This section reviewed the perspective of workforce agility and crisis management literature to help business organizations to respond, adapt, and recover from the COVID-19 crises.

2.1. Workforce Agility Perspective

Workforce agility is a concept emanated from the broader concept of organizational agility. “Organization agility” or “manufacturing agility” was coined in the late nineteenth century to refer to various organizational attributes that enable organizations to respond and act competitively to any changes in the business environment (Sharifi and Zhang,1999). During the years, agility gradually evolved to be the most relevant strategy for coping with the 21st century dynamic conditions (Yusuf, Sarhadi, & Gunasekaran, 1999; Gunasekaran & Yusuf, 2002), where unpredictable, sudden, unprecedented, and frequent changes are dominant and are more likely to trigger different types of crises.

Since its inception, the concept was believed to fit only manufacturing companies context, but later, it became widely spread, used, and extended to diverse business functions, such as business process agility (Seethamraju & Sundar (2013), supply chain agility (Swafford, Ghosh, & Murthy (2008), customer agility (Roberts & Grover, (2012), and workforce agility (Almahamid, 2018; Alavi, Wahab, Muhamad & Shirani (2014); and can be collectively applied to the whole organization-that is organizational agility (Almahamid, 2019; Zain, Rose, Abdullah, & Masrom, 2005; Sherehiy et al. 2007). Applying agility to different aspects of an organization has led to the existence of unprecise and ambiguous definitions of agility (Walter, 2020). For example, Gunasekaran (1999) defined agility “as the ability to survive and prospering in a competitive environment of continuous and unpredictable change by reacting quickly and effectively to changing markets, driven by customer-defined products and services.”

According to Sharifi & Zhang (1999), agility is about the ability to detect the changes in the business environment and respond to them by providing the appropriate capabilities. Earlier, Kidd (1994) defines agility as a rapid and proactive adaptation of enterprise elements to unexpected and unpredicted changes. Alavi, & Wahab (2013) described agility as a set of the organization's abilities that include the following: (1) uncovering new opportunities for competitive advantage; (2) integrating the existing knowledge, assets, and relationships to seize these opportunities; and (3) adjusting to sudden changes in business conditions. A common shared theme among all these definitions is that the environmental conditions are unpredictably changing over time so that organizations must respond and adapt promptly to these changes to survive. Although these definitions are theoretically valid and logical, they are irrelevant and inappropriate for practitioners as they do not show how to develop agility. They also do not show how long the development may take before a new change emerges that entails a new form of agility, nor do they show what types of challenges they may face during the development journey? or what are the best interventions to maintain it? Practically, organizations cannot act promptly and competitively to seize emerging business opportunities attached to crisis without agile workforces or what is called “workforce agility”. Workforce agility is a key element for achieving organizational agility, where it is intertwined with agile strategy and agile leadership (Ulrich and Yeung, 2019) to create the most appropriate response to the business environment.

As workforce agility is a complex and multifaceted concept, it restricts advanced empirical studies in this domain (Varshney & Varshney, 2020). Despite the importance of workforce agility to deal with the dynamic business environment, it is still ill-defined (Muduli, 2016), and similar concepts such as “individual agility”, “human resource agility”, and “personal agility or leadership agility” (Azuara, 2015; Braun et al. 2017; Ulrich and Yeung, 2019) have been used interchangeably. Overly, it also overlaps with “resilience” – a concept that is used in the organizational psychology domain to reflect an individual’s ability to mitigate, manage, and reduce workplace stress that is caused by dramatic changes in the business environment (Braun et al. 2017). Despite both concepts, though, distinct attributes are still needed. Presumably, agility raises the amount of stress in the workplace as it demands extra effort from employees, whereas resilience reduces it by reflecting positive attitudes towards change and considering it a real opportunity (Braun et al. 2017). Resilience is more related to a set of personality traits that is hard for an individual to change, while agility is a skill or behavioral skill that can be improved by formal and informal training and learning. Braun et al. (2017) posit that agility on the individual level is “equipping employees with the [right] skills to proactively identify and implement change when needed”. Other studies believe that the individual’s ability to act at high-speed to ensure success and survival (Bosco, 2007) is a sort of workforce agility. Workforce agility can be defined as an individual’s ability to respond, adjust, and adapt his/her behaviors in the face of severe adverse events stemming from a crisis by learning how to navigate and turn the crisis threats into a real business opportunity before competitors.

