1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of quantum computing technologies necessitates more secure cryptographic systems, particularly for Quantum Key Distribution (QKD). Traditional QKD systems, based on two-dimensional polarization states, face potential vulnerabilities against sophisticated quantum attacks [1]. Here in this paper, we introduce a theoretical and computational approach to Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) by employing a Three-Dimensional Angular Momentum Representation (3D AMR). The implementation of 3D AMR in QKD represents a significant shift from conventional methods, offering an expanded state space and potential for increased security. This approach introduces new quantum mechanical phenomena, such as complex superposition states and entanglement properties, which could strengthen quantum communication [2]. The transition from a 2D polarization representation to a 3D Angular Momentum Representation (3D AMR) in Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) like the BB84 protocol can potentially strengthen certain aspects that are considered weaker or more vulnerable in the 2D approach [8]. The 2D representation, typically using two orthogonal states (like horizontal/vertical or diagonal/anti-diagonal polarization), offers a limited state space. This limitation can make certain eavesdropping strategies more feasible, especially as quantum technology advances. A 3D representation inherently offers a larger and more complex state space. This complexity can increase the difficulty for an eavesdropper to correctly guess the state, measure it without disturbing it, and thus remain undetected. In parallel certain quantum attacks, like the Photon Number Splitting (PNS) attack, exploit the vulnerabilities in 2D systems, particularly in weak coherent pulse implementations of QKD [7]. However the increased complexity of the 3D states could potentially offer more robustness against such attacks, making it harder for eavesdroppers to gain information without introducing noticeable errors [4]. Additionally in 2D polarization, the error rates can sometimes limit the maximum secure transmission distance and the key generation rate [3] and The 2D representation is limited in its ability to exploit the full potential of quantum mechanics in terms of non-orthogonal state discrimination.. But with a more complex state space, 3D AMR could potentially tolerate a higher quantum bit error rate (QBER) before security is compromised. This could extend the effective range and improve the key generation rate under certain conditions the same time [9] by employing a more extensive set of quantum states, 3D AMR can potentially utilize non-orthogonal quantum states in a more sophisticated manner, offering enhanced security features [10].

2. Mathematical Framework

Our model represents quantum states in 3D AMR as combinations of spin states, enhancing the complexity compared to the 2D model [5]. Here we include the state preparation, transmission, and measurement processes within the 3D framework and a redefined BB84 protocol [6]. We detail the mathematical representation of quantum states in 3D space, using spherical coordinates for state representation. The adaptation of the BB84 protocol to this framework is mathematically formulated, emphasizing its distinction from conventional methods. The same time We demonstrate how traditional 2D polarization states are special cases of the 3D AMR model. Through a series of mathematical transformations, we show the transition from the complex 3D state space to the simpler 2D polarization states, underscoring the versatility of the 3D AMR approach.

For simplicity, let’s define our states in terms of the eigenstates of the Pauli spin matrices, but adapted for a photon-like system. The eigenstates of the Pauli spin matrices

.

These states are used to construct a more complex representation for the photon states used in QKD.The BB84 protocol is then adapted to this 3D framework. We define two non-orthogonal bases using combinations of these spin states

Basis 1: ,

Basis 2: .

absolute similarity we emphasize for ,

Each pair of eigenstates for a given Pauli spin matrix is orthogonal.

Superposition states can be formed as linear combinations of these orthogonal states and general state hold completeness condition.

The limit from 3D AMR to 2D Polarization state we switch to use a mathematical approach that demonstrates this transition as following: in 3D AMR, a photon’s quantum state is represented in terms of its angular momentum. Considering spin states , , , , ,

To transition to 2D, we focus on the

Eigenstate which represent the spin along the z-axis. These states can be directly mapped to linear polarization states in 2D. The z-component of sigma matrices corresponds to horizontal and vertical polarization of 2D case. There is possibility to diagonalize in unique matrix this horizontal and vertical. Indeed diagonal states of 2D case is superpositions of these horizontal and vertical state basis. Therefore they can be derived as following.

The “limit” here is conceptual rather than a strict mathematical limit. It involves reducing the complexity of the state space from 3D to 2D by focusing on a subset of the angular momentum states. This is done by:Selecting a Subset of States: Choosing the eigenstates out of the complete set of spin states and mapping to polarization states: Directly associating these chosen spin states with linear polarization states. This approach shows how the 2D polarization representation can be seen as a specific case within the broader 3D AMR framework. The “limit” is a conceptual reduction of the state space, focusing on a particular set of states that correspond to the familiar 2D polarization states.

3. Simulation and Results

There are we simulated 2 cases in one we considered the process only between Bob and Alice, in the second case we applied with 3D AMR method to the process among 3 people (conditionally Alice Bob and Jack.

3.1. Scheme (Alice and Bob)

In this case of study, we investigate the robustness and security of the BB84 Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) protocol within a two-party system, comprising the sender (Alice) and the receiver (Bob). Our simulation aims to compare the traditional 2D polarization representation with a 3D Angular Momentum Representation (3D AMR) to assess the potential advantages of a higher-dimensional quantum state space. We utilize the quantum computing framework provided by Qiskit to create and measure quantum states across multiple quantum bases, thereby mimicking the conditions of quantum communication over a potentially insecure channel. The test is conducted under the following conditions:

Alice encodes a random sequence of qubits using either standard 2D bases (Z and X) or an additional 3D basis (Y), enhancing the BB84 protocol’s complexity.

