Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

07 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Indoor location and positioning: GPS technology has made outdoor positioning very successful and widely supported. However, due to signal attenuation caused by building materials, indoor positioning systems cannot rely on this technology for efficient measurements. At the same time, many indoor positioning systems have been developed based on a wide range of technologies, including WLAN, infrared, ultrasonic, and Bluetooth [5]. Indoor location and positioning is made possible through the use of techniques such as trilateration, triangulation and fingerprinting [6], that calculate distance using the strength level of a signal received by a user device. The signal is generated by multiple radio beacons placed indoors, while relative position is decided based on the accumulated distance from the beacons. Bluetooth radio beacons covering indoor spaces can provide a low-cost, low-power solution, while a smartphone can act as a receiver. The accuracy achieved in positioning and tracking is critical for OPTORER service, [7].

- Physical user state assessment: The physical effort exerted, or the physical state of a user at a particular moment, can be assessed using algorithms that have as input heart rate monitoring data and/or cadence/pace measurement, obtained from sensors embedded in smartphones and wearable devices. However, accuracy in estimation is really a challenge. In addition, estimating user experience from this data is a step forward in this type of evaluation as it attempts to capture real-time user sentiment regarding user satisfaction, [8].

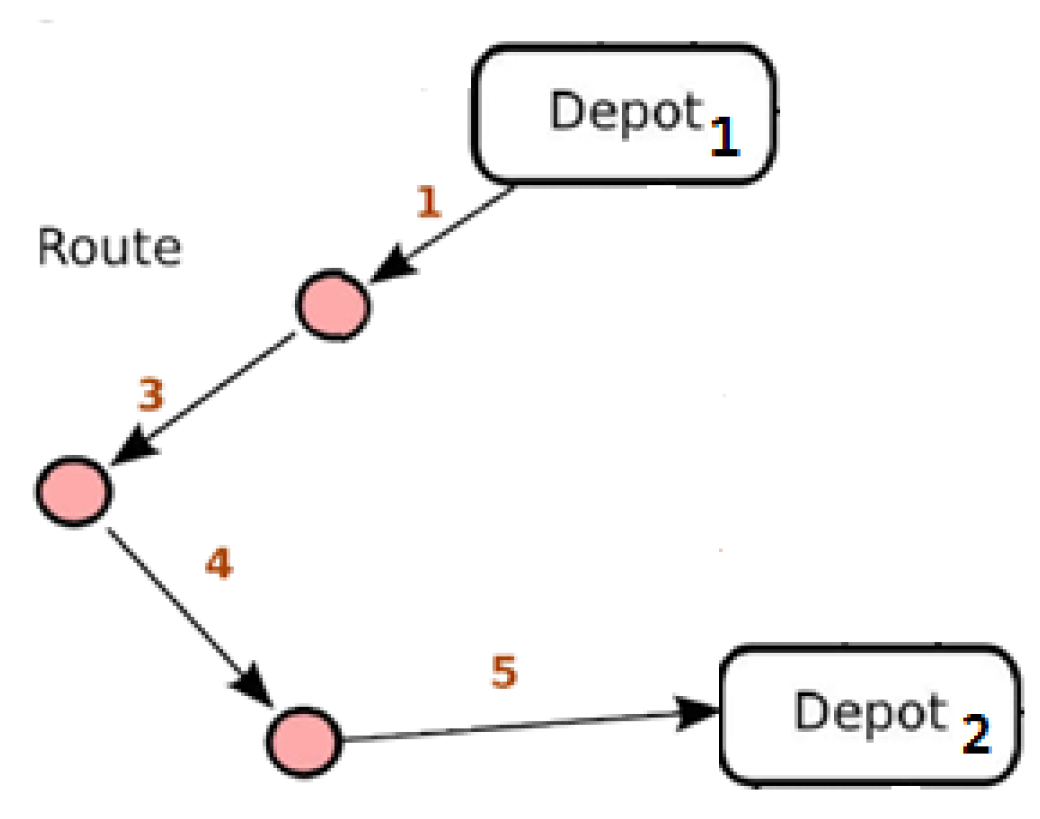

- Dynamic Multi-Criteria Routing Optimization: The exact solution (i.e., finding a globally optimal solution) of the routing optimization problem will make it impossible to provide near-real-time results, as the routing problem belongs to the class of optimization problems known as NP-Complete, which means that it is not possible to quickly find an optimal solution, as the complexity increases significantly as the destinations involved in routing increase, [9]. The need to develop efficient meta-heuristic algorithms to provide a near-optimal solution to the multi-criteria optimization problem, in near-real time, is a challenge that has been addressed in OPTORER application. Furthermore, due to the dynamic nature of a tour, the service is required to be able to partially solve the optimization problem when some of the variables change in order to provide updated results immediately, [9].

2. System Design

- ✓

- To offer a routing and tour planner service in outdoor/indoor places of touristic and cultural interest able to adjust to achieve specific purposes (personalized criteria and/or promoted purposes).

- ✓

- To expand the number of tours indoors requiring only a low-cost initial investment from the operators of places of interest using BLE beacons.

- ✓

- To assess the user experience and drive the dynamic adjustment of routing decisions along the tour.

- ✓

- To provide the current state with the ability to ensure in real time the safety and well-being of citizens by communicating notifications or alerts to be taken into account in the dynamic routing decision process.

