Submitted:

05 March 2024

Posted:

06 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

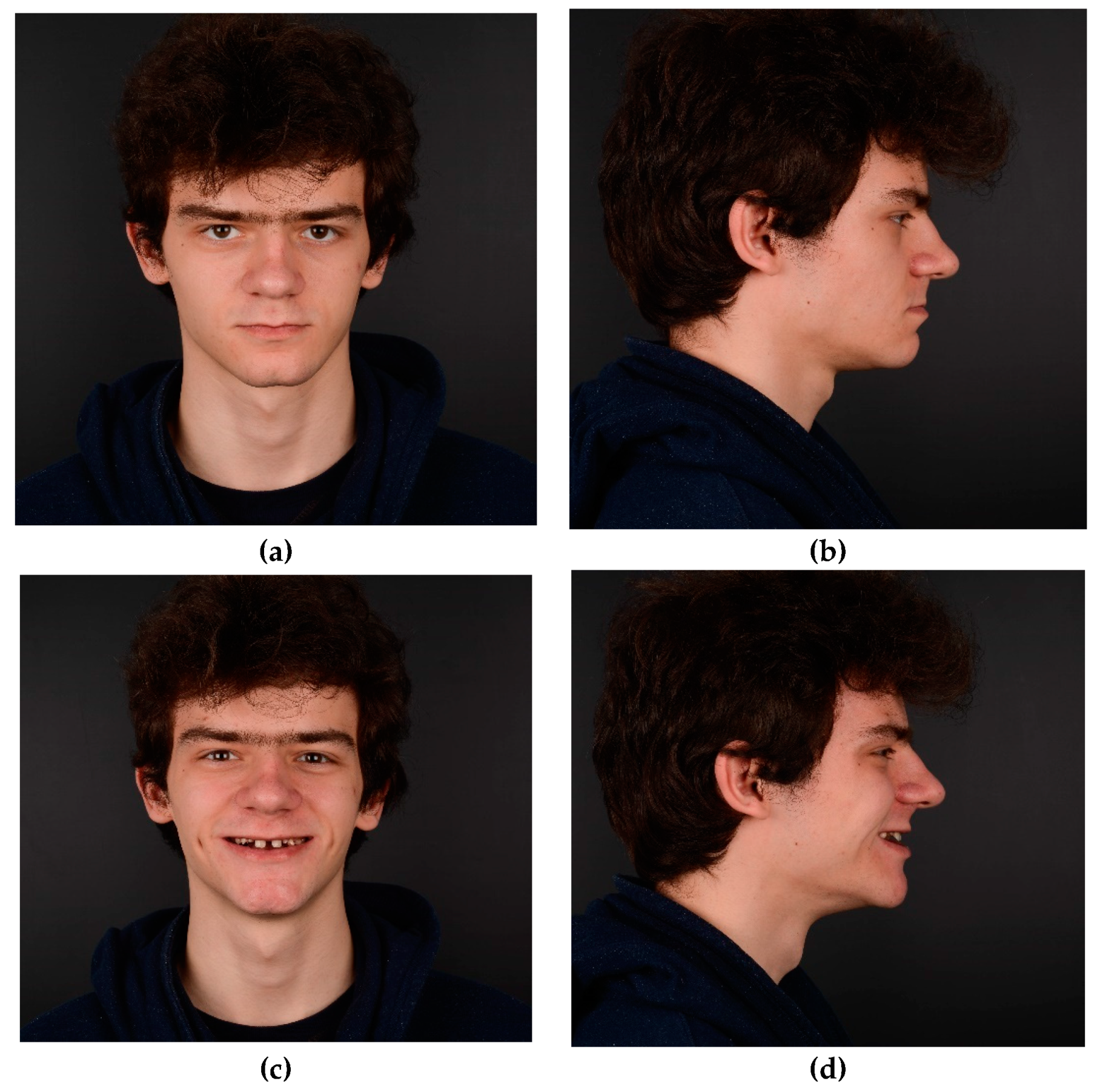

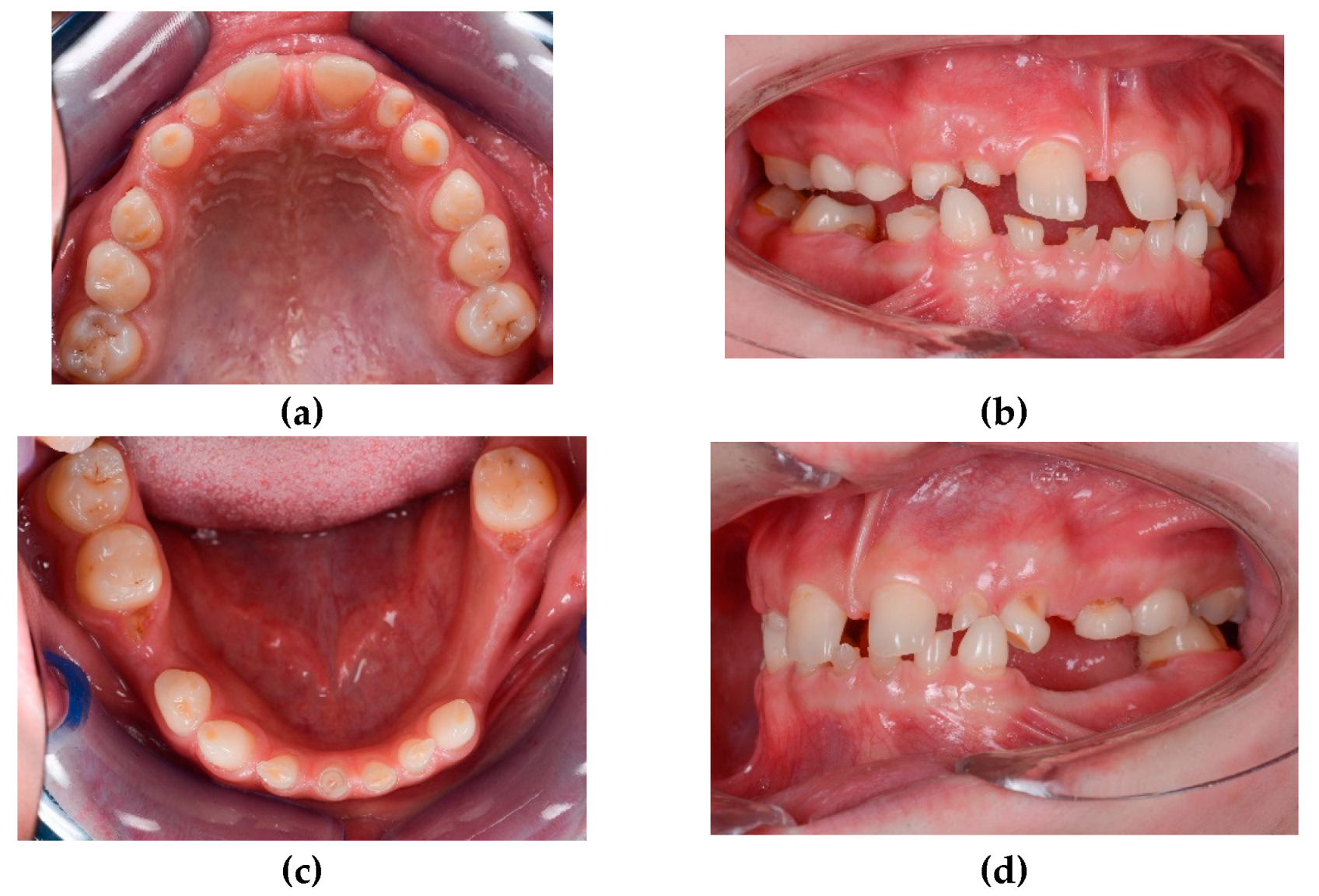

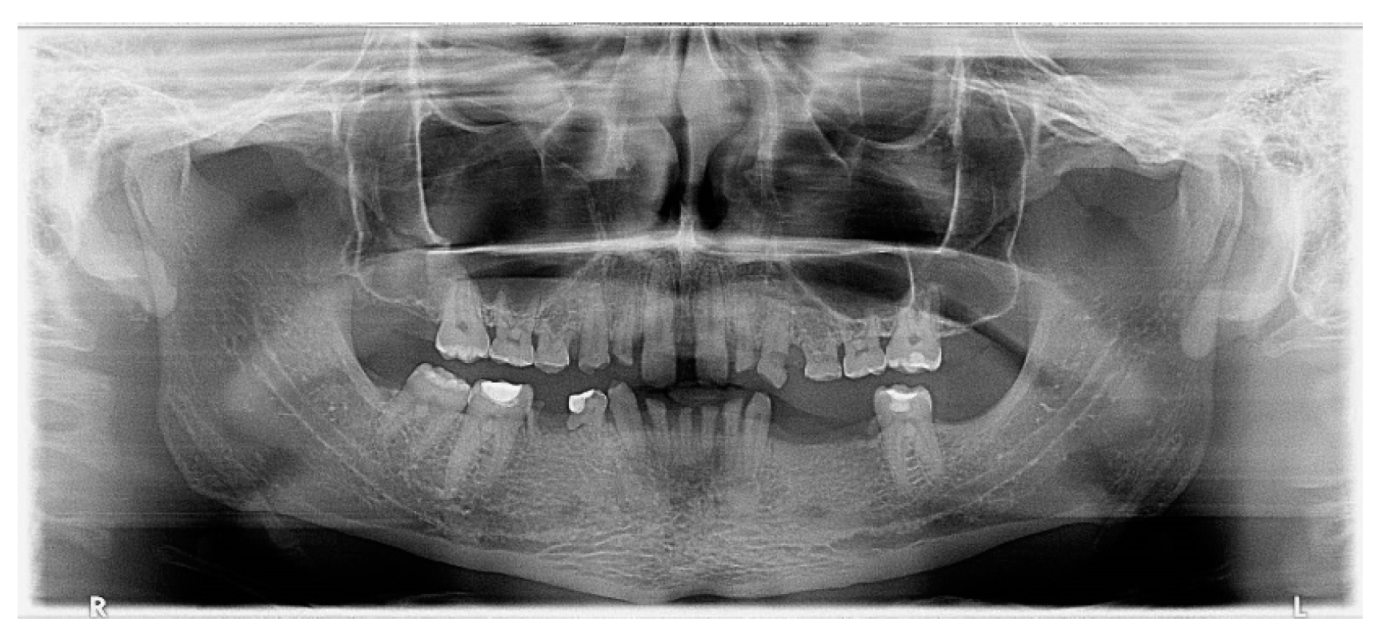

