Submitted:

11 March 2024

Posted:

11 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

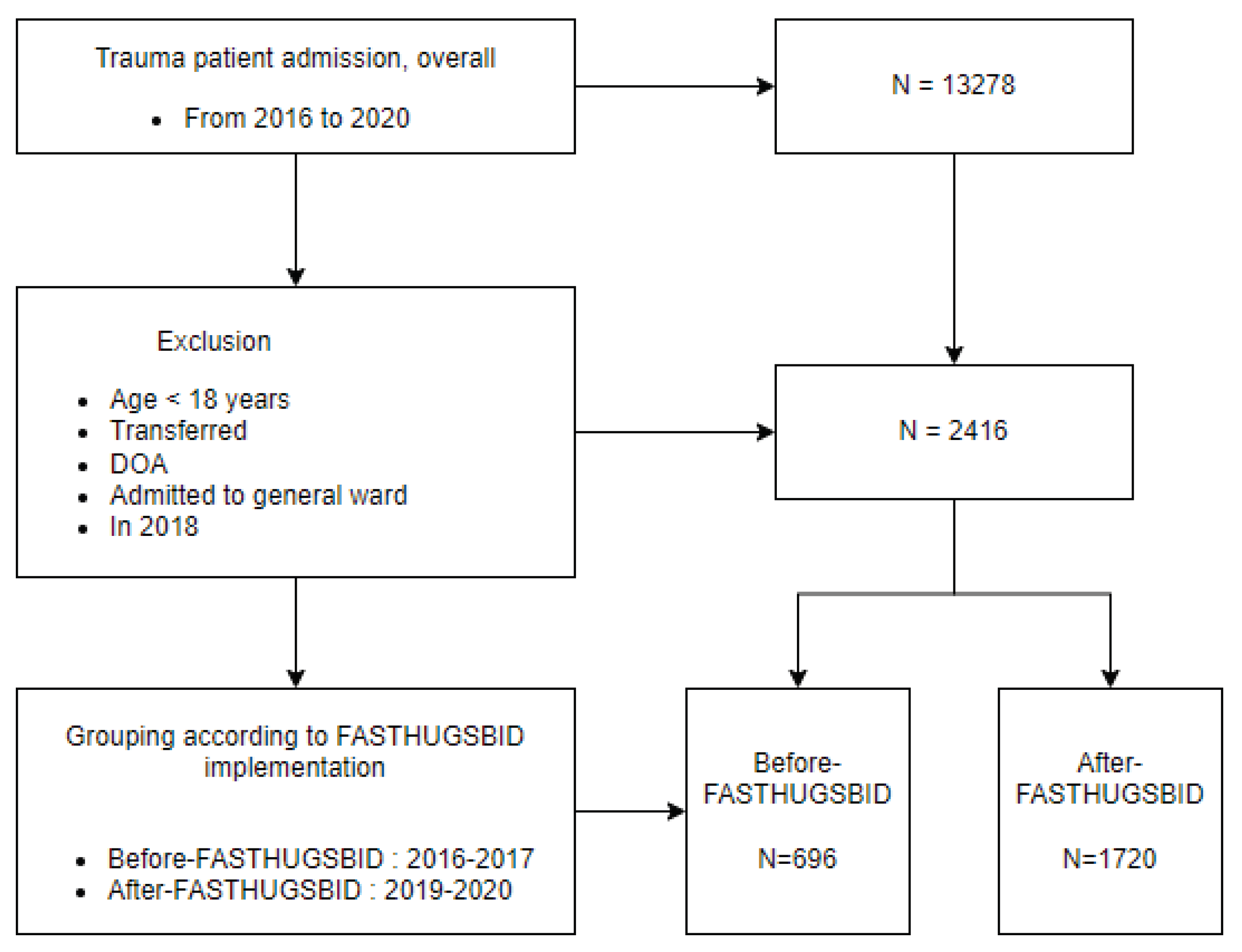

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Procedure

2.2. Definition and Study Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients

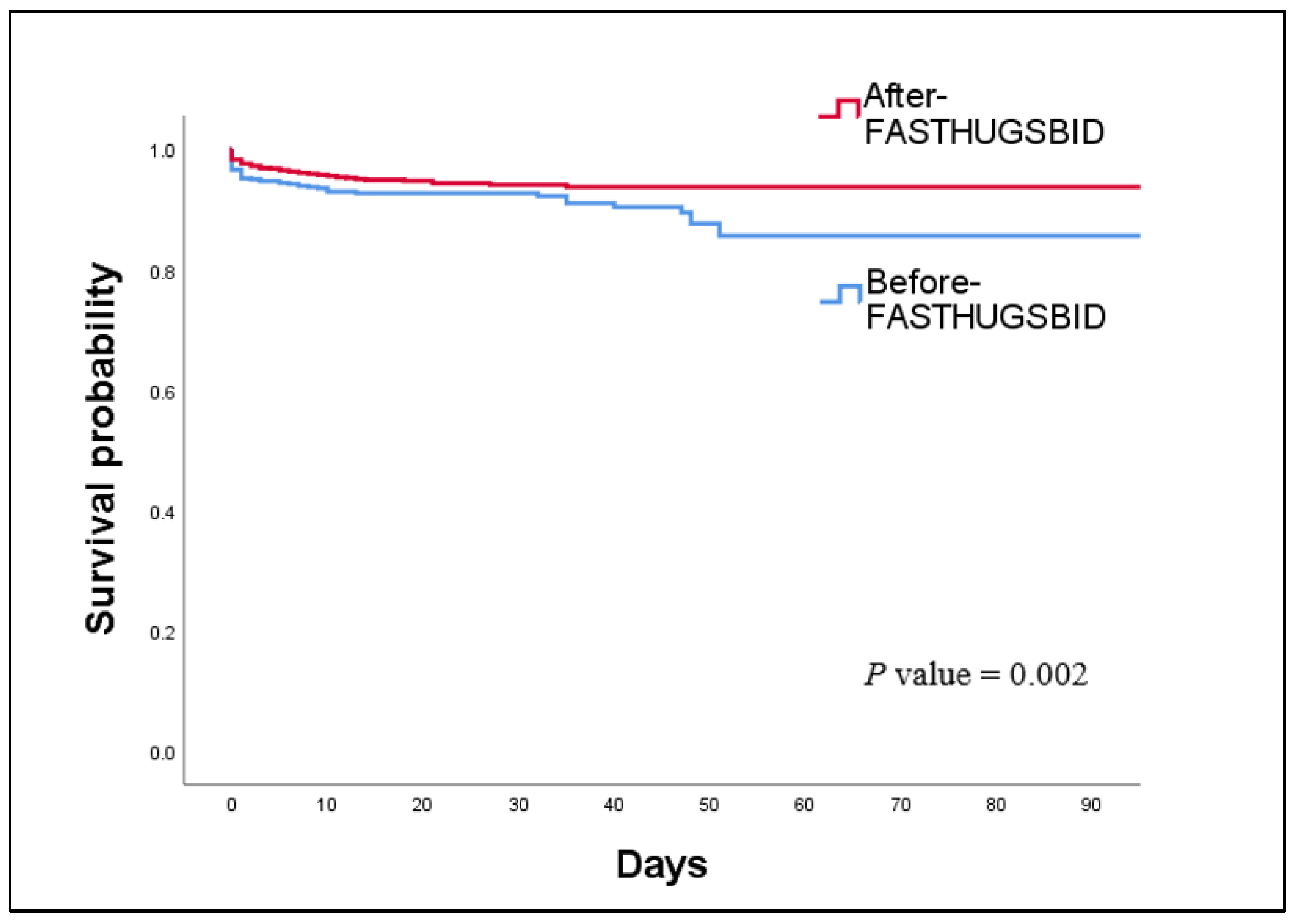

3.2. Primary Outcomes

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

3.4. Comparisons of Each Component of the FAST HUGS BID Checklist

3.5. Factors Associated with In-hospital Mortality and LOS in the ICU and Hospital

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gruen, R.L.; Jurkovich, G.J.; McIntyre, L.K.; Foy, H.M.; Maier, R.V. Patterns of errors contributing to trauma mortality: Lessons learned from 2,594 deaths. Ann Surg. 2006, 244, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michetti, C.P.; Fakhry, S.M.; Brasel, K.; Martin, N.D.; Teicher, E.J.; Newcomb, A. Trauma ICU Prevalence Project: The diversity of surgical critical care. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2019, 4, e000288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C.D.; Brunetti, L.; Davidov, L.; Mujia, J.; Rodricks, M. The impact of intensive care unit physician staffing change at a community hospital. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121211066471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, G.; Zieleskiewicz, L.; Antonini, F.; Mokart, D.; Paone, V.; Po, M.H.; Vigne, C.; Hammad, E.; Potié, F.; Martin, C.; Medam, S.; Leone, M. Implementation of an electronic checklist in the ICU: Association with improved outcomes. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018, 37, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronovost, P.J.; Young, T.L.; Dorman, T.; Robinson, K.; Angus, D.C. Association between icu physician staffing and outcomes: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 1999, 27, A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K.; Palileo, A.; Schulman, C.I.; Wilson, K.; Augenstein, J.; Kiffin, C.; McKenney, M. Enhancing patient safety in the trauma/surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2009, 67, 430–433, discussion 3-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, M.C.; Schuerer, D.J.; Schallom, M.E.; Sona, C.S.; Mazuski, J.E.; Taylor, B.E.; McKenzie, W.; Thomas, J.M.; Emerson, J.S.; Nemeth, J.L.; Bailey, R.A.; Boyle, W.A.; Buchman, T.G.; Coopersmith, C.M. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensive care unit practices. Crit Care Med. 2009, 37, 2775–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L. Give your patient a fast hug (at least) once a day. Crit Care Med. 2005, 33, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W.R., 3rd; Hatton, K.W. Critically ill patients need "FAST HUGS BID" (an updated mnemonic). Crit Care Med. 2009, 37, 2326–2327, author reply 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, R.A.; Chatkin, J.M. Impact of a multidisciplinary checklist on the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation and length of ICU stay. J Bras Pneumol. 2020, 46, e20180261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronovost, P.; Needham, D.; Berenholtz, S.; Sinopoli, D.; Chu, H.; Cosgrove, S.; Sexton, B.; Hyzy, R.; Welsh, R.; Roth, G.; Bander, J.; Kepros, J.; Goeschel, C. