Submitted:

14 February 2024

Posted:

19 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Transposable Elements in the C. elegans Genome

| Element | Class | Order | Superfamily | Family | Copy Num-ber | Length (bp) | Catal-ytic motif | IR / TIR length (bp) | Target site (duplication) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cer1 | Class I | LTR | Gypsy | Gypsy | 1 | 8865 | DDE | 492 | |

| Tc1 | Class II | TIR | Tc1/mariner | Tc1 | 32 | 1611 | DD34E | 54 | TA (TA-TA) |

| Tc2 | Class II | TIR | Tc1/mariner-Tc2/pogo group | Pogo | 4 | 2074 | DD35D | 24 | TA (TA-TA) |

| Tc3 | Class II | TIR | Tc1/mariner | Tc1 | 22 | 2335 | DD34E | 462 | TA (TA-TA) |

| Tc4/Tc4v | Class II | TIR | Tc1/mariner- Tc4 group |

Tc4 | 10 | 1605/ 3483 | DD37D | 774 | CTNAG (TNA-TNA) |

| Tc5 | Class II | TIR | Tc1/mariner- Tc4 group |

Tc4 | 4 | 3171 | DD37D | 491 | CTNAG (TNA-TNA) |

| Tc7 (Tc1 MITE) | Class II | TIR | Tc1/mariner | Tc1 | 11 | 921 | n/a |

345 | TA (TA-TA) |

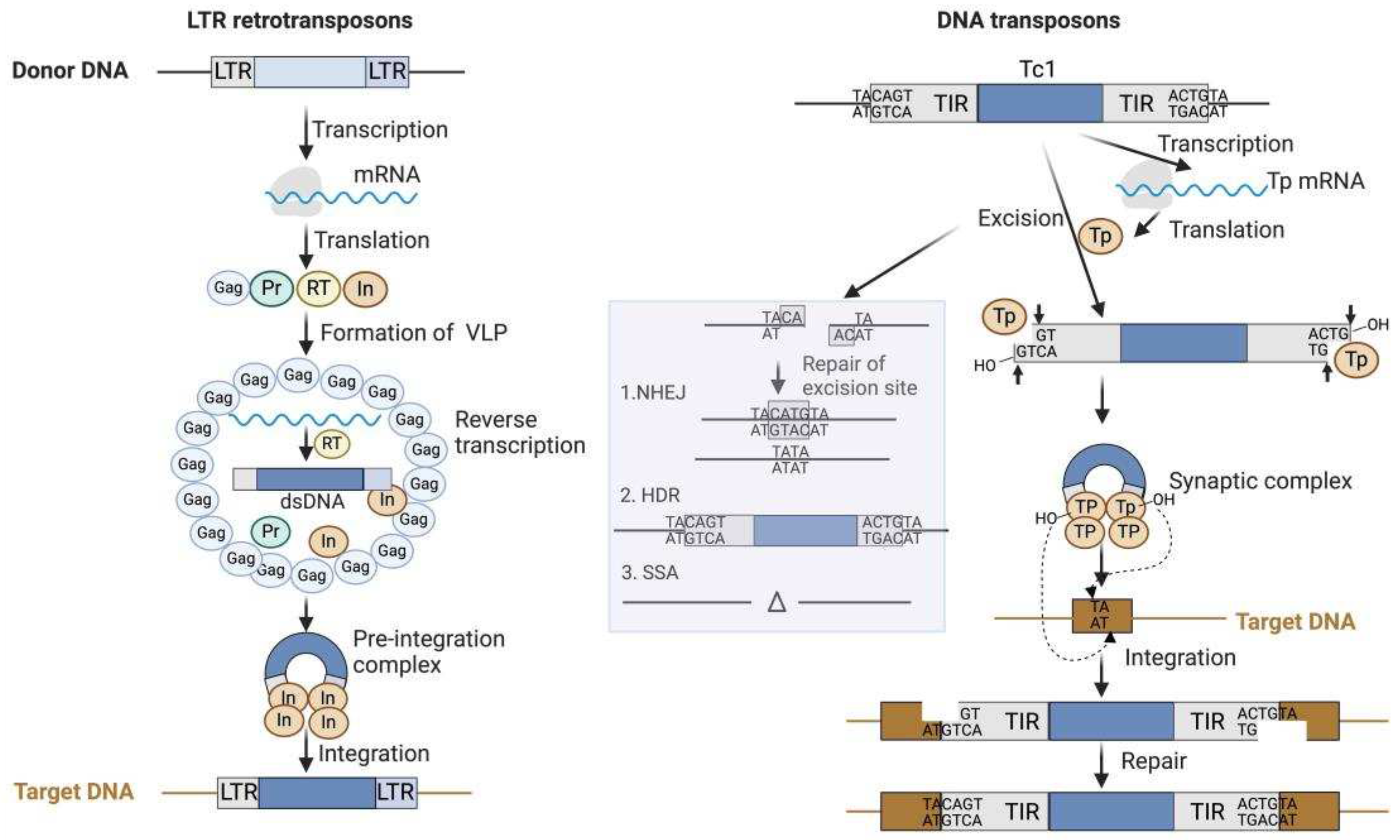

3. Mechanisms of Transposition in C. elegans

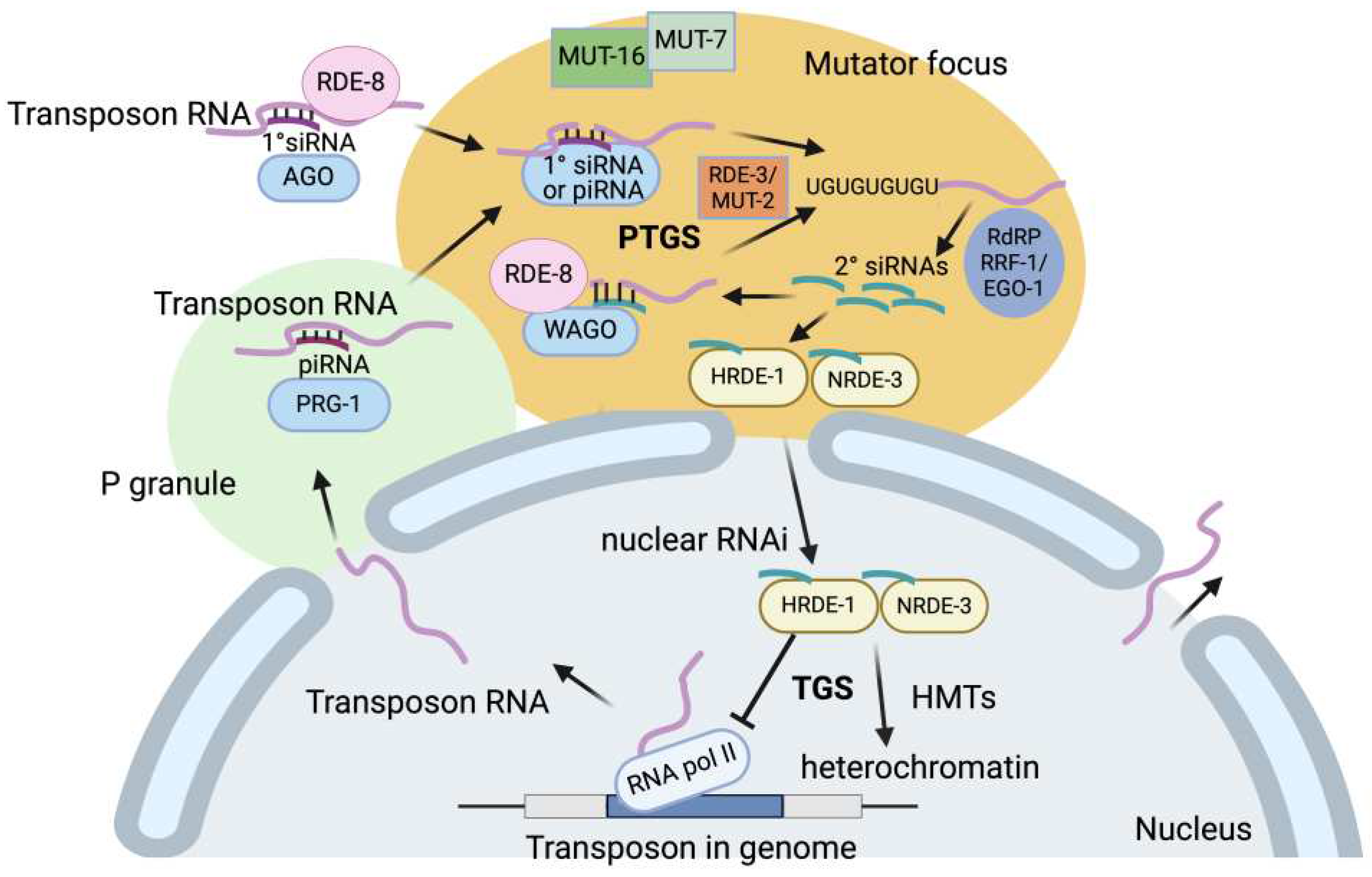

4. Silencing of Transposable Elements

5. Other Mechanisms of Transposon Regulation: Adaptation and Domestication

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- B. McClintock, “The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 344–355, 1950. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Laricchia, S. Zdraljevic, D.E. Cook, and E. C. Andersen, “Natural Variation in the Distribution and Abundance of Transposable Elements Across the Caenorhabditis elegans Species.,” Mol Biol Evol, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 2187–2202, Sep. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx155. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Lander et al., “Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome.,” Nature, vol. 409, no. 6822, pp. 860–921, Feb. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1038/35057062. [CrossRef]

