Submitted:

29 March 2024

Posted:

01 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

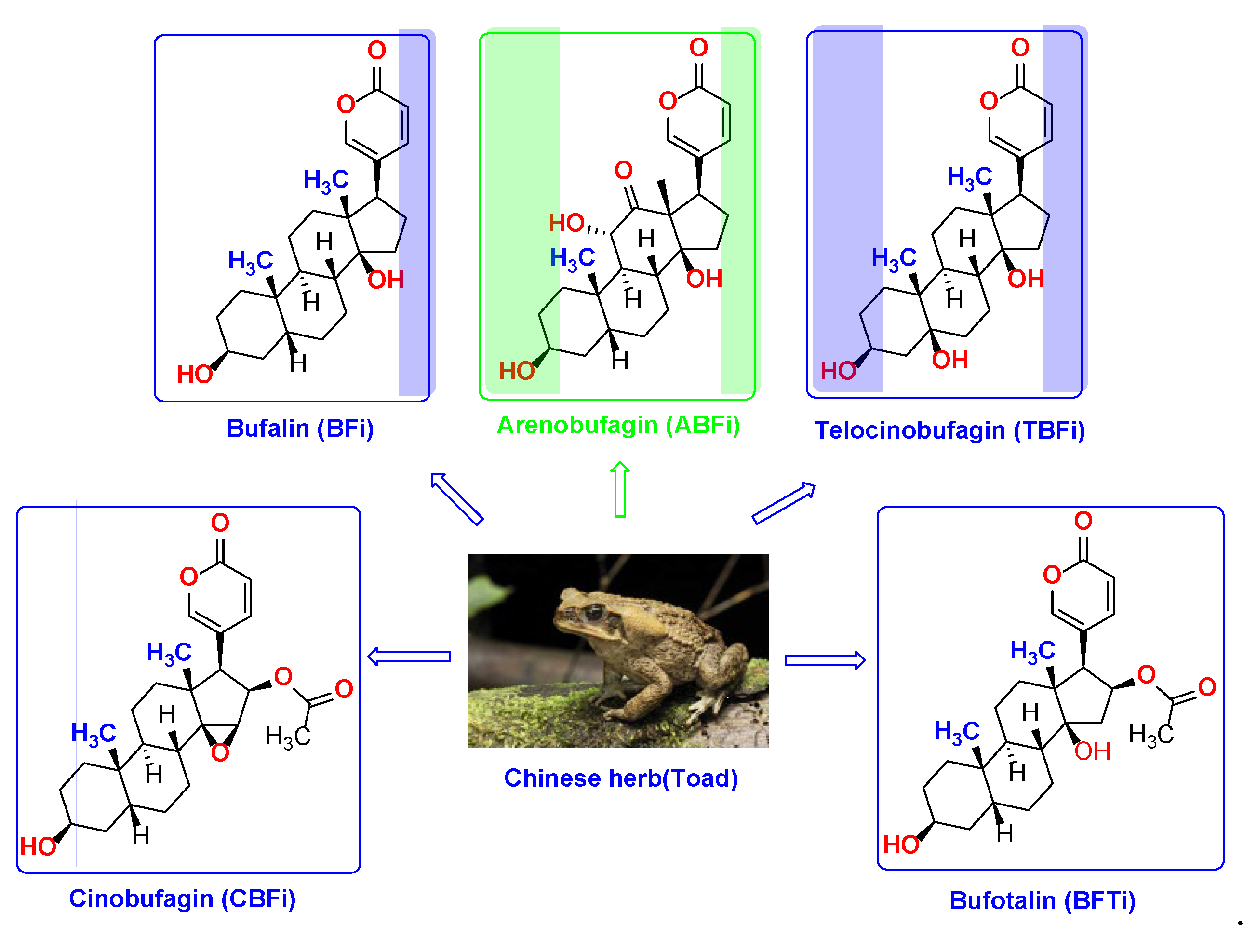

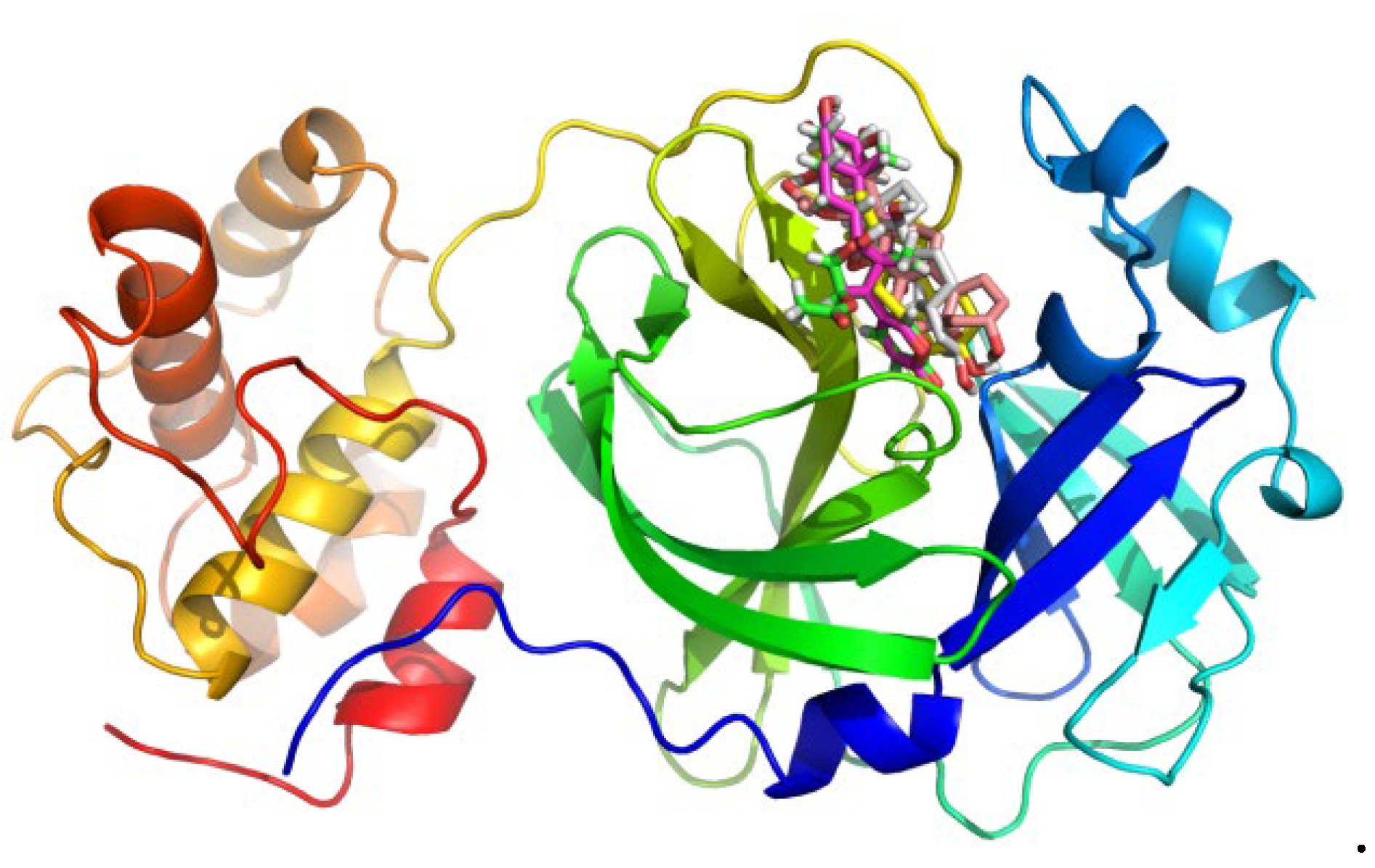

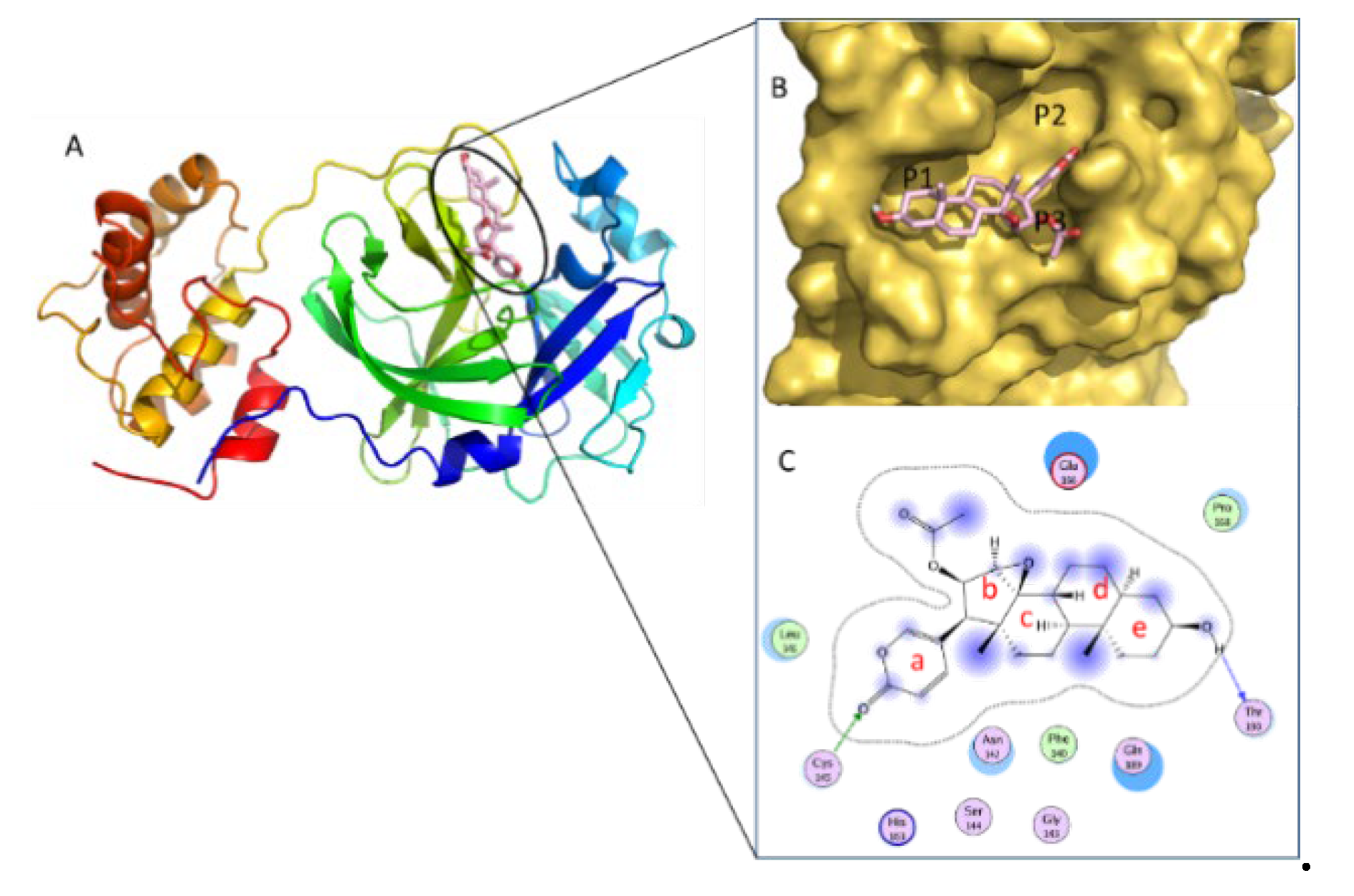

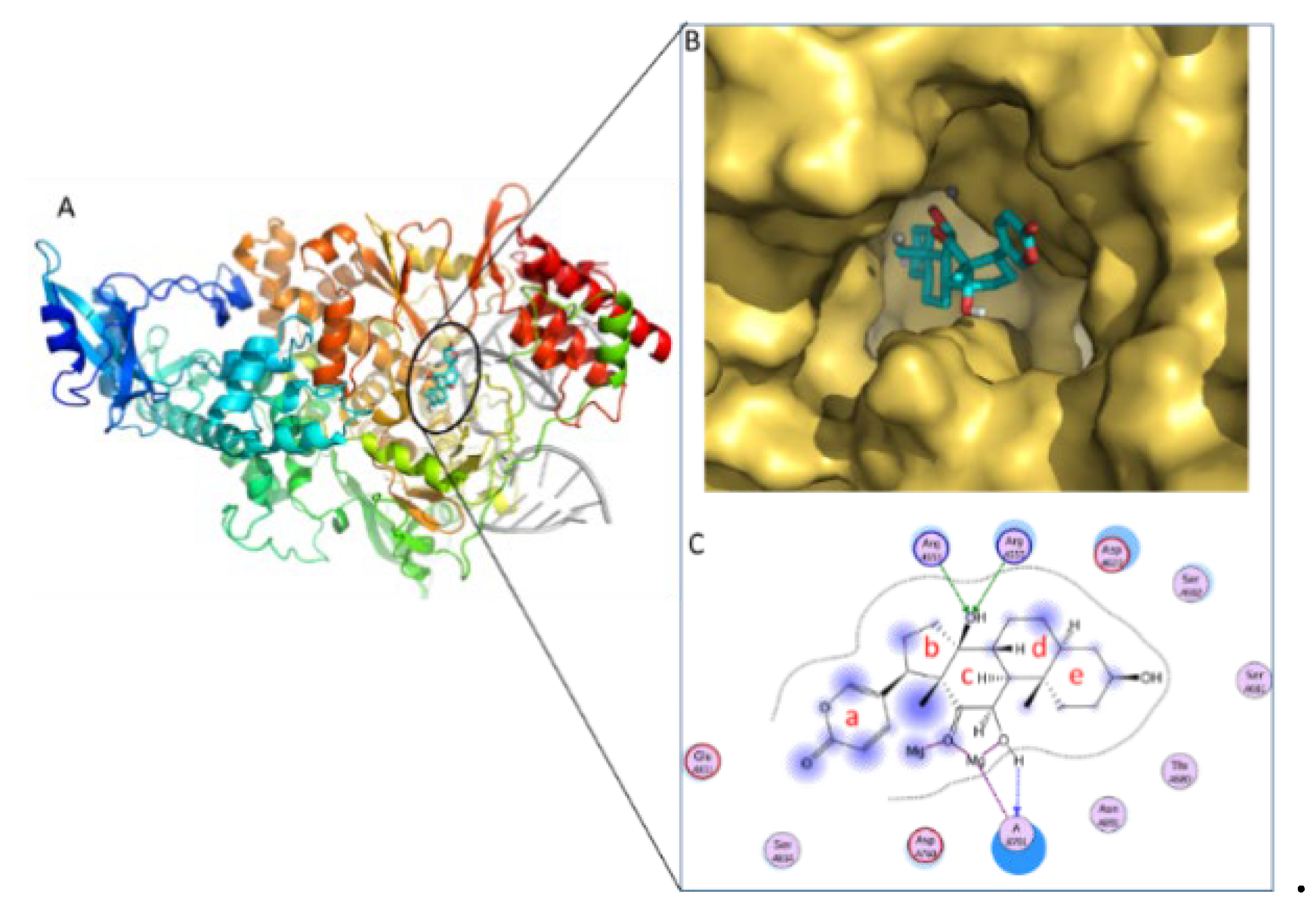

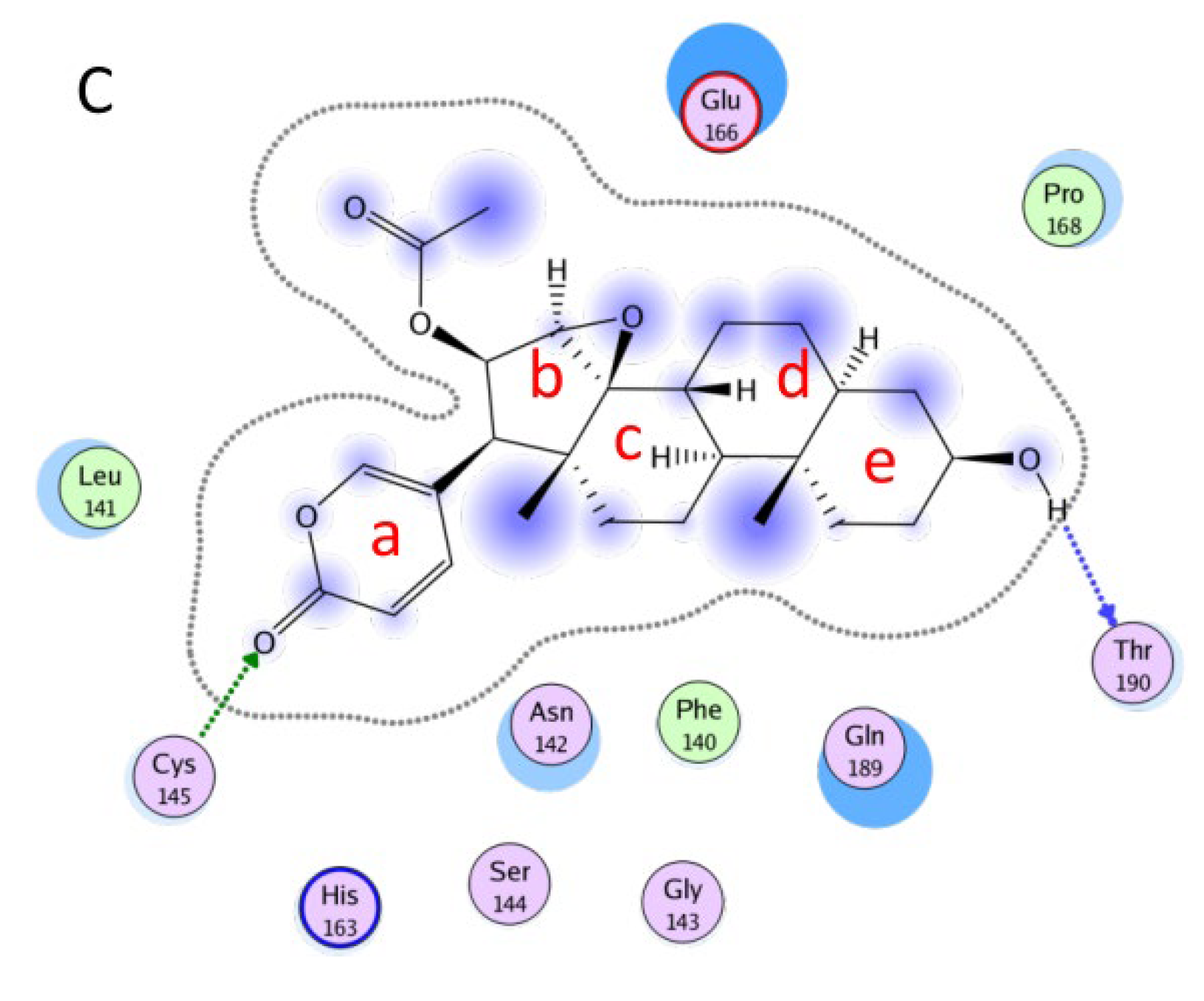

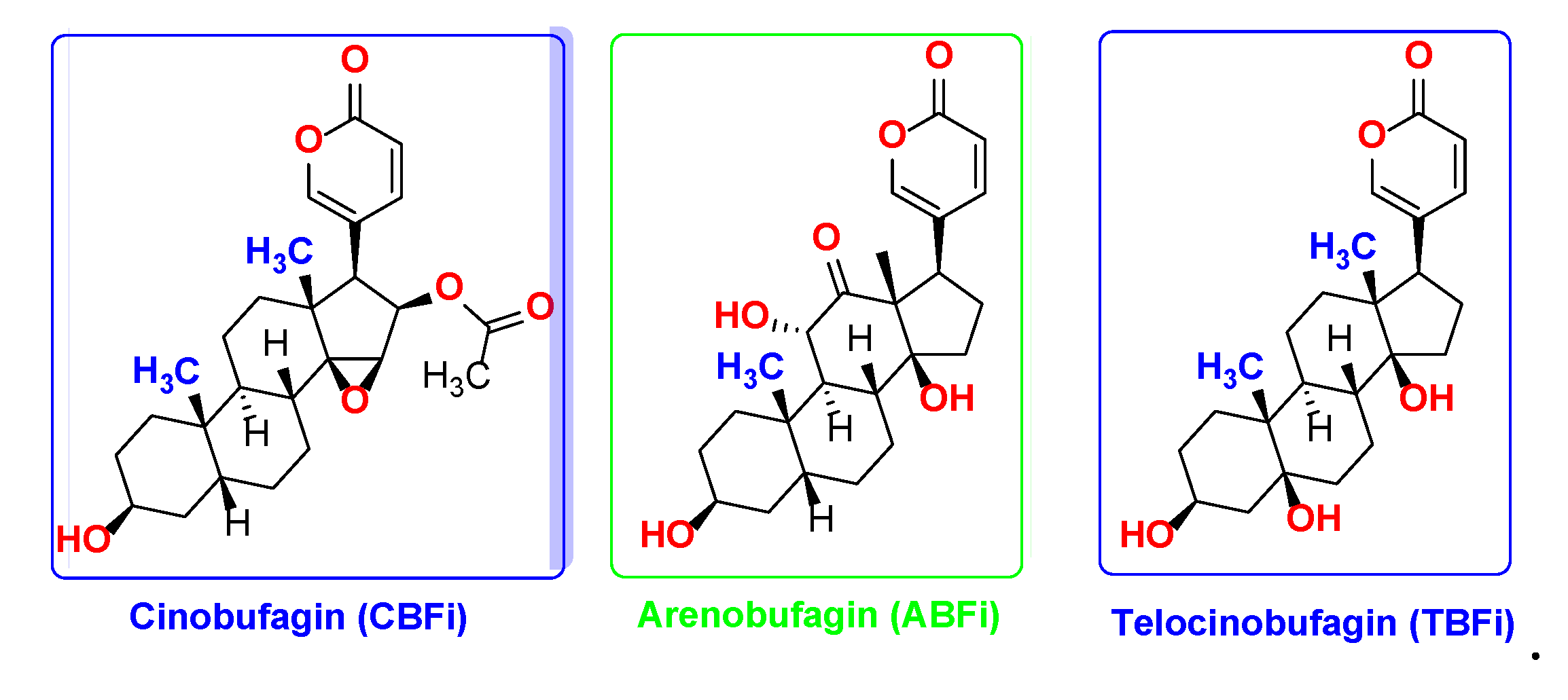

2.1 Molecular Docking Results of Compounds with 3CL

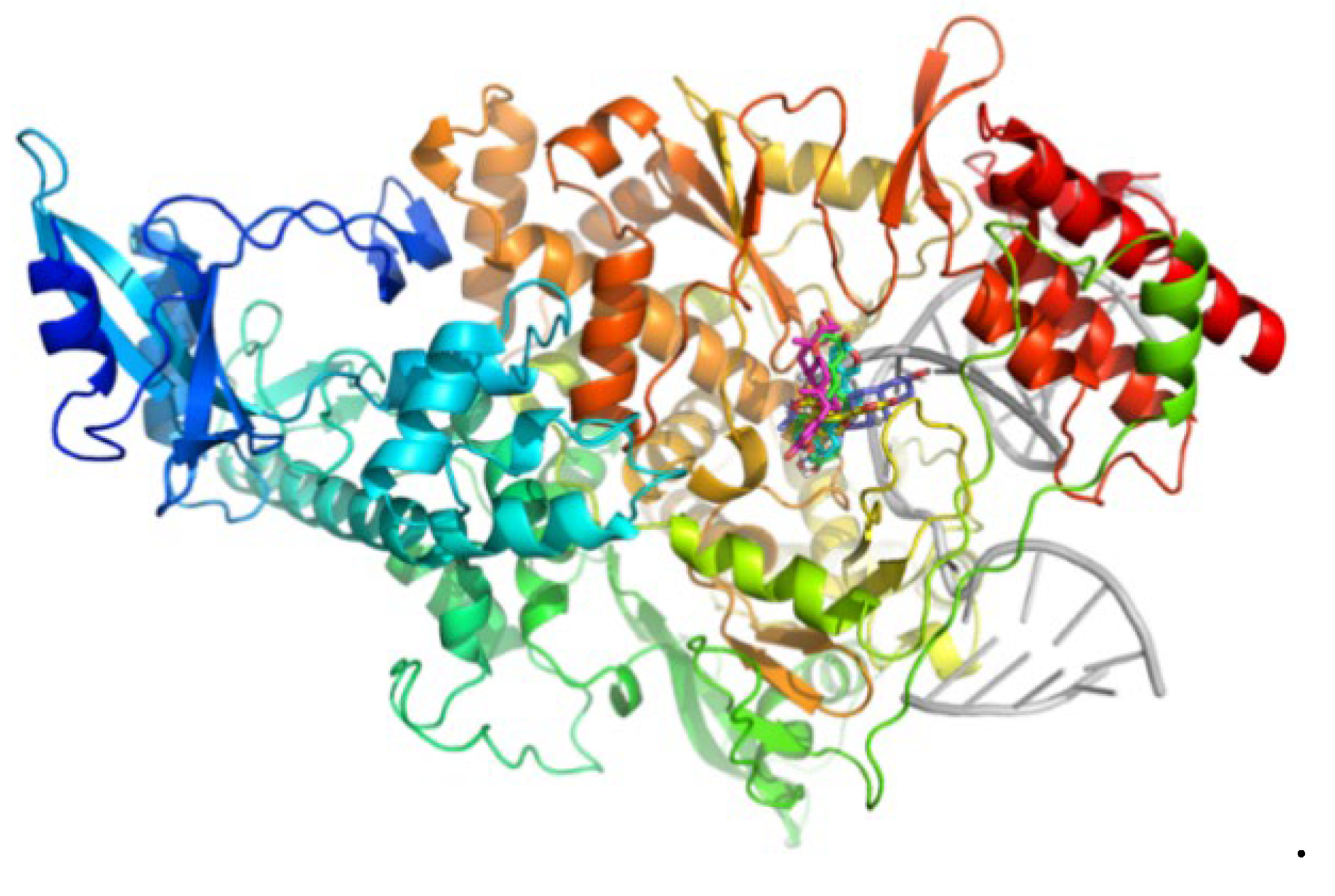

2.2 Molecular Docking Results of Compounds with RdRp

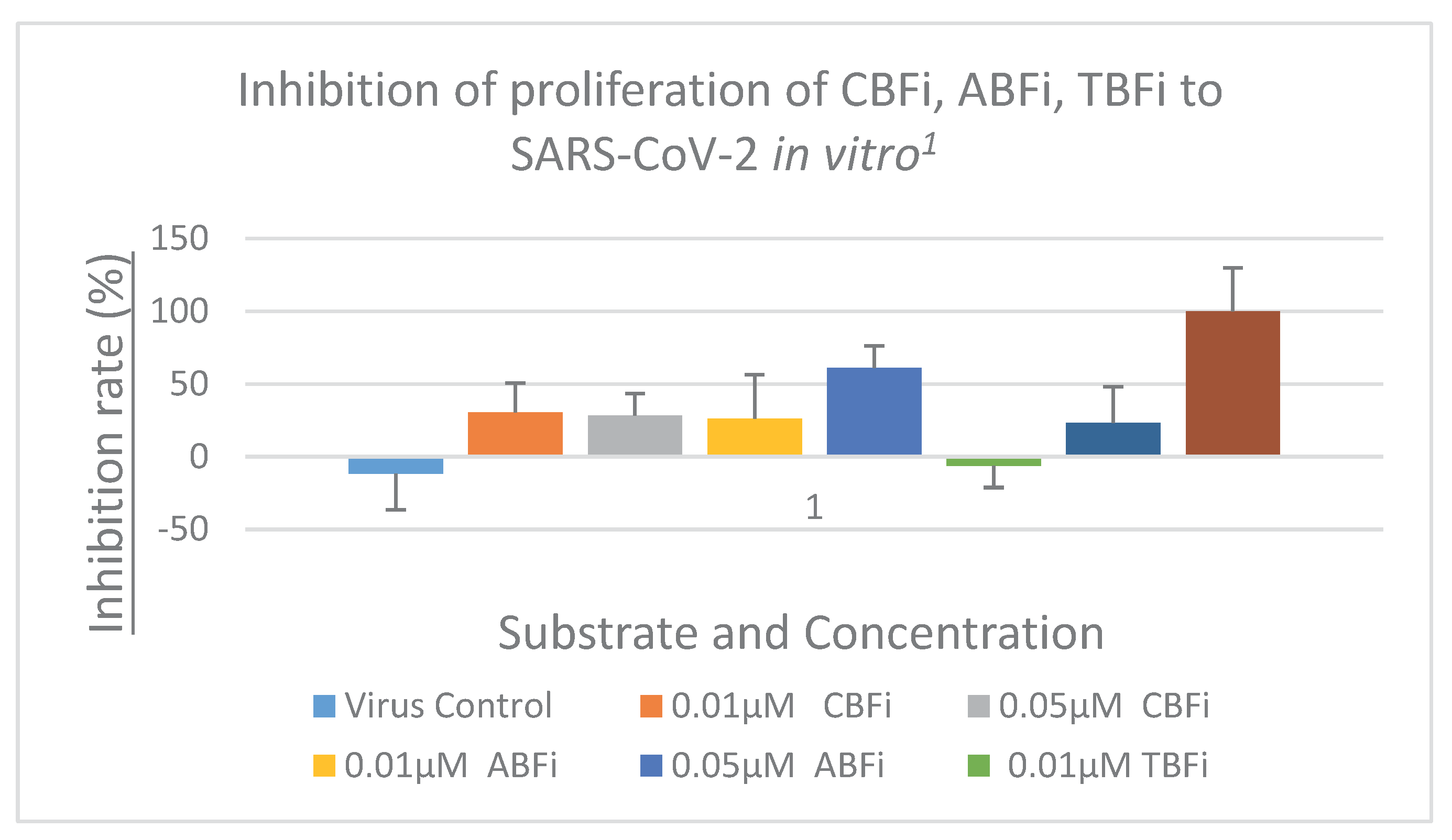

2.3 In Vitro Proliferation Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2

2.4 Results of Cytotoxicity assay of Compounds on MDCK Cells

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwong, C.H.; Mu, J.; Li, S.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Kam, H.; Lee, S.M.; Chen, Y.; Deng, F.; Zhou, X. Reviving chloroquine for anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatment with cucurbit [7] uril-based supramolecular formulation. , Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 3019–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y. Traditional Chinese medicine treatment of COVID-19. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 2020, 39, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L. , Tu Y., Li J., Zhang W., Wang Z., Zhuang C., Xue L. Structure-based optimizations of a necroptosis inhibitor (SZM594) as novel protective agents of acute lung injury. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2545–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. , Li Y., Zhou L., Zhou X., Xie B., Zhang W., Sun J. Prevention and treatment of COVID-19 using Traditional Chinese Medicine: A review. Phytomedicine. 2021, 85, 153308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.C. , Zhang H.X., Zhang Z., Rinkiko S., Cui Y.M., Zhu Y.Z. The two-way switch role of ACE2 in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia and underlying comorbidities. Molecules. 