1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) began in 2019. Numerous SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been developed, and various adverse reactions to vaccination have been reported. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT), in which anti-platelet factor 4 (PF4)-adenovirus complexes are involved, reportedly occurs within 3 months of adenovirus vector vaccine administration [

1]. Although VITT after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2 vaccine) administration is rare, it is important to predict the possibility of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) development after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with a thrombophilic predisposition.

Elevated plasma β-thromboglobulin (βTG) and PF4 levels indicate platelet activation and are useful for diagnosing thrombosis, examining thrombus formation risk, and determining the efficacy of thrombosis treatment. However, PF4 and βTG levels are not widely measured in routine clinical practice because they are often released in response to stimuli such as blood sampling; because of this, blood used for measuring these levels must be sampled carefully.

Thrombus formation and intravascular coagulation from platelet activation can cause myocardial infarction, nephritis, and the development of pathological conditions. In patients with diabetes mellitus, PF4 and βTG levels are elevated due to concomitant microangiopathy and can be used to detect DVT. The efficacy of PF4 as a cardiovascular risk biomarker in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease has also been reported [

2], and its importance as a marker of DVT is being evaluated.

In this study, we report a case of pediatric antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) in which the level of PF4 was persistently elevated after administration of a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine (BNT162b2); DVT developed 6 months after the second vaccination.