- P. Capy, G. Gasperi, C. Biémont, and C. Bazin, “Stress and transposable elements: co-evolution or useful parasites?,” Heredity, vol. 85, no. 2, pp. 101–106, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00751.x. [CrossRef]

- N. Saksouk, E. Simboeck, and J. Déjardin, “Constitutive heterochromatin formation and transcription in mammals,” Epigenetics Chromatin, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 3, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8935-8-3. [CrossRef]

- J. W. K. Ho et al., “Comparative analysis of metazoan chromatin organization,” Nature, vol. 512, no. 7515, pp. 449–452, Apr. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13415. [CrossRef]

- N. McMurchy et al., “A team of heterochromatin factors collaborates with small RNA pathways to combat repetitive elements and germline stress,” Elife, vol. 6, p. e21666, 2017. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.21666. [CrossRef]

- J. Ahringer and S. M. Gasser, “Repressive Chromatin in Caenorhabditis elegans: Establishment, Composition, and Function,” Genetics, vol. 208, no. 2, pp. 491–511, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.117.300386. [CrossRef]

- N. V. Fedoroff, “Transposable Elements, Epigenetics, and Genome Evolution,” Science, vol. 338, no. 6108, pp. 758–767, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.338.6108.758. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gracia, X. Maside, and B. Charlesworth, “High rate of horizontal transfer of transposable elements in Drosophila.,” Trends Genet. : TIG, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 200–3, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.001. [CrossRef]

- H.-H. Zhang, J. Peccoud, M.-R.-X. Xu, X.-G. Zhang, and C. Gilbert, “Horizontal transfer and evolution of transposable elements in vertebrates.,” Nat. Commun., vol. 11, no. 1, p. 1362, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15149-4. [CrossRef]