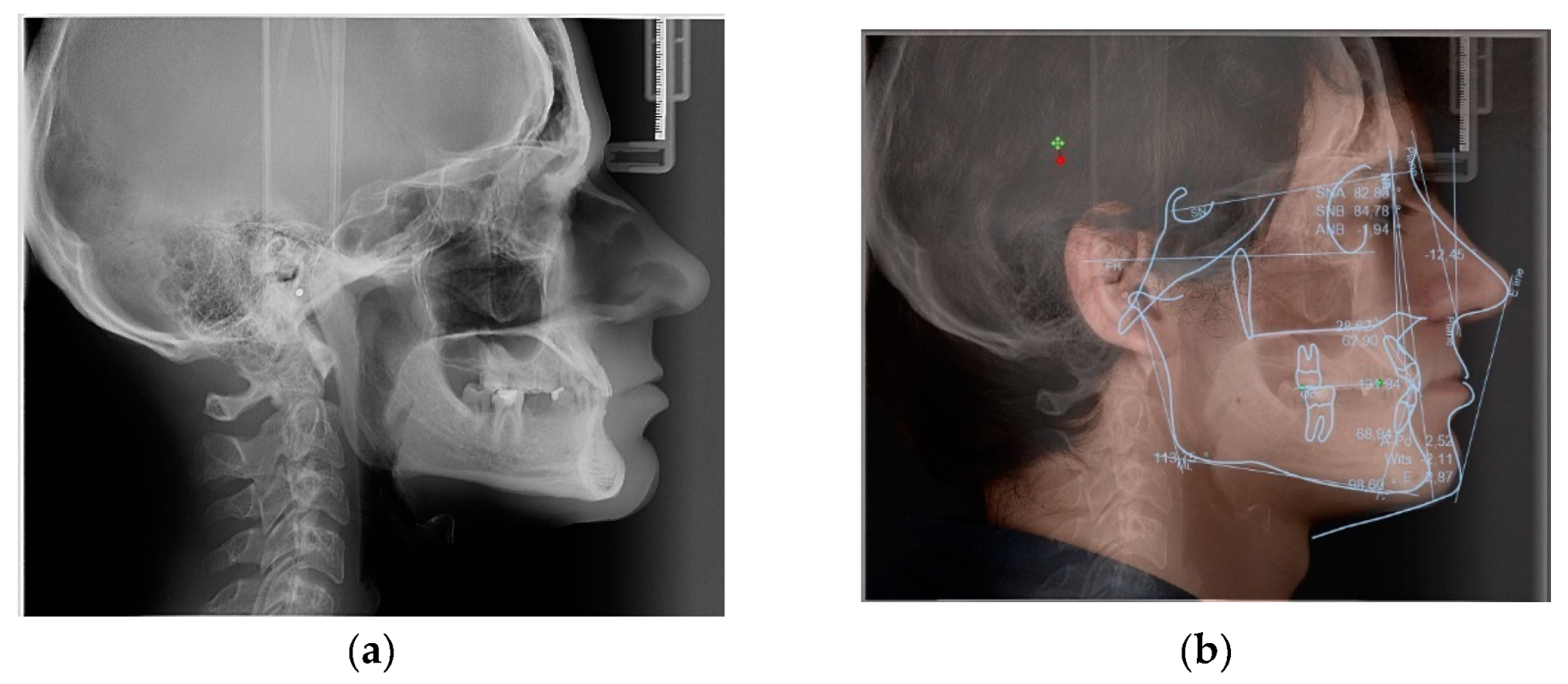

2. Case Presentation

- Treatment of the carious lesions

- Preprosthetic orthodontic treatment

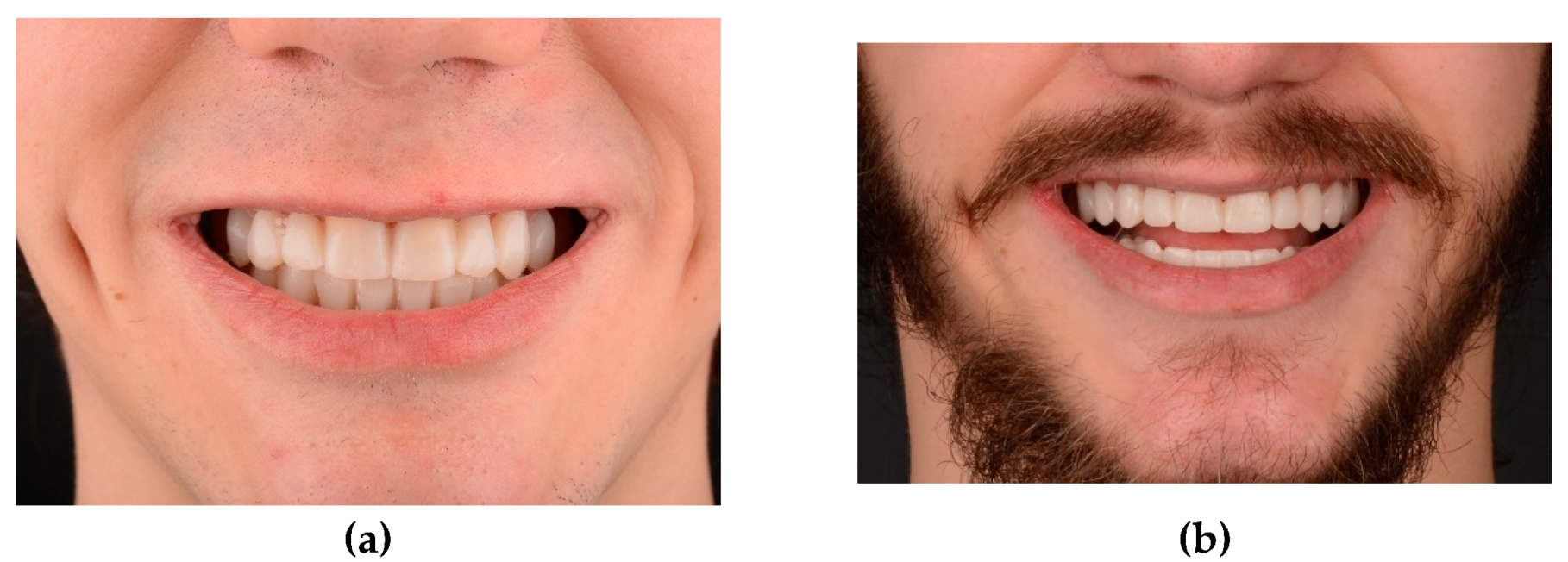

- Wax-up and mock-up

- Endodontic treatment of the lower temporary incisors.

