Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Survey

| Variable | Variable description |

|---|---|

| SPREADING ENTREPRENEURSHIP (SP) | |

| 1.Advice | Provide an information and advisory service to the general public. |

| 2.Advice_free | Offering a service for free. |

| 4.Events | Number of events per year. |

| 5.Nb_y | How many events does the nursery hold per year? |

| 6.Channels | There are channels of information/communication/promotion of services. |

| 7.Publicat_Frec | Publication frequency in communication channels. |

| 8.Traing | Offering transversal courses and entrepreneurship support courses. |

| 9.Traing_Frec | Number of courses offered per month. |

| PREINCUBATION (PRE) | |

| 10.Shar_spac | Existence of preincubator or coworking facility |

| 11.Spac_free | Existence of free spaces to work |

| 12.Space_req | Are there any requirements to enter the preincubation phase? |

| 13.Proj_nb | Number of pre-incubated projects per year. |

| 14.Proj_advice | Having expert consulting sessions for pre-incubators. |

| 15.Proj_mon | There is monitoring of pre-incubated projects. |

| 16.Proj_traing | There are cross-sectional training workshops. |

| 17.Proj_Mtime | Number of years spent in preincubate |

| 18.PAE | Is the incubator an Entrepreneur Care Point (PAE)? |

| BASIC INCUBATION (INC) | |

| 19.Entry | There are selection criteria for access to incubation. |

| 20.Entry_crit | Which are the selection criteria for access to incubation? |

| 21.Servic | Services included in the rate. |

| 22.Nt_Frec | Frequency of networking meetings |

| 23.C_Frec | Frequency of consultancy sessions |

| 24.Ment_Frec | Frequency of mentoring sessions. |

| 25.Mon_Frec | Frequency follow-up or monitoring sessions. |

| 26.Traing | Offer of training courses adapted to the needs of clients. |

| 27.Traing_nb | Number of courses offered per month |

| ADVANCED INCUBATION (ADV) | |

| 28.Nc_agree | Interest groups with which the incubator has an agreement/collaboration agreement. |

| 29.Comp_exp | Percentage of hosted companies exporting their products. |

| 30.Comp_fd | Number of hosted companies have raised funding while hosted. |

| 31.Comp_job | Average number of jobs generated by the hosted companies. |

| 32.Inc_disc | A special rate is offered on technology services or products. |

| 33.Inc_agree | Interest groups with which the incubator has an agreement/collaboration agreement. |

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Typology of Business Incubators

Principal Component Analysis (PC)

