Submitted:

01 April 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Hypothesis 1

3.2. Hypothesis 2

3.3. Hypothesis 3

3.4. Hypothesis 4

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

4.2. Dependent Variables

4.3. Independent Variables

4.4. Empirical Method

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Summary Statistics

5.2. The Effect of Low-Carbon Innovations on Default Risks

5.3. Heterogeneity Effects

5.4. Endogeneity Issues

5.5. Mechanism of Low-Carbon Innovation Effects

6. Conclusions

- This study finds that low-carbon transition innovation significantly decreases default risk as measured by distance-to-default. This result was tested with three low-carbon innovation measurements, including quantity, generality, and importance. The result is robust with alternative normalization methods and default risk measurements.

- As a heterogeneous analysis, it is concluded that firms under climate policy treatment will obtain lower innovation effects on default risks compared with other firms.

- Innovation time costs are taken as instrumental variables to test endogeneity and our results are robust under the IV-2SLS model.

- This paper finds that the three identified mechanisms can explain how low-carbon innovations affect the default risk, including stakeholder attention, productivity, and technological spillovers.

| 1 | CCER is a database of economics and finance, which is built by Sinofin and the China

Centre for Economic Research, Peking University. |

| 2 | CNRDS is the Chinese Research Data Services Platform, which provides

high-quality and open data for Chinese economic research. |

| 3 | CSMAR is the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database, which

provides various datasets for the Chinese stock market. |

References

- Zhu, J.; Fan, Y.; Deng, X.; Xue, L. Low-Carbon Innovation Induced by Emissions Trading in China. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monasterolo, I. Climate Change and the Financial System. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Herbohn, K.; Clarkson, P. Carbon Risk, Carbon Risk Awareness and the Cost of Debt Financing. J Bus Ethics 2018, 150, 1151–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, S.; Kelly, B.; Stroebel, J. Climate Finance. Annual Review of Financial Economics 2021, 13, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, S.; Mandel, A.; Monasterolo, I.; Roncoroni, A. Climate Credit Risk and Corporate Valuation. In Climate credit risk and corporate valuation: Battiston, Stefano| uMandel, Antoine| uMonasterolo, Irene| uRoncoroni, Alan; [Sl]: SSRN, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, D. The Climate Risk Premium: How Uncertainty Affects the Social Cost of Carbon. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 2021, 8, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S.; Gollier, C.; Kessler, L. The Climate Beta. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2018, 87, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Du, P.; Ye, J. Can Low-Carbon Technological Innovation Truly Improve Enterprise Performance? The Case of Chinese Manufacturing Companies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 293, 125949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannier, C.E.; Bofinger, Y.; Rock, B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Credit Risk. Finance Research Letters 2022, 44, 102052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiullah, S.; Phan, D.H.B.; Kabir, M.N. Green Innovation and Corporate Default Risk 2022.