2. Case Presentation

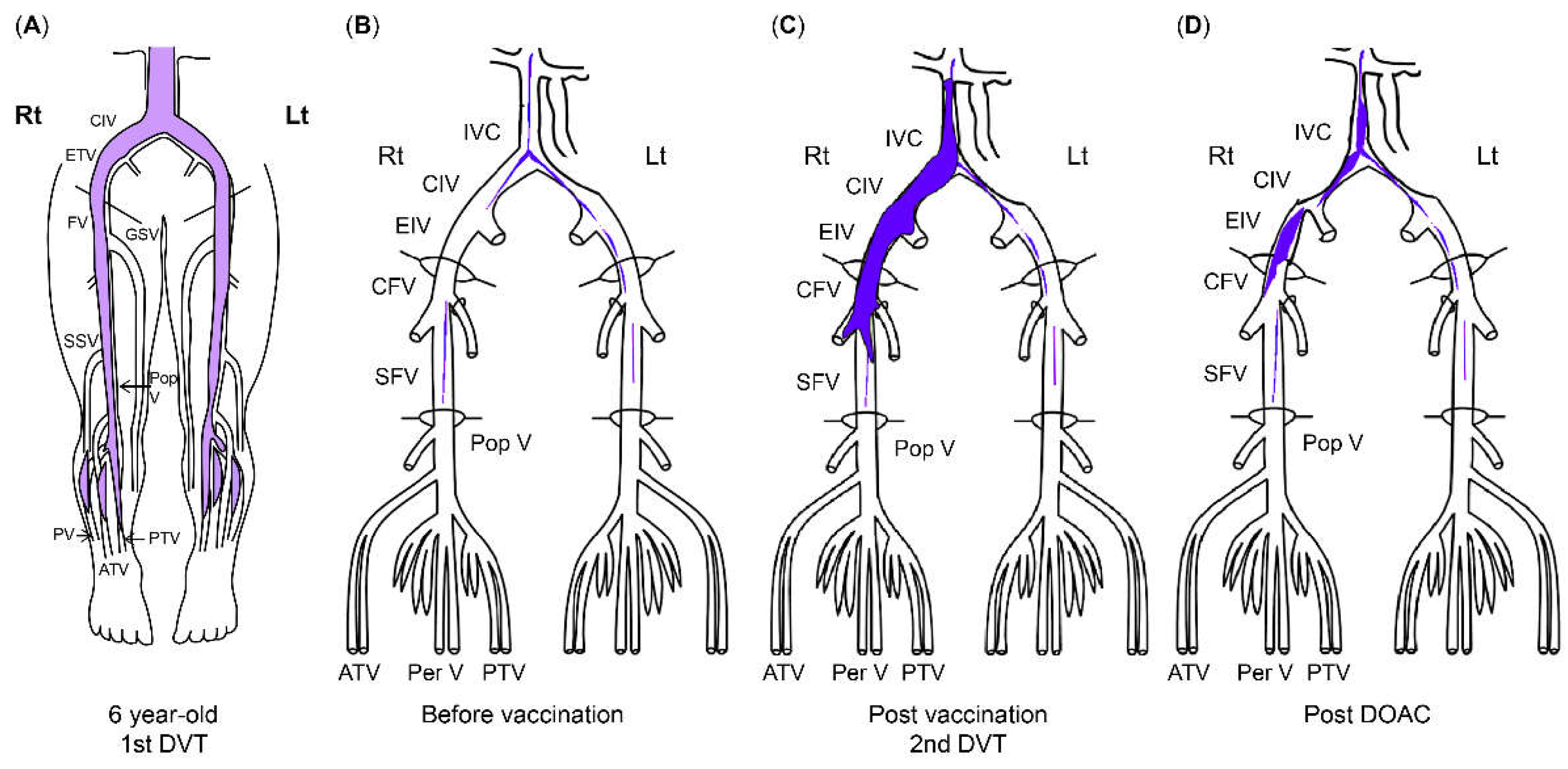

A 6-year-old girl was diagnosed with DVT after experiencing sudden abdominal and right groin pain and vomiting. She had no family history of thrombophilia. Thrombi were found in the right common iliac vein and the inferior vena cava, with concomitant left pulmonary infarction. Blood tests showed a prothrombin time-international normalized ratio of 1.3, an activated partial thromboplastin time of 37.0 sec, a D-dimer level of 88.4 μg/mL, a fibrin degradation product (FDP) level of 221.6 μg/mL, a thrombin-antithrombin III complex (TAT) level of 49.1 ng/mL, a plasmin-α2 plasmin inhibitor complex (PIC) level of 17.6 μg/mL, and a cardiolipin antibody immunoglobulin (Ig)G level of 44 U/mL. Anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin was initiated; the treatment was subsequently changed to warfarin. The pulmonary infarction improved, but the thrombi became organized and persisted continuously. After being diagnosed with DVT at the age of 5, the patient was treated with warfarin to prevent recurrence for 6 years and with beraprost sodium (prostaglandin I2 analog) for 5 years. The patient received no antithrombotic therapy for 4 years after the discontinuation of warfarin, and the thrombosis remained without further DVT for 5 years after cessation of warfarin therapy.

From age 7 to 16, laboratory test results showed a lupus anticoagulant (LA) level of 1.0–1.26 (normal range: < 1.3; assessed via the diluted Russell viper venom time method), an anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I IgG antibody (aβ2GPI-IgG) level < 0.7 U/mL, an anti-cardiolipin antibody IgG (aCL) level of 39–44 U/mL, and a moderately elevated aCL level for more than 2 years, leading to a diagnosis of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome based on the 2006 Sydney criteria. At the age of 9, her level of PF4, a marker of platelet activation, was 57 ng/mL (normal range, ≤ 20 ng/mL). There were no significant changes in activated partial thromboplastin time or LA, aCL, and aβ2GPI-IgG levels at the end of anticoagulant treatment; her PF4 level was not reassessed as thrombosis did not recur.

