Submitted:

13 April 2024

Posted:

16 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

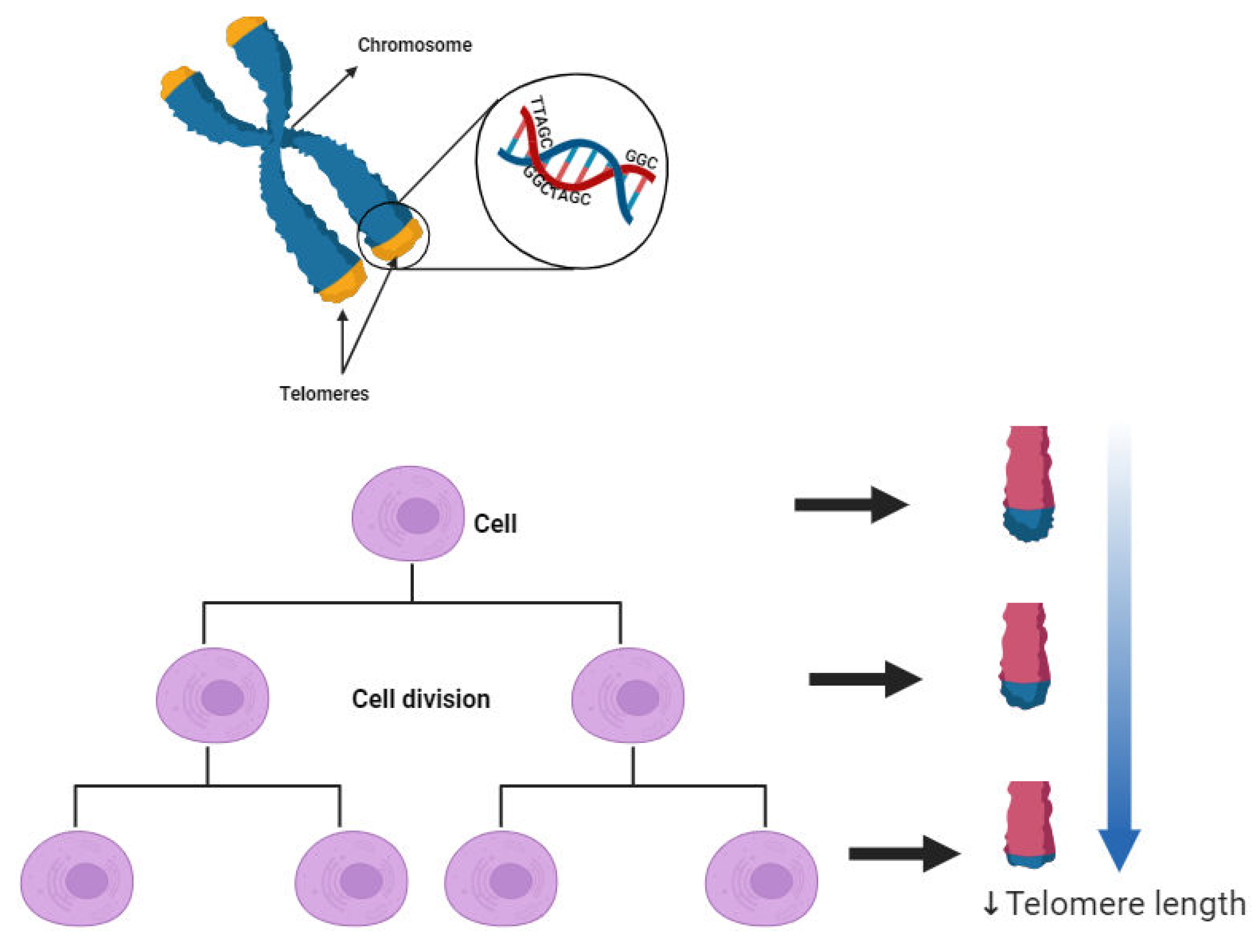

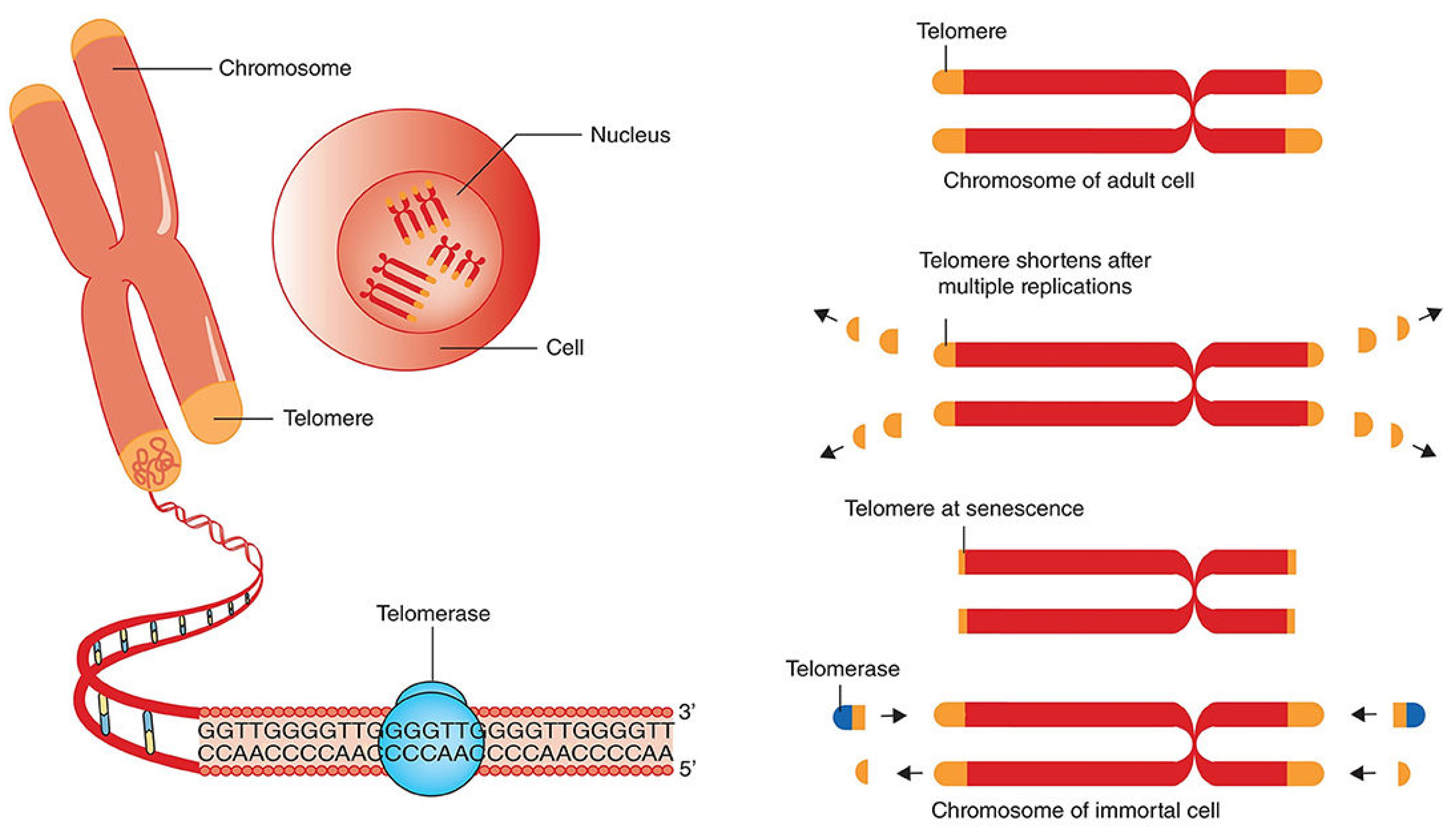

Introduction

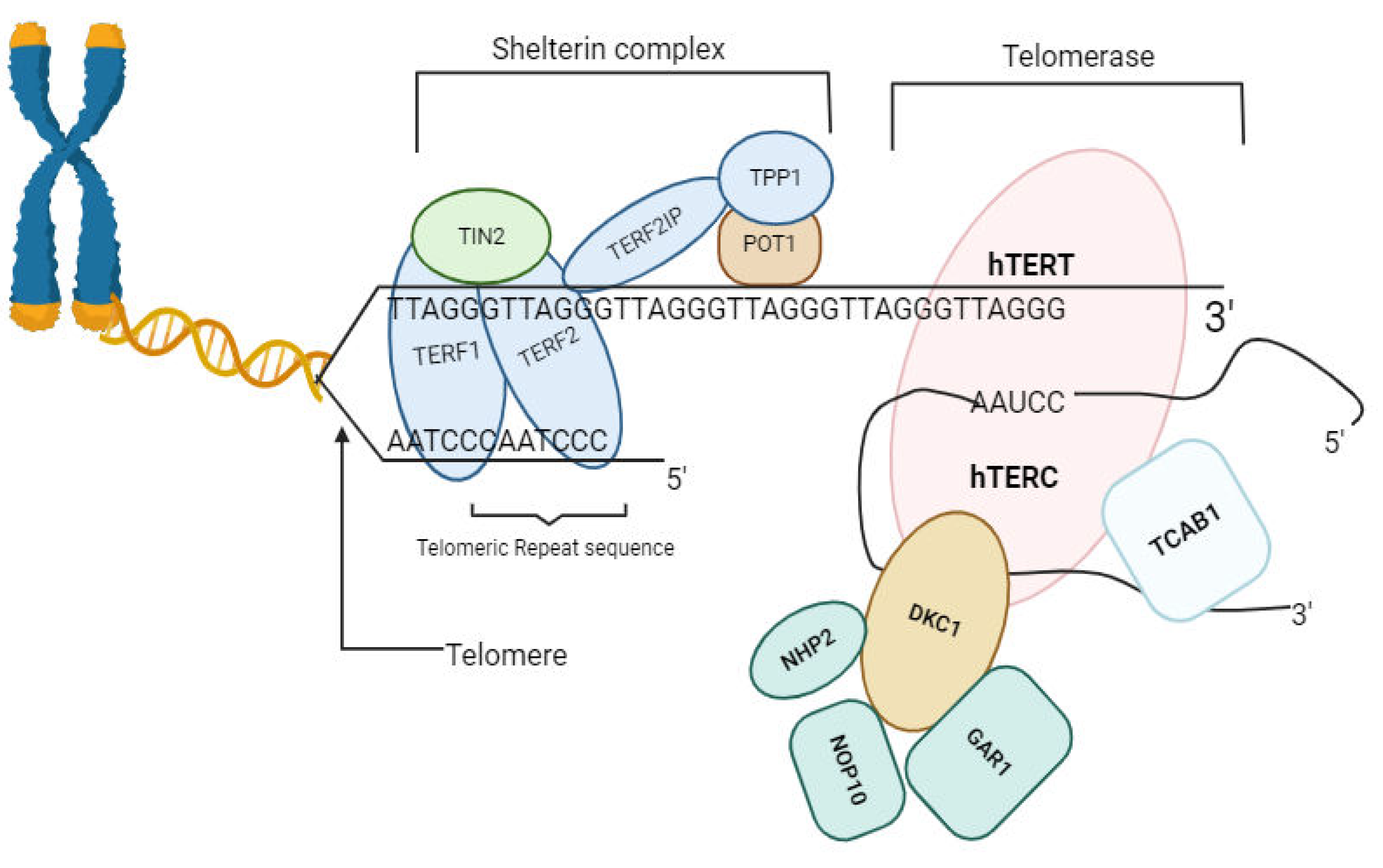

- hTERT: Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase; telomere elongation, maintaining chromosome stability. hTERC: Human Telomerase RNA Component; template for telomere synthesis, enabling telomerase action.

- POT1: Protection of Telomeres 1, TPP1: Adrenocortical Dysplasia Homolog (ACD) Protein or TINT1; telomerase recruitment to telomeres. TERF1: Telomeric Repeat-binding Factor 1; telomere protection. TERF2IP: Telomeric Repeat-binding Factor 2 Interacting Protein; stabilizes telomeres against chromosome end fusions. TIN2: TRF1-Interacting Nuclear Factor 2; Mediates interactions between telomere proteins, maintaining telomere integrity. DKC1: Dyskerin Pseudouridine Synthase 1; Modifies telomerase RNA, facilitating telomerase complex assembly. NHP2: Nucleolar Protein 2; Aids in telomerase complex assembly, crucial for telomere elongation. NOP10: Nucleolar Protein 10; Essential for telomerase stability and function in telomere maintenance. GAR1: Guide to the Function of NHP2-like Protein 1; Maintains telomerase RNA stability, ensuring proper telomerase function. TCAB1: Telomerase Cajal Body Protein 1; Guides telomerase to nuclear compartments.

