Submitted:

03 March 2024

Posted:

04 March 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of Plant-Based in Reducing Incidence, Severity, and Mortality of COVID-19

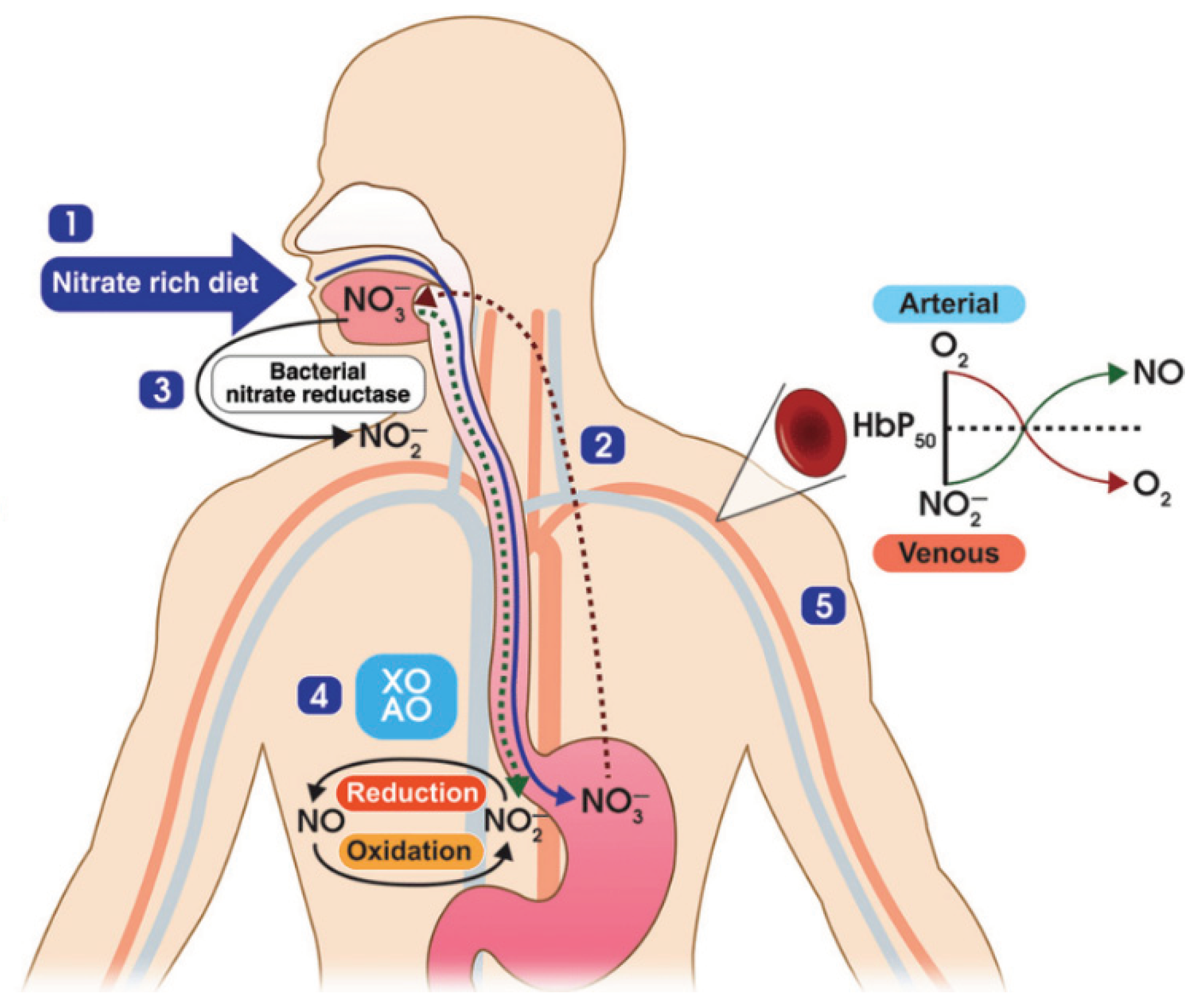

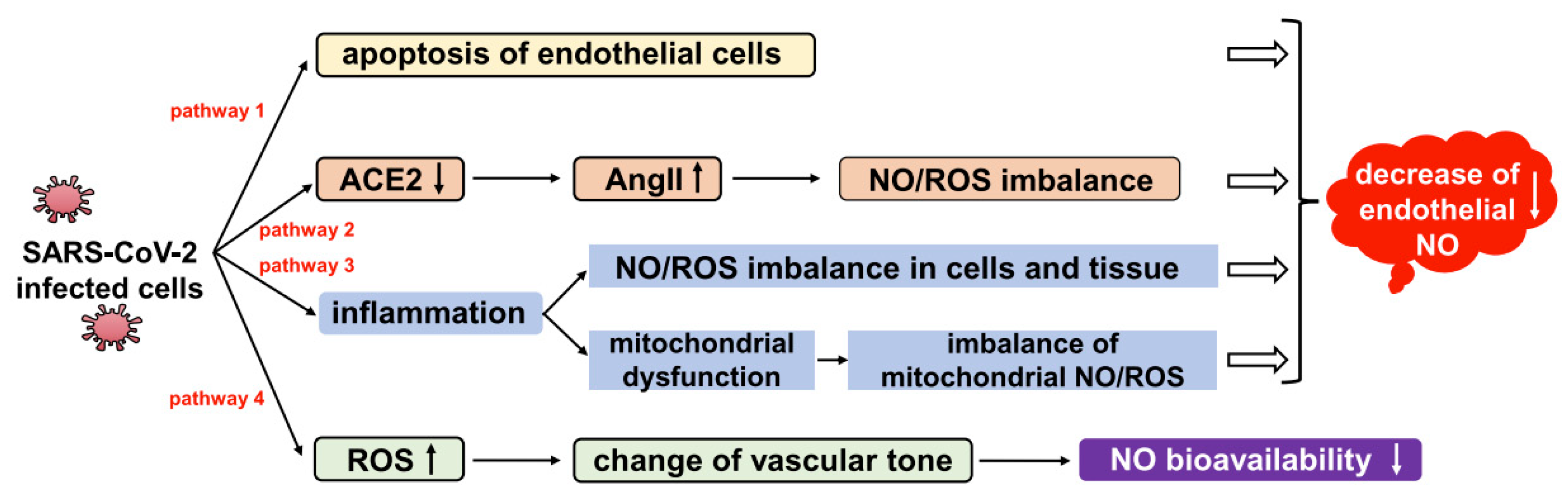

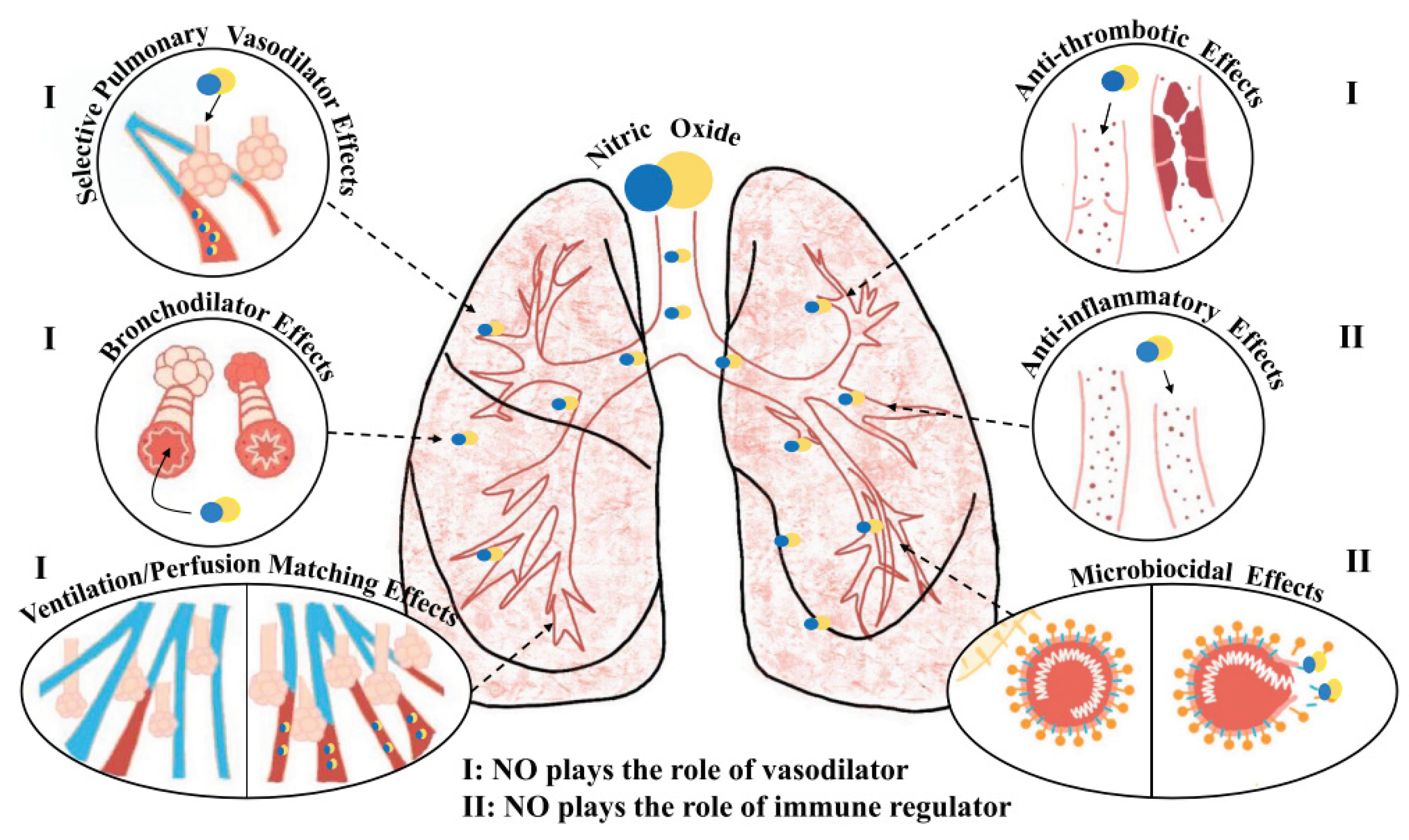

2.1. Mechanism of Nitric Oxide in Fighting COVID-19

2.2. The Connection between Microbiota and COVID-19

2.3. The Role of Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction in COVID-19

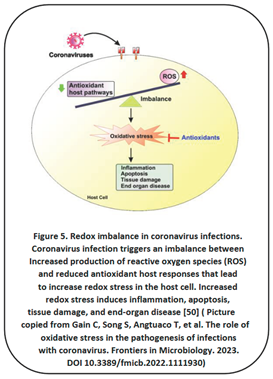

2.4. Oxidative Stress Plays a Crucial Role in COVID-19 Infection

2.5. The Link between Mitochondria Health and COVID-19 Severity and Mortality

2.6. Potential Benefits of Telomere Manipulation in COVID-19 Treatment

2.7. Caloric Restriction Is Emerging as an Essential Factor in the Fight against Inflammation

3. Supplements Their Significant Role in Managing COVID-19

3.1. Vitamin C

3.2. Vitamin D

3.3. Vitamin B3, Precursor of NAD+

3.4. Zinc

3.5. Copper

3.6. Selenium

3.7. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

3.8. Astaxanthin

3.9. Quercetin

3.10. Curcumin

3.11. Taurine

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

References

- Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive Lifestyle Changes for Reversal of Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA. 1998; 280:23. [CrossRef]

- Esselstyn CB, Jr. Updating a 12-year experience with arrested reversal therapy for coronary heart disease (an overdue requiem for palliative cardiology). Am J Cardiol. 1999; 84(3):339-41. [CrossRef]

- Peña-Jorquera H, Cid-Jofré V, Landaeta-Diaz L, et al. Plant-Based Nutrition: Exploring Health Benefits for Atherosclerosis, Chronic Diseases, and Metabolic Syndrome- A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients; 2023; 15:3244. [CrossRef]