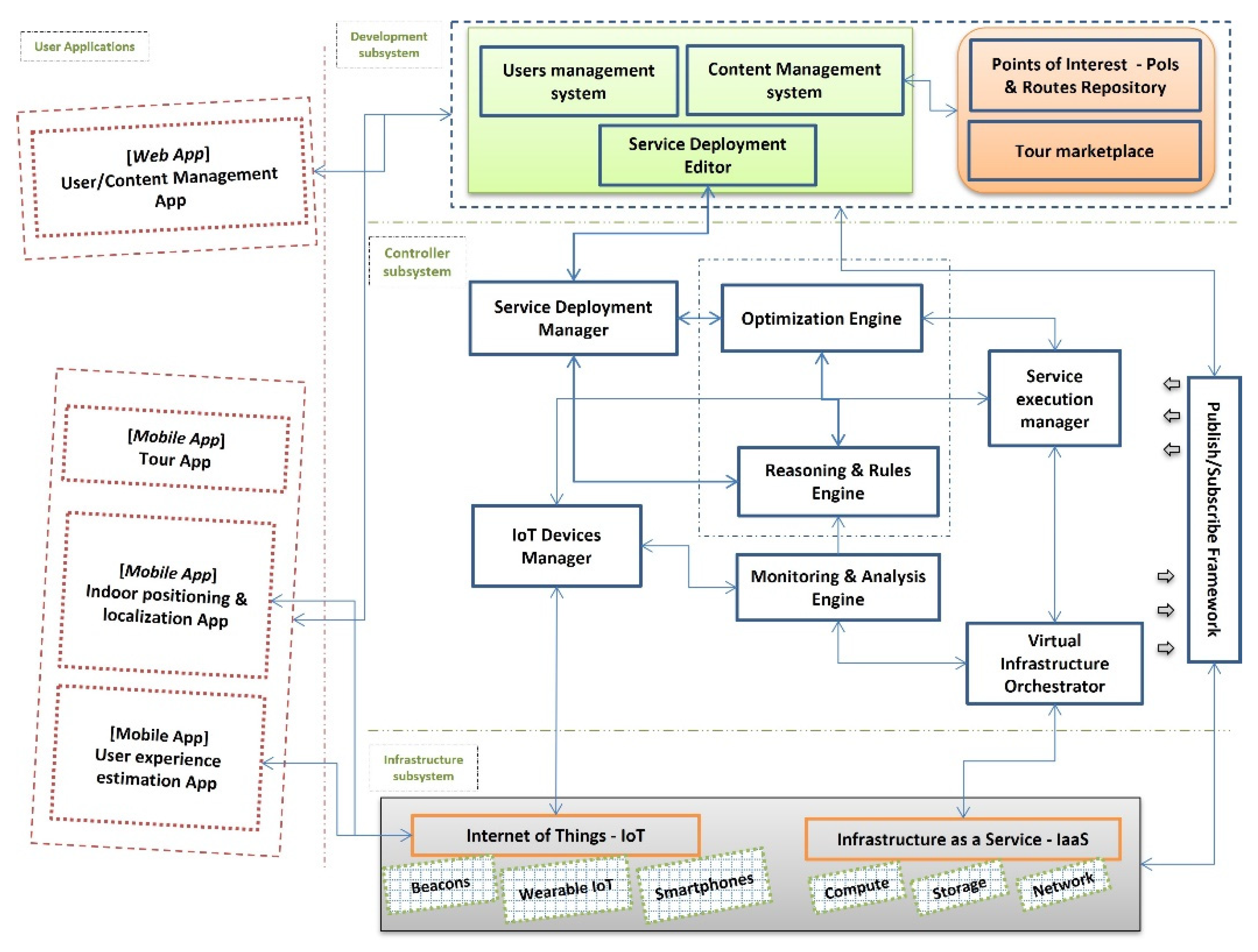

- User Applications subsystem

- Development subsystem

- Controller subsystem

- Infrastructure subsystem

2.1. Description of OPTORER’s sub-systems

2.2. Types of Users and Allowed actions

- -

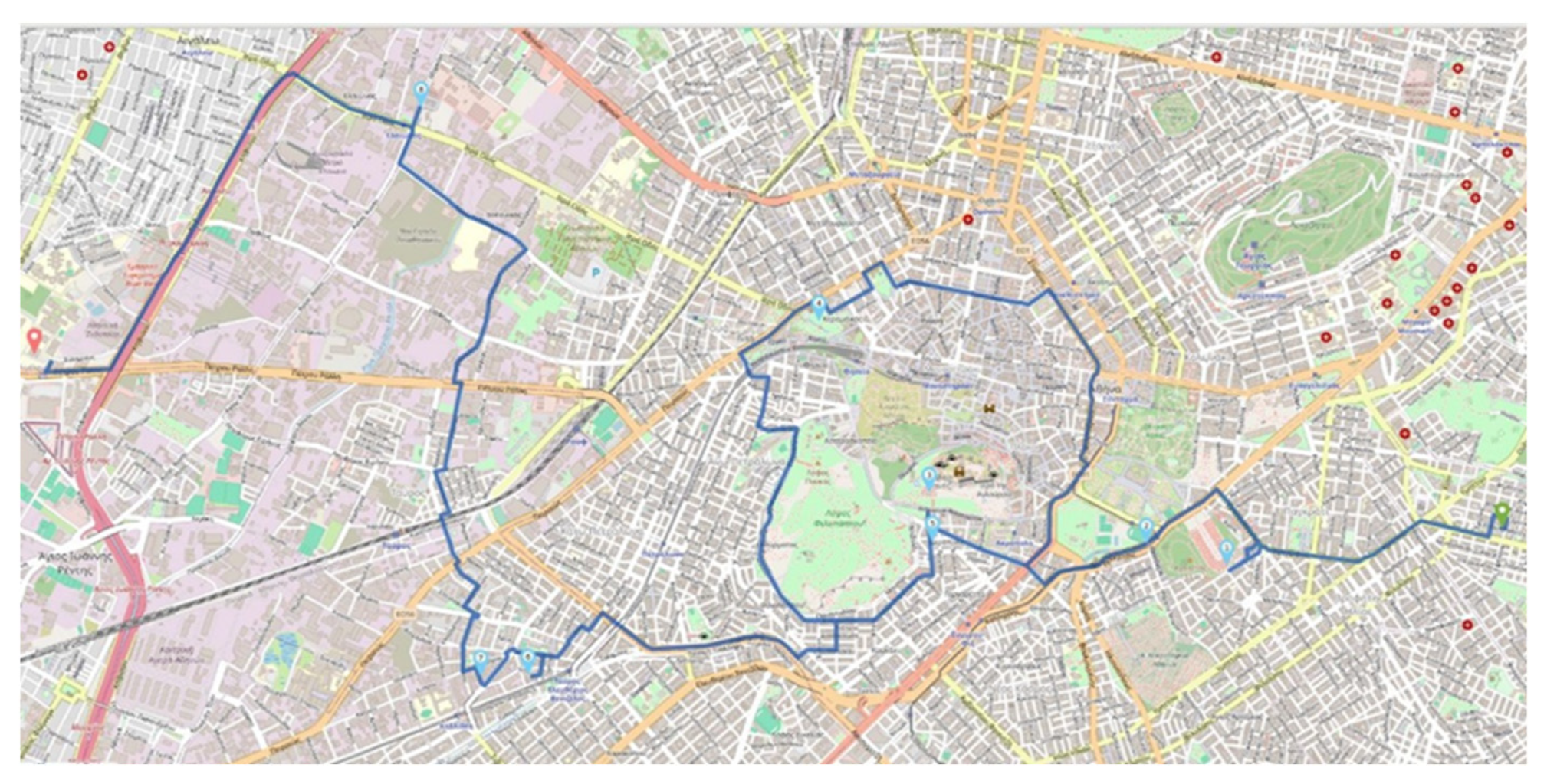

- End User: The end user of the service uses the Mobile Application to follow a selected tour (pre-planned or custom). Users of the Mobile Application are able to search among pre-planned tours filtered by the category of interest, the cost, or the available time. Additionally, the end users can create their own tour by setting the following details: the starting point, specific order for visiting the already registered PoIs, the endpoint and the preferred means of transportation. In this case, PoIs can be selected using a filter based on the category of interest. Also, the end users can use the mobile application to report an event at the point where they are, follow it by a short description of the event.

- -

-

Administrator: The Administrator can define technical parameters of the system, gain access to data recorded for security reasons (e.g., unsuccessful login attempts) and manage users (i.e., in terms of access role and status). There are also certain administrative functionalities that have specific roles assigned to them (i.e., administrator sub-roles). These roles are:

- o

- Partner’s Content Management: Core Functionality of this role is to review the content/services that partners intend to include in the system. Examination of the content offered (e.g., texts and photos) is essential in online platforms to avoid malicious content and also to avoid listing mistakes by partners.

- o

- Event Management: Core Functionality of this role is to review data related to events reported by end users or other sources (communication streams). Reviewing events before communicating them to end users is essential to avoid false alarms, which can cause unnecessary panic.