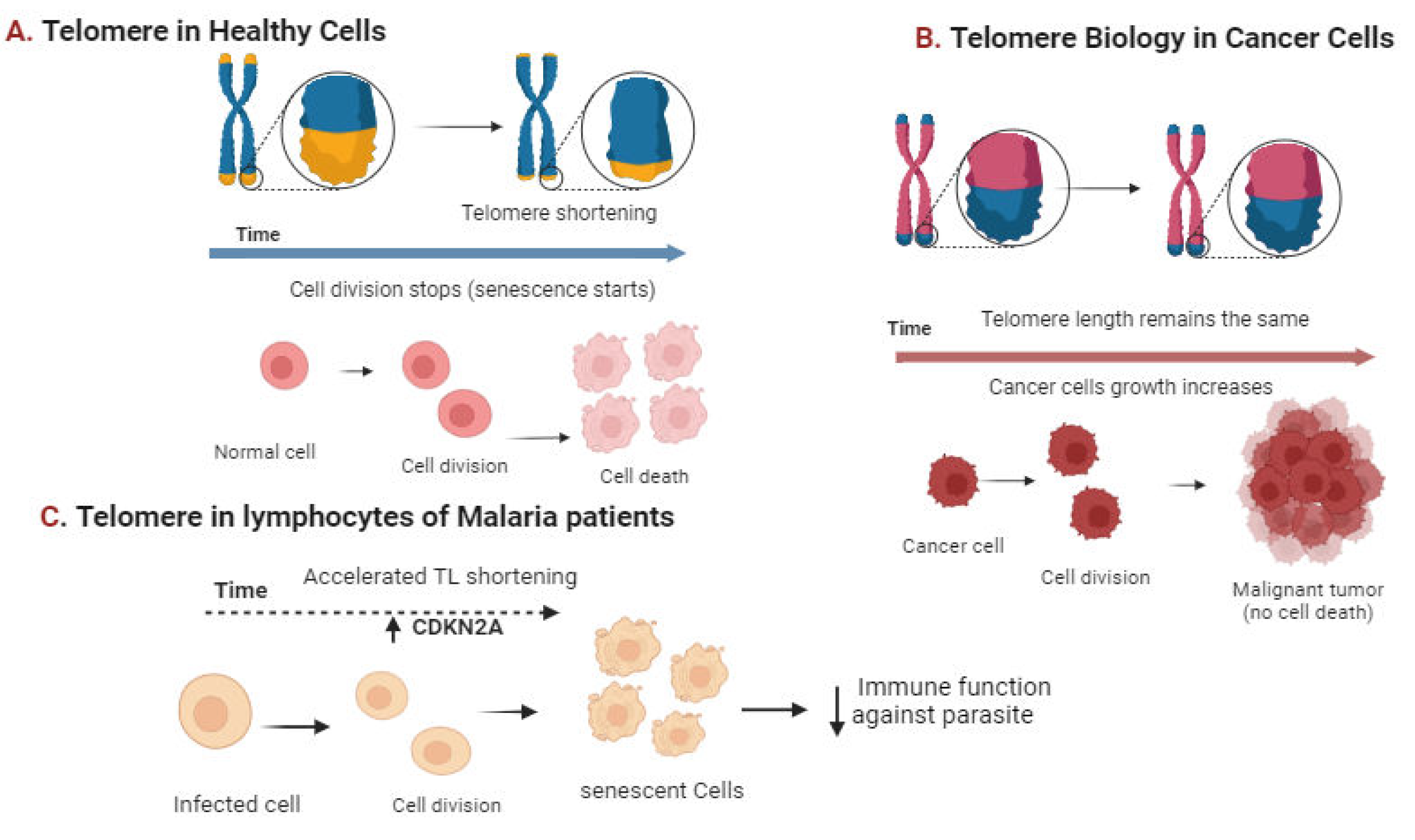

Telomeres and Telomerase implication in Health and Disease

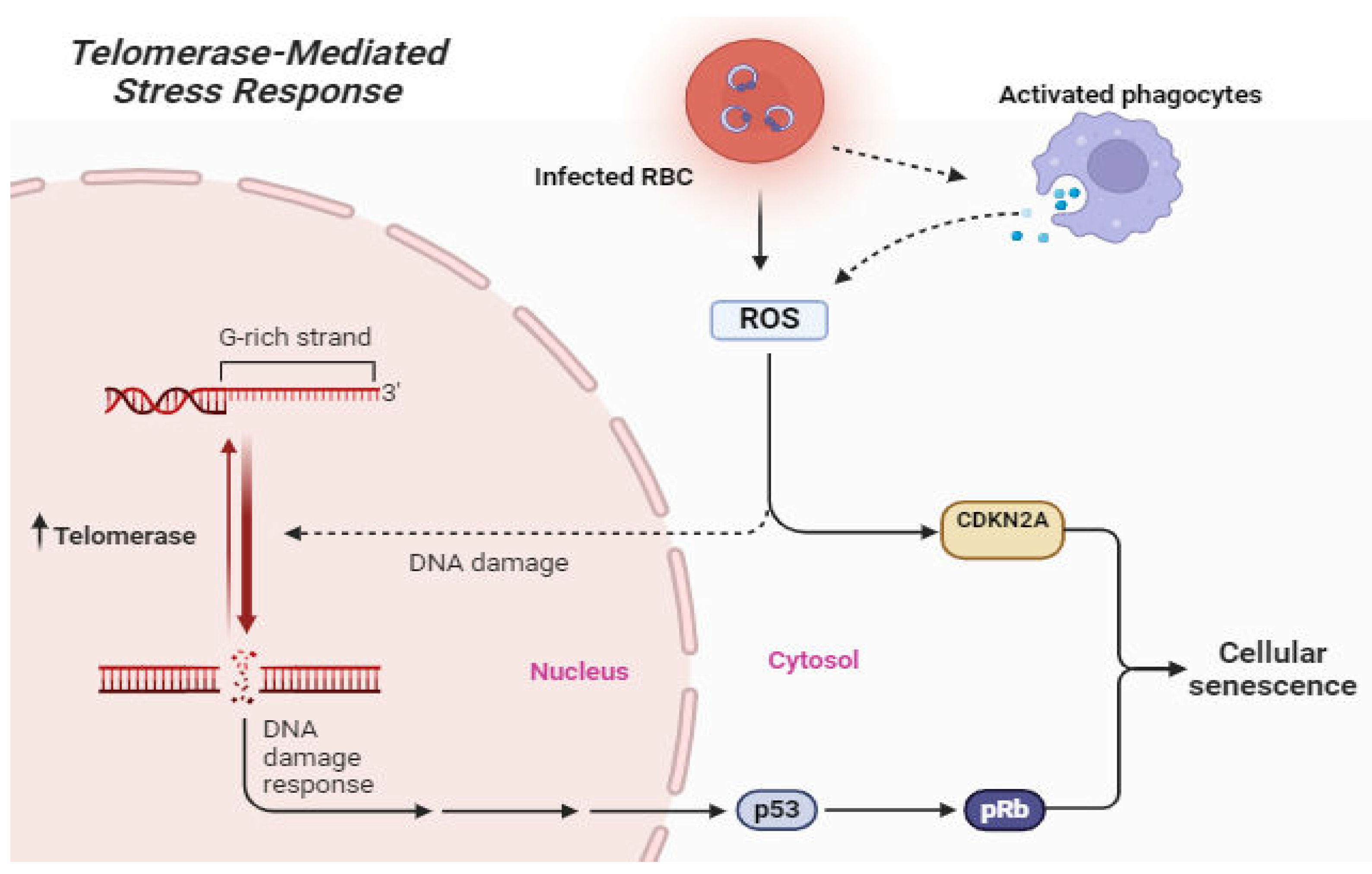

Telomere Length and Telomerase dynamics in Malaria

Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential of Telomeres and Telomerase in Malaria