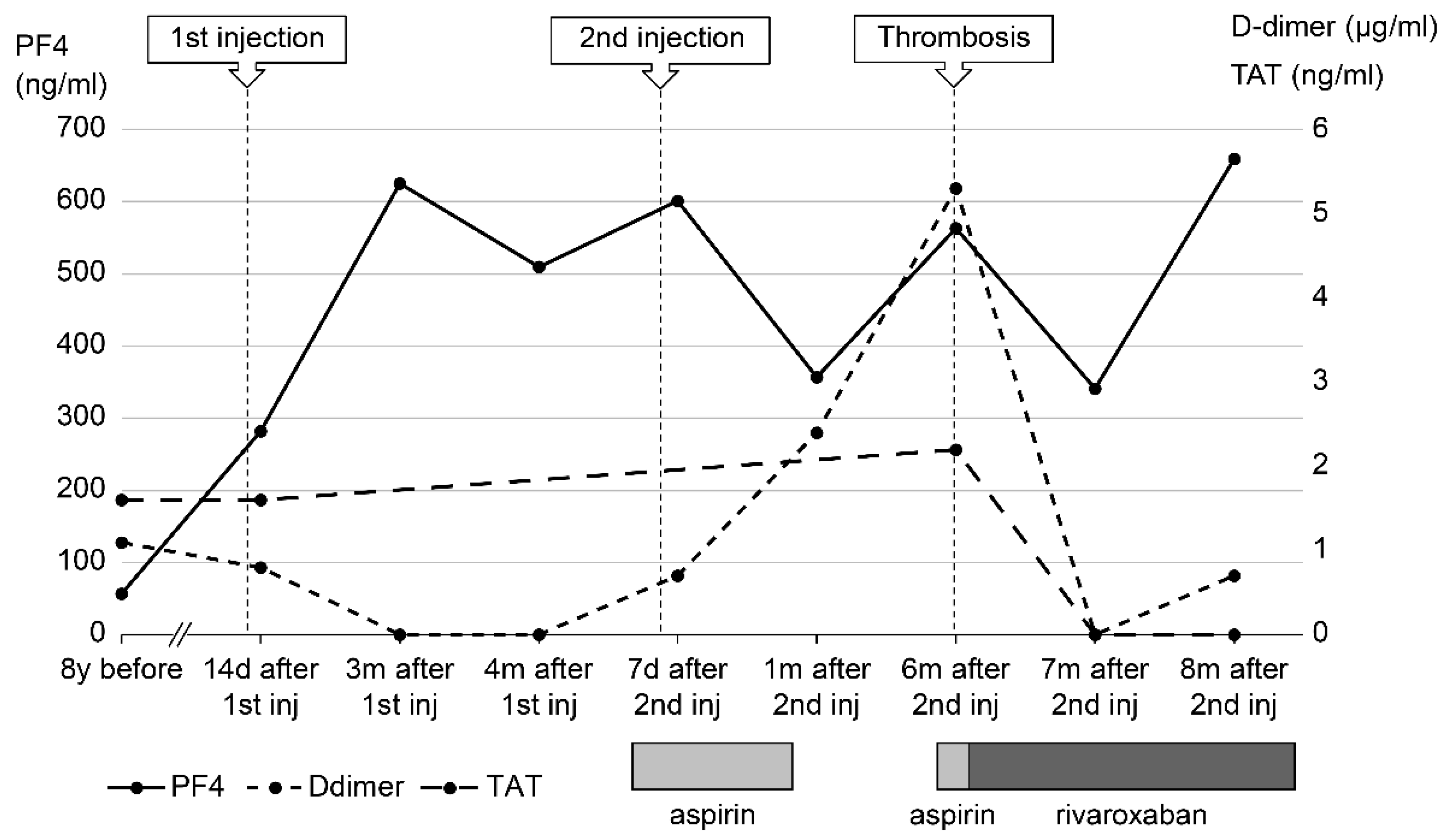

In 2021, Japan enacted a policy offering the BNT162b2 vaccine to 12- to 17-year-olds. At the age of 17, our patient received her first dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine 1 week before her routine outpatient visit (

Figure 1). At that time, many cases of thrombosis caused by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines had been reported; as she had a predisposition to thrombosis, her PF4 was measured for the first time in 8 years. At 2 months post-vaccination, her PF4 level was markedly elevated at 282 ng/mL, and after 3 months it increased to 640 ng/mL; however, as her platelet, FDP, and D-dimer levels were within the reference range, anticoagulants were not prescribed. Because the PF4 level was abnormally high after vaccination, we tested it three times, changing the date, collector, and method of blood collection; the level remained high in all test results, ruling out the possibility of a measurement error. There were no signs of infection such as fever, cough, or diarrhea, no physical findings or blood test results indicative of any infection that could cause thrombosis, and no underlying diseases such as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia. Consequently, we ruled out causes of inflammation other than APS.

Five months after her first vaccination, the patient was advised to opt out of receiving the second vaccination because of her high PF4 levels; however, since two vaccinations were required as a condition for studying abroad, she opted to receive the second dose. Five months after the first vaccination, her PF4 level was 350 ng/mL and decreasing, so a second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine was administered.