- -

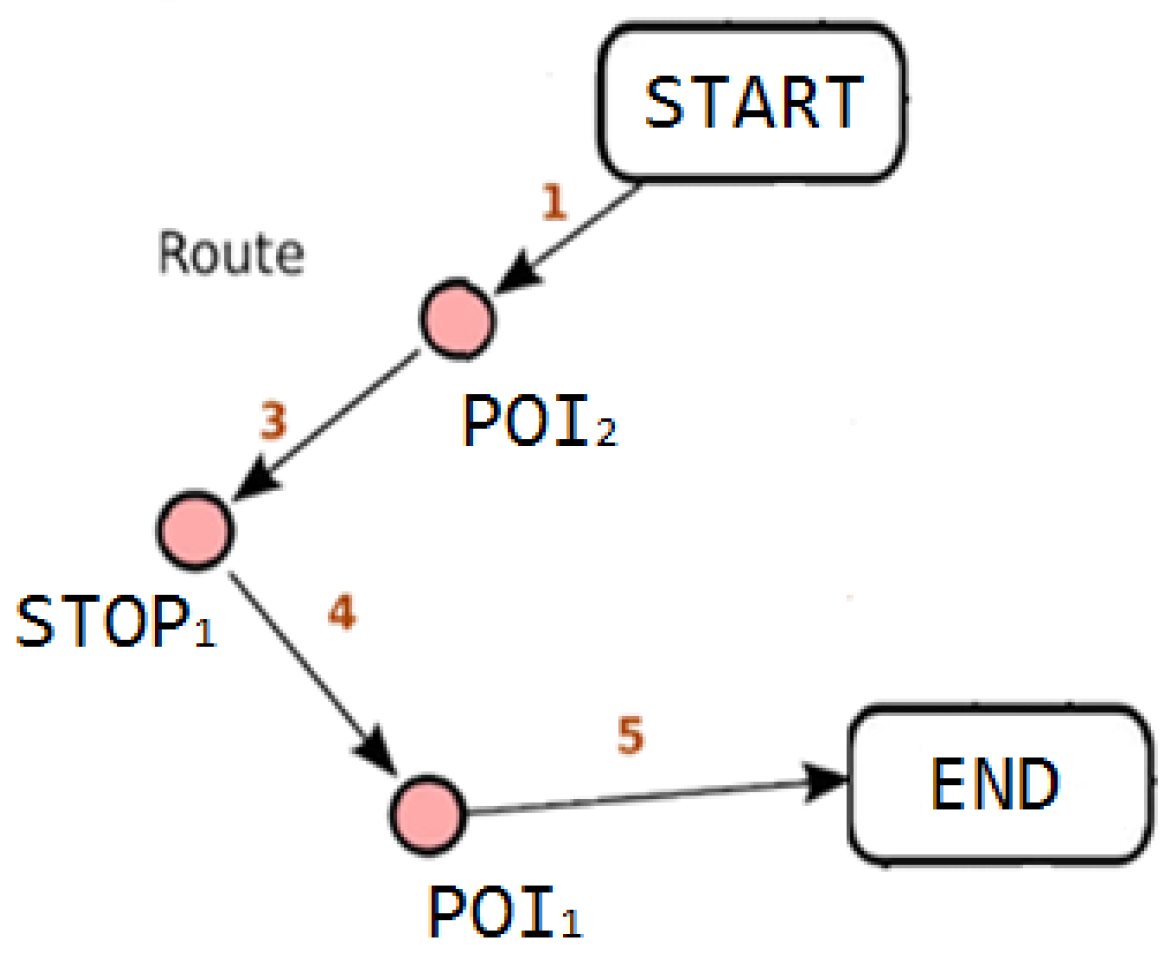

- Tour Creator: The Tour Creator creates and configures a tour, defining the sequence of visits to Areas of Interest as well as the sequence of visits to Points of Interest within the selected Areas. The tour can combine both indoor and outdoor locations. Additionally, the tour creator enters content related to the Areas and Points of Interest while setting tour scheduling and possible stops/visits to points related to external Partners Provided Services. This way, the Tour Creator can enhance the end user’s experience during the tour or can cover possible needs along the way.

- -

- Cartographer: The Cartographer creates maps of indoor spaces and defines the location of indoor PoIs. Also, the Cartographer utilizes the required radio beacon infrastructure as well as the topographical mapping of the area to define a tour inside the indoors area. Additionally, Cartographer can add more detailed descriptions to outdoors PoI that can be included in tours combining the added indoor location.

- -

- External Service Provider: The role of the External Service Provider can enter offering services, as well as adding points where these services can be found. These services can be included by each Tour Creator in any predesigned or for a custom tour. Given that the platform supports Business-to-Business (B2B) capabilities, a tour is enriched with offered services intended to be provided by third-party companies or freelancers. For example, at a museum a point of interest can be added pointing to a tour guide that offers guided tours. Accordingly, a travel agency could list its own recommended tour to be delivered through the OPTORER platform at a certain cost. A user can be added to this role by applying for registration by filling out a relative form.

- -

- Provider of feedback: The Provider of feedback role has the ability to provide feedback in relation to the service, the tours as a whole or in relation to individual PoIs or professionals/services involved in the tour. The feedback can take the form of an evaluation but, also, about providing relevant content. Every user of the service who participated in an offered tour will be able to provide feedback.

3. System Architecture

- -

-

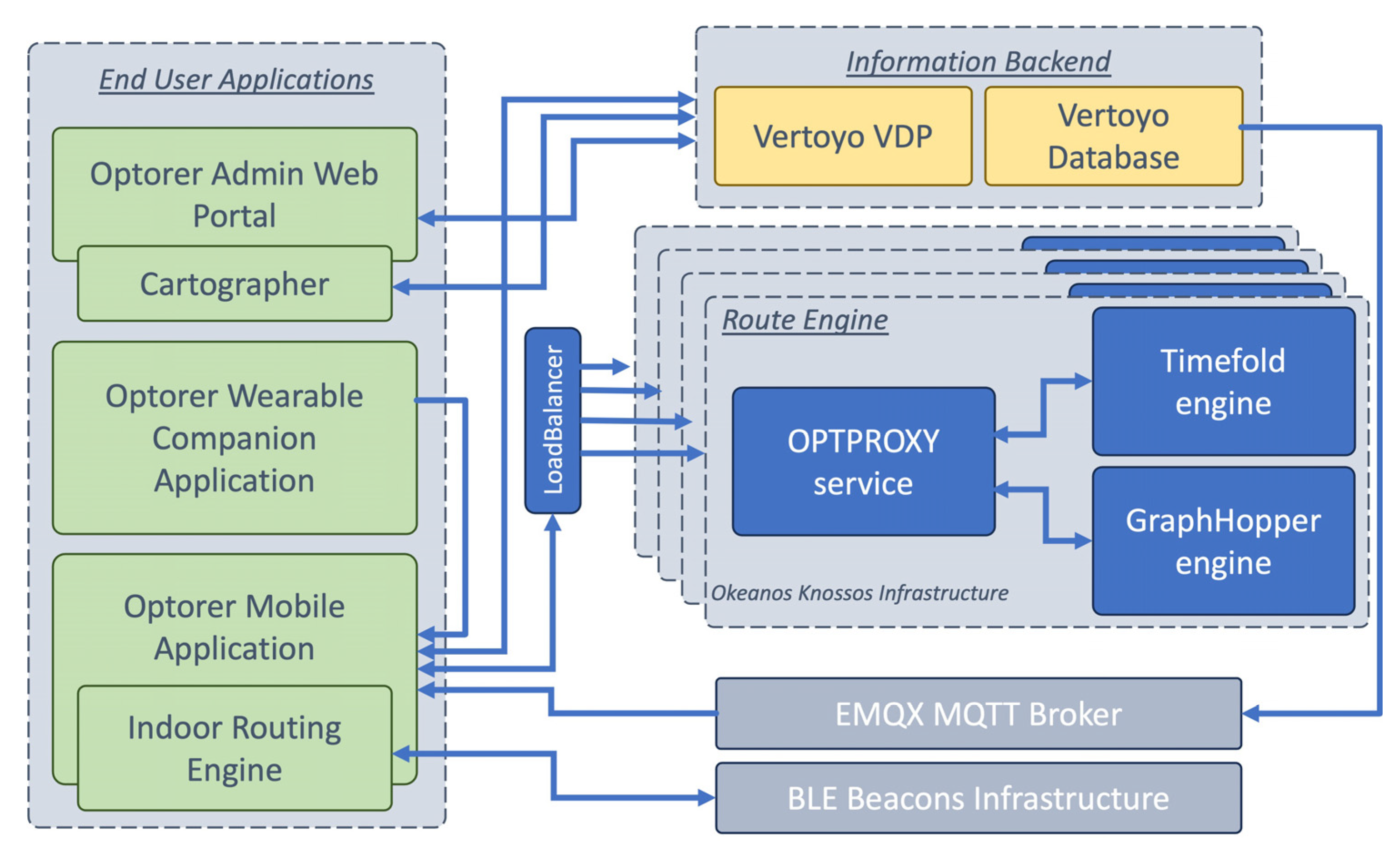

the “User Applications” subsystem consists of all the applications that a user of the system can access. There are three types of applications in general in OPTORER:

- o

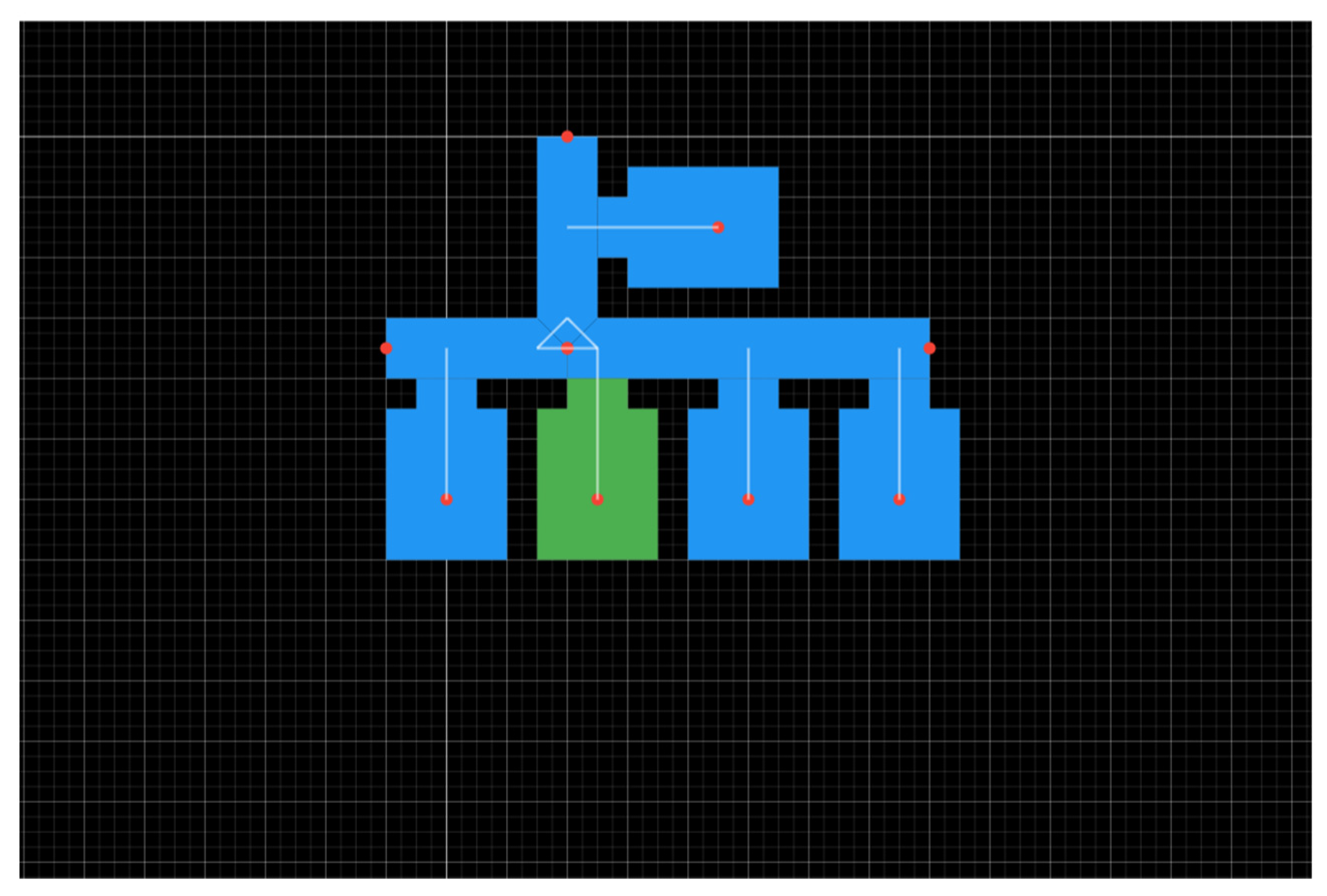

- a web application which provides the authorized users (i.e., those with the role of Administrator, Tour Creator, Cartographer and External Service Provider) access to the Development subsystem. This access is provided through two different tools, the OPTORER Admin Web Portal tool and the Cartographer tool. The former allows for administration actions to take place along any content management actions (e.g., adding, removing or editing information for PoIs or AoIs) while the latter is the tool by which content managers can add the map of an indoor tour. This is done using the graphical environment available from the Cartographer tool in order to draw the floor plan of the interior space, as well as to register the points where the BLE Beacons have been placed in the respective map. The last step of the process includes setting up of Internal PoIs.

- o

-

a mobile application, that is the main way in which the end user interacts with the OPTORER system and how (s)he can access and enjoy the functionalities and services offered by it. The mobile application has direct connectivity with all the other main tools in the other sub-systems (seen in Figure 2) including:

- Connection to the wearable device application based on the Bluetooth protocol and using the native interfaces offered by its operating system.

- Connection to the tools in the Development subsystem using the HTTP protocol and the available REST APIs, in order to obtain and configure the application relevant information for the user.

- Connection to the Routing Engine tool inside the Controller subsystem using the HTTP RESTful interfaces offered by the corresponding GraphHopper tool, [11].

- Connection to the EMQX MQTT Broker tool in the Infrastructure subsystem, a real-time communication infrastructure using an MQTT client and subscribing to the channels that offer information related to emergency events that can affect the user experience. Here there is a change in the initial design (Figure 1), as the MQTT (pub-sub) broker is moved to the Infrastructure subsystem instead of the Controller subsystem since the emphasis is given to the communication of the information, rather than the control and processing of it.

- Connection to the Indoor Location Infrastructure tool using the Bluetooth protocol for continuous scanning of the available BLE Beacons and real-time positioning of the user on the indoor map.

- Integration of Indoor Routing Engine functionality, using Dart language for smooth operation of the application. This tool is used to locate and position the user when (s)he moves in an indoor room. Also, the tool offers navigation using a pre-installed indoor map (by using the Cartographer tool).

- o

- A smartwatch application (OPTORER Wearable Companion Application) that provides information to the mobile application related to the user’s physical state. This is done locally by pairing the user's watch with their mobile device using the Bluetooth protocol. This information contributes to the user experience exclusively and only in real time during a visit, while at any time, the user can through the mobile application delete these measurements from the memory of the application.

- -

- The “Development subsystem”, or in other words the Information Backend, consists of two main tools (i.e., Vertoyo VDP and Vertoyo Database) that incorporate and deliver the actions and operations described in Section 2 for this subsystem. In more details, Vertoyo Digital Platform (or Vertoyo VDP) is a platform based on the Java programming language and can be used to support complex web portals and mobile applications through a variety of ready-to-use features such as managing user roles/privileges, entity management/registration. It comes with advanced support functions and management of business workflows (Business Process Management -BPM), task scheduling and can be easily interfaced with Push/Email notification services, as well as with third-party systems, exposing or consuming programming interfaces such as REST or SOAP APIs. VDP communicates directly with the Vertoyo Database tool, a PostgreSQL DB that implements a custom SQL schema to store data for: a) User Management - encrypted data for sensitive fields, b) Content Management - static content of the Web application (e.g., PoI or AoIs), c) Custom Entities Management – supporting data encryption. It is used to store the alerts coming from the MQTT pub-sub broker in OPTORER.