- Gutiérrez-López, C.; Castro, P.; Tascón, M.T. How Can Firms’ Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy Affect the Distance to Default? Research in International Business and Finance 2022, 62, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-H.; Lee, H.-H.; Liu, A.Z.; Zhang, Z. Corporate Innovation, Default Risk, and Bond Pricing. Journal of Corporate Finance 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meles, A.; Salerno, D.; Sampagnaro, G.; Verdoliva, V.; Zhang, J. The Influence of Green Innovation on Default Risk: Evidence from Europe. International Review of Economics & Finance 2023, 84, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunday, G.; Ulusoy, G.; Kilic, K.; Alpkan, L. Effects of Innovation Types on Firm Performance. International Journal of Production Economics 2011, 133, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqbi, E.A.; Alshurideh, M.; AlHamad, A.; Al, B. The Impact of Innovation on Firm Performance: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Innovation 2020, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.S. Association between Technological Innovation and Firm Performance in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Factors. International Journal of Innovation Science 2019, 11, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shang, Y.; Yu, W.; Liu, F. Intellectual Capital, Technological Innovation and Firm Performance: Evidence from China’s Manufacturing Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nasr, H.; Bouslimi, L.; Zhong, R. Do Patented Innovations Reduce Stock Price Crash Risk?*. International Review of Finance 2021, 21, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.M.; Paunov, C. THE RISKS OF INNOVATION: ARE INNOVATING FIRMS LESS LIKELY TO DIE? THE REVIEW OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Viardot, E.; Sovacool, B.K.; Geels, F.W.; Xiong, Y. Innovation and Climate Change: A Review and Introduction to the Special Issue. Technovation 2022, 117, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viardot, E. The Role of Cooperatives in Overcoming the Barriers to Adoption of Renewable Energy. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, C.; Pontoni, F. Investigating Policy and R&D Effects on Environmental Innovation: A Meta-Analysis. Ecological Economics 2015, 118, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Matisoff, D.C.; Kingsley, G.A.; Brown, M.A. Understanding Renewable Energy Policy Adoption and Evolution in Europe: The Impact of Coercion, Normative Emulation, Competition, and Learning. Energy Research & Social Science 2019, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacal Arantegui, R.; Jäger-Waldau, A. Photovoltaics and Wind Status in the European Union after the Paris Agreement. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 81, 2460–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Akcigit, U.; Hanley, D.; Kerr, W. Transition to Clean Technology. Journal of Political Economy 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J.; Caldeira, K.; Matthews, H.D. Future CO2 Emissions and Climate Change from Existing Energy Infrastructure. Science 2010, 329, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Li, P.; Yan, Z. Do Green Technology Innovations Contribute to Carbon Dioxide Emission Reduction? Empirical Evidence from Patent Data. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2019, 146, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.J.; Yang, C.; Sheu, C. The Link between Eco-Innovation and Business Performance: A Taiwanese Industry Context. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 64, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z. Corporate Culture, Environmental Innovation and Financial Performance. Business Strategy and the Environment 2018, 27, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-W.; Li, Y.-H. Green Innovation and Performance: The View of Organizational Capability and Social Reciprocity. J Bus Ethics 2017, 145, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, L. de A.; Bansi, A.C.; Alves, M.F.R.; Galina, S.V.R. Take Your Time: Examining When Green Innovation Affects Financial Performance in Multinationals. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 233, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba de Oliveira, J.A.; Cruz Basso, L.F.; Kimura, H.; Sobreiro, V.A. Innovation and Financial Performance of Companies Doing Business in Brazil. International Journal of Innovation Studies 2018, 2, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. How to Reconcile Environmental and Economic Performance to Improve Corporate Sustainability: Corporate Environmental Strategies in the European Paper Industry. Journal of Environmental Management 2005, 76, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misani, N.; Pogutz, S. Unraveling the Effects of Environmental Outcomes and Processes on Financial Performance: A Non-Linear Approach. Ecological Economics 2015, 109, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpp, C.; Guenther, T. Too Little or Too Much? Exploring U-Shaped Relationships between Corporate Environmental Performance and Corporate Financial Performance. Business Strategy and the Environment 2017, 26, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N. Green Innovation and Financial Performance: An Institutional Approach. Organization & Environment 2013, 26, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aastvedt, T.M.; Behmiri, N.B.; Lu, L. Does Green Innovation Damage Financial Performance of Oil and Gas Companies? Resources Policy 2021, 73, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahen-Fourot, L.; Campiglio, E.; Godin, A.; Kemp-Benedict, E.; Trsek, S. Capital Stranding Cascades: The Impact of Decarbonisation on Productive Asset Utilisation. Energy Economics 2021, 103, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon-Smith, K.; Greenhalgh, P. Suspect Foundations: Developing an Understanding of Climate-Related Stranded Assets in the Global Real Estate Sector. Energy Research & Social Science 2019, 54, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, J.; McInerney, C.; Ó Gallachóir, B.; Hickey, C.; Deane, P.; Deeney, P. Quantifying Stranding Risk for Fossil Fuel Assets and Implications for Renewable Energy Investment: A Review of the Literature. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 116, 109402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, J.; Goutte, S.; Ji, Q.; Guesmi, K. Green Finance and the Restructuring of the Oil-Gas-Coal Business Model under Carbon Asset Stranding Constraints. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Yan, Y.; Hao, J.; Wu, J. (George) Retail Investor Attention and Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from China. Energy Economics 2022, 115, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. The Dynamic Interaction between Investor Attention and Green Security Market: An Empirical Study Based on Baidu Index. China Finance Review International 2021, 13, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Kang, Y.; Guo, K.; Sun, X. The Relationship between Air Pollution, Investor Attention and Stock Prices: Evidence from New Energy and Polluting Sectors. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhou, X.; Peng, C.; Zhu, H. Going Green: Insight from Asymmetric Risk Spillover between Investor Attention and pro-Environmental Investment. Finance Research Letters 2022, 47, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Xiong, X. Retail Investor Attention and Firms’ Idiosyncratic Risk: Evidence from China. International Review of Financial Analysis 2021, 74, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Si, H.; He, X. Does Low-Carbon City Construction Improve Total Factor Productivity? Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Chen, Y.; Lin, B. Uncovering the Role of Renewable Energy Innovation in China’s Low Carbon Transition: Evidence from Total-Factor Carbon Productivity. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2023, 101, 107128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xia, Q.; Li, Z. Green Innovation and Enterprise Green Total Factor Productivity at a Micro Level: A Perspective of Technical Distance. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 344, 131070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İmrohoroğlu, A.; Tüzel, Ş. Firm-Level Productivity, Risk, and Return. Management Science 2014, 60, 2073–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, P.; Lima, F. Interdependence and Spillovers: Is Firm Performance Affected by Others’ Innovation Activities?