- Oboza P, Ogarek N, Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, et al. The main causes of death in patients with COVID-19. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023; 27(5):2165-2172. [CrossRef]

- Dessie ZG, Zewotir T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021; 21:855. [CrossRef]

- Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2016; 928. [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka K, Skrzypczak D, Izydorczyk G, et al. Antiviral Properties of Polyphenols from Plants. Foods. 2021; 10:2277. [CrossRef]

- Alesci A, Aragona M, Cicero N, et al. Can nutraceuticals assist treatment and improve covid-19 symptoms? Natural Product Research. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Alam S, Sarker Md MR, Afrin S. Traditional Herbal Medicines, Bioactive Metabolites, and Plant Products Against COVID-19: Update on Clinical Trials and Mechanism of Actions. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021; 12:671498. [CrossRef]

- Loscalzo J, Welch G. Nitric Oxide and its role in cardiovascular system. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995; 38(2):87-104. [CrossRef]

- Cannon 3rd RO. Role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular disease: focus on the endothelium. Clin Chem. 1998; 44(8Pt2):1809-19 [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torregrossa AC, Aranke M, Bryan NS. Nitric Oxide and geriatrics: Implications in diagnostics and treatment of the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2011; 8(4):230-242. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis A, Kramer R, Ostojic S. Nitric Oxide: The Missing Factor in COVID-19 Severity? Med Sci (Basel). 2022; 10(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Flaxman S, Whittaker C, Semenova E, et al. Assessment of COVID-19 as the Underlying Cause of Death Among Children and Young People Aged 0 to 19 Years in the US. 2023; 6(1):e2253590. [CrossRef]

