1. Introduction

The utilization of real-world data (RWD) to generate real-world evidence (RWE) in conjunction with interventional clinical trial-based research is rapidly increasing. This burgeoning field, particularly in the context of oncology, has seen a significant number of publications and increased use of RWD in medical regulation in recent years. It is essential to improve the quality of RWE for the benefit of patients, scientific community, and healthcare authorities.

Oncology research presents a multitude of particularities, including specific variables, biomarkers, therapies, and outcomes, which are not adequately addressed by the existing reporting guidelines. Furthermore, contemporary technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) have been integrated into various stages of data analysis in real-world evidence (RWE) studies. Although guidelines for interventional studies involving AI are now available [

1,

2], similar guidance specifically tailored for RWE research remains absent.

Real-world data (RWD) studies have several advantages such as increased sample sizes, quicker achievement of research objectives, and reduced costs compared to conventional clinical trials [

3,

4,

5]. Nevertheless, when conducting RWD studies, several challenges must be addressed, such as accessibility and protection of data, compliance with relevant laws and regulations, and the necessity for meticulous study design and analysis.

2. Role of RWD in Oncology

Real-world data (RWD) studies are increasingly being utilized as alternative sources of evidence in clinical cancer research. These studies provide valuable information to inform the decisions of regulators, sponsors, and clinicians. RWD studies primarily rely on collecting and analyzing observational data, which offers insights into the practical application of cancer treatment in real-world settings.

RWD's poor quality sometimes compromises the reliability of real-world evidence (RWE). In such cases, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are necessary to answer specific research questions definitively. Hybrid methodological analyses that combine the strengths of RCTs and RWD studies, known as R2WE, are currently being conducted to address these challenges. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) is developing a strategy to build solid, high-quality RWE by prioritizing realistic clinical trials. This approach aimed to provide evidence to support new therapeutic approaches in clinical practice [

6].

Research using real-world data (RWD) has several advantages including access to larger datasets, greater generalizability, and shorter study duration. However, obtaining data and ensuring compliance with laws and regulatory requirements can be challenging. Despite these obstacles, RWD studies have the potential to address evidence gaps and provide crucial information about the effects of cancer treatment in real-world settings [

6,

7].

RWD sources include patient registries and electronic health records (EHRs). Patient registries are structured systems that gather specific information about patients with a particular condition or treatment, whereas EHRs are digital versions of patients' medical records. Other sources of RWD include patient questionnaires, mobile devices, smartphones, and social media [

8,

9].

High-quality data are the foundation for credible real-world evidence (RWE). To generate RWE, it is essential to obtain data from relevant real-world data (RWD) sources, clean and harmonize the data, and link them to fill in gaps. Additionally, the data must include endpoints relevant to the research question. Quality criteria must be applied throughout the process of generating RWE, from data sources to processing, to ensure that appropriate use cases are defined.

The importance of patient follow-up during daily clinical practice in the field of oncology is becoming increasingly recognized as a valuable means of data collection. Such follow-up studies offer valuable insights into the safety and efficacy of interventions in specific patient populations, including those with chronic viral diseases, brain metastases, or poor performance status. By incorporating data analysis and evaluating their impact on healthcare budgets, real-world population follow-up studies have the potential to inform more appropriate treatment choices and may even be considered part of the regulatory approval process in the future [

10].

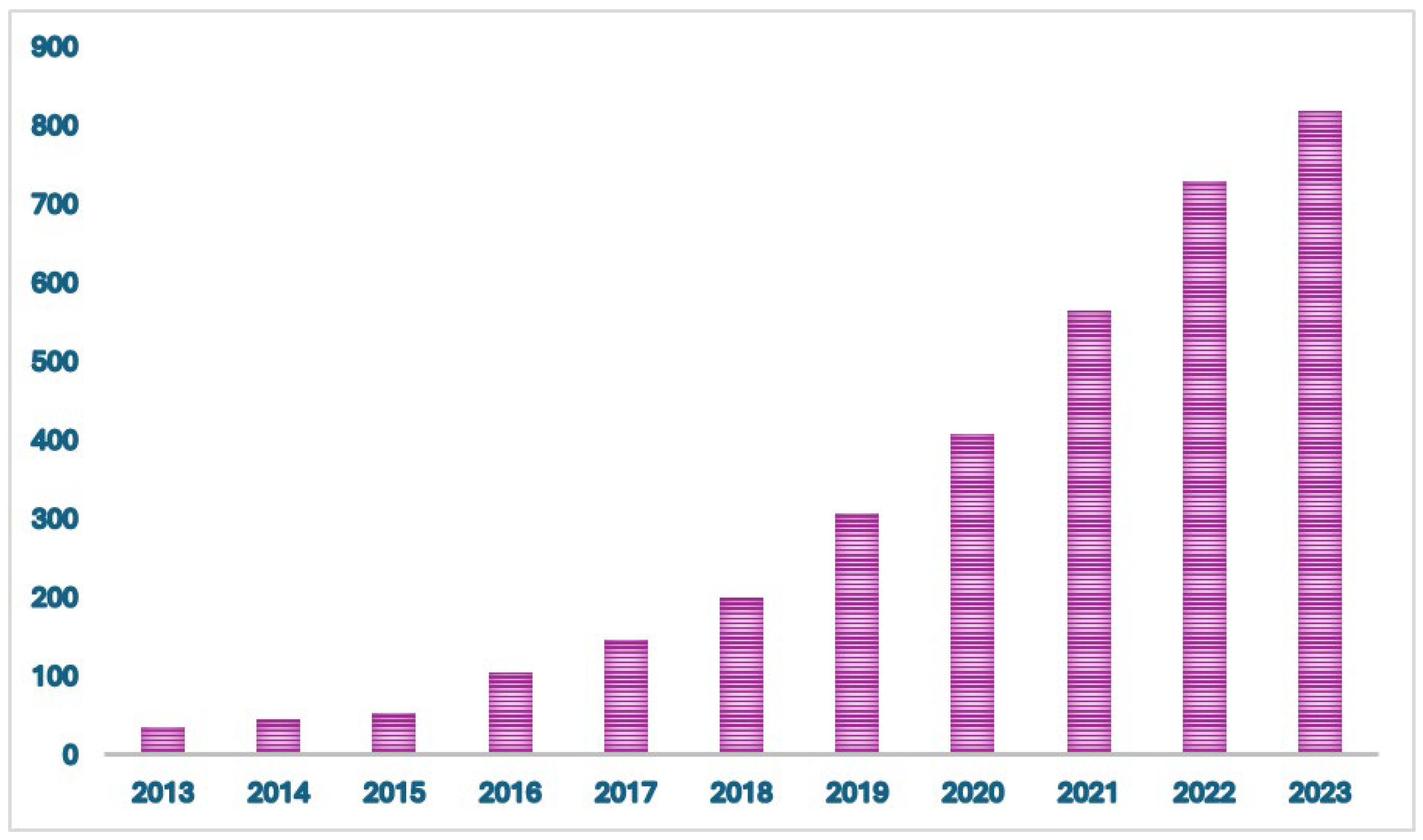

Figure 1.

