Submitted:

17 May 2024

Posted:

19 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Weber’s Electrodynamics

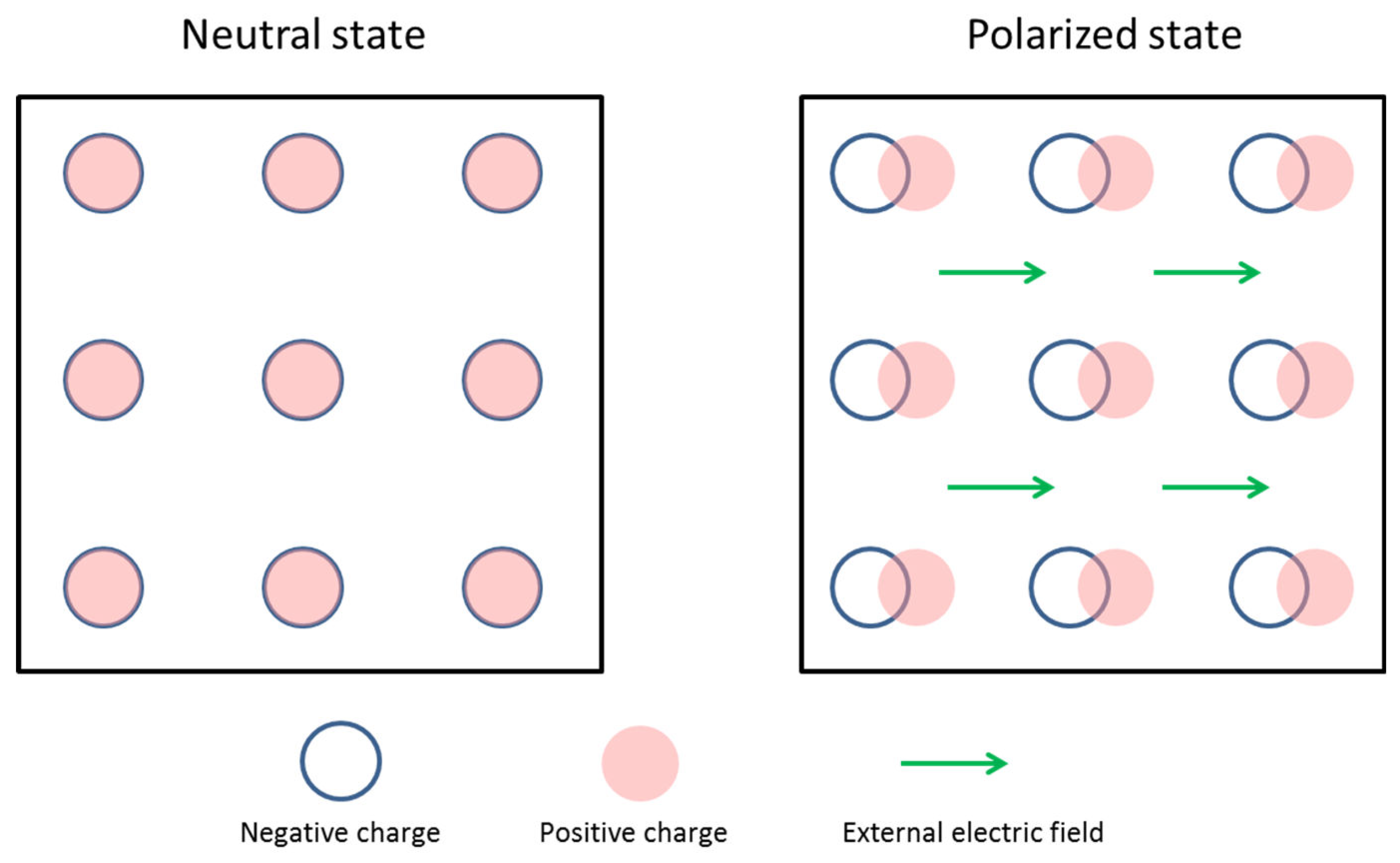

Vacuum Polarization

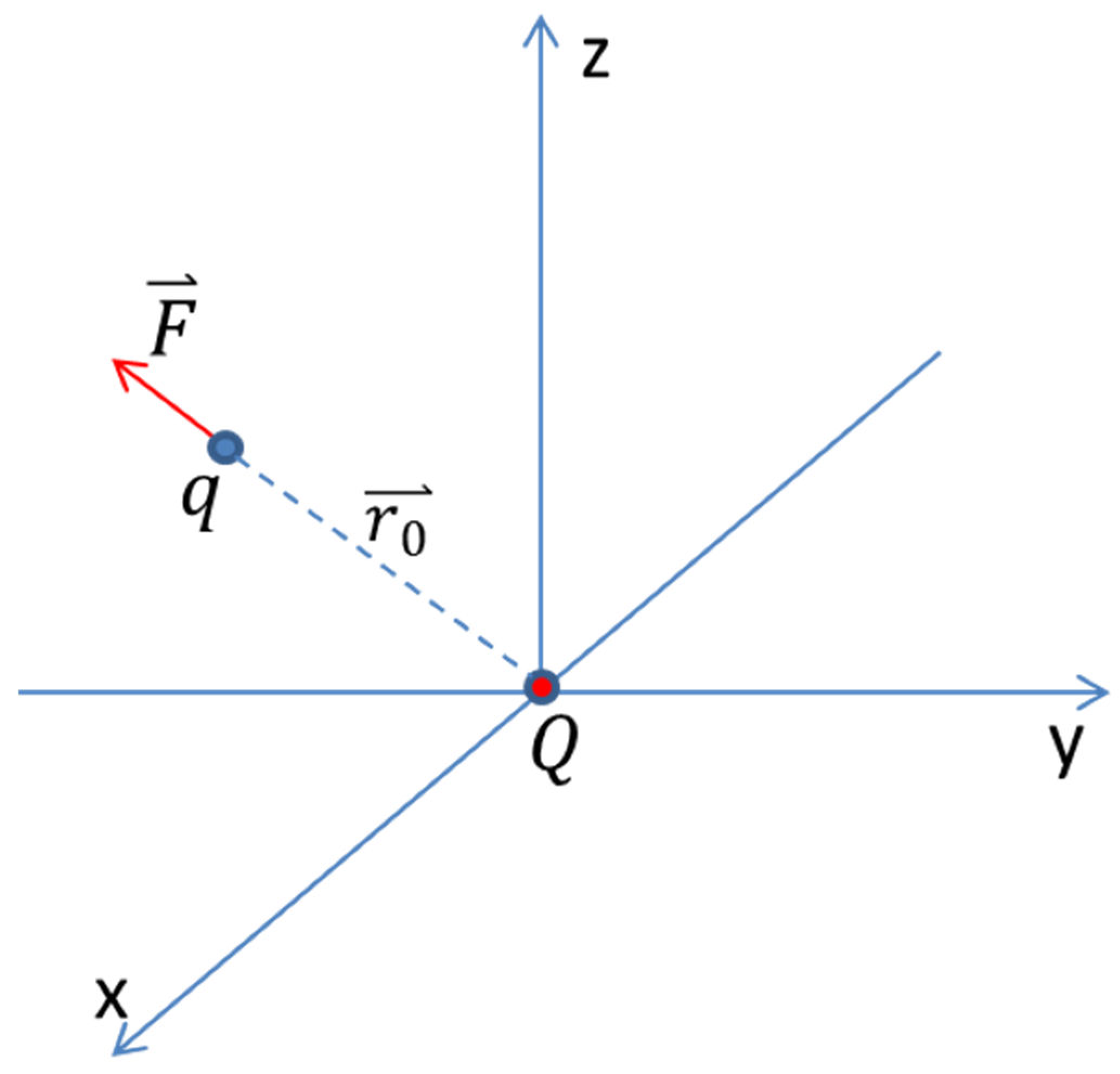

Charge Interaction in an Empty Space

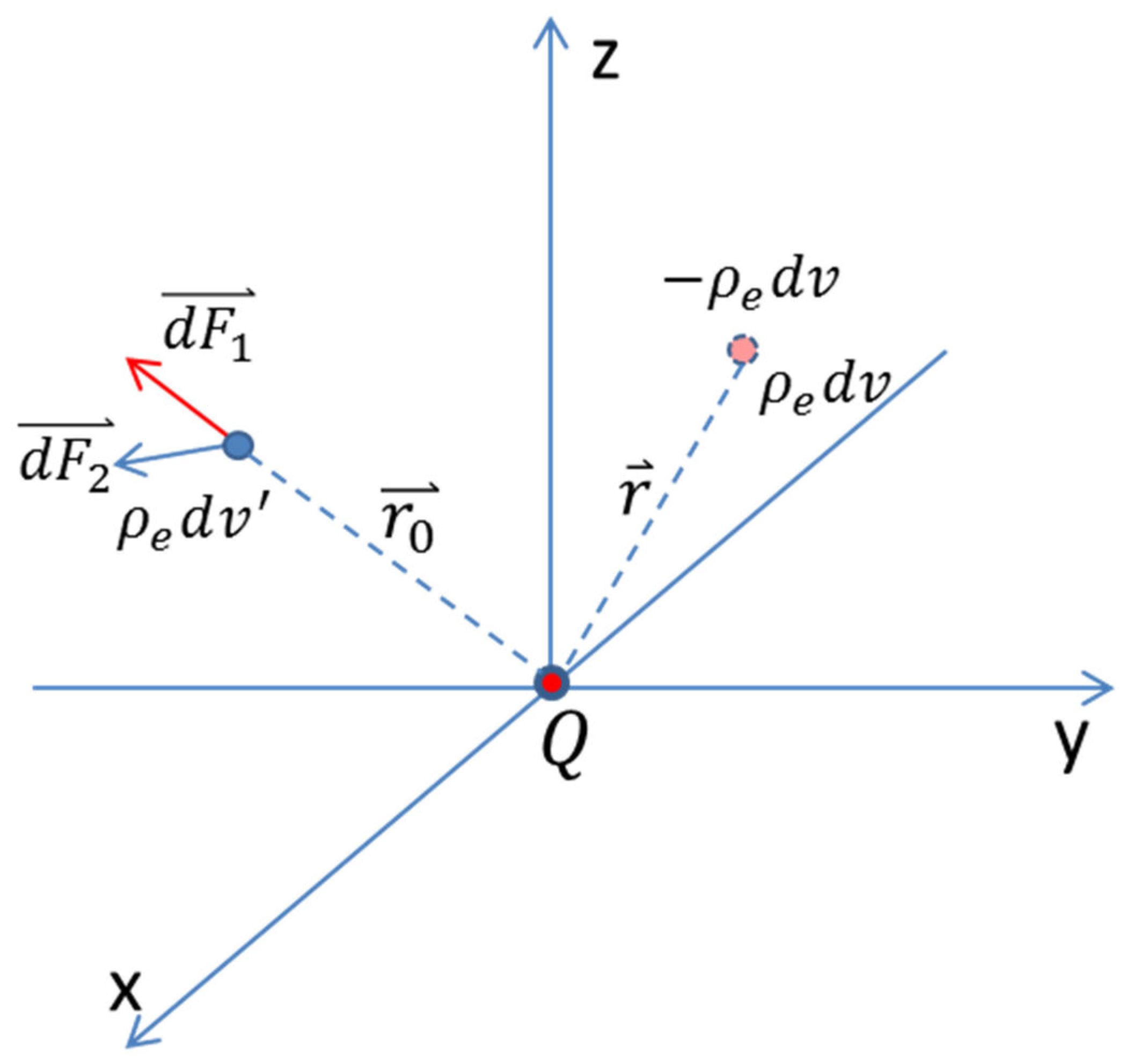

Charge Interaction in Polarizable Vacuum

