Submitted:

09 May 2024

Posted:

10 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Summary

2. Data Description

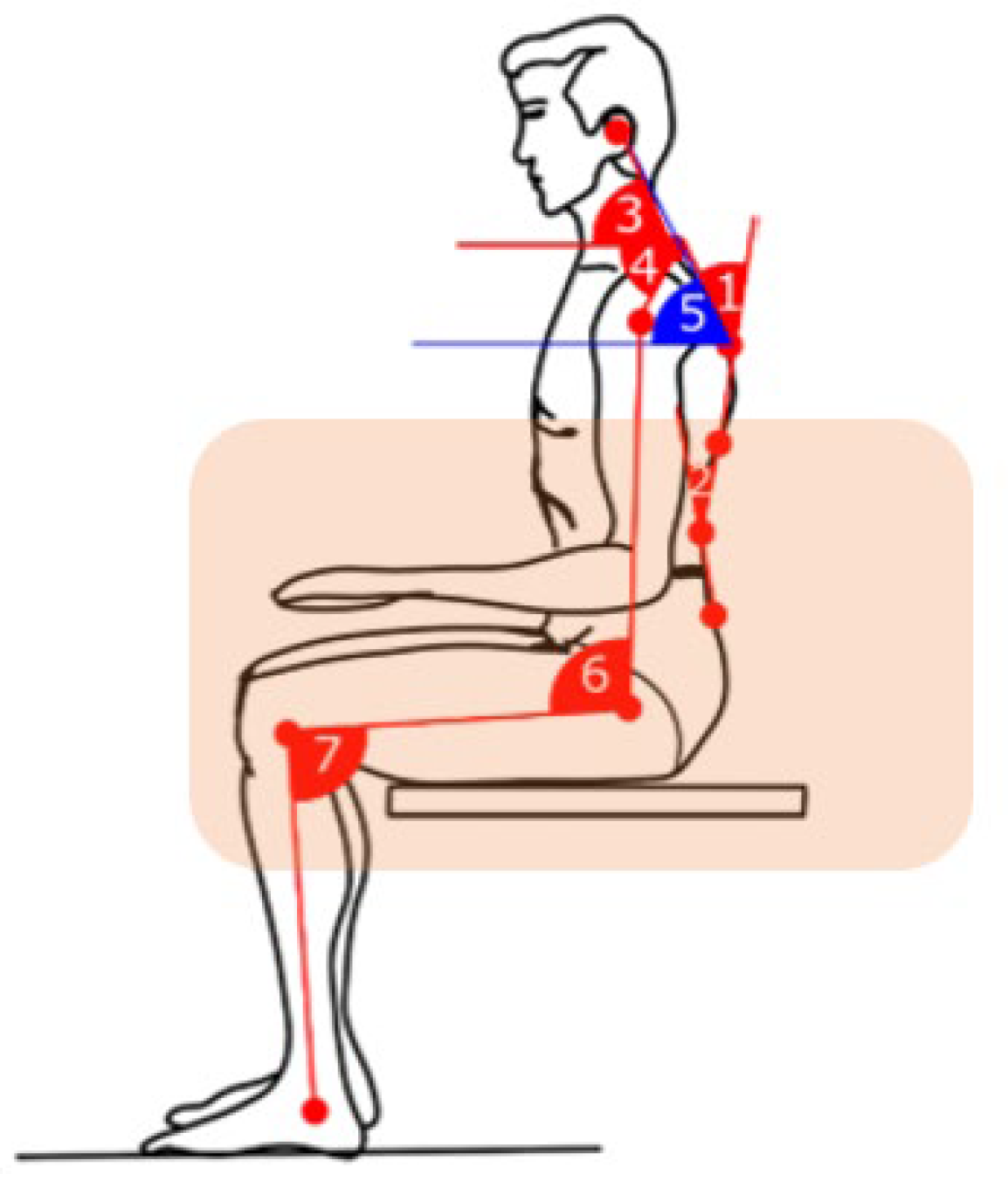

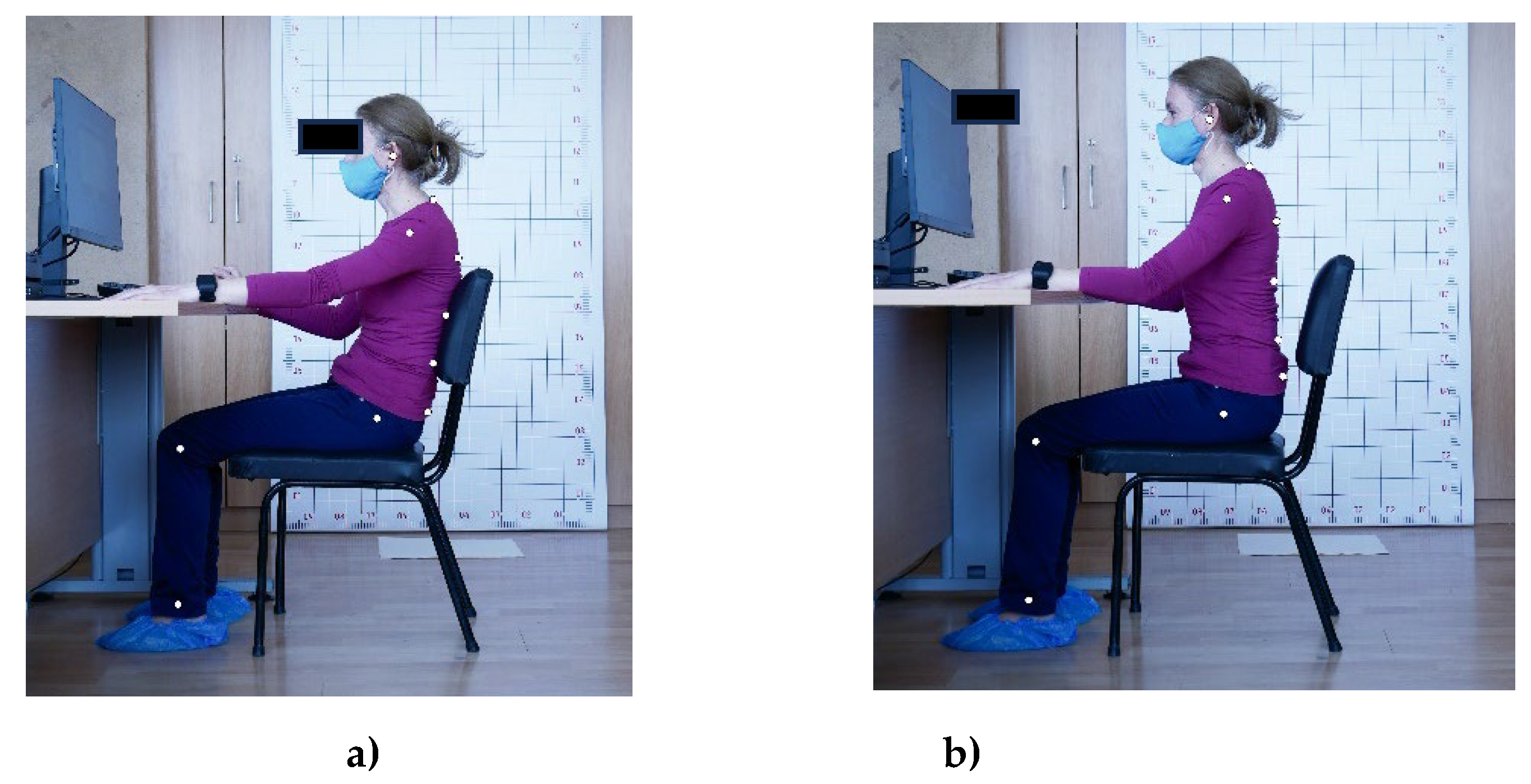

- Pictures with markers – Pictures in .jpg with markers ready to use (ten markers corresponding to body map). File name format is “ID.X”, where ID corresponds to Participant ID numbers and “X” denotes the natural sitting posture (5) and the corrected posture (6). Photo IDs correspond to Questionnaire IDs;

