1. Introduction

Sepsis is a global health problem associated with a high mortality rate especially in critical care units [

1]. Recently, sepsis has been defined as” life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” [

2]. Annually the United States reported at least 900.000 people with sepsis and a 25-30% hospital mortality rate related to sepsis [

3]. According to a recent Chinese study in 2022, sepsis was prevalent in 25.5% of ICU patients [

4]. Sepsis is a common cause of admission and long hospitalization in Asian healthcare settings. For example, the prevalence of sepsis in the ICU among Asian healthcare settings is 22.4% [

5], and in Jordan was 21% [

6]. According to a recent study in 2017, about 49 million cases of sepsis and 11 million deaths were related to sepsis, worldwide [

7].

Sepsis has serious consequences such as Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy [

8], acute renal failure [

9], encephalopathy [

10], and post-sepsis syndrome [

11]. According to a French study in 2020, the cost of treating sepsis in the hospital is about 11.400 euros [

12]. Therefore, sepsis is a time-sensitive emergency problem that needs rapid identification and management to reduce its morbidity and mortality rates [

13].

Critical care nurses play a key role in the identification and management of sepsis [

6]. The presence of evidence-based guidelines facilitates the nurses’ early detection of sepsis especially in an emergency department and assists providing appropriate management of patients with sepsis. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) developed sepsis 1-hour, 3-hour, and 6-hour bundles focusing on timely identification and rapid management [

14]. These bundles are considered the cornerstone of the management of sepsis [

15]. Sepsis six bundles include obtaining blood culture, assessing lactate level, and administering broad-spectrum antibiotics, oxygen, intravenous fluid, and vasopressor [

16]. Many recent studies have shown that compliance with sepsis evidence-based guidelines led to a decreased mortality rate, improved patient outcomes, and reduced readmission [

14,

17,

18] and decreased time to initial antibiotics [

19].

Recently a randomized clinical trial study conducted in two medical-surgical intensive care units in California revealed that the use of a machine sepsis prediction system led to a decrease in the length of stay from 13 days to 10 days and a decrease in the mortality rate by 12.4% [

20]. Another recent study has shown that implementing sepsis guidelines led to a reduced need for ICU admission [

21]. Similarly, the nurse’s compliance with sepsis six guidelines leads to decrease in sepsis-related complication and mortality rates and improved clinical outcomes [

22]. However, low adherence and compliance with applying sepsis six guidelines are still unresolved issues impeding sepsis management due to several barriers [

23]. Previous researchers have identified several barriers and facilitators to the implementation of sepsis six guidelines [

19,

24]. Identifying the barriers and facilitators is very important to facilitate and improve the nurse's compliance and adherence to sepsis six guidelines [

19]. However, up to date, no study has examined the predictors of these perceived barriers and facilitators among critical care nurses. Accordingly, the study aims to examine the predictors of perceived barriers and facilitators of applying evidence-based sepsis six guidelines among critical care nurses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Sample, and Settings

Across-sectional descriptive study was conducted on a convenience sample of 180 nurses who worked in adult critical care settings (ICU, CCU, ED, burning unit, Dialysis unit) at a university hospital, in Jordan for at least one year. The sample size determined by G* power analysis, considering the following parameters: a significant level of 0.05, a statistical power level of 0.8, and a medium effect size was enough in this study.

2.2. Study Instrument

The cross-sectional descriptive study was designed by using an online survey derived from previous research [

24,

25] and consisted of three parts. The first part includes five questions about demographic data such as age, gender, and marital status. The second part includes 54 questions related to perceived barriers and facilitators of applying sepsis guidelines. Each of the 54questions consists of two opposing statements rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) very unimportant to (5) very important [

24]. The third part includes 7close-ended questions; two are related to the identification and management of sepsis guidelines and five are about resources, education, and skills. The face and content validity were done by four nursing experts in sepsis who reviewed the questionnaire. Then the questionnaire was piloted on 10 nurses, who were excluded from the primary study, to ensure the clarity of the questionnaire items.

