Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

17 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

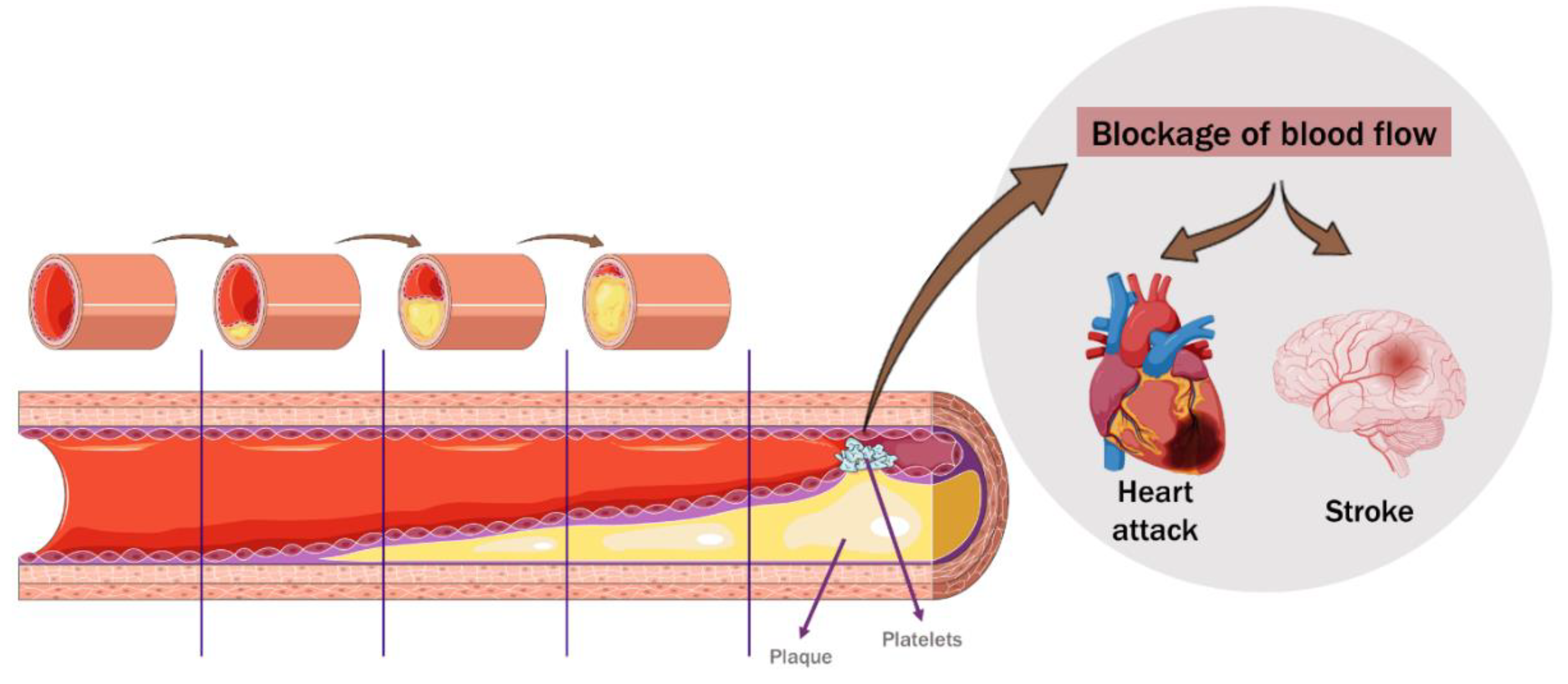

2. Cardiovascular Disease

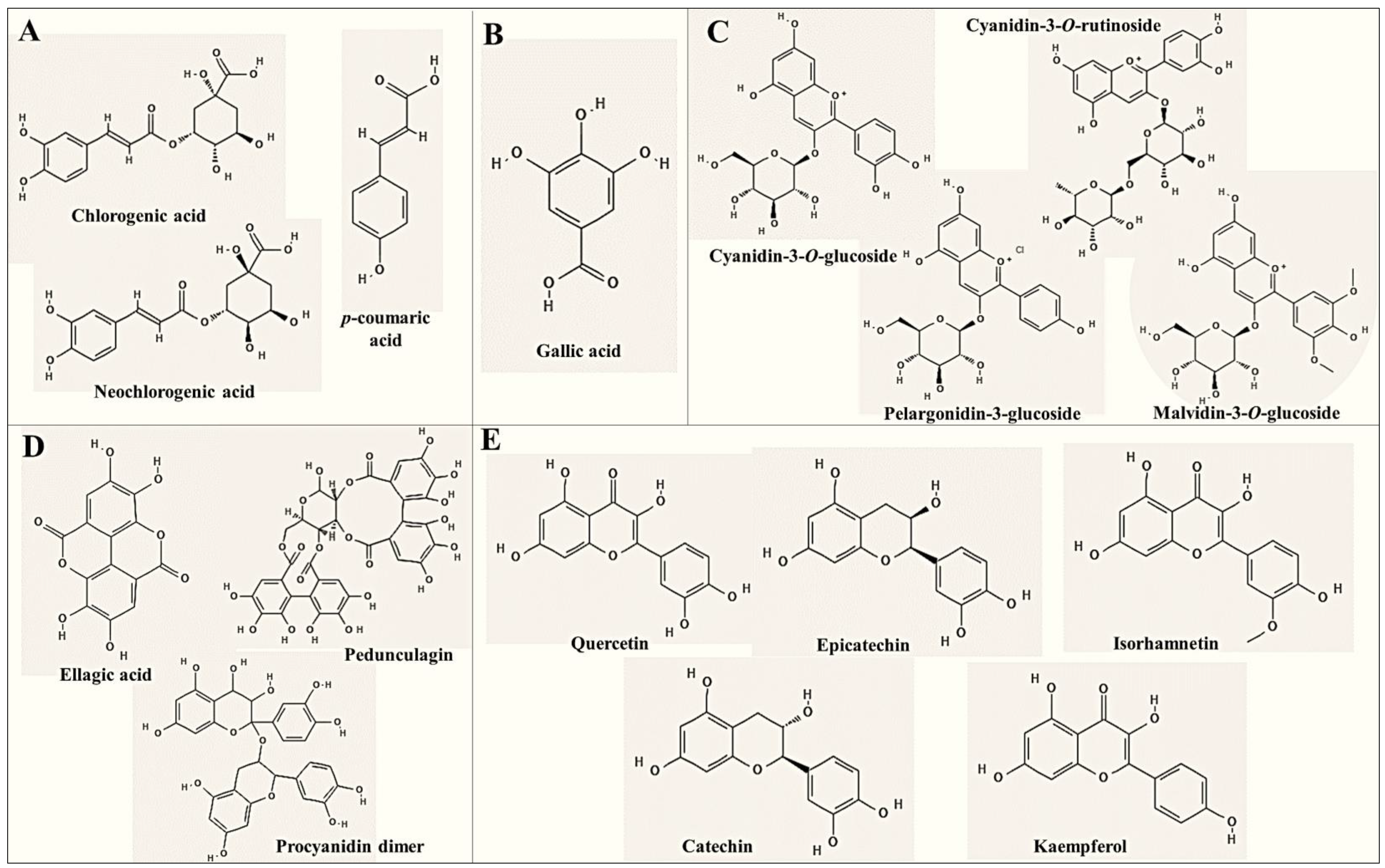

3. Phenolic Composition of Cherries and Berries

| Compound class | Fruit (species) |

Reported compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxycinnamic acids and derivates |

Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus) |

3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3-p-coumaroylquinic acid, 4-p-coumaroylquinic acid, chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid | [45,46] |

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium) | 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3-p-coumaroylquinic acid, 4-p-coumaroylquinic acid, chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid | [45,46,47] | |

|

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) |

3-O-caffeoylquinic acid, 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid dimer, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, ferulic acid-O-hexoside, neochlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, sinapic acid, trans-cinnamic acid | [48,49,50] | |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) |