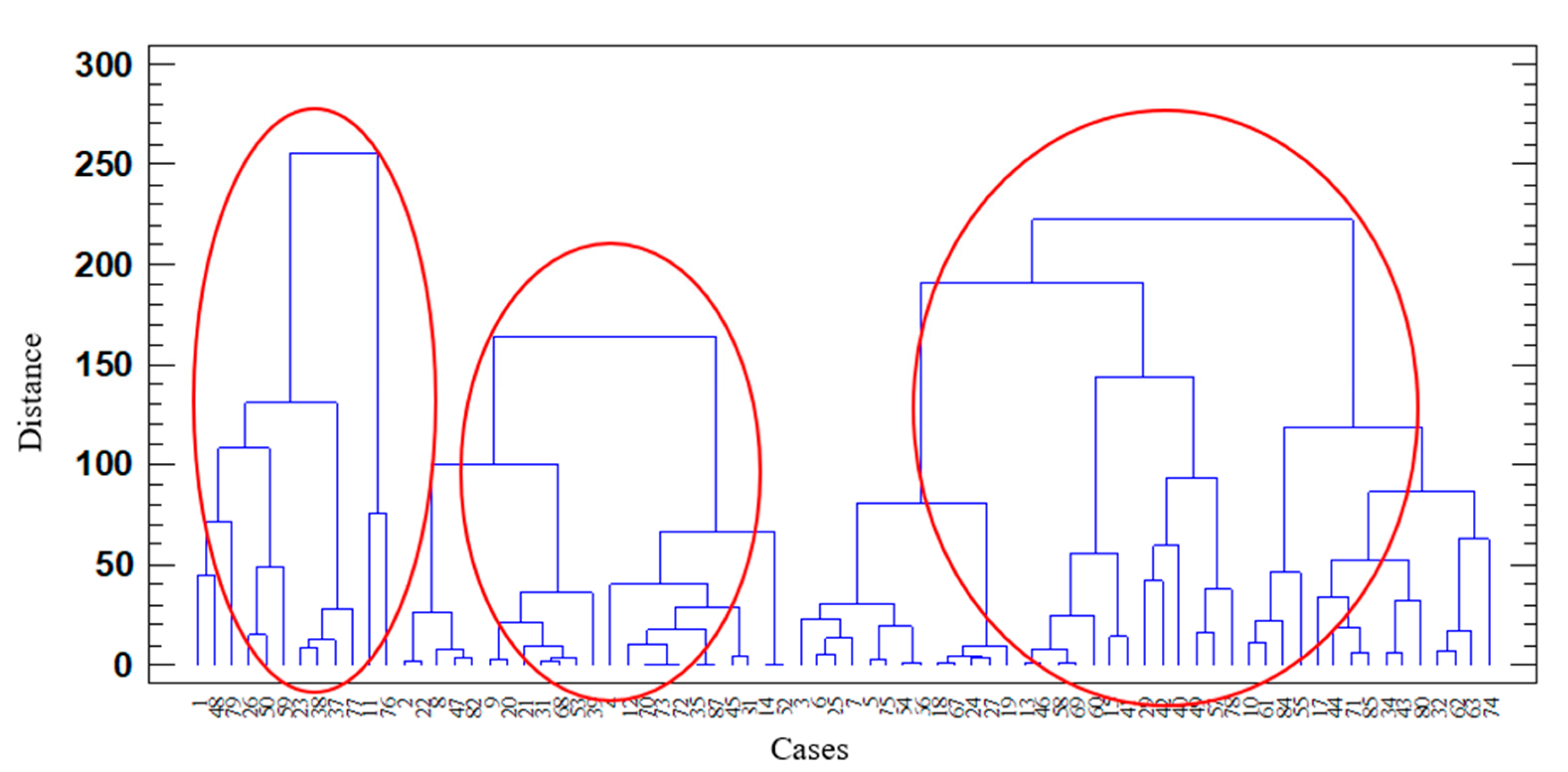

Cluster Analisys

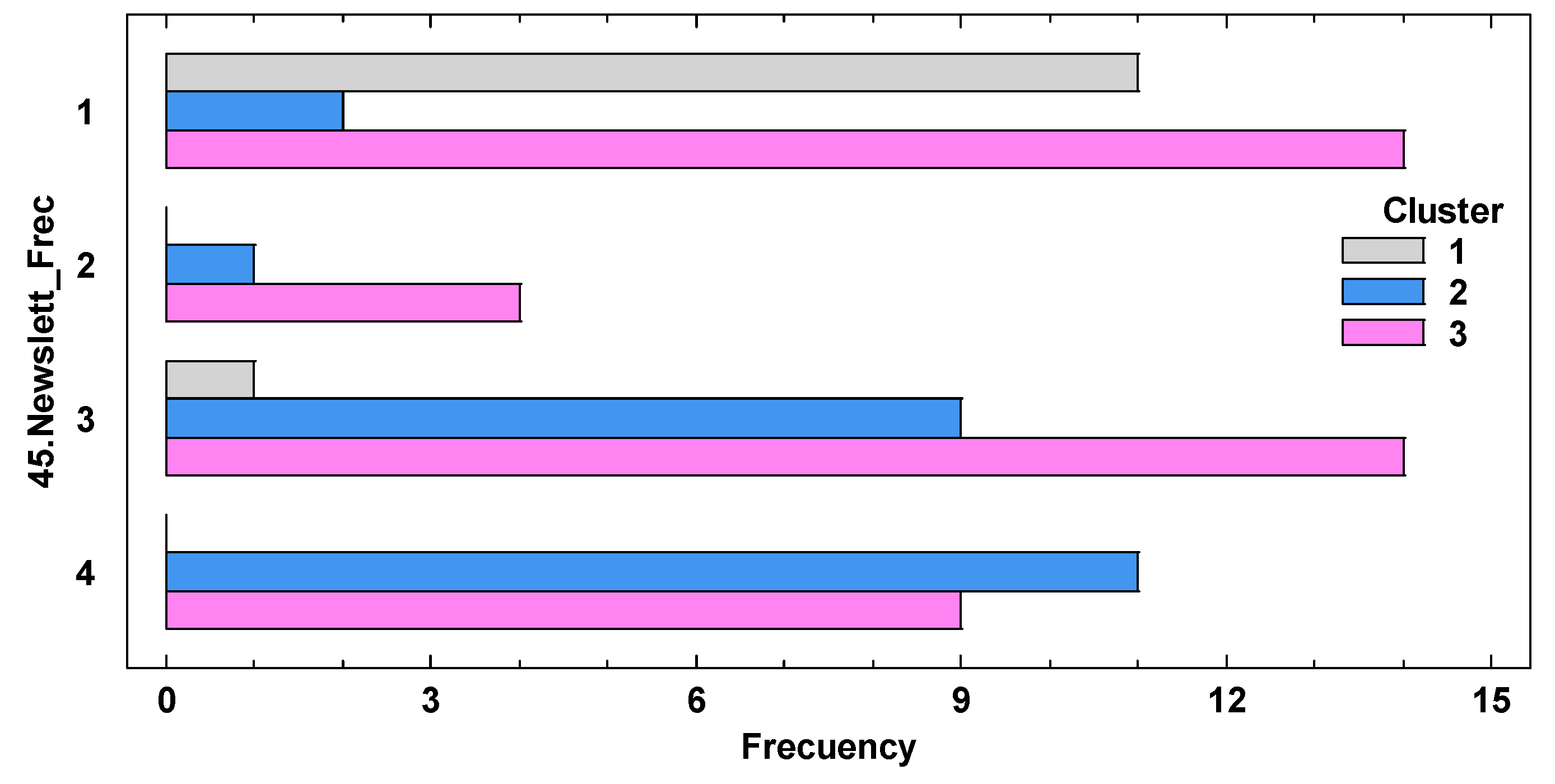

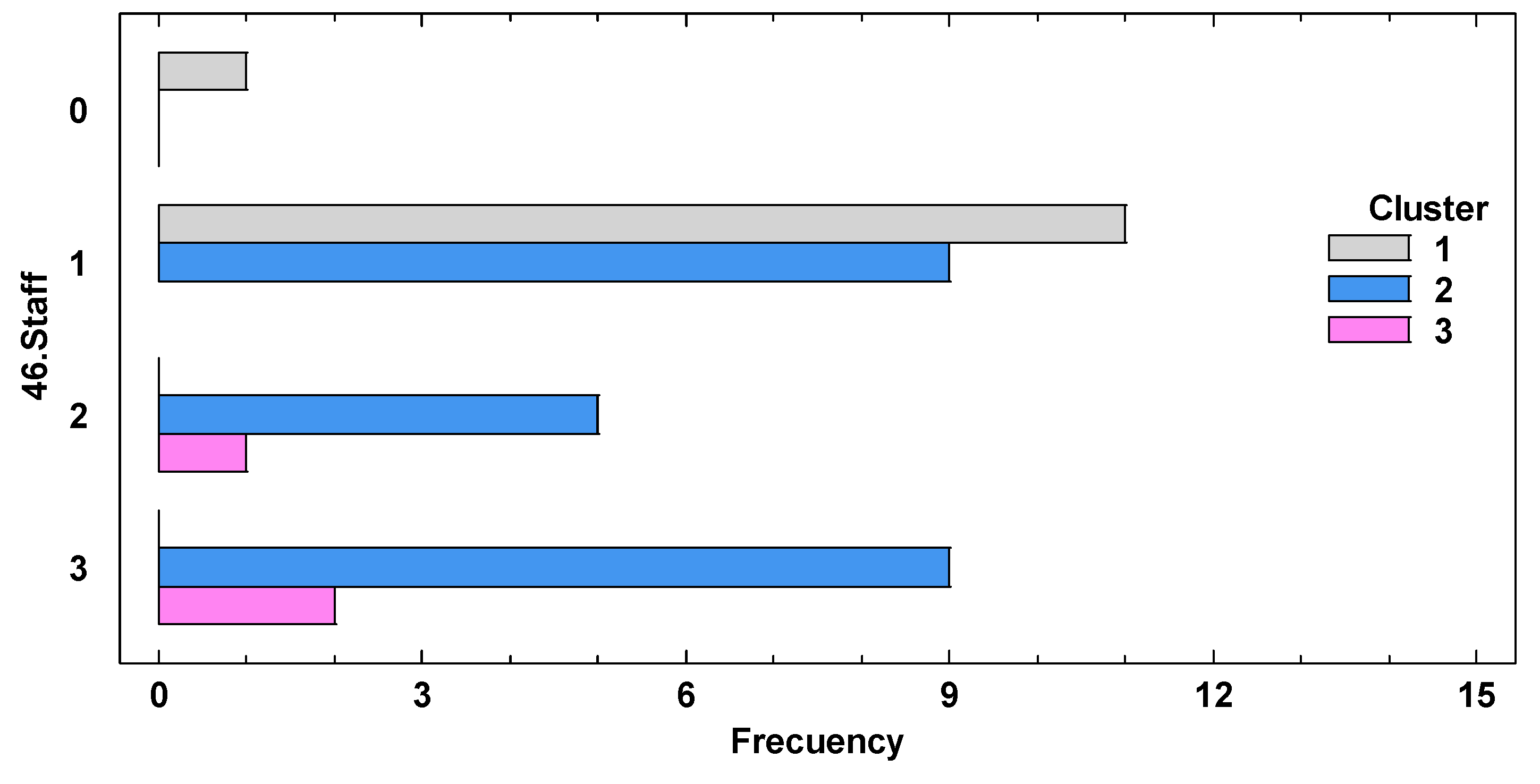

3.2. Characterization of the Typology of Business Incubator

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ressin, M. Start-Ups as Drivers of Economic Growth. Res. Econ. 2022, 76, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance. Available from: (accesed on 14 marzo 2024).

- Ferreiro Seoane, F. J.; Mendoza Moheno, J.; Hernández Calzada, M. A. Contribución de Los Viveros de Empresas Españolas En El Mercado de Trabajo. Contaduría Y Adm. 2018, 63, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Camayo Llallico, W.; Vásquez Calderón, C. M.; Zavaleta Núñez, L. E. Análisis Del Ecosistema Emprendedor Latinoamericano y Su Impacto En El Desarrollo de Startups. 2017. Available from.

