1. Introduction

Patients with dysphagia are increasing with the aging of the population. Recently, the concepts of frailty, as well as age, has gained importance. In addition, one of the causes of frailty is a decline in oral and swallowing functions, which is now gaining attention as oral frailty [

1]. We previously reported that the deterioration of oral function was associated with the appearance of new frailty in patients admitted to the ICU, and one of the mechanisms of this association was assumed to be a secondary infection, especially aspiration pneumonia [

2].

Low tongue pressure, which is one of the objective items of oral frailty [

3], is associated with frailty [

4] and aspiration risk [

5]. Therefore, it is reasonable and beneficial for admitted patients to receive tongue pressure measurement screening before oral intake in order to prevent aspiration. In addition, ensuring a posture that can exert stronger tongue pressure is very important in reducing the risk of aspiration. It is not yet properly recognized in clinical medicine whether changes in posture can cause instability of the head and trunk, which is resulting in changes in oral and swallowing functions such as bite force or tongue pressure [

6]. The importance of plantar grounding for trunk retention has been highlighted, especially in the sitting position; however, this report can hardly be found in global journals.

In fact, non-frailty individuals do not perceive the importance of plantar grounding while sitting and can swallow regardless of the body position. We hypothesized that the importance of plantar grounding would become apparent in individuals with frailty because of the increased instability of the trunk. This study aimed to evaluate changes in tongue pressure with body position and to determine whether the progression of frailty is one of the factors contributing to these changes.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a single-center, prospective, observational study. A total of 67 individuals were enrolled, 23 medical staff members as healthy controls and 44 patients admitted to the emergency department between April 1 and July 31, 2023, and treated as inpatients for at least 48 hours. The enrolled patients did not receive ventilatory management or tube feeding and central venous nutritional therapy, and all fasted for <3 days. A post-gastrostomy patient who had not taken an oral intake prior to admission was excluded. Patients with vertebral or facial fractures were excluded in consideration of the effects on positional retention and occlusion. Patients with cognitive dysfunction were also excluded because tongue pressure measurements were unable to perform accurately. Under these exclusion criteria, none of the patients with Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) ≥7 was included.

Patient background information regarding age, sex, frailty, and tongue pressure was collected. CFS was used to assess frailty [

7]. Tongue pressure was measured from the time of admission to the day before oral intake. Tongue pressure was measured in each of the following positions (Supplemental Figure): dorsal (Group D), sitting (Group S), and sitting with plantar grounding (Group SP). Tongue pressure was measured with a JM-TPM tongue depressometer (JMS, Hiroshima, Japan). Measurements began with the posture the patient was in at the time of the visit; subsequent postures were determined by the patient. In the sitting position, the bed was set at a 45° gudgeon up and a step was placed between the bed rail and the sole of the foot. Although tongue pressure and occlusal force are highly related [

8] and similar changes in body position have been reported [

9], we employed tongue pressure as an objective item of oral function in this study. The reason for this is that occlusal force may change depending on the number of teeth [

10], which is considered as a major bias in this study. For patients with dentures, tongue pressure was measured under the same circumstances of eating before admission.

Measurements were categorized by CFS and presented as the mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences in continuous variables between the groups, and measurements between groups, with p < 0.05 indicating a significant difference. All statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0; GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA).

