1. Introduction

The relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2MD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is complex and multifaceted (

Figure 1). Although the two conditions appear to be distinct, there is evidence suggesting connections between them:

(a) both

diseases share common risk factors such as obesity, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and hyperglycemia;

(b) vascular factors

are common to both diseases. Diabetes increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases

, while vascular issues impact brain health

contributing to Alzheimer’s development; (d) chronic inflammation is present in both conditions development;

(e) chronic hyperglycemia conducts to increased oxidative stress, which damages cells, including neurons leading to Alzheimer’s development;

(f) insulin resistance is the intersection link between T2MD and AD pathways;

(g) diabetes interferes with removal of Aβ-plaques and tau protein tangles, thus contributing to AD development (Yoon et al., 2023; Sankar et al., 2020). Although the link between T2MD and AD is increasingly recognized, much remains to be understood about the specific mechanisms linking these two pathologies. Continuous research is crucial for better understanding this connection and developing effective prevention and treatment strategies for both diseases.

The mechanisms proposed to explain how diabetes contributes to AD could be noted as follows:

(a) Glucose dysregulation. Diabetes leads to dysregulation of glucose metabolism, resulting in hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. Chronic hyperglycemia contributes to oxidative stress, inflammation, and neuronal damage all of them observed in AD (Zhang et al., 2023; Fauzi et al., 2023) (

Figure 2). An increasing amount of research shows that mitochondrial dysfunction presents the li;

(b) Cerebrovascular changes. Diabetes affects the blood vessels, leading to microvascular damage, dysfunctional blood brain barrier (BBB) and impaired cerebral blood flow regulation. This disruption in cerebrovascular homeostasis may contribute to AD by compromising nutrient and oxygen delivery to the brain, as well as impairing the clearance of Aβ-amyloid, a hallmark feature of AD (Stanciu et al., 2020); and

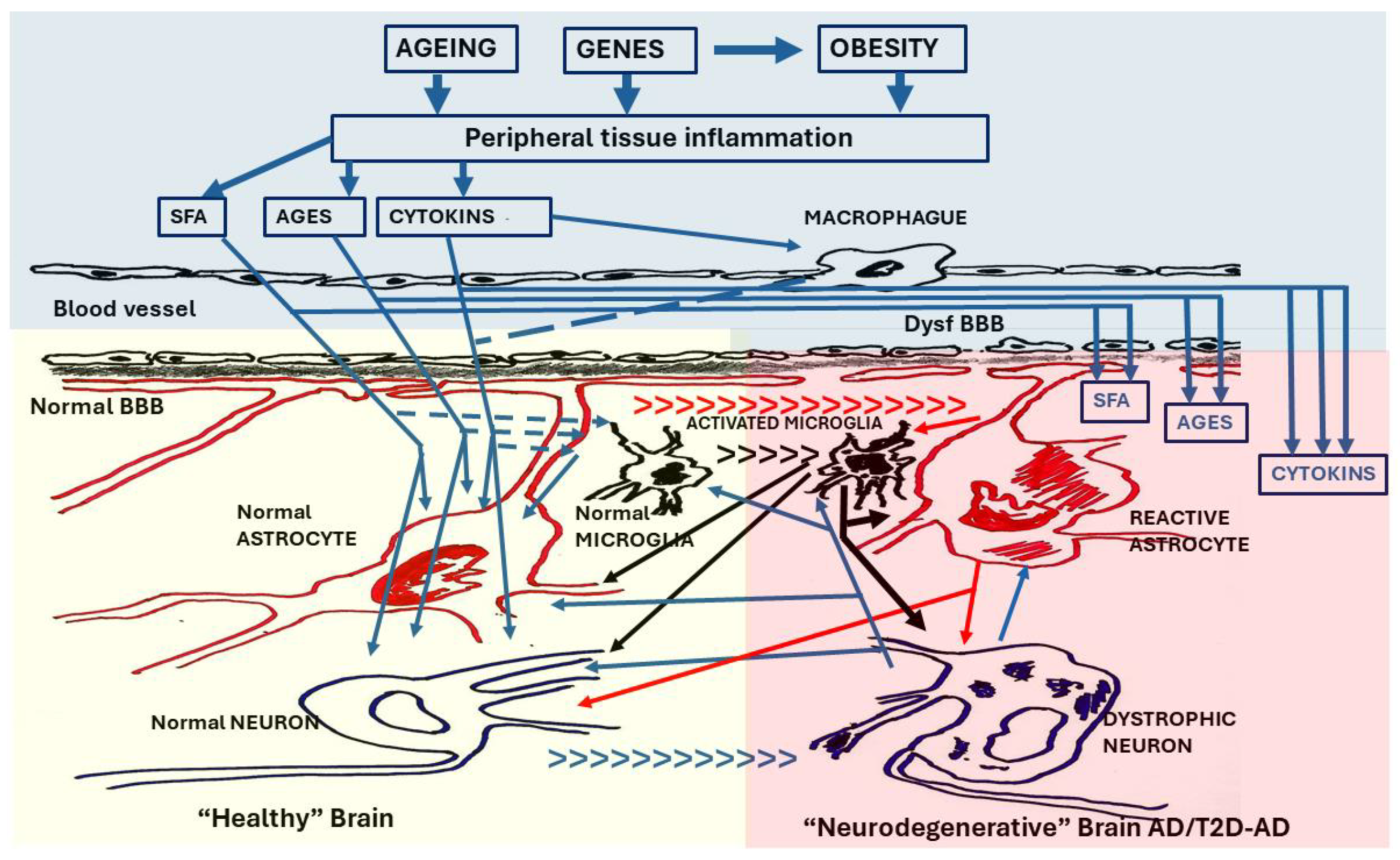

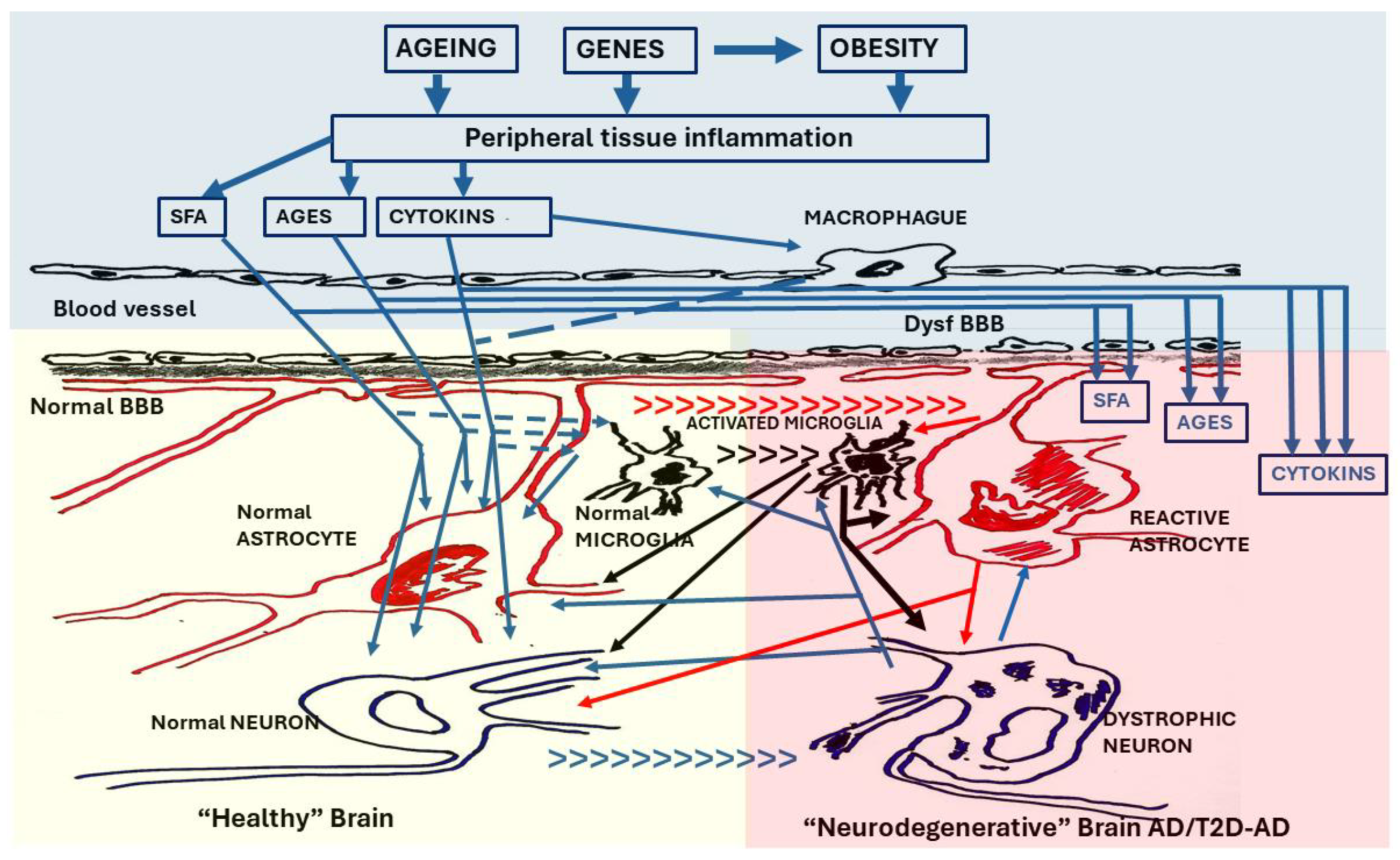

(c) Neuroinflammation (

Figure 3). Diabetes is associated with peripheral chronic low-grade inflammation, characterized by increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This peripheral inflammation is associated with other pathological disorders (oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunctions) and induces neuroinflammation mediated by the activation of glial cells in the brain causing neuroinflammation, which plays a key role in AD progression, contributing to neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration (Zhang et al., 2023; Jolivalt et al., 2010; Ramos-Rodríguez et al., 2013; Ho et al., 2013; Takeda et al., 2013).

The precise molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions remain incompletely understood. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific pathways linking diabetes to AD and to identify potential therapeutic targets. Additionally, clinical studies are necessary to determine whether effective management of diabetes can reduce the risk of developing AD or slow its progression in individuals with both conditions.

The pathogenesis of AD and T2MD involves complex interactions between genetic factors, environmental influences, and lifestyle choices. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA (ncRNA), play critical roles in regulating gene expression without altering the DNA sequence, bridging the gap between genetics, environment, and disease development. Early environmental exposures can influence the likelihood of developing neurodegenerative diseases later in life, highlighting the significant contribution of environmental factors to AD onset. Recent interest has focused on identifying natural compounds, particularly those found in plants, as potential epigenetic regulators for disease treatment. Dietary components like polyphenols and flavonoids have been shown to modulate gene expression through various epigenetic mechanisms, offering potential therapeutic for AD and T2MD by affecting multiple targets. Understanding the genetic and epigenetic targets of these compounds provides insights into their preventive and therapeutic roles in combating these conditions. Moreover, common epigenetic modifications have been implicated in both AD and T2MD, contributing to their pathogenesis. This highlights the connection of epigenetic regulation in complex diseases and underscores the importance of epigenetic-based interventions for prevention and treatment (Sarnowski et al., 2023).

Nutritional programs targeting insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and cognitive impairment associated with T2DM and AD as well as dietary patterns and supplementation have shown promise in improving glycemic control and reducing cognitive decline. However, intervention specificity remains debated. Further clinical research is warranted to explore the preventive and therapeutic roles of nutritional intervention in these conditions. The most appropriate therapies to treat this complex (T2D-AD) will be the objective of the second part of this monograph.

2. Common Risk Factors for the Development of T2DM and AD

In both T2MD and AD, epidemiological studies carried out for many years repeatedly insist on pointing out the existence of intrinsic causes (genetic, comorbidities, age) and extrinsic causes (diet, lifestyle, physical activity, social conditions, environmental conditions).