- S. Brenner, “The Genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans,” p. 1 24, Oct. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [CrossRef]

- C. elegans S. Consortium, “Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology,” Science, vol. 282, no. 5396, pp. 2012–2018, Dec. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Eide and P. Anderson, “Novel Insertion Mutation in Caenorhabditis elegans,” Mol. Cell. Biol., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 1985. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.5.1.1-6.1985. [CrossRef]

- D. Eide and P. Anderson, “Transposition of Tc1 in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 82, no. 6, pp. 1756–1760, 1985. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.82.6.1756. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Emmons, L. Yesner, K. Ruan, and D. Katzenberg, “Evidence for a transposon in caenorhabditis elegans,” Cell, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 55–65, 1983. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(83)90496-8. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Hunter et al., “Functional Genomic Analysis of the let-7 Regulatory Network in Caenorhabditis elegans,” PLoS Genetics, vol. 9, no. 3, p. e1003353, Mar. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003353.s006. [CrossRef]

- T. Wicker et al., “A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements,” Nat. Rev. Genet., vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 973–982, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2165. [CrossRef]

- Y. Arata, P. Jurica, N. Parrish, and Y. Sako, “Comprehensive identification of potentially functional genes for transposon mobility in the C. elegans genome,” bioRxiv, p. 2023.08.08.552548, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552548. [CrossRef]