Number of citations/year of real-world evidence in oncology between January 2013 and January 2024.

Figure 1.

Number of citations/year of real-world evidence in oncology between January 2013 and January 2024.

3. Potential Use of RWE

Regulatory-grade real-world evidence (RWE) has the potential to provide critical information for informed decision making by clinicians, patients, and regulatory authorities. Traditional Phase IV and other post-marketing studies can be burdensome and face numerous obstacles in patient enrollment, such as evolving practice patterns. Well-designed RWE studies can generate innovative hypotheses for future research in basic sciences, drug development, health outcomes, and clinical trials. Longitudinal real-world evidence (RWE) could potentially aid the identification of rare side effects across extensive populations. By employing thorough RWE studies, it may be possible to uncover adverse event trends in real time rather than relying solely on voluntary reporting. Through a comprehensive assessment of both structured and unstructured real-world data (RWD) for individual patients, real-world evidence (RWE) can rigorously document safety and effectiveness at the necessary level of quality and detail to support label expansion.

When a new oncological therapeutic is in the process of development, it is subject to various decision points that determine whether it will continue to be developed. The use of real-world evidence (RWE) can aid in optimizing these decisions during predevelopment and in guiding clinical development strategies by clarifying unmet needs in the real world. The incorporation of real-world evidence (RWE) into clinical development can also play a role in the planning and execution of clinical trials. By offering insights into specific populations, RWE can aid in reducing the excessively restrictive exclusion criteria. Furthermore, knowledge of the prevalence patterns of potential trial candidates such as rare cancers that progress despite chemotherapy can facilitate patient recruitment for clinical trials. The use of synthetic control arms based on RWE is also being investigated, particularly for cancers with well-established standards of care, poor prognoses, and low incidences (e.g., small cell lung cancer). In contrast to historical controls, synthetic controls may possess greater recency, which can help to account for changes in supportive care over time.

Treatment decisions are often determined by the risk-benefit ratio for each individual patient. Although it is impossible to completely eliminate clinical uncertainty, the utilization of real-world evidence (RWE) can aid in refining this assessment and facilitating personalized medicine tailored to both the patient and tumor. The extent and significance of potential RWE use cases necessitate stringent quality assessments, particularly when utilized for regulatory decision making.

The complexities of lung cancer treatment, coupled with the diverse range of therapeutic options currently available, require delicate and informed clinical decision-making on the part of healthcare providers and those responsible for resource allocation (e.g., payers and regulators) [

11]. This highlights the need for rapid and ongoing insights into these decisions. Such insights are typically provided by data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and real-world evidence (RWE). RWE can offer information that would not be readily obtainable through RCTs, generating data that reflects routine clinical practice in larger, real-life treatment populations. In the field of lung cancer drug development, there are many examples of the usefulness of RWE in providing complementary data to reinforce and support clinical trial data. For instance, recent real-world studies have evaluated the safety and/or effectiveness of lung cancer treatments, often in patient cohorts ineligible for clinical trials [

12,

13,

14,

15], investigated the real-world burden of lung cancers and related treatment patterns and survivorship [

13,

14,

16,

17,

18] and assessed treatment-related costs/healthcare resource utilization (HCRU)[

13,

14,

17,

19].Therefore, data from both observational real-world studies and traditional RCTs are important in informing the best clinical practice, and regulatory bodies recognize that these two methodologies are complementary in both the pre- and post-authorization stages of drug development [

14].

4. RWE in Cancer Drug Development

The current regulatory framework of the FDA affords sufficient flexibility to integrate novel forms of clinical evidence into decision-making processes [

20]. To this end, efforts should concentrate on devising suitable study designs and strategies for acquiring high-quality data from EHRs in the context of real-world data utilization.

- 1)

Real-world Evidence for Digital Pharmacovigilance

Regulatory agencies primarily rely on passive surveillance to ensure post-market pharmacovigilance. This approach entails the analysis of voluntary reports of adverse events submitted by healthcare professionals and patients as well as mandatory reporting from pharmaceutical companies [

21]. However, passive reporting has several limitations, including the influence of extraneous factors, such as media attention and the length of time a product has been on the market. To address these challenges, the FDA established the Sentinel Initiative, which seeks to develop an active surveillance system that proactively investigates real-world data (RWD) to detect new safety signals [

22,

23]. The advent of advanced information technology presents an opportunity to create an integrated approach that leverages RWD from electronic health records (EHRs) and patient-generated sources, such as mobile applications and internet search logs, to modernize pharmacovigilance [

24,

25]. Adopting a digital pharmacovigilance system that merges real-world data (RWD) from healthcare providers through electronic health records (EHRs) and online platforms that are used by patients to researchers and experts in the pharmaceutical industry and regulatory authorities can develop a proactive monitoring system, permitting the application of protective measures to recognize certain safety concerns. In a digital drug safety monitoring system, the efficiency of safety indicators can be analyzed using techniques such as data mining, like proportional reporting ratios and empirical Bayesian geometric mean scores, which have already been utilized by regulatory authorities like the FDA [

26,

27]. Furthermore, a digital system that integrates various streams of real-world data can use deep learning methods with the help of artificial intelligence and natural language processing to amplify safety signal detection methods. [

28,

29,

30].

- 2)

Utilizing RWE to investigate disease progression and establish external control

The natural history of a disease refers to the progression of the disease from its onset to the presymptomatic phase, through various clinically symptomatic stages, and finally to the resolution of the disease or the patient's death, without any intervention [

31]. One way to elucidate this continuum is to examine the effect of two types of variables that affect the likelihood of developing an asymptomatic disease from a healthy state and progression to the symptomatic stage of the disease [

32]. Real-world data (RWD) present a valuable opportunity to investigate the covariates that affect the natural history of diseases in populations where a significant portion is regularly monitored and treated. For instance, retrospective analysis of electronic health record (EHR) data can be employed to identify covariates that contribute to the onset of cancer in healthy individuals. This analysis can help elucidate the patient and environmental factors that influence disease occurrence. Similarly, examining EHR data retrospectively can aid in identifying covariates associated with cancer progression from the asymptomatic to the symptomatic stage. Such investigations can provide crucial insights into the design of future prospective clinical trials to assess the impact of cancer screening and early intervention on patient outcomes.

