Submitted:

16 May 2024

Posted:

17 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

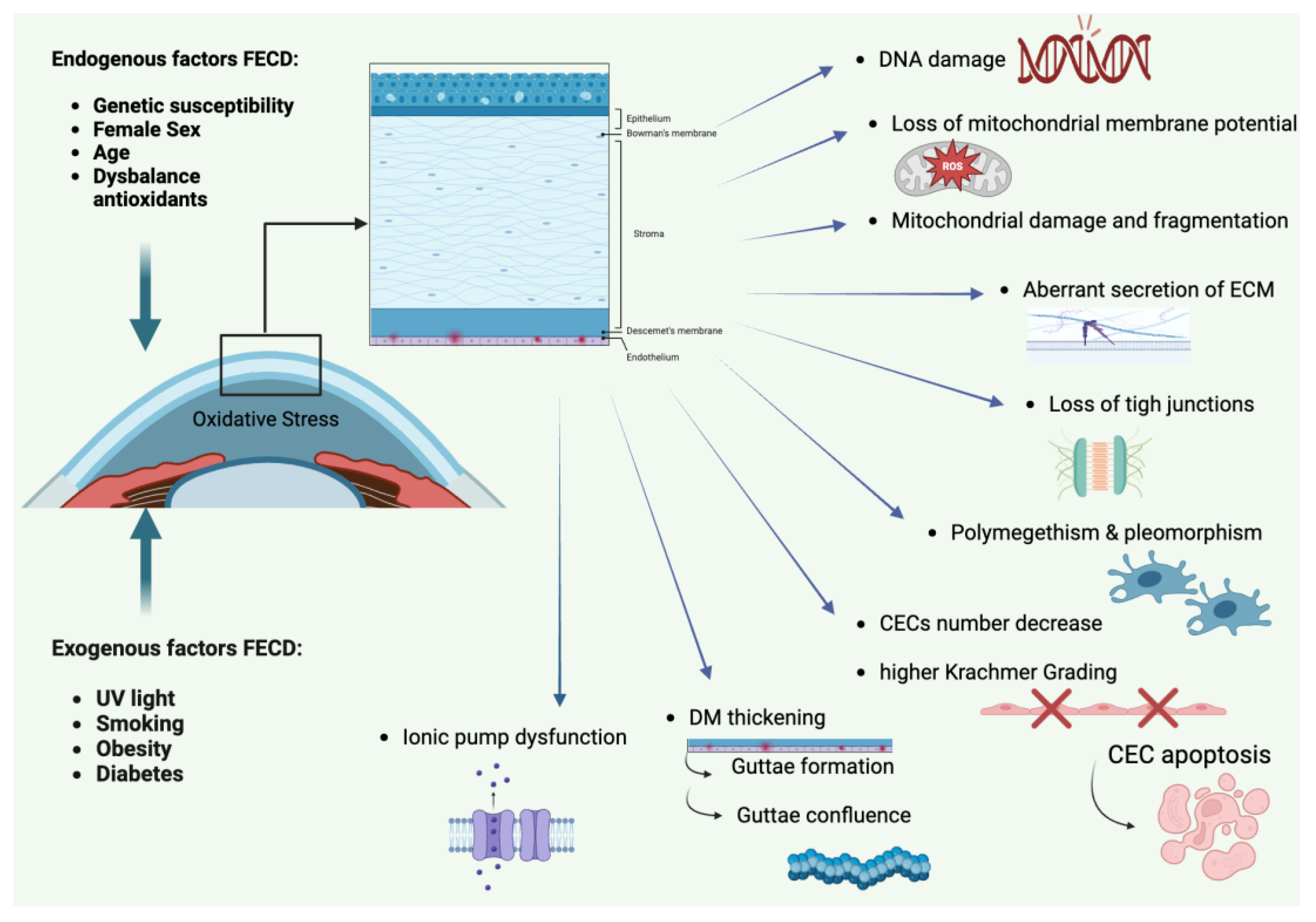

1. Introduction

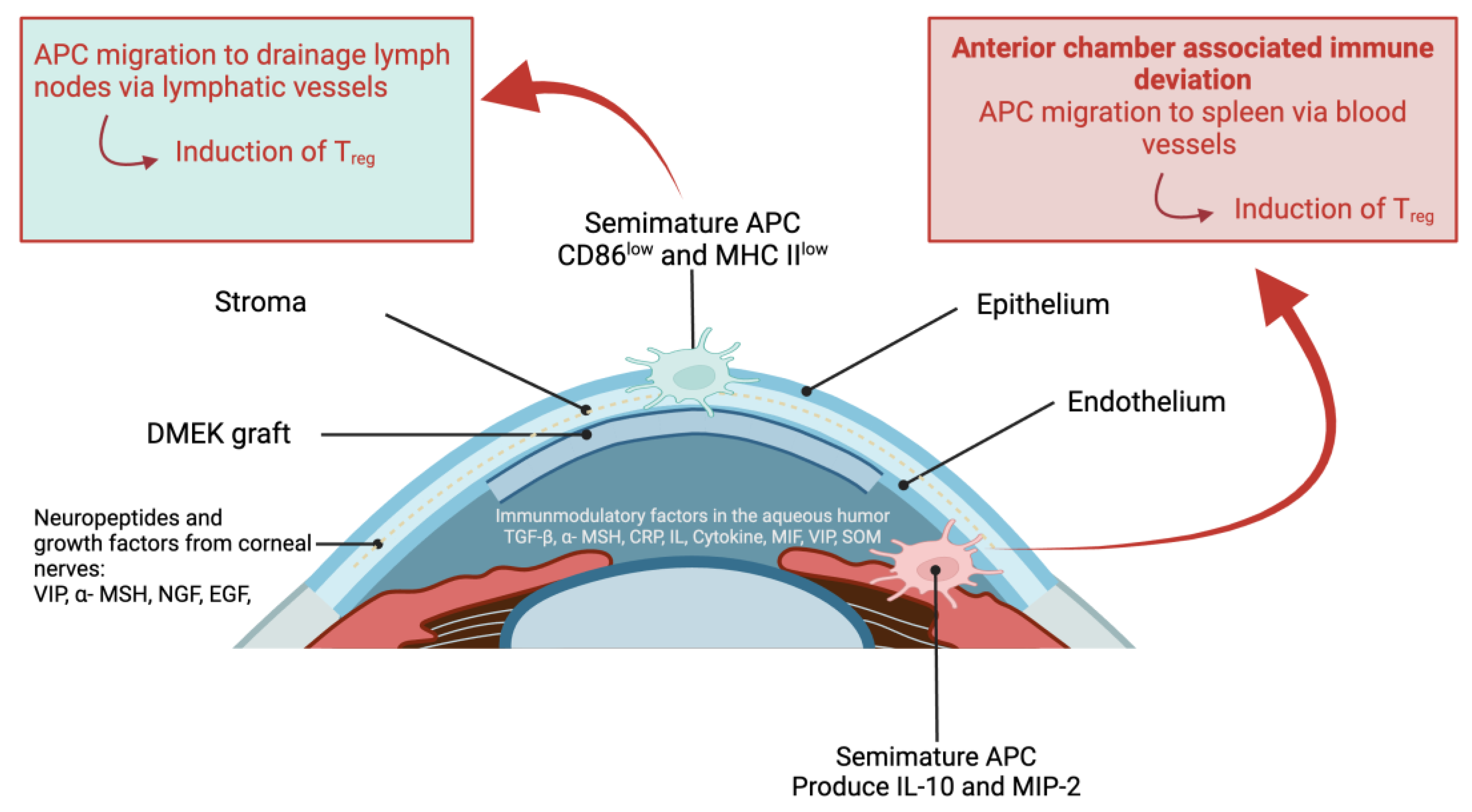

2. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK)

