1. Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) following posterior spinal fusion (PSF) for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is one of the most frequently reported complications, ranging in incidence from 1%-4% [

1]. The most common causative agents for SSI in the AIS population are skin flora such as

Staphylococcus aureus and

Staphylococcus epidermidis [

2]. A recent study of 21 patients undergoing PSF, in which cultures were taken from the surgical site at various stages of the surgical procedure, describes a pattern of residual skin flora spreading to deeper parts of the wound in the course of the surgical procedure [

3]. It showed a higher rate of positive cultures from deep within the surgical bed prior to wound closure than immediately following surgical exposure or routine preoperative skin preparation. Overall, 62% of the patients had positive cultures, 90% of which were caused by

C. acnes. All cultures were sensitive to cefazolin and vancomycin.

Cefazolin is often used for prophylaxis because of its efficacy against skin flora and common gram-negative bacteria. It is bacteriostatic at low concentrations and bactericidal at higher concentrations. The efficacy of cefazolin depends on its dosing scheme as well as tissue penetrance. Specifically, it is suggested that the dosing should achieve antibiotic concentrations above the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the targeted bacteria for 90% to 100% of the dosing interval [

4,

5,

6]. Based on the idea that the MIC describes the bacteriostatic effect of cefazolin and the finding that the antibacterial effect of cefazolin increases further for concentrations up to 4 to 5 times MIC [

7]; some even recommend higher concentrations of up to fourfold above MIC. There is, however, limited evidence to guide cefazolin dosing that achieves bactericidal tissue concentrations during the operative phase of care. Recommended individual cefazolin doses range from 1 to 2 g or 30 mg/kg and recommended re-dosing intervals range from 2 to 4 hours. Posterior spinal fusion procedures present the additional challenge of fluctuations in drug concentration independent of the dosing scheme due to potentially large volume blood loss, fluid shifts, and significant volume resuscitation.

In this randomized, controlled, prospective pharmacokinetic (PK) pilot study, we measured plasma cefazolin concentrations and used a clinical microdialysis technique to measure skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue concentrations of cefazolin given by either intermittent bolus or continuous infusion in patients undergoing PSF for AIS. We also calculated the duration of target attainment for unbound cefazolin concentrations at target sites for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and gram-negative organisms in these 2 patient groups. We hypothesized that continuous infusion dosing would achieve better target attainment and better coverage for anticipated organisms than intermittent bolus dosing.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (IRB201701129) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03190668). All subjects gave written consent before randomization. A CONSORT diagram is provided in the Supplementary Material (

Figure S3).

2.1. Patient Selection and Data Collection

All patients undergoing PSF for AIS at the University of Florida were screened on a rolling basis. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of idiopathic scoliosis with planned fusion of at least 6 vertebral levels and age between 12 to 20 years. Candidates were excluded for known allergy to cefazolin, known renal or hepatic insufficiency or failure, abnormalities that precluded insertion of microdialysis catheters into paraspinal muscles, or American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status 3 or higher. Data collected from patients included age, sex, height, body mass index, baseline renal function, intraoperative urine output, blood loss, albumin level, amount of intravenous albumin received during surgery, total allogeneic and autologous transfusion amounts, total intraoperative dose of cefazolin, and any other co-medications received during surgery.

2.2. Anesthesia Management

Our institution has adopted a standardized clinical pathway for patients undergoing PSF for AIS [

8]. The basic anesthetic technique consists of a total intravenous anesthetic utilizing propofol and remifentanil infusions to facilitate neuromonitoring, administration of tranexamic acid as a bolus dose followed by an infusion, and single dose of methadone prior to incision. The attending anesthesiologist directs all aspects of the intraoperative anesthetic, including adherence to the protocol, intraoperative fluid management, and need for transfusion.

