Submitted:

08 May 2024

Posted:

10 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. What We Have Learned of Peripheral Nerve Myelination from Autoradiographic Studies

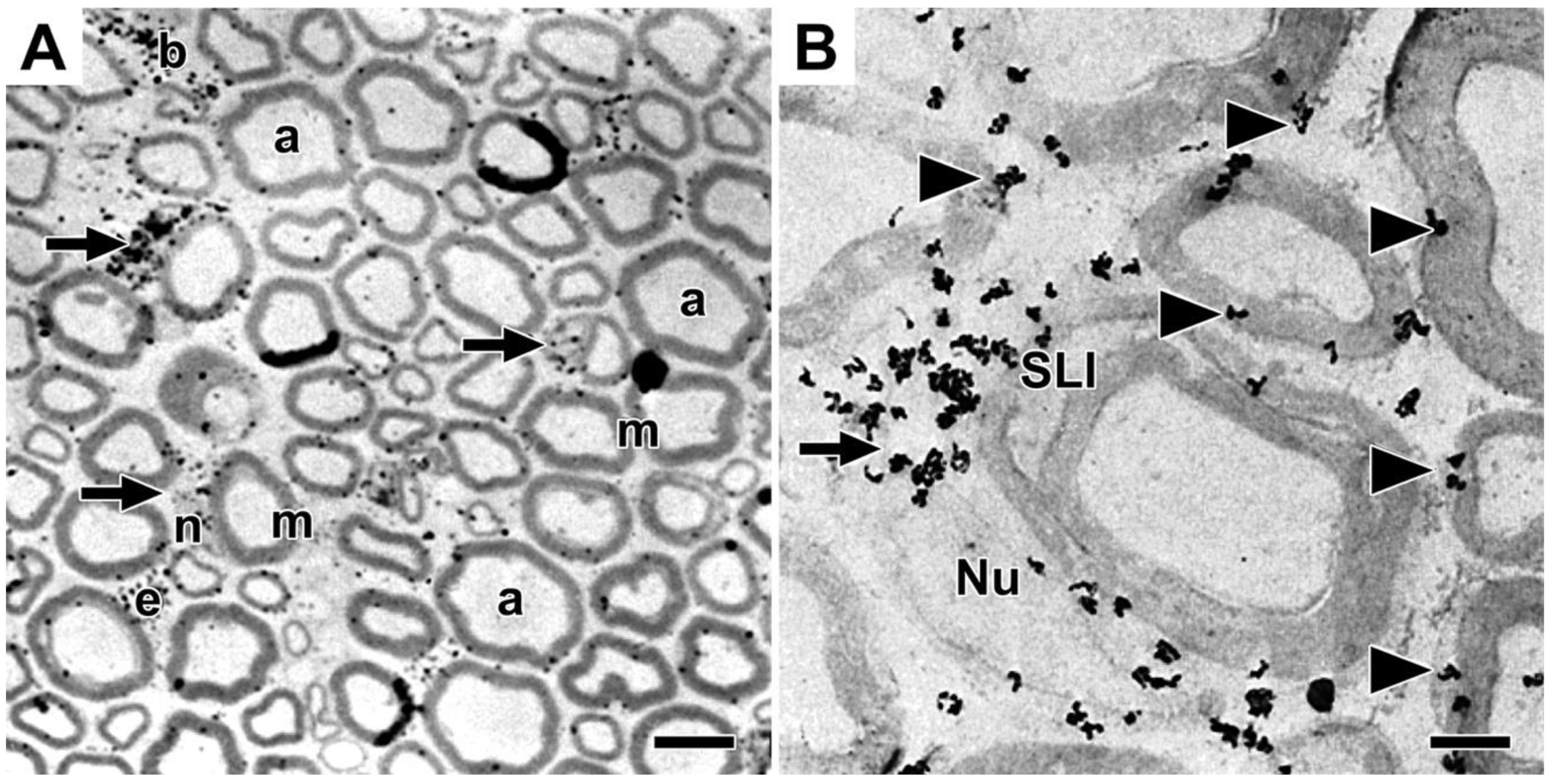

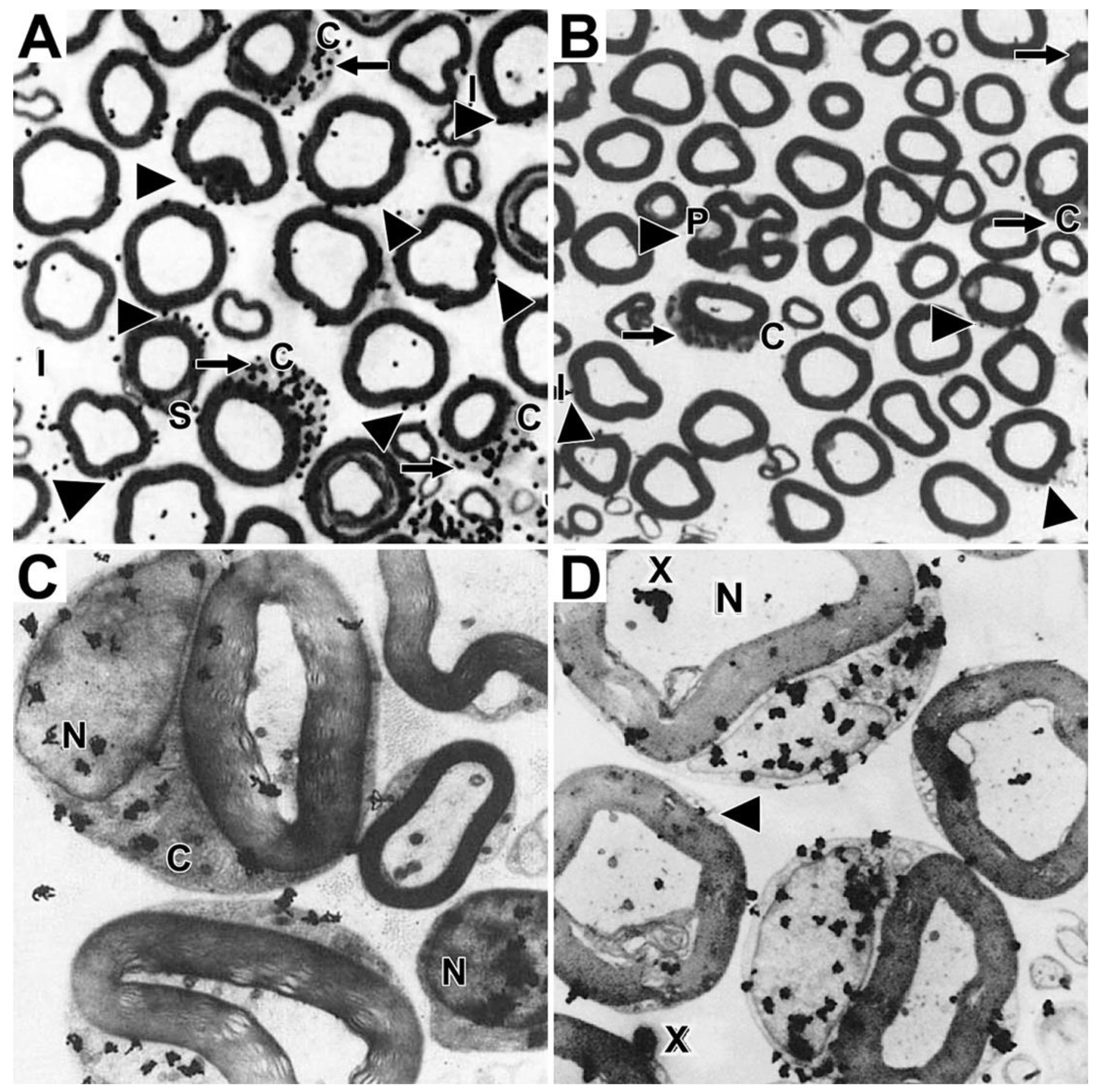

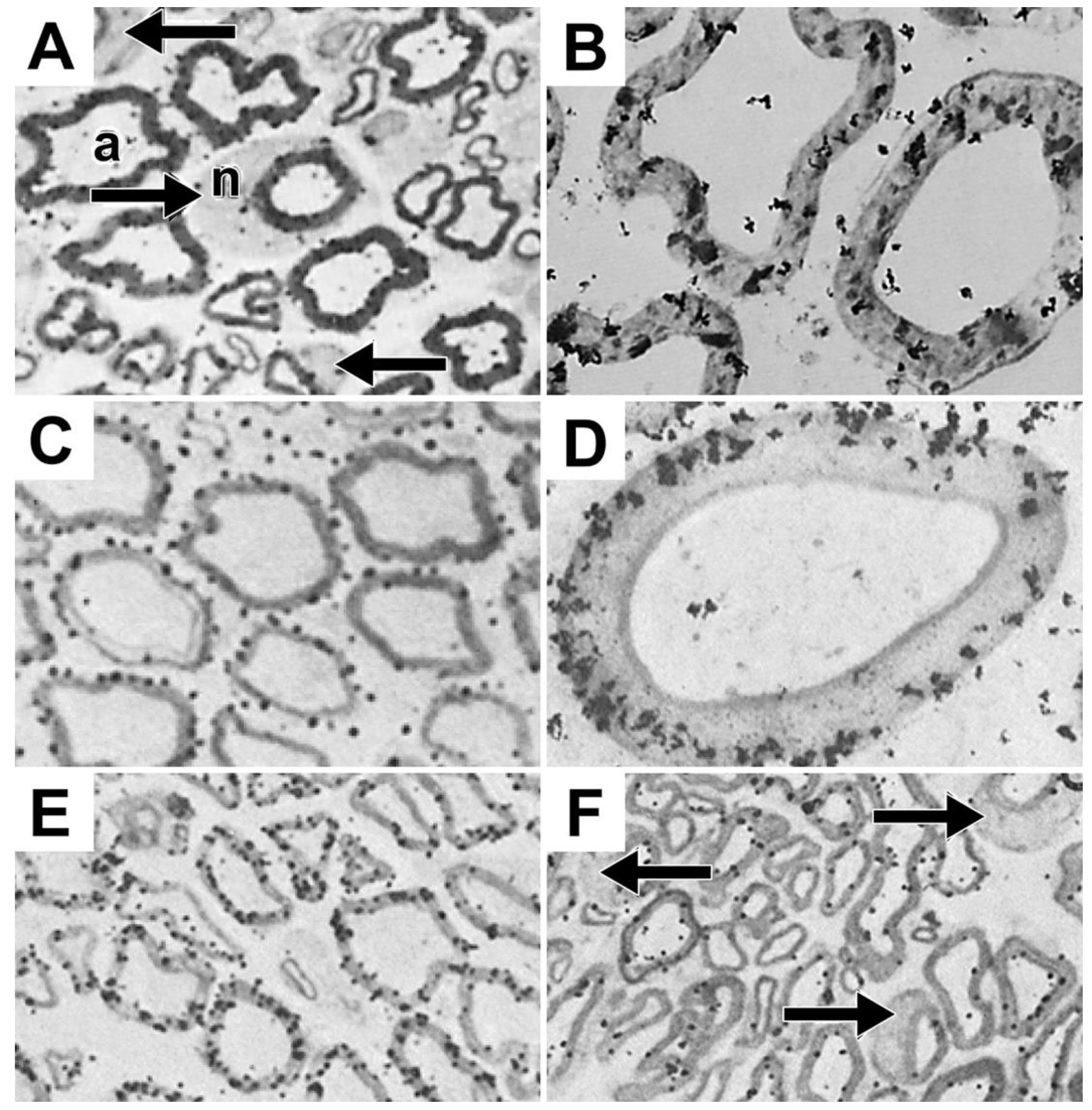

2.1. Identifying Sites Where Myelinating Schwann Cells Synthesize Phospholipids

