Submitted:

11 April 2024

Posted:

11 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

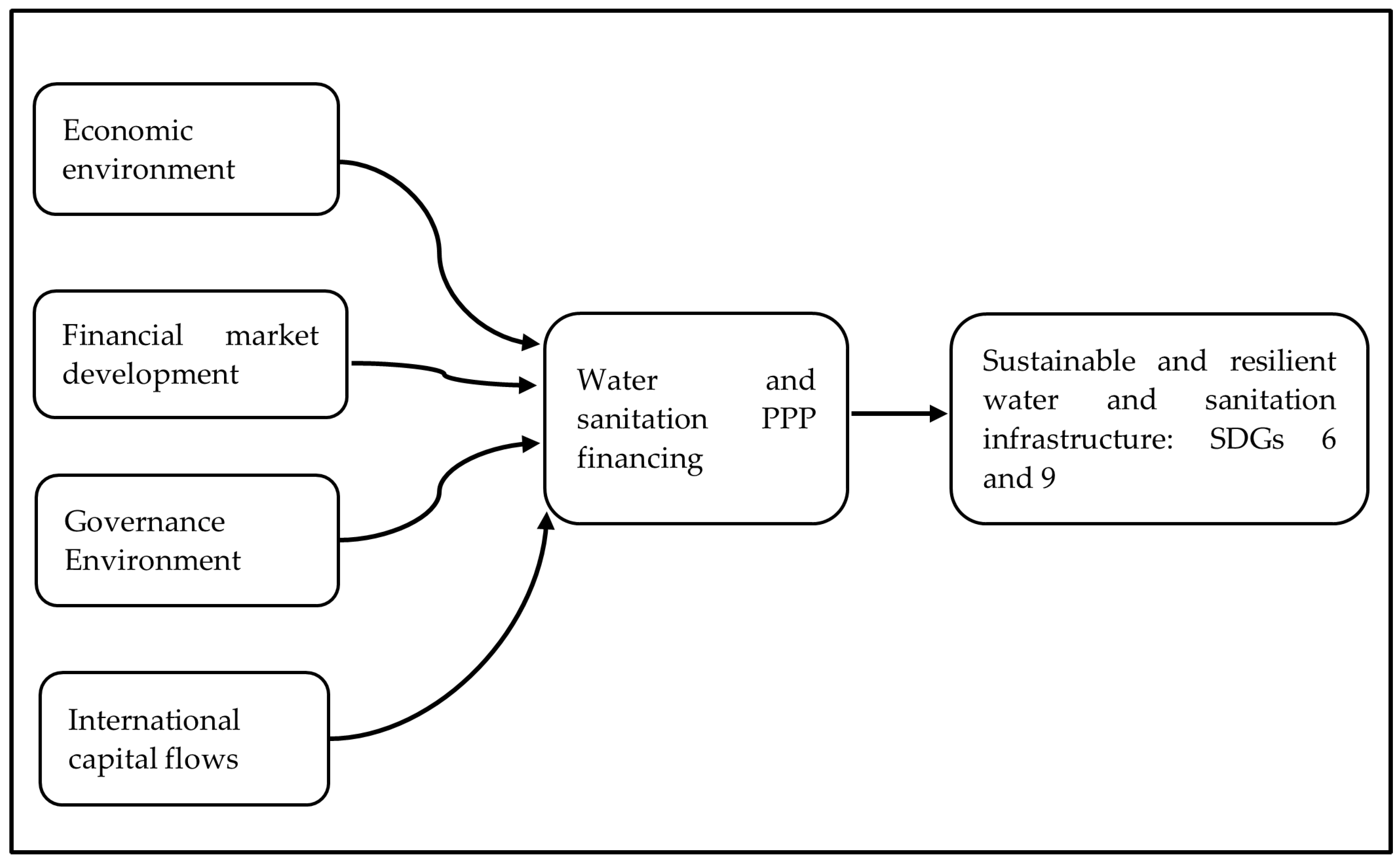

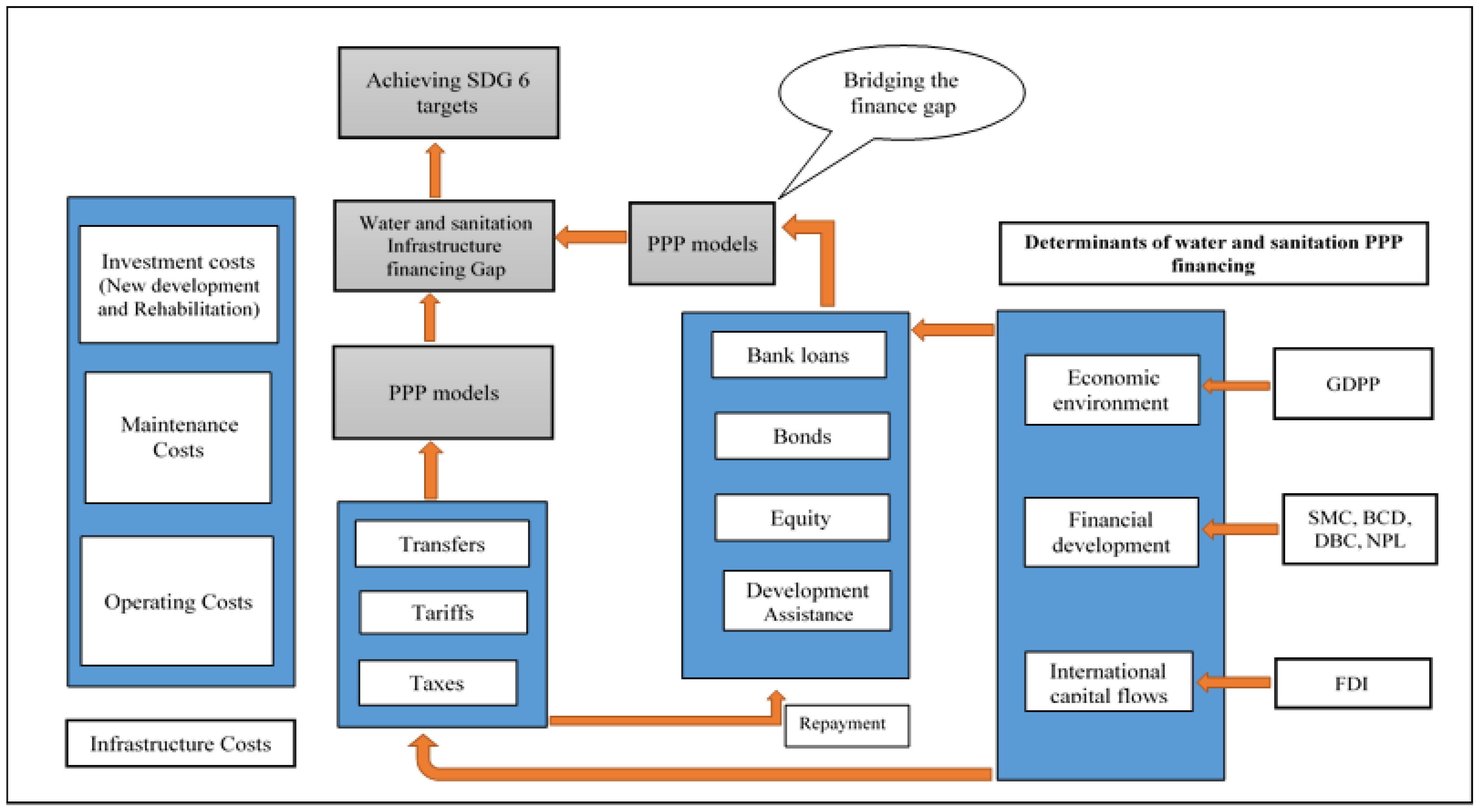

2. Review of Literature: Sources and Drivers of PPP Finance

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion of Findings

5. Framework for Financing Water and Sanitation PPPs.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A.

| Variable | Acronym | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Stock market capitalisation to GDP | SMC | 5,43 |

| Foreign direct investment | logFDI | 4,9 |

| Non-performing loans | NPL | 3,68 |

| Domestic bank credit to GDP | DBC | 3,32 |

| Bank credit to bank deposits | BCD | 3,15 |

| Gross domestic product per capita | logGDPP | 2,82 |

| Political stability | PS | 2,72 |

| Inflation | logIFN | 2,4 |

| Government effectiveness | GE | 2,01 |

| Regulatory quality | RQ | 1,98 |

| Control of corruption | CC | 1,86 |

| Rule of law | RL | 1,85 |

| Voice and accountability | VA | 1,84 |

| International reserves to imports | IRIMP | 1,76 |

| Mean VIF | 2,837 |

| Variable | ADF Statistic | Critical value (1%) | Critical value (5%) | Critical value (10%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔlogPPPUSD | -6.207*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔlogGDPP | -2.796** | -2.528 | -1.725 | -1.325 |

