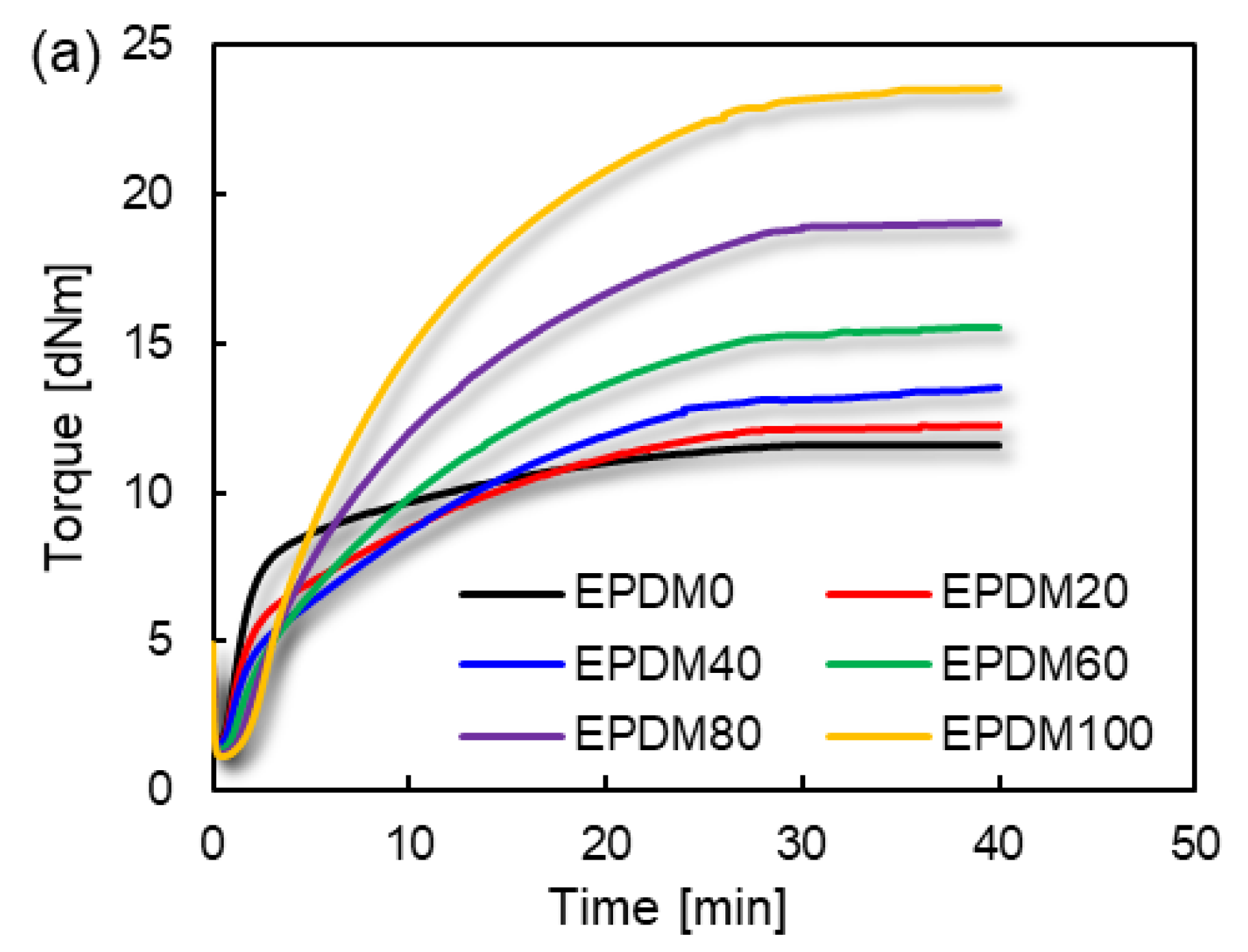

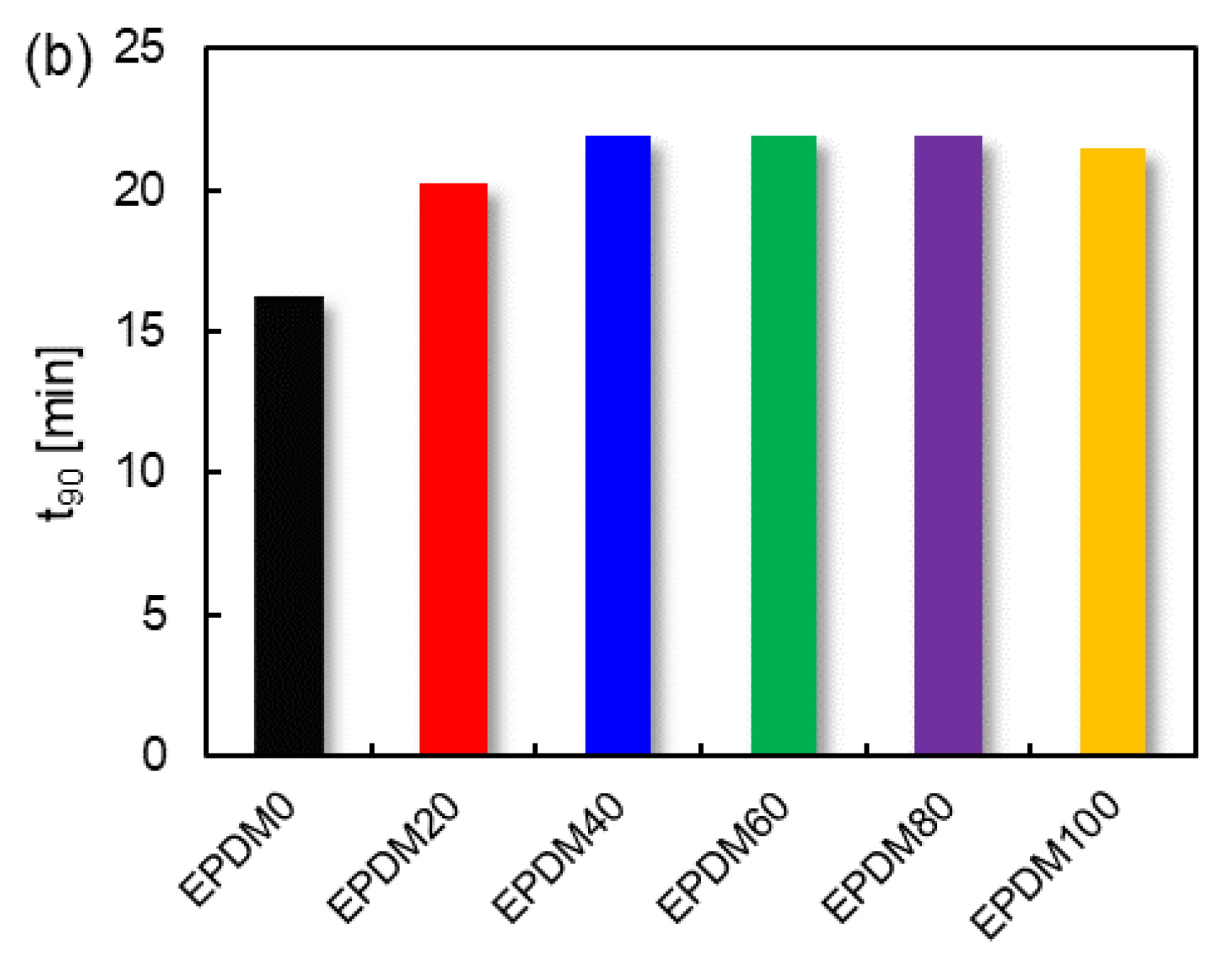

3.2. Damping Characteristics

Damping Mechanism of Rubber Materials

The conformation and conformational entropy change significantly when the macromolecular rubber chain is subjected to force, and part of the energy input from the outside is stored. At the same time, the macromolecular chains rub against each other when they move under the action of external force, converting energy into heat and dissipating it to the outside world. The dissipation of this energy is called damping capacity. Therefore, when the energy input into the system from the outside is known, it is only necessary to measure the energy stored in the system and subtract the energy stored in the system from the energy input from the outside to obtain the energy lost by the system.

The gravitational potential energy of a rubber ball of mass

m at height

h0 is,

m—mass of the rubber ball

g—gravitational acceleration

h0—the height of the rubber ball when it is released

hi—the nth rebound height of the rubber ball

The gravitational potential energy transforms into kinetic energy when the rubber ball falls. The rubber ball will undergo macroscopic deformation due to the action of external force once the ball touched the ground. Microscopically, the macromolecule segments are forced to move, resulting in the friction occurring between adjacent molecular chains. For the filled rubber system, there are frictions contributed from the interaction of molecular chain and filler and of filler and filler [

24]. Due to the internal friction of the rubber ball, it can only reach the height of

h1 (

h1 <

h0) when it rebounds upward from the ground. At this time, the gravitational potential energy of the rubber ball becomes,

Therefore, during the first rebound, the energy loss of the rubber ball is,

Therefore, the energy loss of a rubber ball in a rebound process is directly proportional to the difference between the initial and final height. The rubber ball will then repeat the above process until it stops due to energy depletion.