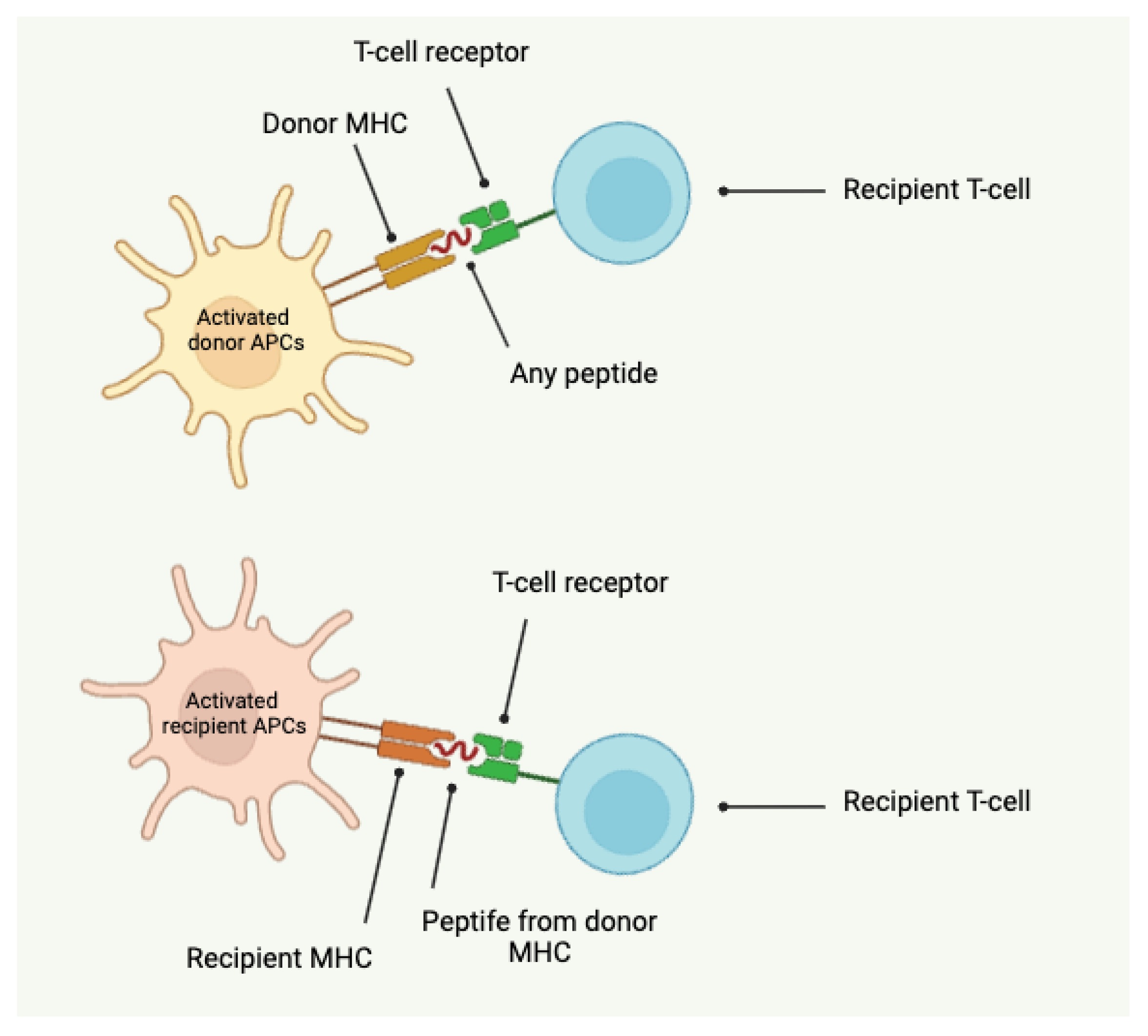

- Direct alloantigen recognition involves donor antigen-presenting cells (APCs) presenting intact donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules to recipient T cells. This direct presentation leads to activation of the recipient's T cells against the donor antigens.

- Indirect alloantigen recognition occurs when recipient APCs present processed donor antigens, including donor MHC peptides, on recipient MHC molecules to recipient T cells. This indirect pathway can also trigger an immune response against the donor graft.

2.1. DMEK: Clinical procedure

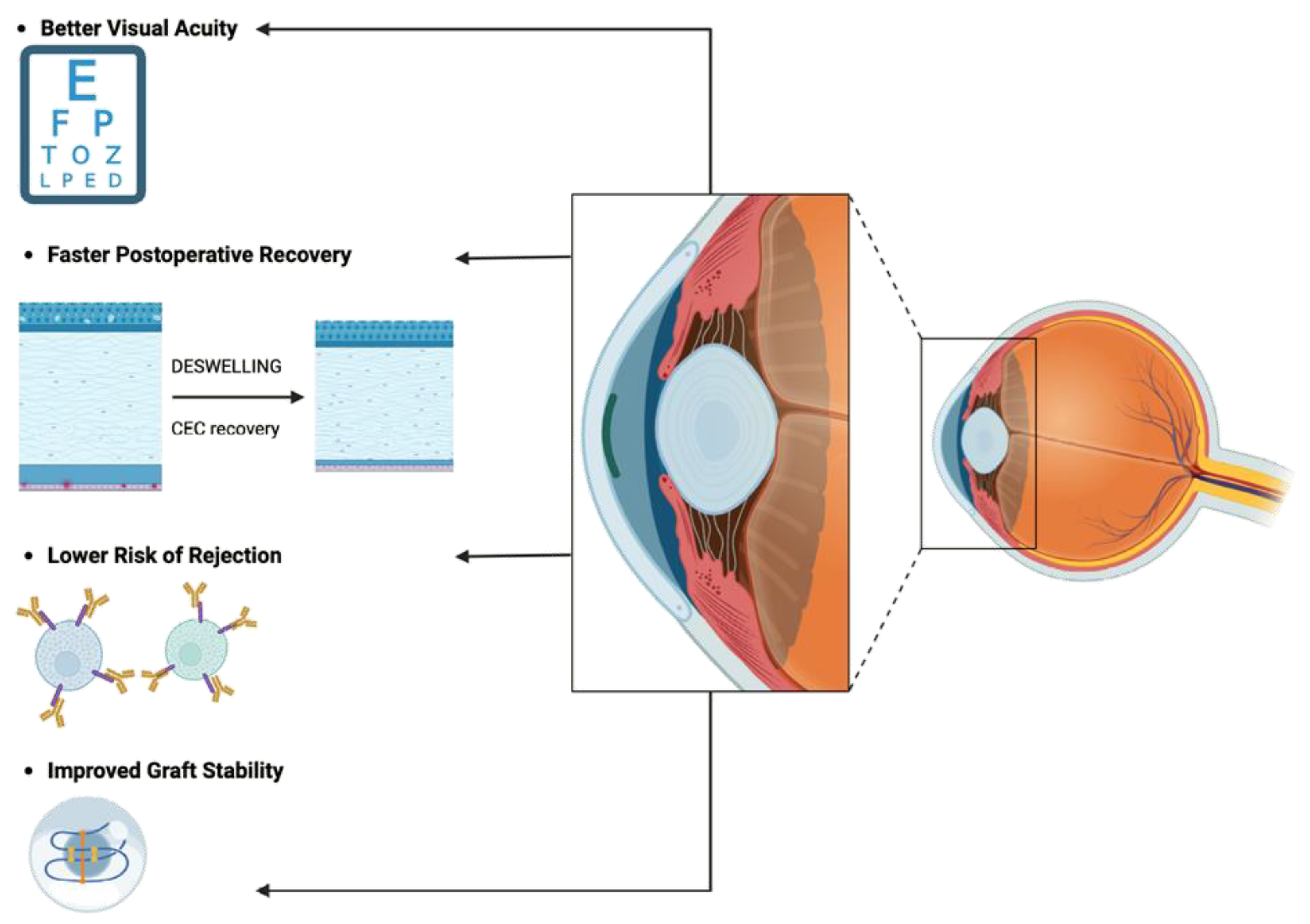

2.2. DMEK: Advantages

- Lower Risk of Rejection: DMEK's targeted approach minimizes antigenic stimulus, reducing the risk of immune-mediated rejection and enhancing graft survival rates [36].