Carrying out an organization’s agility strategy demands agile workforces (Sherehiy et al. 2007); Safari, Maghsoudi, Keshavarzi, & Behrooz (2013), who can deal with unexpected and unprecedented changes caused by a crisis. Agile workforces formed the foundation of an agile organization. They can turn any potential threats of crisis into opportunities and capitalize on them by addressing customers’ emergent needs and offering high-quality products or services (Sherehiy, 2008; Sherehiy, Karwowski, & Layer, 2007). Agile workforces can maintain a balance between handling the complexity of uncertainty along exercising autonomy when dealing with adverse events (Varshney & Varshney, 2020). Taken together, these results indicate that achieving a high level of workforce agility in real-world practice is a challenging task and is a continuous process that depends on employees’ willingness to be agile. According to Ripatti (2016), attracting employees’ attention towards agility is a tough task for organizations that intend to be agile. Youndt et al. (1996) argued that developing and maintaining a ‘‘highly skilled, technologically competent and adaptable workforce that can deal with non-routine and exceptional circumstances’’ is necessary to achieve flexibility - which is one dimension of manufacturing agility strategy.

In the early ’90s and up to the new millennium, the workforce agility literature was purely theoretical (Almahamid, 2018), focused on identifying employees’ agile attributes with a few exceptions (Breu et al., 2001). Prior models (for details see Sherehiy et al. 2007; Sherehiy, 2008) identified several attributes for agile workforces, without differentiating between personality trait-based attributes and behavioral-based attributes. Yet, it is still not clear if some of these attributes are birth-traits or malleable traits that can be developed and improved by following effective intervention training programs (Braun et al. 2017; Taran, 2018; Varshney & Varshney, 2020). Moreover, if organizations can develop these traits before, during, or sometimes after a crisis, it should be noted how long and how fast it takes to develop them. However, it is all still unclear especially when facing an unprecedented crisis like COVID-19. Thus, the unique crisis of COVID-19 left/raised many questions in the literature yet to be answered.

At the beginning of the new millennium, a paradigm shift has occurred in the perspectives of scholars towards behavioral aspects of workforce agility. This may be due to the increased numbers and speed of changes in the business environment, and that the different types of crises start emerging continually. According to Griffin and Hesketh (2003), an individual has three behavioral choices when dealing with changes in a business environment, which include being proactive, reactive, or tolerant. Proactive behavior reflects an individual’s ability to initiate actions and try to change the new environment to fit his/her aims and endeavors. Reactive behavior relates to accepting crises by adjusting ones’ behavior to fit with the new environmental conditions. Finally, tolerance behavior is the passive form of reactive behavior where an individual is only bearing the burden of the new conditions and carrying on working activities when other choices are not possible at least for the time being.

The three types of behaviors highlight the importance of behavioral aspects of agility. However, the distinction between reactive and tolerance behavior in practice is borderless and minimal as each change causes a stressful situation that an individual must deal with. Besides, classifying individuals’ behaviors in that way has created a big doubt for practitioners regarding the most appropriate behavior to follow when a new change emerged as there are some aspects of change that can be managed and changed, while others cannot be managed nor changed. Building on Griffin’s and Hesketh’s assumptions, Sherehiy et al. (2007) not only reviewed the previous agility models, but also combined and categorized the workforce agility attributes under three behavioral factors which are proactive, adaptive, and resilient and which correspond to Griffin’s and Hesketh’s identified behaviors.

Subsequently, Sherehiy (2008) developed a generic measure for workforce agility consisting of three behavioral dimensions: proactive, adaptable, and resilient behavior. Sherehiy contends that each behavioral dimension is represented by several personal attributes that stimulate workforce agility. For example, attributes as anticipating problems related to change, initiating activities that lead to help to find solutions for change-related problems and improvements in work, developing solution for change-related problems all promote proactive behavior. Attributes such as interpersonal and cultural adaptability, spontaneous collaboration, learning new tasks and responsibilities strengthen adaptive behavior. Finally, a positive attitude towards change to new ideas, technology, and tolerance as well as dealing with uncertain, unexpected situations, and coping with stress can spur an individual’s resilient behavior.