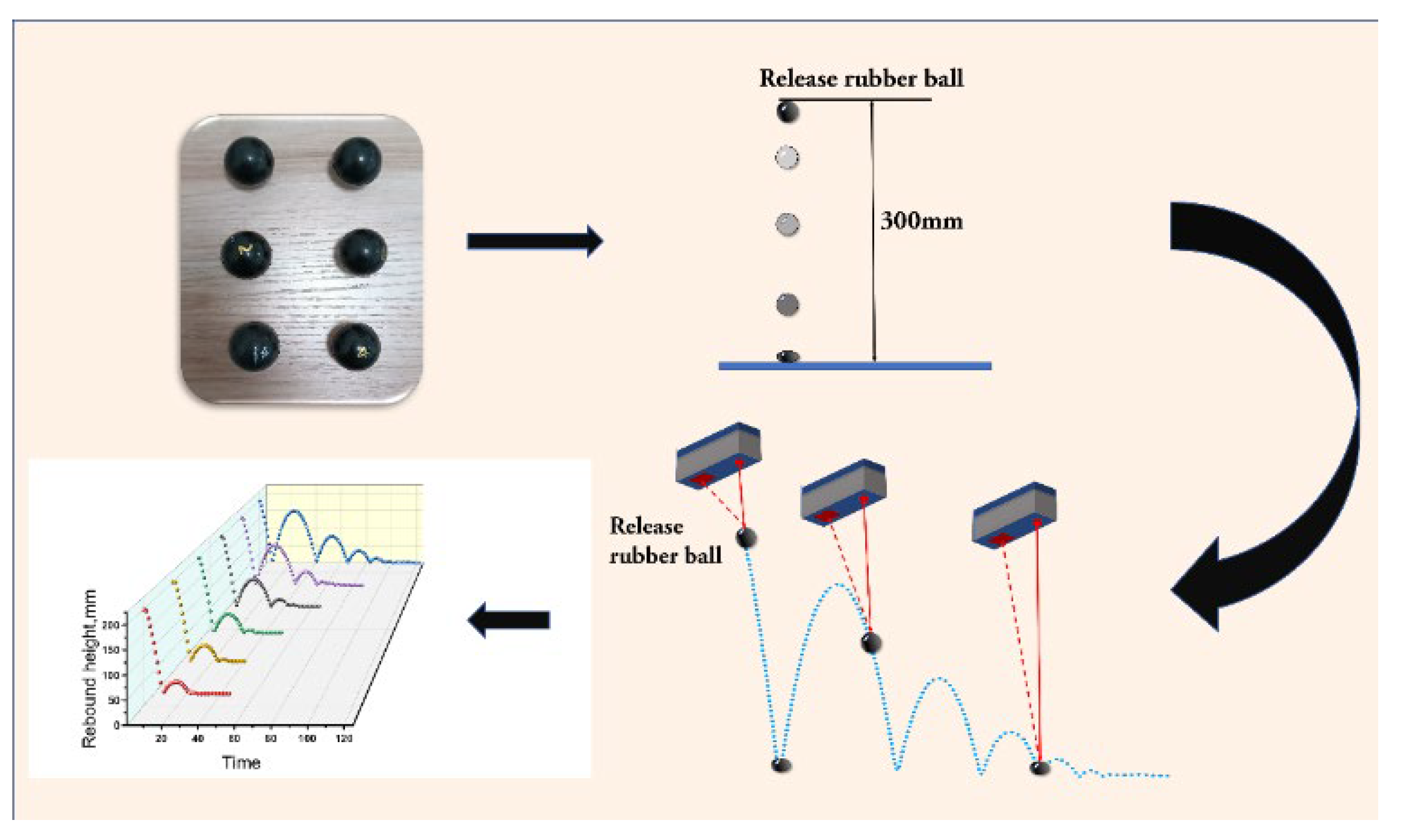

Figure 2 shows the rebound experimental device of the rubber ball, which is composed of a laser sensor connecting to a computer. A rubber ball is placed under the sensor and the released rubber ball will move vertically up and down reciprocally. At the same time, the device captures the motion track of the rubber ball and displays it on the computer.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of rubber ball rebound experiment process and experimental device.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of rubber ball rebound experiment process and experimental device.

