Submitted:

15 March 2024

Posted:

15 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Infrarred

3.2. Mass Spectrometry

3.3. 1H NMR Liquid State

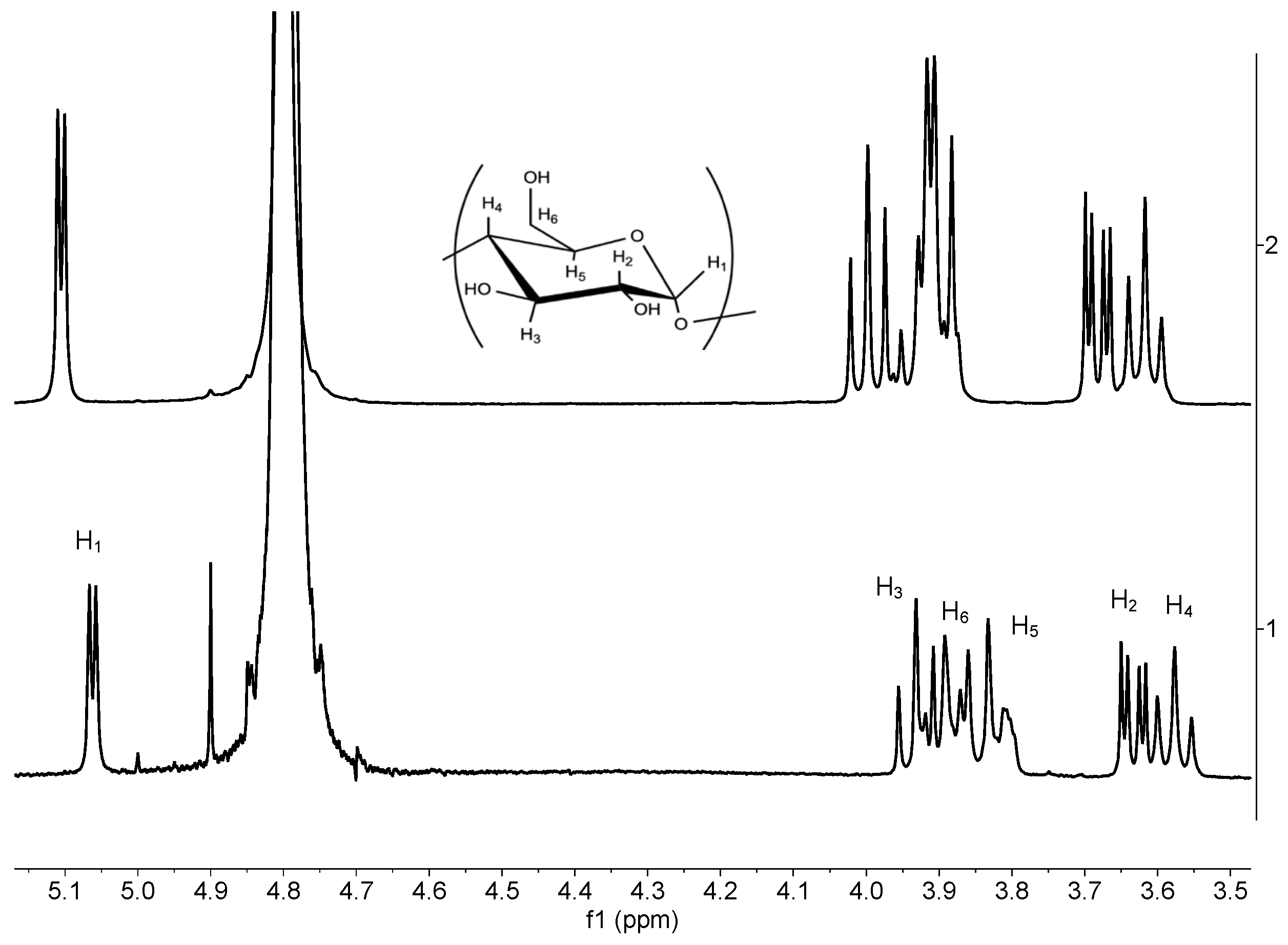

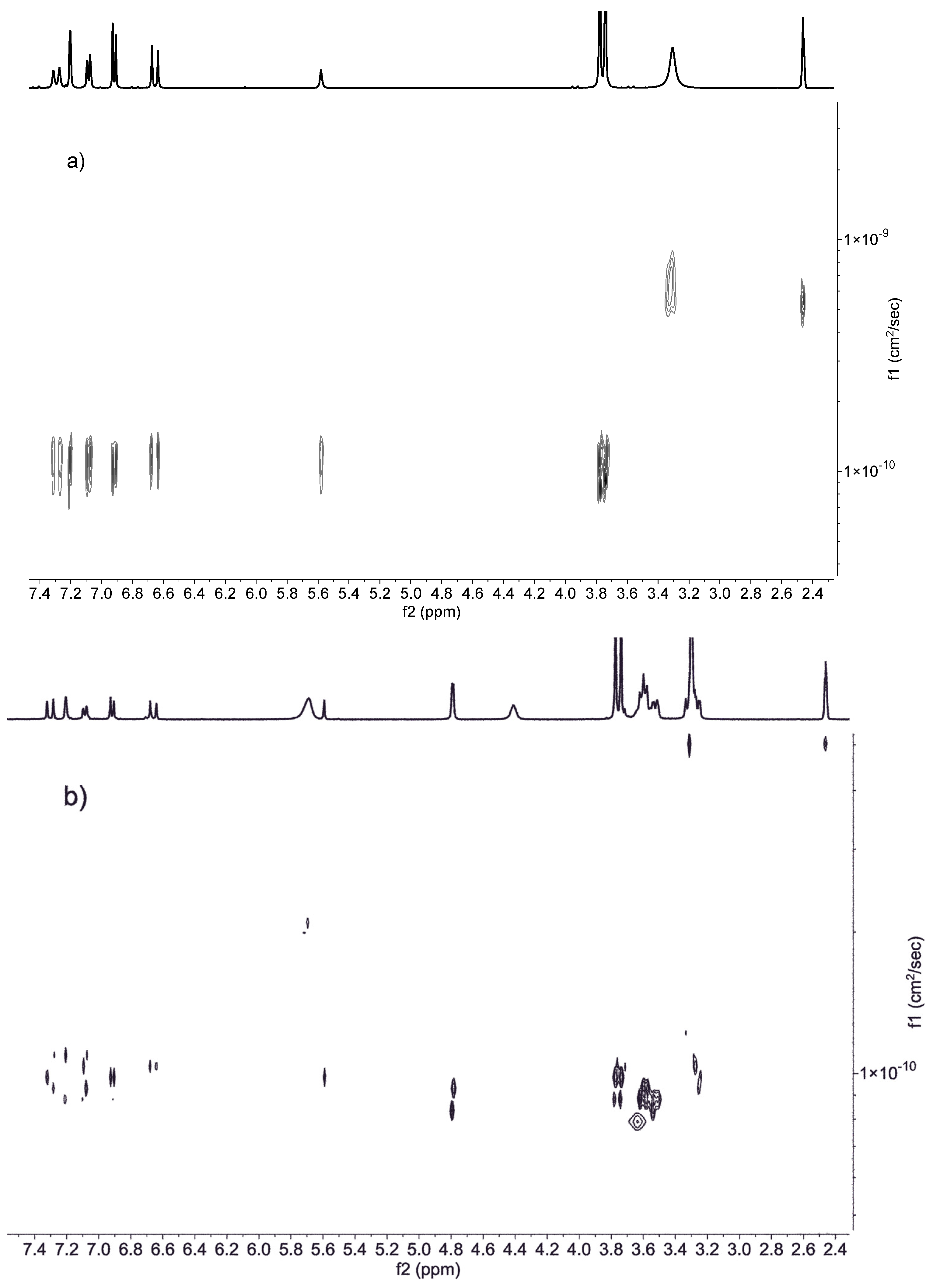

3.4. DOSY Spectra

3.5. Solubility, Ratio of Guest-Host and HPLC

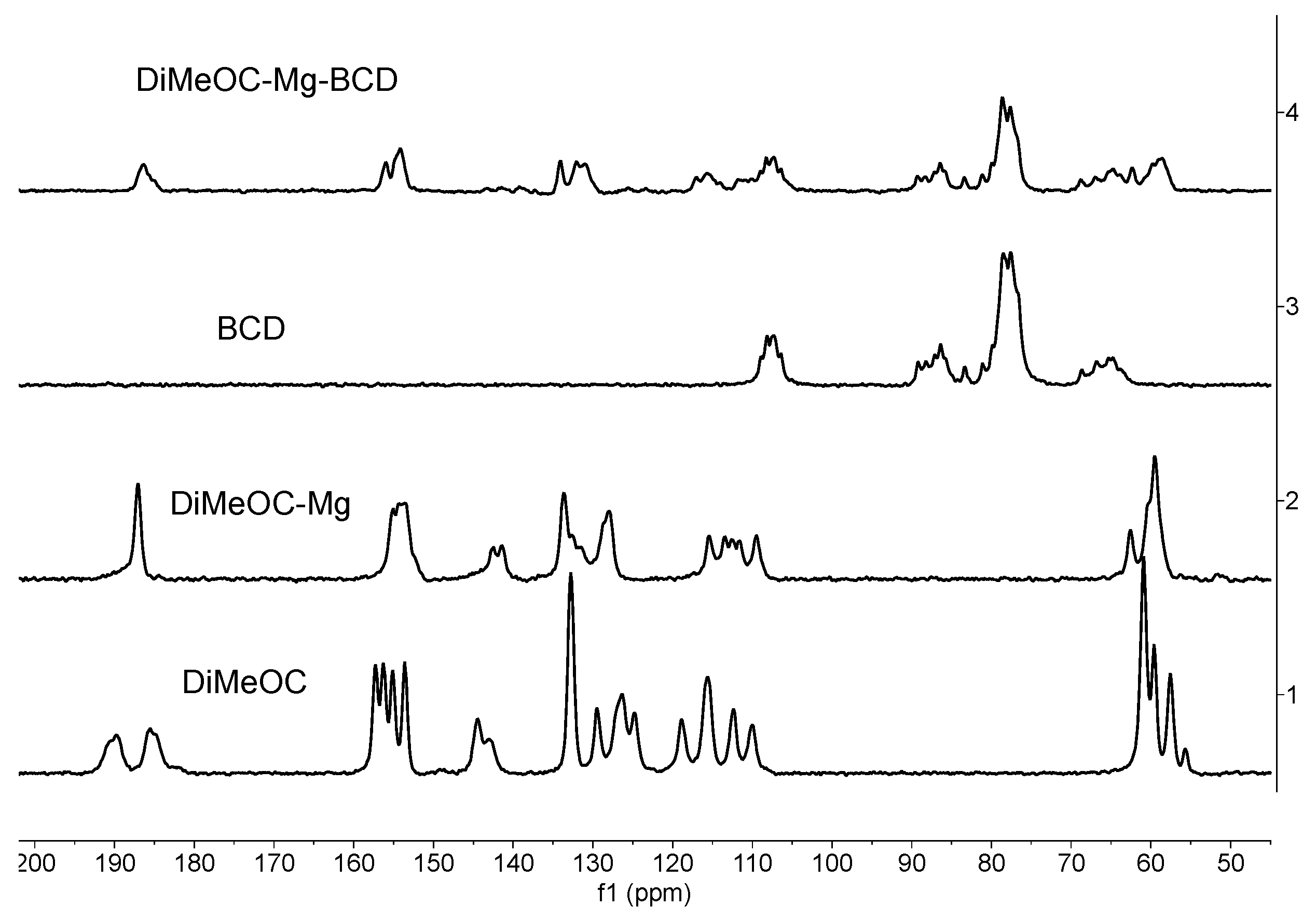

3.6. 13C CPMAS Solid State NMR

- The guest (DiMeOC-Mg) was adequately complexed with BCD using the selected coprecipitation method.

