Submitted:

05 March 2024

Posted:

06 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review on SIA

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

References

- Agencia de Desarrollo Rural. (2021). Plan Integral de Desarrollo Agropecuario y Rural con enfoque Territorial – Departamentos de Tolima, Chocó, Bolívar y Meta.

- Alaie, S. A. (2020). Conocimiento y aprendizaje en el sistema de innovación hortícola: un caso del valle de Cachemira en la India. Revista Internacional de Estudios de Innovación, 4(4), 116-133. [CrossRef]

- Alcázar Quiñones, A. T. (2017). Metodología "Arreglos y Sistemas Productivos Innovativos Locales" en municipios cubanos. Retos de la Dirección, 11(2), 198-212. DOI http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2306-91552017000200013&lng=es&tlng=pt.

- Barzola Iza, CL , Dentoni, D. y Omta, OSWF (2020). The influence of Multi-Stakeholder Platforms on farmers' innovation and rural development in emerging economies: A systematic literature review Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, vol. 10 N° 1, págs. 13-39. [CrossRef]

- Benítez, Odio, M., Martínez Robaina, A., Herrera Gallo, M., Páez Fernández, P. L., del Busto Concepción, A. (2020). "Estrategia para implementar la gestión del conocimiento en el Sistema de Innovación Agropecuario Local". Coodes, 45-56. Disponible en: http://coodes.upr.edu.cu/index.php/coodes/article/view/267.

- Cofré-Bravo, G., Klerkx, L. y Engler, A. (2019). Combinaciones de vínculos, puentes y vinculaciones de capital social para la innovación agrícola: cómo los agricultores configuran diferentes redes de apoyo. Revista de Estudios Rurales , 69 , 53-64.

- Clarkson, G., Garforth, C., Dorward, P., Mose, G., Barahona, C., Areal, F., & Dove, M. (2018). Can the TV makeover format of edutainment lead to widespread changes in farmer behavior and influence innovation systems? Shamba Shape Up in Kenya. Land Use Policy, 76, 338-351. [CrossRef]

- Dieleman, H. (2019). Enfoque de Sistema de Innovación para la Agricultura Urbana: Estudio de Caso de la Ciudad de México. Innovaciones en Agricultura Sostenible, 79-102. [CrossRef]

- DNP. (2020). Índice de desarrollo de las TIC regionales para Colombia. Consultado a través de https://www.dnp.gov.co/DNPN/Documents/Indice%20de%20desarrollo%20de%20las%20TIC%20regional%20para%20Colombia.pdf.

- Dosi, G. (1988). The Nature of the Innovation Process. In G. Dosi, C. Freeman, R. Nelson, G. Silverberg, & L. Soete (Eds.), Technical Change and Economic Theory (pp. 221-238). London: Pinter.

- Douthwaite, B., & Hoffecker, E. (2017). Towards a complexity-aware theory of change for participatory research programs working within agricultural innovation systems. Agricultural systems, 155, 88-102. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2015). La técnica de procesamiento FTT-Thiaroye, una innovación para la reducción de pérdidas poscosecha en la pesca y la acuicultura. Documento presentado en el Primer Congreso Internacional sobre Prevención de la Pérdida de Alimentos, 2015, Roma. (también disponible en http://www.fao.org/food-loss-reduction/news/details/es/c/369935/).

- Fielke, S. J., Nelson, T., Blackett, P., Bewsell, D., Bayne, K., Park, N., ... & Small, B. (2017). Hitting the bull's-eye: the role of a reflexive monitor in New Zealand Agricultural Innovation Systems. In 12th European International Farming Systems Association (IFSA) Symposium, Social and technological transformation of farming systems: Diverging and converging pathways, 12-15 July 2016, Harper Adams University, Newport, Shropshire, UK (pp. 1-13). International Farming Systems Association (IFSA) Europe. [CrossRef]

- Foray, D., & Lundvall, B. - A. (1996). The Knowledge-based Economy: From the Economics of Knowledge to the Learning Economy. Paris: Employment and Growth in the Knowledge-based Economy.

- Freeman, C. (1987). Technology policy and economic performance: Lessons from Japan, London, Pinter Publishers.

- Giagnocavo, C., de Cara-García, M., González, M., Juan, M., Marín-Guirao, J. I., Mehrabi, S., ... & Crisol-Martínez, E. (2022). Reconectar a los agricultores con la naturaleza a través de transiciones agroecológicas: nichos interactivos y experimentación y el papel de los sistemas de innovación y conocimiento agrícola. Agricultura, 12(2), 137. [CrossRef]

- Hakansson, H. (1987). Industrial technology development: A network approach. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 4 (2), 163-165.

- Kamara, L. I., Dorward, P., Lalani, B., & Wauters, E. (2019). Unpacking the drivers behind the use of the Agricultural Innovation Systems (AIS) approach: The case of rice research and extension professionals in Sierra Leone. Agricultural Systems, 176, 102673. [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L., & Nettle, R. (2013). Achievements and challenges of innovation co-production support initiatives in the Australian and Dutch dairy sectors: a comparative study. Food policy, 40, 74-89. [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L., & Engler, A. (2019). Combinaciones de vínculos, puentes y vinculaciones de capital social para la innovación agrícola: cómo los agricultores configuran diferentes redes de apoyo. Revista de Estudios Rurales, 69, 53-64.

- Kingiri, A. N. (2013). A review of innovation systems framework as a tool for gendering agricultural innovations: Exploring gender learning and system empowerment. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 19(5), 521-541. [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A. (2012). Facilitating Agricultural Innovation Systems: A Critical Realist Approach. Studies in Agricultural Economics, 114(1316-2016-102761), 64-70. [CrossRef]

- Leontief, W. W. (1941). The structure of the American economy, 1919-1929: An empirical application of equilibrium analysis. Harvard University Press.

- Ley 1876 de 2017. Por medio de la cual se crea el Sistema Nacional de Innovación Agropecuaria y se dictan otras disposiciones. 29 de diciembre de 2017.

- List, F. (1841). The national system of political economy. Vernon Press.

- Lundvall, B. A., & Johnson, B. (1994). Sistemas nacionales de innovación y aprendizaje institucional. Comercio exterior, 44(8), 695-704.

- Malerba, F. (2005). Sectoral system of innovation: a framework for linking innovation to the knowledge base, structure, and dynamics of sectors. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 14(1-2), 63-82.

- Metcalfe, J. S. (1995). Technology systems and technology policy in an evolutionary framework. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1), 25-46. [CrossRef]

- Moreddu, C. , & Van Tongeren, F. (2013). Improving agricultural productivity sustainably at a global level: the role of agricultural innovation policies. EuroChoices, 12(1), 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Nederlof, E. S. , Röling, N., & Van Huis, A. (2007). Pathway for agricultural science impact in West Africa: lessons from the Convergence of Sciences program. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 5(2-3), 247-264. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R. R. (Ed.). (1993). National innovation systems: a comparative analysis. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). The Schumpeterian tradeoff revisited. The American Economic Review, 72(1), 114-132.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (2015). El estado mundial de la agricultura y la alimentación: la innovación en la agricultura familiar. Roma, Italia: FAO. Recuperado de: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4040s.pdf.

- Organización para la Cooperación y Desarrollo Económico (2013). Sistemas de innovación agrícola: un marco para analizar el papel del gobierno. Publicaciones de la OCDE. Recuperado de: https://www.oecd.org/publications/agricultural-innovation-systems-9789264200593-en.htm.

- Padilla-Pérez, R. , Vang, J., & Chaminade, C. (2009). Regional innovation systems in developing countries: integrating micro and meso-level capabilities. En B.-Å. Lundvall, K. J. Joseph, C.

- Pigford, A. A. E. , Hickey, G. M., & Klerkx, L. (2018). Beyond agricultural innovation systems? Exploring an agricultural innovation ecosystems approach for niche design and development in sustainability transitions. Agricultural systems, 164, 116-121. [CrossRef]

- Plataforma de Agricultura Tropical (2017). Marco Común sobre el Desarrollo de Capacidades para los Sistemas de Innovación Agrícola: Antecedentes Conceptuales. CAB Internacional, Wallingford, Reino Unido. Doi: Recuperado de: http://www.fao.org/in-action/tropical-agriculture-platform/commonframework/es/.

- Poti, S. , & Joy, S. (2022). Plataformas digitales para conectar actores en el espacio agtech: conocimientos sobre el desarrollo de plataformas a partir de la investigación de acción participativa en KisanMitr. Revista de investigación empresarial india, 14(1), 65-83. Revista de investigación empresarial india, vol. 14 núm. 1, págs. 65-83. [CrossRef]

- Quintero, S. , Giraldo, D. P., & Garzón, W. O. (2022). Análisis de los Patrones de Especialización de un Sistema de Innovación Agropecuaria: Un Estudio de Caso sobre la Cadena Productiva del Banano (Colombia). Sustentabilidad, 14(14), 8550. [CrossRef]

- Robledo, J. (2010). Introducción a la Gestión Tecnológica. Medellín: Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Medellín.