Lately, these three behaviors have become a common measure for workforce agility in almost all consequence empirical studies (Alvai et al. 2014; Cai et al. 2018; Hosein and Yousefi, 2012; Liu, Li, Cai, & Huang, 2015; Sherehiy and Karwowski, 2014; Varshney & Varshney, 2020). These studies deemed attitude as an essential part of workforce agility and are not less important than behavioral ones. According to Asari, Sohrabi, & Rashdi (2014), there is a lack of studies in exploring workforce agility using an attitudinal lens. The authors used Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior to develop a theoretical model where the intention to agility is a function of several attitudinal and contextual factors which include attitude towards agility, subjective norms, and perceived environmental as well as an internal control at the workplace. As a result, the intention influences actual agile behavior. Thus, improving workforce agility demands developing both attitudinal and behavioral aspects.

In parallel, researchers began scanning and searching the surrounding context for drivers to increase workforce agility and explored issues as diverse as emotional intelligence (Hosein and Yousefi, 2012, Varshney & Varshney, 2020); (Sherehiy and Karwowski, 2014); organization structure, and organizational learning (Alvai et al. 2014); E-HRM(Al-Kasasbeh et al.2016); enterprise social media and psychological conditions (Cai et al. 2018); task conflict and relationship conflict(Liu, Li, Cai, & Huang, 2015) and found positive relationships between these contextual factors and workforce agility. The implicit assumption in these studies indicates that having more agile attributes mirrors employees’ abilities to be resilient and agile to deal with a crisis successfully by adapting easily and coping with changes distressfully and innovatively (Braun et al., 20171; Bardoel, Pettit, De Cieri, & McMillan, 2014). More importantly, most of these studies are cross-sectional and by no means claim a causational relationship between contextual antecedents and workforce agility. Although workforce agility only manifests itself in a real-world crisis, these studies have not been conducted during a real crisis, and they depend heavily on a self-report measure to assess workforce agility reflecting only employees’ attitudes towards agility but not their actual agile behavior. Certainly, there is a significant gap between an individual’s attitudes and behaviors. Prior studies not only have widely dispersed agile attributes but also have not agreed on what formed workforce agility antecedents and consequences that have left practitioners without clear guidance.

Regardless of the number of attributes that employees may already have, workforce agility is an evolving action plan that should be developed, revised, and adjusted over time to fit with emerging crises. Agile workforces who interact with each other and external stakeholders determine how to attend to the crisis and its consequences more than only having a plan or strategy designated for dealing with the impending crisis. As the number and probability of crises occurrences increased dramatically to include refugee crises, political crises, war crises, natural crises, debt crises, the Greece crisis, the Euro crisis, and other Brexit crisis, as well as the COVID-19 crisis, both organizations and individuals witness a life full of crises or what we called “the generation of crisis”. Thus, managing a crisis is a challenging task and not all companies can navigate the crisis successfully especially when it is a novel crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Crisis Management Perspective

More than ever, organizations have encountered different crises and responded with varying degrees. According to Oxford’s dictionary, a crisis is “ a time of great danger, difficulty or doubt when problems must be solved or important decisions must be made; or a time when a problem, a bad situation or an illness is at its worst point”. In general, crisis management refers to the processes that organizational leaders use to take actions, decisions, and communicate with internal and external stakeholders to reduce the negative crisis effect and speed up the recovery process. Specifically, organizational crisis, according to Clark (1995/1996) refers to “unplanned events that cause death or significant injuries to employees, customers or the public; shut down the business; disrupt operations; cause physical or environmental damage, or threaten the facility’s financial standing or public image”. This is a comprehensive definition that firmly fits in with the current health crisis. It indicates that a crisis is ingrained in governments, companies, and the lives of individuals and an inevitable event. Eventually, several contextual internal and external, technical/ economic, social, and organizational factors trigger crises within organizations (Mitroff, 1987). The COVID-19 crisis causes significant causality among citizens (employees working in different organizations), close-down business organizations, disrupts business operations, and provokes significant financial losses. Regardless of the crisis type, whether a natural disaster, a terrorist attack, an economic and financial recession, a failure in systems and machines, a human error, or a pandemic like Covid-19, all can strike dramatic, unpredictable, and severe threats on the government, business organizations, and individuals’ daily operations (Burnard, 2013; Mitroff, 1987; Roseline and Monday, 2020). Thus, the COVID-19 crisis management can be defined as a set of processes, actions, decisions that decision-makers have used to deal with the threats to reduce the numbers of causalities and infection rates, speed up recovery, and create hope for returning business operations to normality as soon as possible. Organizational crises originate from two main sources: external and internal. The COVID-19 crisis is considered as one of the external organizational crises (Roseline & Monday, 2020).