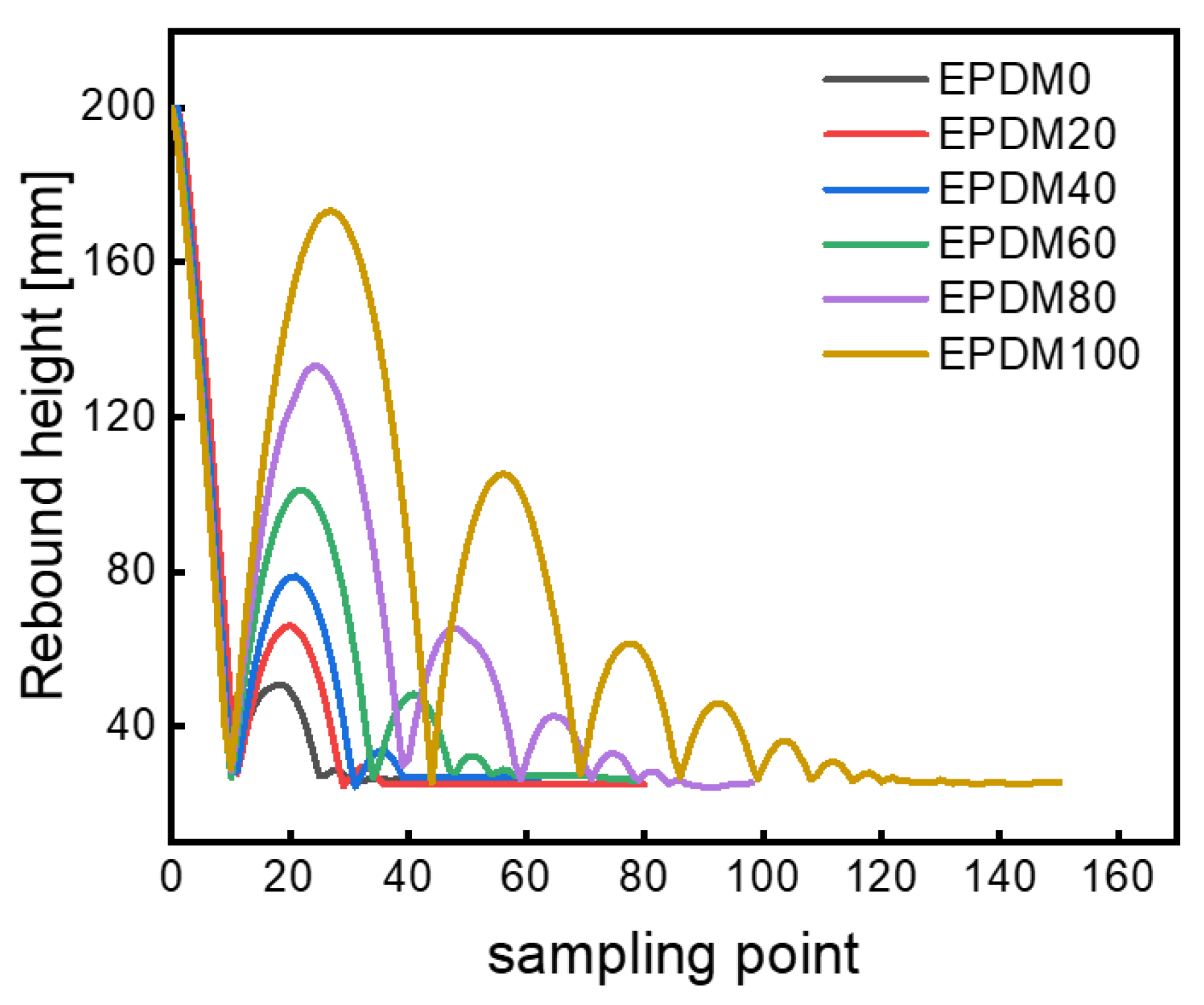

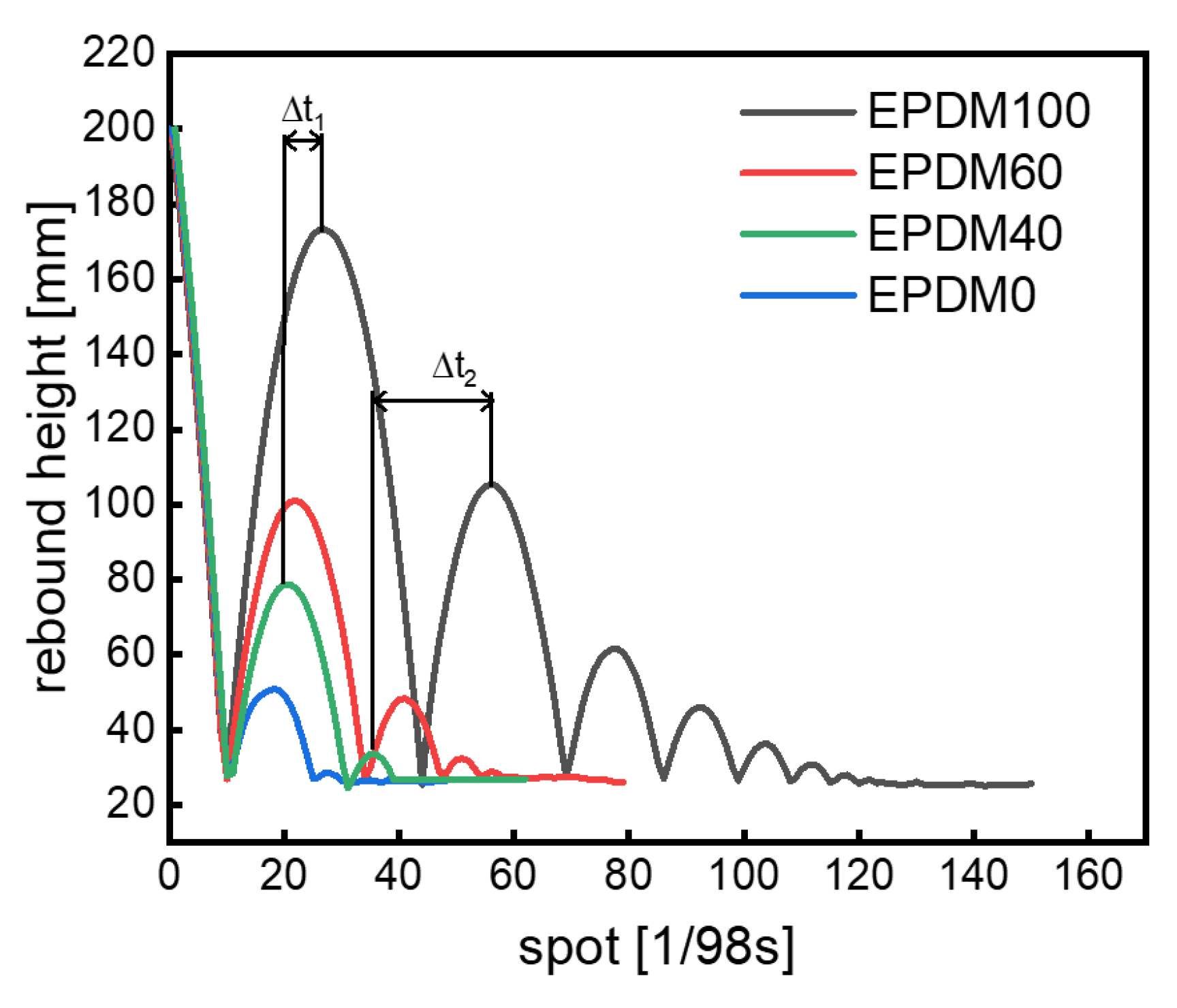

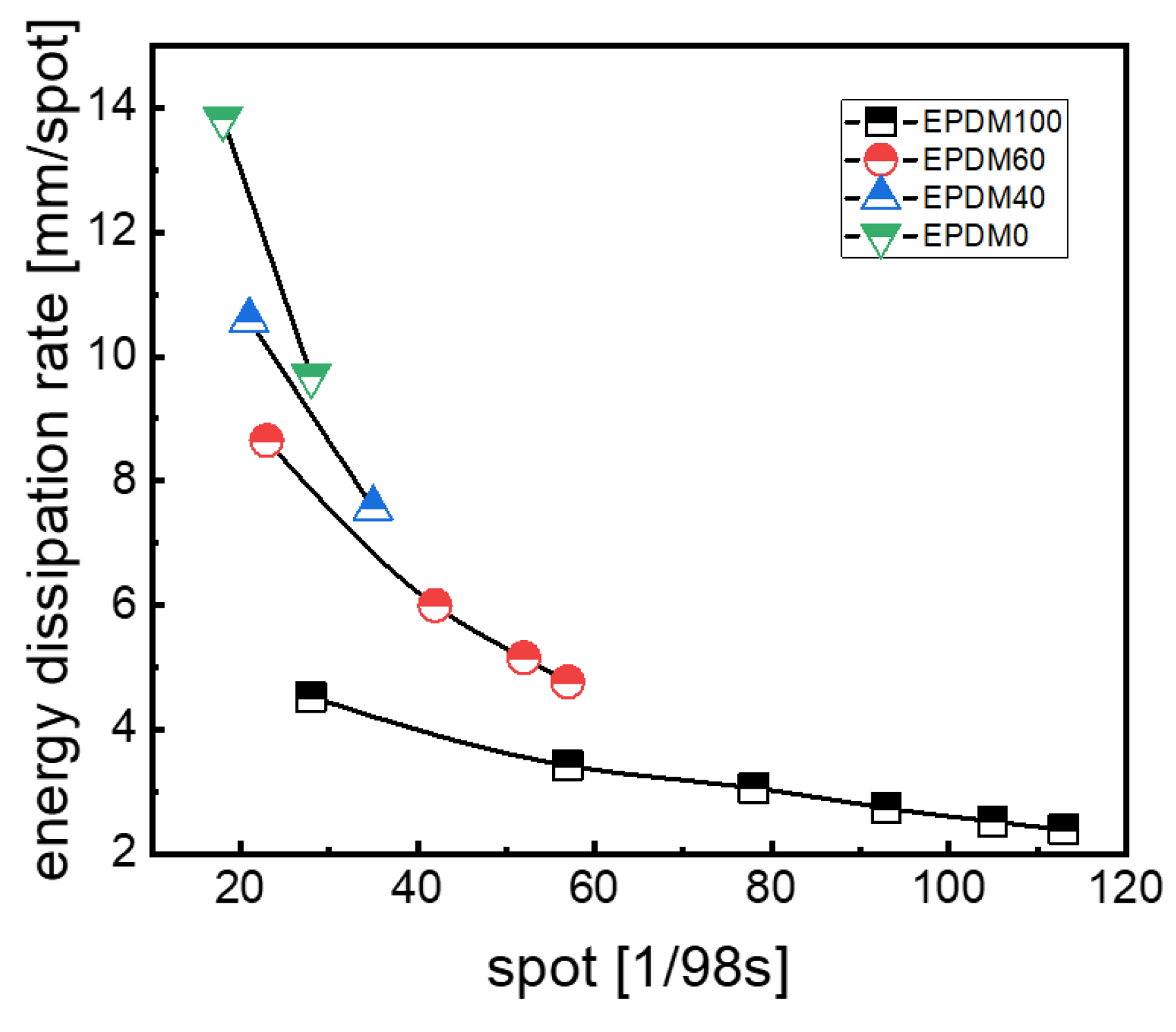

The rebound behaviors of EPDM/CIIR blends are shown in

Figure 3. The curve on the left of the wave peak represents the process of the rubber ball rebounding back from the ground to reach the highest point, and the curve on the right of the wave peak represents the process of the rubber ball falling from the highest point to reach the ground. Hence, the number of wave peaks indicates the rebound times of the rubber ball. In the end, the curve becomes a straight line, meaning that the rubber ball has been completely stationary, and the value of the vertical coordinate at this time indicates the diameter of the rubber ball. Two key points need to be emphasized here. Firstly, the release height of the ball is 300mm, which has exceeded the range of the sensor, and

