Submitted:

21 March 2024

Posted:

22 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knight M, Bunch K, Vousden N, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women admitted to hospital with confirmed SARS- CoV-2 infection in UK: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2107. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Perez, O., Prats Rodriguez, P., Muner Hernandez, M., Encinas Pardilla, M. B., Perez Perez, N., Vila Hernandez, M. R., Villalba Yarza, A., Nieto Velasco, O., Del Barrio Fernandez, P. G., Forcen Acebal, L., Orizales Lago, C. M., Martinez Varea, A., Muñoz Abellana, B., Suarez Arana, M., Fuentes Ricoy, L., Martinez Diago, C., Janeiro Freire, M. J., Alférez Alvarez-Mallo, M., Casanova Pedraz, C., Alomar Mateu, O., Spanish Obstetric Emergency Group (2021). The association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and preterm delivery: a prospective study with a multivariable analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 21(1), 273. [CrossRef]

- Al-Matary, A., Almatari, F., Al-Matary, M., AlDhaefi, A., Alqahtani, M. H. S., Alhulaimi, E. A., AlOtaiby, S., Almehiny, K., John, L. S., Alanazi, F. S., Ali, A. M., & Aldandan, F. K. (2021). Clinical outcomes of maternal and neonate with COVID-19 infection - Multicenter study in Saudi Arabia. Journal of infection and public health, 14(6), 702–708. [CrossRef]

- Ayed, A., Embaireeg, A., Benawadh, A., Al-Fouzan, W., Hammoud, M., Al-Hathal, M., Alzaydai, A., Ahmad, A., & Ayed, M. Maternal and perinatal characteristics and outcomes of pregnancies complicated with COVID-19 in Kuwait. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Dec 2;20(1):754. [CrossRef]

- Figueiro-Filho EA, Yudin M, Farine D. COVID-19 during pregnancy: an overview of maternal characteristics, clinical symptoms, mater- nal and neonatal outcomes of 10,996 cases described in 15 coun- tries. J Perinat Med. 2020;48:900-911. [CrossRef]

- Allotey, J., Chatterjee, S., Kew, T., Gaetano, A., Stallings, E., Fernández-García, S., Yap, M., Sheikh, J., Lawson, H., Coomar, D., Dixit, A., Zhou, D., Balaji, R., Littmoden, M., King, Y., Debenham, L., Llavall, A. C., Ansari, K., Sandhu, G., Banjoko, A., PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium (2022). SARS-CoV-2 positivity in offspring and timing of mother-to-child transmission: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022 Mar 16:376:e067696. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Li, N., Sun, C., Guo, X., Su, W., Song, Q., Liang, Q., Liang, M., Ding, X., Lowe, S., Bentley, R., & Sun, Y. (2022). The association between pregnancy and COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of emergency medicine, 56, 188–195. [CrossRef]

- McClymont, E., Albert, A. Y., Alton, G. D., Boucoiran, I., Castillo, E., Fell, D. B., Kuret, V., Poliquin, V., Reeve, T., Scott, H., Sprague, A. E., Carson, G., Cassell, K., Crane, J., Elwood, C., Joynt, C., Murphy, P., Murphy-Kaulbeck, L., Saunders, S., Shah, P., CANCOVID-Preg Team (2022). Association of SARS-CoV-2 Infection During Pregnancy With Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes. JAMA, 327(20), 1983–1991. [CrossRef]

- Epelboin, S., Labrosse, J., De Mouzon, J., Fauque, P., Gervoise-Boyer, M. J., Levy, R., Sermondade, N., Hesters, L., Bergère, M., Devienne, C., Jonveaux, P., Ghosn, J., & Pessione, F. (2021). Obstetrical outcomes and maternal morbidities associated with COVID-19 in pregnant women in France: A national retrospective cohort study. PLoS medicine, 18(11), e1003857. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan NN, Pednekar R, Gaikwad C, More P, Pophalkar M, Kesarwani S, Jnanananda B, Mahale SD, Gajbhiye RK. Increased spontaneous preterm births during the second wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022 Apr;157(1):115-120. Epub 2021 Nov 5. PMID: 34674259; PMCID: PMC9087695. [CrossRef]

