Submitted:

18 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Regulatory Approval

2.2. Database Sources

- The total population, age, income, race, and education data were obtained from census data of the United States Burro for Pennsylvania.

- Diabetes, Body Mass Index (BMI), obesity, BMI overweight, atrazine, no physical activities, and fruit and vegetable consumption datasets were obtained from the Enterprise Data Dissemination Informatics Exchange, Pennsylvania BRFSS: Diabetes - Ever told they have diabetes, Overweight, and Obesity - Obese (BMI GE 30); Overweight and Obesity - Overweight (BMI GE 25); Drinking Water Quality: Annual Distribution of Water Systems and Number of People Served by Atrazine Concentration, Physical Activity - No–no leisure time physical activity in the past month, and Fruits and Vegetables: Consume at least five servings of fruits and/or vegetables every day.

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Target Population

2.6. Data Collection and Data Processing

2.6.1. Handling Missing Values

2.7. Variable Selection

- County: Geographic location.

- Total Population: Total population count.

- Fruits and Vegetables: Frequency of consumption of at least five servings of fruits and vegetables.

- Physical activity: Level of physical activity.

- Atrazine Counts: Frequency of Individuals exposed to 1ug/L, an environmental contaminant.

- No Physical Activity: Frequency of no physical activity.

- BMI Obese: Percentage of population categorized as obese.

- BMI Overweight: Percentage of population categorized as overweight.

- Age: Median age of the population.

- White alone, Black or African American alone, American Indian and Alaska Native alone, Asian alone, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone: Frequency of population by racial/ethnic groups.

- Median Income: Median household income.

- Less than high school, Highschool graduates, Some college or associate, Bachelor degree: Frequency of population by education level.