Caffeic acid, caffeoylhexose, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, feruloylhexose, malonyl-caffeoylquinic acid, malonyl-dicaffeoylquinic acid | [51,52] | |

|

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

Cinnamoyl-glucose, cinnamoyl xylosylglucose, O-p-coumaroylhexose, 1-O-feruloylglucose, 1-O-trans-cinnamoyl-β-glucose, p-coumaric acid, p-coumaric acid derivatives, p-coumaroyl hexose | [53,54,55] | |

|

Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) |

Caffeic acid, caffeic acid-O-glucoside, chlorogenic acid | [56,57,58] | |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids and derivates |

Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus) |

- | |

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium) | Gallic acid | [47] | |

|

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) |

Gallic acid, vanillic acid, protocatechuic acid | [48,49,50] | |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) |

Gallic acid | [51] | |

|

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

- | ||

|

Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) |

Gallic acid, lambertianin C | [57,58] | |

| Anthocyanins and derivatives |

Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus) |

Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-xylosyl-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-sophoroside, cyanidin-3-O-glucosy-lrutinoside, delphinidin-3-O-rutinoside, peonidin-3-O-rutinoside | [45,46,59] |

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium) | Cyanidin-3-O-glycoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, peonidin-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin-3-4′-di-O-glycoside | [45,46,47] | |

|

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) |

Cyanidin-3-O-hexoside, cyanidin-3-O-pentoside, cyanidin-3-O-acetylglucoside, cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-xyloside, delphidin-3-O-glucoside, malvidin-3-O-glucoside | [48] | |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) |

Cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, delphinidin-3-O-arabinoside, delphinidin-3-O-galactoside, delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, malvidin-3-O-arabinoside, malvidin-3-O-galactoside, malvidin-3-O-glucoside, peonidin-3-O-arabinoside, peonidin-3-O-galactoside, peonidin-3-O-glucoside, petunidin-3-O-arabinoside, petunidin-3-O-galactoside, petunidin-3-O-glucoside | [51,52] | |

|

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-hexoside, cyanidin-3-O-pentoside, cyanidin-3-malonylglucoside, pelargonidin-3,5-diglucoside, pelargonidin-3-acetylglucoside, pelargonidin-3-galactoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-rutinoside, pelargonidin hexosides | [53,54,55] | |

|

Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) |

Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, cyanidin-3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside, cyanidin-3-O-sambubioside, cyanidin-3-O-sophoroside, pelargonidin-3-O-glucoside, pelargonidin-3-O-sophoroside | [56,58] | |

| Flavonoids other than anthocyanins |

Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus) |

Catechin, epicatechin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol-3-O-hexoside, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | [45,46] |

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium) | Catechin, epicatechin, isorhamnetin, isorhamnetin-3-O-hexoside, kaempferol-3-O-hexoside, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | [45,46,47] | |

|

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) |

3-Hydroxy-3-MG-quercetin-O-hexoside, catechin, epicatechin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol-3-O-coumaroylglucoside, kaempferol-3-O-galactoside, kaempferol-3-O-hexoside, kaempferol-O-acetylhexoside, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, quercetin-O-acetylhexoside, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, quercetin-O-hexoside, quercetin-O-pentoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | [48,49,50] | |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) |

Catechin, epicatechin, quercetin, quercetin 3-O-rutinoside | [51,52] | |

|

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

Catechin, dihydroflavanone-O-coumaroylhexoside, dihydrokaempferol, isorhamnetin, isorhamnetin-O-acetylhexoside, isorhamnetin-O-deoxyhexoside, kaempferol, kaempferol-3-coumaroylglucoside, kaempferol-3-glucoside, kaempferol-3-glucuronide, kaempferol-3-hexoside, kaempferol-O-acetylhexoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside derivative, quercetin-3-glucuronide, quercetin-3-malonylglucoside, quercetin-O-pentoside, taxifolin-3-O-β-arabinoside | [53,54,55] | |

|

Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) |

Brevifolincarboxylic acid, catechin, catechin derivative, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, kaempferol, kaempferol-3-glucoside, kaempferol-3-glucuronide, quercetin, quercetin-3-glucoside, quercetin-3-glucuronide, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-galactoside, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, tiliroside | [56,57,58] | |

| Tannins and derivatives |

Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus) |

- | |

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium) | - | ||

|

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) |

Casuarinin, ellagic acid, ellagic acid-O-glucuronide, ellagic acid-O-hexoside, ellagic acid-O-pentoside, pedunculagin I, procyanidin dimer | [48,49,50] | |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) |

Ellagic acid, procyanidin dimer | [51,52] | |

|

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

Agrimoniin, davuriicin D2, davuriicin M1, digalloyl-tetraHHDP-diglucose, ellagic acid, ellagic acid deoxyhexoside, ellagic acid pentoside, galloyl-diHHDP-glucose, glucogallin, methyl ellagic acid deoxyhexoside, pedunculagin, potentillin, procyanidin dimer, procyanidin pentamer, procyanidin trimer, tetragalloylglucose | [53,54,55] | |

|

Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) |

Ellagic acid, ellagic acid pentoside, ellagic acid-4-O-acetylxyloside, galloyl-diHHDP-glucose, procyanidin dimer, sanguiin H-2, sanguiin H-6, sanguiin H-6 isomer, sanguiin H-10 isomer | [56,57,58] |

4. The Role of Cherry and Berries Consumption in Cardiovascular Disease

| Fruit (species) |

Type of study | Subjects | Fruit preparation | Procedure | Main results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tart cherry (Prunus cerasus) |

in vivo | Dietary-induced obese rats | Seed powder or seed powder + juice |

Supplementation with seed powder (1 mg/g of fat) or seed powder (1 mg/g of fat) + juice (1 mg AC), daily for 17 weeks daily for 17 weeks | Reduction of systolic blood pressure, oxidative stress, and inflammation | [62] |

| Dietary-induced obese rats | Seed powder or seed powder + juice |

Supplementation with seed powder (1 mg/g of fat) or seed powder (1 mg/g of fat) + juice (1 mg AC), daily for 17 weeks | No effects in accumulation of visceral fat Reduction of inflammatory markers |

[107] | ||

| Clinical trial | Middle-aged adults (48 ± 6 yo) | Concentrate juice | Consumption of 30 mL concentrate in 240 mL water, 2x per day for 3 months | No effects in vascular function or metabolic health | [108] | |

| Older adults (65-80 yo) | Concentrate juice | Consumption of 68 mL concentrate in 412 mL water, daily for 12 weeks | Reduction of systolic blood pressure and LDL-C | [109,110] | ||

| Healthy adults (18-65 yo) | Concentrate juice | Consumption of 30 mL concentrate in 300 mL water, 2x per day for 20 days | No effects in systolic blood pressure and anthropometric, energy expenditure, substrate oxidation, haematological, diastolic blood pressure/resting heart rate, psychological well-being, and sleep efficacy measurements |

[111] | ||

| MetS adults (49 ± 12 yo) | Capsules or concentrate juice | Consumption of 30 mL concentrate in 100 mL water or 10 capsules with 130 mL water, on different occasions | Reduction of systolic blood pressure | [66] | ||

| Early hypertension men (31 ± 9 yo) | Concentrate juice | Consumption of 60 mL concentrate juice, once | Reduction of systolic blood pressure | [68] | ||

| MetS adults (20 – 60 yo) | Juice | Consumption of 240 mL juice, 2x per day for 12 weeks | Reduction of cardiometabolic biomarkers | [112] | ||

| Healthy adults (30-50 yo) | Concentrate juice | Consumption of 30 mL concentrate in 220 mL water, daily for 6 weeks | No effect on arterial stiffness, hsCRP and cardiovascular disease markers Increase in plasma antioxidant capacity |

[113] | ||

| Healthy adults (18-65 yo) | Seed extract | Consumption of 250 mg extract, daily for 14 days | Reduction of circulating neutrophils and ferritin levels Increase in mean cell volume, serum transferrin, mean peroxidase index, and representation of peripheral blood lymphocytes |