- Spendrup, S. , & Fernqvist, F. (2019). Innovation in agri-food systems–a systematic mapping of the literature. International Journal on Food System Dynamics, 10(5), 402-427. [CrossRef]

- Sseguya, H. , Mazur, R., Abbott, E., & Matsiko, F. (2012). Information and communication for rural innovation and development: context, quality, and priorities in southeast Uganda. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 18(1), 55-70. [CrossRef]

- Storper, M. (1995). Regional technology coalitions are An essential dimension of national technology policy. Research Policy, 24, 895 - 911.

- Vom Brocke, K., Kondombo, C. P., Guillet, M., Kaboré, R., Sidibé, A., Temple, L., & Trouche, G. (2020). Impact of participatory sorghum breeding in Burkina Faso. Agricultural Systems, 180, 102775. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X., Chen, J., & Li, J. (2022). Sistema de innovación rural: Revitalizar el campo para un desarrollo sostenible. Revista de Estudios Rurales, 93, 471-478. [CrossRef]

- Zossou, E., Saito, K., Assouma-Imorou, A., Ahouanton, K., & Tarfa, B. D. (2021). Participatory diagnostic for scaling a decision support tool for rice crop management in northern Nigeria. Development in Practice, 31(1), 11-26. [CrossRef]

| Description | Problem addressed | Actors involved | How does the innovation system work? |

|---|---|---|---|

| China compares rural and urban innovation systems and proposes a theoretical structural model of rural innovation systems [37] | Rural decline, poverty, unsustainability, poor land management, etc. | Government, congress, public sector, nonprofit companies, etc. | The study examines previous theories, proposes a three-dimensional model, and points out the challenges to strengthening rural innovation, contributing to national development and rural revitalization. In addition, it uses mixed methods to analyze niche activities in intensive greenhouse agriculture and promote the transition to sustainability through conceptual frameworks and farm management approaches. |

| Explores the processes of transition to sustainability in agriculture through four niche initiatives in the greenhouse sector [38]. | Sustainability, resource depletion, pollution, etc. | Farmers, distributors, cooperatives, processors, etc. | This article uses mixed methods to analyze four case studies in the intensive agriculture system of Almeria, employing diverse conceptual frameworks and multi-stakeholder approaches to explore activity niches. It uses Gliessman's five levels of agroecology framework as a guide for the transition to sustainability in the agri-food system. |

| Social networks play a key role in agricultural innovation by providing farmers with information, knowledge, and resources to boost their innovation efforts, while formal institutions advise on techniques and technologies for apple crops in the Kashmir Valley, India [39]. | Apple tree canker disease, productivity, sustainability | Government organizations, advisors, farmers, policymakers, businesses, traders, processors, transporters, input suppliers, regulatory agencies, extension services, service providers, and civil societies are involved in the agricultural context. | This study collected primary and secondary data from a variety of sources, including focus group discussions and specialized literature, to explore the actors and processes of knowledge generation in the agricultural system. It also provides a platform for future studies on informal innovations and social networks in different aspects of horticulture and the analysis of interactions between informal and formal actors in the innovation and sustainability system. |

| Air pollution, drought, urban heating, energy expenditure, extreme temperature fluctuations inside buildings, and poor or contaminated soils [40]. In Mexico | Urban agriculture in Mexico City is analyzed as an innovation system that includes boundaries, dynamics, institutions, knowledge, and learning cultures, being an integral part of the ecological infrastructure for urban sustainability and resilience, where vertical and rooftop gardens play an important role in the greening of cities. | Institutions, industries, government, NGOs, private companies, households, start-up companies of young academic graduates | Between 2007 and 2012, the Mexico City government invested US$6 million in 2,800 urban agriculture projects, benefiting 15,700 inhabitants and supporting 3,000 families with rooftop gardens and green roofs on schools and government buildings, thus fostering small-scale, sustainable urban agriculture in the city. |

| Smart agriculture improves efficiency and sustainability through technologies such as IoT and drones. This study in Antioquia, Colombia, analyzes the banana chain and simulates interactions between actors to develop technological capabilities and address productivity and sustainability problems [41]. In Colombia. | Low productivity of banana crops, unsustainable crops | Agents, explorers, intermediaries, and exploiters | This paper presents an agent-based model that simulates interactions and learning in a competitive environment, representing demands as opportunities for innovation. The model is structured in five procedures that include the construction of offers, decision rules, and the local learning process, allowing one to observe the specialization patterns and accumulation of capabilities of competing agents. |

| This article analyzes the role of digital platforms, using the case study of KisanMitr, in connecting and facilitating the agricultural innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystem [42] In India. | Sustainability in pandemic | Governments and farmers | Digital platforms can be the backbone of integrated agricultural innovation systems, but it is important to keep the focus on farmers, foster mutual engagement, and address potential governance issues to have a meaningful impact. |

| Phase | Shares |

|---|---|

| 1 | -Manage and execute four pilots in 8 municipalities (2 for each pilot). - Identify and collect information from the UPA (Agricultural Production Units) - Identify and collect information from the UPAs (Agricultural Production Units). -Prioritization of municipalities. -Design pilot instruments for data collection. -Implement pilots |

| 2 | - Identify distinctive characteristics of each municipality (geographic location, population, territorial dispersion, productive chain, organic production, focus on carbon emissions reduction. -Analyze gaps in access to ICTs in the pilots. |

| 3 | - Identify and articulate actors that generate and implement knowledge in agricultural science, technology, and innovation. -Closing of gaps and spaces for social participation. -Information gathering and analysis with mapping of actors and variables. |

| 4 | -Generate a final document with conclusions and recommendations for each pilot implemented. |

