1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has given rise to a pandemic, as declared on March 11

th 2020 by the World Health Organization [

1]. In the African continent, the first reported case of COVID-19 occurred in Egypt on February 14th, 2020 [

2]. Throughout the pandemic, Africa recorded the lowest rates of infection and deaths compared to the rest of the world. However, reported numbers have been shown not to be an accurate representation of the situation because of limited detection capacity [

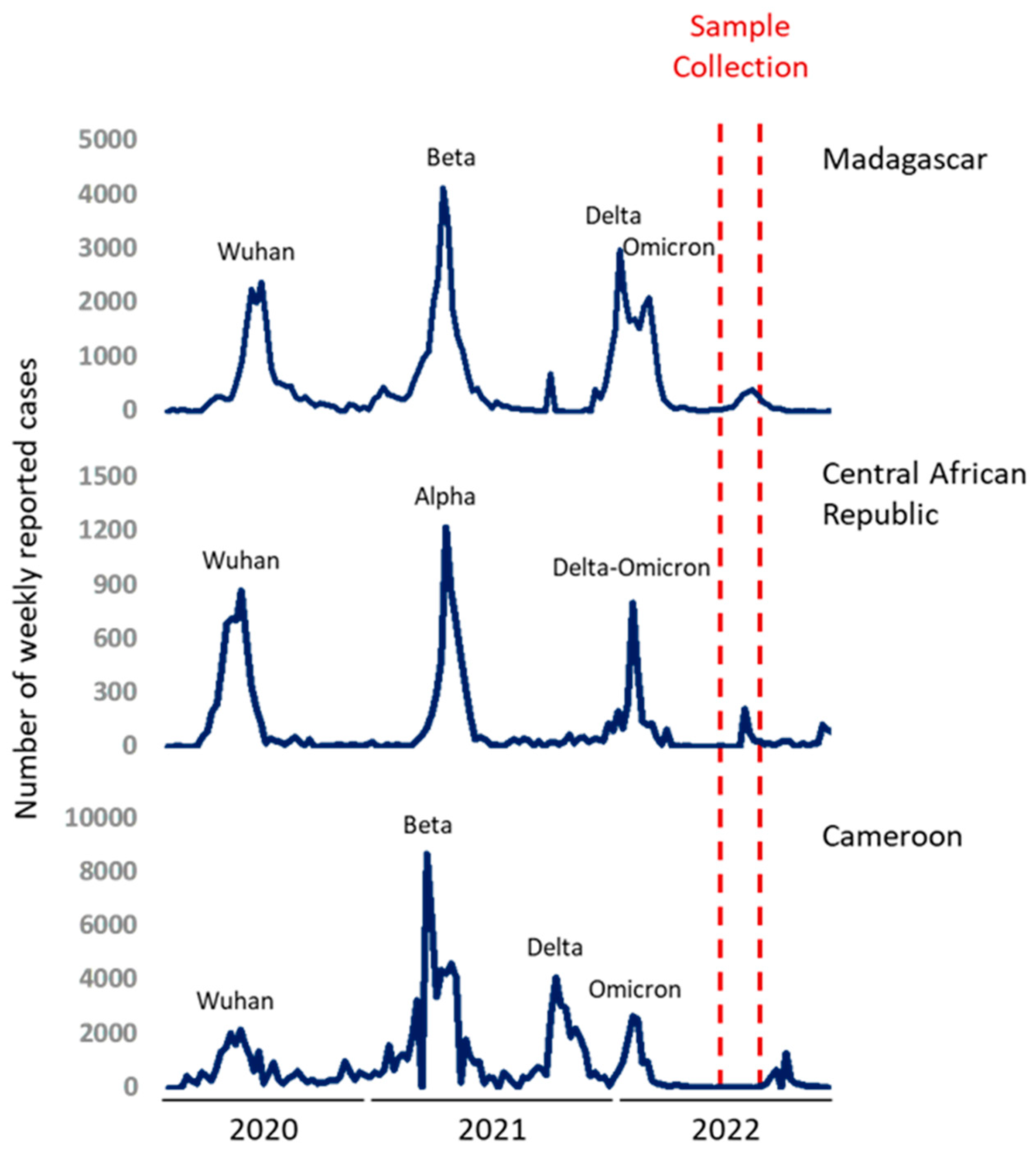

3]. Several variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been described, and only some of them are considered variants of concern (VOCs) according to their global impact on public health. VOCs are associated with particular characteristics such as reduced neutralization by antibodies acquired through previous infection or vaccination. At the time of this study, five SARS-CoV-2 VOCs had been identified. Four major waves had been associated mainly to the ancestral Wuhan strain, Beta, Delta and Omicron VOCs in Africa. These epidemic waves successively appeared without a large inter-peak and ended respectively in September 2020, April 2021, October 2021 and march 2022 [

4].

Studying landscape immunity in South Africa in populations infected at least once by SARS-COV-2 revealed that prior infection can confer protection to newly circulating viruses [

5]. In April 2022, Madagascar and the Central Africa Republic (CAR) had experienced three epidemic waves with comparable overall profiles while Cameroon had undergone four distinct epidemic waves [

4]. In Madagascar, the second epidemic wave was associated with the circulation of the VOC Beta (GH/501Y.V2) as previously reported in a study conducted in 2021 [

6,

7]. The third bimodal wave was the result of a combination of Delta and Omicron (B.1.1.529) VOCs circulations with apparently smaller peaks [

8]. On the other hand, CAR was hit by VOC Alpha during the second wave, followed by a smaller bimodal wave as in Madagascar with the co-circulation of Delta and Omicron during the third wave [

4]. For Cameroon, the second wave was caused by the VOC Beta (GH/501Y.V2) as in Madagascar, but, followed by two independent waves corresponding to the circulation of Delta then Omicron [

6]. The

Figure 1 illustrates the epidemic trends of reported cases and detected variants during these waves.

A previous study has shown that infection-derived immunity can vary dependently of the infecting variant [

9]. Furthermore, individuals who were infected with the VOC Beta experienced more severe outcomes compared to those infected with the Alpha variant, which exhibited higher vaccine efficacy. During the sampling period of the current study, VOC Omicron was circulating in these countries. Servellita

et al. assumed that the Omicron spread could have contributed to the mass immunization in the population, potentially leading to the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. This Omicron-driven wave had reduced virulence due to prior infection and/or vaccination [

10]. Moreover, Delta and Omicron infection have been shown to enhance immune responses against other variants, including the ancestral strain and other VOCs [

11].

