Submitted:

25 March 2024

Posted:

26 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

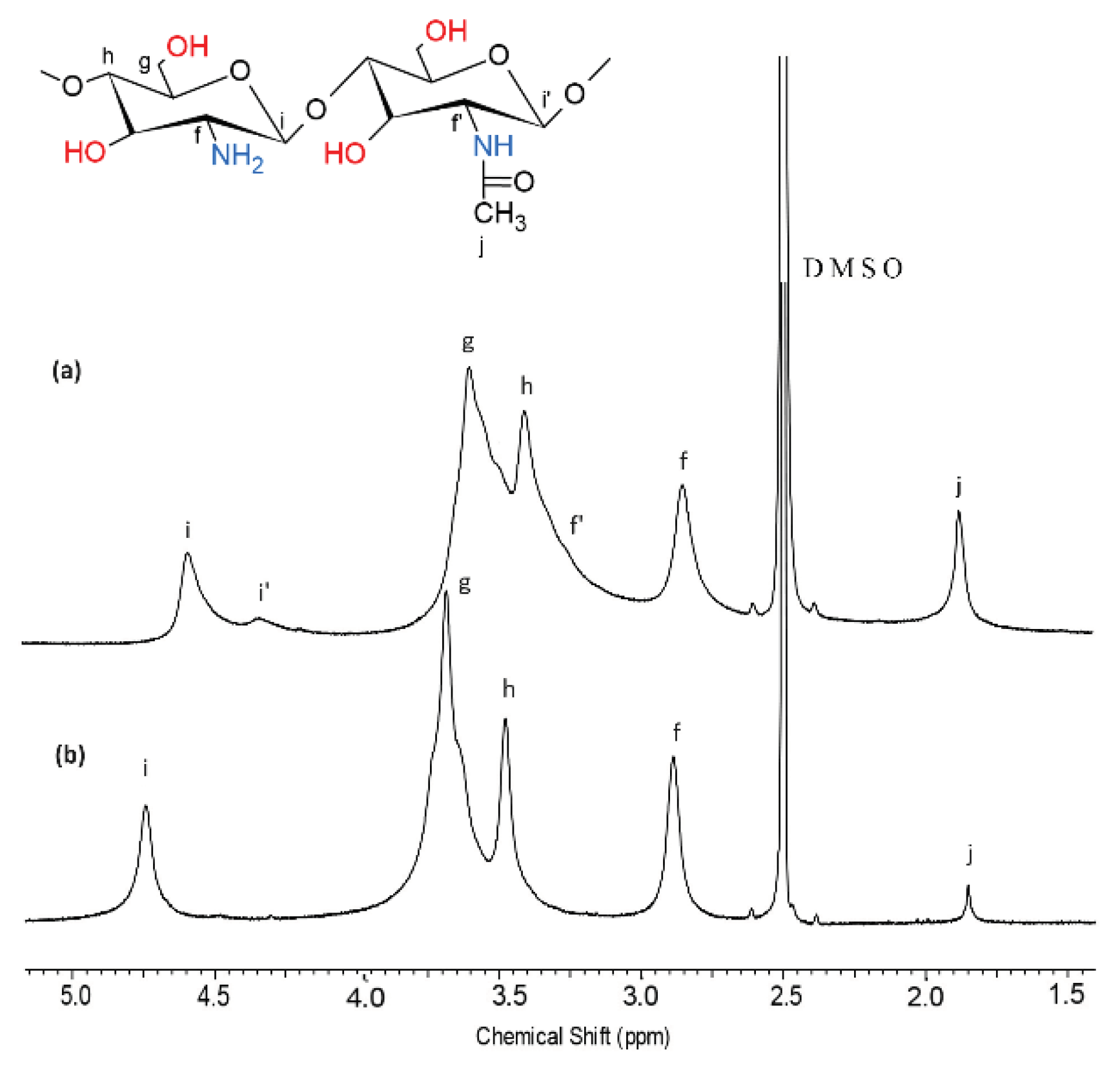

2.1. N-Deacetylation of Chitosan

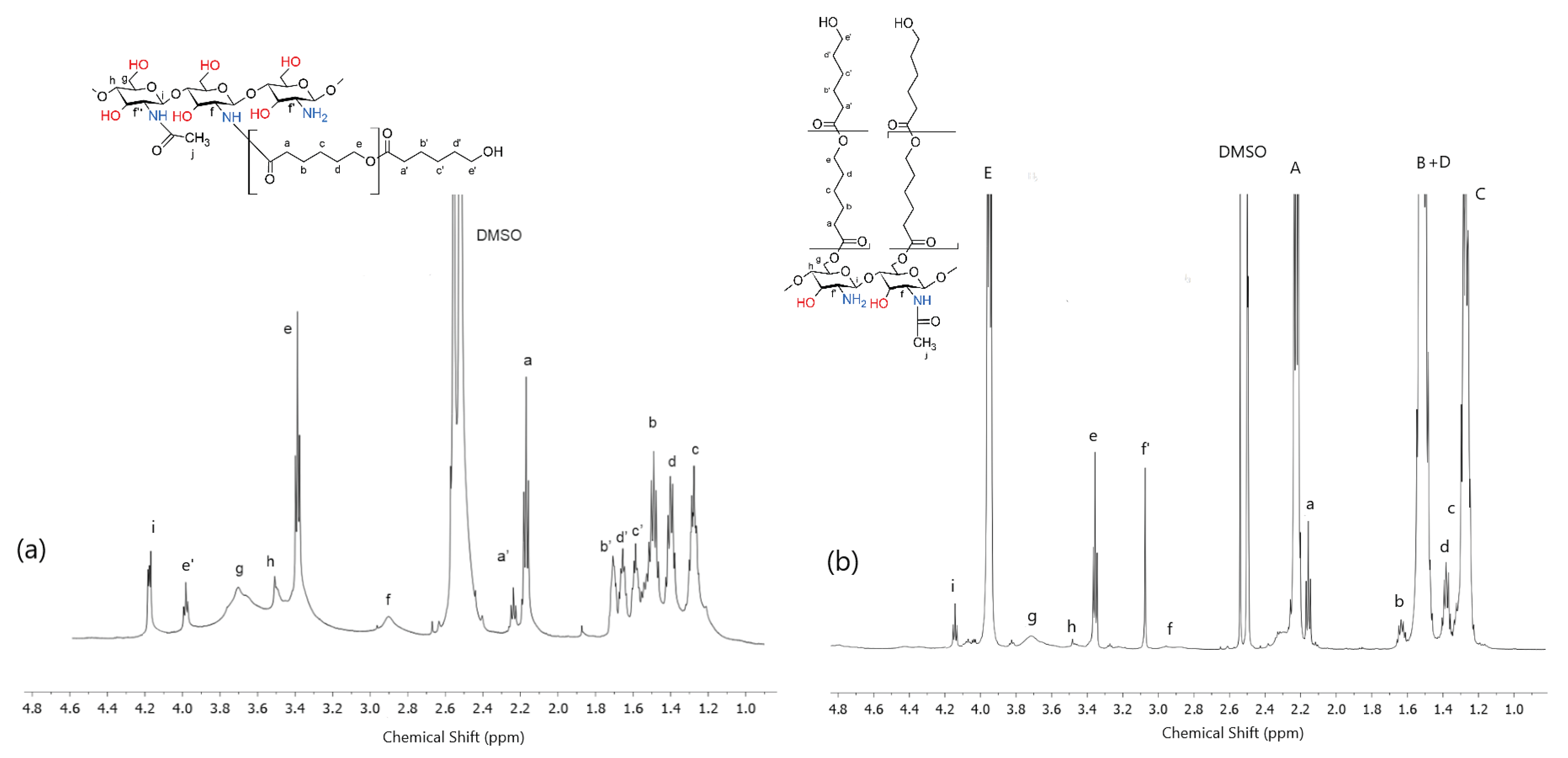

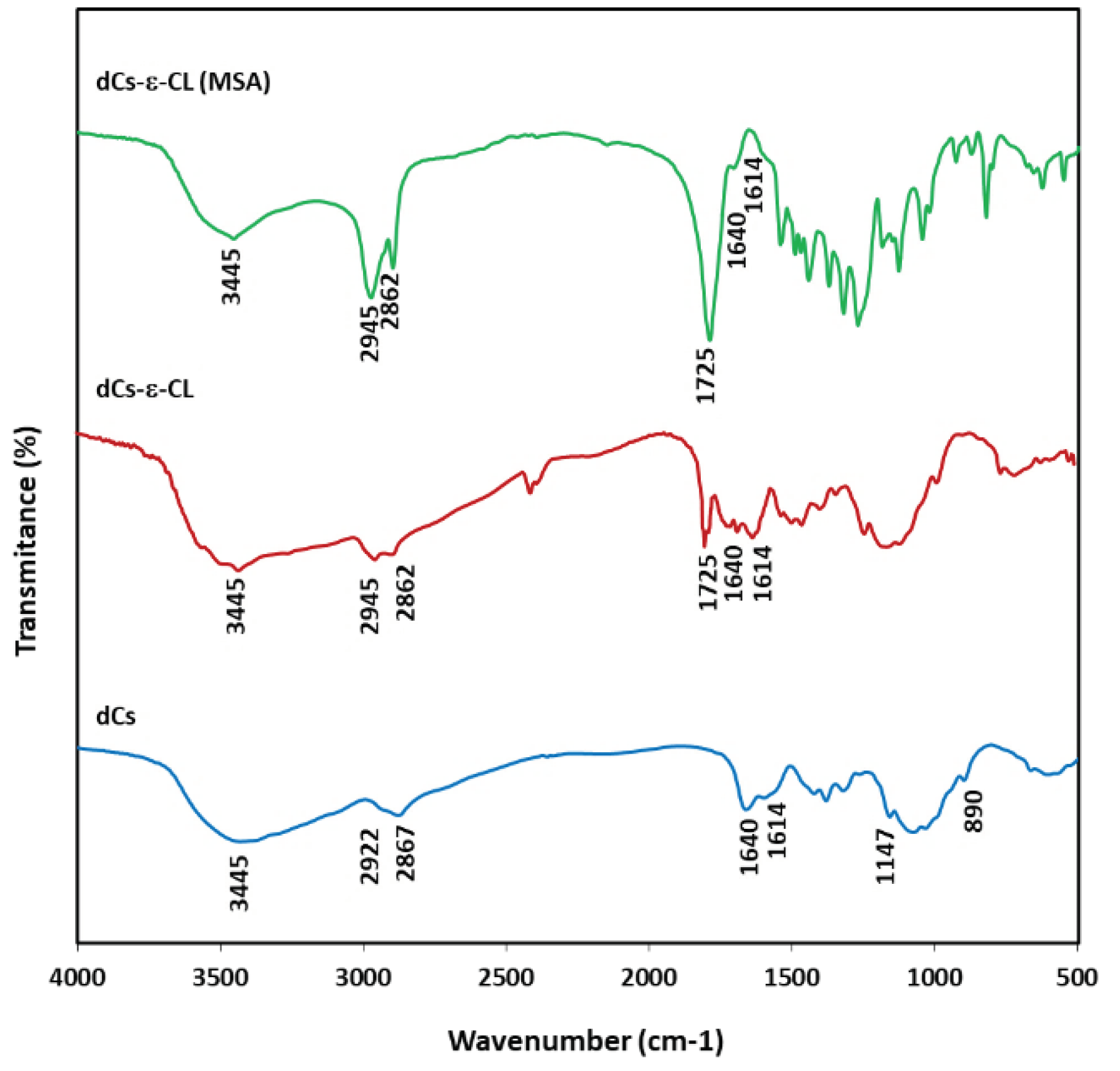

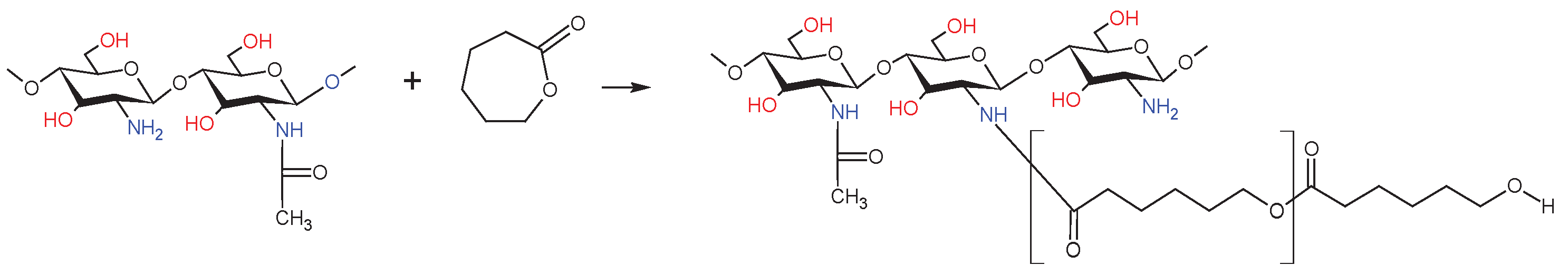

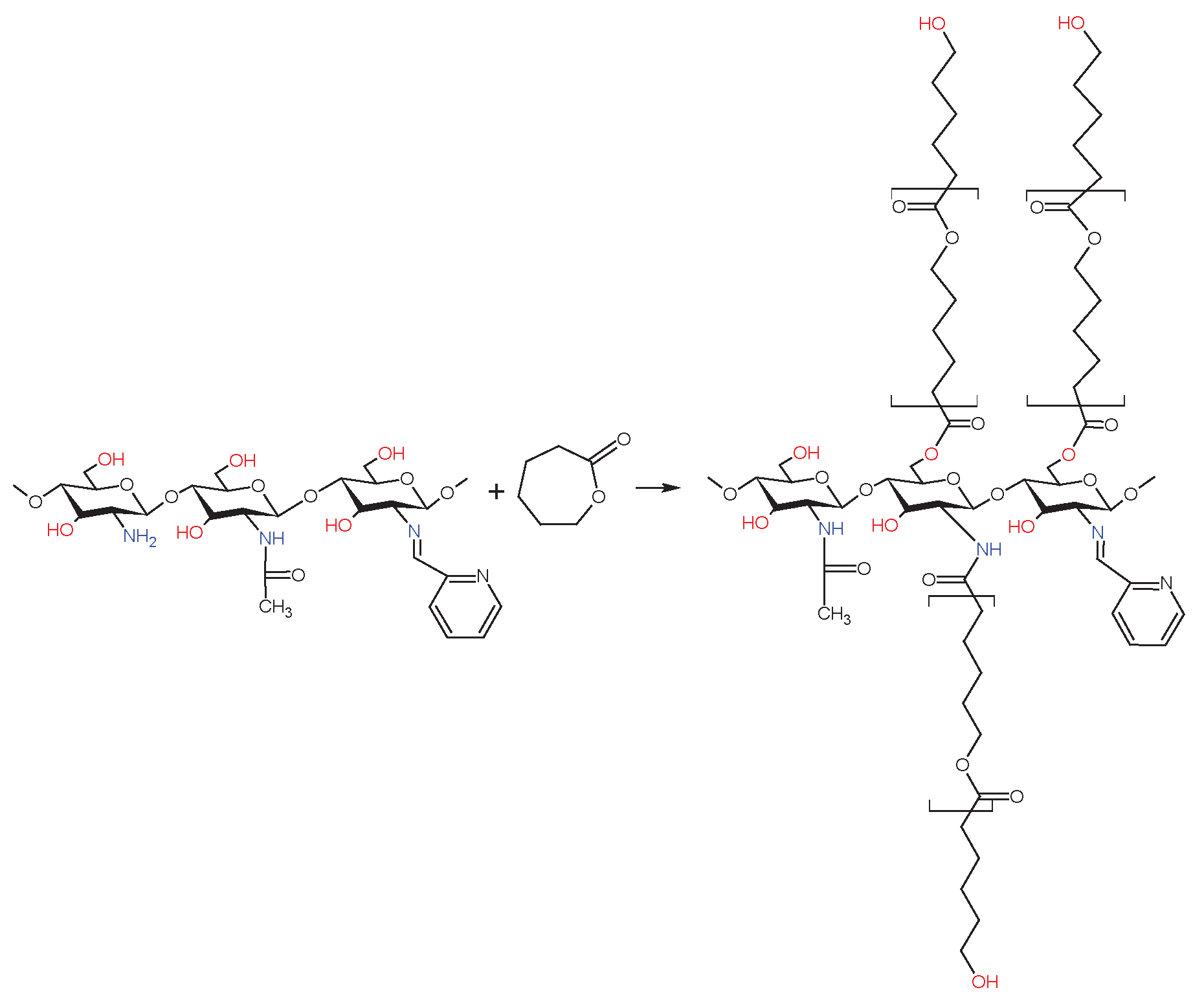

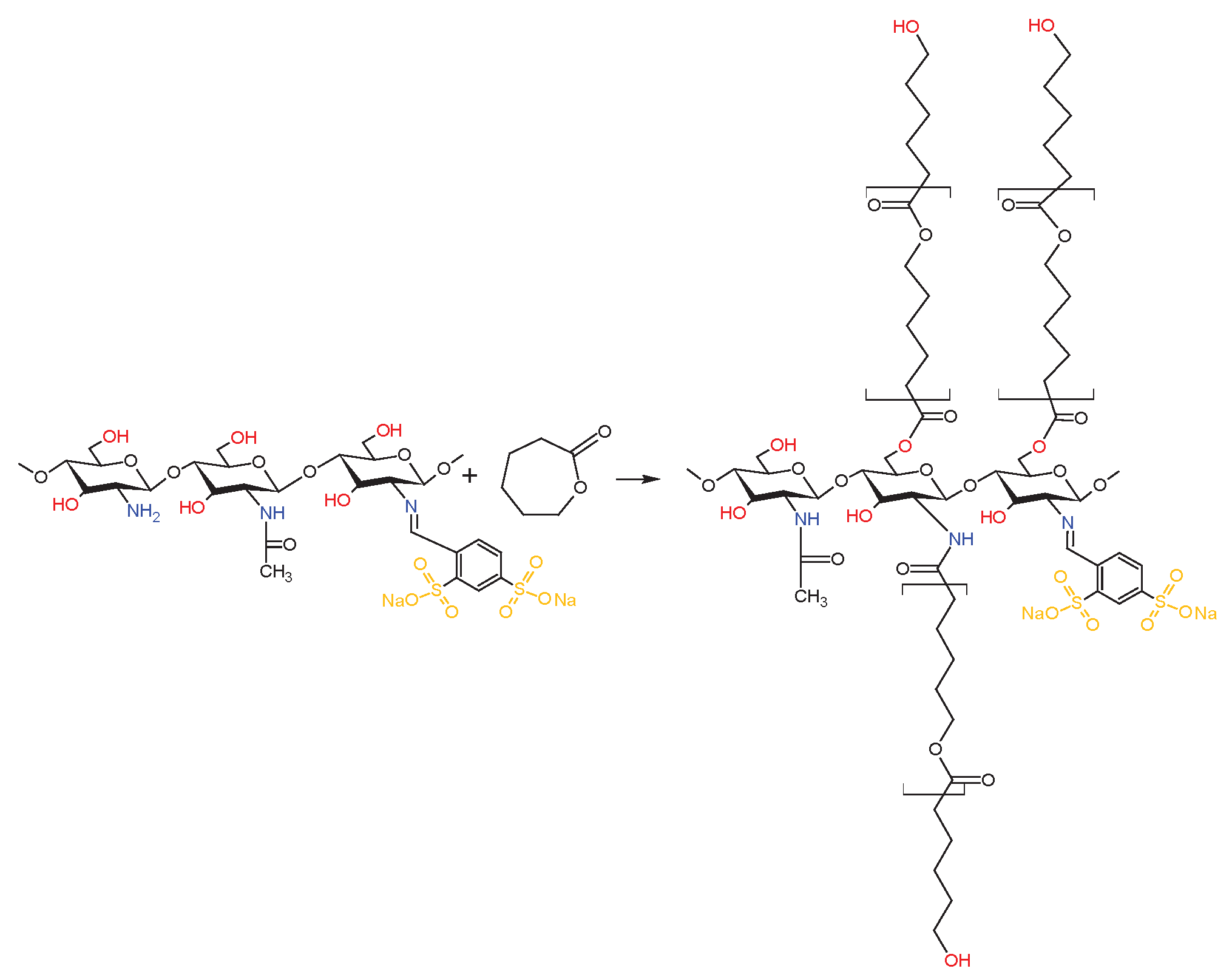

2.2. Chemical Structure of dCs-ε-CL and dCs-ε-CL(MSA)

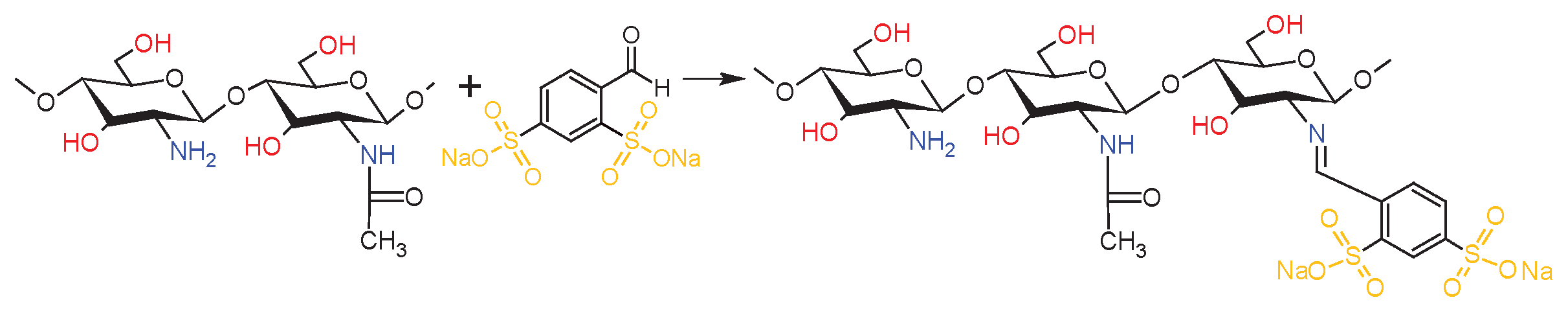

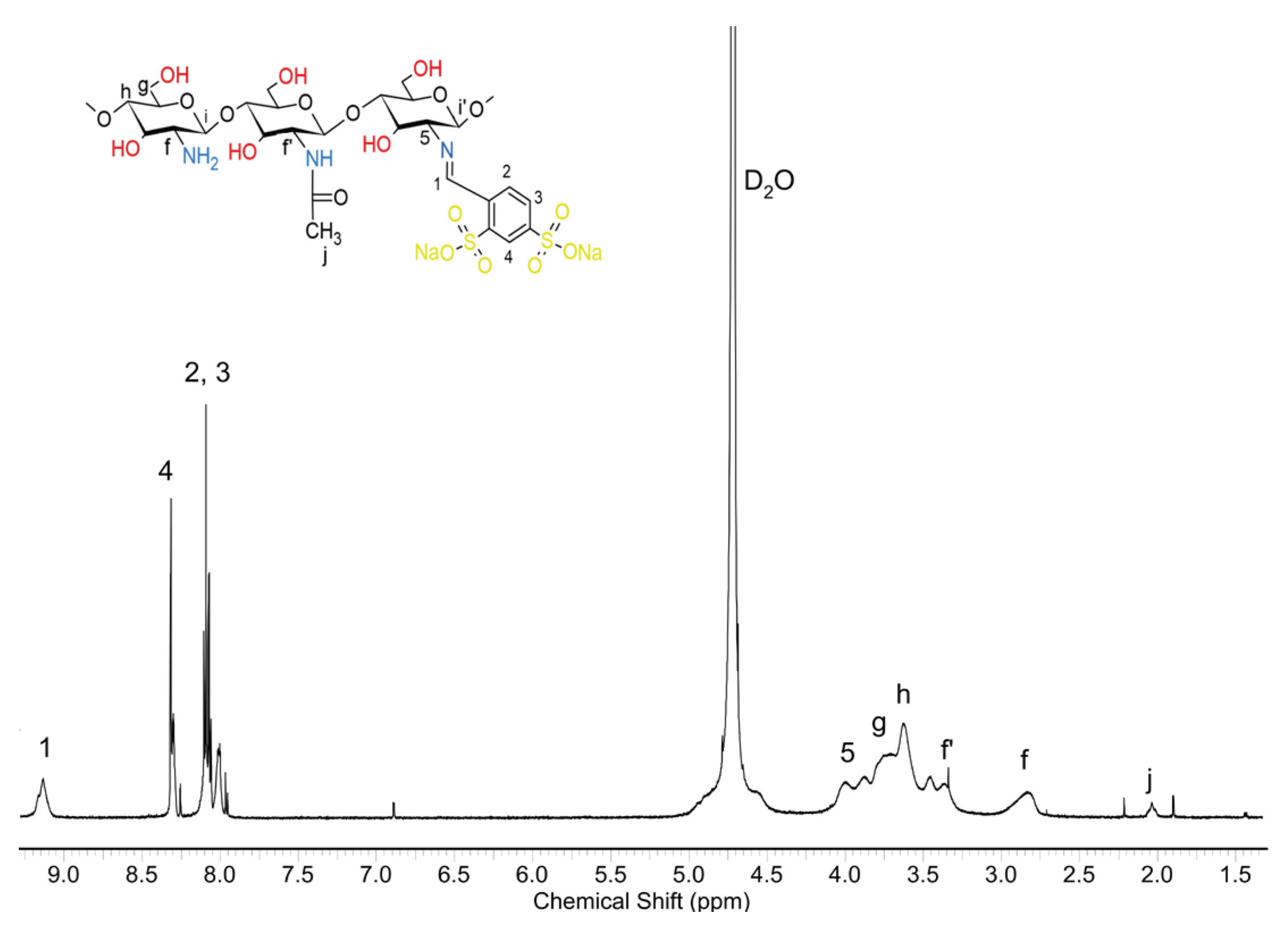

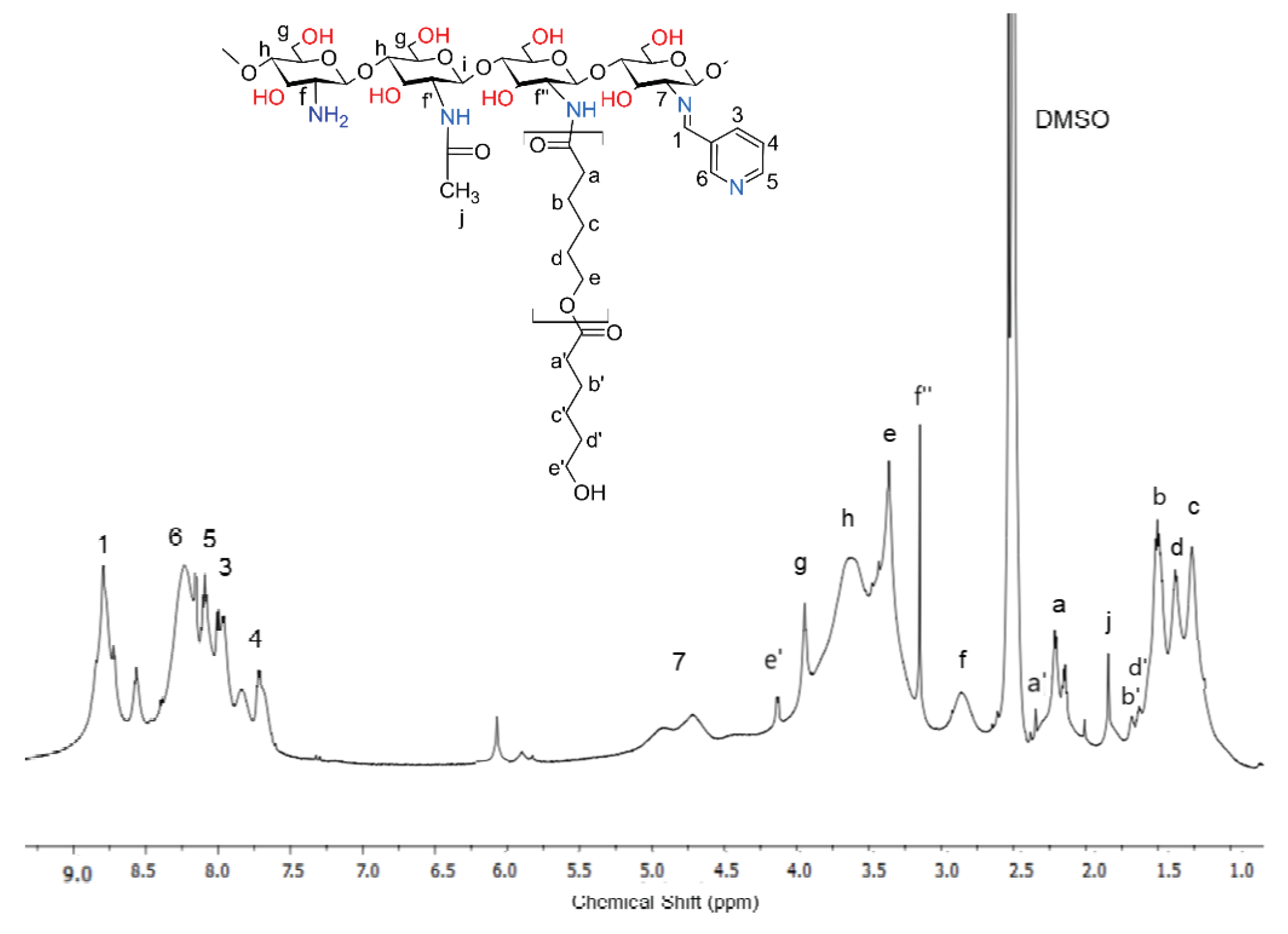

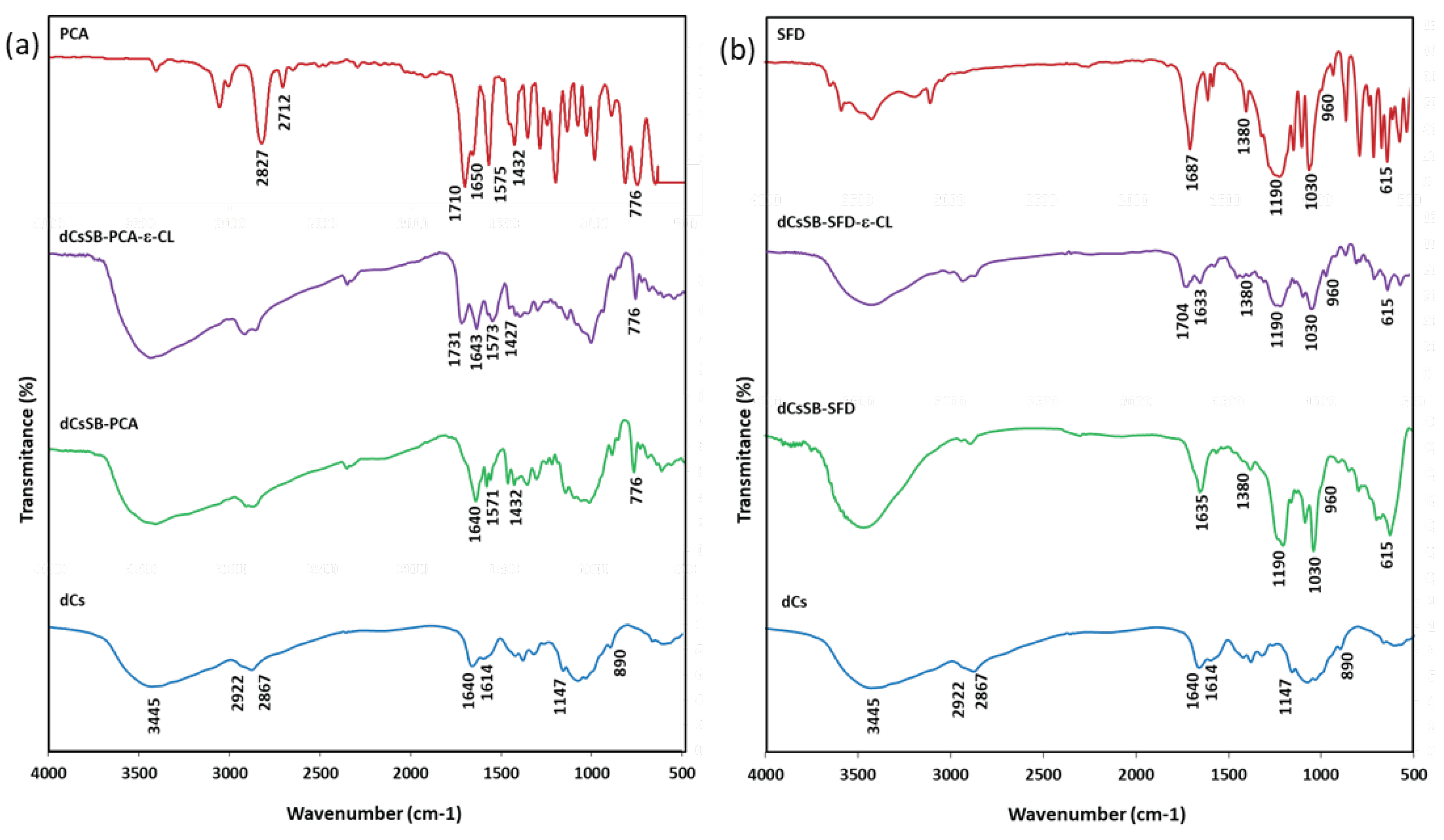

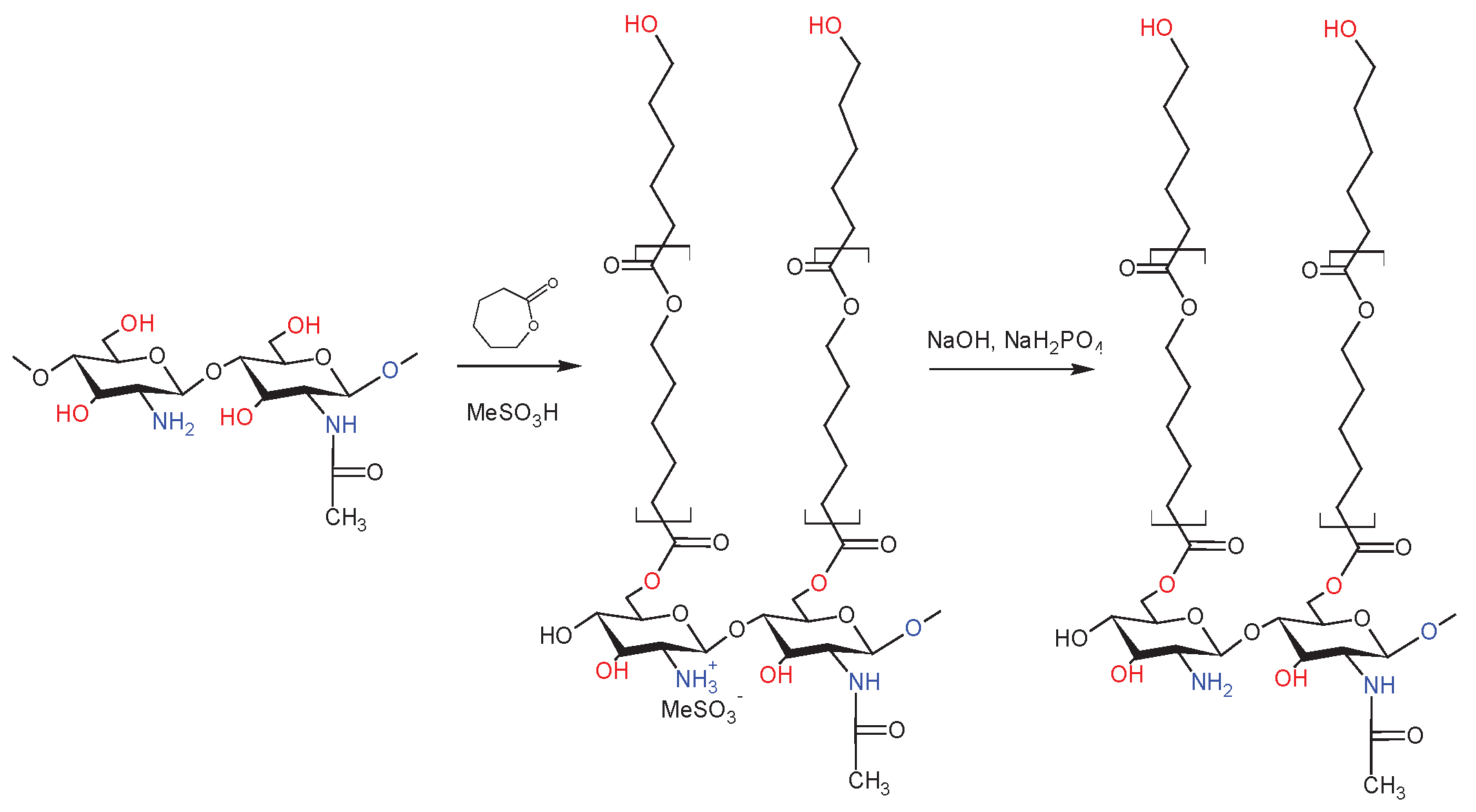

2.3. Chemical Structure of Schiff Base dCsSB-PCA; dCsSB-SFD and Copolymers dCsSB-PCA-ε-CL; dCsSB-SFD-ε-CL

2.4. Hydrogel Blends with Carrageenan, Swelling Properties

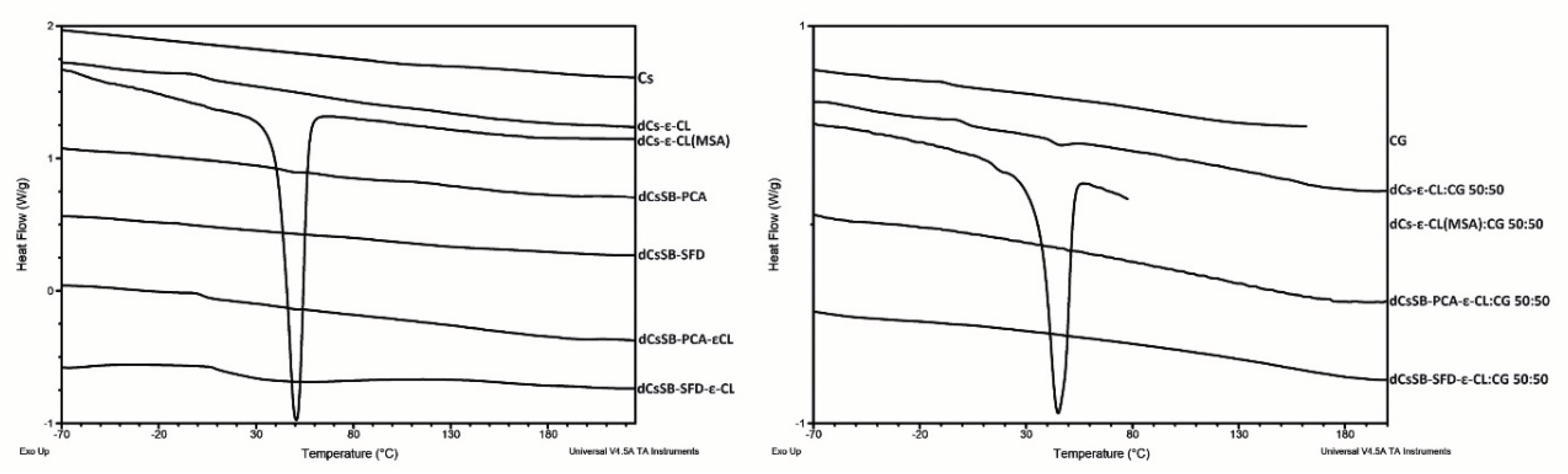

2.5. Thermal Properties

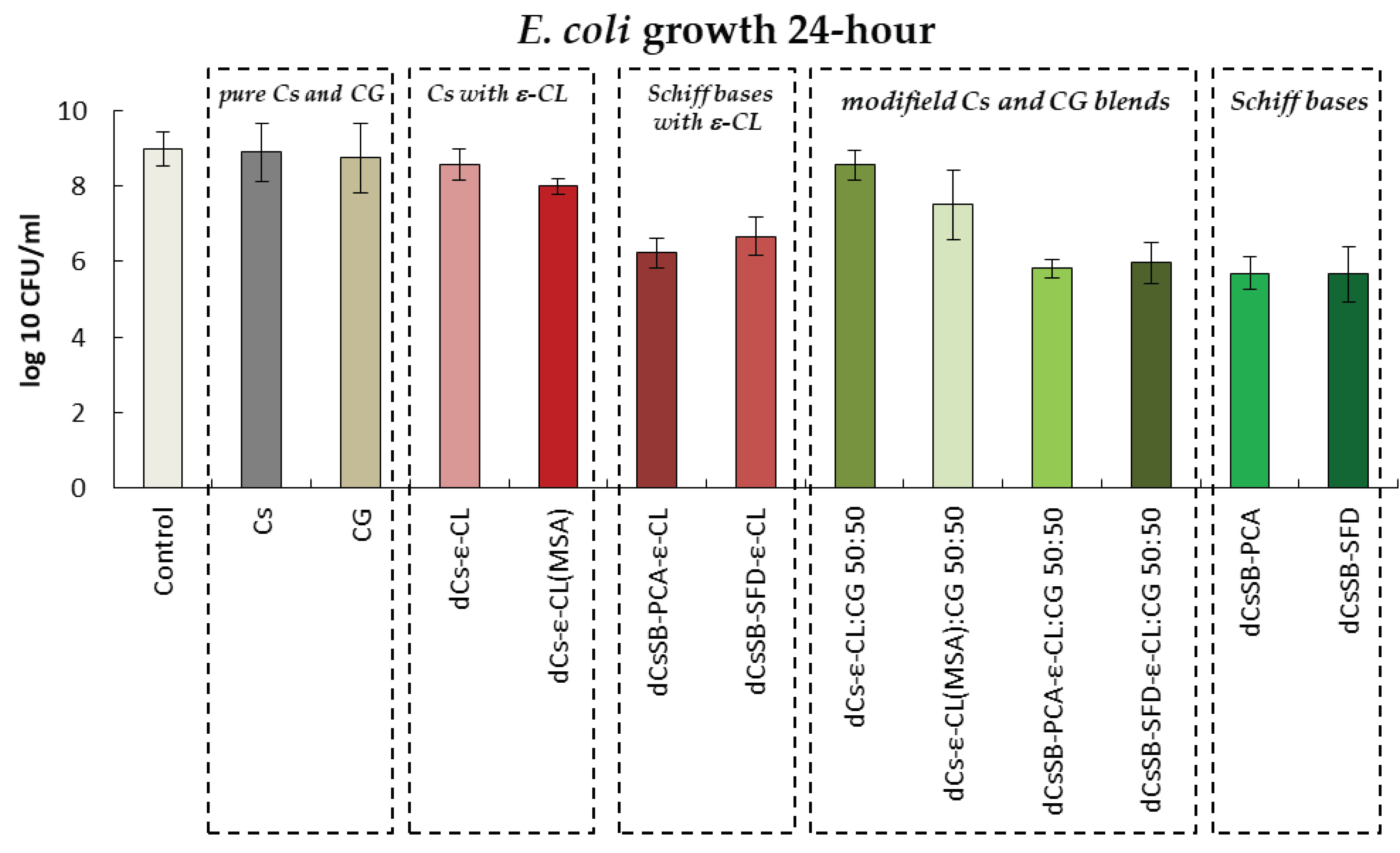

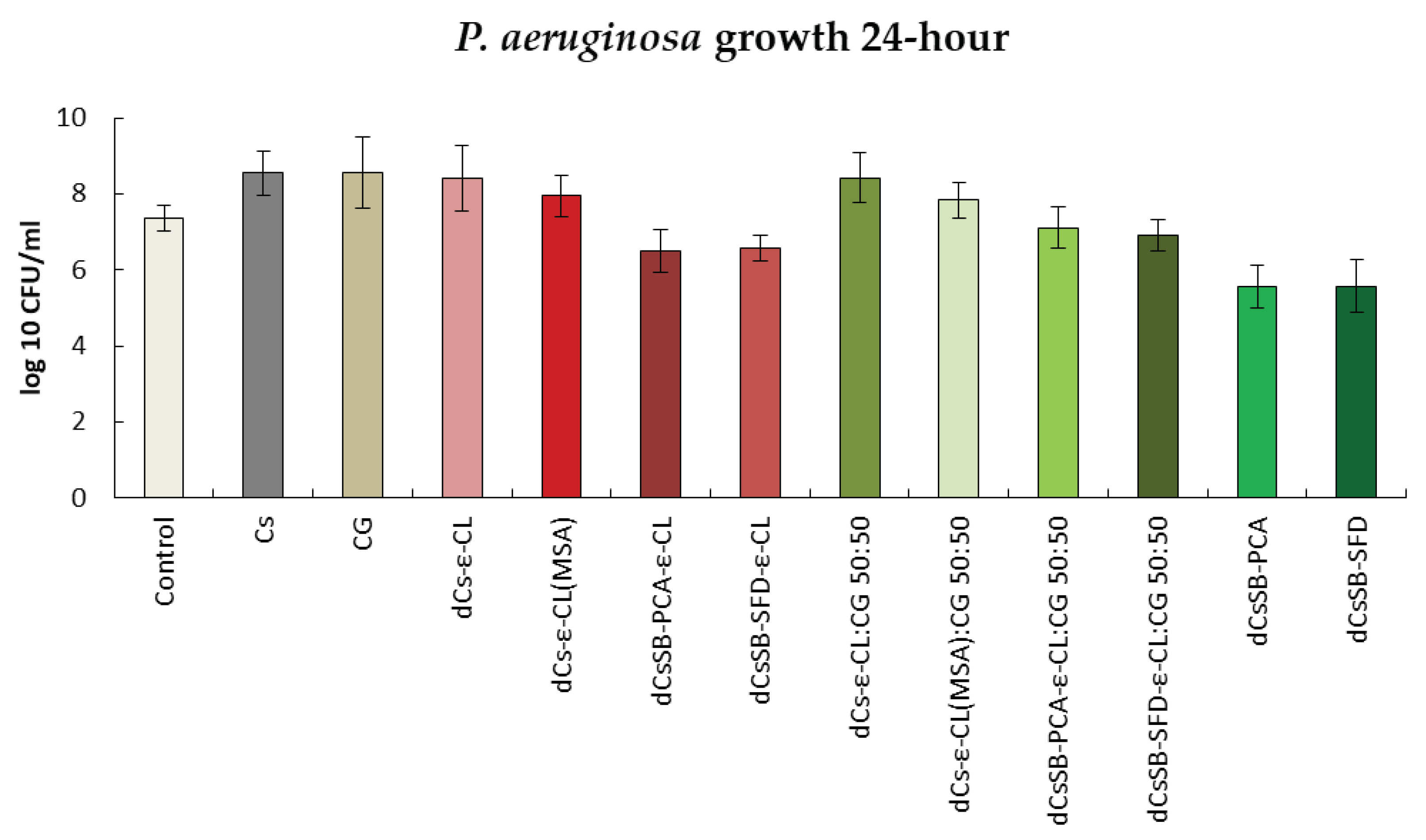

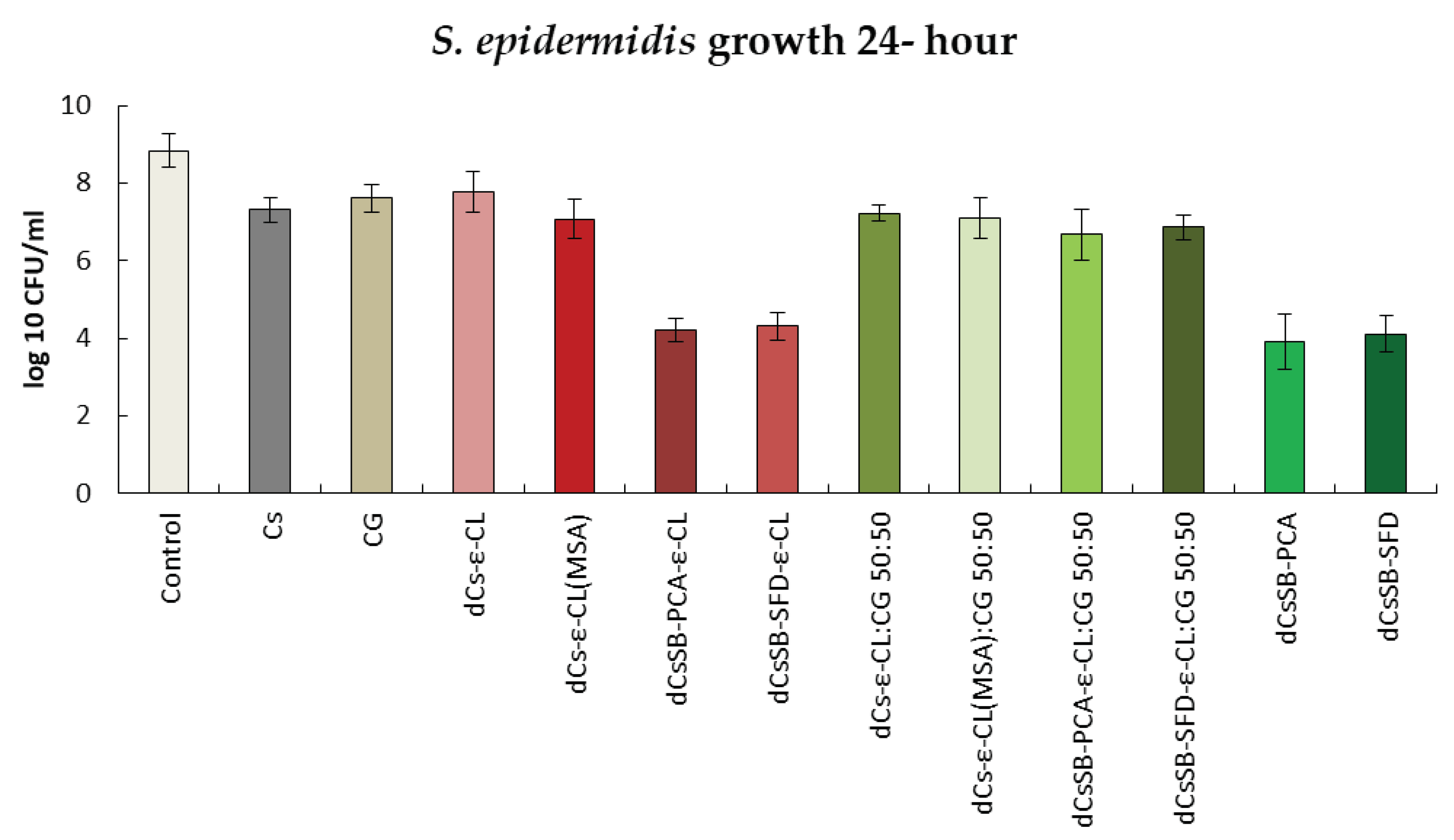

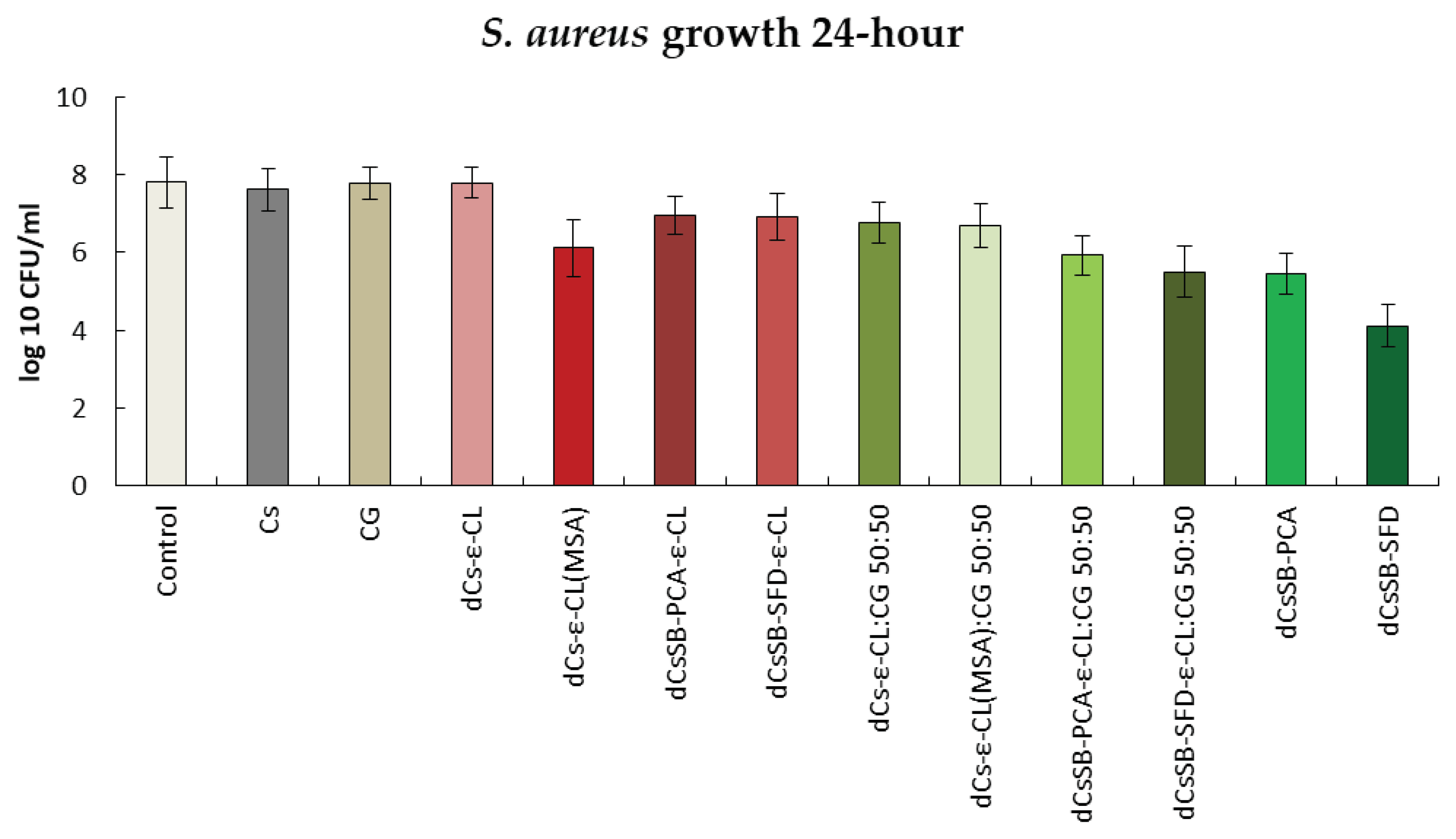

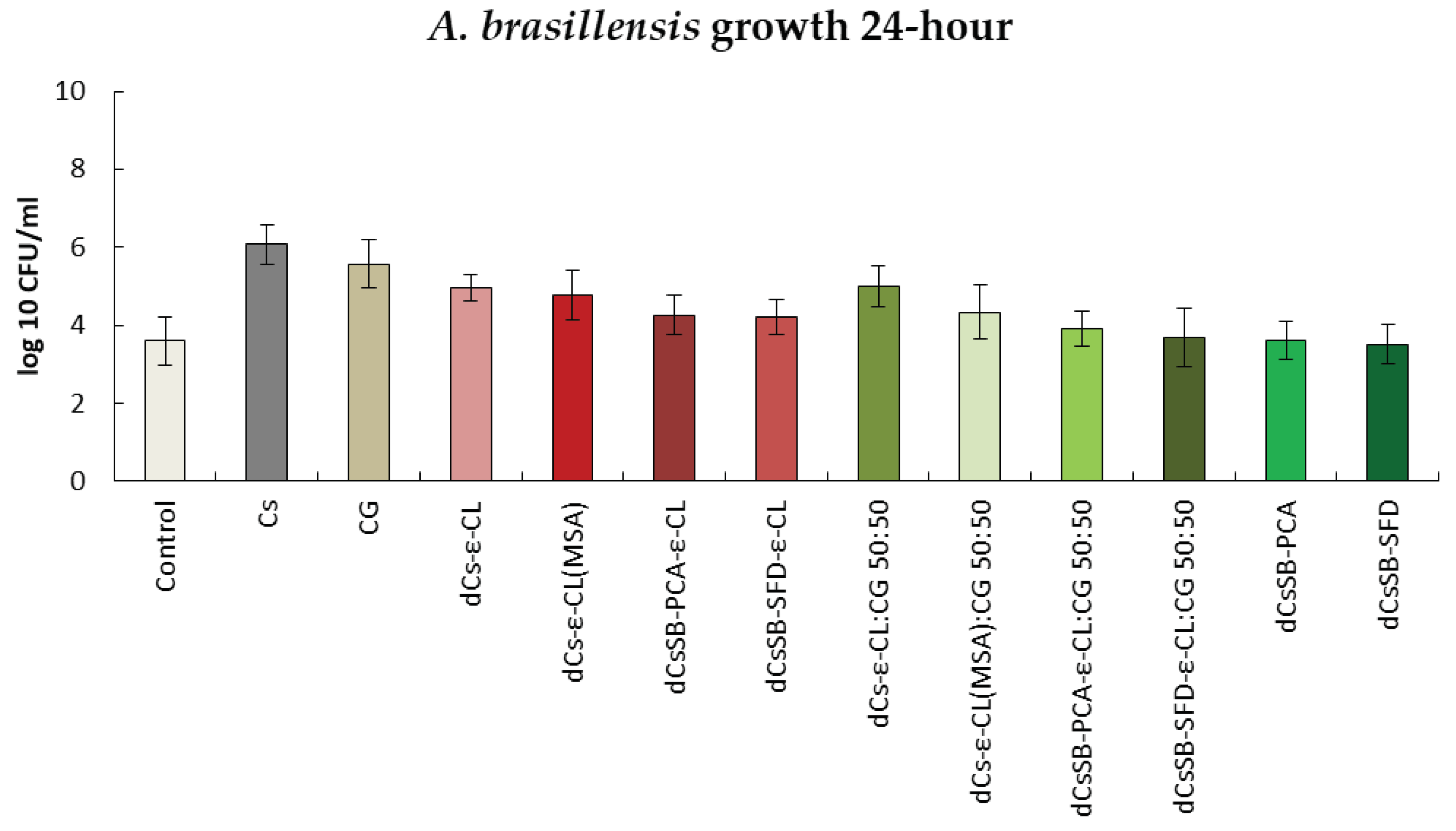

2.6. Antibacterial and Antifungal Evaluation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Solutions

4.2. The Strains and Substrates for Culture

4.3. N-Deacetylation of Chitosan

4.4. Synthesis of the dCs-ε-CL Copolymer

4.5. Synthesis of the dCs-ε-CL (MSA) Copolymer

4.6. Synthesis of the Schiff Base – dCsSB-PCA

4.7. Synthesis of the Schiff Base – dCsSB-SFD

4.8. Synthesis of the dCsSB-PCA-ε-CL and dCsSB-SFD-ε-CL

4.9. Preparation of the Cs and CG Blends

4.10. Characterization Methods

4.10.1. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H-NMR) Spectroscopy

4.10.2. Determination of Viscosity and Molecular Weight

4.10.3. Thermal Properties

4.10.4. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

4.10.5. Swelling Ratio

4.10.6. Antibacterial and Antifungal Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olmos, D.; González-Benito, J. Polymeric Materials with Antibacterial Activity: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smola-Dmochowska, A.; Lewicka, K.; Macyk, A.; Rychter, P.; Pamuła, E.; Dobrzyński, P. Biodegradable Polymers and Polymer Composites with Antibacterial Properties. IJMS 2023, 24, 7473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghalei, S.; Handa, H. A Review on Antibacterial Silk Fibroin-Based Biomaterials: Current State and Prospects. Materials Today Chemistry 2022, 23, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dai, F.; Yuan, M.; Wang, F.; Bai, Y.; Deng, H. Natural Polysaccharides Based Self-Assembled Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications – A Review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 192, 1240–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychter, P.; Christova, D.; Lewicka, K.; Rogacz, D. Ecotoxicological Impact of Selected Polyethylenimines toward Their Potential Application as Nitrogen Fertilizers with Prolonged Activity. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychter, P.; Rogacz, D.; Lewicka, K.; Lacik, I. Poly(Methylene-Co-Cyanoguanidine) as an Eco-Friendly Nitrogen Fertilizer with Prolonged Activity. J Polym Environ 2019, 27, 1317–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Li, P.; Wang, K.; Fang, L.; Ren, F.; Lu, G.; Lu, X. The Interaction of Chitosan and BMP-2 Tuned by Deacetylation Degree and pH Value. J Biomedical Materials Res 2019, 107, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz Rajoka, M.S.; Mehwish, H.