- Ballering, T.; Masurel, E. Business Incubators and Their Engagement in Sustainable Development Activities: Empirical Evidence from Europe. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2020, 18(2). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Skare, M. A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis of Entrepreneurship and Crisis Literature Published from 1984 to 2020. 2021, 135, 304–318.

- Shehada, R. Y., El Talla, S. A., Al Shobaki, M. J., & Abu-Naser, S. S. (2020). Learning and Business Incubation Processes and Their Impact on Improving the Performance of Business Incubators. Available from:.

- Nations U. Micro-, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Day ES | Available from:.

- Martínez-Martínez, S. L. Entrepreneurship as a Multidisciplinary Phenomenon: Culture and Individual Perceptions in Business Creation. 2022, 35 (4), 537–565.

- De la Hoz-Villar, R.; Prieto-Flórez, J. Emprendimiento, Dinámica Empresarial y Empleo: Una Revisión Desde La Óptica Del Crecimiento Económico. 2020, 3 (1), 11–18.

- Flores-Bueno, D.; Jerez, O. Incubadoras de Negocios, Desempeño y Eficacia: Una Revisión Sistemática. 2023, 39(166), 93–109.

- Ayyash, S. A.; McAdam, M.; O’Gorman, C. Towards a New Perspective on the Heterogeneity of Business Incubator-Incubation Definitions. 2022, 69 (4), 1738–1752. [CrossRef]

- Blanco Jiménez, F. J.; Asensio Ciria, A.; de Esteban Escobar, D.; Fernández Fernández, M. T.; Santos Bartolomé, J. L.; Polo Garcia- Ochoa, C.; Aguirre Quezada, J. C. Los Servicios Prestan Viveros y aceleradoras de Empresas España/2023. Avalaible from.

- Morales, O. G.; Vázquez, R. P.; Cueva, A. B. C. Las Políticas de Emprendimiento En Europa: Un Estudio Comparado Por Países. 2019, 1 (1), 72–85.

- Cabrera Soto, M.; Souto Anido, L. El Papel De Las Incubadoras Como Catalizadoras De Emprendimientos De Alto Valor Agregado En Los Ecosistemas De innovación. Econ. desarro. 2023, 167.

- Vaz R, de Carvalho JV, Teixeira SF. Towards a Unified Virtual Business Incubator Model: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis 2022; 14:13205.

- De Esteban Escobar, D.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, JL; Blanco Jiménez, FJ; García, A. Incubadoras de empresas y supervivencia de startups en tiempos de COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2139. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Maza, M.; Fedriani, E. M. Defining Entrepreneurial Success to Improve Guidance Services: A Study with a Comprehensive Database from Andalusia. 2022, 11 (1), 1–26.

- Díaz, S. R.; Anido, L. S.; Martínez, J. R. El Proceso de Selección de Proyectos En Las Incubadoras de Empresas. Propuesta de procedimiento para una incubadora universitaria cubana. 2019, 7(2), 20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Macías, G.; Mora Macías, T. C. Modelo Para El Acompañamiento En La Incubación de Emprendimientos a Estudiantes de Pregrado de La Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Administrativas y Contables de La UNAB. 2019.Available from.

- Paredes, N.; Peñaloza, S.; Rivera, P. Las Incubadoras y Semilleros de Empresas: Un Análisis de La Realidad En La Zona 3. 2020, 5 (3), 75–92.

- Paz, I. M. J. Emprendimiento Rural Como Estrategia de Desarrollo Territorial: Una Revisión Documental. 2022, 43 (1), 257–280.

- Ramírez, P. L. V.; González, M. G. Z.; Tene, M. F. M. Emprendimiento y su relación con el desarrollo económico y local en el Ecuador. 2020, 5 (10), 242–258.

- Handoyo, S.; Firdaussy, U. F.; Kholiyah, S. Technology Business Incubator Service Challenges During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Traditional Incubator Versus Virtual Incubator. 2021, 24 (2.

- Vaz, R.; de Carvalho, J. V.; Teixeira, S. F. Towards a Unified Virtual Business Incubator Model: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. 2022, 14 (20), 13205.

- Lúa, E. E. Z.; Martínez, Y. E. G.; Fontes, M. M. M. Incubadoras de Empresas En Las Universidades Como Modelo de Innovación Desde La Triple Hélice. 2020, 7(14), 19–42.

- Rudawska, J. The Incubation Programme as an Instrument for Supporting Business Ideas at University. An Example from Poland. 2020, 52(125), 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga, M. E. G.; Morales, J. C. B. Startup y Spinoff: Una Comparación Desde Las Etapas Para La Creación de Proyectos Empresariales. 2016, 24 (36), 365–378.

- Hacktt SM, Dilts DM. A Real Options-Driven Theory of Business Incubation. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2004 Jan;29(1):41–54.