2.3. Data Collection

The researcher met with the nurse manager in the hospital to discuss the eligibility criteria for participation and prepare a list of eligible participants' nurses and their emails. All eligible nurses have been invited to take part in the study by sending an invitation E-mail containing the aims of the study, brief explanations of the study, rights and responsibilities of the participants. A reminder email two weeks after the initial communication was used with the participants to improve the response rate. All nurses who replied to our invitation received another E-mail containing the consent form and the study survey. Data collection was carried out in January 2024.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval (2024/2023/3/17) for the study was received from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Balqa Applied University and the study setting. Written informed consent was obtained from the participating nurses. The participants were told that they could withdraw from the study at any time. The privacy and confidentiality of collected data were assured throughout the study.

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

The mean and standard deviation were used to describe continuous measured variables. The frequency and percentages were used to describe categorically measured variables. The Kolmogrove-Smirnove (KS) statistical test of normality and the histogram were used to assess the statistical Normality of metric variables assumption. The Bivariate Pearson's test of correlation was used to assess the correlations between metric-measured variables. The Multivariable Linear Regression Analysis was applied to assess the statistical significance of possible predictors for nurses' perceived barriers and facilitators of applying Sepsis Six bundles. The association between the predictor-independent variables with the analyzed outcomes in the multivariable Linear Regression analysis was expressed as an unstandardized Beta coefficient with its associated 95% confidence intervals. The latest version of the SPSS IBM statistical computing test was used for the statistical analysis and the alpha significance level was considered at 0.050 level.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics

One hundred and eighty critical care nurses enrolled in the study and completed and returned the study survey.

Table 1 displays the nurse's sociodemographic characteristics and working and professional factors. The findings showed that 52.8% of the sample were male, and 23.9% were never married. A round of 34% of nurses had experience between 1-4 years and 24.4% held a master's degree in nursing. 21.1% of the nurses worked in CCU, 22.2% in ER, 35.6% in surgical-medical ICU, and 21.1% in other units like (dialysis and burn units).