- T. Oosumi, B. Garlick, and W. R. Belknap, “Identification of putative nonautonomous transposable elements associated with several transposon families inCaenorhabditis elegans,” J. Mol. Evol., vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 11–18, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02352294. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Moerman and R. H. Waterston, “Spontaneous unstable unc-22 IV mutations in C. elegans var. Bergerac.,” Genetics, vol. 108, no. 4, pp. 859–77, 1984. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/108.4.859. [CrossRef]

- J. Collins, B. Saari, and P. Anderson, “Activation of a transposable element in the germ line but not the soma of Caenorhabditis elegans,” Nature, vol. 328, no. 6132, pp. 726–728, 1987. https://doi.org/10.1038/328726a0. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Ketting, T.H. Haverkamp, H.G. van Luenen, and R. H. Plasterk, “Mut-7 of C. elegans, required for transposon silencing and RNA interference, is a homolog of Werner syndrome helicase and RNaseD.,” Cell, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 133–141, Oct. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81645-1. [CrossRef]

- H. Tabara et al., “The rde-1 gene, RNA interference, and transposon silencing in C. elegans.,” Cell, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 123–132, Oct. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81644-x. [CrossRef]

- N. K. Egilmez and R. J. S. Reis, “Age-dependent somatic excision of transposable element Tc1 in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Mutation research, vol. 316, no. 1, pp. 17–24, Feb. 1994. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81644-x. [CrossRef]

- T. Daigle, T.C. Deiss, R.H. Melde, U. Bergthorsson, and V. Katju, “Bergerac strains of Caenorhabditis elegans revisited: expansion of Tc1 elements imposes a significant genomic and fitness cost,” G3: GenesGenomesGenet., vol. 12, no. 11, p. jkac214, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkac214. [CrossRef]

- J. Collins, E. Forbes, and P. Anderson, “The Tc3 family of transposable genetic elements in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Genetics, vol. 121, no. 1, pp. 47–55, 1989. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/121.1.47. [CrossRef]

- Mori, D.G. Moerman, and R. H. Waterston, “Analysis of a mutator activity necessary for germline transposition and excision of Tc1 transposable elements in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Genetics, vol. 120, no. 2, pp. 397–407, 1988. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/120.2.397. [CrossRef]

- R. Rezsohazy, H.G.A.M. van Luenen, R.M. Durbin, and R. H. A. Plasterk, “Tc7, a Tc1-hitch hiking transposon in Caenorhabditis elegans,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 25, no. 20, pp. 4048–4054, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.20.4048. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan, M. Finney, N. Tsung, and H. R. Horvitz, “Tc4, a Caenorhabditis elegans transposable element with an unusual fold-back structure.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 88, no. 8, pp. 3334–3338, 1991. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.8.3334. [CrossRef]

- W. Li and J. E. Shaw, “A variant Tc4 transposable element in the nematode C.elegans could encode a novel protein,” Nucleic Acids Res., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 59–67, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/21.1.59. [CrossRef]

- J. Collins and P. Anderson, “The Tc5 family of transposable elements in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Genetics, vol. 137, no. 3, pp. 771–781, 1994. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/137.3.771. [CrossRef]

- Levitt and S. W. Emmons, “The Tc2 transposon in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 86, no. 9, pp. 3232–3236, 1989. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.86.9.3232. [CrossRef]

- Dupeyron, T. Baril, C. Bass, and A. Hayward, “Phylogenetic analysis of the Tc1/mariner superfamily reveals the unexplored diversity of pogo-like elements.,” Mob. DNA, vol. 11, p. 21, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-020-00212-0. [CrossRef]

- R. H. A. Plasterk, Z. Izsvák, and Z. Ivics, “Resident aliens: the Tc1/mariner superfamily of transposable elements,” Trends Genet., vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 326–332, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01777-1. [CrossRef]

- Bannert and R. Kurth, “Retroelements and the human genome: New perspectives on an old relation,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 101, no. suppl_2, pp. 14572–14579, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0404838101. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Britten, “Active gypsy/Ty3 retrotransposons or retroviruses in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 92, no. 2, p. 599 601, Jan. 1995. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.2.599. [CrossRef]