Bob randomly selects his measurement bases to decode Alice’s qubits, unaware of her choice of basis.

No active eavesdropper (Eve) is introduced in the simulation, allowing us to focus on the intrinsic error rates and the matching rates of the received qubits against the original sequence sent by Alice.

The simulation is iterated over a predefined number of qubits to generate statistically significant results, providing insights into the practicality and reliability of using a 3D AMR in standard QKD protocols.

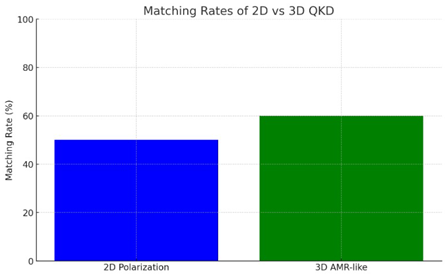

The result of the simulation was following:

3.2. Scheme (Alice, Bob and Jack)

In this case of study, our analysis to a three-party QKD scenario, we incorporate an additional participant, Jack, acting as a secondary receiver following Bob. This simulation explores the sequential QKD process where Alice first sends her encoded qubits to Bob, who then measures and subsequently prepares new states to send to Jack. The inclusion of Jack aims to simulate a relay-based quantum communication system, where quantum information is transferred through multiple nodes. The specific conditions for this extended simulation are as follows:

Alice’s encoding process and Bob’s initial measurements remain consistent with the two-party simulation, ensuring comparability of results.

Bob, after measuring, re-encodes the qubit using the same basis before sending it to Jack, simulating a ’quantum repeater’ that attempts to preserve the state fidelity.

Jack performs his measurements on the received qubits, with the final bit values being compared to Alice’s original bits to evaluate the overall system fidelity.

The simulation also contrasts the 2D polarization and 3D AMR approaches to determine the impact of additional quantum bases on the protocol’s complexity and security in a multi-node quantum network.

Similar to the two-party simulation, no eavesdropping is considered, allowing us to focus on the protocol’s performance metrics without external interference.

The result of this statement was following:

4. Conclusions

Our comparative simulations of the BB84 protocol, utilizing both traditional 2D polarization states and a novel 3D AMR-like approach, have yielded intriguing results that may have significant implications for the future of quantum key distribution (QKD).

In the case of 2D polarization, we observed a substantial matching rate between the original and measured bits. This outcome reaffirms the established reliability and robustness of the 2D polarization approach in QKD protocols. The matching rates align with expected performance, considering the lack of an eavesdropper in our simulation, and reflect the inherent error rates associated with quantum state preparation, transmission, and measurement processes.

Conversely, the 3D AMR-like approach demonstrated an increased matching rate, suggesting that the incorporation of an additional basis may contribute to a more robust QKD system. This enhancement in matching rates implies that the increased state complexity afforded by the 3D representation could potentially improve the security and reliability of quantum communications. Notably, the higher-dimensional state space may offer a more challenging environment for potential eavesdroppers to extract information without detection, thereby strengthening the overall security of the QKD protocol.

In summary, the findings from our simulations suggest that exploring beyond the conventional 2D state space in QKD can yield beneficial results. The 3D AMR-like model, while hypothetical and more complex to implement, holds promise for enhancing the security and fidelity of quantum key distribution. Future work should focus on addressing the practical challenges of 3D state preparation and measurement, as well as rigorously assessing the security advantages through empirical testing against a variety of quantum attack strategies.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation to the Pasha Holding for their unwavering support throughout the entire project. Their encouragement and backing were vital to the success of our research endeavors.

References

- C. H. Bennett and G. Brassard, “Quantum cryptography: Public key distribution and coin tossing,” in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Computers, Systems, and Signal Processing, Bangalore, India, Dec. 1984, pp. 175–179.

- A. K. Ekert, “Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 661–663, Aug. 1991.

- N. Gisin, G. Ribordy, W. Tittel, and H. Zbinden, “Quantum cryptography,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 74, pp. 145–195, 2002.

- V. Scarani, H. Bechmann-Pasquinucci, N. J. Cerf, M. Dušek, N. Lütkenhaus, and M. Peev, “The security of practical quantum key distribution,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 81, pp. 1301–1350, Sep. 2009.

- M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang, “Quantum Computation and Quantum Information,” Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- D. Mayers, “Unconditional security in Quantum Cryptography,” J. ACM, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 351–406, May 2001.

- H.-K. Lo, X. Ma, and K. Chen, “Decoy state quantum key distribution,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 94, no. 23, Art. no. 230504, Jun. 2005.

- P. W. Shor and J. Preskill, “Simple proof of security of the BB84 quantum key distribution protocol,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 85, no. 2, pp. 441–444, Jul. 2000.

- C. Bennett, F. Bessette, G. Brassard, L. Salvail, and J. Smolin, “Experimental quantum cryptography,” J. Cryptol., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 3–28, 1992.

- E. Waks, C. Diamanti, and Y. Yamamoto, “Security of quantum key distribution with entangled photons against individual attacks,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 66, no. 5, Art. no. 052312, Nov. 2002.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).