In recent years, much progress has been made in the characterization of the genes, and their isoforms, that are in some way involved in the presentation and/or development of both pathologies (see below). The isoforms confer different degrees of suffering from the pathologies, which largely explains the individual differences between patients as well as those existing in different subgroups of patients. Some genes are related to some of these pathologies more specifically (although they can cause alterations in related diseases such as metabolic diseases in the case of T2MD, or in neurodegenerative diseases in the case of AD). There are also altered genes common to both pathologies, such as those that involve dysfunctions in lipid metabolism or mitochondrial function.

Diet and personal lifestyle are important determinants for the development of T2DM and AD. Preventive medicine focuses largely on advising and designing a “health” living environment appropriate to each age and individual situation. This topic will be fully developed in the second part of the review. Inadequate diets and sectarianism have long been shown to induce T2DM and AD. Excess intake, both in quantity and abuse of carbohydrates or lipids, leads to a significant alteration in the general metabolism, giving rise to pro-T2DM or pro-neurodegenerative “induced metabolic diseases” (AD and AD-relative). In the field of metabolic diseases, one of the main pathologies induced by diet is Obesity, which is discussed below. It could be said that these two risk factors, inadequate diet and personal lifestyle, directly produce obesity and this, in turn, T2DM.

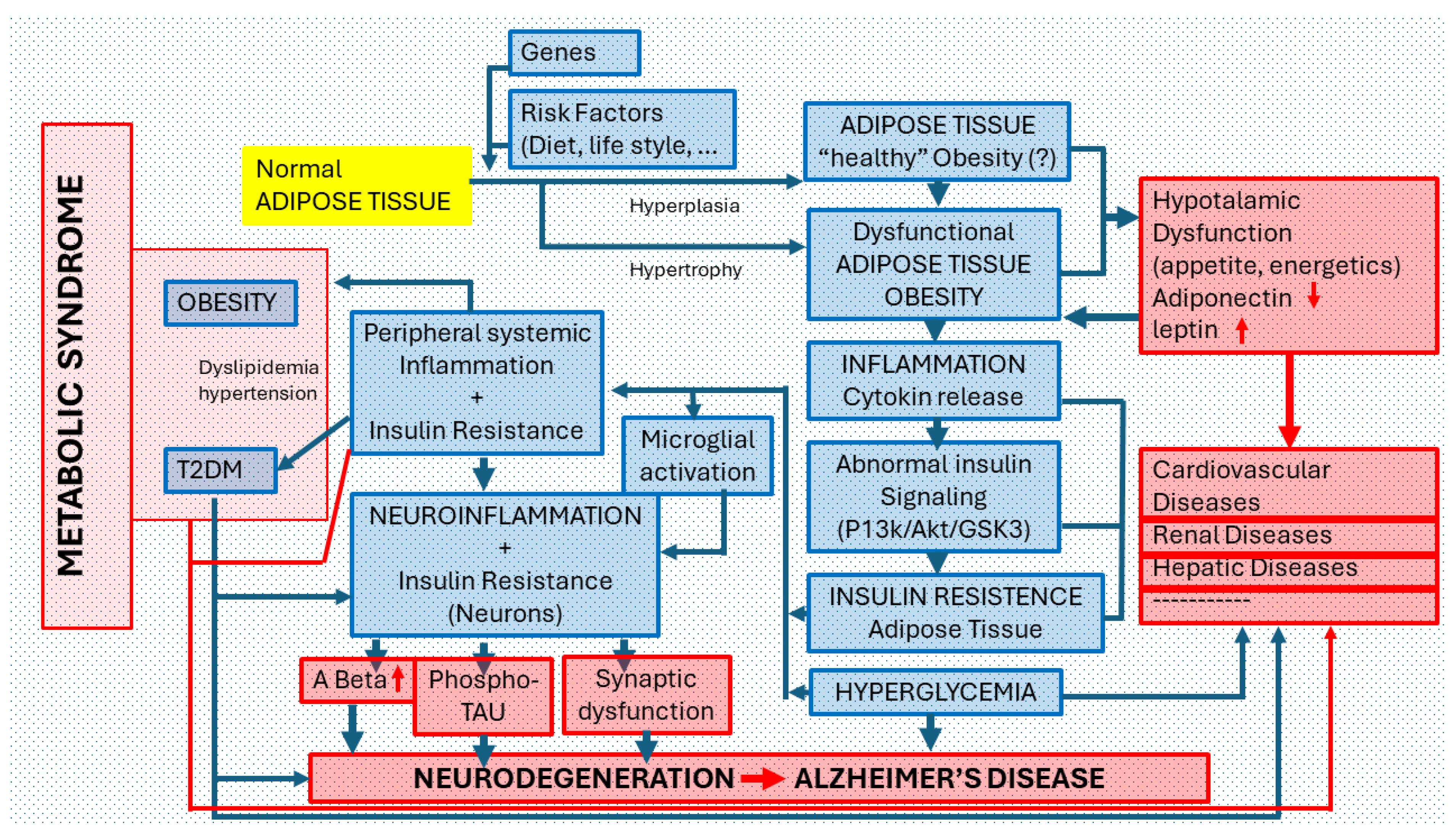

T2DM indirectly leads to AD, a disease that can be directly accelerated by these aforementioned risk factors (

Figure 3). Clinical evidence suggests that lifestyle factors, in particular nutrition, are decisive in AD control and prevention (Flicker, 2010; Solfrizzi et al., 2011; Shah, 2013).

Obesity is defined as a chronic disease characterized by an excessive accumulation of adipose tissue or a pathology where fat accumulates. Obesity occurs when adipocytes increase excessively in number (hyperplasia) and/or in size (hypertrophy) (Ghosh, 2014; Smith, 2015). Adipocyte hyperplasia leads to obese patients exhibiting normal levels of inflammatory markers in the microenvironment of adipose cells (Blüher, 2020). These patients are classified as having metabolically “healthy obesity” and they do not exhibit the typical indications of dyslipidemia or hypertension (Smith et al., 2019). Conversely, hypertrophic adipocytes trigger immune system responses by secreting pro- inflammatory factors (Hildebrandt et al., 2022). As a consequence, the microenvironment undergoes a substantial change to a pro-inflammatory state, characteristic of pathologic obesity (Reilly & Saltiel, 2017), and patients are considered to suffer from unhealthy obesity. This differentiation regarding the “healthiness” of the patient with an obese morphological phenotype is not accepted by many authors who consider that inadequate intake before or after will lead to the presentation of inflammatory alterations and insulin resistance, which are the two basic manifestations of this disease. It must be remembered that there are also patients with obesity in whom the accumulation of fat is not so evident.

Moreover, hypertrophic adipocytes are susceptible to hypoxia (Ghosh, 2014; Rodríguez-Casado et al., 2017). Long-term exposure of adipocytes to pro-inflammatory factors and hypoxia leads to endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, that we can consider the point of the main adipose tissue dysfunction (Ghosh, 2014; Smith, 2015).

This condition promotes the recruitment of immune cells (eosinophils, macrophages) to the adipose tissue. The vicious cycle of more inflammation, results in local insulin resistance (Ghosh, 2014; Smith, 2015). Insulin resistant adipocytes are overwhelmed resulting in ectopic lipid excess translocation into the non-adipose organs like skeletal muscle, liver, pancreas, and heart among others intermediaries of lipid metabolism such as ceramides, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) cause more inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress and systemic insulin resistance that led to oxidative stress and mitochondria dysfunction (

Figure 2) (Ghosh, 2014; Smith, 2015). Under these conditions, the antioxidant defense is altered, and the organs storage capacity is saturated resulting in lipotoxicity that induces peripheral insulin resistance, metabolic insults, and multi-organ dysfunction (Rodríguez-Casado et al., 2017). Insulin resistance produces glucose accumulation in the blood that stimulates the production of more insulin reaching hazardous levels that cause T2MD (Rodríguez-Casado et al., 2017). This condition induces BBB dysfunction, which decreases CNS protection and increases permeability of neuroinflammatory and oxidative mediators along with cytotoxic ceramides from the periphery to the brain (Rodríguez-Casado et al., 2017; Acharya et al., 2013; Takeda et al., 2013) . This triggers the activation of resident immune system —microglia— promoting brain inflammatory response (Rodríguez-Casado et al., 2017) (Bosco et al., 2011; Contreras et al., 2014) that interferes with insulin and its receptor binding interrupting later signaling events (Tong et al., 2009; Capeau, 2008; Rodríguez-Casado et al., 2017) (

Figure 4).

3. Common Molecular Pathways and Therapeutic Targets

Alzheimer’s disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus share common molecular pathways and therapeutic targets, suggesting an interaction between the underlying pathological mechanisms of both diseases (Hamzé et al., 2022). Some of these common molecular targets are included in

Figure 1 and described as follows.

(a) Insulin Resistance (

Figure 6). An increasing amount of research shows that mitochondrial dysfunction presents the li. Insulin and its signaling pathways regulate glucose metabolism and influences cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. Dysfunction in insulin signaling contributes to the development of both T2DM and AD (Galizzi & Di Carlo, 2022; Palavicini et al., 2020; Fauzi et al., 2023).

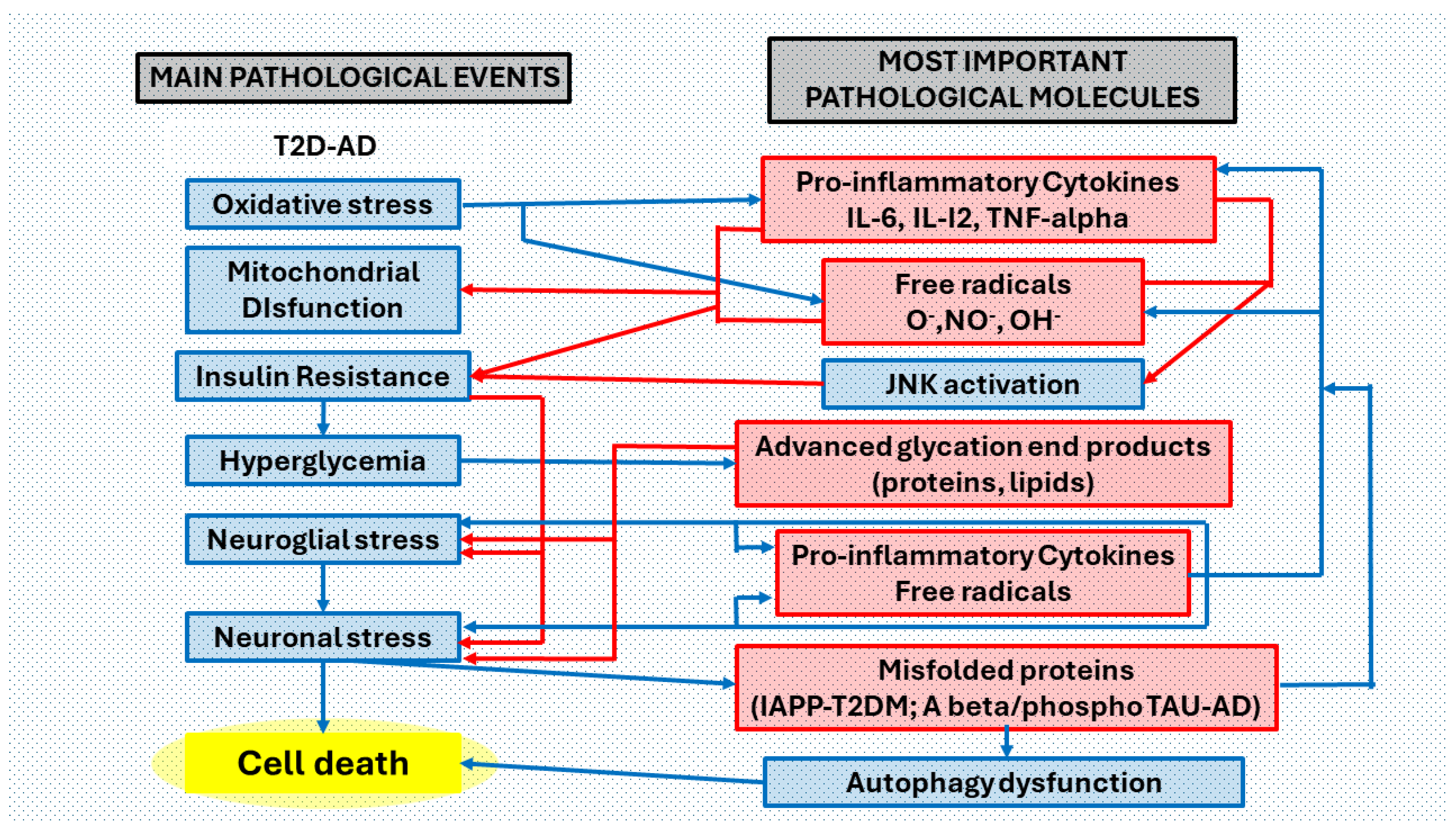

Figure 5.