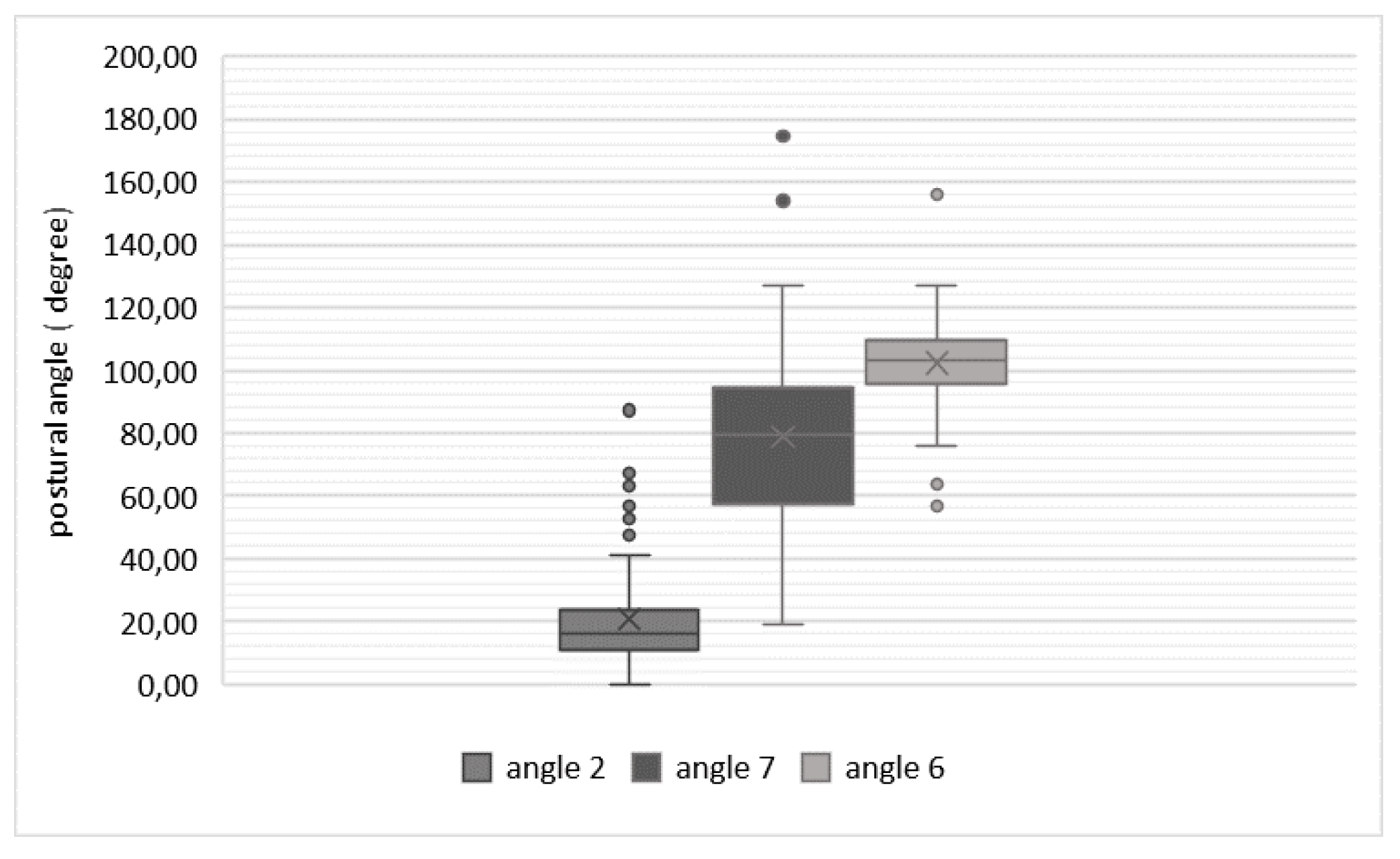

- Postural angle calculations – Angle.csv file containing in each column postural angle calculations (angle 2, angle 6, angle 7)

- a file with questionnaire responses

3. Methods

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Experimental Procedure

3.4. Data Processing and Statistics

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Questionnaire-Based Analysis

4.2. Photogrametric Analysis

4.2.1. Natural Postures-Based Scenario

4.2.2. Corrected Postures-Based Scenario

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soares C, Shimano SGN, Marcacine PR, Fernandes LFRM, de Castro LLPT, de Walsh IAP. Ergonomic interventions for work in a sitting position: an integrative review. Rev Bras Med Trab. 2023, 18;21(1): e2023770.

- European agency for safety and health at work, Musculoskeletal disorders. Available online: URL https://osha.eu- ropa.eu/en/themes/musculoskeletal disorders (accessed on 01 Mart 2024). (accessed on 01 Mart 2024).

- Jacquier-Bret, J., Gorce, P. Effect of day time on smartphone use posture and related musculoskeletal disorders risk: a survey among university students. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorder 24, 725 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sharan D. Musculoskeletal disorders in 115 students due to overuse of electronic devices: Risk factors and clinic. In Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association (IEA 2018), Florence, Italy, August 26-30, 2018.

