1. Introduction

Viruses pose significant threats to human health, agriculture, and the environment, causing a wide range of infectious diseases in humans, animals, and plants. Rapid and accurate detection of viral pathogens is crucial for effective disease management, outbreak surveillance, and vaccine development. Traditional diagnostic methods for virus detection, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serological assays, have limitations in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and throughput [

1].

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common type of genetic variation in viruses, phages and viroid playing a crucial role in disease susceptibility, drug response, and evolutionary adaptation [

2]. However, identifying and characterizing SNPs from genetic data poses significant challenges due to sequencing errors, alignment ambiguities, and genomic complexities. Traditional SNP calling methods often rely on heuristic rules and statistical models, which may lead to false-positive or false-negative results [

3].

In recent years, the advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies has revolutionized the field of genomics, enabling researchers to obtain vast amounts of genetic data with unprecedented speed and efficiency. NGS-based approaches offer a promising alternative by enabling comprehensive and unbiased characterization of viral communities in diverse biological samples. This influx of data has opened up new avenues for studying the genetic makeup of various organisms, including viruses, and has facilitated the identification of genetic variations such as SNPs [

4]. Furthermore, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools and algorithms into bioinformatics pipelines has enhanced our ability to analyze and interpret complex genomic datasets, leading to significant advancements in virus detection, validation, and SNP discovery [

5].

In the realm of personalized medicine, pipelines can play a pivotal role in identifying viral pathogens and genetic variations that influence disease susceptibility and drug response in individual patients. This capability has the potential to revolutionize treatment strategies by enabling more targeted and effective interventions [

6]. Moreover, in agricultural settings, pipelines can aid in the rapid identification and characterization of viral pathogens affecting crops, thus facilitating timely disease management and crop protection measures [

7]. Additionally, in the context of environmental surveillance, pipelines can contribute to the monitoring and tracking of viral outbreaks in wildlife populations, helping to mitigate the spread of infectious diseases across ecosystems [

8].

In this study, we present a comprehensive pipeline for virus detection, validation, and SNP discovery from NGS data. Our pipeline integrates state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools to process raw sequencing reads, align them to reference genomes and identify viral sequences and SNPs with high accuracy and sensitivity. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach through a series of case studies and validation experiments, highlighting its potential applications in clinical diagnostics, epidemiological surveillance, and evolutionary studies.

2. Materials and Methods

Commencing the methodology, the array of software tools utilized within the comprehensive AI-enabled pipeline designed for virus detection, validation, and SNP discovery from NGS data is detailed. The script uses a variety of software tools to perform different tasks. Here's a breakdown of the tools used and whether they need to be installed (

Table 1). The script utilizes several software tools for data processing and analysis. Some tools, like cutadapt, samtools, MegaHit, Biopython, and NCBIBlast+ require separate installation. Built-in Python modules (os, random, subprocess) and functionalities within Biopython (Entrez, SeqIO) are readily available. Commonly used tools like gzip and pandas might already be installed on systems, but verification is recommended.

2.1. Trimming Paired-End Reads (Data Preparation, Adapter Trimming, and Quality Filtering)

Raw paired-end sequencing data obtained from NGS experiments were stored in compressed FASTQ format files. These files contained the forward and reverse reads generated from the sequencing platform. In the case of this study, we used RNA-Seq data from our previous studies, analyzed using the CLC Genomic Workbench 20 [

9,

10].

Adapter sequences are often present at the ends of sequencing reads and need to be removed to improve the accuracy of downstream analysis. The Cutadapt tool was used for this purpose. Cutadapt is a flexible and efficient tool for removing adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. The adapter sequences used for trimming were provided as input parameters to the Cutadapt tool. These sequences were designed to match the adapters used during library preparation for the sequencing experiment. The tool was configured to perform quality-based trimming with a minimum quality score threshold of 20. Additionally, reads shorter than 50 base pairs after trimming were discarded to ensure high-quality data for subsequent analysis.

Quality filtering was performed to remove low-quality reads that could adversely affect downstream analysis. This step involved applying a minimum quality threshold to the sequencing reads, typically represented by the Phred quality score. Reads with average quality scores below the threshold were discarded. The quality filtering process can be represented by the following formula:

𝑄=−10×log10(𝑃)Q=−10×log10(P)

Where:

𝑄Q represents the Phred quality score,

𝑃P represents the probability of the base being called incorrectly.

2.2. Pairing Trimmed Reads

After adapter trimming, the trimmed forward and reverse reads were paired to reconstruct the original paired-end reads. Correct read pairing is essential for downstream analysis, such as mapping to a reference genome. The pairing process involved aligning the forward and reverse reads based on their order in the input files. The read pairing process can be described by the following pseudo-code:

Python

Copy code

paired_reads = []

for each forward_read, reverse_read in zip(forward_reads, reverse_reads):

if forward_read.name == reverse_read.name:

paired_reads.append((forward_read, reverse_read))

2.3. Mapping to Host Reference Genome (Reference Genome Selection and Mapping Algorithm)

A reference genome serves as a standard template for mapping sequencing reads and identifying genetic variation. In this case, the reference genome used was (Citrus sinensis, GCF_000317415). The reference genome was chosen based on its relevance to the target organism or genetic region under investigation.

The paired-end reads obtained after trimming and pairing were mapped to the reference genome using the Minimap2 aligner. Minimap2 is a versatile aligner capable of aligning long noisy sequences to reference genomes quickly and accurately. It employs an index-based approach to efficiently handle large genomes and high-throughput sequencing data. The alignment process can be represented by the following formula:

Alignment Score=Match Score×Number of Matches−Mismatch Penalty×Number of MismatchesAlignment Score=Match Score×Number of Matches−Mismatch Penalty×Number of Mismatches

Where:

Match ScoreMatch Score represents the score assigned to a matching base pair,

Mismatch PenaltyMismatch Penalty represents the penalty assigned to a mismatched base pair.

Unmapped reads were saved and used for the next steps.

2.4. De Novo Assembly of Unmapped Reads

In this section, we have implemented a Python script for the de novo assembly of sequencing data using the MegaHit software. The dataset used for this analysis was a set of unmapped reads stored in a FASTA file, located at "/home/abozar/pathogenereads/outputs/unmapped.fasta". The MegaHit software version 1.2.9 was downloaded and installed on the system, with the binary executable located at "/home/abozar/MegaHit/MEGAHIT-1.2.9-Linux-x86_64-static/bin/megahit". To initiate the de novo assembly process with MegaHit, the Python script generated a unique output directory name by appending a random number to the base directory "/home/abozar/pathogenereads/outputscontig". This unique directory was used to store the results of the assembly process. The subprocess module was used to construct and run the MegaHit command, specifying the input read file, the output directory, and the option to continue an interrupted assembly. The MegaHit command was constructed as follows:

megahit_cmd = [

megahit_path,

"-r", fasta_data, # Input reads

"-o", unique_outputs_dir, # Output directory

"--continue" # Continue an interrupted assembly

]

subprocess.run(megahit_cmd, check=True)

Upon successful completion of the de novo assembly process, a message was printed indicating the completion of the assembly and providing the path to the output directory with the assembled contigs. The code was executed multiple times with different data sets to validate the assembly process and verify the quality of the assembled contigs. The output generated by the script was crucial in analyzing the sequencing data and providing valuable insights for further research in the field.