- Babateen A, Shannon O, Mathers JC, et al. Validity and reliability of test strips for the measurement of salivary nitrite concentration with and without the use of mouthwash in healthy adults. Nitric Oxide. 2019; 91(5). [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi J, Ohtake K, Uchida H. NO-Rich Diet for Lifestyle-Related Diseases. Nutrients. 2015; 7(6):4911-4937. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran S, Shen X, Glawe JD, et al. Nitric Oxide and Hydrogen Sulfide Regulation of Ischemic Vascular Growth and Remodeling. Chapter in Comprehensive Physiology. 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333740265.

- Fang W, Jiang J, Su L, et al. The role of NO in COVID-19 and potential therapeutic strategies. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2021; 163:153-162. [CrossRef]

- Ritz T, Trueba AF, Vogel PD, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide and vascular endothelial growth factor as predictors of cold symptoms after stress. Biol Psychol. 2018;132:116-124. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani JS, Aldhahir AM, Al Ghamdi SS, et al. Inhaled Nitric Oxide for Clinical Management of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Public Health. 2022; 19(19);12803. [CrossRef]

- Mir JM, Maurya RC. Nitric oxide as a therapeutic option for COVID-19 treatment: a concise perspective. New J Chem. 2021; 45:1774. [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Garssen J, et al. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients. 2021; 13(3):886. [CrossRef]

- Dumas A, Bernard J, Poquet Y, et al. The role of the lung microbiota and the gut-lung axis in respiratory infectious diseases. Cell Microbiol. 2018; 20:e12966. [CrossRef]

- Vijay A, Valdes AM. Role of the gut microbiome in chronic diseases: a narrative review. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022; 76:489-501. [CrossRef]