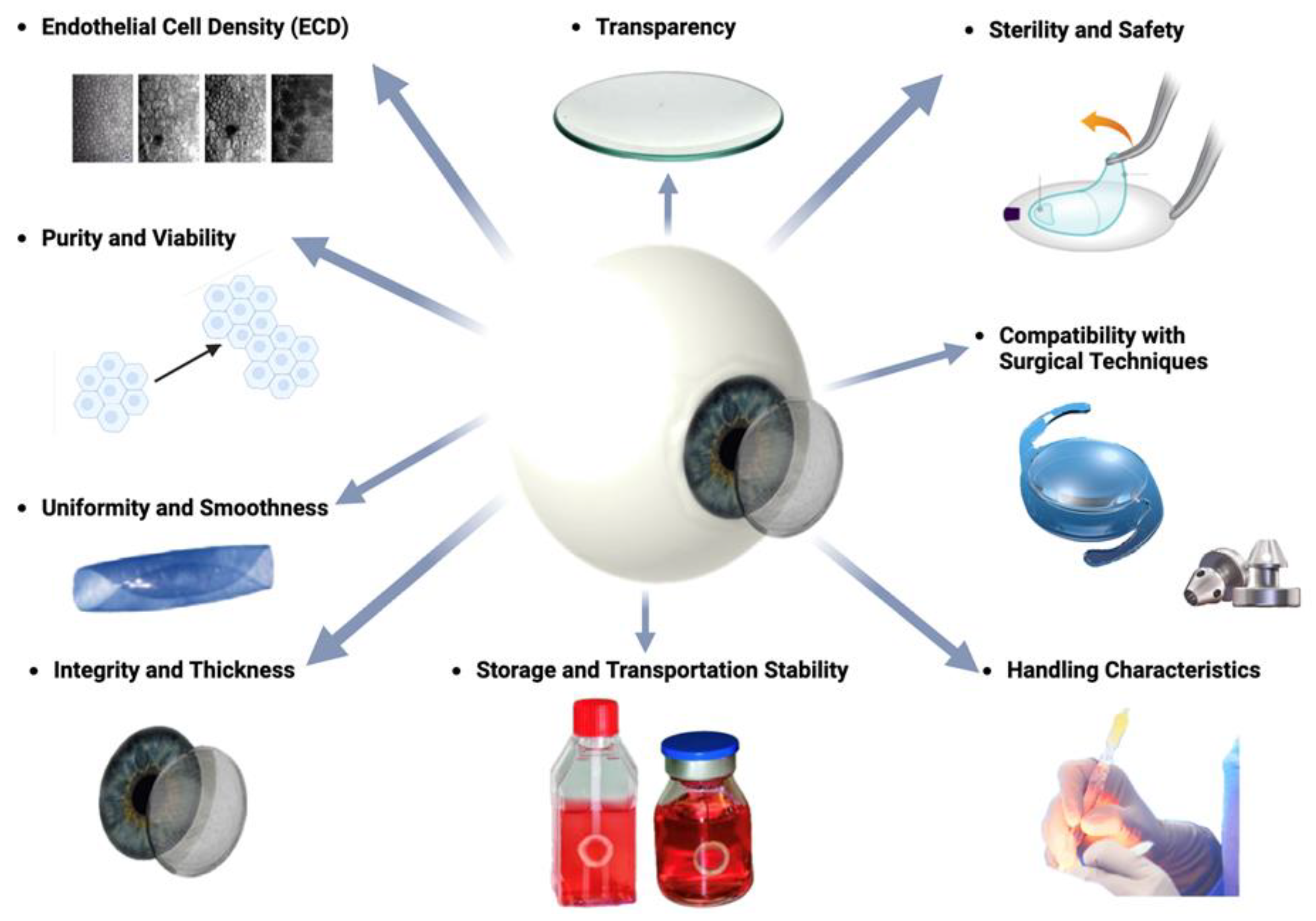

2.3. DMEK: Requirements for grafts

- Transparency: Unlike many other tissues in the body, the cornea is avascular, meaning it lacks blood vessels. Instead, it receives oxygen and nutrients from the tear film on its outer surface and the aqueous humor within the anterior chamber of the eye. This avascular nature reduces light absorption and maintains corneal transparency.

- Purity and Viability: The graft should be free from contaminants, debris, or cellular remnants that could provoke an immune response or impair endothelial cell function. Viability of endothelial cells within the graft is essential for their survival and function following transplantation [36].

- Uniformity and Smoothness: The DMEK graft should exhibit uniform thickness and smoothness to facilitate handling and positioning during surgery. Irregularities or unevenness in the graft may lead to difficulties in unfolding and adherence to the recipient cornea [54,55]. Factors, which must be taken into account is the stripping, splitting and rolling behavior as well as the fragility [43,44].

- Sterility and Safety: Sterility of the graft is paramount to prevent the risk of infection or disease transmission. Donor tissue must undergo thorough screening and processing procedures to ensure safety and minimize the risk of adverse events post-transplantation.

- Storage and Transportation Stability: Grafts should maintain stability and viability during storage and transportation from the donor to the recipient surgical site. Proper storage conditions, such as maintenance of temperature and hydration levels, are essential to preserve graft quality.

- Compatibility with Surgical Techniques: The DMEK graft should be compatible with surgical instrumentation and techniques employed during transplantation. Grafts that are too rigid or fragile may pose challenges during surgical manipulation and insertion.

3. DMEK: Recent developments and future directions

3.1. Advancements in in vitro cell culture for DMEK

3.1.1. Selective cell isolation for cell culture in vitro

- Descemetorhexis with bubble technique (DEBUT): DEBUT is a novel method that involves creating a small air bubble under DM to detach it from the stroma. This technique allows for precise and controlled removal of DM with attached endothelial cells, minimizing trauma to the tissue.

- Endothelial cell sheet harvesting: In this approach, CECs are harvested is intact cell sheets using a specially designed spatula or forceps. This method preserves cell-cell junctions and reduces cellular damage, leading to higher cell viability post-harvest.

- Femtosecond laser-assisted techniques: Femtosecond lasers can be used to create precise cuts along the DM, facilitating selective removal of the endothelial layer. This technique offers high precision and minimizes collateral damage to adjacent tissues.

- Perfusion and microfluidic devices: Perfusion systems and microfluidic devices have been developed to isolate CECs based on their unique properties, such as cell size or adhesion characteristics. These systems allow for automated and gentle cell isolation, improving yield and purity of harvested cells.

3.1.2. Cell culture media composition

- Growth factors: Growth factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) play key roles in promoting CEC proliferation and maintaining cell viability. These factors stimulate cell division and support the growth of healthy CEC populations.

- Serum supplements: Fetal bovine serum (FBS) or human serum albumin (HSA) are commonly used as supplements in culture media to provide essential nutrients, hormones, and growth factors necessary for CEC growth and survival.

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) components: ECM proteins like collagen, laminin, and fibronectin can be incorporated into culture media to mimic the natural environment of CECs and promote cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation.

- Osmolarity and pH control: Maintaining optimal osmolarity and pH levels in culture media is crucial for CEC health and function. Isotonic solutions and buffering agents are used to regulate osmotic pressure and maintain physiological pH.

- Antibiotics and antimycotics: Additional use of antibiotics (e.g., penicillin-streptomycin) and antimycotics (e.g., amphotericin B) helps prevent microbial contamination and ensures the sterility of culture media.

3.1.3. Bioactive substrates for CEC in vitro culture

- Extracellular Matrix (ECM) coatings: ECM proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin are commonly used to coat culture surfaces. These proteins facilitate cell adhesion by interacting with specific integrin receptors on CECs, promoting cell spreading and survival [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82].

- Synthetic polymers: Synthetic polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) can be modified to mimic ECM properties and enhance cell-substrate interactions. These materials offer tunable physical and chemical properties for tailored cell culture applications [75,76,77,78,79].

- Nano-topography and surface modification: Surface roughness and topographical features can be engineered at the nanoscale to guide cell behavior. Nanostructured surfaces promote cell adhesion, alignment, and differentiation by influencing cytoskeletal organization and intracellular signaling pathways [77].

3.1.3. Mechanical and biophysical stimulation for CEC in vitro culture

- Fluid shear stress: Mimicking aqueous humor flow in the eye, fluid shear stress can be applied to CECs using perfusion bioreactors. This mechanical stimulation promotes cell alignment, elongation, and proliferation by activating mechanosensitive pathways.

- Substrate stiffness: The stiffness of the culture substrate can influence CEC behavior. Soft substrates resembling the native corneal tissue elasticity promote cell spreading and maintain endothelial phenotype, while stiffer substrates can induce cell differentiation.

- Mechanical stretch: Controlled mechanical stretching of cell monolayers can enhance CEC proliferation and extracellular matrix production. Stretch-induced mechano-transduction pathways regulate gene expression and cellular responses.

- Micropatterning and topographical cues: Nanoscale or microscale surface patterns can guide CEC alignment and morphology. Substrate micropatterning influences cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion dynamics, impacting cell adhesion and function.

3.1.4. Cell reprogramming and expansion in cell culture in vitro

- Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): iPSC technology involves reprogramming somatic cells, such as skin fibroblasts or peripheral blood cells, into a pluripotent state using defined factors (e.g., Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc). These iPSCs can then be differentiated into CEC-like cells through stepwise induction protocols [90,91,92].

- Direct cell conversion (Transdifferentiation): Transdifferentiation strategies aim to directly convert one cell type into another without passing through a pluripotent state. For example, fibroblasts or other cell types can be directly reprogrammed into CEC-like cells using specific transcription factors or small molecules [93,94,95,96].

- Culturing reprogrammed or transdifferentiated CECs in specialized media containing growth factors, hormones, and extracellular matrix components that mimic the native corneal microenvironment.

- Comprehensive characterization of expanded CECs to ensure the preservation of endothelial phenotype, morphology, and functional properties essential for corneal transparency and pump function.

