1. Introduction

Discrete dynamical systems play a crucial role in modeling and understanding complex phenomena across various domains, including mathematics, physics, biology, and computer science [

1,

2,

3]. These systems are characterized by their evolving states over discrete time steps, governed by deterministic rules or functions. Analyzing the long-term behavior, stability, and emergent properties of discrete dynamical systems is of paramount importance for predicting their outcomes, identifying critical transitions, and uncovering underlying mechanisms [

1,

2].

However, the forward analysis of discrete dynamical systems often encounters significant challenges due to the inherent complexity and high dimensionality of their state spaces. As the number of components or interacting entities in the system grows, the combinatorial explosion of possible configurations and trajectories can render traditional analytical and computational methods intractable [

4,

5]. Moreover, the intricate dependencies and nonlinear relationships among the system’s elements can give rise to emergent behaviors and phase transitions that are difficult to predict or explain using conventional approaches [

1,

3].

Inverse modeling, on the other hand, offers a powerful and complementary paradigm for studying discrete dynamical systems by focusing on the reconstruction of the system’s underlying rules or functions from observed data or desired outcomes [

6,

7]. By starting from the intended or measured behavior and working backwards, inverse modeling techniques aim to infer the causal mechanisms and governing equations that give rise to the system’s dynamics. This reverse engineering perspective has proven valuable in fields such as control theory, system identification, and parameter estimation [

6,

8].

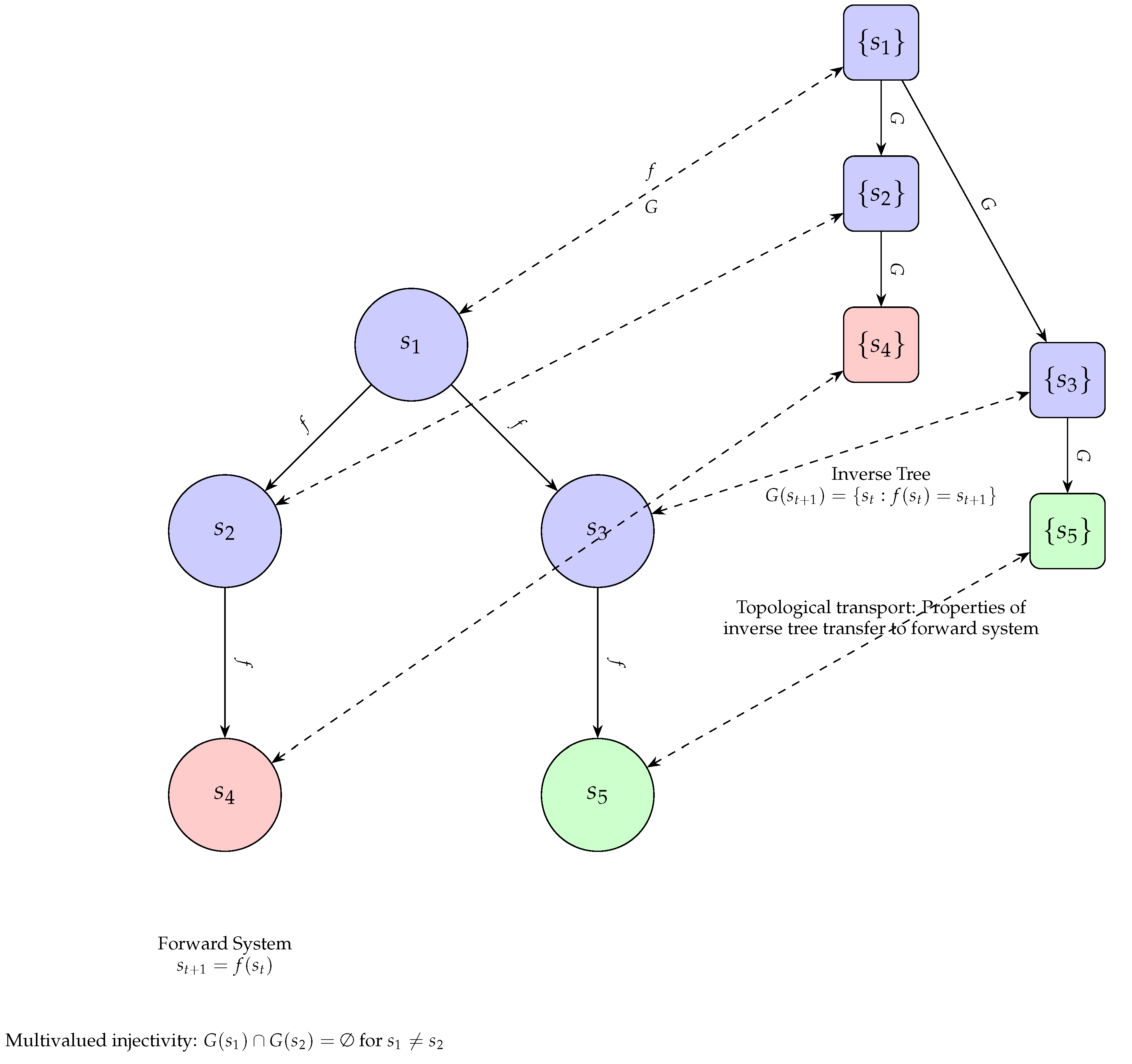

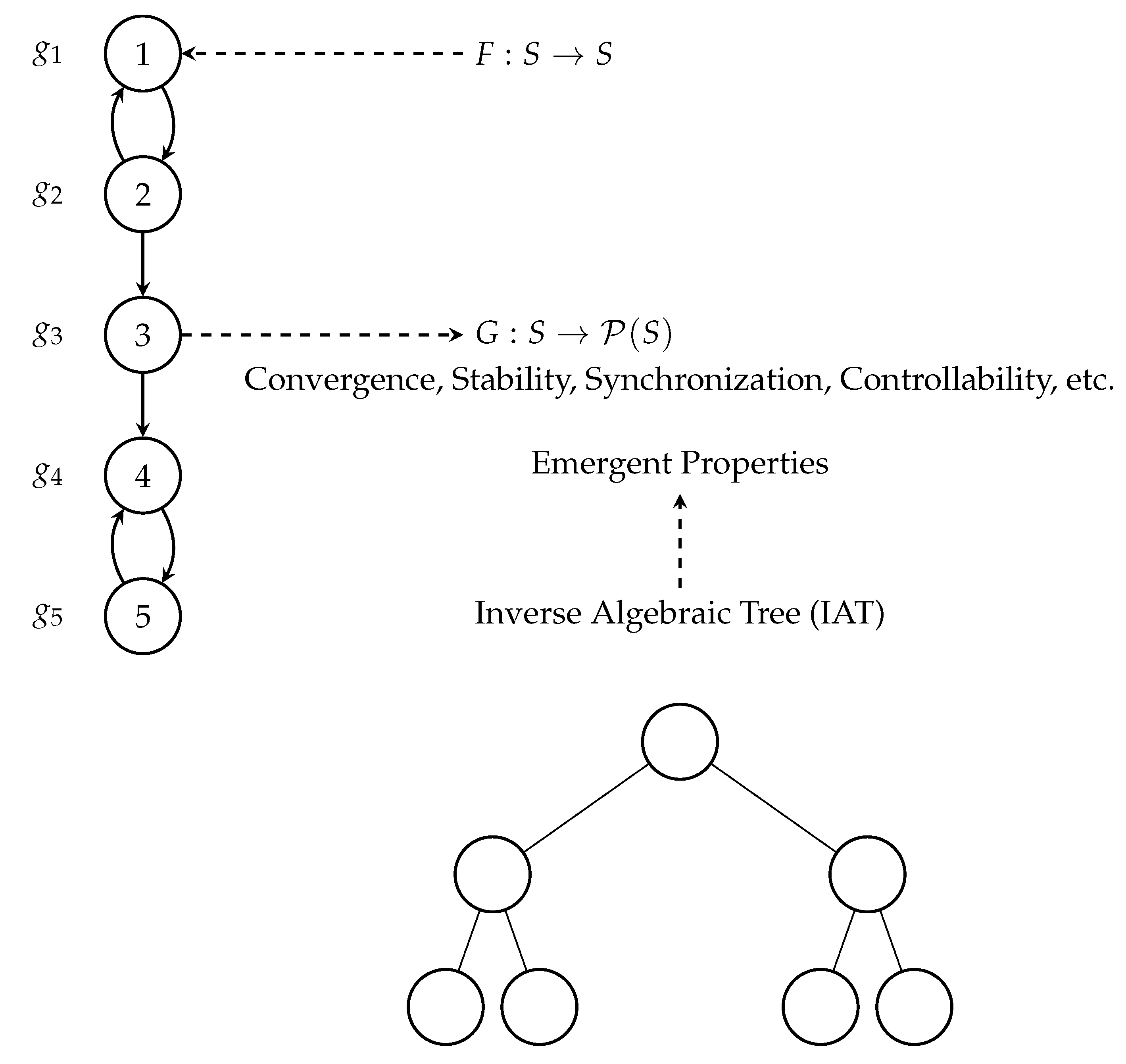

The key advantages of inverse modeling lie in its ability to tackle the complexity and high dimensionality of discrete dynamical systems by leveraging the structure and regularities present in their state spaces. By constructing an inverse algebraic model, such as an inverted tree or a graph, that encodes the relationships between states and their pre-images under the system’s evolution rule, inverse modeling techniques can efficiently navigate and explore the system’s configuration space without exhaustively enumerating all possible trajectories [

9,

10]. This compressed representation enables the discovery of global patterns, symmetries, and invariants that may be obscured in the forward analysis [

2].

Moreover, inverse modeling approaches can help overcome the limitations of traditional methods in handling systems with incomplete or noisy data, as well as those exhibiting chaotic or sensitive dependence on initial conditions [

1,

3]. By focusing on the essential features and causal relationships that give rise to the observed dynamics, inverse techniques can provide robust and interpretable models that capture the system’s core mechanisms while filtering out irrelevant details or fluctuations [

2,

6].