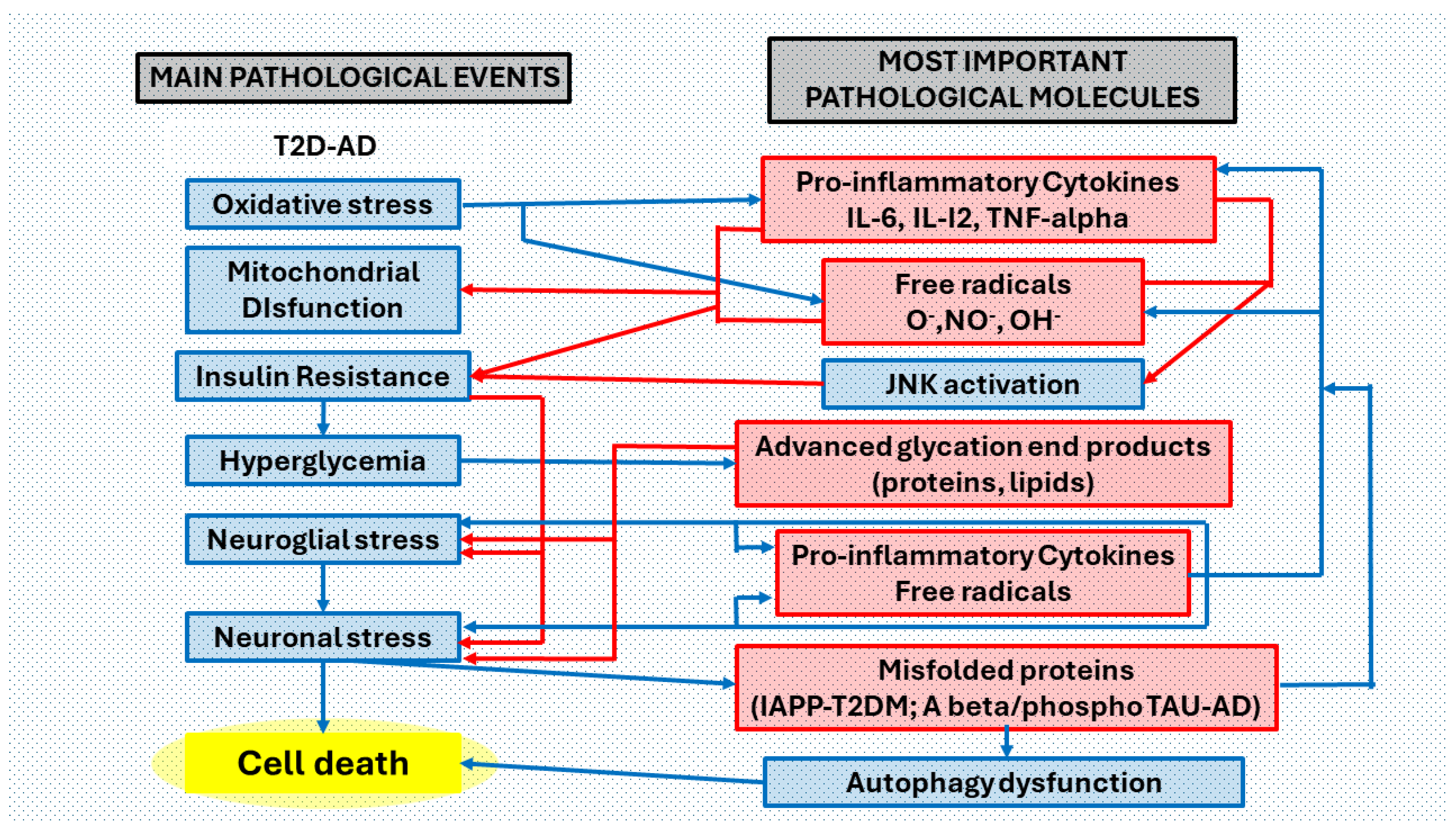

Collaborative effects between T2DM and AD pathological processes in the brain. Main pathological events and most important pathological molecules that are interrelated in the brain of patients with both clinical processes. We have considered six main pathological events ordered according to the most common pathological process in T2DM (oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, neuroglia stress, neuronal stress), in the complex T2D-AD. Peripheral metabolic inflammatory products induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction that triggers neuroinflammation (a complex neuropathological mechanism that involves abnormal neuroglial but also neuronal responses, producing neurotoxins, free radicals, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (blue arrows). Mitochondrial free radical overproduction impairs functions by changing the redox balance. Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines promote insulin resistance via JNK (c-Jun terminal kinase) activation. Hyperglycemia (consequence of insulin resistance) favors the formation of toxic non enzymatically glycated proteins and lipids (advanced glycation end-products). Accumulation of misfolded proteins (IAPP-diabetes, Aβ and phosphoTAU-Alzheimer’s disease) affects autophagy pathways. Oxidative stress, with the correlation of the production of free radicals and proinflammatory cytokines, is in the first phases of the two pathological processes (T2D and AD) and in the most advanced phases of the same, perhaps becoming more acute in the association of both. Neuroglial stress is the main event in the neuroinflammatory process. Neuronal stress reduces cell survival and promotes apoptosis. Abbreviations: O2• = superoxide radical; HO• = hydroxyl radical; NO• = nitric oxide radical; IL-6 = interleukin 6; IL-12 = interleukin 12; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor alpha; JNK = c-Jun N-terminal kinase; AGEs = advanced glycation end products; Aβ = amyloid beta peptide; IAPP = islet amyloid polypeptide.

Figure 5.

Collaborative effects between T2DM and AD pathological processes in the brain. Main pathological events and most important pathological molecules that are interrelated in the brain of patients with both clinical processes. We have considered six main pathological events ordered according to the most common pathological process in T2DM (oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, neuroglia stress, neuronal stress), in the complex T2D-AD. Peripheral metabolic inflammatory products induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction that triggers neuroinflammation (a complex neuropathological mechanism that involves abnormal neuroglial but also neuronal responses, producing neurotoxins, free radicals, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (blue arrows). Mitochondrial free radical overproduction impairs functions by changing the redox balance. Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines promote insulin resistance via JNK (c-Jun terminal kinase) activation. Hyperglycemia (consequence of insulin resistance) favors the formation of toxic non enzymatically glycated proteins and lipids (advanced glycation end-products). Accumulation of misfolded proteins (IAPP-diabetes, Aβ and phosphoTAU-Alzheimer’s disease) affects autophagy pathways. Oxidative stress, with the correlation of the production of free radicals and proinflammatory cytokines, is in the first phases of the two pathological processes (T2D and AD) and in the most advanced phases of the same, perhaps becoming more acute in the association of both. Neuroglial stress is the main event in the neuroinflammatory process. Neuronal stress reduces cell survival and promotes apoptosis. Abbreviations: O2• = superoxide radical; HO• = hydroxyl radical; NO• = nitric oxide radical; IL-6 = interleukin 6; IL-12 = interleukin 12; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor alpha; JNK = c-Jun N-terminal kinase; AGEs = advanced glycation end products; Aβ = amyloid beta peptide; IAPP = islet amyloid polypeptide.