3.2. Tissue engineering of grafts for DMEK

3.2.1. Decellularized natural membranes as grafts for DMEK

- Decellularization agents: A combination of detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, sodium dodecyl sulfate) and enzymatic treatments (e.g., trypsin, DNase) is used to remove cellular components from DM while minimizing damage to the extracellular matrix (ECM).

- Perfusion and dynamic systems: Perfusing decellularization agents through the DM using dynamic systems (e.g., bioreactors, flow chambers) enhances agent penetration and distribution, improving efficiency and uniformity of decellularization.

- Optimization of parameters: Parameters such as temperature, pH, and duration of decellularization process must be optimized to achieve maximal cell removal while preserving ECM structure and biomechanical properties.

- Biophysical methods: Mechanical agitation or ultrasound-assisted techniques can aid in cell removal and enhance decellularization efficiency without compromising the integrity of DM.

3.2.2. Synthetic biopolymer membranes as grafts for DMEK

3.2.2. Bio-active additives to promote DM regeneration

- Growth factors to trigger cellular pathways between CECs: Growth factors function basically by binding to specific cell-surface receptors with high-affinity to initiate the activation of signaling paths. Moreover, the combination, concentration, dose, formulation, and release time of signaling molecules are significant parameters for achieving successful healing of CE. In different studies, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF2), epidermal growth factor (EGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) were observed to promote the proliferation of CECs directly or indirectly. Also, some of GFs accelerate the role of each other, for instance insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) can contribute to the EGF function on the proliferation of CECs [123,124,125].

- Cytokines to prevent inflammation in CE: Previous studies demonstrated that some DMEK cases trigger immune responses in the host cornea after transplantation, and it may eventually result in graft failure. Although there is not much research on specific inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines involved in CE defects, immune response is related to the increased concentrations of some inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-8) and recruited macrophages (like MCP-3) after DMEK surgery. Therefore, to inhibit inflammatory cytokines and prevent inflammation on defective CE, anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) can be applied to biofabricated scaffolds as signaling molecules [126,127].

- Other anti-inflammatory or bioactive compounds to enhance wound healing: In addition to anti-inflammatory cytokines, anti-inflammatory eye drops containing mydriatics, nonsteroidal and steroidal compounds were used for the treatment of CE. And their protective effect with the decline in inflammation and increase in CEC activity was seen via many times daily use. Nevertheless, eye drops are not the useful delivery system for ocular drugs because the need of prolonged and frequent use and the high amount of drug loss during application on site. Especially for corneal endothelial diseases, eye drops are not very effective so that active compounds in eye drops are not able to reach to the posterior part of the eye. To lower the use of eye drops, these compounds can be incorporated into or onto biofabricated scaffold structures and controlled drug release can be maintained in certain time [128,129].

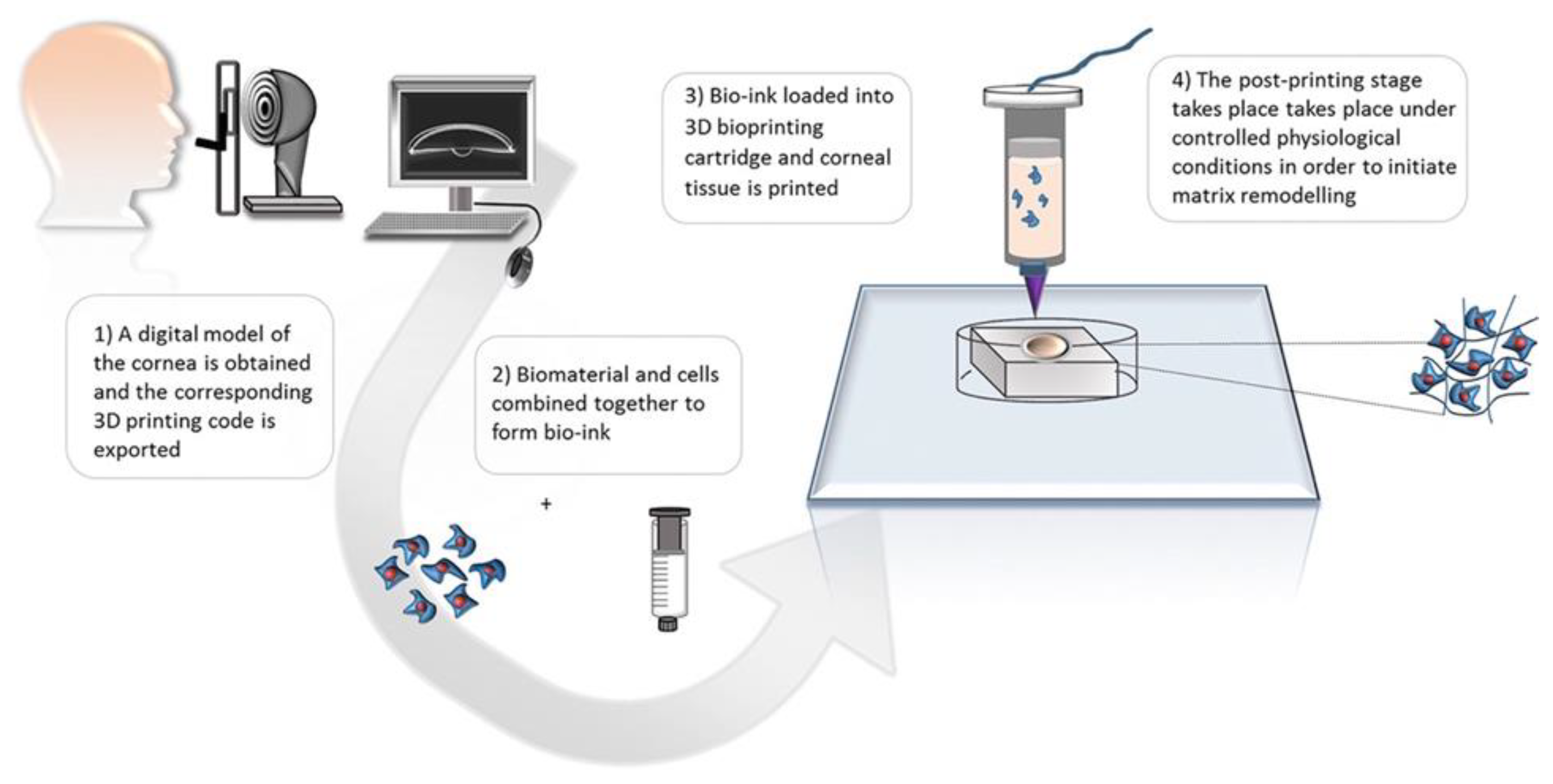

3.2.3. Biofabrication of in the context of DM grafting

3.3. Improving DMEK graft quality through dynamic storage techniques

- Continuous medium flow: The typical media used during OC and HS are Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) with 2-8% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Optisol-GS, respectively. However, corneal grafts stored under these conditions lack regular exposure to fresh medium. In OC, medium change occurs infrequently, either never or every 1-2 weeks [142]. Dynamic cultivation in flow bioreactors ensures continuous medium renewal, enhancing nutrient transport and metabolic waste removal compared to static storage methods. Additionally, separate media circuits allow for the application of epithelium- and endothelium-specific media tailored to increase CEC viability, such as serum-free media [141,143].

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pascolini, D.; Mariotti, S. P. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 96, 614-618. [CrossRef]

- Thuret, G.; Courrier, E.; Poinard, S.; Gain, P.; Baud'Huin, M.; Martinache, I.; Cursiefen, C.; Maier, P.; Hjortdal, J.; Ibanez, J. S.; Ponzin, D.; Ferrari, S.; Jones, G.; Griffoni, C.; Rooney, P.; Bennett, K.; Armitage, W. J.; Figueiredo, F.; Nuijts, R.; Dickman, M. One threat, different answers: the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cornea donation and donor selection across Europe. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 312-318. [CrossRef]

- Ong Tone, S.; Kocaba, V.; Böhm, M.; Wylegala, A.; White, T.L.; Jurkunas, U.V. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: The vicious cycle of Fuchs pathogenesis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021, 80, 100863. [CrossRef]

- Krachmer, J.H.; Purcell, J.J.Jr; Young, C.W.; Bucher, K.D. Corneal endothelial dystrophy. A study of 64 families. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill.: 1960) 1978, 96, 2036–2039. [CrossRef]

- Vedana, G.; Villarreal, G. Jr; Jun, A.S. Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 321–330. DOI: 10.2147/OPTH.S83467.