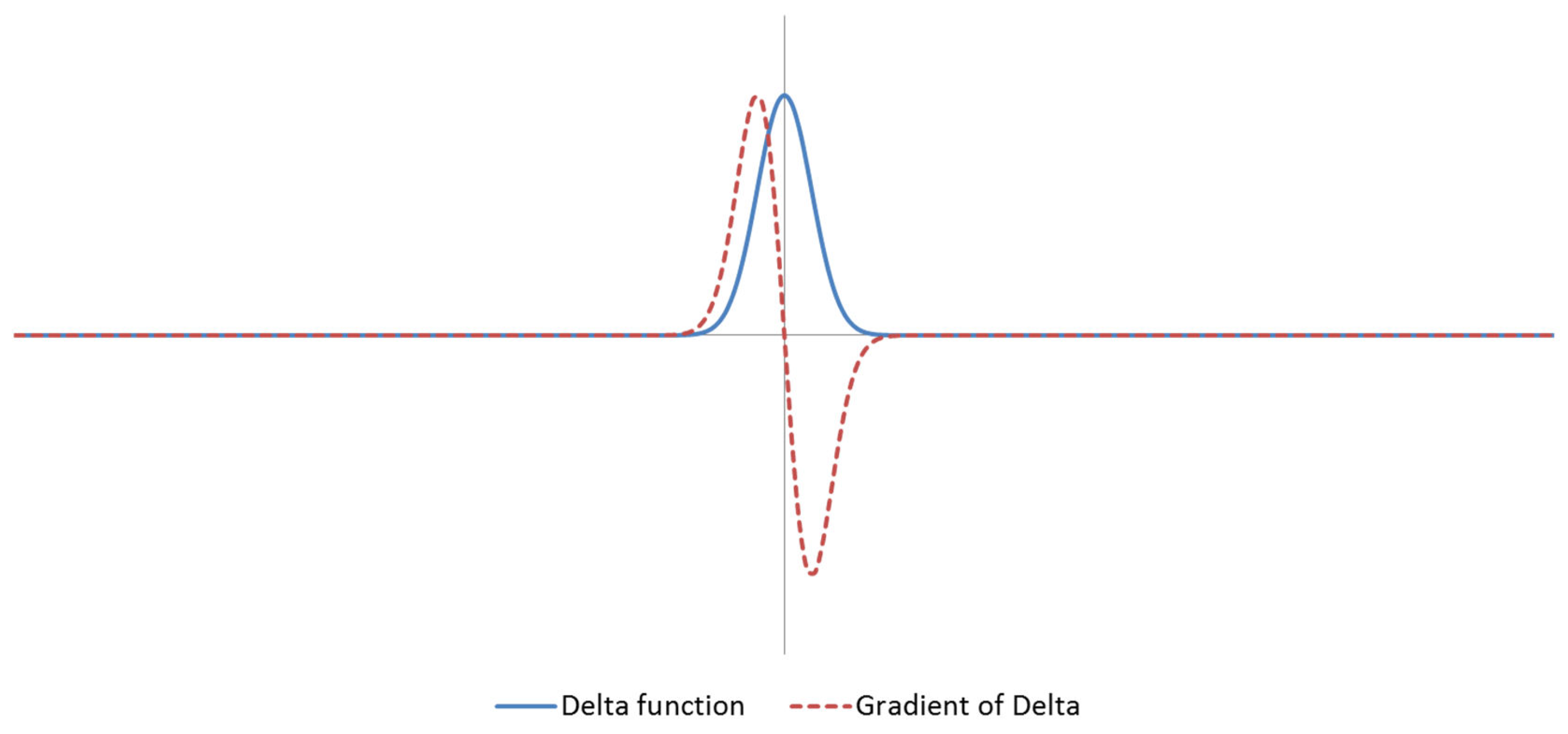

Uniqueness of the Solution

Discussion

- Each charge possesses inertia, resulting in a response to applied force contingent on inertial mass.

- In dealing with a many body system, it behaves akin to an intermediate medium or carrier of information.

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Graneau, P., & Graneau, N. (1993) Newton versus Einstein: How matter interacts with matter. Sheffield: Carlton Press.

- Wolfgang Pietsch, On conceptual issues in classical electrodynamics: Prospects and problems of an action-at-a-distance interpretation. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2010, 41, 67–77. [CrossRef]

- Hesse, Mary B. (December 1955). "Action at a Distance in Classical Physics". Isis 1955, 46, 337–353. [CrossRef]

- Jeans, James (1947) The Growth of Physical Science. Cambridge University Press.

- James Clerk Maxwell (1st ed. 1873) A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, Vol II pages 426–438.

