5.1. Compare Performance with Other Models

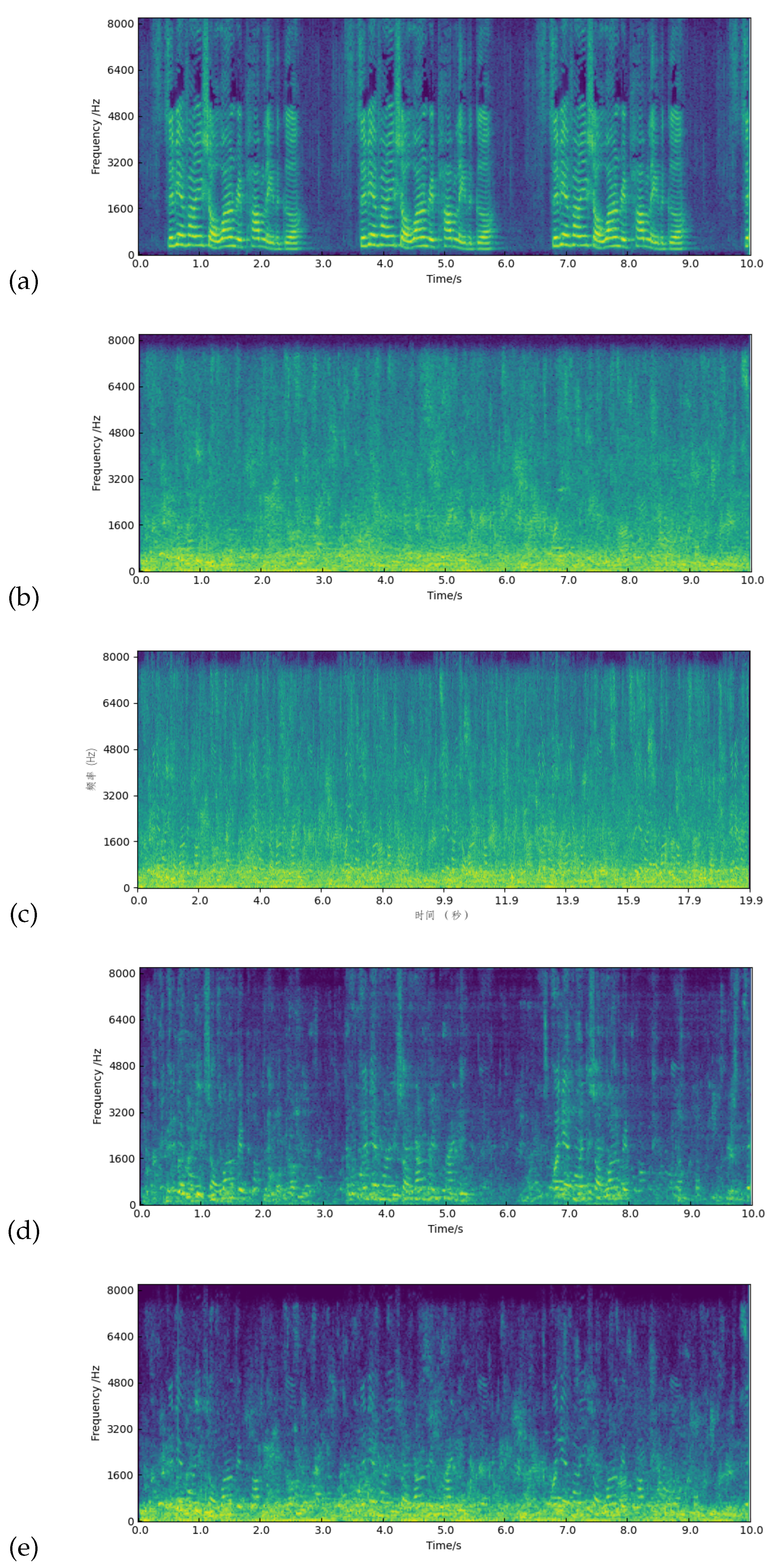

In this study, as shown in

Table 4, we evaluated the GRU-2L-128 model on the DNS test set for speech enhancement. This model significantly outperforms the original noisy audio recordings in terms of PESQ and STOI metrics, with improvements from 1.710 to 2.175 for PESQ and from 0.713 to 0.768 for STOI. Compared to state-of-the-art models like DCCRN and DCUNET, GRU-2L-128 shows remarkable performance, especially in low SNR conditions where it outperforms DCCRN by improving from 1.544 to 1.729 in PESQ and exhibits a slight advantage over DCUNET with an improvement to 1.729 in PESQ. Despite a small gap with DCUNET in high SNR conditions, GRU-2L-128 maintains competitive performance. Against models with similar structures, such as Nsnet2, GRU-2L-128 achieves slightly better results in low SNR scenarios with less computational cost and parameters, improving PESQ from 1.702 to 1.729. Compared to GRU-2L-256, GRU-2L-128 shows a slight decrease in PESQ but maintains similar performance in high SNR ranges. Overall, GRU-2L-128 significantly surpasses the RNN-Noise model in all metrics, especially in low SNR conditions where PESQ improved from 1.439 to 1.729 and STOI from 0.579 to 0.668. In high SNR scenarios, PESQ and STOI also saw substantial increases. These results demonstrate GRU-2L-128’s superior speech enhancement performance in various noise environments and low SNR conditions.

In the performance comparison on the Speech Babble test set, as shown in

Table 5, models like DPTNET, DPRNN, DCUNET, and DCCRN saw significant performance declines and are not compared here. The GRU-2L-128-learn model improved in high SNR scenarios, with PESQ increasing from 2.106 to 2.356 and STOI from 0.883 to 0.889, indicating optimized speech quality. However, performance slightly decreased in low SNR ranges, with a drop in PESQ from 1.486 to 1.429 and a minor decrease in STOI. Compared to the Rnn Noise model, GRU-2L-128-learn had a slightly higher STOI in low SNR scenarios (0.515 vs. 0.504), suggesting about a 1% improvement in intelligibility. Against Nsnet2, GRU-2L-128-learn was slightly lower in both STOI (0.675 vs. 0.684) and PESQ (1.826 vs. 1.898), showing comparable clarity but about 