2.3. Study Protocol

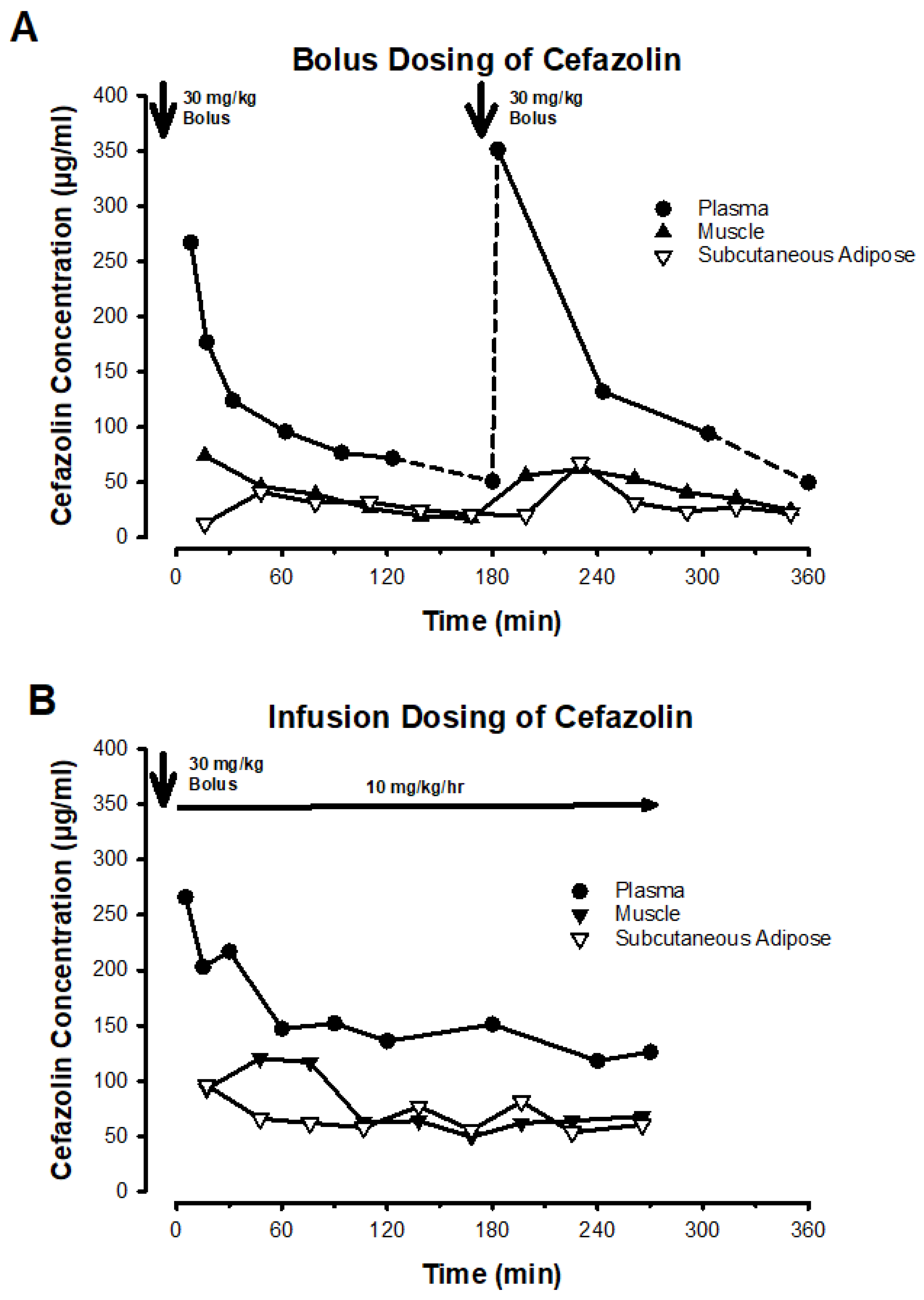

Patients underwent simple randomization to one of 2 antibiotic dosing regimens: intermittent bolus or continuous infusion. Subjects randomized to bolus dosing were given 30 mg/kg cefazolin IV prior to surgical incision and repeated every 3 hours for the duration of the operation, reflecting current institutional practice. Subjects randomized to continuous infusion were administered the same initial bolus dose of 30 mg/kg before incision, followed by a continuous infusion of 10 mg/kg per hour until the end of surgery.

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

Plasma samples were obtained from an arterial catheter in both groups. Samples were drawn prior to the original dose, and after first cefazolin administration at 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 90 min, 180 min, and every 60 min thereafter. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min and plasma was transferred. Serial microdialysis samples were obtained from skeletal muscle and adipose tissue near the surgical site in 30 min intervals throughout the surgery. Samples were stored at −80ºC until analysis. Both plasma samples and microdialysis samples were analyzed by a previously published high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method [

9].

Figure 1 depicts a representative patient example from each group to illustrate dosing and sampling.