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355, 2725–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubose, J.; Teixeira, P.G.; Inaba, K.; Lam, L.; Talving, P.; Putty, B.; Plurad, D.; Green, D.J.; Demetriades, D.; Belzberg, H. Measurable outcomes of quality improvement using a daily quality rounds checklist: One-year analysis in a trauma intensive care unit with sustained ventilator-associated pneumonia reduction. J Trauma. 2010, 69, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.R.; de Souza, D.F.; Cunha, T.M.; Tavares, M.; Reis, S.S.; Pedroso, R.S.; de Brito Röder, D.V.D. The effectiveness of a bundle in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Braz J Infect Dis. 2016, 20, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, A.B.; Weiser, T.G.; Berry, W.R.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Breizat, A.H.; Dellinger, E.P.; Herbosa, T.; Joseph, S.; Kibatala, P.L.; Lapitan, M.C.; Merry, A.F.; Moorthy, K.; Reznick, R.K.; Taylor, B.; Gawande, A.A. ; Safe Surgery Saves Lives Study Group. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Writing Group for the CHECKLIST-ICU Investigators and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet); Cavalcanti, A.B.; Bozza, F.A.; Machado, F.R.; Salluh, J.I.; Campagnucci, V.P.; Vendramim, P.; Guimaraes, H.P.; Normilio-Silva, K.; Damiani, L.P.; Romano, E.; Carrara, F.; Lubarino Diniz de Souza, J.; Silva, A.R.; Ramos, G.V.; Teixeira, C.; Brandão da Silva, N.; Chang, C.C.; Angus, D.C.; Berwanger, O. Effect of a quality improvement intervention with daily round checklists, goal setting, and clinician prompting on mortality of critically ill patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016, 315, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Studley, H.O. Percentage of weight loss: Basic indicator of surgical risk in patients with chronic peptic ulcer. JAMA. 1936, 106, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Reyes, L.; Patel, J.J.; Jiang, X.; Coz Yataco, A.; Day, A.G.; Shah, F.; Zelten, J.; Tamae-Kakazu, M.; Rice, T.; Heyland, D.K. Early versus delayed enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients with circulatory shock: A nested cohort analysis of an international multicenter, pragmatic clinical trial. Crit Care. 2022, 26, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, M.; Laviano, A.; Meguid, M.M.; Gleason, J.R. In 1995 a correlation between malnutrition and poor outcome in critically ill patients still exists. Nutrition. 1996, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.L. Nutritional requirements of surgical and critically-ill patients: Do we really know what they need? Proc Nutr Soc. 2004, 63, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puntillo, K.A.; White, C.; Morris, A.B.; Perdue, S.T.; Stanik-Hutt, J.; Thompson, C.L.; Wild, L.R. Patients' perceptions and responses to procedural pain: Results from Thunder Project II. Am J Crit Care. 2001, 10, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Turner, J.A.; Devine, E.B.; Hansen, R.N.; Sullivan, S.D.; Blazina, I.; Dana, T.; Bougatsos, C.; Deyo, R.A. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A Systematic Review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015, 162, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, P.; Chauvin, M.; Verleye, M. Nefopam analgesia and its role in multimodal analgesia: A review of preclinical and clinical studies. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016, 43, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, B.L.; Myburgh, J.A.; Scott, D.A. The complications of opioid use during and post-intensive care admission: A narrative review. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2022, 50, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, G.L.; Devlin, J.W.; Worby, C.P.; Alhazzani, W.; Barr, J.; Dasta, J.F.; Kress, J.P.; Davidson, J.E.; Spencer, F.A. Benzodiazepine versus nonbenzodiazepine-based sedation for mechanically ventilated, critically ill adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care Med. 2013, 41 Suppl 1, S30–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, S.M.; Ruokonen, E.; Grounds, R.M.; Sarapohja, T.; Garratt, C.; Pocock, S.J.; Bratty, J.R.; Takala, J. Dexmedetomidine for Long-Term Sedation Investigators. Dexmedetomidine vs Midazolam or Propofol for Sedation During Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: Two Randomized Controlled Trials. JAMA. 2012, 307, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, D.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; D'Amours, S.; Hameed, S.M.; Beveridge, J.; Ball, C.G. A Prospective Evaluation of the Utility of a Hybrid Operating Suite for Severely Injured Patients: Overstated or Underutilized? Ann Surg. 2020, 271, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorkgitis, B.K.; Berndtson, A.E.; Cross, A.; Kennedy, R.; Kochuba, M.P.; Tignanelli, C.; Tominaga, G.T.; Jacobs, D.G.; Marx, W.H.; Ashley, D.W.; Ley, E.J.; Napolitano, L.; Costantini, T.W. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma/American College of Surgeons-Committee on Trauma Clinical Protocol for inpatient venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022, 92, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, A.; Serra-Batlles, J.; Ros, E.; Piera, C.; Puig de la Bellacasa, J.; Cobos, A.; Lomeña, F.; Rodríguez-Roisin, R. Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in patients receiving mechanical ventilation: The effect of body position. Ann Intern Med. 1992, 116, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Tang, X.; Yuan, Q.; Deng, L.; Sun, X. Semi-recumbent position versus supine position for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults requiring mechanical ventilation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016, 2016, Cd009946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, L. Reducing the risk of ventilator-acquired pneumonia through head of bed elevation. Nurs Crit Care. 2007, 12, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quenot, J.P.; Thiery, N.; Barbar, S. When should stress ulcer prophylaxis be used in the ICU? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009, 15, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbateskovic, M.; Marker, S.; Jakobsen, J.C.; Krag, M.; Granholm, A.; Anthon, C.T.; Perner, A.; Wetterslev, J.; Møller, M.H. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in adult intensive care unit patients - a protocol for a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018, 62, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, M.; Bass, S.; Chaisson, N.F. Which ICU patients need stress ulcer prophylaxis? Cleve Clin J Med. 2022, 89, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.Q.; Ren, C.; Wu, G.S.; Zhu, Y.B.; Xia, Z.F.; Yao, Y.M. Is intensive glucose control bad for critically ill patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Biol Sci. 2020, 16, 1658–1675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girard, T.D.; Kress, J.P.; Fuchs, B.D.; Thomason, J.W.; Schweickert, W.D.; Pun, B.T.; Taichman, D.B.; Dunn, J.G.; Pohlman, A.S.; Kinniry, P.A.; Jackson, J.C.; Canonico, A.E.; Light, R.W.; Shintani, A.K.; Thompson, J.L.; Gordon, S.M.; Hall, J.B.; Dittus, R.S.; Bernard, G.R.; Ely, E.W. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008, 371, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, T.E.; Sona, C.; Schallom, L.; Buckles, M.; Cracchiolo, L.; Schuerer, D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Song, F.; Buchman, T.G. Improved extubation rates and earlier liberation from mechanical ventilation with implementation of a daily spontaneous-breathing trial protocol. J Am Coll Surg. 2008, 206, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krinsley, J.S.; Reddy, P.K.; Iqbal, A. What is the optimal rate of failed extubation? Crit Care. 2012, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taito, S.; Kawai, Y.; Liu, K.; Ariie, T.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Banno, M.; Kataoka, Y. Diarrhea and patient outcomes in the intensive care unit: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2019, 53, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.; O'Grady, N.P. Prevention of central line-associated bloodstream infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017, 31, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Chen, H. Interventions to reduce unnecessary central venous catheter use to prevent central-line-associated bloodstream infections in adults: A systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 1442–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.; Hall, C.L.; Wiley, Z.; Tejedor, S.C.; Kim, J.S.; Reif, L.; Witt, L.; Jacob, J.T. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adults: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Hosp Med. 2020, 15, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nollen, J.M.; Pijnappel, L.; Schoones, J.W.; Peul, W.C.; Van Furth, W.R.; Brunsveld-Reinders, A.H. Impact of early postoperative indwelling urinary catheter removal: A systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2023, 32, 2155–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masterton, R.G. Antibiotic de-escalation. Crit Care Clin. 2011, 27, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohji, G.; Doi, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Iwata, K. Is de-escalation of antimicrobials effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2016, 49, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Before-FD1 (n=696) | After-FD2 (n=1720) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), mean ± SD3 | 48.7 ± 17.5 | 48.7 ± 16.8 | 0.97 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.09 | ||