| ΔIRIMP | -6.362*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔlogIFN | -3.673*** | -2.528 | -1.725 | -1.325 |

| ΔlogFDI | -4.163** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔSMC | -4.338** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔDBC | -5.529*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔBCD | -4.616*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔNPL | -2.320** | -2.528 | -1.725 | -1.325 |

| ΔFDX | -5.529*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔGIX | -4.891*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔCC | -1.728** | -2.528 | -1.725 | -1.325 |

| ΔRQ | -4.348*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔRL | -5.807*** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

| ΔVA | -1.834** | -2.528 | -1.725 | -1.325 |

| ΔPS | -3.219*** | -2.528 | -1.725 | -1.325 |

| ΔGE | -4.891** | -4.380 | -3.600 | -3.240 |

References

- Bandauko, E., Bobo, T., and Mandisvika, G., 2018, Towards Smart Urban Transportation System in Harare, Zimbabwe. In Intelligent Transportation and Planning: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice, pp. 962-978. [CrossRef]

- Drabo, D., 2018, From Land Reform to Hyperinflation: The Zimbabwean Experience of 1997-2008 . Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/haljournl/hal-02141818.htm [Accessed: 20 August 2020].

- Adeleke, F., 2019, Illicit financial flows and inequality in Africa: How to reverse the tide in Zimbabwe. South African Journal of International Affairs, vol. 26, no. 3. pp. 367-393. [CrossRef]

- Marevesa, T., 2019, The government of national unity and national healing in Zimbabwe. In National Healing, Integration and Reconciliation in Zimbabwe. 1st edition. Routledge, pp. 55-68. [CrossRef]

- Saungweme, T. and Odhiambo, N. M., 2019, Government debt, government debt service and economic growth nexus in Zambia: a multivariate analysis. Cogent Economics and Finance, vol. 7, no. 1. pp. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Nhapi, I., 2015, Challenges for water supply and sanitation in developing countries: case studies from Zimbabwe. In Understanding and managing urban water in transition, pp. 91-119. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Tendaupenyu, P., Magadza, C.H.D. and Murwira, A., 2017, Changes in landuse/landcover patterns and human population growth in the Lake Chivero catchment, Zimbabwe, Geocarto International, vol. 32, no. 7, pp.797-811. [CrossRef]

- Homerai, F., Mayo, A.W. and Hoko, Z., 2019; Sustainability of Chiredzi town water supply and wastewater management in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 13, no. 1, pp.22-35. [CrossRef]

- Cole, A., Mudhuviwa, S., Maja, T. and Cronin, A., 2021, Lessons Learnt from financing WASH rehabilitation works in small towns in Zimbabwe. Development in Practice, vol. 31, pp.533-547. [CrossRef]

- Fall, M., Marin, P., Locussol, A., and Verspyck, R., 2009, Reforming Urban Water Utilities in Western and Central Africa: Experiences with Public-Private Partnerships Case studies. Available at: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/31d1eb804ba99afa8df8ef1be6561834/WaterPPPvol2.pdf?MOD=AJ PERES (accessed 28 March 2021).

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development 2019, 2019 national budget statement. Harare, Zimbabwe. Available at: http://www.zimtreasury.gov.zw/?page_id=731 (Accessed 25 September 2022).

- Zhao, Z.J., Su, G., and Li, D., 2018, The rise of public-private partnerships in China, Journal of Chinese Governance, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 158. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Schuyler House, R., and Peri, R., 2016, Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in water and sanitation in India: lessons from China. Water Policy, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 153-176. [CrossRef]

- Qian, N., House, S., Wu, A.M. and Wu, X., 2020, Public–private partnerships in the water sector in China: A comparative analysis. International Journal of Water Resources Development, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 631-650. [CrossRef]

- Private participation in infrastructure database. Available at: https://ppi.worldbank.org/en/ppi (Accessed 10 May 2023).

- Chilunjika, A., 2023. Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), road tolling and highway infrastructure investment in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science , vol. 12, no. 3, 575-584. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9801-4803.