Telomere Length Regulation in Malaria Parasite

Top of Form

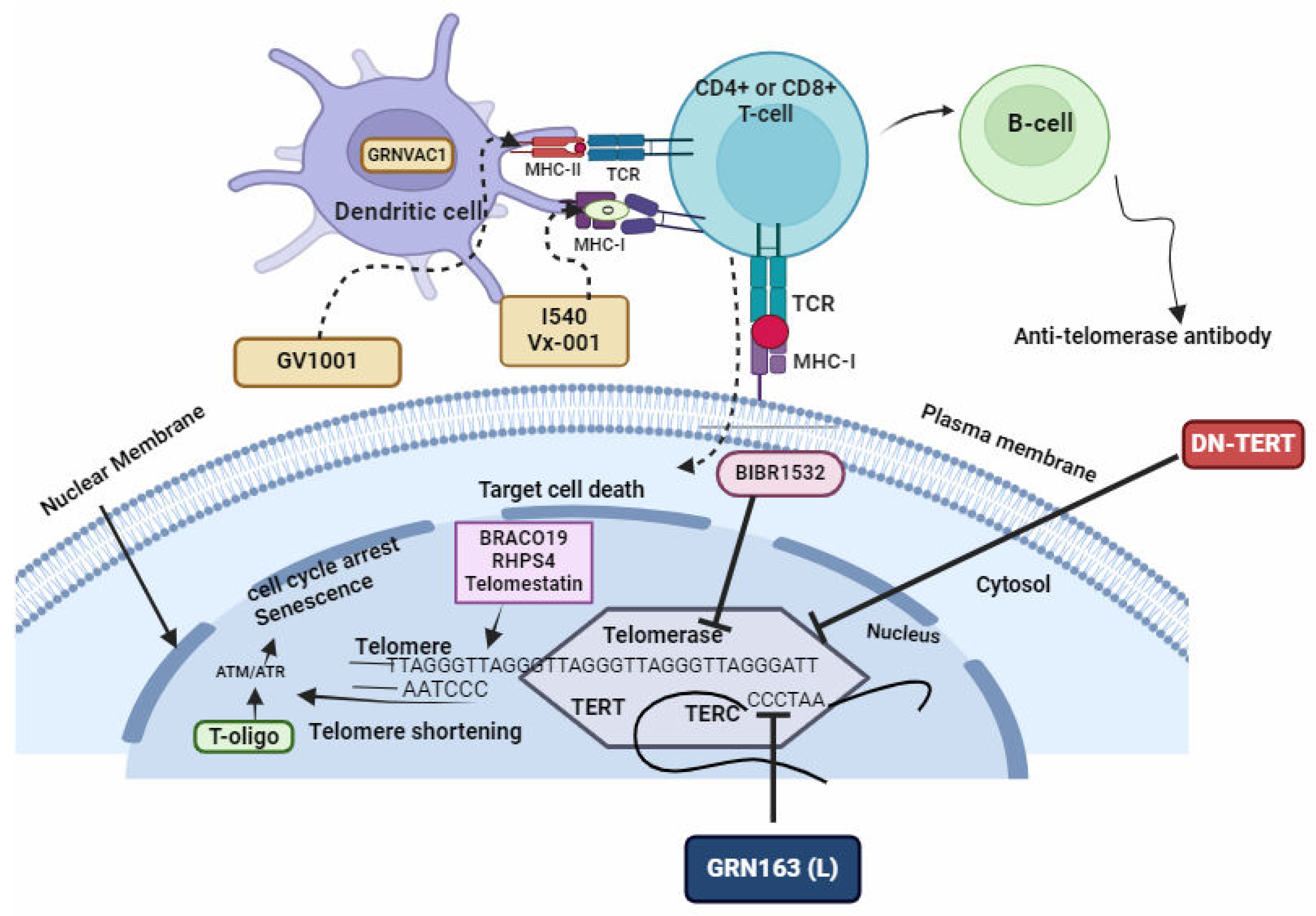

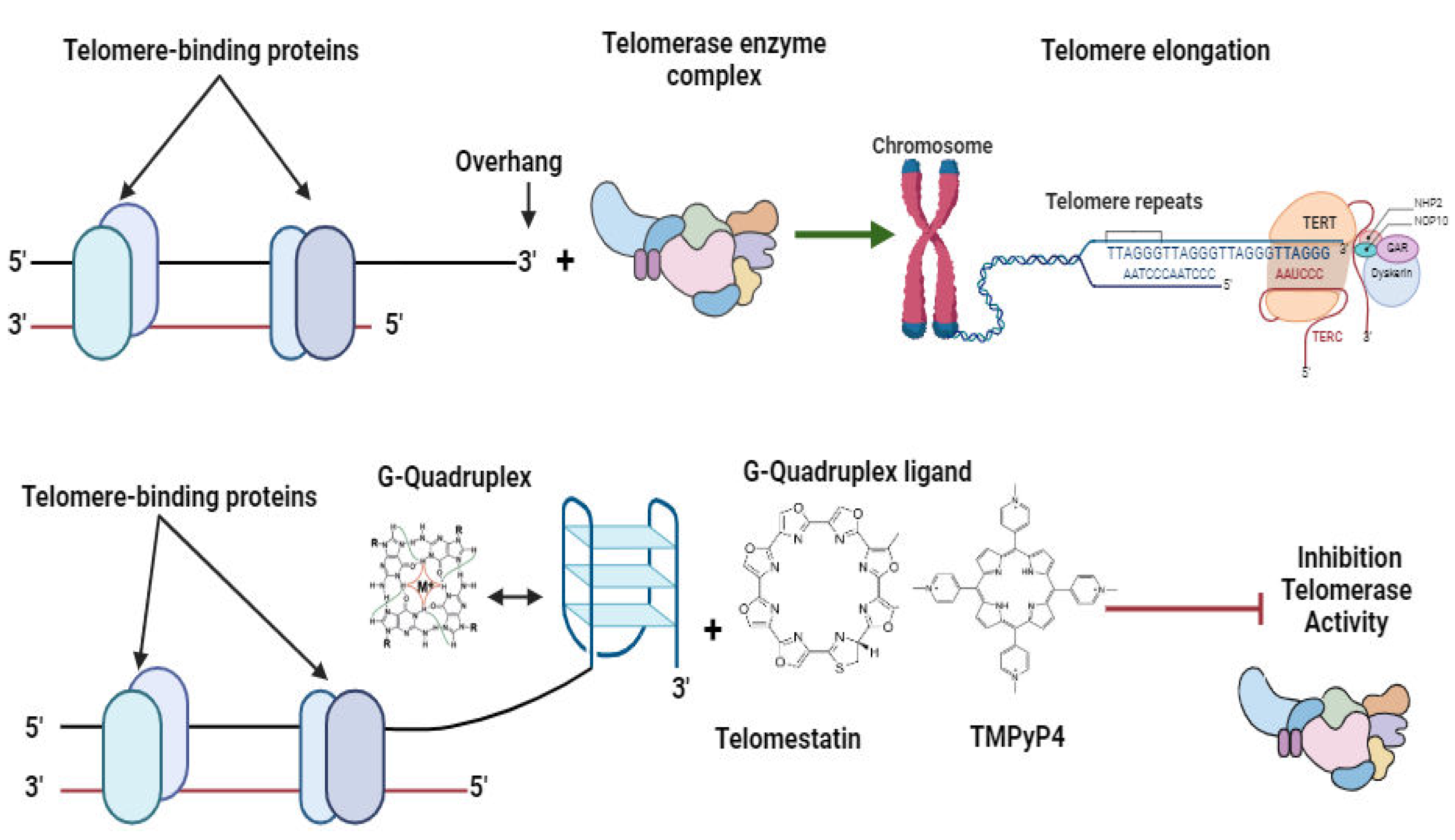

Telomeres and Telomerase-Targeting Drugs

GRN163(L), DN-TERT, and BIBR1532

BRACO19, RHPS4, and Telomestatin

T-Oligo

Immunization Involving Peptides Derived from TERT or the Introduction of TERT mRNA into Dendritic Cells

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrade, M.V.; Noronha, K.; Diniz, B.P.C.; et al. The economic burden of malaria: a systematic review. Malaria Journal 2022, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, L. World Malaria Report 2023: Key findings from the report. Target Malaria. Published , 2023. Accessed December 16, 2023. https://targetmalaria.org/latest/news/world-malaria-report-2023-key-findings-from-the-report/. 4 December.

- Gilbert, M.; Pullano, G.; Pinotti, F.; et al. Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet 2020, 395, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkengasong, J.N.; Mankoula, W. Looming threat of COVID-19 infection in Africa: act collectively, and fast. Lancet 2020, 395, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.J.; Bertozzi-Villa, A.; Rumisha, S.F.; et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on malaria intervention coverage, morbidity, and mortality in Africa: a geospatial modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2016 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators. Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 391, 2236–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, C.; Sturrock, H.J.W.; Hsiang, M.S.; et al. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: new strategies for new challenges. Lancet 2013, 382, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, H.J.; Tajudeen, Y.A.; Oladunjoye, I.O.; et al. Increasing challenges of malaria control in sub-Saharan Africa: Priorities for public health research and policymakers. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siao, M.C.; Borner, J.; Perkins, S.L.; Deitsch, K.W.; Kirkman, L.A. Evolution of Host Specificity by Malaria Parasites through Altered Mechanisms Controlling Genome Maintenance. mBio 2020, 11, e03272–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.Z.; Lane, K.D.; Xia, L.; Sá, J.M.; Wellems, T.E. Plasmodium Genomics and Genetics: New Insights into Malaria Pathogenesis, Drug Resistance, Epidemiology, and Evolution. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019, 32, e00019–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, M.; Hasselquist, D.; Hansson, B.; Zehtindjiev, P.; Westerdahl, H.; Bensch, S. Hidden costs of infection: Chronic malaria accelerates telomere degradation and senescence in wild birds. Science 2015, 347, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, M.; Palinauskas, V.; Zaghdoudi-Allan, N.; et al. Parallel telomere shortening in multiple body tissues owing to malaria infection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 283, 20161184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, S.F.; Reed, J.; Alexander, N.; Mason, C.E.; Deitsch, K.W.; Kirkman, L.A. Chromosome End Repair and Genome Stability in Plasmodium falciparum. mBio 2017, 8, 10.1128/mbio.00547–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cian, A.; Grellier, P.; Mouray, E.; et al. Plasmodium telomeric sequences: structure, stability and quadruplex targeting by small compounds. Chembiochem 2008, 9, 2730–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.S. Tell me more – telomere biology and understanding telomere defects. Pathology. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Songyang, Z.; Wan, M. Telomeres - Structure, Function, and Regulation. Experimental cell research 2013, 319, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, L.; Rogers, B.; Thomas, E.; et al. Telomere and Telomerase-Associated Proteins in Endometrial Carcinogenesis and Cancer-Associated Survival. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greider, C.W.; Blackburn, E.H. The telomere terminal transferase of Tetrahymena is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme with two kinds of primer specificity. Cell 1987, 51, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Telomere components as potential therapeutic targets for treating microbial pathogen infections. Frontiers in Oncology, /: Accessed , 2023. https, 2 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnell, E.; Pasquier, E.; Wellinger, R.J. Telomere Replication: Solving Multiple End Replication Problems. Front Cell Dev Biol, 6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.Z.; Allsopp, R.C.; Futcher, A.B.; Greider, C.W.; Harley, C.B. Telomere end-replication problem and cell aging. Journal of Molecular Biology 1992, 225, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestroni, L.; Matmati, S.; Coulon, S. Solving the Telomere Replication Problem. Genes 2017, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, D.; LaBella, K.A.; DePinho, R.A. Telomeres: history, health, and hallmarks of aging. Cell 2021, 184, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S. Telomeres in health and disease. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2017, 21, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effros, R.B. Impact of the Hayflick Limit on T cell responses to infection: lessons from aging and HIV disease. Mech Ageing Dev 2004, 125, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulkiewicz, M.; Bajsert, J.; Kopczynski, P.; Barczak, W.; Rubis, B. Telomere length: how the length makes a difference. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 7181–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armanios, M. The Role of Telomeres in Human Disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. [CrossRef]