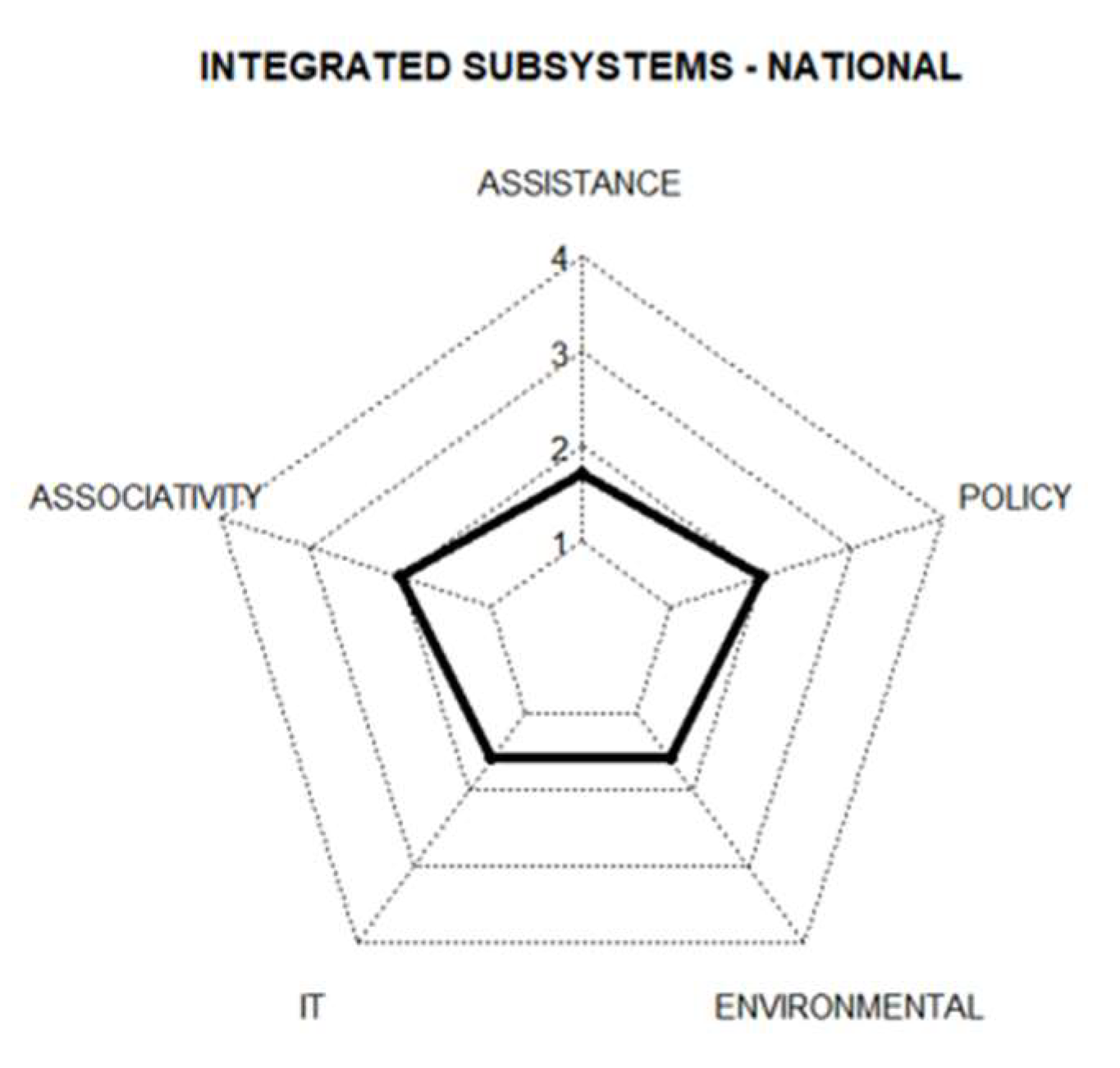

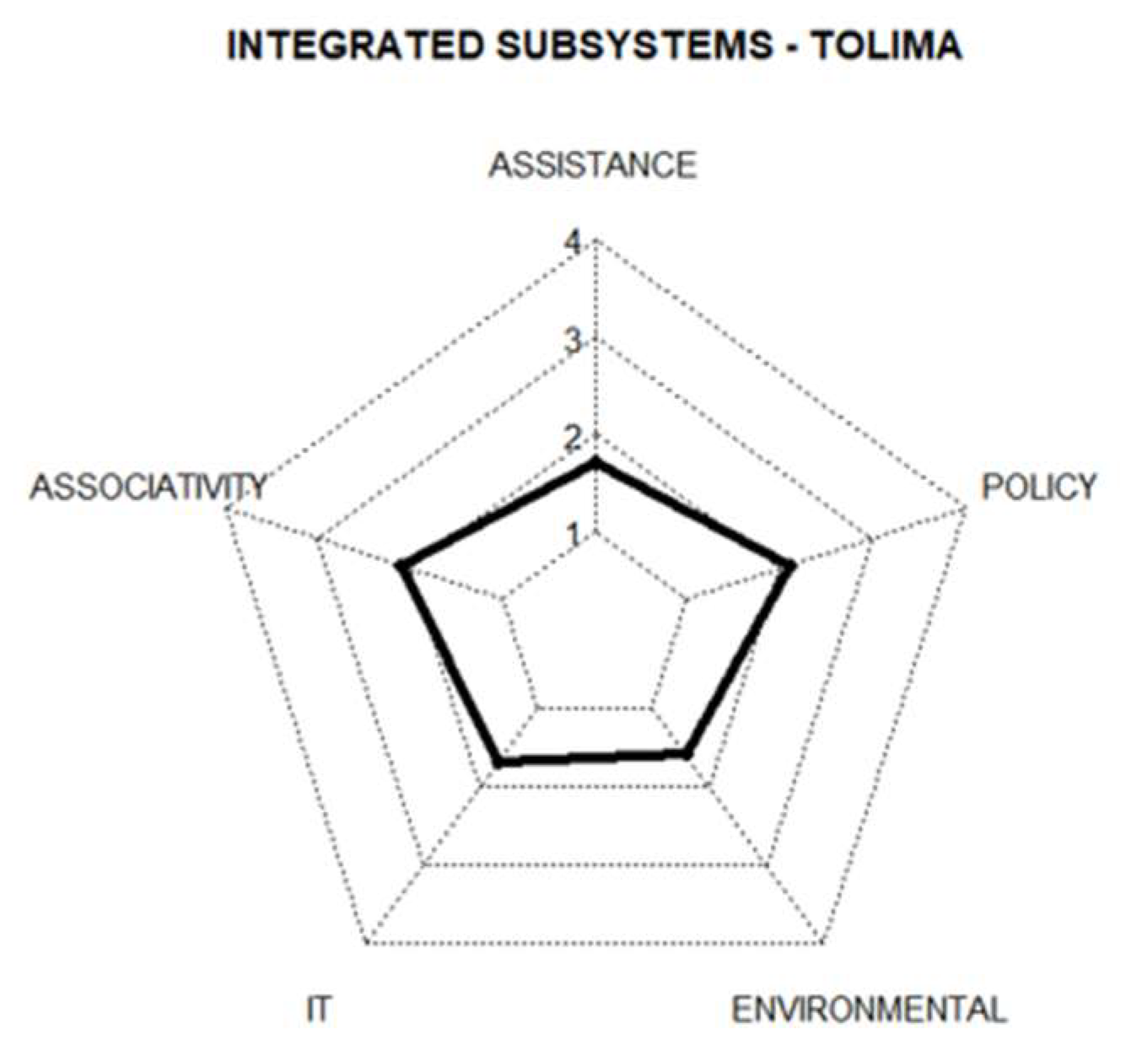

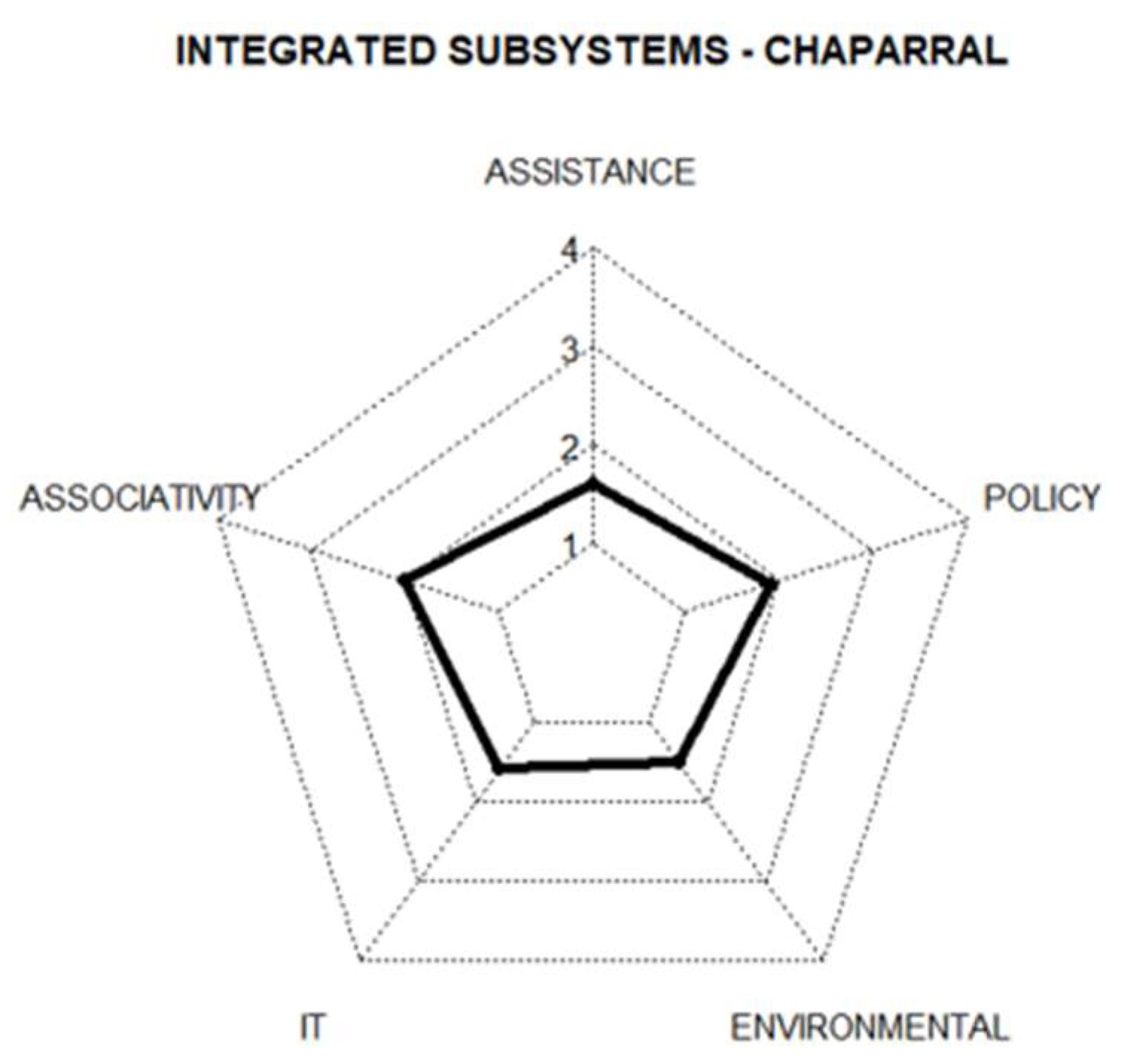

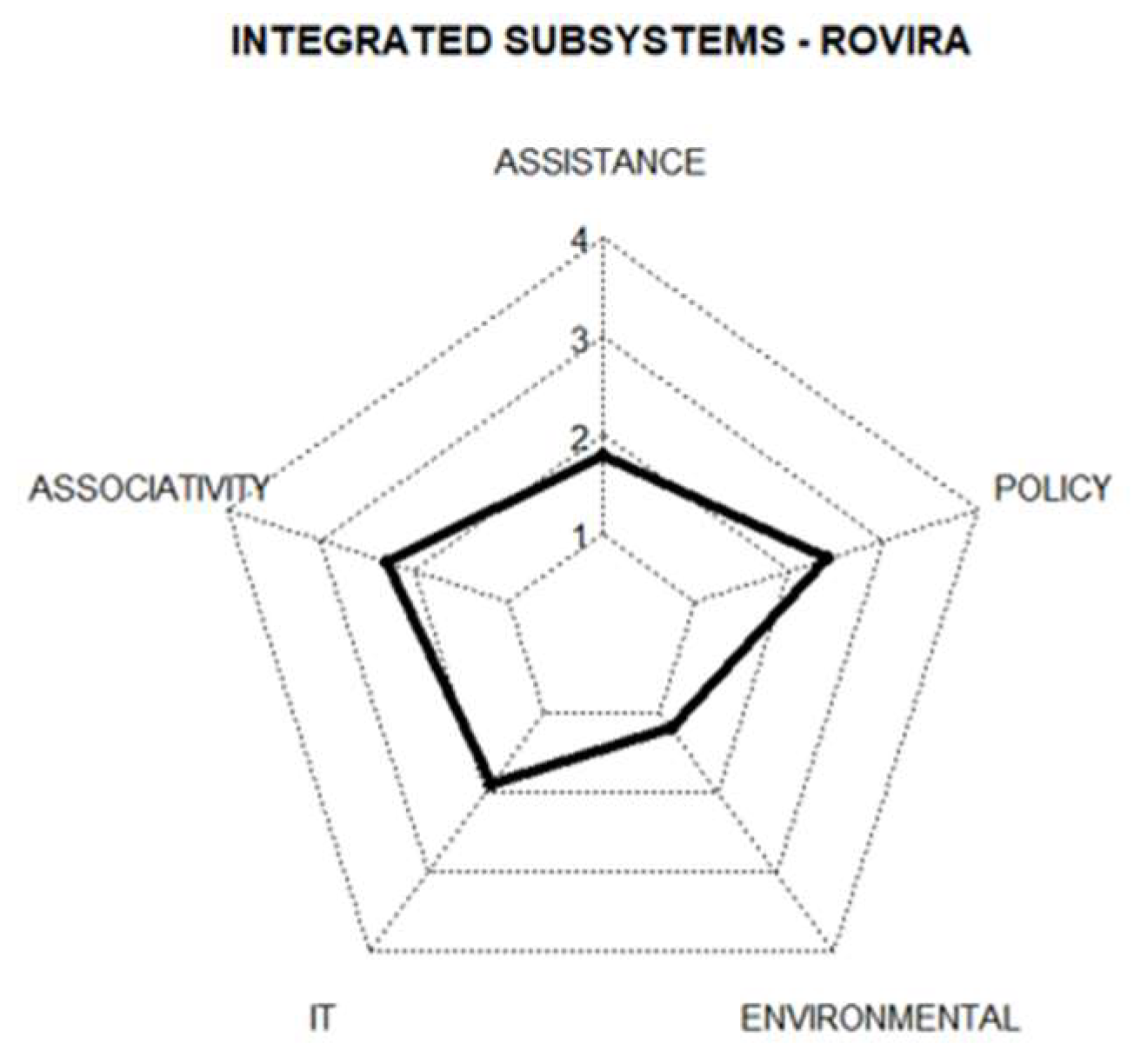

| MUNICIPALITY | TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE | ASSOCIATIVITY | ICTs | ENVIRONMENTAL | PUBLIC POLICY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAN JUAN NEPOMUCENO | 1,445844905 | 2,168874172 | 1,454746137 | 1,311258278 | 1,390728477 |