2.5. Clinical Microdialysis Procedure

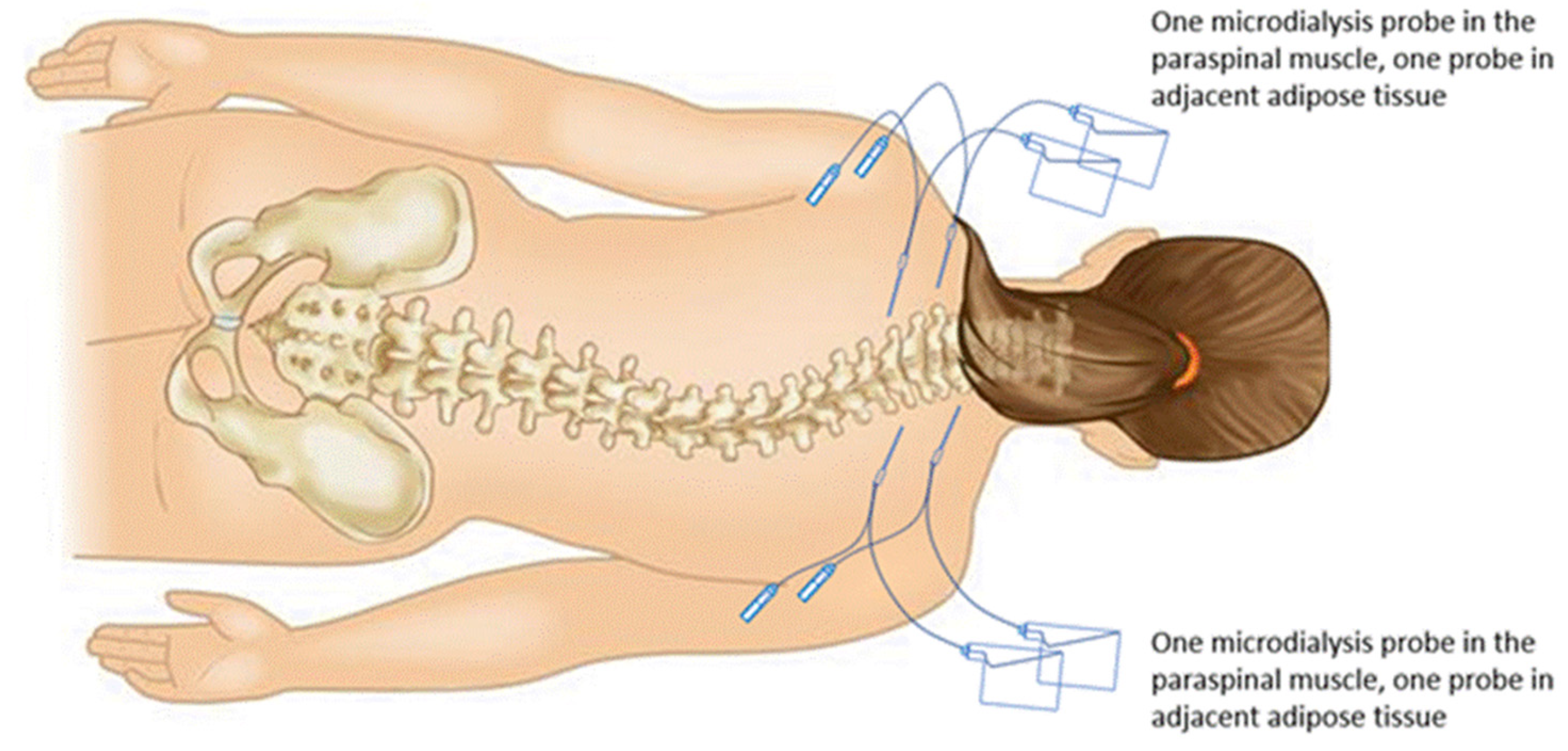

Two coaxial microdialysis probes were inserted percutaneously after the induction of anesthesia into left and right paraspinal muscles 2 levels superior to the planned incision, and 2 additional probes were inserted into subcutaneous adipose tissue lateral to the muscle probes (

Figure 2). Each microdialysis catheter contained a 30 mm polyarylethersulfone membrane with a molecular cutoff of 20 kDa (63 MD catheter; M Dialysis AB, Solna, Sweden) and was connected to a 107 microdialysis pump (M Dialysis AB) with a perfusion flow rate at 1 µL/min. All 4 probes were perfused with normal saline containing 10 µg/mL cefuroxime prepared by the investigational drug service as a calibrator for clinical microdialysis of cefazolin [

9]. The interstitial concentration of cefazolin was calculated using the following equation:

where cefazolin recovery is proportionate to the rate of cefuroxime disappearance from the perfusate as expressed in the following equation:

2.6. Pharmacokinetic and Statistical Analysis

Key pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, tmax, t1/2, CL, AUC) for cefazolin were determined from concentration-time profiles in plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue and muscle tissue using a non-compartmental method conducted in commercially available software (Phoenix WinNonlin, Pharsight Corporation, CA, USA). For PK parameter calculations of plasma cefazolin concentrations after intermittent bolus dose administration, we extrapolated missing concentrations at the nadir and peak of the PK disposition curve using the terminal half-life of cefazolin during the last dosing interval and the 5 min post-dose concentrations from the previous dose, respectively. The biologically active free plasma concentrations of cefazolin were only measured in the first 4 subjects and calculated based on the average protein binding for the remaining subjects. Due to the nature of microdialysis collection, the Cmax values for the interstitial concentrations of cefazolin represent the average concentration throughout the 30-min collection interval. Plasma and tissue concentrations of cefazolin were related to published MIC values to determine the time above MIC (fT>MIC), which is the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) factor most closely related to the antibacterial effect of cefazolin in vivo. Data were checked for implausible values and distributional form. Group comparisons were made using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Tests of hypotheses were 2-sided using a specified significance level of .05. SAS software version 9.4 (Cary, NC) was used for data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