Figure 3 only shows the data from 0 to 200mm. Secondly, the horizontal coordinate of

Figure 3 indicates the sampling point (which actually means the movement time of the ball), rather than the lateral movement of the ball during the rebound process. In summary, the rebound height, the number of rebound times, and the rebound time (the time experienced by the rubber ball from falling to a complete stop) of the rubber ball can be obtained from

Figure 3.

The Deformation Process of Rubber Ball

It is necessary to analyze the deformation process of the rubber ball in contact with the ground because the energy dissipation occurs in this process.

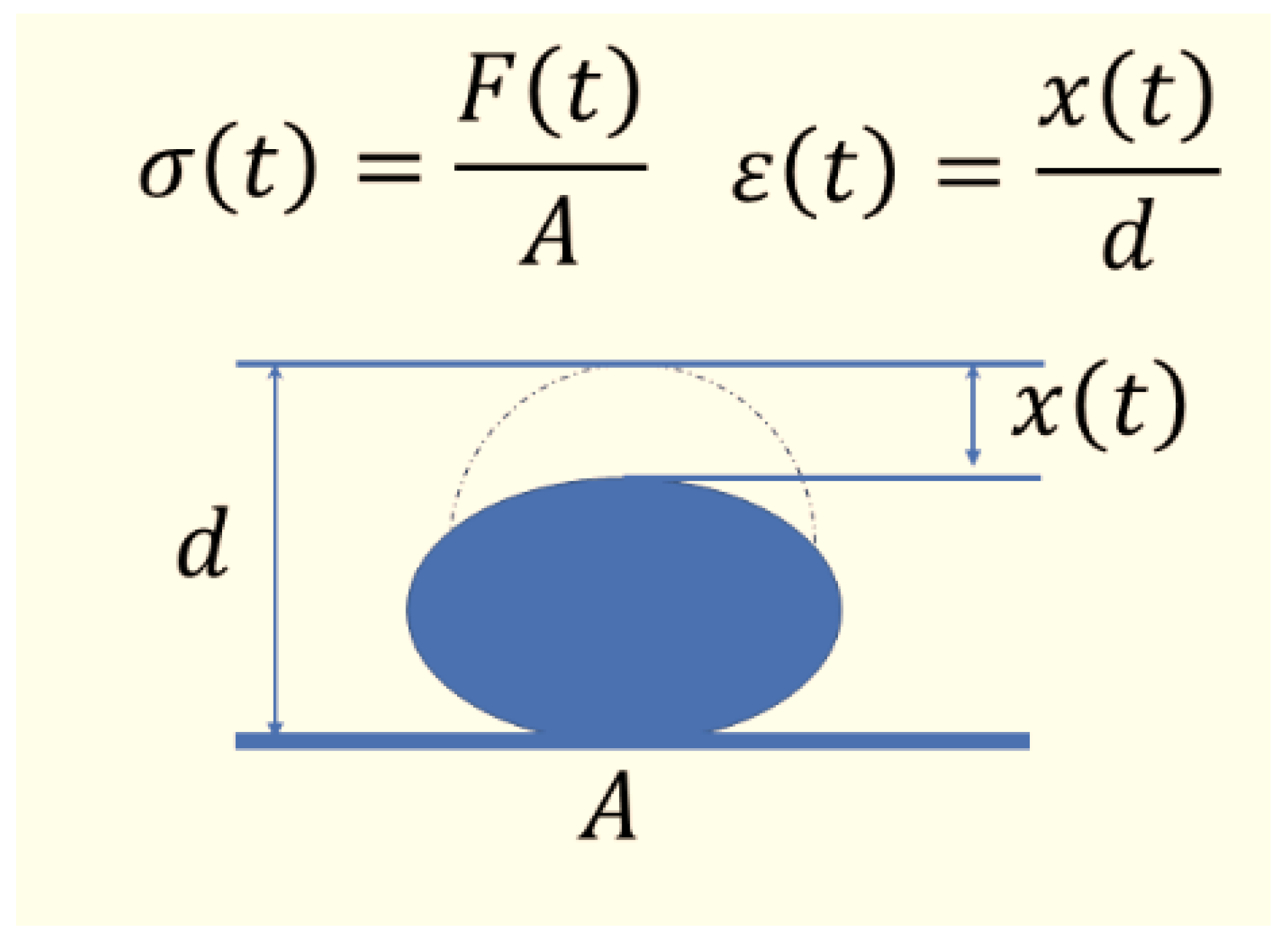

σ(t)—Stress in the rubber ball during deformation

ε(t)—Strain in the rubber ball during deformation

F(t)—The force on the rubber ball during the deformation

A—Area of the rubber ball in contact with the ground during deformation

x(t)—Travel distance of rubber ball vertices

d—Diameter of rubber ball

Figure 4 shows the deformation process of the rubber ball. The rubber ball experiences a negative acceleration

a(t) when it contacts the ground. The force acting on the rubber ball is

F(t). Equation (4) can be obtained according to Newton’s formula,

The force

F(t) causes strain

ε(t) and stress

σ(t) of the rubber ball. When it is linearly deformed. The following Equation (5) is obtained where

A(t) is the contacting area between the ball and ground.

E(t)—Modulus of rubber balls

The acceleration

a(t) corresponds to the second-order derivative of the deformation distance, which has the following Equation (6),

Deformation of strain

ε(t) is approximately obtained by the ratio of the deformation distance at the top of the rubber ball to the diameter of the ball, as depicted in Equation (7),

Equations (4)–(7) constitute a description of the deformation motion of the rubber ball when it contacts the ground.