| SANTA ROSA DEL SUR | 1,825591398 | 2,043333333 | 1,728888889 | 1,855555556 | 2,252380952 |

| JURADÓ | 1,52660243 | 2,214285714 | 1,536796537 | 1,443181818 | 2,305194805 |

| SAN JOSÉ DEL PALMAR | 1,45655914 | 1,533333333 | 1,26 | 1,356666667 | 1,366666667 |

| CABUYARO | 2,129462366 | 1,94 | 2,12 | 1,851666667 | 2,31047619 |

| VISTAHERMOSA | 1,549677419 | 1,916666667 | 1,345555556 | 1,441666667 | 1,86 |

| CHAPARRAL | 1,635913978 | 2,013333333 | 1,551111111 | 1,477222222 | 1,885714286 |

| ROVIRA | 1,841505376 | 2,276666667 | 1,897777778 | 1,166666667 | 2,402857143 |

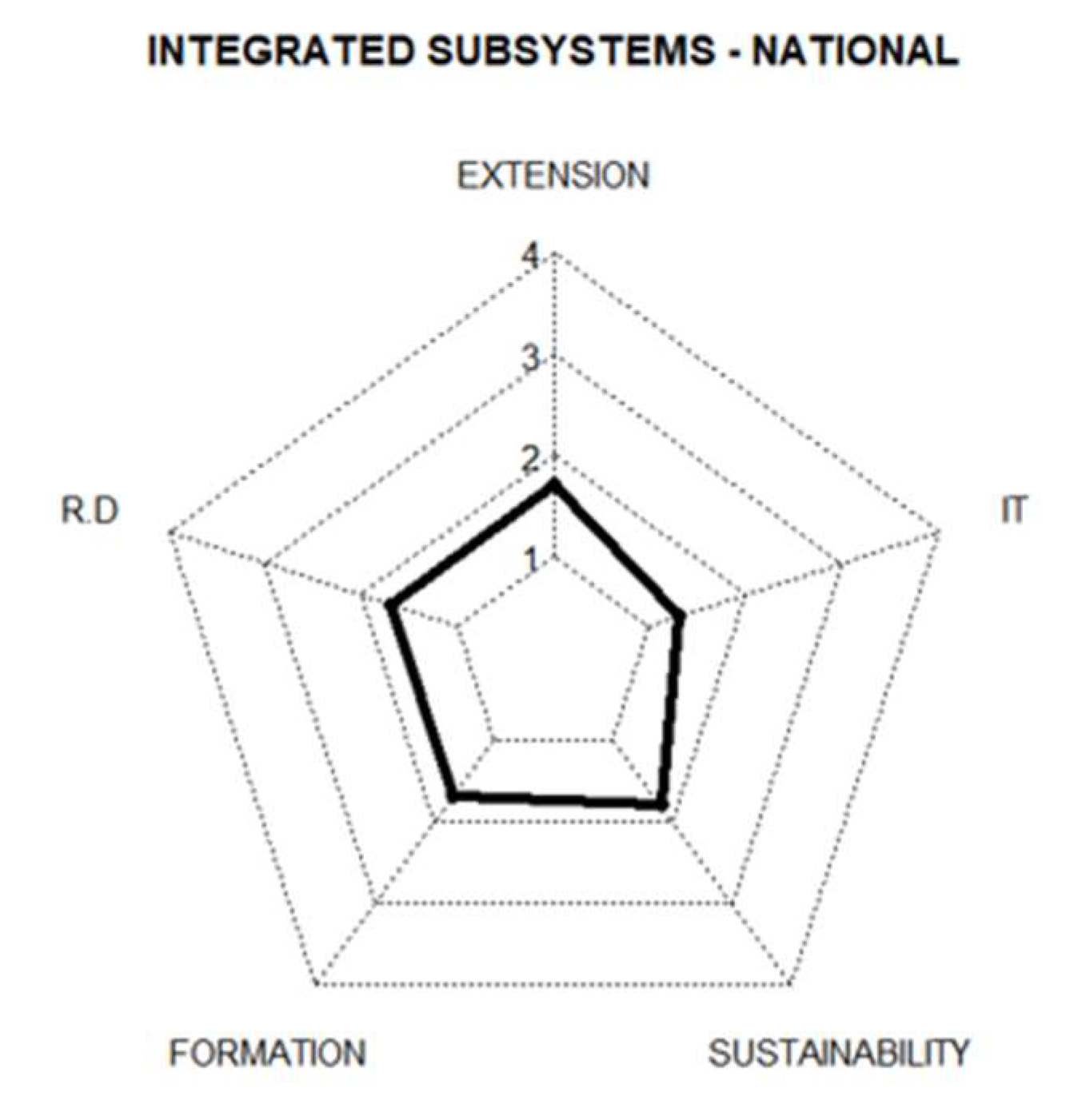

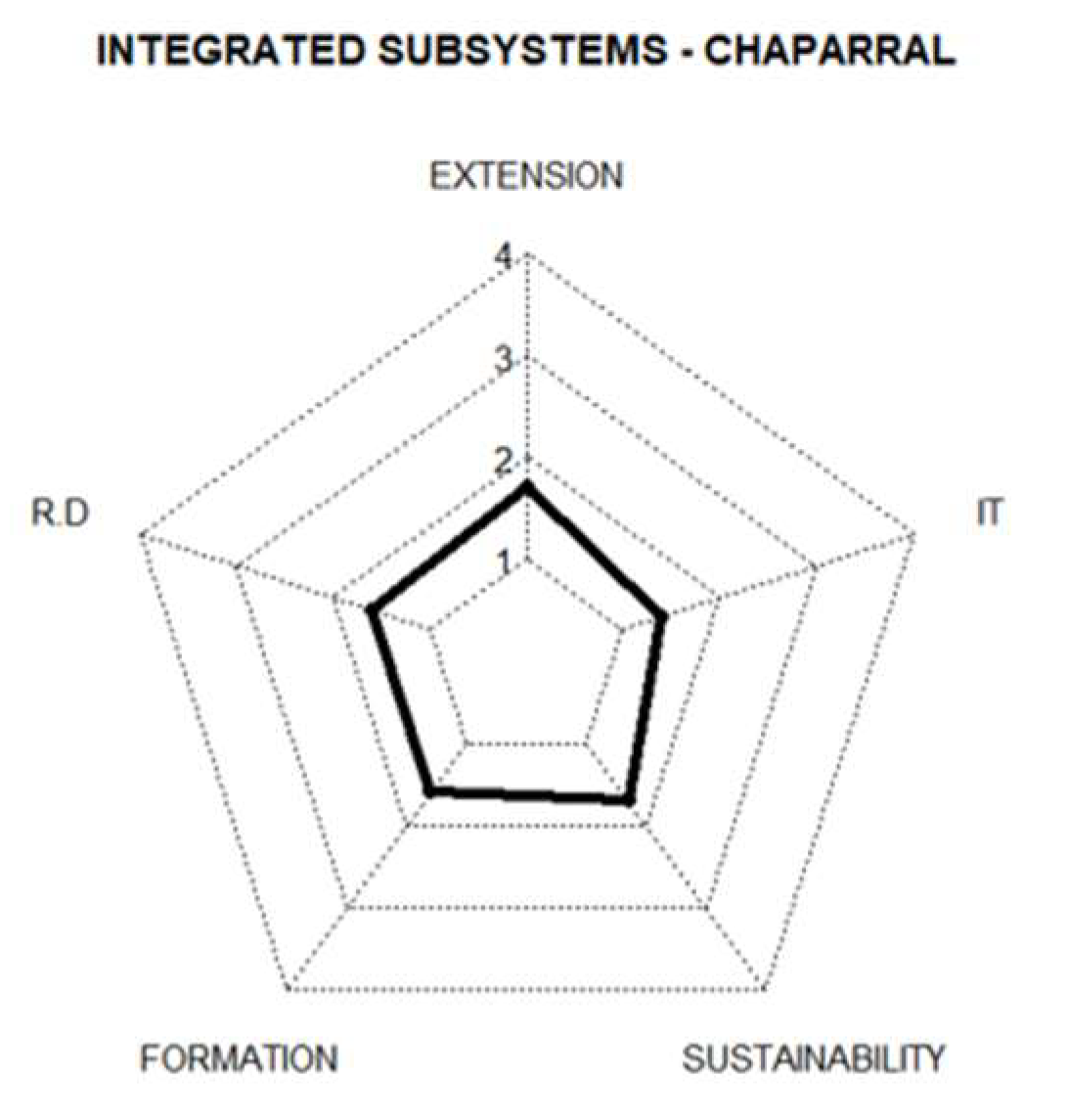

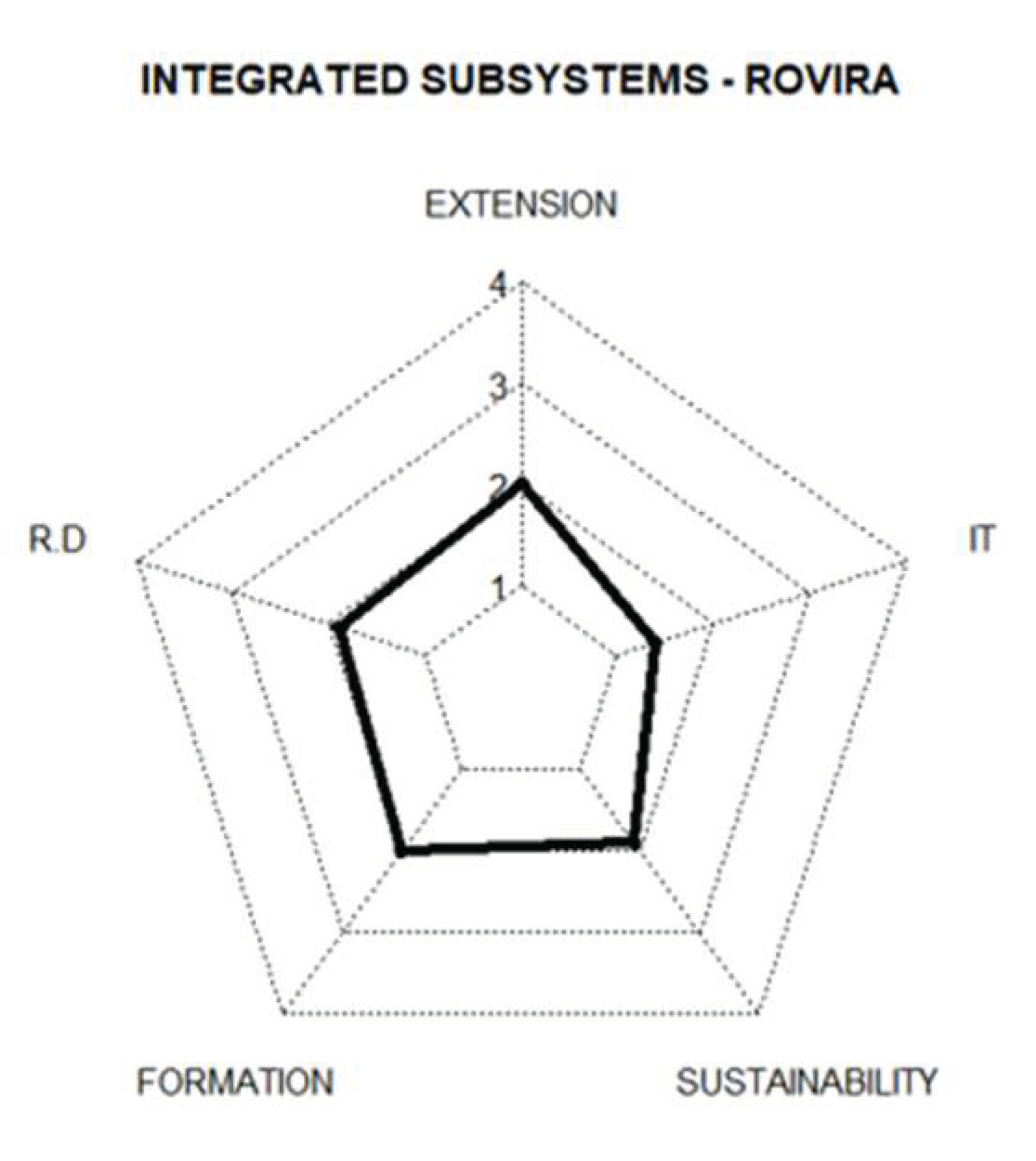

| MUNICIPALITY | EXTENSION | I+D | TRAINING | SUSTAINABILITY | INNOVATION AND ICTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOLÍVAR | |||||

