Submitted:

17 April 2024

Posted:

19 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

Conclusions

CRediT authorship contribution statement Ada Ruth Bertoti

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Declaration of competing interest

References

- Álvaro, M.; Ferrer, B.; Garcı́a, H.; Narayana, M. Screening of an ionic liquid as medium for photochemical reactions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 362, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, M.; Carbonell, E.; Ferrer, B.; Garcia, H.; Herance, J.R. Ionic Liquids as a Novel Medium for Photochemical Reactions. Ru(bpy)32+/Viologen in Imidazolium Ionic Liquid as a Photocatalytic System Mimicking the Oxido-Reductase Enzyme. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006, 82, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagni, R.M.; Gordon, C.M. . Photochemistry in Ionic Liquids, In CRC Handbook of Organic Photochemistry and Photobiology, 2nd ed.; Horspool, W.H., Lenci, F., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2003; pp. 5.1–5.21. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, S.C.; Jones, P.B. Ionic liquid soluble photosensitizers. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 7425–7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagni, R.M.; Mamantov, G.; Lee, C.W.; Hondrogiannis, G. The Photochemistry of Anthracene and Its Derivatives in Room Temperature Molten Salts. Proc. Electrochem. Soc. 1994; 638, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoti, A.R.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. Determination of absolute rate constant for the phenolic hydrogen abstraction reaction by the triplet excited state of xanthone in acetonitrile and in ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate [bmim.PF6]. Quim. Nova 2013, 36, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Moya, J.; Kirk, K.L. Photochemical Schieman reaction in ionic liquids. J. Fluor. Chem. 2007, 128, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.L.; Erdner, K.R.; Jones, P.B. Photoreduction of benzophenones by amines in room-temperature ionic liquids. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 917–919. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, C.M.; McLean, A.J. Photoelectron transfer from excited-state ruthenium (II) tris (bipyridyl) to methylviologen in an ionic liquid. J. Chem Soc, Chem. Commun, 2000; 1395–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Desikan, V.; Han, X.; Xiao, T.L.; Ding, R.; Jenks, W.S.; Armstrong, D.A. Use of chiral ionic liquids as solvents for the enantioselective photoisomerization of dibenzobicyclo [2.2.2] octatrienes. Org. Letters 2005, 7, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoti, A.R.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. Ionic liquid [bmim.PF6]: a convenient solvent for laser flash photolysis studies. Quím. Nova 2009, 32, 1934–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.D. Rogers, K.R. R.D. Rogers, K.R. Seddon, editors. Ionic Liquids IIIB: Fundamentals, Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities: Properties and Structure. (ACS Symposium Series 902) 2005, American Chemical Society, Washington.