- Aiello, F.; Cardamone, P. R&D Spillovers and Firms’ Performance in Italy: Evidence from a Flexible Production Function. Empirical Economics 2008, 34, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Gao, H.; Sun, F. The Impact of Dual Network Structure on Firm Performance: The Moderating Effect of Innovation Strategy. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2020, 32, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Do Patent Citations Indicate Knowledge Linkage? The Evidence from Text Similarities between Patents and Their Citations. Journal of Informetrics 2017, 11, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, R.; Lungeanu, A.; DeChurch, L.; Contractor, N. Patent Similarity Data and Innovation Metrics. J Empirical Legal Studies 2020, 17, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.C. On the Pricing of Corporate Debt: The Risk Structure of Interest Rates. The Journal of Finance 1974, 29, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, S.T.; Shumway, T. Forecasting Default with the Merton Distance to Default Model. The Review of Financial Studies 2008, 21, 1339–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, S.; Cassiman, B.; Gomez, J.C. Text Matching to Measure Patent Similarity. Strategic Management Journal 2018, 39, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Rudik, I.; Zou, E.Y.; Johnston, A.; Rodewald, A.D.; Kling, C.L. Conservation Cobenefits from Air Pollution Regulation: Evidence from Birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2020, 117, 30900–30906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zheng, X.; Liao, J.; Niu, J. Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy and Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment. International Review of Economics & Finance 2024, 89, 1248–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. Can the Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy Promote Firms’ Low-Carbon Innovation: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0277879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Pan, Y.; Sensoy, A.; Uddin, G.S.; Cheng, F. Green Credit Policy and Firm Performance: What We Learn from China. Energy Economics 2021, 101, 105415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Shao, S. Can Green Credit Policy Improve Environmental Quality? Evidence from China. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 298, 113445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cai, X.; Huang, S.; Tian, S.; Lei, H. Technological Factors and Total Factor Productivity in China: Evidence Based on a Panel Threshold Model. China Economic Review 2019, 54, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

| Distance-to-default (DD) | The measurement of default risks developed by the Merton model [57]; the more the DD is, the less is the default risk. |

| Current ratio | Current ratio is the ratio of current assets and current liabilities, which measures the ability to pay short-term obligations within one year. |

| Debt-to-asset ratio | Debt-to-asset ratio is total liabilities divided by total assets, which measures the level of debt. |

| Total asset turnover | Total asset turnover ratio is the ratio of net sales divided by the average total assets, which measures the efficiency of generating revenue and sales. |

| Net return on assets (ROA) | The return on net assets is the ratio of net income divided by average net assets, which measures the profitability of the business. |

| Return on equity (ROE) | The return on equity is the ratio of net income divided by average shareholders’ equity, which measures the profitability and efficiency of generating profits. |

| Total asset change | Total asset change is the percentage of total asset change, which measures the growth of assets. |

| ROA change | ROA change is the percentage of ROA change, which measures the growth of profitability. |