We acknowledge recent developments and related work in the field of inverse modeling and discrete dynamical systems:

Brin, M., & Stuck, G. (2002).

Introduction to Dynamical Systems. Cambridge University Press. [

11]

Zhao, Y., & Zhang, W. (2017). Invertible Discrete Dynamical Systems and Their Applications.

Journal of Nonlinear Science, 27(4), 1151-1184. [

12]

Golubitsky, M., & Stewart, I. (2002).

The Symmetry Perspective: From Equilibrium to Chaos in Phase Space and Physical Space. Birkhäuser Basel. [

13]

Despite the promising potential of inverse modeling in the study of discrete dynamical systems, existing methods still face significant challenges and limitations. Many inverse problems are ill-posed or underdetermined, requiring the incorporation of prior knowledge or regularization techniques to ensure unique and physically meaningful solutions [

6,

14]. The scalability and computational efficiency of inverse algorithms remain critical bottlenecks, particularly for systems with large state spaces or intricate transition rules [

4,

10]. Furthermore, the validation and interpretation of inverse models often rely on domain expertise and empirical verification, necessitating close collaboration between mathematicians, scientists, and practitioners [

14].

In this paper, we propose a novel framework for inverse modeling of discrete dynamical systems using algebraic and topological tools. By constructing inverse algebraic trees and leveraging the concept of topological transport, our approach aims to address the aforementioned challenges and provide a principled and efficient methodology for studying the global properties and emergent behaviors of complex discrete systems. The main contributions of our work are as follows:

We introduce the concept of inverse algebraic trees as a compact and structured representation of the pre-image sets and trajectories of discrete dynamical systems. These trees encode the essential information about the system’s invertibility, convergence, and stability properties.

We develop efficient algorithms for constructing and manipulating inverse algebraic trees, exploiting their recursive structure and symmetries to reduce the computational complexity and memory requirements.

We establish rigorous criteria for the existence, uniqueness, and regularity of inverse algebraic trees based on the properties of the system’s evolution rule and state space. These criteria provide guidance for the applicability and feasibility of our inverse modeling approach.

We introduce the notion of topological transport as a mechanism for transferring properties and insights obtained from the inverse algebraic trees to the original dynamical system. By establishing topological conjugacy or semi-conjugacy between the inverse and forward models, we enable the rigorous inference and prediction of the system’s long-term behavior and emergent phenomena.

We demonstrate the potential of our framework through a range of illustrative examples and case studies, spanning from classic problems in number theory and combinatorics to cutting-edge applications in systems biology and complex networks. These examples showcase the versatility and effectiveness of inverse algebraic modeling in uncovering hidden patterns, predicting critical transitions, and guiding control interventions.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we provide the necessary background and preliminaries on discrete dynamical systems, algebraic trees, and topological conjugacy.

Section 3 introduces the core concepts and constructions of our inverse modeling framework, including the definition and properties of inverse algebraic trees. In

Section 4, we present efficient algorithms for constructing and manipulating inverse algebraic trees, along with their complexity analysis and optimization techniques.

Section 5 establishes the criteria for the existence, uniqueness, and regularity of inverse algebraic trees based on the system’s properties. In

Section 6, we develop the theory of topological transport and its applications in transferring insights between inverse and forward models.

Section 7 presents a range of illustrative examples and case studies that demonstrate the power and potential of our approach. Finally, in

Section 8, we conclude with a discussion of the limitations, open problems, and future directions of our work.

Our framework aims to provide a new paradigm for the inverse modeling and analysis of discrete dynamical systems, bridging the gap between algebraic, topological, and computational techniques. By unlocking the potential of inverse algebraic trees and topological transport, we hope to enable the discovery of novel insights, the prediction of emergent phenomena, and the design of effective control strategies for a wide range of complex systems. The impact of our work extends beyond the realm of pure mathematics, offering promising applications in fields such as biology, physics, engineering, and data science.

It is important to highlight that the main objective of this work has been to establish the theoretical foundations of the Theory of Inverse Discrete Dynamical Systems (TSDDI) as a new framework for modeling and analyzing discrete dynamical systems. The focus has been on the development of formal definitions, the construction of inverse algebraic models, the demonstration of key theorems, and the exploration of illustrative applications.

While examples and case studies, such as the analysis of the SIR epidemiological model, have been presented to demonstrate the potential and utility of the TSDDI framework, the scope of this work does not encompass exhaustive validation with real-world data, extensive experiments, or large-scale simulations.

We acknowledge that rigorous empirical validation, experimental testing, and detailed simulation studies will be crucial steps in further establishing the applicability and impact of the TSDDI framework in practical contexts. However, these aspects are left as objectives for future research and subsequent work.

The current purpose is to lay a solid theoretical foundation and stimulate new research directions in the field of discrete dynamical systems. We hope that this work serves as a springboard for future explorations, interdisciplinary collaborations, and real-world applications of the Theory of Inverse Discrete Dynamical Systems.

2. State of the Art

Work of Lam and Lu (2010):

This research primarily targets the inverse control of discrete linear systems by employing a methodology that involves quantizing both inputs and outputs. The significant limitation here is its exclusive focus on linear systems. This means that the approach does not take into account the inverse modeling of more complex combinatorial structures that are non-linear in nature. Moreover, it lacks in developing topological equivalences, which are crucial for transferring properties from the direct system to the inverse system in a structured and reliable manner. Essentially, while it contributes to the field by providing a method for inverse control, it does not offer a comprehensive framework that encompasses non-linear systems or a methodological basis for property transfer between direct and inverse systems.

Ahmad’s Method (2015):

Ahmad’s research advances the application of neural networks to solve the inverse kinematics problems of manipulators, facilitating the determination of desired joint configurations. This represents a significant step forward in using modern computational techniques to address challenges in robotics. However, similar to the work of Lam and Lu, Ahmad’s method stops short of developing a complete inverse model of the system it studies. It also does not establish a formal equivalence with the direct system, which would be necessary for a thorough understanding and application of inverse dynamics in complex systems. The method excels in its specific application but lacks a generalized framework that could be applied across different types of dynamic systems.

Presented Theory’s Contributions:

The theory put forward in this document significantly extends the scope of system inversion by introducing novel concepts such as inverse analytic functions, inverse algebraic trees, and the topological transport of cardinals. These innovations allow for the construction of topologically equivalent inverse counterparts for general discrete dynamic systems. This means that the theory is not limited to linear systems or the optimization of articulated systems but can be applied to a broader range of complex systems. The introduction of topological transport of cardinals is particularly noteworthy as it provides a methodological foundation for transferring properties between direct and inverse systems in a way that preserves the topological structure, thereby ensuring that the inverse system retains the essential characteristics of the direct system.

The proposed method based on inverse algebraic models and topological transport of fundamental properties could potentially resolve historical dilemmas in discrete dynamical systems that have been beyond the reach of traditional techniques. Some specific examples include:

The Collatz Conjecture regarding the convergence of a certain iteration on natural numbers. As demonstrated in the application of the article, the proposed method can provide an alternative proof to this 80-year-old historical puzzle.

Conjectures on the termination of algorithms with intractable combinatorial explosions. Algebraic inverse modeling can analytically master this inherent complexity.

Dilemmas regarding the periodicity or attraction between cycles in chaotic systems. Topological transport of properties from the inverse model could resolve these issues.

Conjectures such as Kaprekar’s regarding recurring properties of numbers, or Ulam’s hypothesis about self-reference in cellular automata, which have challenged known methods.

Specific examples of unresolved problems:

The Collatz Conjecture regarding the convergence of a certain iteration on natural numbers.

Conjectures on the termination of algorithms with intractable combinatorial explosions.

Dilemmas regarding the periodicity or attraction between cycles in chaotic systems.

2.1. Comparison with Other Techniques

Unlike the Lyapunov method and phase diagrams, the proposed theory of inverse discrete dynamical systems allows for the construction of a topologically equivalent inverse model to the original system. This enables a more comprehensive analysis of the system’s behavior by being able to analytically study said inverse model.

Similarly, the topological transport of properties between the canonical model and its inverted counterpart facilitates a more detailed characterization of the cardinal attributes of the system, overcoming the limitations of traditional techniques such as Lyapunov and phase diagrams.

For example, while the Lyapunov method is restricted to autonomous systems and does not provide an explicit construction of Lyapunov functions, the proposed approach is applicable to systems with external inputs and explicitly constructs inverse models for their study.

Likewise, compared to the loss of information in the projections of phase diagrams or their interpretational difficulty in multidimensional systems, the introduced methodology completely preserves topological properties by constructing inverse algebraic trees.

Thus, the developed theory allows addressing historical challenges in discrete dynamical systems beyond the scope of traditional techniques. Its viability will depend on the construction of such inverse models for each system under study.

In summary, the proposal overcomes previous limitations by providing an integrative framework for the inversion of general discrete dynamical systems, introducing advanced tools for modeling, analysis, and topological transfer of cardinal properties.

2.2. Related Advancements

Some recent advancements in pure mathematics related to discrete dynamical systems and number theory that share similarities with the innovative approach introduced in this work include:

Terence Tao et al.’s progress on almost all orbits of the Collatz map achieving almost bounded values. While not resolving the Collatz Conjecture, they provide analytical bounds on orbit growth that could complement the inverse approach.

Gutowski’s work on the convergence of Collatz trajectories forming a nowhere dense set. It establishes topological properties of orbits that could be topologically transported in the inverse model.

Advances in applying Ergodic Theory tools to tackle the Collatz Conjecture and discrete systems, such as Lagarias’ work. Topological transport from inverse models could expand this understanding.

The automated theorem proving (ATP) program has succeeded in automatically proving certain conjectures in number theory, like the Erdős–Straus conjecture. Potential exists to integrate ATP in computational validations of inverse models.