| Female | 171 (24.6) | 368 (21.4) | |

| Male | 525 (75.4) | 1352 (78.6) | |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.539 | ||

| Blunt, n (%) | 618 (89.3) | 1545 (90.1) | |

| Penetrating, n (%) | 74 (10.7) | 169 (9.9) | |

| Underlying disease, yes (%) | 263 (38.3) | 734 (42.9) | <0.05 |

| Injury Severity Score, median (IQR4) | 13 (5-22) | 17 (10-24) | <0.05 |

| Initial physiologic parameters | |||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean ± SD | 131.2 ± 26.9 | 136.0 ± 26.7 | <0.05 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean ± SD | 82.2 ± 20.9 | 89.2 ± 21.1 | <0.05 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg), mean ± SD | 98.5 ± 21.4 | 104.8 ± 21.2 | <0.05 |

| Pulse rate (per min), mean ± SD | 90.7 ± 19.9 | 89.2 ± 20.4 | 0.09 |

| Respiratory rate (per min), mean ± SD | 20.4 ± 5.8 | 21.1 ± 5.9 | <0.05 |

| Body temperature (℃), mean ± SD | 36.4 ± 0.7 | 36.5 ± 0.7 | 0.25 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale, median (IQR) | 15 (13-15) | 15 (14-15) | 0.07 |

| Primary outcomes | Before-FD1 (n=696) | After-FD2 (n=1720) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 58 (8.3) | 83 (4.8) | <0.05 |

| Complications, n (%) | 160 (23.0) | 283 (16.5) | <0.05 |

| ICU3 length of stay (days), mean ± SD | 7.8 ± 13.3 | 5.1 ± 10.4 | <0.05 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), mean ± SD | 24.3 ± 24.6 | 17.6 ± 16.0 | <0.05 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days), mean ± SD | 9.2 ± 13.3 (n=315) | 5.0 ± 8.4 (n=682) | <0.05 |

| Complications | Before-FD1 (n=696) | After-FD2 (n=1720) | P values | OR3 (95% CI4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 160 (23) | 283 (16.5) | <0.05 | 0.66 (0.53-0.82) |

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 9 (1.3) | 26 (1.5) | 0.68 | 1.17 (0.54-2.51) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 4 (0.6) | 9 (0.5) | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.28-2.97) |

| Pressure ulcer, n (%) | 76 (10.9) | 98 (5.7) | <0.05 | 0.49 (0.36-0.67) |

| Venous thromboembolism, n (%) | 8 (1.1) | 24 (1.4) | 0.63 | 1.21 (0.54-2.72) |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 63 (9.1) | 59 (3.4) | <0.05 | 0.38 (0.25-0.52) |

| Surgical site infection, n (%) | 30 (4.3) | 23 (1.3) | <0.05 | 0.30 (0.17-0.52) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 8 (1.1) | 18 (1.0) | 0.82 | 0.91 (0.39-2.10) |