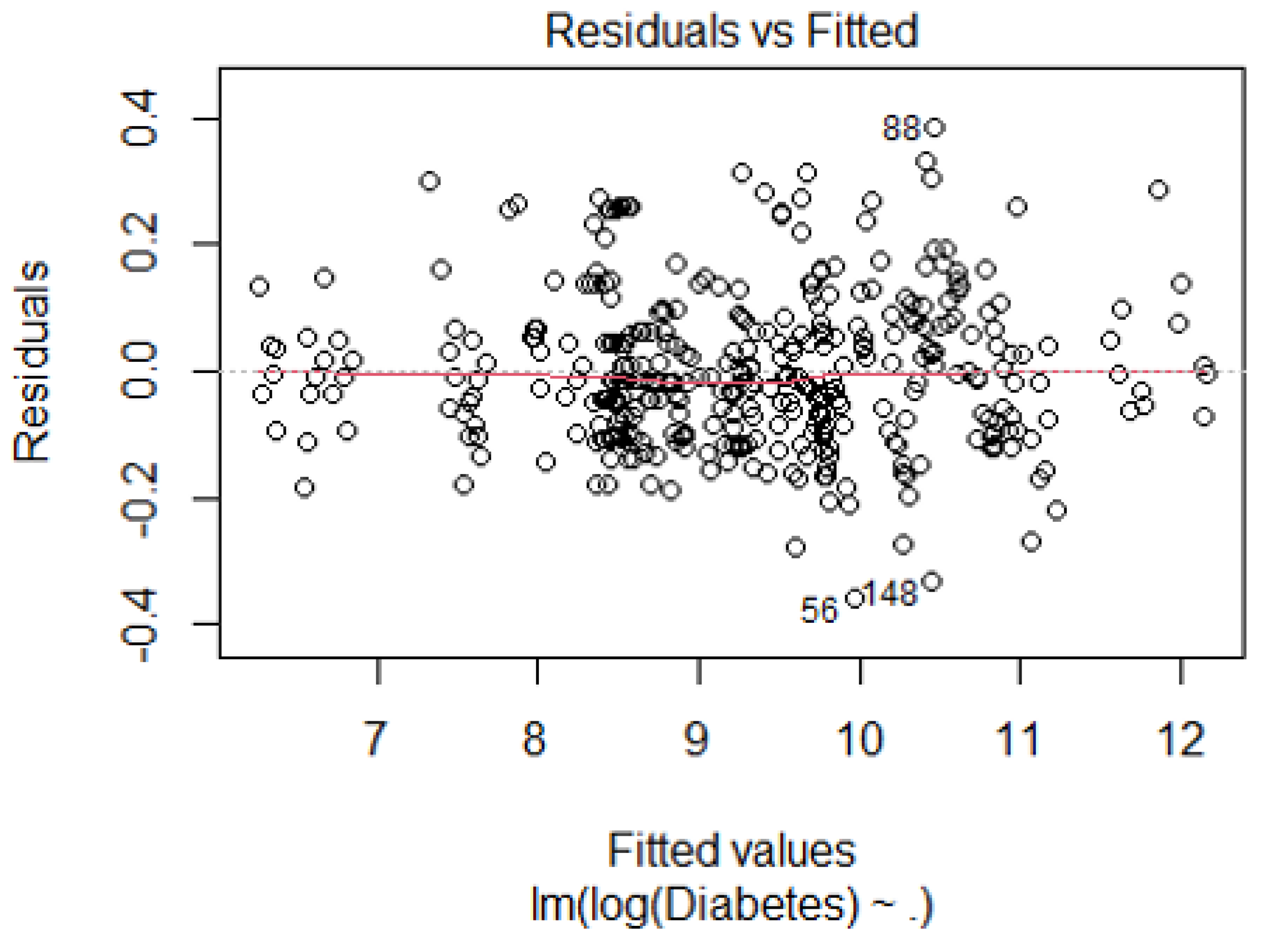

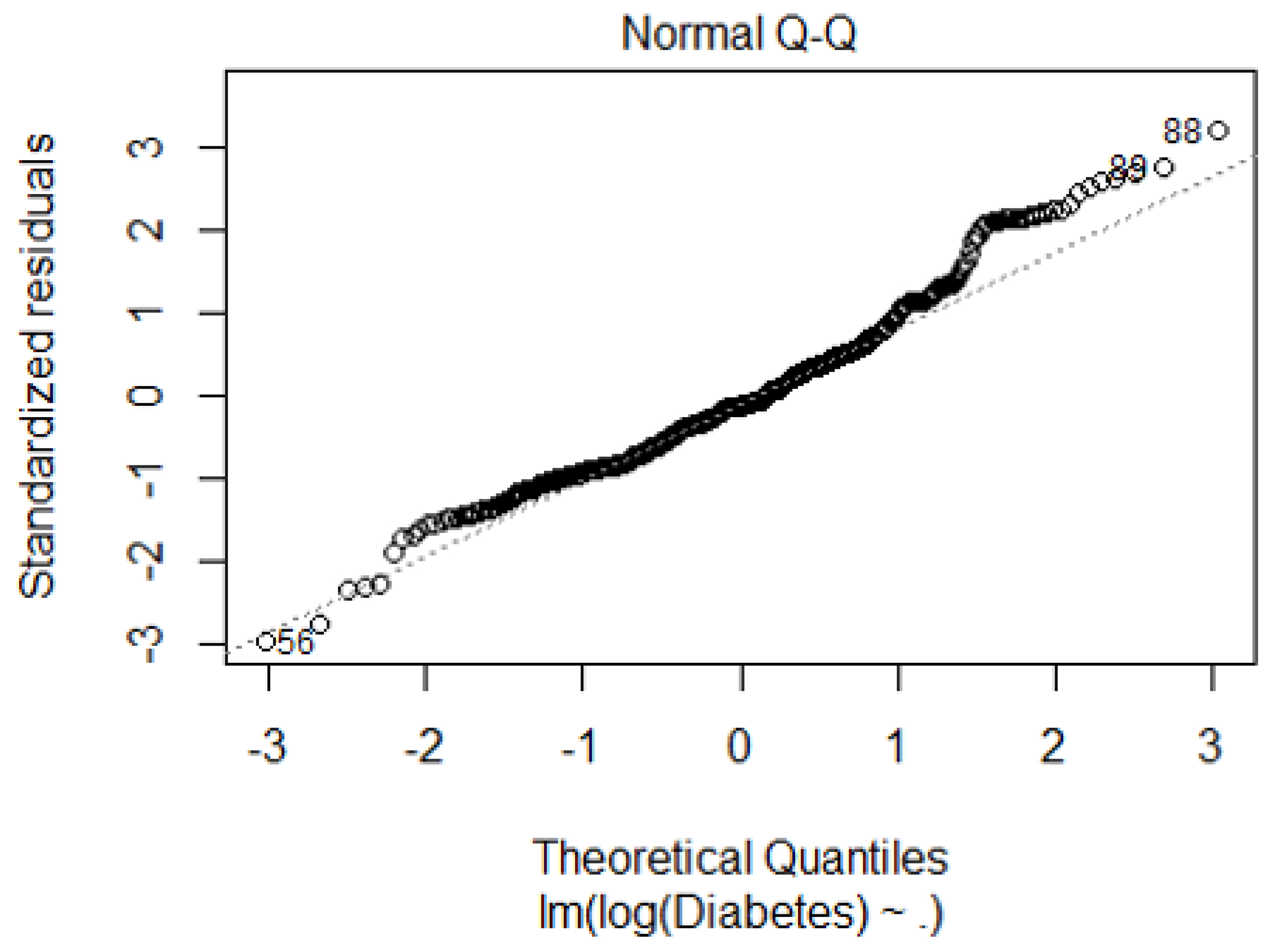

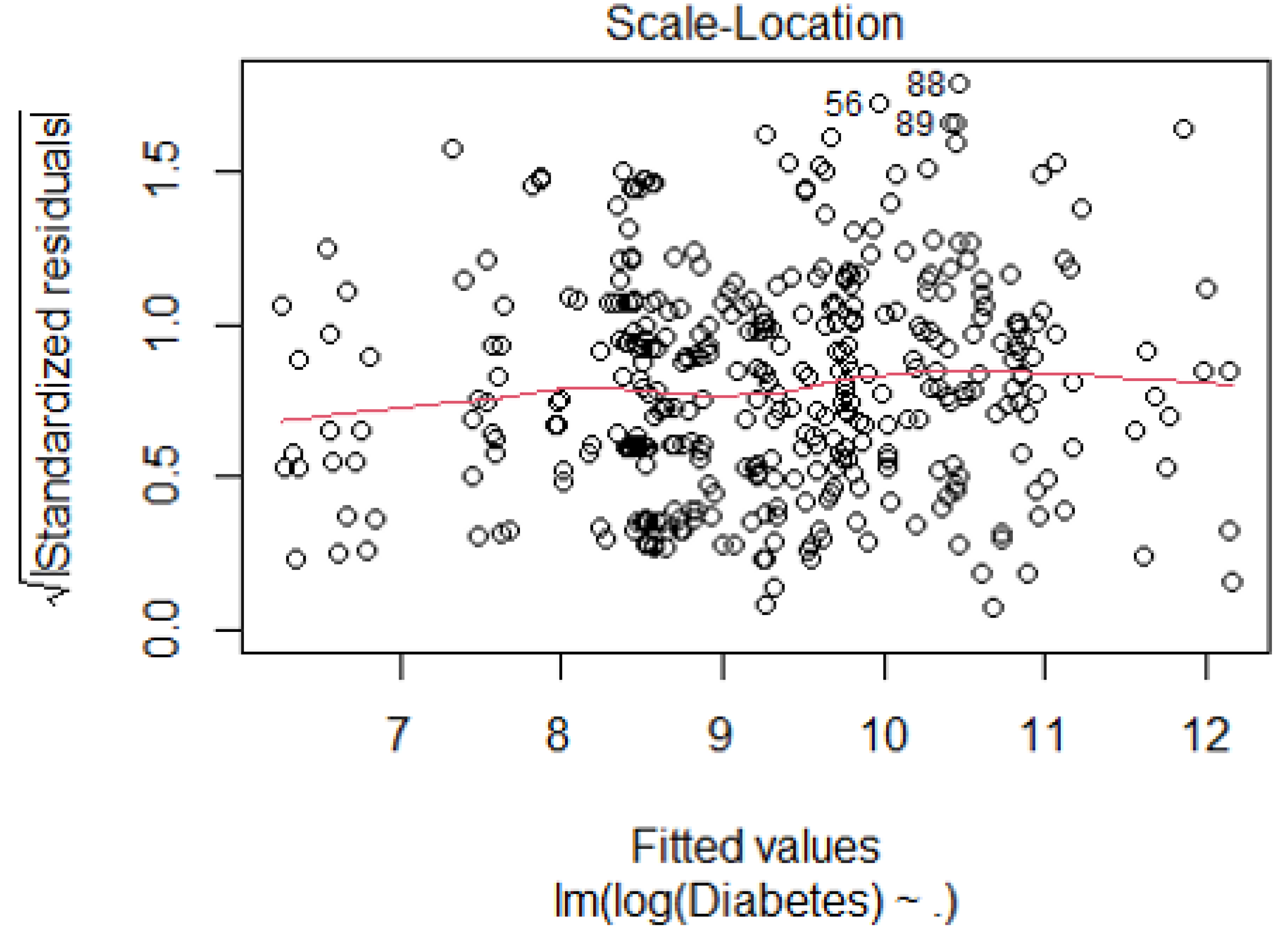

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Breusch-Pagan Test for Heteroscedasticity | Statistic: 10.052, p-value: 0.26 |

