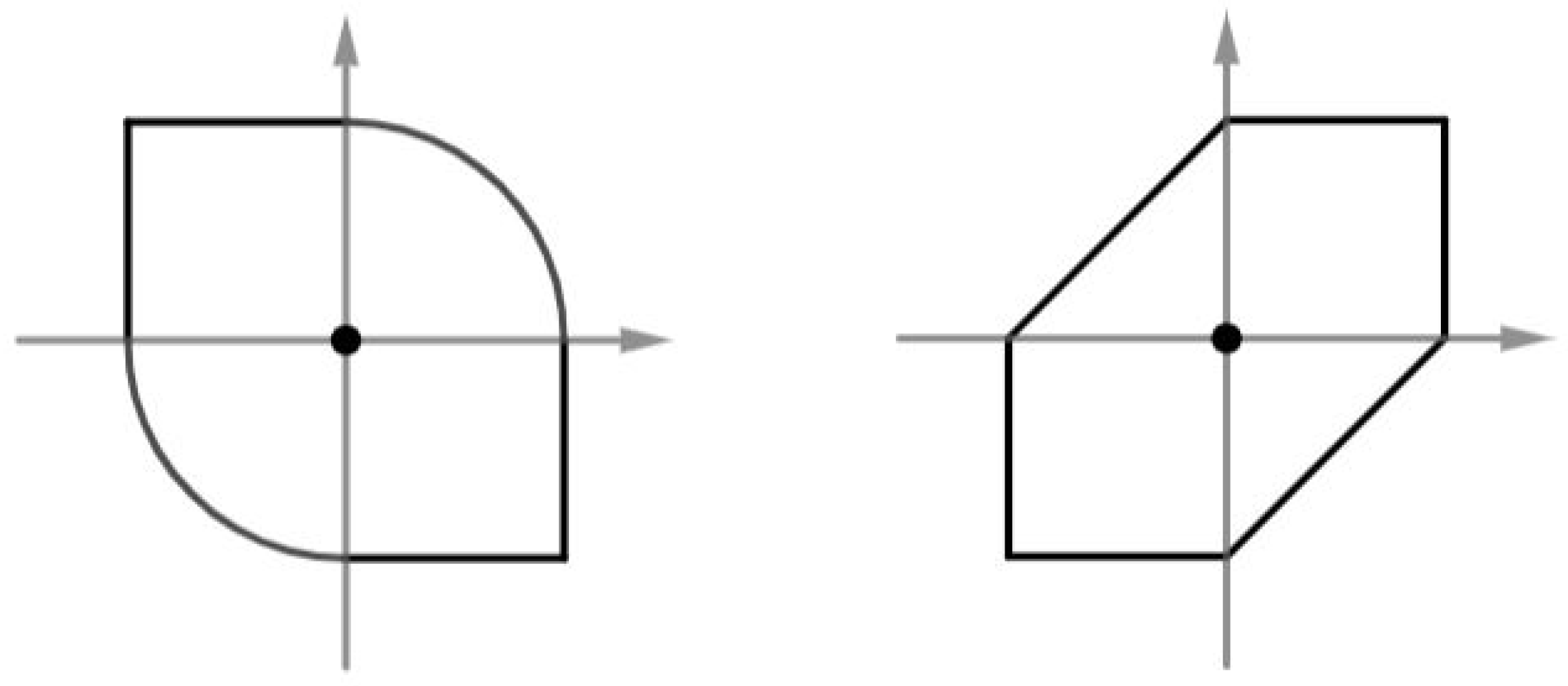

Figure 3.

Unit circles in terms of the norms , respectively.

Figure 3.

Unit circles in terms of the norms , respectively.

As a result, it is clear from the definition of a norm that the unit ball has the following characteristics;

i) the unit ball is a closed and bounded set,

ii) the unit ball is centrally symmetric,

iii) the unit ball is convex.

Conversely, if

B is a set satisfying the properties

i, ii and

iii, then the function

is a norm on

for which

B is the unit ball.