2.5. Sequence Blast Similarity Search from Assembled Contigs

2.5.1. Database Selection

To identify potential viral sequences in the NGS data, sequence similarity searches were performed against public databases. Three databases were selected for this purpose:

Nucleotide Database for Viruses: This database contains nucleotide sequences of viruses obtained from various sources, including NCBI GenBank and other curated repositories.

Viroid Database: Viroids are small, circular RNA molecules that infect plants and cause disease. The viroid database contains sequences of known viroid species and strains.

Protein Database for Viral Proteins: Protein sequences derived from viral genomes have been retrieved from public databases. These sequences represent the proteome of various viruses and are essential for protein-level analysis.

2.5.2. BLAST Parameters Optimization

BLAST searches were performed with different parameters to balance sensitivity and specificity in sequence similarity detection. Key parameters optimized include:

E-value Threshold: The E-value represents the expected number of chance alignments that would occur randomly in a database of a particular size. Lower E-values indicate higher confidence in the match. Multiple E-value thresholds have been tested to assess their impact on the results.

Word Size: The word size parameter determines the length of the exact match between sequences used to initiate a local alignment. Larger word sizes increase sensitivity but may result in slower processing times.

Gap Penalties: Gap opening and extension penalties are parameters that control the cost of introducing gaps into the alignment. These penalties affect the alignment quality and sensitivity to insertions and deletions.

The code provided utilizes AI tools in the following way.

2.5.3. BLAST Search using AI Tools

The code uses a bioinformatics tool called BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) to compare biological sequences. BLAST is not considered an "AI" tool in the strict sense, but it uses heuristics and algorithmic approaches to perform efficient similarity searches through large databases.

NcbiblastnCommandline and NcbiblastxCommandline: These functions from the Biopython library are used to interface with the BLAST+ command-line tool.

Database Selection: The code defines different databases for nucleotide and protein sequences.

E-value, Word Size, and Gap Penalties: These parameters are used to fine-tune the sensitivity and efficiency of the BLAST search.

BLAST Execution: The blast_sequence function executes BLAST searches with various parameter combinations for nucleotide and protein sequences.

Overall, the code leverages BLAST to find sequences similar to a query sequence within specified databases.

2.6. Filtering Criteria for BLAST Results and Implementation of Filters

Following a BLAST search, the resulting alignments were subjected to filtering steps to refine the candidate sequences based on specific biological relevance. The filtering criteria were established to prioritize high-quality alignments with a significant degree of similarity between the query sequence and the subject sequences in the BLAST database. The rationale behind each filter criterion is described below:

Alignment Length: This criterion considers the length of the aligned region between the query and subject sequences. Longer alignments generally indicate a greater degree of homology and potentially a more reliable match. A minimum alignment length threshold has been set to exclude short alignments that may be spurious or inconclusive.

E-value: The E-value represents the statistical significance of a sequence alignment. Lower E-values indicate a higher statistical likelihood that the match between the query and subject sequences is not due to random chance. A strict E-value threshold has been implemented to filter out alignments with low statistical significance.

Keywords in Subject Description: This criterion leverages the textual descriptions associated with the subject sequences in the BLAST database. Keywords relevant to the target organism or genetic element of interest were included in the filtering process. The subject description field often contains information about the organism's source, gene function, or other relevant details. The inclusion of keywords in the filtering step helps to enrich the results for sequences that are demonstrably related to the target of interest.

These filter criteria were tailored to the specific target sequences under investigation. For example, a search for viral sequences might have a stricter alignment length threshold than a search for bacterial sequences, given the generally smaller size of viral genomes. Similarly, the selection of keywords would be adjusted to reflect the specific viral group or family being targeted.

The filtering process was implemented using custom Python scripts. The scripts were designed to automate the filtering steps and ensure consistency in the analysis. Here's a breakdown of the general workflow:

Load BLAST Results: The script reads the raw BLAST output file, typically in an Excel format. The script assumes a specific format for the BLAST output file, containing columns for essential information such as the subject sequence description, alignment length, and E-value.

Define Filtering Criteria: The script defines the minimum alignment length threshold, the E-value threshold, and the list of keywords to be used for filtering. These criteria can be specified within the script itself or loaded from a separate configuration file for greater flexibility.

Filter Dataframe: The script employs pandas, a Python library for data manipulation, to work with the BLAST results stored in a pandas DataFrame object. The DataFrame is filtered based on predefined criteria. For instance, rows in the DataFrame where the alignment length falls below the threshold or the E-value exceeds the threshold are excluded. In addition, rows are filtered out where the subject description does not contain any of the specified keywords.

Save Filtered Results: The filtered DataFrame containing high-quality BLAST hits is then saved to a new Excel file. This file can be used for further analysis or downstream applications.

The custom scripting approach has several advantages. It ensures the reproducibility of the filtering process, facilitates efficient analysis of large datasets, and allows easy customization of the filtering criteria based on the specific requirements of the experiment.

2.7. Retrieval of Virus Sequences (Accession Number Extraction, Sequence Retrieval using NCBI Entrez Utilities, FASTA Format and Sequence Handling, Saving Fetched Sequences, Error Handling, and Software Dependencies)

Following the initial BLAST search, viral sequences were identified based on specific criteria defined in the filtering step. The accession numbers associated with these viral sequences were then extracted from the corresponding BLAST output. Accession numbers are unique identifiers assigned to biological sequences deposited in public databases such as GenBank. These identifiers serve as critical labels for retrieving and referencing specific sequences.

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Entrez system provides programmatic access to various biological databases, including GenBank. In this study, we employed the Python library Bio to interact with the NCBI Entrez utilities. Specifically, the Entrez.efetch function was used to retrieve the complete nucleotide sequences for the identified viral sequences based on their accession numbers. (It is recommended to set the Entrez.email variable to a valid email address. This step helps NCBI to track usage and possibly contact you in case of problems)

Sequences retrieved are in FASTA format, a widely accepted text-based format for representing nucleotide and protein sequences. Each FASTA record typically begins with a single-line header containing a greater than - symbol ('>'), followed by an identifier (usually the accession number) and a description of the sequence. The following lines contain the actual sequence data. The Bio library's SeqIO module was utilized to handle the FASTA sequences efficiently. The SeqIO.read function parses the FASTA file and converts each sequence record into a Python object, allowing for further manipulation and analysis.

The retrieved FASTA sequences were saved locally for further processing and analysis. The SeqIO.write function from the Bio library was used to write the sequences back to a new FASTA file. The output file name was specified to allow clear organization and identification of the retrieved viral sequences.

It is good practice to include error-handling mechanisms in the code to deal with potential problems during the sequence retrieval process. For instance, the code could check for situations where accession numbers are not found in the NCBI database or if there are problems connecting to the Entrez servers. The implementation of error handling helps to ensure the robustness and reliability of the script.