- Centro de Información y Red de Creación de Empresas (CIRCE). Available from: [cited 2023 Jul 10].

- Breivik-Meyer, M.; Arntzen-Nordqvist, M.; Alsos, G. A. The Role of Incubator Support in New Firms Accumulation of Resources and Capabilities. 2020, 22 (3), 228–249.

- Niammuad, D., Mapompech, K., & Suwanmaneepong, S. (2014). Emprendimiento Innovación de Productos. Un Análisis Factorial de Segundo Orden. The Journal of Applied Business Research, 30(1), 197-120.

- Paoloni, P.; Modaffari, G. Business Incubators vs Start-Ups: A Sustainable Way of Sharing Knowledge. 2022, 26(5), 1235–1261.

- Gómez, Núñez, Liyis. Evaluación del impacto de las incubadoras de empresas: estudios realizados. Pensamiento y Gestión [Internet]. 2002 nov [cited 2023 Jul 10];(13):1–23. Available from.

- Hausb Hausberg, J. P.; Korreck, S. Business Incubators and Accelerators: A Co-Citation Analysis-Based, Systematic Literature Review; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021.

- Deyanova, K.; Brehmer, N.; Lapidus, A.; Tiberius, V.; Walsh, S. Hatching Start-Ups for Sustainable Growth: A Bibliometric Review on Business Incubators. 2022, 16 (7), 2083–2109.

- UFLA, L. G. R. A.; Sifuentes Araújo FUOM-gsa, G. Estabelecendo o Modelo de Negócio de Incubadoras: Delineamento Sob a Ótica Da Literatura Nacional e Internacional. 2020.

- Kasanagottu, S.; Bhattacharya, S. An Empirical Analysis of Significant Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Behavior in the Information Technology Industry. 2018, 7 (4.10), 212–216.

- Tang, M., Walsh, G. S., Li, C., & Baskaran, A. (2021). Exploring Technology Business Incubators and Their Business Incubation Models: Case Studies from China. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46, 90-116.

- Alayoubi, Mansour M., Al Shobaki, Mazen J., Abu- Naser, Samy S. (2020). «Requisitos Para Aplicar El Emprendimiento Estratégico Como Punto de Entrada Para Mejorar La Innovación Técnica: Caso de Estudio — Palestine Technical College- Deir Al-Balah», International Journal of Business and Management Invention (IJBMI), 9(3): 1-17.

- Shahada, Rania Y., El Talla, Suliman A., Al Shobaki, Mazen J., Abu-Naser, Samy S. (2020). La Realidad Del Uso Del Cuadro de Mando Equilibrado En Incubadoras de Empresas, International Journal of Engineering and Information Systems (IJEAIS), 4(3): 67-95.

- Owda, M. O.; Owda, R. O.; Abed, M. N.; Abdalmenem, S. A.; Abu-Naser, S. S.; Al Shobaki, M. J. Personal Variables and Their Impact on Promoting Job Creation in Gaza Strip through Business Incubators. 2019.

- Benavides-Sánchez, E. A.; Castro-Ruíz, C. A.; Narváez, M. Á. B. El Emprendimiento de Base Tecnológica y Su Punto de Encuentro Con La Convergencia Tecnocientífica: Una Revisión a Partir Del Algoritmo Tree of Science. 2023, 9 (19), e2153.

- Habiburrahman; Prasetyo, A.; Raharjo, TW; Rinawati, SA; Trisnani; Eko, BR; Wahyudiyono; Wulandari, SN; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; et al. Determinación de factores críticos para el éxito en incubadoras de empresas y nuevas empresas en Java Oriental. Sostenibilidad 2022, 14, 14243.

- Mecha-López, R.; Velasco-Gail, D. El Ecosistema Innovador de Las Spin-Offs Universitarias: Espacios, Agentes y Redes de Transferencia En Los Casos de Estudio Regionales de Madrid y Andalucía. 2023, No. 45, 146–166.

- Leal, M.; Leal, C.; Silva, R. The Involvement of Universities, Incubators, Municipalities, and Business Associations in Fostering Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Promoting Local Growth. 2023, 13(12), 245.

- Ballering, T.; Masurel, E. Business Incubators and Their Engagement in Sustainable Development Activities: Empirical Evidence from Europe. 2020, 18 (2).

- Vaz, R.; de Carvalho, J. V.; Teixeira, S. F. Towards a Unified Virtual Business Incubator Model: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. 2022, 14 (20), 13205.

- Toril, J. U.; de Pablo Valenciano, J. Aproximación Al Modelo Europeo de Viveros de Empresas. Estudio de Casos. 2009, No. 2973.

- Velasco Gail, D.; Mecha López, R. Los servicios de apoyo a las empresas basadas en el conocimiento universitario: el caso de la comunidad de Madrid y las spin off de las universidades públicas de su ecosistema innovador, 1st ed.; Gago García, C. (ed. lit. ), Córdoba y Ordóñez, J. A. (ed. lit. ), Alonso Logroño, M. del P. (ed. lit. ), Jordá Borrell, R. M. (ed. lit. ), Ventura Fernández, J. (ed. lit. ), Eds.; Una perspectiva integrada: aportaciones desde las Geografías Económica, Regional y de los Servicios para la cohesión y la competitividad territorial; Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2021; pp 245–252.