Work on self-similarity hypotheses in cellular automata, equivalent to Conway’s Conjecture, which remains a core unsolved problem in algorithmic complexity, theoretical computer science, and discrete mathematics.

3. Domain of Applicability

It is proposed that the theory presented be applicable to the following categories of discrete dynamical systems:

Recursive dynamical systems over discrete spaces.

Systems exhibiting moderate combinatorial explosions, where the construction of the algebraic inverse model is feasible.

Chaotic systems with global asymptotic convergence of trajectories.

The introduced methodology of algebraic inverse modeling and analysis is posited as a valid and fruitful approach for the types of discrete dynamical systems previously characterized.

3.1. Categorization of Applicable Systems

Let be a discrete dynamical system with an analytical inverse function G. The following categories of systems where the methodology of inverse algebraic modeling and analysis is viable are proposed:

Recursive dynamical systems over discrete spaces: systems defined by a recurrence rule over a discrete space.

Discrete algorithms and computational processes: the methodology allows for analyzing algorithmic properties such as termination, optimality, complexity, etc.

Systems with moderate combinatorial explosions: the construction of the inverse model is feasible as long as the combinatorial explosion is reducible and computable.

Chaotic systems with globally regular behaviors: despite local chaos, the methodology models global convergences.

Additionally, the following categories that hinder the application of the approach are proposed:

Systems with state spaces of continuous cardinality: an extension of the theory would be required.

Systems defined by irreversible or non-recursive evolution rules: defining an analytical inverse function is difficult.

Systems with high sensitivity to initial conditions or severe chaotic phenomena: the construction of a global inverse model could be unattainable.

Let be a discrete dynamical system, where X is the discrete state space and is the evolution rule.

Definition 3.1. The system is said to be directly modelable if it satisfies the following properties:

F is recursive over X. The combinatorial explosiveness of F is limited. There exists an analytical inverse function that recursively undoes the steps of F. G satisfies injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness over X.

Under these conditions, the construction of the inverse algebraic model is guaranteed, as well as the topological transport of properties.

On the other hand, the system is said to be non-directly modelable if any of the above properties is not satisfied. In that case, adaptations such as:

Techniques of topological encapsulation

Topological discretization preserving cardinal properties

Construction of partial models

Hybridization with other approaches

are required to apply the proposed methodology.

3.2. Examples and Applications of the Methodology

Alternative Proof of the Collatz Conjecture

The Collatz Conjecture is a well-known open problem in mathematics that concerns the behavior of a simple iterative process on the positive integers. The conjecture states that for any positive integer n, the sequence obtained by repeatedly applying the following rule will eventually reach the number 1:

If n is even, divide it by 2.

If n is odd, multiply it by 3 and add 1.

The proposed methodology provides an alternative proof of the Collatz Conjecture by constructing an inverse algebraic model of the system and analyzing its structural properties. The proof involves demonstrating that the inverse algebraic model is topologically equivalent to the original system and that the topological properties of the model, such as the absence of anomalous cycles and the universal convergence of trajectories, are preserved through topological transport.

Analysis of the Game of Life

The Game of Life is a cellular automaton that was invented by the mathematician John Conway in 1970. It is a simple rule-based system that simulates the evolution of a population of cells on a grid. The proposed methodology can be applied to analyze the behavior of the Game of Life by constructing an inverse algebraic model of the system and analyzing its structural properties. For example, the methodology can be used to demonstrate that certain initial configurations of the Game of Life will eventually stabilize or exhibit periodic behavior, or that certain patterns will propagate indefinitely.

Analysis of Discrete Algorithms

The proposed methodology can be applied to analyze the behavior of discrete algorithms by constructing an inverse algebraic model of the algorithm and analyzing its structural properties. For example, the methodology can be used to demonstrate that certain algorithms will eventually terminate, or that they will exhibit certain performance characteristics, such as polynomial time complexity or logarithmic space complexity. The methodology can also be used to analyze the behavior of algorithms in the presence of errors or perturbations, by constructing an inverse algebraic model of the perturbed system and analyzing its structural properties.

Analysis of Discrete Dynamical Systems in Biology

The proposed methodology can be applied to analyze the behavior of discrete dynamical systems in biology, such as gene regulatory networks, neural networks, and population dynamics. For example, the methodology can be used to demonstrate that certain gene regulatory networks will eventually reach a steady state, or that certain neural networks will exhibit certain patterns of activity, such as oscillatory behavior or chaotic behavior. The methodology can also be used to analyze the behavior of population dynamics in the presence of perturbations, such as environmental changes or predator-prey interactions, by constructing an inverse algebraic model of the perturbed system and analyzing its structural properties.

4. Definitions and Preliminary Concepts

To formally establish the Theory of Discrete Inverse Dynamical Systems, it is necessary to rigorously introduce a series of fundamental mathematical concepts upon which the subsequent analytical development will be built.

Firstly, the basic notions of discrete spaces must be adequately defined, through sets equipped with the standard discrete topology (see [

15], Chapter 2). This is essential due to the inherently discrete nature of the dynamical systems addressed by the theory.

Definition 4.1.

: Let X be a non-empty set. A function is called a metric on X if it satisfies:

, (Non-negativity)

if and only if , (Discernibility)

, (Symmetry)

, (Triangle Inequality)

Then, the ordered pair is called a metric space

.

Definition 4.2.

Discrete System : Let be a metric space. We say that is a discrete system if:

X is countable (finite or countably infinite)

-

d is a discrete metric, i.e., the triangle inequality holds with equality:

Definition 4.3.

Continuous System : Let be a metric space. We say that is a continuous system

if:

X is uncountable (uncountably infinite)

d is a continuous metric, i.e., the triangle inequality is strict: such that

Definition 4.4.(Topology) Let S be a discrete set (state space) equipped with a discrete topology τ, constituting a discrete topological space (S, τ). Formally:

: (S, τ) is a discrete topological space.

Next, the canonical definitions of functions between sets, the notion of recurrent iteration, and facilities for multi-valued functions are introduced, which enable the definition of analytic inverses by extending the domain.

Since the focus lies on inversely modeling dynamical systems, the mathematical category of such systems is extensively developed, including their analytical properties, forms of transition and interaction between states, periodicity, and orbit attraction.

Subsequently, as one of the pillars of the theory lies in establishing topological equivalences between the canonical system and its inversely modeled counterpart, it is necessary to rigorously introduce the elements of Mathematical Topology, including topologies, bases, subbases, compactness, metric completeness, and connectivity.

Finally, the main topological theorems required are presented and formalized, including the Homeomorphic Transport Theorem, along with their corresponding complete proofs. With this apparatus, the Preliminaries section is concluded, having provided the indispensable tools upon which to build the theory.

Definition 4.5 (Topology). Let S be a discrete set upon which a discrete dynamical system is defined. A topology τ on S consists of a family of subsets of S, called open sets, which satisfy:

Every union of open sets is open. Every finite intersection of open sets is open. Then the ordered pair constitutes a discrete topological space.

Definition 4.6 (Topological Compatibility). Let be a discrete topological space and . We say that τ satisfies the compatibility property if:

That is, the intersection of two open sets is open.

Definition 4.7 (Compactness). Let be a discrete topological space. We say that S is compact if:

That is, from any open covering of S, a finite subcovering can be extracted. Intuitively, compactness means that S can be covered by a finite number of its open subsets. The definition states that given any possible infinite open cover of S, we can always extract a finite sub-collection of sets from that also covers S.

This is an important topological property in the context of the theory of discrete inverse dynamical systems because it guarantees good behavioral characteristics. Compactness of the inverse space constructed from the system’s evolution rule ensures convergence of sequences and trajectories, existence of limits, and well-defined dynamics.

Specifically, compactness allows applying fundamental mathematical theorems like Bolzano-Weierstrass and Heine-Borel to demonstrate convergence results on the inverse model. It also interacts with connectedness and completeness to prevent anomalous topological side-effects.

Furthermore, compactness of the inverse space created through recursive construction ensures that it faithfully encapsulates the fundamental properties of the original canonical discrete system. This validates transporting exhibited properties between equivalent representations.

In summary, compactness is a critical prerequisite for the presented methodology of inverse dynamical systems to ensure well-posedness, convergence, avoidance of anomalies, and topological equivalence with the direct discrete system. Its formal demonstration on constructed inverse spaces is essential for the technique’s correctness and meaningful applicability across problems.

Definition 4.8 (Connectedness). Let be a discrete topological space. We say that S is connected if:

closed]

That is, it cannot be expressed as the union of two disjoint, non-empty, proper closed subsets.

Definition 4.9 (Topological Equivalence). Let and be discrete topological spaces. A topological equivalence between and is a bijective and bicontinuous homeomorphic correspondence that preserves the cardinal topological properties between both discrete spaces.

Definition 4.10 (State Space). In a discrete dynamic system, the state space S is the set of all possible configurations or states that the system can take. Each element represents a unique state of the system at a given moment. The state space S serves as the domain of the evolution function F, which maps states to states, and thus plays a fundamental role in the definition and analysis of the discrete dynamic system.

Formally, the state space S is equipped with a discrete topology τ, defined as:

This means that each individual state is both an open set and a closed set in the topology τ. The pair forms a discrete topological space, enabling the analysis of topological properties and the definition of concepts such as continuity and homeomorphism in the context of discrete dynamic systems.

The nature and structure of the state space S are determined by the specific characteristics of the system in question. For example:

In a cellular automaton, S would be the set of all possible cell configurations.

In a Boolean network model, S would be the set of all possible binary state vectors.

In a dynamic system defined over integers, S would be a subset of .

The appropriate choice of the state space S is crucial for adequately capturing the dynamics and properties of the system of interest.