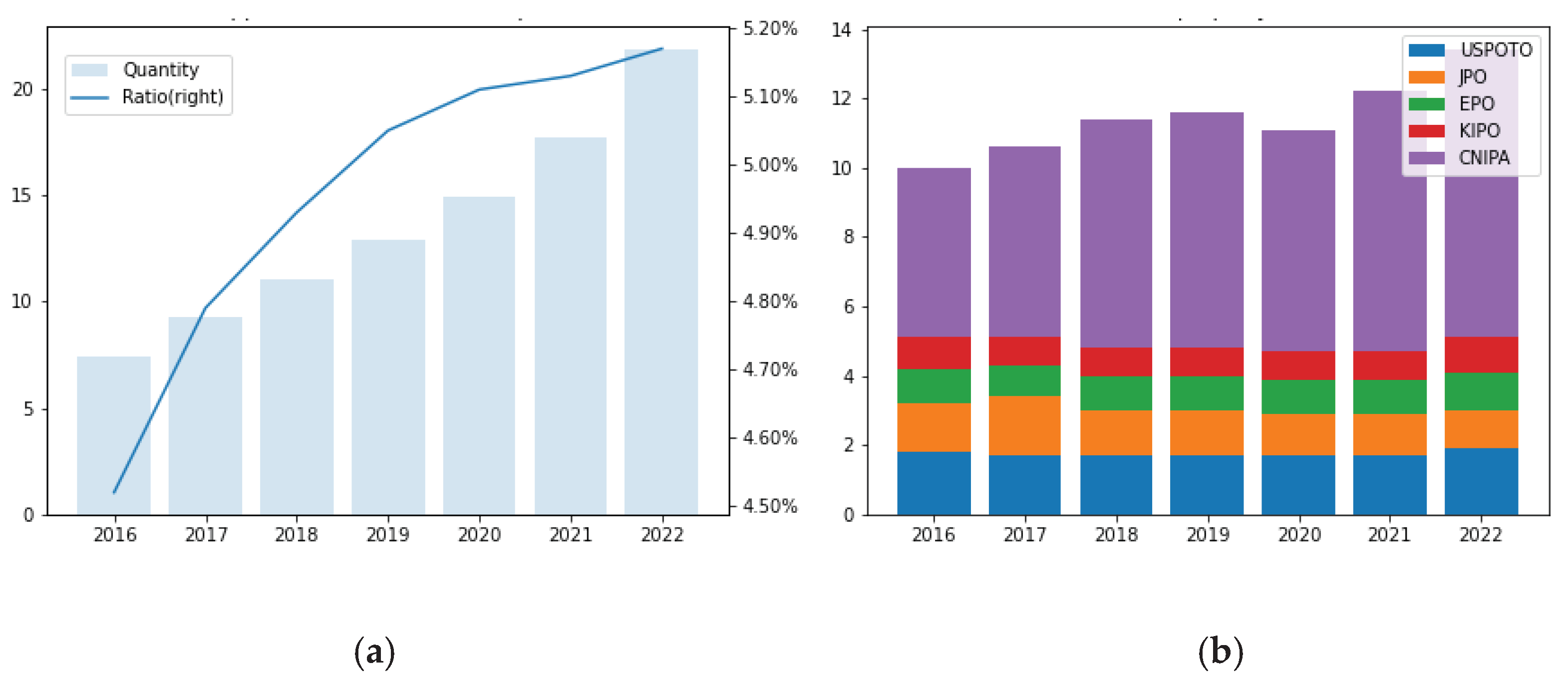

| Low-carbon patent quantity | The quantity measurement of low-carbon patents, denoting the number of climate change transition innovations. |