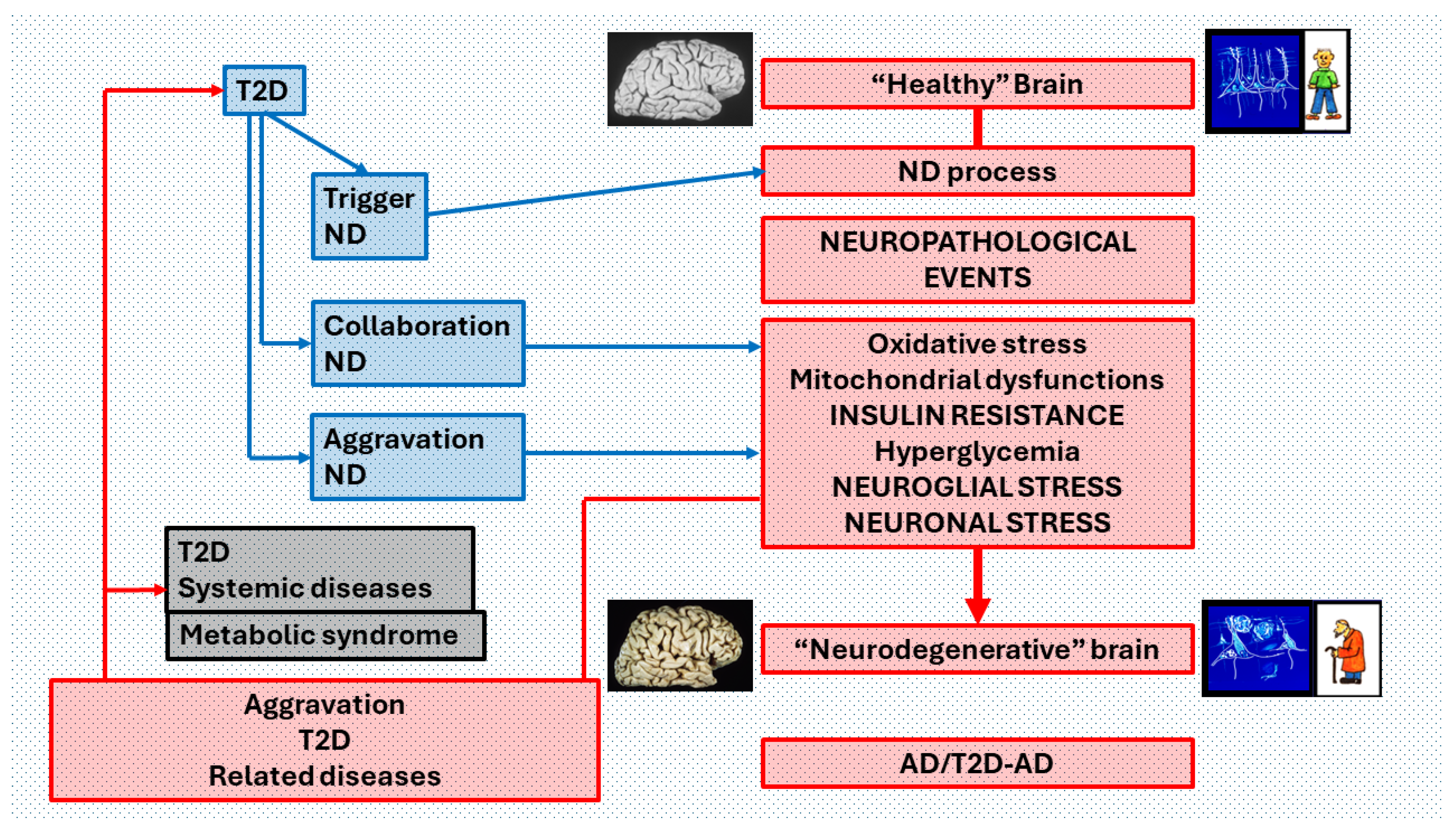

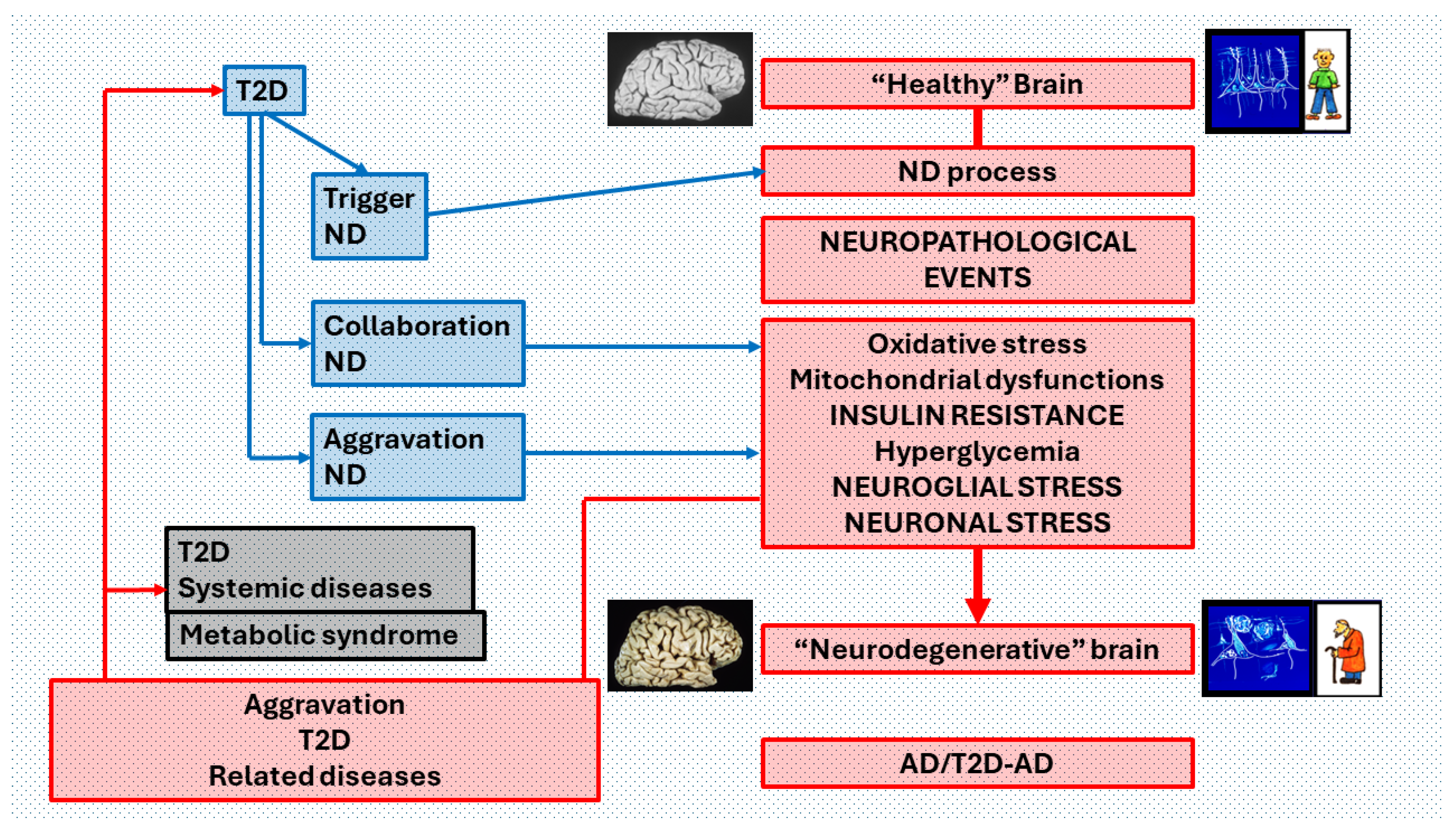

Figure 6.

Pathophysiological relations of T2D and AD that may reciprocally influence and reinforce the progression of both diseases. T2D and AD are closely related from their initiation in an individual’s life to its end. Each disease has its characteristic symptoms and signs in the different organs and systems, but in the brain, the deterioration induced by its coexistence (T2D-AD) manifests as AD with greater neuropathological degeneration and dementia with an earlier presentation and a longer course. fast in many cases. If we consider that in AD there is a Neuro degenerative process (ND process) that leads from a "healthy" brain to a "Neurodegenerative" brain, through a "cascade" of neuropathological events where INSULIN RESISTANCE is crucial, T2D influences several ways the course of this process. It may be a trigger for ND, a contributor to the development of the cascade of neuropathological events (collaboration ND) or an aggravating factor in the final phase of the ND process (aggravation ND). In turn, the neurodegenerative process produces an aggravation of both T2D, and the diseases of various organs and systems associated with T2D, including metabolic syndrome. This pathological influence is exerted both by brain dysfunction in the regulation of organs and tissues, and by the diffusion of toxic products from the brain in neurodegeneration.

Figure 6.

Pathophysiological relations of T2D and AD that may reciprocally influence and reinforce the progression of both diseases. T2D and AD are closely related from their initiation in an individual’s life to its end. Each disease has its characteristic symptoms and signs in the different organs and systems, but in the brain, the deterioration induced by its coexistence (T2D-AD) manifests as AD with greater neuropathological degeneration and dementia with an earlier presentation and a longer course. fast in many cases. If we consider that in AD there is a Neuro degenerative process (ND process) that leads from a "healthy" brain to a "Neurodegenerative" brain, through a "cascade" of neuropathological events where INSULIN RESISTANCE is crucial, T2D influences several ways the course of this process. It may be a trigger for ND, a contributor to the development of the cascade of neuropathological events (collaboration ND) or an aggravating factor in the final phase of the ND process (aggravation ND). In turn, the neurodegenerative process produces an aggravation of both T2D, and the diseases of various organs and systems associated with T2D, including metabolic syndrome. This pathological influence is exerted both by brain dysfunction in the regulation of organs and tissues, and by the diffusion of toxic products from the brain in neurodegeneration.

(b) Inflammation (

Figure 3). Both T2MD and AD are associated with chronic inflammation. Brain inflammation, characterized by the activation of glial cells and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, contributes to the development and progression of AD. Furthermore, the overexpression of proinflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), and acute phase proteins (APP) are present in AD brain. A synergistic pattern between AD senile plaques and proinflammatory cytokines increases the neurological damage to the brain. Moreover, systemic inflammation and immune response activation significantly influence diabetes pathogenesis. Hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia trigger a cascade of detrimental processes, including oxidative/nitrosative stress, endoplasmic, and mitochondrial stress, amplifying cellular damage. These interconnected factors create vicious cycles, perpetuating diabetes progression. Glucotoxicity, insulinopenia, and lipotoxicity induce oxidative/nitrosative stress in neurons, activating various kinases such as protein kinase C (PKC), mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), and jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), as well as redox-sensitive transcriptional factors, including NF-κB. These, in turn, catalyze the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including proinflammatory interleukins (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and chemokine ligands, fueling inflammation and exacerbating neuronal damage (Zhang et al., 2023; Kwon & Koh, 2020; Llorián-Salvador et al., 2024);

(c) Oxidative Stress is implicated in both T2MD and AD development and plays a crucial role in the development of insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction (Valko et al., 2006) (

Figure 2). An increasing amount of research shows that mitochondrial dysfunction presents the li. It occurs due to an excess of ROS produced by an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defense, which damages cells and tissues, contributing to cellular dysfunction and the neurodegenerative process (Houldsworth, 2024; Bhatti et al., 2022). Hyperglycemia induces the production of Free Radicals or oxidative/nitrosative toxic radicals or ROS through several pathways, including the mitochondrial electron transport chain and PKC activation (González et al., 2023). ROS impairs insulin signaling pathways, leading to insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction (Butterfield et al., 2014) as well as endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and diabetic complications development (Yuan et al., 2019). The brain is vulnerable to oxidative damage due to its high metabolic rate, high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids, and relatively low levels of antioxidant defenses (Lee et al., 2020). Another source of ROS production directly mediated by Aβ involves microglia activated in the brain during an inflammatory response to the deposition of extracellular amyloid plaques (Nakajima & Kohsaka, 2001; Tönnies & Trushina, 2017). Simultaneously, ROS excess enhances Aβ accumulation inducing oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, neuronal membranes, and nucleic acids (Cholerton et al., 2011; Chen & Zhong, 2013), contributing to neuronal dysfunction, synaptic loss, and neurodegeneration characteristic of AD (Sharma & Kim, 2021; Dakterzada et al., 2023; Evans et al., 2003);

(d) Mitochondrial dysfunction (

Figure 2). An increasing amount of research shows that mitochondrial dysfunction presents the link between T2MD and AD (Potenza et al., 2021; Carvalho & Moreira, 2023; Sims-Robinson et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2022). Mitochondria are responsible for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, β-oxidation of fatty acids, modification of phospholipids, biosynthesis of metabolites, intracellular calcium buffering and signaling, ROS generation, immune responses, apoptosis, and stem cell reprogramming. Moreover, mitochondria play a critical role in neuronal membrane excitability, neurotransmission, and plasticity (Galizzi & Di Carlo, 2022)

. Altered mitochondrial morphology, distribution and movement, contributes to oxidative stress and synaptic dysfunction (Zuo et al., 2014; Nunomura et al., 2006; Schilling, 2016), impairs brain metabolism as well as mitochondrial biogenesis in AD subjects (Bhatia et al., 2022). Studies suggest that altered mitochondrial quality control contributes to the pathogenesis of T2MD, highlighting the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes-related cognitive impairment (Rovira-Llopis et al., 2017). Mitochondrial dysfunction acts as a trigger for AD pathology, contributing to neuronal dysfunction and neurodegeneration (Moreira et al., 2009). Otherwise, mitochondrial dysfunction may be a consequence of insulin resistance and/or the accumulation of misfolded proteins, such as Aβ-plaques, in AD. The Aβ-plaques and phosphorylated tau contribute to defective autophagy and mitophagy, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction in AD (Reddy & Oliver, 2019); and

(e) Disruption of Glucose and Energy Metabolism. Dysfunction in glucose and energy metabolism is a common feature of both diabetes and AD. Alterations in glucose utilization and the ability to obtain energy from cells may contribute to neurodegeneration and cognitive dysfunction in both diseases (Méndez-Flores et al., 2024; Cunnane et al., 2020). Impaired cerebral glucose metabolism is reported in T2D, and its consequences account for most of the structural and functional anomalies of AD (Berlanga-Acosta et al., 2020).

3. Common Genes Involved in Both Diseases

The differentially expressed genes between AD and T2MD are not highly overlapped, but the functional similarity between them is significantly high when considering Gene Ontology semantic similarity and protein-protein interactions, indicating that AD and T2DM share some common pathways in disease development

(Figure 5 and

Figure 6). An increasing amount of research shows that mitochondrial dysfunction presents the li (Kang et al., 2022).

Common genetic link between the two diseases involves genes related to insulin signaling and glucose metabolism. IDE (Insulin Degrading Enzyme) is responsible for degrading both insulin and Aß-peptides. Dysfunctional IDE activity leads to impaired insulin signaling in T2MD and accumulation of Aß-peptides in AD (Tian et al., 2023; Azam et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2008).

Certain APOE (apolipoprotein E) gene variants (APOE-4) have been linked to increased risk for both diseases (Liu et al., 2013). APOE is involved in lipid metabolism, insulin resistance pathway and β-cell dysfunction in T2MD, as well as in Aß-peptides clearance in AD.