| Durbin-Watson Test for Autocorrelation | 1.64 |

| VIF (log_Mean Atrazine Levels) | 2.69 |

| VIF (Black or African American alone) | 1.14 |

| VIF (American Indian and Alaska Native alone) | 1.16 |

| VIF (Highschool graduates) | 3.09 |

| VIF (Bachelor degree) | 3.51 |

| VIF (Age) | 1.03 |

| VIF (Median Income) | 1.11 |

| VIF (BMI Obese) | 5.81 |

References

- Roglic, Gojka. WHO Global report on diabetes: A summary. International Journal of Noncommunicable Diseases 1(1):p 3-8, Apr–Jun 2016. |. [CrossRef]

- Genuth SM, Palmer JP, Nathan DM. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. In: Cowie CC, Casagrande SS, Menke A, et al., editors. Diabetes in America. 3rd edition. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (US); 2018 Aug.

- Wagenknecht LE, Lawrence JM, Isom S, et al. Trends in incidence of youth-onset type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the USA, 2002-18: results from the population-based SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11(4):242–250. [CrossRef]

- "Diabetes." hopkinsmedicine.org. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Web. Accessed 05/03/2024.

- Davis IC, Ahmadizadeh I, Randell J, Younk L, Davis SN. Understanding the impact of hypoglycemia on the cardiovascular system. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2017;12(1):21–33. [CrossRef]

- Mobasseri, Majid, Masoud Shirmohammadi, Tarlan Amiri, Nafiseh Vahed, Hossein Hosseini Fard, and Morteza Ghojazadeh. "Prevalence and Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes in the World: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Health Promotion Perspectives, vol. 10, no. 2, 2020, pp. 98–115. PubMed Central. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Ehtasham, et al. "Type 2 Diabetes." The Lancet, vol. 400, no. 10362, 1 Nov. 2022. VOLUME 400, ISSUE 10365, P1803-1820. [CrossRef]

- Teliti, M. , et al. "Risk Factors for the Development of Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes in a Single-Centre Cohort of Patients." Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research, vol. 15, 2018, pp. 424-432.

- Kosiborod, M. , et al. "Vascular Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Prevalence and Associated Factors in 38 Countries (the DISCOVER Study Program)." Cardiovascular Diabetology, vol. 17, 2018, article 150.

- Scott, E. S. , et al. "Long-Term Glycemic Variability and Vascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes: Post Hoc Analysis of the FIELD Study." Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 105, 2020, pp. e3638-e3649.

- Wagner, R. , et al. “Pathophysiology-Based Subphenotyping of Individuals at Elevated Risk for Type 2 Diabetes." Nature Medicine, vol. 27, 2021, pp. 49-57.

- Association, American Diabetes. "Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017." Diabetes Care, vol. 41, no. 5, 2018, pp. 917-928. [CrossRef]

- de Lagasnerie, G. , et al. "The Economic Burden of Diabetes to French National Health Insurance: A New Cost-of-Illness Method Based on a Combined Medicalized and Incremental Approach." European Journal of Health Economics, vol. 19, no. 2, 2018, pp. 189-201. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, B. , Aranda-Reneo, I., Oliva-Moreno, J., & Lopez-Bastida, J. (2021). Assessing the Effect of Including Social Costs in Economic Evaluations of Diabetes-Related Interventions: A Systematic Review. ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research, 13, 307–334. [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, Å. , & Fridhammar, A. (2019). Cost-effectiveness of once-weekly semaglutide versus dulaglutide and lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes with inadequate glycemic control in Sweden. Journal of Medical Economics, 22(10), 997–1005. [CrossRef]

- Hex, N. , et al. "Estimating the Current and Future Costs of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in the UK, Including Direct Health Costs and Indirect Societal and Productivity Costs." Diabetic Medicine, vol. 29, no. 7, 2012, pp. 855-862. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Bastida, J. , et al. "Social Economic Costs of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Pediatric Patients in Spain: CHRYSTAL Observational Study." Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, vol. 127, 2017, pp. 59-69. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. "Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2017." Diabetes Care, vol. 41, no. 5, May 2018, pp. 917-928. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, et al.. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors—an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97.