[114] | ||

| MetS adults (50 ± 10 yo) | Concentrate juice | Consumption of 30 mL concentrate in 100 mL water | Reduction of systolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure, total cholesterol, LDL-C, total-C:HDL-C ratio and respiratory exchange ratio | [67] | ||

|

Sweet cherry (Prunus avium) |

in vivo | Dietary-induced obese rats | Freeze-dried fruit | Supplementation of 5 or 10% of freeze-dried cherries, daily for 12 weeks | Reduction of body weight, oxidative stress, and inflammation Improvement of liver function and lipid profile |

[89,115] |

| Clinical trial | Obese adults (≥ 18 yo) | Juice supplemented with powder | Consumption of 200 mL of juice, daily for 30 days | Reduction of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and of blood inflammatory biomarkers No effect in lipids |

[71] | |

|

Blackberry (Rubus spp.) |

in vivo | Dietary-induced obese rats | Freeze-dried fruit | High fat and sucrose diet supplemented with 10% blackberry or 10% blackberry + raspberry | Reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress (alteration of redox proteins from the myocardium), when combined with raspberry | [116] |

| Atherosclerosis rat models | Freeze-dried powder | High fat diet supplemented with 2% of powder, ad libitum for 5 weeks | Reduction of plaque accumulation, senescence associated-β-galactosidase and Nox1 expression in the aorta of male rats No effects in lipid profile |

[117] | ||

| Ovariectomized rats | Freeze-dried powder | Diet supplemented with 5 or 10% of powder, daily for 100 days | Reduction of ovariectomy-induced weight gain and downregulation of inflammation related genes Improvement of lipid profile |

[118] | ||

| Rats exposed to e-cigarette vapor | Freeze-dried powder | Diet supplemented with 5% of powder, daily for 16 weeks | Mitigated the increase of oxidative stress markers Reduced endothelial dysfunction No effects in serum antioxidant capacity |

[86] | ||

| Dietary-induced obese rats | Freeze-dried powder | High fat and sucrose diet supplemented with 10% blackberry or 10% blackberry + raspberry, daily for 20 weeks | Reduction of aortic oxidative stress and oxidative burden to the endothelium | [119] | ||

| Clinical trial | Healthy adults | Juice | High fat and high carbohydrate diet supplemented with 250 mL of juice, 3x per day for 14 days | Reduction of plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol, and glucose levels No effect in LDL-C and HDL-C |

[120] | |

|

Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) |

in vivo | Particulate matter-exposed rats | Blueberry anthocyanin-enriched extract | Administration of 0.5, 1 or 2 g/kg of extract, daily for 5 weeks | Improvement of abnormal ECG Reduction of cardiac injury biomarkers |

[121] |

| Clinical trial | Healthy adults (18-60 yo) | Fresh fruit or freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 160 g of fresh fruit or 20 g of powder, daily for 1 week | No effect in blood pressure, endothelial function, plasma lipids, and nitrite levels Increase of plasma NO2− levels |

[122] | |

| metS adults (50 ± 3 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 50 g powder in 480 mL water with vanilla extract or “Splenda”, daily for 8 weeks | Reduction of systolic diastolic blood pressure, oxidized LDL-C and MDA No effects in lipid profiles |

[72] | ||

| metS adults (50 - 75 yo) | Fresh fruit | Consumption of 75 or 150 g of blueberries, daily for 6 months | Improved endothelial function, systemic arterial stiffness and reduced cyclic guanosine monophosphate concentrations No effects in pulse wave velocity, blood pressure, NO, and plasma thiol status |

[123] | ||

| metS adults (> 20 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 22.5 g of powder mixed into 29.6 mL yogurt and skim milk-based smoothie, 2x per day for 6 weeks | No effects in blood pressure Improvement of resting endothelial function |

[124] | ||

| metS adults (63.4 ± 7.4) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 26 g of powder with a 500 g energy-dense milkshake, once | Reduced cholesterol Increased HDL-C, fractions of HDL and Apo-AI |

[125] | ||

| Sedentary adults (40 – 70 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 38 g of powder, daily for 7 days; consumption once, again, after 3 weeks | Reduced systolic blood pressure No effect in diastolic blood pressure |

[73] | ||

| Adults with metS risk (22 – 53 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 25 g of powder in 300 mL water, 2x per day for 8 weeks | No effect in markers of cardiometabolic health Changed expression of 49 genes and abundance of 35 metabolites of immune related pathways |

[126] | ||

| Pre and stage 1-hypertensive Postmenopausal women (45 – 65 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 11 g of powder in 240 mL, 2x per day for 8 weeks | Decreased one marker of oxidative DNA damage after 4 but not 8 weeks No effect in inflammation, and antioxidant defence biomarkers |

[127] | ||

| Hypertension postmenopausal women (45 – 65 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 11 g of powder in water, 2x per day for 12 weeks | Improved endothelial function No effects in blood pressure, arterial stiffness, blood biomarkers and endothelial cell protein expression |

[87] | ||

| metS adults ( ≥ 20 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 22.5 g of powder mixed into 356 mL yogurt and skim-milk based smoothie, 2x per day for 6 weeks | Reduction of oxidative stress and expression of inflammatory markers in monocytes | [88] | ||

| Healthy women (30 – 50 yo) | Blueberry and raspberry pomace cookies | Consumption of 4 cookies (32 g), daily for 4 weeks | Reduction of LDL-C, ALT and AST Increase in adiponectin levels |

[96] | ||

|

Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) |

in vivo | Dietary-induced obese rats | Freeze-dried fruit | High fat and sucrose diet supplemented with 10% raspberry or 10% blackberry + raspberry | Reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress (alteration of redox proteins from the myocardium), when combined with blackberry | [116] |

| Obese diabetic rats | Freeze-dried powder | Administration of 0.8 g of powder, daily for 8 weeks | Reduction of expression of proteins related to cardiac remodelling and oxidative and inflammatory stress No effects in heart lipid composition, adipokines, and morphology |

[128] | ||

| Spontaneously hypertensive rats | Ethyl acetate extract | Administration of 100 or 200 mg/kg of extract, daily for 5 weeks | Reduction of blood pressure (increased with dose), MDA (high dose), plasma endothelin (high dose) Increase in nitric oxide (low dose) and superoxide dismutase levels |

[78] | ||

| metS rat models | Freeze-dried powder | Supplementation of the equivalent to 1 and ½ cup of fresh fruit in humans, daily for 8 weeks | Improvement of aorta vasoconstriction and vasorelaxation | [129] | ||

| Clinical trial | Overweight pre-diabetic adults (20 – 60 yo) | Frozen fruit | Consumption of 125 or 250 g of fruit with a high carbohydrate breakfast in 3 separate days | No effects in oxidative stress and inflammatory biomarkers | [130] | |

| Healthy women (30 – 50 yo) | Blueberry and raspberry pomace cookies | Consumption of 4 cookies (32 g), daily for 4 weeks | Reduction of LDL-C, ALT and AST Increase in adiponectin levels |

[96] | ||

|

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) |

Clinical trial | metS adults (47 +-3 yo) | Freeze-dried fruit beverage | Consumption of 50 g of powder with 4 cups of water, daily for 8 weeks | Reduction of total and LDL-C and circulating adhesion molecules | [131] |

| Healthy adults (27 +- 3.2 yo) | Fresh fruit | Consumption of 500 g of fruit, daily for 1 month | Reduction of total cholesterol, LDL-C and triglycerides levels and oxidative stress markers No effects in HDL-C |

[95] | ||

| Obese adults (20 – 50 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 80 g of powder mixed in a milkshake, yogurt, cream cheese or water-based sweetened beverage, 2x per day for 3 weeks | Reduction of plasma cholesterol, small HDL particles, Increased LDL particle size |

[132] | ||

| Overweight or obese adults (28 +- 2 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | High fat meal with 40 g of powder, once | No effects in vascular function and postprandial triglycerides | [133] | ||

| Healthy male adolescents (14 – 18 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 25 g of powder with water, 2x per day for 1 week | Increase of reactive hyperaemia index | [134] | ||

| Hyperlipidaemic adults (50.9 +- 15 yo) | Freeze-dried fruit beverage | Consumption of a 10 g freeze-dried fruit beverage, daily for 6 weeks + 3 moments of consumption of a high fat diet | Reduction of postprandial triglycerides and oxidized LDL | [102] | ||

| Obese adults 53 ± 13 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 32 g or 13 g of powder with water, daily for 4 weeks | Reduction of LDL, VLDL and LDL particles, serum PAI-1 (high dose) No effect in lipid profile |