- -

- The “Controller subsystem”, which is now called the Route Engine component, is a complex routing module that consists of three tools: the OPTPROXY Proxy Application, the Graphhopper Routing Engine and the Timefold Optimization Engine. With the service implemented by the OPTPROXY proxy application, it is possible to communicate with the mobile application to submit the routing request and send a response to the user. Internally, the OPTROXY application takes care of communicating with the other two engine tools to return the optimal visit order if desired, as well as the optimal routing between them on the road network based on the user profile, the desired characteristics submitted by the user, and possible external constraints due to unforeseen events. In the final version, load scaling is achieved by installing the “Route Engine” as a set consisting of the proxy application, the Graphhopper routing engine and the Timefold optimization engine on multiple virtual machines (Virtual machines) in a virtual server infrastructure and sharing the load on them (round robin).

- -

-

The “Infrastructure subsystem” consists of two tools: the EMQX MQTT Broker and the BLE Beacons Infrastructure. The former is a real-time information communication tool, implemented by an EMQX Broker. Through this, all the necessary information of any emergency events confirmed by the admin portal are transmitted to the end user application on the mobile phone. In real time, this information is filtered based on the importance of the event, the current location and the status of the user. For smooth and optimal operation of the platform, the real-time communication infrastructure is connected to two of the other tools of the system:

- o

- The mobile application for end-users, for the dynamic and customized routing of the user, based on emergency events.

- o

- The Information backend to send real-time and continuously update the VDP database and the mobile application about the status of emergency events, during a browsing.

3.1. Technical Challenges

3.1.1. Indoor Location and Positioning

- ▪

- Wi-Fi fingerprinting

- ▪

- Inertial Navigation

- ▪

- Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) beacons

- ▪

- Visual-based Navigation

- ▪

- Magnetic Field-based Navigation

- o

- Fingerprinting [14]: This method involves creating a database of signal fingerprints at known locations within a building and by using these fingerprints to estimate a user's location based on signals received from nearby radio beacons. This approach has proven efficient in many indoor environments, but can be computationally demanding, requiring frequent updates as the environment changes.

- o

- Trilateration [15,16]: This method involves using the signals from at least three radio beacons to triangulate a user's location. Free Space Path Loss (FSPL) formula is a popular method to be combined with trilateration since it converts the Received Signal Strength Indices (RSSI) to beaccon distance and then use this as input to the trilateration process to convdert distances from known beacon location to coordinates. This approach is less computationally demanding than signal fingerprinting, but may be less accurate in environments with obstacles or other sources of interference.

- o

- Machine learning [17,18]: This approach involves training machine learning algorithms to recognize patterns in signal data and use these patterns to estimate a user's location. This approach has the potential to be highly accurate and adaptable to changing environments, but requires large amounts of training data and can be sensitive to changes in the signal environment.

3.1.2. Physical and psychological user state assessment

3.1.3. Dynamic Multi-Criteria Routing Optimization

4. Evaluation Results

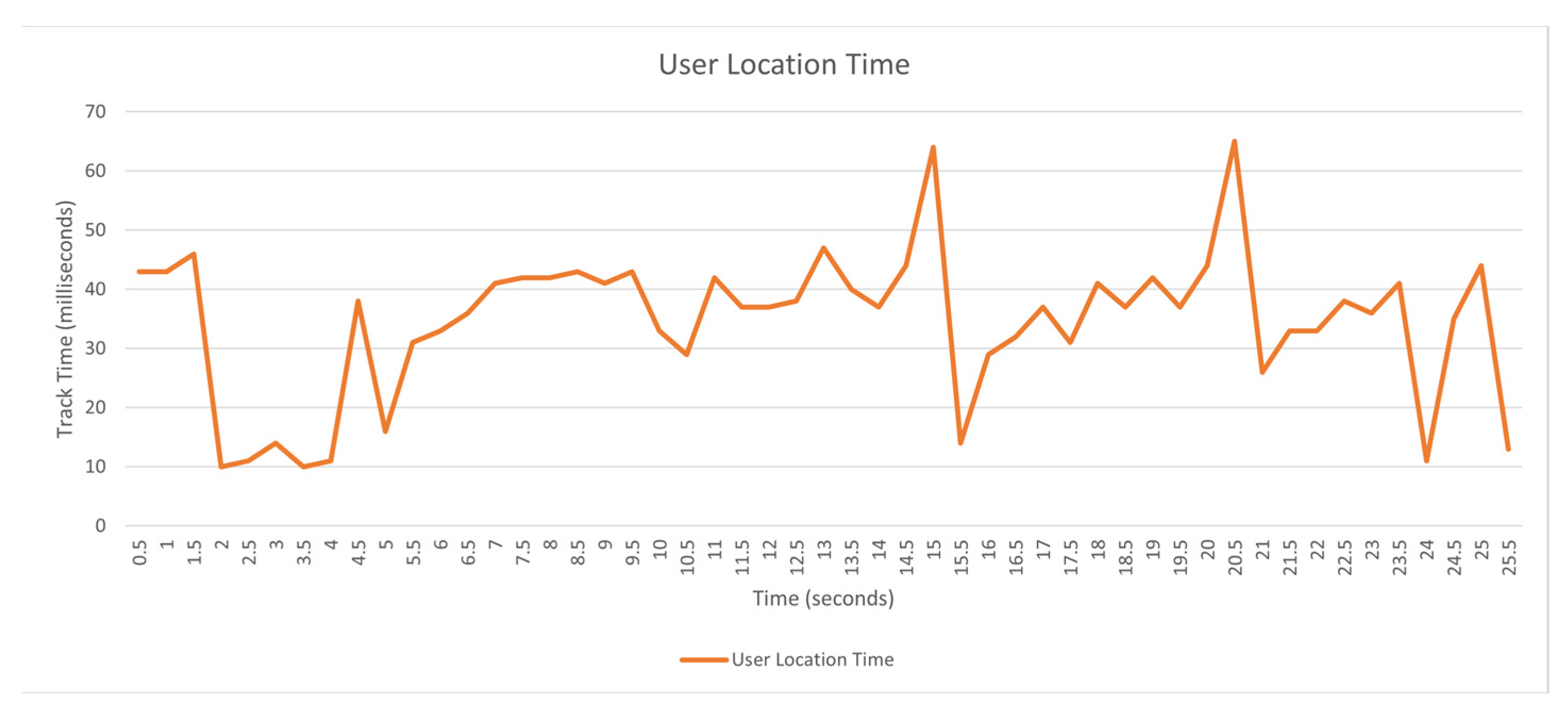

| KPI | Target Value | Achieved Value | Tool Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| User Location Time | < 3 sec (on avg) | < 65 msec | Flutter Dart Code |