- The relaxation phenomena for the guest molecule becomes very fast (low intensity of signals) when located at the cavity of BCD.

- The inclusion complex reveals an amorphization (broadening of signals) in agreement with the data obtained by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

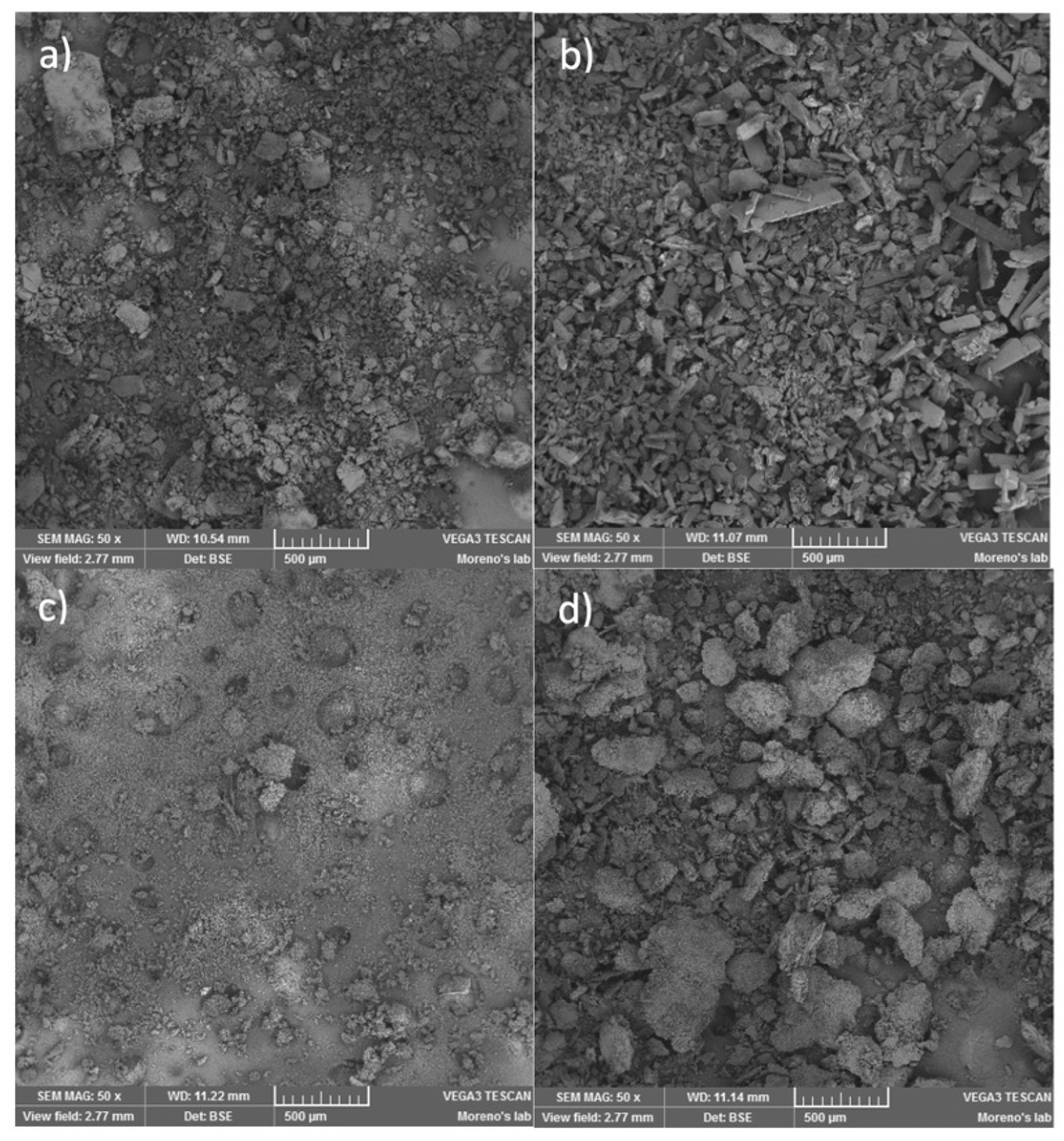

3.7. SEM Analysis

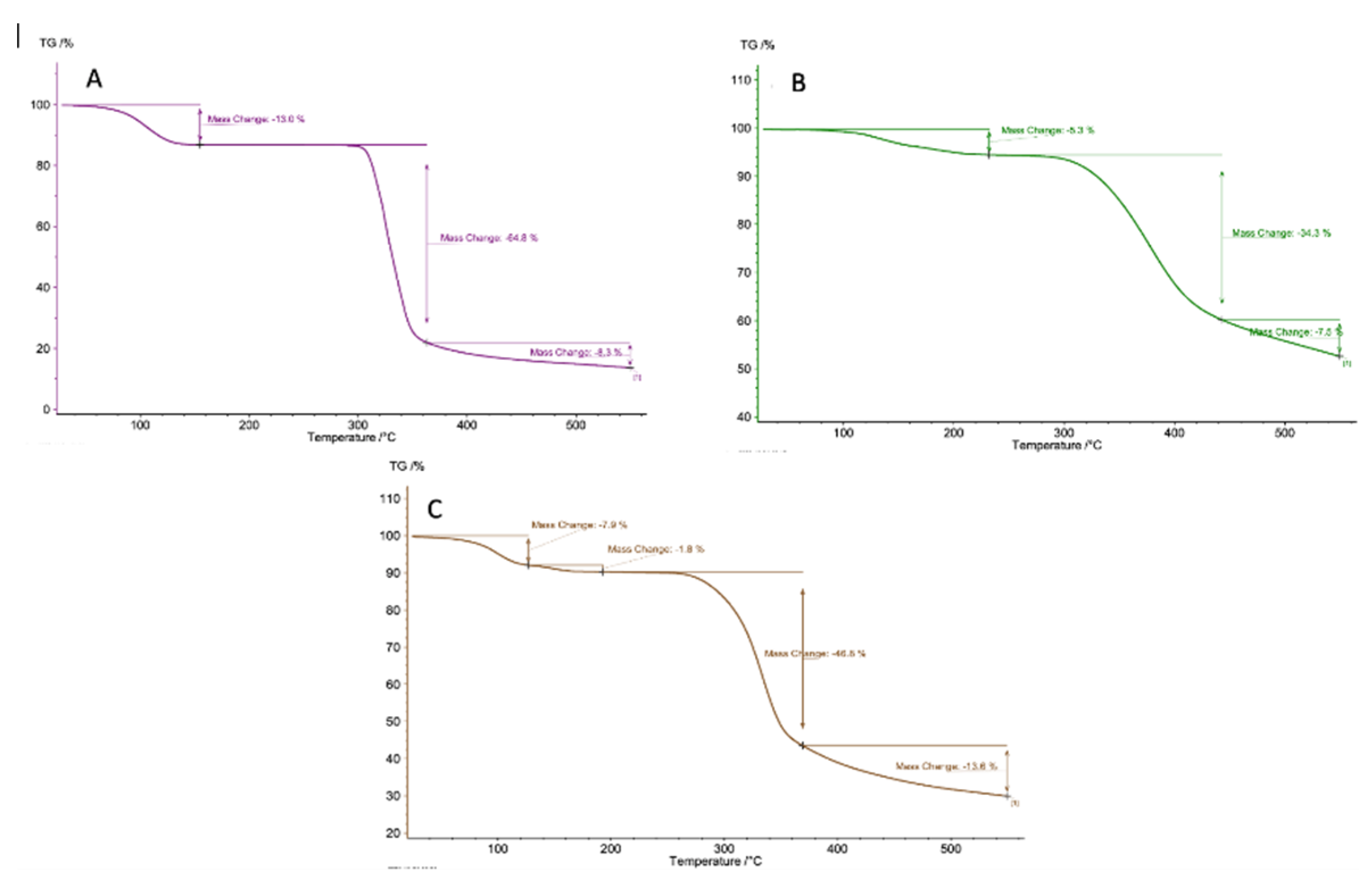

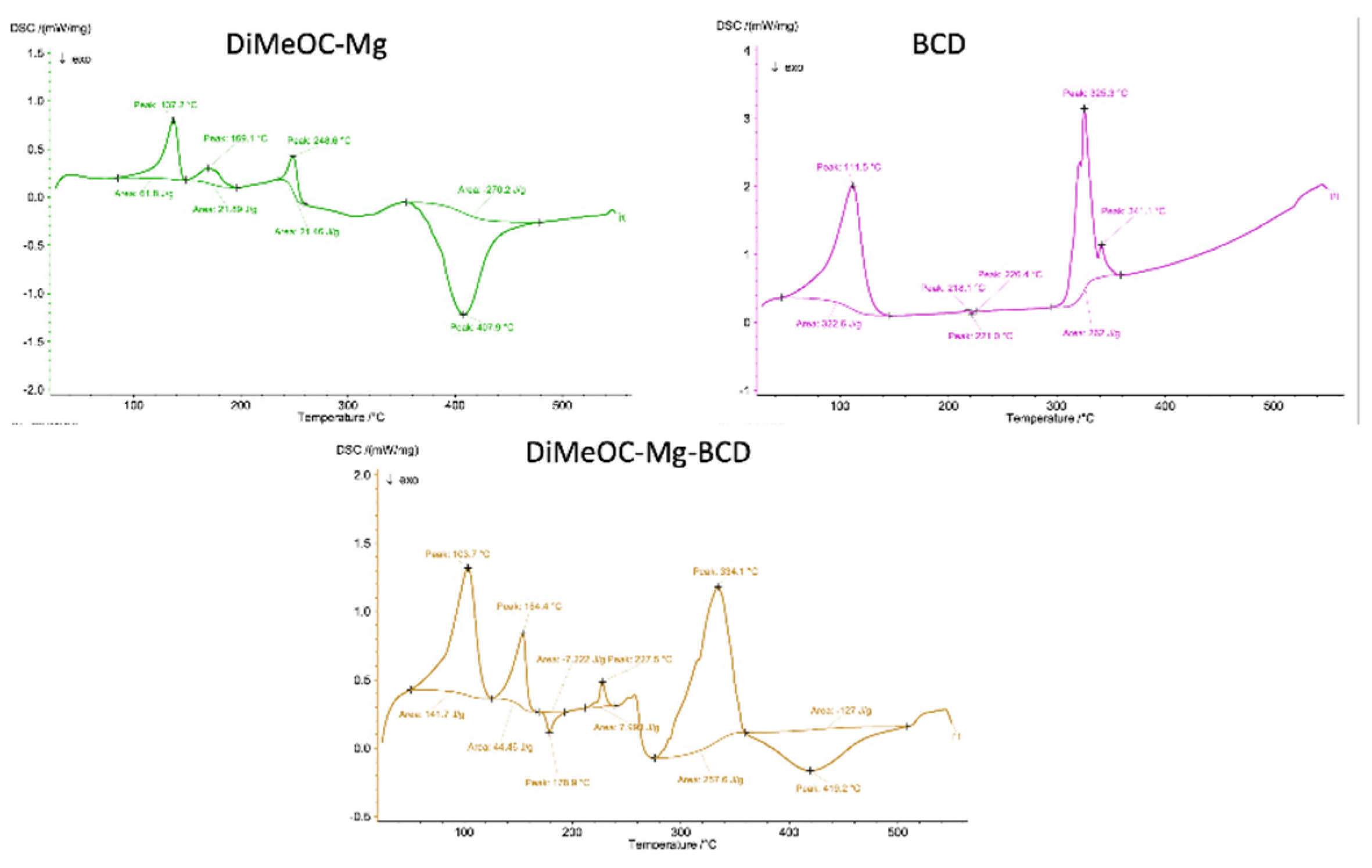

3.8. TGA and DSC Analysis

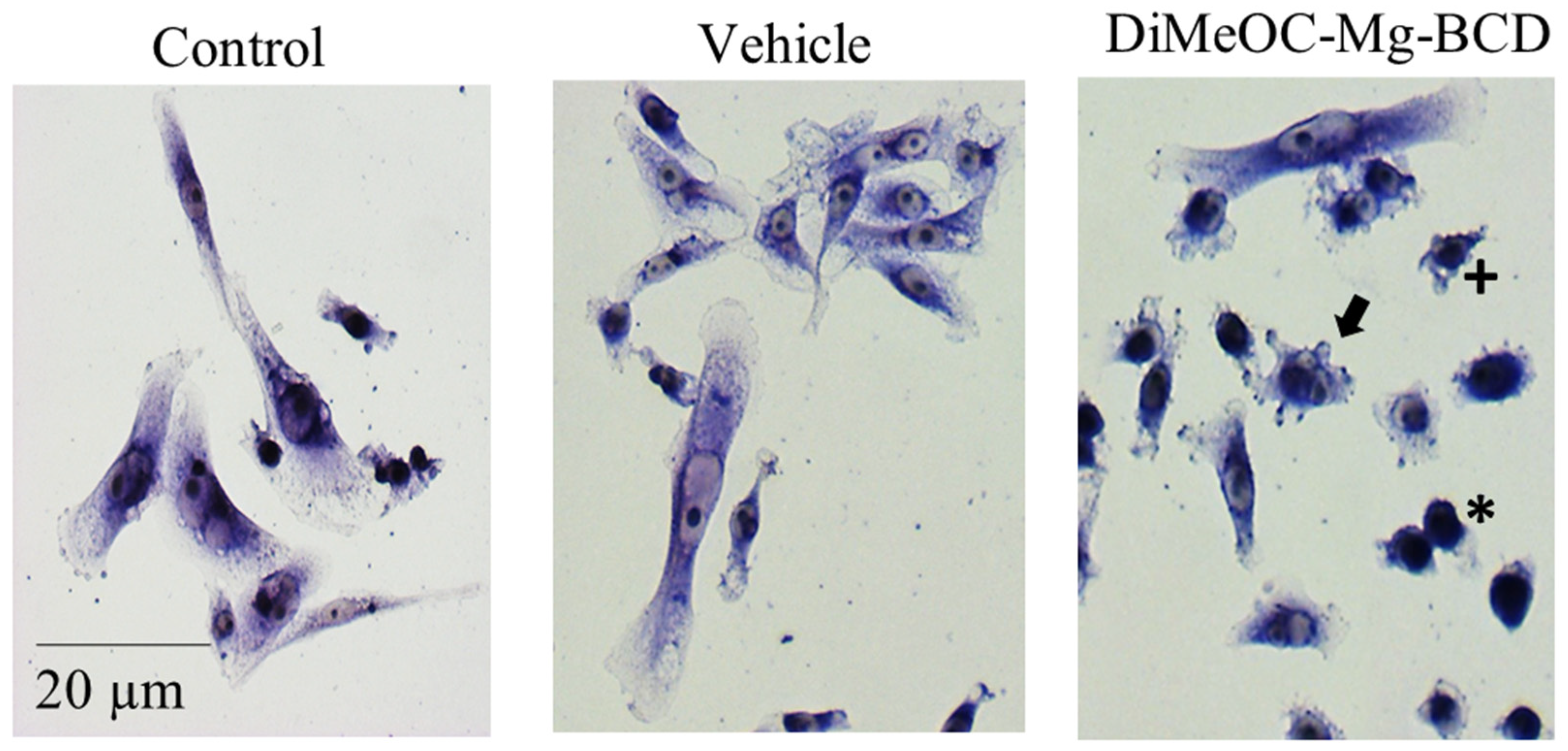

3.9. Cytotoxic Activity in Human Tumour Cells and Evaluation of Morphological Changes

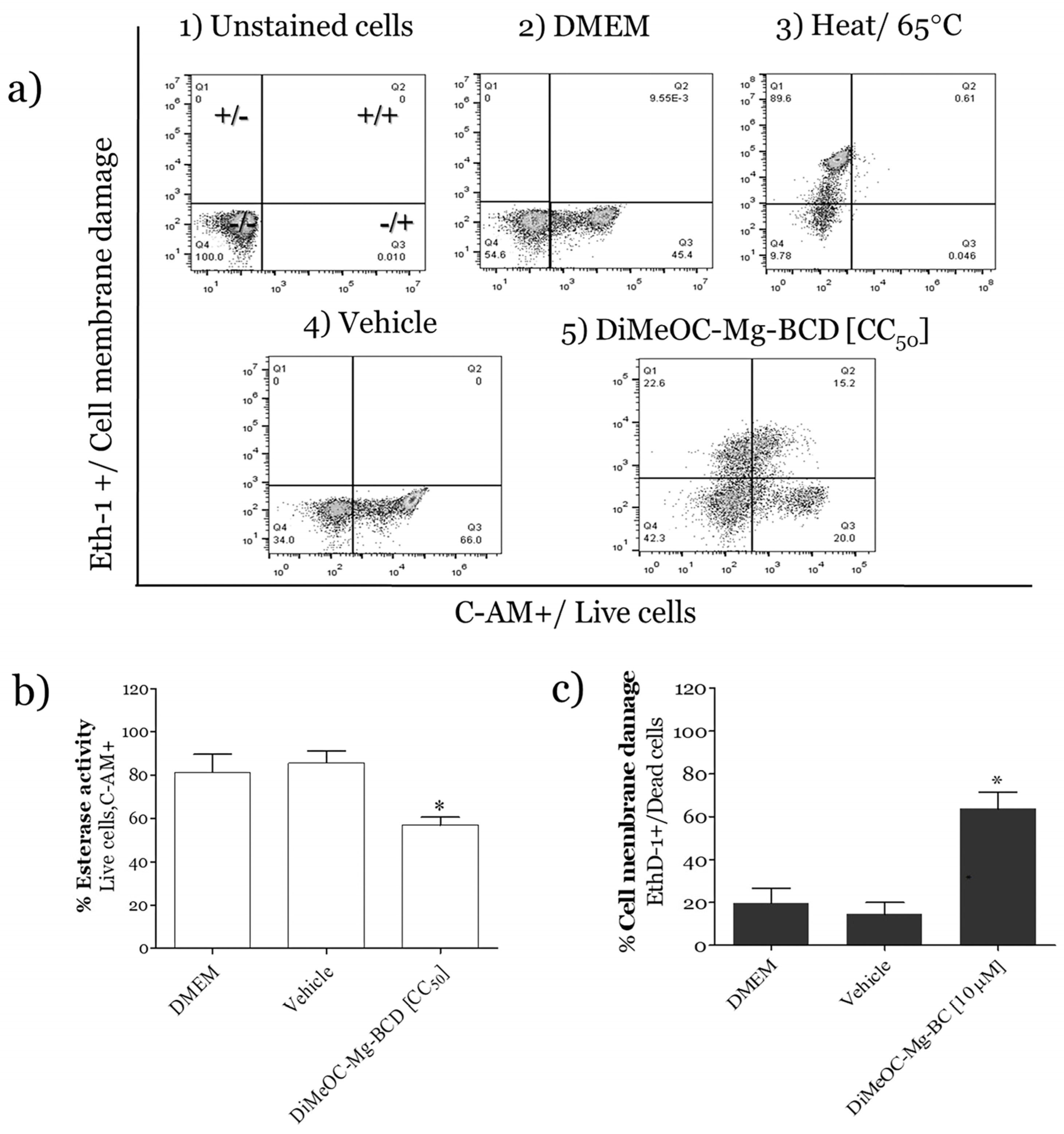

3.10. Esterase Activity and Membrane Damage Induced by DiMeOC-Mg-BCD on MDA-MB-231

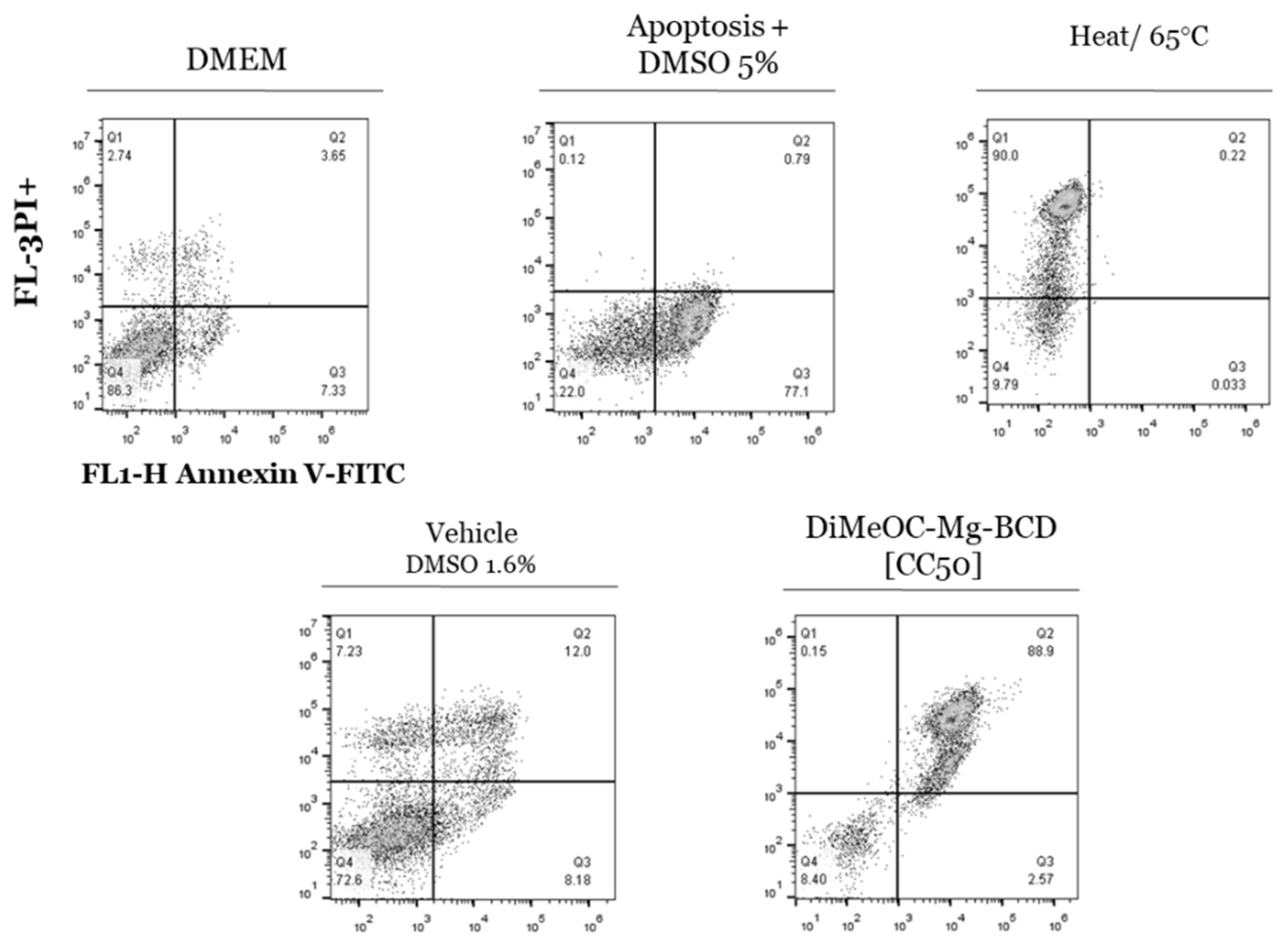

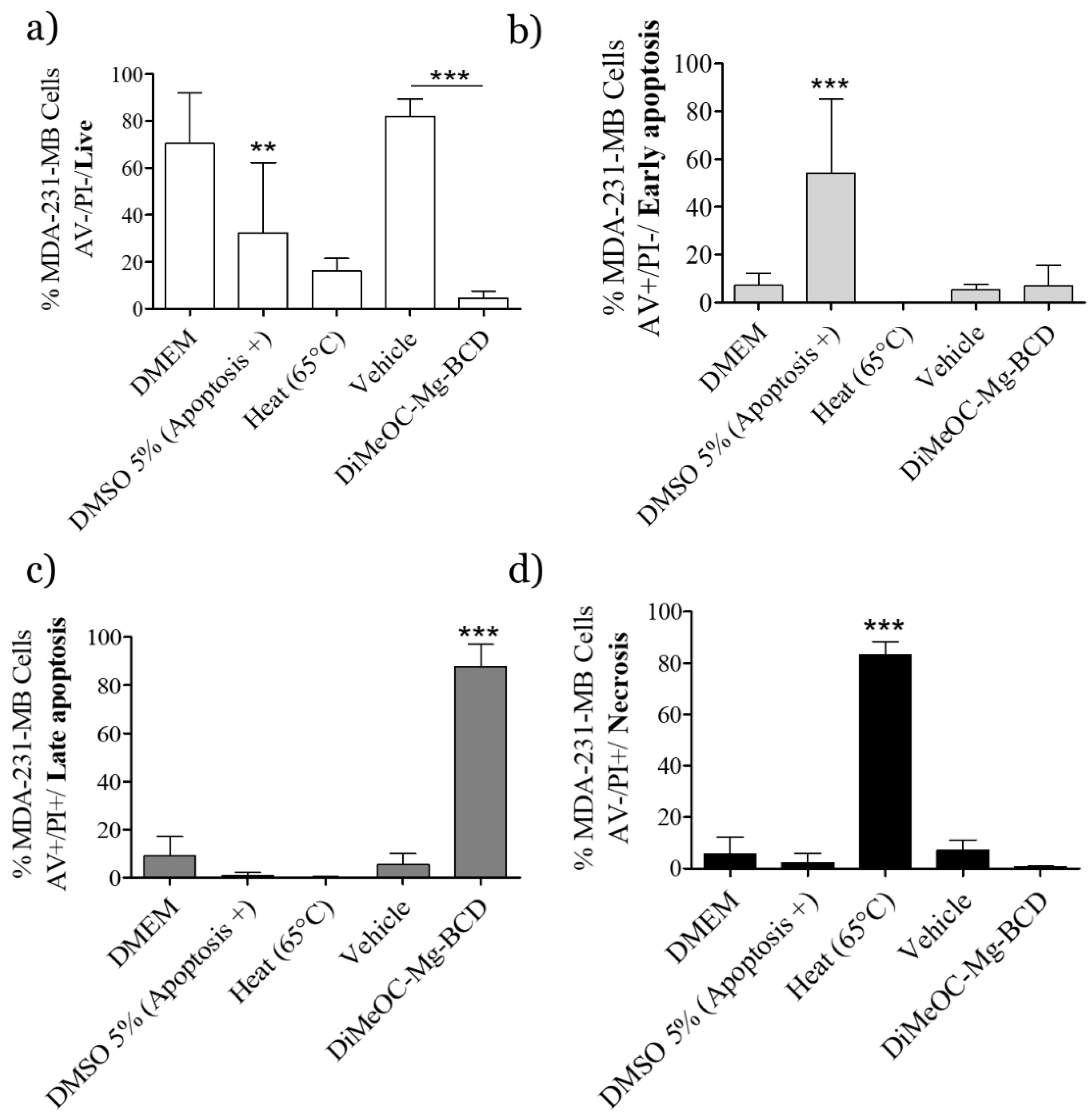

3.11. Apoptosis Induced by DiMeOC-Mg-BCD on MDA-231-MB Breast Cancer

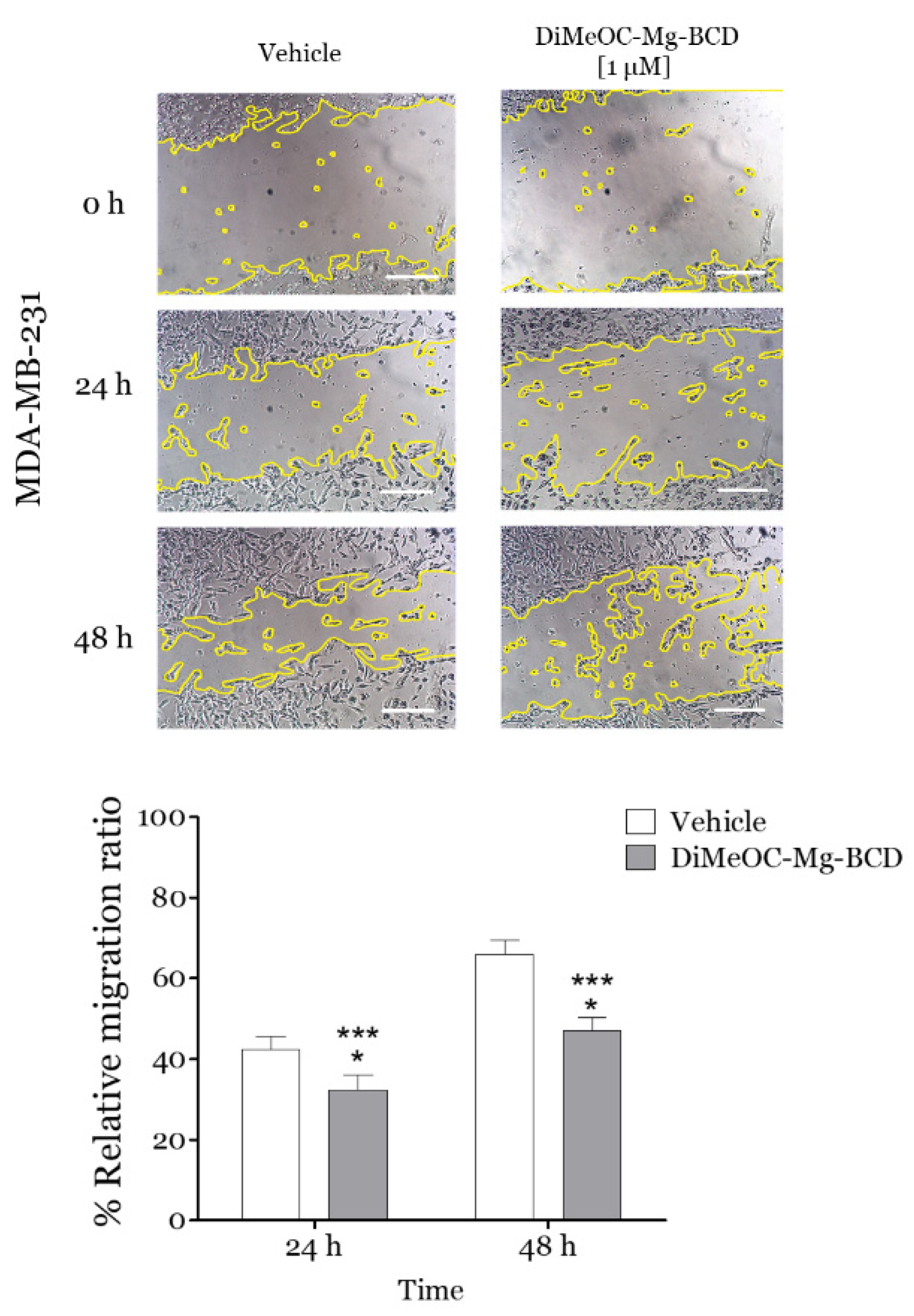

3.12. Effect of DiMeOC-Mg-BCD on MDA-MB-231 Cell Migration (Wound Healing Assay)

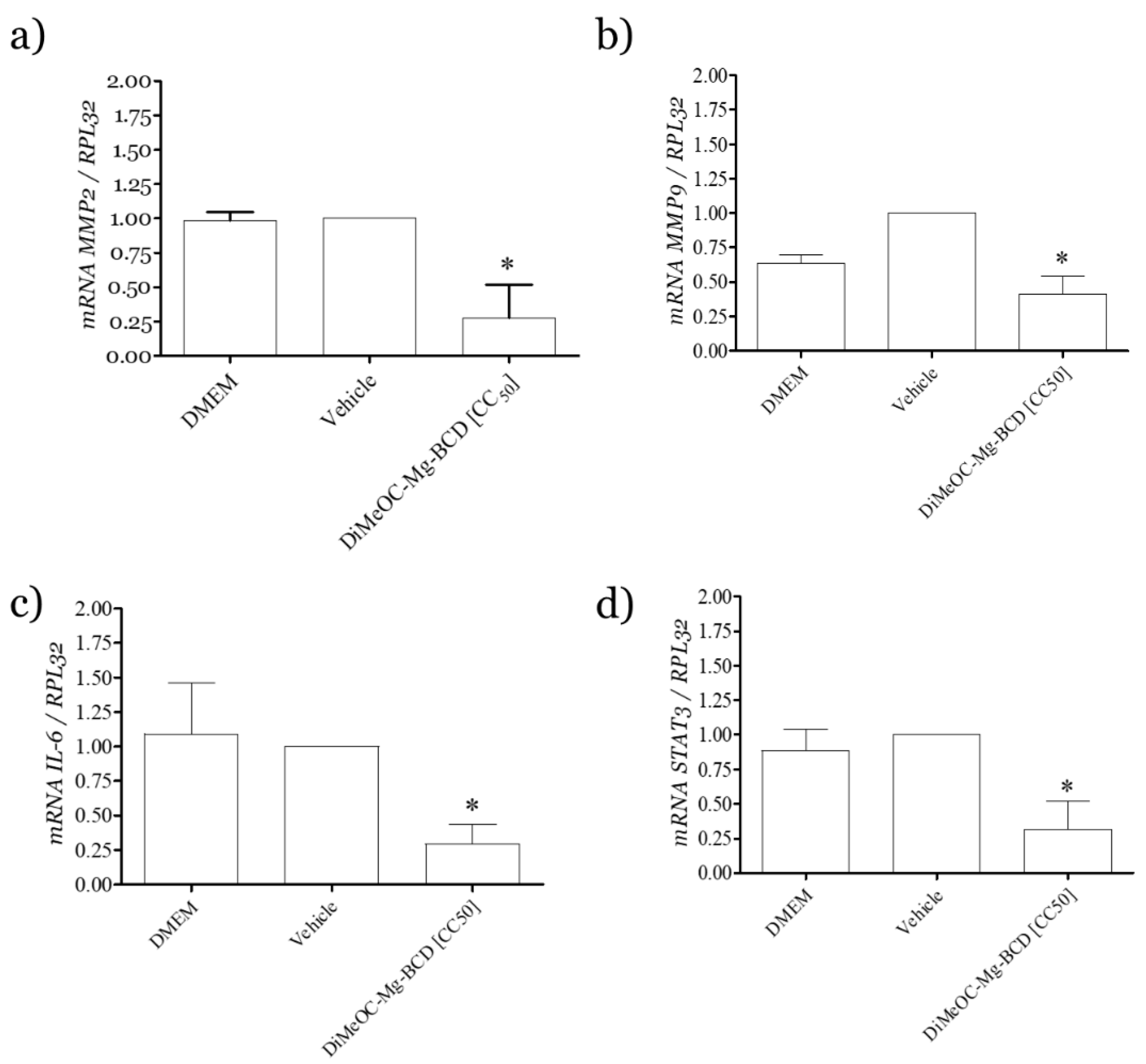

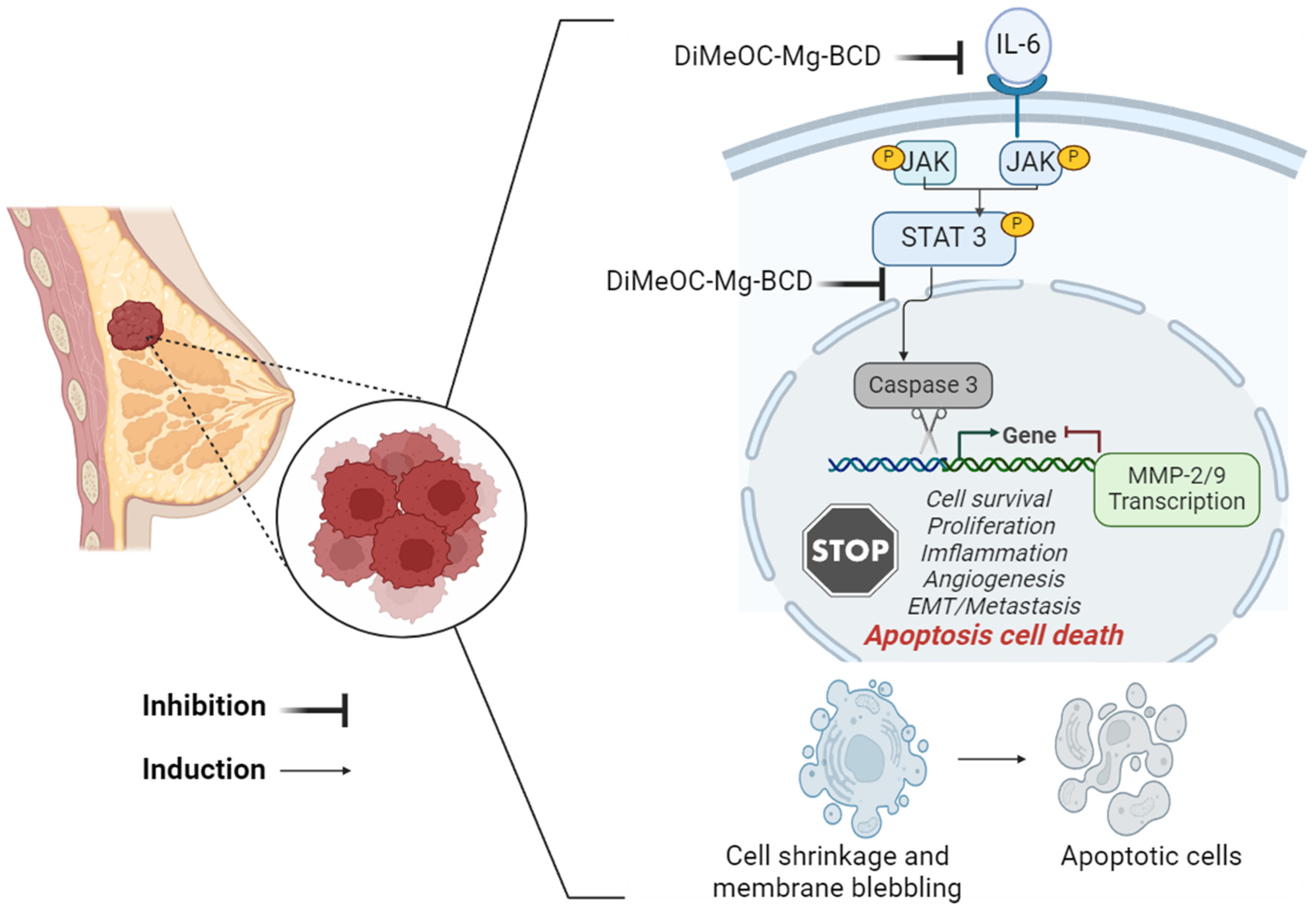

3.13. Effect of DiMeOC-Mg-BCD on MMP-2 , MMP-9 and IL-6 and Total STAT3 Gene Expression on MDA-MB-231

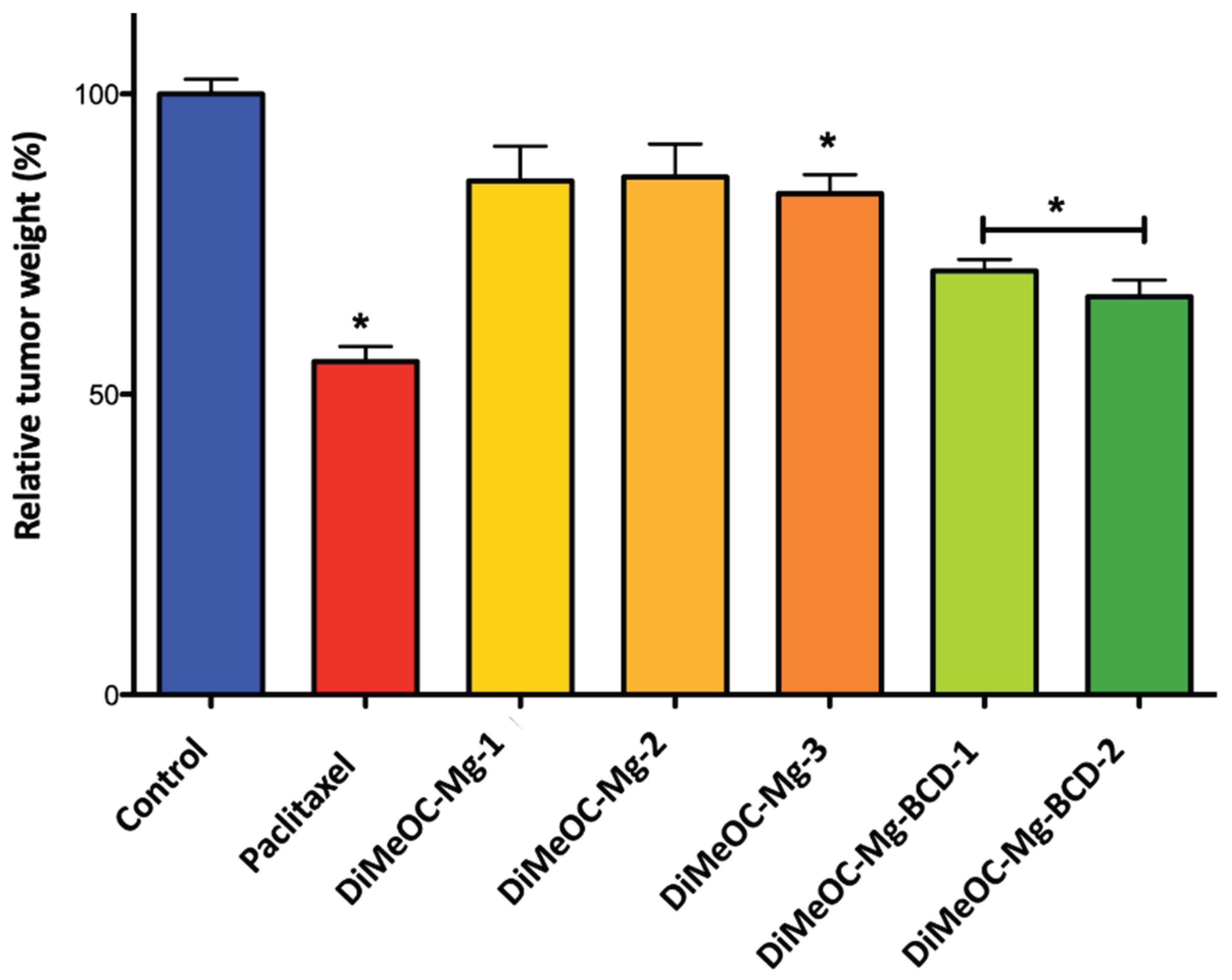

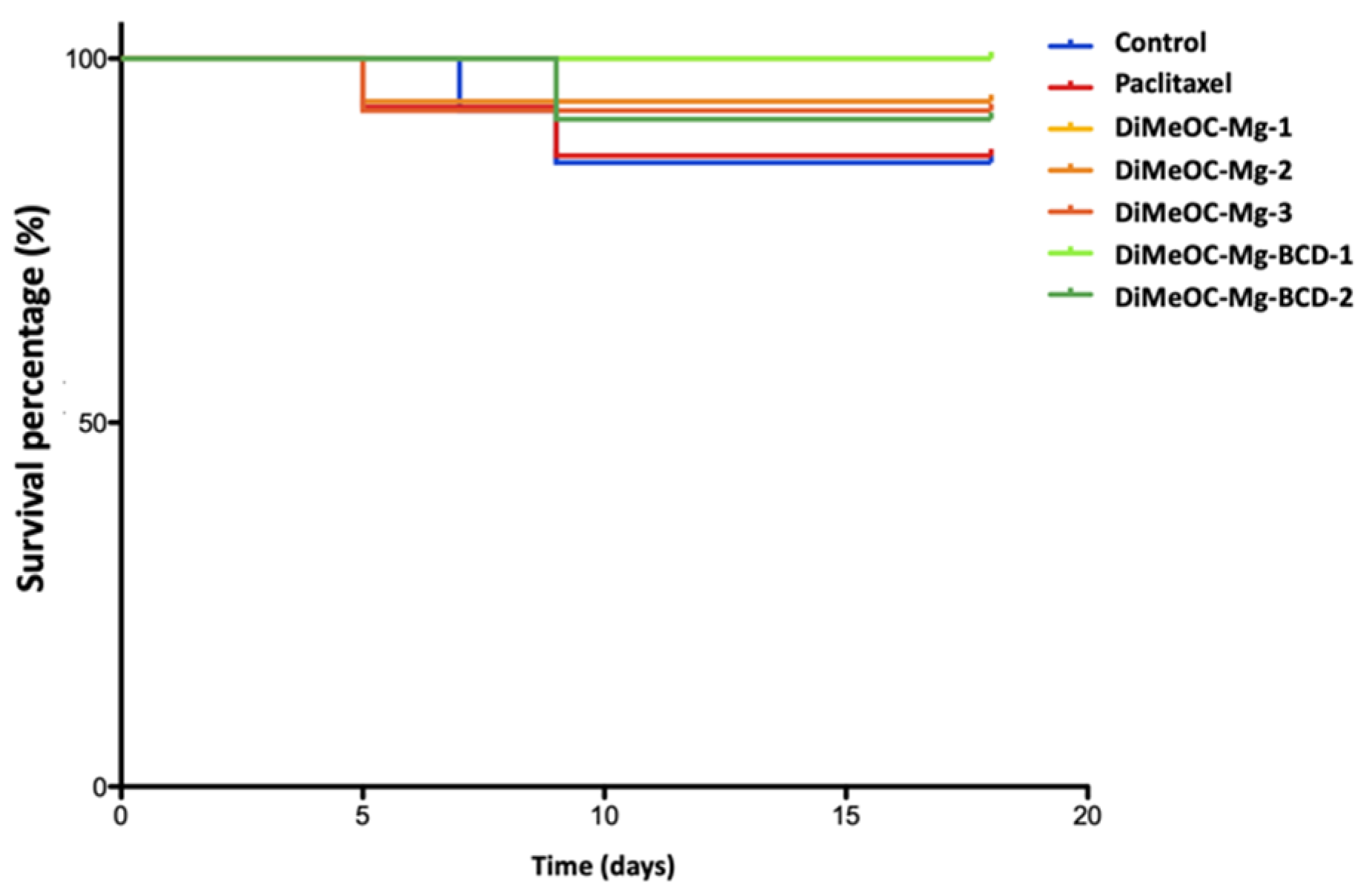

3.14. Antitumoral Activity and Embryotoxicity

4. Materials and Methods

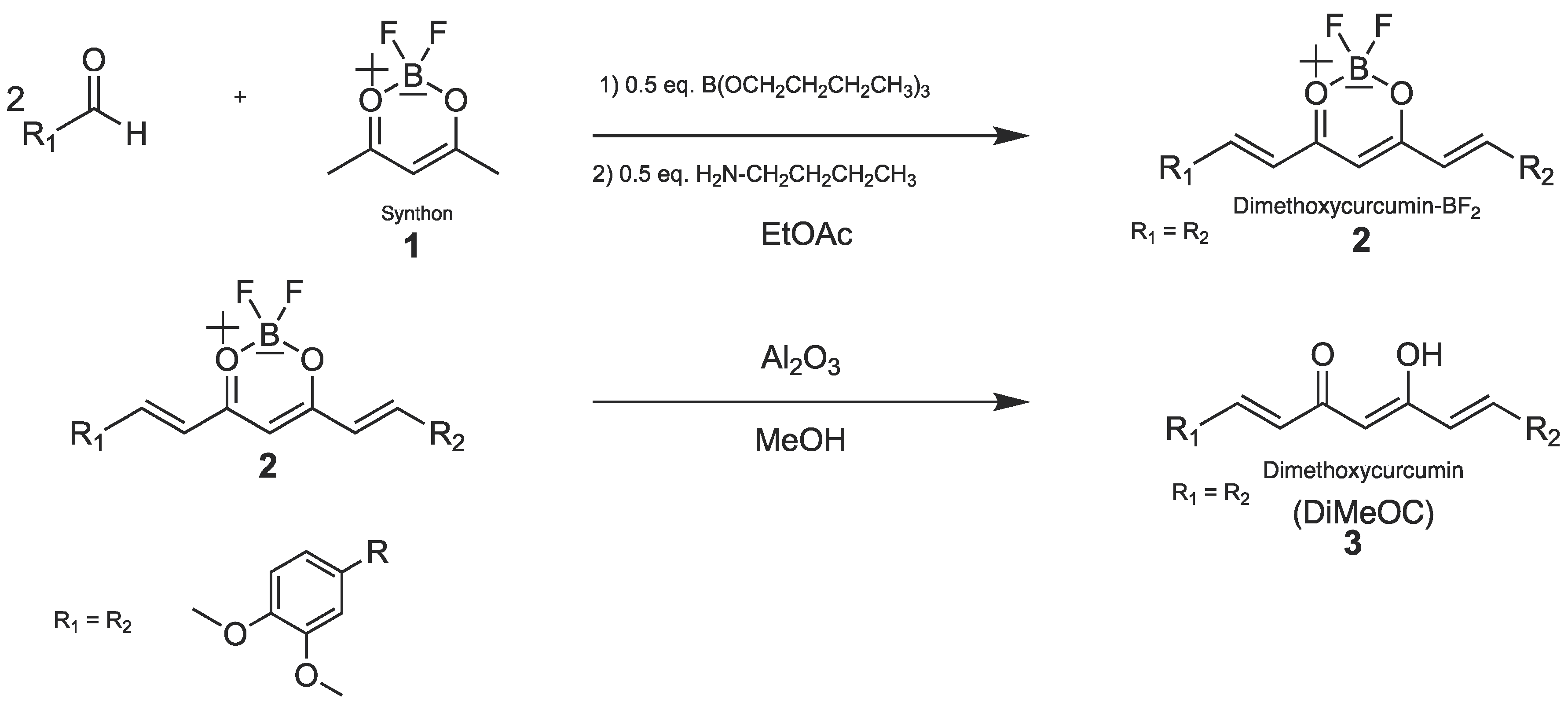

4.1. Synthetic Procedures

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farghadani, R.; Naidu, R. Curcumin: Modulator of Key Molecular Signaling Pathways in Hormone-Independent Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Xiang, L.; Li, T.; Bai, Z. Cancer Hallmarks, Biomarkers and Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes. J Cancer 2016, 7, 1281–1294. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.Q.; Zheng, H.B.; Ma, S.W.; Zhou, G.Z. Activation of Autophagy Promotes the Inhibitory Effect of Curcumin Analog EF-24 against MDA-MB-231 Cancer Cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2024, 38. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ali, A.; Tahir, A.; Bakht, M.A.; Salahuddin; Ahsan, M.J. Molecular Engineering of Curcumin, an Active Constituent of Curcuma Longa L. (Turmeric) of the Family Zingiberaceae with Improved Antiproliferative Activity. Plants 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Orona-ortiz, A.; Medina-torres, L.; Velázquez-moyado, J.A.; Pineda-peña, E.A.; Balderas-lópez, J.L.; Bernad-bernad, M.J.; Carlos, J.; Carvalho, T.; Navarrete, A. Mucoadhesive Effect of Curcuma Longa Extract and Curcumin Decreases the Ranitidine Effect , but Not Bismuth Subsalicylate on Ethanol-Induced Ulcer Model. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 16622–16633. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Fu, Y.; Wang, H.W.; Gong, T.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Z.R. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Activity of Novel Curcumin Analogues. Chinese Chemical Letters 2008, 19, 281–285. [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, A.; Barik, A.; Mishra, B.; Rathinasamy, K.; Pandey, R.; Priyadarsini, K.I. Quantitative Cellular Uptake, Localization and Cytotoxicity of Curcumin in Normal and Tumor Cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2008, 1780, 673–679. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lien, J.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Hung, C.C.; Lin, H.C. Design, Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel Derivatives of Curcuminoids with Cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, X.; Zu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wu, N.; Liang, L.; Yao, L.; Efferth, T. Cytotoxic Activity of Curcumin towards CCRF-CEM Leukemia Cells and Its Effect on DNA Damage. Molecules 2009, 14, 5328–5338. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, N.N.T.; Tran, N.T.N.; Le, P.N.; Nguyen, T.B.T.; Nguyen, N.H.; Bach, L.G.; Doan, V.N.; Tran, H.L.B.; Le, V.T.; et al. Synergic Activity against MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Growth of Nanocurcumin-Encapsulated and Cisplatin-Complexed Nanogels. Molecules 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- Zamrus, S.N.H.; Akhtar, M.N.; Yeap, S.K.; Quah, C.K.; Loh, W.S.; Alitheen, N.B.; Zareen, S.; Tajuddin, S.N.; Hussin, Y.; Shah, S.A.A. Design, Synthesis and Cytotoxic Effects of Curcuminoids on HeLa, K562, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Cancer Cell Lines. Chem Cent J 2018, 12, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Strojny, B.; Grodzik, M.; Sawosz, E.; Winnicka, A.; Kurantowicz, N.; Jaworski, S.; Kutwin, M.; Urbańska, K.; Hotowy, A.; Wierzbicki, M.; et al. Diamond Nanoparticles Modify Curcumin Activity: In Vitro Studies on Cancer and Normal Cells and in Ovo Studies on Chicken Embryo