- Weiss JS, Rapuano CJ, Seitz B, Busin M, Kivelä TT, Bouheraoua N, Bredrup C, Nischal KK, Chawla H, Borderie V, Kenyon KR, Kim EK, Møller HU, Munier FL, Berger T, Lisch W. IC3D Classification of Corneal Dystrophies-Edition 3. Cornea. 2024 Apr 1;43(4):466-527. [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, M.; Hu, J.; Kallay, L.; Eberhart, C.G.; Cursiefen, C.; Qian, J.; Lackner, E.M.; Jun, A.S. Endothelial cell microRNA expression in human late-onset Fuchs' dystrophy. Investigat. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2014, 55, 216–225. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.13-12689.

- Khuc, E.; Bainer, R.; Wolf, M.; Clay, S.M.; Weisenberger, J.K.; Weaver, V.M.; Hwang, D.G.; Chan M.F. Comprehensive characterization of DNA methylation changes in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0175112. [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Zheng, S.; Wolf, M.; Hwang, D.G.; Rose-Nussbaumer, J.R.; Jurkunas, U.V.; Chan M.F. Aberrant DNA methylation of miRNAs in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 16385. [CrossRef]

- Zwingelberg, S.B.; Lautwein, B.; Baar, T.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Brandenstein, M.; Nobacht, S.; Matthei, M.; Cursiefen, C.; Bachmann, B.O. Smoking, Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity as risk factors for the degree of Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.C.K.; Pang, C.P.; Leung, A.T.S.; Chua, J.K.H.; Fan, D.S.P.; Lam, D.S.C. The association between cigarette smoking and ocular diseases. Hong Kong Med. J. 2000, 6, 195–202. PMID: 10895144.

- Galor, A.; Lee, D.J.; Effects of smoking on ocular health. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2011, 22, 477–482. [CrossRef]

- Lois, N.; Abdelkader, E.; Reglitz, K.; Garden, C.; Ayres, J.G. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and eye disease. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 1304–1310.. [CrossRef]

- Nita, M.; Grzybowski, A. Smoking and eye pathologies. A systemic review. Part I. Anterior eye segment pathologies. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2017, 23, 629–638. [CrossRef]

- Solberg, Y.; Rosner, M.; Belkin, M. The association between cigarette smoking and ocular diseases. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1998, 42, 535–547. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; He, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Shi, X.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Lee, S.Y. Smoking and risk of age-related cataract: a meta-analysis. Investigat. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2012, 53, 3885–3895. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Igo, R.P.Jr; Fondran, J.; Mootha, V.V.; Oliva, M.; Hammersmith, K.; Sugar, A.; Lass, J.H.; Iyengar, S.K.; Fuchs’ Genetics Multi-Center Study Group. Association of smoking and other risk factors with Fuchs' endothelial corneal dystrophy severity and corneal thickness. Investigat. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2013, 54, 5829–5835. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.I.; Bourne, W.M.; Pach, J.M.; Brubaker, R.F. Structure and function of the corneal endothelium in diabetes mellitus type I and type II. Archives of ophthalmology. 1996, 114, 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, R.O.; Matsuda, M.; Yee, R.W.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Schultz, K.J. Corneal endothelial changes in type I and type II diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1984, 98, 401–410. [CrossRef]

- Lass, J.H.; Spurney, R.V.; Dutt, R.M.; Anderson, H.; Kochar, H.; Rodman, H.M.; Stern, R.C.; Doershuk, C.F. A morphologic and fluorophotometric analysis of the corneal endothelium in type I diabetes mellitus and cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1985, 100, 783–788. [CrossRef]

- Folli, F.; Corradi, D.; Fanti, P.; Davalli, A.; Paez, A.; Giaccari, A.; Perego, C.; Muscogiuri, G. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus micro- and macrovascular complications: avenues for a mechanistic-based therapeutic approach. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2011, 7, 313–324. [CrossRef]

- Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M. Diabetes and mitochondrial function: role of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 212, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, B.; Ziaei, A.; Fuchsluger, T.; Schmedt, T.; Chen, Y.; Jurkunas, U.V. p53- regulated increase in oxidative-stress–induced apoptosis in Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy: a native tissue model. Investigat. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 2011, 52, 9291–9297. DOI: 10.1167/iovs.11-8312.

- Jurkunas, U.V.; Bitar, M.S.; Funaki, T.; Azizi, B. Evidence of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 2278–2289. [CrossRef]

- Tangvarasittichai, O.; Tangvarasittichai, S. Oxidative stress, ocular disease and diabetes retinopathy. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des 2018, 24, 4726–4741. [CrossRef]

- Zoega, G.M.; Fujisawa, A.; Sasaki, H.; Kubota, A.; Sasaki, K.; Kitagawa, K.; Jonasson, F. Prevalence and risk factors for cornea guttata in the Reykjavik Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006, 113, 565–569. [CrossRef]

- Afshari, N.A.; Pittard, A.B.; Siddiqui, A.; Klintworth G.K. Clinical study of Fuchs corneal endothelial dystrophy leading to penetrating keratoplasty: a 30-year experience. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill.: 1960) 2006, 124, 777–780. [CrossRef]

- Minear, M.A.; Li, Y.J.; Rimmler, J.; Balajonda, E.; Watson, S.; Allingham, R.R.; Hauser, M.A.; Klintworth, G.K.; Afshari, N.A.; Gregory, S.G. Genetic screen of African Americans with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Mol Vis 2013,19, 2508–2516. PMID: 24348007.

- Zwingelberg, S.B.; Büscher, F.; Schrittenlocher, S.; Rokohl, A.C.; Loreck, N.; Wawer-Matos, P.; Fassin, A.; Schaub, F.; Roters, S. Matthei, M.; Heindl, L.M.; Bachmann, B.; Cursiefen, C. Long-Term Outcome of Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty in Eyes With Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy Versus Pseudophakic Bullous Keratopathy. Cornea. 2022, 41, 304-309. [CrossRef]

- Hamill, C.E.; Schmedt, T.; Jurkunas U. Fuchs endothelial cornea dystrophy: a review of the genetics behind disease development. Semin Ophthalmol 2013, 28, 281–286. DOI: 10.3109/08820538.2013.825283.

- Hribek; A.; Clahsen, T.; Horstman, J.; Siebelmann, S.; Loreck, N.; Heindl, L.M.; Bachmann, B.O.; Cursiefen, C.; Matthaei, M. Fibrillar Layer as a Marker for Areas of Pronounced Corneal Endothelial Cell Loss in Advanced Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021, 222, 292-301. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Cho, K.; Srikumaran, D. Fuchs Dystrophy and Cataract: Diagnosis, Evaluation and Treatment. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023, 12, 691-704. [CrossRef]

- Storp, J.J.; Lahme, L.; Al-Nawaiseh, S.; Eter, N.; Alnawaiseh, M. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK) Reduces the Corneal Epithelial Thickness in Fuchs' Patients. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 3573. [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld-van Beek, E.A.; Vasanthananthan, K.; Lie, J.T.; Melles, G.; Wees, J.V.; Oellerich, S.; Kocaba V. 32 Corneal guttae after descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2022, 7 (Suppl 2), 13-14. [CrossRef]

- Cursiefen, C.; Kruse, F.E. DMEK: posteriore lamelläre Keratoplastiktechnik [DMEK: Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty]. Ophthalmologe. 2010, 107, 370-376. [CrossRef]

- Hos, D.; Matthaei, M.; Bock, F.; Maruyama, K.; Notara, M.; Clahsen, T.; Hou, Y.; Hung Le, V.N.; Salabarria, A.C.; Horstmann, J.; Bachmann, B.O.; Cursiefen, C. Immune reactions after modern lamellar (DALK, DSAEK, DMEK) versus conventional penetrating corneal transplantation. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019, 73, 100768. [CrossRef]

- Augustin, V.A.; Son, H.S.; Yildirim, T.M.; Meis, J.; Łabuz, G.; Auffarth, G.U.; Khoramnia, R. Refractive outcomes after DMEK: meta-analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2023, 49, 982-987. [CrossRef]

- Price, M.O.; Gupta, P.; Lass, J.; Price F.W.Jr. EK (DLEK, DSEK, DMEK): New Frontier in Cornea Surgery. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2017, 3, 69-90. [CrossRef]

- Romano, V.; Passaro, M.L.; Bachmann, B.; Baydoun, L.; Ni Dhubhghaill, S.; Dickman, M.; Levis, H.J.; Parekh, M.; Rodriguez-Calvo-De-Mora, M.; Costagliola, C.; Virgili, G.; Semeraro F. Combined or sequential DMEK in cases of cataract and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024, 102, e22-e30. [CrossRef]

- Agha, B.; Ahmad, N.; Dawson, D.G.; Kohnen, T.; Schmack, I. Refractive outcome and tomographic changes after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty in pseudophakic eyes with Fuchs' endothelial dystrophy. Int Ophthalmol. 2021, 41, 2897-2904. [CrossRef]

- Moshirfar, M.; Thomson, A.C.; Ronquillo, Y. Corneal Endothelial Transplantation. StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, USA; 2024, PMID: 32965936.