It should be noted here that the convex distance function

induced by the convex set

D that has a nonempty interior and is not necessarily centrally symmetric is defined via

by

Although it is obvious that the convex distance function

has the properties

and

(

homogeneity) such that for any vectors

and

, the distance function

does not have to satisfy the symmetry property, which is one of the axioms of metric space. The distance function

satisfies the symmetric axiom if and only if

D is centrally symmetric. Thus,

is a norm and the distance function

is a metric on

. The pair

is called Minkowski geometry. Thanks to translation invariance and homogeneity, all points in any Minkowski geometry

have the same status, and all geometric objects are centered at the origin. Furthermore, open balls

are rescaled, translated versions of the unit ball

. As a result, the fact that the norms can be interpreted and understood entirely with the help of the shapes of the unit balls shows that the structure of Minkowski geometry can be completely determined by the unit ball, which are centrally symmetrical convex bodies.

The idea of examining the invariance of concepts including the concept of distance in Euclidean geometry in Minkowski geometry when the Euclidean norm is replaced by an arbitrary Minkowski norm is quite interesting. However, this trade-off can cause even very elementary and simple questions to be very difficult to answer, and an answer may not even be found. One example is, while in Euclidean geometry the image of a point under circular inversion can be found by a synthetic method due to the unit ball having perfect symmetry, can a synthetic method be constructed for Minkowski geometry whose unit ball is centrally symmetric but not perfect?

The main motivation of this study is to seek an answer to the very difficult question above. In order to answer this question, we will take a short journey to circular inversion in Minkowski geometry with the norm and in the next section.

2. Visit to the Circular Inversion in Minkowski Geometries and

Let’s consider the circle

. The inverse of an arbitrary point

P, different from the center of symmetry of the circle

O, with respect to the circle

C is the point

, such that

A circular inversion is sometimes referred to as a “reflection” relative to the circle. Obviously, if the inverse of point

P is point

, then the inverse of point

is point

P. Moreover, from Equation (2.1), it is clear that, except for the center of the inversion circle

O, circular inversion will map the points inside the inversion circle to the points outside the circle, or the points inside the circle to the points outside. The points on the inversion circle

C remain fixed under circular inversion. It should be noted that the center of the inversion circle

O cannot be mapped to any point of the plane. However, points close to

O are mapped to points far from

O, and points far from

O are mapped to points close to

O. Thus, it would be meaningful to make a mapping between point

at infinity and point

O under circular inversion. Inversion mapping, which is one of the most important representatives of conformal functions that generally maps circles or lines into (same or different) circles or lines and preserves the angles between intersecting curves, is defined as follows (see [

19] for more details):

Definition 1.

Let the circle be given. The inversion according the circle C is the mapping defined as follows; for all

such that is the point lying on the ray and , also and .

According to the above definition, in the plane equipped with the Manhattan norm

(is given by

) and the Euclidean norm

(is given by

), circular inversion is formally defined as (see [

20,

21,

22,

23] for more details);

for

and

.

According to this definition, it is clear that finding the inverse of a point analytically will lead to tedious operations. In this sense, the following simple synthetic method, which is well known in the literature, has been proposed to find the inverse of a point according to the Euclidean norm .