[135] | ||

| Overweight adults (50.9 ± 15 yo) | Freeze-dried fruit beverage | Consumption of 10 g freeze-dried fruit beverage, daily for 6 weeks | Reduction of postprandial PAI-1, IL-1β No effects in platelet aggregation, hsCRP, TNF-α |

[136] | ||

| Moderate hypercholesteremia (53 ± 1 yo) | Freeze-dried fruit beverage | Consumption of 25 g freeze-dried fruit beverage, 2x per day for 4 weeks | Reduction of systolic blood pressure No effects in LDL, total cholesterol, triglycerides, hsCRP |

[74] | ||

| Healthy adults (20 – 60 yo) | Fruit pulp | Consumption of 500 g of pulp, daily for 30 days, followed by a washout period and new consumption period | Reduction of paraoxonase PON-1 activity No effects in the lipid profile |

[137] | ||

| Obese adults (49 ± 10 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 25 g or 50 g of powder in 474 mL of water, daily for 12 weeks | Increased plasma antioxidant biomarkers | [138] | ||

| Overweight or obese adults (50 ± 1.0 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 13 g or 40 g of powder in water, daily for 4 weeks | Reduction of total cholesterol (with low dose) No effects in vascular function, inflammation, or HDL efflux |

[139] | ||

| Overweight or obese adult males (31.5 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 25 g of powder in a high carbohydrate meal, 16 hours after 40 minutes of intense physical exercise | Reduction of postprandial lipaemia No effects in postprandial triglycerides and lipid related oxidative stress markers |

[140] | ||

| Diabetic women (51.57 ± 10 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 25 g of powder in water, 2x per day for 6 weeks | Improvement of glycaemic control and antioxidant status Reduction of lipid peroxidation and inflammatory response No effects in serum glucose and anthropometric indices |

[141] | ||

| Adults with abdominal adiposity and high serum lipids (49 ± 10 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 25 g or 50 g of powder in 474 mL of water, daily for 12 weeks | Reduction of total and LDL-C, LDL particles, lipid peroxidation No effects in adiposity, blood pressure, glycaemic control, or inflammation |

[60,142] | ||

| Pre and stage 1-hypertensive postmenopausal women (45 – 65 yo) | Freeze-dried powder | Consumption of 12.5 or 25 g of powder in 240 mL, 2x per day for 8 weeks | No effects in blood pressure or vascular function | [60] |

5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, T.C. Anthocyanins in Cardiovascular Disease. Advances in Nutrition 2011, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterle, T. Nebenwirkungen Und Interaktionen Häufig Eingesetzter Kardiologischer Medikamente. Therapeutische Umschau 2015, 72, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Dhewa, T.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Potential Health Benefits of Plant Food-Derived Bioactive Components: An Overview. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellendick, K.; Shanahan, L.; Wideman, L.; Calkins, S.; Keane, S.; Lovelady, C. Diets Rich in Fruits and Vegetables Are Associated with Lower Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Adolescents. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; Nowson, C.A.; Lucas, M.; MacGregor, G.A. Increased Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables Is Related to a Reduced Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. J Hum Hypertens 2007, 21, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolini, D.G.; Maciel, G.M.; Fernandes, I. de A.A.; Rossetto, R.; Brugnari, T.; Ribeiro, V.R.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Biological Potential and Technological Applications of Red Fruits: An Overview. Food Chemistry Advances 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA) Tabela de Composição de Alimentos 2023.

- Cosme, F.; Pinto, T.; Aires, A.; Morais, M.C.; Bacelar, E.; Anjos, R.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Gonçalves, B. Red Fruits Composition and Their Health Benefits—A Review. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Colletti, A.; Bajraktari, G.; Descamps, O.; Djuric, D.M.; Ezhov, M.; Fras, Z.; Katsiki, N.; Langlois, M.; Latkovskis, G.; et al. Lipid-Lowering Nutraceuticals in Clinical Practice: Position Paper from an International Lipid Expert Panel. Nutr Rev 2017, 75, 731–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkegren, J.L.M.; Lusis, A.J. Atherosclerosis: Recent Developments. Cell 2022, 185, 1630–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Hospital Discharges by Diagnosis, in-Patients, per 100 000 Inhabitants; 2023.

- European Comission Cardiovascular Diseases Prevention. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/cardiovascular-diseases-prevention_en#definitionofcardiovasculardiseases (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Dunbar, S.B.; Khavjou, O.A.; Bakas, T.; Hunt, G.; Kirch, R.A.; Leib, A.R.; Morrison, R.S.; Poehler, D.C.; Roger, V.L.; Whitsel, L.P. Projected Costs of Informal Caregiving for Cardiovascular Disease: 2015 to 2035: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, e558–e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Global Economic Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases; 2011.

- Mendoza, W.; Miranda, J.J. Global Shifts in Cardiovascular Disease, the Epidemiologic Transition, and Other Contributing Factors: Toward a New Practice of Global Health Cardiology. Cardiol Clin 2017, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheus, A.S.D.M.; Tannus, L.R.M.; Cobas, R.A.; Palma, C.C.S.; Negrato, C.A.; Gomes, M.D.B. Impact of Diabetes on Cardiovascular Disease: An Update. Int J Hypertens 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.A.; Antman, E.M. Ideal Cardiovascular Health in Young Adults With Established Cardiovascular Diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, H.; Shivgotra, V.K.; Kumar, M. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Diseases among the Urban and Rural Geriatric Population of India. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2022, 7721–7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokgozoglu, L.; Kayikcioglu, M.; Ekinci, B. The Landscape of Preventive Cardiology in Turkey: Challenges and Successes. Am J Prev Cardiol 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, A.; Rossi, R.; Modena, M.G. Hypertension Alone or Related to the Metabolic Syndrome in Postmenopausal Women. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2010, 8, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.A.; Prior, J.A.; Kadam, U.T.; Jordan, K.P. Chest Pain and Shortness of Breath in Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study in UK Primary Care. BMJ Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, S.; Cho, L.S. Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Prevention, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Pathogenesis. Cleve Clin J Med 2013, 80, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whooley, M.A.; De Jonge, P.; Vittinghoff, E.; Otte, C.; Moos, R.; Carney, R.M.; Ali, S.; Dowray, S.; Na, B.; Feldman, M.D.; et al. Depressive Symptoms, Health Behaviors, and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA 2008, 300, 2379–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, M.D.; Bhatnagar, D. Novel Treatments for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Cardiovasc Ther 2012, 30, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, B.R.; Heleno, S.A. 8.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic Compounds: Current Industrial Applications, Limitations and Future Challenges. Food Funct 2021, 12, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Human Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovaskainen, M.-L.; Törrönen, R.; Koponen, J.M.; Sinkko, H.; Hellström, J.; Reinivuo, H.; Mattila, P. Dietary Intake and Major Food Sources of Polyphenols in Finnish Adults. J Nutr 2008, 138, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habauzit, V.; Morand, C. Evidence for a Protective Effect of Polyphenols-Containing Foods on Cardiovascular Health: An Update for Clinicians. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2012, 3, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and Anthocyanins: Colored Pigments as Food, Pharmaceutical Ingredients, and the Potential Health Benefits. Food Nutr Res 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laleh, G.H.; Frydoonfar, H.; R. Heidary, R.; R. Jameei, R.; S. Zare, S. The Effect of Light, Temperature, PH and Species on Stability of Anthocyanin Pigments in Four Berberis Species. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 2005, 5, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Ávila, J.; López-Angulo, G.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Tannins in Fruits and Vegetables: Chemistry and Biological Functions. In Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals; Wiley, 2017; pp. 221–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tajner-Czopek, A.; Gertchen, M.; Rytel, E.; Kita, A.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A. Study of Antioxidant Activity of Some Medicinal Plants Having High Content of Caffeic Acid Derivatives. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mard, S.A.; Mojadami, S.; Farbood, Y.; Kazem, M.; Naseri, G.; Ali, S.; Phd, M. The Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Gallic Acid against Mucosal Inflammation-and Erosions-Induced by Gastric Ischemia-Reperfusion in Rats; 2015; Vol. 6;