- GOMEZ DE, ARMANDO RG, FARINA HG, et al. Telomere structure and telomerase in health and disease. Int J Oncol 2012, 41, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanim, G.E.; Fountain, A.J.; van Roon, A.M.M.; et al. Structure of human telomerase holoenzyme with bound telomeric DNA. Nature 2021, 593, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Pellegrini, M.V. Biochemistry, Telomere And Telomerase. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed , 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 25 May 5764. [Google Scholar]

- Panasiak, L.; Kuciński, M.; Hliwa, P.; Pomianowski, K.; Ocalewicz, K. Telomerase Activity in Somatic Tissues and Ovaries of Diploid and Triploid Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Females. Cells (2073-4409) 2023, 12, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akincilar, S.C.; Unal, B.; Tergaonkar, V. Reactivation of telomerase in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guterres, A.N.; Villanueva, J. Targeting telomerase for cancer therapy. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5811–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B. Telomere components as potential therapeutic targets for treating microbial pathogen infections. Frontiers in Oncology, /: Accessed , 2023. https, 2 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roake, C.M.; Artandi, S.E. Regulation of human telomerase in homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottius, E.; Bakhsis, N.; Scherf, A. Plasmodium falciparum Telomerase: De Novo Telomere Addition to Telomeric and Nontelomeric Sequences and Role in Chromosome Healing. Mol Cell Biol 1998, 18, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, L.; Scherf, A. Plasmodium telomeres and telomerase: the usual actors in an unusual scenario. Chromosome Res 2005, 13, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiano, C.C.; Wasserman, M. Short communication - detection of telomerase activity in Plasmodium falciparum using a nonradioactive method. Published online , 2003. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://tspace.library.utoronto. 31 December 1807. [Google Scholar]

- Sekhri, K. Telomeres and telomerase: understanding basic structure and potential new therapeutic strategies targeting it in the treatment of cancer. J Postgrad Med 2014, 60, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Мoрoзoва ЛФ, Турбабина НА, Степанoва ЕВ, et al. Method of treating malaria using a therapeutic combination of telomerase inhibitors (iimatinib mesilate) and artemether. Published online , 2020. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://patents.google. 5 June 2722.

- Kim, N.W.; Piatyszek, M.A.; Prowse, K.R.; et al. Specific Association of Human Telomerase Activity with Immortal Cells and Cancer. Science 1994, 266, 2011–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Religa, A.A.; Ramesar, J.; Janse, C.J.; Scherf, A.; Waters, A.P. P. berghei telomerase subunit TERT is essential for parasite survival. PLoS One 2014, 9, e108930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.A.; Chakrabarti, K. Telomerase ribonucleoprotein and genome integrity—An emerging connection in protozoan parasites. WIREs RNA 2022, 13, e1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.; Chakrabarti, K. Current Perspectives of Telomerase Structure and Function in Eukaryotes with Emerging Views on Telomerase in Human Parasites. IJMS 2018, 19, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, E.P.; Wasserman, M. G-Quadruplex ligands: Potent inhibitors of telomerase activity and cell proliferation in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2016, 207, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzhals, R.L.; Fanti, L.; Ebsen, A.C.G.; Rong, Y.S.; Pimpinelli, S.; Golic, K.G. Chromosome Healing Is Promoted by the Telomere Cap Component Hiphop in Drosophila. Genetics 2017, 207, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, E.H. Telomeres and telomerase: their mechanisms of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS Lett 2005, 579, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Ulloque-Badaracco, J.R.; Alarcón-Braga, E.A.; Fernández-Alonso, A.M.; López-Baena, M.T.; Pérez-López, F.R. Telomerase activity and telomere length in women with breast cancer or without malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