In clinical studies, such as single-arm trials, utilizing external control data can potentially aid in the establishment of comparative benchmarks for regulatory decision-making, particularly for serious conditions with high unmet medical needs, such as advanced malignancies [

33]. If preliminary clinical evidence from a single-arm trial indicates a significant treatment effect, evaluating outcomes in comparable patient groups using real-world data (RWD) can offer a reliable assessment of the safety and efficacy of available therapies for comparison.

Advancements in genomic sequencing and computational proteomics have led to the identification of a growing number of rare tumor variants resulting from somatic mutations, proteomic signatures, and alterations in cell signaling pathways with oncogenic potential [

34], [

35,

36]. Retrospective analysis of real-world data (RWD) can provide an adequate approach to the evaluation of biomarkers and their prognostic significance regarding disease outcomes in rare subgroups during clinical development. Clinical results from RWD registries may be connected to genomic and proteomic profiles predicting outcomes and establishing guidelines. This will require enhancing big data analytics capabilities to effectively analyze complex and rare patterns identified by multi-omics pipelines, aiming to improve patient care and outcomes.

- 3)

Observational Real-World studies

There is a growing convergence between the outcomes of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and well-designed observational studies, which presents an opportunity to develop robust methodologies that support electronic health record (EHR)-based observational research [

20,

37,

38]. Data collection from real-world settings through observational studies have the ability to contribute valuable information, that can be utilized in randomized controlled trials or regulatory decision-making. Furthermore, observational studies offer an opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of treatments in patient populations that are often occluded from conventional cancer clinical trials. New regulatory incentives for drug developers to submit real-world data (RWD) to patients excluded from conventional clinical trials can improve the generalizability of FDA label information, enabling prescribers to make informed treatment decisions [

39].

- 4)

Practical clinical studies

Electronic health records (EHRs) serve as primary instruments for conducting practical clinical trials (PCTs). EHRs are widely accessible tools in the healthcare sector that can aid in establishing a clinical trial program based within the point of care and linked to patients digitally through innovative technologies like sensors and mobile apps. Through facilitating the deliberate gathering of pertinent clinical data that accurately represents the diverse range of cancer patients, EHRs play a role in bringing real-world evidence to pharmaceutical research, while emphasizing advancements in quality, patient safety, and value in cancer treatment delivery [

40].

In the realm of cancer drug development, pragmatic clinical trials (PCTs) present numerous advantages compared to traditional clinical trials, which are typically limited to specialized facilities with the required resources and capacity to maintain research initiatives. The limited involvement rates in cancer trials, particularly among minority groups, the elderly, individuals with low income, and those living in rural areas (less than 5%), underscore the obstacles presented by the division of clinical research across geographically dispersed locations [

20,

41,

42,

43]. The primary reason for the low participation in cancer trials is the obstacles to accessing convenient experimental treatments, rather than patient preferences [

44,

45]. PCTs have the ability to adhere to the existing standards of methodological, ethical, legal, and regulatory oversight in clinical research while enhancing access to experimental treatments in a secure and effective manner.

- 5)

Evaluating risks to the internal validity of real-world studies

The internal validity of studies conducted in real-world settings, particularly those utilizing nonrandomized designs, necessitates the effective management of bias stemming from provider-patient interactions, methodologies employed in data collection and processing, and the diverse practice patterns present within regional healthcare systems.

5. RWD on ICIs Outcomes and Safety

In recent years, the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has significantly improved the treatment of lung cancer. Anti-PD1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab) and anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab and durvalumab) agents, are capable of omitting the immune evasion mechanisms used by tumors and restore the immune system's antitumor response. At the beginning, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) were used as primary or secondary therapies for patients with advanced-stage disease, both for those selected based on PD-L1 expression (such as pembrolizumab) and for the overall patient population. Afterward, durvalumab was integrated as a consolidation therapy in a treatment algorithm for PD-L1 positive locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Currently, ICIs are employed as adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatments.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are widely regarded as the most robust form of evidence and, therefore, serve as the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of an intervention. Nonetheless, the translation of this evidence into real-life clinical practice can be problematic, as a substantial number of patients encountered in everyday practice are often underrepresented in RCTs. In light of the incorporation of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as the standard of care for lung cancer, oncologists are confronted with the dearth of data pertaining to patient subsets that are typically excluded from pivotal clinical trials. In particular, it is of utmost importance to gather information concerning the safety and efficacy of ICIs in individuals with chronic viral diseases, as well as in those presenting with brain metastases or an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 2 or worse.

The majority of data available on the application of immunotherapy in lung cancer pertain to its efficacy, as measured by objective response rate (ORR), overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS), as well as its safety profile, with respect to the most frequently utilized immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in clinical practice.