- Bibaut-Renauld, C.; Burget, D.; Fouassier, J.P.; Varelas, C.G.; Thomatos, J.; Tsagaropoulos, G.; Ryrfors, L.O.; Karlsson, O.J. Use of α-diketones as visible photoinitiators for the photocrosslinking of waterborne latex paints. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2002, 40, 3171–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nau, W.M.; Scaiano, J.C. Oxygen Quenching of Excited Aliphatic Ketones and Diketones. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 11360–11367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, N.; Bartlett, P.D. Photooxidation of olefins sensitized by alpha-diketones and by benzophenone. A practical epoxidation method with biacetyl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 4193–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiolini, L.; Caretti, D.; Salatelli, E. Synthesis and photoinitiation activity of radical polymeric photoinitiators bearing side-chain camphorquinone moieties. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2000, 201, 2646–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lucas, N.C.; Silva, M.T.; Gege, C.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. Steady state and laser flash photolysis of acenaphthenequinone in the presence of olefins. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 2795–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.F.; Glynn, S.P. Photorotamerism of aromatic alpha-dicarbonyls. J. Phys. Chem. 1975, 79, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.S.; Natarajan, L.V. Comprehensive absorption, photophysical/chemical, and theoretical study of 2-5-ring aromatic hydrocarbon diones. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.S.; Natarajan, L.V.; Lenoble, C.; Harvey, R.G. Photophysics, photochemistry, and theoretical calculations of some Benz [a] anthracene-3, 4-diones and their significance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 7163–7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, E.; Tsai, L. Spectroscopic examination of the lower excited states of alpha-diketones. Camphorquinone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 7123–7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumper, C.W.N.; Thurston, A.P. Electric dipole moments and molecular conformations of benzophenones, benzils, benzhydrols, and benzoins. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1972, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, N.J.; Blout, E.R. The Ultraviolet Absorption Spectra of Hindered Benzils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, N.J.; Mader, P.M. The Influence of Steric Configuration on the Ultraviolet Absorption of 1,2-Diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 5388–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malval, J.-P.; Dietlin, C.; Allonas, X.; Fouassier, J.-P. Sterically tuned photoreactivity of an aromatic α-diketone family. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2007, 192, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, M.B. Recent photochemistry of α-diketones. Top. Corr. Chem. 1985, 129, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Verheijdt, P.L.; Cerfontain, H. Dipole moments, spectroscopy, and ground and excited state conformations of cycloalkane-1, 2-diones. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1982; 2, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Galasso, V.; Pappalardo, G.C. Dipole moments and absorption spectra of heterocyclic diketones. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1976, 2, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, R.; Liljefors, T. Conformations and barriers to inversion of some cyclic seven-membered α-diketones. A study by dynamic nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and molecular mechanics calculations. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1983, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.F.; Newkome, G.; Mattice, W.L.; McGlynn, S.P. Excited electronic states of the.alpha.-dicarbonyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 4385–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.R.; Leermakers, P.A. Emission spectra and excited-state geometry of.alpha.-diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 4380–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, N.J.; Kresge, A.J.; Oki, M. The Influence of Steric Configuration on the Ultraviolet Absorption of Fixed Benzils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 5078–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.C.; Mukherjee, R.; Chowdhury, M. Spectra of Benzil. J. Chem. Phys. 1969, 51, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Das, P.K. Photoreduction of benzophenone by amino acids, aminopolycarboxylic acids and their metal complexes. A laser-flash-photolysis study. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1984, 80, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Mohapatra, G.K.; Bhattacharya, J.; Bandopadhyay, J.; Bera, S.C. Flash photolysis of benzils. J. Photochem. 1987, 40, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Chowdhury, M. Study of the magnetic-field-dependent behaviour of radicals generated photochemically from benzil in micellar media. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 1990, 55, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessenden, R.W.; Carton, P.M.; Shimamori, H.; Scaiano, J.C. Measurement of the dipole moments of excited states and photochemical transients by microwave dielectric absorption. J. Phys. Chem. 1982, 86, 3803–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morantz, D.J.; Wright, A.J.C. Structures of the Excited States of Benzil and Related Dicarbonyl Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.F.V.; Machado, I.F.; Da Silva, J.P.; Oliveira, A.S. A diffuse reflectance comparative study of benzil inclusion within microcrystalline cellulose and β-cyclodextrin. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004, 3, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.F.V.; Machado, I.F.; Oliveira, A.S.; Ferreira, M.R.V.; Da Silva, J.P.; Moreira, J.C. A Diffuse Reflectance Comparative Study of Benzil Inclusion within p-tert-Butylcalix[n]arenes (n ) 4, 6, and 8) and Silicalite. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 12584–12593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Palit, D.K. Excited-state dynamics and photophysics of 2,2′-furil. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 357, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandroff, C.; Chan, I. Triplet emission from furil in different crystalline environments: Optical and odmr studies. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1983, 97, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.C. Biswas, S. Roy, A. Podder. Molecular configuration of α-furil. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1987, 134, 541–544.