- G. Frame, J.F. Cutfield, and R. T. M. Poulter, “New BEL-like LTR-retrotransposons in Fugu rubripes, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster,” Gene, vol. 263, no. 1–2, pp. 219–230, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00567-9. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Ganko, V. Bhattacharjee, P. Schliekelman, and J. F. McDonald, “Evidence for the contribution of LTR retrotransposons to C. elegans gene evolution.,” Mol Biol Evol, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 1925–1931, Nov. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msg200. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Ganko, K.T. Fielman, and J. F. McDonald, “Evolutionary history of Cer elements and their impact on the C. elegans genome.,” Genome Res, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 2066 2074, Dec. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.196201. [CrossRef]

- S. Youngman, H.G. van Luenen, and R. H. Plasterk, “Rte-1, a retrotransposon-like element in Caenorhabditis elegans.,” FEBS Lett., vol. 380, no. 1–2, pp. 1–7, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(95)01525-6. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Malik and T. H. Eickbush, “NeSL-1, an Ancient Lineage of Site-Specific Non-LTR Retrotransposons From Caenorhabditis elegans,” Genetics, vol. 154, no. 1, pp. 193–203, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/154.1.193. [CrossRef]

- S. E. J. Fischer and G. Ruvkun, “Caenorhabditis elegans ADAR editing and the ERI-6/7/MOV10 RNAi pathway silence endogenous viral elements and LTR retrotransposons,” Proc National Acad Sci, vol. 117, no. 11, pp. 5987–5996, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919028117. [CrossRef]

- B. Sun, H. Kim, C.C. Mello, and J. R. Priess, “The CERV protein of Cer1, a C. elegans LTR retrotransposon, is required for nuclear export of viral genomic RNA and can form giant nuclear rods,” PLOS Genet., vol. 19, no. 6, p. e1010804, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1010804. [CrossRef]

- F. Palopoli et al., “Molecular basis of the copulatory plug polymorphism in Caenorhabditis elegans,” Nature, vol. 454, no. 7207, pp. 1019–1022, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07171. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Palopoli et al., “Molecular basis of the copulatory plug polymorphism in Caenorhabditis elegans,” Nature, vol. 454, no. 7207, pp. 1019–1022, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07171. [CrossRef]

- S. Dennis, U. Sheth, J.L. Feldman, K.A. English, and J. R. Priess, “C. elegans Germ Cells Show Temperature and Age-Dependent Expression of Cer1, a Gypsy/Ty3-Related Retrotransposon,” PLoS pathogens, vol. 8, no. 3, p. e1002591, Mar. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002591.t004. [CrossRef]

- H. G. A. M. van Luenen, S.D. Colloms, and R. H. A. Plasterk, “The mechanism of transposition of Tc3 in C. elegans,” Cell, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 293–301, 1994. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(94)90198-8. [CrossRef]

- C. Vos, I.D. Baere, and R. H. Plasterk, “Transposase is the only nematode protein required for in vitro transposition of Tc1.,” Genes Dev., vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 755–761, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.10.6.755. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Schukkink and R. H. Plasterk, “TcA, the putative transposase of the C. elegans Tc1 transposon, has an N-terminal DNA binding domain.,” Nucleic acids Res., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 895–900, 1990. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/18.4.895. [CrossRef]

- C. Vos and R. H. Plasterk, “Tc1 transposase of Caenorhabditis elegans is an endonuclease with a bipartite DNA binding domain.,” EMBO J., vol. 13, no. 24, pp. 6125–6132, 1994. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06959.x. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Vos, H.G. van Luenen, and R. H. Plasterk, “Characterization of the Caenorhabditis elegans Tc1 transposase in vivo and in vitro.,” Genes Dev., vol. 7, no. 7a, pp. 1244–1253, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.7.7a.1244. [CrossRef]

- S. E. J. Fischer, E. Wienholds, and R. H. A. Plasterk, “Continuous Exchange of Sequence Information Between Dispersed Tc1 Transposons in the Caenorhabditis elegans Genome,” Genetics, vol. 164, no. 1, pp. 127–134, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/164.1.127. [CrossRef]