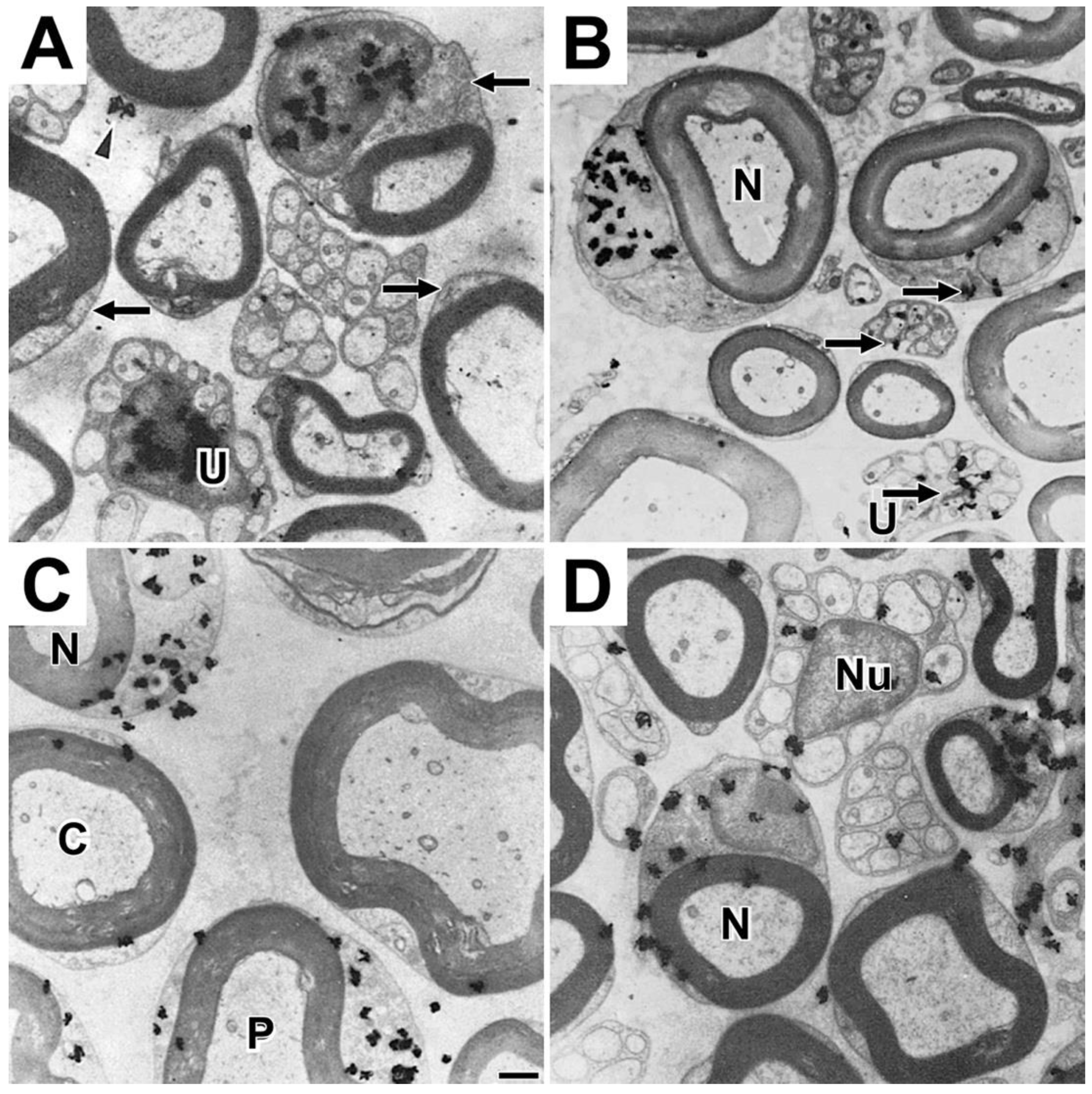

2.2. Identifying Sites Where Myelinating Schwann Cells Synthesize Proteins and Glycoproteins

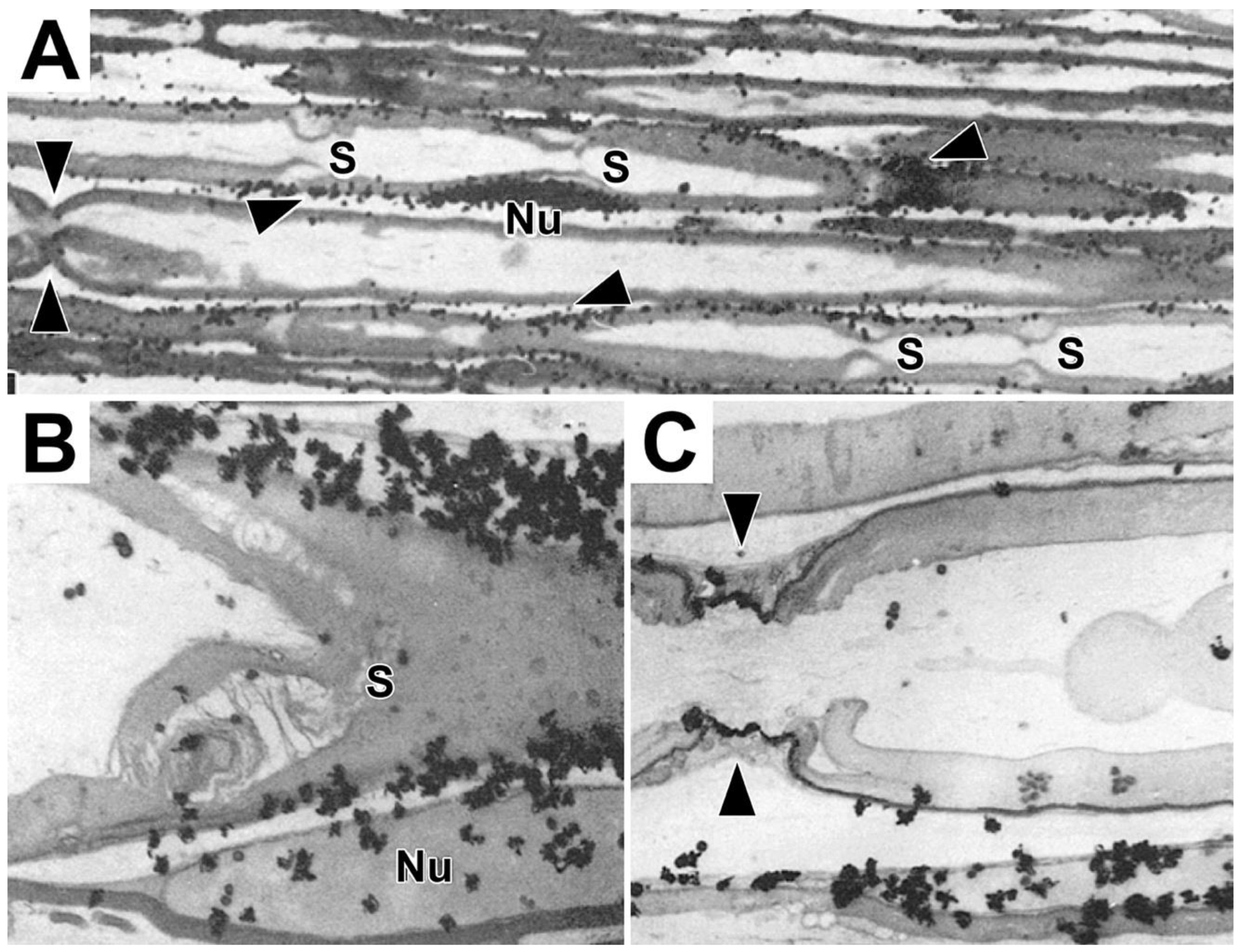

2.3. Synthesis and Transport of RNAs by Myelinating Schwann Cells

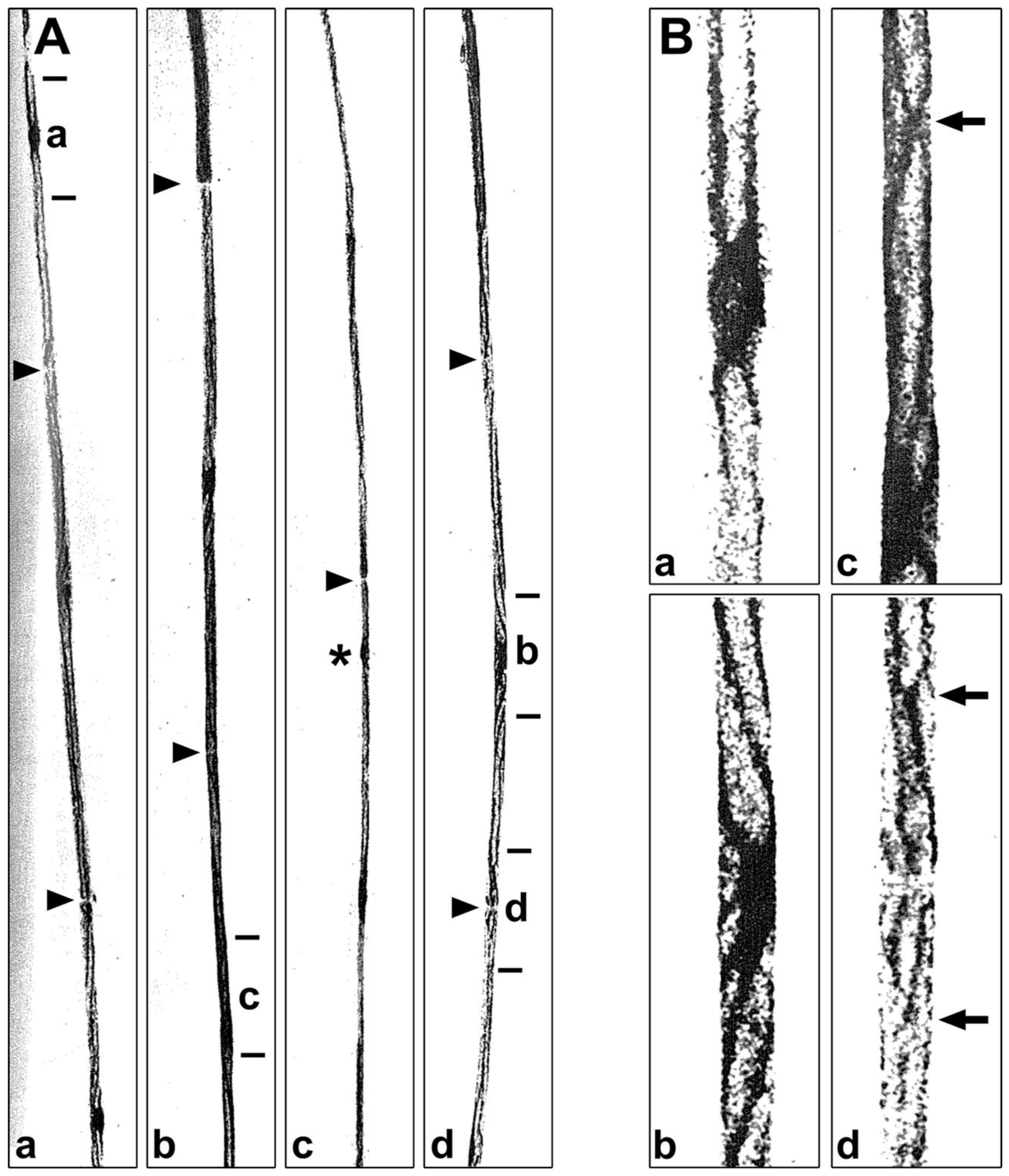

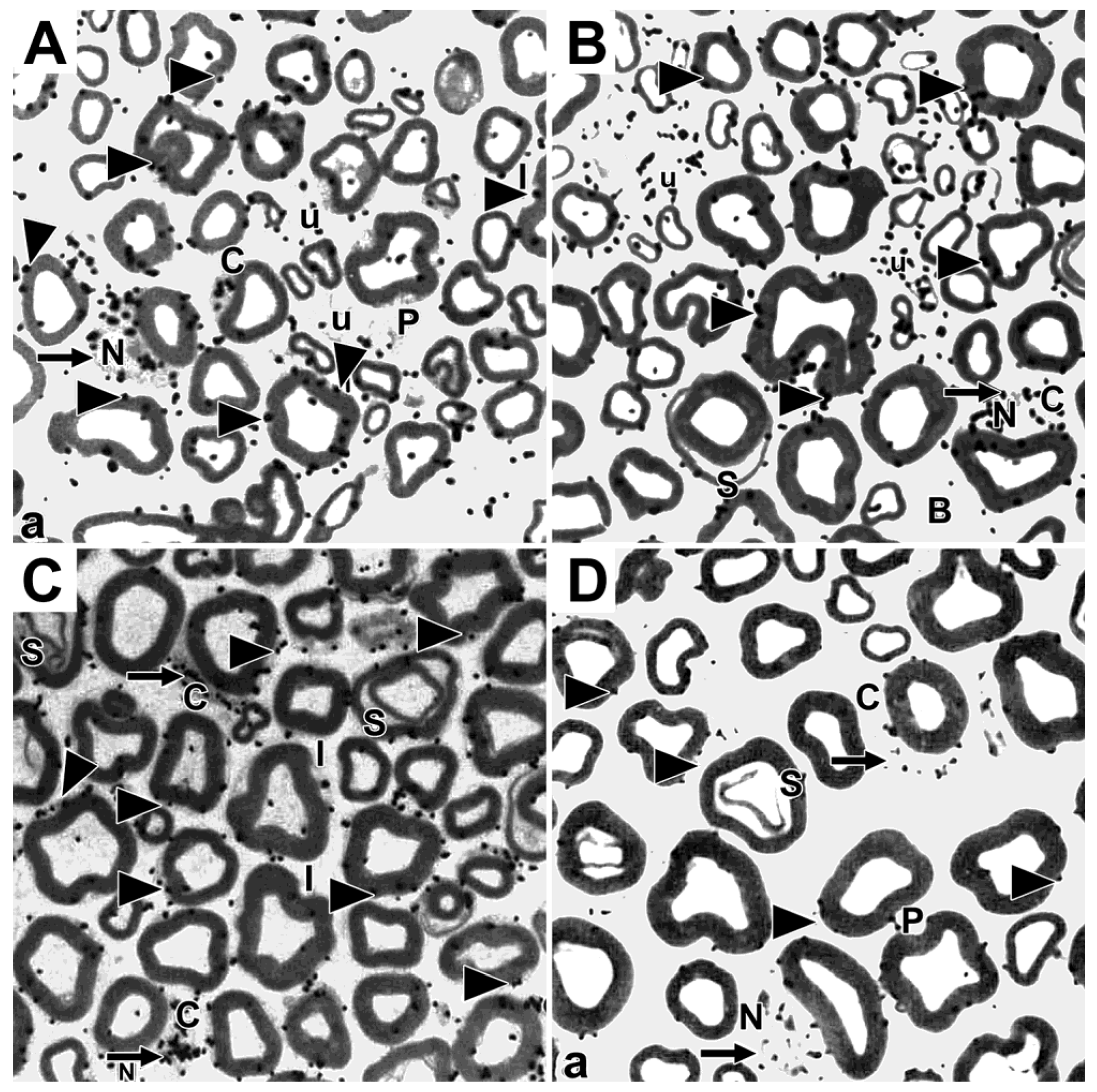

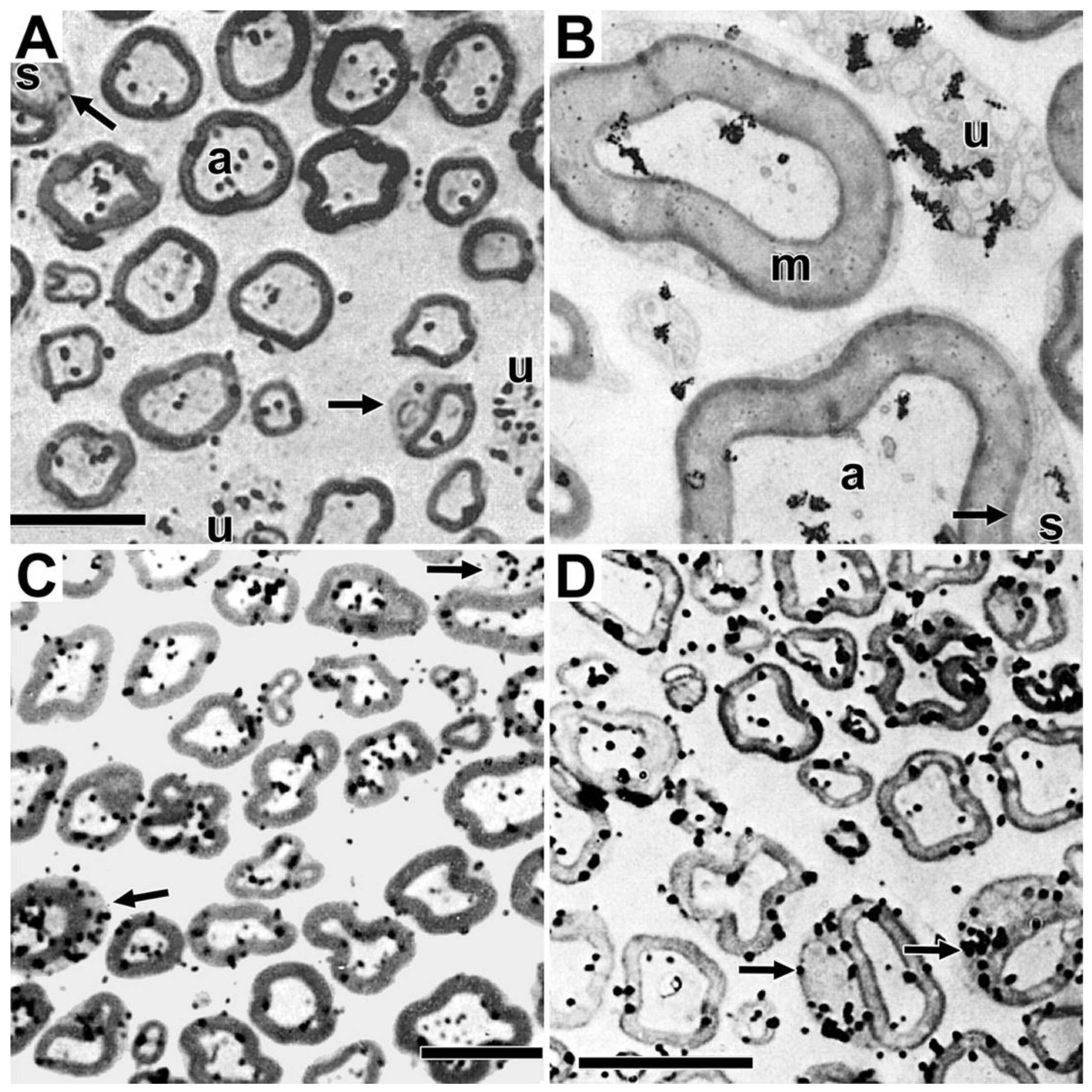

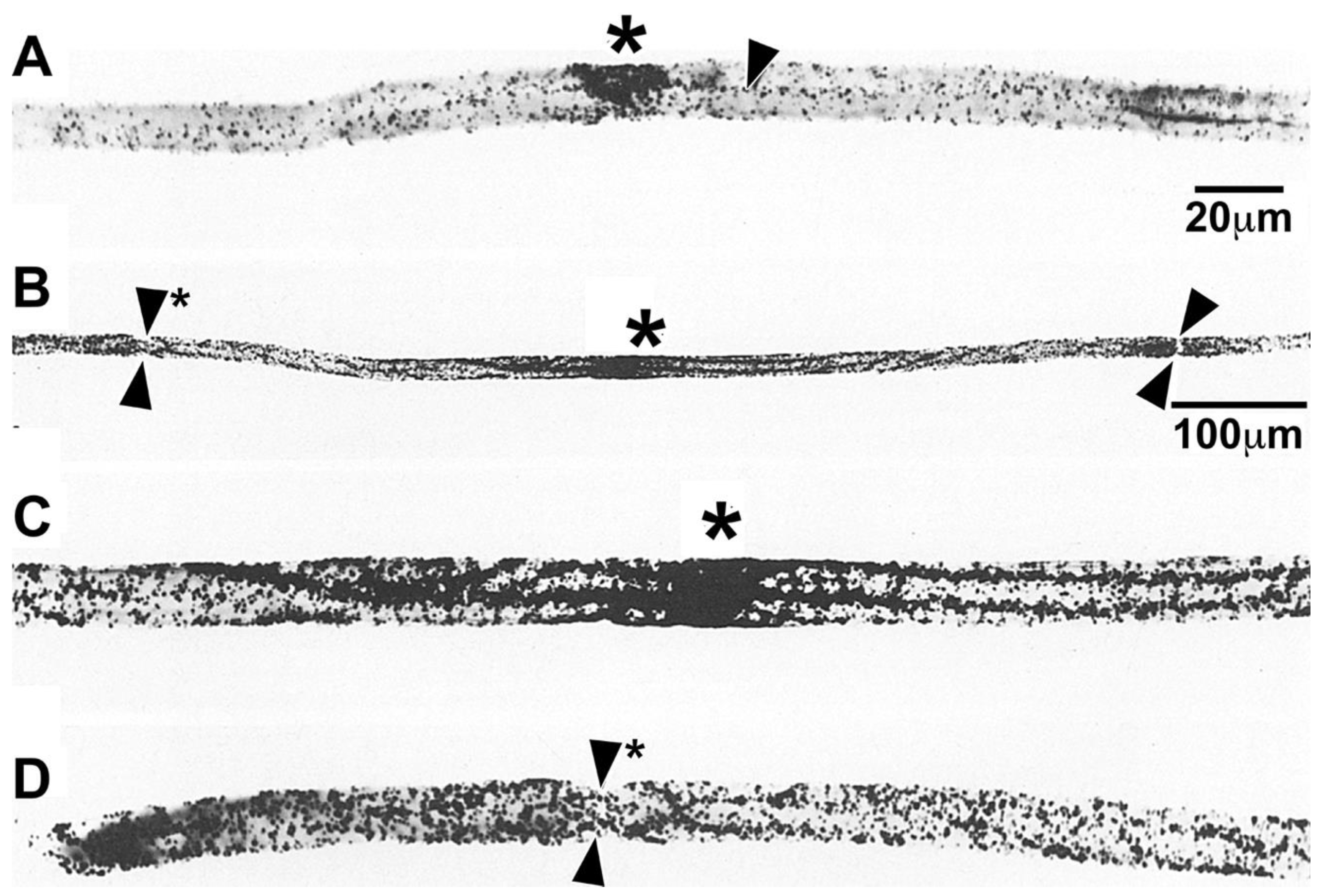