At a routine visit 2 months after returning to Japan from studying abroad (6 months after the second vaccination), the patient’s blood tests showed a normal platelet count and coagulation parameters but elevated PF4 levels (540 ng/mL). Aspirin (81 mg) was administered as an antiplatelet agent; on the fourth day of antiplatelet therapy, she developed chest pain, hypoxemia, and pain and edema in her right lower leg. Blood test results showed a TAT level of 2.2 ng/mL, a PIC level of 0.7 μg/mL, an FDP level of 7.4 μg/mL, a D-dimer level of 5.3 μg/mL, a PF4 level of 563 ng/mL, and an aCL level of 28.2 U/mL. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed an increase in the thrombus in the right common iliac vein, and a diagnosis of recurrent deep vein thromboembolism was made (

Figure 2). The patient’s symptoms and laboratory values improved 3 days after the start of direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC; rivaroxaban) administration. Lung single photon emission computed tomography (99mTc-macroaggregated albumin, 81 mKr) revealed no pulmonary infarction.

Blood tests 7 months after the second vaccination showed PF4 levels of 341 ng/mL and βTG levels as high as 845 ng/mL, but TAT (<1.0 ng/mL) and D-dimer (<0.5 μg/mL) levels were below detection. The SARS-CoV-2 S protein antibody titer was 7610 U/mL (<0.80 U/mL).

Nine months after the second vaccination, her vaccine antibody level was 7230 U/mL, and her PF4 level (not related to vaccine antibody level) remained high (659 ng/mL). Currently, her thrombosis is being controlled with rivaroxaban.

4. Discussion

This report presents the case of a patient with pediatric APS who developed DVT 6 months after receiving the second dose of the BNT162b2 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 11 months after her first vaccination. The persistence of high PF4 levels from vaccine administration to DVT recurrence suggested APS exacerbation by the vaccine.

PF4 is released when tissue factor is overexpressed due to vascular endothelial cell injury or monocyte activation, which activates platelets and promotes platelet aggregation. PF4 levels tend to be elevated when platelet activity is triggered by avascularization or infection. DVT is common in patients with trauma who have elevated PF4 and βTG levels, and elevated PF4 levels are correlated with an increased risk of thrombosis [

3]. In this case, the reproducibility of consistently high PF4 levels after BNT162b2 vaccination and the recurrence of DVT when the PF4 levels were high suggested that APS and the BNT162b2 vaccine may be related, indicating that test results for vaccinated patients at risk of thrombosis should be evaluated with caution.

One differential diagnosis of APS is VITT. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-associated VITT has been proposed to occur 4–30 days after vaccination [

4]. The most common causative vaccine is ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 [

1], with few reports of DVT caused by the BNT162b2 vaccine [

5,

6]. Although mRNA vaccines are expected to induce thrombosis by a different mechanism than adenoviral vector vaccines, the mechanism underlying mRNA vaccine associated DVT remains unclear. Many large trials have shown that mRNA vaccines do not increase the risk of DVT [

7]. In the present case, our patient developed DVT 6 months after the second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine (11 months after the first dose), and her disease course was different from that of VITT.

APS is an autoimmune disease in which the production of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) causes arteriovenous thrombosis. Pediatric APS is defined as APS that develops in patients under 18 years of age [

8]; it is rare, making up only 2.8% of all APS patients [

9]. BNT162b2 vaccination was speculated in this case to have caused the second thrombosis that occurred 11 years (age 17) after the first (age 6), as there had been no other recurrences. We hypothesized that the thrombosis occurred because the vaccine exacerbated her APS; exacerbating factors for pediatric APS include trauma, surgery, neoplasms, nephrotic syndrome, congenital heart disease, obesity, central venous catheter use, prolonged immobilization, stays in the intensive care unit, burns, and mechanical ventilation [

10,

11]. Typical risk factors such as malignant disease and tobacco use were not observed in this patient.