The SLC2A4 gene is a member of the solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter) family and encodes a protein that functions as an insulin-regulated facilitative glucose transporter among other pathways. It has the highest connectivity with GLUT4 and cerebellum, cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, pituitary, astrocytes, neurons and fueling of active synapses (Ardanaz et al., 2022) as well as other differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for both AD and T2DM. Therefore, it is suggested a potential contributor linking T2DM and AD via glucose metabolism related pathways. According to brain studies, most glucose transport is regulated by GLUT1 and GLUT3, but GLUT2 leads specific neuronal populations more vulnerable to pathogenic mechanisms underlying AD (Knezovic et al., 2017).

An association between a variant of HMOX1 and AD has been found (Zhang et al., 2021) as well as has been demonstrated that HMOX1 upregulation is responsible for the increased ferroptosis in diabetic atherosclerosis development (Meng et al., 2021), suggesting that HMOX1 may serve as a potential therapeutic or drug development target for diabetes and AD. High correlation has been found between AD and diabetes based on the existence of 40 common genes (Gholizadeh et al., 2020). Results of analyses revealed 14 genes in AD and 12 genes in diabetes as key genes that regulates many underlying brain mechanisms 7 of which were common including caspase 3 (CASP3), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), catalase (CAT), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), leptin (LEP), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) (Gholizadeh et al., 2020).

It has been concluded that both diseases have the highest effect on NAFLD, which suggests that NAFLD is a key connector disease between these two diseases (Gholizadeh et al., 2020).

In addition, it has identified the following genes common to T2MD and AD: APP (Amyloid Beta Precursor Protein), AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), FTO (fat mass and obesity), PPAR-γ (peroxisome proliferator activated receptorγ), SORCS1 (sortilin-related VPS10, vacuolar protein sorting, domain containing receptor 1), ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 1), VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), and PCK1 (Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase 1) (Ciudin, 2016).

Most of these genes encode proteins involved in both the development of T2DM and AD, but their role in the relationship between the two diseases has yet to be elucidated.

Other shared genetic factors between AD and T2D include genes related to inflammation, mitochondrial function, and lipid metabolism (Yuan et al., 2023). For instance, variants in genes encoding inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α have been associated with increased risk for both diseases (Lyra e Silva et al., 2021). Additionally, genes involved in mitochondrial function and oxidative stress, such as PGC-1α and SIRT1, have been implicated in both pathologies (Veselov et al., 2023). Furthermore, genes related to lipid metabolism, such as PPAR-γ, have been linked to insulin resistance in T2MD and amyloid beta metabolism in AD (Zhong et al., 2023).

There is growing evidence suggesting a shared genetic basis between these two seemingly unrelated diseases. Several genes have been identified that play roles in both AD and T2MD, suggesting common underlying mechanisms. Understanding these shared genetic factors is not only crucial for unraveling the pathophysiology of both diseases but also holds promise for drug repositioning, where drugs developed for one condition may be repurposed for the treatment of the other (Yuan et al., 2023; Boukhalfa et al., 2023; Caputo et al., 2020) .

4. Common Epigenetic Modifications

Epigenetic reprogramming, a dynamic process, predicts the long-term health outcomes of diseases. It involves shifts between healthy and diseased states, governed by intricate epigenetic networks (Abraham, 2023). Three different epigenetic mechanisms have been identified: DNA methylation, histone modification and RNA-associated silencing:

DNA Methylation involved in both AD and T2DM, highlighting their potential implications for disease pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Changes in DNA methylation levels at specific gene promoters influence key pathways such as insulin signaling, inflammation, and Aß metabolism involved, all of them, in both diseases. Methylation analysis has shed light on genes potentially implicated in insulin resistance and AD (Sarnowski et al., 2022). Histone modifications such as in histone acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation have been implicated in AD and T2DM. These alterations can affect chromatin structure and gene expression, influencing processes such as insulin sensitivity, ß-cell function, neuroinflammation, and synaptic plasticity (Lin, Y., 2022; Wu, Y.L., 2023; Park et al., 2022; Geng et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). Dysregulation of MicroRNAs (miRNAs) has been associated with both AD and diabetes (Leoni De Sousa & Improta-Caria, 2022). The miRNAs, small non-coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression, can target genes involved in insulin signaling, Aß metabolism, inflammation, and other pathways relevant to both diseases (Amakiri et al., 2019; Nigi et al., 2018; Das & Rao, 2022). There is an increasing body of evidence demonstrating the role of diabetes-associated chromatin modifications in epigenetic mechanisms and their potential significance in the pathogenesis of diabetes. It suggests that individuals with diabetes may exhibit alterations in the expression of chromatin modification enzymes in the brain compared to those without diabetes. These changes coincide with altered expression of proteins involved in synaptic function, such as synaptophysin, which is indicative of potential synaptic dysfunction. Moreover, similar changes in chromatin modifications and synaptic protein expression are observed in mouse models of T2MD. Importantly, these changes are associated with increased susceptibility to AD neurodegenerative insults, such as Aβ oligomeric and tau protein. This suggests a potential causal link between diabetes-induced epigenetic mechanisms and structural or functional alterations in the brain, which may increase susceptibility to AD-type neurodegenerative insults (Gong et al., 2012). Studies show that diabetes induces epigenetic modifications affecting neuropathological mechanisms leading to increased susceptibility to insults associated with neurodegenerative or vascular impairments, providing an epigenetic explanation for the increased risk of diabetics developing dementia (Wang et al., 2014).

The expressions measurement of epigenetic chromatin modification enzymes in the brains of diabetic patients suggests that epigenetic alterations in histone deacetylases (HDACs) cause decreases in H3 and H4 acetylation at the proximal promoter of pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor 1 (Pdx-1) in pancreatic β-cells, leading to defects in glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance and eventually to T2MD. Similarly, histone modifications of glut4 mediated by DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt) and HDACs result in reduced transcription of GLUT4, contributing to insulin resistance and T2MD development, particularly in intrauterine growth–restricted offspring. Epigenetic alterations in diabetic brains make the brain not only more susceptible to oAβ but also to aberrantly aggregated neurofibrillary tangles made of hyperphosphorylated tau, the other pathological feature of AD. It is also possible that these changes make the brains vulnerable to infarction and small-vessel disease, which may lead to vascular dementia and other insults such as inflammation and AGEs products that are prevalent in diabetes (Wang et al., 2014).

Other study concludes that Diabetes alters acetylation homeostasis via upregulation of HDACs, decreasing memory and synaptic plasticity-related proteins like brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), synaptophysin (SYP), postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95) causing diabetes-associated cognitive decline. Further, the histone deacetylases (HDAC) inhibitors attenuate diabetes-induced memory impairment in T1D and T2D mice. Also, HDAC modulators act as therapeutic targets to reprogram memory-associated impairment in diabetes (Aggarwal et al., 2023).

Overall, this highlights the importance of epigenetic mechanisms, specifically chromatin modifications mediated by HDACs and DNA methyltransferases, in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Understanding these epigenetic alterations may provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying diabetes development and could lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets for T2MD. While these genes and epigenetic modifications are shared between AD and T2MD, their specific roles and contributions to disease pathogenesis may vary. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the relationship between these conditions and to identify potential therapeutic targets for intervention.

Environmental factors like diet and exercise wield significant influence in shaping these epigenetic modifications impacting developmental trajectories and lifelong health outcomes. Unlike changes in DNA sequence, epigenetics governs gene activity, thereby determining phenotype variations despite identical genomes across cells (Kanherkar et al., 2014). Depending on their quality and quantity, diet and exercise can either promote or hinder proper physiological functioning. Therefore, implementing tailored dietary and exercise regimens emerges as a novel approach to modulate epigenetic processes and mitigate the onset or progression of human diseases.

Phytochemical compounds found in plants, particularly fruits and vegetables, have garnered attention since some natural compounds have exhibited promising epigenetic effects. However, there has been limited research on the pleiotropic role of natural products in modifying epigenetic pathways related to brain disorders. Bioactive substances derived from food have the potential to influence both epigenetic processes and their associated targets.

5. Conclusions and Future Research Areas

This first part of the monograph "Relationships between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s Disease" has been dedicated to analyzing the common mechanisms that these two pathologies share. Likewise, special attention was paid to studying the relationships they have both at the onset and in the clinical course of each of them as well as in the T2D + AD complex. This issue is of great global relevance since the number of patients suffering from both pathologies has increased enormously, and continues to increase, in societies that are increasingly aging and where diets and lifestyle are frequently inadequate. The risk factors described clearly lead to a real pathology that in many cases is not perceived as extremely dangerous for the development of T2D and AD: obesity. Many pathological events have been described that underlie the development of these diseases (oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, peripheral inflammation, neuroinflammation, neuroglial dysfunction, neuronal dysfunction) that can define therapeutic targets to prevent or slow the course of these pathologies. In some cases, the relationships are quite clear and have been studied in depth using animal models of these pathologies. In other cases, there are still many doubtful or unclarified points in the pathological mechanisms of each disease or of the T2D-AD complex or in the connections between both pathologies. For example, it would be necessary to answer unquestionably how and why any of these pathological events mentioned, which are also described as being involved in many other diseases, come from T2D, AD or T2D-AD. Genetic and epigenetic studies are providing us with a greater understanding of the altered points of pathogenic mechanisms. In the coming years, we will have a better understanding of these pathologies and will be able to develop new therapies.

Funding

The authors have not received any financial support to carry out this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham, M. J. (2023). Restoring Epigenetic Reprogramming with Diet and Exercise to Improve Health-Related Metabolic Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N. K., Levin, E. C., Clifford, P. M., Han, M., Tourtellotte, R., Chamberlain, D., Pollaro, M., Coretti, N. J., Kosciuk, M. C., & Nagele, E. P. (2013). Diabetes and hypercholesterolemia increase blood-brain barrier permeability and brain amyloid deposition: beneficial effects of the LpPLA2 inhibitor darapladib. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A., Yadav, B., Sharma, N., Kaur, R., & Rishi, V. (2023). Unraveling epigenetic mechanisms causing cognitive dysfunction in experimental diabetes.

- Amakiri, N., Kubosumi, A., Tran, J., & Reddy, P. H. (2019). Amyloid Beta and MicroRNAs in Alzheimer’s Disease. [CrossRef]

- Ardanaz, C. G., Ramírez, M. J., & Solas, M. (2022). Brain Metabolic Alterations in AD.

- Azam, S., Wahiduzzaman, M., Reyad-ul- Ferdous, M., Islam, N., & Roy, M. (2022). Inhibition of Insulin Degrading Enzyme to Control Diabetes Mellitus and its Applications on some Other Chronic Disease: a Critical Review. [CrossRef]

- Berlanga-Acosta, J., Guillén-Nieto, G., Rodríguez-Rodríguez, N., Bringas-Vega, M. L., García-del-Barco-Herrera, D., Berlanga-Saez, J. O., & García-Ojalvo, A. (2020). Insulin Resistance at the Crossroad of AD Pathology: A Review.

- Bhatia, S., Rawal, R., Sharma, P., Singh, T., Singh, M., & Singh, V. (2022). Mitochondrial Dysfunction in AD: Opportunities for Drug Development.

- Bhatti, J. S., Sehrawat, A., Mishra, J., Sidhu, I. S., Navik, U., Khullar, N., & Kumar, S. (2022). Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and related complications: Current therapeutics strategies and future perspectives. [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. (2020). Metabolically Healthy Obesity.

- Bosco, D., Fava, A., Plastino, M., Montalcini, T., & Pujia, A. (2011). Possible implications of insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. [CrossRef]

- Boukhalfa, W., Jmel, H., Kheriji, N., Gouiza, I., Dallal, H., & Hechmi, M. (2023). Decoding the genetic relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes: potential risk variants and future direction for North Africa. [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, A., Domenico, F. D., & Barone, E. (2014). Elevated risk of T2D for development of AD: A key role for oxidative stress in brain.