| SAN JUAN NEPOMUCENO | 1,189042745 | 1,498896247 | 1,448675497 | 1,700662252 | 1,221192053 |

| SANTA ROSA DEL SUR | 2,076363636 | 1,9 | 1,463333333 | 2,107333333 | 1,476 |

| CHOCÓ | |||||

| JURADÓ | 1,989964581 | 1,649350649 | 1,998376623 | 1,792207792 | 1,161038961 |

| SAN JOSÉ DEL PALMAR | 1,131515152 | 1,254074074 | 1,275 | 1,566666667 | 1,078666667 |

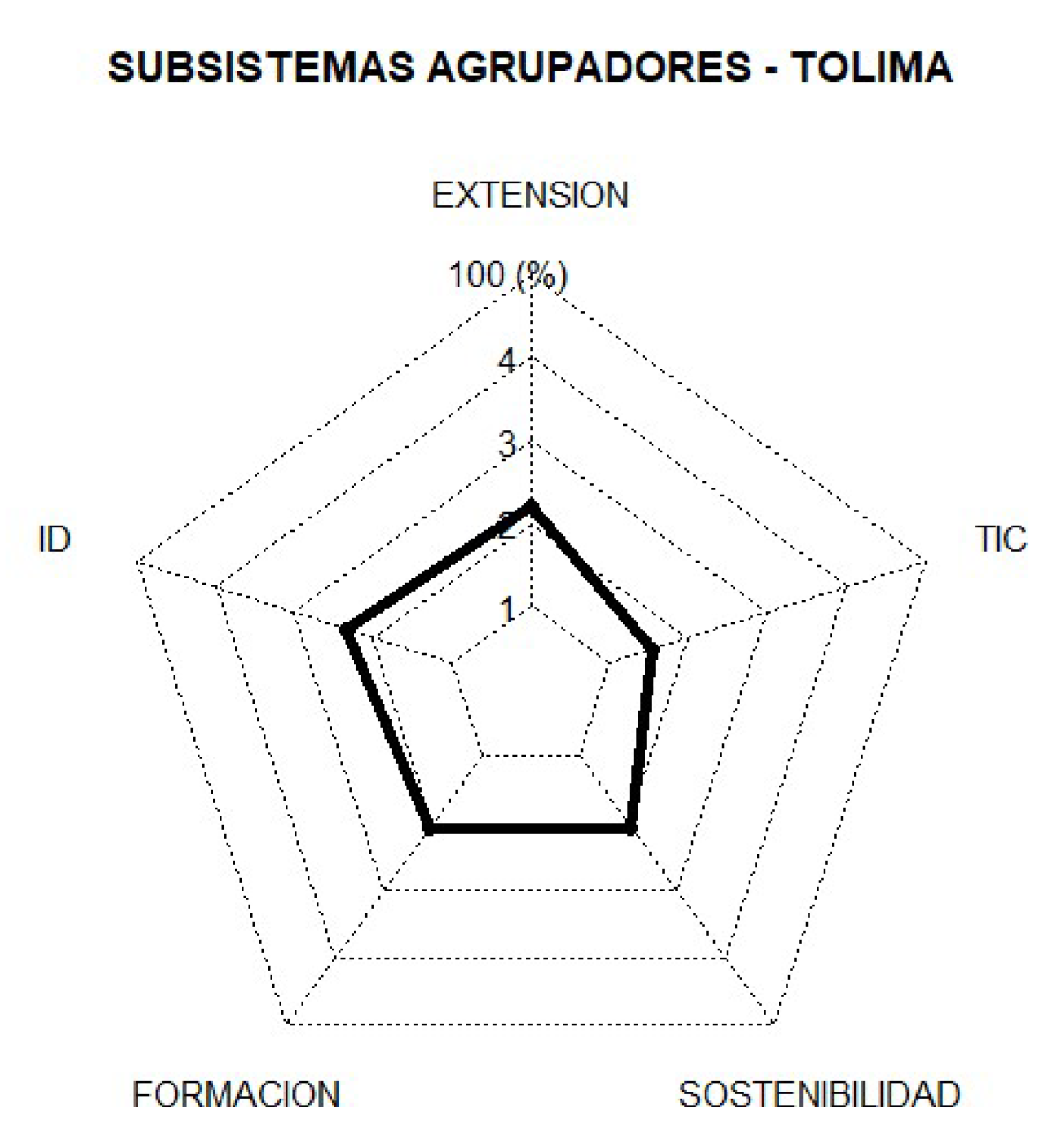

| TOLIMA | |||||

| CABUYARO | 2,209090909 | 2,221481481 | 2,231666667 | 2,148 | 1,785333333 |

| VISTAHERMOSA | 1,38969697 | 1,400740741 | 1,698333333 | 1,702 | 1,225333333 |

| META | |||||

| CHAPARRAL | 1,704848485 | 1,551111111 | 1,55 | 1,655333333 | 1,333333333 |

| ROVIRA | 2,025454545 | 1,991851852 | 2,041666667 | 1,994666667 | 1,366666667 |

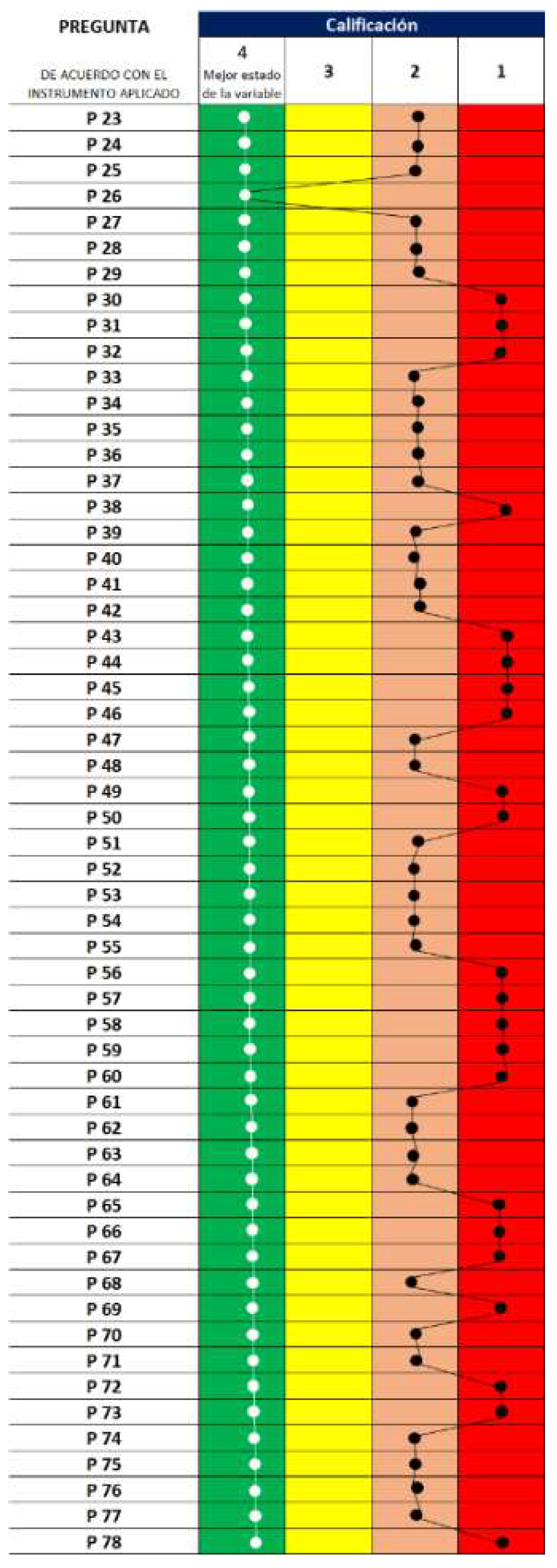

| MUNICIPALITY | P 23 | P24 | P25 | P26 | P27 | P28 | P29 | P30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NATIONAL | 1,312863 | 1,637344 | 2,145228 | 2,701245 | 2,715353 | 2,053112 | 1,629876 | 1,636515 |