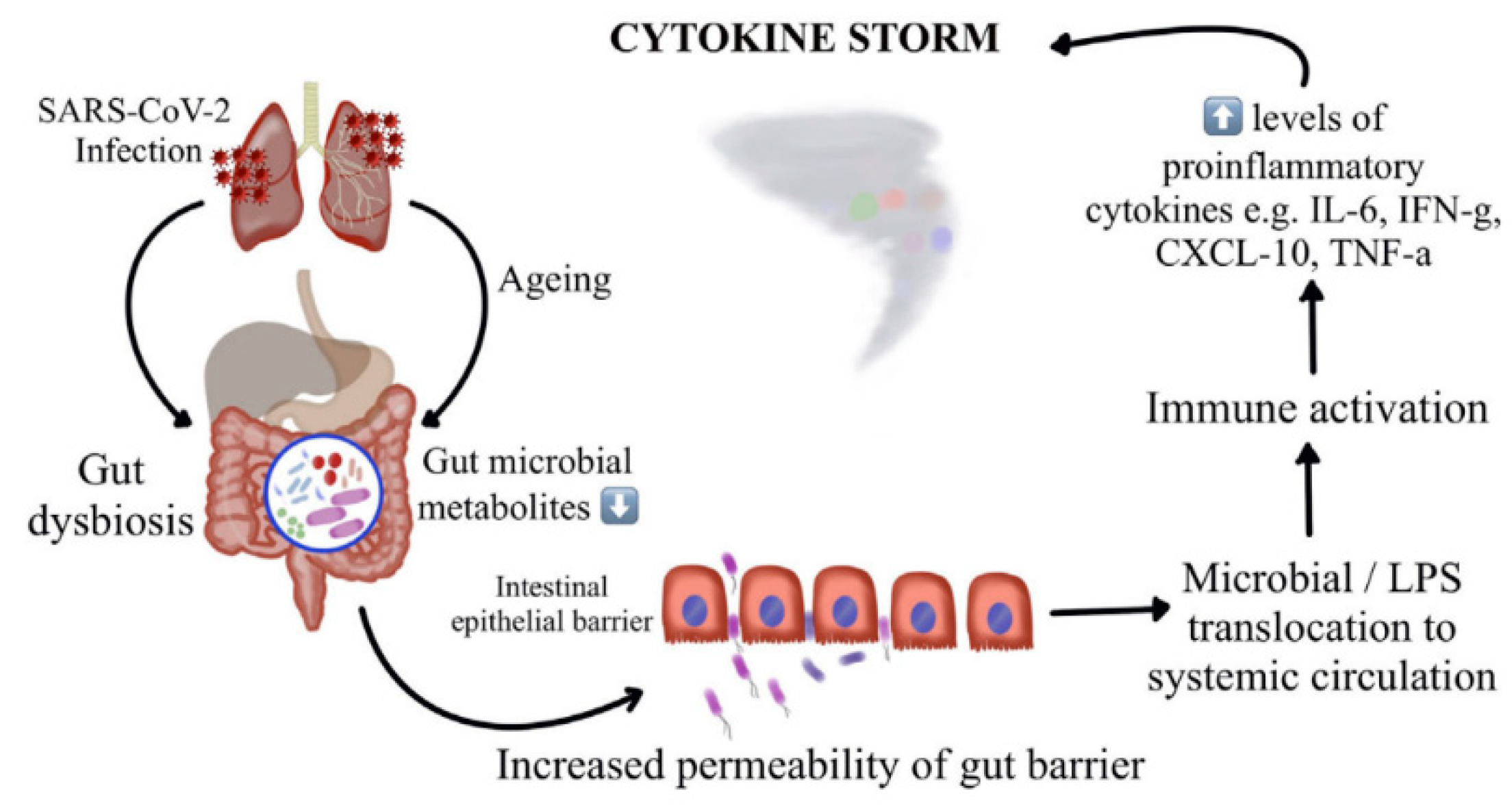

- Vignesh R, Swathirajan CR, Tun Z-H, et al. Could Perturbation of Gut Microbiota Possibly Exacerbate the Severity of COVID-19 via Cytokine Storm? Frontiers in Immunology. 2021; 11:607734. [CrossRef]

- Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DLA, et al. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017; 15:55-63. [CrossRef]

- Dang At, Marsland BJ. Microbes, metabolites, and gut-lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019; 12:843-50. [CrossRef]

- Ramatillah DL, Gan S-H, Pratiwi I, et al. Impact of cytokine storm on severity of COVID-19 disease in a private hospital in West Jakarta prior to vaccination. PloS One. 2022; 17(1): e0262438. [CrossRef]

- Du R-H, Liang L-R, Yang C-Q, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020; 56:3. [CrossRef]

- Groves HT, Higham SL, Moffatt MF, et al. Respiratory Viral Infection Alters the Gut Microbiota by Inducing Inappetence. mBio. 2020; 11:1. [CrossRef]

- Gou W, Fu Y, Yue L, et al. Gut microbiota may underlie the predisposition of healthy individuals to COVID-19. MedRxiv. 2020; 04.22:20076091. [CrossRef]

- Vignesh R, Swathirajan CR, Tun Z-H, et al. Could Perturbation of Gut Microbiota Possibly Exacerbate the Severity of COVID-19 via Cytokine Storm? Frontiers in Immunology. 2021; 11:607734. [CrossRef]