- Gandhi, G.R.; Jothi, G.; Antony, P.J.; Balakrishna, K.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Stalin, A.; Al-Dhabi, N.A. Gallic Acid Attenuates High-Fat Diet Fed-Streptozotocin-Induced Insulin Resistance via Partial Agonism of PPARγ in Experimental Type 2 Diabetic Rats and Enhances Glucose Uptake through Translocation and Activation of GLUT4 in PI3K/p-Akt Signaling Pathway. Eur J Pharmacol 2014, 745, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.T.; Farbood, Y.; Sameri, M.J.; Sarkaki, A.; Naghizadeh, B.; Rafeirad, M. Neuroprotective Effects of Oral Gallic Acid against Oxidative Stress Induced by 6-Hydroxydopamine in Rats. Food Chem 2013, 138, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priscilla, D.H.; Prince, P.S.M. Cardioprotective Effect of Gallic Acid on Cardiac Troponin-T, Cardiac Marker Enzymes, Lipid Peroxidation Products and Antioxidants in Experimentally Induced Myocardial Infarction in Wistar Rats. Chem Biol Interact 2009, 179, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivas-Aguirre, F.J.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Martínez-Ruiz, N.D.R.; Cárdenas-Robles, A.I.; Mendoza-Díaz, S.O.; Álvarez-Parrilla, E.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; De La Rosa, L.A.; Ramos-Jiménez, A.; Wall-Medrano, A. Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside: Physical-Chemistry, Foodomics and Health Effects. Molecules 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassellund, S.S.; Flaa, A.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Seljeflot, I.; Karlsen, A.; Erlund, I.; Rostrup, M. Effects of Anthocyanins on Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Inflammation in Pre-Hypertensive Men: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study. J Hum Hypertens 2013, 27, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knobloch, T.J.; Uhrig, L.K.; Pearl, D.K.; Casto, B.C.; Warner, B.M.; Clinton, S.K.; Sardo-Molmenti, C.L.; Ferguson, J.M.; Daly, B.T.; Riedl, K.; et al. Suppression of Proinflammatory and Prosurvival Biomarkers in Oral Cancer Patients Consuming a Black Raspberry Phytochemical-Rich Troche. Cancer Prevention Research 2016, 9, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rein, M.J.; Heinonen, M. Stability and Enhancement of Berry Juice Color. J Agric Food Chem 2004, 52, 3106–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkmen, N.; Sarı, F.; Velioglu, Y.S. Factors Affecting Polyphenol Content and Composition of Fresh and Processed Tea Leaves. Akademik Gıda 2009, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Picariello, G.; Ferranti, P.; De Cunzo, F.; Sacco, E.; Volpe, M.G. Polyphenol Patterns to Trace Sweet (Prunus Avium) and Tart (Prunus Cerasus) Varieties in Cherry Jam. J Food Sci Technol 2017, 54, 2316–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picariello, G.; De Vito, V.; Ferranti, P.; Paolucci, M.; Volpe, M.G. Species- and Cultivar-Dependent Traits of Prunus Avium and Prunus Cerasus Polyphenols. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2016, 45, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Ramos, R.; Rosado, T.; Gallardo, E.; Duarte, A.P. Development and Validation of a HPLC–DAD Method for Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Different Sweet Cherry Cultivars. SN Appl Sci 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spínola, V.; Pinto, J.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Tomás, H.; Castilho, P.C. Evaluation of Rubus Grandifolius L. (Wild Blackberries) Activities Targeting Management of Type-2 Diabetes and Obesity Using in Vitro Models. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2019, 123, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoenescu, A.-M.; Trandafir, I.; Cosmulescu, S. Determination of Phenolic Compounds Using HPLC-UV Method in Wild Fruit Species. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Greenspan, P.; Srivastava, A.; Pegg, R.B. Characterizing the Phenolic Constituents of U.S. Southeastern Blackberry Cultivars. J Berry Res 2020, 10, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Može, Š.; Polak, T.; Gašperlin, L.; Koron, D.; Vanzo, A.; Poklar Ulrih, N.; Abram, V. Phenolics in Slovenian Bilberries (Vaccinium Myrtillus L.) and Blueberries (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.). J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 6998–7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilova, V.; Kajdžanoska, M.; Gjamovski, V.; Stefova, M. Separation, Characterization and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Blueberries and Red and Black Currants by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 4009–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lara, R.; Gordillo, B.; Rodríguez-Pulido, F.J.; Lourdes González-Miret, M.; del Villar-Martínez, A.A.; Dávila-Ortiz, G.; Heredia, F.J. Assessment of the Differences in the Phenolic Composition and Color Characteristics of New Strawberry (Fragaria x Ananassa Duch.) Cultivars by HPLC-MS and Imaging Tristimulus Colorimetry. Food Research International 2015, 76, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaby, K.; Mazur, S.; Nes, A.; Skrede, G. Phenolic Compounds in Strawberry (Fragaria x Ananassa Duch.) Fruits: Composition in 27 Cultivars and Changes during Ripening. Food Chem 2012, 132, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka, A.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Fecka, I. Comparison of Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Strawberry Fruit from 90 Cultivars of Fragaria × ananassa Duch. Food Chem 2019, 270, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Cui, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, J.; Hao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties in Three Raspberries (Rubus Idaeus) at Five Ripening Stages in Northern China. Sci Hortic 2020, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, M.; Majdan, M.; Głód, D.; Krauze-Baranowska, M. Phenolic Composition of Fruits from Different Cultivars of Red and Black Raspberries Grown in Poland. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2016, 52, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Degeneve, A.; Mullen, W.; Crozier, A. Identification of Flavonoid and Phenolic Antioxidants in Black Currants, Blueberries, Raspberries, Red Currants, and Cranberries. J Agric Food Chem 2010, 58, 3901–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukhmana, N.; Kong, F.; Singh, R.K. Micronization Enhanced Extractability of Polyphenols and Anthocyanins in Tart Cherry Puree. Food Biosci 2022, 50, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feresin, R.G.; Johnson, S.A.; Pourafshar, S.; Campbell, J.C.; Jaime, S.J.; Navaei, N.; Elam, M.L.; Akhavan, N.S.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Tenenbaum, G.; et al. Impact of Daily Strawberry Consumption on Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Pre- and Stage 1-Hypertensive Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. In Proceedings of the Food and Function; Royal Society of Chemistry, November 1 2017; Vol. 8, pp. 4139–4149. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R.; Peto, R.; MacMahon, S.; Godwin, J.; Qizilbash, N.; Collins, R.; MacMahon, S.; Hebert, P.; Eberlein, K.A.; Taylor, J.O.; et al. Blood Pressure, Stroke, and Coronary Heart Disease. The Lancet 1990, 335, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, I.; Tomassoni, D.; Bellitto, V.; Roy, P.; Micioni Di Bonaventura, M.V.; Amenta, F.; Amantini, C.; Cifani, C.; Tayebati, S.K. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Tart Cherry Consumption in the Heart of Obese Rats. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, I.; Tomassoni, D.; Moruzzi, M.; Roy, P.; Cifani, C.; Amenta, F.; Tayebati, S.K. Cardiovascular Changes Related to Metabolic Syndrome: Evidence in Obese Zucker Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaddam-Daher, S.; Menaouar, A.; El-ayoubi, R.; Gutkowska, J.; Jankowski, M.; Velliquette, R.; Ernsberger, P. Cardiac Effects of Moxonidine in Spontaneously Hypertensive Obese Rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003, 1009, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, M.; Renaud, I.M.; Poirier, B.; Michel, O.; Belair, M.-F.; Mandet, C.; Bruneval, P.; Myara, I.; Chevalier, J. High Levels of Myocardial Antioxidant Defense in Aging Nondiabetic Normotensive Zucker Obese Rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2004, 286, R793–R800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, T.; Roberts, M.; Bottoms, L. Effects of Montmorency Tart Cherry Supplementation on Cardio-Metabolic Markers in Metabolic Syndrome Participants: A Pilot Study. J Funct Foods 2019, 57, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, T.; Roberts, M.; Bottoms, L. Effects of Short-Term Continuous Montmorency Tart Cherry Juice Supplementation in Participants with Metabolic Syndrome. Eur J Nutr 2021, 60, 1587–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, K.M.; George, T.W.; Constantinou, C.L.; Brown, M.A.; Clifford, T.; Howatson, G. Effects of Montmorency Tart Cherry (Prunus Cerasus L.) Consumption on Vascular Function in Men with Early Hypertension. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016, 103, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obón, J.M.; Díaz-García, M.C.; Castellar, M.R. Red Fruit Juice Quality and Authenticity Control by HPLC. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2011, 24, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, K.M.; Bell, P.G.; Lodge, J.K.; Constantinou, C.L.; Jenkinson, S.E.; Bass, R.; Howatson, G. Phytochemical Uptake Following Human Consumption of Montmorency Tart Cherry (L. Prunus Cerasus) and Influence of Phenolic Acids on Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Vitro. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbizu, S.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U.; Talcott, S.; Noratto, G.D. Dark Sweet Cherry (Prunus Avium) Supplementation Reduced Blood Pressure and Pro-Inflammatory Interferon Gamma (IFNγ) in Obese Adults without Affecting Lipid Profile, Glucose Levels and Liver Enzymes. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Du, M.; Leyva, M.J.; Sanchez, K.; Betts, N.M.; Wu, M.; Aston, C.E.; Lyons, T.J. Blueberries Decrease Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Obese Men and Women with Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of Nutrition 2010, 140, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAnulty, L.S.; Collier, S.R.; Pike, J.; Thompson, K.L.; McAnulty, S.R. Time Course of Blueberry Ingestion on Measures of Arterial Stiffness and Blood Pressure. J Berry Res 2019, 9, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, X.; Sandhu, A.K.; Chandra, P.; Kay, C.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B. Strawberry Consumption, Cardiometabolic Risk Factors, and Vascular Function: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Moderate Hypercholesterolemia. J Nutr 2021, 151, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüscher, T.F.; Vanhoutte, P.M. The Endothelium: Modulator of Cardiovascular Function; CRC Press, 2020; ISBN 9780429281808. [Google Scholar]