- Montuori P, Cennamo LM, Sorrentino M, Pennino F, Ferrante B, Nardo A, Mazzei G, Grasso S, Salomone M, Trama U, Triassi M, Nardone A. Assessment on Practicing Correct Body Posture and Determinant Analyses in a Large Population of a Metropolitan Area. Behavioral Sciences. 2023, vol.13, issue 2. [CrossRef]

- Vachinska S., Markova V., Ganchev T. A Risk Assessment Study on Musculoskeletal Disorders in Computer Users Based on A Modified Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. 2022, Vol. 374. [CrossRef]

- Shin JH, Wang S, Yao Q, Wood KB, Li G. Investigation of coupled bending of the lumbar spine during dynamic axial rotation of the body. Eur Spine J. 2013 Dec;22(12):2671-7. Epub 2013 Apr 28. PMID: 23625336; PMCID: PMC3843802. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein IA, Malik Q, Carville S, Ward S. Low back pain and sciatica: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2017 Jan 6;356: i6748. Erratum in: BMJ. 2021 Jul 14;374: n1627. PMID: 28062522. [CrossRef]

- Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Martel MO, Joshi AB, Cook CE. Rehabilitation management of low back pain - it’s time to pull it all together! J Pain Res. 2017 Oct 3; 10:2373-2385. PMID: 29042813; PMCID: PMC5633330. [CrossRef]

- Crawford J. O., R. Graveling, A. Davis, E. Giagloglou, et al.: European Risk Observatory Report, Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: from research to practice. What can be learnt? EU-OSHA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Machado, Gustavo C., Maher G., Ferreira P., Harris Ian A., Deyo R., McKay D., Li Qiang, Ferreira M. Trends, Complications, and Costs for Hospital Admission and Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. SPINE, 2017, vol. 42, pp. 1737-1743. [CrossRef]

- Lee DE, Seo SM, Woo HS, Won SY. Analysis of body imbalance in various writing sitting postures using sitting pressure measurement. J Phys Ther Sci. 2018, vol.30, issue 2. [CrossRef]

- Du SH, Zhang YH, Yang QH, Wang YC, Fang Y, Wang XQ. Spinal posture assessment and low back pain. EFORT Open Rev. 2023 Sep 1;8(9):708-718. PMID: 37655847; PMCID: PMC10548303. [CrossRef]

- Fatemi R, Javid M, Najafabadi EM. Effects of William training on lumbosacral muscles function, lumbar curve, and pain. Back Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2015;28(3):591-7. PMID: 25736954. [CrossRef]

- Korakakis V., O’Sullivan K., O’Sullivan P. B., Evagelinou V., Sotiralis Y., Sideris Al., Sakellariou K., Karanasios S., Giakas G., Physiotherapist perceptions of optimal sitting and standing posture. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, Vol.39, pp. 24-31, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bayar B., Güp A., Oruk D., Dongaz Ö., Doğu E, Bayar K. Development of the postural habits and awareness scale: a reliability and validity study. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Debora Soccal Schwertnera, Raul Alexandre Nunes da Silva Oliveirab, Alessandra Swarowskya, Érico Pereira Gomes Feldenc, Thais Silva Beltramec and Micheline Henrique Araújo da Luz Koericha, Young people’s low back pain and awareness of postural habits: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation 35 (2022) 983–992 983. [CrossRef]

- Jia, N., Li, T., Hu, S. et al. Prevalence and its risk factors for low back pain among operation and maintenance personnel in wind farms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17, 314 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-C.; Chu, E.T.-H.; Lee, C.-R. An Automated Sitting Posture Recognition System Utilizing Pressure Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, 5894. [CrossRef]

- Furlanetto TS, Sedrez JA, Candotti CT, Loss JF. Photogrammetry as a tool for the postural evaluation of the spine: A systematic review. World J Orthop. 2016 Feb 18;7(2):136-48. PMID: 26925386; PMCID: PMC4757659. [CrossRef]

- G. Kandasamy, J. Bettany-Saltikov, and P. van Schaik, ‘Posture and Back Shape Measurement Tools: A Narrative Literature Review’, Spinal Deformities in Adolescents, Adults and Older Adults. IntechOpen, Apr. 14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Victor C.H. Chan, Gwyneth B. Ross, Allison L. Clouthier, Steven L. Fischer, Ryan B. Graham. (2021). The role of machine learning in the primary prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A scoping review, Applied Ergonomics,vol. 98,2022. [CrossRef]