- Henn, L., Sloan, K., Charles, M.B. and Douglas, N., 2016, An appraisal framework for evaluating financing approaches for public infrastructure. Public Money & Management, vol. 3, no. 36, pp. 273-280. [CrossRef]

- Tshehla M. F., Mukudu E., 2020. Addressing Constraints for Effective Project Finance for Infrastructure Projects in Emerging Economies–the Case of Zimbabwe. Journal of Construction Business and Management, vol. 4, no. 1. Pp. 48-59. [CrossRef]

- Kapesa, T., Mugano, G. and Fourie, H., 2021, A framework for financing public economic infrastructure in Zimbabwe. Southern African Journal of Accountability and Auditing Research, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Frone, S. and Frone, D.F., 2018, issues of efficiency for public-private partnerships in the water sector. Studies and scientific researches. economics edition, vol. 27, Available at: pdfs.semanticscholar.org (accessed 20 Jan 2022).

- World Bank. 2017, Reducing inequalities in water supply, sanitation, and hygiene in the era of the sustainable development goals: Synthesis report of the WASH poverty diagnostic initiative. World Bank Group: Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/27831/w17075.pdf?sequence=5&isallowed=y (accessed 19 May 2020).

- Möykkynen, H. and Pantelias, A., 2021, Viability gap funding for promoting private infrastructure investment in Africa: Views from stakeholders. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 253-269. [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y., Mashiri, E. and Korera, P., 2021. Transfer Pricing Audit Challenges and Dispute Resolution Effectiveness in Developing Countries with Specific Focus on Zimbabwe. Accounting, Economics, and Law: A Convivium. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K. and Chiofalo, E., 2016, Official development finance for infrastructure: with a special focus on multilateral development banks. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P., Dahab, M., Tanabe, M., Murphy, A., Ettema, L., Guy, S. and Roberts, B., 2016. Tracking official development assistance for reproductive health in conflict-affected countries: 2002—2011. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, vol. 123, no. 10, pp. 1693-1704. [CrossRef]

- Kolker, J.E., Trémolet, S., Winpenny, J. and Cardone, R. 2016. Financing options for the 2030 water agenda. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/25495 (accessed 19 May 2021).

- Kitano, N. and Harada, Y., 2016, Estimating China’s foreign aid 2001–2013, Journal of International Development, vol. 28, no. 7, pp.1050-1074. [CrossRef]

- Alaerts, G.J. 2018. Financing for water – Water for financing: A global review of policy and practice. Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 3, pp.821-846. [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S., Udenigwe, O. and Yeboah, H., 2019, Development aid and access to water and sanitation in sub-Saharan Africa. In Better Spending for Localizing Global Sustainable Development Goals, pp. 167-185. [CrossRef]

- Osano, H.M. and Koine, P.W., 2016, Role of foreign direct investment on technology transfer and economic growth in Kenya: a case of the energy sector, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Ghebrihiwet, N. and Motchenkova, E., 2017, Relationship between FDI, foreign ownership restrictions, and technology transfer in the resources sector: A derivation approach. Resources Policy, vol. 52, no. 1. pp. 320-326. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, C., Parker, D. and Zhang, Y.F., 2006, An empirical analysis of state and private-sector provision of water services in Africa. The World Bank Economic Review, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 143-163. [CrossRef]

- Nag, T., Kettunen, J. and Sorsa, K., Exploring Private Participation in Indian Water Sector: Issues and Options. Sustainable Engagement in the Indian and Finnish Business, no. 119. Available at: isbn9789522167040.pdf (theseus.fi) (accessed 20 May 2021).

- Jackline, A., 2021, Public water and waste management in Uganda: the legal framework, obstacles and challenges. KAS African Law Study Library, vol. 7, no. 4, 642-652; Available at: 2363-6262-2020-4-642.pdf (nomos-elibrary.de) (accessed 15 Jan 2021).

- Rao V., 2018, An Empirical Analysis of the Factors that Influence Infrastructure Project Financing by Banks in Select Asian Economies. ADBI No 554. Available from: https://www.think-asia.org/bitstream/handle/11540/8651/ewp-554-project-financing-infrastructure-ppp-projects.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed: 11 August 2021).