- Daiber, A.; Steven, S.; Weber, A.; Shuvaev, V.V.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Laher, I.; Li, H.; Lamas, S.; Münzel, T. Targeting Vascular (Endothelial) Dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol 2017, 174, 1591–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozos, I.; Luca, C.T. Crosstalk between Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress and Arterial Stiffness. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Liu, J.W.; Ufur, H.; He, G.S.; Liqian, H.; Chen, P. The Antihypertensive Effect of Ethyl Acetate Extract from Red Raspberry Fruit in Hypertensive Rats. Pharmacogn Mag 2011, 7, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzè, M.C.; Pizzala, R.; Perucca, P.; Cazzalini, O.; Savio, M.; Forti, L.; Vannini, V.; Bianchi, L. Anthocyanidins Decrease Endothelin-1 Production and Increase Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase in Human Endothelial Cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2006, 50, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, E.; Devarajan, P.; Kaskel, F. Role of Nitric Oxide, Endothelin-1, and Inflammatory Cytokines in Blood Pressure Regulation in Hemodialysis Patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2002, 40, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.W.; Ikeda, K.; Yamori, Y. Upregulation of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase by Cyanidin-3-Glucoside, a Typical Anthocyanin Pigment. Hypertension 2004, 44, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Xu, X.H.; Chen, T.B.; Li, L.; Rao, P.F. An Assay for Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Using Capillary Zone Electrophoresis. Anal Biochem 2000, 280, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imig, J.D. ACE Inhibition and Bradykinin-Mediated Renal Vascular Responses. Hypertension 2004, 43, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Kim, H.J.; Heo, H.; Kim, M.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, J. Comparison of the Antihypertensive Activity of Phenolic Acids. Molecules 2022, 27, 6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shukor, N.; Van Camp, J.; Gonzales, G.B.; Staljanssens, D.; Struijs, K.; Zotti, M.J.; Raes, K.; Smagghe, G. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Effects by Plant Phenolic Compounds: A Study of Structure Activity Relationships. In Proceedings of the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, December 4 2013; Vol. 61, pp. 11832–11839. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, M.L.; Feresin, R.G. Blackberry Consumption Protects against E-Cigarette-Induced Vascular Oxidative Stress in Mice. Food Funct 2023, 14, 10709–10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, E.K.; Terwoord, J.D.; Litwin, N.S.; Vazquez, A.R.; Lee, S.Y.; Ghanem, N.; Michell, K.A.; Smith, B.T.; Grabos, L.E.; Ketelhut, N.B.; et al. Daily Blueberry Consumption for 12 Weeks Improves Endothelial Function in Postmenopausal Women with Above-Normal Blood Pressure through Reductions in Oxidative Stress: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Food Funct 2023, 14, 2621–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.R.; Mariappan, N.; Stull, A.J.; Francis, J. Blueberry Supplementation Attenuates Oxidative Stress within Monocytes and Modulates Immune Cell Levels in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Food Funct 2017, 8, 4118–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziadek, K.; Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E. Intake of Fruit and Leaves of Sweet Cherry Beneficially Affects Lipid Metabolism, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Wistar Rats Fed with High Fat-Cholesterol Diet. J Funct Foods 2019, 57, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Huerta, O.D.; Pastor-Villaescusa, B.; Aguilera, C.M.; Gil, A. A Systematic Review of the Efficacy of Bioactive Compounds in Cardiovascular Disease: Phenolic Compounds. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5177–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofei, F. Obesity - A Preventable Disease. 2005, 39, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, S.; Fujita, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Iwaki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Nakayama, O.; Makishima, M.; Matsuda, M.; Shimomura, I. Increased Oxidative Stress in Obesity and Its Impact on Metabolic Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2004, 114, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todoric, J.; Löffler, M.; Huber, J.; Bilban, M.; Reimers, M.; Kadl, A.; Zeyda, M.; Waldhäusl, W.; Stulnig, T.M. Adipose Tissue Inflammation Induced by High-Fat Diet in Obese Diabetic Mice Is Prevented by n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2109–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeramani, C.; Alsaif, M.A.; Al-Numair, K.S. Lavatera Critica, a Green Leafy Vegetable, Controls High Fat Diet Induced Hepatic Lipid Accumulation and Oxidative Stress through the Regulation of Lipogenesis and Lipolysis Genes. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2017, 96, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Giampieri, F.; Tulipani, S.; Casoli, T.; Di Stefano, G.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Busco, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Cordero, M.D.; et al. One-Month Strawberry-Rich Anthocyanin Supplementation Ameliorates Cardiovascular Risk, Oxidative Stress Markers and Platelet Activation in Humans. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2014, 25, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popović, T.; Šarić, B.; Martačić, J.D.; Arsić, A.; Jovanov, P.; Stokić, E.; Mišan, A.; Mandić, A. Potential Health Benefits of Blueberry and Raspberry Pomace as Functional Food Ingredients: Dietetic Intervention Study on Healthy Women Volunteers. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Xia, M.; Ma, J.; Hao, Y.; Liu, J.; Mou, H.; Cao, L.; Ling, W. Anthocyanin Supplementation Improves Serum LDL- and HDL-Cholesterol Concentrations Associated with the Inhibition of Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein in Dyslipidemic Subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 90, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, J.A.; Rodwell, V.W. The 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl Coenzyme-A (HMG-CoA) Reductases. Genome Biol 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barter, P.J.; Rye, K.A. Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Inhibition as a Strategy to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. J Lipid Res 2012, 53, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, T.; Melzig, M.F. Polyphenolic Compounds as Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitors. Planta Med 2015, 81, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Nicoletti, M.; Menichini, F.; Conforti, F. In Vitro Investigation of the Potential Health Benefits of Wild Mediterranean Dietary Plants as Anti-Obesity Agents with α-Amylase and Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitory Activities. J Sci Food Agric 2014, 94, 2217–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton-Freeman, B.; Linares, A.; Hyson, D.; Kappagoda, T. Strawberry Modulates Ldl Oxidation and Postprandial Lipemia in Response to High-Fat Meal in Overweight Hyperlipidemic Men and Women. J Am Coll Nutr 2010, 29, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forni, C.; Facchiano, F.; Bartoli, M.; Pieretti, S.; Facchiano, A.; D’Arcangelo, D.; Norelli, S.; Valle, G.; Nisini, R.; Beninati, S.; et al. Beneficial Role of Phytochemicals on Oxidative Stress and Age-Related Diseases. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, S.B.; Laffitte, B.A.; Patel, P.H.; Watson, M.A.; Matsukuma, K.E.; Walczak, R.; Collins, J.L.; Osborne, T.F.; Tontonoz, P. Direct and Indirect Mechanisms for Regulation of Fatty Acid Synthase Gene Expression by Liver X Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 11019–11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharski, M.; Kaczor, U. Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase – the Lipid Metabolism Regulator. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2014, 68, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Raalte, D.H.; Li, M.; Haydn Pritchard, P.; Wasan, K.M. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR)-: A Pharmacological Target with a Promising Future, 2004.