Model. PLoS One 2016, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lateh, L.; Kaewnopparat, N.; Yuenyongsawad, S.; Panichayupakaranant, P. Enhancing the Water-Solubility of Curcuminoids-Rich Extract Using a Ternary Inclusion Complex System: Preparation, Characterization, and Anti-Cancer Activity. Food Chem 2022, 368. [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of Curcumin: Problems and Promises. Mol Pharm 2007, 4, 807–818. [CrossRef]

- Siviero, A.; Gallo, E.; Maggini, V.; Gori, L.; Mugelli, A.; Firenzuoli, F.; Vannacci, A. Curcumin, a Golden Spice with a Low Bioavailability. J Herb Med 2015, 5, 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A.; Gopi, S.; Gopi, S. Biological Activities of Curcuminoids, Other Biomolecules from Turmeric and Their Derivatives – A Review. J Tradit Complement Med 2017, 7, 205–233. [CrossRef]

- Ajavakom, V.; Yutthaseri, T.; Chantanatrakul, R.; Suksamrarm, A.; Ajavakom, A. Curcuminoids in Multi-Component Synthesis. J Heterocycl Chem 2017, 46, 1259–1265. [CrossRef]

- Teymouri, M.; Barati, N.; Pirro, M.; Sahebkar, A. Biological and Pharmacological Evaluation of Dimethoxycurcumin: A Metabolically Stable Curcumin Analogue with a Promising Therapeutic Potential. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 124–140. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Afghah, Z.; Baral, A.; Geiger, J.D.; Chen, X. Dimethoxycurcumin Acidifies Endolysosomes and Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Entry. Frontiers in Virology 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Morales, W.; Machado-Rodriguez, J.C.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Nieto-Camacho, A.; Toscano, R.A.; Soriano-García, M.; Cassani, J.; Enríquez, R.G. A New Family of Homoleptic Copper Complexes of Curcuminoids: Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Properties. Molecules 2019, 24, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Morales, W.; Mirian Estévez-Carmona, M.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Cassani, J.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Escobedo-Martínez, C.; Soriano-García, M.; Reynolds, W.F.; Enríquez, R.G. Full Structural Characterization of Homoleptic Complexes of Diacetylcurcumin with Mg, Zn, Cu, and Mn: Cisplatin-Level Cytotoxicity in Vitro with Minimal Acute Toxicity in Vivo. Molecules 2019, 24. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, K.; Thompson, K.H.; Patrick, B.O.; Storr, T.; Martins, C.; Polishchuk, E.; Yuen, V.G.; McNeill, J.H.; Orvig, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Dual Function Vanadyl, Gallium and Indium Curcumin Complexes for Medicinal Applications. J Inorg Biochem 2005, 99, 2217–2225. [CrossRef]