- Abadi MSS, Kodashahi R, Aliakbarian M, et al. The Association Between the Gut Microbiome and COVID-19 Severity: The Potential Role of TMAO Produced by the Gut Microbiome. Archives of Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2024; 18(6):e140346. [CrossRef]

- Foster JA, Baker GB, Dursun SM. The Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome- Immune System-Brain Axis and Major Depressive Disorder. Front Neurol. 2021; 12:721126. [CrossRef]

- Kamo T, Akazawa H, Suda W, et al. Dysbiosis and compositional alterations with aging in the gut microbiota of patients with heart failure. PloS One. 2017; 12 (3):e0174099. [CrossRef]

- Leeming ER, Johnson AJ, Spector TD, et al. Effect of Diet on the Gut Microbiota: Rethinking Intervention Duration. Nutrients. 2019; 11(12):2862. [CrossRef]

- Craddock JC, Neale EP, Peoples GE, et al. Vegetarian-Based Dietary Patterns and their Relation with Inflammatory and Immune Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in Nutrition. 2019; 10(3):433-451. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu SRK, Kok C-W, Kunasegaran T, et al. Effect of Plant-Based Diets on Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Interventional Studies. Nutrients. 2023; 15:1510. [CrossRef]

- Hibino S, Hayashida K. Modifiable Host Factors for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19: Diet and Lifestyle/ Diet and Lifestyle Factors in the Prevention of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2022; 14:1876. [CrossRef]

- Dovignoan J, Ganz P. Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004; 109:III-27-III-32. [CrossRef]

- Akinrinmade AO, Obitulata-Uqwu VO, Obijiofor NB, et al. COVID-19 and Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2022; 14(9):e29747. [CrossRef]

- Margina D, Ungurianu A, Purdel C, et al. Chronic Inflammation in the Context of Everyday Life: Dietary Changes as Mitigating Factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(11): 4135. [CrossRef]

- Hojyo S, Uchida M, Tanaka K, et al. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm Regen. 2020; 40:37. [CrossRef]

- Moludi J, Qaisar SA, Alizadeh M, et al. The relationship between Dietary Inflammatory Index and disease severity and inflammatory status: a case-control study of COVID-19 patients. British Journal of Nutrition. 2021: 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Wirth MD, Petermann-Rocha F, et al. Diet-Related Inflammation Is Associated with Worse COVID-19 Outcomes in the UK Biobank Cohort. Nutrients. 2023; 15:884. [CrossRef]

- Paraiso IL, Revel JS, Stevens JF. Potential use of polyphenols in the battle against COVID-19. Current Opinion in Food Science. 2020; 32:149-155. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Uffelman C, Hill E, et al. The Effects of Red Meat Intake on Inflammation Biomarkers in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022; 6(Suppl 1):994. [CrossRef]

- Hofseth LJ, Hébert JR. Chapter 3- Diet and acute and chronic, systemic, low-grade inflammation. Diet, Inflammation, and Health. 2022:85-111. [CrossRef]

- Buck AN, Vincent HK, Newman CB. Et al. Evidence-Based Dietary Practices to Improve Osteoarthritis Symptoms: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(13):3050. [CrossRef]

- Gain C, Song S, Angtuaco T, et al. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of infections with coronavirus. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Zhu D, Yang J, et al. Clinical treatment experience in severe and critical COVID-19. Mediat Inflamm. 2021:9924542. [CrossRef]

- Alam MS, Czajkowsky DM. SARS-CoV-2 infection and oxidative stress: pathophysiology insight into thrombosis and therapeutic opportunities. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2022; 63:44-57. [CrossRef]

- Gorni D, Finco A. Oxidative stress in elderly population: A prevention screening study. Aging medicine. 2020; 3:205-213. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, J. SARS-CoV-2 associated COVID-19 in geriatric population: A brief narrative review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021; 28(1):738-743. [CrossRef]

- Macho-Gonzáles A, Garcimartín A, López-Oliva ME, et al. Can Meat and Meat-Products Induce Oxidative Stress? Antioxidants. 2020; 9:638. [CrossRef]

- Macho-Gonzáles A, Bastida S, Garcimartín A, et al. Functional Meat Products as Oxidative Stress Modulators: A Review. Advances in Nutrition. 2021; 12(4):1514-1539. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova K, Koelman L, Rodrigues CE. Dietary patterns and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation: A systematic review of observational and intervention studies. Redox Biology. 2021; 42:101869. [CrossRef]

- Baghaei-Yazdi N, Bahmaie M, Abhari FM. The Role of plant-derived natural antioxidants in reduction of oxidative stress. BioFactors. 2022:1-23. [CrossRef]

- Marchi S, Guilbaud E, Galluzzi L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2023; 23:159-173. [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli G, Conte S, Cimmino G, et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Hidden Player in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis? Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24:1086. [CrossRef]

- Shoraka S, Samarasinghe AE, Ghaemi A, et al. Host mitochondria: more than an organelle in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Junqueira C, Crespo A, Lieberman J, et al. FcyR-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection of monocytes activates inflammation. Nature. 2022; 606:576-584. [CrossRef]

- Khalil M, Shanmugam H, Abdallah H, et al. The Potential of the Mediterranean Diet to Improve Mitochondrial Function in Experimental Models of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients. 2022; 14:3112. [CrossRef]

- Pollicino F, Veronese N, Dominguez L, et al. Mediterranean diet and mitochondria: New findings. Experimental Gerontology. 2023; 176:112165. [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis ID, Vassi E, Alvanou M, et al. The impact of diet upon mitochondrial physiology (Review). International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2022; 50:135. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Miniño A, et al. Provisional Mortality Data- United States, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2021, 70, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance – United States, January 22-May 30,2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(24):759-765.