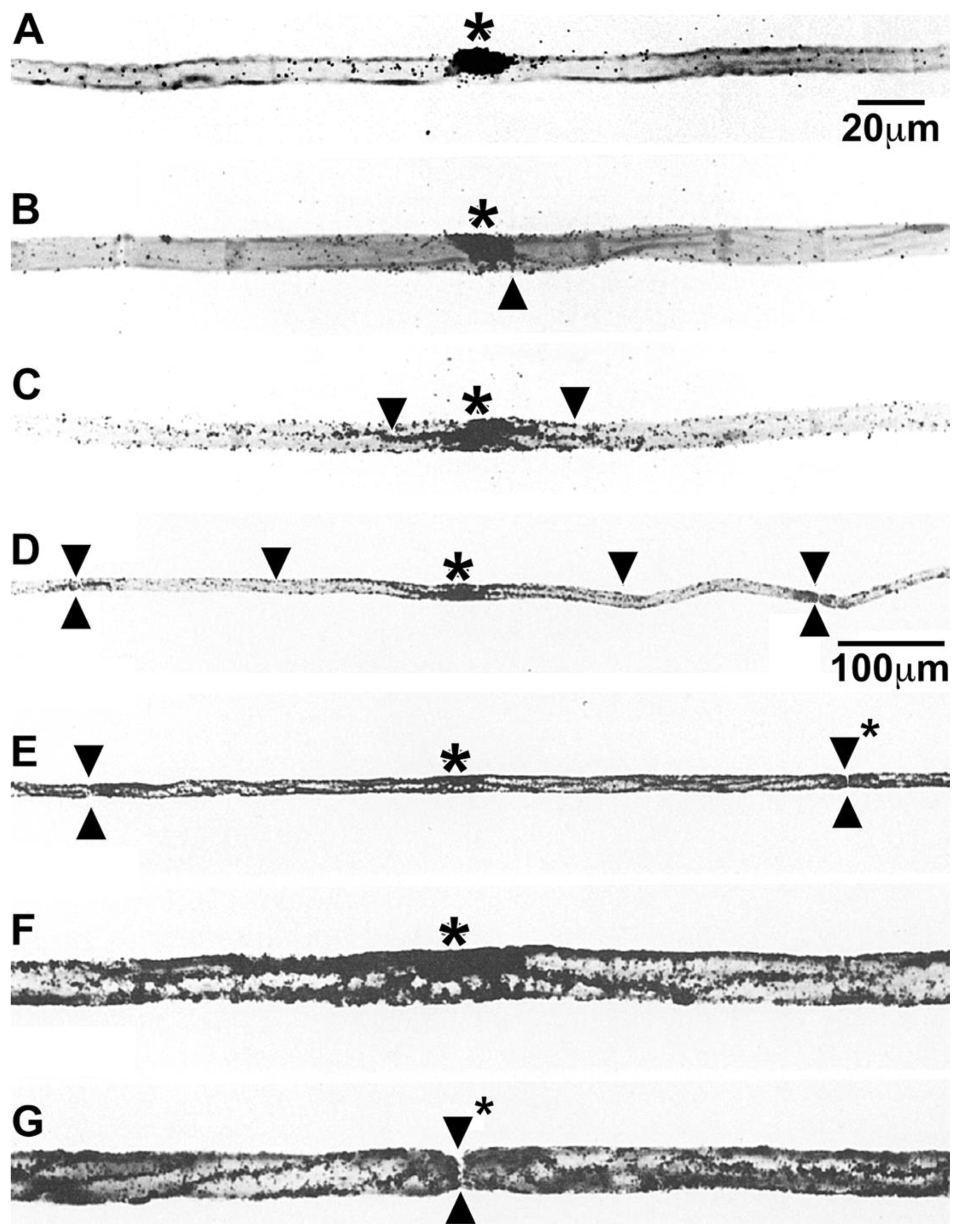

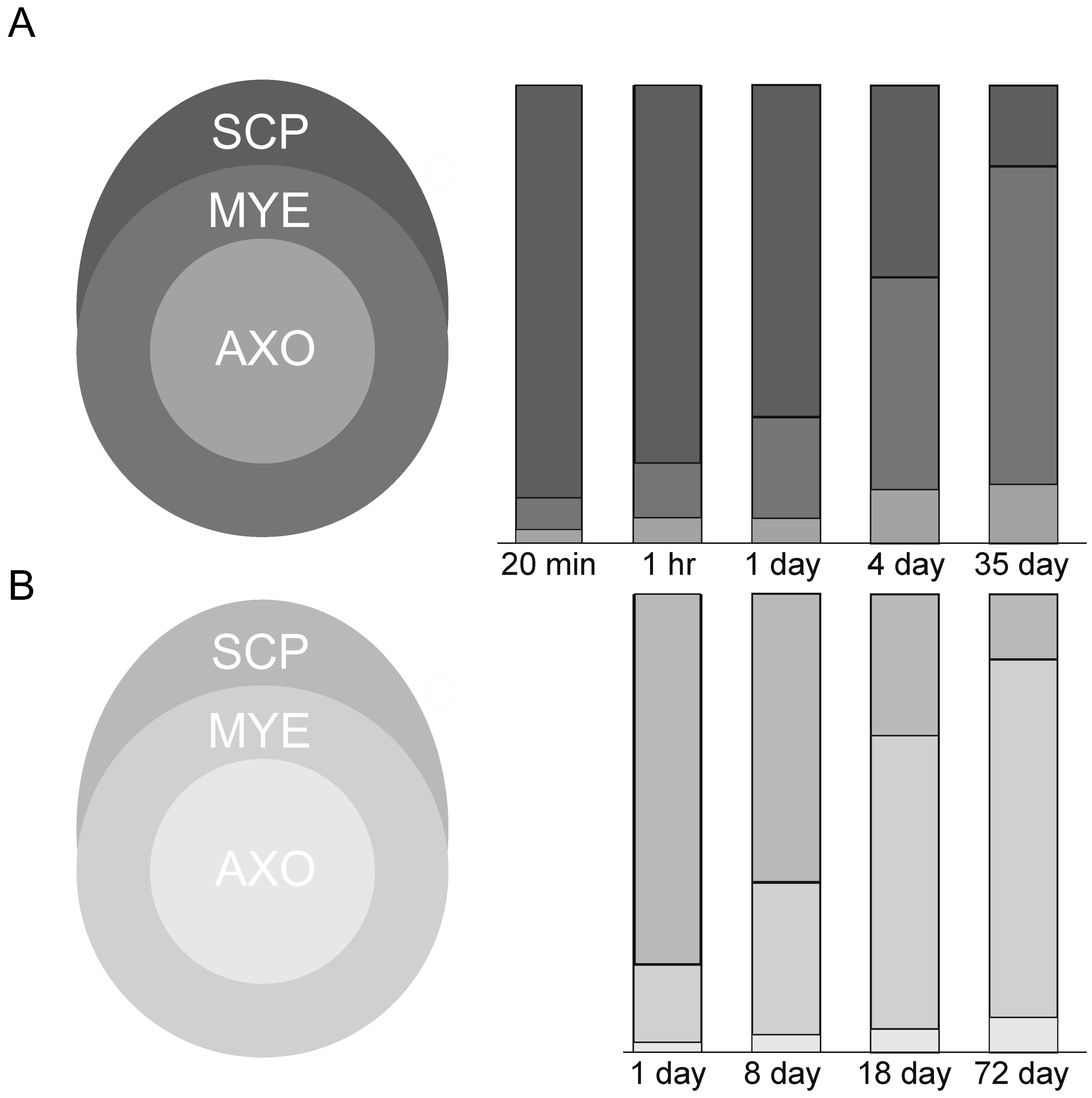

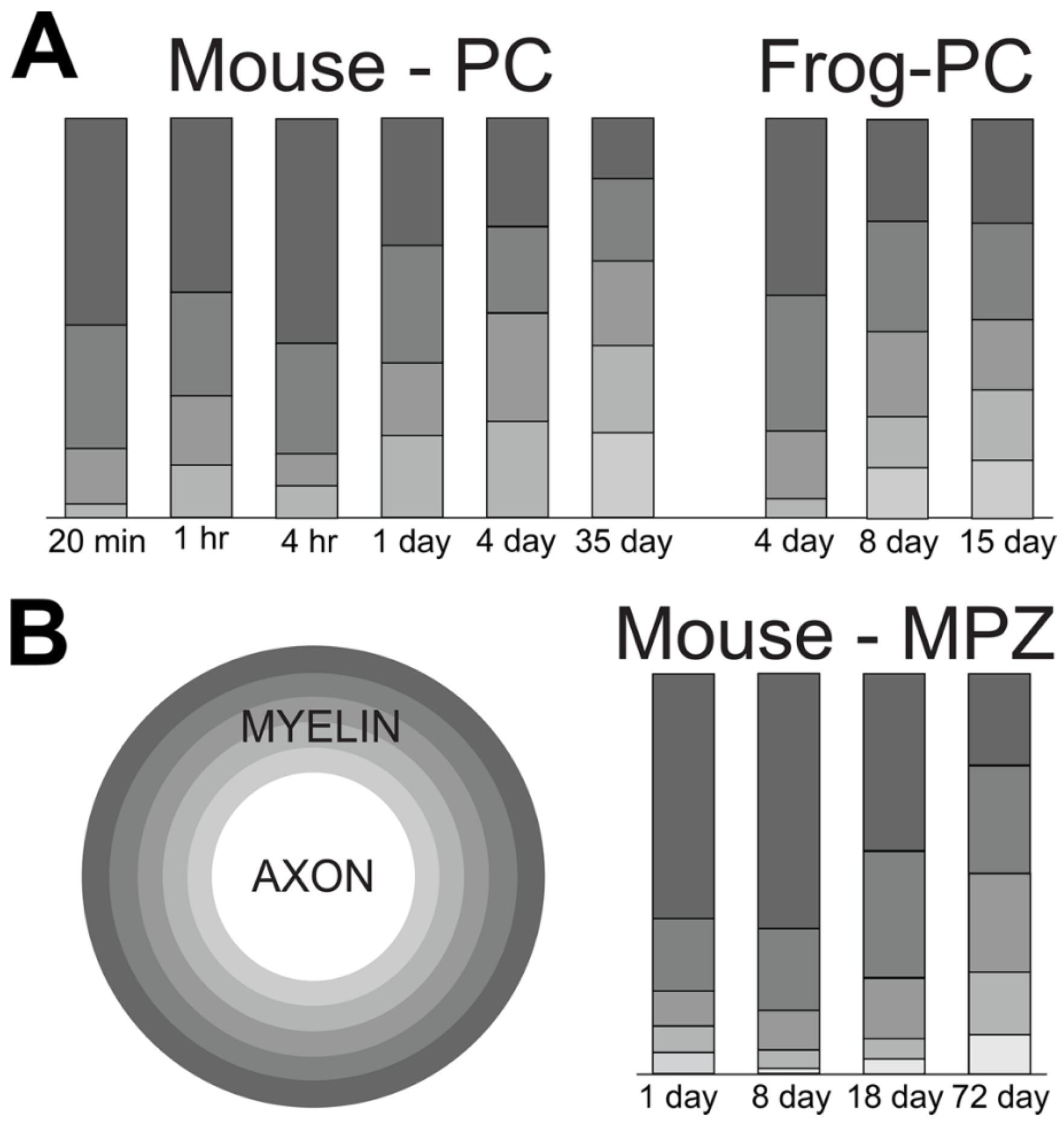

2.4. Movements of Phosphatidylcholine into Myelin Sheaths

2.5. Movements of Fucose-Labeled Glycoproteins into Myelin Sheaths

3. Proposed Follow-up Studies

3.1. Additional Autoradiographic Studies That Are Likely to Broaden Understanding of Peripheral Nerve Myelination

3.2. Identifying Sites of Synthesis and Movement of Myelin-Destined Lipids and Proteins during CNS Myelination

3.3. Novel Approaches to Identify Sites Where Myelinating Cells Synthesize Proteins and Lipids, and to Characterize Their Movements to Myelin, and for Proteins to Other Internodal Locations

3.3.1. Use Noncanonical/Bio-Orthogonal Precursors to Identify Sites of Phosphatidylcholine, Phosphatidylinositol, Protein and Glycoprotein Syntheses Occur in Myelinating Schwann Cells

3.3.2. Using the Bio-Orthogonal Precursor Approach to Follow Movements of Phospholipids, Proteins and Glycoproteins into PNS and CNS Myelin Sheaths

3.3.3. Using Genetic Code Expansion to Identify Sites Where Proteins of Interest Are Synthesized and to Follow Movements from These Sites to Sites of Residence