- Haire-Joshu D, Hill-Briggs F. The next generation of diabetes translation: a path to health equity. Annu Rev Public Health 2019, 40, 391–391. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Briggs F 2018 Health Care & Education Presidential Address: the American Diabetes Association in the era of health care transformation. Diabetes Care 2019, 42.

- Kezer, M. , & Cemalcilar, Z. (2020). A Comprehensive Investigation of Associations of Objective and Subjective Socioeconomic Status with Perceived Health and Subjective Well-Being. International Review of Social Psychology, 33(1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. , & Blader, S. L. (2020). Why Does Social Class Affect Subjective Well-Being? The Role of Status and Power. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(3), 331-348. [CrossRef]

- Garrison, S. M. , & Rodgers, J. L. (2019). Decomposing the causes of the socioeconomic status-health gradient with biometrical modeling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(6), 1030–1047. [CrossRef]

- Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002, 21, 60–76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermsen S, van Kraaij A, Camps G Low– and Medium–Socioeconomic-Status Group Members’ Perceived Challenges and Solutions for Healthy Nutrition: Qualitative Focus Group Study JMIR Hum Factors 2022;9(4):e40123. [CrossRef]

- Sherman-Wilkins KJ, Thierry AD. Education as the Great Equalizer? Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Effect of Education on Cognitive Impairment in Later Life. Geriatrics. 2019; 4(3):51. [CrossRef]

- Sisco S, Gross AL, Shih RA, et al.. The role of early-life educational quality and literacy in explaining racial disparities in cognition in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 2015; 70, 557–567.

- Qi Y, Koster A, van Boxtel M, et al. Adulthood Socioeconomic Position and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-A Comparison of Education, Occupation, Income, and Material Deprivation: The Maastricht Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1435. Published 2019 Apr 23. [CrossRef]

- Sezer B, Koster A, Albers J, et al. Socioeconomic Position and Type 2 Diabetes: The Mediating Role of Psychosocial Work Environment- the Maastricht Study. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1606036. Published 2023 Sep 7. [CrossRef]

- Gaskin DJ, Thorpe RJ Jr, McGinty EE, et al.. Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty, and place. Am J Public Health 2014, 104, 2147–2155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felicia Hill-Briggs, Nancy E. Adler, Seth A. Berkowitz, Marshall H. Chin, Tiffany L. Gary-Webb, Ana Navas-Acien, Pamela L. Thornton, Debra Haire-Joshu; Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review. Diabetes Care 1 January 2021; 44 (1): 258–279. [CrossRef]

- Scott A, Chambers D, Goyder E, O’Cathain A. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality, morbidity and diabetes management for adults with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0177210.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2017. Accessed 25 October 2020.

- Gæde P, Oellgaard J, Carstensen B, et al. Years of life gained by multifactorial intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: 21 years follow-up on the Steno-2 randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59(11):2298-2307. [CrossRef]

- Biradar DP, Rayburn AL. 1995a. Chromosomal damage induced by herbicide contamination at concentrations observed in public water supplies. J Environ Qual, 24, 2015, 1222-1225.

- Supekar SC, Gramapurohit NP. Does atrazine induce changes in predator recognition, growth, morphology, and metamorphic traits of larval skipper frogs (Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis)? J Exp Zool. Published online October 17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US). "Glossary." Toxicological Profile for Atrazine, 10 Sept. 2003, Atlanta, GA. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK597844/.

- Quackenboss JJ, Pellizzari ED, Shubat P, et al 2000. Design strategy for assessing multi-pathway exposure for children: The Minnesota Children's Pesticide Exposure Study (MNCPES). J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 10:145–158.

- Lioy PJ, Edwards RD, Freeman N, et al 2000. House dust levels of selected insecticides and a herbicide measured by the EL and LWW samplers and comparisons to hand rinses and urine metabolites. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 10:327–340.