- Moruzzi, M.; Klöting, N.; Blüher, M.; Martinelli, I.; Tayebati, S.K.; Gabrielli, M.G.; Roy, P.; Micioni Di Bonaventura, M.V.; Cifani, C.; Lupidi, G.; et al. Tart Cherry Juice and Seeds Affect Pro-Inflammatory Markers in Visceral Adipose Tissue of High-Fat Diet Obese Rats. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimble, R.; Keane, K.M.; Lodge, J.K.; Howatson, G. The Influence of Tart Cherry (Prunus Cerasus, Cv Montmorency) Concentrate Supplementation for 3 Months on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Middle-Aged Adults: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, S.C.; Davis, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zha, L.; Kirschner, K.F. Effects of Tart Cherry Juice on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Older Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, S.C.; Davis, K.; Wright, R.S.; Kuczmarski, M.F.; Zhang, Z. Impact of Tart Cherry Juice on Systolic Blood Pressure and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Food Funct 2018, 9, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.; Bottoms, L.; Dillon, S.; Allan, R.; Shadwell, G.; Butters, B. Effects of Montmorency Tart Cherry and Blueberry Juice on Cardiometabolic and Other Health-Related Outcomes: A Three-Arm Placebo Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Navaei, N.; Pourafshar, S.; Jaime, S.J.; Akhavan, N.S.; Alvarez-Alvarado, S.; Proaño, G.V.; Litwin, N.S.; Clark, E.A.; Foley, E.M.; et al. Effects of Montmorency Tart Cherry Juice Consumption on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. J Med Food 2020, 23, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, A.; Mathew, S.; Moore, C.T.; Russell, J.; Robinson, E.; Soumpasi, V.; Barker, M.E. Effect of a Tart Cherry Juice Supplement on Arterial Stiffness and Inflammation in Healthy Adults: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2014, 69, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csiki, Z.; Papp-Bata, A.; Czompa, A.; Nagy, A.; Bak, I.; Lekli, I.; Javor, A.; Haines, D.D.; Balla, G.; Tosaki, A. Orally Delivered Sour Cherry Seed Extract (SCSE) Affects Cardiovascular and Hematological Parameters in Humans. Phytotherapy Research 2015, 29, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziadek, K.; Kopeć, A.; Piątkowska, E.; Leszczyńska, T. High-Fructose Diet-Induced Metabolic Disorders Were Counteracted by the Intake of Fruit and Leaves of Sweet Cherry in Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar, R.S.; Knapp, D.; Wanders, D.; Feresin, R.G. Raspberry and Blackberry Act in a Synergistic Manner to Improve Cardiac Redox Proteins and Reduce NF-ΚB and SAPK/JNK in Mice Fed a High-Fat, High-Sucrose Diet. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2022, 32, 1784–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serino, A.; Zhao, Y.; Hwang, J.; Cullen, A.; Deeb, C.; Akhavan, N.; Arjmandi, B.; Salazar, G. Gender Differences in the Effect of Blackberry Supplementation in Vascular Senescence and Atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− Mice. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2020, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaume, L.; Gilbert, W.C.; Brownmiller, C.; Howard, L.R.; Devareddy, L. Cyanidin 3-O-β-d-Glucoside-Rich Blackberries Modulate Hepatic Gene Expression, and Anti-Obesity Effects in Ovariectomized Rats. J Funct Foods 2012, 4, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, M.L.; Najjar, R.S.; Danh, J.P.; Knapp, D.; Wanders, D.; Feresin, R.G. Berry Consumption Mitigates the Hypertensive Effects of a High-Fat, High-Sucrose Diet via Attenuation of Renal and Aortic AT1R Expression Resulting in Improved Endothelium-Derived NO Bioavailability. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2023, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Moruá, M.S.; Hidalgo, O.; Morera, J.; Rojas, G.; Pérez, A.M.; Vaillant, F.; Fonseca, L. Hypolipidaemic, Hypoglycaemic and Antioxidant Effects of a Tropical Highland Blackberry Beverage Consumption in Healthy Individuals on a High-Fat, High-Carbohydrate Diet Challenge. J Berry Res 2020, 10, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pang, W.; He, C.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, C. Blueberry Anthocyanin-Enriched Extracts Attenuate Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5)-Induced Cardiovascular Dysfunction. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gallegos, J.L.; Haskell-ramsay, C.; Lodge, J.K. Effects of Blueberry Consumption on Cardiovascular Health in Healthy Adults: A Cross-Over Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, P.J.; Van Der Velpen, V.; Berends, L.; Jennings, A.; Feelisch, M.; Umpleby, A.M.; Evans, M.; Fernandez, B.O.; Meiss, M.S.; Minnion, M.; et al. Blueberries Improve Biomarkers of Cardiometabolic Function in Participants with Metabolic Syndrome-Results from a 6-Month, Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2019, 109, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stull, A.J.; Cash, K.C.; Champagne, C.M.; Gupta, A.K.; Boston, R.; Beyl, R.A.; Johnson, W.D.; Cefalu, W.T. Blueberries Improve Endothelial Function, but Not Blood Pressure, in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4107–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, P.J.; Berends, L.; van der Velpen, V.; Jennings, A.; Haag, L.; Chandra, P.; Kay, C.D.; Rimm, E.B.; Cassidy, A. Blueberry Anthocyanin Intake Attenuates the Postprandial Cardiometabolic Effect of an Energy-Dense Food Challenge: Results from a Double Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial in Metabolic Syndrome Participants. Clinical Nutrition 2022, 41, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, M.; Horne, J.; Guénard, F.; de Toro-Martín, J.; Garneau, V.; Guay, V.; Kearney, M.; Pilon, G.; Roy, D.; Couture, P.; et al. An 8-Week Freeze-Dried Blueberry Supplement Impacts Immune-Related Pathways: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Genes Nutr 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.A.; Feresin, R.G.; Navaei, N.; Figueroa, A.; Elam, M.L.; Akhavan, N.S.; Hooshmand, S.; Pourafshar, S.; Payton, M.E.; Arjmandi, B.H. Effects of Daily Blueberry Consumption on Circulating Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Antioxidant Defense in Postmenopausal Women with Pre- and Stage 1-Hypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial. In Proceedings of the Food and Function; Royal Society of Chemistry, January 1 2017; Vol. 8, pp. 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Noratto, G.; Chew, B.P.; Ivanov, I. Red Raspberry Decreases Heart Biomarkers of Cardiac Remodeling Associated with Oxidative and Inflammatory Stress in Obese Diabetic Db/Db Mice. Food Funct 2016, 7, 4944–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenakker, N.E.; Vendrame, S.; Tsakiroglou, P.; Klimis-Zacas, D. Red Raspberry (Rubus Idaeus) Consumption Restores the Impaired Vasoconstriction and Vasorelaxation Response in the Aorta of the Obese Zucker Rat, a Model of the Metabolic Syndrome. J Berry Res 2021, 11, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Zhu, L.; Edirisinghe, I.; Fareed, J.; Brailovsky, Y.; Burton-Freeman, B. Attenuation of Postmeal Metabolic Indices with Red Raspberries in Individuals at Risk for Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity 2019, 27, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Fu, D.X.; Wilkinson, M.; Simmons, B.; Wu, M.; Betts, N.M.; Du, M.; Lyons, T.J. Strawberries Decrease Atherosclerotic Markers in Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrition Research 2010, 30, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunino, S.J.; Parelman, M.A.; Freytag, T.L.; Stephensen, C.B.; Kelley, D.S.; MacKey, B.E.; Woodhouse, L.R.; Bonnel, E.L. Effects of Dietary Strawberry Powder on Blood Lipids and Inflammatory Markers in Obese Human Subjects. British Journal of Nutrition 2012, 108, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.K.; Skulas-Ray, A.C.; Gaugler, T.L.; Lambert, J.D.; Proctor, D.N.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Incorporating Freeze-Dried Strawberry Powder into a High-Fat Meal Does Not Alter Postprandial Vascular Function or Blood Markers of Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017, 105, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djurica, D.; Holt, R.R.; Ren, J.; Shindel, A.W.; Hackman, R.M.; Keen, C.L. Effects of a Dietary Strawberry Powder on Parameters of Vascular Health in Adolescent Males. British Journal of Nutrition 2016, 116, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Izuora, K.; Betts, N.M.; Kinney, J.W.; Salazar, A.M.; Ebersole, J.L.; Scofield, R.H. Dietary Strawberries Improve Cardiometabolic Risks in Adults with Obesity and Elevated Serum Ldl Cholesterol in a Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, C.L.; Edirisinghe, I.; Kappagoda, T.; Burton-Freeman, B. Attenuation of Meal-Induced Inflammatory and Thrombotic Responses in Overweight Men and Women After 6-Week Daily Strawberry (Fragaria) Intake; 2011; Vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Zasowska-Nowak, A.; Nowak, P.J.; Bialasiewicz, P.; Prymont-Przyminska, A.; Zwolinska, A.; Sarniak, A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Markowski, J.; Rutkowski, K.P.; Nowak, D. Strawberries Added to the Usual Diet Suppress Fasting Plasma Paraoxonase Activity and Have a Weak Transient Decreasing Effect on Cholesterol Levels in Healthy Nonobese Subjects. J Am Coll Nutr 2016, 35, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Morris, S.; Nguyen, A.; Betts, N.M.; Fu, D.; Lyons, T.J. Effects of Dietary Strawberry Supplementation on Antioxidant Biomarkers in Obese Adults with Above Optimal Serum Lipids. J Nutr Metab 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, C.K.; Skulas-Ray, A.C.; Gaugler, T.L.; Meily, S.; Petersen, K.S.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial of Freeze-Dried Strawberry Powder Supplementation in Adults with Overweight or Obesity and Elevated Cholesterol. Journal of the American Nutrition Association 2023, 42, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’DOHERTY, A.F.; JONES, H.S.; SATHYAPALAN, T.; INGLE, L.; CARROLL, S. The Effects of Acute Interval Exercise and Strawberry Intake on Postprandial Lipemia. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017, 49, 2315–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazen, S.; Amani, R.; Homayouni Rad, A.; Shahbazian, H.; Ahmadi, K.; Taha Jalali, M. Effects of Freeze-Dried Strawberry Supplementation on Metabolic Biomarkers of Atherosclerosis in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Ann Nutr Metab 2013, 63, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Betts, N.M.; Nguyen, A.; Newman, E.D.; Fu, D.; Lyons, T.J. Freeze-Dried Strawberries Lower Serum Cholesterol and Lipid Peroxidation in Adults with Abdominal Adiposity and Elevated Serum Lipids. Journal of Nutrition 2014, 144, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.L.; Pandey, S. Juice Blends-a Way of Utilization of under-Utilized Fruits, Vegetables, and Spices: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2011, 51, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounir, S.; Siliha, H.; Ragab, M.; Ghandour, A.; Sunooj, K.V.; Farid, E. Extraction of Fruit Juices. In Extraction Processes in the Food Industry; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 197–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, J.M.R.; Sattar, N. Fruit Juice: Just Another Sugary Drink? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014, 2, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, S.; Dal Bosco, A.; Castellini, C.; Falcinelli, B.; Sileoni, V.; Marconi, O.; Mancinelli, A.C.; Cotozzolo, E.; Benincasa, P. Effect of Heat- and Freeze-Drying Treatments on Phytochemical Content and Fatty Acid Profile of Alfalfa and Flax Sprouts. J Sci Food Agric 2019, 99, 4029–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, G.F.; Shen, C.; Xu, X.R.; Kuang, R.D.; Guo, Y.J.; Zeng, L.S.; Gao, L.L.; Lin, X.; Xie, J.F.; Xia, E.Q.; et al. Potential of Fruit Wastes as Natural Resources of Bioactive Compounds. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 8308–8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soong, Y.Y.; Barlow, P.J. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Content of Selected Fruit Seeds. Food Chem 2004, 88, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, M.C.; Ellmore, G.S.; McKeown, N. Seeds-Health Benefits, Barriers to Incorporation, and Strategies for Practitioners in Supporting Consumption among Consumers. Nutr Today 2016, 51, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.E. de F.; Abud, A.K. de S. Tropical Fruit Pulps: Processing, Product Standardization and Main Control Parameters for Quality Assurance. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology 2017, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) Scientific Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Anthocyanins (E 163) as a Food Additive. EFSA Journal 2013, 11. [CrossRef]