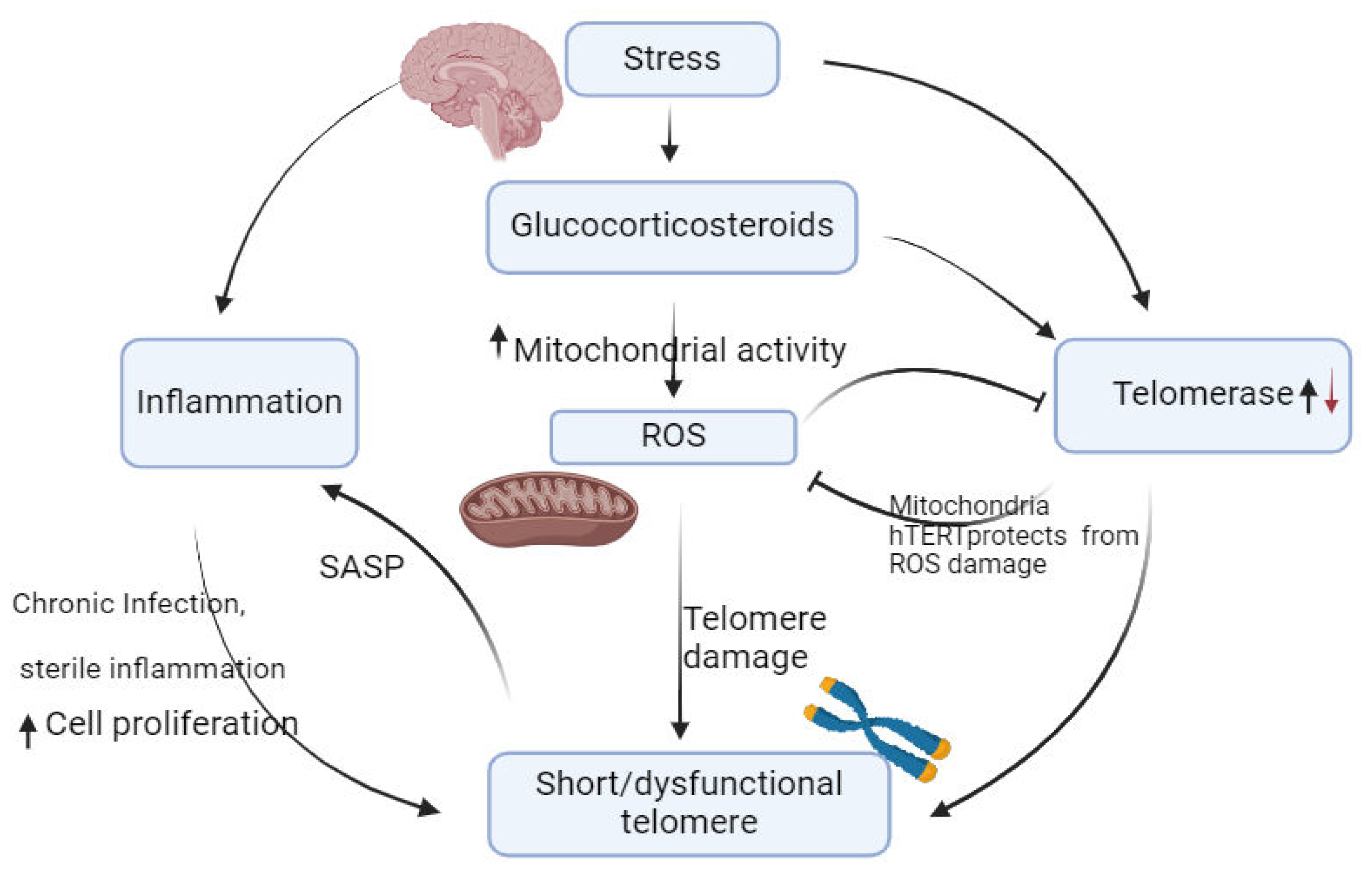

- Lin, J.; Epel, E. Stress and telomere shortening: Insights from cellular mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.P.; Fouquerel, E.; Opresko, P.L. The impact of oxidative DNA damage and stress on telomere homeostasis. Mech Ageing Dev. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E.; Boonekamp, J. Does oxidative stress shorten telomeres in vivo? A meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niveta, J.P.S.; Kumar, M.A.; Parvathi, V.D. Telomere attrition and inflammation: the chicken and the egg story. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 2022, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, M.P.; Santana, B.A.; Conran, N.; et al. Telomere length correlates with disease severity and inflammation in sickle cell disease. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 2017, 39, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Lingner, J. Impact of oxidative stress on telomere biology. Differentiation. [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Aubert, G.; Ripoll-Cladellas, A.; et al. Genetic, parental and lifestyle factors influence telomere length. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Blackburn, E. Telomeres and lifestyle factors: Roles in cellular aging. Mutation research. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, S.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Association Between Riboflavin Intake and Telomere Length: A Cross-Sectional Study From National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Frontiers in Nutrition, /: Accessed , 2023. https, 3 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tarry-Adkins, J.L.; Fernandez-Twinn, D.S.; Chen, J.H.; et al. Poor maternal nutrition and accelerated postnatal growth induces an accelerated aging phenotype and oxidative stress in skeletal muscle of male rats. Dis Model Mech 2016, 9, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilmonen, P.; Kotrschal, A.; Penn, D.J. Telomere Attrition Due to Infection. PLoS One 2008, 3, e2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraudeau, M.; Heidinger, B.; Bonneaud, C.; Sepp, T. Telomere shortening as a mechanism of long-term cost of infectious diseases in natural animal populations. Biol Lett 2019, 15, 20190190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albosale, A.H.; Mashkina, E.V. Association of Relative Telomere Length and Risk of High Human Papillomavirus Load in Cervical Epithelial Cells. Balkan J Med Genet 2021, 24, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.S.; Nguyen, M.T.N.; Pham, T.X.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Nonstructural 5A Protein Interacts with Telomere Length Regulation Protein: Implications for Telomere Shortening in Patients Infected with HCV. Mol Cells 2022, 45, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, E.; Samper, E.; Martín-Caballero, J.; Flores, J.M.; Lee, H.; Blasco, M.A. Disease states associated with telomerase deficiency appear earlier in mice with short telomeres. The EMBO Journal 1999, 18, 2950–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthe, D.M.; Thoma, O.M.; Sperka, T.; Neurath, M.F.; Waldner, M.J. Telomerase deficiency reflects age-associated changes in CD4+ T cells. Immunity & Ageing 2022, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.; Weng, N.P. Expression and regulation of telomerase in human T cell differentiation, activation, aging and diseases. Cell Immunol, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, H.F.; Effros, R.B. Divergent telomerase and CD28 expression patterns in human CD4 and CD8 T cells following repeated encounters with the same antigenic stimulus. Clin Immunol 2002, 105, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalzini, A.; Ballin, G.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, S.; et al. Size of HIV-1 reservoir is associated with telomere shortening and immunosenescence in early-treated European children with perinatally acquired HIV-1. J Int AIDS Soc 2021, 24, e25847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmonen, P.; Kotrschal, A.; Penn, D.J. Telomere Attrition Due to Infection. PLOS ONE 2008, 3, e2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.N.; Beverley, P.C.L.; Salmon, M. Will telomere erosion lead to a loss of T-cell memory? Nat Rev Immunol 2004, 4, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelec, G.; Akbar, A.; Caruso, C.; Solana, R.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B.; Wikby, A. Human immunosenescence: is it infectious? Immunological Reviews 2005, 205, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray-Miceli, D.; Gray, K.; Sorenson, M.R.; Holtzclaw, B.J. Immunosenescence and Infectious Disease Risk Among Aging Adults. Advances in Family Practice Nursing 2023, 5, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Yman, V.; Homann, M.V.; et al. Cellular aging dynamics after acute malaria infection: A 12-month longitudinal study. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglar, A. The Effect of Plasmodium Infection on Cellular Aging in Humans. Inst för medicin, Solna / Dept of Medicine, Solna; 2023. Accessed , 2023. http://openarchive.ki. 10 April 1061. [Google Scholar]

- Miglar, A.; Reuling, I.J.; Yap, X.Z.; Färnert, A.; Sauerwein, R.W.; Asghar, M. Biomarkers of cellular aging during a controlled human malaria infection. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 18733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durso, D.F.; Silveira-Nunes, G.; Coelho, M.M.; et al. Living in endemic area for infectious diseases accelerates epigenetic age. Mech Ageing Dev, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojcic, S.; Kuk, N.; Ullah, I.; Sterkers, Y.; Merrick, C.J. Single-molecule analysis reveals that DNA replication dynamics vary across the course of schizogony in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, D.K.; Das, B.R.; Dash, A.P.; Supakar, P.C. Identification of telomerase activity in gametocytes of Plasmodium falciparum. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2003, 309, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołodziej-Sobocińska, M. Factors affecting the spread of parasites in populations of wild European terrestrial mammals. Mamm Res 2019, 64, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Smallbone, J.; Jensen, A.L.; Roberts, L.E.; Totañes, F.I.G.; Hart, S.R.; Merrick, C.J. Plasmodium falciparum GBP2 Is a Telomere-Associated Protein That Binds to G-Quadruplex DNA and RNA. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022; 12, 782537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.J.; Hall, N.; Fung, E.; et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 2002, 419, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwapisz, M.; Morillon, A. Subtelomeric Transcription and its Regulation. Journal of Molecular Biology 2020, 432, 4199–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherf, A.; Figueiredo, L.M.; Freitas-Junior, L.H. Plasmodium telomeres: a pathogen’s perspective. Curr Opin Microbiol 2001, 4, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Portillo, H.A.; Fernandez-Becerra, C.; Bowman, S.; et al. A superfamily of variant genes encoded in the subtelomeric region of Plasmodium vivax. Nature 2001, 410, 839–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, R.B.D.; Silva, T.M.; Kaiser, C.S.; et al. Independent regulation of Plasmodium falciparum rif gene promoters. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraisingh, M.T.; Voss, T.S.; Marty, A.J.; et al. Heterochromatin Silencing and Locus Repositioning Linked to Regulation of Virulence Genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Cell 2005, 121, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.F.; Zhang, Y.L. PfSWIB, a potential chromatin regulator for var gene regulation and parasite development in Plasmodium falciparum. Parasites & Vectors 2020, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Palinauskas, V.; Zaghdoudi-Allan, N.; et al. Parallel telomere shortening in multiple body tissues owing to malaria infection. Proc R Soc B 2016, 283, 20161184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Kirkman, L.A.; Kafsack, B.F.; Mason, C.E.; Deitsch, K.W. Telomere length dynamics in response to DNA damage in malaria parasites. iScience 2021, 24, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, M.; Palinauskas, V.; Zaghdoudi-Allan, N.; et al. Parallel telomere shortening in multiple body tissues owing to malaria infection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 283, 20161184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.; Gupta, A.; Bhatnagar, S. Modeling of Plasmodium falciparum Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Ternary Complex: Repurposing of Nucleoside Analog Inhibitors. Assay Drug Dev Technol 2015, 13, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feigon, J. Structural biology of telomerase and its interaction at telomeres. Curr Opin Struct Biol. [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Smallbone J, Jensen AL, Roberts LE, Totañes FIG, Hart SR, Merrick CJ. Plasmodium falciparum GBP2 Is a Telomere-Associated Protein That Binds to G-Quadruplex DNA and RNA. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2022;12. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2022.782537.