2020, 26, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. , Qi F. Traditional Chinese medicine to treat COVID-19: the importance of evidence-based research. Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 2020, 14, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.R. , Li T.N., Ren Y.Y., Zeng Y.J., Lv H.Y., Wang J., Huang Q.W. The important role of volatile components from a traditional Chinese medicine Dayuan-Yin against the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Pharmacol. 2020; 11, 583651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T. , Roy R. Studying traditional Chinese medicine. Science. 2003, 300, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y. , Dong Y., Guo Q., Wang H., Feng M., Yan Z., Bai D. Study on supramolecules in traditional Chinese medicine decoction. Molecules. 2022, 27, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L. , Yu J., Zhou Y., Shen M., Sun L. Becoming a faithful defender: traditional Chinese medicine against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Am. J. Chinese. Med. 2020, 48, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, D. , Shi Y., Zhang X., Lv G.. Chinese medicine treatment of mastitis in COVID-19 patients: a protocol for systematic review. Medicine. 2020, 99, e21656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L. , Qi Y., Luzzatto-Fegiz P., Cui Y., Zhu Y. COVID-19: effects of environmental conditions on the propagation of respiratory droplets. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 7744–7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lem, F.F. , Opook F., Lee D.J., Chee F.T., Lawson F.P., Chin S.N. Molecular mechanism of action of repurposed drugs and traditional Chinese medicine used for the treatment of patients infected