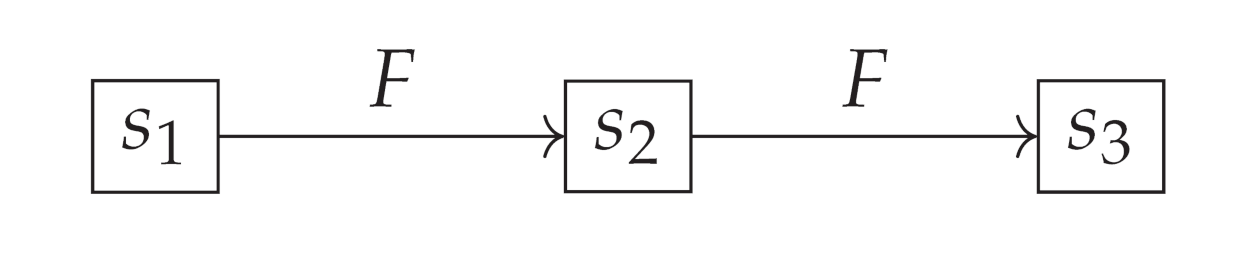

Definition 4.11 (Discrete Dynamical System). A discrete dynamical system is an ordered pair such that:

Where denotes the n-th iterate of F applied to the state .

Examples of discrete dynamical systems include:

Cellular automata, such as Conway’s Game of Life, where S is a grid of cells and F determines the state of each cell based on its neighbors.

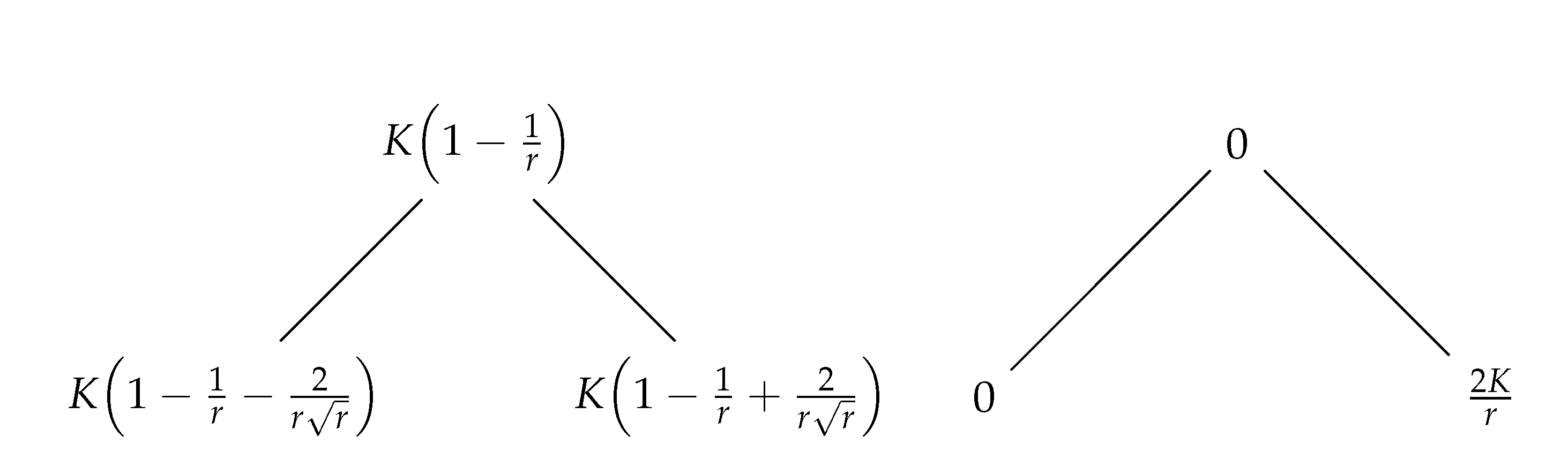

Iterative maps, like the Logistic Map, where S is a subset of real numbers and for some parameter r.

Example of a simple SIR model:

Definition 4.12 (Orbit in DIDS). Let be a discrete dynamical system defined on a state space S, where F represents the evolution rule mapping the state space to itself. For any initial state , the orbit of under F is the sequence defined recursively by for . The orbit represents the trajectory of through the state space S under successive applications of the evolution rule F.

Definition 4.13. Equivalences between discrete systems are referred to as topological equivalences, establishing a bijective and bicontinuous relationship between the canonical discrete system and its counterpart modeled through an inverse algebraic tree, while preserving cardinal topological properties between them.

Let be a discrete topological space. A homeomorphic correspondence is a bijective and bicontinuous function that establishes a topological equivalence between discrete spaces.

Definition 4.14. Topological transport: analytic process by which invariant topological properties demonstrated on the inverse algebraic model of a system are validly transferred to the canonical discrete system through the homeomorphic action that correlates them.

Definition 4.15.

Let S be a set. A discrete topology τ on S is defined as:

where and each element defines both an open and closed set (a singleton).

Furthermore, it satisfies:

Then constitutes a discrete topological space.

Definition 4.16 (Discrete Space). Let S be a set equipped with a discrete topology τ. Then the ordered pair constitutes a discrete space.

Definition 4.17 (Discrete Function). Let be a function between discrete spaces. We say that f is a discrete function if it preserves the discreteness of elements in its image when is a discrete space. That is, for all such that , it holds that .

Definition 4.18 (Categories of DDS). Let be a discrete topological space and an evolution rule in . We define the following categories of discrete dynamical systems (DDS):

-

According to the cardinality of :

- -

Finite:

- -

Countable:

- -

Continuous:

-

According to the recursiveness of :

- -

Recursive:

- -

Non-recursive: Does not satisfy the above

-

According to sensitivity to initial conditions:

- -

Non-sensitive:

- -

Sensitive: Does not satisfy the above

-

According to the degree of combinatorial explosiveness:

- -

Limited:

- -

Unbounded:

where is a polynomial.

Theorem 4.1 (Conditions for Topo-Invariant Transport). Let be a DDS and a topo-invariant property. If:

is recursive over

The combinatorial explosiveness of is limited

P is demonstrated in the inverse algebraic model of

Then is invariably preserved in by topological transport.

Theorem 4.2.

Let be a discrete dynamical system. Then, given an initial condition and a sequence obtained by iterating the evolution rule F starting from x, it holds that:

In other words, starting from any initial state x, F always generates a unique trajectory under iteration.

Definition 4.19 (Power Set).

Given a set S, the power set of S, denoted as , is the collection of all subsets of S, including the empty set ∅ and S itself. Formally:

This definition establishes the power set as the family of all possible subsets of S. In other words, each element of is itself a subset of S. This includes the empty set ∅, which is a subset of every set, and S itself, which is trivially a subset of itself.

Some key points about the power set:

If S is a finite set with elements, then will contain elements. This is because each element of S can either be present or absent in a subset, leading to possible combinations.

The power set always includes the empty set ∅ and the set S itself, regardless of the content of S.

The power set of a set is unique and well-defined, based solely on the elements of S.

Definition 4.20.

Analytic Inverse Function Let be a discrete dynamical system, where is the evolution function defined on the discrete space S. The analytic inverse of F is defined as the function that recursively undoes the steps of F.

Formally, G satisfies:

Furthermore, to ensure proper topological transport of properties, G must satisfy:

Injectivity:

Surjectivity:

Exhaustiveness: Recursion through G reaches all states in S.

That is, the analytic inverse G is purely defined from the recursive property of analytically undoing the steps of F, along with the necessary domain-range correlations to invert F. The properties of injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness are required to ensure proper topological transport from the inverse model.

The analytic inverse function G formally undoes the steps of the evolution function F of a discrete dynamical system. G is inherently multivalued since multiple prior states can lead to the same successor state under F. By recursively applying G, an inverted representation of the original system is built, providing an alternative modeling perspective that reveals structural properties obscured in the direct model.

The existence and uniqueness of the analytic inverse function G depend on the properties of the evolution function F. If F is bijective, then G is guaranteed to exist and be unique.

Property 1 (Recursive Inverse Function). Let be a discrete dynamical system, where is the evolution function. Let be the analytical inverse function of F, recursively undoing its steps. Then:

Proof. Let

be an arbitrary state. By definition of G as the analytic inverse function, we have:

Applying F on both sides:

Therefore, G recursively undoes the steps of F. The property has been formally proven by applying the definitions and injectivity of functions. □

4.1. Combinatorial Complexity and Inverse Model Constructibility

Definition 4.21 (Moderate Combinatorial Explosion). Let be a discrete dynamical system with evolution function defined over the discrete state space S. Let be the analytic inverse function of F that recursively undoes its steps, generating the inverse algebraic tree .

We say that exhibits a moderate combinatorial explosionif the following conditions are met:

Growth rate bound: There exists a function such that for any initial state , the number of reachable states after n recursive applications of G is bounded by , i.e., for all , and f is asymptotically smaller than an exponential function, i.e., for all .

-

Conditions on algebraic or topological structure: The state space S has an algebraic or topological structure (e.g., a group, ring, or metric space) that satisfies certain conditions guaranteeing computational tractability. These conditions could include:

- (a)

The composition operation in S is computable in polynomial time.

- (b)

S has a finite or efficiently computable representation.

- (c)

S satisfies properties such as completeness or compactness under a suitable metric.

-

Complexity of construction algorithms: The algorithms used to construct the inverse algebraic tree T from G have manageable time and space complexity. Formally:

- (a)

The time required to compute for any state is polynomial in the size of the representation of s.

- (b)

The depth of the tree T (i.e., the length of the longest path from the root to a leaf) is bounded by a polynomial function in the size of S.

- (c)

The maximum degree of any node in T (i.e., the maximum number of children of a node) is bounded by a constant.

If these conditions are satisfied, we say that exhibits a moderate combinatorial explosion, implying that the construction and analysis of the inverse algebraic model are computationally tractable.

