Submitted:

09 March 2024

Posted:

12 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

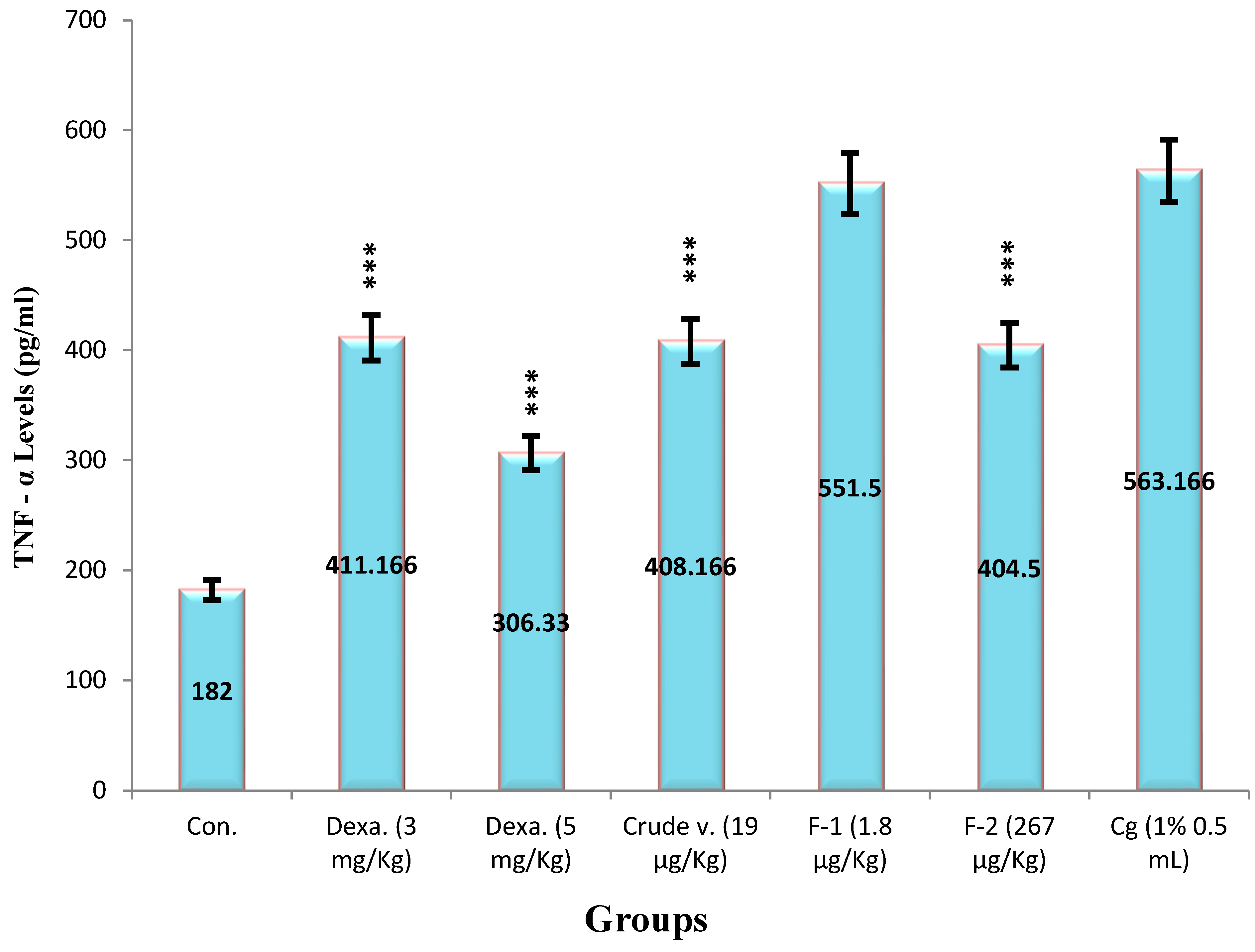

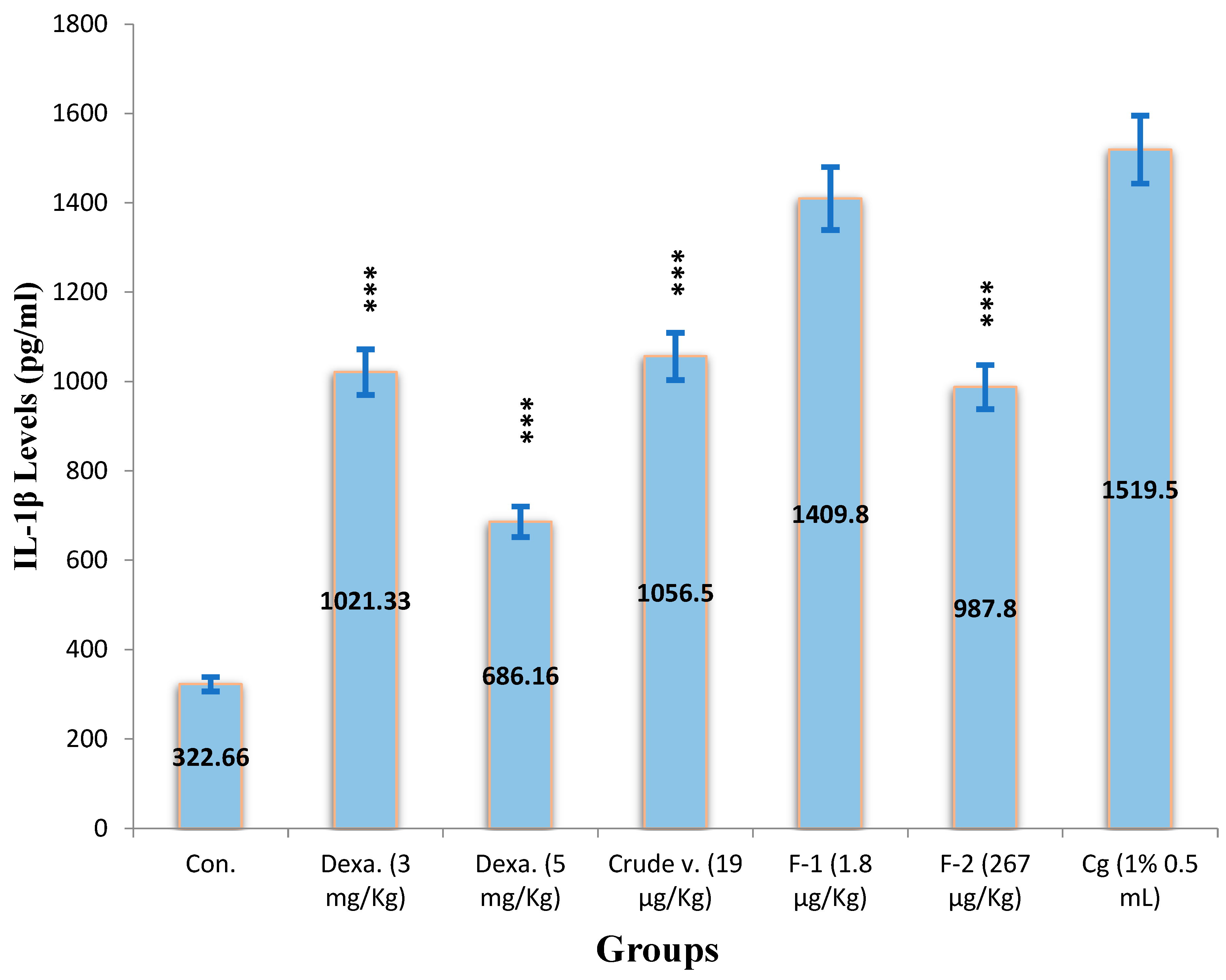

Results

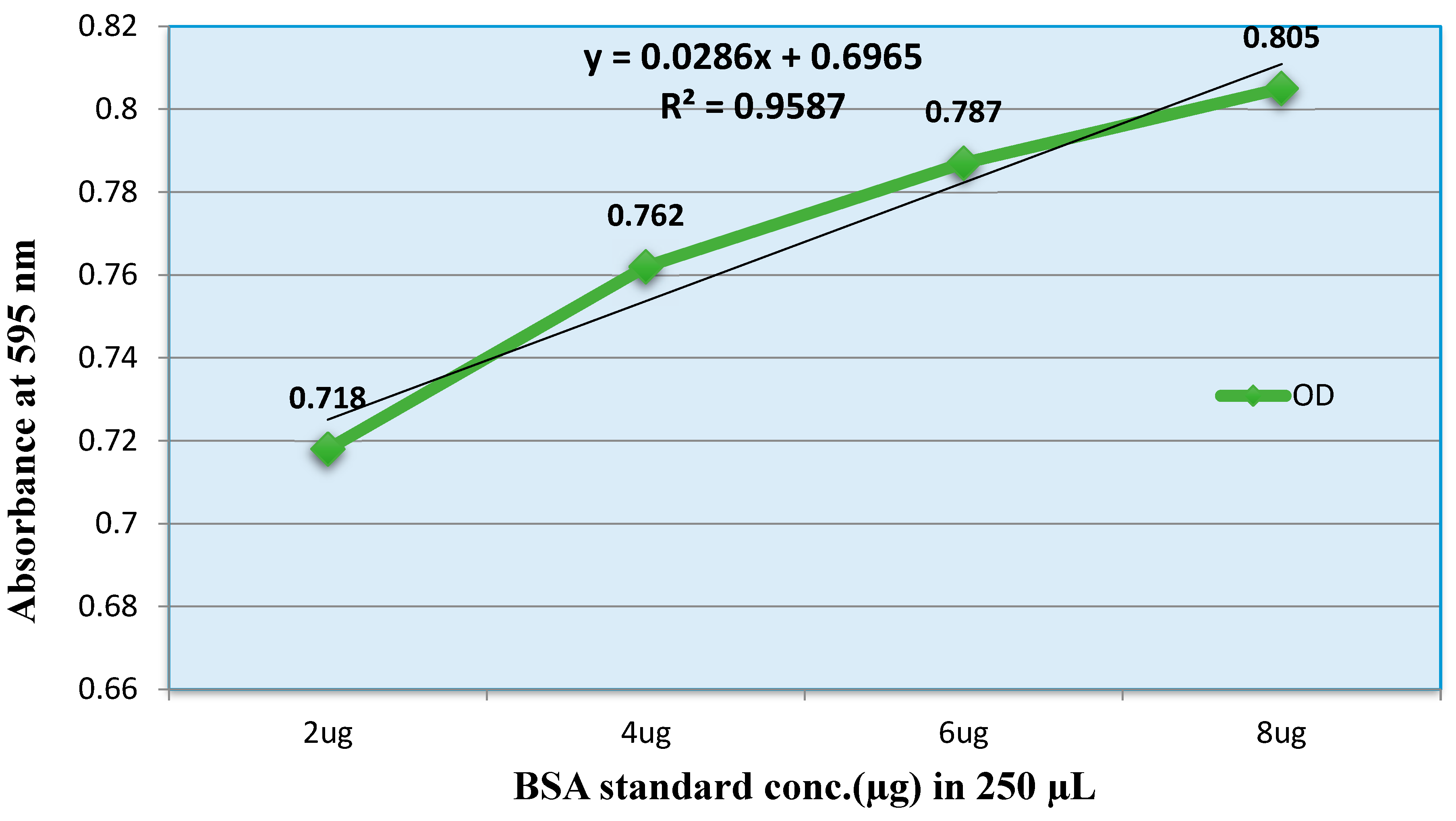

2. Protein Estimation

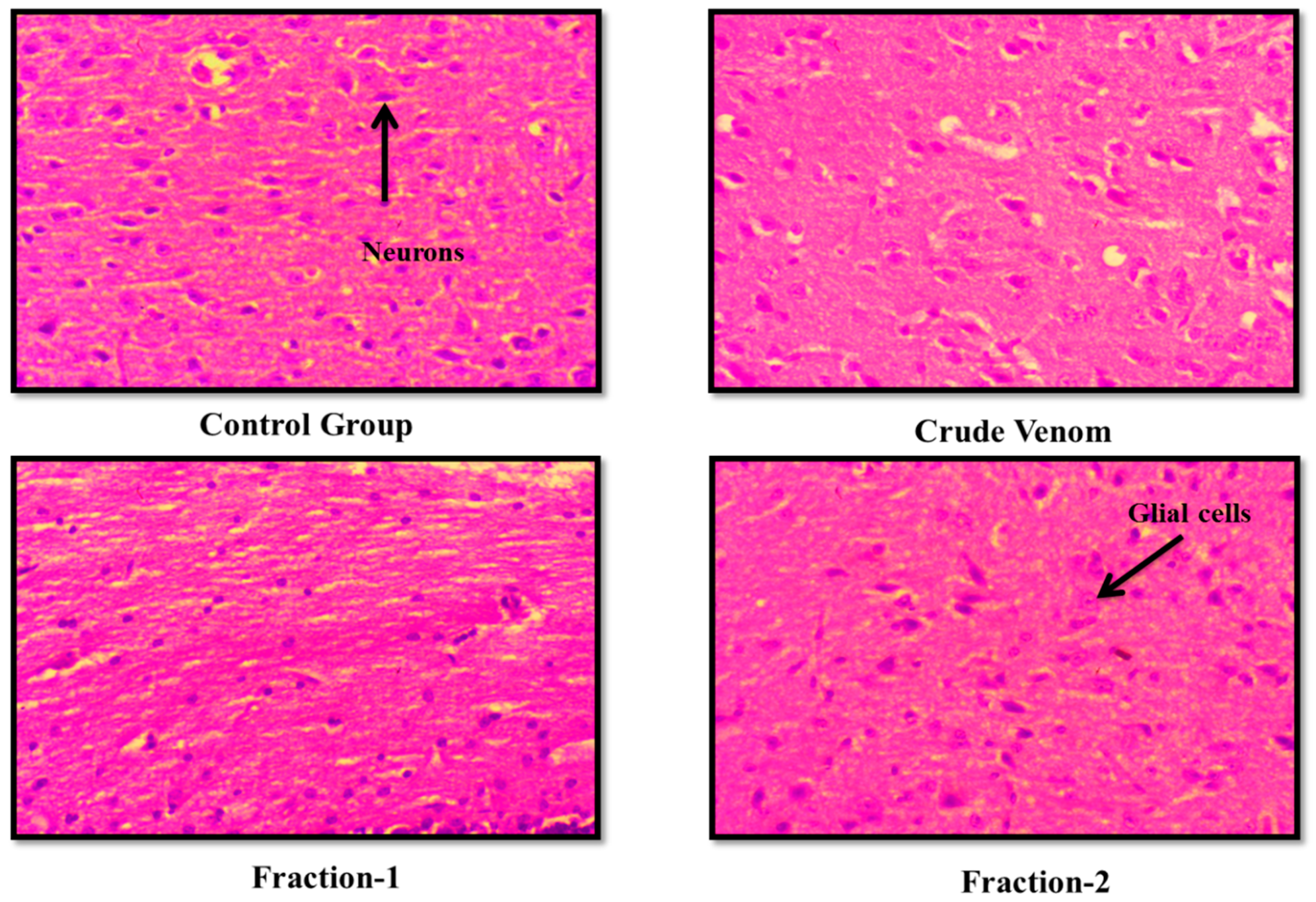

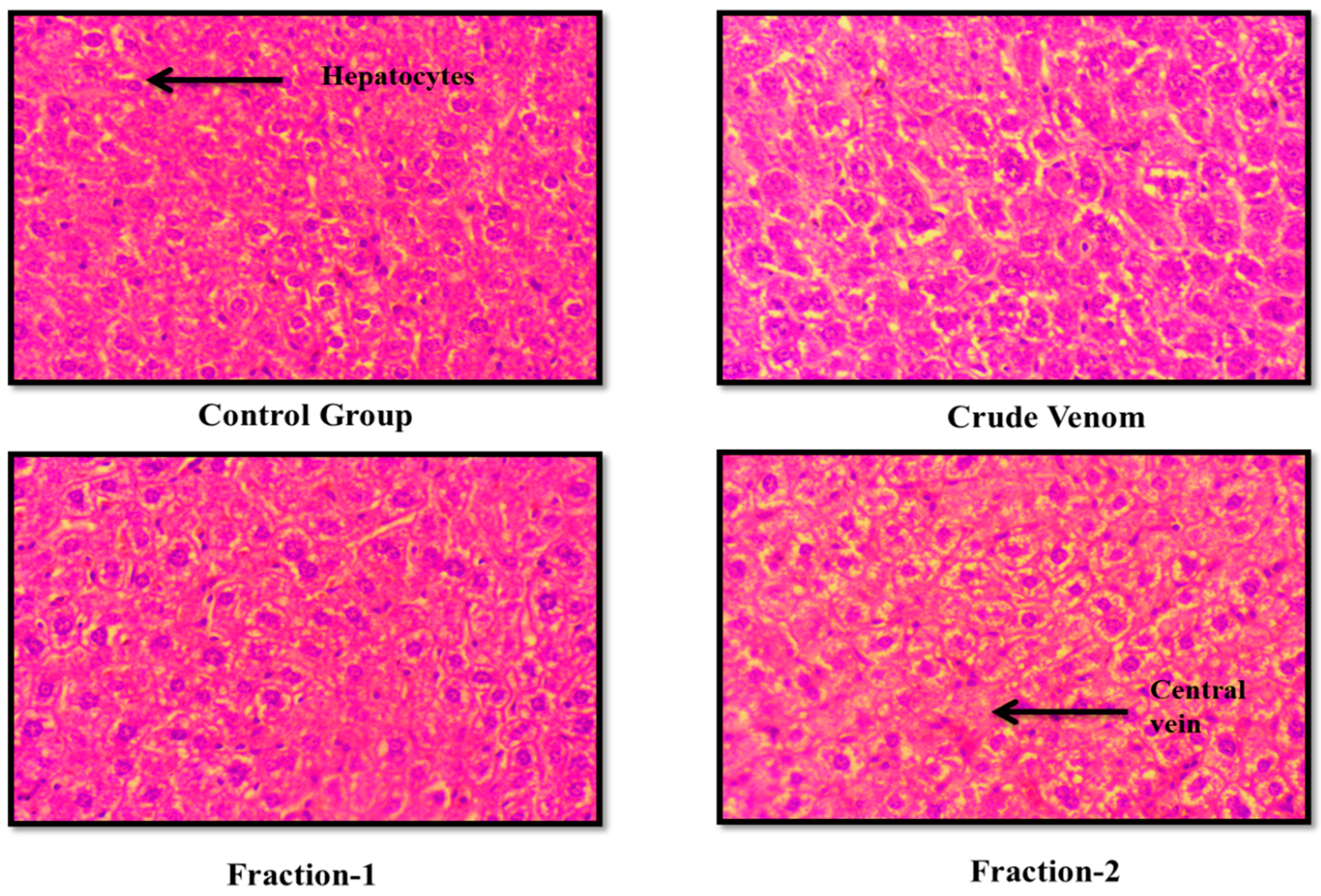

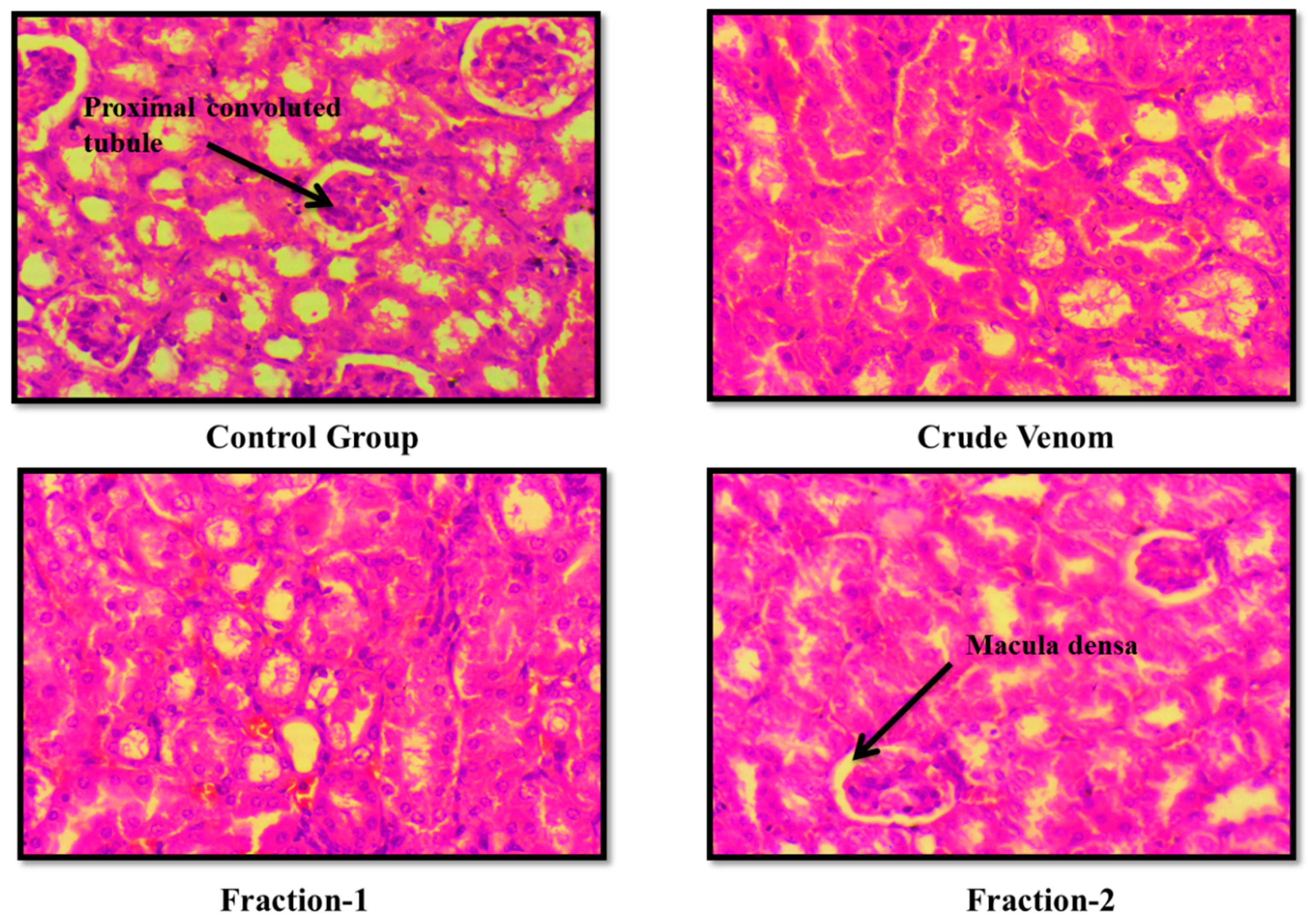