Vaccination has been shown to enhance protection conferred by a previous infection [

12] in specific contexts. This immunity known as hybrid immunity is said to confer strong protection [

13]. It has been described that infection with VOC Omicron induces cross-neutralizing antibody responses by reinforcing pre-existing immunity conferred by natural infection or vaccination [

14,

15]. Consequently, measuring neutralizing antibodies can serve as an effective tool to quantitatively assess the protection conferred by natural immunity, vaccination or a combination of both [

16]. This approach can also help in predicting the level of protection against re-infection, particularly concerning potential future VOCs [

17]. The population in Madagascar and Cameroon exhibited low vaccination coverage, with less than 10% vaccination coverage in April 2022, while the CAR had a vaccination coverage of 22.1% [

18] at the same time.

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are considered as vulnerable populations given their high risk of exposure [

19], they are also on the front line of vaccination campaigns. Indeed, the pooled estimated prevalence of HCW acceptance for the COVID-19 vaccine was 56.6% in 2022 [

20]. Investigating the immunity of these highly exposed populations in different epidemiological contexts may provide valuable immunization descriptions.

The current study thus aimed to evaluate the immunization status of HCWs in Madagascar, Cameroon and in CAR considering infection and/or vaccination. In this multicentric study, we assessed neutralization profiles against the ancestral Wuhan strain (W) and the Omicron BA.2 (BA.2) VOC after the third wave of COVID-19 infections in 2022.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population and serum sampling

2.1.1. Participants from Madagascar

From May to June 2022, a cross-sectional study was set up to estimate SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences at the end of the third bimodal epidemic wave and targeting HCWs. The study was carried out in 3 university hospitals in Antananarivo: CHU Joseph Raseta Befelatanana, CHU Anosiala and CHU de Soavinandriana. A standardized questionnaire was used at inclusion to collect information about previous COVID-19 infection and vaccination. For HCW who declared vaccination, vaccination cards were requested when available. Five mL (5mL) blood samples were collected from each participant to determine seroprevalences and seroneutralization potential.

Ethical approvals for this study and the use of blood collected from this cohort were given by the Biomedical Research Committee of the Ministry of Public Health in Madagascar (n°.072-MSANP/SG/AGMED, April 23rd 2020 and n°.45-MSANP/SG/AMM/CNPV/CERBM, April 19th 2022).

2.1.2. Participants from Central Africa Republic

In May 2022, our survey took place at three key healthcare institutions in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic: The University Hospital of the Sino-Central African Friendship (CHUASC), the Community University Hospital (CHUC), and the Maman Elisabeth Domitien University Hospital (CHUMED). These hospitals, namely CHUMED, CHUASC, and CHUC, are esteemed national teaching hospitals. Our study encompassed all healthcare personnel involved in patient care, including medical doctors, nurses, midwives, radiology technicians, laboratory technicians, surgeons’ staff, as well as support staff with non-clinical roles within the healthcare departments of these institutions. Demographic information such as gender and age, along with qualifications, was collected from the participating healthcare workers. Additionally, blood samples of approximately 1 to 2 mL were obtained in dry tubes. Serums were subsequently stored at -20°C and then transferred to the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar for further analysis.

The protocol for this study received approval from the Ethics and Scientific Committee of the University of Bangui (N˚16/UB/FACSS/CES/20) and authorization from the Ministry of Health and Population (N˚ 934/MSP/DIRCAB/CMPSC/20) before the survey was conducted.

2.1.3. Participants from Cameroon

From July to August 2022, a cross-sectional study was conducted among HCWs in two referral hospitals located in Yaoundé (the Jamot Hospital and the Specialized Center for the Care of Covid-19 Patients, Annex 2, Central Hospital) and two district hospitals (Obala and Mbalmayo). Any staff (health, administrative, and support) whose names were on the official staff list transmitted to our research team by hospital authorities and who consented in writing to participate on a voluntary basis in the study was included. A standardized self-questionnaire was used at inclusion to collect information about sociodemographic characteristics, previous COVID-19 infection and vaccination. For HCWs who declared to be vaccinated, vaccination cards had been requested if available. Five milliliters (5mL) of blood samples were collected from each participant, centrifuged and plasma stored at -80°C in Centre Pasteur du Cameroun. Plasma samples were subsequently transferred to the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar for further analysis.

The protocol for this study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research (N°2022/07/1880/CE/CNERSH/SP). All included participants signed an informed consent.

2.2. Pseudovirus neutralizing assay

The pseudovirus neutralizing assay is a test to measure the neutralization capacity of antibodies present in the serum of each individual by simulating the presence of the virus using a pseudovirus. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-COV-2 ancestral strain (W) and SARS-COV-2 Omicron BA.2 (BA.2) were measured using SARS-CoV-2 luciferase reporter virus particules (Integral molecular

®, RVP-701L and RVP-770L), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, sera were diluted from 1:10 to 1:5120, pseudoviruses were added and pre-incubated at 37°C for one hour. Cells expressing the receptor of the pathogen here “293T-hsACE2” (Integral, C-HA102) was added in each well and then incubated 72 hours in a 5% CO2 environment under at 37°C. The luminescence (RLU) of the cells was measured on a Microplate Luminometer (Luminoskan™) using Renilla-Glo Luciferase assay system (Promega

®, E2720). RLU was normalized as:

The neutralization titer was determined by analyzing luminescence values and determining the dilution point at which 50% infectivity occurred through a four-parameter regression.

2.3. Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0. Neutralizing antibodies were reported as medians with ranges, and Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare titers among different groups (Madagascar, Cameroon, and CAR / Unvaccinated and Vaccinated). Fischer’s exact tests were employed to compare percentages. All tests were considered statistically significant at a p-value <0.05.

Positivity thresholds were established using a Gaussian mixture model, which identified the threshold by optimizing the log-likelihood function through the expectation maximization algorithm. This method assumes multiple Gaussian underlying distributions (in our case 2) for “negative” and “positive” individuals. The Gaussian mixture model analysis was performed using the Mclust package within R-studio software version 4.2.1.

3. Results

3.1. Study populations

In Madagascar, data collection was conducted from May 13 to June 23, 2022. A total of 558 eligible HCWs were invited to participate and 512 (91.7%) accepted. Participants were predominantly females (59.4%). Physicians represented 21.9% of participants, medical students 14.1%, paramedics 35.4% and other functions (as physiotherapist, lab staff, stretcher-bearer) 28.7%. The median age was 31.1 years (Interquartile range IQR = 26.2-40.9), and 31.2% reported having at least one comorbidity (commonly hypertension, cardiopathy, diabetes, auto-declared obesity, asthma or other pulmonary chronic diseases). At inclusion, 23.8% of participants reported having respiratory symptoms. Among the participants, 64.3% had already been vaccinated at least once, 79.7% had been infected at least once and 26.26% experienced more than one infection. 17.8% were infected during the first wave of COVID-19, 34.2% in the second wave and 34% during the third wave. Among multi-infected individuals, 12.7% of individuals reported being re-infected once while 1.3% reported undergoing reinfection 2 times.