- Bahado-Singh, R., Tarca, A. L., Hasbini, Y. G., Sokol, R. J., Keerthy, M., Goyert, G., Jones, T., Thiel, L., Green, P., Youssef, Y., Townsel, C., Vengalil, S., Paladino, P., Wright, A., Ayyash, M., Vadlamud, G., Szymanska, M., Sajja, S., Turkoglu, O., Sterenberg, G. Southern Michigan Regional COVID-19 Collaborative (2023). Maternal SARS-COV-2 infection and prematurity: the Southern Michigan COVID-19 collaborative. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians, 36(1), 2199343. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, A., Hedderson, M. M., Zhu, Y., Avalos, L. A., Kuzniewicz, M. W., Myers, L. C., Ngo, A. L., Gunderson, E. P., Ritchie, J. L., Quesenberry, C. P., & Greenberg, M. (2022). Perinatal Complications in Individuals in California With or Without SARS-CoV-2 Infection During Pregnancy. JAMA internal medicine, 182(5), 503–512. [CrossRef]

- Smith LH, Dollinger CY, VanderWeele TJ, Wyszynski DF, Hernández-Díaz S. Timing and severity of COVID-19 during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth in the International Registry of Coronavirus Exposure in Pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):775. Published 2022 Oct 18. [CrossRef]

- Metz, T. D., Clifton, R. G., Hughes, B. L., Sandoval, G., Saade, G. R., Grobman, W. A., Manuck, T. A., Miodovnik, M., Sowles, A., Clark, K., Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., Mendez-Figueroa, H., Sehdev, H. M., Rouse, D. J., Tita, A. T. N., Bailit, J., Costantine, M. M., Simhan, H. N., Macones, G. A., & for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network (2021). Disease Severity and Perinatal Outcomes of Pregnant Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstetrics and gynecology, 137(4), 571–580. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, F., Oros, D., Gunier, R. B., Deantoni, S., Rauch, S., Casale, R., Nieto, R., Bertino, E., Rego, A., Menis, C., Gravett, M. G., Candiani, M., Deruelle, P., García-May, P. K., Mhatre, M., Usman, M. A., Abd-Elsalam, S., Etuk, S., Napolitano, R., Liu, B., Villar, J. (2022). Effects of prenatal exposure to maternal COVID-19 and perinatal care on neonatal outcome: results from the INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 227(3), 488.e1–488.e17. [CrossRef]

- Trahan, M. J., Malhamé, I., O'Farrell, P., Mitric, C., Desilets, J., Bastrash, M. P., El-Messidi, A., & Abenhaim, H. A. (2021). Obstetrical and Newborn Outcomes Among Patients With SARS-CoV-2 During Pregnancy. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC, 43(7), 888–892.e1. [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S., Carosso, A. R., Cusato, J., Borella, F., Carosso, M., Gervasoni, F., Stura, I., Preti, M., Ghisetti, V., Di Perri, G., & Benedetto, C. (2021). Preterm birth is not associated with asymptomatic/mild SARS-CoV-2 infection per se: Pre-pregnancy state is what matters. PloS one, 16(8), e0254875. [CrossRef]

- Bobei, T. I., Haj Hamoud, B., Sima, R. M., Gorecki, G. P., Poenaru, M. O., Olaru, O. G., & Ples, L. (2022). The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Premature Birth-Our Experience as COVID Center. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 58(5), 587. [CrossRef]

- Litman EA, Yin Y, Nelson SJ, Capbarat E, Kerchner D, Ahmadzia HK. Adverse perinatal outcomes in a large United States birth cohort during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4(3):100577. [CrossRef]

- Darling AM, Shephard H, Nestoridi E, Manning SE, Yazdy MM. SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and preterm birth in Massachusetts from March 2020 through March 2021. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2023;37(2):93-103. [CrossRef]