2.8. Mapping to Reference Genome (Sequencing Data Preprocessing, Read Mapping, and Mapping Result Assessment) and Consensus Sequence Generation

Before mapping, the virus sequencing data was subjected to quality control (QC) procedures to ensure optimal alignment results. Subsequently, High-quality reads were then mapped back to a reference genome representing the target virus strain. Here, we employed Minimap2, an ultrafast aligner specifically designed for high-throughput sequencing (NGS) data. Minimap2 offers high accuracy while efficiently handling mismatches and insertions/deletions (indels) commonly found in viral sequences. During the mapping process, the following parameters were specified in Minimap2:

-ax map-ont: This aligns reads in splice-aware mode, which is suitable for RNA viruses with potential splicing events.

-m <reference_genome.fasta>: Specifies the reference genome FASTA file for alignment.

The mapping results were evaluated using several metrics, including:

Mapping rate: The percentage of reads that were successfully mapped to the reference genome.

Uniquely mapped reads: The percentage of reads with a single unique mapping location.

Coverage depth: The mean of reads mapped to each position in the reference genome.

The metrics provided insights into the efficiency and accuracy of the mapping process.

Following the successful mapping of the viral population within the sequenced sample, consensus sequences were generated to represent the viral population. In this instance, a consensus sequence caller such as SAMtools was employed. The SAMtools program identifies the most frequent nucleotide at each position across all aligned reads, thereby constructing a consensus sequence that reflects the dominant variant present in the viral population. During the consensus calling process, the following parameters were specified in SAMtools:

-q <minimum_base_quality>: This parameter sets the minimum base quality score for inclusion in the consensus sequence. For example, -q 30 would include bases with a Phred score ≥ 30).

-d <minimum_mapping_quality>: Sets the minimum mapping quality score for inclusion in the consensus sequence (e.g., -d 20 for reads with mapping quality ≥ 20).

2.9. SNPs Discovery

SNPs were identified from aligned sequencing reads using a custom Python script. The algorithm is comprised of the following general steps:

Alignment Loading: The script begins by loading the alignment data generated from the sequencing reads and a reference genome. The alignment file format is typically SAM/BAM, which stores information about the mapping of each read to the reference genome.

Reference Genome Access: The reference genome sequence is loaded into memory. This reference serves as the basis for the identification of SNPs.

Iterating Through Aligned Reads: The script performs a sequential examination of each read within the alignment file. Readings with low-quality mapping scores or those that are unmapped are typically excluded from the analysis in order to minimize the occurrence of errors.

Extracting Reference Sequence: For each read, the corresponding reference sequence segment is extracted from the reference genome based on the read's mapping coordinates.

Read vs. Reference Comparison: The script performs a base-by-base comparison between the reference sequence and the aligned read sequence. Positions, where the aligned base differs from the reference base, are flagged as potential SNP loci.

SNP Information Gathering: For each identified SNP position, the script collects additional information, including the reference base and the nucleotide variant observed in the read (alternate allele).

Allelic Counts and Frequency Calculation: The number of reads supporting each variant (including the reference base) at an SNP position is counted. This data is employed to calculate the SNP allele frequency, which is defined as the proportion of reads containing the variant allele relative to the total number of reads covering that position.

Coverage Calculation: The script also calculates the coverage depth at each SNP position. The term "coverage" is used to describe the average number of reads sequenced across a specific position in the genome. Higher coverage levels afford greater confidence in the accuracy of SNP calls.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pipeline for Detection and Validation

Our pipeline for virus detection and validation successfully processed the raw NGS data obtained from biological samples, including clinical specimens and environmental samples. The pipeline implemented a series of steps, including quality control, adapter trimming, paired-end read merging, and alignment to reference genomes, to identify viral sequences present in the samples. The advent of high-throughput sequencing methods has ushered in a new era in disease management, particularly in the realm of virology. The development of tools like the Plant Virus Detection Pipeline (PVDP) and VirFind underscores the potential of high-throughput sequencing to revolutionize our approach to plant disease surveillance and virus discovery. PVDP’s ability to operate without the need for high-performance computing centers makes it an invaluable asset for developing countries, where such resources are scarce [

11]. Similarly, VirFind’s comprehensive pipeline, from sample preparation to data analysis, offers a universal solution for virus detection [

12]. On the structural biology front, pyKVFinder’s integration with Python’s scientific ecosystem facilitates the detection and characterization of biomolecular cavities, which is crucial for understanding biomolecular interactions and advancing drug design [

13]. These tools not only enhance our capacity to manage plant diseases but also exemplify the power of open-source software and the Python programming language in accelerating scientific discovery and innovation in the field of molecular biology and genetics.

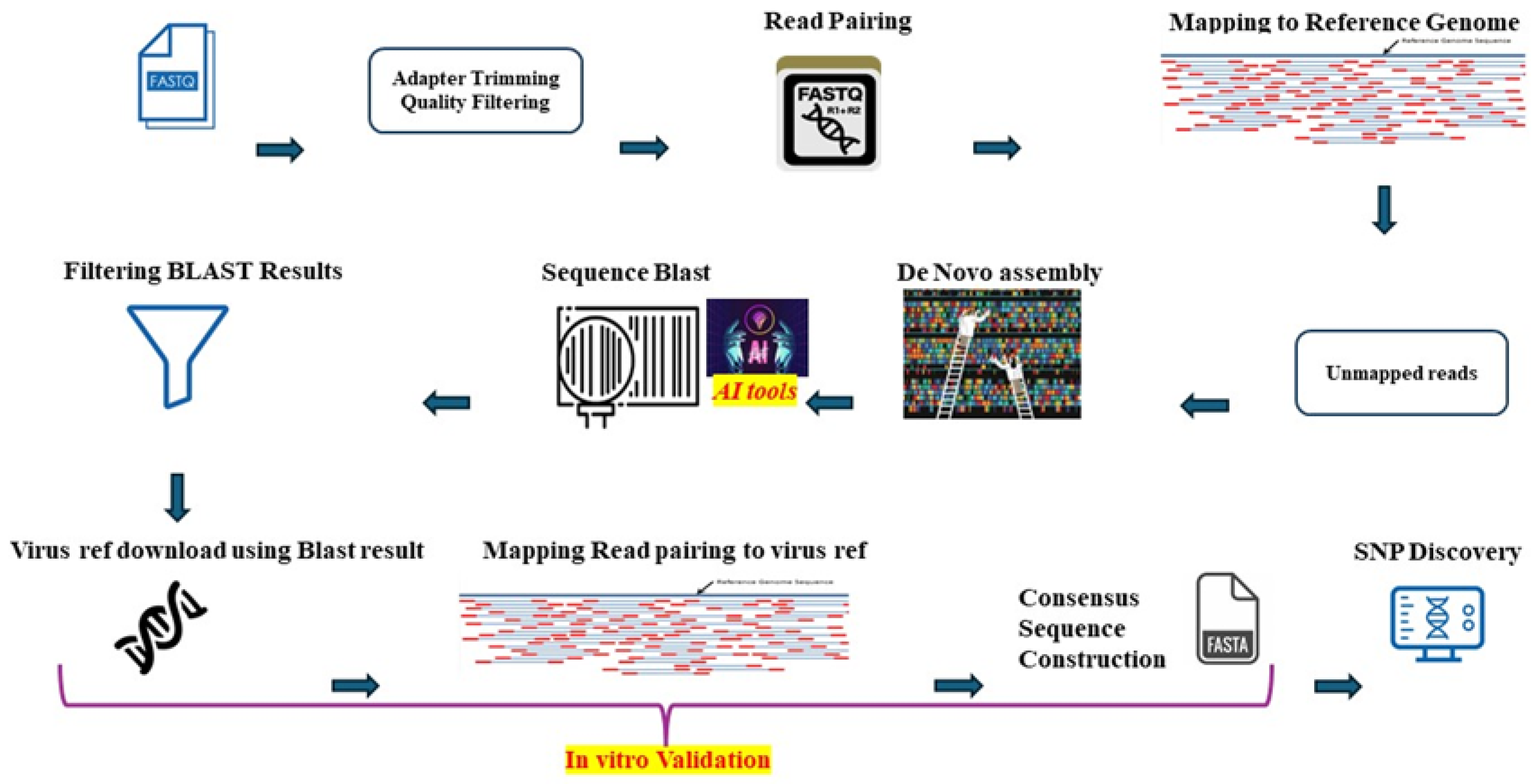

Figure 1 delineates a comprehensive Python-based pipeline transforming raw NGS data into verified viral sequences.