In CAR, samples were collected in May 2022. One-hundred forty-one HCWs were included. The majority were female (63.1%). Among the study participants, physicians comprised 4.2%, while medical students constituted 1.4%, paramedics accounted for 55.3%, and individuals with various roles constituted 39.1%. The median age of the cohort was 43 years (IQR = 26.2 - 40.9). Additionally, 21.6% of participants reported the presence of at least one comorbidity, most commonly hypertension, cardiopathy, diabetes, self-reported obesity, asthma, or other chronic pulmonary diseases.

In Cameroon, data collection was conducted from July to August 2022. Samples of 200 HCW identified during this period were sent to Madagascar. Among these HCW, physicians comprised 7.0%, while medical students constituted 1.0%, paramedics accounted for 58.0%, and individuals with various roles constituted 34.0%. The median age of the cohort was 34.0 years (IQR = 29.0 – 39.5). Additionally, 15.0% of HCW reported the presence of at least one comorbidity, and 61.5% received at least on dose of COVID-19 vaccine confirmed in 91.9% with presentation of a valid vaccination card.

Table 1 shows the detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

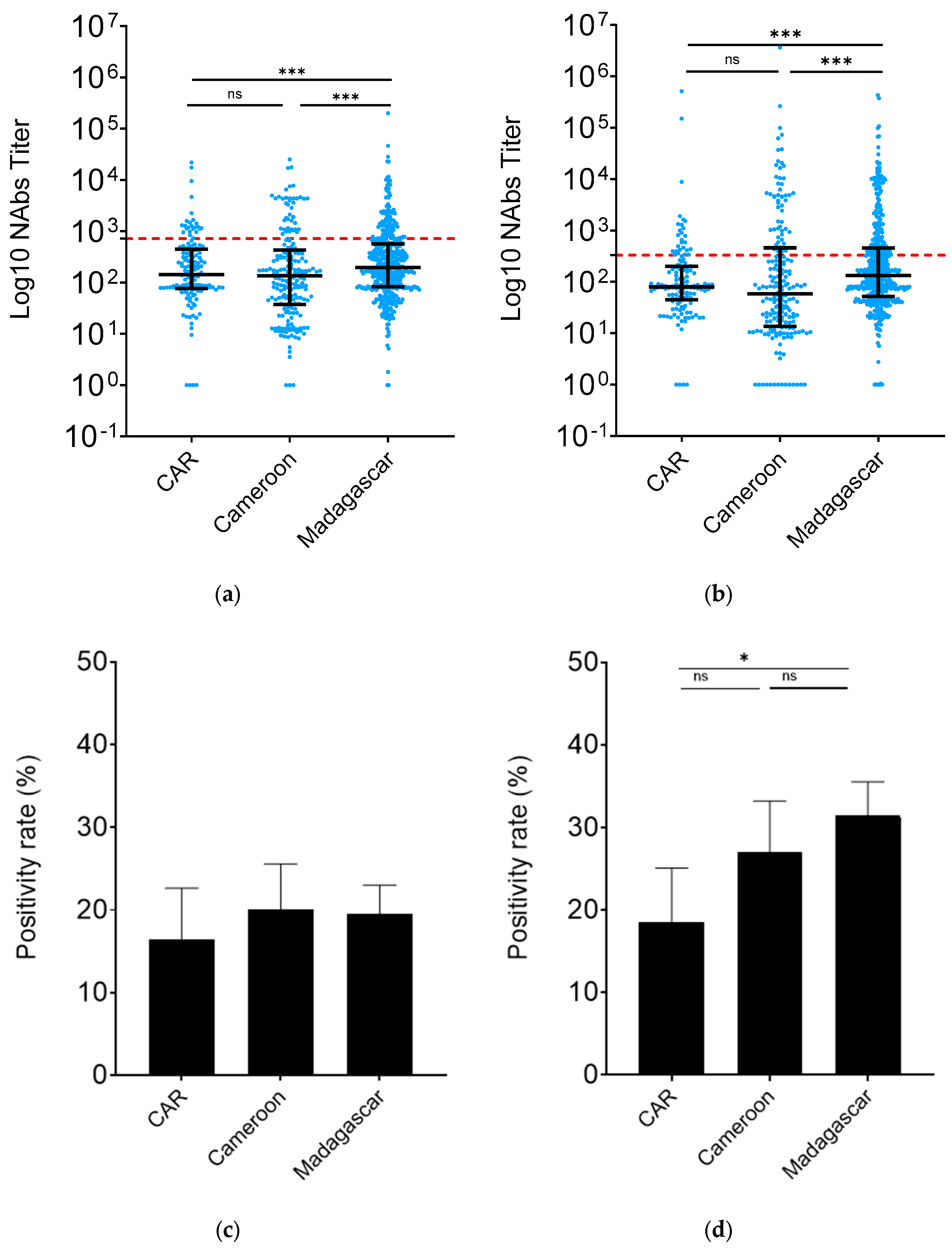

3.2. Madagascar HCW nAb levels were higher than those from CAR and Cameroon

To assess the level of protection against the ancestral W strain and against the BA.2 VoC among HCWs in Madagascar, CAR and Cameroon, we compared the corresponding neutralizing antibody titers (nAbs) in these countries. The findings indicated that the percentage of nAbs against the ancestral strain W was notably higher in Madagascar (Madagascar

vs. CAR,

p=0.03; Madagascar

vs. Cameroon,

p<0.01), while remaining consistent in CAR and Cameroon (

p=0.20) (

Figure 2a). Similar trends were observed in nAb titers against the BA.2 variant. Madagascar exhibited a 2.2-fold increase in anti-BA.2 nAbs compared to Cameroon (

p<0.01) and a 1.6-fold increase compared to CAR (

p<0.01). Conversely, nAb levels were comparable between CAR and Cameroon (

p=0.12) (

Figure 2b).

We then examined the rate of individuals positive by calculating the frequency of individuals with antibodies above the defined threshold. There was no difference in term of neutralization against W (

Figure 2c). In line with the nAb results, the BA.2 nAb positivity rate was significantly higher in Madagascar compared to CAR (31.51%, 95% CI: 27.47- 35.55

vs. 18.57%, 95% CI: 12.05 – 25.09,

p=0. 0.01) (

Figure 2d). Cameroon HCWs (27.00%, 95% CI: 20.79 - 33.21) had nAb positivity rates similar to those of Madagascar and CAR ones.