By substituting Equation (5) and (6) into Equation (7) one can obtain Equation (8), which can be solved when both E(t) and A(t) are known. E(t) varies with the type and proportion of the constituents in the rubber ball, and the magnitude of modulus E(t) affects the change of contact area A(t). The lower the modulus E(t), the larger the deformation of the rubber ball and thus the larger the contact area. The Equation (8) can be solved by the contact area A(t) and the modulus E(t), i.e., the deformation frequency of the rubber ball on contacting the ground. This means that the deformation frequencies of rubber balls differ for different materials even if the rubber balls are released at the same height. In summary, the rebound height of the rubber ball indicates the damping capacity of the rubber under a specific external excitation (the magnitude of the excitation is determined by the release height of the rubber ball), rather than the damping capacity at a specific frequency.

Additionally, the first rebound height of the pure EPDM ball is the highest, while the pure CIIR ball is the lowest (

Figure 3). The rebound height decreases with the increase of CIIR content, indicating that the pure CIIR ball dissipates the most energy in the deformation process and has the greatest damping capacity due to the dense side methyl groups in the molecular chains of chlorobutyl rubber. The intense friction and strong energy dissipation between the CIIR molecular chains occur under external action. For the case of EPDM, however, the small number of methyl groups in the highly regular molecular chains result in less energy dissipation under external force, and thus the rebound height of the EPDM ball is the largest.

There are two ways to solve Equation (8). The first one is the finite element method, which is discussed in detail in the paper by R. Weiss. The second approach is to use constants to approximate the time-related parameters. Wrana analyzed the deformation process of a rubber ball in contact with the ground. The contact area

A(t) and the modulus

E(t) were hypothesized as constant values and the frequency of the periodic deformation of the rubber ball was further derived, as shown in Equation (9).

ω—The frequency of the periodic deformation

E0—Young’s modulus of rubber materials

ρ—Density of rubber balls

d—Diameter of rubber ball

The frequency of the deformation of the rubber ball is related to E0, ρ and d. The rebound height of the rubber ball can be predicted by combining the master curve of the material at 20 °C and bringing the relevant parameters into Equation (9).

The method of approximating the variables as constants allowed the researchers to obtain the rebound height of the rubber ball only over a relatively wide range of frequency. In this paper, we propose a method to predict the rebound height of rubber balls from another perspective.

3.3. Prediction of the Rebound Height

According to the literature [

25], when the rubber ball falls at the same height, the energy dissipated can be approximated as a loss factor tanδ with the following Equation (10).

Then, Equation (11) is readily obtained by transforming Equation (10).

Multiplying both sides of Equation (11) by x one can obtain Equation (12).

Obviously, the following Equation (13) must be true.

Hence, Equation (14) is obtained by adding Equation (12) to (13).

Equation (15) is then obtained from simple transformation of Equation (14).

x—Mass fraction of rubber 1 in the raw rubber system of the blends.

y—Mass fraction of rubber 2 in the raw rubber system of the blends.

tanδ1 and tanδ2—Loss factors of rubber 1 and 2 at the same frequency, respectively.

tanδ3—Loss factor of blends composed of rubber 1 and 2.

Δh1 and Δh2 —The height differences before and after the rubber 1 and 2 ball rebound, respectively.

Equation (16) describes the loss factor of the blends as a function of the loss factor of the pure rubber.