- Wang Q, Zhan Y, Pederson NL, et al. Telomere length and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2018; 48:11-20. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vazquez R, Guío-Carrión A, Zapatero-Gaviria A, et al. Shorter telomere lengths in patients with severe COVID-19 disease. Aging (Albany NY). 2021; 13(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodpoor A, Sanale S, Eskandari M, et al. Association between leucocyte telomere length and COVID-19 severity. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2023; 24(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Retuerto M, Liedó A, Fernandez-Varas B, et al. Shorter telomere length is associated with COVID-19 hospitalization and with persistence of radiographic lung abnormalities. Immunity & Ageing. 2022; 19:38. [CrossRef]

- Arantes dos Santos G, Pimenta R, Viana NI, et al. Shorter leukocyte telomere length is associated with severity of COVID-19 infection. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports. 2021; 27:101056. [CrossRef]

- Aviv, A. The bullwhip effect, T-cell telomeres, and SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2022; 3(10):E715-E721. [CrossRef]

- Sepe S, Rossiello F, Cancila V, et al. DNA damage response at telomeres boosts the transcription of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 during aging. EMBO rep. 2022; 23(2):e53658.

- Liu S, Nong W, Ji L, et al. The regulatory feedback of inflammatory signaling and telomere/telomerase complex dysfunction in chronic inflammatory disease. Experimental Gerontology. 2023; 174:112132.

- Crous-Bou M, Molinuevo J-L, Sala-Vila A. Plant-Rich Dietary Patterns, Plant Foods and Nutrients, and Telomere Length.Adv Nutr. 2019; 10(Suppl_4):S286-S303.

- D’Angelo, S. Diet and Aging: The Role of Polyphenol-Rich Diets in Slow Down the Shortening of Telomeres: A Review. 2023; 12(12):2086. [CrossRef]

- Blackburn E, Epel E. The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer. Grand Central Publishing. 2017.

- Kökten T, Hansmannel F, Ndiaye NC, et al. Calorie Restriction as a New Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. Adv Nutr. 2021; 12(4):1558-1570. [CrossRef]

- Gnoni M, Beas R, Vásques-Garagatti. Is there any role of intermittent fasting in the prevention and improving clinical outcomes of COVID-19?: intersection between inflammation, mTOR pathway, autophagy and caloric restriction. VirusDis. 2021; 32(4):625-634. [CrossRef]

- Horne BD, May HT, Muhlestein JB, et al. Association of periodic fasting with lower severity of COVID-19 outcomes in the SARS-CoV-2 prevaccine era: an observational cohort from the INSPIRE registry. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. 2022; 0:eooo462. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, RZ. Can early and high intravenous dose of vitamin C prevent and treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID_19)? Med Drug Discov. 2020; 5:100028. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Hu C, Hood M, et al. A novel combination of vitamin C, curcumin and glycyrrhizin acid potentially regulates immune and inflammatory response associated with coronavirus infections: a perspective from system biology analysis. Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):1193. [CrossRef]

- Marik PE, Khangoora V, Rivera R, et al. Hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective before-after study. Chest. 2017; 151(6):1229-1238. [CrossRef]

- Kow S-K, Hasan SS, Ramachandram DS. The effect of vitamin C on the risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflammopharmacology. 2023; 18:1-6. [CrossRef]

- Olczak-Pruc M, Swieczkowski D, Ladny JR, et al. Vitamin C Supplementation for the Treatment of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(19):4217. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020; 130:2620-9. [CrossRef]

- Fisher SA, Rahimzadeh M, Brierley C, et al. The role of vitamin D in increasing circulating T regulatory cell numbers and modulating T regulatory cell phenotypes in patients with inflammatory disease or in healthy volunteers: A systematic review. PloS One. 2019; 14:e0222313. [CrossRef]

- Giannis D, Ziogas IA, Gianni P. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020; 127:104362. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad S, Mishra A, Ashraf MZ. Emerging role of Vitamin D and its associated molecules in pathways related to pathogenesis of thrombosis. Biomolecules. 2019; 9:649. [CrossRef]

- Weir EK, Thenappan T, Bhargaya M, et al. Does vitamin D deficiency increase the severity of COVID-19?. Clin Med (Lond). 2020; 20(4):e107-e108. [CrossRef]

- D’Ecclesiis O, Gavioli C, Martinoli C, et al. Vitamin D and SARS Cov-2 infection, severity and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022; 17(7): e0268396. [CrossRef]

- Meng J, Li X, Lie W, et al. The role of vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Nutrition. 2023; 42:2198-2206. [CrossRef]

- Bogan KL, Brenner C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008; 28:115-130. [CrossRef]

- Zheng M, Schultz MB, Sinclair DA. NAD+ in COVID-19 and viral infections. Trends in Immunology. 2022; 43(4):283-295. [CrossRef]

- Bogan-Brown K, Nkrumah-Elie Y, Ishtiaq Y, et al. Potential Efficacy of Nutrient Supplements for Treatment of Prevention of COVID-19. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2022; 19(3):336-365. [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif M, Bugger H, Kroemer G, et al. NAD+ and Vascular Dysfunction: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2022; 11(2):111-132. [CrossRef]

- Abdallah SB, Mhalla Y, Trabelsi I, et al. Twice-Daily Oral Zinc in the treatment of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized Doble- Blind Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2023; 76(2):185-191.