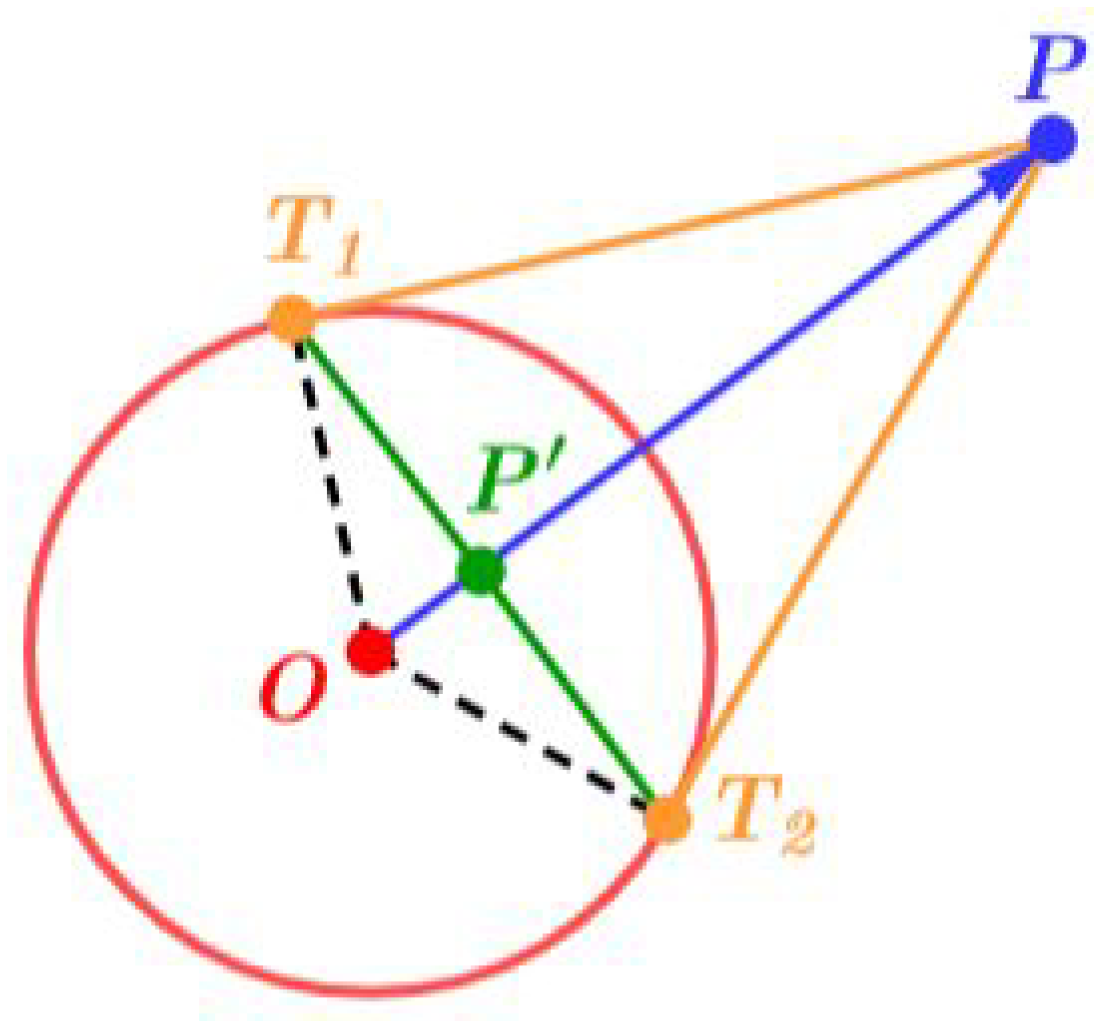

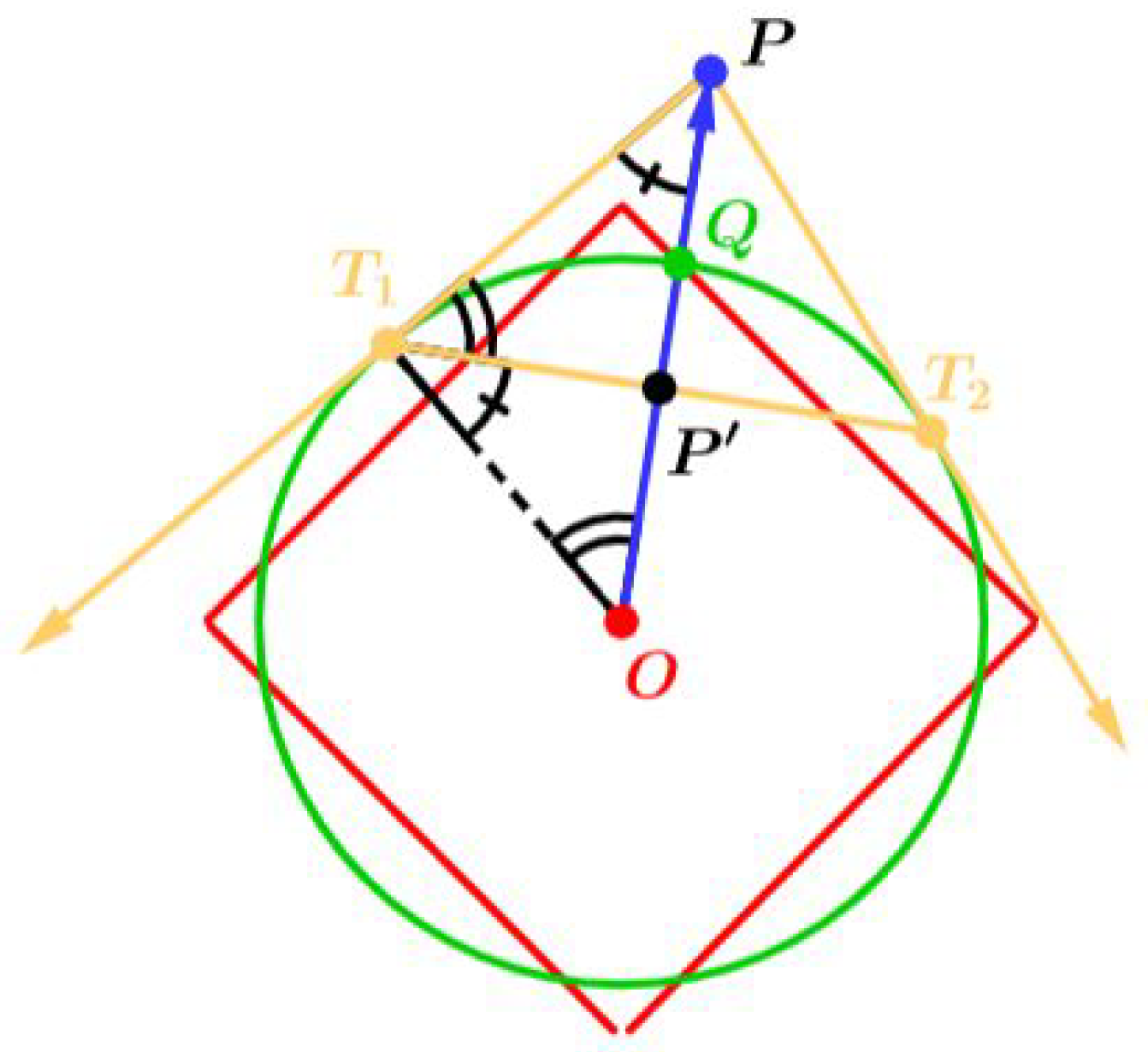

Simple Construction: To construct the inverseof a pointPoutside the circle(see

Figure 4):

Step 1 : Draw the tangent lines from point P to inversion circle C,

Step 2 :Label the point where the tangent lines touch circle C as and ,

Step 3 :The point where line segment intersects the ray is the inverse of P.

The inverse of a point in Euclidean geometry can be easily found by the above well-known synthetic method since the unit ball has perfect symmetry. However, a synthetic method for Minkowski geometry, in which the unit ball is centrally symmetric but does not necessarily have perfect symmetry, is not available in the literature. In order to give a synthetic method for circular inversion in Minkowski geometry, we will consider and normed spaces, which are the most classical examples of Minkowski geometry. If we manage to give a synthetic method for the Manhattan (or taxicab) geometry, which is corresponding to the special case of or in and normed spaces, we can attempt to generalize this method to Minkowski geometry. Thus, this method we will give for Manhattan geometry in the next section will illuminate our way in this difficult journey regarding the synthetic method we want to give in Minkowski geometry.