Internal organizational crises can be avoided and controlled by planning and designating a strict control system. In contrast, external organizational crises corresponding to the COVID-19 pandemic is one that is certainly difficult to prevent, predict, and control. The unprecedented COVID-19 crisis represents a unique event with different implications for different parties, but not all governments, business organizations, and individuals are ready and well-prepared to deal with it. Invariably, a crisis represents a deviation from the ordinary government, business, and individuals’ operations and activities. Events that induce-crisis are characterized by having a low level of probability, a high level of tragic consequences and ambiguity, and time pressure for taking decisions (Runyan, 2006), as well as causing a threat to organizations’ reputations and lives. On the 11th of March 2020, when the World Health Organization (W.H. O) declared and labeled the COVID-19 a pandemic, it openly and directly urged governments and business organizations around the globe to be prepared for the pandemic. That reflected the early warning signs that a crisis was on the way. In the beginning, neither governments nor business organizations caught the signal of the crisis, they thought it will be limited to some specific geographical territories like China and its neighboring countries. In a few weeks, the pandemic spread all over the world and became a public health crisis everywhere.

Dealing with this crisis is a tough task, it requires estimating the size of threats, identifying the surprises that accompanied the event, and taking decisions quickly and acting promptly to reduce the negative impact on various stakeholders’ groups (Roseline and Monday (2020). Yet, a significant part of the crisis management literature to date still tends to focus on how to prevent organizational crises and minimize their impact rather than acknowledging the business environment is dynamic and full of triggers for crises. However, the COVID-19 crisis cannot be prevented, but its negative and undesirable effects can be reduced. The COVID-19 crisis per se has not always been harmful as the crisis is inevitable and has become a part of modern business organizations’ lives. The problem is in the misinterpretation and the unjustified delay as a result of managers’ reactions and actions. This may be due to the failure of the formal organizational control structure to pick up the early warnings and weak signals of the crisis that are exchanged and transmitted among individuals and team members through ongoing streams of social interaction that are transferred through informal networks (Fischbacher-Smith & Fischbacher-Smith, 2014). Most likely these signals are missed or rejected and sometimes ignored by business managers because they have less probability to occur. When a crisis emerges, leaders must respond quickly by taking a series of quick decisions that are done all over the crisis phases to mitigate its effect. Several organizational, psychological, and situational factors determine the chosen response strategy. According to Lamin and Zaheer, (2012) the efficacy of the response strategy certainly relies on either business or public communities.

The crisis management literature is mainly used to deal with economic, financial, and natural disaster crises, but rarely with a prolonged pandemic crisis of COVID-19. COVID-19 is a crisis with a special peculiarity; in this regard, previous theories, models, guidelines, and frameworks for managing crises may not fit the current context and can be only used as a general guideline for managing the COVID-19 crisis effectively and efficiently. Practically, a crisis often progresses along with three phases, namely, pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis (Bundy et al. 2016; Mitroff, 1987; Roselin and Monday, 2020). In the pre-crisis phase, the focus is on the level of the organization’s preparedness by having a crisis’ plan with different possible scenarios, testing schedule, and live exercise carried out frequently using a simulated case. By doing so, an organization can revise the plan, learn what works, what does not work, and how to be ready for the next approaching crisis. The crisis phase is the crucial one among other phases where an organization’s leaders take decisions and actions, as well as devise effective communication strategy, where they try resorting to prevent the crisis, minimize its impact, and re-establish control. The post-crisis phase relates to lessons learned and public evaluation of an organization’s ability to handle the crisis.

The three phases indicate that organizational preparedness, business leaders’ proactive behaviors, and workforce agility should occur simultaneously for a timely response. Organizations that have a crisis management plan that is updated regularly, a crisis management team, a setup periodical testing schedule for the plan and a devised persuasive communication message will be much more capable to handle a crisis than their equal counterparts (Barton, 1993). So far, we have discussed how each line of literature deals with an uncertainty that is caused by a change (crisis) in the business environment, the next section discusses the syntheses of both perspectives.

2.3. Synthesizing of Both Perspectives

Although each line of the workforce agility and crisis management literature is independent of each other and presents an imperfect picture of how to respond to a crisis, both types of literature share several commonalities. For example, both lines of literature deal with unprecedented and unpredictable changes and agree that the business environment is so complex and full of crisis triggers. Both kinds of literature also highlight the necessity of developing a response strategy or an action plan to be ready for the next crisis to reduce its negative impact and speed up the relief process. Besides, both lines of literature highlight the importance of proactive behavior of individuals to prevent, manage, and recover from the crisis. Despite these commonalities, there are differences as well as real opportunities for synthesis. We found limited research that integrates these two lines of literature to understand how the interference and cross-cutting between the two lines can help to conquer the COVID-19 crisis.