- Olczak-Pruc M, Szarpak L, Navolokina A, et al. The effect of zinc supplementation on the course of COVID-19- A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2022; 29(4):568-574. [CrossRef]

- Francis Z, Book G, Litvin C, et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Zinc-Induced Copper Deficiency: An Important Link. Am J Med. 2022; 135(8):e290-e291. [CrossRef]

- Raha S, Mallick R, Basak S, et al. Is copper beneficial for COVID-19 patients? Med Hypotheses. 2020; 142:109814. [CrossRef]

- Fakhrolmobasheri M, Mazaheri-Tehrani S, Kieliszek M, et al. COVID-19 and Selenium Deficiency: a Systematic Review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2022; 200:3945-3956. [CrossRef]

- Gröber U, Holick MF. The coronavirus disease (COVID-19)- a supportive approach with selected micronutrients. Int J Vitam Nutr Res Int Z Vitam. Ernahrungsforschung J Int Vitaminol Nutr. 2021:1-22. [CrossRef]

- Gullin OM, Vindry C, Ohlmann T, et al. Selenium, selenoproteins and viral infection. Nutrients. 2019; 11:2101. [CrossRef]

- Kieliszek M, Lipinski B. Selenium supplementation in the prevention of coronavirus infection (COVID-19). Med Hypotheses. 2020; 143:109878. [CrossRef]

- Dludia PV, Nyambuya TM, Orlando P, et al. The impact of coenzyme Q10 on metabolic and cardiovascular disease profiles in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2020; 3(2):e00118. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Vieco E, Martínez-García I, Sequí-Domínguez I, et al. Effect of coenzyme Q10 on cardiac function and survival in heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Food Funct. 2023; 14:6302-6311. [CrossRef]

- Jorat MV, Tabrizi R, Kolahdooz F, et al. The effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in among coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflammopharmacology. 2019; 27(2);233-248. [CrossRef]

- Sue-Ling CB, Abel WM, Sue-Ling K. Coenzyme Q10 as adjunctive Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Nutrition. 2022; 152(7):1666-1674. [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves IR, Mantle D. COVID-19, Coenzyme Q10, and Selenium. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021; 1327161-168.

- Varnousfaderani SD, Musazadeh V, Ghalichi F, et al. Alleviating effects of coenzyme Q10 supplements on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress: result from an umbrella meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023;14:1191290. [CrossRef]

- Sumbalova Z, Kucharská J, Rausová Z, et al. Reduced platelet mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in patients with pst COVID-19 syndrome are regenerated after spa rehabilitation and targeted ubiquinol therapy. Front Mol Biosci. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ma B, Lu J, Kang T, et al. Astaxanthin supplementation mildly reduced oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Research. 2022; 99:40-50. [CrossRef]

- Talukdar J, Bhadra B, Dattaroy T, et al. Potential of natural astaxanthin in alleviating the risk of cytokine storm in COVID-19. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020; 132:110886. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi A-R, Ayazi-Nasrabadi R. Astaxanthin protective barrier and its ability to improve the health in patients with COVID-19. Iran J Microbiol. 2021; 13(4):434-441. [CrossRef]

- Cheema HA, Sohail A, Fatima A, et al. Quercetin for the treatment of COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2023; 33(2):e2427. [CrossRef]

- Ziaei S, Alimohammadi-Kamalabadi M, Hasani M, et al. The effect of quercetin supplementation on clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Science & Nutrition. 2023;11(12):7504-7514. [CrossRef]

- Mrityunjaya M, Pavithra V, Neelam R, et al. Immune-boosting, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory food supplements targeting pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020; 11(2337):570122. [CrossRef]

- Smith M, Smith JC. Repurposing therapeutics for COVID-19: supercomputer-based docking to the SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein and viral spike protein-human ACE2 interface. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Khaerunnisa S, Kurniawan H, Awaluddin R, et al. Potential inhibitor of COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) from several medicinal plant compounds by molecular docking study. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Derosa G, Maffioli P, D’Angelo A, et al. A role for quercetin in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Phytother Res.2021; 35(3):1230-1236. [CrossRef]

- Lammi C, Arnoldi A. Food-derived antioxidants and COVID-19. J Food Biochem. 2021; 45(1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Hassaniazad M, Eftekhar E, Inchehsablagh BR, et al. A triple-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effect of curcumin-containing nanomicelles on cellular immune responses subtypes and clinical outcome in COVID-19 patients. Phytotherapy Research. 2021; 35(11):6417-6427. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi M, Dehnavi S, Asadirad A, et al. Curcumin and chemokines: mechanism of action and therapeutic potential in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 2023; 31:1069-1093. [CrossRef]