Thirteen patients were enrolled in this study, with 12 randomized to either bolus or continuous infusion dosing. Six patients were included in each of the groups. One patient was withdrawn because study staff were not available at the time of the procedure. Cefazolin tissue concentration data were found to be unusable for 3 patients due to problems with sample processing yielding analyzable data for a total of 9 patients (4 patients in the bolus group and 5 patients in the infusion group). Demographic and intraoperative data are presented in

Table 1. Patients were well matched for health status, weight, renal function, intraoperative blood loss, and fluid resuscitation. Half of the patients in the bolus group were male, while all in the infusion group were female. No participants received allogeneic red blood cells intraoperatively. Surgeries were typically concluded in under 6 hours. Only 1 patient in the bolus group required a third dose of cefazolin during closure of the operative incision. This dose was excluded from analysis.

3.2. Drug Dosing and Cefazolin Concentrations in Plasma, Muscle, and Subcutaneous Adipose Compartments

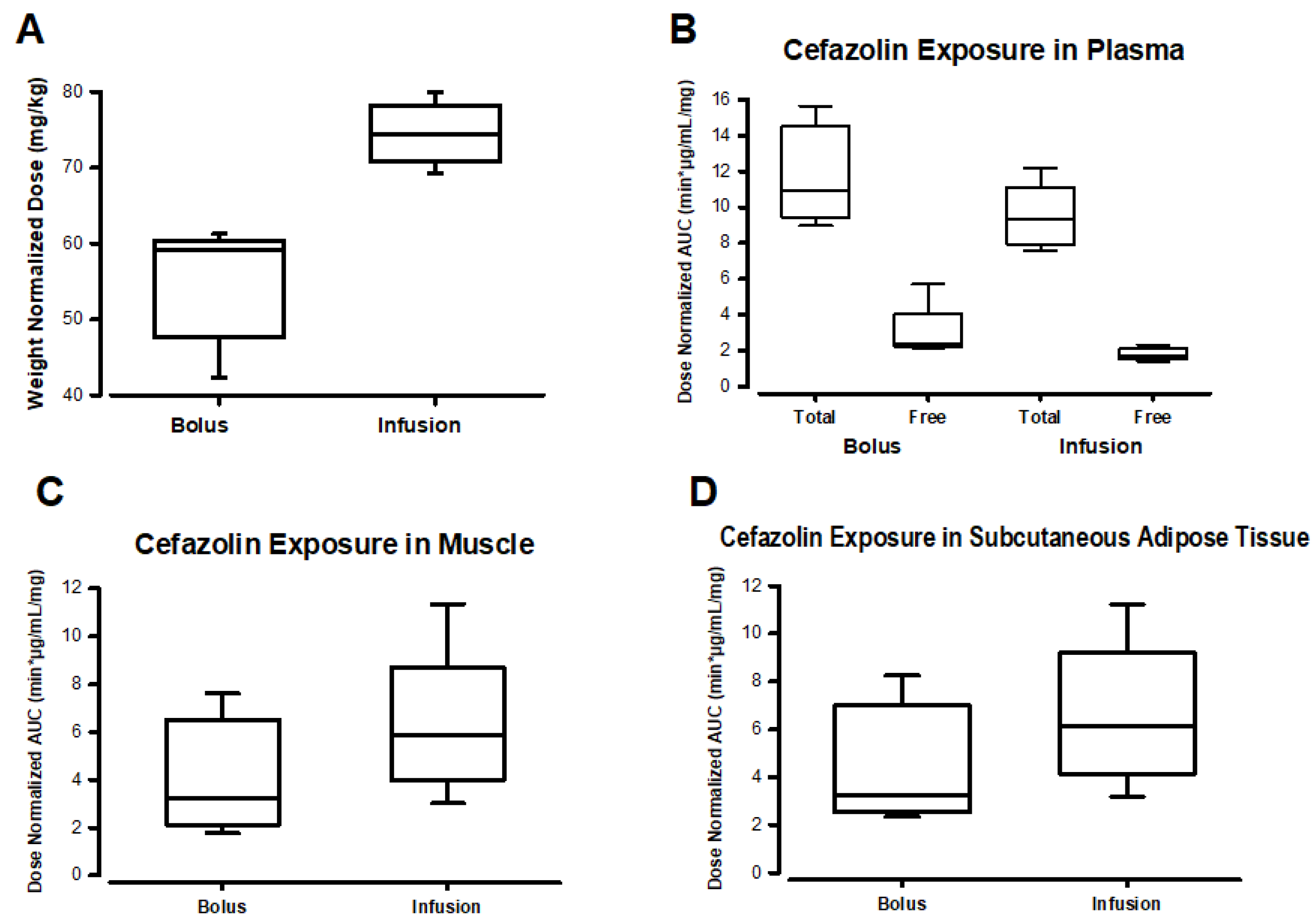

As expected from the dosing scheme, patients in the infusion group received more cefazolin than those in the bolus group (

Figure 3A,

Table S3). This is because the infusion group received both an IV bolus and an equivalent infusion dose immediately after, which added an additional cefazolin dose to the total dose administered in the infusion group. When analyzing total drug exposure as area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of plasma concentrations, the AUC was similar in both groups for both total and free cefazolin after dose normalization (

Figure 3B,

Table S3). However, the total drug exposure (AUC) in muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue was greater in the infusion group, even after values were normalized by the administered cefazolin dose (

Figure 3C–D,

Table S3). No statistically significant differences were found between groups in comparing normalized doses or AUC values (

Table S3).