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Arfat, Y.; Majeed, K.; Anwaar, S. Chitin/Chitosan Derivatives and Their Interactions with Microorganisms: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020, 40, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi Shariat Panahi, H.; Dehhaghi, M.; Amiri, H.; Guillemin, G.J.; Gupta, V.K.; Rajaei, A.; Yang, Y.; Peng, W.; Pan, J.; Aghbashlo, M.; et al. Current and Emerging Applications of Saccharide-Modified Chitosan: A Critical Review. Biotechnology Advances 2023, 66, 108172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Si, Z.; Yang, Z. 2-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde-Modified Chitosan–Silver Complexes: Optimized Preparation, Characterization, and Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, M.; Wen, T.; Wang, J.; Guo, R.; Liu, H. Preparation and Application of Quaternized Chitosan- and AgNPs-Base Synergistic Antibacterial Hydrogel for Burn Wound Healing. Molecules 2021, 26, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, N.; Lunkov, A.; Shagdarova, B.; Il’ina, A.; Varlamov, V. New N-Methylimidazole-Functionalized Chitosan Derivatives: Hemocompatibility and Antibacterial Properties. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, R.; Arun, T.; Manickam, S.T.D. A Review on Applications of Chitosan-Based Schiff Bases. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 129, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughnia, A.; Khalaji, A.D.; Kolvari, E.; Koukabi, N. Synthesis of New Chitosan Schiff Base and Its Fe2O3 Nanocomposite: Evaluation of Methyl Orange Removal and Antibacterial Activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 177, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.F.G.; Attjioui, M.; Leitão, A.; Moerschbacher, B.M.; Cavalheiro, É.T.G. Characterization, Solubility and Biological Activity of Amphihilic Biopolymeric Schiff Bases Synthesized Using Chitosans. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 220, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Chen, J.; Yuan, W.; Lin, Q.; Ji, L.; Liu, F. Preparation and Antibacterial Activity of Schiff Bases from O-Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Para-Substituted Benzaldehydes. Polym. Bull. 2012, 68, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavalyan, V.B. Synthesis and Characterization of New Chitosan-Based Schiff Base Compounds. Carbohydrate Polymers 2016, 145, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.; Attjioui, M.; Ferreira, A.; Dockal, E.; El Gueddari, N.; Moerschbacher, B.; Cavalheiro, É. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activities of Biopolymeric Schiff Bases Prepared with Chitosan and Salicylaldehydes and Their Pd(II) and Pt(II) Complexes. Molecules 2017, 22, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normi, N.I.; Abdulhameed, A.S.; Jawad, A.H.; Surip, S.N.; Razuan, R.; Ibrahim, M.L. Hydrothermal-Assisted Grafting of Schiff Base Chitosan by Salicylaldehyde for Adsorptive Removal of Acidic Dye: Statistical Modeling and Adsorption Mechanism. J Polym Environ 2023, 31, 1925–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, S.; Arora, S.; Kumar, V.; Rani, S.; Sharma, C.; Kumar, P. Thermal and Biological Studies of Schiff Bases of Chitosan Derived from Heteroaryl Aldehydes. J Therm Anal Calorim 2018, 132, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, J. Preparation, Characterization and Magnetic Properties of the BaFe12O19 @ Chitosan Composites. Solid State Sciences 2016, 57, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakeel, K.Z.; El-Bindary, A.A.; Ismail, A.; Morshidy, A.M. Magnetic Chitosan Grafted with Polymerized Thiourea for Remazol Brilliant Blue R Recovery: Effects of Uptake Conditions. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2017, 38, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.-J.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, J.W.; Kimura, S.; Wada, M. Cellulose-Chitosan Beads Crosslinked by Dialdehyde Cellulose. Cellulose 2017, 24, 5517–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low Molecular Weight Chitosan-Based Schiff Bases: Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity Available online:. Available online: https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=ajft.2013.17.30 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Pawariya, V.; De, S.; Dutta, J. Synthesis and Characterization of a New Developed Modified-Chitosan Schiff Base with Improved Antibacterial Properties for the Removal of Bismarck Brown R and Eosin Y Dyes from Wastewater. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2023, 6, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhang, J.; Tan, W.; Wang, G.; Li, Q.; Dong, F.; Guo, Z. Antifungal Activity of Double Schiff Bases of Chitosan Derivatives Bearing Active Halogeno-Benzenes. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 179, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Qin, Y.; Liu, S.; Xing, R.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Li, K.; Li, P. Synthesis, Characterization, and Antifungal Evaluation of Diethoxyphosphoryl Polyaminoethyl Chitosan Derivatives. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 190, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, A.M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; El-Fakharany, E.M.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Ismail, M.M.F.; Mohy-Eldin, M.S.; Ayoup, M.S. Novel Cytocompatible Chitosan Schiff Base Derivative as a Potent Antibacterial, Antidiabetic, and Anticancer Agent. Arab J Sci Eng 2023, 48, 7587–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.A.; Ismail, M.M.; Morsy, J.M.; Hassanin, H.M.; Abdelrazek, M.M. Synthesis, Characterization, Anticancer, and Antioxidant Activities of Chitosan Schiff Bases Bearing Quinolinone or Pyranoquinolinone and Their Silver Nanoparticles Derivatives. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 4035–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Gihar, S.; Shrivash, M.K.; Kumar, P.; Kundu, P.P. A Review on the Synthesis of Graft Copolymers of Chitosan and Their Potential Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 163, 2097–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Dong, C.-M. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan- Graft -Poly (ϵ-Caprolactone) with an Organic Catalyst. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 5353–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliva, M.; Georgopoulou, A.; Dragatogiannis, D.A.; Charitidis, C.A.; Chatzinikolaidou, M.; Vamvakaki, M. Biodegradable Chitosan-Graft-Poly(l-Lactide) Copolymers For Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2020, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Qi, H.; Yao, C.; Feng, M.; Dong, A. Investigation on the Properties of Methoxy Poly(Ethylene Glycol)/Chitosan Graft Co-Polymers. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 2007, 18, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Quan, D.; Shuai, X.; Liao, K.; Mai, K. Chitosan- Graft -poly(Ε-caprolactone)s: An Optimized Chemical Approach Leading to a Controllable Structure and Enhanced Properties. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 2556–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Chen, H.; Huang, J.; Yu, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. One-Step Synthesis of Amino-Reserved Chitosan-Graft-Polycaprolactone as a Promising Substance of Biomaterial. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 80, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Dong, L.; Cheung, M.K. Preparation and Characterization of Biodegradable Poly(l-Lactide)/Chitosan Blends. European Polymer Journal 2005, 41, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokmabad, V.R.; Davaran, S.; Aghazadeh, M.; Alizadeh, E.; Salehi, R.; Ramazani, A. A Comparison of the Effects of Silica and Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles on Poly(ε-Caprolactone)-Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Poly(ε-Caprolactone)/Chitosan Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2018, 15, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, V.L.; Kawano, D.F.; Silva, D.B. da; Carvalho, I. Carrageenans: Biological Properties, Chemical Modifications and Structural Analysis – A Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 2009, 77, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Osorio, Z.; Ruther, F.; Chen, S.; Sengupta, S.; Liverani, L.; Michálek, M.; Galusek, D.; Boccaccini, A.R. Environmentally Friendly Fabrication of Electrospun Nanofibers Made of Polycaprolactone, Chitosan and κ-Carrageenan (PCL/CS/κ-C). Biomed. Mater. 2022, 17, 045019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamtu, B.; Barbu, A.; Negrea, M.O.; Berghea-Neamțu, C. Ștefan; Popescu, D.; Zăhan, M.; Mireșan, V. Carrageenan-Based Compounds as Wound Healing Materials. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitura, S.; Sionkowska, A.; Jaiswal, A. Biopolymers for Hydrogels in Cosmetics: Review. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2020, 31, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Lee, D.S. Biodegradable and Injectable Hydrogels in Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Chan, H.-P.; Chung, T.-W.; Shu, C.-W.; Chuang, K.-P.; Duh, T.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Tyan, Y.-C. Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, A. Ethanol–NaOH Solidification Method to Intensify Chitosan/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Attapulgite Composite Film. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 17775–17781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Y.-L.; Zhang, G.-L.; Hao, H.; Hou, H.-M.; Bi, J. Amino Carboxymethyl Chitosan//Dialdehyde Starch/Polyvinyl Alcohol Double-Layer Film Loaded with ε-Polylysine. Food Chemistry 2023, 428, 136775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Ryu, J.; Song, G.; Whang, M.; Kim, J. Network Structure and Enzymatic Degradation of Chitosan Hydrogels Determined by Crosslinking Methods. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 217, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatinia, Z.; Jalali, A.M. Chitosan-Based Hydrogels: Preparation, Properties and Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 115, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gels | Free Full-Text | Recent Development of Functional Chitosan-Based Hydrogels for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications Available online:. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2310-2861/9/4/277 (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Liang, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Lu, A.; Zhang, L. Rubbery Chitosan/Carrageenan Hydrogels Constructed through an Electroneutrality System and Their Potential Application as Cartilage Scaffolds. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjavadi, A.; Doroudian, M.; Ahadpour, A.; Azari, S. Injectable Chitosan/κ-Carrageenan Hydrogel Designed with Au Nanoparticles: A Conductive Scaffold for Tissue Engineering Demands. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 126, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.M.; Hashem, A.H.; Kamel, S. Bimetallic Hydrogels Based on Chitosan and Carrageenan as Promising Materials for Biological Applications. Biotechnology Journal 2023, 18, 2300093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulos, A.; Nikolakis, S.-P.; Pamvouxoglou, A.; Koutsopoulou, E. Physicochemical Properties of Electrostatically Crosslinked Carrageenan/Chitosan Hydrogels and Carrageenan/Chitosan/Laponite Nanocomposite Hydrogels. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 225, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga, L.Y.C.; Sabino, R.M.; Santos, E.C.G.; Popat, K.C.; Balaban, R. de C.; Kipper, M.J. Carboxymethyl-Kappa-Carrageenan: A Study of Biocompatibility, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 152, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Fang, Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan-Graft-Polycaprolactone Copolymers. European Polymer Journal - EUR POLYM J 2004, 40, 2739–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckachan, G.E.; Pillai, C.K.S. Chitosan/Oligo L-Lactide Graft Copolymers: Effect of Hydrophobic Side Chains on the Physico-Chemical Properties and Biodegradability. Carbohydrate Polymers 2006, 64, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, C.; Zheng, K.; Luo, Y.; Dong, Y.; Shen, Z.; Li, W.; Qin, C. Preparation of Modified Chitosan Microsphere-Supported Copper Catalysts for the Borylation of α,β-Unsaturated Compounds. Polymers 2019, 11, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, F.J.; Kamal, F.; Gaucher, A.; Gil, R.; Bourdreux, F.; Martineau-Corcos, C.; Gurgel, L.V.A.; Gil, L.F.; Prim, D. Synthesis, Characterisation and Application of Pyridine-Modified Chitosan Derivatives for the First Non-Racemic Cu-Catalysed Henry Reaction. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 181, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, S.; Kakanejadifard, A. Modification of Chitosan and Chitosan Nanoparticle by Long Chain Pyridinium Compounds: Synthesis, Characterization, Antibacterial, and Antioxidant Activities. Carbohydrate Polymers 2019, 208, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, I.; Sellimi, S.; Rinaudo, M.; Jellouli, K.; Nasri, M. Influence of Acetylation Degree and Molecular Weight of Homogeneous Chitosans on Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2014, 185, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavertu, M.; Xia, Z.; Serreqi, A.N.; Berrada, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Wang, D.; Buschmann, M.D.; Gupta, A. A Validated 1H NMR Method for the Determination of the Degree of Deacetylation of Chitosan. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2003, 32, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, D.P.; Inamdar, M.S. Aqueous Behaviour of Chitosan. International Journal of Polymer Science 2010, 2010, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Xing, K.; Park, H.J. Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan and Mode of Action: A State of the Art Review. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2010, 144, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczyńska-Felusiak, R.; Pastusiak, M.; Rychter, P.; Kaczmarczyk, B.; Sobota, M.; Wanic, A.; Kaps, A.; Jaworska-Kik, M.; Orchel, A.; Dobrzyński, P. Synthesis of the Bacteriostatic Poly(l-Lactide) by Using Zinc (II)[(Acac)(L)H2O] (L = Aminoacid-Based Chelate Ligands) as an Effective ROP Initiator. IJMS 2021, 22, 6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworska, J.; Sobota, M.; Pastusiak, M.; Kawalec, M.; Janeczek, H.; Rychter, P.; Lewicka, K.; Dobrzyński, P. Synthesis of Polyacids by Copolymerization of L-Lactide with MTC-COOH Using Zn[(Acac)(L)H2O] Complex as an Initiator. Polymers 2022, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cassan, D.; Sydow, S.; Schmidt, N.; Behrens, P.; Roger, Y.; Hoffmann, A.; Hoheisel, A.L.; Glasmacher, B.; Hänsch, R.; Menzel, H. Attachment of Nanoparticulate Drug-Release Systems on Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Nanofibers via a Graftpolymer as Interlayer. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2018, 163, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.-J.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Cao, X.-H.; Zhang, X.-H. Synthesis of High-Molecular-Weight Poly(ε-Caprolactone) via Heterogeneous Zinc-Cobalt(III) Double Metal Cyanide Complex. Giant 2020, 3, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, B.; Zou, L.; Sun, C.; Li, W. Preparation and Characterization of PLLA/Chitosan-Graft-Poly (ε-Caprolactone) (CS-g-PCL) Composite Fibrous Mats: The Microstructure, Performance and Proliferation Assessment. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 162, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïdi, F.; Taulelle, F.; Martineau, C. Quantitative (13)C Solid-State NMR Spectra by Multiple-Contact Cross-Polarization for Drug Delivery: From Active Principles to Excipients and Drug Carriers. J Pharm Sci 2016, 105, 2397–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Liu, P.; Baker, G.L. Sulfonated Polyimide and PVDF Based Blend Proton Exchange Membranes for Fuel Cell Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 3847–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinia, G.R.; Karimi, M.H.; Soltaniniya, M.; Massoumi, B. In Vitro Evaluation of Sustained Ciprofloxacin Release from κ-Carrageenan-Crosslinked Chitosan/Hydroxyapatite Hydrogel Nanocomposites. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 126, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Wang, Z. Tailoring the Swelling-Shrinkable Behavior of Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2303326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohindra, D.R.; Nand, A.V.; Khurma, J.R. Swelling Properties of Chitosan Hydrogels. S. Pac. J. Nat. App. Sci. 2004, 22, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, F.Z.K. , Wiratni Budhijanto, Eko Purnomo, Prihati Sih Optimization Concentration of Irgacure® 2959 as Photo-Initiator on Chitosan-Kappa-Carrageenan Based Hydrogel for Tissue Sealant Available online:. Available online: https://ijtech.eng.ui.ac.id/article/view/6166 (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Yegappan, R.; Selvaprithiviraj, V.; Amirthalingam, S.; Jayakumar, R. Carrageenan Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery, Tissue Engineering and Wound Healing. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 198, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ili Balqis, A.M.; Nor Khaizura, M.A.R.; Russly, A.R.; Nur Hanani, Z.A. Effects of Plasticizers on the Physicochemical Properties of Kappa-Carrageenan Films Extracted from Eucheuma Cottonii. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 103, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebi, H.; Kurt, A. Effects of Processing on the Properties of Chitosan/Cellulose Nanocrystal Films. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 133, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Camacho, A.P.; Cortez-Rocha, M.O.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.Z.; Rodriguez-Félix, F.; Castillo-Ortega, M.M.; Yépiz-Gómez, M.S.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M. Chitosan Composite Films: Thermal, Structural, Mechanical and Antifungal Properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2010, 82, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhu, B.; Inoue, Y. Hydrogen Bonds in Polymer Blends. Progress in Polymer Science 2004, 29, 1021–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Lu, T.; Yuasa, S.; Yamaura, K. Structure and Properties of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Κ-carrageenan Blends. Polymer International 2001, 50, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmed, A.A.; Sofy, A.R.; Sharaf, A.E.-M.M.A.; El-Dougdoug, K.A. Effectiveness of Chitosan as Naturally-Derived Antimicrobial to Fulfill the Needs of Today’s Consumers Looking for Food without Hazards of Chemical Preservatives. Journal of Microbiology Research 2017, 7, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ashry, N.M.; El Bahgy, H.E.K.; Mohamed, A.; Alsubhi, N.H.; Alrefaei, G.I.; Binothman, N.; Alharbi, M.; Selim, S.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Alharbi, M.T.; et al. Evaluation of Graphene Oxide, Chitosan and Their Complex as Antibacterial Agents and Anticancer Apoptotic Effect on HeLa Cell Line. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laokuldilok, T.; Potivas, T.; Kanha, N.; Surawang, S.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Wangtueai, S.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Regenstein, J.M. Physicochemical, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Properties of Chitooligosaccharides Produced Using Three Different Enzyme Treatments. Food Bioscience 2017, 18, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeltwab, W.; Fathy, Y.; Azab, W.; Eldeghedy, M.; Ebid, W. Antimicrobial Effect of Chitosan and Nano-Chitosan against Some Pathogens and Spoilage Microorganisms. 2019.