- Dorsey, L. , and C. Portier. Atrazine: Hazard and Dose-Response Assessment and Characterization. FIFRA Scientific Advisory Panel Meeting, SAP Report No. 2000-05, 13 Feb. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, F. "The Economics of Atrazine." International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, vol. 13, 2007, pp. 437-445.

- Singh, S. , et al. "Toxicity, Degradation and Analysis of the Herbicide Atrazine." Environmental Chemistry Letters, vol. 16, 2018, pp. 211-237.

- Gupta, H. P. , et al. "Xenobiotic Mediated Diabetogenesis: Developmental Exposure to Dichlorvos or Atrazine Leads to Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes in Drosophila." Free Radical Biology and Medicine, vol. 141, 2019, pp. 461-474.

- Gupta, H. P. , Fatima, M., Pandey, R., & Ravi Ram, K. (2023). Adult exposure of atrazine alone or in combination with a carbohydrate diet hastens the onset/progression of type 2 diabetes in Drosophila. Life Sciences, 316, 121370. [CrossRef]

- Jestadi, D. B. , Phaniendra, A., Babji, U., Srinu, T., Shanmuganathan, B., & Periyasamy, L. (2014). Effects of Short Term Exposure of Atrazine on the Liver and Kidney of Normal and Diabetic Rats. Journal of Toxicology, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D. , Wang, L., Xu, Q., Wang, J., Shi, J., Ma, C., Geng, J., Zhao, M., Liu, X., Hou, J., Huo, W., Li, L., Jing, T., Wang, C., & Mao, Z. (2023). Exposure to herbicides mixtures in relation to type 2 diabetes mellitus among Chinese rural population: Results from different statistical models. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 261, 115109. [CrossRef]

- Lim S, Ahn SY, Song IC, Chung MH, Jang HC, Park KS, et al. Chronic exposure to the herbicide, atrazine, causes mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance. PLoS One. 2009;4(4): e5186. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0005186.

- Sagarkar, S.; Gandhi, D.; Devi, S.S.; Sakharkar, A.; Kapley, A. Atrazine exposure causes mitochondrial toxicity in liver and muscle cell lines. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2016, 48, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadayian, A.G.; Paez, B.; Bustamante, J.; Lores-Arnaiz, S.; Czerniczyniec, A. Mitochondrial dysfunction due to in vitro exposure to atrazine and its metabolite in striatum. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology 2023, 37, e23232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J. , Zhao, H., Qin, L., Li, X., Zhang, C., Xia, J., … & Li, J. (2018). Atrazine triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in quail (coturnix c. coturnix) cerebrum via activating xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptors and modulating cytochrome p450 systems. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 66(25), 6402-6413. [CrossRef]

- Rotimi, D. E. , Ojo, O. A., & Adeyemi, O. S. (2024). Atrazine exposure caused oxidative stress in male rats and inhibited brain-pituitary-testicular functions. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 38(1), e23579. [CrossRef]

- Rinsky JL, Hopenhayn C, Golla V, Browning S, Bush HM. Atrazine exposure in public drinking water and preterm birth. Public Health Rep. 2012 Jan-Feb;127(1):72-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonowski ND, Schäffer A, Burauel P. Still present after all these years: persistence plus potential toxicity raise questions about the use of atrazine. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2011 Feb;18(2):328-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribaudo M, Bouzaher A. Atrazine: Environmental Characteristics and Economics of Management. USDA, Agricultural Economic Report No. 699; 1994.

- Petrie, A. J. , Melvin, M. A. L., Plane, N. H., & LittleJohn, J. W.. The effectiveness of water treatment processes for removal of herbicides. (2003, July 7) Science of The Total Environment. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/004896979390287G. 7 July 0048. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Robert M.; Bahadory, Mozhgan; Tovia, Fernando; and Rostami, Hossein (2010) "Removal of Lead from Contaminated Water," International Journal of Soil, Sediment and Water: Vol. 3: Iss. 2, Article 14. Available at: https://scholarworks.umassumass.edu/intljssw/vol3/iss2/14.

- Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA. 2015 Sep 8;314(10):1021-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanakis EK and Golden, SH. Race/Ethnic Differences in Diabetes and Complications.

- Curr Diab Rep. 2013 Dec;13(6):814-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird Y, Lemstra M, Rogers M, Moraros J. The relationship between socioeconomic status/income and prevalence of diabetes and associated conditions: A cross-sectional population-based study in Saskatchewan, Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2015 Oct 12;14:93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Income, Employment, and Diabetes in Minnesota. Minnesota Department of Health; 2022.