| Low-carbon patent generality | The generality measurement of low-carbon patent, denoting the intensity of broad usage of climate transition. |

| Low-carbon patent importance | The importance measurement of low-carbon patent citations, denoting the quality and importance for climate change transition innovations. |

| Low-carbon patent time costs | The difference between the application date and the approval date of the low-carbon patent in the industry level, indicating time costs of innovations. |

| Investor attention score | The annual median of daily Baidu search index for listed firms. |

| Total factor productivity | Total factor productivity (TFP) is the efficiency of productive activities over time, a productivity indicator that measures total output per unit of total inputs and is calculated with the generalized method of moments. |

| Patent centrality | The centrality degree of patent similarity network to describe the technology spillovers. |

| Variables | Signal | Observations | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-to-default | DD | 23,580 | 8.683 | 5.953 | 0 | 315.6 |

| Current ratio | CR | 23,580 | 2.620 | 3.145 | 0.00592 | 80.66 |

| Asset loan rate | AL | 23,580 | 0.428 | 1.201 | 0.00836 | 178.3 |

| Total asset turnover | TAT | 23,580 | 0.643 | 0.529 | -0.0479 | 12.37 |

| Net ROA | ROA | 23,580 | 0.0396 | 0.144 | -9.117 | 12.21 |

| ROE | ROE | 23,580 | 0.0429 | 1.229 | -174.9 | 14.02 |

| Total asset change | TAG | 23,580 | 0.217 | 0.710 | -0.961 | 37.03 |

| ROA change | ROAG | 23,580 | -7.743 | 362.8 | -36,206 | 7,310 |

| Low-carbon patent quantity | LCQ | 23,580 | 0.790 | 8.935 | 0 | 417 |

| Low-carbon patent generality | LCG | 23,580 | 0.860 | 9.621 | 0 | 450 |

| Low-carbon patent importance | LCI | 23,580 | 1.260 | 15.26 | 0 | 750 |

| Low-carbon patent time costs | LCT | 23,580 | 23.45 | 73.61 | 0 | 1,250 |

| Total factor productivity | TFP | 23,580 | 3.119 | 1.408 | 0 | 9.391 |

| Investor attention score | IA | 23,580 | 942.7 | 1,423 | 0 | 44,965 |

| Patent centrality | PC | 23,580 | 0.0325 | 0.0703 | 0 | 0.888 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCQ | 0.007** | 0.007** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| LCG | 0.007** | 0.007** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.003) | |||||

| LCI | 0.004* | 0.004* | ||||

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |||||

| CR | 0.273*** | 0.271*** | 0.273*** | 0.271*** | 0.273*** | 0.271*** |

| (0.048) | (0.049) | (0.048) | (0.049) | (0.048) | (0.049) | |

| AL | -0.029* | -0.021 | -0.029* | -0.021 | -0.029* | -0.021 |

| (0.016) | (0.022) | (0.016) | (0.022) | (0.016) | (0.022) | |

| TAT | 0.356** | 0.352* | 0.356** | 0.351* | 0.358** | 0.353* |

| (0.177) | (0.180) | (0.177) | (0.180) | (0.177) | (0.180) | |

| ROA | -0.478*** | -0.494*** | -0.478*** | -0.494*** | -0.476** | -0.492*** |

| (0.185) | (0.187) | (0.185) | (0.187) | (0.185) | (0.187) | |

| ROE | -0.009 | -0.010 | -0.009 | -0.010 | -0.009 | -0.010 |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.009) | |

| TAG | 0.316*** | 0.339*** | 0.316*** | 0.339*** | 0.316*** | 0.339*** |

| (0.081) | (0.091) | (0.081) | (0.091) | (0.081) | (0.091) | |

| ROAG | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 5.954*** | 10.234*** | 5.954*** | 10.234*** | 5.956*** | 10.235*** |