1% lower intelligibility.The GRU-2L-128 model showed some disadvantages compared to Rnn-Noise in high SNR conditions on the Speech Babble set. This could be due to training data differences, where Rnn-Noise’s inclusion of crowd noise may have enhanced its performance, and the loss of frequency band information, as noise reduction in Speech Babble requires reliance on non-primary energy regions. The GRU-2L-128’s compression of audio bands to 64 might lead to information loss in these areas. The performance comparison on the VCTK test set demonstrates the effectiveness of the GRU-2L-128 model as shown in

Table 6. When compared to the noisy audio baseline, the model enhances the overall PESQ from 1.774 to 2.189 and improves the overall STOI from 0.683 to 0.709. In low SNR conditions, the GRU-2L-128 notably outperforms the current DCCRN, raising the PESQ from 1.692 to 1.770 and the STOI from 0.567 to 0.610. Despite its similar structure to Nsnet2, GRU-2L-128 shows slightly lower metrics, with a total PESQ of 2.189 compared to Nsnet2’s 2.321, and a STOI of 0.709 versus Nsnet2’s 0.726. However, against Rnn-Noise, it exhibits significant improvements in low SNR areas, increasing the PESQ from 1.547 to 1.770 and the STOI from 0.575 to 0.610. Versus the GRU-2L-256 model, GRU-2L-128 not only benefits from reduced computational demands but also demonstrates superior performance, with both overall PESQ and STOI metrics surpassing those of GRU-2L-256.

The experimental results in this subsection demonstrate the powerful performance of the GRU-2L-128 model proposed in this chapter in handling diverse noise environments and steady noise conditions. The model not only shows superior performance compared to other open-source models with similar computational power and architecture but also exhibits competitive strength against advanced models with computational costs up to 300 times higher, such as DCCRN and DCUNET. In crowd noise-dominated Speech Babble scenarios, the GRU-2L-128 model demonstrates good enhancement performance in low SNR ranges. These outcomes highlight the potential and practicality of the self-referencing signal scheme in ultra-lightweight speech enhancement, offering a viable solution for deploying high-performance speech enhancement models at the edge.