- Saydah S, Lochner K. Socioeconomic status and risk of diabetes-related mortality in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2010 May-Jun;125(3):377-88. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacerdote C, Ricceri F, Rolandsson O, Baldi I, Chirlaque MD, Feskens E, Bendinelli B, Ardanaz E, Arriola L, Balkau B, Bergmann M, Beulens JW, Boeing H, Clavel-Chapelon F, Crowe F, de Lauzon-Guillain B, Forouhi N, Franks PW, Gallo V, Gonzalez C, Halkjær J, Illner AK, Kaaks R, Key T, Khaw KT, Navarro C, Nilsson PM, Dal Ton SO, Overvad K, Pala V, Palli D, Panico S, Polidoro S, Quirós JR, Romieu I, Sánchez MJ, Slimani N, Sluijs I, Spijkerman A, Teucher B, Tjønneland A, Tumino R, van der A D, Vergnaud AC, Wennberg P, Sharp S, Langenberg C, Riboli E, Vineis P, Wareham N. Lower educational level is a predictor of incident type 2 diabetes in European countries: the EPIC-InterAct study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012 Aug;41(4):1162-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker SM, Bowie JV, McCleary R, Gaskin DJ, LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ Jr. The Association Between Educational Attainment and Diabetes Among Men in the United States. Am J Mens Health. 2014 Jul;8(4):349-56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray N, Picone G, Sloan F, Yashkin A. Relation between BMI and diabetes mellitus and its complications among US older adults. South Med J. 2015 Jan;108(1):29-36. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andréasson K, Edqvist J, Adiels M, Björck L, Lindgren M, Sattar N. EClinicalMedicine (Part of the LANCET Discovery Science); 2022 [cited 2024 May 8]. Available from, 8 May. [CrossRef]

- K.M.V. Narayan, James P. Boyle, Theodore J. Thompson, Edward W. Gregg, David F. Williamson; Effect of BMI on Lifetime Risk for Diabetes in the U.S.. Diabetes Care 1 June 2007; 30 (6): 1562–1566. [CrossRef]

- Nitecki, M. , Gerstein, H.C., Balmakov, Y. et al. High BMI and the risk for incident type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregated cohort studies. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22, 300 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Al-Goblan AS, Al-Alfi MA, Khan MZ. Mechanism linking diabetes mellitus and obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:587-591. Published 2014 Dec 4. [CrossRef]

- Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014 Dec 4;7:587-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhupathiraju SN, Hu FB. Epidemiology of Obesity and Diabetes and Their Cardiovascular Complications. Circ Res. 2016 May 27;118(11):1723-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | N | Standard Deviation | Mean | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 405 | 167,382.89 | 189,155.25 | 4,610 | 87,331 | 1,580,081.00 |

| Fruits and Vegetable | 405 | 53,870.61 | 24,627.67 | 371 | 10,585 | 257,894.50 |

| Physical activity | 405 | 227,185.90 | 92,940.88 | 2,253 | 42,243 | 811,591.00 |

| Atrazine Exposure | 405 | 315,117.43 | 93,357.76 | 258 | 26,180 | 1,600,000.00 |

| No Physical Activity | 405 | 93,413.65 | 47,914.23 | 1,326 | 24,004 | 425,495.00 |

| Diabetes | 405 | 37,640.94 | 20,067.52 | 517 | 10,381 | 189,609.80 |

| BMI Obese | 405 | 90,299.11 | 56,746.90 | 1,491 | 30,149 | 505,626.00 |

| BMI Overweight | 405 | 233,187.52 | 123,280.13 | 3,197 | 59,362 | 1,042,854.00 |

| Age | 405 | 4.62 | 41.12 | 29.1 | 41.2 | 46.2 |

| White alone | 405 | 2,879,614.61 | 581,883.41 | 6,537 | 196,152 | 9,115,388.00 |

| Black or African American alone | 405 | 1,220,136.23 | 109,248.61 | 295 | 19,935 | 6,749,973.00 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native alone | 405 | 352,743.26 | 15,583.28 | 22 | 512 | 1,145,408.00 |