- Rattis B, Ramos SG, Celles M. Curcumin as a potential treatment for COVID-19. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021; 12:675287. [CrossRef]

- Dourado D, Freire DT, Pereira DT, et al. Will curcumin nanosystems be the next promising antiviral alternatives in COVID-19 treatment trials? Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2021; 139:111578. [CrossRef]

- Manoharan Y, Haidas V, Vasanthakumar KC, et al. Curcumin: A wonder drug as a preventive measure for COVID-19 management. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2020; 35(3):373-375. [CrossRef]

- Hassaniazad M, Eftekhar E, Inchehsablagh BR, et al. A triple-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effect of curcumin-containing nanomicelles on cellular immune responses subtypes and clinical outcome in COVID-19 patients. Phytotherapy Research. 2021; 35(11):6417-6427. [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh H, Abdolmohammadi-Vahid S, Danshina S, et al. Nano-curcumin therapy, a promising method in modulating inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 patients. International Immunopharmacology. 2020; 89:101088. [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebi S, El-Esawi MA, Mahmoud ZH, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of nanocurcumin on Th17 cell responses in mild and severe COVID-19 patients. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2021; 236(7):5325-5338.

- Chia S-K, Ramachandram DS, Hasan S. The effect of curcumin on the risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Phytotherapy Research. 2022; 36:3365-3368. [CrossRef]

- Shafiee A, Athar MMT, Shahid A, et al. Curcumin for the treatment of COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytotherapy Research. 2023; 37(3):1167-1175. [CrossRef]

- van Eijk, Larissa E, Offringa, et al. The Disease-Modifying Role of Taurine and Its Therapeutic Potential in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Taurine 2. 2022.

- Rubio-Casillas A, Gupta RC, Redwan EM, et al. Early taurine administration as a mean for halting the cytokine storm progression in COVID-19 patients. Explor Med. 2022; 3:234-48. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Navarro JC, Dias LF, Gomes de Gouveia LA, et al. Vegetarian and plant-based diets associated with lower incidence of COVID-19. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. 2024; O:e000629.

- Soltanieh S, Salavatizadeh M, Ghazanfari T, et al. Plant-based diet and COVID-19 severity: results from a cross-sectional study. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. 2023; O:e000688. [CrossRef]

- Kendrick KN, Kim H, Rebholz CM, et al. Plant-Base Diets and Risk of Hospitalization with Respiratory Infection: Results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15:4265. [CrossRef]

- Kahleova H, Barnard ND. Can a plant-based diet help mitigate COVID-19?. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022; 76:911-912. [CrossRef]

- Wang J-Z, Sato T, Sakuraba A. Worldwide association of lifestyle-related factors and COVID-19 mortality. Annals of Medicine. 2021, Vol 53; 1:1528-1533. [CrossRef]

- Storz, MA. Lifestyle Adjustments in Long-COVID Management: Potential Benefits of Plant-Based Diets. Current Nutrition Reports. 2021; 10:352-363. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Rebholz CM, Hedge S, et al. Plant-based diets, pescatarian diets and COVID-19 severity: a population-based case-control study in six countries. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. 2021; 4:e000272. [CrossRef]

- Lange KW, Nakamura Y. Lifestyle factors in the prevention of COVID-19. Global Health Journal. 2020; 4:146-152. [CrossRef]

- Khaleova H, Barnard ND. The Role of Nutrition in COVID-19: Taking a Lesson from the 1918 H1N1 Pandemic. SAGE. 2022. http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav.

- Rust P, Ekmekcioglu. The Role of Diet and Specific Nutrients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Have We Learned over the Last Three Years?. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20:5400. [CrossRef]

| Foods with poor DII | Foods with excellent DII |

|---|---|

| Red meat (steak and hamburgers) Animal products (fish, poultries, eggs, dairy products; milk, cheese, and butter) Processed meat (bologna, bacon, sausage and lunchmeat) Commercial baked goods (snack cakes, pies, cookies and brownies) White flour (bread and pasta), white rice Deep-fried items (French fries, fried chicken, and donuts) Sugary foods (soda, canned tea drinks, and sports drinks) Trans-fats (margarine, microwave popcorn, refrigerated biscuits, dough, and nondairy coffee creamers) Saturated fats (especially animal fats) Cholesterol (red meats, processed meats, eggs, fried foods and dairy products) |

Plant-based proteins (beans, lentils, chickpeas, edamame, hemp seeds, tofu, tempeh, and nuts) Whole grains (oatmeal, buckwheat, quinoa, brown rice) Starchy vegetables (sweet potatoes and squash) Seeds (flaxseeds and chia seeds) Green leafy vegetables (bok choy, collard greens, kale, mustard greens, romaine lettuce, spinach, and arugula) Colorful vegetables (carrots, pumpkin, yellow/ green peppers and cauliflower) Fruits (berries, apples, grapes, oranges, peaches, figs, bananas, and kiwi) Spices and herbs (turmeric, ginger, cumin, peppermint, cinnamon, chili, parsley, bay leaf, and basil) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).