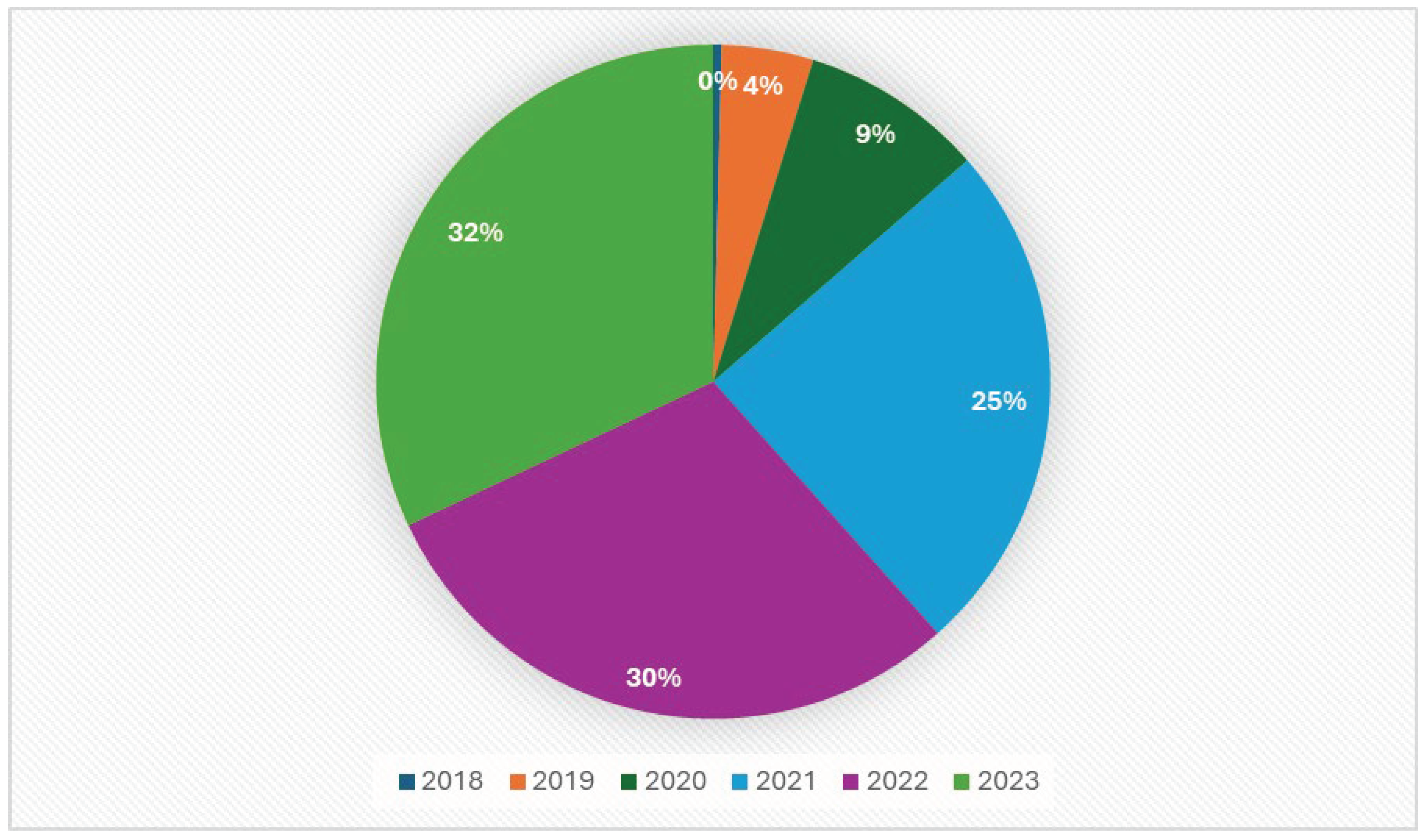

Figure 2.

Amount of real-world data on ICIs between 2018 and 2024.

Figure 2.

Amount of real-world data on ICIs between 2018 and 2024.

6. Real-World Evidence on Special Populations

- 1)

Elderly

The typical age of individuals at the time of lung cancer diagnosis is 70 years old [

46]. It is worth noting that the elderly population is often underrepresented in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). All the studies examined indicated that the efficacy of ICI monotherapy did not differ statistically between older and younger patients, and that tolerability was not influenced by age [

34,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Muchnik et al. reported that the incidence of immune-related colitis was higher in patients aged > 80 years [

34].

- 2)

ECOG performance status 2

The primary pivotal trials for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in lung cancer strictly excluded patients with poor performance status (PS), confining the inclusion criteria to PS 0 or 1 according to the ECOG classification, whereas only a limited number of clinical trials enrolled patients with PS 2 [

51,

52]. Nevertheless, both the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for the four available ICIs without regard to the PS of patients. As a result, the use of ICIs in clinical practice for patients with PS 2 has been permissible, leading to the accumulation of real-world data.

The absence of solid data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) warrants caution regarding the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in patients with poor performance status (PS), as the demonstrated safety profile may not suffice to justify the high costs in the absence of a survival benefit [

53]. The PePS2 trial is a Phase II clinical study that aims to assess the safety and tolerability of pembrolizumab in the treatment of NSCLC patients with an ECOG Performance Status of 2 [

54]. The trial has co-primary endpoints that include measuring durable clinical benefit (DCB), objective response rate (ORR), and the incidence of dose interruptions or discontinuations due to immune-related adverse events (irAEs). A pre-liminary analysis of data from a subgroup of 60 patients revealed a DCB rate of 33%, an ORR of 30%, and an irAE incidence of 8%. Although these initial results are encouraging, when analyzing the results of survival rates, it is crucial to proceed with caution, as the median PFS was 5.4 months and OS was 11.7 months, and only 15% of patients (9 out of 60) received first-line pembrolizumab, resulting in no responses and a PFS of 1.9 months. In a retrospective study conducted by Facchinetti et al., the outcomes of patients with PS 2 who received first-line pembrolizumab treatment were evaluated. The results indicated that patients with PS 2 related to comorbidity had a median overall survival (OS) of 11.8 months, while those with PS 2 driven by lung cancer had a median OS of 2.8 months. The hazard ratio (HR) for OS was 0.5 (p = 0.001) in favor of the former group [

55].

- 3)

Central nervous system metastases

The central nervous system (CNS) is a common site of metastases in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with an estimated incidence of brain metastases (BM) of approximately 40%. Patients with BM often experience symptoms, necessitating treatment with corticosteroids, and have a poor prognosis. As a result, this particular patient population is underrepresented in clinical trials, where individuals with BM are typically included only when the CNS disease is inactive and does not require active treatment. In pivotal trials of immunotherapy in lung cancer, the proportion of patients with inactive and asymptomatic BM ranges from 6% to 17.5%, and no preplanned analysis of CNS metastasis subgroups has been conducted [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

Currently, available empirical data are limited. However, a study conducted by Pasello has provided valuable insights by examining 255 individuals with BM who were participants in a multicenter, prospective research project and were administered ICIs [

61]. The study population comprised approximately 40% individuals with active brain metastasis (BM) and 14% symptomatic patients. Despite a lower rate of disease control and a higher incidence of progressive brain disease compared to patients without central nervous system (CNS) metastasis, the presence of BM was not found to be an independent predictor of overall survival (OS) in multivariate analysis, taking into account steroid treatment and performance status (PS) [

61]. Moreover, the administration of cranial radiotherapy, whether in the form of whole-brain or stereotactic radiotherapy, did not demonstrate a significant impact on survival. Including patients with CNS metastasis, the Italian Expanded Access Program (EAP) using nivolumab demonstrated no disparities in overall survival (OS) between the squamous and non-squamous populations when compared with the general population OS [

62,

63,

64]. Correspondingly, the French EAP with nivolumab, which included 130 patients with brain metastasis (BM), yielded similar outcomes [

65]. Generally, the body of real-world data derived from NSCLC patients with CNS metastasis who have been treated with immunotherapy offers more compelling evidence of both safety and efficacy than randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in this particular patient population.