5. Axiomatic Foundations of DIDS

The axiomatic foundations of the theory of Discrete Inverse Dynamical Systems (DIDS) can be divided into two categories: axioms that ensure the existence and constructibility of the inverse model, and axioms that ensure the transfer of properties between the inverse model and the canonical model.

Axiom 1 (Existence of the Inverse Function). For every discrete dynamical system , there exists an analytic inverse function that undoes the steps of F.

This axiom establishes the basis for constructing the inverse model, ensuring that we can always find a function G that "reverses" the dynamics of F.

Axiom 2 (Constructibility of the Inverse Tree). For every discrete dynamical system with inverse function G, an inverse algebraic tree T can be constructed by applying G recursively.

This second axiom tells us that the function G not only exists but can also be used to effectively construct the inverse tree T. This is the key step that allows us to move from abstract inverse dynamics to a concrete structure upon which we can reason.

Now, to ensure the transfer of properties, we need additional axioms about G:

Axiom 3 (Injectivity of G). The inverse function G is injective, i.e., for all , if , then .

Axiom 4 (Surjectivity of G). The inverse function G is surjective, i.e., for all , there exists a such that .

These axioms ensure that G establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the states of the original system and the nodes of the inverse tree. This correspondence is crucial for property transfer: it ensures that the properties of the inverse tree are faithfully reflected in the original system.

Finally, these conditions on G - existence, injectivity, surjectivity - can be seen as the defining requirements of a DIDS:

Definition 5.1. A discrete dynamical system is a DIDS if and only if there exists an inverse function G satisfying the axioms of existence, injectivity, and surjectivity.

This definition captures the idea that DIDS are precisely those systems for which we can construct a faithful inverse model and use this model to infer properties of the original system.

This axiomatic formulation provides a solid and elegant foundation for the theory of DIDS, clearly highlighting the roles of the different axioms and how they combine to allow the inverse analysis of discrete dynamical systems.

6. Inverse Modeling of Systems

Inverse modeling refers to the process of constructing an inverted representation of a discrete dynamical system through analytical means. Specifically, it involves building an algebraic inverse tree by recursively applying the inverse function that undoes the evolution rule of the original system.

Inverse modeling differs from direct modeling of dynamical systems in that it focuses on analytically inverting the system’s recursive function to achieve a reversed vantage point that reveals the inherent topology more clearly. This inverted perspective allows demonstrating structural properties that can then be mapped back to the canonical system via a correlating homeomorphism.

Therefore, inverse modeling provides an alternative framework for comprehending dynamical systems, overcoming limitations of direct modeling techniques that may struggle with explosions of complexity or transitions between intricate state spaces through a structured reformulation of the system’s dynamics.

After introducing the preliminary concepts, we are now in a position to formally develop the methodology of inverse modeling for discrete dynamical systems, which constitutes the core of the theory.

Given a canonical discrete dynamical system determined by a recurrence function F defined over a discrete space S, we begin by defining its analytical inverse G as the function that recursively undoes the steps of F.

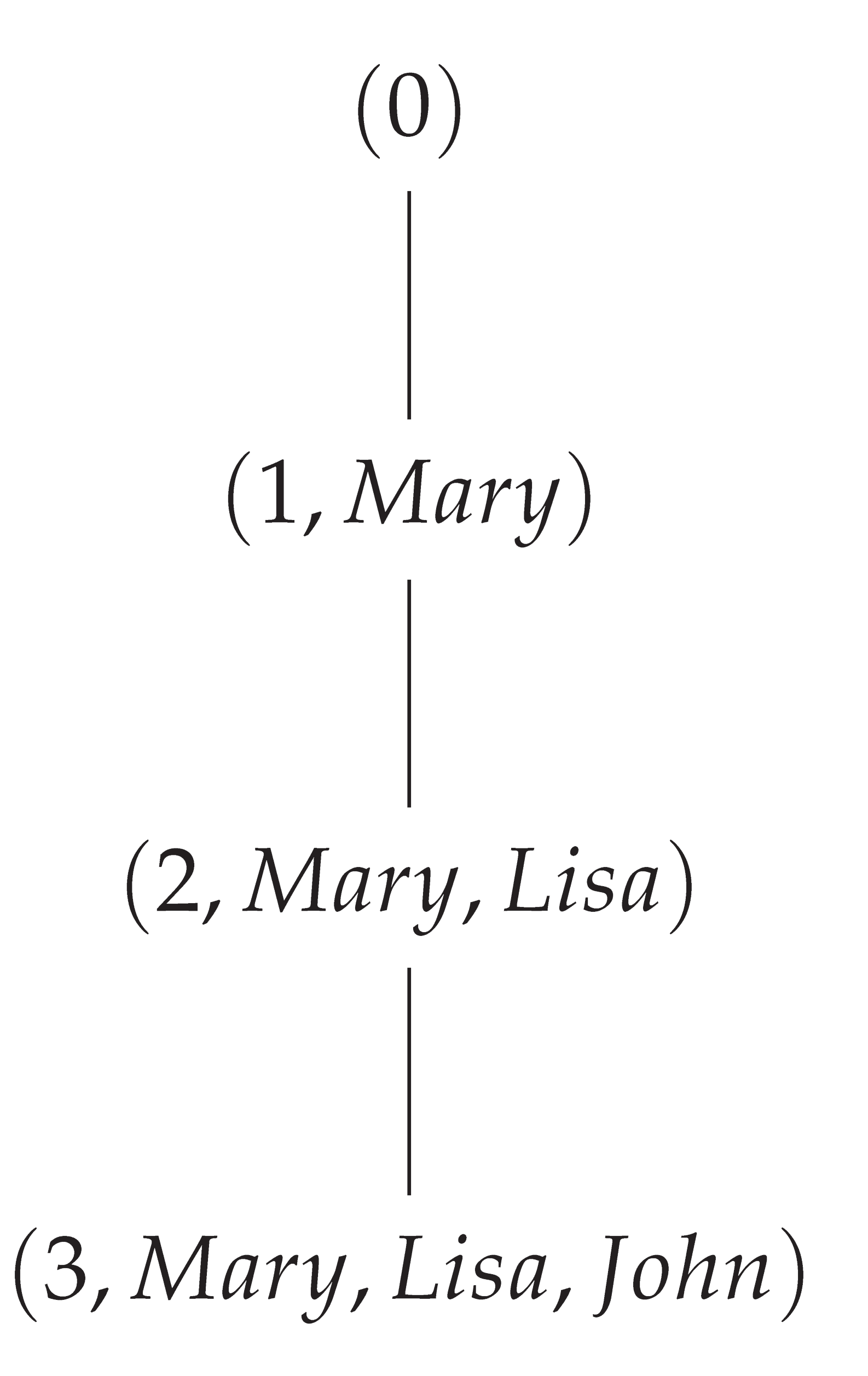

Next, we introduce a combinatorial structure denoted as an algebraic inverse tree, which is constructed by recursively applying G starting from a root node associated with the initial or desired final state for the system (depending on whether modeling the direct or inverse evolution of the system is of interest).

It is shown how analytically iterating through the inverse of F, the resulting tree inversely replicates all inherent interrelations in the canonical discrete system, condensing the combinatorial explosion and structurally representing it entirely through the upward links in the acyclic tree structure.

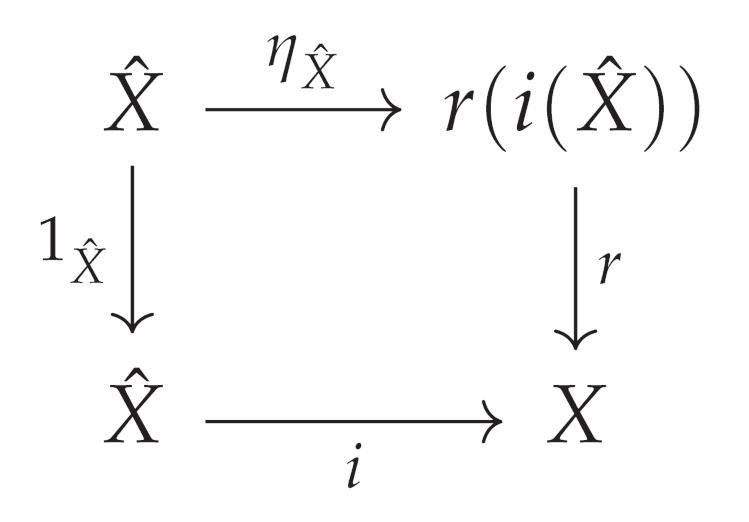

Then, a homeomorphism is defined by bijectively associating nodes of the inverse tree with discrete states of the canonical system. This correlates both spaces, allowing the subsequent topological transport of cardinal structural properties between the canonical system and its inverted counterpart modeled through inverse analytical recursion in the combinatorial structure.

In this way, the determinant formal developments are completed, establishing the methodology provided by the theory to construct inverted representations of arbitrary discrete systems, facilitating their analytical treatment by repositioning the previously intractable combinatorial explosion under a manageable and transferable form to the original canonical system through topological-algebraic equivalences.

Definition 6.1 (Discrete Topological Space). Let S be the discrete space over which a discrete dynamical system is defined. The discrete topology on S is defined as:

where and each element of S defines an open and closed set (a singleton).

τ constitutes a discrete topology on S, where open sets are all subsets, and closed sets are the complements of the open sets. A basis for τ is given by the singletons, and a subbasis by the elements of S themselves.

Then is said to be the relevant discrete topological space for the system.

Definition 6.2 (Discrete Function). Let be a function between discrete spaces. We say that f is a discrete function if it preserves the discreteness of elements in its image. That is, such that , it holds that .

Definition 6.3 (Discrete Dynamical System). Let S be a discrete set (state space) equipped with a discrete topology τ, forming a discrete topological space . Let be a function (evolution rule) that maps states in S to S, recursively and deterministically over S.