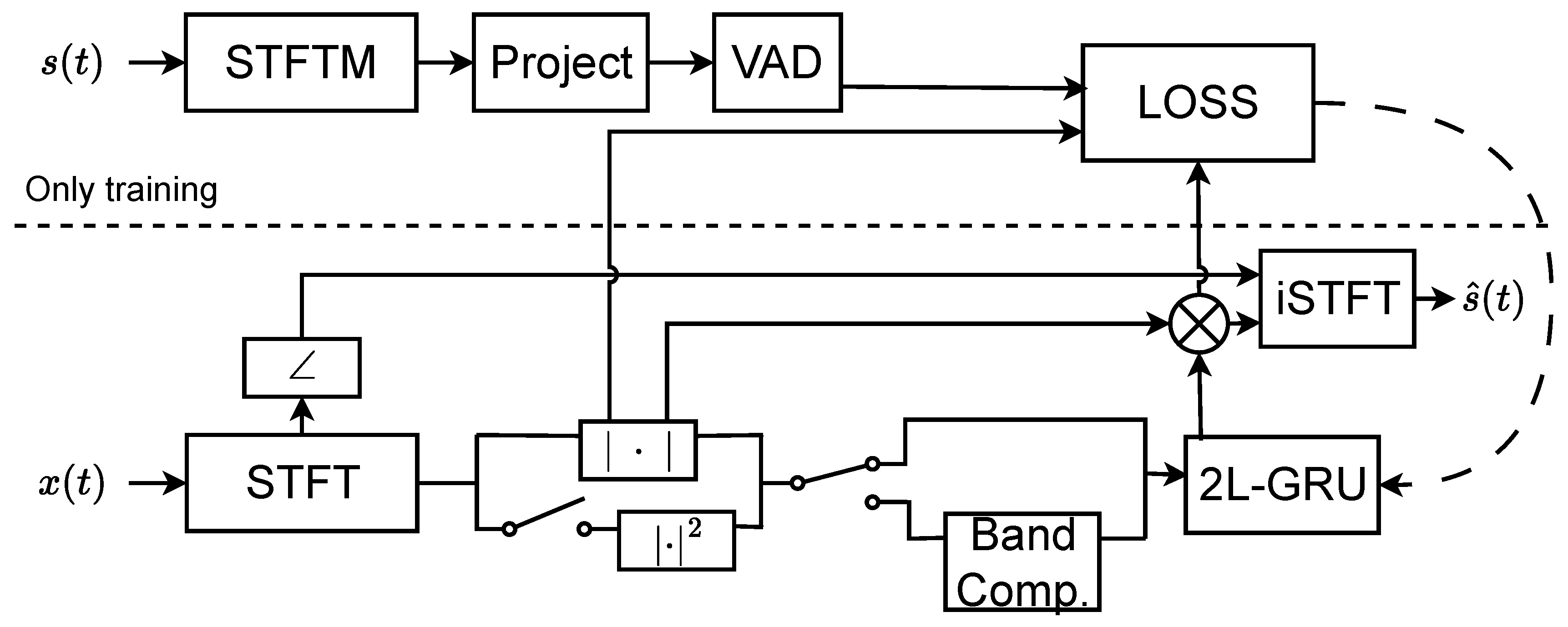

5.2. Effect of Reference Signal

This subsection’s experiment aims to explore the impact of different model input features on model performance. In the practice of audio signal processing, taking the logarithm of the square of the input amplitude spectrum is a common processing method. This method can, to some extent, simulate the human ear’s perception of sound intensity and help improve the model’s ability to process speech signals. To thoroughly ablate the impact of input features on model performance, this subsection starts with the logarithmic power spectrum as the benchmark for input features and conducts a series of extended ablation experiments to discuss the specific impact of different types of input features on model performance. For the ablation experiments, the following notations were designed:

1. Nolog: indicates not taking the Log of the input signal.

2. Log: indicates taking the Log of the input signal.

3. Noisy: indicates the amplitude spectrum of noisy audio.

4. Noisy2: represents the square of the amplitude spectrum of noisy audio; this signal is input into the model together with Noisy as a reference signal.

5. Noise: represents the complement of the power spectrum on the original amplitude spectrum; this signal is input into the model together with Noisy as a reference signal.

In this experiment, all frequency band compression methods used a learnable matrix initialized with Mel filter bank parameters. For single-input signals, the signal is compressed to 128 dimensions; for dual-input signals, the two signals are separately compressed to 64 dimensions each and then concatenated before being input into the model. This design aims to explore the comprehensive impact of different input feature combinations on model performance and how optimizing input features can further enhance the model’s performance on speech enhancement tasks.