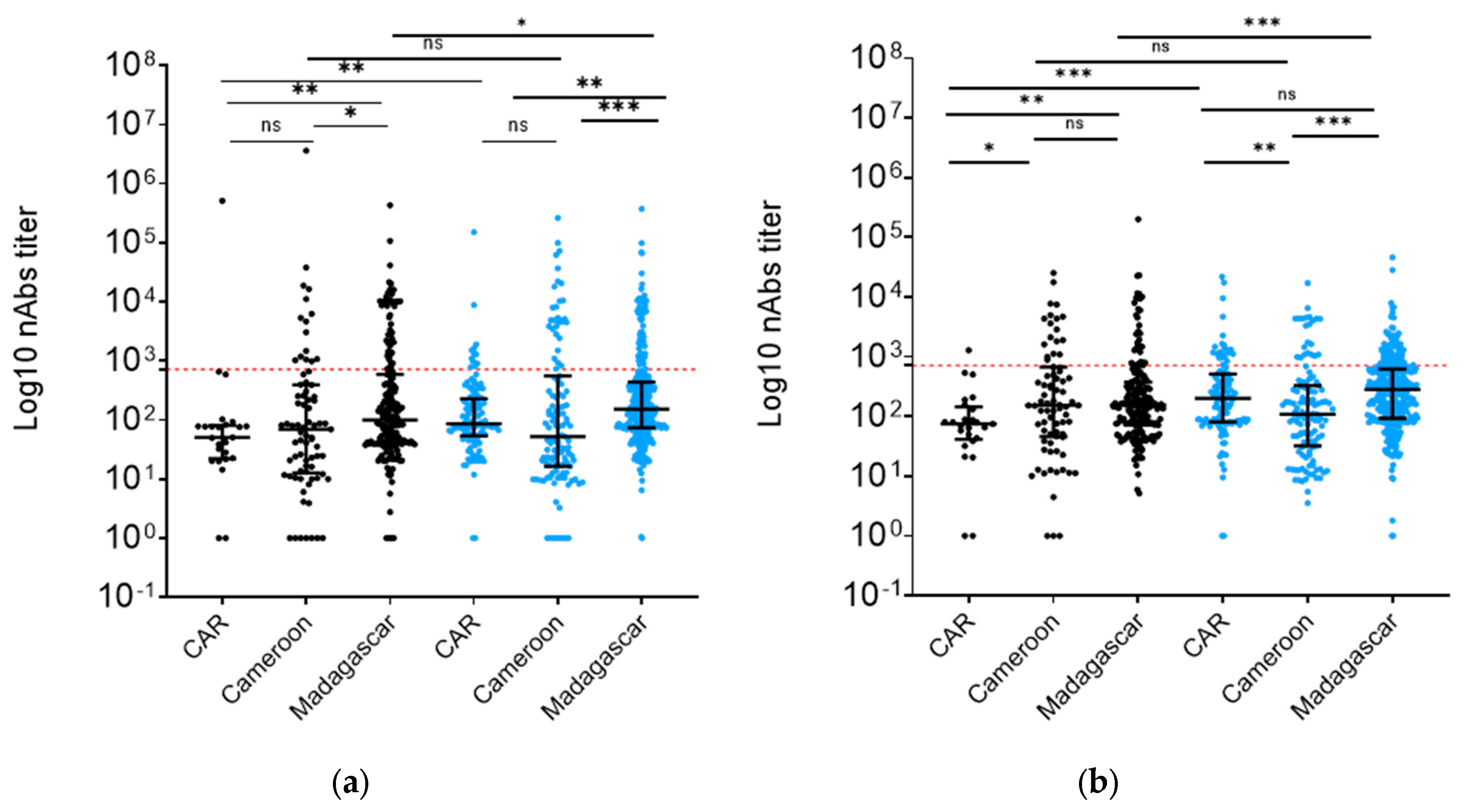

3.3. Vaccination increased nAb levels in Madagascar and CAR but not in Cameroon

We then analyzed nAb levels in differentially vaccinated groups. We found a 2.6-fold increase (

p<0.01) of nAbs against W pseudotyped particles in the samples from CAR vaccinated individuals

vs. their unvaccinated colleagues and a 1.8-fold increase (

p<0.01) in Madagascar vaccinated individuals

vs. theirs (

Figure 3a). Additionally, vaccination appeared to boost BA.2 variant nAb titers in HCW populations by 1.6-fold in Madagascar (

p<0.01) and 1.5-fold in the CAR region (

p=0.04) (

Figure 3b). Interestingly, Cameroon showed no difference in nAb titers against either W or BA.2 (

Figure 3a,b).

A comparative analysis of nAb titers against W variant of SARS-CoV-2 within unvaccinated and vaccinated cohorts across these countries showed that the unvaccinated group in CAR exhibited nAb titers that were two times lower than that observed in Madagascar (

p<0.01) and Cameroon (

p=0.04) (

Figure 3a). Interestingly, Madagascar and Cameroon demonstrated comparable nAb titers against BA.2 (Figure3b). Conversely, within the vaccinated groups, Madagascar HCWs did not exhibit different nAb titers (

p=0.06) from those from CAR, despite a lower vaccination rate in Madagascar (64.7%

vs. 84.2%) (

Figure 3a). In Cameroon vaccinated HCW samples, nAb titers were 2-fold lower than in Madagascar (

p<0.01) and 1.8-fold lower than in CAR (

p<0.01). However, HCWs in Madagascar always showed stronger neutralization against BA.2 in both the unvaccinated (

p<0.01 and

p=0.02) and the vaccinated group (

p<0.01 and

p< 0.01) compared to both CAR and Cameroon. In contrast, CAR and Cameroon samples showed no nAb titer differences in the unvaccinated group (

p=0.08) and vaccinated group (

p=0.61) (

Figure 3b).

Interestingly, the positivity rate of the unvaccinated group against W in Cameroon was higher than in CAR (

p<0.01) and Madagascar (

p<0.01), but no significant difference was observed concerning the vaccinated group. The same trend was observed for BA.2 nAbs, even though this did not reach significance in the unvaccinated group (

Figure 3c,d).