3.2. Perspectives on Reasons for Delayed Sepsis Identifications

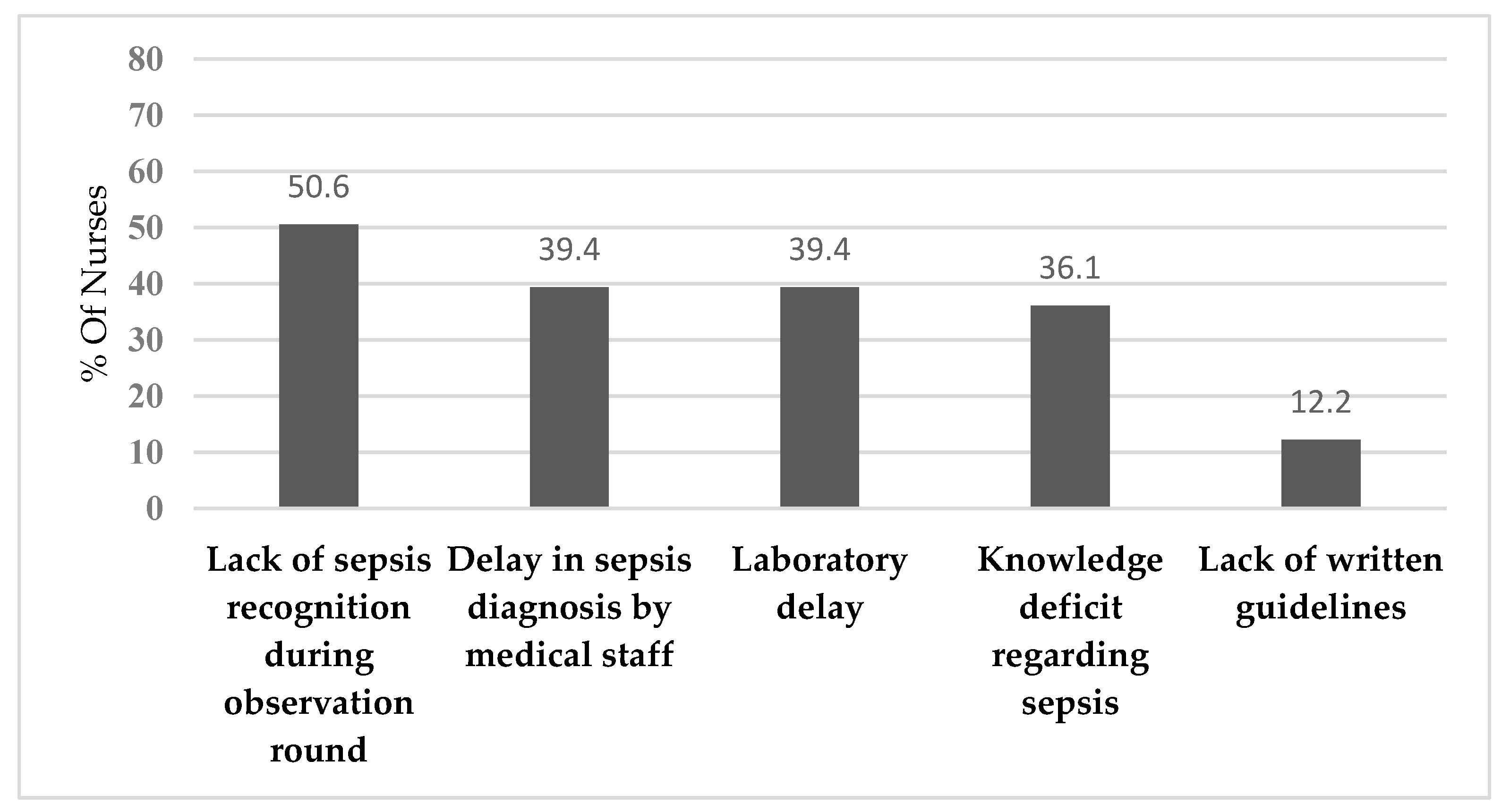

The Nurse's experiences with sepsis management were also measured via several questions that measured their opinions about delays in sepsis identification and management. The nurses were asked to indicate the most common cause of delay in the identification of septic patients at work. The analysis findings showed that most of the nurses 50.6% believed lack of sepsis recognition during observation rounds may delay sepsis identification.

Figure 1 shows the remaining prevalence of reasons for delayed sepsis identification according to nurses’ perspectives.

3.3. Perspectives on Reasons for Delayed Sepsis Treatment

Furthermore, the findings showed that the majority of nurses (45.6%) believed that laboratory delays may contribute to delayed sepsis treatment.

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of remaining reasons for delayed sepsis treatment according to nurses’ perspectives.

3.4. Description of Nurses’ Perceived Barriers and Facilitators

The analysis findings also showed that 61.1% of the Nurses had previous training on sepsis identification and management. Another 50.6% of them advised that the courses on sepsis management they've undertaken were indeed satisfactory. However, the analysis findings showed that 67.2% of the nurses were indeed aware that serum lactate test results can be used to influence/guide septic patients' management. Also, most of the nurses 77.8% had agreed that sepsis treatments were available at their point-of-care areas (like IV fluids, Oxygen, and first-line antibiotics). Also, most of the nurses, 81.7%, had confirmed the availability of sepsis investigations at their point-of-care areas (like blood lactate tests, blood culture, and urinary catheters and containers). The detailed descriptive analysis is outlined in

Table 2.