- Seitz, B.; Daas, L.; Flockerzi, E.; Suffo, S. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty DMEK - Donor and recipient step by step. Ophthalmologe. 2020, 117, 811-828. [CrossRef]

- Schrittenlocher, S.; Matthaei, M.; Bachmann, B.; Cursiefen, C. The Cologne-Mecklenburg-Vorpommern DMEK Donor Study (COMEDOS) - design and review of the influence of donor characteristics on Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) outcome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 2417-2426. [CrossRef]

- Schrittenlocher, S.; Weliwitage, J.; Matthaei, M.; Bachmann, B.; Cursiefen, C. Influence of Donor Factors on Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK) Graft Preparation Outcome. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024, 18, 793-797. [CrossRef]

- Siebelmann, S.; Janetzko, M.; König, P.; Scholz, P.; Matthaei, M.; Händel, A.; Cursiefen, C.; Bachmann, B. Flushing Versus Pushing Technique for Graft Implantation in Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2020, 39, 605-608. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, M.; Romano, D.; Wongvisavavit, R.; Coco, G.; Giannaccare, G.; Ferrari, S.; Rocha-de-Lossada, C.; Levis, H.J.; Semeraro, F.; Calvo-de-Mora, M.R.; Scorcia, V.; Romano, V. DMEK graft: One size does not fit all. Acta Ophthalmol. 2023, 101, e14-e25. [CrossRef]

- Okumura, N.; Koizumi, N. Regeneration of the Corneal Endothelium. Curr Eye Res. 2020, 45, 303-312. [CrossRef]

- Tausif, H.N.; Johnson, L.; Titus, M.; Mavin, K.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Woodward, M.A.; Shtein, R.M.; Mian, S.I. Corneal donor tissue preparation for Descemet's membrane endothelial keratoplasty. J Vis Exp. 2014, 17, 51919. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.P.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Lamellar keratoplasty techniques. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018, 66, 1239-1250. [CrossRef]

- Miron, A.; Sajet, A.; Groeneveld-van Beek, E.A.; Kok, J.S.; Dedeci, M.; de Jong, M.; Amo-Addae, V.; Melles, G.R.J.; Oellerich, S.; van der Wees, J. Endothelial Cell Viability after DMEK Graft Preparation. Curr Eye Res. 2021, 46, 1621-1630. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Schrittenlocher, S.; Siebelmann, S.; Le, V.N.H.; Matthaei, M.; Franklin, J.; Bachmann, B.; Cursiefen, C. Risk factors for endothelial cell loss after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 11086. [CrossRef]

- Godinho, J.V.; Mian, S.I. Update on Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019, 30, 271-274. [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudlou P.; Sood G.; Akhondi H. Cornea Transplantation. StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, USA, 2022 PMID: 30969512.

- Sun, Y.; Peng, R.; Hong, J. Preparation, preservation, and morphological evaluation of the donor graft for descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty: an experimental study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014, 127, 1902-1906. PMID: 24824253.

- Matthaei, M.; Bachmann, B.; Siebelmann, S.; Cursiefen, C. Technique of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK): Video article. Ophthalmologe. 2018, 115, 778-784. [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.; Asadi, M.; Kahroba, H.; Soleyman, M.R.; Andre, H.; Alizadeh, E. Corneal endothelium tissue engineering: An evolution of signaling molecules, cells, and scaffolds toward 3D bioprinting and cell sheets. J Cell Physiol. 2020, 236, 3275-3303. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, M.; Ferrari, S.; Sheridan, C.; Kaye, S.; Ahmad, S. Concise Review: An Update on the Culture of Human Corneal Endothelial Cells for Transplantation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016, 5, 258-264. [CrossRef]

- Ignacio, T.S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Sarayba, M.A.; Sweet, P.M.; Piovanetti, O.; Chuck, R.S.; Behrens, A. A technique to harvest Descemet's membrane with viable endothelial cells for selective transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005, 139, 325-30. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, N.C.; Zhu, C.C. Human corneal endothelial cell proliferation: potential for use in regenerative medicine. Cornea. 2004, 23 (8 Suppl), 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Mimura T.; Yamagami, S.; Yokoo, S.; Usui, T.; Amano S. Selective isolation of young cells from human corneal endothelium by the sphere-forming assay. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010, 16, 803-12. [CrossRef]

- Campos Muñoz A. Artificial cornea, cell culture and tissue engineering. An R Acad Nac Med (Madr) 2005, 122, 619-626; discussion 626-628. Spanish. PMID: 16776319.

- Senoo, T.; Joyce, N.C. Cell cycle kinetics in corneal endothelium from old and young donors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000, 41, 660-667. PMID: 10711678.

- McGlumphy, E.J.; Margo, J.A.; Haidara, M.; Brown, C.H.; Hoover, C.K.; Munir, W.M. Predictive Value of Corneal Donor Demographics on Endothelial Cell Density. Cornea 2018, 37, 1159-1162. [CrossRef]

- Miyata, K.; Drake, J.; Osakabe, Y.; Hosokawa, Y.; Hwang, D.; Soya, K.; Oshika, T.; Amano, S. Effect of donor age on morphologic variation of cultured human corneal endothelial cells. Cornea. 2001, 20, 59-63. [CrossRef]

- Gain, P.; Jullienne, R.; He, Z.; Aldossary, M.; Acquart, S.; Cognasse, F.; Thuret, G. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 167-173. [CrossRef]

- Hyldahl, L. Control of cell proliferation in the human embryonic cornea: an autoradiographic analysis of the effect of growth factors on DNA synthesis in endothelial and stromal cells in organ culture and after explantation in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1986, 83, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Barisani-Asenbauer, T.; Kaminski, S.; Schuster, E.; Dietrich, A.; Biowski, R.; Lukas, J.; Gosch-Baumgartner, I. Impact of growth factors on morphometric corneal endothelial cell parameters and cell density in culture-preserved human corneas. Cornea. 1997, 16, 537-540. PMID: 9294685.

- Aouimeur, I.; Sagnial, T.; Coulomb, L.; Maurin, C.; Thomas, J.; Forestier, P.; Ninotta, S.; Perrache, C.; Forest, F.; Gain, P.; Thuret, G.; He, Z. Investigating the Role of TGF-β Signaling Pathways in Human Corneal Endothelial Cell Primary Culture. Cells. 2023, 12, 1624. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Alonso, S.; Vázquez, N.; Chacón, M.; Caballero-Sánchez, N.; Del Olmo-Aguado, S.; Suárez; C.; Alfonso-Bartolozzi, B.; Fernández-Vega-Cueto, L.; Nagy, L.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Meana, A. An effective method for culturing functional human corneal endothelial cells using a xenogeneic free culture medium. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 19492. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.T.; Lee, J.G.; Na, M.; Kay, E.P. FGF-2 induced by interleukin-1 beta through the action of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates endothelial mesenchymal transformation in corneal endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279, 32325-32332. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, M.; Ferrari, S.; Sheridan, C.; Kaye, S.; Ahmad, S. Concise Review: An Update on the Culture of Human Corneal Endothelial Cells for Transplantation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016, 5, 258-264. [CrossRef]

- Ng, X.Y.; Peh, G.S.L.; Yam, G.H.; Tay, H.G.; Mehta, J.S. Corneal Endothelial-like Cells Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Cell Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 12433. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chen, J.Z.; Shao, C.Y.; Li, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Lu, W.J.; Fu, Y.; Gu, P.; Fan, X. Treatment with retinoic acid and lens epithelial cell-conditioned medium in vitro directed the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells towards corneal endothelial cell-like cells. Exp Ther Med. 2015, 9, 351-360. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.J.; Ma, D.H.; Ma, K.S.; Wang, T.K.; Chou, C.H.; Lin, C.C.; Huang, M.C.; Luo, L.J.; Lai, J.Y.; Chen, H.C. Extracellular Matrix Protein Coating of Processed Fish Scales Improves Human Corneal Endothelial Cell Adhesion and Proliferation. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2019, 8, 27. [CrossRef]