| BOLÍVAR | 1,395349 | 1,664452 | 1,903654 | 2,408638 | 2,817276 | 2,431894 | 1,408638 | 1,604651 |

| CHOCÓ | 1,009868 | 1,174342 | 2,082237 | 2,144737 | 2,746711 | 1,565789 | 1,391447 | 1,401316 |

| META | 1,21 | 1,816667 | 2,2 | 2,983333 | 2,646667 | 2,06 | 1,916667 | 1,83 |

| TOLIMA | 1,64 | 1,9 | 2,396667 | 3,276667 | 2,65 | 2,16 | 1,806667 | 1,713333 |

| P31 | P32 | P33 | P34 | P35 | P36 | P37 | P38 | |

| NATIONAL | 1,568465 | 2,020747 | 1,747718 | 1,73029 | 1,870539 | 1,745228 | 1,848133 | 1,808299 |

| BOLÍVAR | 1,44186 | 1,860465 | 1,54485 | 1,531561 | 1,647841 | 1,724252 | 1,564784 | 2,179402 |

| CHOCÓ | 1,552632 | 2,332237 | 1,901316 | 1,582237 | 1,851974 | 1,161184 | 1,769737 | 1,309211 |

| META | 1,673333 | 2,11 | 1,773333 | 1,983333 | 1,906667 | 1,863333 | 2,203333 | 1,813333 |

| TOLIMA | 1,606667 | 1,776667 | 1,77 | 1,826667 | 2,076667 | 2,24 | 1,856667 | 1,936667 |

| P39 | P40 | P41 | P42 | P43 | P44 | P45 | P46 | |

| NATIONAL | 1,777593 | 1,908714 | 1,712863 | 2,024066 | 1,321162 | 1,302075 | 1,612448 | 1,321992 |

| BOLÍVAR | 1,372093 | 1,684385 | 1,700997 | 1,92691 | 1,20598 | 1,189369 | 1,774086 | 1,202658 |

| CHOCÓ | 1,789474 | 1,957237 | 1,559211 | 1,960526 | 1,026316 | 1,006579 | 1,098684 | 1,049342 |

| META | 1,986667 | 2,12 | 1,75 | 2,09 | 1,446667 | 1,45 | 1,86 | 1,55 |

| TOLIMA | 1,963333 | 1,873333 | 1,843333 | 2,12 | 1,61 | 1,566667 | 1,723333 | 1,49 |

| 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | |

| NATIONAL | 1,907884 | 1,841494 | 1,583402 | 1,559336 | 2,082158 | 2,123651 | 1,66971 | 1,73195 |

| BOLÍVAR | 2,046512 | 1,657807 | 1,923588 | 1,568106 | 2,604651 | 2,395349 | 1,754153 | 1,674419 |

| CHOCÓ | 1,940789 | 1,700658 | 1,154605 | 1,279605 | 1,779605 | 2,203947 | 1,444079 | 1,615132 |

| META | 1,943333 | 1,963333 | 1,823333 | 1,823333 | 2,173333 | 2,153333 | 1,613333 | 1,903333 |

| TOLIMA | 1,7 | 2,046667 | 1,436667 | 1,57 | 1,773333 | 1,74 | 1,87 | 1,736667 |

| 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | |

| NATIONAL | 1,627386 | 1,164315 | 1,437344 | 1,19668 | 1,242324 | 1,610788 | 2,050622 | 2,106224 |

| BOLÍVAR | 1,332226 | 1 | 1,614618 | 1,136213 | 1,209302 | 1,780731 | 1,900332 | 2,20598 |

| CHOCÓ | 1,424342 | 0,967105 | 1,026316 | 1,013158 | 1,055921 | 1,539474 | 2,243421 | 1,759868 |

| META | 1,78 | 1,406667 | 1,656667 | 1,42 | 1,48 | 1,563333 | 2,07 | 2,3 |

| TOLIMA | 1,976667 | 1,286667 | 1,456667 | 1,22 | 1,226667 | 1,56 | 1,986667 | 2,163333 |

| P63 | P64 | P65 | P66 | P67 | P68 | P69 | P70 | |

| NATIONAL | 2,229876 | 2,26971 | 1,40332 | 1,562656 | 1,517012 | 1,786722 | 1,19668 | 1,752697 |

| BOLÍVAR | 2,425249 | 2,481728 | 1,428571 | 1,388704 | 1,182724 | 1,421927 | 1,026578 | 1,923588 |

| CHOCÓ | 2,101974 | 2,328947 | 1,154605 | 1,638158 | 1,503289 | 1,950658 | 1,072368 | 1,493421 |

| META | 2,263333 | 2,16 | 1,673333 | 1,656667 | 1,853333 | 2,056667 | 1,436667 | 1,586667 |

| TOLIMA | 2,13 | 2,106667 | 1,36 | 1,566667 | 1,53 | 1,716667 | 1,253333 | 2,01 |

| P71 | P72 | P73 | P74 | P75 | P76 | P77 | P78 | |

| NATIONAL | 1,99751 | 1,379253 | 1,628216 | 1,985892 | 1,950207 | 1,502905 | 2,458921 | 1,721992 |

| BOLÍVAR | 1,887043 | 1,096346 | 1,827243 | 1,933555 | 1,817276 | 1,518272 | 2,48505 | 1,212625 |

| CHOCÓ | 1,914474 | 1,611842 | 1,355263 | 1,9375 | 1,944079 | 1,075658 | 2,404605 | 1,710526 |

| META | 2,09 | 1,5 | 1,763333 | 1,963333 | 2,013333 | 1,596667 | 2,793333 | 2,32 |

| TOLIMA | 2,1 | 1,306667 | 1,57 | 2,11 | 2,026667 | 1,826667 | 2,153333 | 1,646667 |

| Aspect to be assessed | Result analysis |

| 1) Programs for training and universities related to agriculture | The regional innovation systems mapping analysis highlights the concentration of institutions and educational programs in environmental issues and agribusiness, especially in Bolivar and Meta, which implies a strategic focus on sustainable development, collaboration with industry, and specialized training, with the presence of several institutions in Tolima. |

| 2) Main agricultural extension organizations and implementers of agricultural, agro-industrial, and environmental projects | In the analysis of agricultural extension organizations in four departments, Bolívar stands out with 42.20% of the 109 organizations identified due to its size and number of municipalities. In Tolima and Chocó, AGROSAVIA and the Universidad Nacional are leading agricultural and agroindustrial projects, and in Tolima PROTABACO SAS and UNISARC also stand out as executors, with UNISARC focusing on academic areas of rural development and agricultural sciences. |

| 3) Departmental Agenda for Competitiveness and Innovation ADCI - Tolima | In 2020, in Tolima, priority was given to several agricultural and cross-cutting projects, such as value-added coffee, 4.0 technology in livestock, cocoa, and fish agribusiness, as well as initiatives in renewable energy, tertiary roads, competitiveness and innovation, and a technology development center. There is also mention of a dairy agroindustrial facility project in Roncesvalles and Cajamarca. |

| 4) Maps of territorial stakeholders linked to agricultural and rural development | In agricultural and rural development in Tolima, the territorial actors include various components and entities, from the Sectional Council for Agricultural Development to universities, producer associations, and governmental entities such as National Parks, CORTOLIMA, the Governor's Office, and other institutions. |

| 5) Relationship of actors in the agricultural R&D subsystem in the departments of Chocó, Meta, Tolima, and Bolivar. | According to the Departmental Competitiveness Index Tolima, Bolívar, Meta and Chocó [43] have low positions in competitiveness and R&D&I, occupying positions 11 and 12 respectively. Given this, it is crucial to promote projects that drive innovation in the agricultural sector, involving key stakeholders according to the UNCTAD framework and Law 1876 [17]. |

| 6) Research collaboration: Co-authorships and alliances | The territorial distribution of research indexed in Scopus was analyzed, using co-authorships in 42 scientific articles, with Tolima accounting for 47.61% and Meta for 33.33%, and the collaboration of the Nataima Research Center Agrosavia with several institutions in 5 related publications stands out. with agriculture. |

| 7) Exploration of relationships in agricultural patents registered in Colombia | The Lens Patents database was used to analyze the relationships in Colombian agricultural patents utilizing keyword search equations, obtaining 50 registered patents. Although there were no collaborative patents in the four departments studied, institutional relationships and international collaborations were found in the ownership of agricultural patents in Colombia. |

| 8) Analysis of project profiles registered with the Rural Development Agency [44]- | In the analysis of project profiles registered with the Rural Development Agency during 2020, Tolima leads with 44.44% participation, followed by Meta with 22.22%. The livestock sector is prominent in the profiles (13.46%), followed by coffee and poultry (9.61%). Stakeholders include small producers, indigenous reserves, Afro-descendant families, production chains, and families, showing collaboration in the formulation of the profiles. |

| 9) Projects under implementation and executed financed by various sources | The analysis of projects executed and to be executed with various sources of financing shows that Tolima leads in comparison with Chocó and Bolívar, addressing areas such as planting material, genetic improvement, sanitary management, soil and water management, and geographic information systems, with frequent participation of entities such as AGROSAVIA, UNAL, CIB, Universidad del Tolima, UTP, PROTABACO SAS and UNISARC, among others. |

| 10) Optimizing the relationship between financing and government in the General Royalties System | The analysis of the relationship of entities and territories with the General Royalties System as a source of financing in Agriculture and CTeI reveals that Chocó and Bolívar have the best relationship, with more than 440 thousand and 417 billion Colombian pesos, respectively, while Tolima has the lowest relationship, with 191 billion. Tolima leads the execution of projects financed by the SGR in Agriculture and Rural Development, addressing issues such as rural housing, coffee, livestock, cocoa, sanitary units, and fish farming. |

| 11) Overview of SGR resources for CTeI | Regarding SGR resources for CTeI, the outstanding relationship of the two departments with the SGR's CTeI Fund stands out: Bolivar leads with 29 projects (31.52%) and Tolima follows with 27 projects (29.34%) of the 92 projects financed. |

| 12) Public investment projects financed with resources from the General Royalties System - SGR (2022) | The financing resources of the SGR's CTeI Fund for the 4 Departments are observed with Bolivar leading (44.18%) and Chocó (29.63%). In Tolima, projects CTeIare being executed with $130,268,736,977, focusing on training, the Sheep and Goat Chain, CyTCapacities, and Cocoa, with outstanding participation of the Government, the University of Tolima and Agrosaviain their execution. It is also noted that the SGR's CTeI Fund has helped finance Tolima projects in different agricultural products, such as avocado, and coffee, among others. |

| 13) Analysis of associations, cooperatives, agricultural, and related foundations in the regions. | In the analysis of associations, cooperatives, agricultural foundations, and similar in the region, Meta leads in associativity with 294 entities (39.72% of the total), followed by Tolima with 242 organizations (72.43% of the four territories). In Tolima, associations predominate (92.56%), and there is a greater presence of foundations compared to Meta. |

| 14) Analysis of the relationship between associations or cooperatives and other entities | The news analysis shows that the relationship between associations and cooperatives has been mainly with state entities such as the Ministries of Agriculture and Rural Development, Governors' Offices, ICBF, and Mayors' Offices, as well as with NGOs and foundations for knowledge transfer, training, productivity improvement, certification. food supply, dissemination of results, and financing. |