Both crisis management and organizational agility literature deal with a crisis as an unexpected and unprecedented event that occurred on an organizational level or what is called “event perspective” response (Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd, & Zhao, 2017), even though the response to a crisis is a collective action that must include all levels. Both lines of literature ignored the role of agile workforces during an action. Exceptionally but theoretically, the study of Roseline and Monday (2020) is the only work that links organizational agility with crisis management. The researchers suggested that organizational agility capabilities such as flexibility and speed can be used as coping means to deal with, manage, and recover from a crisis such as COVID-19.

Other researchers tried to combine resilience literature -one dimension of organizational agility with crisis management literature together to understand how organizations respond and cope with unexpected and sudden changes in the business environment (Williams et al. 2017). Therefore, the current study tries to extend this line of thoughts by exploring how workforce agility can enhance organizations' capabilities to combat COVID-19 or any looming crisis. What Roseline and Monday proposed is that organizational agility (Speed and flexibility) is a fundamental strategy to deal with a crisis such as COVID-19 by following one of three strategies: Proactive strategy that is related to putting down all resources, procedures, knowledge, skills, and plans a long time. Responsive strategy relates to an organization’s ability to respond and react positively to the crisis. The logic behind this strategy is to watch when the crisis signs start to appear, then react and respond quickly by taking timely decision making. Finally, the reactive strategy is related more to absorbing the crisis shock and allowing it to pass, and then considering the best things to do (Roseline & Monday, 2020).