- Soh, W.W.M.; Zhu, J.; Song, X.; Jain, D.; Yim, E.K.F.; Li, J. Detachment of bovine corneal endothelial cell sheets by cooling-induced surface hydration of poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate]-based thermoresponsive copolymer coating. J Mater Chem B. 2022, 10, 8407-8418. [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.; Muhammad, R.; Peh, G.S.; Mehta, J.S.; Yim, E.K. Micro- and nanotopography with extracellular matrix coating modulate human corneal endothelial cell behavior. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1975-1984. [CrossRef]

- Mohay, J.; Lange, T.M.; Soltau, J.B.; Wood, T.O.; McLaughlin, B.J. Transplantation of corneal endothelial cells using a cell carrier device. Cornea. 1994, 13, 173-182. [CrossRef]

- Kassumeh, S.A.; Wertheimer, C.M.; von Studnitz, A.; Hillenmayer, A.; Priglinger, C.; Wolf, A.; Mayer, W.J.; Teupser, D.; Holdt, L.M.; Priglinger, S.G.; Eibl-Lindner, K.H. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) Acid as a Slow-Release Drug-Carrying Matrix for Methotrexate Coated onto Intraocular Lenses to Conquer Posterior Capsule Opacification. Curr Eye Res. 2018, 43, 702-708. [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, M.; Gramm, S.; Götze, T.; Valtink, M.; Drichel, J.; Voit, B.; Engelmann, K.; Werner, C. Thermo-responsive poly(NiPAAm-co-DEGMA) substrates for gentle harvest of human corneal endothelial cell sheets. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007, 80, 1003-1010. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Lace, R.; Carserides, C.; Gallagher, A.G.; Wellings, D.A.; Williams, R.L.; Levis, H.J. Poly-ε-lysine based hydrogels as synthetic substrates for the expansion of corneal endothelial cells for transplantation. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2019, 30, 102. [CrossRef]

- Kimoto, M.; Shima, N.; Yamaguchi, M.; Hiraoka, Y.; Amano, S.; Yamagami, S. Development of a bioengineered corneal endothelial cell sheet to fit the corneal curvature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014, 55, 2337-2343. [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.; Amaral, N.; Taiyab, A.; Sheardown, H. Delivery of Cells to the Cornea Using Synthetic Biomaterials. Cornea. 2022, 41, 1325-1336. [CrossRef]

- D'hondt, C.; Himpens, B.; Bultynck G. Mechanical stimulation-induced calcium wave propagation in cell monolayers: the example of bovine corneal endothelial cells. J Vis Exp. 2013, 16, e50443. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.; Srinivas, S.P.; Van Driessche, W.; Vereecke, J.; Himpens, B. ATP release through connexin hemichannels in corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005, 46, 1208-1218. [CrossRef]

- Rae, J.L.; Watsky; M.A. Ionic channels in corneal endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1996, 270, 975-989. [CrossRef]

- Weant, J.; Eveleth, D.D.; Subramaniam, A.; Jenkins-Eveleth, J.; Blaber, M.; Li, L.; Ornitz, D.M.; Alimardanov, A.; Broadt, T.; Dong, H.; Vyas, V.; Yang, X.; Bradshaw, R.A. Regenerative responses of rabbit corneal endothelial cells to stimulation by fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) derivatives, TTHX1001 and TTHX1114. Growth Factors. 2021, 39, 14-27. [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Mei, Y.; Xu, D.; Huang, G. The Response of Corneal Endothelial Cells to Shear Stress in an In Vitro Flow Model. J Ophthalmol. 2021, 27, 2021:9217866. [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, J.; Utheim, T.P.; Rajasekhar, V.K.; Shahdadfar, A. Substrates for Expansion of Corneal Endothelial Cells towards Bioengineering of Human Corneal Endothelium. J Funct Biomater. 2015, 6, 917-945. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Tighe, S.; Liu, Y.; Hu, M. Engineering of Human Corneal Endothelial Cells In Vitro. Int J Med Sci. 2019, 16, 507-512. [CrossRef]

- Ng, X.Y.; Peh, G.S.L.; Yam, G.H.; Tay, H.G.; Mehta, J.S. Corneal Endothelial-like Cells Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Cell Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 12433. [CrossRef]

- So, S.; Park, Y.; Kang, S.S.; Han, J.; Sunwoo, J.H.; Lee, W.; Kim, J.; Ye, E.A.; Kim, J.Y.; Tchah, H.; Kang, E.; Lee, H. Therapeutic Potency of Induced Pluripotent Stem-Cell-Derived Corneal Endothelial-like Cells for Corneal Endothelial Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 24, 701. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, Z.; Duan, H. iPSC-Derived Corneal Endothelial Cells. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2023, 281, 257-276. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, B.M.; Salero, E.; Núñez-Toldrà, R.; Sabater, A.L.; Gil, F.J.; Perez, R.A. Discovering the Potential of Dental Pulp Stem Cells for Corneal Endothelial Cell Production: A Proof of Concept. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 617724. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Ramirez, G.I.; Valdez-Cordoba, C.M.; Islas-Cisneros, J.F.; Trevino, V. Computational approaches for predicting key transcription factors in targeted cell reprogramming (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2018, 18, 1225-1237. [CrossRef]

- Gruenert, A.K.; Czugala, M.; Mueller, C.; Schmeer, M.; Schleef, M.; Kruse, F.E.; Fuchsluger, T.A. Self-Complementary Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors Improve Transduction Efficiency of Corneal Endothelial Cells. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0152589. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.H.; Zhao, N.; Feng, X.; Jie, Y.; Jin, Z.B. Conversion of mouse embryonic fibroblasts into neural crest cells and functional corneal endothelia by defined small molecules. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabg5749. [CrossRef]

- Uehara, H.; Zhang, X.; Pereira, F.; Narendran, S.; Choi, S.; Bhuvanagiri, S.; Liu, J.; Ravi Kumar, S.; Bohner, A.; Carroll, L.; Archer, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Gao, G.; Ambati, J.; Jun, A.S.; Ambati, B.K. Start codon disruption with CRISPR/Cas9 prevents murine Fuchs' endothelial corneal dystrophy. Elife. 2021, 8, e55637. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Li, S.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Zou, Z.; Lin, M.; Chen, X.; Zhao, G.; McAlinden, C.; Lei, H.; Zhou, X.; Huang, J. Genome Editing VEGFA Prevents Corneal Neovascularization In Vivo. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024, 6, e2401710. [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S.; Koizumi, N.; Ueno, M.; Okumura, N.; Imai, K.; Tanaka, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Inatomi, T.; Bush, J.; Toda, M.; Hagiya, M.; Yokota, I.; Teramukai, S.; Sotozono, C.; Hamuro, J. Injection of Cultured Cells with a ROCK Inhibitor for Bullous Keratopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 995-1003. [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.; Asadi, M.; Kahroba, H.; Soleyman, M.R.; Andre, H.; Alizadeh, E. Corneal endothelium tissue engineering: An evolution of signaling molecules, cells, and scaffolds toward 3D bioprinting and cell sheets. J Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 3275–3303. PMID: 33090510.

- Suamte, L.; Tirkey, A.; Barman, J.; Babu, P.J. Various manufacturing methods and ideal properties of scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Smart Materials in Manufacturing 2023, 1, e100011. DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.smmf.2022.100011.

- Tayebi, T.; Baradaran-Rafii A.; Hajifathali, A.; Rahimpour, A.; Zali, H.; Shaabani, A.; Niknejad, H. Biofabrication of chitosan/chitosan nanoparticles/polycaprolactone transparent membrane for corneal endothelial tissue engineering. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 7060. [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Yuan, B.; Xie, Z.; Hong, J. The Innovative Biomaterials and Technologies for Developing Corneal Endothelium Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: A Review and Prospect. Bioengineering (Basel). 2023, 10, 1284. [CrossRef]

- Petrela, R.B.; Patel, S.P. The soil and the seed: The relationship between Descemet's membrane and the corneal endothelium. Exp Eye Res. 2023, 227, e109376. [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Fernández-Pérez, J.; Masterton, S.; Madden, P. W.; Bhattacharjee, P. Designing Scaffolds for Corneal Regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908996. DOI: doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201908996.