- Al-Turki, T.M.; Griffith, J.D. Mammalian telomeric RNA (TERRA) can be translated to produce valine–arginine and glycine–leucine dipeptide repeat proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2221529120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiserman, A.; Krasnienkov, D. Telomere Length as a Marker of Biological Age: State-of-the-Art, Open Issues, and Future Perspectives. Front Genet, 6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W. Role of Telomeres and Telomerase in Aging and Cancer. Cancer Discov 2016, 6, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svenson, U.; Nordfjäll, K.; Baird, D.; et al. Blood Cell Telomere Length Is a Dynamic Feature. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e21485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, R.; Takahama, S.; Yamamoto, M. Correlates of telomere length shortening in peripheral leukocytes of HIV-infected individuals and association with leukoaraiosis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0218996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, R.; Walter, S.; Rehkopf, D.H. Telomere length and health outcomes: A two-sample genetic instrumental variables analysis. Experimental Gerontology. [CrossRef]

- Helby, J.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Benfield, T.; Bojesen, S.E. Shorter leukocyte telomere length is associated with higher risk of infections: a prospective study of 75,309 individuals from the general population. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.V.; Schneider, K.M.; Teumer, A.; et al. Association of Telomere Length With Risk of Disease and Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine 2022, 182, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambo, M.; Mwinga, M.; Mumbengegwi, D.R. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) as quality assurance tools for Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) malaria diagnosis in Northern Namibia. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fali, T.; K’Ros, C.; Appay, V.; Sauce, D. Assessing T Lymphocyte Aging Using Telomere Length and Telomerase Activity Measurements in Low Cell Numbers. Methods Mol Biol. [CrossRef]

- Udroiu, I.; Marinaccio, J.; Sgura, A. Many Functions of Telomerase Components: Certainties, Doubts, and Inconsistencies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.; Collins, K. Human Telomerase Activation Requires Two Independent Interactions between Telomerase RNA and Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. Molecular cell. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, H.D.M.; West, S.C.; Beattie, T.L. InTERTpreting telomerase structure and function. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, 5609–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B. Keeping Balance Between Genetic Stability and Plasticity at the Telomere and Subtelomere of Trypanosoma brucei. Front Cell Dev Biol, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Telomeres and telomerase: three decades of progress. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.S.; Wright, W.E.; Shay, J.W. Human Telomerase and Its Regulation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2002, 66, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simantov, K.; Goyal, M.; Dzikowski, R. Emerging biology of noncoding RNAs in malaria parasites. PLOS Pathogens 2022, 18, e1010600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, L.; Scherf, A. Plasmodium telomeres and telomerase: the usual actors in an unusual scenario. Chromosome Res 2005, 13, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, B.C.D.; Shiburah, M.E.; Paiva, S.C.; et al. Possible Involvement of Hsp90 in the Regulation of Telomere Length and Telomerase Activity During the Leishmania amazonensis Developmental Cycle and Population Proliferation. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021; 9, 713415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.; Young, N. Telomeres, Telomerase, and Human Disease. The Hematologist, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.T.; Yewdell, W.T.; Wilkerson, K.L.; et al. Sex hormones, acting on the TERT gene, increase telomerase activity in human primary hematopoietic cells. Blood 2009, 114, 2236–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belachew, E.B. Immune Response and Evasion Mechanisms of Plasmodium falciparum Parasites. Journal of Immunology Research, 2018; 2018, e6529681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte-Reche, E.; Martínez-García, M.; Guédin, A.; et al. G-Quadruplex Identification in the Genome of Protozoan Parasites Points to Naphthalene Diimide Ligands as New Antiparasitic Agents. J Med Chem 2018, 61, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lujan, S.A.; Williams, J.S.; Kunkel, T.A. DNA polymerases divide the labor of genome replication. Trends Cell Biol 2016, 26, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, A.A.; Watson, C.M.; Noble, J.R.; Pickett, H.A.; Tam, P.P.L.; Reddel, R.R. Alternative lengthening of telomeres in normal mammalian somatic cells. Genes Dev 2013, 27, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, G.M. DNA Replication. In: The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd Edition. Sinauer Associates; 2000. Accessed , 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 28 March 9940. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen 2017, 58, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Pickett, H.A. Targeting telomeres: advances in telomere maintenance mechanism-specific cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer 2022, 22, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, K.; Nyhan, K.; Han, L.; Murnane, J.P. Mechanisms of telomere loss and their consequences for chromosome instability. Front Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Hermida, S.; Bosso, G.; Sánchez-Vázquez, R.; Martínez, P.; Blasco, M.A. Telomerase deficiency and dysfunctional telomeres in the lung tumor microenvironment impair tumor progression in NSCLC mouse models and patient-derived xenografts. Cell Death Differ, 1: online , 2023, 21 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavia-García, G.; Rosado-Pérez, J.; Arista-Ugalde, T.L.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Telomere Length and Oxidative Stress and Its Relation with Metabolic Syndrome Components in the Aging. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupatov AYu, Yarygin, K. N. Telomeres and Telomerase in the Control of Stem Cells. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiello, F.; Jurk, D.; Passos, J.F.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Telomere dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nat Cell Biol 2022, 24, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.H.; Walter, M. Combining old and new concepts in targeting telomerase for cancer therapy: transient, immediate, complete and combinatory attack (TICCA). Cancer Cell International 2023, 23, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatak, P.; Burger, A.M. Telomerase and its potential for therapeutic intervention. Br J Pharmacol 2007, 152, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdun, R.E.; Karlseder, J. Replication and protection of telomeres. Nature 2007, 447, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawole, T.D.; Okundigie, M.I.; Rotimi, S.O.; Okwumabua, O.; Afolabi, I.S. Preadministration of Fermented Sorghum Diet Provides Protection against Hyperglycemia-Induced Oxidative Stress and Suppressed Glucose Utilization in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rats. Front Nutr 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osikoya, I.O.; Afolabi, I.S.; Rotimi, S.O.; Okafor, A.M.J. Anti-hemolytic and anti-inflammatory activities of the methanolic extract of Solenostemon Monostachyus (P.Beauv.) Briq. leaves in 2-butoxyethanol-hemolytic induced rats 2018, 1954:040015. [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, I.S.; Olawole, T.D.; Adams, K.A.; Shopeju, O.A.; Ezeaku, M.C. Anti-inflammatory effects and the molecular pattern of the therapeutic effects of dietary seeds of Adenanthera Pavonina in albino rats. AIP Conference Proceedings 2018, 1954, 040016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, I.; Percio, S.; Naghshineh, E.; et al. Telomere as a Therapeutic Target in Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vitis, M.; Berardinelli, F.; Sgura, A. Telomere Length Maintenance in Cancer: At the Crossroad between Telomerase and Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT). Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Chakrabarti, K. Current Perspectives of Telomerase Structure and Function in Eukaryotes with Emerging Views on Telomerase in Human Parasites. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Medhi, B.; Sehgal, R. Challenges of drug-resistant malaria. Parasite. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, H.; Bhalerao, P.; Singh, S.; et al. Malaria therapeutics: are we close enough? Parasites & Vectors 2023, 16, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.J.; Schiemann, W.P. Telomerase in Cancer: Function, Regulation, and Clinical Translation. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, E.; Charoudeh, H.N.; Sanaat, Z.; Farahzadi, R. Telomere shortening as a hallmark of stem cell senescence. Stem Cell Investigation. [CrossRef]