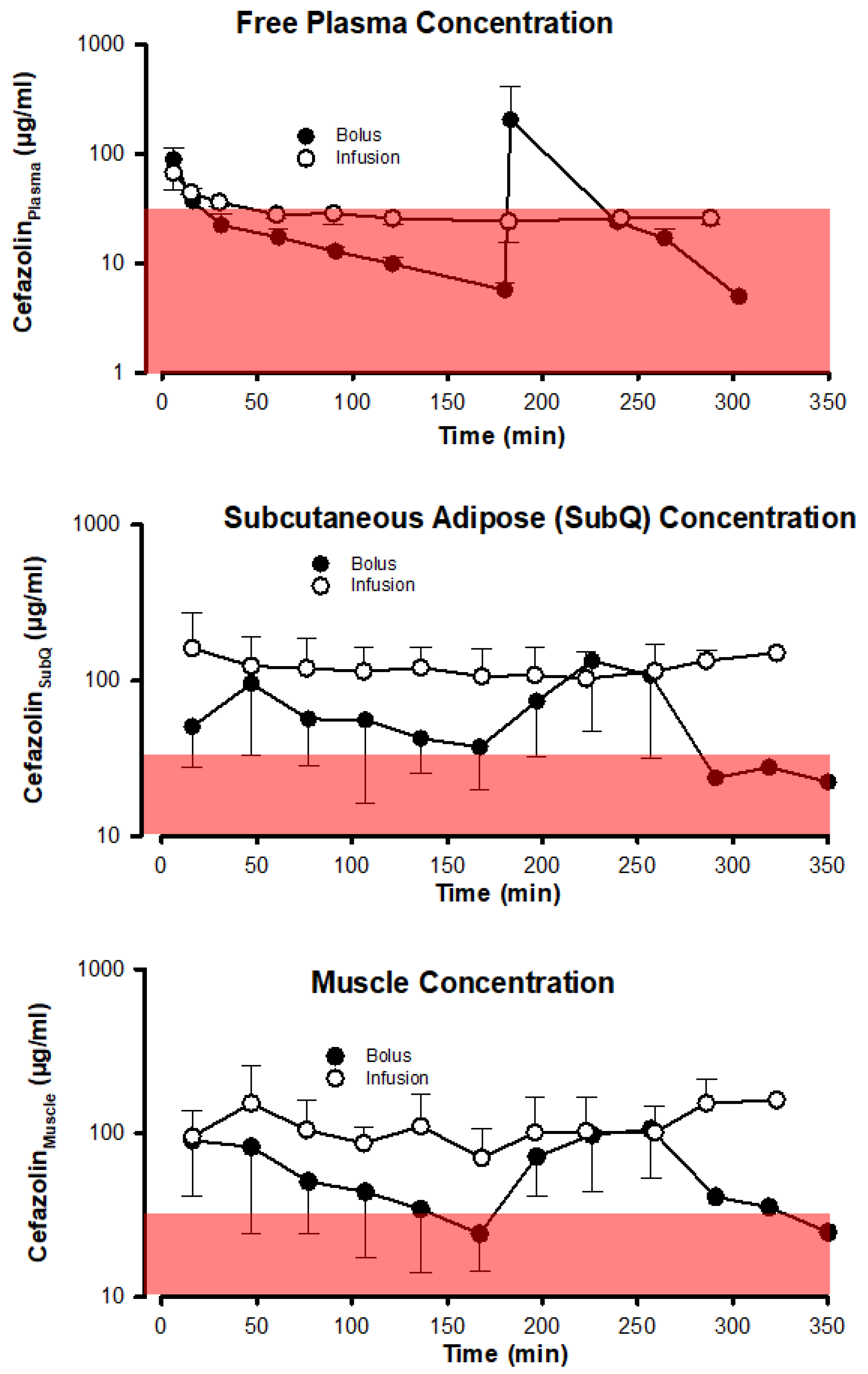

The antibacterial effect of the 2 different dosing schemes based on unbound cefazolin concentrations in plasma, muscle, and subcutaneous adipose tissue is depicted in

Figure 4 using the most relevant PK-PD metric

fT>MIC. Bolus dosing of cefazolin results in much more variable and typically lower cefazolin concentrations in all 3 compartments than infusion dosing. More importantly, using a cefazolin concentration threshold of 32 µg/ml, chosen to exceed by fourfold a bacteriostatic concentration of 8 µg/ml that is based on the typical serial dilution procedure used in determining minimal inhibitory concentrations of cefazolin to prevent growth of bacteria (

Table 2) in 90% of cases, shows that plasma concentrations generally decreased below 32 µg/ml in both the bolus and infusion groups. In subcutaneous adipose tissue and muscle the variability in cefazolin concentration introduced by bolus dosing was sufficient to drive tissue concentrations below 32 µg/ml for a period preceding the next bolus dose.