- Mas-Verdú, F., Ribeiro-Soriano, D. y Roig-Tierno, N. (2015). Firm Survival: The Role of Incubators and Business Characteristics. Journal of Business, 68(4), 793-796.

- Lian, C. L. Viveros de Empresa: Mecanismos Dinamizadores de La Capacidad de Innovación Empresarial. Análisis de Los Viveros de Empresas de La Comunidad de Madrid. 2020, 51(165), 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez González JP. Análisis de la Eficiencia de los Viveros de Empresas de la Comunidad de Madrid. Burjc digital Urjc es [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Jul 10]; Available from.

- Al-Mubaraki, H.; Wong, S. F. How Valuable Are Business Incubators? A Case Illustration of Their Performance Indicators; 2011; Vol. 30.

- Antonovica A, de Esteban Curiel J, Herráez BR. Factors that determine the degree of fulfilment of expectations for entrepreneurs from the business incubator programmes 2023;19:261–91.

- Lúa, E. E. Z.; Martínez, Y. E. G.; Fontes, M. M. M. Incubadoras de Empresas En Las Universidades Como Modelo de Innovación Desde La Triple Hélice. 2020, 7 (14), 19–42.

- Velasco Uribe, J. X. Estructuración de Una Guía de Acompañamiento Para La Línea Estratégica de Incubación Del Centro de Desarrollo Empresarial de La Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana Seccional Bucaramanga. 2020.

- Arribas, E. H.; Novales, A.; Vicente, F. Condiciones Que Favorecen El Emprendimiento: Análisis Económico y Propuestas. 2021, 282, 1–11.

- de Esteban Escobar, Débora, Relational coordination in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. 2020. Available at SSRN: or.

- Blanco Jiménez, F. J.; Asensio Ciria, A.; de Esteban Escobar, D.; Fernández Fernández, M. T.; Santos Bartolomé, J. L.; Polo Garcia- Ochoa, C.; Aguirre Quezada, J. C. Los Servicios Prestan Viveros y aceleradoras de Empresas España/2023. Available from.

- Capatina, A.; Cristea, D. S.; Micu, A.; Micu, A. E.; Empoli, G.; Codignola, F. Exploring Causal Recipes of Startup Acceptance into Business Incubators: A Cross-Country Study. 2023, 29 (7), 1584–1612.

- Gelasakis, A. I.; Valergakis, G. E.; Arsenos, G.; Banos, G. Description and Typology of Intensive Chios Dairy Sheep Farms in Greece. 2012, 95 (6), 3070–3079.

- Syakur, M. A., Khotimah, B. K., Rochman, E. M. S., & Satoto, B. D. (2018, April). Integration k-means clustering method and elbow method for identification of the best customer profile cluster. In IOP conference series: materials science and engineering (Vol. 336, p. 012017). IOP Publishing.

- Shi, C., Wei, B., Wei, S., Wang, W., Liu, H., & Liu, J. (2021). A quantitative discriminant method of elbow point for the optimal number of clusters in clustering algorithm. Eurasip Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking, 2021, 1-16.

- van Rijnsoever, F. J. Meeting, Mating, and Intermediating: How Incubators Can Overcome Weak Network Problems in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. 2020, 49 (1), 103884.

- Klingbeil, C.; Semrau, T. For Whom Size Matters – the Interplay between Incubator Size, Tenant Characteristics and Tenant Growth. 2017, 24 (7), 735–752.

- Paniagua-Rojano, F. J. Comunicación y Startups. Análisis de la situación actual de las incubadoras de empresas emergentes y su actividad comunicativa; Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación, 2022.

- Bastanchury-López, M. T.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; García-Martínez, A. R.; Martín-Romo-Romero, S. Revisión de La Medición de Capacidades Dinámicas: Una Propuesta de Indicadores Para El Sector Ovino. 2019, 20 (2), 355–386.

- Oh, W.-Y.; Chang, Y. K.; Jung, R. Experience-Based Human Capital or Fixed Paradigm Problem? CEO Tenure, Contextual Influences, and Corporate Social (Ir)Responsibility. 2018, 90, 325–333.

- Almeida, R. I. da S.; Pinto, A. P. S.; Henriques, C. M. R. O Efeito Da Incubação No Desempenho Das Empresas: Um Estudo Comparativo Na Região Do Centro de Portugal. 2021, 23, 127–140.

- Lukes, M.; Longo, C.; Zouhar, J. Do Business Incubators Really Enhance Entrepreneurial Growth? Evidence from a Large Sample of Innovative Italian Start-Ups. 2019, 25–34.