- Zhu, M.; Ge, L.; Lyu, Y.; Zi, Y.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Mu, C. Preparation, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Oxidized κ-Carrageenan. Carbohydr Polym 2017, 174, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, D.; Bauer, M.; Frączyk, J.; Draczyński, Z. Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Modified Chitosan Nonwovens. Polymers 2022, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirzaei Sani, I.; Rezaei, M.; Baradar Khoshfetrat, A.; Razzaghi, D. Preparation and Characterization of Polycaprolactone/Chitosan-g-Polycaprolactone/Hydroxyapatite Electrospun Nanocomposite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 182, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, M.; A. Abu-Saied, M.; H. Taha, T.; Elnouby, M.; A. El Desouky, E.; Alamri, S.; Shati, A.; Alrumman, S.; Alghamdii, H.; Al-Khatani, M.; et al. Preparation and Characterization of Super-Absorbing Gel Formulated from κ-Carrageenan–Potato Peel Starch Blended Polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, J.S.; Weinstein, M.P.; Bobenchik, A.M.; Campeau, S.; Cullen, S.K.; Galas, M.F.; Gold, H.; Humphries, R.M.; Kirn, T.J.; Limbago, B.; et al. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 32nd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | DDA [%] | Intrinsic viscosity [dL/g] | Molecular weight Mv [g/mol] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cs | 85 | 7.7 | 514 400 |

| dCS | 96 | 7.5 | 498 300 |

| Sample | Tg [°C] | Tm [°C] | ΔH [J/g] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 88.2 | - | - |

| Cs | 173.0 | - | - |

| dCs-ε-CL | -45.9 / 144.7 | - | - |

| dCs-ε-CL(MSA) | - | 50.6 | 72.9 |

| dCsSB-PCA | 141.4 | - | - |

| dCsSB-SFD | 102.4 | - | - |

| dCsCB-PCA-ε-CL | -38.2 / 143.6 | - | - |

| dCsCB-SFD-ε-CL | 20.4 / 154.4 | - | - |

| dCs-ε-CL: CG 50:50 | -46.23 / 157.8 | - | - |

| dCs-ε-CL(MSA):CG 50:50 | - | 45.0 | 42.9 |

| dCsCB-PCA-ε-CL: CG 50:50 | 124.1 | - | - |

| dCsCB-SFD-ε-CL: CG 50:50 | -62.2 / 146.7 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).