- Meza-Morales, W.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Arenaza-Corona, A.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Toscano, R.A.; Poveda-Jaramillo, J.C.; Enríquez, R.G. Three New Coordination Geometries of Homoleptic Zn Complexes of Curcuminoids and Their High Antiproliferative Potential. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 8577–8585. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Song, M.; Kim, M.S.; Natarajan, P.; Do, R.; Myung, W.; Won, H.H. An Atlas of Associations between 14 Micronutrients and 22 Cancer Outcomes: Mendelian Randomization Analyses. BMC Med 2023, 21, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yu, Y.; Shi, H.; Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; Hao, Z.; Ren, Y.; Qin, G.; Huang, Y.; Wang, B. Magnesium in Combinatorial With Valproic Acid Suppressed the Proliferation and Migration of Human Bladder Cancer Cells. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.M.V.; Bezerra, D.L.C.; dos Santos, L.R.; de Oliveira Santos, R.; de Sousa Melo, S.R.; Morais, J.B.S.; Severo, J.S.; Vieira, S.C.; do Nascimento Marreiro, D. Magnesium in Breast Cancer: What Is Its Influence on the Progression of This Disease? Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 184, 334–339. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.A.; Shekatkar, M.; Raj, A.T.; Kheur, S. Potential Role of Magnesium in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Pathology and Oncology Research 2020, 26, 2001–2002. [CrossRef]

- Uçmak, Z.G.; Koenhemsi, L.; Uçmak, M.; Yalçın, E.; Ateş, A.; Gönül, R. Evaluation of Serum and Tissue Magnesium, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, and Osteopontin Levels in Dogs with Mammary Tumors with/without Pulmonary Metastases and in Healthy Dogs*. J Elem 2021, 26, 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, D.L.C.; Mendes, P.M.V.; Melo, S.R. de S.; dos Santos, L.R.; Santos, R. de O.; Vieira, S.C.; Henriques, G.S.; Freitas, B. de J. e. S. de A.; Marreiro, D. do N. Hypomagnesemia and Its Relationship with Oxidative Stress Markers in Women with Breast Cancer. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 4466–4474. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, L. Preparation of Curcumin-Loaded Liposomes and Evaluation of Their Skin Permeation and Pharmacodynamics. Molecules 2012, 17, 5972–5987. [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, M.; Nowak, M.; Lazebna, A.; Więcek, K.; Jabłońska, I.; Szpadel, K.; Grzeszczak, A.; Gubernator, J.; Ziółkowski, P. The Comparison of in Vitro Photosensitizing Efficacy of Curcumin-Loaded Liposomes Following Photodynamic Therapy on Melanoma Mug-Mel2, Squamous Cell Carcinoma Scc-25, and Normal Keratinocyte Hacat Cells. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Araya-Sibaja, A.M.; Wilhelm-Romero, K.; Quirós-Fallas, M.I.; Huertas, L.F.V.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R.; Navarro-Hoyos, M. Bovine Serum Albumin-Based Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity Enhancement of Three Main Curcuminoids from Curcuma Longa. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, S.S.; Dunuweera, S.P.; Dunuweera, A.N.; Rajapakse, R.M.G. Synthesis of Curcumin Nanoparticles from Raw Turmeric Rhizome. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 8246–8252. [CrossRef]

- Romero, K.W.; Quirós, M.I.; Huertas, F.V.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R.; Navarro-Hoyos, M.; Araya-Sibaja, A.M. Design of Hybrid Polymeric-Lipid Nanoparticles Using Curcumin as a Model: Preparation, Characterization, and in Vitro Evaluation of Demethoxycurcumin and Bisdemethoxycurcumin-Loaded Nanoparticles. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Shameli, K.; Sazili, A.Q.; Selamat, J.; Kumari, S. Rapid Green Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Arbitrated by Curcumin in an Alkaline Medium. Molecules 2019, 24. [CrossRef]

- Boarescu, P.M.; Boarescu, I.; Bocșan, I.C.; Gheban, D.; Bulboacă, A.E.; Nicula, C.; Pop, R.M.; Râjnoveanu, R.M.; Bolboacă, S.D. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin Nanoparticles on Drug-Induced Acute Myocardial Infarction in Diabetic Rats. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Patro, N.M.; Sultana, A.; Terao, K.; Nakata, D.; Jo, A.; Urano, A.; Ishida, Y.; Gorantla, R.N.; Pandit, V.; Devi, K.; et al. Comparison and Correlation of in Vitro, in Vivo and in Silico Evaluations of Alpha, Beta and Gamma Cyclodextrin Complexes of Curcumin. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem 2014, 78, 471–483. [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Z.; Hmadeh, M.; Abiad, M.G.; Dib, O.H.; Patra, D. Encapsulation of Curcumin in Cyclodextrin-Metal Organic Frameworks: Dissociation of Loaded CD-MOFs Enhances Stability of Curcumin. Food Chem 2016, 212, 485–494. [CrossRef]