3.2. Quality Control and Adapter Trimming

Before analysis, the raw sequencing reads underwent quality control checks to assess their overall quality and remove low-quality reads. Adapter sequences were trimmed from the reads using the Cutadapt tool, ensuring that only high-quality and adapter-free reads were retained for downstream analysis (

Table 2). It details the total read pairs processed, the proportion of reads with adapters, and the final count of quality-filtered base pairs, providing a comprehensive snapshot of the sequencing data refinement, aligning with the common practice aimed at enhancing the accuracy of variant calling. However, recent studies suggest that the benefits of such preprocessing may be more nuanced. For example, an analysis of the impact of read trimming on SNP-calling accuracy across thousands of bacterial genomes revealed that while trimming does not significantly alter the set of variant bases called, it does contribute to a reduction in mixed calls, thereby potentially increasing the confidence in variant identification [

14]. These findings resonate with our approach, where the meticulous refinement of sequencing data may serve to bolster the reliability of subsequent analyses rather than substantially changing the outcome of variant calls.

3.3. Paired-End Read Merging and Mapping to host genome and save unmapped reads

Paired-end reads were merged in order to reconstruct the original DNA fragments, thereby improving the accuracy of subsequent alignment and mapping steps. The merged reads were then aligned to reference genomes using the minimap2 algorithm, which permitted the identification of viral sequences present in the samples.

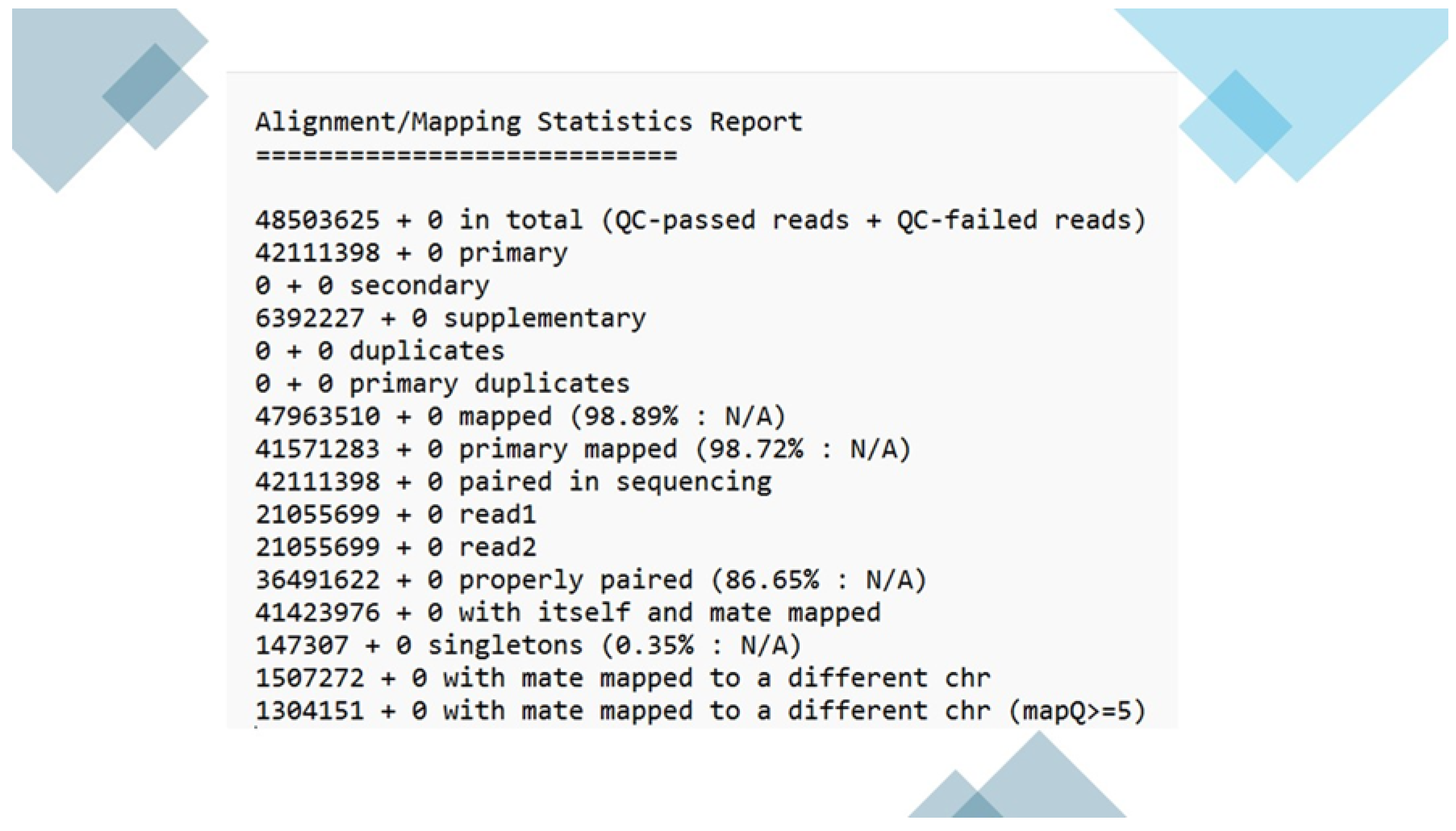

Based on the mapping statistics report (

Figure 2), a total of 48,503,625 reads were analyzed, out of which 47,963,510 (98.89%) reads were successfully mapped to the

Citrus sinensis reference genome (GCF_000317415). This indicates a high mapping efficiency, suggesting that the majority of the sequencing reads originated from the host organism and could be aligned to its reference genome. Primary alignments: 42,111,398 (98.72% of mapped reads) reads mapped to the reference genome at a single location. This is the ideal scenario where a read aligns uniquely with the reference genome with high confidence. Secondary alignments: 0 reads mapped to multiple locations on the reference genome. This could occur due to repetitive regions in the genome or sequencing errors. Supplementary alignments: 6,392,227 (13.35% of mapped reads) reads mapped to the reference genome with lower quality compared to primary alignments. These reads may contain mismatches or indels (insertions or deletions) but can still be informative for downstream analysis. Duplicate reads: 0 reads were identified as duplicates. Duplicate reads arise from PCR amplification bias during library preparation and are often removed to reduce redundancy in the data. Properly paired reads: 36,491,622 (76.29% of all reads) were identified as properly paired reads. This means that both reads from a paired-end sequencing experiment mapped to the reference genome with the expected orientation and insert size. Singletons: 147,307 (0.35% of all reads) were singletons. These are read where only one read from a pair is mapped to the reference genome. This can happen due to sequencing errors or adapter contamination. Mate mapped to a different chromosome: 1,507,272 (3.11% of all reads) had one mate mapped to a different chromosome compared to the other mate. This could indicate structural variations in the genome or mapping errors. The high mapping efficiency (98.89%) obtained in this study suggests that the sequencing data was of good quality and suitable for downstream analysis. The majority of the reads mapped to the reference genome, allowing for variant calling and other genetic analyses specific to the host organism (