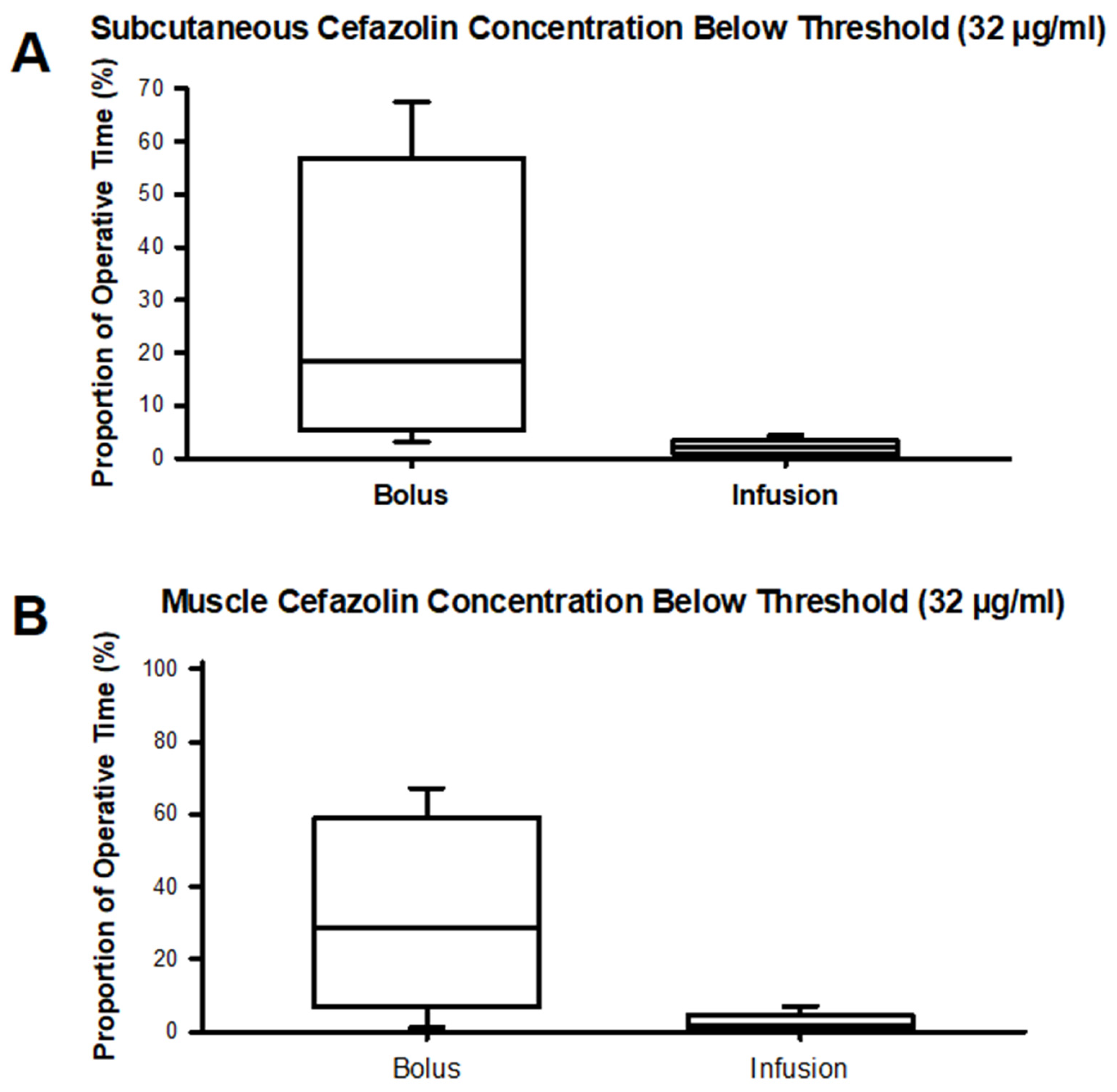

Figure 5 (

Table S4) depicts the time spent below a cefazolin concentration of 32 µg/ml in subcutaneous adipose tissue and muscle tissue. For the bolus group, median times spent below the 32 µg/ml threshold in muscle approximate a third of the typical operative time of 6 hours. Free plasma concentrations decreased below 32 µg/ml regardless of the cefazolin dosing scheme in most patients and for the majority of the procedure. No statistically significant differences were found between groups in comparing time spent below a cefazolin concentration of 32 µg/ml (

Table S4).