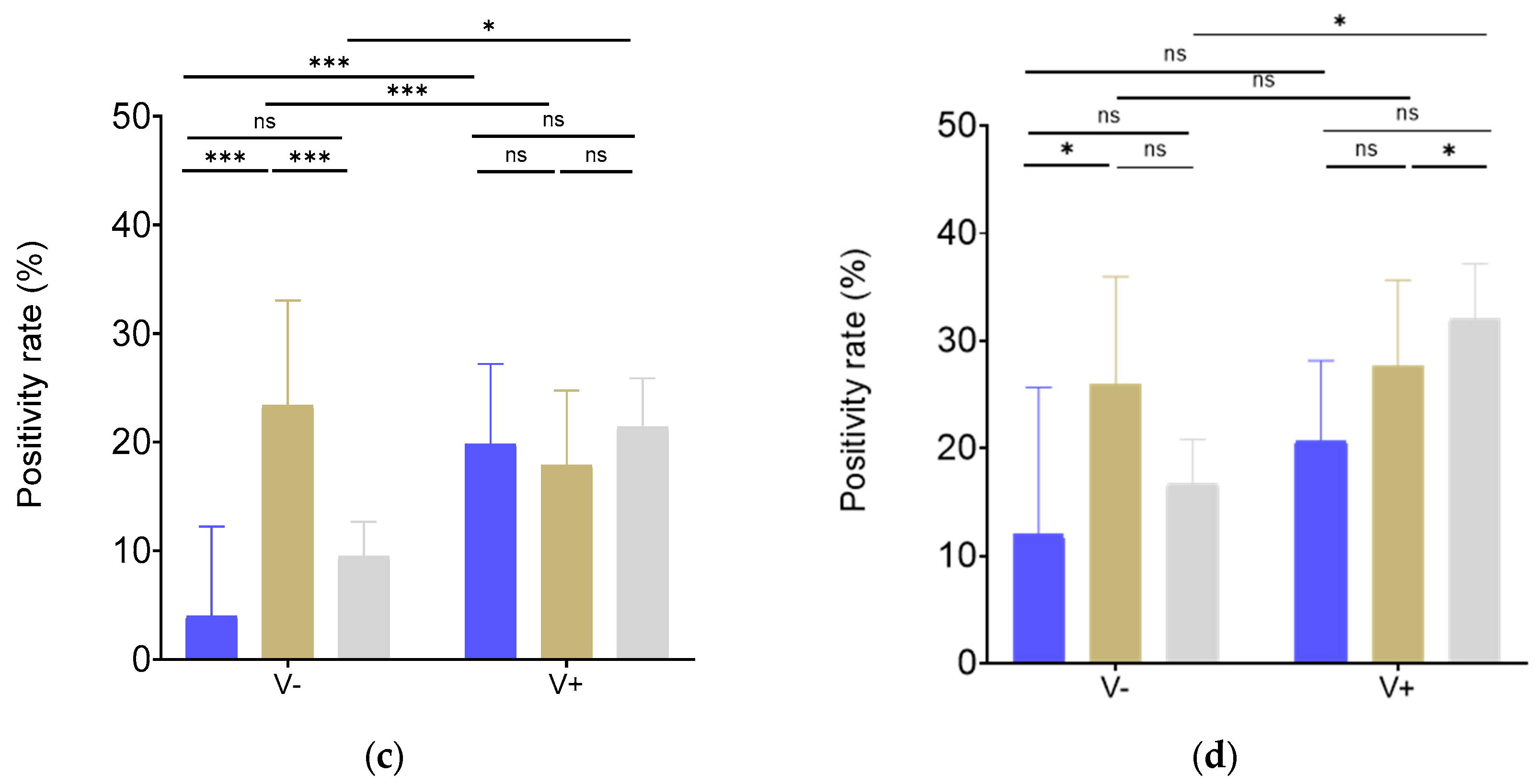

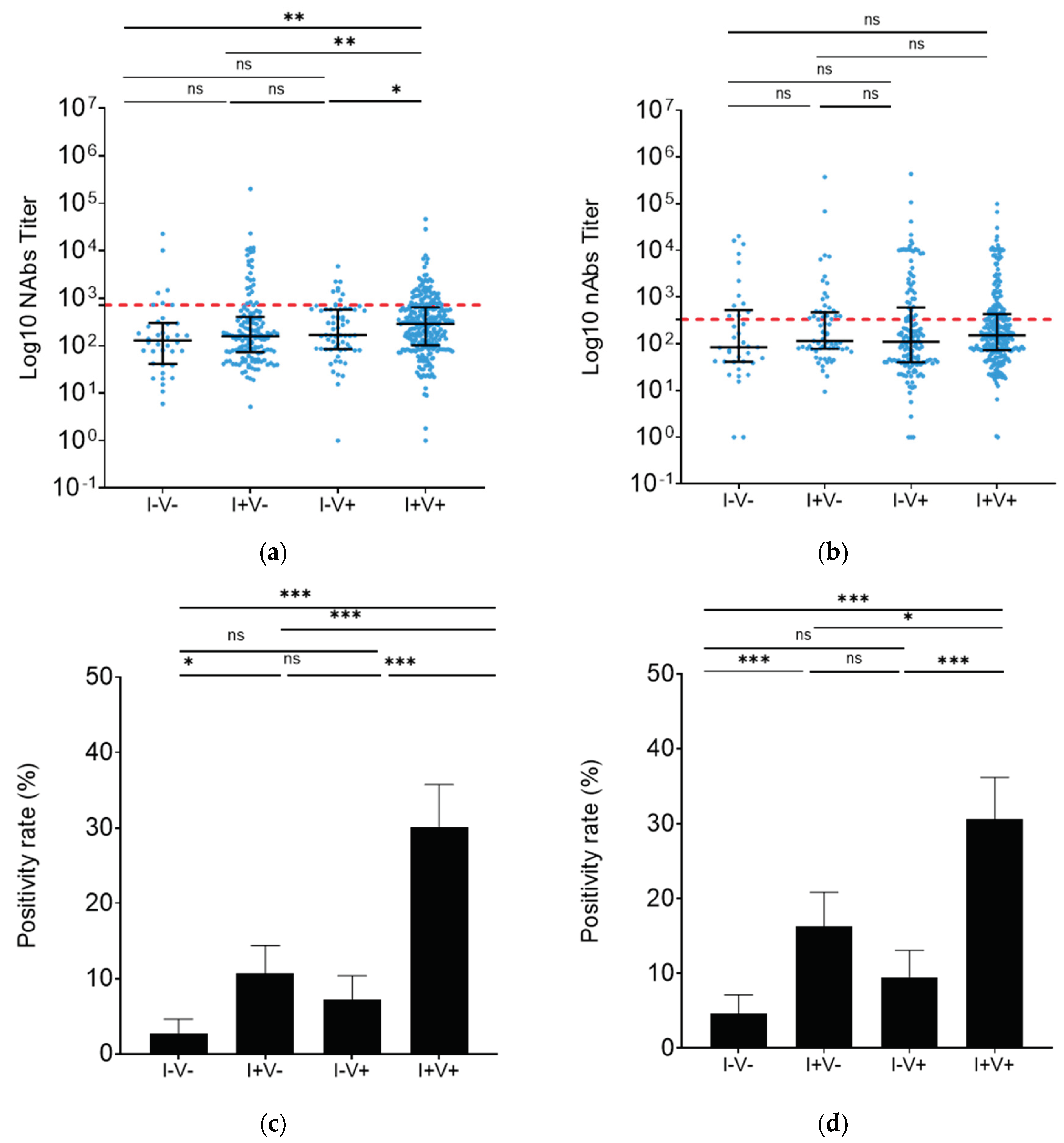

3.4. Vaccination and infection provided similar BA.2 neutralization in Madagascar

To further investigate in the implications of different types of immunization, participants from Madagascar were classified into 4 groups: 38 unvaccinated/uninfected (I-V-), 146 unvaccinated/infected (I+V-), 65 vaccinated/uninfected (I-V+) and 262 vaccinated/infected (I+V+). In the I+V+ group, W strain neutralization was 2.3 times higher than in the I-V- group (

p<0.01) and 1.8 times higher than in the I+V- group (

p<0.01) (

Figure 4a). Moreover, infected groups appeared to have a higher positivity rate independently of previous vaccination (I-V-

vs. I+V-:

p<0.01, I-V-

vs. I-V+:

p=0.55, I-V-

vs. I+V+:

p=0.14; I+V-

vs. I-V+:

p<0.01, I+V-

vs. I+V+:

p=0.02, I-V+

vs. I+V+:

p <0.50) (

Figure 4c).

On the other hand, nAb levels against BA.2 were similar for all analyzed groups (

Figure 4b). However, consistent with the response against W, the nAb positivity rate in the surveyed infected groups was higher regardless of vaccination status (I-V-

vs. I+V-:

p=0.03, I-V-

vs. I-V+:

p=0.06, I-V-

vs. I+V+:

p=0.18; I+V-

vs. I-V+:

p<0.01, I+V-

vs. I+V+:

p=0.57, I-V+

vs. I+V+:

p<0.01) (

Figure 4d).

Among unvaccinated individuals who declared having been infected only once, 3.45 % reported infection during the 1

st wave, 13.95% reported infection during the 2

nd wave and 27.9 % reported infection during the 3

rd wave (

Supplementary Figure S1A). BA.2 nAb titers tended to gradually decrease over time since last reported infection. Indeed, individuals infected only during the first wave seemed to have a lower response than those infected during the second or third wave, although the differences did not reach significance due to the small size of the analyzed group (Supplementary

Figure S1B and S1C).

4. Discussion

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at an elevated risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to the general population, due to their frequent exposure to contagious individuals. The implementation of appropriate infection prevention and control programs is crucial to safeguard HCWs. However, the availability of collective and personal protective equipment remains limited, especially in Africa. Even low-cost interventions such as facemasks and water supply for handwashing may be challenging in this particular setting [

21]. The scope of this study focused on HCWs in three African countries: Madagascar, Cameroon and the Central African Republic (CAR). Remarkably, these countries exhibited nearly identical seroprevalence rates, with 95% (Madagascar) [

8], 98.4% (Cameroon) [

22] and 95.7% (CAR) [

23] respectively. These high seroprevalences indicates that a substantial proportion of HCWs have been exposed to the virus, making these populations valuable targets for comparative immunization studies. Notably, HCWs represent an important group for monitoring and evaluating infection and immunity trends in Africa [

24], including the assessment of vaccination efficacy. As this group plays a central role in the healthcare system, understanding their immunization status can shed light on the effectiveness of vaccination efforts in the region.