- Binte Masud, S., Zebeen, F., Alam, D. W., Hossian, M., Zaman, S., Begum, R. A., Nabi, M. H., & Hawlader, M. D. H. (2021). Adverse Birth Outcomes Among Pregnant Women With and Without COVID-19: A Comparative Study From Bangladesh. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi, 54(6), 422–430. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S., Tita, A. T., Varner, M., Stockwell, M. S., Newes-Adeyi, G., Battarbee, A. N., Reichle, L., Morrill, T., Daugherty, M., Mourad, M., Silverio Francisco, R. A., Woodworth, K., Wielgosz, K., Galang, R., Maniatis, P., Semenova, V., & Dawood, F. S. (2023). Association between SARS-CoV-2 infections during pregnancy and preterm live birth. Influenza and other respiratory viruses, 17(9), e13192. [CrossRef]

- Deruelle, P., & Sentilhes, L. (2021). Coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy was associated with maternal morbidity and preterm birth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 224(5), 551. [CrossRef]

- Vouga, M., Favre, G., Martinez-Perez, O., Pomar, L., Acebal, L. F., Abascal-Saiz, A., Hernandez, M. R. V., Hcini, N., Lambert, V., Carles, G., Sichitiu, J., Salomon, L., Stirnemann, J., Ville, Y., de Tejada, B. M., Goncé, A., Hawkins-Villarreal, A., Castillo, K., Solsona, E. G., Trigo, L., Panchaud, A. (2021). Maternal outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 severity among pregnant women. Scientific reports, 11(1), 13898. [CrossRef]

- Blitz MJ, Gerber RP, Gulersen M, Shan W, Rausch AC, Prasannan L, Meirowitz N, Rochelson B. Preterm birth among women with and without severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021 Dec;100(12):2253-2259. [CrossRef]

- Gulersen M, Alvarez A, Rochelson B, Blitz MJ. Preterm birth and severe maternal morbidity associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the Omicron wave. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022 Nov;4(6):100712. [CrossRef]

- Parasiliti M, Vidiri A, Perelli F, Scambia G, Lanzone A, Cavaliere AF. Cesarean section rate: navigating the gap between WHO recommended range and current obstetrical challenges. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023 Dec;36(2):2284112. [CrossRef]

- Gullo G, Cucinella G, Tumminello M, Renda B, Donzelli M, Lo Bue V, Termini D, Maranto M, De Tommasi O, Tarantino F. Convalescent plasma use in pregnant patients with COVID-19 related ARDS: a case report and literature review. Italian JOG. Vol. 34 (No. 3) 2022 September, 228-234. [CrossRef]

- Maranto M, Zaami S, Restivo V, Termini D, Gangemi A, Tumminello M, Culmone S, Billone V, Cucinella G, Gullo G. Symptomatic COVID-19 in Pregnancy: Hospital Cohort Data between May 2020 and April 2021, Risk Factors and Medicolegal Implications. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Mar 7;13(6):1009. [CrossRef]

- Egloff C, Roques P, Picone O. Impact of COVID-19 on pregnant women's health: Consequences in obstetrics two years after the pandemic. J Reprod Immunol. 2023 Aug;158:103981. [CrossRef]

- Hudak, ML. Consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the perinatal period. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021;33(2):181-187. [CrossRef]

- Uta M, Craina M, Marc F, Enatescu I. Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. 2024; 12(1):102. [CrossRef]

- Maranto M, Gullo G, Bruno A, Minutolo G, Cucinella G, Maiorana A, Casuccio A, Restivo V. Factors Associated with Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Acceptance among Pregnant Women: Data from Outpatient Women Experiencing High-Risk Pregnancy. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Feb 16;11(2):454. [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere AF, Zaami S, Pallottini M, Perelli F, Vidiri A, Marinelli E, Straface G, Signore F, Scambia G, Marchi L. Flu and Tdap Maternal Immunization Hesitancy in Times of COVID-19: An Italian Survey on Multiethnic Sample. Vaccines (Basel). 2021 Sep 29;9(10):1107. [CrossRef]