- S. E. J. Fischer, E. Wienholds, and R. H. A. Plasterk, “Continuous exchange of sequence information between dispersed Tc1 transposons in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome.,” Genetics, vol. 164, no. 1, p. 127 134, May 2003. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/164.1.127. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Plasterk, “The origin of footprints of the Tc1 transposon of Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Embo J, vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 1919–1925, 1991. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07718.x. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Zwaal, A. Broeks, J. van Meurs, J.T. Groenen, and R. H. Plasterk, “Target-selected gene inactivation in Caenorhabditis elegans by using a frozen transposon insertion mutant bank.,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 90, no. 16, pp. 7431–7435, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.90.16.7431. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Ketting, S.E. Fischer, and R. H. Plasterk, “Target choice determinants of the Tc1 transposon of Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Nucleic acids research, vol. 25, no. 20, pp. 4041–4047, Oct. 1997. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.20.4041. [CrossRef]

- H. G. van Luenen and R. H. Plasterk, “Target site choice of the related transposable elements Tc1 and Tc3 of Caenorhabditis elegans.,” Nucleic acids research, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 262–269, Feb. 1994. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.3.262. [CrossRef]

- T. Daigle, T.C. Deiss, R.H. Melde, U. Bergthorsson, and V. Katju, “Bergerac strains of Caenorhabditis elegans revisited: expansion of Tc1 elements imposes a significant genomic and fitness cost,” G3, vol. 12, no. 11, p. jkac214, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkac214. [CrossRef]

- Duret, G. Marais, and C. Biémont, “Transposons but Not Retrotransposons Are Located Preferentially in Regions of High Recombination Rate in Caenorhabditis elegans,” Genetics, vol. 156, no. 4, pp. 1661–1669, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/156.4.1661. [CrossRef]

- P. Das et al., “Piwi and piRNAs act upstream of an endogenous siRNA pathway to suppress Tc3 transposon mobility in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline.,” Mol Cell, vol. 31, no. 1, p. 79 90, Jul. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.003. [CrossRef]

- F. R. Ketting and L. Cochella, “Concepts and functions of small RNA pathways in C. elegans,” Curr Top Dev Biol, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ctdb.2020.08.002. [CrossRef]

- E.-Z. Shen et al., “Identification of piRNA Binding Sites Reveals the Argonaute Regulatory Landscape of the C. elegans Germline.,” Cell, vol. 172, no. 5, Feb. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.002. [CrossRef]

- J. McEnany, Y. Meir, and N. S. Wingreen, “piRNAs of Caenorhabditis elegans broadly silence nonself sequences through functionally random targeting,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 1416–1429, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab1290. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Phillips, T.A. Montgomery, P.C. Breen, and G. Ruvkun, “MUT-16 promotes formation of perinuclear Mutator foci required for RNA silencing in the C. elegans germline.,” Gene Dev, vol. 26, no. 13, Jun. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.193904.112. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Ketting, T.H.A. Haverkamp, H.G.A.M. van Luenen, and R. H. A. Plasterk, “mut-7 of C. elegans, Required for Transposon Silencing and RNA Interference, Is a Homolog of Werner Syndrome Helicase and RNaseD,” Cell, vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 133–141, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81645-1. [CrossRef]

- L. Vastenhouw et al., “A Genome-Wide Screen Identifies 27 Genes Involved in Transposon Silencing in C. elegans,” Curr. Biol., vol. 13, no. 15, pp. 1311–1316, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00539-6. [CrossRef]

- Shukla et al., “poly(UG)-tailed RNAs in genome protection and epigenetic inheritance,” Nature, vol. 582, no. 7811, pp. 283–288, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2323-8. [CrossRef]

- J. Pak and A. Fire, “Distinct populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans.,” Science, vol. 315, no. 5809, p. 241 244, Jan. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132839. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Buckley et al., “A nuclear Argonaute promotes multigenerational epigenetic inheritance and germline immortality,” Nature, vol. 489, no. 7416, pp. 1–5, Jul. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11352. [CrossRef]