- Du, L.; Wu, X. Development and characterization of a full-thickness acellular porcine cornea matrix for tissue engineering. Artif Organs. 2011, 35, 691-705. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, J.; Ahearne, M. The impact of decellularization methods on extracellular matrix derived hydrogels. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 14933. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Sidney, L.E.; Dunphy, S.E.; Dua, H.S.; Hopkinson, A. Corneal Decellularization: A Method of Recycling Unsuitable Donor Tissue for Clinical Translation? Curr Eye Res. 2016, 41, 769-782. [CrossRef]

- Alio del Barrio, J.L.; Chiesa, M.; Garagorri, N.; Garcia-Urquia, N.; Fernandez-Delgado, J.; Bataille, L.; Rodriguez, A.; Arnalich-Montiel, F.; Zarnowski, T.; Álvarez de Toledo, J.P.; Alio, J.L.; De Miguel, M.P. Acellular human corneal matrix sheets seeded with human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells integrate functionally in an experimental animal model. Exp Eye Res. 2015, 132, 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, F.; Hu, X.; Li, H.; Liu, T.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, W. Rapid porcine corneal decellularization through the use of sodium N-lauroyl glutamate and supernuclease. J Tissue Eng. 2019, 10, e2041731419875876. [CrossRef]

- Dua, H.S., Maharajan, V.S., Hopkinson, A. Controversies and Limitations of Amniotic Membrane in Ophthalmic Surgery. Cornea and External Eye Disease, Rhainhard, T.; Larkin, D.F.P.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006, Essentials in Ophthalmology, 21-33. DOI: doi.org/10.1007/3-540-31226-9_2.

- Wilson, S.L.; Sidney, L.E.; Dunphy, S.E.; Rose, J.B.; Hopkinson, A. Keeping an eye on decellularized corneas: a review of methods, characterization and applications. J Funct Biomater. 2013, 4, 114-161. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; He, X.; Zhao, H.; Ma, J.; Tao, J.; Zhao, S.; Yan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, S. Research Progress of Polymer Biomaterials as Scaffolds for Corneal Endothelium Tissue Engineering. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2023, 13, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, A.; Triunfo, M.; Scieuzo, C.; Ianniciello, D.; Tafi, E.; Hahn, T.; Zibek, S.; Salvia, R.; De Bonis, A.; Falabella, P. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan from different developmental stages of the bioconverter insect Hermetia illucens. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 8084. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.S.B.; Ponnamma, D.; Choudhary, R.; Sadasivuni, K.K. A Comparative Review of Natural and Synthetic Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1105. [CrossRef]

- Song, E.; Chen, K.M.; Margolis, M.S.; Wungcharoen, T.; Koh, W.G.; Myung, D. Electrospun Nanofiber Membrane for Cultured Corneal Endothelial Cell Transplantation. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 54. [CrossRef]

- Rafat, M.; Li, F.; Fagerholm, P.; Lagali, N.S.; Watsky, M.A.; Munger, R.; Matsuura, T.; Griffith, M. PEG-stabilized carbodiimide crosslinked collagen–chitosan hydrogels for corneal tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3960–3972. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, W.; Han, B., Yang, C.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, W.; Rong, M.; Li, H.; Fabrication and characters of a corneal endothelial cells scaffold based on chitosan. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2011, 22, 175–183. [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, B.; Brown, K.D.; Blencowe, A.; Daniell, M.; Stevens, G.W.; Qiao, G.G. Ultrathin chitosan–poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel films for corneal tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 2013, 9, 6594–6605. [CrossRef]

- Biazar, E., Baradaran-Rafii; A., Heidari-Keshel; S., Tavakolifard, S. Oriented nanofibrous silk as a natural scaffold for ocular epithelial regeneration. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2015, 26, 1139–1151. [CrossRef]

- Stoppato, M.; Stevens, H.Y.; Carletti, E.; Migliaresi, C.; Motta, A.; Guldberg, R.E. Effects of silk fibroin fiber incorporation on mechanical properties, endothelial cell colonization and vascularization of PDLLA scaffolds. Biomaterials 2013, 4, 4573-4581. [CrossRef]

- Forouzideh, N.; Nadri, S.; Fattahi, A.; Abdolahinia, E.D.; Habibizadeh, M.; Rostamizadeh, K.; Baradaran-Rafii, A.; Bakhshandeh, H.; Epigallocatechin gallate loaded electrospun silk fibroin scaffold with anti-angiogenic properties for corneal tissue engineering. J Drug Deliv Technol 2020, 56, 101498. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B.J.; Kwait, P.S.; Tripathi, RC. Corneal growth factors: a new generation of ophthalmic pharmaceuticals. Cornea. 1990, 9, 2-9. PMID: 2404663.

- Yu, W.Y.; Sheridan, C.; Grierson, I.; Mason, S.; Kearns, V.; Lo, A.C.; Wong, D. Progenitors for the corneal endothelium and trabecular meshwork: a potential source for personalized stem cell therapy in corneal endothelial diseases and glaucoma. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 412743. [CrossRef]

- Hoppenreijs, V.P.; Pels, E.; Vrensen, G.F.; Treffers, W.F. Corneal endothelium and growth factors. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996, 41, 155-164. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Takahashi, H.; Inoda, S.; Shimizu, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Kawashima, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yamagami, S. Aqueous humour cytokine profiles after Descemet's membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 17064. [CrossRef]

- Kammrath Betancor, P.; Hildebrand, A.; Böhringer, D.; Emmerich, F.; Schlunck, G.; Reinhard, T.; Lapp, T. Activation of human macrophages by human corneal allogen in vitro. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0194855. [CrossRef]

- Ghiță, A.C.; Ilie, L.; Ghiță, A.M. The effects of inflammation and anti-inflammatory treatment on corneal endothelium in acute anterior uveitis. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2019, 63, 161-165. PMID: 31334395.

- Lynch, C.R.; Kondiah, P.P.D.; Choonara, Y.E.; du Toit, L.C.; Ally, N.; Pillay, V. Hydrogel Biomaterials for Application in Ocular Drug Delivery. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 228. [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, N.; Okumura, N.; Ueno, M.; Kinoshita, S. New therapeutic modality for corneal endothelial disease using Rho-associated kinase inhibitor eye drops. Cornea. 2014, 33 (Suppl 11), 25-31. [CrossRef]

- Okumura, N.; Koizumi, N.; Ueno, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Hirata, K.; Torii, R.; Hamuro, J.; Kinoshita, S. Enhancement of corneal endothelium wound healing by Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) inhibitor eye drops. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011, 95, 1006-1009. [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Bu, Y.; Lau, D.A.; Lin, Z.; Sun, T.; Lu, W.W.; Lu, S.; Ruan, C.; Chan, C.J. Advances in 3D bioprinting technology for functional corneal reconstruction and regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1065460. [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Gagnon, M.; Wu, K.Y. The Third Dimension of Eye Care: A Comprehensive Review of 3D Printing in Ophthalmology. Hardware. 2024, 2, 1-32. DOI: doi.org/10.3390/hardware2010001.

- Isaacson, A.; Swioklo, S.; Connon, C.J. 3D bioprinting of a corneal stroma equivalent. Exp Eye Res. 2018, 173, 188-193. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.H.; Kim, J.C. Ex Vivo Functionality of 3D Bioprinted Corneal Endothelium Engineered with Ribonuclease 5-Overexpressing Human Corneal Endothelial Cells. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018, 7, e1800398. [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, P.; Mörö, A.; Puistola, P.; Hopia, K.; Huuskonen, M.; Viheriälä, T.; Ilmarinen, T.; Skottman, H. Bioprinting of human pluripotent stem cell derived corneal endothelial cells with hydrazone crosslinked hyaluronic acid bioink. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024, 15, 81. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y. Unraveling the mechanobiology of cornea: From bench side to the clinic. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2022, 10, 953590. [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, G.; Ferrari, S.; Romano, V.; Ponzin, D.; Ahmad, S.; Parekh, M. Corneal storage methods: considerations and impact on surgical outcomes. Expert Review of Ophthalmology. 2020, 16, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Kitazawa, K.; Inatomi, T.; Tanioka, H.; Kawasaki, S.; Nakagawa, H.; Hieda, O.; Fukuoka, H.; Okumura, N.; Koizumi, N.; Iliakis, B.; Sotozono, C.; Kinoshita, S. The existence of dead cells in donor corneal endothelium preserved with storage media. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1725–1730. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.; Tarau, I.S.; Rossi, A.; Leonhardt, S.; Schwarz, T.; Schuerlein, S.; Lotz, C.; Hansmann, J. In Vivo-Like Culture Conditions in a Bioreactor Facilitate Improved Tissue Quality in Corneal Storage. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1700344. [CrossRef]

- Garcin, T.; Gauthier, A.S.; Crouzet, E.; Herbepin, P.; He, Z.; Thuret, G.; Gain, P. Corneal Active Storage Machine allows corneal graft delivery for up to 3 months. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 3826.

- Armitage, W.J. Preservation of Human Cornea. Transfus Med Hemother. 2011, 38, 143–147. [CrossRef]

- Valtink, M.; Donath, P.; Engelmann, K.; Knels, L. Effect of different culture media and deswelling agents on survival of human corneal endothelial and epithelial cells in vitro. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology 2016, 254, 285–295. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).