Experiments on the DNS test set, as shown in

Table 7, led to important observations about the impact of input feature types on model performance. The approach without logarithmic transformation, No Log-Noisy2, did not improve over the noisy audio baseline, underscoring the importance of logarithmic transformation for effective training. Applying logarithmic transformation (Log-Noisy2) significantly enhanced model performance, with PESQ and STOI scores increasing to 2.092 and 0.765, respectively, proving its effectiveness. Using original input features (Log-Noisy) slightly decreased performance, indicating reduced noise discrimination capabilities with the original magnitude spectrum. The Log-Noisy2_Noisy method, using Noisy2 as a reference signal, achieved better results, particularly in PESQ and STOI scores, which rose to 2.175 and 0.768, respectively. This shows improved clarity and intelligibility. The Log-Noise_Noisy strategy, which uses Noise as a reference, showed lower performance in terms of clarity and intelligibility compared to the Log-Noisy2_Noisy approach. This indicates that Noise as a reference signal is less effective in varied noise situations.

In the Speech Babble test set experiments evaluating input feature types’ impact on model performance as shown in

Table 8, several insights were gathered. The Nolog-Noisy2 approach without logarithmic transformation showed poor performance, with a decrease in PESQ to 1.608 and a significant drop in STOI to 0.490, emphasizing the necessity of logarithmic transformation. Using Log-Noisy2 as input, the model showed balanced improvements, with PESQ increasing to 1.832 and a slight STOI enhancement to 0.688, demonstrating the effectiveness of logarithmic power spectrum features. With Log-Noisy inputs, the model saw a minor PESQ improvement to 1.793 but a STOI decrease to 0.649, indicating a performance decline compared to Log-Noisy2. Utilizing Noise as a reference, the Log-Noise_Noisy model achieved the highest PESQ of 1.860 and an STOI of 0.680, showcasing the advantage of reference signal approaches in noisy voice scenarios. The Log-Noisy2_Noisy model slightly underperformed compared to Log-Noise_Noisy but surpassed both Log-Noisy2 and Log-Noisy approaches, highlighting the benefits of integrating uniform noise features for improved model performance in noise-dominated settings.

The experiments on the VCTK test set, as shown in

Table 9, reveal several key findings. Firstly, the Nolog-Noisy2 method, which avoids logarithmic transformation of inputs, underperforms significantly and is excluded from further discussion. The Log-Noisy2 input, conversely, demonstrates strong performance in terms of clarity and speech intelligibility, achieving PESQ and STOI scores of 2.170 and 0.712, respectively. This improvement suggests that emphasizing the temporal energy sparsity of input features is beneficial in steady noise conditions.

Moreover, employing noise as a reference signal does not substantially improve the model’s performance, with negligible differences in PESQ and STOI scores compared to using only noisy inputs. This outcome indicates that, in steady noise environments, the noise reference signal has limited utility in enhancing model efficacy.

Additionally, the Log-Noisy2_Noisy approach, which incorporates both Noisy and Noisy2 inputs, performs comparably to methods using only Noisy2 as a reference, without noticeable benefits. This implies that the inclusion of additional reference signals does not necessarily translate to improved model performance in this context, with Noisy2 input alone sufficing for satisfactory results.

In summary, the experiments underscore the importance of focusing on signal temporal energy sparsity in steady noise situations to achieve relatively good outcomes. However, attempts to promote uniformity may detract from model performance. The Log-Noisy2_Noisy feature, leveraging Noisy2 as a reference signal, consistently exhibits stable performance under these conditions. It significantly outperforms other input configurations in diverse noise environments, though it does not demonstrate a marked advantage in specific scenarios like the Speech Babble and VCTK tests. In contrast, the Log-Noise_Noisy scheme, utilizing noise as a reference, shows notable improvement in the Speech Babble test set, likely due to the noise signal’s representation of audio aspects weakened by squaring functions, effectively aiding the model in distinguishing between speech signals and noise.