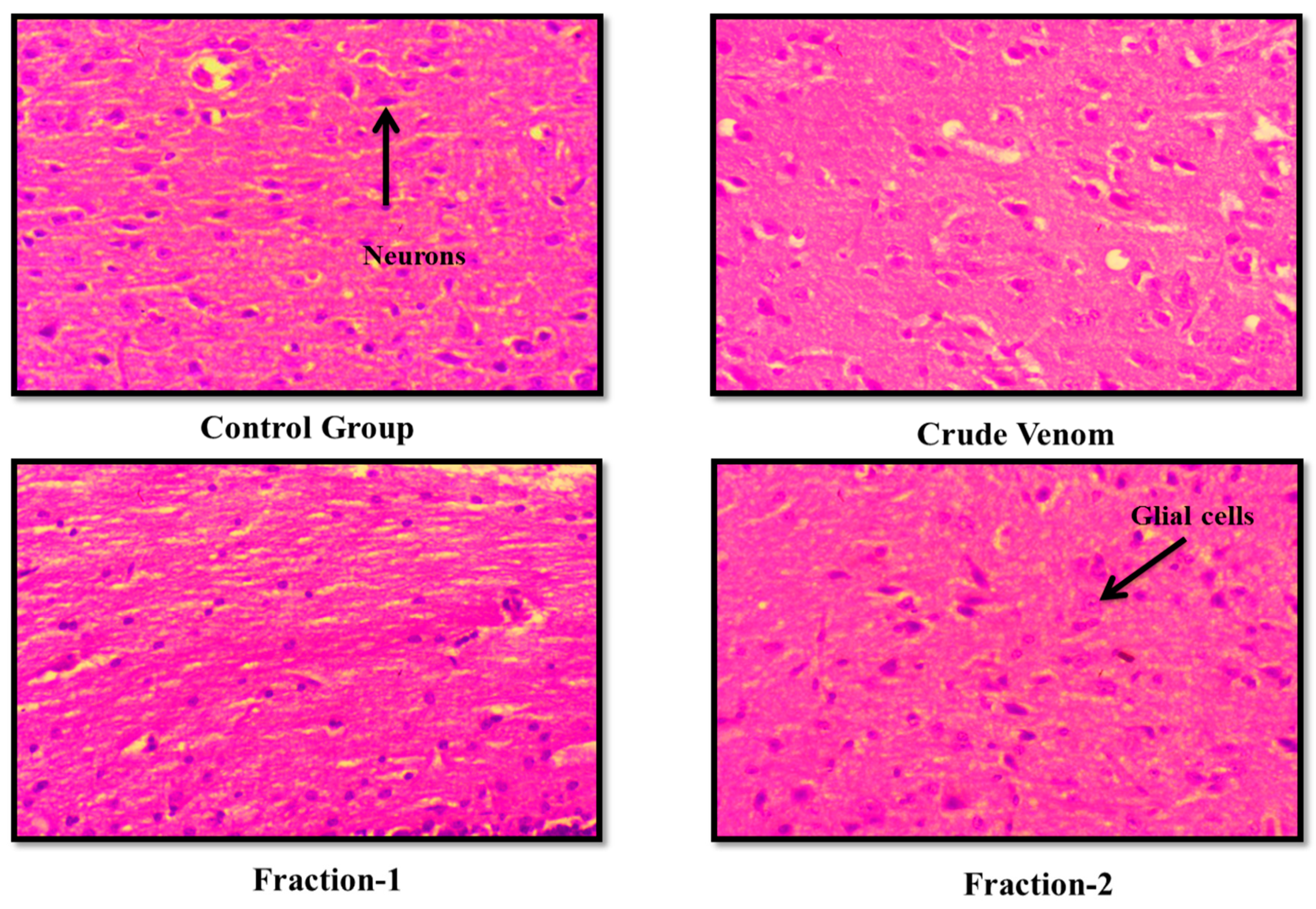

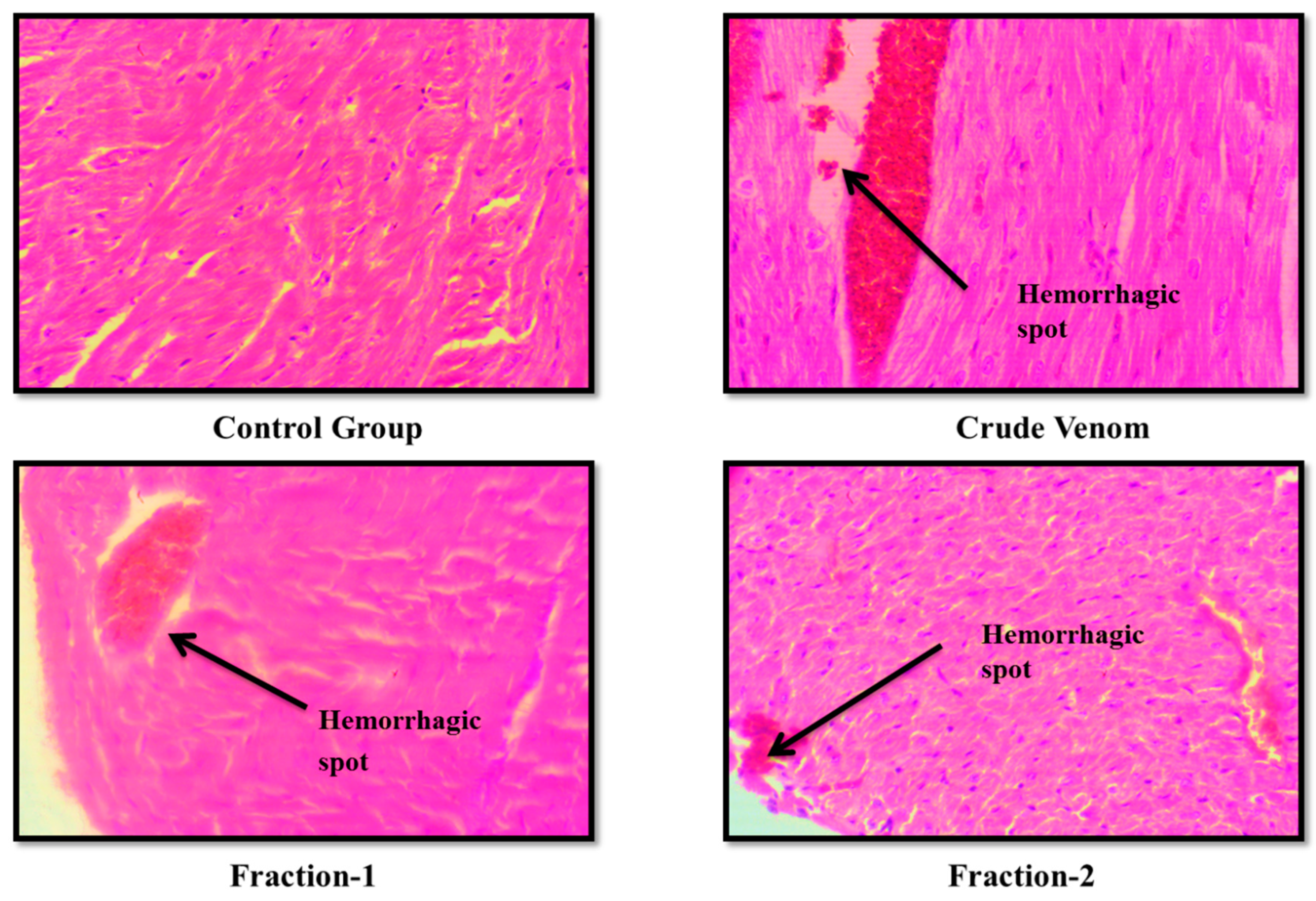

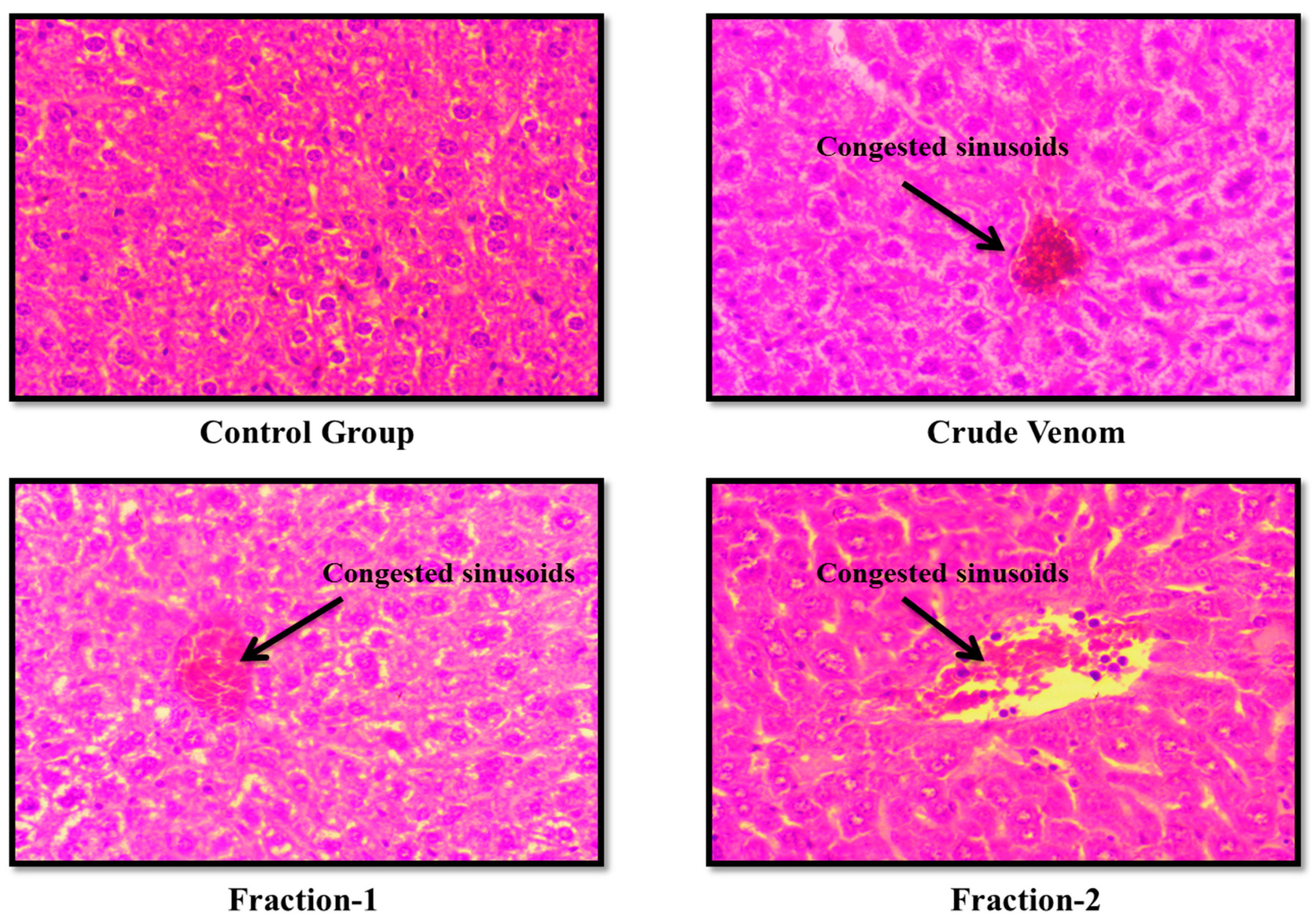

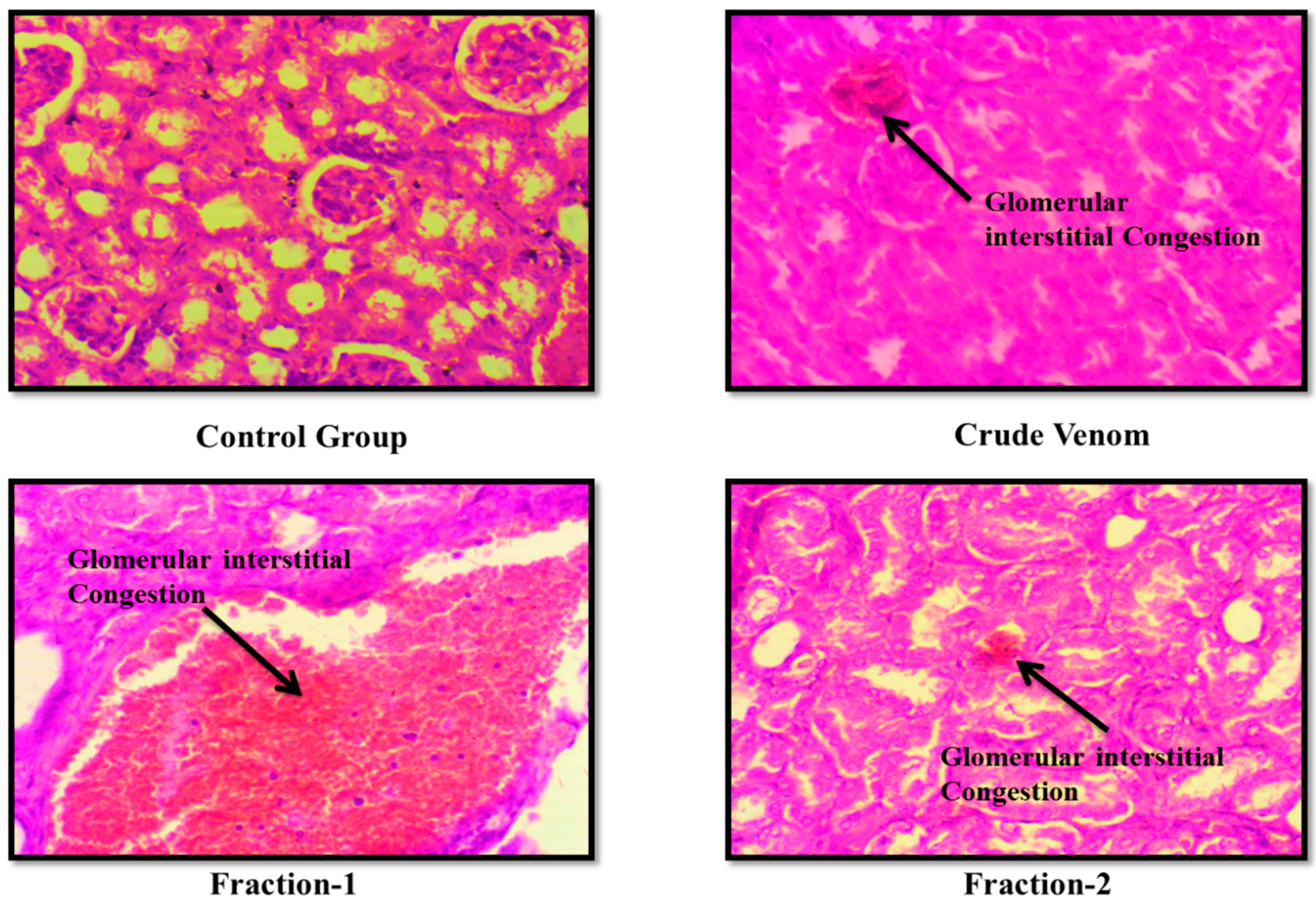

2.Toxicity Studies

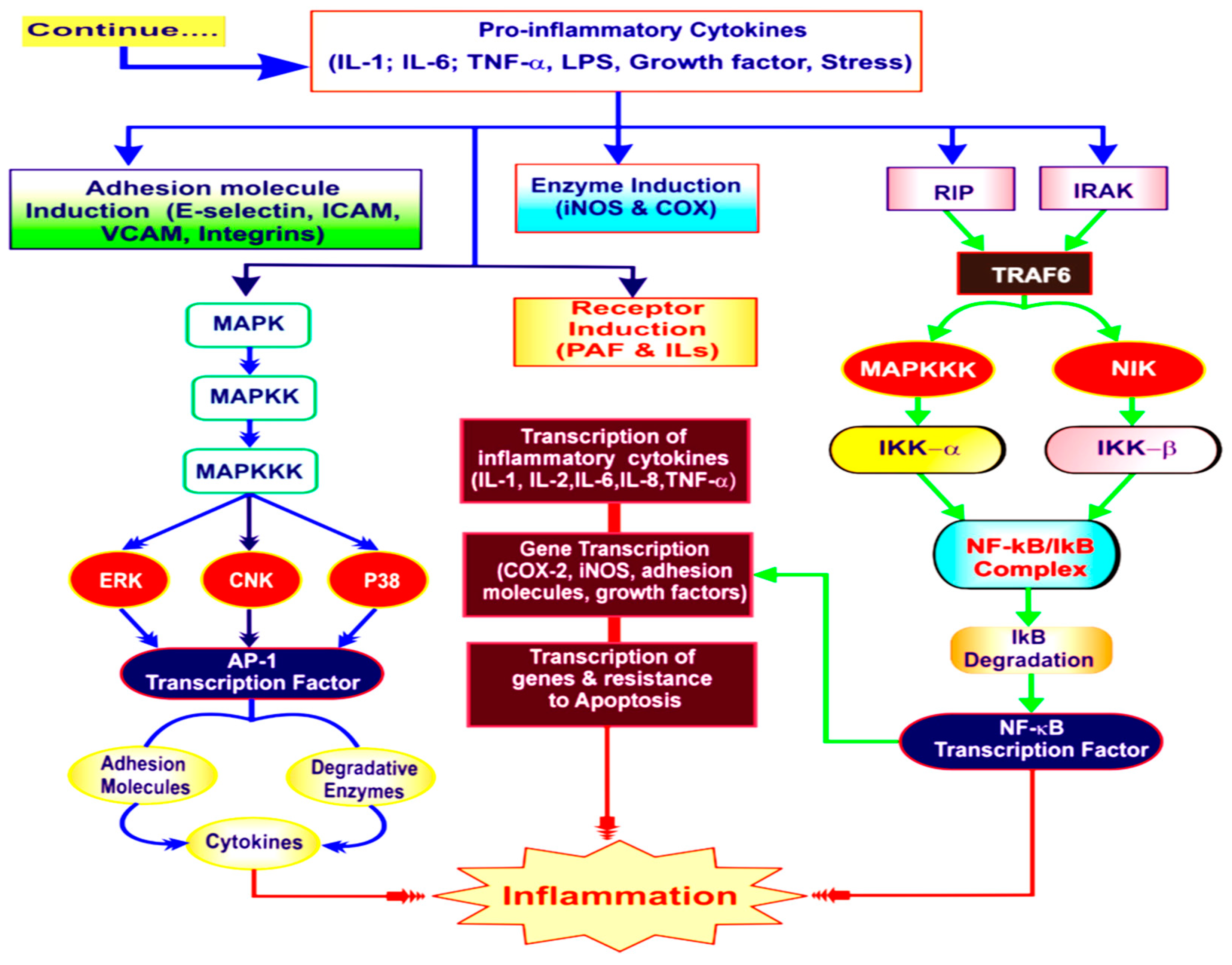

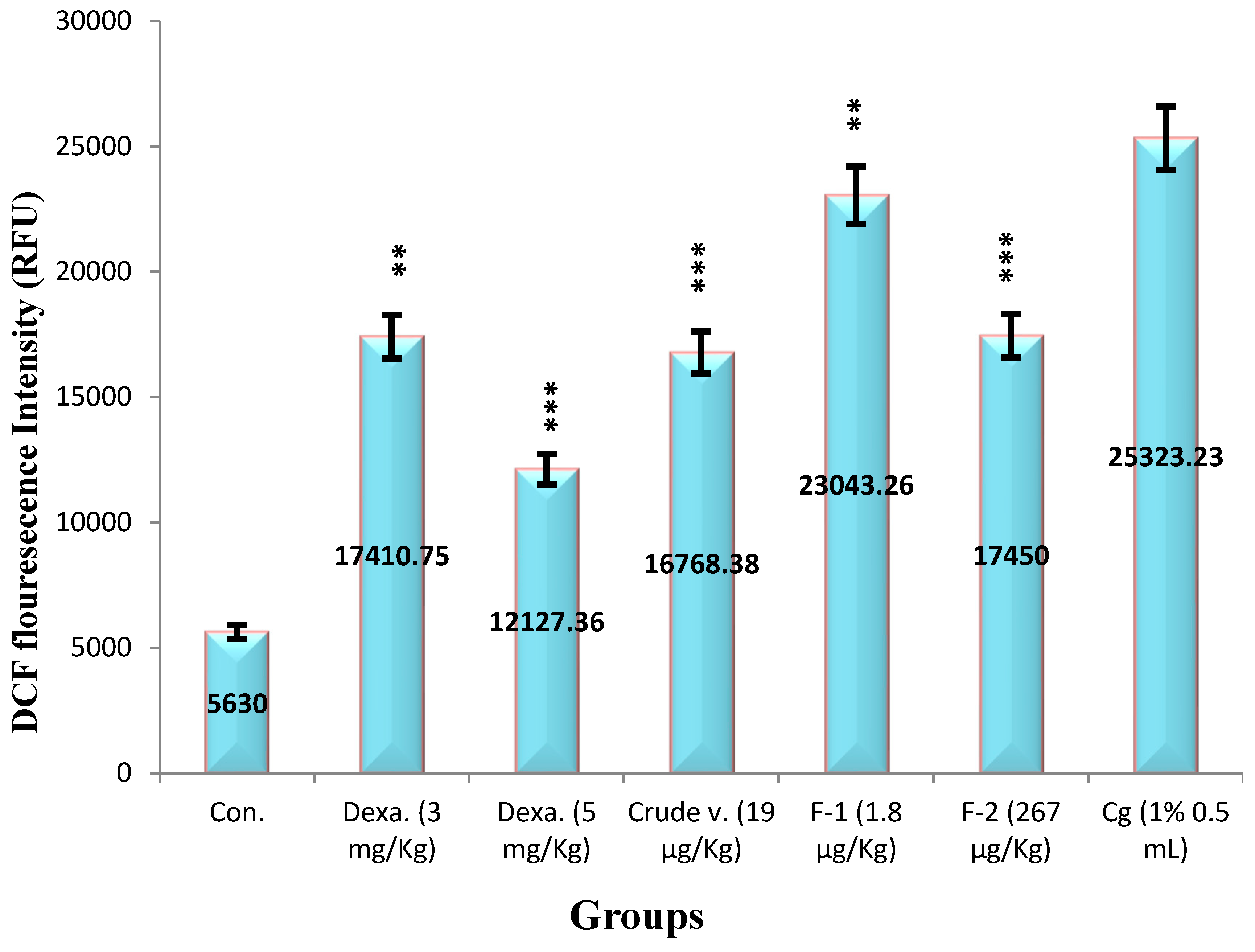

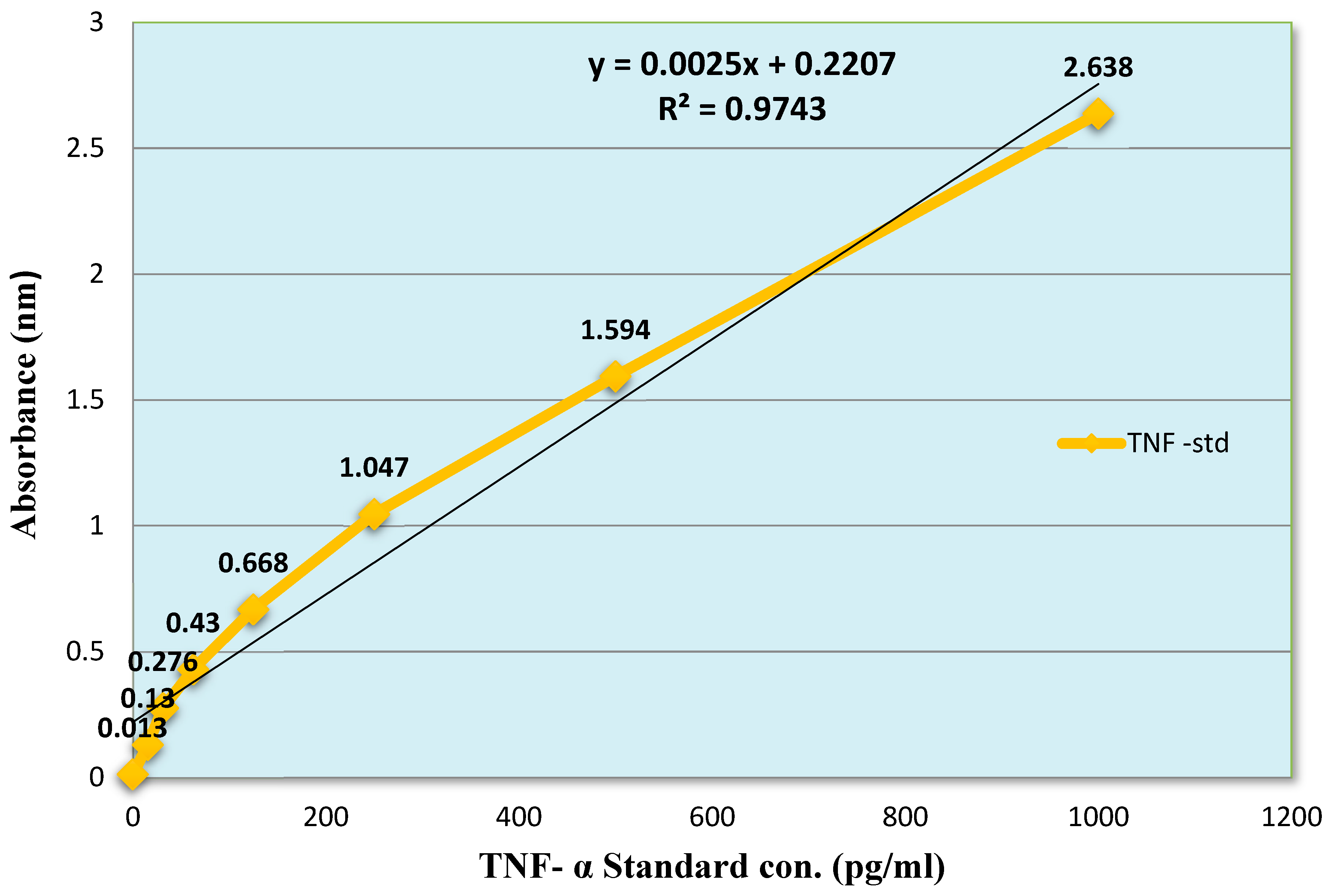

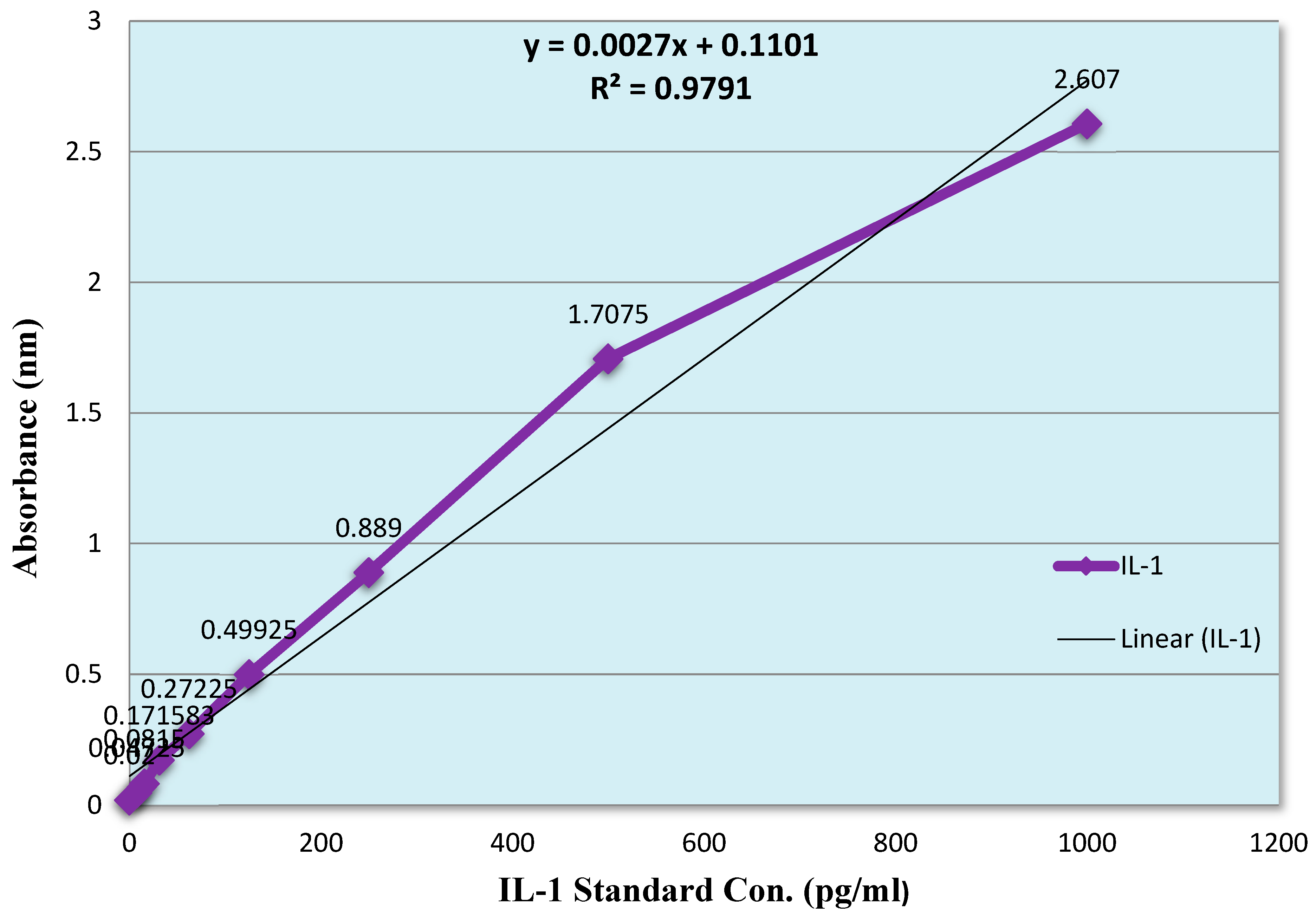