In another case report of a 22-year-old woman who developed pulmonary infarction after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination, Balbona et al. reported that APS contributed to her thrombosis because the aCL level was elevated more than 10 times above normal [

12]. Molina-Rios et al. reported the development of systemic lupus erythematosus and secondary APS in a 42-year-old woman 2 weeks after her first BNT162b2 vaccine dose [

13]. Although the reason is unclear, it has been suggested that mRNA vaccines are highly immunogenic and induce marked inflammation, which may promote APS development even in asymptomatic aPL-positive patients [

14]. Additionally, studies on SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines have reported elevated aPL levels after SARS-CoV-2 infection [

15], suggesting it is an exacerbating factor for APS. We hypothesized that the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was highly immunogenic; it induced inflammation, which exacerbated the patient’s APS, resulting in persistent inflammation and prolonged PF4 level elevation.

When platelet activation occurs, platelet microparticles (MPs), known to have high procoagulant activity, are released in large quantities. As a result, they induce excessive thrombin production, which can also induce venous thrombosis.

In addition, high levels of platelet-MPs, tissue factor-MPs, and endothelial-MPs have been reported in a group of patients with APS [

16,

17]. Activation of APS is thought to activate these MPs.

Thus, high PF levels are used as a marker of platelet activation and arterial thrombosis, but persistently high levels may also induce excessive thrombin production and consequent venous thrombosis due to release of platelet MPs.

Monitoring platelet activity after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pediatric patients with APS, such as in the present case, is necessary to prevent DVT. Prospective studies have shown that platelet activation by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is seen with both adenoviral vector and mRNA vaccines [

18], indicating that platelet activity should be monitored after vaccination in patients with thrombophilic disorders. In pediatric patients with a thrombophilic predisposition, platelet activity and coagulability should be monitored before and after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination by assessing PF4, βTG, D-dimer, and TAT levels; as PF4 and βTG levels are useful for predicting DVT after trauma [

3], they may be useful for predicting DVT after vaccination. There is no established index of thromboprophylaxis using PF4 and β-TG after BNT162b2 vaccination, but in our case, both were 10 times higher than their normal ranges; if PF4 and β-TG measure 10 times higher than their normal ranges after several blood tests, treatment intervention may be necessary.

Regarding prophylaxis for thrombosis after mRNA vaccination in patients with APS, it is difficult to choose between warfarin, DOAC, aspirin, and other drugs. In this case, DVT was considered to be associated with vaccine-induced APS exacerbation. The aspirin doses used for primary prophylaxis in a previous report were 80–100 mg daily for adult patients and 3–5 mg/kg/day for pediatric patients [

8]. If a patient develops DVT despite taking aspirin, a switch to DOAC should be considered; as in this case, treatment with the DOAC factor Xa inhibitor may be an option. In a previous case report [

13], warfarin was used to prevent thromboembolism, and 81 mg of aspirin was administered to decrease PF4 activity, resulting in PF4 level reduction to half its original value. However, the patient developed DVT while on aspirin; treatment was subsequently switched to DOAC, which improved clinical symptoms. Some reports suggest that warfarin is preferable to DOAC in patients at high risk of thrombosis, such as those with APS [

19], though the suitability of DOAC treatment for patients demonstrating APS exacerbation after mRNA vaccination, as in this case, requires further investigation. In children with APS, platelet activity should be monitored by measuring PF4 and βTG levels before and after vaccination. If they are high, DVT prophylaxis with low-dose aspirin (in accordance with the thromboprophylaxis for APS) may be recommended until the PF4 level decreases [

8]. Monitoring platelet activity after SARS-CoV2 vaccination in children with APS might not directly prevent DVT, but it can alert clinicians to the need for intervention.

A limitation in this case is that the previous PF4 level measurement occurred 8 years before SARS-Cov2 vaccination and could not be monitored immediately before vaccination. However, it should be emphasized that the patient continued to show PF4 levels that were 20–30 times higher than the reference value after vaccination, and subsequently developed DVT.

PF4 levels may be useful in monitoring the course of thrombosis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in children with APS. Although the mechanism by which mRNA vaccines cause thrombosis has not yet been clarified, coagulation status and platelet activation markers should be monitored in vaccinated patients predisposed to thrombophilia to enable interventions to hopefully prevent DVT.