3.5. Predictors of Nurses’ Perceived Facilitators of Sepsis Management

The Multivariable Linear Regression Analysis (MLRA) was used to examine the predictors of nurse's perceived facilitators of sepsis six performance bundle (SSPB) implementation at the workplace to understand what explains why the nurses perceived less or more importance to the Sepsis Six Performances at the workplace. The yielded analysis findings,

Table 3, showed that the nurses' sex, marital state, educational level, and experience years were not associated significantly with their overall mean perceived SSPB importance score, p-value>0.050. However, nurses who believed that medical staff delays diagnosis of the sepsis patients had significantly higher overall mean perceived SSPB importance scores compared to nurses who disagreed, beta coefficient=0.312, p-value=0.006. Also, nurses who perceived a lack of written guidelines at the workplace may delay sepsis diagnoses had perceived significantly higher overall mean perceived SSPB importance score compared to those who did not agree, beta coefficient=0.498, p-value=0.002. Not only that but also the nurses who believed that sepsis investigations and lab tests were available at the point of care had perceived significantly higher overall mean perceived SSPB importance scores compared to nurses who reported the absence of the investigations, beta coefficient=0.321, p-value=0.016. Moreover, the analysis model showed that the nurses who perceived knowledge deficit as a cause for sepsis diagnosis delay had perceived the SSPB as significantly more important compared to those who did not perceive, beta coefficient=0.447, p-value<0.001.

3.6. Predictors of Nurses’ Perceived Barriers to Sepsis Management

Also, to arrive at better insight on what may explain why the nurses had perceived less or more barriers to implementing the Sepsis Six Performance bundle at their workplace the multivariable linear regression analysis was applied as well to regress their overall mean perceived SSPB implementing barriers score against their sociodemographic characteristics and work and professional related factors and perceptions. The yielded multivariable analysis findings, shown in

Table 4, suggested that the nurses' sex, marital state, working units, and experience years as well as their educational level did not correlate significantly with their overall mean perceived SSPB implementing barriers score, p-value>0.050. However, the analysis findings showed that the nurse's overall mean perceived SSPB importance score had been associated positively and significantly with their overall mean perceived SSPB implementing barriers score. Interestingly, the analysis findings showed that the nurses who agreed that medical staff may delay the sepsis diagnoses had perceived significantly lower overall mean perceived SSPB implementing barriers score compared to those who disagreed that medical staff may cause sepsis diagnosis delay, beta coefficient=-0.459, p-value<0.001. Also, the nurses who had perceived a lack of sepsis recognition during observation rounds may delay sepsis had perceived significantly lower overall mean perceived SSPB implementing barriers score compared to Nurses who did not experience such lack of sepsis recognition, beta coefficient=-0.482, p-value<0.001. Not only that but also the nurses who perceived lack of written guidelines may hinder sepsis diagnoses had perceived significantly lower overall mean perceived SSPB implementing barriers score compared to those who did not agree, beta coefficient= -0.508, p-value=0.004.

4. Discussion

This is the first study in Jordan to examine the predictors of perceived barriers and facilitators of applying sepsis six guidelines among critical care nurses. Our study found that nurses' socio-demographic characteristics did not influence their perceived barriers and facilitators of applying sepsis guidelines. Our study revealed that lack of sepsis recognition during observational rounds is considered the greatest cause of delayed identification of sepsis. Similarly, Breen’s study was conducted on a convenience sample from nurses and junior doctors who work in an emergency department [

25], as well as this study found that laboratory delay, is considered the biggest cause of delayed management and treatment of sepsis. Consistent with Breen’ study that found nursing delay, knowledge deficit and laboratory delay are the major causes of delayed management of sepsis [

25].

Our finding revealed that the importance of the presence written tool or protocol can guide sepsis assessment and management. Consistent with previous studies have reported applying of sepsis protocol/guidelines was highly effective in early identification and management of sepsis as well as improving nurses' compliance of applying sepsis guidelines [

26]. Also, regular use of sepsis guidelines makes it easier to remember the sepsis involved and improves nurses' performance [

14].