4. Discussion

Our study found that continuous infusion of cefazolin more consistently resulted in bactericidal concentrations in subcutaneous and muscle tissues than cefazolin administration by intermittent bolus in patients undergoing PSF for AIS at an experienced tertiary care center. Particularly for the muscle compartment, tissue concentrations were less than a target of 32 μg/mL for nearly a third of the entire procedure when cefazolin was administered as an intermittent bolus. While tissue concentrations are an intermediate outcome, they lie on the causal chain connecting skin flora to surgical site infection. Given the low rate of SSIs in this relatively healthy cohort of immunocompetent patients, a definitive outcome study would require a sample size that well exceeds the capacity of a single center. Although our study was not designed to study SSI directly and was underpowered to yield statistically significant data, we believe it offers several important insights into how to better dose cefazolin in this population.

Our study compared cefazolin infusion dosing with a bolus dosing regimen that is relatively aggressive in both dose and in redosing interval. Therefore, both regimens are likely to cover gram positive organisms such as MSSA and

S. epidermidis adequately throughout the surgical period, especially since even during treatment of a gram-positive infection tissue concentrations above MIC are only required for 40% to 50% of the time [

7]. Similar results to ours for plasma and muscle concentrations were reported for bolus administration of cefazolin in PSF for AIS [

10]. For the overall less susceptible and more variably susceptible gram-negative organisms (

Table 2), the impact of the dosing scheme is likely more important. This is reflected in the recommendation to achieve target concentrations in excess of the MIC of gram-negative organisms at the site of infection for a minimum of 60% to 70% of the treatment time [

7]. Whether the paradigm of “treatment of an active infection” is applicable to the perioperative period is unknown, but a study of SSIs in 228 spine fusion procedures identified under-dosing of cefazolin perioperatively as an important risk factor for both gram-positive and -negative SSIs [

11].

Surgical site infections are likely multifactorial. Some infections are clearly caused by direct contamination, i.e., the spread of residual skin flora remaining after antisepsis.

3 For other SSIs, the patient’s own microbiome provides the causative organism when combined with the immunologic perturbation and disruption of physiologic bacterial communities of the perioperative period [

12]. For example, neutrophils may transport viable

S. aureus, internalized at a colonized site such as the nares, to a site of tissue trauma such as the surgical incision. For both types of infections, consistent attainment of adequate tissue concentrations should reduce active infections of the treated patient specifically and the development bacterial resistance in general.

Our finding that infusion dosing minimized the variability of measured drug concentrations (typically measured in plasma) is consistent with the findings from other studies that compared infusion with bolus dosing perioperatively [

5,

13]. Similarly, infusion dosing of cefazolin is preferred in settings such as the treatment of infective endocarditis [

14] or bone/joint infections [

15], where maintenance of bactericidal free plasma concentrations is desirable. More importantly, in cardiac surgery, where cardiopulmonary bypass and bleeding affect active tissue concentrations, cefazolin dosing by continuous infusion reduced the rate particularly of superficial SSIs nearly fourfold [

16]. This improvement in outcome is consistent with the finding of increased infection with underdosing of cefazolin in pediatric non-AIS spine fusion [

11], which shares with cardiac surgery the characteristics of greater blood loss, fluid shifts, and invasiveness.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the study is not sufficiently powered to demonstrate statistical significance in any differences between the 2 groups. The data do demonstrate a clear trend toward greater concentrations in the infusion group suggesting that bactericidal concentrations are more consistently achieved via continuous infusion. Such bactericidal concentrations may be warranted with implantation of hardware and organisms that are known for their ability to form biofilms. Second, our study was focused on measuring tissue concentrations and pharmacokinetics, which are intermediary to the outcome of interest, SSI. Third, consistent with others [

17], we found no effect of blood loss on cefazolin tissue distribution. Thus, even though our measurement techniques could be easily adapted, we are unsure to what extent our data generalize to neuromuscular scoliosis surgeries, where intraoperative blood loss and transfusion are more prevalent.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates administration of cefazolin by continuous infusion intraoperatively results in higher plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue, and muscle concentrations of cefazolin in healthy patients undergoing PSF for AIS than cefazolin administration by intermittent bolus. Continuous infusion is more likely to result in antibiotic concentrations that are bactericidal and should reduce the likelihood of surgical site infections in this population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S3: CONSORT Diagram; Table S3: Comparison of Cefazolin Concentrations; Table S4: Proportion of the Operative Time Spent Below a Threshold Concentration of 32 µg/ml Cefazolin in Adipose and Muscle Compartments for Bolus and Infusion Groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y., L.C.B., T.S. and C.N.S.; formal analysis, Y.Y., F.C.D., C.G., and C.N.S..; investigation, Y.Y, F.C.D, A.W., A.G., S.I., L.C.B, T.S., and C.N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y., F.C.D., and C.N.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y., F.C.D., C.G., S.I., L.C.B., T.S., C.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Pharmaceutics, University of Florida College of Pharmacy, and the Jerome H. Modell Endowed Professorship in Anesthesiology and Department of Anesthesiology, University of Florida College of Medicine.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board (IRB201701129).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bryan Penberthy, MFA, of the University of Florida College of Medicine Department of Anesthesiology’s Communications & Publishing office for his editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dedication

This work is dedicated to the late Hartmut Derendorf, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pharmaceutics, University of Florida College of Pharmacy.