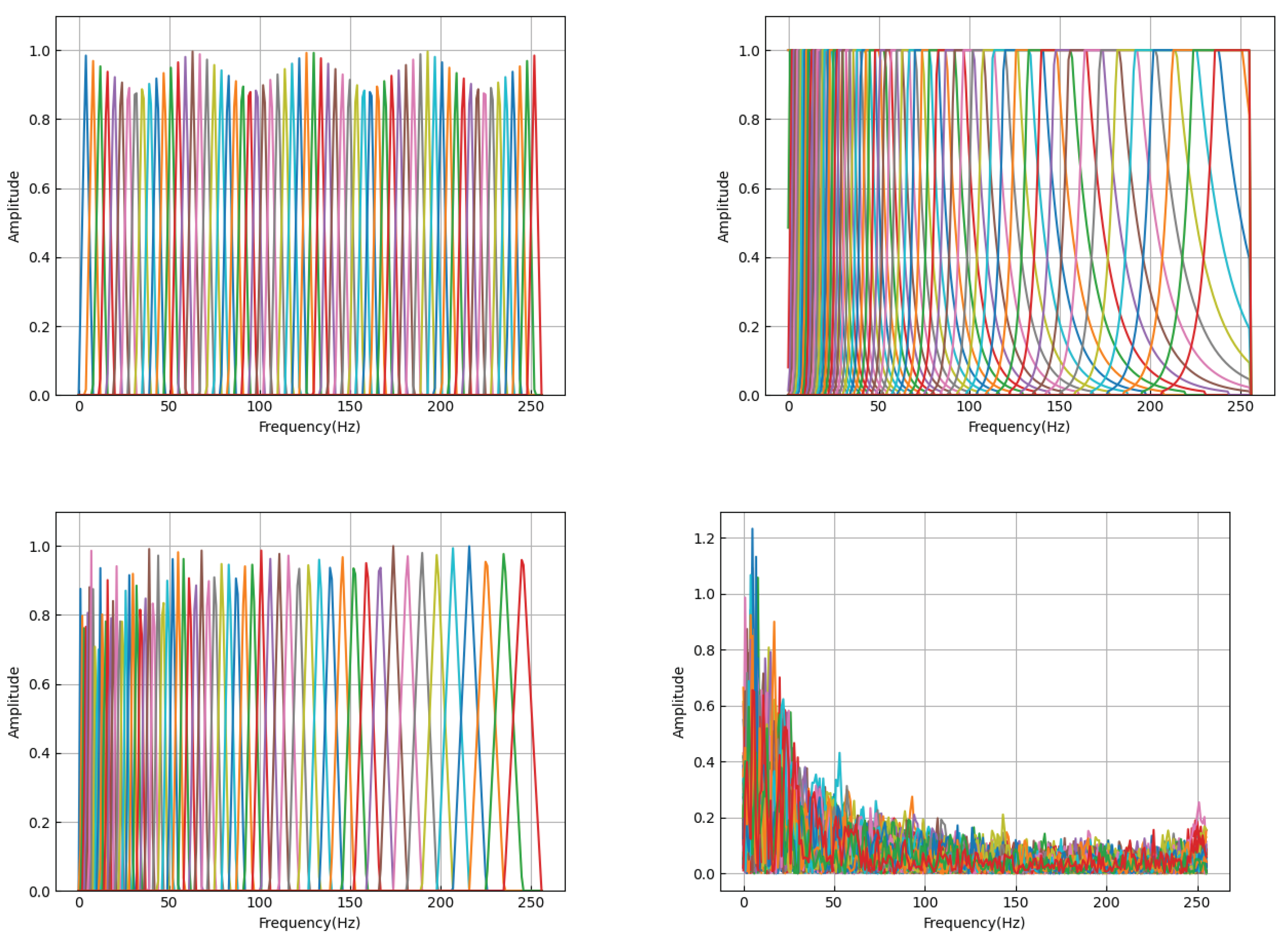

5.3. Effect of Band Compression

In this subsection, the aim is to investigate the impact of different model frequency band compression methods on model performance within a self-referenced signal framework. All selected model configurations accept two input signals, both of which are compressed to 64 dimensions by different compression methods before being input into the model. Based on the best overall performance demonstrated in previous experiments, Noisy2 and Noisy were chosen as the reference signal schemes.

To delve into the impact of different frequency band compression methods on model performance, this subsection ablates the following four compression schemes,which their filter bank as shown in

Figure 3:

1. Linear (Linear Filter): This method divides and compresses the frequency band at equal intervals in a linear manner, being the most straightforward and intuitive frequency band compression method.

2. Bark (Bark Filter): The Bark filter is designed based on the auditory characteristics of the human ear, attempting to simulate the ear’s sensitivity to different frequencies for a more natural perception of sound.

3. Mel (Mel Filter): The Mel filter is based on the Mel scale, which reflects the non-linear perception of frequency by the human ear, making the compressed spectrum more consistent with human auditory characteristics.

4. Learn (Learnable Parameters Initialized with the Mel Matrix): This scheme starts with Mel filter parameters as initial values, but allows these parameters to be adjusted and learned during the training process to find a frequency band compression method more suitable for specific tasks.