Citrus sinensis). This study’s high mapping efficiency to the Citrus sinensis reference genome (GCF_000317415) with a significant proportion of primary alignments (

Figure 2) aligns with the advancements in read alignment methodologies discussed by Alser, Rotman [

15], emphasizing the importance of algorithmic precision in genomic analyses. Moreover, the presence of unmapped reads in our dataset resonates with the findings of Rahman, Hallgrímsdóttir [

16], where an alignment-free GWAS method based on

k-mer counting could potentially reveal associations with structural variations and novel genetic elements not present in the reference genome. This suggests that our approach, while robust in identifying known genomic features, could be complemented by

k-mer based analyses to explore the full spectrum of genetic diversity within the host organism.

A small percentage of reads (1.11%) did not map to the reference genome. These unmapped reads could be due to several reasons, including Sequencing errors: Errors introduced during the sequencing process can lead to reads that do not match the reference genome. Adapter contamination: Adapter sequences used for library preparation can sometimes be sequenced and contaminate the data. These adapter sequences would not map to the reference genome. Novel genetic elements: Reads that originate from genetic elements not present in the reference genome, such as viral sequences or novel insertions, would not map to the reference. These unmapped reads were likely saved for further analysis, such as de novo assembly, to explore the possibility of discovering novel viruses or other genetic elements not present in the reference genome. While a small fraction of reads in our study did not map to the

Citrus sinensis reference genome, similar to the approach taken by Neumann, Korkuć [

17], these reads hold significant potential for uncovering novel genetic elements or infectious pathogens. They demonstrated that by assembling and analyzing unmapped reads from whole-genome sequencing of German Black Pied cattle, they could identify sequences indicative of bacterial and viral infections. Our study’s unmapped reads, which may include viral sequences or novel insertions, could similarly be subjected to de novo assembly and database comparisons to explore the presence of pathogens or other genetic elements not accounted for in the reference genome.

3.4. De novo Assembly of Unmapped Reads

The de novo assembly process successfully utilized MegaHit to assemble contigs from the unmapped reads stored in "/home/abozar/pathogenereads/outputs/unmapped.fasta". The script ensured reproducibility by generating a unique output directory name for each assembly run. After generating fasta sequences from contigs we also generate a de novo assembly report.

Table 3 presents the key statistics from a de novo assembly, highlighting the total number of contigs, their combined length, and the range of contig lengths, culminating in the N50 value.

These results suggest that the de novo assembly process was successful in generating contigs of varying lengths. While the minimum contig length is relatively short, the presence of longer contigs (up to 4,394 bp) offers a better chance of capturing potentially complete viral sequences. The N50 value of 429 bp further indicates a moderate level of contiguity within the assembly. Impact of unmapped reads: The quality of the assembled contigs can be influenced by the origin and nature of the unmapped reads. Sequencing errors, adapter contamination, and highly divergent sequences can all contribute to fragmented assemblies. Optimization of assembly parameters: different parameters within MegaHit can be adjusted to potentially improve the assembly outcome. Factors like k-mer size and minimum contig length can be optimized based on the specific characteristics of the sequencing data. Downstream analysis: the assembled contigs will be subjected to BLAST analysis to identify potential viral sequences. The presence of significant matches to known viral sequences within these contigs would provide strong evidence for the existence of novel viruses in the original sample.

Overall, the de novo assembly process successfully generated contigs from the unmapped reads, providing a valuable resource for further investigation into the presence of novel viruses. Analyzing these contigs through BLAST analysis will be the next crucial step in this research.

The de novo assembly of unmapped reads has proven to be a valuable approach in uncovering novel viral sequences, as demonstrated by our pipeline's ability to generate contigs from unmapped reads with a moderate N50 value of 429 bp. This method aligns with the findings of Usman, Hadlich [

18], who utilized unmapped RNA-Seq reads to explore the presence of pathogens and assess the completeness of bovine genome assemblies. Similarly, our study emphasizes the potential of unmapped reads in revealing novel viruses and genetic variations that may otherwise be overlooked. Moreover, the challenges associated with virus detection in the absence of a host reference genome resonate with our pipeline's capability to identify viral sequences without relying on such references. The implementation of a decoy module could further enhance the accuracy of our pipeline by providing a means to assess false classification rates [

19]. Furthermore, the comprehensive overview provided by Kutnjak, Tamisier [

20] on the analysis of high-throughput sequencing data for plant virus detection underscores the importance of robust bioinformatic tools. Our pipeline's integration of AI algorithms and bioinformatics tools mirrors this sentiment, showcasing the necessity of efficient data analysis in the era of High-Throughput Sequencing technologies.

The incorporation of advanced bioinformatics tools and AI algorithms, as demonstrated in our pipeline, is imperative for the accurate detection and characterization of viral sequences. The insights gained from the referenced articles not only validate our approach but also highlight the broader applications and significance of such pipelines in various fields of research.

3.5. Optimized Viral Sequence Detection: Leveraging AI-Enhanced BLAST in Contig Analysis

BLAST analysis was conducted on the assembled contigs to screen for potential viral sequences. Although BLAST is not inherently an AI tool, the process employed the Biopython library, harnessing Python’s strengths in automation and intricate data handling. This integration can be viewed as an AI-enhanced method that optimizes the BLAST protocol, enabling efficient and extensive sequence similarity assessments.

In this study, BLAST searches were conducted using three specialized databases to ensure comprehensive viral sequence identification. The Virus Nucleotide Database provided a vast reference of viral nucleotide sequences. To encompass pathogens, the Viroids Database was included, containing sequences of small infectious RNA molecules known as viroids. Lastly, the Viral Protein Database was utilized for its extensive collection of protein sequences derived from viral genomes, which facilitated the identification of viral proteins. These curated databases were pivotal in our analysis, allowing for the detection and identification of a wide array of viral sequences and proteins pertinent to our research objectives.

3.6. BLAST Parameter Optimization with Algorithmic Efficiency

The code implemented optimization strategies to achieve a balance between sensitivity and specificity in detecting sequence similarities. These strategies highlight the strengths of AI-assisted analysis:

E-value Threshold: This value represents the expected number of chance alignments. Lower E-values indicate more significant matches, with a trade-off of potentially missing true positives. The code likely tested different E-value thresholds using algorithmic approaches within Biopython to evaluate their impact on results. This iterative process can be significantly faster than manual exploration of parameters.