- Zaug, A.J.; Crary, S.M.; Jesse Fioravanti, M.; Campbell, K.; Cech, T.R. Many disease-associated variants of hTERT retain high telomerase enzymatic activity. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 8969–8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, D.K.; Das, B.R.; Dash, A.P.; Supakar, P.C. Identification of telomerase activity in gametocytes of Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003, 309, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertschi, N.L. Novel insights into telomere biology and virulence gene expression in plasmodium falciparum. Published online 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mender, I.; Gryaznov, S.; Shay, J.W. A novel telomerase substrate precursor rapidly induces telomere dysfunction in telomerase positive cancer cells but not telomerase silent normal cells. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, C.; Blasco, M.A. Telomeres and telomerase as therapeutic targets to prevent and treat age-related diseases. F1000Res, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, L.; Kondrashin, A.V.; Stepanova, E.V.; et al. In vivo effectiveness of the inhibitors of telomerase against malaria parasites. Infekcionnye bolezni, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.S.; Lindner, S.E.; Lopez-Rubio, J.J.; Llinás, M. Cutting back malaria: CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of Plasmodium. Brief Funct Genomics 2019, 18, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudyba, H.M.; Cobb, D.W.; Florentin, A.; Krakowiak, M.; Muralidharan, V. CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing to Make Conditional Mutants of Human Malaria Parasite, P. falciparum. J Vis Exp, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.M.; Baumgarten, S.; Glover, L.; Hutchinson, S.; Rachidi, N. CRISPR in Parasitology: Not Exactly Cut and Dried! Trends in Parasitology 2019, 35, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W. ; Roh J il, Sung, Y.H. Clinical implications of antitelomeric drugs with respect to the nontelomeric functions of telomerase in cancer. OTT, 1: online 13, 20 August 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, C.; Venkataswamy, M.M.; Sibin, M.K.; Srinivas Bharath, M.M.; Chetan, G.K. Down regulation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) expression by BIBR1532 in human glioblastoma LN18 cells. Cytotechnology 2018, 70, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, G.; Degli Uberti, B.; Galiero, G.; et al. The Small Molecule BIBR1532 Exerts Potential Anti-cancer Activities in Preclinical Models of Feline Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Through Inhibition of Telomerase Activity and Down-Regulation of TERT. Front Vet Sci, 6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, H.J.; Readmond, C.; Radicella, C.; Persad, V.; Fasano, T.J.; Wu, C. Binding of Telomestatin, TMPyP4, BSU6037, and BRACO19 to a Telomeric G-Quadruplex–Duplex Hybrid Probed by All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations with Explicit Solvent. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 14788–14806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagah, S.; Tan, I.L.; Radhakrishnan, P.; et al. RHPS4 G-Quadruplex Ligand Induces Anti-Proliferative Effects in Brain Tumor Cells. PLoS One 2014, 9, e86187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidle, S. 5 - Telomeric Quadruplex Ligands II: Polycyclic and Non-fused Ring Compounds. In: Neidle, S.; ed. Therapeutic Applications of Quadruplex Nucleic Acids, 9: Press; 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machireddy, B.; Sullivan, H.J.; Wu, C. Binding of BRACO19 to a Telomeric G-Quadruplex DNA Probed by All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations with Explicit Solvent. Molecules 2019, 24, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, A.; Zou, L. DNA Damage Sensing by the ATM and ATR Kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5, a012716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davé, A.; Pai, C.C.; Durley, S.C.; et al. Homologous recombination repair intermediates promote efficient de novo telomere addition at DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 157. Roh J il, Sung, Y.H.; Lee, H.W. Clinical implications of antitelomeric drugs with respect to the nontelomeric functions of telomerase in cancer. Onco Targets Ther. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.X.; Zhou, P.K. DNA damage response signaling pathways and targets for radiotherapy sensitization in cancer. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; De Palma, R.; Filaci, G. Anti-cancer Immunotherapies Targeting Telomerase. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Li, G.W.; Sui, Y.F.; et al. Immunization with truncated sequence of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase induces a specific antitumor response in vivo. Acta Oncologica 2007, 46, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.S.; Gomes, W.R.; Calado, R.T. Recent advances in understanding telomere diseases. Fac Rev. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, B.M.D.; da Costa Pantoja, L.; da Silva, E.L.; et al. Telomerase (hTERT) Overexpression Reveals a Promising Prognostic Biomarker and Therapeutical Target in Different Clinical Subtypes of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Sharma, R.; Dhamodharan, V.; et al. Investigating Pharmacological Targeting of G-Quadruplexes in the Human Malaria Parasite. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 6691–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquerel, E.; Lormand, J.; Bose, A.; et al. Oxidative guanine base damage regulates human telomerase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2016, 23, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, J.; Cohen, A.; Gueddouda, N.M.; et al. Design, synthesis and antimalarial activity of novel bis{N-[(pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxalin-4-yl)benzyl]-3-aminopropyl}amine derivatives. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2017, 32, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.D.; Pantaleo, A.; Kesely, K.R.; et al. Imatinib augments standard malaria combination therapy without added toxicity. J Exp Med 2021, 218, e20210724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriwilaijareon, N.; Petmitr, S.; Mutirangura, A.; Ponglikitmongkol, M.; Wilairat, P. Stage specificity of Plasmodium falciparum telomerase and its inhibition by berberine. Parasitol Int 2002, 51, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/malaria#tab=tab_1. Accessed April 10, 2024. [Google Scholar]

|

Feature |

Plasmodium telomerase system |

Human telomerase system |

|---|---|---|

|

Telomere repeat sequence |

TTAGGG |

TTAGGG |

|

Telomerase RNA template |

TER1 |

TER1 |

|

Telomerase reverse transcriptase |

TERT |

TERT |

|

Accessory proteins |

TRF2, TPP1 |

TIN2, Pot1 |

|

Regulation |

Unknown |

Complex, regulated by multiple factors, including cell type, differentiation state, and stress |

| Compound | Mechanism of action | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bis{N-[(pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxalin-4-yl)benzyl]-3-aminopropyl}amine derivatives | Disrupts telomere maintenance by Stabilizing Plasmodium | Guillon et al., 2017 | |

| TMPyP4 (5,10,15,20-Tetrakis-(N-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphine) | Inhibition telomerase and parasite growth | [45] | |

| Dideoxy GPT |

Inhibition of telomerase activity and promotes p cell senescence in vitro |

[36] | |

| 17-AAG (Radicicol) | Depletion of Pfsir2 protein,deacetylation of Histone, shields telomerase access to telomeres | [42] | |

| Imatinib |

Inhibition of Plasmodium kinase PfPK5 and dyregulation of parasite cell cycle progression | [144,166] | |

| Berberine |

Inhibition of Telomerase activity in P. falciparum in stage specific manner |

[167] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).