- Laidi R., L. Khelladi, M. Kessaissia and L. Ouandjli. 92023). Bad Sitting Posture Detection and Alerting System using EMG Sensors and Machine Learning. 2023 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Bali, Indonesia, 2023, pp. 324-329. [CrossRef]

- Jeong H., W. Park. (2021). Developing and Evaluating a Mixed Sensor Smart Chair System for Real-Time Posture Classification: Combining Pressure and Distance Sensors. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 1805-1813, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bontrup C., Taylor W. R., Fliesser М., Visscher Р., Green Т., Pia-Maria Wippert, Zemp R., Low back pain and its relationship with sitting behaviour among sedentary office workers, Applied Ergonomics, Vol. 81, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- Keskin Y., Ürkmez B., Öztürk F., Kepekçi M., Aydın T., Correlation Between Sitting Duration and Position and Lumbar Pain among Office Workers, Haydarpasa Numune Med J, vol.61, n1, pp 1-6, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kett, A.R.; Sichting, F., Milani, T.L. The Effect of Sitting Posture and Postural Activity on Low Back Muscle Stiffness. Biomechanics, vol1, pp.214-224, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Slater D, Korakakis V, O’Sullivan P, Nolan D, O’Sullivan K. “Sit Up Straight”: Time to Re-evaluate. Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 49, issue 8, pp.562-564, 2019. PMID: 31366294. [CrossRef]

- Swain CTV, Pan F, Owen PJ, Schmidt H, Belavy DL. No consensus on causality of spine postures or physical exposure and low back pain: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Journal of Biomechanic. Vol.102, 2020. [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan K., McCarthy R., White A., O’Sullivan L., Dankaerts W., Can we reduce the effort of maintaining a neutral sitting posture? A pilot study, Manual Therapy, Vol 17, Issue 6, pp. 566-571, 2012., . [CrossRef]

- Schmidt H., Bashkuev M., Weerts J., Graichen F., Altenscheidt J., Maier Ch., Reitmaier S., How do we stand? Variations during repeated standing phases of asymptomatic subjects and low back pain patients,Journal of Biomechanics,Vol 70, pp. 67-76, 2018. [CrossRef]

| Degree of pain/discomfort | Mild pain | Moderate pain | Severe pain | Very severe | Worst pain possible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back pain | 12 | 18 | 20 | 4 | 2 |

| Low back pain | 9 | 16 | 21 | 7 | 1 |

| Pain in the buttock | 10 | 11 | 12 | 2 | 2 |

| Total people with pain or discomfort (%) | 31% | 45% | 53% | 13% | 5% |

| Classifier type | Accuracy, [%] | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Naïve Bayes | 75.3% | ± 11.2% |

| Generalized Linear Model | 57.3% | ± 18.2% |

| Logistic Regression | 60.7% | ± 13.6% |

| Fast Large Margin | 60.7% | ± 13.6% |

| Deep Learning | 63.3% | ± 22.9% |

| Decision Tree | 59.3% | ± 18.9% |

| Random Forest | 61.3% | ± 16.8% |

| Gradient Boosted Trees | 59.3% | ± 25.2% |

| SVM | 64.7% | ± 19.5% |

| Classifier type | Accuracy, [%] | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Naïve Bayes | 73.3% | ± 7.2% |

| Generalized Linear Model | 76.7% | ± 7.2% |

| Logistic Regression | 76.7% | ± 7.2% |

| Fast Large Margin | 74.3% | ± 6.4% |

| Deep Learning | 79.5% | ± 7.5% |

| Decision Tree | 72.9% | ± 14.6% |

| Random Forest | 80.0% | ± 16.3% |

| Gradient Boosted Trees | 78.6% | ± 18.9% |

| SVM | 73.3% | ± 12.4% |

| Classifier type | Optimal parameters | Accuracy, [%] | Standard deviation, [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | number of trees 100; criterion Gain Ratio; max depth 10; voting strategy: majority vote |

85.00% | ± 12.30% |

| Deep Learning | 3/ 100/100/2 architecture; the first three layers – neurons with Maxout activation functions, and the two output neurons have SoftMax activation functions. |

82.50% | ± 12.08% |

| Gradient Boosted Trees | number of trees: 50; max depth: 3; learning rate: 0.01 |

81.67% | ± 16.57% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).