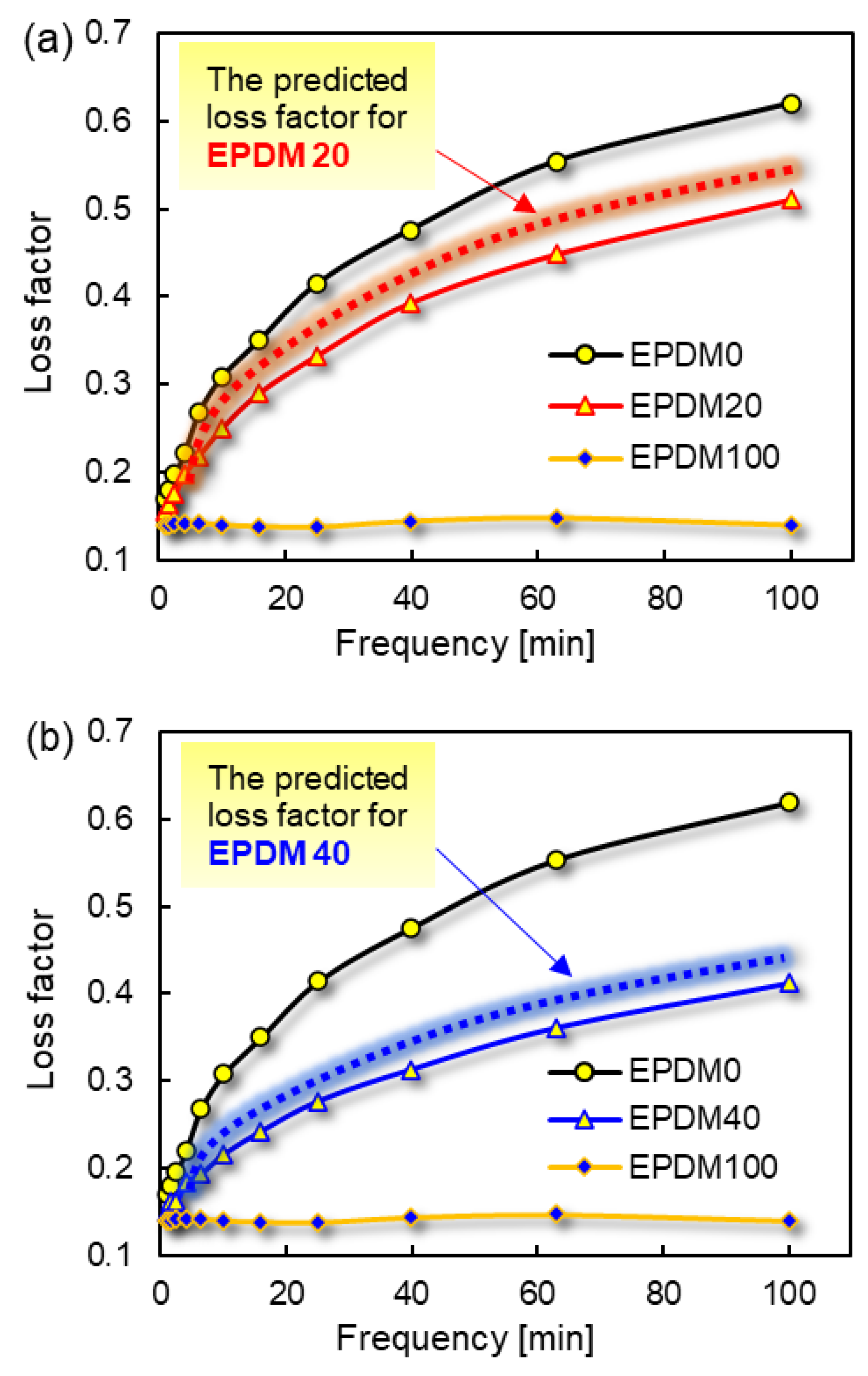

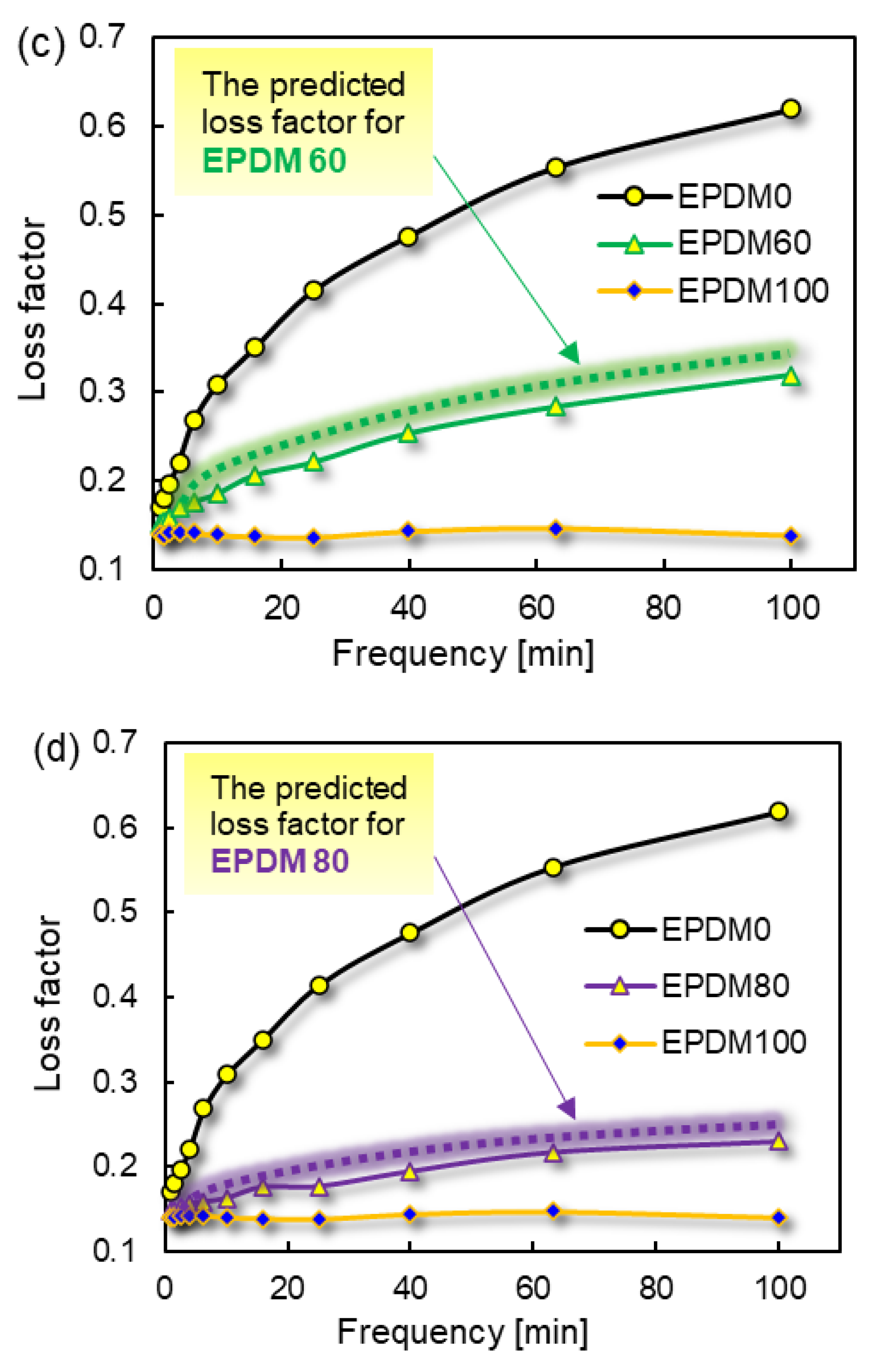

The loss factors of pure rubber and blends were tested at frequency from 1 Hz to 100 Hz at room temperature. The loss factors of the rubber blends were predicted and compared according to Equation (16). The results are shown in

Figure 5.

The loss factors of the rubber blends with EPDM content of 20wt%, 40wt%, 60wt% and 80wt% were predicted and correlated with frequency. The predicted values follow the same tendency with the experimental results even though they keep slightly higher than the measured data. In the same way,

∆h of the rubber ball should also follow the corresponding law. Thus, Equation (17) can be obtained.

By a simple conversion, it can be deduced that the rebound height of the rubber ball also conforms to Equation (17), and thus Equation (18) is obtained.

hi—First rebound height of the rubber ball with EPDM content i in the raw rubber system.

hE—The first rebound height of pure EPDM ball.

hC—The first rebound height of pure EPDM ball.

x—Mass fraction of EPDM in raw rubber i.

y—Mass fraction of CIIR in the raw rubber (1-i).