- Linh, N. N., Wan, X. and Thuy, H. T., 2018, Financing a PPP Project: Sources and Financial Instruments—Case Study from China. International Journal of Business and Management, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 240-248. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z., Peña-Mora, F., Wang, S.Q., Liu, T. and Wu, D., 2019, Assessment framework for financing public–private partnership infrastructure projects through asset-backed securitization. Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 35, no. 6. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, J.M., Rangel, T., de los Ángeles BAEZA, M., and Bueno, P.C., 2018, The Europe 2020 Project Bond Initiative: an alternative to finance infrastructure in Europe. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 229-252. [CrossRef]

- WB (World Bank). 2011, Zimbabwe`s Infrastructure a continental perspective. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/27258/647390WP0P12420e0country0report0Web.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed: 02 February 2021].

- Srivastava, V., 2017, Project finance bank loans and PPP funding in India: A risk management perspective. Journal of Banking Regulation, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 14-27. [CrossRef]

- Inderst, G., 2016. Infrastructure investment, private finance, and institutional investors: Asia from a global perspective.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2015. Infrastructure financing instruments and incentives. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/Infrastructure-Financing-Instruments-and-Incentives.pdf [Accessed 15 October 2022].

- Lara-Galera, A., Sánchez-Soliño, A. and Gómez-Linacero, M., 2017. Analysis of infrastructure funds as an alternative tool for the financing of public-private partnerships. Revista de la Construcción. Journal of Construction, vol 16, no. 3, pp.403-411. [CrossRef]

- Oji, C.K., 2015. Bonds: A Viable Alternative for Financing Africa’s Development. Available at: https://africaportal.org/publication/bonds-a-viable-alternative-for-financing-africas-development/ (Accessed 20 June 2023).

- Vecchi, V., Casalini, F., Cusumano, N., Leone, V.M. 2021. Private Investments for Infrastructure. In: Public Private Partnerships. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Musah, A., Badu-Acquah, B. and Adjei, E., 2019, Factors that influence bond markets development in Ghana. Jurnal Perspektif Pembiayaan dan Pembangunan Daerah, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 461-476. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S., Park, D., and Tian, G., 2018. Determinants of Public–Private Partnerships in Infrastructure in Asia: Implications for Capital Market Development. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, 552. [CrossRef]

- Jensen O., Blanc-Brude F., 2006, The handshake: why do governments and firms sign private sector participation deals? Evidence from the water and sanitation sector in developing countries. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (3937). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=923244#:~:text=Jensen%2C%20Olivia%20and,com/abstract%3D923244 (Accessed 15 Aug 2022).

- IMF (International Monetary Fund) 2006, Determinants of public-private partnerships in infrastructure. Available at: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2006/099/001.2006.issue-099-en.xml (Accessed: 20 October 2022).

- Sharma C., 2011), Determinants of PPP in infrastructure in developing economies. Transforming government: people, process and policy, vol. 6, no. 2, 149-166. [CrossRef]

- Ba, L., Gasmi, F. and Noumba, P., 2010, Is the level of financial sector development a key determinant of private investment in the power sector?. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (5373). https://ssrn.com/abstract=1647517.

- Ba, L., Gasmi, F. and Um, P.N., 2017, The relationship between financial development and private investment commitments in energy projects. Journal of Economic Development, vol. 42, no.3, pp. 17-40. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O. and Blanc-Brude, F., 2005, October. The institutional determinants of private sector participation in the water and sanitation sector in developing countries. In 4th Conference on Applied Infrastructure Research. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228775879_The_Institutional_Determinants_of_Private_Sector_Participation_in_the_Water_and_Sanitation_Sector_in_Developing_Countries.

- Banerjee, S.G., Oetzel, J.M. and Ranganathan, R., 2006, Private provision of infrastructure in emerging markets: do institutions matter?. Development Policy Review, vol.24, no.2, pp.175-202. [CrossRef]

- Fleta-Asín, J. and Muñoz, F., 2021; Renewable energy public–private partnerships in developing countries: Determinants of private investment. Sustainable Development, vol. 29, no.4; pp.653-670. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H. and Sunouchi, Y., 2019, The role of institutions in private participation in infrastructure in low-and middle-income countries: Greenfield versus brownfield projects, Economics Bulletin, vol. 39, no. 3, pp.2027-2039; Available at: MPRA_paper_93555.pdf (uni-muenchen.de) (accessed 20 Aug 2022).