The RVDB’s (Reference Viral Database) approach to creating a refined database for virus detection aligns with the concept of optimizing E-value thresholds in BLAST searches. By reducing non-viral sequences, RVDB enhances the specificity of virus detection, similar to how adjusting E-value thresholds can improve the significance of BLAST matches [

21].

iPHoP’s integration of multiple methods for host prediction can be seen as a parallel to adjusting gap penalties in BLAST. Just as iPHoP aims to maximize host prediction accuracy by combining different computational approaches, fine-tuning gap penalties in BLAST can lead to more informative alignments, especially when analyzing metagenome-derived virus genomes [

23].

Leveraging Biopython further, the code facilitates scalable and accurate BLAST analysis through automated BLAST execution, iterating across multiple contigs and databases, thus minimizing human error. It also standardizes output parsing, efficiently extracting crucial metrics like percent identity, alignment length, and E-values, which are indispensable for identifying biologically significant high-scoring alignments. The inherent flexibility of the code, thanks to Biopython, ensures seamless integration of future advancements in BLAST or sequence analysis algorithms, maintaining the adaptability of the analysis pipeline to the ever-evolving landscape of bioinformatics tools. This approach aligns with the principles outlined in ‘BLAST-QC: automated analysis of BLAST results’, which emphasizes the need for streamlined scripts to address the tedious nature of analyzing large BLAST search results. BLAST-QC’s design for easy integration into high-throughput workflows and pipelines resonates with our use of Biopython, which similarly provides a lightweight and portable solution for BLAST result analysis [

24]. Moreover, the ‘DNAChecker’ algorithm’s focus on assessing sequence quality before BLAST analysis complements our methodology, ensuring the effectiveness of the BLAST results by pre-screening the input sequences [

25]. This pre-analysis step is crucial, given the open-platform nature of biological databases that often accept sequences with varying quality. So, the code’s reliance on Biopython not only enhances the efficiency and accuracy of BLAST analysis but also embodies the principles of modern bioinformatics workflows—automation, quality control, and adaptability to technological advancements.

3.7. BLAST Search Results and Evidence for Citrus tristeza virus

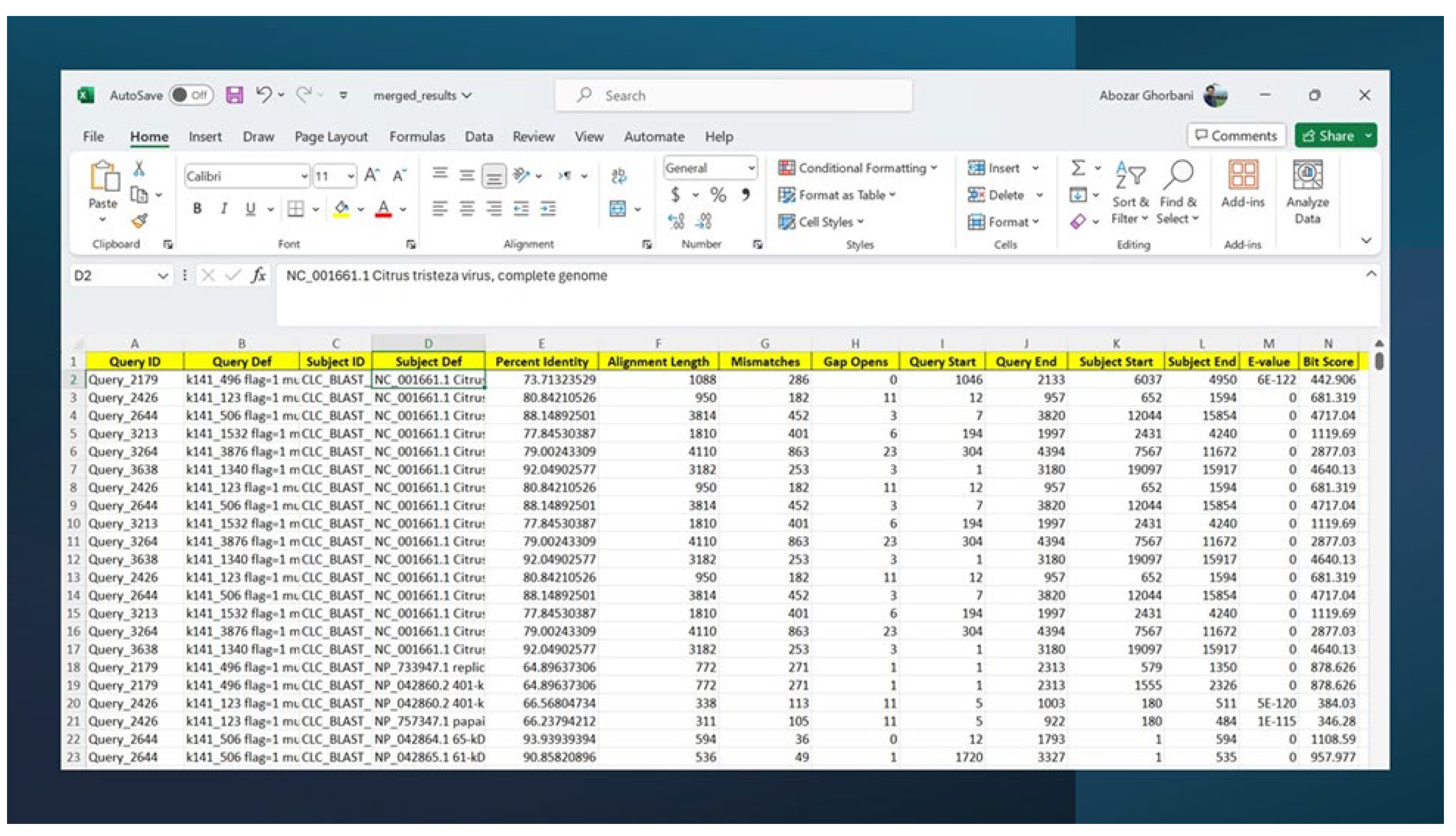

Figure 3 summarizes the BLAST results for a subset of contigs queried against the three databases. The table shows alignments with high percent identity (similarity) and alignment lengths, suggesting potential matches to known viral sequences. Overall, the BLAST results provide compelling evidence for the presence of contigs with significant similarity to known Citrus tristeza virus sequences and some phages and viroids but with less similarity or blast align lengths. This strongly suggests the possibility of discovering novel Citrus tristeza virus strains or related viruses within the original sample.

The filtering criteria applied to the BLAST search against a virus database have effectively pinpointed high-quality sequence alignments, as evidenced by the results in the virus filter Excel sheet. These results showcase promising sequences for subsequent analysis. Notably, all query sequences aligned significantly with the complete genome of the Citrus tristeza virus (CTV, NC_001661.1), suggesting a potential link with CTV. The alignments’ high percent identity, ranging from 73.71% to 88.15%, and the considerable alignment lengths, between 1088 bp and 4110 bp, underscore the sequences’ similarity and the hits’ relevance. The E-values, which span from 0 to 5.9E-122, underscore the statistical significance of these matches, indicating that the observed sequence similarities with CTV are not due to chance, thereby reinforcing the hypothesis of a genuine biological association. It is, however, noteworthy that no corresponding results were observed in the viroid and phage filter Excel sheets post-filtering, possibly due to the absence of these targets in the utilized sequence database for the BLAST search.