The ablation experiments on compression methods conducted on the DNS test set, as shown in

Table 10, reveal significant impacts of different compression methods on model performance in diverse speech and noise scenarios. Although the performance of the linear compression method is lower than other methods, it still achieved a noticeable improvement over the noisy audio baseline. The PESQ increased from 1.710 to 2.094, and STOI from 0.713 to 0.746. This indicates that even the simplest form of linear compression can lead to convergence and improvement in performance through training. Compared to linear compression, the Bark filter showed a slight improvement in clarity (PESQ) to 2.109 but a slight decrease in intelligibility (STOI) to 0.741. This could be because the Bark filter is closer to human auditory characteristics but may lose some noise discrimination capability in certain conditions. The Mel filter excelled in all test metrics, with PESQ reaching 2.171 and STOI 0.769, outperforming both Bark and linear filters. This suggests that the Mel filter can better preserve the main features of speech signals while effectively compressing noise, making it one of the most effective compression methods under diverse speech and noise conditions.The Learn scheme, with performance close to Mel initialization, achieved a PESQ of 2.175 and STOI of 0.768. In low SNR scenarios, it maintains intelligibility while slightly improving clarity (PESQ) over the Mel filter. This implies that further fine-tuning of model performance, especially in terms of clarity, is possible on the basis of the Mel filter by allowing for parameter learning and adjustments.

The experimental results indicate that under diverse speech and noise conditions, Mel filters or Mel-based learnable schemes can maximally preserve key features of speech signals, thereby enhancing the overall performance of the model.

The ablation experiments on compression methods conducted on the Speech Babble test set, as shown in

Table 11, demonstrate how different compression methods affect model performance, especially in low SNR scenarios. The Linear and Bark filters showed higher PESQ scores of 1.613 and 1.639, respectively, but their intelligibility scores were relatively lower, at 0.437 and 0.447. This may indicate that these compression methods enhance audio clarity at the expense of some intelligibility. In high SNR scenarios, the performance of Linear and Bark in terms of both clarity and intelligibility was lower than that of Mel and Learn, suggesting that the Mel and Learn schemes are more effective in balancing clarity and intelligibility under these conditions. The Mel filter and Learn scheme showed similar performance, with PESQ scores of 1.846 and 1.826, and STOI scores of 0.677 and 0.675, respectively. This indicates that Mel-based compression methods can better preserve speech information in situations where the noise distribution closely matches the speech energy distribution, avoiding the elimination of important speech components as noise. The results highlight the importance of choosing the appropriate frequency band compression method on test sets like Speech Babble, where the noise and speech spectral characteristics are closely matched. Mel filters and Mel-based learnable schemes effectively compress noise while preserving speech information, particularly showing superior performance in high SNR scenarios. Conversely, although Linear and Bark schemes can enhance audio clarity in certain conditions, they may fall short in maintaining speech intelligibility.

The ablation experiments on compression methods conducted on the VCTK test set, as shown in

Table 12, demonstrate the impact of different compression methods on model performance, especially in low SNR scenarios. Both Linear and Bark schemes showed similar performance in low SNR conditions, with PESQ scores of 2.130 and 2.144, and STOI scores of 0.686 and 0.683, respectively. This indicates that on the VCTK test set, Linear and Bark filters have converging effects in processing low SNR speech data, with relatively lower performance. The Mel filter showed an improvement in intelligibility compared to the previous two, increasing from approximately 0.68 to 0.708, with a slight increase in PESQ to 2.158. This suggests that the Mel filter can effectively compress noise while preserving speech information, particularly excelling in enhancing speech intelligibility. The Learn scheme, while maintaining similar intelligibility to the Mel filter , significantly improved in clarity , reaching 2.189. This indicates that by using Mel filter parameters as initialization and adjusting them during training, the learnable scheme can further optimize model performance, especially in enhancing speech clarity. The results show that in the VCTK test set, Mel filters and Mel-based learnable schemes are more effective in processing speech data under low SNR conditions compared to Linear and Bark filters, especially in improving speech intelligibility. Moreover, the learnable parameter scheme (Learn) significantly enhances speech clarity while maintaining intelligibility, proving to be an effective frequency band compression strategy in steady noise scenarios.

Overall, the Mel-based learnable scheme exhibits good balanced performance in diverse noise and Speech Babble scenarios, comparable to directly using Mel filters, and is more effective than Mel in enhancing speech signal clarity in steady noise environments. This outcome suggests that using Mel filter parameters as initial values and adjusting these parameters during model training can provide additional clarity gains for speech signals without sacrificing intelligibility.