| User Location Accuracy | < 1.5 m | ~1 m | Flutter Dart Code |

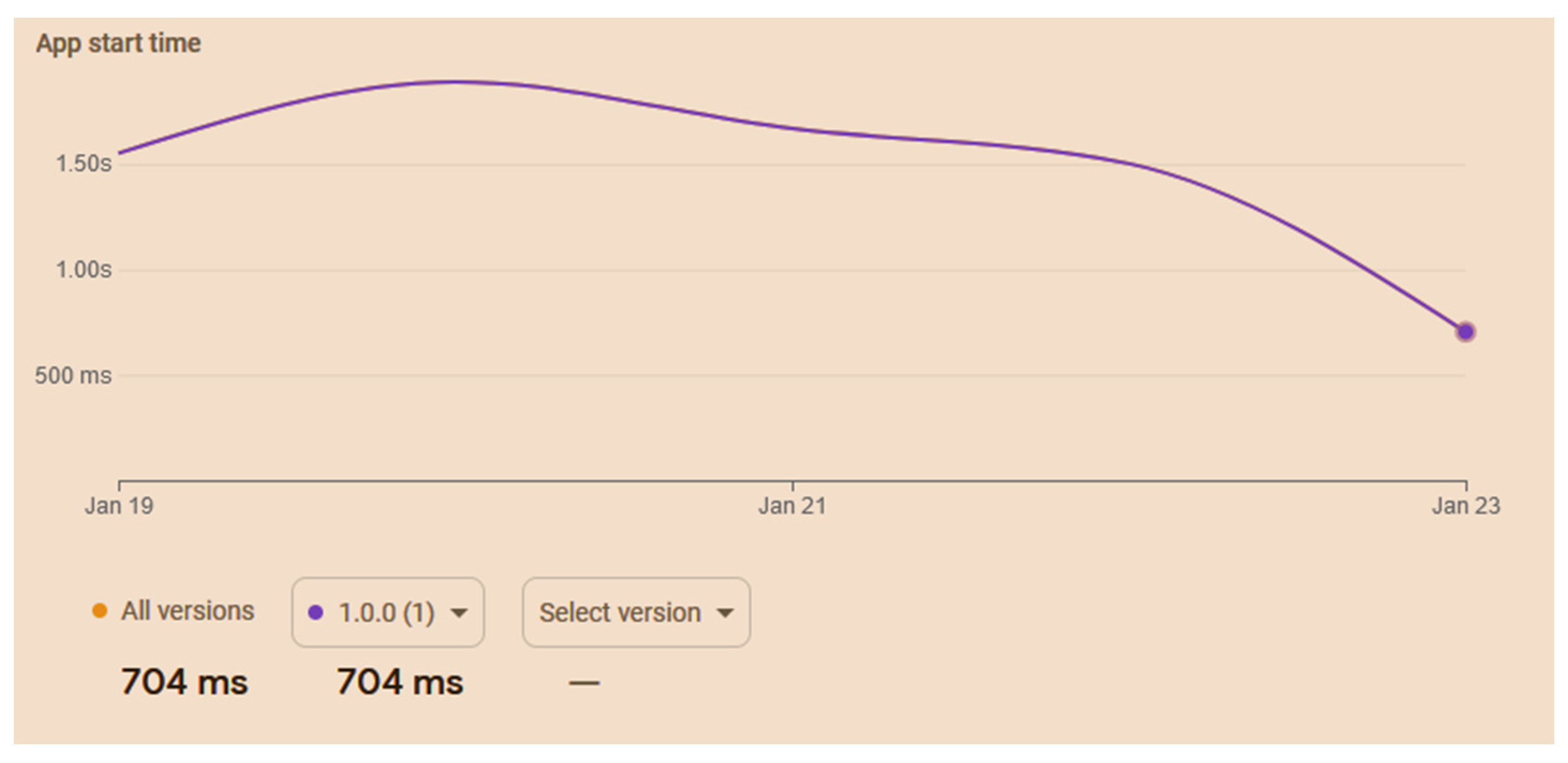

| Time to load the Application | < 3 sec | < 1.58 sec | Firebase APM |

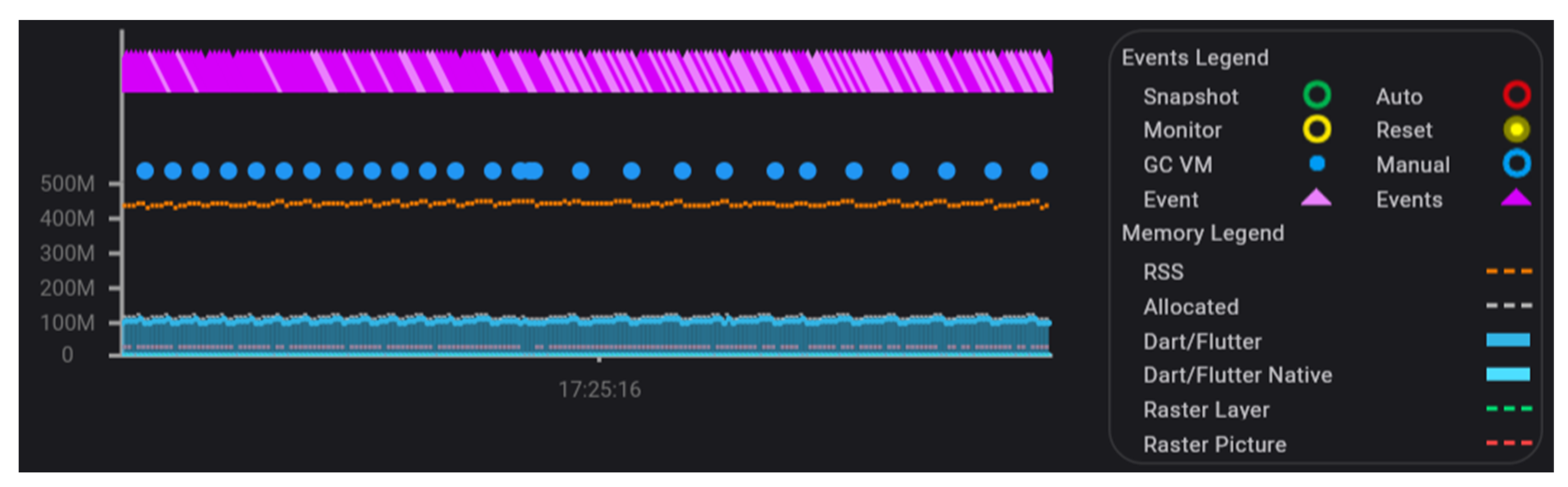

| Memory Usage in mobile phone during app execution | <= 512 MB | <150 MB | Flutter DevTools |