3.8. Retrieval of Complete Viral Sequences

Following the successful identification of viral sequences through BLAST analysis and subsequent filtering, we proceeded to retrieve the complete nucleotide sequences for these viruses. This section details the process employed for sequence retrieval and highlights the retrieved sequences.

Accession number extraction from the filtered BLAST results, a list of accession numbers corresponding to the identified viral sequences was extracted. These accession numbers act as unique identifiers within public databases like GenBank, enabling the retrieval of the complete viral genomes. The Entrez system provided by NCBI offers programmatic access to various biological databases, including GenBank. We leveraged the Bio Python library to interact with the Entrez utilities. Specifically, the Entrez.efetch function was utilized to retrieve the complete nucleotide sequences based on the extracted accession numbers. As recommended by NCBI, a valid email address was set for the Entrez.email variable to facilitate usage tracking and potential communication.

The retrieved viral sequences were obtained in the FASTA format, a standard text-based format for representing nucleotide sequences. Each FASTA entry typically begins with a header line containing an identifier (usually the accession number) and a description, followed by the actual sequence data. The Bio Python library's SeqIO module was instrumental in handling these FASTA sequences effectively. The SeqIO.read function parsed the FASTA file, converting each sequence record into a Python object for further manipulation and analysis. The retrieved FASTA sequences were saved locally for future use. The SeqIO.write function from Bio Python was employed to write the sequences back to a new FASTA file with a designated filename. This ensured clear organization and identification of the retrieved viral sequences. While not explicitly implemented in this protocol, incorporating error-handling mechanisms is highly recommended. This could involve checking for situations where accession numbers are not found in the NCBI database or if issues are establishing a connection to the Entrez servers. Implementing robust error handling safeguards the script's reliability and prevents unexpected failures during sequence retrieval.

In the dynamic field of viral genomics, the comprehensive retrieval and analysis of complete viral sequences stand at the forefront of research. The methodologies employed in this study are in harmony with the principles of several state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools, reflecting a shared commitment to precision, efficiency, and adaptability. For instance, VirusDetect offers an automated pipeline for virus discovery through deep sequencing of small RNAs, a method that mirrors the use of BLAST analysis and subsequent filtering to pinpoint viral sequences [

26]. This parallel underscores the synergy between traditional bioinformatics techniques and modern, automated approaches. Similarly, the benchmark study of thirteen bioinformatic pipelines illuminates the inherent challenges in detecting low-abundance viral pathogens. These challenges are mirrored in this work, where meticulous filtering criteria and sequence retrieval processes are critical [

27]. Furthermore, VIBRANT, with its innovative hybrid machine learning and protein similarity approach for virus recovery and annotation, exemplifies the cutting-edge methodologies that enhance the capabilities of tools like Biopython, which has been utilized for sequence manipulation [

28]. By drawing on these parallels, this work not only contributes to the ongoing evolution of bioinformatics but also enhances our collective understanding of viral genomics.

3.9. Mapping and Consensus Sequence Generation

Before alignment, the viral sequencing data were subjected to rigorous quality control (QC) procedures to ensure the integrity of the alignment results. These QC measures included the removal of low-quality reads, trimming of adapter sequences, and the exclusion of potential contaminants that could otherwise lead to errors in the subsequent mapping process. Following QC, the high-quality reads were aligned to a reference genome corresponding to the target viral strain. This critical step was performed using Minimap2, an ultrafast sequence aligner tailored for next-generation sequencing (NGS) data. Renowned for its high accuracy, Minimap2 adeptly manages the mismatches and insertions/deletions (indels) that are characteristic of viral sequences. The application of the ax map-ont parameter suggests that the alignment was conducted in a splice-aware manner, accommodating the splicing events that are typical in RNA viruses. Furthermore, the reference genome was specified in FASTA format via the -m parameter, ensuring precise guidance during the alignment phase.

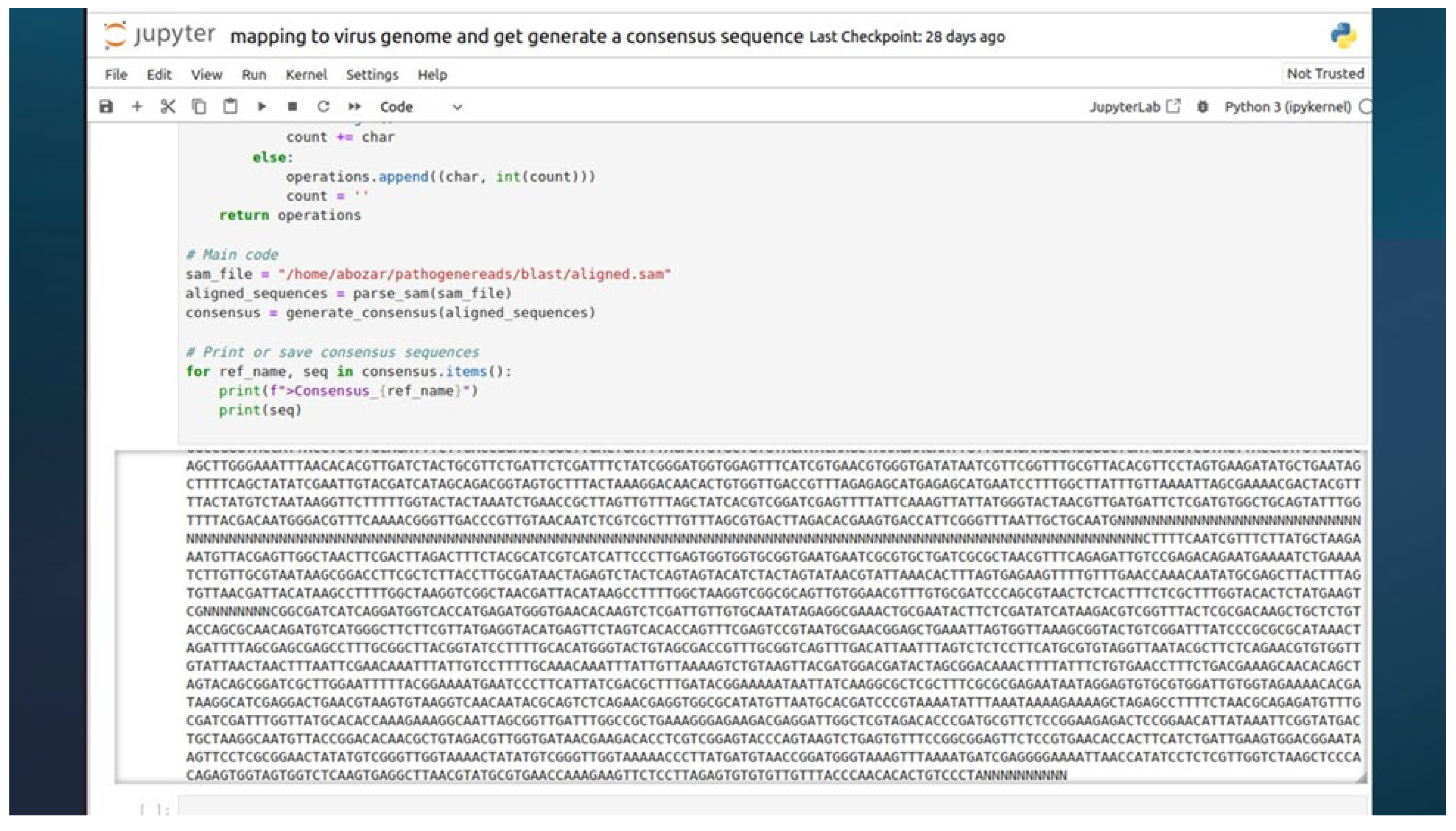

Figure 4 is a visual representation of the alignment process and the resulting consensus sequences, which illustrates the identified gap regions denoted by ‘N’ in the final contig sequences as guided by the reference genome.