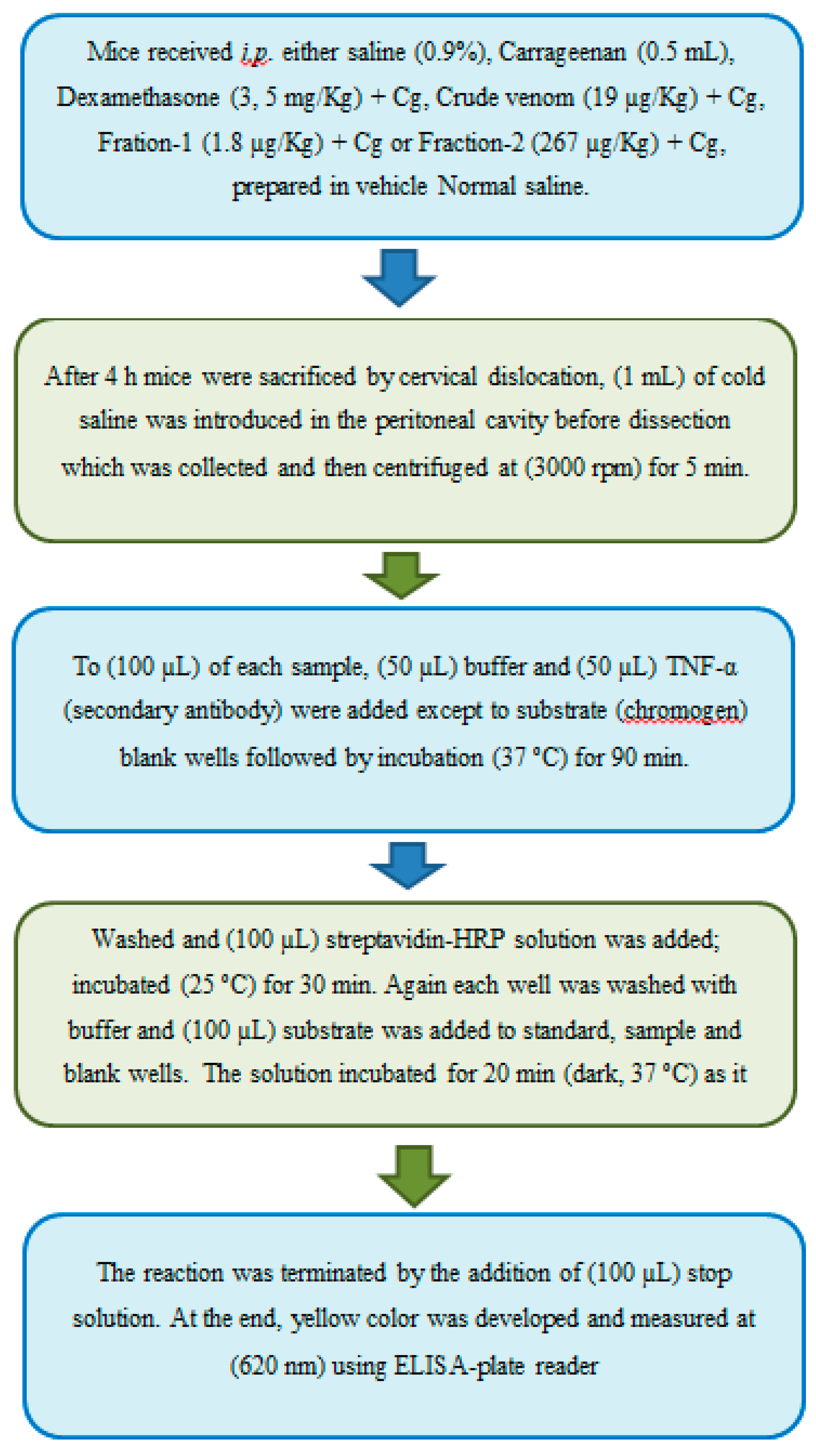

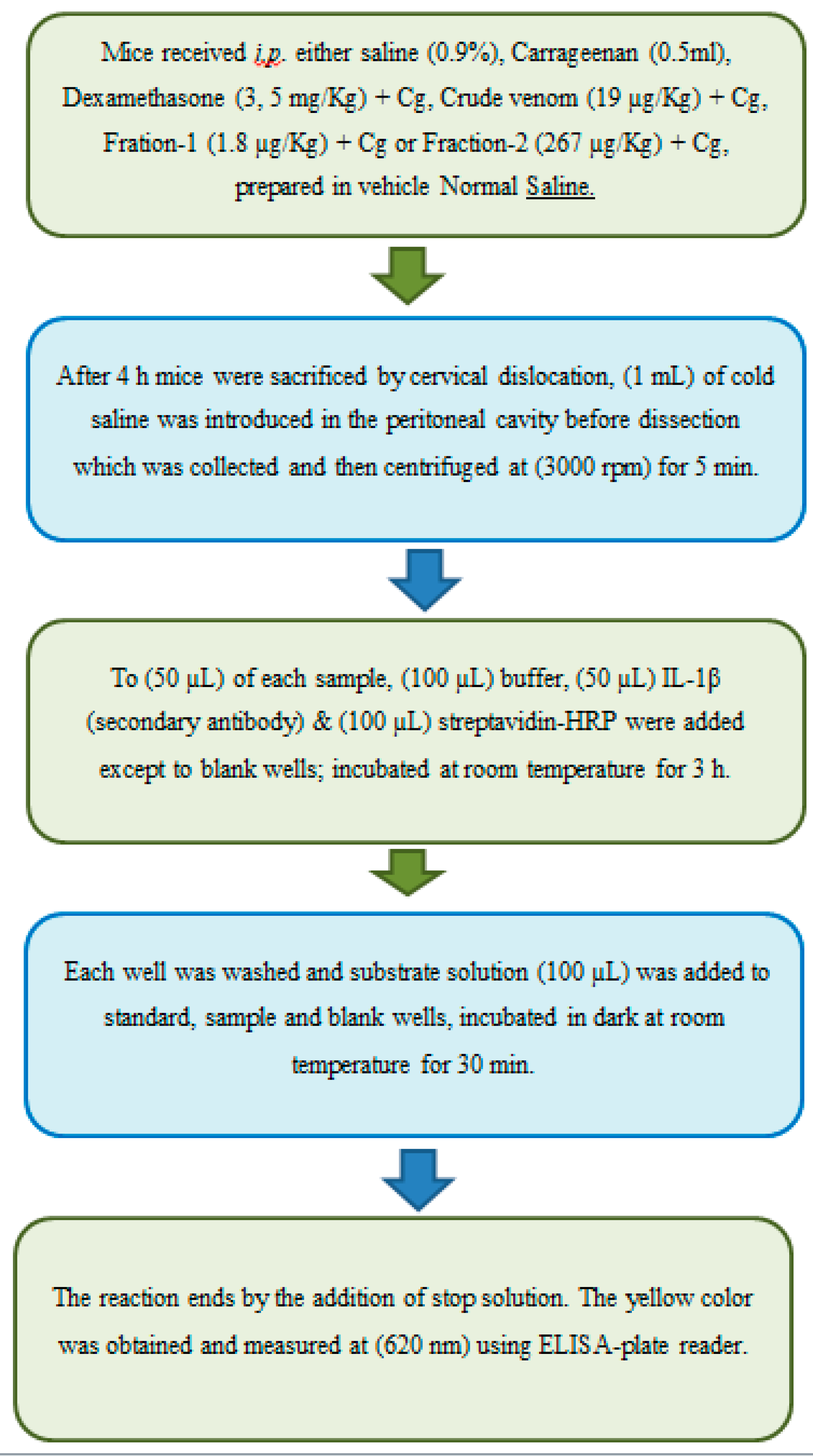

2.Anti-Inflammatory Effect

Discussion

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection:

Protein Fractionation

Protein Estimation

Material

Animals

Median Lethal Dose (LD50) Determination

Toxicity Experiment

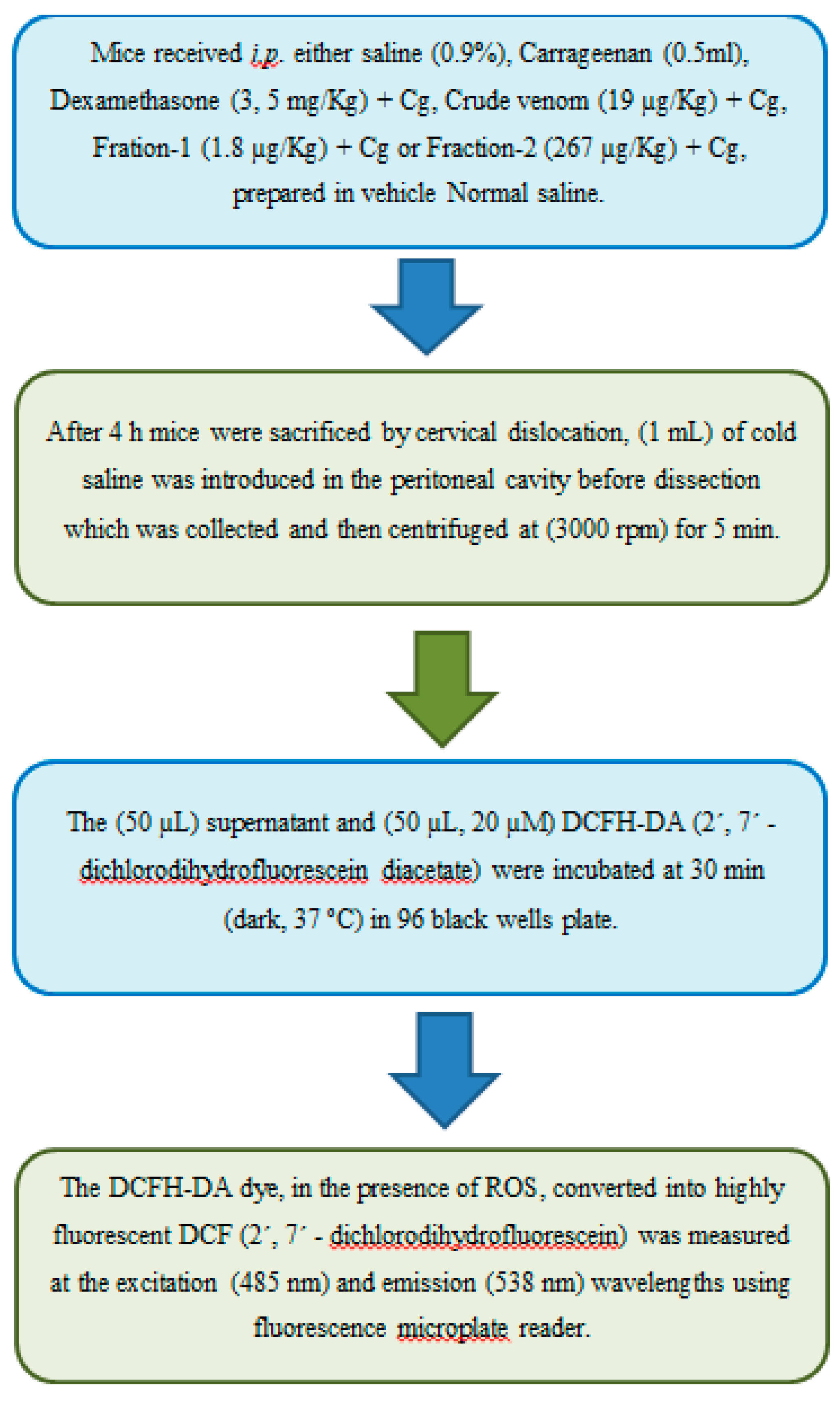

Anti-Inflammatory Study

Statistical Analysis

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, A.W. Early drug discovery and the rise of pharmaceutical chemistry. Drug testing and analysis. 2011, 3, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, D.A.; Urban, S.; Roessner, U. A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites. 2012, 2, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Kong, L.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Guo, M.; Zou, H. Strategy for analysis and screening of bioactive compounds in traditional Chinese medicines. Journal of chromatography B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2004, 812, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, K.R.; Mahajan, U.B.; Unger, B.S.; Goyal, S.N.; Belemkar, S.; Surana, S.J.; et al. Animal models of inflammation for screening of anti-inflammatory drugs: Implications for the discovery and development of phytopharmaceuticals. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019, 20, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Anjum, S.; El-Seedi, H. Natural Products in Clinical Trials: Bentham Science Publishers, 2018.