- S. Guang, A.F. Bochner, K.B. Burkhart, N. Burton, D.M. Pavelec, and S. Kennedy, “Small regulatory RNAs inhibit RNA polymerase II during the elongation phase of transcription.,” Nature, vol. 465, no. 7301, pp. 1097–1101, Jun. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09095. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Ding, H.J. Ochoa, T. Ishidate, M. Shirayama, and C. C. Mello, “The nuclear Argonaute HRDE-1 directs target gene re-localization and shuttles to nuage to promote small RNA-mediated inherited silencing,” Cell Rep., vol. 42, no. 5, p. 112408, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112408. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Fields and S. Kennedy, “Chromatin Compaction by Small RNAs and the Nuclear RNAi Machinery in C. elegans,” Sci Rep-uk, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 9030, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45052-y. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Garrigues, S. Sidoli, B.A. Garcia, and S. Strome, “Defining heterochromatin in C. elegans through genome-wide analysis of the heterochromatin protein 1 homolog HPL-2,” Genome Res., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 76–88, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.180489.114. [CrossRef]

- Ashe et al., “piRNAs Can Trigger a Multigenerational Epigenetic Memory in the Germline of C. elegans,” Cell, vol. 150, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Jun. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.018. [CrossRef]

- Quarato, M. Singh, L. Bourdon, and G. Cecere, “Inheritance and maintenance of small RNA-mediated epigenetic effects,” Bioessays, p. 2100284, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202100284. [CrossRef]

- G. Cecere, “Small RNAs in epigenetic inheritance: from mechanisms to trait transmission,” Febs Lett, vol. 595, no. 24, pp. 2953–2977, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.14210. [CrossRef]

- S. E. J. Fischer et al., “The ERI-6/7 Helicase Acts at the First Stage of an siRNA Amplification Pathway That Targets Recent Gene Duplications,” Plos Genet, vol. 7, no. 11, p. e1002369, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002369. [CrossRef]

- Newman, F. Ji, S.E.J. Fischer, A. Anselmo, R.I. Sadreyev, and G. Ruvkun, “The surveillance of pre-mRNA splicing is an early step in C. elegans RNAi of endogenous genes,” Gene Dev, vol. 32, no. 9–10, pp. 670–681, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.311514.118. [CrossRef]

- T. Sijen and R. H. A. Plasterk, “Transposon silencing in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line by natural RNAi.,” Nature, vol. 426, no. 6964, pp. 310–314, Nov. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02107. [CrossRef]

- Y. V. Makeyeva, M. Shirayama, and C. C. Mello, “Cues from mRNA splicing prevent default Argonaute silencing in C. elegans,” Dev. Cell, vol. 56, no. 18, pp. 2636-2648.e4, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2021.08.022. [CrossRef]

- Akay et al., “The Helicase Aquarius/EMB-4 Is Required to Overcome Intronic Barriers to Allow Nuclear RNAi Pathways to Heritably Silence Transcription.,” Dev Cell, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 241-255.e6, Aug. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2017.07.002. [CrossRef]

- Carr and P. Anderson, “Imprecise Excision of the Caenorhabditis elegans Transposon Tel Creates Functional 5′ Splice Sites,” Mol. Cell. Biol., vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 3426–3433, 1994. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.14.5.3426-3433.1994. [CrossRef]

- M. Rushforth and P. Anderson, “Splicing removes the Caenorhabditis elegans transposon Tc1 from most mutant pre-mRNAs.,” Mol Cell Biol, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 422–429, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.16.1.422. [CrossRef]

- Kurhanewicz, D. Dinwiddie, Z.D. Bush, and D. E. Libuda, “Elevated Temperatures Cause Transposon-Associated DNA Damage in C. elegans Spermatocytes,” Curr. Biol., vol. 30, no. 24, pp. 5007-5017.e4, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.050. [CrossRef]

- K. Rogers and C. M. Phillips, “RNAi pathways repress reprogramming of C. elegans germ cells during heat stress,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 48, no. 8, pp. 4256–4273, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa174. [CrossRef]

- S. Moore et al., “The role of the Cer1 transposon in horizontal transfer of transgenerational memory,” Cell, vol. 184, no. 18, pp. 4697-4712.e18, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.022. [CrossRef]

- F. N. Carelli, C. Cerrato, Y. Dong, A. Appert, A. Dernburg, and J. Ahringer, “Widespread transposon co-option in the Caenorhabditis germline regulatory network,” Sci. Adv., vol. 8, no. 50, p. eabo4082, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abo4082. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Garrigues, B.V. Tsu, M.D. Daugherty, and A. E. Pasquinelli, “Diversification of the Caenorhabditis heat shock response by Helitron transposable elements,” eLife, vol. 8, p. e51139, 2019. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.51139. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).