Several studies revealed that lack of knowledge and unfamiliarity with sepsis six guidelines can lead to delayed identification of patients with sepsis [

19,

24,

25]. Also, the current study revealed a lack of nurses' knowledge regarding sepsis considered one of the main barriers to applying sepsis guidelines. Previous studies showed that Jordanian nurses have poor knowledge regarding sepsis identification and management may be attributed to several causes including the nursing schools in Jordan do not focus on sepsis identification and management. Moreover, inadequate ongoing education programs for nursing staff on sepsis identification and management could be another factor [

6]. Also, the finding of the current study that nursing delay is considered one of the main causes of delaying sepsis management and treatment was consistent with the finding of Burney [

27] that the shortage of nursing is a main barrier to the management of sepsis.

The current study revealed that the nurses are aware of the lactate level influence and guide sepsis identification and management. This is inconsistent with a previous Canadian study that revealed that emergency nurses had a low level of knowledge and awareness about the effect of lactate level on early identification and management of sepsis [

28]. Maybe because ongoing education program can improve nurses’ awareness about the effect of the lactate level on early identification and management of sepsis. Our study revealed that the sepsis investigation and treatment are available at the point of care. This result suggest that the nursing and medical team can identify septic patient and initiate the prompt and urgent management. These findings consistent with the previous studies shown the lack of necessary equipment can delay sepsis identification and management then increase the morbidity and mortality rate related to sepsis [

24,

27]. This study found the major areas of sepsis education program that nurses believe can be improved including: identify septic patient and identify sepsis pathway consistent with previous studies found the importance of educate the nurses about the early signs and symptoms of sepsis to facilitate early identification of septic patient [

6,

29]. Also, the nurses must be improved the practical skills including: (cannulation, blood culture, administer antibiotic and other skills). This study emphasized the importance of conducting ongoing education training for nurses especially in identifying sepsis and applying the sepsis pathway. Consistent with the previous study conducted on nurses and junior doctors working in an emergency department, the doctors need further education in an applied sepsis pathway but nurses need further assessment in practical issues [

25]. Another quasi-experimental study conducted on 40 nurses in neuro-surgical wards and ICU found that education sessions can improve nurses’ knowledge about sepsis guidelines and the quality of care for septic patients [

30]. Another prospective study aimed to assess adherence and compliance of sepsis bundles after the education program and the impact of hospital stay revealed adherence and compliance improved and reduced children's hospital stays related to sepsis [

31]. Also, the education program can improve nurse’s competent regarding sepsis identification and management [

32]

Limitation of the Study

This study was conducted only in one geographic area so it may limit the generalizability of the data. Using–a non-probability convenience sample may cause selection bias and threaten internal validity.

5. Conclusions

Early identification and management of sepsis is a critical issue to decrease the morbidity and mortality rate related to sepsis. presence of sepsis guidelines can facilitate and improve the early identification and management of sepsis. This study found the various barriers face the critical care nurses of applying sepsis guidelines lack of sepsis recognition during observational rounds, delay in sepsis diagnosis by medical staff and laboratory delay. For the facilitators, ongoing education program related to sepsis identification, and apply sepsis pathway.

Clinical Implication and Recommendation

The finding of this study could help the hospital managers in developing ongoing education sessions about sepsis management for both physicians and nurses Also, our finding could be used in developing written specific and quick tools/checklists to facilitate early assessment and management of sepsis may improve nurses' compliance and adherence to sepsis guidelines. Further mixed method and interventional studies to assess the barriers and facilitators of applying sepsis guidelines in critical care settings are needed. In future studies, a large sample size, including multidisciplinary participants and more than one region is recommended to improve the generalizability of the finding and the reliability and validity of data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.H. and M.R.; methodology, D.B.H. and M.T; software, D.B.H.; validation, D.B.H., M.R.,M.T and R.A.A.; formal analysis, D.B.H.; investigation, D.B.H.,M.R.,M.T. and R.A.A.; resources, D.B.H. and M.R.; data curation, D.B.H.,M.R. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.H.; writing—review and editing, D.B.H.,M.R.,M.T. and R.A.A.; visualization, D.B.H.,M.R.,M.T. and R.A.A.; supervision, D.B.H.; project administration, D.B.H.; funding acquisition, D.B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Balqa Applied University (2024/2023/3/17). Moreover, written informed consent was obtained from the participating nurses.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the nurses who participated in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon a justified request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Gauer, R.; Forbes, D.; Boyer, N. Sepsis: diagnosis and management. AFP. 2020, 101, 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C. S.; Seymour, C. W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G. R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischmann, C.; Scherag, A.; Adhikari, N. K.; Hartog, C. S.; Tsaganos, T.; Schlattmann, P.; Angus, D. C.Reinhart, K. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. 2016, 193, 259–272. [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Xie, Y.Li, J. Prevalence of sepsis among adults in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health. 2022, 10, 977094. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Ling, L.; Qin, H.; Arabi, Y. M.; Myatra, S. N.; Egi, M.; Kim, J. H.; Mat Nor, M. B.; Son, D. N.Fang, W.-F. Epidemiology, management, and outcomes of sepsis in ICUs among countries of differing national wealth across Asia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. 2022, 206, 1107–1116. [CrossRef]