- Vilca LM, Sarno L, Cesari E, Vidiri A, Antonazzo P, Ravennati F, Cavaliere AF, Guida M, Cetin I. Differences between influenza and pertussis vaccination uptake in pregnancy: a multi-center survey study in Italy. Eur J Public Health. 2021 Dec 1;31(6):1150-1157. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Albezrah NKA, et al. Pregnancy and COVID-19: high or low risk of vertical transmission. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23(4):957-967. [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, P.; Maringanti, B.S.; Edwards-Fligner, M.; Gangu, K.; Bobba, A.; Sheikh, A.B.; Shekhar, R. Paxlovid (Nirmatrelvir and Ritonavir) Use in Pregnant and Lactating Woman: Current Evidence and Practice Guidelines—A Scoping Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinnetti, Carmela; Tintoni, Mauro; Ammassari, Adriana; Tamburrini, Enrica; Bernardi, Stefania; Liuzzi, Giuseppina; Scambia, Giovanni; Perno, Carlo Federico; Floridia, Marco; Antinori, Andrea; Cavaliere, Anna Franca (2015). Successful prevention of HIV mother-to-child transmission with dolutegravir-based combination antiretroviral therapy in a vertically infected pregnant woman with multiclass highly drug-resistant HIV-1. AIDS, 29(18), 2534–2537. [CrossRef]

- Marchi L, Vidiri A, Fera EA, Pallottini M, Perelli F, Gardelli M, Brunelli T, Poggetto PD, Martelli E, Straface G, Signore F, Fusco I, Vasarri PL, Scambia G, Cavaliere AF. SARS-CoV-2 IgG "heritage" in newborn: A credit of maternal natural infection. J Med Virol. 2023 Jan;95(1):e28133. [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere AF, Marchi L, Aquilini D, Brunelli T, Vasarri PL. Passive immunity in newborn from SARS-CoV-2-infected mother. J Med Virol. 2021 Mar;93(3):1810-1813. [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere AF, Carabaneanu AI, Perelli F, Matarrese D, Brunelli T, Casprini P, Vasarri PL. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women admitted for delivery: how to manage antibody testing? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022 Aug;35(15):3005-3006. [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere AF, Vasarri PL, Scatena E, Vidiri A, Santicchia MS, Bordoni Vicini I, Gardelli M, Bressan F, Matarrese D, Perelli F. SARS-CoV2 containment during pregnancy: single Center experience and the unique Chinese reality in Prato. Italian JOG. Vol. 32 (No. 3) 2020 September, 163-165. [CrossRef]

- Fratelli N, Prefumo F, Maggi C, Cavalli C, Sciarrone A, Garofalo A, Viora E, Vergani P, Ornaghi S, Betti M, Vaglio Tessitore I, Gullo, G.; Scaglione, M.; Cucinella, G.; Riva, A.; Coldebella, D.; Cavaliere, A.F.; Signore, F.; Buzzaccarini, G.; Spagnol, G.; Laganà, A.S.; et al. Congenital Zika Syndrome: Genetic Avenues for Diagnosis and Therapy, Possible Management and Long-Term Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1351. [CrossRef]