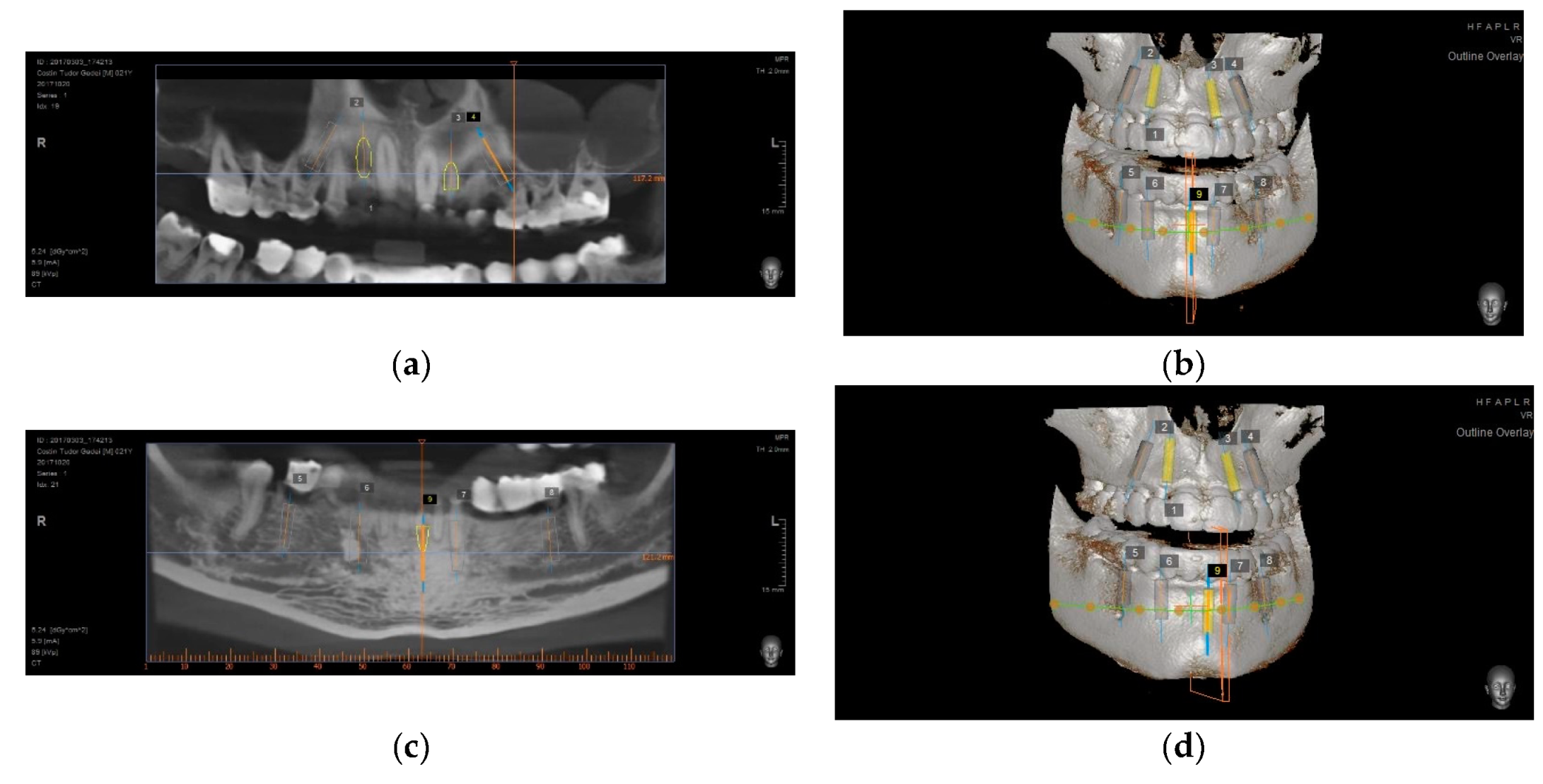

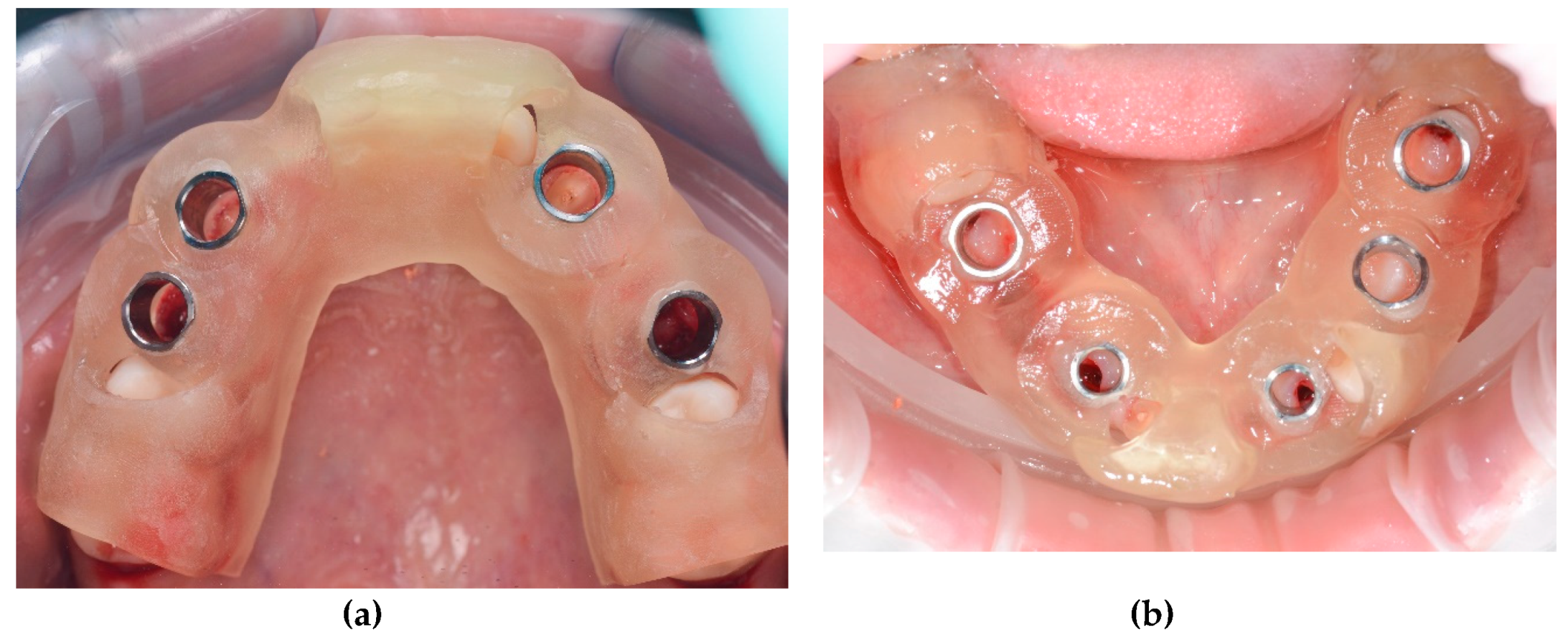

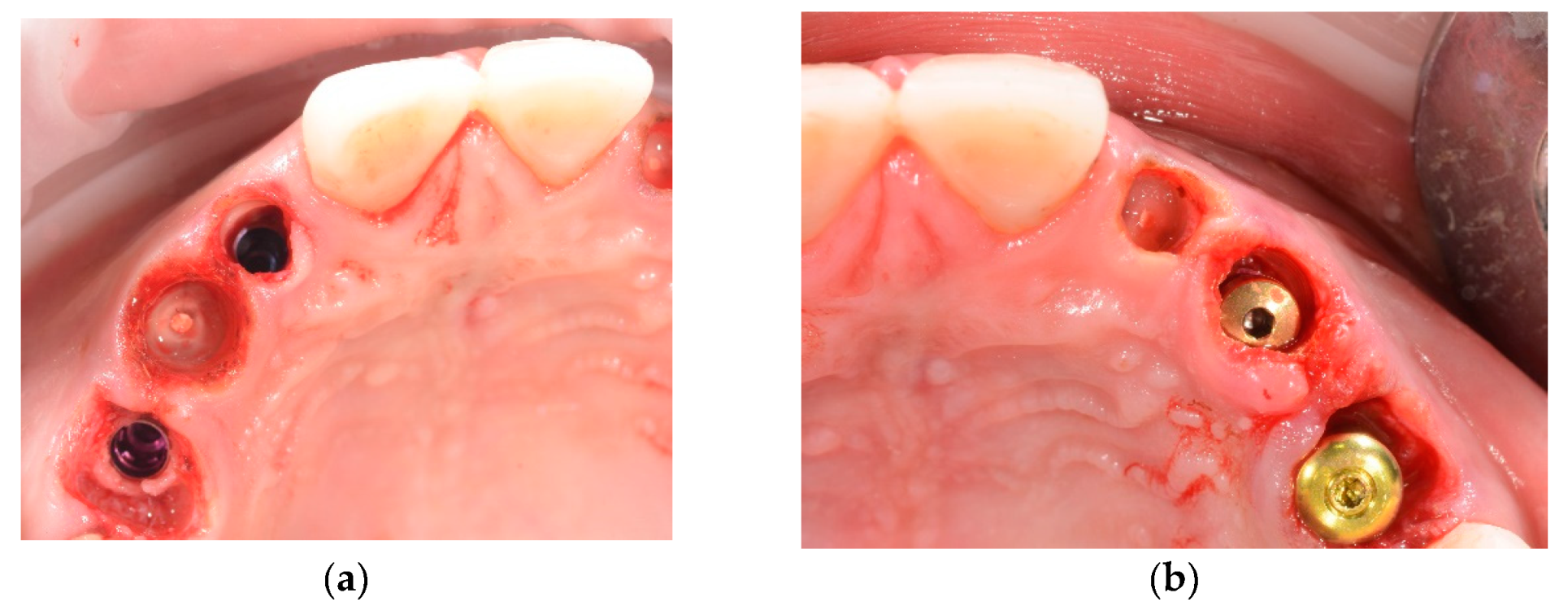

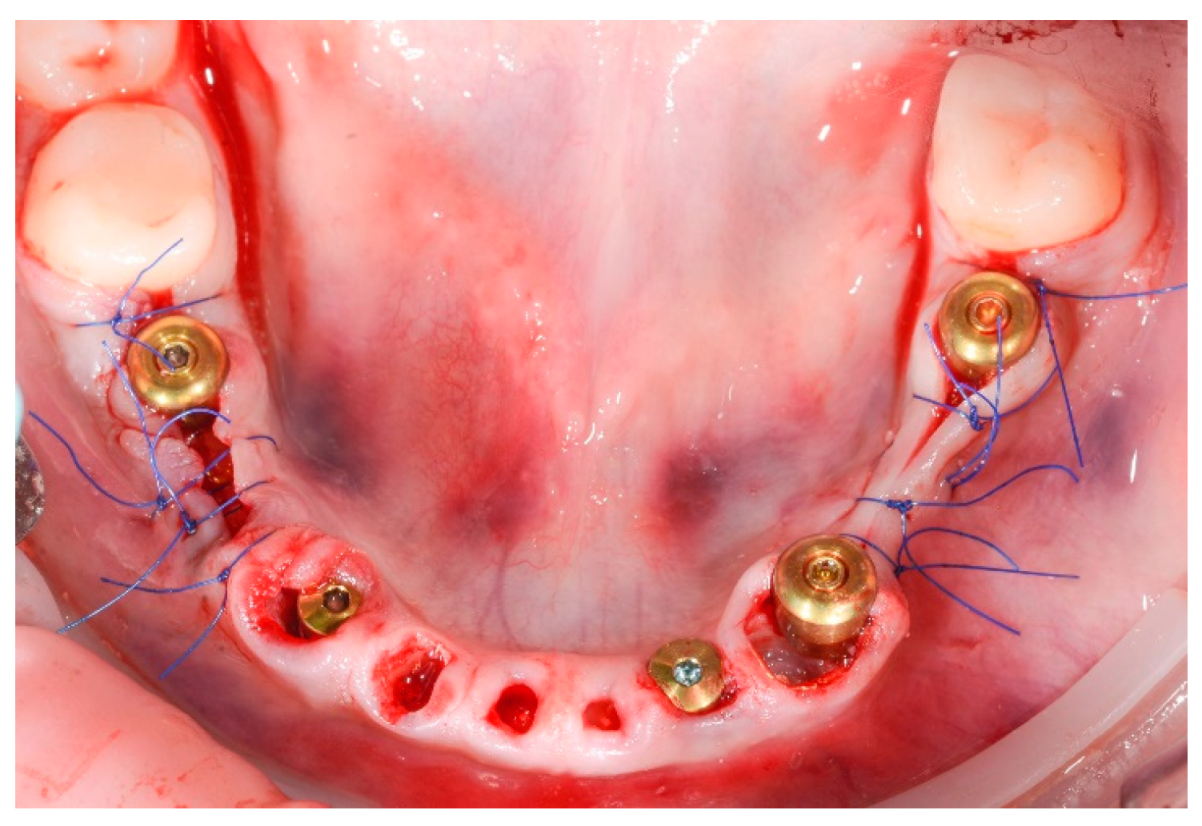

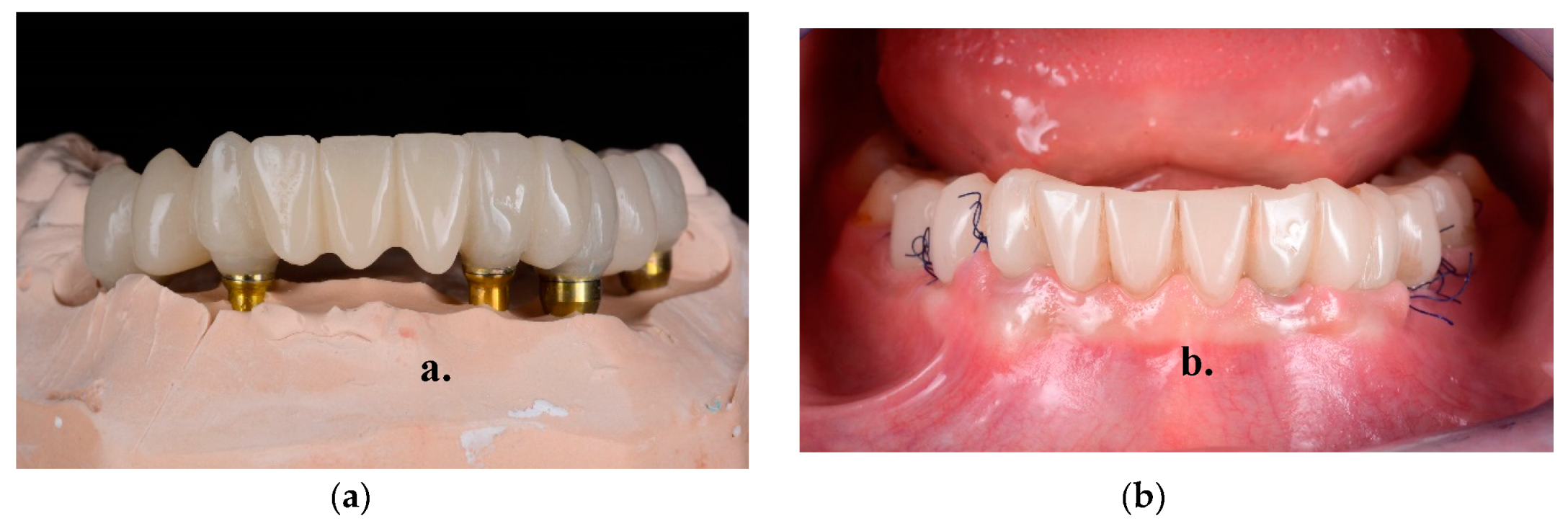

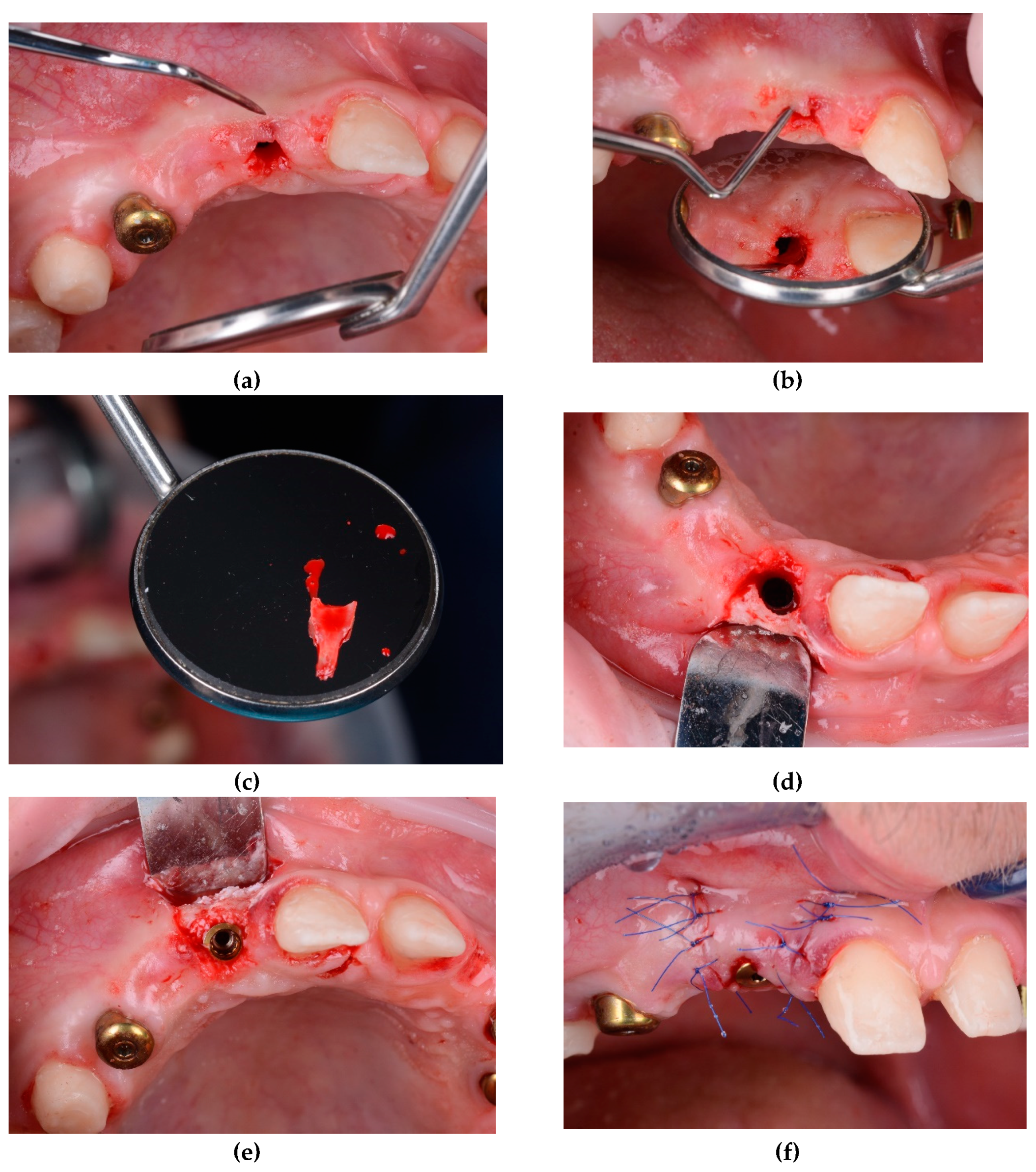

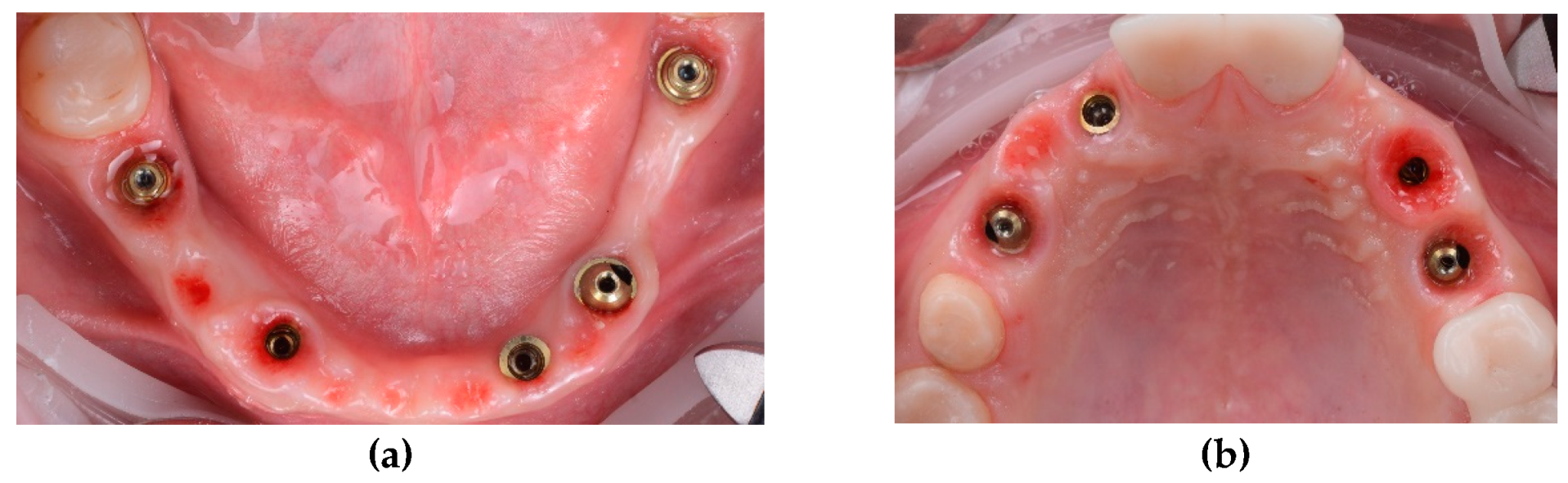

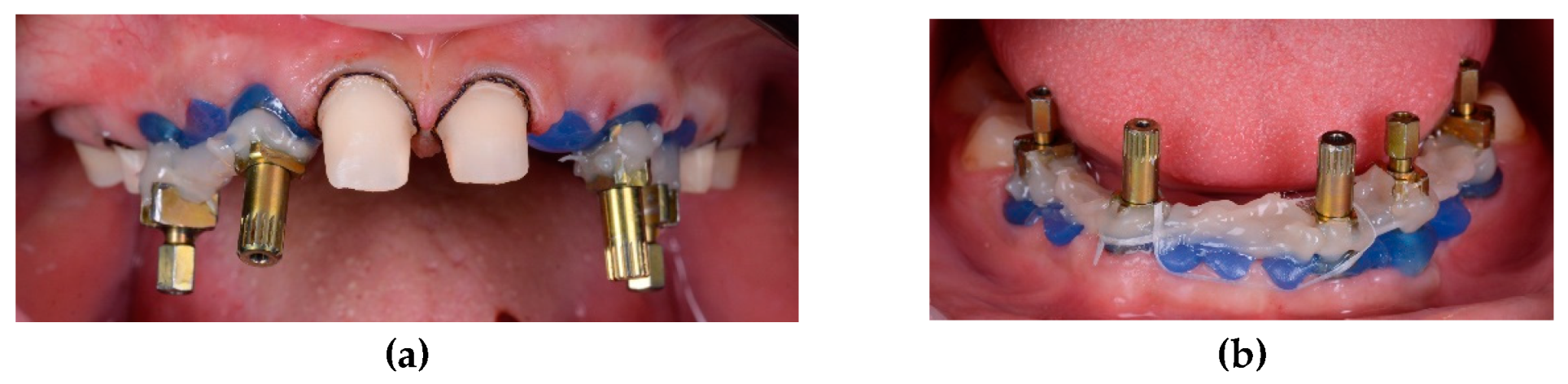

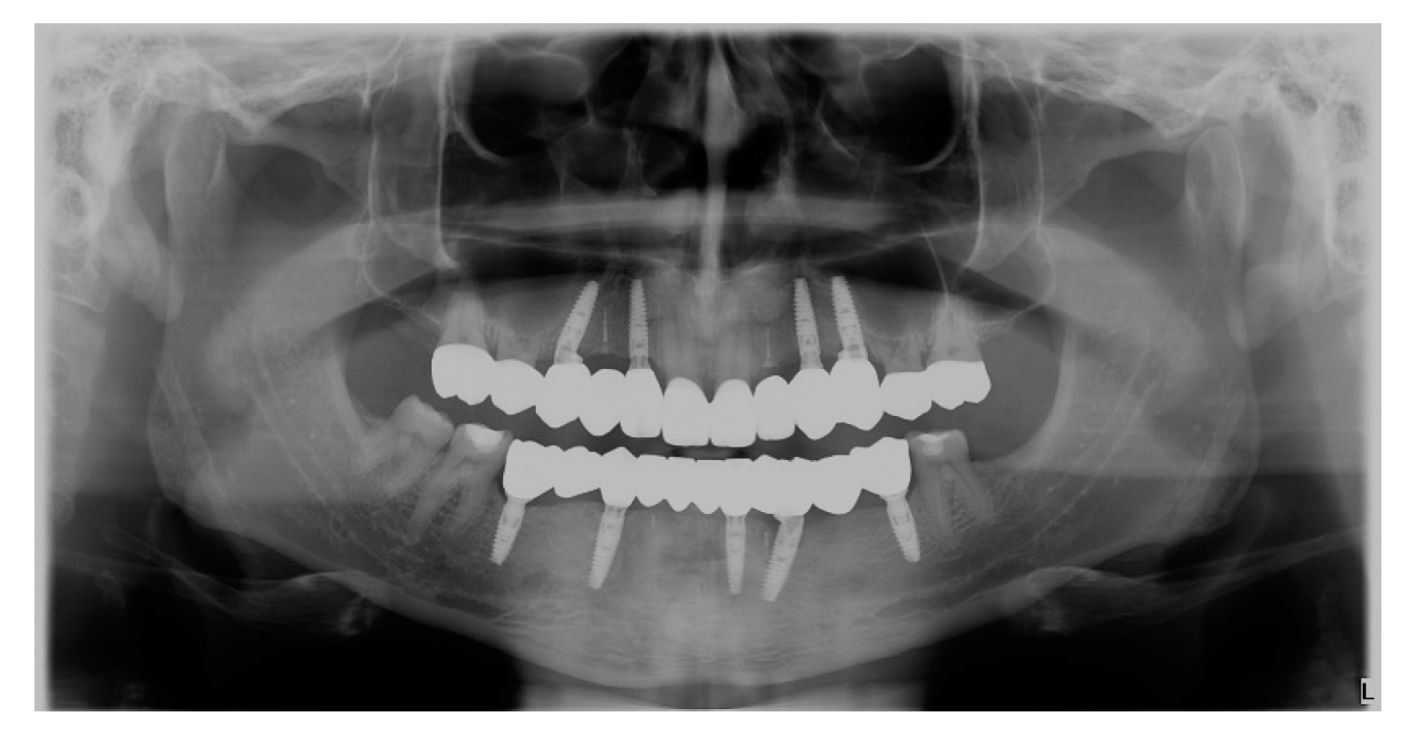

- Upper and lower implant placement with provisional restorations

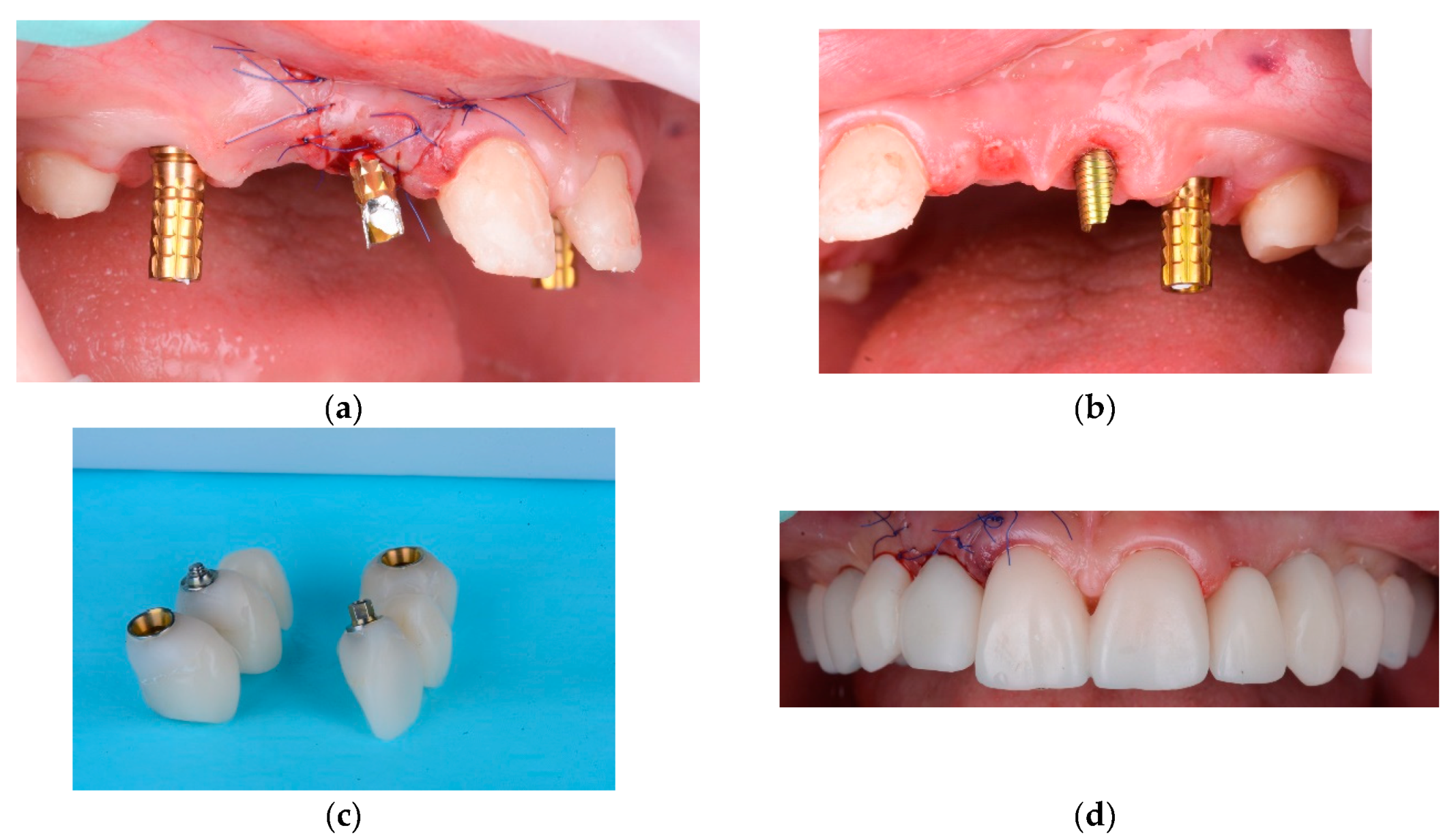

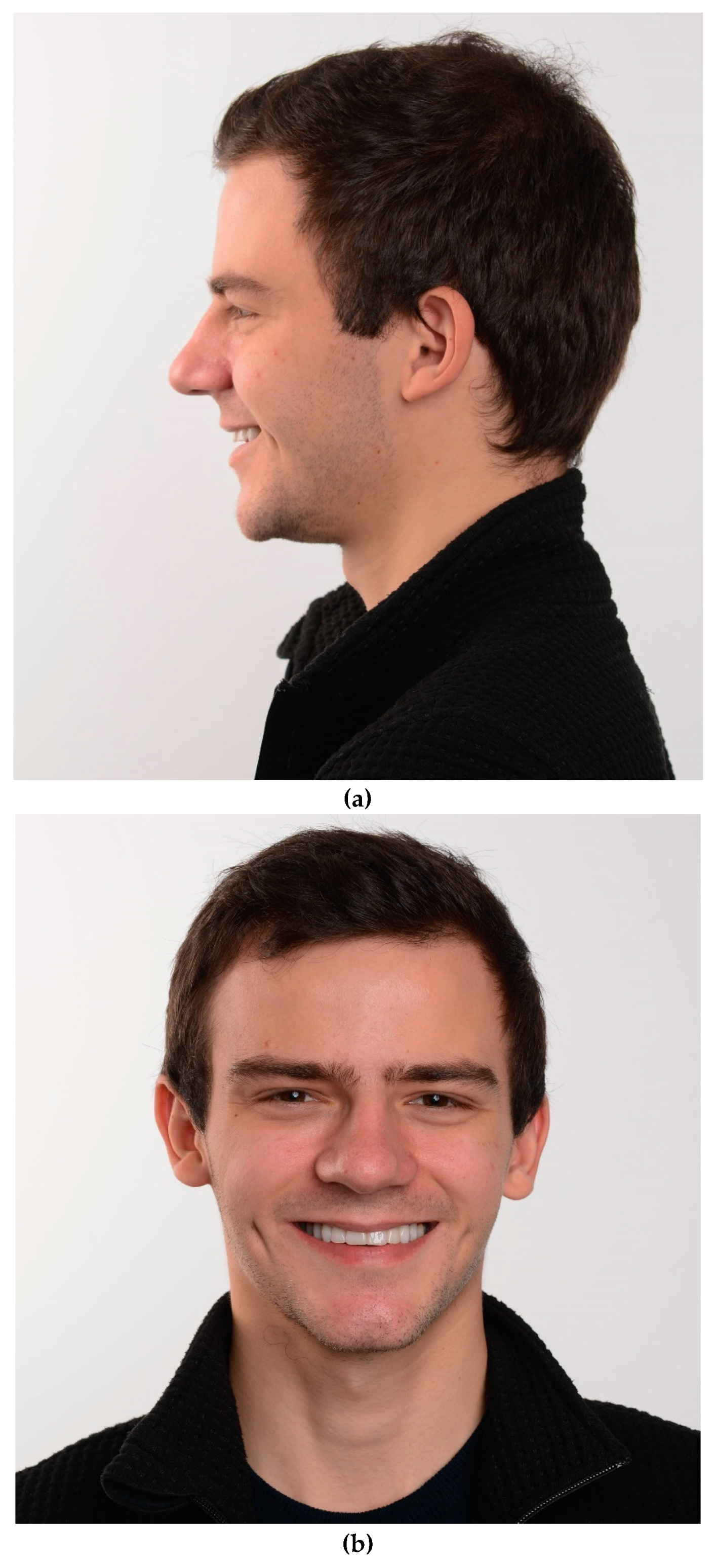

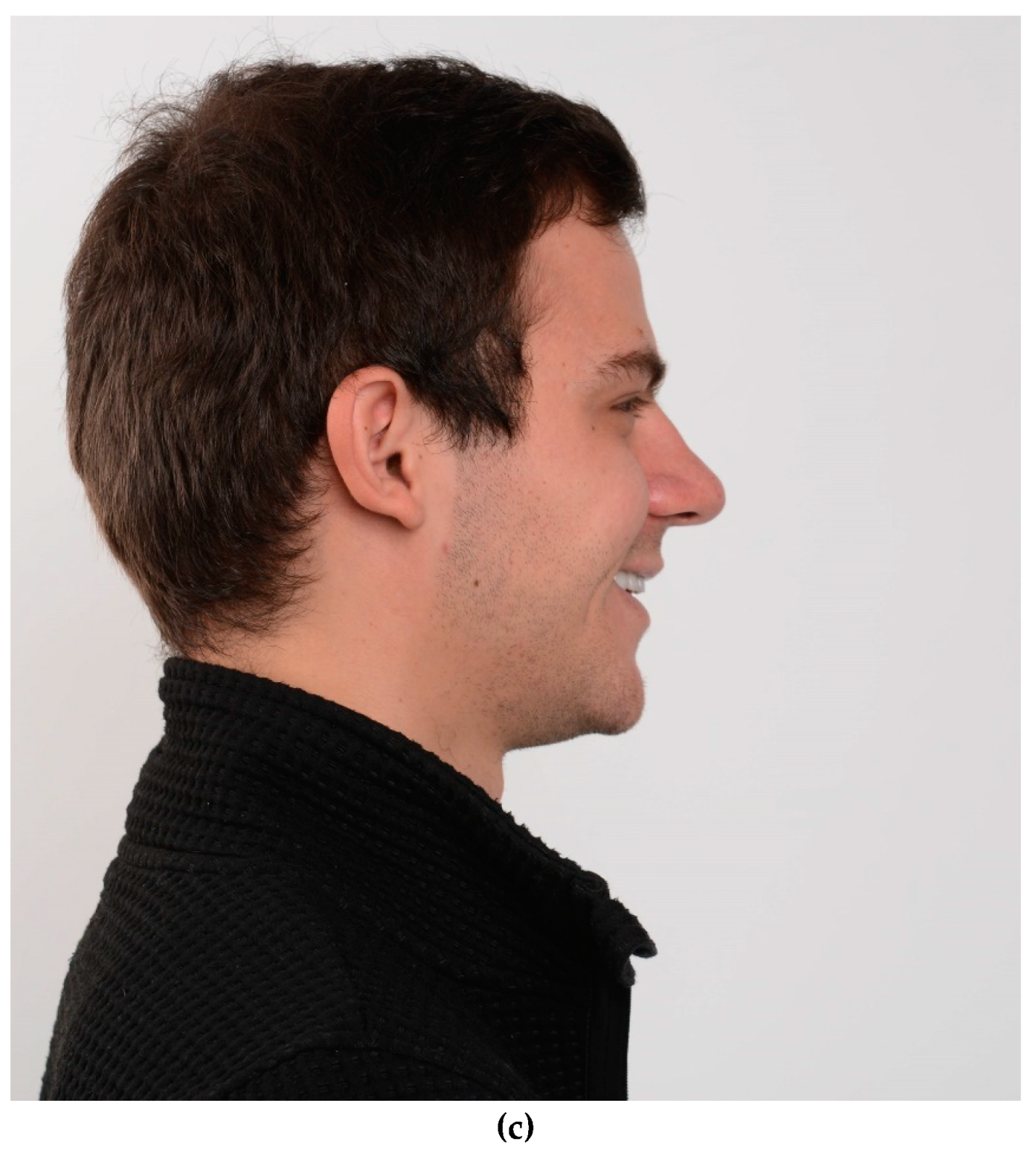

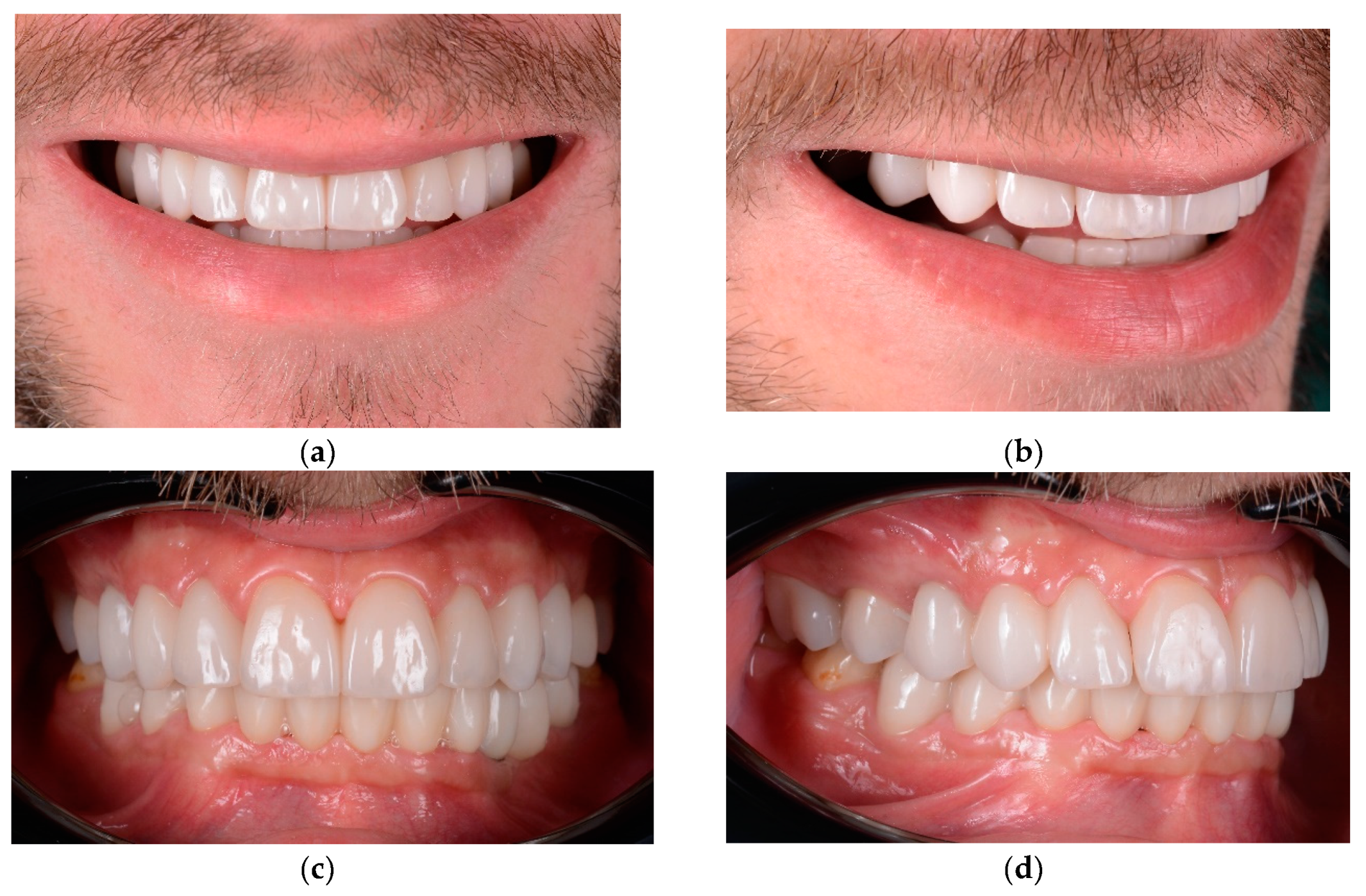

- Final restorations placement

3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biradar, V.; Biradar, S. Non-syndromic oligodontia: report of two cases and literature review. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology 2012, 3, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.; Vaysse, F. From child to adulthood, a multidisciplinary approach of multiple microdontia associated with hypodontia: case report relating a 15 Year-long management and follow-up. In Healthcare 2021, 9, 1180, MDPI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, N.; Goswami, M. Genetic basis of dental agenesis--molecular genetics patterning clinical dentistry. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014, 19, e112–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albashaireh, ZS.; Khader, YS. The prevalence and pattern of hypodontia of the permanent teeth and crown size and shape deformity affecting upper lateral incisors in a sample of Jordanian dental patients. Community Dent Health 2006, 23, 239–43.

- Calvano, E.; De Andrade, P. Assessing the proposed association between tooth agenesis and taurodontism in 975 paediatric subjects. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008, 18, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Ozoe, R. Hypodontia patterns and variations in craniofacial morphology in Japanese orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Gillgrass, T. The interdisciplinary management of hypodontia: orthodontics. Br Dent J 2003, 194, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, A.L.; Fabio, C.L. A multidisciplinary approach for the management of hypodontia: case report. Journal of Applied Oral Science, 2011, 19, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pour, R.; Saeidi, et al. A patient-calibrated individual wax-up as an essential tool for planning and creating a patient-oriented treatment concept for pathological tooth wear. Int J Esthet Dent 2018, 13, 476–492.

- Villalobos-Tinoco, J.; Jurado, C. A. Additive wax-up and diagnostic mockup as driving tools for minimally invasive veneer preparations. Cureus 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filius, M.A.; Cune, M.S. Prosthetic treatment outcome in patients with severe hypodontia: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filus, A. P.; Marieke, A.P. Three-dimensional computer-guided implant placement in oligodontia. International journal of implant dentistry 2017, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haese; Jan. Current state of the art of computer-guided implant surgery. Periodontology 2000, 2017, 73–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Zhao., J. Accuracy evaluation of computer-designed surgical guide template in oral implantology. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015, 43, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiremayh; Hemalatha P.. Endodontic treatment in submerged roots: a case report. Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects. 2010, 4, 64.

- Salama. M; Ishikawa, T. Advantages of the root submergence technique for pontic site development in esthetic implant therapy. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2007, 27, 521–527.

- Attia, S.; Schaaf, H. Oral rehabilitation of hypodontia patients using an endosseous dental implant: functional and aesthetic results. Journal of clinical medicine 2019, 8, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerekes-Máthé, B.; Mártha, K. Genetic and Morphological Variation in Hypodontia of Maxillary Lateral Incisors. Genes 2023, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonberger, S.; Shapira, Y. Prevalence and Patterns of Permanent Tooth Agenesis among Orthodontic Patients—Treatment Options and Outcome. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekonja, A. Morphological Diversity of Permanent Maxillary Lateral Incisors and Their Impact on Aesthetics and Function in Orthodontically Treated Patients. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Corchado, E.; Pardal-Peláez, B. Computer-Guided Surgery for Dental Implant Placement: A Systematic Review. Prosthesis 2022, 4, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi, M.; Spirito, F. Guided dental implant surgery: systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Ortega, E.; Jiménez-Guerra, A. Immediate loading of implants placed by guided surgery in geriatric edentulous mandible patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, R.; Acocella, A. Full-mouth rehabilitation with immediate loading of implants inserted with computer-guided flapless surgery: A 3-year multicenter clinical evaluation with oral health impact profile. Impl. Dent. 2013, 22, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. M.; Son, K. Digital evaluation of the accuracy of computer-guided dental implant placement: An in vitro study. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivovics, M.; Pénzes, D. The Influence of Surgical Experience and Bone Density on the Accuracy of Static Computer-Assisted Implant Surgery in Edentulous Jaws Using a Mucosa-Supported Surgical Template with a Half-Guided Implant Placement Protocol—A Randomized Clinical Study. Materials 2020, 13, 5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azari, A.; Nikzad, S. Computer-assisted implantology: Historical background and potential outcomes-a review. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2008, 4, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caggiano, M.; Amato, A. Evaluation of Deviations between Computer-Planned Implant Position and In Vivo Placement through 3D-Printed Guide: A CBCT Scan Analysis on Implant Inserted in Esthetic Area. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comut, A.; Mehra, M. Pontic site development with a root submergence technique for a screw-retained prosthesis in the anterior maxilla. J Prosthet Dent 2013, 110, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluckman, H.; Salama, M. Partial Extraction Therapies (PET) Part 2, Procedures and Technical Aspects. International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry, 2017, 37. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).