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Ratner, R.E.; Han, J.; Kim, D.D.; Fineman, M.S.; Baron, A.D. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2005, 28, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, S.; Amso, Z.; Shen, W. Chapter Eight - Engineering PEG-fatty acid stapled, long-acting peptide agonists for G protein-coupled receptors. In: Shukla AK, editor. Methods in Enzymology. 622: Academic Press, 2019. p. 183-200.

- Farzad, R.; Gholami, A.; Hayati Roodbari, N.; Shahbazzadeh, D. The anti-rabies activity of Caspian cobra venom. Toxicon. 2020, 186, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallahi, N.; Shahbazzadeh, D.; Maleki, F.; Aghdasi, M.; Tabatabaie, F.; Khanaliha, K. The In Vitro Study of Anti-leishmanial Effect of Naja naja oxiana Snake Venom on Leishmania major. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2020, 20, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- verin, A.S.; Utkin, Y.N. Cardiovascular Effects of Snake Toxins: Cardiotoxicity and Cardioprotection. Acta Naturae. 2021, 13, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kini, R.M.; Koh, C.Y. Snake venom three-finger toxins and their potential in drug development targeting cardiovascular diseases. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2020, 181, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; Chew, D.P. Bivalirudin: An anticoagulant for acute coronary syndromes and coronary interventions. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2002, 3, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, J.F.; Alkawi, A.; Panezai, S.; Gizzi, M. Advances in thrombolytics for treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2012, 79, S119–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ming, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Qiu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; et al. Cytotoxin 1 from Naja atra Cantor venom induced necroptosis of leukemia cells. Toxicon : Official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 2019, 165, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashkooli, S.; Khamehchian, S.; Dabaghian, M.; Namvarpour, M.; Tebianian, M. Effects of Adjuvant and Immunization Route on Antibody Responses against Naja Naja oxiana Venom. Arch Razi Inst. 2023, 78, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, A.T. Neurotoxins of Animal Venoms: Snakes. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1973, 42, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Gomes, A.; Dasgupta, S.C.; Gomes, A. Snake venom as therapeutic agents: From toxin to drug development. Indian journal of experimental biology. 2002, 40, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Mishra, R.; Gomes, A. Anti-arthritic activity of Indian monocellate cobra (Naja kaouthia) venom on adjuvant induced arthritis. Toxicon : Official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 2010, 55, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.P.; Bhowmik, T.; Dasgupta, A.K.; Gomes, A. In vivo and in vitro toxicity of nanogold conjugated snake venom protein toxin GNP-NKCTToxicol Rep. 2014, 1, 74–84. 1.

- Kularatne, S.A.M.; Senanayake, N. Chapter 66 - Venomous snake bites, scorpions, and spiders. In: Biller J, Ferro JM, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 120: Elsevier, 2014. p. 987-1001.

- Leviton, A.E. Chapter 18 - The Venomous Terrestrial Snakes of East Asia, India, Malaya, and Indonesia. In: BÜCherl W, Buckley EE, Deulofeu V, editors, Venomous Animals and their Venoms: Academic Press, 1968. p.529-76.

- Wüster, W. Taxonomic changes and toxinology: Systematic revisions of the asiatic cobras (Naja naja species complex). Toxicon : Official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 1996, 34, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, M.T.; Asad, M.H.; Khan, T.; Chaudhary, M.Z.; Ansari, M.T.; Arshad, M.A.; et al. Antihaemorrhagic potentials of Fagonia cretica against Naja naja karachiensis (black Pakistan cobra) venom. Natural product research. 2011, 25, 1902–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Fahim, A. Possible recovery from an acute envenomation in male rats with LD50 of Echis coloratus crude venom: I-A seven days hematological follow-up study. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2012, 19, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izidoro, L.F.M.; Sobrinho, J.C.; Mendes, M.M.; Costa, T.R.; Grabner, A.N.; Rodrigues, V.M.; et al. Snake venom L-amino acid oxidases: Trends in pharmacology and biochemistry. Biomed Res Int. 2014, 2014, 196754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-de-Oliveira, C.; Stuginski, D.R.; Kitano, E.S.; Andrade-Silva, D.; Liberato, T.; Fukushima, I.; et al. Dynamic Rearrangement in Snake Venom Gland Proteome: Insights into Bothrops jararaca Intraspecific Venom Variation. Journal of Proteome Research. 2016, 15, 3752–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, S.N.; Bagheri, K.P.; Maghsoudi, H.; Shahbazzadeh, D. Oxineur, a novel peptide from Caspian cobra Naja naja oxiana against HT-29 colon cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2023, 1867, 130285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, S.; McDowell, D.; Cartagena, A.; Rodriguez, R.; Laughlin, T.F.; Ahmad, Z. Venom peptides cathelicidin and lycotoxin cause strong inhibition of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2016, 87, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, S.; Suzuki, T. Enzymes in Snake Venom. In: Lee C-Y, editor. Snake Venoms. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1979. p. 61-158.

- King, G.F. Venoms as a platform for human drugs: Translating toxins into therapeutics. Expert opinion on biological therapy. 2011, 11, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D.C.; Armugam, A.; Jeyaseelan, K. Snake venom components and their applications in biomedicine. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2006, 63, 3030–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, D.C.; Alvarez Abreu, P.; de Freitas, C.C.; Santos, D.O.; Borges, R.O.; Dos Santos, T.C.; et al. Snake Venom: Any Clue for Antibiotics and CAM? Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : Ecam. 2005, 2, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi G-n Liu Y-l Lin H-m Yang S-l Feng Y-l Reid, P.F.; et al. Involvement of cholinergic system in suppression of formalin-induced inflammatory pain by cobratoxin. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011, 32, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.Z.; Liu, Y.L.; Gu, J.H.; Qin, Z.H. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of orally administrated denatured naja naja atra venom on murine rheumatoid arthritis models. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2013, 2013, 616241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.M.; Koh, J.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, C.; Koh, S.J.; Kim, B.; et al. NF-kappa B activation correlates with disease phenotype in Crohn’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0182071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.H.; Pajarinen, J.; Lu, L.; Nabeshima, A.; Cordova, L.A.; Yao, Z.; et al. NF-kappaB as a Therapeutic Target in Inflammatory-Associated Bone Diseases. Advances in protein chemistry and structural biology. 2017, 107, 117–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008, 132, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipniacki, T.; Paszek, P.; Brasier, A.R.; Luxon, B.; Kimmel, M. Mathematical model of NF-kappaB regulatory module. Journal of theoretical biology. 2004, 228, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.R.; Mu, T.C.; Gao, Z.X.; Wang, J.; Sy, M.S.; Li, C.Y. Prion protein is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha)-triggered nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) signaling and cytokine production. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2017, 292, 18747–18759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-Z.; He, H.; Han, R.; Zhu, J.-L.; Kou, J.-Q.; Ding, X.-L.; et al. The Protective Effects of Cobra Venom from Naja naja atra on Acute and Chronic Nephropathy. Evid Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 478049. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.H.; Song, H.S.; Kim, K.H.; Son, D.J.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, D.Y.; et al. Cobrotoxin inhibits NF-kappa B activation and target gene expression through reaction with NF-kappa B signal molecules. Biochemistry. 2005, 44, 8326–8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Stoeva, S.; Schütz, J.; Kayed, R.; Abassi, A.; Zaidi, Z.H.; et al. Purification and primary structure of low molecular mass peptides from scorpion (Buthus sindicus) venom. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 1998, 121, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, E.; Brandtzaeg, O.K.; Vehus, T.; Roberg-Larsen, H.; Bogoeva, V.; Ademi, O.; et al. A critical evaluation of Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters for separating proteins, drugs and nanoparticles in biosamples. J. Pharm. Biomed. Analysis. 2016, 120, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, P.; Hansen, J.B.; Allen, M. Microvolume protein concentration determination using the NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer. J Vis Exp. 2009, 33, 1610. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical biochemistry. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.A.; Russo, R.C.; Thurston, R.V. Trimmed Spearman-Karber method for estimating median lethal concentrations in bioassays. Environ. Sci. & Technol. 1977, 11, 714–719. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council Steering Committee on Identification of TPTCfCbtNT, Program. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Toxicity Testing: Strategies to Determine Needs and Priorities. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 1984.

- Longhi-Balbinot, D.T.; Lanznaster, D.; Baggio, C.H.; Silva, M.D.; Cabrera, C.H.; Facundo, V.A.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of triterpene 3β, 6β, 16β-trihydroxylup-20(29)-ene obtained from Combretum leprosum Mart & Eich in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012, 142, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Montanher, A.; Zucolotto, S.; Schenkel, E.; Fröde, T. Evidence of anti-inflammatory effects of Passiflora edulis in an inflammation model. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007, 109, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, T.M.; Fiebig, R.; Corr, D.T.; Brickson, S.; Ji, L. Free radical activity, antioxidant enzyme, and glutathione changes with muscle stretch injury in rabbits. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985). 1999, 87, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.F.; Mao, Q.Q.; Ip, S.P.; Lin, Z.X.; Che, C.T. Comparison on the anti-inflammatory effect of Cortex Phellodendri Chinensis and Cortex Phellodendri Amurensis in 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate-induced ear edema in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizgerd, J.P.; Spieker, M.R.; Doerschuk, C.M. Early response cytokines and innate immunity: Essential roles for TNF receptor 1 and type I IL-1 receptor during Escherichia coli pneumonia in mice. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2001, 166, 4042–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, B.G. From genome to “venome”: Molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome research. 2005, 15, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, B.G.; Vidal, N.; Norman, J.A.; Vonk, F.J.; Scheib, H.; Ramjan, S.F.R.; et al. Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes. Nature. 2006, 439, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veterinary Pharmacology Toxicology Experiments [press release], Z. a.r.i.a.; , A.B.U. Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, J.J.; Sanz, L.; Angulo, Y.; Lomonte, B.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Venoms, venomics, antivenomics. FEBS letters. 2009, 583, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damotharan, P.; Veeruraj, A.; Arumugam, M.; Balasubramanian, T. Isolation and characterization of biologically active venom protein from sea snake Enhydrina schistosa. Journal of biochemical and molecular toxicology. 2015, 29, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samianifard, M.; Nazari, A.; Tahoori, F.; Mohamadpour Dounighi, N. Proteome Analysis of Toxic Fractions of Iranian Cobra (Naja naja Oxiana) Snake Venom Using Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis and Mass Spectrometry. Arch Razi Inst. 2021, 76, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- JM, W. The protein protocols handbook. New Jersey: Humana Press, 2002.

- Noble, J.E.; Bailey, M.J. Quantitation of protein. Methods in enzymology. 2009, 463, 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. Screening methods in pharmacology: Elsevier, 2013.