- Capeau, J. (2008). Insulin resistance and steatosis in humans. [CrossRef]

- Caputo, V., Termine, A., Strafella, C., Giardina, E., & Cascella, R. (2020). Shared (epi)genomic background connecting neurodegenerative diseases and T2D.

- Carvalho, C., & Moreira, P. I. (2023). Metabolic defects shared by Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes: A focus on mitochondria. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Zhong, C. (2013). Decoding AD from perturbed cerebral glucose metabolism: implications for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

- Cholerton, B., Bake, L. D., & Craft, S. (2011). Insulin resistance and pathological brain ageing. [CrossRef]

- Ciudin, A. (2016). Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease: An unforgettable relation | Endocrinología y Nutrición (English Edition).

- Contreras, C., González-García, I., Martínez-Sánchez, N., Seoane-Collazo, P., Jacas, J., Morgan, D. A., Serra, D., & Gallego, R. (2014). Central ceramide-induced hypothalamic lipotoxicity and ER stress regulate energy balance. [CrossRef]

- Cunnane, S. C., Trushina, E., Morland, C., Prigione, A., Casadesus, G., & Andrews, Z. B. (2020). Brain energy rescue: an emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. [CrossRef]

- Dakterzada, F., Jove, M., Cantero, J. L., Pamplona, R., & Pinoll-Ripoll, G. (2023). Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid nonenzymatic protein damage is sustained in AD.

- Das, K., & Rao, V. M. (2022). The Role of microRNAs in Inflammation.

- Evans, J. L., Goldfine, I. D., Maddux, B. A., & Grodsky, G. M. (2003). Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction?

- Fauzi, A., Thoe, E. S., Quan, T. Y., & Yin, A. C. Y. (2023). Insights from insulin resistance pathways: Therapeutic approaches against AD associated DM.

- Flicker, L. (2010). Modifiable lifestyle risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, G., & Di Carlo, M. (2022). Insulin and Its Key Role for Mitochondrial Function/Dysfunction and Quality Control: A Shared Link between Dysmetabolism and Neurodegeneration.

- Geng, H., Chen, H., Wang, H., & Wang, L. (2021). The Histone Modifications of Neuronal Plasticity. [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, E., Khaleghian, A., Seyfi, D. N., & Karbalaei, R. (2020). Showing NAFLD, as a key connector disease between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes via analysis of systems biology.

- Ghosh, S. (2014). Ectopic fat: The potential target for obesity management. [CrossRef]

- Gong, B., Wang, J., & Pasinetti, G. (2012). Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the risk of Alzheimer’s disease among diabetic subjects. [CrossRef]

- González, P., Lozano, P., Ros, G., & Solano, F. (2023). Hyperglycemia and Oxidative Stress: An Integral, Updated and Critical Overview of Their Metabolic Interconnections. [CrossRef]

- Hamzé, R., Delangre, E., Tolu, S., Moreau, M., Janel, N., Bailbé, D., & Movassat, J. (2022). Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s Disease: Shared Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Common Therapeutic Targets. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, X., Ibrahim, M., & Peltzer, N. (2022). Cell death and inflammation during obesity: "Know my methods, WAT(son)".

- Ho, N., Sommers, M. S., & Lucki, I. (2013). Effects of diabetes on hippocampal neurogenesis: links to cognition and depression. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-G., Reynolds, C., Gatz, M., Johansson, B., Palmer, J. C., Gu, H. F., Blennow, K., Kehoe, P. G., & de Faire, U. (2008). Evidence that the gene encoding insulin degrading enzyme influences human lifespan. [CrossRef]

- Houldsworth, A. (2024). Role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders: a review of reactive oxygen species and prevention by antioxidants. [CrossRef]

- Jolivalt, C. G., Hurford, R., Lee, C. A., Dumaop, W., Rockenstein, E., & Masliah, E. (2010). Type-1 diabetes exaggerates features of AD in APP transgenic mice.

- Kang, P., Wang, Z., Qiao, D., Zhang, B., Mu, C., Cui, H., & Li, S. (2022). Dissecting genetic links between AD and T2DM in a systems biology way.

- Kanherkar, R. R., Bhatia-Dey, N., & Csoka, A. B. (2014). Epigenetics across the human lifespan. [CrossRef]

- Knezovic, A., Loncar, A., Homolak, J., Smailovic, U., Barilar, O., Ganoci, L., Bozina, N., Riederer, P., & Salkovic-Petrisic, M. (2017). Rat brain glucose transporter-2, insulin receptor and glial expression are acute targets of intracerebroventricular streptozotocin: risk factors for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease?

- Kwon, H. S., & Koh, S.-H. (2020). Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. H., Cha, M., & Lee, B. H. (2020). Neuroprotective Effect of Antioxidants in the Brain. [CrossRef]

- Leoni De Sousa, R. A., & Improta-Caria, A. C. (2022). Regulation of microRNAs in Alzheimer´s disease, type 2 diabetes, and aerobic exercise training.

- Lin, Y. (2022). Role of Histone Post-Translational Modifications in Inflammatory Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C., Kanekiyo, T., Xu, H., & Bu, G. (2013). Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms, and therapy.

- Llorián-Salvador, M., Cabeza-Fernández, S., Gomez-Sanchez, J. A., & de la Fuente, A. G. (2024). Glial cell alterations in diabetes-induced neurodegeneration. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.-S., Ning, J.-Q., Chen, Z.-Y., Li, W.-J., Zhou, R.-L., Yan, R.-Y., Chen, M.-J., & Ding, L.-L. (2022). The Role of Mitochondrial Quality Control in Cognitive Dysfunction in Diabetes. [CrossRef]

- Lyra e Silva, N. M., Gonçalves, R. A., Pascoal, T. A., Lima-Filho, R. A., França Resende, E. d. P., Vieira, E. L., Teixeira, A. L., de Souza, L. C., & Peny, J. A. (2021). Pro-inflammatory interleukin-6 signaling links cognitive impairments and peripheral metabolic alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Flores, O. G., Hernandez, L., Olivares-Bañuelos, T. N., López-Ramírez, G., & Ortega, A. (2024). Brain energetics and glucose transport in metabolic diseases: role in neurodegeneration. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z., Liang, H., Zhao, J., Gao, J., Liu, C., Ma, X., & Liu, J. (2021). HMOX1 upregulation promotes ferroptosis in diabetic atherosclerosis. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P. I., Carvalho, C., Zhu, X., Smith, M. A., & Perry, G. (2009). Mitochondrial dysfunction is a trigger of Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K., & Kohsaka, S. (2001). Microglia: activation and their significance in the central nervous system. [CrossRef]

- Nigi, L., Grieco, G. E., Ventriglia, G., Brusco, N., Mancarella, F., Formichi, C., Dotta, F., & Sebastiani, G. (2018). MicroRNAs as Regulators of Insulin Signaling: Research Updates and Potential Therapeutic Perspectives in Type 2 Diabetes. [CrossRef]

- Nunomura, A., Castellan, R. J., Zhu, X., Moreira, P. I., Perry, G., & Smith, M. A. (2006). Involvement of Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer Disease. [CrossRef]

- Palavicini, J. P., Chen, J., Wang, C., Wang, J., Qin,, C., Baeuerle, E., & Wang, X. (2020). Early disruption of nerve mitochondrial and myelin lipid homeostasis in obesity-induced diabetes. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Lee, K., Kim, K., & Yi, S.-J. (2022). The role of histone modifications: from neurodevelopment to neurodiseases. [CrossRef]

- Potenza, M. A., Sgarra, L., Desantis, V., Nacci, C., & Montagnani, M. (2021). Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease: Might Mitochondrial Dysfunction Help Deciphering the Common Path? [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rodríguez, J. J., Ortiz, O., Jimenez-Palomares, M., Kay, K. K., Berrocoso, E., Murillo-Carretero, M. I., Spires-Jones, T., Cozar-Castellano, I., Lechuga-Sancho, A. M., & Garcia-Alloza, M. (2013). Differential central pathology and cognitive impairment in pre-diabetic and diabetic mice. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P. H., & Oliver, D. M. (2019). Amyloid Beta and Phosphorylated Tau-Induced Defective Autophagy and Mitophagy in Alzheimer’s Disease. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S. M., & Saltiel, A. R. (2017). Adapting to obesity with adipose tissue inflammation. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Casado, A., Toledano-Díaz, A., & Toledano, A. (2017). Defective Insulin Signalling, Mediated by Inflammation, Connects Obesity to Alzheimer Disease; Relevant Pharmacological Therapies and Preventive Dietary Interventions. [CrossRef]

- Rovira-Llopis, S., Bañuls, C., Diaz-Morales, N., Hernandez-Mijares, A., Rocha, M., & Victor, V. M. (2017). Mitochondrial dynamics in T2D: Pathophysiological implications.

- Sankar, S. B., Infante-Garcia, C., Weinstock, L. D., Ramos-Rodriguez, J. J., Hierro-Bujalance, C., Fernandez-Ponce, C., Wood, L. B., & Garcia-Alloza, M. (2020). Amyloid beta and diabetic pathology cooperatively stimulate cytokine expression in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. [CrossRef]

- Sarnowski, C., Hivert, M.-F., Liu, C., Satizabal, C. L., Lin, H., Beiser, A. S., DeCarli, C. S., DeStefano, A. L., Dupuis, J., Morrison, A. C., & Seshadri, S. (2022). Epigenetic signatures of insulin resistance associated with AD and related traits.

- Sarnowski, C., Huan, T., Ma, Y., Joehanes, R., Beiser, A., DeCarli,, C. S., Heard-Costa, N. L., Levy, D. L., Lin, H., Liu, C., & Meigs, J. B. (2023). Multi-tissue epigenetic analysis identifies distinct associations underlying insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease at CPT1A locus. [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M. A. (2016). Unraveling Alzheimer’s: Making Sense of the Relationship between Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R. (2013). The role of nutrition and diet in AD: a systematic review.

- Sharma, C., & Kim, S. R. (2021). Linking Oxidative Stress and Proteinopathy in AD.

- Sims-Robinson, C., Kim, B., Rosko, A., & Feldman, E. L. (2010). How does diabetes accelerate Alzheimer disease pathology? [CrossRef]

- Smith, U. (2015). Abdominal obesity: a marker of ectopic fat accumulation. [CrossRef]

- Solfrizzi, V., Frisardi, V., Seripa, D., Logroscino, G., Imbimbo, B. P., D’Onofrio, G., Addante, F., Sancarlo, D., Cascavilla, L., Pilotto, A., & Panza, F. (2011). Mediterranean diet in predementia and dementia syndromes. [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, G. D., Bild, V., Ababei, D. C., Rusu, R. N., Cobzaru, A., Paduraru, L., & Bulea, D. (2020). Link between Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease Due to the Shared Amyloid Aggregation and Deposition Involving Both Neurodegenerative Changes and Neurovascular Damages. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Wang, L., Obayomi, B., & Wei, Z. (2021). Epigenetic Regulation of β Cell Identity and Dysfunction. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S., Sato, N., Ikimura, K., Nishino, H., Rakugi, H., & Morishita, R. (2013). Increased blood-brain barrier vulnerability to systemic inflammation in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Jing, G., & Zhang, M. (2023). Insulin-degrading enzyme: Roles and pathways in ameliorating cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. [CrossRef]

- Tong, M., Neusner, A., Longato, L., Lawton, M., Wands, J. R., & M de la Monte, S. (2009). Nitrosamine exposure causes insulin resistance diseases: relevance to type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Tönnies, E., & Trushina, E. (2017). Oxidative Stress, Synaptic Dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Valko, M., Leibfritz, D., Moncol, J., Cronin, M. T., Mazur, M., & Telse, J. (2006). Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. [CrossRef]

- Veselov, I. M., Vinogradova, D. V., Maltsev, A. V., Shevtsov, P. N., Spirkova, E. A., Bachurin, S. O., & Shevtsova, E. F. (2023). Mitochondria and Oxidative Stress as a Link between Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes Mellitus. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Gong, B., Zhao, W., Tang, C., Varghese, M., Nguyen, T., Bi, W., Bilski, A., Begum, S., Vempati, P., Knable, L., Ho, L., & Pasinett, G. M. (2014). Epigenetic Mechanisms Linking Diabetes and Synaptic Impairments. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. H., Hwang, J., Son, S. U., Choi, J., You, S.-W., Park, H., Cha, S.-Y., & Maeng, S. (2023). How Can Insulin Resistance Cause Alzheimer’s Disease? [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T., Yang, T., Chen, H., Fu, D., Hu, Y., Wang, J., Yuan, Q., Yu, H., Xu, W., & Xie, X. (2019). New insights into oxidative stress and inflammation during diabetes mellitus-accelerated atherosclerosis. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X., Wang, H., Zhang, F., Zhang, M., Wang, Q., & Wang, J. (2023). The common genes involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes and their implication for drug repositioning. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Yu, H.-X., Zhi, N., Cui, C., Han, Y.-Y., Hu, M., Shen, H., Bao, H., & Li, G. (2021). Association of HMOX-1 with sporadic AD in southern Han Chinese.