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benjamins, J.A.; Gray, M.; Morell, P. Metabolic relations between myelin subfractions: entry of proteins. Journal of Neurochemistry 1976, 27, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colman, D.R.; Kreibich, G.; Frey, A.B.; Sabatini, D.D. Synthesis and incorporation of myelin polypeptides into CNS myelin. Journal of Cell Biology 1982, 95, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussbaum, J.L.; Roussel, G. Immunocytochemical demonstration of the transport of myelin proteolipids through the Golgi apparatus. Cell Tissue Res 1983, 234, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, B.D.; Moench, M.; Pulley, E.; Barbosa, E.; Tennekoon, G.I.; Griffin, J. Spatial segregation of mRNA encoding myelin-specific proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USAl.Acad.Sci.USA 1987, 84, 7773–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaport, R.N.; Benjamins, J.A. Kinetics of entry of P 0 protein into peripheral nerve myelin. Journal of Neurochemistry 1981, 37, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, B.D.; Hauer, P.; Lemke, G. Axonal regulation of myelin protein mRNA levels in actively myelinating Schwann cells. Journal of Neuroscience 1988, 8, 3515–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, I.R.; Mitchell, L.S.; McPhilemy, K.; Morrison, S.; Kyriakides, E.; Barrie, J.A. Expression of myelin protein genes in Schwann cells. Journal of Neurocytology 1989, 18, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M.; Holshek, J.; Silverman, W.; Spivack, W. Localization of phospholipid synthesis to Schwann cells and axons. Journal of Neurochemistry 1987, 48, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M.; Mattingly, G. Regional localization of RNA, protein and lipid metabolism in Schwann cells in vivo. Journal of Neurocytology 1990, 19, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.M.; Freund, C.M.; Palmer, F.; Feinstein, D.L. Messenger RNAs located at sites of myelin assembly. Journal of Neurochemistry 2000, 75, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, A.; Schaeren-Wiemers, N.; Schaefer, C.; Pott, U.; Colello, R.J.; Schwab, M.E. Molecular and developmental characterization of novel cDNAs of the myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein. Journal of Neuroscience 1996, 16, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.; Brady, S. Identifying mRNAs Residing in Myelinating Oligodendrocyte Processes as a Basis for Understanding Internode Autonomy. Life (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waehneldt, T.V. Phylogeny of myelin proteins. Ann.NY Acad.Sci. 1990, 605, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M.; Oakley, T.; Goldstone, J.V.; Dugas, J.C.; Brady, S.T.; Gow, A. Myelin sheaths are formed with proteins that originated in vertebrate lineages. Neuron Glia Biol 2008, 4, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, J.S.; Sampson, E.L.; Stern, M.B. Lipid composition of myelin from the peripheral nervous system. Intradural spinal roots. J Neurochem 1967, 14, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacBrinn, M.C.; O'Brien, J.S. Lipid composition of optic nerve myelin. J Neurochem 1969, 16, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.S.; Sampson, E.L. Lipid composition of the normal human brain: gray matter, white matter, and myelin. Journal of Lipid Research 1965, 6, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Palavicini, J.P.; Han, X. Lipidomics Profiling of Myelin. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1791, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermenati, G.; Mitro, N.; Audano, M.; Melcangi, R.C.; Crestani, M.; De Fabiani, E.; Caruso, D. Lipids in the nervous system: from biochemistry and molecular biology to patho-physiology. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1851, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.M.; Dawson, R.M.C. Incorporation of newly formed lecithin into peripheral nerve myelin. Journal of Cell Biology 1976, 68, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.M.; Sinatra, R.S. Internodal distribution of phosphatidylcholine biosynthetic activity in teased peripheral nerve fibers: An autoradiographic study. Journal of Neurocytology 1981, 10, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.M. Inositol lipid synthesis localized in axons and unmyelinated fibers of peripheral nerve. Brain Research 1976, 117, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremser, C.; Klemm, A.L.; van Uelft, M.; Imgrund, S.; Ginkel, C.; Hartmann, D.; Willecke, K. Cell-type-specific expression pattern of ceramide synthase 2 protein in mouse tissues. Histochem Cell Biol 2013, 140, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Palay, S.L.; Webster, H.d. The fine structure of the nervous system: Neurons and their supporting cells; Oxford University Press: New York, 1991; pp. 3–494. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, O.; Arnold, G.; Holtzman, E. Microperoxisome distribution in the central nervous system of the rat. Brain Res 1976, 117, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassmann, C.M. Myelin peroxisomes - essential organelles for the maintenance of white matter in the nervous system. Biochimie 2014, 98, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, N.; Rinholm, J.E. Mitochondria in Myelinating Oligodendrocytes: Slow and Out of Breath? Metabolites 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinholm, J.E.; Vervaeke, K.; Tadross, M.R.; Tkachuk, A.N.; Kopek, B.G.; Brown, T.A.; Bergersen, L.H.; Clayton, D.A. Movement and structure of mitochondria in oligodendrocytes and their myelin sheaths. Glia 2016, 64, 810–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, D.S.; Lin, Y.H.; Khan, D.; Gothie, J.M.; de Faria, O., Jr.; Dixon, J.A.; McBride, H.M.; Antel, J.P.; Kennedy, T.E. Mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics regulated by netrin-1 in oligodendrocytes. Glia 2021, 69, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, S.; Cantuti Castelvetri, L.; Simons, M. Metabolism and functions of lipids in myelin. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1851, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.K.; Dawson, R.M.C. Can mitochondria and synaptosomes of guinea-pig brain synthesize phospholipids? Biochemical Journal 1972, 126, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.N.; Peters, A. The biochemistry of the myelin sheath. In Myelination, Charles C. Thomas: Springfield,IL, 1970; pp. 80–161.