with COVID-19: a systematic scoping review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 585331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, T.Q. , Kim J.A., Woo M.H., Min B.S.. SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibition by compounds isolated from Luffa cylindrica using molecular docking. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 40, 127972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana de Oliveira, M. , da Cruz J.N., Almeida da Costa W., Silva S.G., Brito M.D., de Menezes S.A., de Jesus Chaves Neto A.M., de Aguiar Andrade E.H., de Carvalho Junior R.N.. Chemical composition, antimicrobial properties of Siparuna guianensis essential oil and a molecular docking and dynamics molecular study of its major chemical constituent. Molecules. 2020, 25, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramenko, N. , Vellieux F., Tesařová P., Kejík Z., Kaplánek R., Lacina L., Dvořánková B., Rösel D., Brábek J., Tesař A., Jakubek M.. Estrogen receptor modulators in viral infections such as SARS− CoV− 2: therapeutic consequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabnis, R.W. . Novel Compounds for Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Viral Replication and Treating COVID-19. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1887–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H. , Fan X., Miyata T., Zhang L., Cui Y., Liu Z., Wu X.. Advances in molecular mechanisms for traditional Chinese medicine actions in regulating tumor immune responses. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 534742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , Lin S., Niu C., Xiao Q.. Clinical evaluation of Shufeng Jiedu Capsules combined with umifenovir (Arbidol) in the treatment of common-type COVID-19: a retrospective study. Expert. Rev. Resp. Med. 2021, 15, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavinson, V. , Linkova N., Dyatlova A., Kuznik B., Umnov R.. Peptides: Prospects for Use in the Treatment of COVID-19. Molecules. 