- Panayides, P.M., Parola, F. and Lam, J.S.L., 2015. The effect of institutional factors on public–private partnership success in ports. Transportation research part A: policy and practice, vol. 71, pp.110-127. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D., Chen, H., Zhou, G. and Kong, F., 2020, Determinants of public-private partnership adoption in solid waste management in rural China, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 15, pp. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., 2019, Determinants of Public Private Partnerships in Infrastructure: A Study of Developing Countries. Journal of Commerce and Accounting Research, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 79-85.

- Kasri, R. A., and Wibowo, F. A., 2015, Determinants of Public Private Partnerships in Infrastructure provision: Evidence from Muslim developing countries. Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 1-34.

- Marozva, G. and Makoni, P.L., 2018, Foreign direct investment, infrastructure development and economic growth in African economies, Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, vol.14, no. 6.

- Chikaza, Z. and Simatele, M., 2021, Private financing for infrastructural development: a search for determinants in public–private partnerships in SSA. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 170-188.

- Telang, V. and Prakash, S., 2015, Financing of public private partnerships in India (sources, problems and challenges). Research front, vol. 3, no. 1, 49-62.

- Kamau P., 2016, Commercial Banks and Economic Infrastructure PPP Projects in Kenya: Experience and Prospects. KBA Centre for Research on Financial Markets and Policy Working Papers Series WPS/01, 16. Available from https://www.kba.co.ke/downloads/Working%20Paper%20WPS-01-16.pdf (Accessed: 11 August 2021).

- Banerjee, S. G., Rondinelli, D. A. and Koo, J. 2003. Decentralisation’s Impact on Private Participation in Infrastructure in Developing Countries. Working Paper. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina. [CrossRef]

- Sahni, H., Nsiah, C. and Fayissa, B., 2021. Institutional quality, infrastructure, and economic growth in Africa. Journal of African Development, vol. 22, no. 1, pp.7-37. [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo I. S., 2020. International capital inflows in emerging markets: the role of institutions. (Masters’ dissertation). University of South Africa. Available at: dissertation_nxumalo_is.pdf (unisa.ac.za).

- Nxumalo, I.S., and Makoni, P.L., 2021, Analysis of International Capital Inflows and Institutional Quality in Emerging Markets. Economies, vol. 9, no. 4, pp.179. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C., 2008. Introductory Econometrics for finance, Cambridge University.

- Mundonde, J. and Makoni, P.L., 2023. Public private partnerships and water and sanitation infrastructure development in Zimbabwe: what determines financing?. Environmental Systems Research, vol. no.1, pp. 14. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M., 1989. A computationally simple heteroskedasticity and serial correlation robust standard error for the linear regression model. Economics letters, vol. 31. No. 33, pp.239-243. [CrossRef]

- Nakatani R., 2017, Structural vulnerability and resilience to currency crisis: Foreign currency debt versus export, The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 132-143. [CrossRef]

- Kavila, W. and Le Roux, P., 2016, Inflation dynamics in a dollarised economy, The case of Zimbabwe, Southern African Business Review, vol. 20, no. 1, pp.94-117.

- Chan, A.P., Lam, P.T., Wen, Y., Ameyaw, E.E., Wang, S. and Ke, Y., 2015, Cross-sectional analysis of critical risk factors for PPP water projects in China. Journal of Infrastructure Systems. vol.24, no.1, pp. 401-403. [CrossRef]

- Maposa, L. and Munanga, Y., 2021, Public-private partnerships development finance model in Zimbabwe infrastructure projects, Open Access Library Journal, vol. 8, no. 4, pp.1-24. [CrossRef]

- RBZ (Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe) 2020, Monetary policy statement. Available at: https://www.rbz.co.zw/index.php/monetary-policy/monetary-policy-statements (Accessed: 18 November 2022).

- Chitongo L., 2017, Public private partnerships and housing provision in Zimbabwe: The case of Runyararo South West housing scheme (Mbudzi) Masvingo. European Journal of Research in Social Sciences , vol. 5, pp. 17-29. http://localhost:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/295.

- Goksu, A., Trémolet, S., Kolker, J.E., 2017. Easing the transition to commercial financing for sustainable water and sanitation. Available at: Easing the Transition to Commercial Finance for Sustainable Water and Sanitation (oecd.org) (accessed 04 April 2023).

- Rozenberg, J. and Fay, M. eds., 2019, Beyond the gap: How countries can afford the infrastructure they need while protecting the planet. World Bank Publications. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/189471550755819133/Beyond-the-Gap-How-Countries-Can-Afford-the-Infrastructure-They-Need-while-Protecting-the-Planet (Accessed 18 November 2022).