3. Results

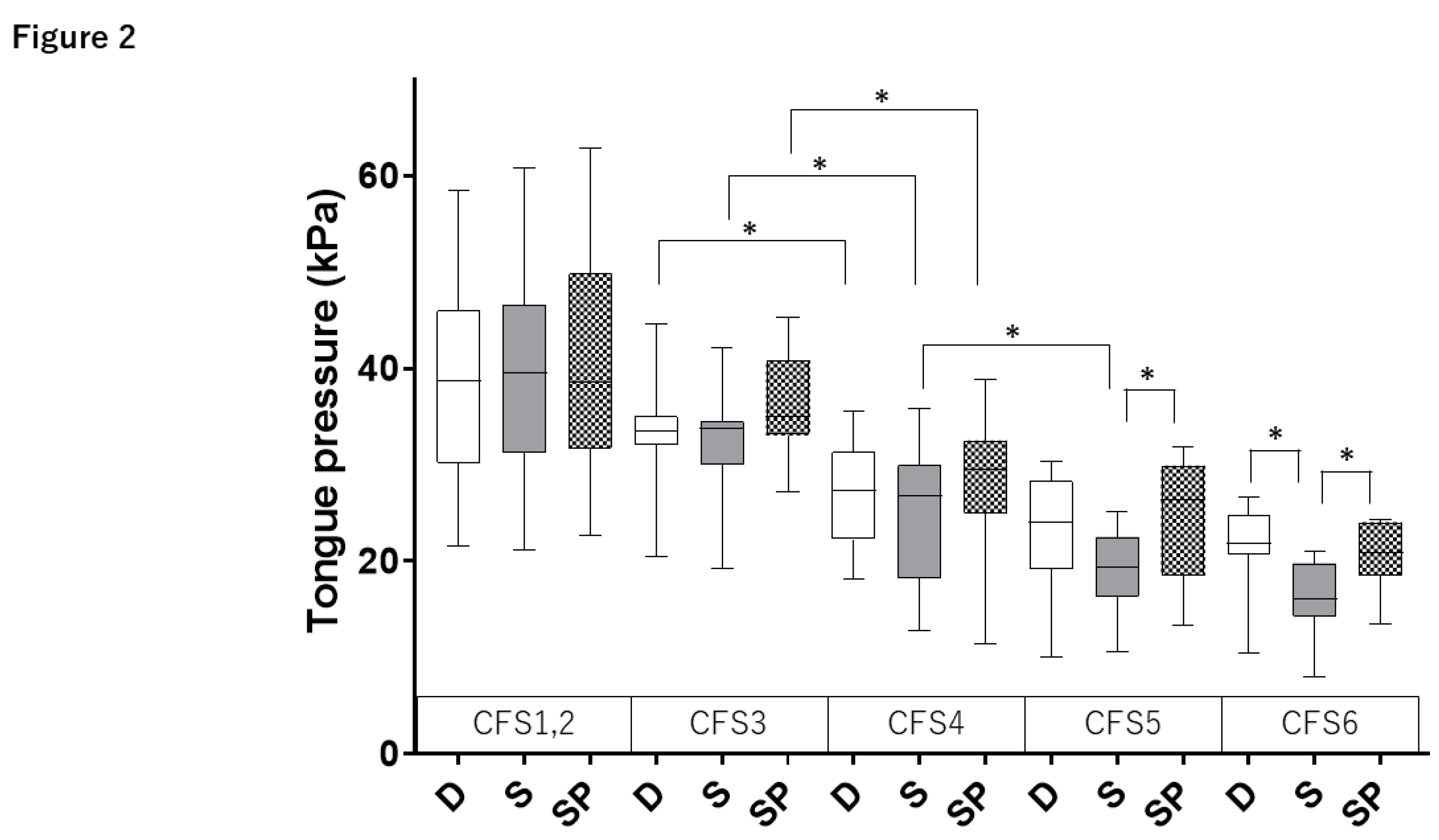

As shown in

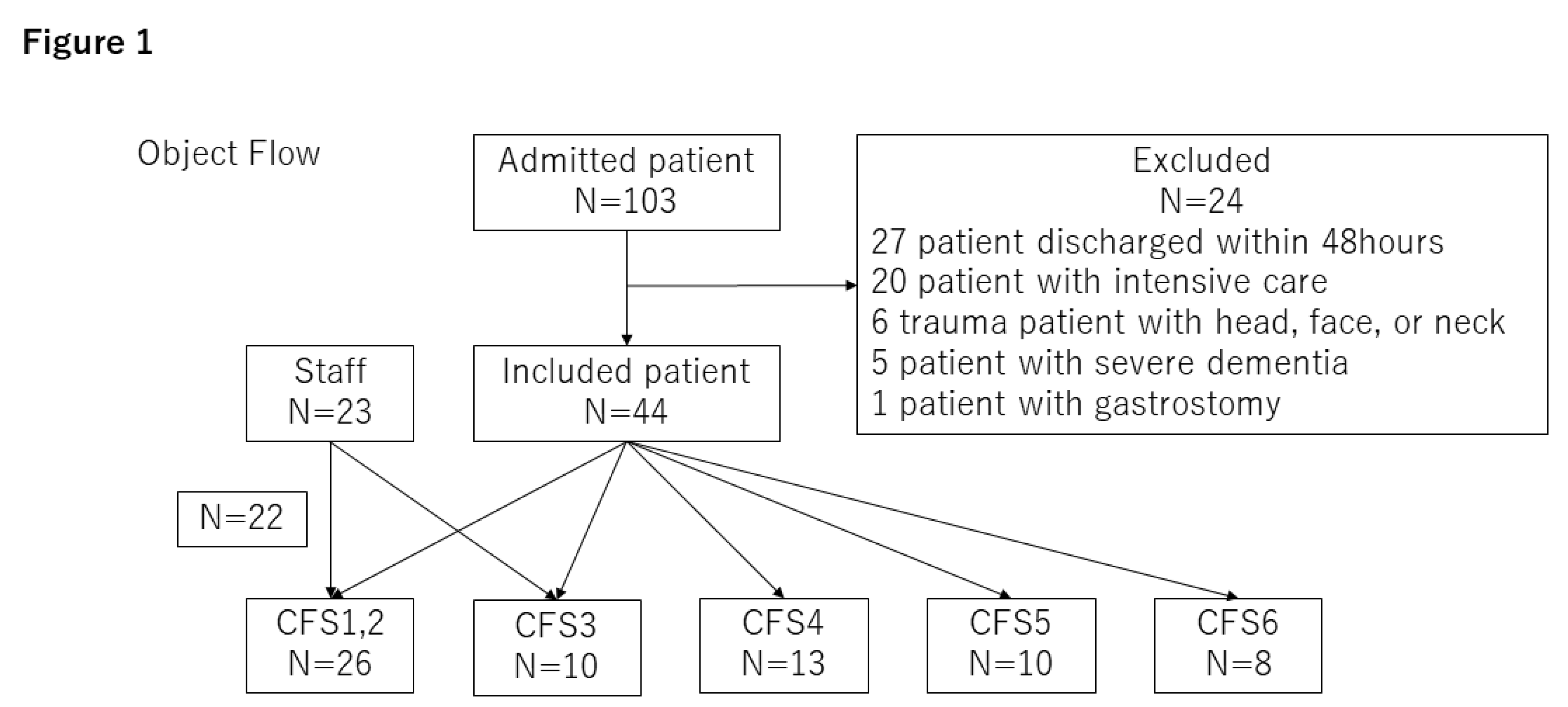

Figure 1, the participants were divided by CFS. Tongue pressure for each body position is shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 2. CFS1, 2, and 3 did not show any differences in the body position. Compared to CFS3, CFS4 showed a significant decrease in all body position (group D: 27.0 ± 5.8 vs. 33.4 ± 5.6 kPa; group S: 25.1 ± 7.9 vs. 32.5 ± 5.5 kPa; and group SP: 28.2 ± 8.1 vs. 36.3 ± 5.4 kPa;

p < 0.05). Compared to CFS4, CFS5 showed a significant decrease only in group S (19.0 ± 4.4 vs. 25.1 ± 7.9 kPa,

p < 0.05). No significant difference was observed between CFS5 and CFS6 (group D: 23.1 ± 5.9 vs. 21.4 ± 5.8 kPa,

p = 0.53; group S: 19.0 ± 4.4 vs. 16.3 ± 4.9 kPa,

p = 0.21; and group SP: 24.4 ± 6.2 vs. 20.6 ± 4.1 kPa,

p = 0.16).

Differences in tongue pressure between body positions were observed for CFS5 and CFS6. In CFS5, there were no significant differences between group D and group S (23.1 ± 5.9 vs. 19.0 ± 4.4 kPa, p = 0.11); however, a significant difference was observed between group S and group SP (19.0 ± 4.4 vs. 24.4 ± 6.2 kPa, p < 0.05). In CFS6, group S showed a significant decrease in tongue pressure compared to group D and group SP (p < 0.05) (group D: 21.4 ± 5.8; group S: 16.3 ± 4.9; and group SP: 20.6 ± 4.1 kPa).