- WHO Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 15 March 2024).

| Cherry | Blackberry | Blueberry | Strawberry | Raspberry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount per 100 g of edible portion | |||||

| Energy (g) | 67.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 34.00 | 49.00 |

| Lipids (g) | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| Saturated fatty acids (g) | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MUFA (g) | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| PUFA (g) | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| Linoleic acid (g) | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| Trans fatty acids (g) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 13.30 | 4.50 | 6.40 | 5.30 | 5.10 |

| Sugar (g) | 13.30 | 4.20 | 6.40 | 5.30 | 5.10 |

| Oligosaccharides (g) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fibre (g) | 1.60 | 4.60 | 3.10 | 2.00 | 6.70 |

| Protein (g) | 0.80 | 1.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.90 |

| Salt (g) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Water (g) | 82.60 | 88.00 | 87.00 | 90.10 | 84.30 |

| Organic acids (g) | 0.40 | 0.90 | 1.40 | 0.80 | 1.90 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 24.00 | 27.00 | 8.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| Carotene (µg) | 141.00 | 164.00 | 47.00 | 26.00 | 10.00 |

| Vitamin D (µg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| α-tocopherol (mg) | 0.13 | 4.42 | 1.90 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Thiamine (mg) | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Niacin (mg) | 0.20 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| Tryptophan/60 (mg) | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 6.00 | 16.50 | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.30 |

| Pholate (µg) | 5.00 | 25.00 | 11.5 | 47.00 | 0.33 |

| Ash (g) | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| Sodium (mg) | 1.00 | 1.80 | 0.30 | 2.00 | 1.00 |

| Potassium (mg) | 210.00 | 240.00 | 110.00 | 140.00 | 230.00 |

| Calcium (mg) | 14.00 | 28.00 | 19.00 | 25.00 | 26.00 |

| Phosphorous (mg) | 15.00 | 33.00 | 20.00 | 26.00 | 23.00 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 10.00 | 22.00 | 9.00 | 10.00 | 20.00 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.50 |

| Zinc (mg) | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Selenium (µg) | n.a. | 0.10 | 0.10 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Iodol (µg) | n.a. | 0.40 | 1.00 | 3.80 | n.a. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).