- AfDB (African development bank). 2019, Zimbabwe Infrastructure report. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and Operations/Zimbabwe_Infrastructure_Report_2019_-_AfDB.pdf.

- Humphreys, E., van der Kerk, A. and Fonseca, C., 2018. Public finance for water infrastructure development and its practical challenges for small towns. Water Policy, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 100-111. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Indicator | Data source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDPP | GDP per capita | World Bank WDI database | [35,48,49] |

| IRIMP | International reserves to imports ratio | World Bank WDI database | [49,50,59] |

| INF | Consumer price index | World Bank WDI database, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe | [35,49,50,60] |

| FDI | Net FDI to GDP (%) | World Bank WDI database | [61,62] |

| SMC | Stock market capitalisation to GDP (%) | World Bank WDI database | [51,52] |

| DBC | Domestic bank credit to GDP (%) | World Bank WDI database | [51,52] |

| BCD | Bank credit to bank deposits (%) | Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe | [58] |

| NPL | Non-performing loans to bank assets (%) | Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe | [35,63,64] |

| CC | Control of corruption percentile rank | World Bank WGI database | [48,53,65,67] |

| RQ | Regulatory quality percentile rank | World Bank WGI database | [56,65,66,67] |

| RL | Rule of law percentile rank | World Bank WGI database | [48,53,67,68] |

| VA | Voice and accountability percentile rank | World Bank WGI database | [55,56,65,67,68] |

| PS | Political stability percentile rank | World Bank WGI database | [48,65,66,68] |

| GE | Government effectiveness percentile rank | World Bank WGI database | [48,56,65,67,68] |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔlogGDPP | -2.0335* | -2.3409* | -0.9765 | -0.4760 | -1.5471 | -2.1273** | -0.7663 |

| (1.1927) | (-1.866) | (1.573) | (2.2012) | (1.2456) | (1.0908) | (1.6072) | |

| ΔIRIMP | -0.0181 | -0.0043 | -0.1268 | -0.1890 | -0.0222 | -0.0194 | -0.1302 |

| (0.1200) | (-0.0422) | (0.162) | (0.2255) | (0.1180) | (0.1217) | (0.1617) | |

| ΔlogIFN | -0.0368 | -0.0266 | -0.061 | -0.0456 | -0.0795 | -0.0152 | -0.0746 |

| (0.1039) | (-0.2514) | (0.110) | (0.1006) | (0.1273) | (0.1109) | (0.1187) | |

| ΔlogFDI | -0.391*** | -0.389*** | -0.395** | -0.3037** | -0.433*** | -0.3579** | -0.363*** |

| (0.1351) | (-2.7217) | (0.122) | (0.1523) | (0.1260) | (0.1587) | (0.1291) | |

| ΔSMC | 0.0083*** | 0.0087*** | 0.0071** | 0.0071*** | 0.0076*** | 0.0083*** | 0.0069*** |

| (0.0018) | (3.7934) | (0.002) | (0.00239) | (0.0020) | (0.0018) | (0.0022) | |

| ΔDBC | -0.020*** | -0.019*** | -0.02*** | -0.022*** | -0.019*** | -0.020*** | -0.0181** |

| (0.0066) | (-3.2793) | (0.006) | (0.0066) | (0.0064) | (0.0076) | (0.0073) | |

| ΔBCD | 0.0234*** | 0.0238*** | 0.023*** | 0.0231*** | 0.0246*** | 0.0218*** | 0.0244*** |

| (0.0073) | (3.0830) | (0.006) | (.006071) | (0.0074) | (0.0069) | (0.0071) | |

| ΔNPL | -0.068*** | -0.061*** | -0.09*** | -0.087*** | -0.084*** | -0.064*** | -0.076*** |

| (0.0158) | (-3.0704) | (0.023) | (0.0241) | (0.0253) | (0.0193) | (0.0180) | |

| ΔCC | 0.0178 | ||||||

| (0.5068) | |||||||

| ΔRQ | -0.068 | ||||||

| (0.049) | |||||||

| ΔRL | -0.06097 | ||||||

| (0.0586) | |||||||

| ΔVA | -0.0539 | ||||||

| (0.0595) | |||||||

| ΔPS | 0.0127 | ||||||

| (0.0366) | |||||||

| ΔGE | -0.04758 | ||||||

| (0.0344) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).