| (0.166) | (1.348) | (0.166) | (1.348) | (0.166) | (1.348) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Prov FE | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Ind FE | NO | YES | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.050 | 0.053 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| z-score normalization | Min–max normalization | |||||

| LCQ | 0.005*** | 3.042*** | ||||

| (0.002) | (1.187) | |||||

| LCG | 0.005** | 3.056** | ||||

| (0.002) | (1.251) | |||||

| LCI | 0.005* | 3.228* | ||||

| (0.002) | (1.801) | |||||

| CR | 0.016*** | 0.016*** | 0.016*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| AL | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.000 | -0.000 | -0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| TAT | 0.020* | 0.020* | 0.021* | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ROA | -0.029*** | -0.029*** | -0.029*** | -0.000*** | -0.000*** | -0.000*** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ROE | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.000 | -0.000 | -0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| TAG | 0.020*** | 0.020*** | 0.020*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ROAG | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.003*** | 0.003*** | 0.003*** |

| (0.078) | (0.078) | (0.078) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.053 | |

| (1) Merton |

(2) Merton |

(3) Merton |

(4) KMV |

(5) KMV |

(6) KMV |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCQ | 0.009*** | 0.003*** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.001) | |||||

| LCG | 0.009*** | 0.003*** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.001) | |||||

| LCI | 0.006*** | 0.004*** | ||||

| (0.002) | (0.001) | |||||

| CR | 0.325*** | 0.325*** | 0.325*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** | 0.068*** |

| (0.055) | (0.055) | (0.055) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | |

| AL | -0.023 | -0.023 | -0.023 | -0.048*** | -0.048*** | -0.048*** |

| (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.018) | |

| TAT | 0.498** | 0.498** | 0.500** | 0.173 | 0.173 | 0.174 |

| (0.199) | (0.199) | (0.199) | (0.120) | (0.120) | (0.120) | |

| ROA | 0.079 | 0.079 | 0.081 | 0.412*** | 0.412*** | 0.413*** |

| (0.253) | (0.253) | (0.253) | (0.155) | (0.155) | (0.155) | |

| ROE | -0.013** | -0.013** | -0.013** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| TAG | 0.259*** | 0.259*** | 0.259*** | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| (0.086) | (0.086) | (0.086) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| ROAG | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 11.399*** | 11.399*** | 11.400*** | 2.987** | 2.987** | 2.988** |

| (1.457) | (1.457) | (1.458) | (1.384) | (1.384) | (1.386) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.076 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Innovation= | Quantity | Generality | Importance |

| LCCPInnovation | -0.018* | -0.016* | 0.006** |

| (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.003) | |

| LCCP | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.158 |

| (0.559) | (0.559) | (0.558) | |

| Innovation | 0.024** | 0.022** | 0.000 |

| (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.001) | |

| CR | 0.273*** | 0.273*** | 0.273*** |

| (0.048) | (0.048) | (0.048) | |

| AL | -0.029* | -0.029* | -0.029* |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| TAT | 0.355** | 0.355** | 0.356** |

| (0.177) | (0.177) | (0.177) | |

| ROA | -0.479*** | -0.479*** | -0.476*** |

| (0.185) | (0.185) | (0.185) | |

| ROE | -0.009 | -0.009 | -0.009 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| TAG | 0.316*** | 0.316*** | 0.316*** |

| (0.081) | (0.081) | (0.081) | |

| ROAG | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 5.858*** | 5.858*** | 5.866*** |

| (0.349) | (0.349) | (0.349) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Innovation= | Quantity | Generality | Importance |

| PolicyInnovation | -0.062*** | -0.052*** | -0.049* |

| (0.020) | (0.018) | (0.029) | |

| Policy | 1.309** | 1.309** | 1.376** |

| (0.618) | (0.619) | (0.610) | |

| Innovation | 0.007** | 0.006** | 0.003 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| CR | 0.145*** | 0.145*** | 0.146*** |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | |

| AL | -0.030 | -0.030 | -0.030 |

| (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| TAT | -0.262** | -0.262** | -0.262** |

| (0.125) | (0.125) | (0.125) | |

| ROA | -0.243 | -0.244 | -0.241 |

| (0.158) | (0.158) | (0.158) | |

| ROE | -0.008 | -0.008 | -0.007 |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| TAG | -0.050 | -0.050 | -0.050 |

| (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | |

| ROAG | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 7.636*** | 7.636*** | 7.634*** |

| (0.604) | (0.604) | (0.603) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.272 | 0.272 | 0.271 |

| Quantity | Generality | Importance | ||||

| 1st-stage | 2nd-stage | 1st-stage | 2nd-stage | 1st-stage | 2nd-stage | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| LCT | 0.047** | 0.052** | -0.058** | |||

| (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.023) | ||||

| Innovations | 0.187** | 0.174** | -0.156* | |||

| (0.097) | (0.090) | (0.081) | ||||

| Obs | 23,059 | 23,059 | 23,059 | 23,059 | 23,059 | 23,059 |

| 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.126 | 0.126 | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Instrument Validity Tests for IV regression | ||||||

| (i) F-test for excluded instrument in first stage | ||||||

| Sanderson–Windmeijer F-test | 5.06** | 5.12** | 6.17** | |||

| (ii) Under-identification test | ||||||

| Kleibergen–Paap LM statistic | 4.891** | 4.941** | 6.04** | |||

| (iii)Weak identification test | ||||||

| Cragg–Donald–Wald F statistic | 201.65 | 201.79 | 113.31 | |||

| Stock–Yogo weak ID test | ||||||

| 10% max IV size | 16.38 | 16.38 | 16.38 | |||

| 15% max IV size | 8.96 | 8.96 | 8.96 | |||

| 20% max IV size | 6.66 | 6.66 | 6.66 | |||

| 25% max IV size | 5.53 | 5.53 | 5.53 | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| investor attention | DD | investor attention | DD | investor attention | DD | |

| IA | -0.001*** | -0.001*** | -0.001*** | |||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| LCQ | -6.275*** | 0.007* | ||||

| (1.598) | (0.004) | |||||

| LCG | -5.840*** | 0.006 | ||||

| (1.531) | (0.004) | |||||

| LCI | -5.397*** | 0.000 | ||||

| (1.643) | (0.002) | |||||

| CR | -9.765*** | 0.141*** | -9.767*** | 0.141*** | -12.818*** | 0.262*** |

| (3.299) | (0.018) | (3.299) | (0.018) | (2.909) | (0.048) | |

| AL | 9.565 | -0.030 | 9.569 | -0.030 | 6.476 | -0.017 |

| (5.955) | (0.026) | (5.956) | (0.026) | (5.004) | (0.020) | |

| TAT | 65.143** | -0.232* | 65.171** | -0.232* | 43.898* | 0.385** |

| (28.621) | (0.122) | (28.625) | (0.122) | (26.622) | (0.180) | |

| ROA | 83.995* | -0.226 | 84.059* | -0.226 | 60.848* | -0.447** |

| (43.369) | (0.147) | (43.378) | (0.147) | (36.741) | (0.184) | |

| ROE | 1.341 | -0.007 | 1.340 | -0.007 | 2.582** | -0.008 |

| (0.945) | (0.006) | (0.946) | (0.006) | (1.079) | (0.009) | |

| TAG | -15.286* | -0.057* | -15.298* | -0.057* | -19.690*** | 0.324*** |

| (7.960) | (0.034) | (7.961) | (0.034) | (7.097) | (0.088) | |

| ROAG | -0.010*** | 0.000*** | -0.010*** | 0.000*** | -0.010*** | 0.000** |

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 2,354.184*** | 8.646*** | 2,354.560*** | 8.646*** | 2,192.537*** | 11.850*** |

| (185.072) | (0.612) | (185.111) | (0.612) | (170.333) | (1.446) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.215 | 0.286 | 0.215 | 0.286 | 0.199 | 0.063 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| TFP | DD | TFP | DD | TFP | DD | |