- Rababa, M.; Bani-Hamad, D.; Hayajneh, A. A.Al Mugheed, K. Nurses' knowledge, attitudes, practice, and decision-making skills related to sepsis assessment and management. Electron J Gen Med. 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann-Struzek, C.; Mellhammar, L.; Rose, N.; Cassini, A.; Rudd, K.; Schlattmann, P.; Allegranzi, B.Reinhart, K. Incidence and mortality of hospital-and ICU-treated sepsis: results from an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1552–1562. [CrossRef]

- Iba, T.; Connors, J. M.; Nagaoka, I.Levy, J. H. Recent advances in the research and management of sepsis associated DIC. Int. J. Hematol. 2021, 113, 24–33. [CrossRef]

- Skube, S. J.; Katz, S. A.; Chipman, J. G.Tignanelli, C. J. Acute kidney injury and sepsis. Surg. Infect. 2018, 19, 216–224. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shi, X.; Diao, M.; Jin, G.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, W.Xi, S. A retrospective study of sepsis-associated encephalopathy: epidemiology, clinical features and adverse outcomes. BMC Emerg. Med. 2020, 20, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Mostel, Z.; Perl, A.; Marck, M.; Mehdi, S. F.; Lowell, B.; Bathija, S.; Santosh, R.; Pavlov, V. A.; Chavan, S. S.Roth, J. Post-sepsis syndrome–an evolving entity that afflicts survivors of sepsis. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, C.; Bouadma, L.; Ruckly, S.; Perozziello, A.; Van-Gysel, D.; Mageau, A.; Mourvillier, B.; de Montmollin, E.; Bailly, S.Papin, G. Sepsis and septic shock in France: incidences, outcomes and costs of care. Ann. Intensive Care. 2020, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Harley, A.; Johnston, A.; Denny, K.; Keijzers, G.; Crilly, J.Massey, D. Emergency nurses’ knowledge and understanding of their role in recognising and responding to patients with sepsis: A qualitative study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2019, 43, 106–112. [CrossRef]

- Frank, H. E.; Evans, L.; Phillips, G.; Dellinger, R.; Goldstein, J.; Harmon, L.; Portelli, D.; Sarani, N.; Schorr, C.Terry, K. M. Assessment of implementation methods in sepsis: study protocol for a cluster-randomized hybrid type 2 trial. Trials. 2023, 24, 620. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, M. E.; Ferrer, R.; Martin, G. S.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Machado, F. R.; De Backer, D.; Coopersmith, C. M.; Deutschman, C. S.Levy, S. S. C. R. C. M. A. J. H. S. J. J. K. I. L. M. M. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: research priorities for the administration, epidemiology, scoring and identification of sepsis. ICMx. 2021, 9, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, S.E. Sepsis management in the emergency department. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2020, 55, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Y. M.; Alsaawi, A.; Al Zahrani, M.; Al Khathaami, A. M.; AlHazme, R. H.; Al Mutrafy, A.; Al Qarni, A.; Al Shouabi, A.; Al Qasim, E.Abdukahil, S. A. Electronic early notification of sepsis in hospitalized ward patients: a study protocol for a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021, 22, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Herran-Monge, R.; Muriel-Bombin, A.; Garcia-Garcia, M. M.; Merino-Garcia, P. A.; Martinez-Barrios, M.; Andaluz, D.; Ballesteros, J. C.; Domínguez-Berrot, A. M.; Moradillo-Gonzalez, S.Macias, S. Epidemiology and changes in mortality of sepsis after the implementation of surviving sepsis campaign guidelines. J. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 34, 740–750. [CrossRef]