- Zhang, S., Zhang, Y., Wen, Z., Yang, Y., Bu, T., Bu, X., & Ni, Q. (2023). Cognitive dysfunction in diabetes: abnormal glucose metabolic regulation in the brain. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Xiao, D., Mao, Q., & Xia, H. (2023). Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H., Geng, R., Zhang, Y., Ding, J., Liu, M., Deng, S., & Tu, Q. (2023). Effects of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Gamma Agonists on Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W., Zhang, S., Xia, C., Guo, X., He, W., & Chen, N. (2014). Mitochondria autophagy is induced after hypoxic/ischemic stress in a Drp1 dependent manner: The role of inhibition of Drp1 in ischemic brain damage. [CrossRef]

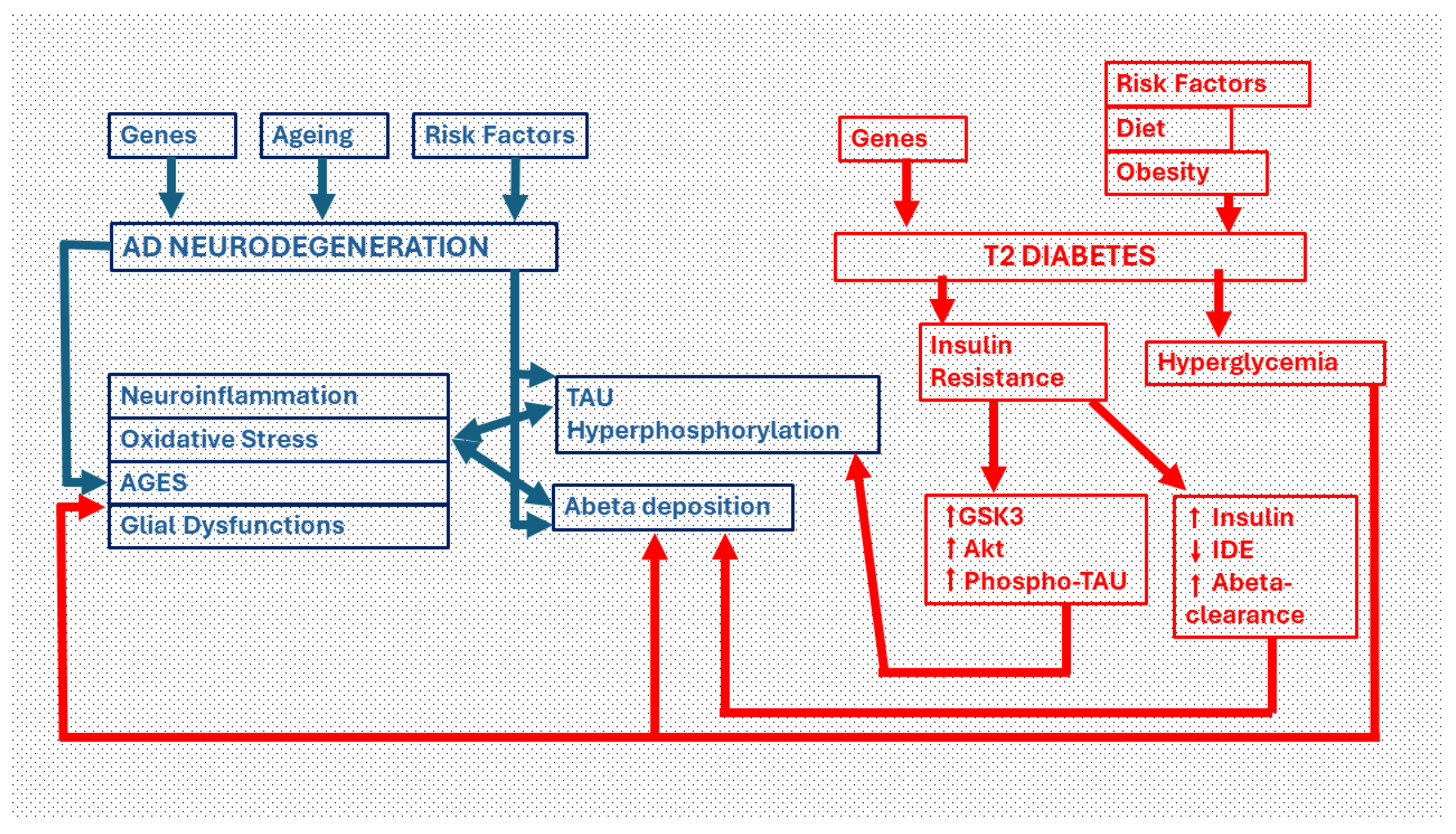

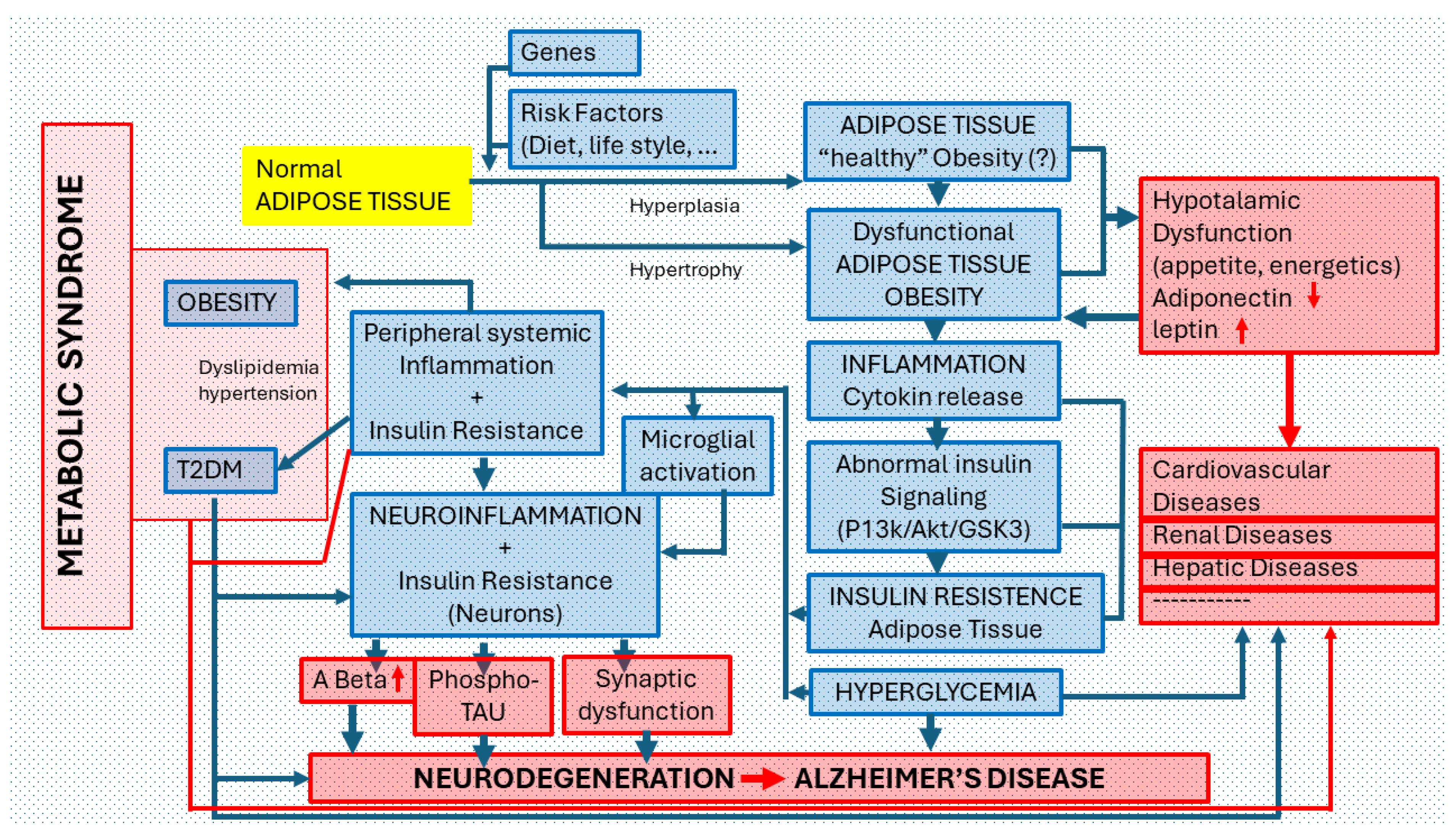

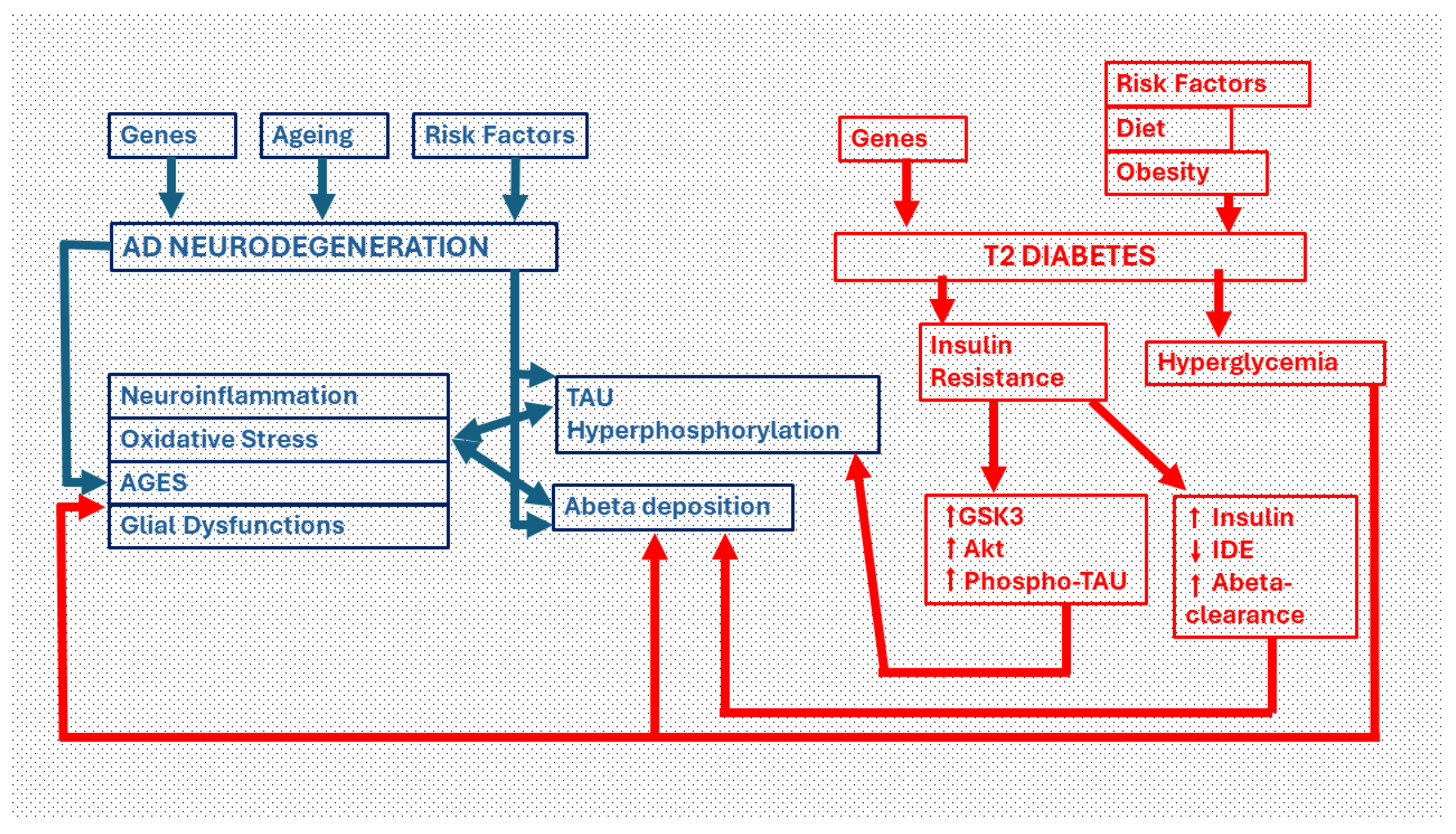

Figure 1.

Pathways of neurodegeneration in the diabetic brain. Critical links between Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and Alzheimer´Disease (AD). The two main neuropathological manifestations in AD are intracellular deposits of phosphorylated TAU protein (which give rise to dysfunctional dystrophic neurites and neurofibrillary tangles) and extracellular deposits of beta-amyloid protein. Both pathways are facilitated by insulin resistance, the major cause of type 2 diabetes. Insulin resistance, through the activation of Akt and GSK3-beta, increases the phosphorylation of the TAU protein. Moreover, through increased insulinemia, the clearance of the beta-amyloid protein decreases by deactivating the insulin degrading enzyme (IDE). On the other hand, hyperglycemia induced by T2DM leads to an overproduction of beta-amyloid protein that is deposited as plaques and/or diffuse amyloid. The chronic hyperglycemia generates advanced glycation end products (AGEs), oxidative stress and neuroinflammation that causes neurodegeneration. Phospho-TAU and Beta amyloid also activate these same neurodegenerative processes.

Figure 1.

Pathways of neurodegeneration in the diabetic brain. Critical links between Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and Alzheimer´Disease (AD). The two main neuropathological manifestations in AD are intracellular deposits of phosphorylated TAU protein (which give rise to dysfunctional dystrophic neurites and neurofibrillary tangles) and extracellular deposits of beta-amyloid protein. Both pathways are facilitated by insulin resistance, the major cause of type 2 diabetes. Insulin resistance, through the activation of Akt and GSK3-beta, increases the phosphorylation of the TAU protein. Moreover, through increased insulinemia, the clearance of the beta-amyloid protein decreases by deactivating the insulin degrading enzyme (IDE). On the other hand, hyperglycemia induced by T2DM leads to an overproduction of beta-amyloid protein that is deposited as plaques and/or diffuse amyloid. The chronic hyperglycemia generates advanced glycation end products (AGEs), oxidative stress and neuroinflammation that causes neurodegeneration. Phospho-TAU and Beta amyloid also activate these same neurodegenerative processes.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Multiple factors are known to cause mitochondrial dysfunction. These factors include DNA mutations and polymorphisms in the mitochondrial genome as well as nuclear mutations in genes producing mitochondrial associated proteins, age involutive processes and increased free fatty acids and/or hyperglycemia (of different origin). Dysfunctional mitochondria produce impaired β-oxidation, reduced ATP, and increased Free Radicals (reactive oxygen and nitrogen species). Moreover, decreased mitochondrial biogenesis can be observed. These events may contribute to obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), insulin resistance and AD in elderly. [Image: cytoplasm of a pyramidal neuron from layer VI of the cerebral frontoparietal cortex (rat) where a high density of mitochondria is observed. 12,000 x].

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Multiple factors are known to cause mitochondrial dysfunction. These factors include DNA mutations and polymorphisms in the mitochondrial genome as well as nuclear mutations in genes producing mitochondrial associated proteins, age involutive processes and increased free fatty acids and/or hyperglycemia (of different origin). Dysfunctional mitochondria produce impaired β-oxidation, reduced ATP, and increased Free Radicals (reactive oxygen and nitrogen species). Moreover, decreased mitochondrial biogenesis can be observed. These events may contribute to obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), insulin resistance and AD in elderly. [Image: cytoplasm of a pyramidal neuron from layer VI of the cerebral frontoparietal cortex (rat) where a high density of mitochondria is observed. 12,000 x].

Figure 3.

The T2 Diabetic brain. The brain in T2D undergoes a neurodegenerative process similar to that observed in AD. The neuroinflammation that it manifests is considered a result of the inflammation suffered by peripheral tissues that gives rise to T2D. In the first phase, cytokines (CYTOKINS) from activated macrophages, as well as cytokines, saturated fatty acids (SFA) and advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) produced in pathological peripheral tissues, cross the blood-brain barrier (normal BBB) initiating the neuroinflammatory process (left panel) by activating microglia cells and modifying functions of astroglia and neurons. The local inflammatory response may initially be protective, but if it persists it becomes neurotoxic. In a second phase (right panel), the integrity of the blood-brain barrier is lost (dysfunc BBB), making the brain highly vulnerable to imbalances in the peripheral inflammatory system. SFA, AGEs and Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6) cross in a very high concentration the dysfunctional BBB (dysfunc BBB) activating microglia and causing neuroglial and neuronal dysfunctions typical of AD. [small arrows = [transition from normal cells to reactive cells (astroglia and microglia) and from normal neurons to dystrophic neurons].

Figure 3.