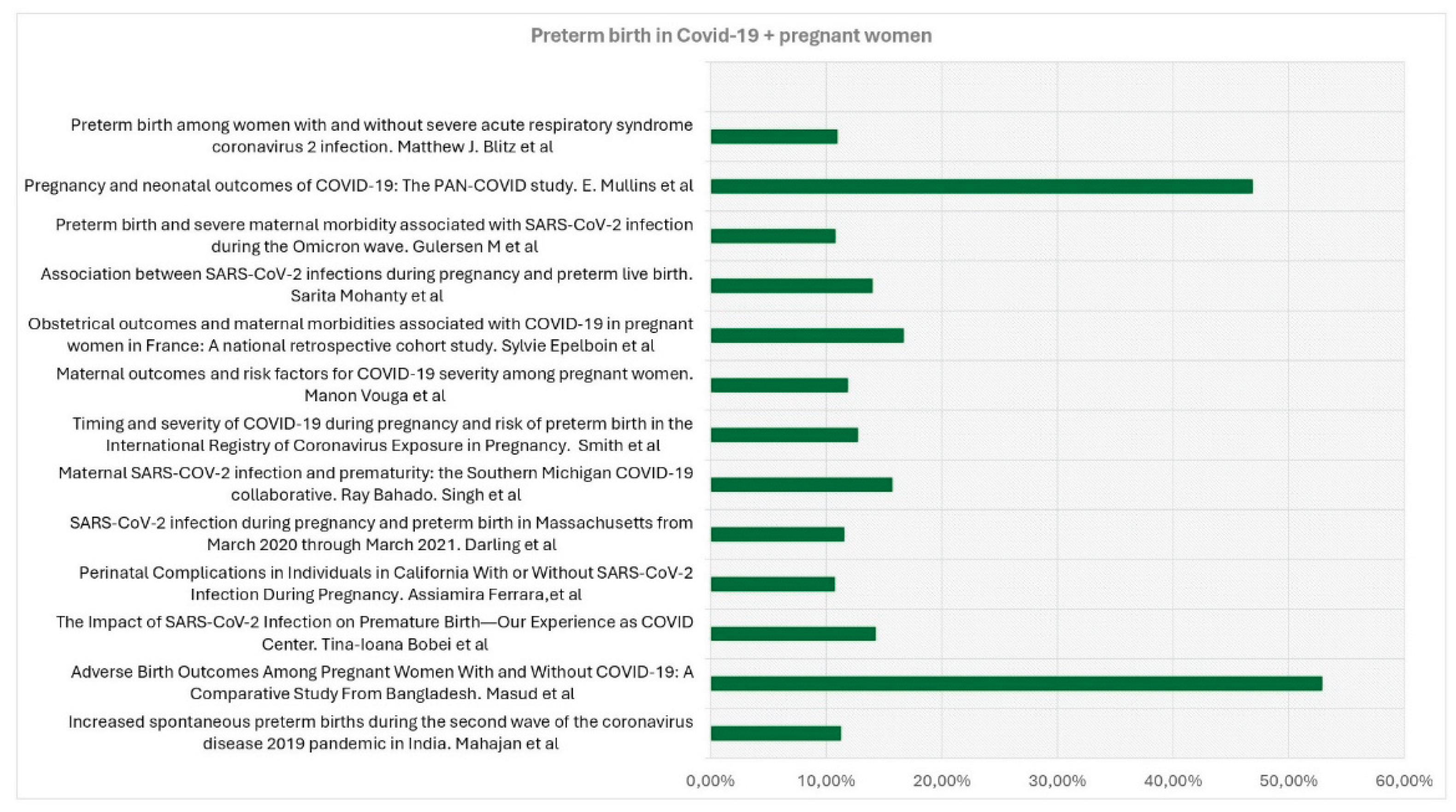

| Title, Authors | Country, duration of observation | Type of Study | Aim of the study | Covid + patients | Covid - patients | Preterm birth in Covid+ patients | Preterm Birth in Covid- patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetrical outcomes and maternalmorbidities associated with COVID-19 inpregnant women in France: A nationalretrospective cohort study -Epelboin et al [9] | France. January to June 2020 | Prospective Cohort Multicentric Study | Investigation on whether maternal morbidities were more frequent in pregnant women with COVID-19 diagnosis compared to pregnant women without COVID- 19 diagnosis during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. | 874 | 243771 | 146 (16.7%) | 17,215 (7.1%) |

| Increased spontaneous preterm births during the second wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in India - Mahajan et al [10] | Covid hospital Mumbai, India. April 4, 2020 and July4, 2021. | Hospital-based, retrospective cohort study | To compare spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) and iatrogenic preterm birth (IPTB) rates during both waves of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)pandemic | 1136 | 3463 | 128 (11,3%)) | 259 (13.8%) |