- Akhila, J.; Alwar, M. Acute toxicity studies and determination of median lethal dose. Curr Sci. 2007, 93, 917–920. [Google Scholar]

- Bickler, P.E. Amplification of Snake Venom Toxicity by Endogenous Signaling Pathways. Toxins (Basel). 2020, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.J.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Song, H.S.; Lee, C.K.; Hong, J.T. Therapeutic application of anti-arthritis, pain-releasing, and anti-cancer effects of bee venom and its constituent compounds. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2007, 115, 246–270. [Google Scholar]

- Farsky, S.H.; Antunes, E.; Mello, S.B. Pro and antiinflammatory properties of toxins from animal venoms. Current Drug Targets-Inflammation & Allergy. 2005, 4, 401–411. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, F.P.; Sampaio, S.C.; Santoro, M.L.; Sousa-e-Silva, M.C.C. Long-lasting anti-inflammatory properties of Crotalus durissus terrificus snake venom in mice. Toxicon. 2007, 49, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Mishra, R.; Gomes, A. Anti-arthritic activity of Indian monocellate cobra (Naja kaouthia) venom on adjuvant induced arthritis. Toxicon. 2010, 55, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Y-l Lin H-m Zou, R.; Wu J-c Han, R.; Raymond, L.N.; et al. Suppression of complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced adjuvant arthritis by cobratoxin. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2009, 30, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Robinson, S.E. The effect of cholinergic manipulations on the analgesic response to cobrotoxin in mice. Life sciences. 1990, 47, 1949–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang Y-x Jiang W-j Han L-p Zhao, S.-j. Peripheral and spinal antihyperalgesic activity of najanalgesin isolated from Naja naja atra in a rat experimental model of neuropathic pain. Neuroscience letters. 2009, 460, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, X.; Wong, P.; Gopalakrishnakone, P. A novel analgesic toxin (hannalgesin) from the venom of king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah). Toxicon. 1995, 33, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, L. Carrageenan paw edema in the mouse. Life Sciences. 1969, 8, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriques M, Silva P, Martins M, Flores C, Cunha F, Assreuy-Filho J; et al. Mouse paw edema. A new model for inflammation? Brazilian journal of medical and biological research= Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas. 1987, 20, 243–249.

- Posadas, I.; Bucci, M.; Roviezzo, F.; Rossi, A.; Parente, L.; Sautebin, L.; et al. Carrageenan-induced mouse paw oedema is biphasic, age-weight dependent and displays differential nitric oxide cyclooxygenase-2 expression. British journal of pharmacology. 2004, 142, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malech, H.L.; Gallin, J.I. Neutrophils in human diseases. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987, 317, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travaglia-Cardoso, S. Crotalus durissus terrificus - a case of xanthism. Herpetological Bulletin. 2006, 97, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, D.F.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Faquim-Mauro, E.L.; Macedo, M.S.; Farsky, S.H. Role of crotoxin, a phospholipase A2 isolated from Crotalus durissus terrificus snake venom, on inflammatory and immune reactions. Mediators of inflamm. 2001, 10, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.A.H.; Pazin, W.M.; Dreyer, T.R.; Bicev, R.N.; Cavalcante, W.L.G.; Fortes-Dias, C.L.; et al. Biophysical studies suggest a new structural arrangement of crotoxin and provide insights into its toxic mechanism. Scientific Reports. 2017, 7, 43885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.C.; Gonçalves, L.R.; Mariano, M. The venom of South American rattlesnakes inhibits macrophage functions and is endowed with anti-inflammatory properties. Mediators of inflamm. 1996, 5, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.; Sousa-e-Silva, M.; Borelli, P.; Curi, R.; Cury, Y. Crotalus durissus terrificus snake venom regulates macrophage metabolism and function. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2001, 70, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.; Guo, J. Anti-inflammatory effects of Neurotoxin-Nna, a peptide separated from the venom of Naja naja atra. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Saha, P.P.; Bhowmik, T.; Dasgupta, A.K.; Dasgupta, S.C. Protection against osteoarthritis in experimental animals by nanogold conjugated snake venom protein toxin gold nanoparticle-Naja kaouthia cytotoxin The Indian journal of medical research. 2016, 144, 910–917. 144.

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S.NO. | Groups | Protein Concentration in a Sample (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1- | Total Pooled Venom | 110 |

| 2- | Crude Venom (Diluted 10x) | 9.8 |

| 3- | Fraction-1 | 90.3 |

| 4- | Fraction-2 | 0.81 |

| 5- | Standard (BSA) | 2 |

| Groups | Dose (µg/Kg) | Dose difference (a) | No. of animals (n=8) | No. of Death | Mean Mortality (b) | Product (a X b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 27 | - | 8 | 1 | - | - |

| 2. | 30 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| 3. | 33 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 2.5 | 7.5 |

| 4. | 40 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 5.5 | 38.5 |

| 5. | 47 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 56 |

| 6. | 50 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| 7. | 53 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 24 |

| ∑= 154.5 |

| Groups | Dose (µg/Kg) | Dose difference (a) | No. of animals (n=8) | No. of Death | Mean Mortality (b) | Product (a X b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 5 | - | 8 | 2 | - | - |

| 2. | 6 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 3. | 7.3 | 1.3 | 8 | 4 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

| 4. | 8.3 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 5. | 13.2 | 4.9 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 34.3 |

| 6. | 15 | 1.8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 14.4 |

| 7. | 17 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| 8. | 21 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 32 |

| 9. | 30 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 72 |

| ∑= 180.8 |

| Groups | Dose (µg/Kg) | Dose difference (a) | No. of animals (n=8) | No. of Death | Mean Mortality (b) | Product (a X b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 333 | - | 8 | 4 | - | - |

| 2. | 500 | 167 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 835 |

| 3. | 667 | 167 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 1169 |

| 4. | 1000 | 333 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2664 |

| 5. | 1333 | 333 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2664 |

| 6. | 1667 | 334 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2672 |

| 7. | 2000 | 333 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2664 |

| 8. | 2666 | 666 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5328 |

| ∑= 17996 |

| S.No# | Groups | Body weight (gm.) (n=5) | Dose (ug/kg) | Mortality (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Crude Venom | 23.5 ± 0.5 | 27 | 1/5 |

| 24.3 ± 0.5 | 25.5 | 0/5 | ||

| 25.5 ± 0.4 | 19 | 0/5 | ||

| 2. | Fraction-1 | 22 ± 0.6 | 9.5 | 0/5 |

| 25.7 ± 0.6 | 8.3 | 3/5 | ||

| 26.6 ± 0.7 | 6 | 2/5 | ||

| 28.4 ± 0.3 | 5 | 1/5 | ||

| 27.6 ± 0.2 | 3.7 | 0/5 | ||

| 3. | Fraction-2 | 24.5 ± 0.6 | 500 | 3/5 |

| 22.5 ± 0.5 | 333 | 1/5 | ||

| 24.5 ± 0.5 | 267 | 0/5 | ||

| 25.2 ± 0.5 | 200 | 0/5 | ||

| 4. | Control | 25 ± 0.6 | 0.1mL N/S | 0/5 |

| CBC Profile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.NO | Groups | Hb (g/dl) | RBC (10e12/L) | WBC (10e9/L) | PLT (10e9L) |

| 1. | Crude (27 µg/kg) | 13.2 ± 0.38*** | 8.2 ± 0.35** | 3.2 ± 0.38ns | 486.3 ± 3.17ns |

| 2. | Fraction-1 (5 µg/kg) | 21.1 ± 0.43*** | 13.3 ± 0.32*** | 15.1 ± 0.17*** | 600 ± 3.46** |

| 3. | Fraction-2 (333 µg/kg) | 13.1 ± 0.31*** | 8.7 ± 0.17** | 11.6 ± 0.34*** | 654.7 ± 22.6*** |

| 4. | Control | 7.8 ± 0.37 | 5.2 ± 0.63 | 3.7 ± 0.32 | 507 ± 6.35 |

| Biochemical Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.NO | Groups | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | Cr. (mg/dl/l) | BUN (mg/dl) |

| 1. | Crude (27ug/kg) | 640.7 ± 2.6*** | 46 ± 1.7ns | 0.45 ± 0.03ns | 9.4 ± 0.17ns |

| 2. | Fraction-1 (5ug/kg) | 762.7 ± 2.3*** | 83 ± 1.1*** | 0.51 ± 0.03* | 15.4 ± 0.32*** |

| 3. | Fraction-2 (333ug/kg) | 462 ± 3.9*** | 68.7 ± 1.4*** | 0.47 ± 0.02ns | 14.4 ± 0.12*** |

| 4. | Control | 387.6 ± 7.5 | 52.7 ± 2.6 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 9.1 ± 0.11 |

| S.No# | Groups | Body weight (gm.) | Dose (ug/kg) | Mortality (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Crude Venom | 24.3 ± 0.5 | 25.5 | 3/5 |

| 25.5 ± 0.6 | 19 | 0/5 | ||

| 22 ± 0.5 | 9.5 | 0/5 | ||

| 2. | Fraction-1 | 28.4 ± 0.4 | 5 | 4/5 |

| 27.6 ± 0.3 | 3.7 | 3/5 | ||

| 26.9 ± 0.2 | 1.8 | 0/5 | ||

| 3. | Fraction-2 | 22.5 ± 0.9 | 333 | 3/5 |

| 24.5 ± 0.5 | 267 | 0/5 | ||

| 25.2 ± 0.6 | 200 | 0/5 | ||

| 4. | Control | 25 ± 0.7 | 0.1 mL N/S | 0/5 |

| CBC Profile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.NO | Groups | Hb (g/dl) | RBC (10e12/L) | WBC (10e9/L) | PLT (10e9/L) |

| 1. | Crude (19 µg/kg) | 12.8 ± 0.20** | 8.6 ± 0.51* | 13.7 ± 0.26*** | 654.7 ±33* |

| 2. | Fraction-1 (1.8 µg/kg) | 22.8 ± 0.14*** | 17 ± 0.17*** | 16.3 ± 0.26*** | 715 ± 39 ** |

| 3. | Fraction-2 (267 µg/kg) | 8.8 ± 2.0ns | 6.6 ± 0.76ns | 11.9 ± 0.29*** | 793 ± 9.41*** |

| 4. | Control | 8.5 ± 0.17 | 5.87 ± 0.52 | 4.6 ± 0.56 | 487.7 ± 41 |

| Biochemical Parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.NO | Groups | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | Creatinine (mg/dl/l) | BUN (mg/dl) |

| 1. | Crude (19ug/kg) | 749 ± 10.6*** | 84 ± 2.11*** | 0.38 ± 0.01ns | 8.3 ± 0.11*** |

| 2. | Fraction-1 (1.8ug/kg) | 277.3 ± 5.4*** | 56.3 ± 0.90ns | 0.44 ± 0.01ns | 10.5 ± 0.11** |

| 3. | Fraction-2 (267ug/kg) | 642.6 ± 4.6*** | 92 ± 1.73*** | 0.41 ± 0.01ns | 8.43 ± 0.09*** |

| 4. | Control | 394.3 ± 4.8 | 55.7 ± 2.40 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 9.7 ± 0.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).