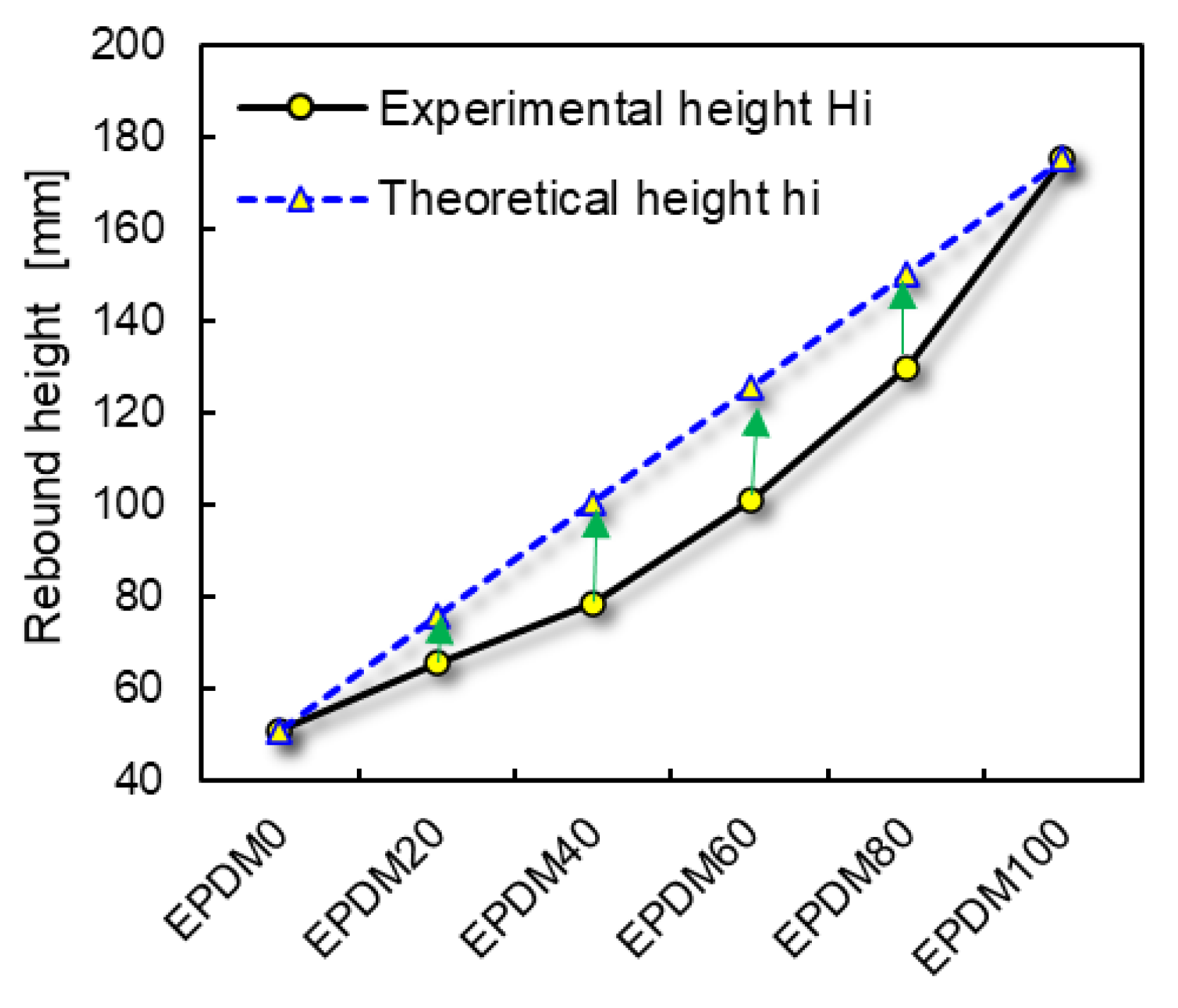

The rebound heights of the theoretical (

hi) and measured (

Hi) values and the difference between

Hi and

hi for the rubber balls are listed in

Table 2.

The difference of the theoretical and measured rebound heights (hi-Hi) firstly increases and then decreases with the increase of EPDM content in the raw rubber system. In other words, the larger the difference between the two rubber ratios, the lower the error of the Equation (18).

The deviation of the theoretical rebound height can be explained by the following reasons. The migration of the vulcanizing agent due to the different solubility in EPDM and CIIR leads to a change in the crosslinking density of the two rubber phases in blends compared with that of the pure rubber [

26]. The rubber phase with high solubility to the vulcanizing agent moves to a higher glass transition temperature (Tg) because the crosslinking density becomes larger, the chain segment movement becomes more impeded and the free volume is thus further reduced. The Tg of the other rubber phase moves to lower temperatures, hence the damping capacity of the rubber blend changes.

Thus, Equation (18) presupposes that the crosslinking density of the two rubber phases in the rubber ball with EPDM content

i is the same as that of the respective single rubber. In this work, the different solubility of the vulcanizing agent in the two rubber leads to changes in the crosslinking density of the two rubber phases in the blends, which causes changes in the damping properties [

27]. This is the reason for the deviation of the measured rebound height from the theoretical calculation. Therefore, a modified Equation (19) is obtained by adding a correction term

c into Equation (18) as following.

c denotes the difference between the theoretical dynamic mechanical properties and the actual dynamic mechanical properties of the material with EPDM content i. In this experiment, the predicted loss factor is smaller than the actual one.

As discussed above, we have got the knowledge that the rebound height represents the damping capacity of the rubber ball under specific excitation (the value of the excitation is determined by the release height of the rubber ball). In other words, each ball receives the same excitation when it falls at the same height. The deformation frequencies, however, are varied with the rubber balls of different blending ratios. In addition, it is difficult to determine the value of the correction term c based on the frequency-dependent measurement data at room temperature because the deformation frequency of the ball is hard to determine.

Figure 6.

Theoretical and measured rebound heights of the rubber ball.

Figure 6.

Theoretical and measured rebound heights of the rubber ball.

In order to determine the value of c, the method of taking the average value is adopted in this paper.

Then, Equation (21) is obtained.

Actually, the correction term c is determined by various factors, the nature of rubber and formulations for examples, and thus it reveals various values for different kinds of rubber blends which will be discussed in detail in the follow-up work. Equation (21) provides a simple method to predict the damping capacity of a rubber that is measured by the rebound height and plays a key role in the formulation design of viscoelastic damping rubber materials.