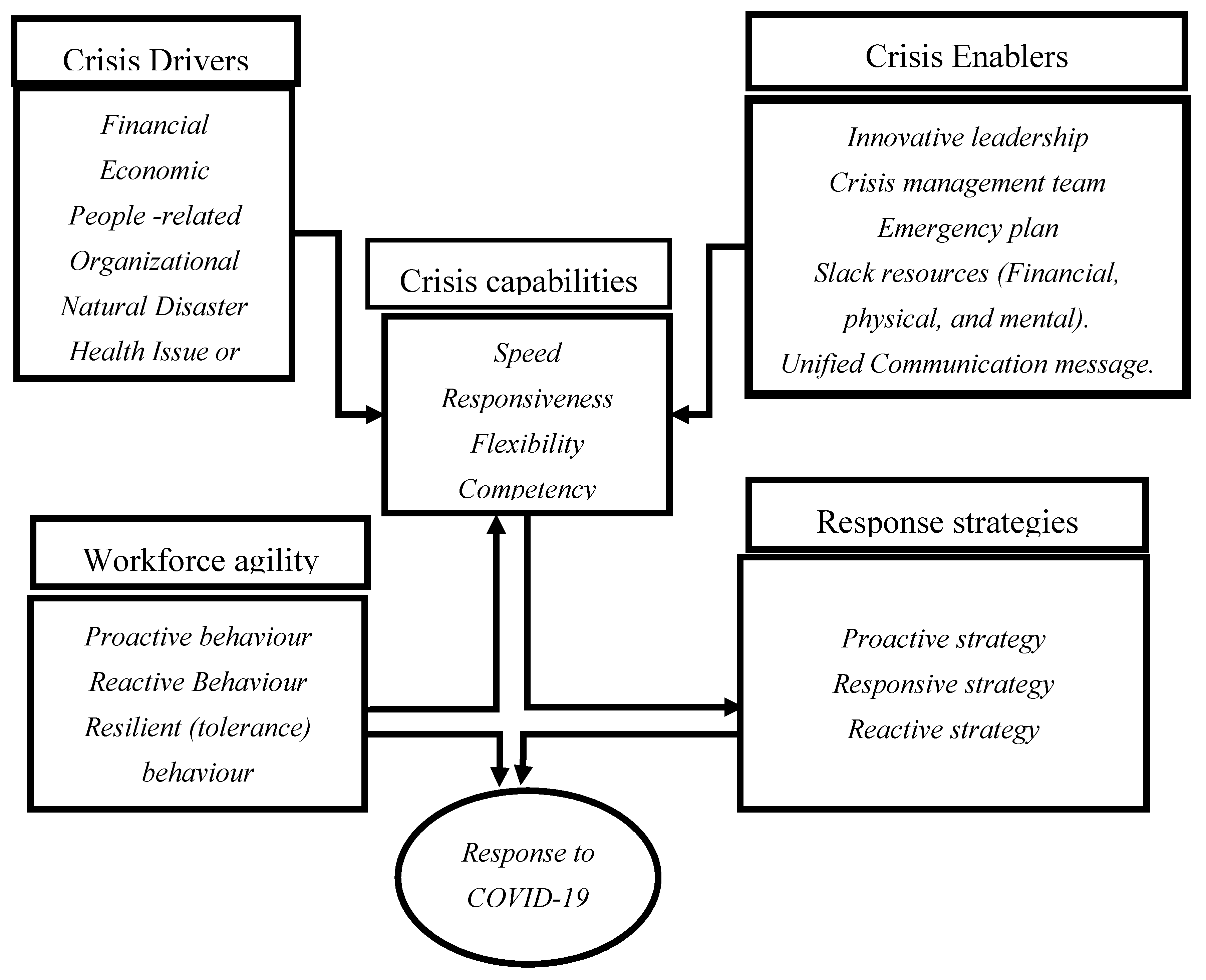

For business managers, it was not clear under which circumstances each strategy is applicable and can be implemented effectively. We believe that the three types of strategies can be used sequentially or concurrently according to the development of the crisis phases. This is due to dealing with a crisis as a continued process (Williams et al. 2017), which normally goes through pre-adversity, during, and post-crisis. We developed a theoretical framework to show how crisis drivers, enablers, capabilities, response strategy, and workforce agility are intertwined for an organization to respond to COVID-19 as shown in

Figure 1. Agility drivers are the triggers of any crisis and could be financial, economic, organizational, people-related, and pandemic-related like COVID-19 that require developing a set of crisis capabilities (speed, responsiveness, flexibility, and competency). To develop these capabilities, companies must have the right set of enablers including innovative leadership, a crisis management team, an emergency plan, slack resources, a unified communication message, and an integrated health system. Developing these capabilities entails employees who are capable to alternate their behaviors from being proactive, reactive, and resilient according to the severity of the COVID-19 crisis. The capabilities also enable an organization to follow different paths of strategy selection according to the size and severity of the crisis threats. Having needed behavior integrated with the best-fit response strategy enables an organization to respond effectively and efficiently to the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, with the increasing number of crises, applying one response strategy is questionable and can be challenged. The proactive strategy, for example, may work well with internal organizational crises but not with the COVID-19 pandemic as the existing emergency plan needs adaptation to fit the specificity of the new crisis. Similarly, the reactive strategy is not a business-wise strategy as businesses are always looking to reduce losses and maximize profits especially when the consequences are a matter of life or death. The proactive strategy can increase organizational preparedness for a crisis but does not prevent it as it was proposed. In this case, integrating a proactive strategy with a response strategy may be the most appropriate strategy that best fits with the COVID-19 crisis. Additionally, what Roseline & Monday (2020) proposed is not valid and lacks empirical root because organizational agility is an output of several organizational practices and is significantly underpinned by agile workforces. Regardless of response strategy, workforces who choose, act, and decide which is the right response strategy that best fits the situation of crisis, is that proactive, responsive, or reactive. The agile workforce is one of the enablers of organizational agility. Agile workforces help agile organizations to easily pick up the early warnings and weak signals that appear beforehand in a business environment and deal with crisis efficiently and effectively (Fischbacher-Smith & Fischbacher-Smith, 2014). Agile workforces determine how and why an organization must handle the crisis in a certain way but not the other way around. Often, agile individuals are capable and well-prepared, trained to carry on a response strategy by being physically and mentally prepared, and are ready to deal with any impending crisis. Agile workforces alternate their behavior with the development of the crisis.

At the beginning of a pandemic crisis, agile workforces use reactive behaviors by adjusting their behaviors to fit in with the new environmental conditions, while learning and developing new skills, knowledge, and competencies. By the time they understand the crisis well by reducing uncertainty and minimizing risk levels, they utilize proactive behavior by changing the crisis challenges into real opportunities. In the worst-case scenario, agile workforces show a high level of resilience even if the situation does not allow them to behave proactively or reactively by carrying on working and bearing the high pressure of the crisis until a window of hope appears on the horizon to transform the crisis into opportunity. In contrast, none-agile individuals cannot adjust their behaviors according to the evolution of the crisis. Dealing with any crisis is an individual’s decision that enriches the organizational ability to be flexible and promptly respond to unexpected and surprising events.