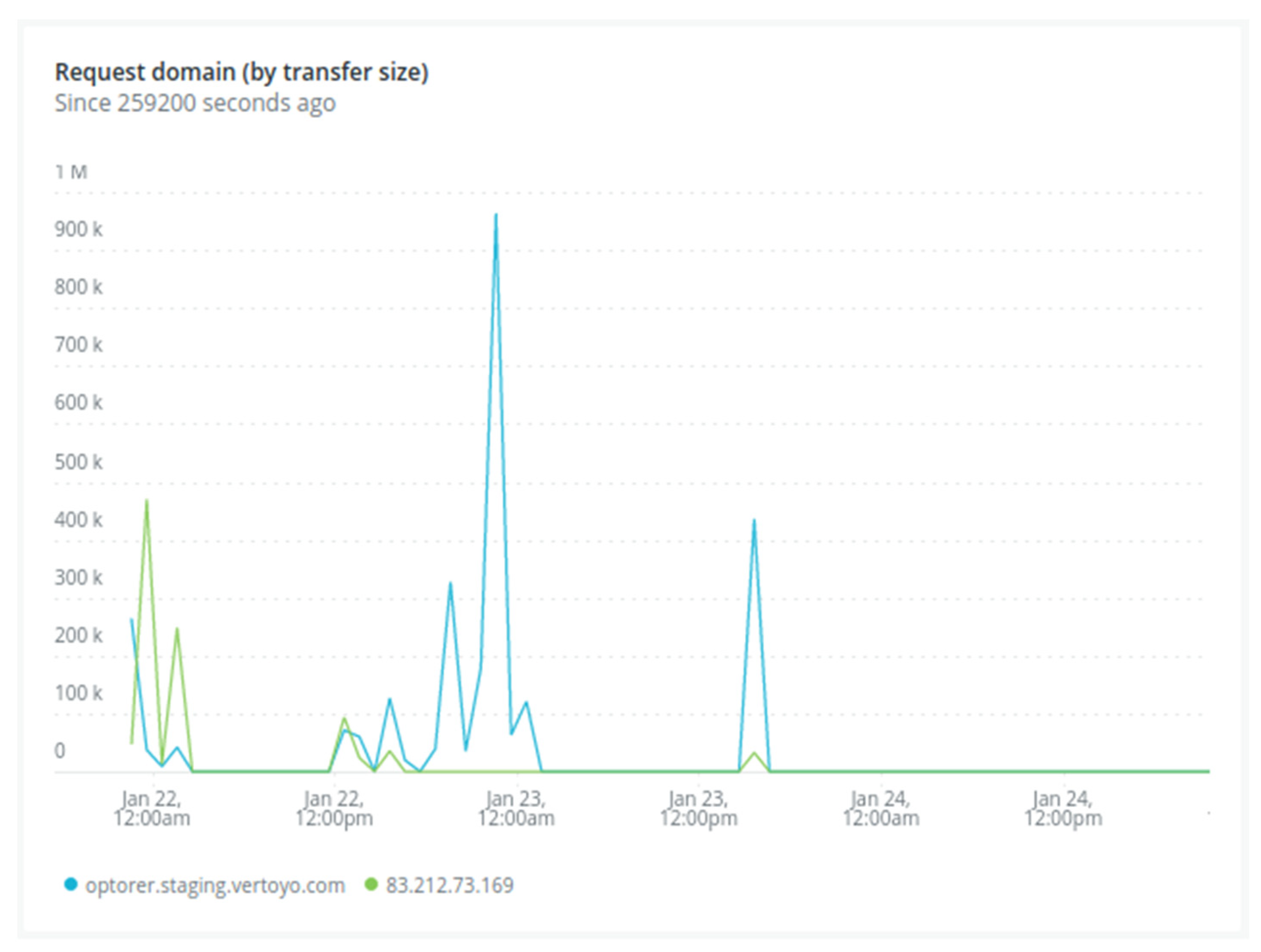

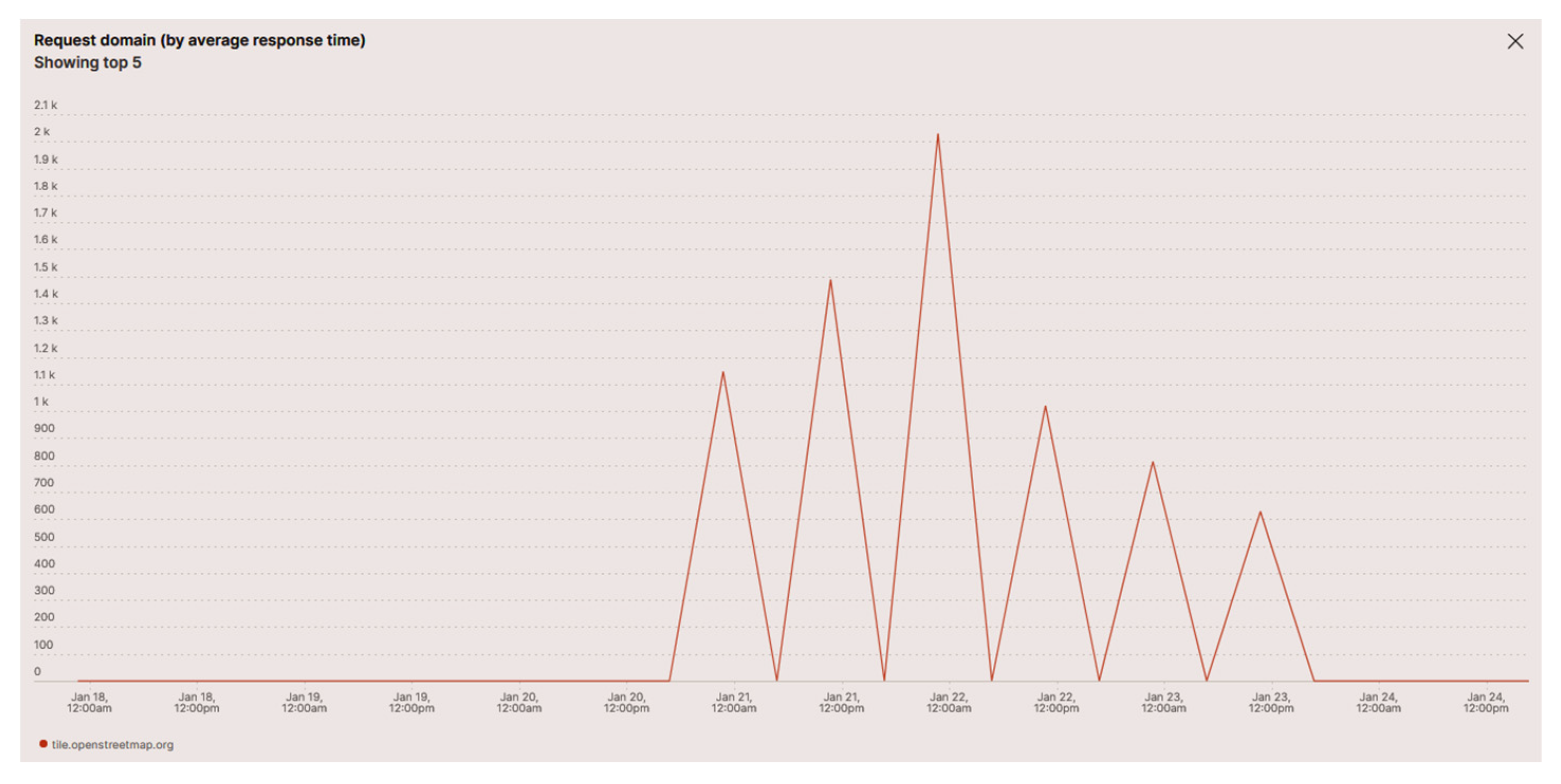

| Data / min needed to follow a route in the mobile phone (on avg) | <= 1 MB / min [36] | < 500 KB / min | New Relic APM360 |

| Time to place the user location on the map | <= 20 sec [37] [38] | < 4 sec | New Relic APM360 |

| Average battery consumption on the mobile phone | <= 150 mAh [39] | < 90 mAh | AccuBattery App |

| Time to load the map (Example: when moving from outdoors to indoors) | <= 10 sec | < 3 sec | Flutter Dart Code |

| Concurrent requests | Active solvers | Minimum request processing time (in seconds) | Average request processing time (in seconds) | Maximum request processing time (in seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 8 | 1,25 | 1,28 | 1,3 |

| 16 | 8 | 1,28 | 1,76 | 2,23 |

| 32 | 8 | 1,07 | 2,44 | 3,73 |

| 64 | 8 | 1,32 | 4,51 | 7,79 |

| 128 | 8 | 1,32 | 6,86 | 14,69 |

| 200 | 8 | 1,32 | 9,53 | 21,42 |

| 8 | 16 | 1,27 | 1,29 | 1,32 |

| 16 | 16 | 1,27 | 1,33 | 1,4 |

| 32 | 16 | 1,16 | 1,76 | 2,36 |

| 64 | 16 | 1,24 | 2,42 | 3,57 |

| 128 | 16 | 2,21 | 4,85 | 8,51 |

| 200 | 16 | 2,56 | 6,54 | 11,16 |

| 8 | 32 | 1,27 | 1,28 | 1,29 |

| 16 | 32 | 1,27 | 1,31 | 1,37 |

| 32 | 32 | 1,29 | 1,50 | 1,93 |

| 64 | 32 | 1,12 | 1,82 | 2,48 |

| 128 | 32 | 2,31 | 3,27 | 4,87 |

| 200 | 32 | 2,36 | 4,55 | 7,44 |

| 8 | 64 | 1,28 | 1,29 | 1,3 |

| 16 | 64 | 1,28 | 1,30 | 1,33 |

| 32 | 64 | 1,18 | 1,52 | 2,25 |

| 64 | 64 | 1,1 | 1,81 | 2,5 |

| 128 | 64 | 1,38 | 2,67 | 3,63 |

| 200 | 64 | 1,72 | 3,55 | 5,76 |

| 8 | 96 | 1,25 | 1,27 | 1,29 |

| 16 | 96 | 1,24 | 1,26 | 1,3 |

| 32 | 96 | 1,25 | 1,39 | 1,55 |

| 64 | 96 | 1,19 | 1,91 | 2,74 |

| 128 | 96 | 1,77 | 2,54 | 3,28 |

| 200 | 96 | 1,37 | 3,60 | 6,53 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A : Optorer Mobile Application Memory and Network Performance

References

- A. Kontogianni and E. Alepis, "Smart tourism: State of the art and Literature Review for the last six years," Array, vol6, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Mehraliyev, I. C. Chan, Y. Choi, M. A. Koseoglu, and R. Law, "A state-of-the-art review of smart tourism research," Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 78-91, 2020,. [CrossRef]

- J. Dorcic, J. Komsic, and S. Markovic, "Mobile Technologies and applications towards Smart Tourism – State of the art," Tourism Review, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 82-103, 2019. [CrossRef]

- OPTORER project, Optimal routing and exploration of touristic and cultural areas of interest within Attica given personalized adaptive preferences, promoted underlying purpose and interactive experience - OPTORER PPE: ATTP4-0353772, online link: https://www.optorer-project.gr/.