- Low, Z.X.; Teo, M.Y.M.; Nordin, F.J.; Dewi, F.R.P.; Palanirajan, V.K.; In, L.L.A. Biophysical Evaluation of Water-Soluble Curcumin Encapsulated in β-Cyclodextrins on Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Benucci, I.; Mazzocchi, C.; Lombardelli, C.; Del Franco, F.; Cerreti, M.; Esti, M. Inclusion of Curcumin in B-Cyclodextrin: A Promising Prospective as Food Ingredient. Food Additives and Contaminants - Part A 2022, 39, 1942–1952. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, N.; Malakzadeh, S. Changes in Chemical Stability and Bioactivities of Curcumin by Forming Inclusion Complexes of Beta- and Gama-Cyclodextrins. Journal of Polymer Research 2020, 27. [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, S.; Leuschner, M.; Bester, M.J.; Serem, J.C. Stability, Morphology, and Effects of In Vitro Digestion on the Antioxidant Properties of Polyphenol Inclusion Complexes with β-Cyclodextrin. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, V.A.; Zanin, G.M.; Durrant, L.R.; Benassi, M.D.T.; Matioli, G. Interaction of Curcumin and Bixin with β-Cyclodextrin: Complexation Methods, Stability, and Applications in Food. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 3348–3357. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Nagpal, M.; Vashistha, V.K.; Arora, R.; Issar, U. Recent Advances in the Antioxidant Activity of Metal-Curcumin Complexes: A Combined Computational and Experimental Review. Free Radic Res 2024, 58, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Miebach, L.; Berner, J.; Bekeschus, S. In Ovo Model in Cancer Research and Tumor Immunology. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Meza-Morales, W.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Estévez-Carmona, M.M.; Enríquez, R.G. High Yield Synthesis of Curcumin and Symmetric Curcuminoids: A “Click” and “Unclick” Chemistry Approach. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, C. The Relationship between MMP-2 and MMP-9 Expression Levels with Breast Cancer Incidence and Prognosis. Oncol Lett 2017, 14, 5865–5870. [CrossRef]