- Stern, O.; Volmer, M. About the decay time of fluorescence. Physik. Z. 1919, 20, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Montalti, M.; Credi, A.; Prodi, L.; Gandolfi, M.T. Handbook of Photochemistry, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Okutsu, T.; Ooyama, M.; Tani, K.; Hiratsuka, H.; Kawai, A.; Obi, K. A Kinetic Study on the Spin Polarization Switching of Benzil in the Presence of Triethylamine. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 3741–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, M.; Yamauchi, S.; Hirota, N. Time-resolved EPR study on the photochemical reactions of benzil. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 3305–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turro, N.J.; Engel, R. Quenching of biacetyl fluorescence and phosphorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 7113–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turro, N.J.; Lee, T.J. Polar effects and electrophilic nature of biacetyl singlet and triplet states. Mol. Photochem. 1970, 2, 185–90. [Google Scholar]

- Das, P.K.; Encinas, M.V.; Scaiano, J.C. Laser flash photolysis study of the reactions of carbonyl triplets with phenols and photochemistry of p-hydroxy propiophenone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 4154–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.K.; Encinas, M.V.; Steenken, S.; Scaiano, J.C. Reaction of tert-butoxy radicals with phenols. Comparison with the reactions of carbonyl triplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 4162–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, W.J.; Lathioor, E.C.; Pierre, M.J.S. Photoinduced Hydrogen Abstraction from Phenols by Aromatic Ketones. A New Mechanism for Hydrogen Abstraction by Carbonyl n,π* and π,π* Triplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 12339–12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathioor, E.C.; Leigh, W.J. Bimolecular Hydrogen Abstraction from Phenols by Aromatic Ketone Triplets†. Photochem. Photobiol. 2006, 82, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, M.A.; Lahoz, A.; Martínez-Máñez, R.; Boscá, F.; Castell, J.V.; Pérez-Prieto, J. Enantioselective Discrimination in the Intramolecular Quenching of an Excited Aromatic Ketone by a Ground-State Phenol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 11569–11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.A.; Lahoz, A.; Boscá, F.; Metni, M.R.; Abdelouahab, F.B.; Castell, J.V.; Pérez-Prieto, J. Regio- and stereo-selectivity in the intramolecular quenching of the excited benzoylthiophene chromophore by tryptophan. Chem. Commun. 2000, 2257–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Prieto, J.; Boscá, F.; Galian, R.E.; Lahoz, A.; Domingo, L.R.; Miranda, M.A. Photoreaction between 2-Benzoylthiophene and Phenol or Indole. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 5104–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Bertoti, A.R.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. Phenolic hydrogen abstraction by the triplet excited state of thiochromanone: a laser flash photolysis study. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010, 21, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucas, N.C.; Elias, M.; Firme, C.L.; Correa, R.J.; Garden, S.J.; Nicodem, D.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. A combined laser flash photolysis, density functional theory and atoms in molecules study of the photochemical hydrogen abstraction by pyrene- 4,5-dione. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2009, 201, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lucas, N.C.; Correa, R.J.; Albuquerque, A.C.C.; Firme, C.L.; Bertoti, A.R.; Ferreira, J.C.N. Laser Flash Photolysis and Density Functional Theory Calculation of the Phenolic Hydrogen Abstraction by 1,2-Diketopyracene Triplet State. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.M.; Hrovat, D.A.; Thomas, J.L.; Borden, W.T. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer versus Hydrogen Atom Transfer in Benzyl/Toluene, Methoxyl/Methanol, and Phenoxyl/Phenol Self-Exchange Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 11142–11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammes-Schiffer, S. Theoretical Perspectives on Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reactions. Accounts Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J.M. PROTON-COUPLED ELECTRON TRANSFER: A Reaction Chemist’s View. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2004, 55, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tishchenko, O.; Truhlar, D.G.; Ceulemans, A.; Nguyen, M.T. A Unified Perspective on the Hydrogen Atom Transfer and Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Mechanisms in Terms of Topographic Features of the Ground and Excited Potential Energy Surfaces As Exemplified by the Reaction between Phenol and Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7000–7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lucas, N.C.; Fraga, H.S.; Cardoso, C.P.; Corrêa, R.J.; Garden, S.J.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. A laser flash photolysis and theoretical study of hydrogen abstraction from phenols by triplet α-naphthoflavone. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 10746–10753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Jiang, C.-M.; Chou, P.-T. Recent Experimental Advances on Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Coupled Electron Transfer Reaction. Accounts Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, C.J.; Westlake, B.C.; Kent, C.A.; Paul, J.J.; Papanikolas, J.M.; Meyer, T.J. Integrating proton coupled electron transfer (PCET) and excited states. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2459–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.C.; Tarantino, K.T.; Knowles, R.R. Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Organic Synthesis: Fundamentals, Applications, and Opportunities. Top. Curr. Chem. 2016, 374, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, E.C.; Knowles, R.R. Synthetic Applications of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Accounts Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, J.W.; Koronkiewicz, B.; Parada, G.A.; Mayer, J.M. A Continuum of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reactivity. Accounts Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2391–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozova, O.B.; Panov, M.S.; Fishman, N.N.; Yurkovskaya, A.V. Electron transfer vs. proton-coupled electron transfer as the mechanism of reaction between amino acids and triplet-excited benzophenones revealed by time-resolved CIDNP. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 21127–21135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.I.; Goulart, J.S.; Correa, R.J.; Garden, S.J.; Ferreira, S.B.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C.; Ferreira, V.F.; Miro, P.; Marin, M.L.; Miranda, M.A.; de Lucas, N.C. A photochemical and theoretical study of the triplet reactivity of furano-and pyrano-1,4-naphthoquinones towards tyrosine and tryptophan derivatives. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lucas, N.C.; Corrêa, R.J.; Garden, S.J.; Santos, G.; Rodrigues, R.; Carvalho, C.E.M.; Ferreira, S.B.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C.; Ferreira, V.F.; Miro, P.; Marin, M.L.; Miranda, M.A. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 1201–1209. [CrossRef]