- Hendelman, W.J.; Bunge, R.P. Radioautographic studies of choline incorporation into peripheral nerve myelin. J Cell Biol 1969, 40, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, O.; Stein, Y. LIPID SYNTHESIS, INTRACELLULAR TRANSPORT, AND STORAGE : III. Electron Microscopic Radioautographic Study of the Rat Heart Perfused with Tritiated Oleic Acid. J Cell Biol 1968, 36, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, O.; Stein, Y. Lipid synthesis, intracellular transport, and secretion. II. Electron microscopic radioautographic study of the mouse lactating mammary gland. J Cell Biol 1967, 34, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, O.; Stein, Y. Lipid synthesis, intracellular transport, storage, and secretion. I. Electron microscopic radioautographic study of liver after injection of tritiated palmitate or glycerol in fasted and ethanol-treated rats. J Cell Biol 1967, 33, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Court, F.A.; Sherman, D.L.; Pratt, T.; Garry, E.M.; Ribchester, R.R.; Cottrell, D.F.; Fleetwood-Walker, S.M.; Brophy, P.J. Restricted growth of Schwann cells lacking Cajal bands slows conduction in myelinated nerves. Nature 2004, 431, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M.; Connell, F.; Spivack, W. Phospholipid metabolism in mouse sciatic nerve in vivo. Journal of Neurochemistry 1987, 48, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sima, A.A.; Dunlap, J.A.; Davidson, E.P.; Wiese, T.J.; Lightle, R.L.; Greene, D.A.; Yorek, M.A. Supplemental myo-inositol prevents L-fucose-induced diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes 1997, 46, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumara-Siri, M.H.; Gould, R.M. Enzymes of phospholipid synthesis: axonal vs. Schwann cell distribution. Brain Research 1980, 186, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrabee, M.G.; Brinley, F.J. Incorporation of labelled phosphate into phospholipids in squid giant axons. Journal of Neurochemistry 1968, 15, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.M.; Pant, H.; Gainer, H.; Tytell, M. Phospholipid synthesis in the squid giant axon: incorporation of lipid precursors. Journal of Neurochemistry 1983, 40, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.M.; Spivack, W.; Robertson, D.; Poznansky, M.J. Phospholipid synthesis in the squid giant axon: enzymes of phosphatidylinositol metabolism. Journal of Neurochemistry 1983, 40, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everly, J.L.; Brady, R.O.; Quarles, R.H. Evidence that the major protein in rat sciatic nerve myelin is a glycoprotein. Journal of Neurochemistry 1973, 21, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M. Incorporation of glycoproteins into peripheral nerve myelin. Journal of Cell Biology 1977, 75, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M. Metabolic organization of the myelinating Schwann cell. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1990, 605, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toews, A.D.; Saunders, B.F.; Morell, P. Axonal transport and metabolism of glycoproteins in rat sciatic nerve. J Neurochem 1982, 39, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainger, K.; Avossa, D.; Morgan, F.; Hill, S.J.; Barry, C.; Barbarese, E.; Carson, J.H. Transport and localization of exogenous myelin basic protein mRNA microinjected into oligodendrocytes. Journal of Cell Biology 1993, 123, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, L.G.; Banker, G.A.; Steward, O. Selective dendritic transport of RNA in Hippocampal neurons in culture. Nature 1987, 330, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M. The assessment of electron microscope autoradiographs. Adv Opt Electron Microsc 1969, 3, 219–272. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. Electron microscopic autoradiography: its application to protein biosynthesis. Techniques in protein biosynthesis 1973, 3, 126–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins, F.A. A time-sequence autoradiographic study of the in vivo incorporation of [1,2- 3 H-cholesterol into peripheral nerve myelin. Journal of Cell Biology 1973, 58, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, J.F.; Brown, J.C.; Fowler, K.A.; Bouldin, T.W. Axonal regeneration, but not myelination, is partially dependent on local cholesterol reutilization in regenerating nerve. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2000, 59, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrum, J.F. Cholesterol from degenerating nerve myelin becomes associated with lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein E. Journal of Neurochemistry 1991, 56, 2082–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrum, J.F.; Pentchev, P.G. Cholesterol reutilization during myelination of regenerating PNS axons is impaired in Niemann-Pick disease type C mice. J Neurosci Res 1997, 49, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, J.F. Cholesterol synthesis is down-regulated during regeneration of peripheral nerve. J Neurochem 1990, 54, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Goodrum, J.F.; Hayes, C.; Hostettler, J.D.; Toews, A.D.; Morell, P. Control of cholesterol biosynthesis in Schwann cells. Journal of Neurochemistry 1998, 71, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrast, R.; Saher, G.; Nave, K.A.; Verheijen, M.H. Lipid metabolism in myelinating glial cells: lessons from human inherited disorders and mouse models. Journal of Lipid Research 2011, 52, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolo, V.; D'Ascenzo, S.; Sorice, M.; Pavan, A.; Sciannamblo, M.; Prinetti, A.; Chigorno, V.; Tettamanti, G.; Sonnino, S. New approaches to the study of sphingolipid enriched membrane domains: the use of electron microscopic autoradiography to reveal metabolically tritium labeled sphingolipids in cell cultures. Glycoconj J 2000, 17, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleasure, D.; Parris, J.; Stern, J.; Grinspan, J.; Kim, S.U. Incorporation of tritiated galactose into galactocerebroside by cultured rat oligodendrocytes: effects of cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate analogues. J Neurochem 1986, 46, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whur, P.; Herscovics, A.; Leblond, C.P. Radioautographic visualization of the incorporation of galactose-3H and mannose-3H by rat thyroids in vitro in relation to the stages of thyroglobulin synthesis. J Cell Biol 1969, 43, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.W. The role of the Golgi complex in sulfate metabolism. Journal of Cell Biology 1973, 57, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennekoon, G.I.; Cohen, S.R.; Price, D.L.; McKhann, G.M. Myelinogenesis in optic nerve. A morphological, autoradiographic, and biochemical analysis. J Cell Biol 1977, 72, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oulton, M.R.; Mezei, C. Characterization of myelin of chick sciatic nerve during development. J Lipid Res 1976, 17, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.D. The ultrastructure of adult vertebrate peripheral myelinated nerve in relation to myelinogenesis. Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology 1955, 1, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadon, N.L.; Crotzer, D.R.; Stewart, J.R. Embryonic development of central nervous system myelination in a reptilian species, Eumeces fasciatus. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1995, 362, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, F.; Mannioui, A.; Chesneau, A.; Sekizar, S.; Maillard, E.; Ballagny, C.; Houel-Renault, L.; Dupasquier, D.; Bronchain, O.; Holtzmann, I.; et al. Live imaging of targeted cell ablation in Xenopus: a new model to study demyelination and repair. J Neurosci 2012, 32, 12885–12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Cerullo, J.; Dawli, T.; Priest, C.; Haddadin, Z.; Kim, A.; Inouye, H.; Suffoletto, B.P.; Avila, R.L.; Lees, J.P.; et al. Peripheral myelin of Xenopus laevis: Role of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions in membrane compaction. J Struct.Biol. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhrik, B.; Stampfli, R. Ultrastructural observations on nodes of Ranvier from isolated single frog peripheral nerve fibres. Brain Res. 1981, 215, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeserich, G.; Waehneldt, T.V. Bony fish myelin: evidence for common major structural glycoproteins in central and peripheral myelin of trout. Journal of Neurochemistry 1986, 46, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möbius, W.; Hümmert, S.; Ruhwedel, T.; Kuzirian, A.; Gould, R. New Species Can Broaden Myelin Research: Suitability of Little Skate, Leucoraja erinacea. Life 2021, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, N.; Homsi, S.; Morrison, H.G.; Gould, R.M. mRNAs located in Squalus acanthias (spiny dogfish) oligodendrocyte processes. Biological Bulletin 2002, 203, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saher, G.; Quintes, S.; Mobius, W.; Wehr, M.C.; Kramer-Albers, E.M.; Brugger, B.; Nave, K.A. Cholesterol regulates the endoplasmic reticulum exit of the major membrane protein P0 required for peripheral myelin compaction. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 6094–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaidero, N.; Mobius, W.; Czopka, T.; Hekking, L.H.; Mathisen, C.; Verkleij, D.; Goebbels, S.; Edgar, J.; Merkler, D.; Lyons, D.A.; et al. Myelin Membrane Wrapping of CNS Axons by PI(3,4,5)P3-Dependent Polarized Growth at the Inner Tongue. Cell 2014, 156, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobius, W.; Nave, K.A.; Werner, H.B. Electron microscopy of myelin: Structure preservation by high-pressure freezing. Brain Res 2016, 1641, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaidero, N.; Simons, M. Myelination at a glance. J Cell Sci 2014, 127, 2999–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhti, M.; Aggarwal, S.; Simons, M. Myelin architecture: zippering membranes tightly together. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014, 71, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, S.; Yurlova, L.; Snaidero, N.; Reetz, C.; Frey, S.; Zimmermann, J.; Pahler, G.; Janshoff, A.; Friedrichs, J.; Muller, D.J.; et al. A size barrier limits protein diffusion at the cell surface to generate lipid-rich myelin-membrane sheets. Dev Cell 2011, 21, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuchero, J.B.; Fu, M.-m.; Sloan, Steven A.; Ibrahim, A.; Olson, A.; Zaremba, A.; Dugas, Jason C.; Wienbar, S.; Caprariello, Andrew V.; Kantor, C., et al. CNS Myelin Wrapping Is Driven by Actin Disassembly. Developmental Cell 2015, 34, 152–167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawaz, S.; Sánchez, P.; Schmitt, S.; Snaidero, N.; Mitkovski, M.; Velte, C.; Brückner, Bastian R.; Alexopoulos, I.; Czopka, T.; Jung, Sang Y., et al. Actin Filament Turnover Drives Leading Edge Growth during Myelin Sheath Formation in the Central Nervous System. Developmental Cell 2015, 34, 139–151. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erwig, M.S.; Patzig, J.; Steyer, A.M.; Dibaj, P.; Heilmann, M.; Heilmann, I.; Jung, R.B.; Kusch, K.; Mobius, W.; Jahn, O.; et al. Anillin facilitates septin assembly to prevent pathological outfoldings of central nervous system myelin. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzig, J.; Erwig, M.S.; Tenzer, S.; Kusch, K.; Dibaj, P.; Möbius, W.; Goebbels, S.; Schaeren-Wiemers, N.; Nave, K.-A.; Werner, H.B. Septin/anillin filaments scaffold central nervous system myelin to accelerate nerve conduction. eLife 2016, 5, e17119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, P.; Einheber, S.; Galinska, J.; Thaker, P.; Lam, I.; Rubin, M.B.; Scherer, S.S.; Murakami, Y.; Gutmann, D.H.; Salzer, J.L. Nectin-like proteins mediate axon Schwann cell interactions along the internode and are essential for myelination. J Cell Biol. 2007, 178, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, I.; Adamsky, K.; Eshed, Y.; Milo, R.; Sabanay, H.; Sarig-Nadir, O.; Horresh, I.; Scherer, S.S.; Rasband, M.N.; Peles, E. A central role for Necl4 (SynCAM4) in Schwann cell-axon interaction and myelination. Nat Neurosci 2007, 10, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellissier, F.; Gerber, A.; Bauer, C.; Ballivet, M.; Ossipow, V. The adhesion molecule Necl-3/SynCAM-2 localizes to myelinated axons, binds to oligodendrocytes and promotes cell adhesion. BMC Neurosci 2007, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, M.E.; Schnell, L. Region-specific appearance of myelin constituents in the developing rat spinal cord. Journal of Neurocytology 1989, 18, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, N. Using unnatural amino acids to selectively label proteins for cellular imaging: a cell biologist viewpoint. Febs J 2021, 288, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinz, F.I.; Dieterich, D.C.; Schuman, E.M. Teaching old NCATs new tricks: using non-canonical amino acid tagging to study neuronal plasticity. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2013, 17, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, K.; Chin, J.W. Cellular incorporation of unnatural amino acids and bioorthogonal labeling of proteins. Chemical reviews 2014, 114, 4764–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.J.; Kang, D.; Park, H.S. Site-Specific Labeling of Proteins Using Unnatural Amino Acids. Molecules and cells 2019, 42, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisle, L.; Valiyaveetil, F.; Mehl, R.A.; Ahern, C.A. Incorporation of Non-Canonical Amino Acids. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015, 869, 119–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadina, N.; Tyson, J.; Zheng, S.; Lesiak, L.; Schepartz, A. Imaging organelle membranes in live cells at the nanoscale with lipid-based fluorescent probes. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2021, 65, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemen, S.; van Zandvoort, M.; Parekh, S.H.; Hesselink, M.K.C. Microscopy tools for the investigation of intracellular lipid storage and dynamics. Mol Metab 2016, 5, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; White, B.M.; Brea, R.J.; Baskin, J.M.; Devaraj, N.K. Lipids: chemical tools for their synthesis, modification, and analysis. Chem Soc Rev 2020, 49, 4602–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymchenko, A.S. Fluorescent Probes for Lipid Membranes: From the Cell Surface to Organelles. Acc Chem Res 2023, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, H.C.; Wilson, J.P.; Charron, G. Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for analyzing protein lipidation and lipid trafficking. Acc Chem Res 2011, 44, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knittel, C.H.; Devaraj, N.K. Bioconjugation Strategies for Revealing the Roles of Lipids in Living Cells. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55, 3099–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuerschner, L.; Leyendecker, P.; Klizaite, K.; Fiedler, M.; Saam, J.; Thiele, C. Development of oxaalkyne and alkyne fatty acids as novel tracers to study fatty acid beta-oxidation pathways and intermediates. J Lipid Res 2022, 63, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punt, J.M.; van der Vliet, D.; van der Stelt, M. Chemical Probes to Control and Visualize Lipid Metabolism in the Brain. Acc Chem Res 2022, 55, 3205–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanbhag, K.; Sharma, K.; Kamat, S.S. Photoreactive bioorthogonal lipid probes and their applications in mammalian biology. RSC Chem Biol 2023, 4, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Hamachi, I. Chemical biology tools for imaging-based analysis of organelle membranes and lipids. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2022, 70, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Dadina, N.; Mozumdar, D.; Lesiak, L.; Martinez, K.N.; Miller, E.W.; Schepartz, A. Long-term super-resolution inner mitochondrial membrane imaging with a lipid probe. Nat Chem Biol, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J.T.; Tirrell, D.A. Noncanonical amino acids in the interrogation of cellular protein synthesis. Acc Chem Res 2011, 44, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, D.C.; Hodas, J.J.; Gouzer, G.; Shadrin, I.Y.; Ngo, J.T.; Triller, A.; Tirrell, D.A.; Schuman, E.M. In situ visualization and dynamics of newly synthesized proteins in rat hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci 2010, 13, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancajas, C.F.; Ricks, T.J.; Best, M.D. Metabolic labeling of glycerophospholipids via clickable analogs derivatized at the lipid headgroup. Chem Phys Lipids 2020, 232, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jao, C.Y.; Roth, M.; Welti, R.; Salic, A. Metabolic labeling and direct imaging of choline phospholipids in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 15332–15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricks, T.J.; Cassilly, C.D.; Carr, A.J.; Alves, D.S.; Alam, S.; Tscherch, K.; Yokley, T.W.; Workman, C.E.; Morrell-Falvey, J.L.; Barrera, F.N.; et al. Labeling of Phosphatidylinositol Lipid Products in Cells through Metabolic Engineering by Using a Clickable myo-Inositol Probe. Chembiochem 2019, 20, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, R.E.; Lemmel, S.A.; Yu, X.; Zhou, Q.A. Bioorthogonal Chemistry and Its Applications. Bioconjug Chem 2021, 32, 2457–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.L.; Hanson, S.R.; Kishikawa, K.; Wang, S.K.; Sawa, M.; Wong, C.H. Alkynyl sugar analogs for the labeling and visualization of glycoconjugates in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 2614–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.Z.; Amikura, K.; Soll, D. Using Genetic Code Expansion for Protein Biochemical Studies. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 598577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignacio, B.J.; Dijkstra, J.; Mora, N.; Slot, E.F.J.; van Weijsten, M.J.; Storkebaum, E.; Vermeulen, M.; Bonger, K.M. THRONCAT: metabolic labeling of newly synthesized proteins using a bioorthogonal threonine analog. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlisle, A.K.; Gotz, J.; Bodea, L.G. Three methods for examining the de novo proteome of microglia using BONCAT bioorthogonal labeling and FUNCAT click chemistry. STAR Protoc 2023, 4, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharod, S.C.; Monday, H.R.; Yoon, Y.J.; Castillo, P.E. Protocol to study presynaptic protein synthesis in ex vivo mouse hippocampal slices using HaloTag technology. STAR Protoc 2023, 4, 101986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J.T.; Adams, S.R.; Deerinck, T.J.; Boassa, D.; Rodriguez-Rivera, F.; Palida, S.F.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Ellisman, M.H.; Tsien, R.Y. Click-EM for imaging metabolically tagged nonprotein biomolecules. Nat Chem Biol 2016, 12, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, I.; Tanner, H.; Masia, F.; Payne, L.; Arkill, K.P.; Mantell, J.; Langbein, W.; Borri, P.; Verkade, P. Correlative light-electron microscopy using small gold nanoparticles as single probes. Light Sci Appl 2023, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunge, R.P.; Bunge, M.B.; Bates, M. Movements of the Schwann cell nucleus implicate progression of the inner (axon-related) Schwann cell process during myelination. Journal of Cell Biology 1989, 109, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sango, K.; Kawakami, E.; Yanagisawa, H.; Takaku, S.; Tsukamoto, M.; Utsunomiya, K.; Watabe, K. Myelination in coculture of established neuronal and Schwann cell lines. Histochemistry and cell biology 2012, 137, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutschler, C.; Fazal, S.V.; Schumacher, N.; Loreto, A.; Coleman, M.P.; Arthur-Farraj, P. Schwann cells are axo-protective after injury irrespective of myelination status in mouse Schwann cell-neuron cocultures. J Cell Sci 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, D.G.; Beckett, A.J.; Prior, I.A.; Meijer, D. SuperCLEM: an accessible correlative light and electron microscopy approach for investigation of neurons and glia in vitro. Biology open 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podratz, J.L.; Rodriguez, E.; Windebank, A.J. Role of the extracellular matrix in myelination of peripheral nerve. Glia 2001, 35, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristola, M.; Sukki, L.; Azevedo, M.M.; Seixas, A.I.; Relvas, J.B.; Narkilahti, S.; Kallio, P. A compartmentalized neuron-oligodendrocyte co-culture device for myelin research: design, fabrication and functionality testing. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2019, 29, 065009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarjour, A.A.; Zhang, H.; Bauer, N.; Ffrench-Constant, C.; Williams, A. In vitro modeling of central nervous system myelination and remyelination. Glia 2012, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Kimberly, S.L.; Cai, Z.; Rhodes, P.G.; Lin, R.C. Neuron-oligodendrocyte myelination co-culture derived from embryonic rat spinal cord and cerebral cortex. Brain Behav 2012, 2, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Colognato, H.; ffrench-Constant, C. Contrasting effects of mitogenic growth factors on myelination in neuron-oligodendrocyte co-cultures. Glia 2007, 55, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.; Jukkola, P.; Gu, C. Myelination of rodent hippocampal neurons in culture. Nat Protoc 2012, 7, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, O.G.; Selvaraj, B.T.; Magnani, D.; Burr, K.; Connick, P.; Barton, S.K.; Vasistha, N.A.; Hampton, D.W.; Story, D.; Smigiel, R.; et al. iPSC-derived myelinoids to study myelin biology of humans. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Chao, J.; Zhang, M.; Pacquing, E.; Hu, W.; Shi, Y. Developing a human iPSC-derived three-dimensional myelin spheroid platform for modeling myelin diseases. iScience 2023, 26, 108037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeldich, E.; Rajkumar, S. Identity and Maturity of iPSC-Derived Oligodendrocytes in 2D and Organoid Systems. Cells 2024, 13, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, R.J.; Krogager, T.P.; Maywood, E.S.; Zanchi, R.; Beranek, V.; Elliott, T.S.; Barry, N.P.; Hastings, M.H.; Chin, J.W. Genetic code expansion in the mouse brain. Nat Chem Biol 2016, 12, 776–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.R.; Cao, Y.J. Applications of genetic code expansion technology in eukaryotes. Protein Cell 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meineke, B.; Heimgartner, J.; Eirich, J.; Landreh, M.; Elsasser, S.J. Site-Specific Incorporation of Two ncAAs for Two-Color Bioorthogonal Labeling and Crosslinking of Proteins on Live Mammalian Cells. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Ling, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Chang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Shi, X.; Niu, M.; Chen, L.; Liu, T. Tracking endogenous proteins based on RNA editing-mediated genetic code expansion. Nat Chem Biol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, E.; Kele, P. Bioorthogonal Reactions in Bioimaging. Top Curr Chem (Cham) 2024, 382, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, A.; Devaux, J. A model of tight junction function in central nervous system myelinated axons. Neuron Glia Biol 2008, 4, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gow, A.; Southwood, C.M.; Li, J.S.; Pariali, M.; Riordan, G.P.; Brodie, S.E.; Danias, J.; Bronstein, J.M.; Kachar, B.; Lazzarini, R.A. CNS myelin and Sertoli cell tight junction strands are absent in Osp/Claudin-11 null mice. Cell 1999, 99, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, T.; Morita, K.; Takemoto, D.; Takeuchi, K.; Kitano, Y.; Miyakawa, T.; Nakayama, K.; Okamura, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Miyachi, Y.; et al. Tight junctions in Schwann cells of peripheral myelinated axons: a lesson from claudin-19-deficient mice. The Journal of Cell Biology 2005, 169, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fannon, A.M.; Sherman, D.L.; Ilyina-Gragerova, G.; Brophy, P.J.; Friedrich, V.L., Jr.; Colman, D.R. Novel E-cadherin-mediated adhesion in peripheral nerve: Schwann cell architecture is stabilized by autotypic adherens junctions. Journal of Cell Biology 1995, 129, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshed, Y.; Feinberg, K.; Poliak, S.; Sabanay, H.; Sarig-Nadir, O.; Spiegel, I.; Bermingham, J.R., Jr.; Peles, E. Gliomedin mediates Schwann cell-axon interaction and the molecular assembly of the nodes of Ranvier. Neuron 2005, 47, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, N.; Liu, Y.; Arsic, A.; Meng, N.; Lyu, H.; Zhang, N.; Grimm, D.; Lerche, H.; Nikic-Spiegel, I. Direct fluorescent labeling of NF186 and NaV1.6 in living primary neurons using bioorthogonal click chemistry. J Cell Sci 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).