Formally, a Discrete Dynamical System (DDS) is an ordered pair such that:

S is a discrete set with discrete topology τ, making a discrete topological space.

is a discrete function, preserving the discreteness of elements in S.

F is deterministic over S:

F is recursive: successive iteration .

F preserves the topology τ of S: is open , with open sets.

Where denotes the n-th iteration of F applied to the state .

Definition 6.4 (Analytic Inverse Function). Let be a discrete dynamical system, with the evolution function defined over the discrete space S. The analytic inverse function of F is defined as the function that recursively undoes the steps of F. Formally, G satisfies:

G analytically undoes F:

Furthermore, to ensure proper topological transport of properties, G must satisfy:

Injectivity:

Surjectivity:

Exhaustiveness: Recursion through G reaches all states in S.

That is, G is purely defined from the recursive property of analytically undoing the steps of F, along with the necessary domain-range correlations to invert F.

Conditions on the Analytic Inverse Function G for Topological Transportability

Let be a discrete dynamical system, and let be its inverse algebraic tree generated by the inverse analytic function .

-

Relative Compactness: For T to be relatively compact, G must satisfy:

- (a)

Multivalued injectivity: For any pair of distinct states , and are disjoint sets.

- (b)

Bounded growth: There exists a function such that for any initial state s and any n, the number of reachable states after n recursive applications of G is bounded by , and is asymptotically smaller than an exponential function.

Copy code

Explain

-

Relative Metric Completeness:

For the metric space associated with T to be relatively complete, G must satisfy:

- (a)

Exhaustiveness: For any state , there exists a finite number of recursive applications of G that lead to a root state r.

- (b)

Preservation of Cauchy sequences: If is a Cauchy sequence in S, then is also a Cauchy sequence.

-

Connectivity:

To ensure the connectivity of T, G must satisfy:

- (a)

Reachability: For any pair of states , there exists a finite sequence of states such that , , and is in for all i.

-

Topological Equivalence:

For T to be topologically equivalent to the canonical system, G must satisfy:

- (a)

Invertibility: For any state , s is contained in , where F is the evolution function of the canonical system.

- (b)

Continuity: G is continuous with respect to the topologies of S and .

Definition 6.5 (Discrete Homeomorphism). Given discrete spaces , a discrete homeomorphism is a bijective and bicontinuous function . That is, f and are continuous and discrete.

Note 1. Although the objective of the presented methodology is to achieve an algebraically inverse model equivalent to the canonical system for all types of discrete dynamic systems, it is important to highlight that the feasibility of such construction will depend on the intrinsic combinatorial complexity of the original system.

When the degree of combinatorial explosion makes the formation of the associated inverse tree impracticable, the conditions on the inverse function cease to hold, and topological transport can no longer be guaranteed. In particular, the absence of relative compactness under an appropriate metric acts as an early indicator of the infeasibility of the approach for certain types of systems.

Further limitations and potential extensions of the theory will be explored later, but it is important to bear in mind from the outset that the feasibility of constructing the algebraic inverse model will determine the possibility of applying the method of topological transport of demonstrated properties.

Example 1 (Discrete Homeomorphism between Numeric Representations). Consider the set of natural numbers as a discrete space. We define two functions:

, which assigns to each natural number its binary representation.

, which assigns to each natural number its decimal representation.

Here, and denote the sets of all finite strings of binary and decimal digits, respectively.

Both functions are bijective and continuous in the discrete sense, since each natural number has a unique binary and decimal representation, and the discrete topology of is preserved under these transformations.

Now, we define the composition , which assigns to each decimal representation its corresponding binary representation. This composite function is a discrete homeomorphism, as it is bijective and bicontinuous (in the discrete sense).

For example:

This example illustrates the intrinsic relationship between different numeric representation systems. Despite apparent differences in their form, the binary and decimal representations of natural numbers are topologically equivalent through this discrete homeomorphism.

6.1. Algebraic Inverse Tree Construction

Definition 6.6 (Topological Equivalence). Let be the topological space associated with the canonical discrete dynamical system, and be the topological space associated with the inverse model, where ρ is the natural topology on T. We say that and are topologically equivalent if there exists a function such that:

f is bijective, i.e., for each there exists a unique such that .

Both f and its inverse are continuous with respect to the topologies ρ and τ. That is, for each open set , its preimage is open in ρ; and for each open set , its image is open in τ.

The construction of the algebraic inverse tree is done by recursively applying the analytical inverse function , which undoes the steps of the evolution rule F of the canonical discrete dynamical system . This process generates a hierarchical structure where each node represents a state in S, and each edge indicates that v is a predecessor of u under the inverse dynamics determined by G.

Given this construction, we can naturally define a function

that associates each node

with its corresponding state

. Formally:

Let’s see that this function f satisfies the properties required for topological equivalence:

f is bijective: By construction, each node represents a unique state , and each state is represented by at least one node (due to the exhaustiveness of G). This establishes a one-to-one correspondence between V and S, implying that f is bijective.

-

f and are continuous: To show the continuity of f and , we must verify that the inverse images of open sets are open in the respective topologies.

Continuity of f: Let be an open set in . We need to prove that is open in . By definition of the discrete topology , each state is an open set. Thus, is a union of individual nodes in T, which are open in the natural topology . Therefore, is open in .

Continuity of : Let be an open set in . We need to prove that is open in . Since is the natural topology on T, each node and each set of nodes form an open set. Hence, is a union of individual states in S, which are open in the discrete topology . Therefore, is open in .

Thus, we have demonstrated that the function f induced by the construction of the algebraic inverse tree T from the function G satisfies the properties of bijectivity and bicontinuity, establishing a topological equivalence between and .

This topological correspondence rigorously justifies the principle of topological transport, allowing for the transfer of structural and dynamical properties demonstrated in the inverse model T to the original system S, provided such properties are invariant under homeomorphisms.

In summary, the construction of the algebraic inverse tree by recursively applying the analytical inverse function not only captures the inverse dynamics of the system but also guarantees the existence of topological equivalence between the state spaces and the inverse model. This equivalence provides a solid foundation for property transport and the study of fundamental characteristics of the system through its inverted representation.

6.2. Combinatorial Complexity and Inverse Model Constructibility

The construction of the inverse algebraic model from a given discrete dynamical system can be a computationally challenging task, particularly when the system exhibits a high degree of combinatorial complexity. The number of possible states and transitions in the system can grow exponentially with the number of variables or components, leading to a combinatorial explosion that can hinder the efficient construction of the inverse model [

4,

16].

To analyze the computational complexity of constructing the inverse algebraic model, we introduce the concept of the combinatorial growth function , which measures the number of states generated by the inverse function G after n iterations, starting from an initial state . Formally, , where denotes the n-fold composition of G with itself.

The growth rate of

provides insight into the feasibility of constructing the inverse model for a given discrete dynamical system. If

exhibits polynomial growth, i.e.,

for some constant

k, then the inverse model construction is considered tractable. However, if

grows exponentially or faster, i.e.,

for some constant

, then the construction process becomes computationally intractable [

4].

The study of combinatorial complexity and its impact on the constructibility of inverse models is rooted in the field of computational complexity theory, which aims to classify computational problems according to their inherent difficulty [

4]. Problems that can be solved in polynomial time are considered tractable, while those that require exponential time are considered intractable. The construction of inverse models for discrete dynamical systems can be seen as a computational problem, and its complexity can be analyzed using tools and techniques from complexity theory [

16].

To mitigate the challenges posed by combinatorial complexity, various strategies can be employed. One approach is to exploit the structure and symmetries present in the discrete dynamical system to reduce the effective size of the state space and simplify the construction of the inverse model. Another approach is to use approximation techniques, such as sampling or heuristic search, to explore the state space efficiently and construct an approximate inverse model that captures the essential features of the system [

16].

Despite the challenges posed by combinatorial complexity, the inverse modeling approach remains a powerful tool for analyzing and understanding discrete dynamical systems. By carefully considering the growth rate of the combinatorial complexity and employing appropriate strategies to mitigate its impact, it is possible to construct informative and insightful inverse models that provide valuable insights into the behavior and properties of the underlying system.

The discussion of combinatorial complexity and its impact on the constructibility of inverse models highlights the importance of considering the computational aspects of the inverse modeling process. By grounding the analysis in the principles of computational complexity theory and algorithm design, we can develop a deeper understanding of the feasibility and limitations of inverse modeling techniques, and devise effective strategies for overcoming the challenges posed by combinatorial explosion.

6.2.1. Topological Conditions for Dealing with Severe Combinatorial Explosions

Theorem 6.1 (Topological Conditions for Dealing with Severe Combinatorial Explosions). Let be a discrete dynamical system with evolution function defined over the discrete space S. Let be the analytic inverse function of F that recursively undoes its steps, generating the inverse algebraic tree .

The system can be effectively modeled despite exhibiting a severe combinatorial explosion if and only if the following conditions hold:

1. Relative Compactness: For every , the subtree of depth n is relatively compact under the metric d.

2. Asymptotic Connectivity: For every pair of nodes , there exists a directed path from u to v or from v to u in T.

3. Relative Metric Completeness: Every Cauchy sequence in converges to a node in T.

Proof. First, we will prove that the conditions are necessary:

(Necessity of Relative Compactness) Suppose the system can be effectively modeled despite exhibiting a severe combinatorial explosion. Then, for each , the subtree of depth n must be finite. Otherwise, it would not be possible to effectively construct the inverse model.

Furthermore, for each , is bounded in since the maximum distance between any pair of nodes in is limited by . Therefore, is a finite and bounded subset of , implying that it is relatively compact.

(Necessity of Asymptotic Connectivity) Suppose there exists a pair of nodes such that there is no directed path from u to v or from v to u in T. Then, u and v belong to disconnected components of T, contradicting the assumption that the inverse model can be effectively constructed.

(Necessity of Relative Metric Completeness) Let be a Cauchy sequence in . Suppose does not converge to any node of T. Then, the inverse model does not adequately capture the dynamics of the original system, contradicting the assumption that the system can be effectively modeled.