References

- Rudic, T.N.; Althoff, A.D.; Kamalapathy, P.; Bachmann, K.R. Surgical site infection after primary spinal fusion surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: An analysis of risk factors from a nationwide insurance database. Spine 2023, 48, E101–E106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Glotzbecker, M.; Hedequist, D.J. Surgical site infection after pediatric spinal deformity surgery. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2012, 5, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, T.; Floccari, L.; Crawford, H.; Field, A. A microbiology study on the wounds of pediatric patients undergoing spinal fusion for scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2023, 11, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratzler, D.W.; Dellinger, E.P.; Olsen, K.M.; Perl, T.M.; Auwaerter, P.G.; Bolon, M.K.; Fish, D.N.; Napolitano, L.M.; Sawyer, R.G.; Slain, D.; Steinberg, J.P.; Weinstein, R.A.; American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; Infectious Disease Society of America; Surgical Infection Society; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2013, 70, 195–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, B.I.; Roger, C.; Ikeda, K.; Todorovic, M.S.; Wallis, S.C.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. Comparative total and unbound pharmacokinetics of cefazolin administered by bolus versus continuous infusion in patients undergoing major surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 118, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelenitsky, S.A.; Lawson, C.; Calic, D.; Ariano, R.E.; Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J.; Zhanel, G.G. Integrated pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic modelling to evaluate antimicrobial prophylaxis in abdominal surgery. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2902–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, W.A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: Rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tams, C.; Dooley, F.C.; Sangari, T.S.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, S.N.; Stoker, R.E.; Phillips, S.A.; Koenig, M.; Wishin, J.M.; Molinari, S.C.; Blakemore, L.C.; Seubert, C.N. Methadone and a clinical pathway in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis surgery: A historically controlled study. Global Spine J. 2020, 10, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chandasana, H.; Sangari, T.S.; Seubert, C.; Derendorf, H. Simultaneous retrodialysis by calibrator for rapid in vivo recovery determination in target site microdialysis. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107, 2259–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himebauch, A.S.; Sankar, W.N.; Flynn, J.M.; Sisko, M.T.; Moorthy, G.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Zuppa, A.F.; Fox, E.; Dormans, J.P; Kilbaugh, T.J. Skeletal muscle and plasma concentrations of cefazolin during complex paediatric spinal surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salsgiver, E.; Crotty, J.; LaRussa, S.J.; Bainton, N.M.; Matsumoto, H.; Demmer, R.T.; Thumm, B.; Vitale, M.G.; Saiman, L. Surgical site infections following spine surgery for non-idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2017, 37, e476–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.R.; Alverdy, J.C.; Vavilala, M.S. Emerging paradigms in the prevention of surgical site infection: The patient microbiome and antimicrobial resistance. Anesthesiology 2022, 137, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adembri, C.; Ristori, R.; Chelazzi, C.; Arrigucci, S.; Cassetta, M.I.; De Gaudio, A.R.; Novelli, A. Cefazolin bolus and continuous administration for elective cardiac surgery: Improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 140, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellouard, R.; Deschanvres, C.; Deslandes, G.; Dailly, É.; Asseray, N.; Jolliet, P.; Boutoille, D.; Gaborit, B.; Grégoire, M. Population pharmacokinetic study of cefazolin dosage adaptation in bacteremia and infective endocarditis based on a nomogram. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00806–e00819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, V.; Durand, F.; Kitzis, M.D.; Lhotellier, L.; Ziza, J.M.; Mamoudy, P.; Desplaces, N. Continuous cefazolin infusion to treat bone and joint infections: Clinical efficacy, feasibility, safety, and serum and bone concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magruder, J.T.; Grimm, J.C.; Dungan, S.P.; Shah, A.S.; Crow, J.R.; Shoulders, B.R.; Lester, L.; Barodka, V. Continuous intraoperative cefazolin infusion may reduce surgical site infections during cardiac surgical procedures: A propensity-matched analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2015, 29, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polly, D.W. Jr.; Meter, J.J.; Brueckner, R.; Asplund, L.; van Dam, B.E. The effect of intraoperative blood loss on serum cefazolin level in patients undergoing instrumented spinal fusion. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 1996, 21, 2363–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).