- N.C. de Lucas, C.P. Ruis, R.I. Teixeira, L.L. Marcal, S.J. Garden, R.J. Correa, S.B. Ferreira, J.C. Netto-Ferreira, V.F. Ferreira, J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 2013, 276, 16–30.

- Netto-Ferreira, J.C.; Lhiaubet-Vallet, V.; Bernardes, B.; Ferreira, A.B.B.; Miranda, M.A. Characterization, reactivity, and photosensitizing properties of the triplet excited state of α-lapachone. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6645–6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netto-Ferreira, J.C.; Bernardes, B.; Ferreira, A.B.B.; Miranda, M. Laser flash photolysis study of the triplet reactivity of β-lapachones. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoti, A.R.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. Phenolic Hydrogen Abstraction by the Triplet Excited State of benzophenone-like molecules: 10,10-dimethylanthrone and dibenzosuberone. Trends Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 19, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- J.E.P. Sena-Maia, N.C. de Lucas, A.E.H. Machado, D. Cesarin- Sobrinho, J.C. Netto-Ferreira. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem. 2016, 326, 21-29.

- N.C. de Lucas, C.L.G. Santos, C.S. Gaspar, S.J. Garden, J.C. Netto-Ferreira. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A: Chem 2014, 294, 121–129.

- A.C.S. Serra, N.C. de Lucas, J.C. Netto-Ferreira. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2004, 15, 481-486.

- Rodrigues, J.; Silva, F.; Netto-Ferreira, J. Nanosecond Laser Flash Photolysis Study of the Photochemistry of 2-Alkoxy Thioxanthones. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2024, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.S.; Passos, A.C.; Netto-Ferreira, J.C. Absolute rate constants for the reaction of the thiochroman-4-one 1,1-dioxide triplet with hydrogen and electron donors. Another example of a remarkably reactive carbonyl triplet. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2024, 451, 115491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