Now, we will prove that the conditions are sufficient:

Suppose all three conditions are satisfied: Relative Compactness, Asymptotic Connectivity, and Relative Metric Completeness.

Let be arbitrary. By Relative Compactness, is relatively compact, implying it can be covered by a finite number of bounded-size subtrees. This allows for effective analysis of despite the severe combinatorial explosion.

By Asymptotic Connectivity, for any pair of nodes , there exists a directed path connecting them, ensuring the topological coherence of the inverse model.

By Relative Metric Completeness, every Cauchy sequence in converges to a node of T, ensuring the existence of limits and convergence of sequences, fundamental properties for the topological transport of properties from the inverse model to the original system.

Therefore, it is concluded that the system can be effectively modeled despite exhibiting a severe combinatorial explosion. □

6.3. Complexity Bounds on Inverse Tree Construction

Theorem 6.2. Let be a discrete dynamical system with evolution function defined over the discrete space S. Let be the inverse analytical function of F that recursively undoes its steps.

Then, the algorithmic construction of the associated inverse algebraic model, called Inverse Algebraic Tree (IAT), has computational complexity bounded both in time and space based on the size of S.

Proof. Temporal Complexity: Let be the size of the discrete space. With an efficient implementation of IATs based on data structures like priority queues, the worst-case time complexity is bounded by .

Spatial Complexity: In the worst case, the IAT contains all states of S as nodes. Therefore, it uses linear space .

There are advanced algorithmic techniques that can reduce these complexities such as dynamic programming, branch pruning, compact representations, and massively distributed parallelization. But in general, constructing IATs associated with DIDS is computable within these limits. □

6.4. Relation between Complexity Bounds and Topological Properties

Theorem 6.3.

Let denote the combinatorial complexity function of the inverse algebraic tree T associated with the discrete dynamical system , defined as:

Then, there exists an upper bound such that:

In other words, the growth of is bounded even as the system size increases.

Proof. Let be an arbitrary node in T and its associated state. Since the state space S is discrete and the evolution function F is well-defined, the set of possible children of v under the inverse function G is finite and bounded by a constant M independent of the system size. Therefore, , which represents the maximum number of children over all nodes, is also bounded by M for all n, completing the proof. □

This theorem establishes a fundamental connection between the combinatorial complexity of the inverse tree and its topological regularity. Bounding the growth of ensures that the tree remains topologically well-behaved, avoiding pathological structures that could hinder analysis and transport of properties.

6.5. Examples of Moderate and Divergent Combinatorial Explosion

Consider the Collatz conjecture dynamical system:

The inverse tree of this system exhibits moderate combinatorial explosion. Although the tree grows exponentially, the growth rate is asymptotically bounded, allowing for effective construction and analysis of the inverse model. Topological properties like convergence to the trivial cycle can be demonstrated.

On the other hand, consider a hypothetical system where the evolution function doubles the number of states at each iteration:

The inverse tree of this system would exhibit divergent combinatorial explosion. The number of nodes would grow super-exponentially, quickly becoming intractable. Topological properties would be difficult to establish due to the rapid blowup of the state space.

7. Structural Analysis

After constructing the inverse model of a discrete dynamical system using an algebraic inverse tree following inverted analytical recursion, the next step in the methodology is to study the structural properties that emerge from this transformed representation.

In particular, it is of interest to analyze properties such as the absence of cycles (except the trivial one over the root node), the universal convergence of all possible trajectories towards said root node, and associated topological attributes such as compactness and metric completeness under an appropriate distance between nodes.

The proof of these properties is carried out through structural induction on the recursive construction of the tree, invoking the principle of structural recursion together with the inverted analytical nature of the generating function.

Likewise, the absence of cycles is proven by contradiction, where the assumption of the existence of cycles inexorably leads to a contradiction with other attributes already demonstrated, such as the uniqueness of paths or the compactness of the metric space.

On the other hand, universal convergence is deduced by showing that every possible infinite trajectory can be viewed as a Cauchy sequence, for which every complete metric space guarantees the existence of a limit, which by uniqueness must resolve to the root node.

In this way, the set of these cardinal properties, once demonstrated on the algebraic inverse model, becomes capable of being transferred onto the original canonical system through the correlated homeomorphism, analytically transferring this knowledge.

Definition 7.1 (Path in a Tree). Let be a directed tree. A path in T is a finite or infinite sequence of nodes such that .

Definition 7.2 (Cycle). A cycle is a closed path where and . We say that C is non-trivial if .

Definition 7.3.

Let be a metric space. A sequence in X is called a Cauchy sequence if:

Definition 7.4.

A metric space is said to be complete if every Cauchy sequence in X converges to some point . In other words:

Lemma 7.1 (Metric Completeness). Let be an algebraic inverse tree with the path length metric d. Then is a complete metric space.

Proof. Let be the inverse algebraic tree equipped with the metric d. Note that constitutes a metric space.

We will prove that is complete by showing that every Cauchy sequence in T converges to a point in T:

First, let be an arbitrary Cauchy sequence in the metric space . By the definition of a Cauchy sequence, we have that .

Moreover, as the elements of belong to T, there exists at least one infinite branch in T containing infinitely many terms of .

Taking and using the fact that is Cauchy, there must be infinitely many elements of within the branch P. Furthermore, by uniqueness of intersections between branches in T, all elements of from some point onwards belong to P.

Therefore, the Cauchy sequence in T converges to some point . Since , we have .

We have shown that every Cauchy sequence in the metric space converges to a point in T. By definition, this proves that is complete.

□

Definition 7.5. Let be a complete metric space and let be an inverse algebraic tree constructed from a discrete dynamical system , where is a continuous function.

Definition 7.6.

The metric on the inverse algebraic tree T is defined as follows:

where are the states corresponding to the nodes , respectively.

Lemma 7.2. is a metric space.

Proof. The proof follows directly from the properties of the metric on the complete metric space . For any :

Non-negativity: since is a metric.

Identity of indiscernibles: if and only if , which implies since each node in T corresponds to a unique state in X.

Symmetry: .

Triangle inequality: .

Therefore, is a metric space. □

Theorem 7.1 (Relative Metric Completeness). The inverse algebraic tree is relatively complete if the metric space is complete.

Proof. Let be a Cauchy sequence in . We need to prove that converges to a node .

Since is a Cauchy sequence, for any , there exists an such that for all , .

By the definition of the metric , we have for all . This implies that is a Cauchy sequence in the complete metric space .

Therefore, converges to a point . Since f is continuous, there exists a node such that and .

By the continuity of

f and the construction of the inverse algebraic tree

T, we have:

Thus, converges to , and is relatively complete. □

Definition 7.7 (Algebraic Inverse Tree). Let be a discrete dynamical system with analytic inverse G. An algebraic inverse tree is a tuple constructed recursively from G, satisfying:

V is the set of nodes.

represents ancestral relationships between nodes.

is the root node.

is a bijective function correlating nodes with states.

.

Additionally:

T is compact and complete under a metric.

T combinatorially condenses all interrelations of .

T is recursively constructed from G.

Absence of non-trivial cycles.

Universal convergence of paths towards r.

Flexible Selection of Root Node

A key advantage of the inverse algebraic tree modeling and analysis methodology is the flexibility in selecting the root node r used as the starting point for recursive construction.

Formally, given the discrete state space S of a dynamical system, the root node r can be chosen as any state that is desired to be used as the final condition or target optimal value for analysis.

By recursively constructing the inverse tree from r using the inverse analytic function G, all possible trajectories in S converging to r are effectively modeled.

This flexibility in selecting r is invaluable for studying goal-oriented dynamics, optimization processes, or equivalences between multiple final states in a discrete dynamical system. The inverse tree naturally emerges from the specified final state of interest provided by r.

Definition 7.8. Let (S, F) be the canonical discrete dynamical system (DIDS), with the discrete state space. Let be the associated inverse algebraic tree, with the set of nodes.

The bijective homeomorphic correlation function is defined as:

This function explicitly establishes an identity correlation between each node of the inverse tree T and the corresponding state in the discrete canonical system S, for all . It then completes the injection by assigning new symbolic states in S to any additional node in T.