2020, 25, 4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.F. , Li Z., Zhang S.H., Wu C.X., Wang C., Wang Z.. Determination of strychnine and brucine in traditional Chinese medicine preparations by capillary zone electrophoresis with micelle to solvent stacking. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2011, 22, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.W. , Wang L., Bao L.D.. Exploring the active compounds of traditional Mongolian medicine in intervention of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) based on molecular docking method. J. Funct. Foods. 2020, 71, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S. , Shah J.A., Arshad M., Halim S.A., Khan A., Shaikh A.J., Riaz N., Khan A.J., Arfan M., Shahid M., Pervez A.. Photocatalytic decolorization and biocidal applications of nonmetal doped TiO2: Isotherm, kinetic modeling and In Silico molecular docking studies. Molecules. 2020, 25, 4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. , Lin H., Wang Q., Cui L., Luo H., Luo L.. Chemical composition and pharmacological mechanism of shenfu decoction in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). Drug. Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2020, 46, 1947–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, S. , Li Y., Yue L., Gong Y., Qian L., Liang T., Ye Y.A.. Role of traditional Chinese medicine in the management of viral pneumonia. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 582322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. , Zhu D., Li J., Ren L., Pu R., Yang G.. Online dental teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional online survey from China. BMC Oral Health, 2021; 