At the beginning of this study, vaccination rates in the study population in Madagascar, Cameroon and CAR were respectively 64.3%, 58.0% and 82.2%. The vaccination rate among HCWs in Madagascar was comparable to that reported in HCWs across Africa (65.6%) but lower than the global average (77.3%) [

25]. By April 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that 65% of Africans had already been infected by BA.2 subvariant. The current study thus represents the first report of HCW protection against VOC BA.2 profiles (neutralization potential) in Madagascar, Cameroon and the CAR, before it being detected in these countries [

26]. The level of protection was assessed by measuring the neutralizing antibodies, as previous research has demonstrated that a high level of neutralizing antibodies could serve as a good predictor of protection against COVID-19 [

27]. Our results revealed a similar level of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against the Wuhan strain (W) in both Cameroon and CAR, while it was higher in Madagascar. Prior studies have demonstrated the ability of our immune system to better eliminate this ancestral strain W following Omicron immunization [

28,

29]. Additionally, vaccination has been found to reinforce protection against the Wuhan strain infection. Indeed, the initial vaccines were developed from this strain [

30]. In line with these observations, our results indicate that vaccinated groups exhibited the strongest response against strain W in Madagascar and CAR (

Figure 3a). Interestingly, vaccinated HCWs in Madagascar showed the same level of neutralization activity as those in CAR, despite the low vaccination coverage, suggesting stronger immunization resulting from infections [

8,

31]. This result was confirmed by a high level of infection reported in the Malagasy HCW population (79.7%) and the serological result assessing IgG anti-S1, anti-RBD and anti-NP, which revealed that Madagascar’s HCWs had higher NP titers corresponding to a more recent natural infection [

32] (

Supplementary Figure S2). On the other hand, we found that the rate of individuals neutralizing W in the unvaccinated group in Cameroon was higher (

Figure 3c,d) compared to the unvaccinated groups in CAR and Madagascar, despite only 22% reported a previous infection. This surprising result could be due to low reporting and/or little symptomatic presentation in a context of high natural immunization (four successive waves) [

4]. WHO has indeed stated that the reported number of COVID-19 infection cases in Cameroon was underestimated [

33].

Focusing on HCWs in Madagascar, participants were classified based on their known past immunization history. Individuals who had both been infected and vaccinated showed higher neutralization activities of W pseudotyped particles compared to vaccinated and uninfected or unvaccined individuals. This data is consistent with previously reports that suggest that hybrid immunity resulting from both infection and vaccination confers better protection than vaccination or infection alone [

34,

35]. Our results further support the effectiveness of vaccination in providing protection against strain W.