- 4)

Patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) act on molecular pathways involved in physiological immune self-tolerance. These treatments are associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which are essentially new autoimmune disorders triggered by therapy. Owing to this risk, patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases (AIDs) were excluded from clinical trials for ICIs, except those with vitiligo, type I diabetes mellitus, or residual hypothyroidism that only requires hormone replacement. This exclusion was based on fear of unacceptable immune reactions and severe toxicities. Individuals with these disorders are susceptible to malignant tumors, particularly lung cancer [

66]. Almost one-fifth of all lung cancer patients have an underlying autoimmune disease (AID)[

67],[

68]. Several retrospective studies have investigated the potential risks and benefits of immunotherapy in a specific subset of patients. In a noteworthy study, Leonardi et al. examined 56 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and autoimmune disease (AID), who were treated with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapy [

69]. Researchers have reported that the incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) was similar to that observed in clinical trials. Additionally, they noted that AID exacerbations occurred in only a minority of patients, particularly those who were already experiencing symptoms of their AID at the time of initiating immunotherapy. A comprehensive retrospective study was conducted on a substantial cohort of patients (n = 751) diagnosed with advanced solid malignancies who were treated with anti-PD-1 agents. This study aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of these treatments in relation to the presence of pre-existing autoimmune diseases (AIDs) [

68]. Two-thirds of the patients were diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This study revealed that the incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) of any grade was higher in patients with pre-existing AIDs, regardless of whether the AIDs were symptomatic. However, no significant differences were observed in the incidence of grade 3–4 irAEs, overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), or overall survival (OS) between the two groups. It was also discovered that nearly half of the patients with pre-existing AIDs experienced a flare-up of their autoimmune disorder, with a wide range of incidence depending on the AID subtype. Specifically, the incidence ranges from 10% for rheumatologic disorders to 100% for gastrointestinal and hepatic diseases [

68]. These real-world findings suggest that pre-existing AIDs should not necessarily be considered absolute contraindications for immunotherapy.

- 5)

Patients with chronic viral diseases

The majority of clinical trials involving immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have typically occluded patients with chronic viral infections, including HIV, HBV, and HCV. Concerns regarding potential viral reactivation and the need for antiviral therapy raise questions about treatment efficiency and safety. However, retrospective case series have shown that ICI treatment is safe for NSCLC patients who are HIV-positive, with no evidence of viral rebound, with similar safety profiles among 30 advanced NSCLC patients [

51,

70]. There is limited information available on the use of ICI in NSCLC patients with HBV or HCV. A retrospective study of 10 patients with NSCLC and HBV or HCV that received immunotherapy had similar toxicity and efficacy rates as those without viral infections [

71], without any impact on viral load or replication.

7. Conclusion and Feature Directions

The use of real-world data (RWD) in oncology is increasing to generate real-world evidence (RWE). RWD studies offer valuable information to regulators, sponsors, and clinicians. These studies relied on observational data and provided insights into real-world cancer treatment. Hybrid methodological analyses such as R2WE are being conducted to address the challenges of RWD quality. The European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) is developing a strategy to create high-quality RWE by prioritizing realistic clinical trials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dlamini, Z., Francies, F. Z., Hull, R., & Marima, R. (2020). Artificial intelligence (AI) and big data in cancer and precision oncology. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 18, 2300–2311. [CrossRef]

- Adir, O., Poley, M., Chen, G., Froim, S., Krinsky, N., Shklover, J., Shainsky-Roitman, J., Lammers, T., & Schroeder, A. (2020). Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Nanotechnology for Precision Cancer Medicine. Advanced Materials, 32(13), 1901989. [CrossRef]

- Pregelj, L., Hwang, T. J., Hine, D. C., Siegel, E. B., Barnard, R. T., Darrow, J. J., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2018). Precision Medicines Have Faster Approvals Based On Fewer And Smaller Trials Than Other Medicines. Health Affairs, 37(5), 724–731. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S., Arora, S., Amiri-Kordestani, L., De Claro, R. A., Fashoyin-Aje, L., Gormley, N., Kim, T., Lemery, S., Mehta, G. U., Scott, E. C., Singh, H., Tang, S., Theoret, M. R., Pazdur, R., Kluetz, P. G., & Beaver, J. A. (2023). Use of Single-Arm Trials for US Food and Drug Administration Drug Approval in Oncology, 2002-2021. JAMA Oncology, 9(2), 266. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C., Naci, H., Gurpinar, E., Poplavska, E., Pinto, A., & Aggarwal, A. (2017). Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: Retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009-13. BMJ, j4530. [CrossRef]

- Saesen, R., Lacombe, D., & Huys, I. (2021). Design, organisation and impact of treatment optimisation studies in breast, lung and colorectal cancer: The experience of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 151, 221–232. [CrossRef]

- Istl, A. C., & Gronchi, A. (2022). Neoadjuvant Therapy for Primary Resectable Retroperitoneal Sarcomas—Looking Forward. Cancers, 14(7), 1831. [CrossRef]

- Makady, A., De Boer, A., Hillege, H., Klungel, O., & Goettsch, W. (2017). What Is Real-World Data? A Review of Definitions Based on Literature and Stakeholder Interviews. Value in Health, 20(7), 858–865. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, R. E., Anderson, S. A., Dal Pan, G. J., Gray, G. W., Gross, T., Hunter, N. L., LaVange, L., Marinac-Dabic, D., Marks, P. W., Robb, M. A., Shuren, J., Temple, R., Woodcock, J., Yue, L. Q., & Califf, R. M. (2016). Real-World Evidence—What Is It and What Can It Tell Us? New England Journal of Medicine, 375(23), 2293–2297. [CrossRef]

- Saesen, R., Van Hemelrijck, M., Bogaerts, J., Booth, C. M., Cornelissen, J. J., Dekker, A., Eisenhauer, E. A., Freitas, A., Gronchi, A., Hernán, M. A., Hulstaert, F., Ost, P., Szturz, P., Verkooijen, H. M., Weller, M., Wilson, R., Lacombe, D., & Van Der Graaf, W. T. (2023). Defining the role of real-world data in cancer clinical research: The position of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 186, 52–61. [CrossRef]