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. , Islam M.S., Wang J., Li Y., Chen X.. Traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of patients infected with 2019-new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): a review and perspective. Int. J. Boil. Sci. 2020, 16, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.L. , Gao M.Z., Gao D.M., Guo Y.H., Gao Z., Gao X.J., Wang J.Q., Qiao M.Q.. Tubeimoside-1: A review of its antitumor effects, pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and targeting preparations. Front. Pharmacol, 9412; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S. , Wang F., Yao H., Kou S., Li W., Chen B., Wu Y., Wang X., Pei C., Huang D., Wang Y.. Oral Chinese herbal medicine on immune responses during coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 685734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.Y. , Sun Y.L., Li X.M.. The role of Chinese medicine in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2153–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S. , Pan J., Dai D., Dai Z., Yang M., Yi C.. Design of portable electrochemiluminescence sensing systems for point-of-care-testing applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H. , Kim W., Jung Y.K., Yang J.M., Jang J.Y., Kweon Y.O., Cho Y.K., Kim Y.J., Hong G.Y., Kim D.J., Um S.H.. Efficacy and safety of besifovir dipivoxil maleate compared with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. H. 2019, 17, 1850–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T. , Zhang Y., Zhang X., Chen L., Zheng M., Zhang J., Brust P., Deuther-Conrad W, Huang Y, Jia H. Synthesis and characterization of the two enantiomers of a chiral sigma-1 receptor radioligand:(S)-(+)-and (R)-(-)-[18F] FBFP. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3543–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K. , Yang Y., Wang T., Zhao D., Jiang Y., Jin R., Zheng Y., Xu B., Xie Z., Lin L., Shang Y.. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: experts’ consensus statement. World. J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. , Hu Y., Fang G., Yang G., Xu Z., Dou L., Chen Z., Fan G.. Recent developments in the field of the determination of constituents of TCMs in body fluids of animals and human. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2014, 87, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.J. , Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui D.S., Du B.. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S. , Sun Q., Zhao X., Shen L., Zhen X.. Prevalence and risk factors for antibiotic utilization in Chinese children. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucia, M. , Wietrak E., Szymczak M., Kowalczyk P.. Effect of ligilactobacillus salivarius and other natural components against anaerobic periodontal bacteria. Molecules. 2020, 25, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedyaningsih, E.R. , Isfandari S., Setiawaty V., Rifati L., Harun S., Purba W., Imari S., Giriputra S., Blair P.J., Putnam S.D., Uyeki T.M.. Epidemiology of cases of H5N1 virus infection in Indonesia, July 2005–June 2006. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, K. , Marciniak P., Rosiński G., Rychlik L.. Toxic activity and protein identification from the parotoid gland secretion of the common toad Bufo bufo. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 205:43-52. [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, P.K. , Kumar S., Pawar S., Sudheesh M.S., Pawar R.S.. Plant-based adjuvant in vaccine immunogenicity: A review. Current Traditional Medicine. 2018, 4, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F. , Wang Z., Cai P., Zhao L., Gao J., Kokudo N., Li A., Han J., Tang W.. Traditional Chinese medicine and related active compounds: a review of their role on hepatitis B virus infection. Drug. Discov. Ther. 2013, 7, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B. , Ke X.G., Yuan C., Chen P.Y., Zhang Y., Lin N., Yang Y.F., Wu H.Z.. Network pharmacology integrated molecular docking reveals the anti-COVID-19 mechanism of Xingnaojing injection. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020; 15, 1934578X20978025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A. , Abdelrahman A.H., Mohamed T.A., Atia M.A., Al-Hammady M.A., Abdeljawaad K.A., Elkady E.M., Moustafa M.F., Alrumaihi F., Allemailem K.S., El-Seedi H.R.. In silico mining of terpenes from red-sea invertebrates for SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) inhibitors. Molecules. 2021, 26, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. , Liang W., Yang S., Wu N., Gao H., Sheng J., Yao H., Wo J., Fang Q., Cui D., Li Y.. Human infections with the emerging avian influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and characterisation of viral genome. The Lancet. 2013, 381, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, A. , Lopez A.E., Wells A., Olsen M., Actor J.. The Fab fragment of anti-digoxin antibody (digibind) binds digitoxin-like immunoreactive components of Chinese medicine Chan Su: monitoring the effect by measuring free digitoxin. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2001, 309, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.H. , Bau D.T., Hsiao Y.T., Lu K.W., Hsia T.C., Lien J.C., Ko Y.C., Hsu W.H., Yang S.T., Huang Y.P., Chung J.G.. Bufalin induces apoptosis in vitro and has Antitumor activity against human lung cancer xenografts in vivo. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadava, U. , Yadav V.K., Yadav R.K.. Novel anti-tubulin agents from plant and marine origins: insight from a molecular modeling and dynamics study. RSC ADV. 2017, 7, 15917–15925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S. , Lee K.E., Dwivedi V.D., Yadava U., Panwar A., Lucas S.J., Pandey A., Kang S.G.. Discovery of Ganoderma lucidum triterpenoids as potential inhibitors against Dengue virus NS2B-NS3 protease. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 19059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, S. , Dubey A., Kamboj N.K., Sahoo A.K., Kang S.G., Yadava U. Drug repurposing for ligand-induced rearrangement of Sirt2 active site-based inhibitors via molecular modeling and quantum mechanics calculations. Sci Rep, 2021; 11, 10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. , Kumar S., Gupta V.K., Singh S., Dwivedi V.D., Mina U.. Computational assessment of Withania somnifera phytomolecules as putative inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CTP synthase PyrG. J BIOMOL STRUCT DYN. 2023, 41, 4903–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, K. , Antontsev V.G., Khotimchenko M., Gupta N., Jagarapu A., Bundey Y., Hou H., Maharao N., Varshney J.. Accelerated repurposing and drug development of pulmonary hypertension therapies for COVID-19 treatment using an AI-integrated biosimulation platform. Molecules. 2021, 26, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cmp | CBFi | BFi | ABFi | TBFi | BFTi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | -21.460 | -11.912 | -17.044 | -18.939 | -17.787 |

| Cmp | CBFi | BFi | ABFi | TBFi | BFTi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | -19.450 | -8.949 | -23.250 | -23.019 | -14.378 |

| Sample name | TC50 | IC50 | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBFi | 0.07 | 0.01 | 7.10 |

| BFi | 0.71 | 0.04 | 17.75 |

| ABFi | 0.09 | 0.01 | 11.25 |

| TBFi | 0.29 | 0.01 | 48.00 |

| BFTi | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).