- Albert Einstein (1905) "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper", Annalen der Physik 17: 891; English translation On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies by George Barker Jeffery and Wilfrid Perrett (1923); Another English translation On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies by Megh Nad Saha (1920).

- Rothman, Tony. The Secret History of Gravitational Waves. American Scientist 2018, 106, 96–10. [CrossRef]

- Wesley, J. Weber electrodynamics extended to include radiation. Specul. Sci. Technol. 1987, 10, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang Engelhardt, 2015, Relativity of time and instantaneous interaction of charged particles. American Journal of Modern Physics 2015, 4, 15–18.

- Moerkamp, Mischa. (2018). Field-free electrodynamics. DOI: arXiv:1806.10082v8.

- P. A. M. Dirac. Classical theory of radiating electrons. Proceedings of the Royal Society London. Series A 1938, 167, 148–169.

- J. A. Wheeler, R. P. Feynman. Interaction with the Absorber as the Mechanism of Radiation. Reviews of Modern Physics 1945, 17, 157–181. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. A.; Feynman, R. P. (July 1949). "Classical Electrodynamics in Terms of Direct Interparticle Action". Reviews of Modern Physics 1949, 21, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kühn (2022) Inhomogeneous wave equation, Liénard-Wiechert potentials, and Hertzian dipoles in Weber electrodynamics. Electromagnetics 2022, 42, 571–593. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Villecco, 1993, Instantaneous action-at-a-distance representation of field theories. Phys. Rev. E 1993, 48, 4008–4026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, Andre & Torres, Hector. (2012). Comparison between Weber’s electrodynamics and classical electrodynamics. Pramana Journal of Physics 2000, 55, 393–404. [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtel, C.; Maher, S. Foundations of Electromagnetism: A Review of Wilhelm Weber’s Electrodynamic Force Law. Foundations 2022, 2, 949–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Extending Weber’s Electrodynamics to High Velocity Particles. Int. J. Magn. Electromagn. 2022, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, J.M. On the Modernisation of Weber’s Electrodynamics. Magnetism 2023, 3, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Maher, S. (2023). Deriving an Electric Wave Equation from Weber’s Electrodynamics. Foundations 2023, 3, 323–334.

- A. K. T. Assis and M. Tajmar, Rotation of a superconductor due to electromagnetic induction using Weber's electrodynamics, Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie, Vol. 44, pp. 111-123 (2019).

- Weinberg, S. (2002). Foundations. The Quantum Theory of Fields. Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55001-7.

- Karbstein, F. Probing Vacuum Polarization Effects with High-Intensity Lasers. Particles 2020, 3, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukai, J. A Promenade Along Electrodynamics; Vales Lake Publishing: Pueblo West, CO, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner, Kenneth F. (1972), Nineteenth-century aether theories, Oxford: Pergamon Press, ISBN 978-0-08-015674-3.

- Michelson, Albert A.; Morley, Edward W. (1887). "On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether". American Journal of Science. 34 (203): 333–345.

- Einstein, A. (1915) The Field Equations of Gravitation. In: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1914-1917 (English Translation Supplement) in the Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol. 6, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 117.

- Assis, A.K.T. Weber’s Electrodynamics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovich, Eugene. (2023). Propagation speed of Coulomb force. What do experiments say? Researchgate. 2023-05 Preprint.

- Yin, Juan; Cao, Yuan; Yong, Hai-Lin; Ren, Ji-Gang; Liang, Hao; Liao, Sheng-Kai; Zhou, Fei; Liu, Chang; Wu, Yu-Ping; Pan, Ge-Sheng; Li, Li; Liu, Nai-Le; Zhang, Qiang; Peng, Cheng-Zhi; Pan, Jian-Wei (2013). "Bounding the speed of 'spooky action at a distance". Physical Review Letters 2013, 110, 260407.

- Francis, Matthew (30 October 2012). "Quantum entanglement shows that reality can't be local". Ars Technica.

- Bondi, Hermann; Samuel, Joseph (July 4, 1996). "The Lense–Thirring Effect and Mach's Principle". Physics Letters A 1996, 228, 121–126.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).