| Catheter related blood stream infection, n (%) | 2 (0.3) | 9 (0.5) | 0.74 | 1.83 (0.39-8.47) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 3 (0.4) | 25 (1.5) | <0.05 | 3.40 (1.02-11.32) |

| Component of FAST HUGS BID checklist | Before-FD1 (n=696) |

After-FD2 (n=1720) |

P values | OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding | ||||

| Time to enteral nutrition (days), mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 3.7 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | <0.05 | - |

| Time to parenteral nutrition (days), mean ± SD | 7.9 ± 8.9 (n=161) | 9.2 ± 9.5 (n=209) | 0.165 | - |

| Body weight difference (kg), mean ± SD | 0.46 ± 6.3 | 0.52 ± 3.9 | <0.05 | - |

| Analgesia | ||||

| IV3 Fentanyl use, n (%) | 508 (73.0) | 1225 (71.2) | 0.382 | 0.91 (0.75-1.11) |

| Duration of IV Fentanyl use (days), mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 7.6 (n=508) | 2.5 ± 2.9 (n=1225) | <0.05 | - |

| IV Nefopam use, n (%) | 421 (60.5) | 1407 (81.8) | <0.05 | 2.94 (2.41-3.57) |

| PO4 painkillers use, n (%) | 456 (65.5) | 1382 (80.3) | <0.05 | 2.15 (1.77-2.61) |

| PO opioids use, n (%) | 72 (10.3) | 654 (38.0) | <0.05 | 5.31 (4.09-6.91) |

| TD5 Fentanyl patch use, n (%) | 196 (28.2) | 550 (32.0) | 0.66 | 1.20 (0.99-1.46) |

| Pain scale, median (IQR) | 1 (0.1-2.0) | 1.2 (0.5-2.1) | <0.05 | - |

| Sedation | ||||

| IV Midazolam use, n (%) | 201 (28.9) | 113 (6.6) | <0.05 | 0.17 (0.13-0.22) |

| IV Propofol use, n (%) | 205 (29.5) | 434 (25.2) | <0.05 | 0.80 (0.66-0.98) |

| IV Dexmedetomidine use, n (%) | 138 (19.8) | 452 (26.3) | <0.05 | 1.44 (1.16-1.79) |

| IV Vecuronium use, n (%) | 69 (9.9) | 83 (4.8) | <0.05 | 0.46 (0.33-0.64) |

| RASS6 score, median (IQR) | -0.4 (-1.5-0.0) | -0.3 (-1.0-0.0) | <0.05 | - |

| Thromboembolic prophylaxis | ||||

| SC7 LMWH use, n (%) | 165 (23.7) | 690 (40.1) | <0.05 | 2.16 (1.77-2.63) |

| Time to the first use of LMWH8 (days), mean ± SD | 4.8 ± 4.8 (n=165) | 2.8 ± 2.8 (n=690) | <0.05 | - |

| Head of bed elevation | ||||

| Time to first head of bed elevation (days), mean ± SD | 8.8 ± 16.8 | 4.8 ± 12.0 | <0.05 | - |

| Ulcer prophylaxis | ||||

| H2-blocker use, n (%) | 640 (92.0) | 1476 (85.8) | <0.05 | 0.53 (0.39-0.72) |

| Proton pump inhibitor use, n (%) | 64 (9.2) | 86 (5.0) | <0.05 | 0.52 (0.37-0.72) |

| Glycemic control | ||||

| Average level of blood sugar (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 137.1 ± 32.6 | 134.5 ± 31.3 | 0.07 | - |

| Hypoglycemic event, n (%) | 29 (4.2) | 67 (3.9) | 0.76 | 0.93 (0.59-1.46) |

| Spontaneous breathing trial | ||||

| Time to extubation (days), mean ± SD | 6.4 ± 7.2 (n=308) | 4.8 ± 5.5 (n=594) | <0.05 | - |

| Unplanned intubation, n (%) | 6 (0.9) | 37 (2.2) | <0.05 | 2.53 (1.06-6.02) |

| Bowel movement | ||||

| Diarrhea event, n (%) | 142 (20.4) | 277 (16.1) | <0.05 | 0.75 (0.60-0.94) |

| Vomiting event, n (%) | 108 (15.5) | 242 (14.1) | 0.36 | 0.89 (0.70-1.14) |

| Indwelling catheter | ||||

| Time to removal of CVC9 (days), mean ± SD | 11.9 ± 16.5 | 7.6 ± 11.0 | <0.05 | - |