- Peña Ramírez, C.; Moreno, A.; Amestica, L.; Silva, S. Incubadoras En Red: Capital Relacional de Incubadoras de Negocios y La Relación Con Su Éxito. 2019, 5, 162–179.

- Pattanasak, P.; Anantana, T.; Paphawasit, B.; Wudhikarn, R. Critical Factors and Performance Measurement of Business Incubators: A Systematic Literature Review. 2022, 14 (8).

- Zapata-Guerrero, F. T.; Ayup, J.; Mayer-Granados, E. L.; Charles-Coll, J. Incubator Efficiency vs Survival of Start-Ups. 2021, 55, 511–530.

- Gaytán Cortés, Juan. El plan de negocios y la rentabilidad. 2022. Mercados y negocios, 21(42), 143-156.

- Pico, M. Y. M.; Montalvo, L. R.; Pallerols, G. M. C. El Plan de Negocios y Su Papel En La Gestión Empresarial. 2023, 150–159.

- Alonso González, J. M. Plan de Empresa: Tecnoinver. 2023.

- Becerra Ardila, L.; Arenas Díaz, P.; Aguilera Monroy, L. Experiencias Significativas de Sistemas Regionales de Innovación En Incubadoras de La Red Cyted Iberincu. 2023.

- Landeros García, C.; Terán Cázares, M. M.; Blanco Jiménez, M. Business Success Factors within Business Incubators, Validation of the Research Tool (Factores de Éxito Empresarial Dentro de Las Incubadoras de Empresas, Validación de La Herramienta de Investigación). 2021, 18 (35), 71–82.

- Kehinde Feranmi, A.; Noluthando Zamanjomane, M.; Funmilola Olatundun, O; Chidera Victoria, I; Oluwafunmi Adijat, E. and Onyeka Franca, A. Business Incubators and Their Impact on Startup Success: A Review in the USA. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 2024, 11(01), 1418–1432.

- Redondo, M.; Camarero, C. Relationships between Entrepreneurs in Business Incubators. An Exploratory Case Study. 2017, 24, 1–18.

- Romero, M.; León, R.; Castemmanos, G. Modelo de gestión de incubadora de empresa para la transferencia de resultados de I+D+i en universidades ecuatorianas. 2020, 798, 1015.

- Salas Laime, W. Perfil emprendedor y su relación con la incubación empresarial en los estudiantes de la escuela profesional de Administración, Universidad Nacional Micaela Bastidas de Apurímac Sede Abancay, 2018. 2021.

- Barrios Zarta, J.; Gómez, N. R. Creación centro de desarrollo empresarial- Cedem-del instituto tolimense de formación técnica profesional, ITFIP, ESPINAL–TOLIMA. 2021.

- Zapata-Molina, C.; Montes-Hincapié, J. M.; Londoño-Arias, J.; Baier-Fuentes, H. El valle de la muerte de los emprendimientos: Una Revisión Sistemática de Literatura. 2022, No. 78, 18–30.

- Momin, U.; Mehak, S. T.; Kumar, M. D. Strategic Planning and Risk Management in the Startup, Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Best Practices and Challenges. 2023, 3 (2).

- Nair, S.; Blomquist, T. Failure Prevention and Management in Business Incubation: Practices towards a Scalable Business Model. 2019, 31(3), 266–278.

- Wu W, Wang H, Wu YJ. Internal and external networks, and incubatees’ performance in dynamic environments: entrepreneurial learning’s mediating effect 2021;46:1707–33.

- Kiran R, Bose SC. Stimulating business incubation performance: role of networking, University linkage and facilities 2020;32:1407–21.

- Alpenidze, O.; Pauceanu, A. M.; Sanyal, S. Key success factors for business incubators in europe: an empirical study. 2019, 25 (1), 1–13.

| Variable | Variable description |

| GRADUATION (GRD) | |

| 34.Agree | Does the incubator have agreements to facilitate the installation of companies abroad once outside the nursery? 0, No; 1, Yes |

| 35.Crit | Graduation criteria. 1, Non-compliance with objectives and others; 2, Limited period of time; 3 Meeting objectives |

| 36.Com_nb | Total number of companies graduated since the incubator opened. 1, <10; 2, 10- 50; 3, 51-100; 4, >100 |

| 37.Com_Iv | Of the graduate companies, what is the percentage that continues their activity abroad now? 1, <25; 2, between 26-50; 3, 51-75; 4, >76 |

| 38.Com_dd | Percentage of companies that ceased their activity during their stay. 1, >76; 2, between 51- 75; 3, 26-50; 4 <25 |

| 39.Com_fd_Pb | Percentage of graduates who have obtained funds/public funding. 1, <20; 2, between 21-40; 3, 41- 60; 4, 61-80; 5, >81 |

| 40.Com_fd_pr | Percentage of graduates who have obtained funds/private funding. 1, <20; 2, between 21-40; 3, 41-60; 4, 61-80; 5, >81 |