- Berger, M. L., Sox, H., Willke, R. J., Brixner, D. L., Eichler, H., Goettsch, W., Madigan, D., Makady, A., Schneeweiss, S., Tarricone, R., Wang, S. V., Watkins, J., & Daniel Mullins, C. (2017). Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: Recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on real-world evidence in health care decision making. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 26(9), 1033–1039. [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, H., Fujimoto, D., Morimoto, T., Ito, M., Teraoka, S., Sato, Y., Nagata, K., Nakagawa, A., Otsuka, K., & Tomii, K. (2018). Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Patients With Advanced Non–Small-cell Lung Cancer Who Are Ineligible for Clinical Trials. Clinical Lung Cancer, 19(5), e721–e734. [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, A., Li, H., Bittoni, M. A., Camacho, R., Cao, X., Zhong, Y., Lubiniecki, G. M., & Carbone, D. P. (2018). Real-World Treatment Patterns, Overall Survival, and Occurrence and Costs of Adverse Events Associated With Second-Line Therapies for Medicare Patients With Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer, 19(5), e783–e799. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, S., Griesinger, F., Baas, P., Chao, D., Chouaid, C., O’Donnell, J. C., Penrod, J. R., Daumont, M., Lacoin, L., McKenney, A., Khovratovich, M., Munro, R. E., Durand-Zaleski, I., & Johnsen, S. P. (2019). I-O Optimise: A novel multinational real-world research platform in thoracic malignancies. Future Oncology, 15(14), 1551–1563. [CrossRef]

- Fukui, T., Okuma, Y., Nakahara, Y., Otani, S., Igawa, S., Katagiri, M., Mitsufuji, H., Kubota, M., Hiyoshi, Y., Ishihara, M., Kasajima, M., Sasaki, J., & Naoki, K. (2019). Activity of Nivolumab and Utility of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Predictive Biomarker for Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Prospective Observational Study. Clinical Lung Cancer, 20(3), 208-214.e2. [CrossRef]

- Buck, P. O., Saverno, K. R., Miller, P. J. E., Arondekar, B., & Walker, M. S. (2015). Treatment Patterns and Health Resource Utilization Among Patients Diagnosed With Early Stage Resected Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer at US Community Oncology Practices. Clinical Lung Cancer, 16(6), 486–495. [CrossRef]

- Wallington, M., Saxon, E. B., Bomb, M., Smittenaar, R., Wickenden, M., McPhail, S., Rashbass, J., Chao, D., Dewar, J., Talbot, D., Peake, M., Perren, T., Wilson, C., & Dodwell, D. (2016). 30-day mortality after systemic anticancer treatment for breast and lung cancer in England: A population-based, observational study. The Lancet Oncology, 17(9), 1203–1216. [CrossRef]

- Nadler, E., Espirito, J. L., Pavilack, M., Boyd, M., Vergara-Silva, A., & Fernandes, A. (2018). Treatment Patterns and Clinical Outcomes Among Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated in the Community Practice Setting. Clinical Lung Cancer, 19(4), 360–370. [CrossRef]

- Andreas, S., Chouaid, C., Danson, S., Siakpere, O., Benjamin, L., Ehness, R., Dramard-Goasdoue, M.-H., Barth, J., Hoffmann, H., Potter, V., Barlesi, F., Chirila, C., Hollis, K., Sweeney, C., Price, M., Wolowacz, S., Kaye, J. A., & Kontoudis, I. (2018). Economic burden of resected (stage IB-IIIA) non-small cell lung cancer in France, Germany and the United Kingdom: A retrospective observational study (LuCaBIS). Lung Cancer, 124, 298–309. [CrossRef]

- Khozin, S., Blumenthal, G. M., & Pazdur, R. (2017). Real-world Data for Clinical Evidence Generation in Oncology. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 109(11). [CrossRef]

- Edwards, I. R. (2012). An agenda for UK clinical pharmacology: Pharmacovigilance. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 73(6), 979–982. [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Sentinel initiative. 2017. http://www.fda.gov/ Safety/FDAsSentinelInitiative/ucm149340.htm. Accessed April 24, 2017).

- Food and Drug Administration. Sentinel initiative: A national strategy for monitoring medical product safety. 2008. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/ FDAsSentinelInitiative/ucm089474.htm. Accessed April 24, 2017.

- White, R. W., Harpaz, R., Shah, N. H., DuMouchel, W., & Horvitz, E. (2014). Toward Enhanced Pharmacovigilance Using Patient-Generated Data on the Internet. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 96(2), 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Salathé, M. (2016). Digital Pharmacovigilance and Disease Surveillance: Combining Traditional and Big-Data Systems for Better Public Health. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 214(suppl 4), S399–S403. [CrossRef]

- Evans, S. J. W., Waller, P. C., & Davis, S. (2001). Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 10(6), 483–486. [CrossRef]

- Dumouchel, W. (1999). Bayesian Data Mining in Large Frequency Tables, with an Application to the FDA Spontaneous Reporting System. The American Statistician, 53(3), 177–190. [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, A., Sarker, A., O’Connor, K., Ginn, R., & Gonzalez, G. (2015). Pharmacovigilance from social media: Mining adverse drug reaction mentions using sequence labeling with word embedding cluster features. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(3), 671–681. [CrossRef]

- Cocos, A., Fiks, A. G., & Masino, A. J. (2017). Deep learning for pharmacovigilance: Recurrent neural network architectures for labeling adverse drug reactions in Twitter posts. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 24(4), 813–821. [CrossRef]

- Graves, A., Wayne, G., Reynolds, M., Harley, T., Danihelka, I., Grabska-Barwińska, A., Colmenarejo, S. G., Grefenstette, E., Ramalho, T., Agapiou, J., Badia, A. P., Hermann, K. M., Zwols, Y., Ostrovski, G., Cain, A., King, H., Summerfield, C., Blunsom, P., Kavukcuoglu, K., & Hassabis, D. (2016). Hybrid computing using a neural network with dynamic external memory. Nature, 538(7626), 471–476. [CrossRef]

- de la Paz MP, Villaverde-Hueso A, Alonso V. Rare diseases epidemiology research. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:17–39).