| TFP | 0.227*** | 0.227*** | 0.973*** | |||

| (0.053) | (0.053) | (0.119) | ||||

| LCQ | 0.001* | 0.010** | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.004) | |||||

| LCG | 0.001* | 0.008** | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.004) | |||||

| LCI | -0.001 | 0.004 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.003) | |||||

| CR | 0.005 | 0.147*** | 0.005 | 0.147*** | -0.069*** | 0.204*** |

| (0.004) | (0.018) | (0.004) | (0.018) | (0.009) | (0.042) | |

| AL | 0.000 | -0.034 | 0.000 | -0.034 | 0.004 | -0.018 |

| (0.010) | (0.026) | (0.010) | (0.026) | (0.007) | (0.019) | |

| TAT | 0.843*** | -0.069 | 0.843*** | -0.069 | 0.475*** | 0.816*** |

| (0.071) | (0.128) | (0.071) | (0.128) | (0.050) | (0.221) | |

| ROA | 0.294** | -0.196 | 0.294** | -0.196 | 0.427*** | -0.077 |

| (0.130) | (0.136) | (0.130) | (0.136) | (0.103) | (0.162) | |

| ROE | -0.007* | -0.009 | -0.007* | -0.009 | -0.009** | -0.019*** |

| (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.006) | |

| TAG | -0.021* | -0.056 | -0.021* | -0.056 | -0.217*** | 0.127** |

| (0.012) | (0.035) | (0.012) | (0.035) | (0.048) | (0.065) | |

| ROAG | 0.000 | 0.000*** | 0.000 | 0.000*** | 0.000 | 0.000** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 0.702** | 7.779*** | 0.702** | 7.777*** | -0.068 | 10.169*** |

| (0.293) | (0.564) | (0.293) | (0.565) | (0.279) | (1.325) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.260 | 0.272 | 0.260 | 0.272 | 0.178 | 0.078 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| spillovers | DD | spillovers | DD | spillovers | DD | |

| PC | 2.488* | 2.500* | 2.435** | |||

| (1.332) | (1.344) | (1.126) | ||||

| LCQ | 0.003*** | -0.000 | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.004) | |||||

| LCG | 0.003*** | -0.000 | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.004) | |||||

| LCI | 0.001*** | 0.004 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.003) | |||||

| CR | -0.000 | 0.272*** | -0.000 | 0.272*** | -0.000 | 0.272*** |

| (0.000) | (0.049) | (0.000) | (0.049) | (0.000) | (0.049) | |

| AL | 0.000* | -0.022 | 0.000* | -0.022 | 0.000* | -0.022 |

| (0.000) | (0.022) | (0.000) | (0.022) | (0.000) | (0.022) | |

| TAT | 0.001* | 0.348* | 0.001* | 0.348* | 0.000 | 0.349* |

| (0.001) | (0.180) | (0.001) | (0.180) | (0.001) | (0.180) | |

| ROA | 0.004* | -0.503*** | 0.004* | -0.503*** | 0.005** | -0.503*** |

| (0.002) | (0.187) | (0.002) | (0.187) | (0.002) | (0.187) | |

| ROE | 0.000 | -0.010 | 0.000 | -0.010 | 0.000 | -0.010 |

| (0.000) | (0.009) | (0.000) | (0.009) | (0.000) | (0.009) | |

| TAG | 0.000 | 0.339*** | 0.000 | 0.339*** | 0.000 | 0.338*** |

| (0.000) | (0.091) | (0.000) | (0.091) | (0.000) | (0.091) | |

| ROAG | -0.000 | 0.000*** | -0.000 | 0.000*** | -0.000 | 0.000*** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Cons | 0.016*** | 10.193*** | 0.016*** | 10.193*** | -0.014** | 10.195*** |

| (0.005) | (1.347) | (0.005) | (1.347) | (0.006) | (1.348) | |

| Obs | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 | 23,580 |

| 0.253 | 0.054 | 0.261 | 0.054 | 0.124 | 0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).