| 41.Mon | Contact with graduates is maintained. 0, No; 1, Yes |

| 42.Mon_act | There are specific actions/initiatives with the graduates. 1, Nothing specific is done or frequent contact with them is maintained; 2, Survival and Evolution Tracking; 3, Networking events between graduates and entrepreneurs/professionals of interest; 4, Trainers/Lowers of Hosted Enterprises; 5, Networking meetings or events between graduates and hosted. |

| OPERATIVE (GA) | |

| 43.Network | Belong to a network. 0, No; 1, Yes |

| 44.Offices_nb | Capacity of the incubator (Nº of offices). 1, <10; 2, 11-20; 3, 21-30; 4 >30 |

| 45.Newslett_Frec | Shipping Frequency. 1, Not send; 2, Quarterly; 3, Monthly; 4, Weekly |

| 46.Staff | Staff required for daily operations (N° persons). 1, <3; 2, 4-5; 3, >5 persons |

| 47.Expenses | Annual operating expenses budget (€/y). |

| 48.Revenues | Annual operating revenue budget (€/y). |

| Items | Loading | Eigenvalue | Explained variance (%) | Acumulate | PC |

| 10.Shar_spac | 0.61 | 8.00 | 32.01 | 32.01 | 1 |

| 13.Proj_nb | 0.68 | 1 | |||

| 14.Proj_advice | 0.82 | 1 | |||

| 15.Proj_mon | 0.83 | 1 | |||

| 16.Proj_traing | 0.65 | 1 | |||

| 8.Traing | 0.62 | 2.47 | 9.91 | 41.91 | 2 |

| 9.Traing_Frec | 0.77 | 2 | |||

| 26.Traing | 0.70 | 2 | |||

| 32.Inc_disc | 0.64 | 2 | |||

| 23.C_Frec | 0.76 | 1.71 | 6.86 | 48.77 | 3 |

| 24.Ment_Frec | 0.71 | 3 | |||

| 25.Mon_Frec | 0.76 | 3 | |||

| 6.Channels | 0.71 | 1.37 | 5.46 | 54.22 | 4 |

| 7.Publicat_Frec | 0.67 | 4 | |||

| 22.Nt_Frec | 0.72 | 4 | |||

| 19.Entry | 0.84 | 1.36 | 5.43 | 59.65 | 5 |

| 20.Entry_crit | 0.86 | 5 | |||

| 1.Advice | 0.82 | 1.26 | 5.03 | 64.68 | 6 |

| 3.Advice_nb | 0.63 | 1.13 | 4.52 | 69.20 | 7 |

| 18.PAE | 0.80 | 7 | |||

| 11.Spac_free | 0.91 | 1.07 | 4.27 | 73.47 | 8 |

| PC | Cluster | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1 | -7.4766 | 4.1812 | -0.1573 |

| 2 | -8.2974 | 3.9628 | 0.2054 |

| 3 | -6.2827 | 1.4973 | 0.9989 |

| 4 | -5.5285 | 2.8182 | 0.03716 |

| 5 | -2.5355 | 2.4939 | -0.6569 |

| 6 | -3.5733 | 1.5787 | 0.1602 |

| 7 | -2.7583 | 1.9444 | -0.2835 |

| 8 | -0.9970 | 0.4338 | 0.0485 |

| Variables | Cluster | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | p-Value1 | ||

| 43.Network (%) | 0 | 10.53 | 5.26 | 15.79 | * |

| 1 | 5.26 | 25,00 | 38.16 | ||

| 44.Offices_nb | 1 | 9.21 | 5.26 | 17.11 | * |

| 2 | 1.32 | 7.89 | 22.37 | ||

| 3 | 2.63 | 6.58 | 6.58 | ||

| 45.Newslett_Frec (%) | 1 | 14.47 | 2.63 | 18.42 | *** |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 3 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.32 | ||

| 4 | 5.26 | 5.26 | 5.26 | ||

| 46.Staff | 1 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.32 | *** |

| 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 4 | 14.47 | 14.47 | 14.47 | ||

| 34.Grd_agree (%) | 1 | 15.79 | 15.79 | 15.79 | * |

| 2 | 15.79 | 15.79 | 15.79 | ||

| 41.Grd_mon (%) | 1 | 7.89 | 7.89 | 7.89 | ** |

| 2 | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.32 | ||

| 42.Grd_mon_act (%) | 1 | 12.00 | 12.00 | 12.00 | *** |

| 2 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 3 | 24.00 | 24.00 | 24.00 | ||

| 4 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.67 | ||

| 5 | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.67 | ||

| 1p-Value: *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 | |||||

| Variable | Clúster | p-Value 1 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 37.Grd_com_Iv | 2.67 a | 3.30 b | 3.46b | * |

| 40.Grd_com_fd_pr | 1.75ab | 2.30b | 1.54a | * |

| 47.Expenses | 25,056a | 865,224b | 156,342a | * |

| 48.Revenue | 36,700a | 801,381b | 168,867ab | * |

| 1p-Value: *p < 0.05 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).