The T2 Diabetic brain. The brain in T2D undergoes a neurodegenerative process similar to that observed in AD. The neuroinflammation that it manifests is considered a result of the inflammation suffered by peripheral tissues that gives rise to T2D. In the first phase, cytokines (CYTOKINS) from activated macrophages, as well as cytokines, saturated fatty acids (SFA) and advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) produced in pathological peripheral tissues, cross the blood-brain barrier (normal BBB) initiating the neuroinflammatory process (left panel) by activating microglia cells and modifying functions of astroglia and neurons. The local inflammatory response may initially be protective, but if it persists it becomes neurotoxic. In a second phase (right panel), the integrity of the blood-brain barrier is lost (dysfunc BBB), making the brain highly vulnerable to imbalances in the peripheral inflammatory system. SFA, AGEs and Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6) cross in a very high concentration the dysfunctional BBB (dysfunc BBB) activating microglia and causing neuroglial and neuronal dysfunctions typical of AD. [small arrows = [transition from normal cells to reactive cells (astroglia and microglia) and from normal neurons to dystrophic neurons].

Figure 4.

Relationship of Obesity with Alzheimer’s disease. Possible association pathways and pathogenic mechanisms. Under normal conditions, each individual has specific peripheral areas of adipose tissue made up of adipocytes (cells responsible for accumulating fat and regulating blood glucose and lipids). The number of adipocytes is determined from the prenatal period until adolescence and subsequently stabilizes. Due to GENETIC FACTORS or the effect of RISK FACTORS (INADEQUATE DIET OR LIFESTYLE), NORMAL ADIPOSE TISSUE can increase in volume in its normal areas of location or appearing in other peripheral areas (ectopic adipose tissue -or fat). Adipocytes can increase in number (hyperplasia) or size (hypertrophy). This anomaly is called OBESITY. Some authors consider that “healthy obesity” can exist without inducing pathological changes in the body; most deny it. Highly hypertrophic adipocytes are generally dysfunctional. Obesity, as a pathological process (DYSFUNCTIONAL ADIPOSE TISSUE), is accompanied by low-grade chronic INFLAMMATION that causes abnormalities in the INSULIN SIGNALING PATHWAY and favors the appearance of a state of INSULIN RESISTANCE in the adipose tissue and HYPERGLYCEMIA in the body. In this pathological scenario, different processes of PERIPHERAL SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATION + INSULIN RESISTANCE (renal, liver, muscle) but also of the CNS can occur. In the first case, localized pathological disorders can be induced in certain organs or systems (cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, etc.) or generalized disorders such as the so-called Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) or the so-called METABOLIC SYNDROME (in which OBESITY, T2D, Dyslipidemia and Hypertension coexist). In the case of CNS involvement, after MICROGLIAL ACTIVATION, a process of NEUROINFLAMMATION AND NEURONAL CHANGES DUE TO INSULIN RESISTANCE are triggered that increase beta amyloid and phospho-TAU deposits along with synaptic dysfunction, all signs of neurodegeneration, typical of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Insulin Resistance is a metabolic disorder in which cells do not recognize insulin. An insulin-resistant cell does not admit glucose inside, so the blood glucose level increases (hyperglycemia), which in turn stimulates the overproduction of insulin (hyperinsulinemia) in the pancreas, which, over time, leads the body to develop a T2D.

Figure 4.

Relationship of Obesity with Alzheimer’s disease. Possible association pathways and pathogenic mechanisms. Under normal conditions, each individual has specific peripheral areas of adipose tissue made up of adipocytes (cells responsible for accumulating fat and regulating blood glucose and lipids). The number of adipocytes is determined from the prenatal period until adolescence and subsequently stabilizes. Due to GENETIC FACTORS or the effect of RISK FACTORS (INADEQUATE DIET OR LIFESTYLE), NORMAL ADIPOSE TISSUE can increase in volume in its normal areas of location or appearing in other peripheral areas (ectopic adipose tissue -or fat). Adipocytes can increase in number (hyperplasia) or size (hypertrophy). This anomaly is called OBESITY. Some authors consider that “healthy obesity” can exist without inducing pathological changes in the body; most deny it. Highly hypertrophic adipocytes are generally dysfunctional. Obesity, as a pathological process (DYSFUNCTIONAL ADIPOSE TISSUE), is accompanied by low-grade chronic INFLAMMATION that causes abnormalities in the INSULIN SIGNALING PATHWAY and favors the appearance of a state of INSULIN RESISTANCE in the adipose tissue and HYPERGLYCEMIA in the body. In this pathological scenario, different processes of PERIPHERAL SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATION + INSULIN RESISTANCE (renal, liver, muscle) but also of the CNS can occur. In the first case, localized pathological disorders can be induced in certain organs or systems (cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, etc.) or generalized disorders such as the so-called Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) or the so-called METABOLIC SYNDROME (in which OBESITY, T2D, Dyslipidemia and Hypertension coexist). In the case of CNS involvement, after MICROGLIAL ACTIVATION, a process of NEUROINFLAMMATION AND NEURONAL CHANGES DUE TO INSULIN RESISTANCE are triggered that increase beta amyloid and phospho-TAU deposits along with synaptic dysfunction, all signs of neurodegeneration, typical of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Insulin Resistance is a metabolic disorder in which cells do not recognize insulin. An insulin-resistant cell does not admit glucose inside, so the blood glucose level increases (hyperglycemia), which in turn stimulates the overproduction of insulin (hyperinsulinemia) in the pancreas, which, over time, leads the body to develop a T2D.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).