4. Discussion

This study was designed to determine whether tongue pressure changes with body position in patients with frailty. In the CFS proposed by Rockwood et al. [

7], Scale 4 or more is recognized as frailty. In the present study, a significant decrease in tongue pressure was observed with CFS4, and tongue pressure tended to decrease even with CFS3. Thus, decrease in tongue pressure may be a useful tool for the early recognition of the early stages of frailty. In fact, Tanaka et al. demonstrated the concept of “Oral Frailty” that comprehensively reflects occlusal strength, swallowing function, and bacteriological/immunological status of the oral cavity, which is considered a preliminary stage of frailty [

1]. In addition, we reported that oral dysfunction represented by the loss of molar teeth, is related to the prognosis of older adults in the intensive care unit [

2]. There was no difference in tongue pressure according to body position in participants with CFS4 or less. In contrast, in participants with CFS6, there was a significant decrease in tongue pressure in the sitting position (Group S) and a significant alleviation in the plantar grounding position (Group SP). Although there was no significant difference between Group D and Group S in CFS5, the degree of tongue pressure reduction in the sitting position tended to increase as frailty progressed. This mechanism can be explained by referring to reports that the instability of the head position causes a decrease in tongue pressure [

6].

The clinical implementation of this study is not only a solution to pulmonary aspiration, but also its early detection. This is because swallowing is categorized into three phases: oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal [

11]. We focused on tongue pressure, which is the most important element in transmitting the mass from the oral cavity to the pharynx. Tongue pressure may vary depending on the patient’s condition and can be managed through oral care or rehabilitation. Furthermore, it can also be used as objective indicator. Video endoscopy/video fluorography (VE/VF) is often performed in clinical practice, especially in hospitalized patients, where VE is preferred because it does not require room movement, use of contrast media, or exposure to radiation [

12]. However, VE requires highly experienced staff and is somewhat invasive to the patient. In addition to these three phases, cognitive and masticatory functions must be assessed to achieve feeding without aspiration [

13,

14]. Cognitive function contributes to the recognition of the size or hardness of food and movement of the appropriate amount of food into the oral cavity. Masticatory function is necessary to chew food appropriately and finely, and involves the number of teeth, bite strength, and salivation [

15]. Cognitive function is also needed to appropriately shift to the swallowing motion. The loss of these functions can be compensated to some extent by adjusting the food form and caregiver’s ingenuity.

The interpretations of the results are as follows: The muscular strength of the oral cavity and pharynx, which are involved in tongue pressure, decreases with the progression of frailty. In addition, the finding that tongue pressure was lower in Group S than in Group D suggests that other skeletal muscles, such as the spinal muscles, compensated for the decreased tongue pressure. Furthermore, the finding that tongue pressure in Group SP was better than that in Group S suggests that plantar grounding improved the ability of skeletal muscles to stabilize the trunk in the sitting position. It makes sense that this compensatory effect would be insufficient in advanced frailty, such as CFS6, where limb muscles would be weakened.

This study had some limitations. The pressure applied to the plantar surface during plantar grounding was not measured, and the postural changes were not evaluated in detail. Although the stability of the head, neck, and trunk is important for stable chewing and swallowing [

8], this mechanism was not proven in this study and requires further investigation in the field of kinesiology. As mentioned above, swallowing process is so complex that it is impossible to assess swallowing function with tongue pressure alone. However, it is an important finding in clinical medicine that the progression of frailty and/or body instability causes a decrease in tongue pressure during swallowing, and we hope that avoiding oral intake in positions that decrease tongue pressure will help prevent aspiration.