- Reich, E. N.; Then, K. L.Rankin, J. A. Barriers to clinical practice guideline implementation for septic patients in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2018, 44, 552–562. [CrossRef]

- Shimabukuro, D. W.; Barton, C. W.; Feldman, M. D.; Mataraso, S. J.Das, R. Effect of a machine learning-based severe sepsis prediction algorithm on patient survival and hospital length of stay: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2017, 4, e000234. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, B.; Schlapbach, L.; Mason, D.; Wilks, K.; Seaton, R.; Lister, P.; Irwin, A.; Lane, P.; Redpath, L.; Gibbons, K. Impact of 1-hour and 3-hour sepsis time bundles on patient outcomes and antimicrobial use: A before and after cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, A.; Hine, P.Nsutebu, E. The recognition and management of sepsis and septic shock: a guide for non-intensivists. Postgrad. Med. J. 2017, 93, 626–634. [CrossRef]

- Mosavianpour, M.; Collett, J.; Sarmast, H.Kissoon, N. Barriers to the implementation of sepsis guideline in a Canadian pediatric tertiary care centre. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016, 6, 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; Hooper, G.; Lorencatto, F.; Storr, W.Spivey, M. Barriers and facilitators towards implementing the Sepsis Six care bundle (BLISS-1): a mixed methods investigation using the theoretical domains framework. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2017, 25, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Breen, S.-J.Rees, S. Barriers to implementing the Sepsis Six guidelines in an acute hospital setting. BJN. 2018, 27, 473–478. [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, M.; Onikoyi, O.; Rodrigopulle, D.; Syed, A.; Jones, S.; Mansfield, L.Krishna, M. G. Sepsis-review of screening for sepsis by nursing, nurse driven sepsis protocols and development of sepsis hospital policy/protocols. Nursing and Palliative Care. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Burney, M.; Underwood, J.; McEvoy, S.; Nelson, G.; Dzierba, A.; Kauari, V.Chong, D. Early detection and treatment of severe sepsis in the emergency department: identifying barriers to implementation of a protocol-based approach. J Emerg Nurs. 2012, 38, 512–517. [CrossRef]

- Storozuk, S. A.; MacLeod, M. L.; Freeman, S.Banner, D. A survey of sepsis knowledge among Canadian emergency department registered nurses. Australas. Emerg. Care. 2019, 22, 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J.; Henderson, S.; Thakore, S.; Donald, M.Wang, W. Seeking sepsis in the emergency department-identifying barriers to delivery of the sepsis 6. BMJ Qual. Improv. Rep. 2016, 5, u206760. w3983. [CrossRef]

- Nakiganda, C.; Atukwatse, J.; Turyasingura, J.Niyonzima, V. Improving Nurses’ Knowledge on Sepsis Identification and Management at Mulago National Referral Hospital: A Quasi Experimental Study. Nursing: Research and Reviews. 2022, 169-176. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sarmiento, J.; Carcillo, J. A.; Salinas, C. M.; Galvis, E. F.; López, P. A.Jagua-Gualdrón, A. Effect of a sepsis educational intervention on hospital stay. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018, 19, e321–e328. [CrossRef]

- Delaney, M. M.; Friedman, M. I.; Dolansky, M. A.Fitzpatrick, J. J. Impact of a sepsis educational program on nurse competence. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2015, 46, 179–186. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).