- Brookmeyer, R. (1990). Statistical problems in epidemiologic studies of the natural history of disease. Environmental Health Perspectives, 87, 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Davi, R., Mahendraratnam, N., Chatterjee, A., Dawson, C. J., & Sherman, R. (2020). Informing single-arm clinical trials with external controls. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 19(12), 821-822. [CrossRef]

- Leiserson, M. D. M., Vandin, F., Wu, H.-T., Dobson, J. R., Eldridge, J. V., Thomas, J. L., Papoutsaki, A., Kim, Y., Niu, B., McLellan, M., Lawrence, M. S., Gonzalez-Perez, A., Tamborero, D., Cheng, Y., Ryslik, G. A., Lopez-Bigas, N., Getz, G., Ding, L., & Raphael, B. J. (2015). Pan-cancer network analysis identifies combinations of rare somatic mutations across pathways and protein complexes. Nature Genetics, 47(2), 106–114. [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B., Papadopoulos, N., Velculescu, V. E., Zhou, S., Diaz, L. A., & Kinzler, K. W. (2013). Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science, 339(6127), 1546–1558. [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. (2014). Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature, 511(7511), 543–550. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G. H., Holtzman, J. N., Lolich, M., Ketter, T. A., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2015). Recurrence rates in bipolar disorder: Systematic comparison of long-term prospective, naturalistic studies versus randomized controlled trials. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(10), 1501–1512. [CrossRef]

- Anglemyer, A., Horvath, H. T., & Bero, L. (2014). Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(4). [CrossRef]

- Beaver, J. A., Ison, G., & Pazdur, R. (2017). Reevaluating Eligibility Criteria—Balancing Patient Protection and Participation in Oncology Trials. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(16), 1504–1505. [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, A. P., Etheredge, L. M., Ganz, P. A., Wallace, P., German, R. R., Neti, C., Bach, P. B., & Murphy, S. B. (2010). Rapid-Learning System for Cancer Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(27), 4268–4274. [CrossRef]

- Al-Refaie, W. B., Vickers, S. M., Zhong, W., Parsons, H., Rothenberger, D., & Habermann, E. B. (2011). Cancer Trials Versus the Real World in the United States. Annals of Surgery, 254(3), 438–443. [CrossRef]

- Meropol, N. J. (2016). Overcoming cost barriers to clinical trial participation. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 13(6), 333–334. [CrossRef]

- Meropol, N. J., Buzaglo, J. S., Millard, J., Damjanov, N., Miller, S. M., Ridgway, C., Ross, E. A., Sprandio, J. D., & Watts, P. (2007). Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation as Perceived by Oncologists and Patients. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 5(8), 753–762. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. T., Chen, B., & Bennett, C. (2015). “Right-to-Try” Legislation: Progress or Peril? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(24), 2597–2599. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Kurzrock, B. A., Cohen, P. R., & Kurzrock, R. (2016). The right to try is embodied in the right to die. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 13(7), 399–400. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. [CrossRef]

- Grossi, F., Crinò, L., Logroscino, A., Canova, S., Delmonte, A., Melotti, B., Proto, C., Gelibter, A., Cappuzzo, F., Turci, D., Gamucci, T., Antonelli, P., Marchetti, P., Santoro, A., Giusti, S., Di Costanzo, F., Giustini, L., Del Conte, A., Livi, L., … De Marinis, F. (2018). Use of nivolumab in elderly patients with advanced squamous non–small-cell lung cancer: Results from the Italian cohort of an expanded access programme. European Journal of Cancer, 100, 126–134. [CrossRef]

- Galli, G., De Toma, A., Pagani, F., Randon, G., Trevisan, B., Prelaj, A., Ferrara, R., Proto, C., Signorelli, D., Ganzinelli, M., Zilembo, N., De Braud, F., Garassino, M. C., & Lo Russo, G. (2019). Efficacy and safety of immunotherapy in elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer, 137, 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Corbaux, P., Maillet, D., Boespflug, A., Locatelli-Sanchez, M., Perier-Muzet, M., Duruisseaux, M., Kiakouama-Maleka, L., Dalle, S., Falandry, C., & Péron, J. (2019). Older and younger patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors have similar outcomes in real-life setting. European Journal of Cancer, 121, 192–201. [CrossRef]

- Youn, B., Trikalinos, N. A., Mor, V., Wilson, I. B., & Dahabreh, I. J. (2020). Real-world use and survival outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors in older adults with non–small cell lung cancer. Cancer, 126(5), 978–985. [CrossRef]

- Spigel, D. R., McCleod, M., Jotte, R. M., Einhorn, L., Horn, L., Waterhouse, D. M., Creelan, B., Babu, S., Leighl, N. B., Chandler, J. C., Couture, F., Keogh, G., Goss, G., Daniel, D. B., Garon, E. B., Schwartzberg, L. S., Sen, R., Korytowsky, B., Li, A., … Hussein, M. A. (2019). Safety, Efficacy, and Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Symptom Burden with Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer, Including Patients Aged 70 Years or Older or with Poor Performance Status (CheckMate 153). Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 14(9), 1628–1639. [CrossRef]

- Popat, S., Ardizzoni, A., Ciuleanu, T., Cobo Dols, M., Laktionov, K., Szilasi, M., Califano, R., Carcereny Costa, E., Griffiths, R., Paz-Ares, L., Szczylik, C., Corral, J., Isla, D., Jassem, J., Appel, W., Van Meerbeeck, J., Wolf, J., Jiang, J., Molife, L. R., & Felip Font, E. (2017). Nivolumab in previously treated patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC: Results of a European single-arm, phase 2 trial (CheckMate 171) including patients aged ≥70 years and with poor performance status. Annals of Oncology, 28, v463. [CrossRef]

- Passaro, A., Spitaleri, G., Gyawali, B., & De Marinis, F. (2019). Immunotherapy in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients With Performance Status 2: Clinical Decision Making With Scant Evidence. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 37(22), 1863–1867. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, G., Brock, K., Savage, J., Mant, R., Summers, Y., Connibear, J., Shah, R., Ottensmeier, C., Shaw, P., Lee, S.-M., Popat, S., Barrie, C., Barone, G., & Billingham, L. (2020). Pembrolizumab in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer of performance status 2 (PePS2): A single arm, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(9), 895–904. [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, F., Mazzaschi, G., Barbieri, F., Passiglia, F., Mazzoni, F., Berardi, R., Proto, C., Cecere, F. L., Pilotto, S., Scotti, V., Rossi, S., Del Conte, A., Vita, E., Bennati, C., Ardizzoni, A., Cerea, G., Migliorino, M. R., Sala, E., Camerini, A., … Tiseo, M. (2020). First-line pembrolizumab in advanced non–small cell lung cancer patients with poor performance status. European Journal of Cancer, 130, 155–167. [CrossRef]