| 15) Analysis of cluster initiatives (agricultural and related) in the regions of interest | A cluster is a geographic concentration of companies and entities related to similar activities, intending to foster competitive cooperation to improve quality, reduce costs, and increase productivity and profitability. Bolivar, Meta, and Tolima have 2 registered agricultural clusters, while Chocó has none. The initiatives arise from the Regional Commission for Competitiveness and Innovation with the support of the Chambers of Commerce. In the department of Tolima, there is information on a cluster initiative registered for the cocoa agrifood chain and an initiative for the specialty coffee subsector. |

| 16) Cabildos and Indian Reservations | The Cabildos and reservations are forms of association that legally represent indigenous communities, and the reservations are territorial divisions that guarantee ownership over customary inhabited territories. Of these, 251 were identified in the four Departments, with Chocó standing out with 55.4% and Tolima with 32.6% of the communities grouped. |

| 17) Relationships between research groups and institutions in Colombia - agro and related groups in the regions | According to the database of the Ministry of Science Technology and Innovation of Colombia, in the call for recognition of research groups (Call 833 of 2018) between 2018 and 2019, 20 groups were identified in the 4 territories analyzed in the area of agriculture and related areas. The department of Meta has the most recognized groups (10), followed by Tolima (8) and Chocó (2), while Bolívar reports no groups in these areas. Groups such as the Agroforestry Livestock Systems Research Group of the University of Tolima and Conservation Agriculture for Low Tropic Soils of Agrosavia Meta show opportunities for collaboration in the science, technology, and innovation system. |

| 18) Technoparks in the regions and Technology Transfer Offices OTRIS | In the regions analyzed (Chocó, Bolívar, Tolima, and Meta), only one Tecnoparque SENA was found in the Department of Tolima, and no technology transfer offices or corporations were found in any of the territories. Although some universities have Research Results Transfer Offices (OTRIS), they focus on internal transfer. Despite the lack of OTRIS, the regions can access services from other nearby OTRIS, such as Reddi in Cali, CONNECT in Bogota, OTRI Estratégica de Oriente in Bucaramanga and CIENTECH in Barranquilla. |

| 1. Collaboration Articles scientific articles | |||||

| Department | Population |

No. Articles co-authorship |

No. Articles in.Co-authorship Co-authorship about population. |

Score max.Score max. |

Score Co-authorships articles |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 20 | 0,00001493 | 5 | 5,00 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 14 | 0,00001328 | 5 | 4,45 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 5 | 0,00000235 | 5 | 0,79 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 2 | 0,00000364 | 5 | 1,22 |

| 1. Collaboration Patents | |||||

| Department | Population |

No. Patents collaboration |

No. Patents in Collaboration with the Population | Score max.Score max. |

Score patents in collaboration |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 0 | 0,00000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 0 | 0,00000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 0 | 0,00000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 0 | 0,00000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| 2. Profiles of projects enrolled 2020 Agency of Development Rural | |||||

| Department | Population | No. Profiles of projects enrolled >2020 Agency of Development Rural |

No. Profiles of projects registered. 2020 Agency de Development Rural about population |

Score max.Score max. |

Score profiles of projects registered projects |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 24 | 0,00001791 | 5 | 5,00 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 12 | 0,00001139 | 5 | 3,18 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 10 | 0,00000469 | 5 | 1,31 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 8 | 0,00001457 | 5 | 4,07 |

| 3. Resources from financing SGR Fund from Agriculture and Development Rural | |||||

| Department | Population |

Resources de Financing SGR Funding from Agriculture and rural development |

Resources of SGR financing Funding from Agriculture and Development Rural population |

Score max.Score max. | Score profiles of projects registered projects |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | $61.110.810.603 | $45.605 | 5 | 0,53 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | $180.529.116.126 | $171.301 | 5 | 1,98 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | $115.850.589.338 | $54.390 | 5 | 0,63 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | $238.007.380.716 | $433.351 | 5 | 5,00 |

| 4. Resources obtained from the CTeI Fund of the SGR by the Department | |||||

| Department | Population |

Recursos obtenidos del Fondo de CTeI del SGR por Department |

Recursos obtenidos del Fondo de CTeI del SGR por Departamento Overpopulation |

Score max.Score max. | Score profiles of projects registered projects |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | $130.268.736.977 | $97.216 | 5 | 1,32 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | $48.500.999.471 | $46.022 | 5 | 0,62 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | $301.768.778.749 | $141.675 | 5 | 1,92 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | $202.385.840.265 | $368.493 | 5 | 5,00 |

| 5. Agricultural and related associations, cooperatives, foundations | |||||

| Department | Population | Asociaciones, cooperativas y fundaciones agrícolas | Asociaciones, cooperativas y fundaciones agrícolas about population. | Score max.Score max. | Puntaje Asociaciones, cooperativas y fundaciones agrícolas |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 242 | 0,0001806 | 5 | 3,24 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 294 | 0,0002790 | 5 | 5,00 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 153 | 0,0000718 | 5 | 1,29 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 51 | 0,0000929 | 5 | 1,66 |

| 6. Agricultural and related cluster initiatives | |||||

| Department | Population | Iniciativas Clúster (agrícolas y afines) | Iniciativas Clúster (agrícolas y afines) sobre población | Score max.Score max. |

Puntaje iniciativas Clúster (agrícolas y afines) |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 2 | 0,0000015 | 5 | 3,93 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 2 | 0,0000019 | 5 | 5,00 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 2 | 0,0000009 | 5 | 2,47 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| 7. Cabildos and Indigenous reserves | |||||

| Department | Population | Cabildos and Indigenous reserves | Cabildos and Indigenous reserves about population. | Score max.Score max. | Score Cabildos and Indigenous reserves |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 82 | 0,0000612 | 5 | 1,21 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 20 | 0,0000190 | 5 | 0,37 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 10 | 0,0000047 | 5 | 0,09 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 139 | 0,0002531 | 5 | 5,00 |

| 8. No. Research groups in agriculture and related areas | |||||

| Department | Population | No. Grupos de Investigación en agricultura y afines | No. Grupos de Investigación en agricultura y afines about population. | Score max.Score max. |

Score No. Grupos de Investigación en agricultura y afines |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 8 | 0,0000060 | 5 | 3,15 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 10 | 0,0000095 | 5 | 5,00 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 2 | 0,0000036 | 5 | 1,92 |

| 9. Technoparks | |||||

| Department | Population | No. Technoparks. |

No. Technoparks. about population. |

Score max.Score max. | Score Technoparks |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 1 | 0,0000007 | 5 | 5,00 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| 10. Offices of Transfer Technological and Results of Research OTRIS. | |||||

| Department | Population | Offices from Transfer Technological OTRIS |

Offices of Transfer Technology OTRIS about population. |

Score max.Score max. |

Score Offices de Transfer Technological OTRIS |

| Tolima | 1.339.998 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Meta | 1.053.871 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Bolívar | 2.130.000 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Chocó | 549.225 | 0 | 0,0000000 | 5 | 0,00 |

| Results variable assessment of relationship System National of CTeI on Agriculture and related | |||||

| Department | Weightingaverage | ||||

| Tolima | 2,58 | ||||

| Meta | 2,33 | ||||

| Chocó | 2,17 | ||||

| Bolívar | 0,77 | ||||

| 1. TOLIMA. - Main gaps obtained | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extension | I+D | Sustainability | Training | Innovation and ICTs |

|

Technical assistance from a private individual/state/guild to provide agricultural extension services to their productive units. AVERAGE: 1.7 MODE: 1 |

Presence of people directly involved in R&D processes. AVERAGE: 1.2 MODE: 1 |

Participation in the development of innovation-based sustainability. AVERAGE: 1.6 MODE: 1 |

Projects that through planning, implementation, financing, and evaluation of training and qualification actions directly implement the R&D&I process in the productive unit. AVERAGE: 1.5 MODE: 1 |

People directly involved in R&D&I activities. |

| GAP: Does not have technical assistance in its productive unit. | GAP: Your production unit has NO people directly involved in R&D&I activities and in establishing strategic alliances with interest groups. | GAP: No active participation of stakeholders in the development of sustainability based on innovation. | GAP: No knowledge of projects related to training and capacity building. | GAP: There are NO people directly involved in R&D and innovation activities and in establishing strategic alliances with |

|

HIGHEST RATING: It has technical assistance from the following three actors/agents: individuals/state/guilds to provide agricultural extension services to their production unit. |

HIGHEST QUALIFICATION: The production unit has people directly involved in R&D&I activities and is establishing strategic alliances with interest groups. | HIGHEST RATING: Active stakeholder participation in the development of innovation-based sustainability is present and sufficient. | MAXIMUM QUALIFICATION: Knows the projects and considers that they have planned, implemented, financed, and evaluated training and capacity-building actions that directly impact the R&D&I process in its productive unit. | HIGHEST RATING: There are people directly involved in R&D&I activities and establishing strategic alliances with interest groups. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).