- Arya, P.; Raghav, N. In-Vitro Studies of Curcumin-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex as Sustained Release System. J Mol Struct 2021, 1228, 129774. [CrossRef]

- Pessine, F.B.T.,; Calderini, Adriana.,; Alexandrino., G.L. Review: Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes Probed by NMR Techniques. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 2012, 237–262. [CrossRef]

- Jahed, V.; Zarrabi, A.; Bordbar, A.K.; Hafezi, M.S. NMR (1H, ROESY) Spectroscopic and Molecular Modelling Investigations of Supramolecular Complex of β-Cyclodextrin and Curcumin. Food Chem 2014, 165, 241–246. [CrossRef]

- Kida, T.; Iwamoto, T.; Fujino, Y.; Tohnai, N.; Miyata, M.; Akashi, M. Strong Guest Binding by Cyclodextrin Hosts in Competing Nonpolar Solvents and the Unique Crystalline Structure. Org Lett 2011, 13, 4570–4573. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.; Buera, P.; Mazzobre, F. Novel Trends in Cyclodextrins Encapsulation. Applications in Food Science. Curr Opin Food Sci 2017, 16, 106–113. [CrossRef]

- Yallapu, M.M.; Jaggi, M.; Chauhan, S.C. β-Cyclodextrin-Curcumin Self-Assembly Enhances Curcumin Delivery in Prostate Cancer Cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 113–125. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Bie, C.; Ji, Q.; Ling, H.; Li, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ye, F. Preparation and Characterization of Cyanazine-Hydroxypropyl-Beta-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 26109–26115. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, A.H.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Bethanis, K.; Christoforides, E.; Dudek, M.K.; Zielińska-Pisklak, M.; Pisklak, D.M. 17-β-Estradiol—β-Cyclodextrin Complex as Solid: Synthesis, Structural and Physicochemical Characterization. Molecules 2023, 28. [CrossRef]

- Hagbani, T. Al; Nazzal, S. Curcumin Complexation with Cyclodextrins by the Autoclave Process: Method Development and Characterization of Complex Formation. Int J Pharm 2017, 520, 173–180. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.E. Animal Models for Studying Prevention and Treatment of Breast Cancer. In Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 997–1018 ISBN 9780124158948.

- Stoica, L.; Stoica, B.A.; Olinici, D.; Onofrei, P.; Botez, E.A.; Cotrutz, C.E. Correlations between Morphological Changes Induced by Curcumin and Its Biological Activities. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2018, 59, 65–69.

- Ahmad, I.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, A.; Zughaibi, T.A.; Alhosin, M.; Tabrez, S. Curcumin, Its Derivatives, and Their Nanoformulations: Revolutionizing Cancer Treatment. Cell Biochem Funct 2024, 42. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, K.D.; Martínez, I.; Reyes-Chilpa, R.; Espinoza, B. Mammea Type Coumarins Isolated from Calophyllum Brasiliense Induced Apoptotic Cell Death of Trypanosoma Cruzi through Mitochondrial Dysfunction, ROS Production and Cell Cycle Alterations. Bioorg Chem 2020, 100. [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Ma, Y.; Lin, W. Fluorescent Probes for the Visualization of Cell Viability. Acc Chem Res 2019, 52, 2147–2157. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Xu, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, L.; Sun, H. Curcumin Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells. Exp Ther Med 2018, 16, 1266–1272. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70.

- Kornblatt, A.P.; Nicoletti, V.G.; Travaglia, A. The Neglected Role of Copper Ions in Wound Healing. J Inorg Biochem 2016, 161, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Mai, Z.; Liu, C.; Yin, S.; Cai, Y.; Xia, C. Natural Products in Preventing Tumor Drug Resistance and Related Signaling Pathways. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Manore, S.G.; Doheny, D.L.; Wong, G.L.; Lo, H.W. IL-6/JAK/STAT3 Signaling in Breast Cancer Metastasis: Biology and Treatment. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Alaaeldin, R.; Ali, F.E.M.; Bekhit, A.A.; Zhao, Q.L.; Fathy, M. Inhibition of NF-KB/IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 Pathway and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer Cells by Azilsartan. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Estévez-Carmona, M.M.; Hernández-Ortega, S.; Soriano-García, M.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Orea, L.; Pilotzi, H.; Gnecco, D.; Cassani, J.; Enríquez, R.G. Retro-Curcuminoids as Mimics of Dehydrozingerone and Curcumin: Synthesis, NMR, X-Ray, and Cytotoxic Activity. Molecules 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Mendoza, M.A.; Arias-Olguín, I.I.; Estévez-Carmona, M.M.; Meza-Morales, W.; Alvarez-Ricardo, Y.; Toscano, R.A.; Arenas-Huertero, F.; Cassani, J.; Enríquez, R.G. Non-Cytotoxic Dibenzyl and Difluoroborate Curcuminoid Fluorophores Allow Visualization of Nucleus or Cytoplasm in Bioimaging. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Mestrelab Research. MNova Software. Available Online https://mestrelab.com/Download/Mnova/ . Accesed on March, 10, 2024.

- Higuchi T., S.F.M.L., K.T., R.J.H. Solubility Determination of Barely Aqueous-Soluble Organic Solids. J Pharm Sci 1979, 68, 1267–1272.

- Jadhav, B.K.; Mahadik, K.R.; Paradkar, A.R. Development and Validation of Improved Reversed Phase-HPLC Method for Simultaneous Determination of Curcumin, Demethoxycurcumin and Bis-Demethoxycurcumin. Chromatographia 2007, 65, 483–488. [CrossRef]

- Vichai, V.; Kirtikara, K. Sulforhodamine B Colorimetric Assay for Cytotoxicity Screening. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 1112–1116. [CrossRef]

- Rueden, C.T.; Schindelin, J.; Hiner, M.C.; DeZonia, B.E.; Walter, A.E.; Arena, E.T.; Eliceiri, K.W. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next Generation of Scientific Image Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 529. [CrossRef]

- Ashland, OR.; Becton-Dickinson; and Company. FlowJoTM Software for Mac Software Application Version 7.3.2. Available Online: https://www.flowjo.com. Accesed March, 10, 2024.

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform Extraction. Anal Biochem 1987, 162, 156–159.

- Noyola-Martínez, N.; Halhali, A.; Zaga-Clavellina, V.; Olmos-Ortiz, A.; Larrea, F.; Barrera, D. A Time-Course Regulatory and Kinetic Expression Study of Steroid Metabolizing Enzymes by Calcitriol in Primary Cultured Human Placental Cells. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2017, 167, 98–105. [CrossRef]

- GraphPad;Software;Inc.Accessed 10, March, 2024. http://www.graphpad.com/Faq/Viewfaq.Cfm?Faq=1362.

- SigmaPlot Statistical Software. Jandel Corporation, Las Vegas. Online: https://sigmaplot.software.informer.com/11.0. Accesed 10, March, 2024.

- Weiss, H.; Reichel, J.; Görls, H.; Schneider, K.R.A.; Micheel, M.; Pröhl, M.; Gottschaldt, M.; Dietzek, B.; Weigand, W. Curcuminoid-BF2 Complexes: Synthesis, Fluorescence and Optimization of BF2 Group Cleavage. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 2017, 13, 2264–2272. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Chen, J.; Chojnacki, J.; Zhang, S. BF3·OEt2-Promoted Concise Synthesis of Difluoroboron-Derivatized Curcumins from Aldehydes and 2,4-Pentanedione. Tetrahedron Lett 2013, 54, 2070–2073. [CrossRef]

| Proton | BCD free (ppm) | BCD complex (ppm) | Δδppm |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 5.11 | 5.06 | -0.05 |

| H2 | 3.68 | 3.63 | -0.05 |

| H3 | 3.99 | 3.93 | -0.06 |

| H4 | 3.62 | 3.58 | -0.04 |

| H5 H6 |

3.88 3.91 |

3.80 3.89 |

-0.08 -0.02 |

| Compound | Dfree | Dinclusion complex | HOD |

| DiMeOC-Mg | 1.20 x10-10 cm2/s | 9.82 x10-11 cm2/s | 6.61 x10-10 cm2/s |

| BCD | 9.6 x10-11 cm2/s | 8.34 x10-11 cm2/s | 7.5 x10-10 cm2/s |

| Compounds | Solubility μg /mL |

|---|---|

| DiMeOC-Mg | 15.6 ± 0.048 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-BCD | 98.2 ± 0.038 |

| Compounds | MDA-MB-231 |

|---|---|

| DiMeOC | >100 |

| DiMeOC-Mg | 22.04 ± 0.06 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-BCD | 10.73 ± 0.1 |

| Group | Injected concentration (μM) |

In ovo final dose (mg/Kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Control (DMSO 1%) | - | - |

| Paclitaxel | 10.0 | 0.014 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-1 | 276.1 | 0.375 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-2 | 552.3 | 0.750 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-3 | 1104.5 | 1.5 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-BCD-1 | 10 | 0.065 |

| DiMeOC-Mg-BCD-2 | 100 | 0.650 |

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | *Probe | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPL32 | GAAGTTCCTGGTCCACAACG | GAGCGATCTCGGCACAGTA | 17 | NM_000994.3 |

| MMP-2 | ATAACCTGGATG CCGTCGT | AGGCACCCTTGAA GAAGTAGC | 70 | NM_001302510.1 |

| MMP-9 | GCCACCCGAGTGTAACCATA | GAACCAATCTCAC CGACAGG | 6 | NM_004994.2 |

| IL-6 | GATGAGTACAAAAGTCCTGATCCA | CTGCAGCCACTGGTTCTGT | 40 | NM 000600.1 |

| STAT3 | CCTCTGCCGGAGAAACAGT | CATTGGGAAGCTGTCACTGTAG | 1 | NM_139276.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).