- Borghaei, H., Paz-Ares, L., Horn, L., Spigel, D. R., Steins, M., Ready, N. E., Chow, L. Q., Vokes, E. E., Felip, E., Holgado, E., Barlesi, F., Kohlhäufl, M., Arrieta, O., Burgio, M. A., Fayette, J., Lena, H., Poddubskaya, E., Gerber, D. E., Gettinger, S. N., … Brahmer, J. R. (2015). Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Non-squamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(17), 1627–1639. [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J., Reckamp, K. L., Baas, P., Crinò, L., Eberhardt, W. E. E., Poddubskaya, E., Antonia, S., Pluzanski, A., Vokes, E. E., Holgado, E., Waterhouse, D., Ready, N., Gainor, J., Arén Frontera, O., Havel, L., Steins, M., Garassino, M. C., Aerts, J. G., Domine, M., … Spigel, D. R. (2015). Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(2), 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Reck, M., Rodríguez-Abreu, D., Robinson, A. G., Hui, R., Csőszi, T., Fülöp, A., Gottfried, M., Peled, N., Tafreshi, A., Cuffe, S., O’Brien, M., Rao, S., Hotta, K., Leiby, M. A., Lubiniecki, G. M., Shentu, Y., Rangwala, R., & Brahmer, J. R. (2016). Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(19), 1823–1833. [CrossRef]

- Rittmeyer, A., Barlesi, F., Waterkamp, D., Park, K., Ciardiello, F., Von Pawel, J., Gadgeel, S. M., Hida, T., Kowalski, D. M., Dols, M. C., Cortinovis, D. L., Leach, J., Polikoff, J., Barrios, C., Kabbinavar, F., Frontera, O. A., De Marinis, F., Turna, H., Lee, J.-S., … Gandara, D. R. (2017). Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): A phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10066), 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, L., Rodríguez-Abreu, D., Gadgeel, S., Esteban, E., Felip, E., De Angelis, F., Domine, M., Clingan, P., Hochmair, M. J., Powell, S. F., Cheng, S. Y.-S., Bischoff, H. G., Peled, N., Grossi, F., Jennens, R. R., Reck, M., Hui, R., Garon, E. B., Boyer, M., … Garassino, M. C. (2018). Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(22), 2078–2092. [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, L. E. L., Bootsma, G., Mourlanette, J., Henon, C., Mezquita, L., Ferrara, R., Audigier-Valette, C., Mazieres, J., Lefebvre, C., Duchemann, B., Cousin, S., Le Pechoux, C., Botticella, A., De Ruysscher, D., Dingemans, A.-M. C., & Besse, B. (2019). Survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer having leptomeningeal metastases treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. European Journal of Cancer, 116, 182–189. [CrossRef]

- Cortinovis, D., Chiari, R., Catino, A., Grossi, F., De Marinis, F., Sperandi, F., Piantedosi, F., Vitali, M., Parra, H. J. S., Migliorino, M. R., Tondini, C., Tassinari, D., Frassoldati, A., Verderame, F., Pazzola, A., Cognetti, F., Palmiotti, G., Marchetti, P., Santoro, A., … Delmonte, A. (2019). Italian Cohort of the Nivolumab EAP in Squamous NSCLC: Efficacy and Safety in Patients With CNS Metastases. Anticancer Research, 39(8), 4265–4271. [CrossRef]

- Grossi, F., Genova, C., Crinò, L., Delmonte, A., Turci, D., Signorelli, D., Passaro, A., Soto Parra, H., Catino, A., Landi, L., Gelsomino, F., Tiseo, M., Puppo, G., Roila, F., Ricciardi, S., Tonini, G., Cognetti, F., Toschi, L., Tassinari, D., … Cortesi, E. (2019). Real-life results from the overall population and key subgroups within the Italian cohort of nivolumab expanded access program in non-squamous non–small cell lung cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 123, 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Crinò, L., Bronte, G., Bidoli, P., Cravero, P., Minenza, E., Cortesi, E., Garassino, M. C., Proto, C., Cappuzzo, F., Grossi, F., Tonini, G., Sarobba, M. G., Pinotti, G., Numico, G., Samaritani, R., Ciuffreda, L., Frassoldati, A., Bregni, M., Santo, A., … Delmonte, A. (2019). Nivolumab and brain metastases in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer, 129, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Molinier, O., Besse, B., Barlesi, F., Audigier-Valette, C., Friard, S., Monnet, I., Jeannin, G., Mazières, J., Cadranel, J., Hureaux, J., Hilgers, W., Quoix, E., Coudert, B., Moro-Sibilot, D., Fauchon, E., Westeel, V., Brun, P., Langlais, A., Morin, F., … Girard, N. (2022). IFCT-1502 CLINIVO: Real-world evidence of long-term survival with nivolumab in a nationwide cohort of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open, 7(1), 100353. [CrossRef]

- Franks et al: Associations of Autoimmunity and Cancer (Review)] Franks AL, Slansky JE. Multiple associations between a broad spectrum of autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. Anticancer Res 2012.

- Khan, S. A., Pruitt, S. L., Xuan, L., & Gerber, D. E. (2016). Prevalence of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Lung Cancer: Implications for Immunotherapy Treatment Options. JAMA Oncology, 2(11), 1507. [CrossRef]

- Cortellini, A., Buti, S., Santini, D., Perrone, F., Giusti, R., Tiseo, M., Bersanelli, M., Michiara, M., Grassadonia, A., Brocco, D., Tinari, N., De Tursi, M., Zoratto, F., Veltri, E., Marconcini, R., Malorgio, F., Garufi, C., Russano, M., Anesi, C., … Ficorella, C. (2019). Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Advanced Cancer and Pre-existing Autoimmune Diseases Treated with Anti-Programmed Death-1 Immunotherapy: A Real-World Transverse Study. The Oncologist, 24(6), e327–e337. [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, G. C., Gainor, J. F., Altan, M., Kravets, S., Dahlberg, S. E., Gedmintas, L., Azimi, R., Rizvi, H., Riess, J. W., Hellmann, M. D., & Awad, M. M. (2018). Safety of Programmed Death–1 Pathway Inhibitors Among Patients With Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Pre-existing Autoimmune Disorders. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(19), 1905–1912. [CrossRef]

- Pasello, G., Pavan, A., Attili, I., Bortolami, A., Bonanno, L., Menis, J., Conte, P., & Guarneri, V. (2020). Real world data in the era of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): Increasing evidence and future applications in lung cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 87, 102031. [CrossRef]

- Shah, N. J., Al-Shbool, G., Blackburn, M., Cook, M., Belouali, A., Liu, S. V., Madhavan, S., He, A. R., Atkins, M. B., Gibney, G. T., & Kim, C. (2019). Safety and efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in cancer patients with HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C viral infection. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, 7(1), 353. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).