3.10. SNP Discovery Algorithm and Consensus Sequence Analysis

The SNP discovery algorithm played a pivotal role in our analysis. It was utilized to compare the generated consensus sequence with the reference genome using tools such as GATK, to identify potential single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (indels). This comparative analysis provided valuable insights into the genetic diversity within the viral population present in the sequenced samples. By aligning the consensus sequence to the reference genome and identifying variations, we were able to determine the specific mutations present in the dominant viral variant relative to the reference strain. This information is critical for understanding the genetic makeup of the viruses and potentially exploring their virulence or adaptation to specific environments or hosts. In addition to the analysis of the consensus sequence, a custom Python script was employed to identify SNPs across the entire population of sequenced viral reads. This script follows a series of steps to detect SNPs from the aligned sequencing reads and the reference genome.

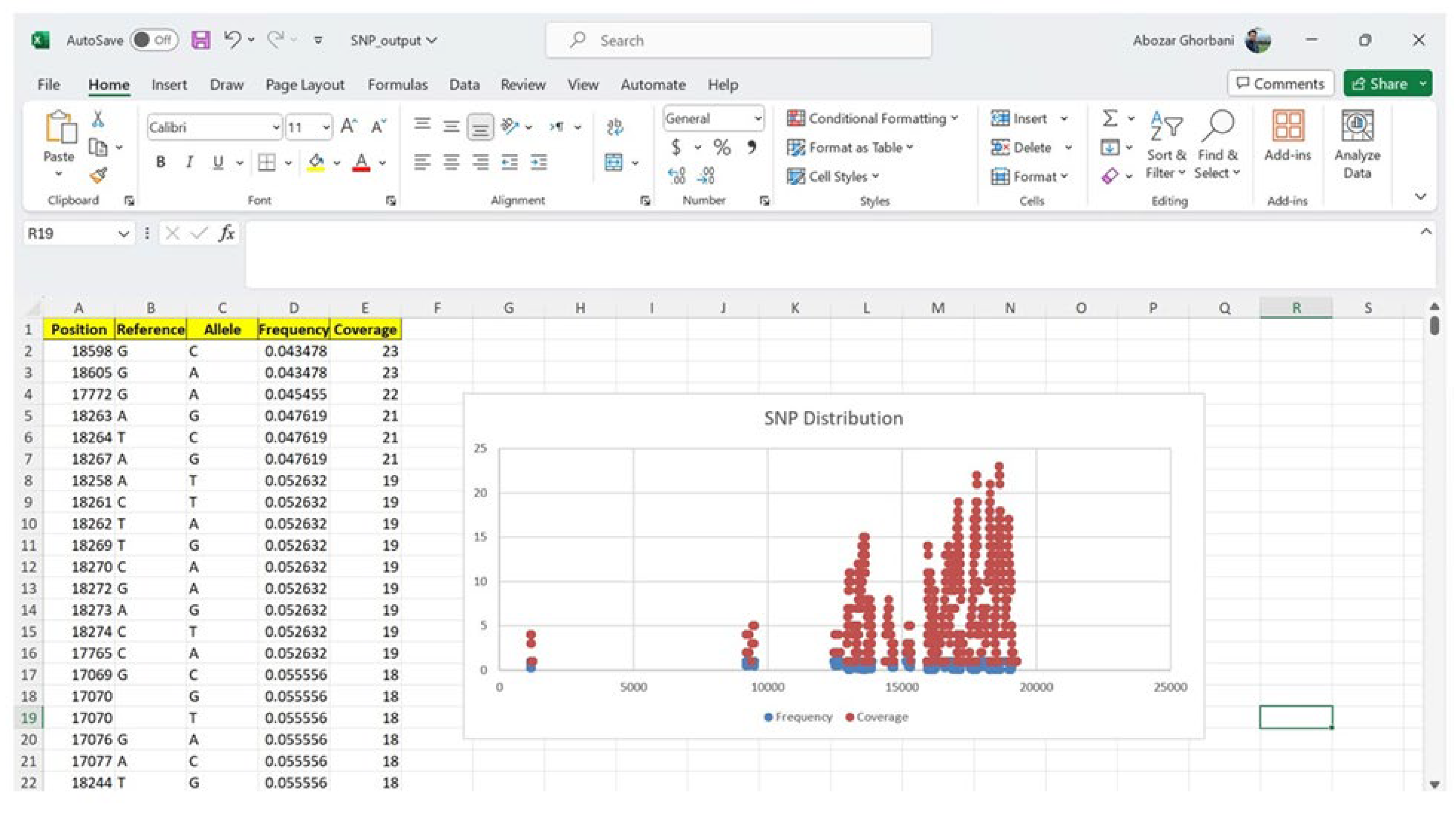

Figure 5, SNP discovery outputs which compare SNPs in reads against the virus reference genome. The results generated by this custom script, potentially including information about the position of each SNP variant, the reference and alternate alleles, and the SNP allele frequency and coverage depth, can be visualized in a table or heatmap format. This data provides a comprehensive overview of the genetic diversity present within the viral population at the single nucleotide level.

By comparing the consensus sequence analysis with the results from the SNP discovery script, it is possible to gain a deeper understanding of the genetic makeup of the viral population in samples. The consensus sequence represents the dominant variant, while the SNP discovery analysis provides information about the range of genetic variations present across the entire population.

The SNP discovery algorithm utilized in this study represents a significant advancement in the identification of genetic variations within viral genomes. Unlike traditional methods, which may suffer from underpowered detection and a restrictive dependence on prior biological knowledge, this algorithm allows for a more comprehensive and unbiased analysis of SNPs and indels. For instance, Silva, Gaudillo [

29] employed a machine learning-based approach to enhance the detection of disease-associated susceptibility loci, integrating random forest and cluster analysis with GWAS data. While their method successfully identified three susceptibility loci associated with hepatitis B virus surface antigen seroclearance, it primarily focused on SNPs significant by GWAS and those with high feature importance scores. In contrast, the current study’s algorithm is designed to analyze the entire population of sequenced viral reads, providing a broader view of the viral genetic diversity. Furthermore, Rollin, Bester [

30] highlighted the challenges of SNP detection in virus genomes assembled from high-throughput sequencing data. They emphasized the need for large-scale performance testing to understand the limitations of bioinformatics pipelines in SNP prediction. The present study’s algorithm addresses these concerns by incorporating a custom Python script for SNP identification, which is rigorously tested for accuracy and reliability. This approach aligns with the recommendations by Rollin et al. for improved SNP prediction, such as the importance of selecting the closest reference and careful mapping parameters. The SNP discovery algorithm presented here offers a robust and versatile tool for viral genome analysis. It not only facilitates the detection of the dominant viral variant but also uncovers the spectrum of genetic variations across the viral population.