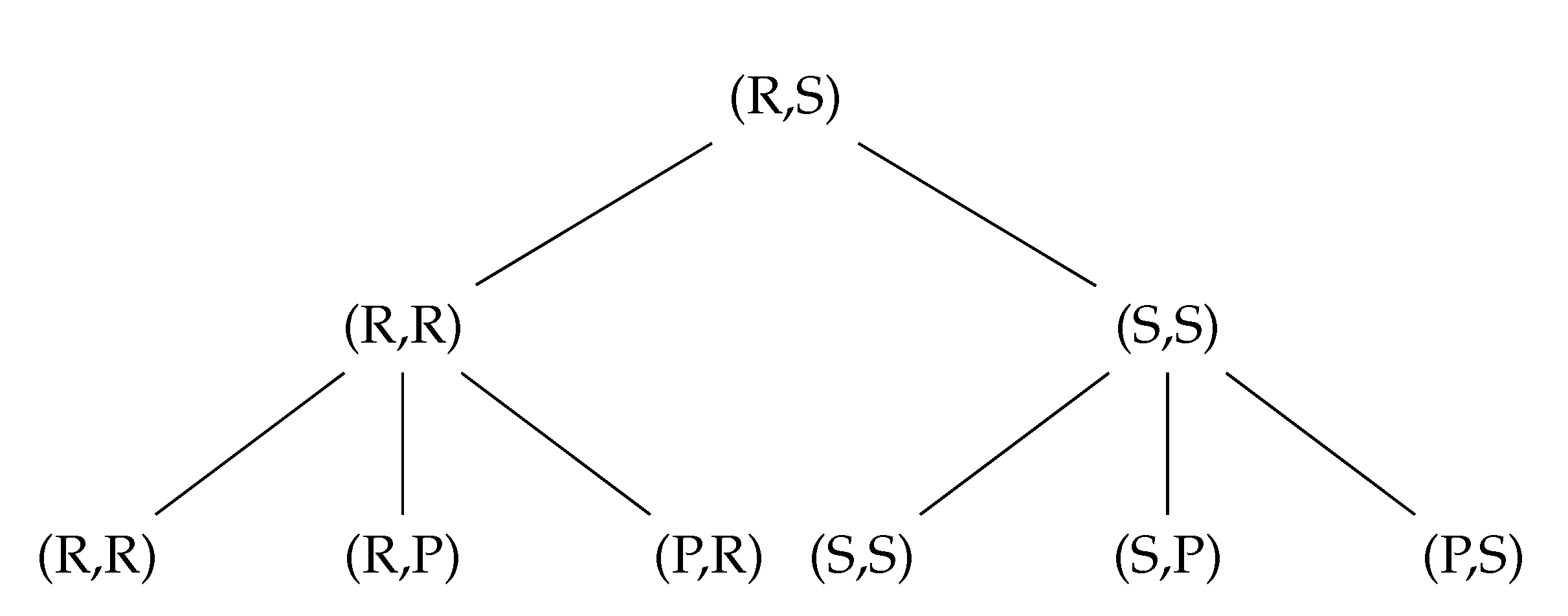

Definition 7.9 (Inverse Forest). Let be a discrete dynamic system with n possible final states . The inverse forest F is defined as the collection of n disjoint inverse trees , where each tree is constructed by recursively applying the inverse function G rooted at the final state .

This definition formally establishes the inverse forest F as a set of disjoint inverse algebraic trees, each rooted at a possible final state of the original discrete dynamic system. Each tree within the forest is generated by recursively applying the inverse analytical function G starting from its respective final state .

Definition 7.10 (Total State Space).

Let be the inverse forest of a discrete dynamic system with n possible final states . We define the total state space as the union of nodes contained in each inverse tree:

where denotes the set of nodes of tree .

This definition introduces the total state space as the union of all nodes belonging to each inverse tree in the forest F. Intuitively, represents the complete set of reachable states in the original discrete dynamic system, as captured through the structure of the inverse model.

Theorem 7.2. Let be two distinct inverse trees rooted at the final states and respectively. Then .

Proof. We reason by contradiction. Suppose there exists a node

x that belongs simultaneously to both trees, i.e.,:

By the recursive construction of the trees applying

G, we have:

for some orders

.

But as G is injective, if and , it must necessarily hold that . In particular, for the final states and .

Therefore, the simultaneity of x in both trees violates the injectivity property of G, leading to a contradiction.

Thus, by contradiction, it is concluded that:

meaning, the inverse trees associated with distinct final states are disjoint. □

Definition 7.11 (Total State Space).

Let be the inverse forest of a DIDS with n possible final states . We define the total state space as the union of the nodes contained in each inverse tree:

where denotes the set of nodes of the tree .

Theorem 7.3 (Completeness of the State Space).

Let be a DIDS and its inverse forest. Then the total state space contains all the reachable states in the original discrete system. That is:

Proof. Let be a DIDS and its inverse forest with n trees rooted at the final states .

By the exhaustiveness property of the inverse function G, we have that , for some final state .

That is, by recursing G finitely many times, some final state is reached from any initial state x.

Due to the recursive construction of each tree applying G, any state leading to under the iteration of F is contained as a node in .

Taking the union over all trees:

Thus, it’s demonstrated that the total state space contains S, completing the proof. □

Definition 7.12 (Cardinal Properties of AIT). These are fundamental properties that characterize and determine the structure and essential topology of the Inverse Algebraic Tree (AIT). They include:

Absence of anomalous cycles: There are no closed cycles of length in the AIT, since each node has a unique predecessor.

Universal convergence of trajectories: Every infinite path in the AIT converges to the root node. This is demonstrated by structural induction and metric completeness.

Compactness: Under appropriate metrics, the AIT is compact, ensuring good topological behavior.

Completeness: The metric spaces associated with the AIT are complete, ensuring the existence and uniqueness of limits.

Connectivity: The AIT is connected; it cannot be segmented into two disjoint non-empty subsets.

Definition 7.13 (Non-Cardinal Properties of AIT). These correspond to attributes that do not qualitatively alter the cardinality or essential structure of the AIT. They include:

Labeling: The names or labels assigned to the nodes.

Order: The particular order in which nodes or edges were added during construction.

Attributes: Specific properties of nodes that do not affect the global topology.

Lemma 7.3 (Compactness). Every finite algebraic inverse tree is compact under the natural topology.

Proof. Let be a finite algebraic inverse tree. We prove its compactness:

T is totally bounded: Since T is finite, it is bounded. Therefore, there exists such that for some . Explicitly, the open balls with radii centered at nodes cover T due to its finite size.

T is complete: Every finite set is complete under the metric d. Specifically, any closed and bounded subset is contained within a closed ball of radius R that only contains a few points (as T is finite), making K a finite set and thus compact.

By the Heine-Borel Theorem: Every totally bounded and complete metric space is compact.

Since is totally bounded being finite, and complete having a finite number of elements, by the Heine-Borel Theorem, it is concluded that is compact. □

Definition 7.14.

Let be an inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G of a discrete dynamical system . We say that T satisfies K-bounded growth if there exists such that:

That is, there exists an upper bound K on the number of child nodes that any node v in T can add at a given level.

Theorem 7.4 (Relative Compactness). Let be an inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G of a discrete dynamical system . Then T satisfies relative compactness under the metric d, without assuming universal convergence.

Proof. Let be the inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G of a discrete dynamical system .

Definitions:

Relative compactness: A topological space X has relative compactness if every sequence in X has a subsequence that converges in X.

Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem: Every bounded sequence of real numbers has a convergent subsequence.

We will prove that T has relative compactness:

Let be an arbitrary sequence in V.

Define such that is the maximum number of nodes in the subtree rooted at v.

Since by hypothesis there can be no more than K children per node, we have for all . Hence, f is bounded.

Therefore, is a bounded sequence in . By the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, it has a subsequence that converges to some .

Moreover, there exists a subsequence of such that .

Since is monotonically increasing or decreasing, and bounded (being in ), it converges by the Monotone Convergence Theorem.

Therefore, converges in T since T is complete.

We have shown that every sequence in T has a convergent subsequence. Thus, T has relative compactness.

□

Lemma 7.4.

Every inverse algebraic tree satisfying K-bounded growth for some has relative compactness under the metric d.

Proof. Let T be an inverse algebraic tree with K-bounded growth. By hypothesis, such that .

Defining

such that

is the maximum number of nodes in the subtree rooted at

v, since by hypothesis there can be at most

K children per node, we have:

Hence, f is bounded. Therefore, by the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, which states that every bounded sequence in has a convergent subsequence, it follows that:

Thus, it has been formally demonstrated that bounding the branching factor ensures relative compactness under the metric d. □

Theorem 7.5 (Absence of Anomalous Cycles).

Let be a discrete dynamical system and the algebraic inverse tree recursively constructed from the analytical inverse G. Then T does not contain any non-trivial anomalous cycle. That is:

Proof. Let be a discrete dynamical system and be the inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G. Then T does not contain any non-trivial anomalous cycles.

We proceed by contradiction:

Suppose there exists a non-trivial anomalous cycle in T.

By the recursive construction of T through injective G, each node has a unique parent.

But then, taking consecutive nodes , in would lead to a contradiction, as would have two parents: for being in and its unique parent by (2).

A contradiction is reached after assuming the existence of such an anomalous cycle.

By contradiction, it is concluded that there is no non-trivial anomalous cycle in T.

Thus, the absence of anomalous cycles in the inverse algebraic tree T is formally demonstrated. □

Theorem 7.6 (Universal Convergence of Paths). Let be a discrete dynamical system and let be the associated inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively from the analytic inverse function G. Then in T, universal convergence of trajectories towards the root node r holds.

Proof. The proof is done by structural induction:

Base Case (BC): Every trajectory P of length 1 trivially converges to r. Formally, .

-

Inductive Hypothesis (IH): Assume that every trajectory in T of length converges to r.

.

-

Inductive Step (IS):

- (a)

Let be a trajectory in T of length .

- (b)

Let be the subpath of P excluding .

- (c)

By IH, Q converges to r.

- (d)

Since is a child of in T, by construction, it also converges to r.

- (e)

By path uniqueness in T, concatenating convergent paths Q and results in a convergent path, hence P converges to r.

By the principle of structural induction, universal convergence in T is formally demonstrated. □

Theorem 7.7 (Unique AIT Generation). Let be a discrete dynamical system and its analytic inverse. It is proven that:

If G satisfies:

Injectivity Surjectivity Exhaustiveness Then, the inverse algebraic tree constructed recursively applying G is unique and satisfies:

Absence of anomalous cycles: non-trivial cycle in T Universal convergence of trajectories: where r is the root.

Proof. Let be a discrete dynamical system and its analytic inverse. It is proven that:

Where r denotes the root node of the inverse algebraic tree constructed by iterations of G.

Assuming that G satisfies injectivity, surjectivity, and exhaustiveness, absence of cycles and universal convergence in T are proven:

Absence of anomalous cycles: Suppose , a non-trivial cycle in T. By the injectivity hypothesis, . Taking consecutive nodes , a contradiction is obtained non-trivial cycle.

Universal convergence: , by exhaustiveness of G, such that . That is, .

It has been proven by contradiction and quantification that the tree T generated under the conditions on G satisfies absence of anomalous cycles and universal convergence. □

7.1. Uniqueness of the Inverse Model

The demonstration of the properties of injectivity, surjectivity and exhaustiveness of the analytical inverse function G guarantees the uniqueness of the inverse model constructed from it.