5. Conclusions

The tongue pressure showed a decreasing trend with the progression of frailty. It also decreases in the sitting position compared to the dorsal position, which is alleviated in the plantar grounding position.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplemental Figure. Illustration of each position: pillows were placed in the supine position and the reclining angle was set at 60° in the sitting position.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, YF; Methodology, YF.; Investigation, YF, HN; Resources, YF; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, YF.; Writing – Review & Editing, KS, MK; Supervision, MK.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (22K16634 to YF). We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol and statistical analyses plan were approved by the review board at Kakogawa Central City Hospital (IRB number: R5-016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tanaka, T. , Takahashi, K., Hirano, H., Kikutani, T., Watanabe, Y., Ohara, Y., Furuya, H., Tetsuo, T., Akishita, M., & Iijima, K. (2018). Oral frailty as a risk factor for physical frailty and mortality in community-dwelling elderly. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 73, 1661–1667. [CrossRef]

- Fujinami, Y., Hifumi, T., Ono, Y., Saito, M., Okazaki, T., Shinohara, N., Akiyama, K., Kunikata, M., Inoue, S., Kotani, J., & Kuroda, Y. (2021). Malocclusion of molar teeth is associated with activities of daily living loss and delirium in elderly critically ill older patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10, 2157. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. C. , Ku, E. N., Lin, C. W., Tsai, P. F., Wang, J. L., Yen, Y. F., Ko, N. Y., Ko, W. C., & Lee, N. Y. (2023). Tongue pressure during swallowing is an independent risk factor for aspiration pneumonia in middle-aged and older hospitalized patients: an observational study. Geriatrics and Gerontology International. [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, S. , Fujii, W., Matsumoto, E., Yamaguchi, K., & Hiratsuka, M. (2023). Association between tongue pressure and oral status and activities of daily living in stroke patients admitted to a convalescent rehabilitation unit. Clinical and Experimental Dental Research. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, P. T. , Műhelyi, V., Halász, T., Béres-Molnár, K. A., Folyovich, A., & Balogh, Z. (2023). Aspiration risk screening with tongue pressure measurement in acute stroke: a diagnostic accuracy study using STARD guidelines. SAGE Open Nursing, 9, 23779608231219183. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K. , Nagami, S., Kurozumi, C., Harayama, S., Nakamura, M., Ikeno, M., Yano, J., Yokoyama, T., Kanai, S., & Fukunaga, S. (2023). Effect of spinal sagittal alignment in sitting posture on swallowing function in healthy adult women: a cross-sectional study. Dysphagia, 38, 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K., Awalt, E., Carver, D., & MacKnight, C. (2000). Feasibility and measurement properties of the functional reach and the timed up and go tests in the Canadian study of health and aging. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 55, M70–M73. [CrossRef]

- Moritoyo, R. , Nakagawa, K., Yoshimi, K., Yamaguchi, K., Ishii, M., Yanagida, R., Namiki, C., & Tohara, H. (2023). Relationship between the jaw-closing force and dietary form in older adults without occlusal support requiring nursing care. Scientific Reports, 13, 22551. [CrossRef]

- Jauregi, M. , Amezua, X., Manso, A. P., & Solaberrieta, E. (2023). Positional influence of center of masticatory forces on occlusal contact forces using a digital occlusal analyzer. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 129, 930.e1–930.e8. [CrossRef]

- Ikebe, K., Matsuda, K., Murai, S., Maeda, Y., & Nokubi, T. (2010). Validation of the Eichner index in relation to occlusal force and masticatory performance. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 23, 521–524.

- Zuercher, P. , Moret, C. S., Dziewas, R., & Schefold, J. C. (2019). Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Critical Care, 23, 103. [CrossRef]

- Scheel, R., Pisegna, J. M., McNally, E., Noordzij, J. P., & Langmore, S. E. (2016). Endoscopic assessment of swallowing after prolonged intubation in the ICU setting. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 125, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T. , Zhang, Y., Wang, K., Yu, H., Lin, L., Qin, X., Wu, T., Chen, D., Wu, Y., & Hu, Y. (2023). Identifying risk factors for aspiration in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 2023, 2198259. [CrossRef]

- Miyagami, T. , Nishizaki, Y., Imada, R., Yamaguchi, K., Nojima, M., Kataoka, K., Sakairi, M., Aoki, N., Furusaka, T., Kushiro, S., Yang, K. S., Morikawa, T., Tohara, H., & Naito, T. (2024). Dental care to reduce aspiration pneumonia recurrence: a prospective cohort study. International Dental Journal. [CrossRef]

- Peyron, M. A. , Woda, A., Bourdiol, P., & Hennequin, M. (2017). Age-related changes in mastication. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 44, 299–312. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).