- Bekkelien, Anja, Michel Deriaz, and Stéphane Marchand-Maillet., "Bluetooth indoor positioning," Master's thesis, University of Geneva (2012).

- Christoph Fuchs, Nils Aschenbruck, Peter Martini, and Monika Wieneke, "Indoor tracking for mission critical scenarios: A survey," Pervasive and Mobile Computing, vol. 7(1), pp. 1-15, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Guolin Sun, Jie Chen, Wei Guo, K.J. Ray Liu, "Signal processing techniques in network-aided positioning: a survey of state-of-the-art positioning designs," IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 22, no. 4, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Mayu Sumida, Teruhiro Mizumoto, Keiichi Yasumoto, "Estimating heart rate variation during walking with smartphone," in UbiComp '13: Proceedings of the 2013 ACM international joint conference on Pervasive and ubiquitous computing, Pages 245, September 2013.

- Paolo Toth and Daniele Vigo (Eds.), The vehicle routing problem, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2021.

- "Optaplanner metaheuristics engine," [Online]. Available: https://www.optaplanner.org/.

- "GraphHopper," [Online]. Available: https://www.GraphHopper.com/.

- A. Riady and G. P. Kusuma, "Indoor positioning system using hybrid method of fingerprinting and pedestrian dead reckoning," Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 34, no. 9, p. 7101–7110, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Pakanon, M. Chamchoy and P. Supanakoon, "Study on accuracy of trilateration method for indoor positioning with Ble Beacons," in 6th International Conference on Engineering, Applied Sciences and Technology (ICEAST) [Preprint] 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Kluge, C. Groba and T. Springer, "Trilateration, Fingerprinting, and Centroid: Taking Indoor Positioning with Bluetooth LE to the Wild," in IEEE 21st International Symposium on "A World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks" (WoWMoM), Cork, Ireland, 2020, pp. 264-272. [CrossRef]

- F. Zafari and J. Gao, "A survey of indoor positioning systems and technologies," Journal of Location Based Services, 2016 vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 180-206.

- N. S. Kodippili and D. Dias, "Integration of fingerprinting and trilateration techniques for improved indoor localization," in Seventh International Conference on Wireless and Optical Communications Networks - (WOCN), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2010, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- A. Sashida, D. P. Moussa, M. Nakamura and H. Kinjo, "A Machine Learning Approach to Indoor Positioning for Mobile Targets using BLE Signals," in 34th International Technical Conference on Circuits/Systems, Computers and Communications (ITC-CSCC), JeJu, Korea (South), 2019, pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- P. Sthapit, H.-S. Gang and J.-Y. Pyun, "Bluetooth Based Indoor Positioning Using Machine Learning Algorithms," in IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics - Asia (ICCE-Asia), JeJu, Korea (South), 2018, pp. 206-212. [CrossRef]

- Margaritis, D. , Leligou, H.C., Kogias, D.G., “One Dimensional Fingerprinting as an Alternative to the Free Space Path Loss Equation for Indoor Positioning”. In: Novel & Intelligent Digital Systems: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference (NiDS 2023). NiDS 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 783. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- A.. G. Bonomi and K. R. Westerterp, "Advances in physical activity monitoring and lifestyle interventions in obesity: A review," Int. J. Obesity, vol. 36, pp. 167-77, Feb.2012. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Janney, A. Fagiolini, H. A. Swartz, J. M. Jakicic, R. G. Holleman and C. R. Richardson, "Are adults with bipolar disorder active? Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior using accelerometry," J. Affective Disorders, Vols. 152-154, pp. 498-504, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Reilly, V. Penpraze, J. Hislop, G. Davies, S. Grant and J. Y. Paton, "Objective measurement of physical activity and sedentary behaviour: Review with new data," Arch. Dis. Childhood, vol. 93, pp. 614-619, Jul. 1, 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Reiser and E. A. Schlenk, "Clinical use of physical activity measures," J. Amer. Acad. Nurse Practitioners, vol. 21, pp. 87-94, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Abel, J. Hannon, D. Mullineaux and A. Beighle, "Determination of step rate thresholds corresponding to physical activity intensity classifications in adults.," J Phys Act Health, 2011 Jan, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 45-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Toth and D. Vigo, An overview of vehicle routing problems, in The Vehicle Routing Problem (P. Toth and D. Vigo eds.), SIAM Monographs on Discrete Mathematics and Applications, 2002.

- E. L. Lawler, J. K. Lenstra, A. H. G. Rinnooy Kan and D. B. Shmoys, The Traveling Salesman Problem: A Guided Tour of Combinatorial Optimization, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-90413-9., 1985.

- D. P. Bovet and P. Crescenzi, Introduction to the Theory of Complexity. Prentice Hall. p. 69, ISBN 0-13-915380-2., 1994.

- L. Bianchi, M. Dorigo, L. M. Gambardella and W. J. Gutjahr, A survey on metaheuristics for stochastic combinatorial optimization, Natural Computing. 8 (2): 239–287., 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Dijkstra, "A note on two problems in connexion with graphs," Numerische Mathematik, vol. 1, pp. 269-271, 1959. S2CID 123284777. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Nilsson, The Quest for Artificial Intelligence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521122931., 2009-10-30.

- "OptaPlanner," [Online]. Available: https://www.optaplanner.org/.

- "GraphHopper," [Online]. Available: https://www.graphhopper.com/.

- "OpenStreetMap," [Online]. Available: https://www.openstreetmap.org/about.

- "Leaflet.js," [Online]. Available: https://leafletjs.com/.

- “Timfold”, [Online]. Available: https://timefold.ai.

- eSim Europe, “How much data does Google Maps use?”, March 2023, Web: https://europeesim.

- López, J.M.L. , Aguilar, F.L., Abascal, J.J.C. (2012). A-GPS Performance in Urban Areas. In: Rodriguez, J., Tafazolli, R., Verikoukis, C. (eds) Mobile Multimedia Communications. MobiMedia 2010. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, vol 77. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Frank Van Diggelen, “Google to improve urban GPS accuracy for apps”, December 2020, Web: https://www.gpsworld. 20 December.

- Greenspector & ATOS, “Consumption of TOP 30 most popular mobile applications”, July 2019, Web: https://greenspector.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Atos-GREENSPECTOR-TOP30-benchmark-english.pdf.

- “Firebase Performance Monitoring”, [Online], Available: https://firebase.google.

- “New Relic APM 360”, [Online], Available: https://newrelic.

- “Android Studio IDE”, [Online], Available: https://developer.android.

- “Flutter DevTools”, [Online], Available: https://docs.flutter.

- “AccuBattery App [Online], Available: https://accubatteryapp.

- “Passmark”, [Onkline], Available: https://www.passmark.

- “PassMark - CPU Mark, High Mid Range CPUs”, [Online], Available: https://www.cpubenchmark.net/mid_range_cpus. html.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).