| Maternal SARS-COV-2 infection and prematurity:the Southern Michigan COVID-19 collaborative - Bahado-Singh et al [11] | Michigan, USA, from March 2020 till October1st, 2020. | Multicentre case-control study | Determinate the impact of COVID-19 disease on PTB overall, as well as related subcategories such as early prematurity, spontaneous, medically indicated PTB, and preterm labor. | 369 | 1090 | 58 (15,72%) | 96 (8.81%) |

| Perinatal complications in Individuals in California With or Without SARS-CoV-2 Infection During Pregnancy - Ferrara et al [12] | Northern California, March 1, 2020, and March 16, 2021. | Cohort study | Examinate the risk for perinatal complications in pregnant individuals withSARS-CoV-2 infection. | 1332 | 42554 | 143 (10.74%) | 3438 (8.08%) |

| Timing and severity of COVID-19 during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth in the International Registry of CoronavirusExposure in Pregnancy - Smith et al [13] | USA. June 2020-July 2021 | International internet-based retrospective cohort study | Estimate the risk of PTB (overall, spontaneous, and indicated) after COVID-19 during pregnancy, while considering different levels of disease severity and timing. | 1192 | 4692 | 152 (12,75%) | 414 (8.82%) |

| Preterm birth is not associated withasymptomatic/mild SARS-CoV-2 infection per se: Pre-pregnancy state is what matters – Cosma et al [17] | Italy. 20 September 2020 and 9 January 2021. | Case-control study | To determine the real impact of asymptomatic/mild SARS-CoV-2 infection onPTB not due to maternal respiratory failure. | 53 | 176 | 21 (39,62%) | 81 (46,02%) |

| The Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Premature Birth—Our Experience as COVID Center - Bobei et al [18] | Romania. from March 2020 to June 2021 | Prospective observational study in a COVID-only hospital | Determination of the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on PTB pregnancies | 238 | 33 (14.28%) | 8.2% | |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and preterm birth in Massachusetts from March 2020 through March 2021 - Darling et al [20] | Massachusetts , from 1 March 2020 to31 March 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | Examinate the association between SARS-CoV- 2 infection and spontaneous and provider-initiated PTB, and how timing of infection, andrace/ethnicity as a marker of structural inequality, may modify this association | 2195 | 66076 | 254 (11.57%) | 4655 (7.04%) |

| Adverse Birth Outcomes Among Pregnant Women With and Without COVID-19: A Comparative Study From Bangladesh - Masud et al [21] | Bangladesh, from March to August 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Compare birth outcomes related to COVID-19 between Bangladeshi pregnant women with and without COVID-19 | 70 | 140 | 37 (52,9%) | 42 (30.0%) |

| Association between SARS-CoV-2 infections during pregnancyand preterm live birth – Mohanty et al [22] | USA. August 2020–October 2021 | Prospective cohort study. | Examinate associations between mild or asymptomatic prenatal SARS-CoV-2 infection and preterm live birth | 185 | 769 | 26 (14%) | 97 (13%) |

| Maternal outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 severity among pregnant women Vouga et al [24] | COVI-Preg internationalregistry. March 24 and July 26, 2020. | Retrospective comparative Monocentric | Insight into the maternal outcomes and risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity in pregnant women | 926 | 107 | 110 (11,88%) | 8% |

| Preterm birth among women with and without severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection - Blitz et al [25] | New York City and Long Island. March 2020 and June 2021 | Retrospective cohort study | To establish potential risks determined by a COVID-19-positive pregnancy towards the mother and the newborn. | 1261 | 30289 | 138 (10,98%) | 2140 (6,78%) |

| Preterm birth and severe maternal morbidityassociated with SARS-CoV-2 infection duringthe Omicron wave - Gulersen M et al [26] | Nwe Tork. December 1, 2021 and February 7, 2022. | Retrospective cohort study | Evaluate the risk of PTB and severe maternal morbidity (SMM) in pregnant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the most recent wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. | 631 | 4107 | 68 (10,8%) | 329 (8,0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).