Subsequently, we investigated preexisting immunization against BA.2, anticipating a future potential variant that had not yet circulated at the time of the study. HCW samples from CAR did not exhibit, or only exhibited a weak response, against BA.2, suggesting a mild preexisting immunity. Malagasy HCWs however showed higher BA.2 neutralization potential. This finding can be attributed to the overall population that was heavily re-infected during the 3

rd bimodal wave without particular clinical symptom presentation in line with little triple infection reporting [

36]. This may as well be associated to an efficient cellular response to SARS-CoV-2 having led to fewer symptomatic presentations [

7]. Moreover, Omicron infections have been generally reported to be asymptomatic or less severe [

37]. Cameroon samples from unvaccinated and vaccinated groups exhibited similar BA.2 nAbs levels (

Figure 3a,b). Moreover, non-infected unvaccinated individuals also showed high nAb levels (

Supplementary Figure S3), indicating possible under-reporting during the third wave in this country.

The current study however has limitations that should be acknowledged. All collected information was not collected uniformly across all countries, preventing sub-populational analysis in all countries. Previous infections were self-reported only. Additionally, vaccination strategies, including details such as the vaccine manufacturers and the number of vaccine doses received, were not included in the analysis of all countries.

Our findings revealed notable differences in the immunity developed by HCWs in Madagascar, Cameroon and the CAR at the time of the study, despite the general population in these countries undergoing apparently similar immunizations. The BA.2 neutralization potential was increased in HCWs from Madagascar suggesting readiness in the study population, perhaps due to the singularity of strain associated wave successions in this country. Previous infections appeared to play a role in the level of nAbs in HCWs. Cameroon and Madagascar showed higher rates of individuals able to neutralize the Omicron variant efficiently compared to CAR. These findings underscore the complex interplay between natural immunity that we were unable to integrate, vaccination, and the dynamics of different strains in shaping the epidemiological landscape of the pandemic in these African regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: MS, RVR, RR, MCT; Formal Analysis: DJNM.; Investigation: MS, RVR, RR, MCT, AM; Resources: FR, PATN, HAA, JMMN, BM, PCTA, PP, RNB, CSGC.; Data Curation: DJNM; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: DJNM.; Writing – Review & Editing: DJNM, PATN, MS, RVR, RR, MCT, AR; Supervision: MS, RR, MCT; Funding Acquisition: MS, RVR, MCT, AM.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the MediLabSecure project, the REPAIR project funded by the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, and Institut Pasteur, which acted as the project coordinator. The MediLabSecure project is financially supported by the European Union (FPI IFS/2018/402-247). Views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the European Commission.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Vanessa Lagal, Koussay Dellagi and Vincent Richard who supported us in coordinating activities in Pasteur network and provided manuscript reviewing. The authors thank all of the health care workers from this study for having accepted to participate. We are also grateful to Dr Vaomalala RAHARIMANGA and Mireille RAZAFINDRAKOTO AMBINITSOA who helped us during the study (data and samples collection, logistical aspects).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Gebrecherkos, T.; Kiros, Y.K.; Challa, F.; Abdella, S.; Gebreegzabher, A.; Leta, D.; Desta, A.; Hailu, A.; Tasew, G.; Abdulkader, M.; et al. Longitudinal Profile of Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with COVID-19 in a Setting from Sub-Saharan Africa: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salyer, S.J.; Maeda, J.; Sembuche, S.; Kebede, Y.; Tshangela, A.; Moussif, M.; Ihekweazu, C.; Mayet, N.; Abate, E.; Ouma, A.O.; et al. The First and Second Waves of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study. The Lancet 2021, 397, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiya, Y.; Ekofo, J.; Kabanga, C.; Agyepong, I.; Van Damme, W.; Van Belle, S.; Mukinda, F.; Chenge, F. Multilevel Governance and Control of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Learning from the Four First Waves. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Sun, K.; Tempia, S.; Kleynhans, J.; von Gottberg, A.; McMorrow, M.L.; Wolter, N.; Bhiman, J.N.; Moyes, J.; Carrim, M.; Martinson, N.A.; et al. Rapidly Shifting Immunologic Landscape and Severity of SARS-CoV-2 in the Omicron Era in South Africa. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GISAID - HCoV-19 Variants Dashboard.

- Razafimahatratra, S.L.; Ndiaye, M.D.B.; Rasoloharimanana, L.T.; Dussart, P.; Sahondranirina, P.H.; Randriamanantany, Z.A.; Schoenhals, M. Seroprevalence of Ancestral and Beta SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Malagasy Blood Donors. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1363–e1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razafimahatratra, S.L.; Andriatefy, O.H.; Mioramalala, D.J.N.; Tsatoromila, F.A.M.; Randrianarisaona, F.; Dussart, P.; Schoenhals, M. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 Immunizations of an Unvaccinated Population Lead to Complex Immunity. A T Cell Reactivity Study of Blood Donors in Antananarivo. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekliz, M.; Adea, K.; Vetter, P.; Eberhardt, C.S.; Hosszu-Fellous, K.; Vu, D.-L.; Puhach, O.; Essaidi-Laziosi, M.; Waldvogel-Abramowski, S.; Stephan, C.; et al. Neutralization Capacity of Antibodies Elicited through Homologous or Heterologous Infection or Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.-A.; Kassanjee, R.; Rousseau, P.; Morden, E.; Johnson, L.; Solomon, W.; Hsiao, N.-Y.; Hussey, H.; Meintjes, G.; Paleker, M.; et al. Outcomes of Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Omicron-Driven Fourth Wave Compared with Previous Waves in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health TM IH 2022, 27, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilibic-Cavlek, T.; Stevanovic, V.; Kovac, S.; Borko, E.; Bogdanic, M.; Miletic, G.; Hruskar, Z.; Ferenc, T.; Coric, I.; Vujica Ferenc, M.; et al. Neutralizing Activity of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Patients with COVID-19 and Vaccinated Individuals. Antibodies 2023, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.J.; Franchini, M.; Joyner, M.J.; Casadevall, A.; Focosi, D. Analysis of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-Neutralizing Antibody Titers in Different Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Convalescent Plasma Sources. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarawneh, H.N.; Chemaitelly, H.; Ayoub, H.H.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; Smatti, M.K.; Coyle, P.; Al-Kanaani, Z.; et al. Effects of Previous Infection and Vaccination on Symptomatic Omicron Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawanshi, R.K.; Chen, I.P.; Ma, T.; Syed, A.M.; Brazer, N.; Saldhi, P.; Simoneau, C.R.; Ciling, A.; Khalid, M.M.; Sreekumar, B.; et al. Limited Cross-Variant Immunity from SARS-CoV-2 Omicron without Vaccination. Nature 2022, 607, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Karim, F.; Cele, S.; Reedoy, K.; San, J.E.; Lustig, G.; Tegally, H.; Rosenberg, Y.; Bernstein, M.; Jule, Z.; et al. Omicron Infection Enhances Delta Antibody Immunity in Vaccinated Persons. Nature 2022, 607, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinger, P.; Ohradanova-Repic, A.; Valenta, R. Importance, Applications and Features of Assays Measuring SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Nassereldine, H.; Sorensen, R.J.D.; Amlag, J.O.; Bisignano, C.; Byrne, S.; Castro, E.; Coberly, K.; Collins, J.K.; Dalos, J.; et al. Past SARS-CoV-2 Infection Protection against Re-Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Lancet 2023, 401, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccination Contre La COVID-19 Dans La Région Africaine de l’OMS-Bulletin Mensuel, Juin 2022-Uganda|ReliefWeb. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/vaccination-contre-la-covid-19-dans-la-region-africaine-de-loms-bulletin-mensuel-juin-2022 (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Caring for People Who Care: Supporting Health Workers during the COVID 19 Pandemic. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 28. [CrossRef]