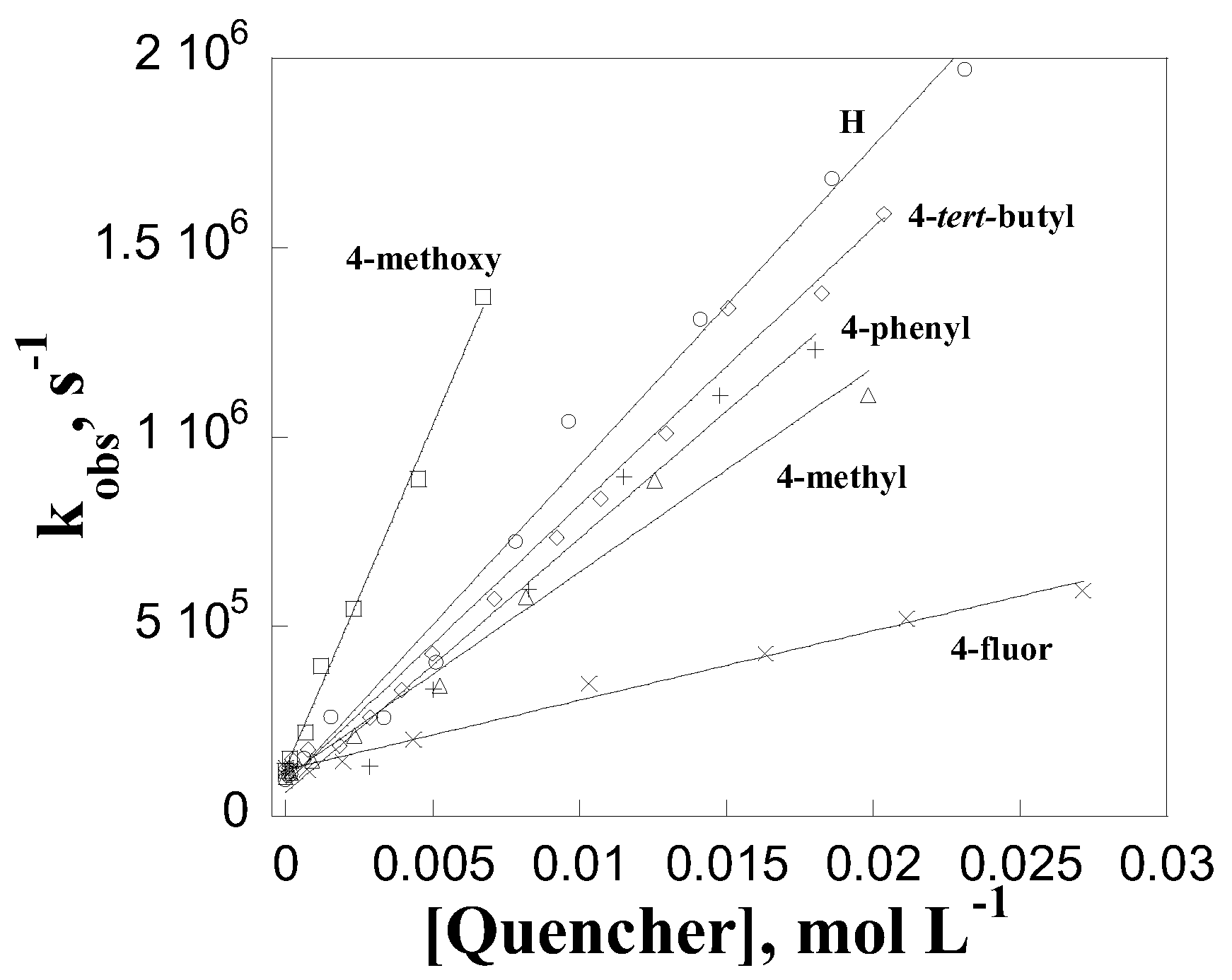

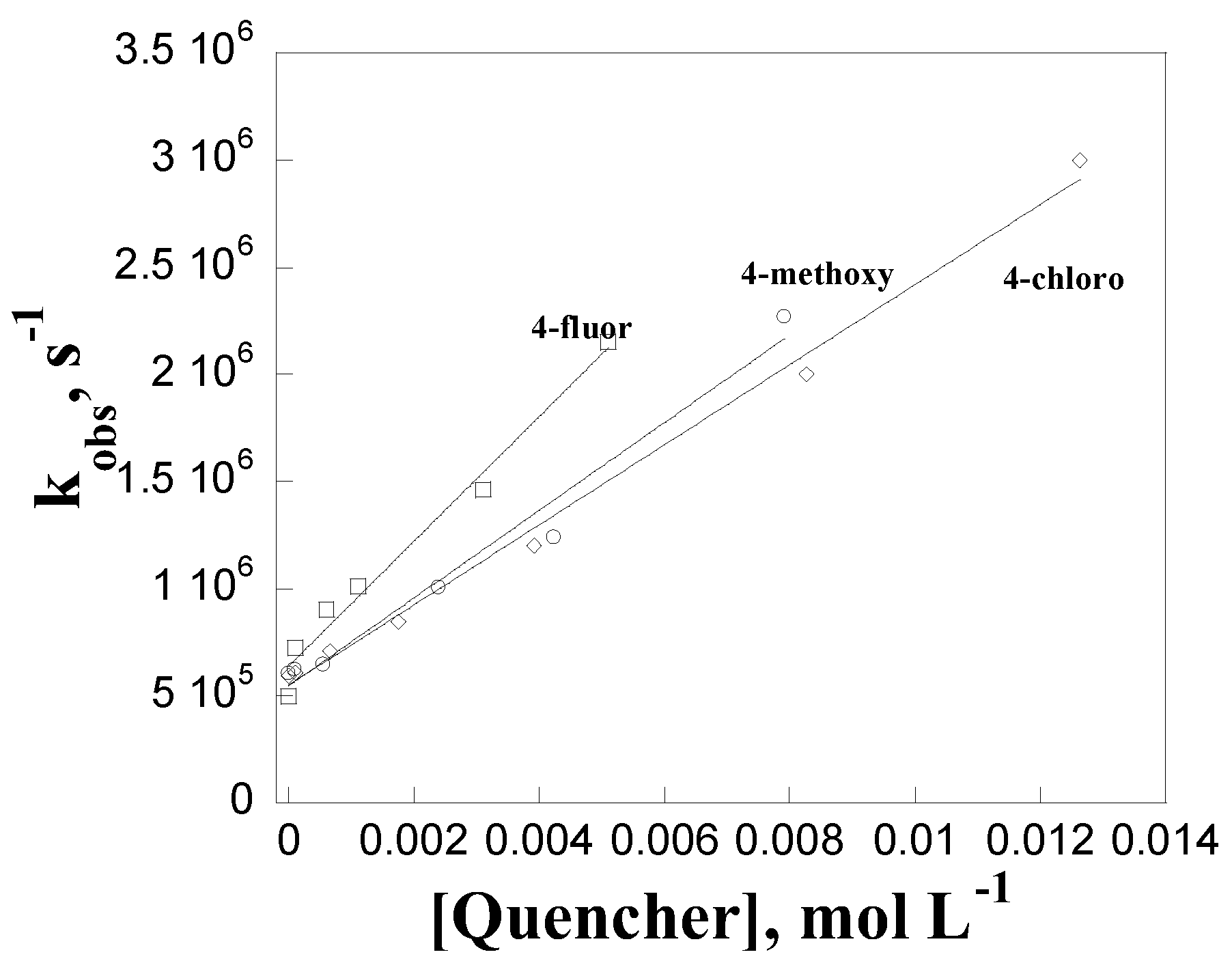

| Quencher | kq, L mol-1 s-1 |

|---|---|

| phenol | (8.4±0.3)x107 |

| para-methoxyphenol | (1.8±0.1)x108 |

| para-terc-butilphenol | (7.3±0.2)x107 |

| para-phenylphenol | (6.7±0.5)x107 |

| para-methylphenol | (5.4±0.3)x107 |

| para-chlorophenol | (1.4±0.1)x107 |

| para-fluorophenol | (1.8±0.1)x107 |

| Quencher | kq, L mol-1 s-1 |

|---|---|

| phenol | (2.2±0.4)x108 |

| para-methoxyphenol | (2.9±0.2)x108 |

| para-methylphenol | (3.5±0.2)x108 |

| para-chlorophenol | (1.9±0.2)x108 |

| para-fluorophenol | (2.1±0.2)x108 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).