| Time to removal of urinary catheter (days), mean ± SD | 8.5 ± 16.3 | 5.8 ± 12.5 | <0.05 | - |

| Drug de-escalation | ||||

| Restricted antimicrobials use, n (%) | 175 (25.1) | 333 (19.4) | <0.05 | 0.71 (0.58-0.88) |

| Duration of antimicrobials use (days), mean ± SD | 18.0 ± 22.1 | 8.2 ± 13.6 | <0.05 | - |

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | P values | Adjusted OR | P values | |

| Age | 1.018 | <0.001 | 1.040 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.864 | 0.499 | ||

| Mechanism of injury | 0.601 | 0.148 | ||

| Underlying disease | 0.933 | 0.713 | ||

| Initial systolic blood pressure | 0.985 | <0.001 | 0.898 | 0.538 |

| Initial diastolic blood pressure | 0.976 | <0.001 | 0.764 | 0.441 |

| Initial mean arterial pressure | 0.977 | <0.001 | 1.445 | 0.482 |

| Initial pulse rate | 1.025 | <0.001 | 1.010 | 0.103 |

| Initial respiratory rate | 1.019 | 0.244 | ||

| Initial body temperature | 0.458 | <0.001 | 1.048 | 0.789 |

| Initial Glasgow Coma Scale | 0.673 | <0.001 | 0.748 | <0.001 |

| Injury Severity Score | 1.088 | <0.001 | 1.066 | <0.001 |

| FAST HUGS BID | 0.551 | 0.001 | 0.434 | 0.008 |

| Complications | 4.215 | <0.001 | 2.080 | 0.016 |

| Nagelkerke =0.450 Hosmer-Lemeshow Chi-square test = 9.753, df= 8, P value =0.283 | ||||

| Variables | β1 | 95% CI2 | Βeta3 | P value |

| Mechanism of injury | 0.502 | -0.840~1.843 | 0.014 | 0.464 |

| Underlying disease | 0.897 | 0.102-1.691 | 0.042 | 0.027 |

| Initial systolic blood pressure | -0.409 | -0.887~0.069 | -1.018 | 0.094 |

| Initial diastolic blood pressure | -0.791 | -1.747~0.164 | -1.566 | 0.104 |

| Initial mean arterial pressure | 1.203 | -0.229~2.636 | 2.385 | 0.100 |

| Initial pulse rate | 0.015 | -0.008~0.037 | 0.027 | 0.202 |

| Initial respiratory rate | 0.003 | -0.069~0.076 | 0.002 | 0.934 |

| Initial body temperature | -0.335 | -0.923~0.254 | -0.022 | 0.265 |

| Initial Glasgow Coma Scale | -0.682 | -0.841~-0.522 | -0.171 | <0.001 |

| Injury Severity Score | 0.194 | 0.150~0.238 | 0.196 | <0.001 |

| FAST HUGS BID | -2.742 | -3.645~-1.839 | -0.118 | <0.001 |

| Complications | 8.212 | 7.049~9.374 | 0.285 | <0.001 |

| R= 0.500, =0.25, adj.=0.246 | ||||

| Variables | β | 95%CI | βeta | P value |

| Initial systolic blood pressure | -40.431 | -124.612~43.749 | -0.597 | 0.346 |

| Initial diastolic blood pressure | -97.933 | -266.144~70.278 | -1.144 | 0.254 |

| Initial mean arterial pressure | 135.708 | -116.528~387.944 | 1.597 | 0.292 |

| Initial pulse rate | -0.534 | -4.176~3.108 | -0.006 | 0.774 |

| Initial body temperature | 58.948 | -42.239~160.135 | 0.023 | 0.253 |

| Initial Glasgow Coma Scale | -189.064 | -214.394~-163.734 | -0.309 | <0.001 |

| Injury Severity Score | 28.164 | 20.962~35.367 | 0.175 | <0.001 |

| FASTHUGSBID | -251.928 | -409.369~-94.487 | -0.063 | 0.002 |

| Complications | 398.987 | 200.615~597.359 | 0.083 | <0.001 |

| R= 0.430, =0.185, adj.=0.182 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).