| Asian alone | 405 | 324,465.26 | 28,166.94 | 31 | 3,413 | 456,752.00 |

| Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders alone | 405 | 160,000 | 9,871 | 0 | 78 | 456,790 |

| Median Income | 405 | 36,473.61 | 2,867.83 | 806 | 52,638 | 226,041.00 |

| Less than high school | 405 | 10,443.98 | 4,046.81 | 1.7 | 2,419 | 59,742.00 |

| High school graduates | 405 | 9,247.18 | 2,596.58 | 22.1 | 1,670 | 42,571.30 |

| Some college or associate | 405 | 18,650.43 | 6,129.49 | 4.17 | 1,827 | 118,264.27 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 405 | 19,432.99 | 8,900.17 | 4 | 4,962 | 116,518.00 |

| Fold Number | Mean Squared Error (MSE) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.4449 |

| 2 | 0.0692 |

| 3 | 0.0998 |

| 4 | 0.2880 |

| 5 | 0.1749 |

| 6 | 0.0710 |

| 7 | 0.1194 |

| 8 | 0.1074 |

| 9 | 0.1285 |

| 10 | 0.0919 |

| Average | 0.1595 |

| Variable | Lower Bound Value | Upper Bound Value | Predicted Lower Bound | Predicted Upper Bound | Change in Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_Mean Atrazine Levels | 8.958 | 11.105 | 8.687 | 9.750 | +1.063 |

| Black or African American alone | 79,682 | 86,069 | 9.219 | 9.218 | -0.001 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native alone | 10,828 | 10,856 | 9.219 | 9.219 | 0.000 |

| Highschool graduates | 2,096 | 2,570 | 9.221 | 9.217 | -0.004 |

| Bachelor degree | 6,922 | 8,376 | 9.230 | 9.208 | -0.022 |

| Age | 40.927 | 41.327 | 9.217 | 9.220 | +0.003 |

| Median Income | 50,429 | 54,159 | 9.208 | 9.229 | +0.021 |

| BMI Obese | 27,604 | 68,903 | 9.056 | 9.381 | +0.325 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std Error | t-Value | p-Value | Significance | 95% CI Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.3745 | 0.425 | 7.945 | 2.41e-14 | ** | (2.5393, 4.2097) |

| log_Mean Atrazine Levels | 0.4951 | 0.020 | 24.993 | 3.17e-81 | ** | (0.4562, 0.5341) |

| Black or African American alone | -5.23e-08 | 8.09e-08 | -0.647 | 0.518 | (-2.11e-07, 1.07e-07) | |

| American Indian and Alaska Native alone | -3.31e-07 | 3.51e-07 | -0.943 | 0.346 | (-1.02e-06, 3.59e-07) | |

| Highschool graduates | -8.09e-06 | 9.84e-06 | -0.822 | 0.412 | (-2.74e-05, 1.13e-05) | |

| Bachelor degree | -1.53e-05 | 2.79e-06 | -5.468 | 8.43e-08 | ** | (-2.07e-05, -9.77e-06) |

| Age | 0.0086 | 0.008 | 1.040 | 0.299 | (-0.0077, 0.0249) | |

| Median Income | 5.48e-06 | 1.74e-06 | 3.144 | 0.0018 | ** | (2.05e-06, 8.91e-06) |

| BMI Obese | 7.87e-06 | 7.59e-07 | 10.370 | 2.88e-22 | ** | (6.38e-06, 9.36e-06) |

| Variable | Mean Coeff | Std Error | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.5021 | 0.3883 | 3.7633 | 5.2680 |

| log_Mean Atrazine Levels | 0.3943 | 0.0303 | 0.3316 | 0.4495 |

| Black or African American alone | -1.76e-07 | 1.98e-07 | -3.31e-07 | -4.87e-08 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native alone | -2.46e-07 | 3.06e-06 | -1.31e-06 | -3.25e-08 |

| Highschool graduates | -2.63e-05 | 1.09e-05 | -4.80e-05 | -4.36e-06 |

| Bachelor degree | -1.80e-05 | 3.49e-06 | -2.32e-05 | -9.66e-06 |

| Age | 0.0048 | 0.0046 | -0.0044 | 0.0147 |

| Median Income | 3.00e-06 | 1.53e-06 | 1.69e-07 | 6.01e-06 |

| BMI Obese | 1.37e-05 | 1.34e-06 | 1.13e-05 | 1.64e-05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).