- Figa, Z.; Temesgen, T.; Zemeskel, A.G.; Ganta, M.; Alemu, A.; Abebe, M.; Ashuro, Z. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine among Healthcare Workers in Africa, Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Public Health Pract. 2022, 4, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chersich, M.F.; Gray, G.; Fairlie, L.; Eichbaum, Q.; Mayhew, S.; Allwood, B.; English, R.; Scorgie, F.; Luchters, S.; Simpson, G.; et al. COVID-19 in Africa: Care and Protection for Frontline Healthcare Workers. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandie, A.B.; Ngo Sack, F.; Medi Sike, C.I.; Mendimi Nkodo, J.; Ngegni, H.; Ateba Mimfoumou, H.G.; Lobe, S.A.; Choualeu Noumbissi, D.; Tchuensou Mfoubi, F.; Tagnouokam Ngoupo, P.A.; et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Adult Populations in Cameroon: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study Among Blood Donors in the Cities of Yaoundé and Douala. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirakiza, A.; Malaka, C.; Mossoro-Kpinde, H.D.; Yambiyo, B.M.; Mossoro-Kpinde, C.D.; Fandema, E.; Yakola, C.N.; Doyama-Woza, R.; Kangale-Wando, I.M.; Komba, J.E.K.; et al. Seroprevalence of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies before and after Implementation of Anti-COVID-19 Vaccination among Hospital Staff in Bangui, Central African Republic. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratovoson, R.; Raberahona, M.; Razafimahatratra, R.; Randriamanantsoa, L.; Andriamasy, E.H.; Herindrainy, P.; Razanajatovo, N.; Andriamandimby, S.F.; Rakotonaivo, A.; Randrianarisaona, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Rate in Antananarivo Frontline Health Care Workers, Madagascar. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2022, 16, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Mariolis-Sapsakos, T.; Kaitelidou, D. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GISAID-HCoV-19 Variants Dashboard. Available online: https://gisaid.org/hcov-19-variants-dashboard/ (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Khoury, D.S.; Cromer, D.; Reynaldi, A.; Schlub, T.E.; Wheatley, A.K.; Juno, J.A.; Subbarao, K.; Kent, S.J.; Triccas, J.A.; Davenport, M.P. Neutralizing Antibody Levels Are Highly Predictive of Immune Protection from Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medits, I.; Springer, D.N.; Graninger, M.; Camp, J.V.; Höltl, E.; Aberle, S.W.; Traugott, M.T.; Hoepler, W.; Deutsch, J.; Lammel, O.; et al. Different Neutralization Profiles After Primary SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 Infections. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 946318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, D.N.; Traugott, M.; Reuberger, E.; Kothbauer, K.B.; Borsodi, C.; Nägeli, M.; Oelschlägel, T.; Kelani, H.; Lammel, O.; Deutsch, J.; et al. A Multivariant Surrogate Neutralization Assay Identifies Variant-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Profiles in Primary SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Infection. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakshit, S.; Babji, S.; Parthiban, C.; Madhavan, R.; Adiga, V.; J, S.E.; Chetan Kumar, N.; Ahmed, A.; Shivalingaiah, S.; Shashikumar, N.; et al. Polyfunctional CD4 T-Cells Correlating with Neutralising Antibody Is a Hallmark of COVISHIELDTM and COVAXIN® Induced Immunity in COVID-19 Exposed Indians. Npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.; Foulkes, S.; Insalata, F.; Kirwan, P.; Saei, A.; Atti, A.; Wellington, E.; Khawam, J.; Munro, K.; Cole, M.; et al. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after Covid-19 Vaccination and Previous Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešević, J.; Lacey, B.; Callen, H.; Omiyale, W.; Conroy, M.; Feng, Q.; Crook, D.W.; Doherty, N.; Ebner, D.; Eyre, D.W.; et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies over 18 Months Following Infection: UK Biobank COVID-19 Serology Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2024, 78, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandie, A.B.; Tejiokem, M.C.; Faye, C.M.; Hamadou, A.; Abah, A.A.; Mbah, S.S.; Tagnouokam-Ngoupo, P.A.; Njouom, R.; Eyangoh, S.; Abanda, N.K.; et al. Observed versus Estimated Actual Trend of COVID-19 Case Numbers in Cameroon: A Data-Driven Modelling. Infect Model 2023, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, M.C.; Ye, L.; Duffy, E.R.; Cole, M.; Gawel, S.H.; Werler, M.M.; Daghfal, D.; Andry, C.; Kataria, Y. Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 Serum Antibodies Through the Alpha, Delta, and Omicron Surges Among Vaccinated Health Care Workers at a Boston Hospital. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decru, B.; Van Elslande, J.; Steels, S.; Van Pottelbergh, G.; Godderis, L.; Van Holm, B.; Bossuyt, X.; Van Weyenbergh, J.; Maes, P.; Vermeersch, P. IgG Anti-Spike Antibodies and Surrogate Neutralizing Antibody Levels Decline Faster 3 to 10 Months After BNT162b2 Vaccination Than After SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Healthcare Workers. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.J.; Swadling, L.; Gibbons, J.M.; Pade, C.; Jensen, M.P.; Diniz, M.O.; Schmidt, N.M.; Butler, D.K.; Amin, O.E.; Bailey, S.N.L.; et al. Discordant Neutralizing Antibody and T Cell Responses in Asymptomatic and Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabf3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Luo, K.; Guo, Y.; Fang, M.; Sun, Q.; Dai, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhan, Z.; Hu, S.; Chen, T.; et al. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Clinical Severity of Omicron and Delta Variants. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).