Submitted:

05 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Imaging tools for the detection of iCNV

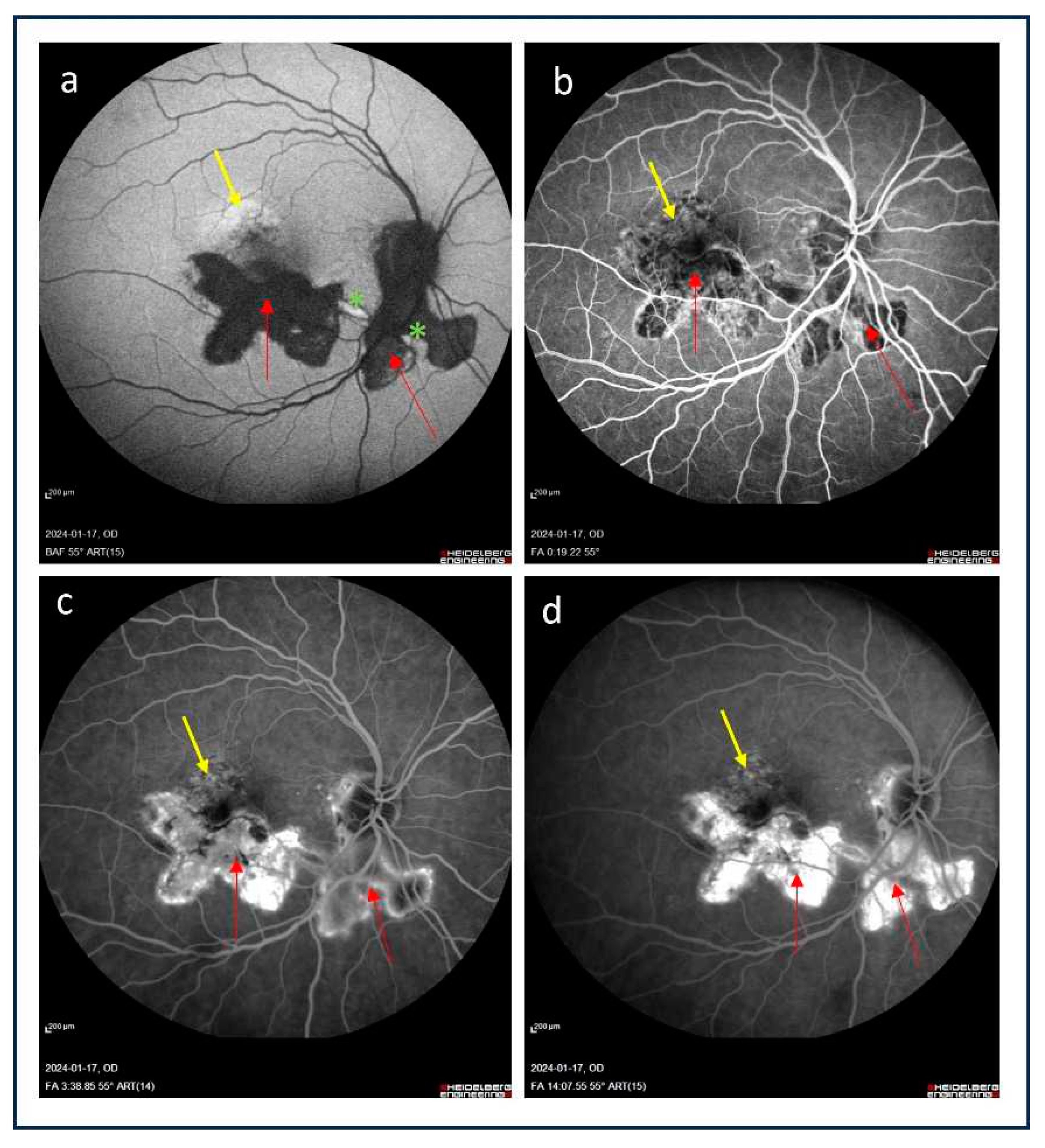

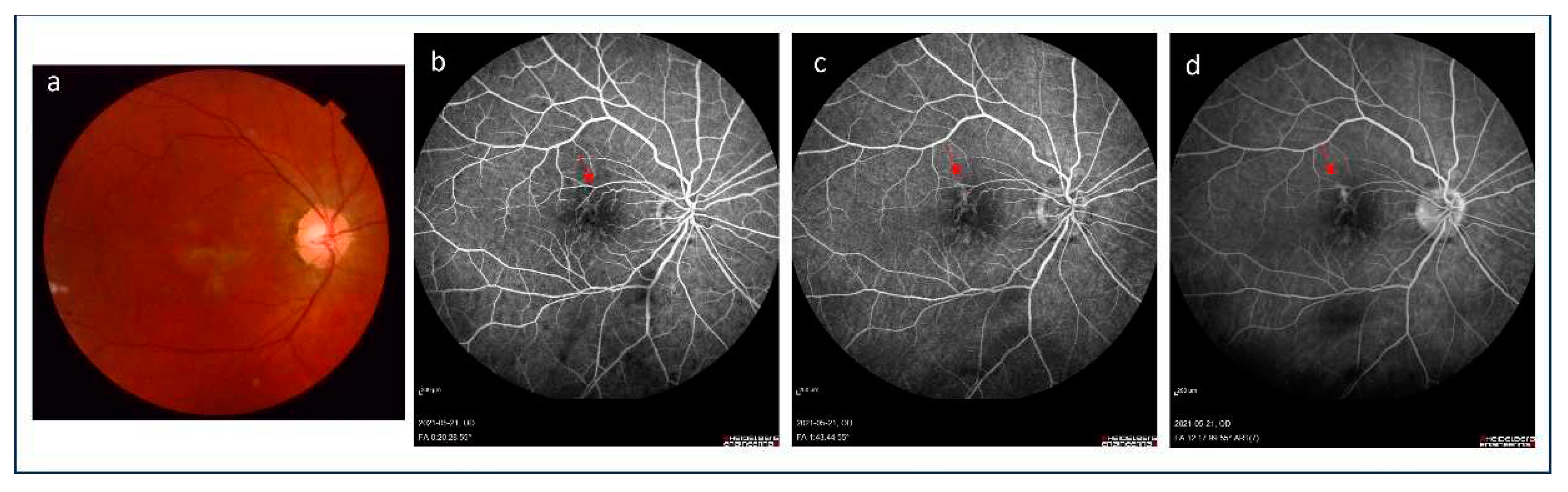

2.1. Fluorescein angiography

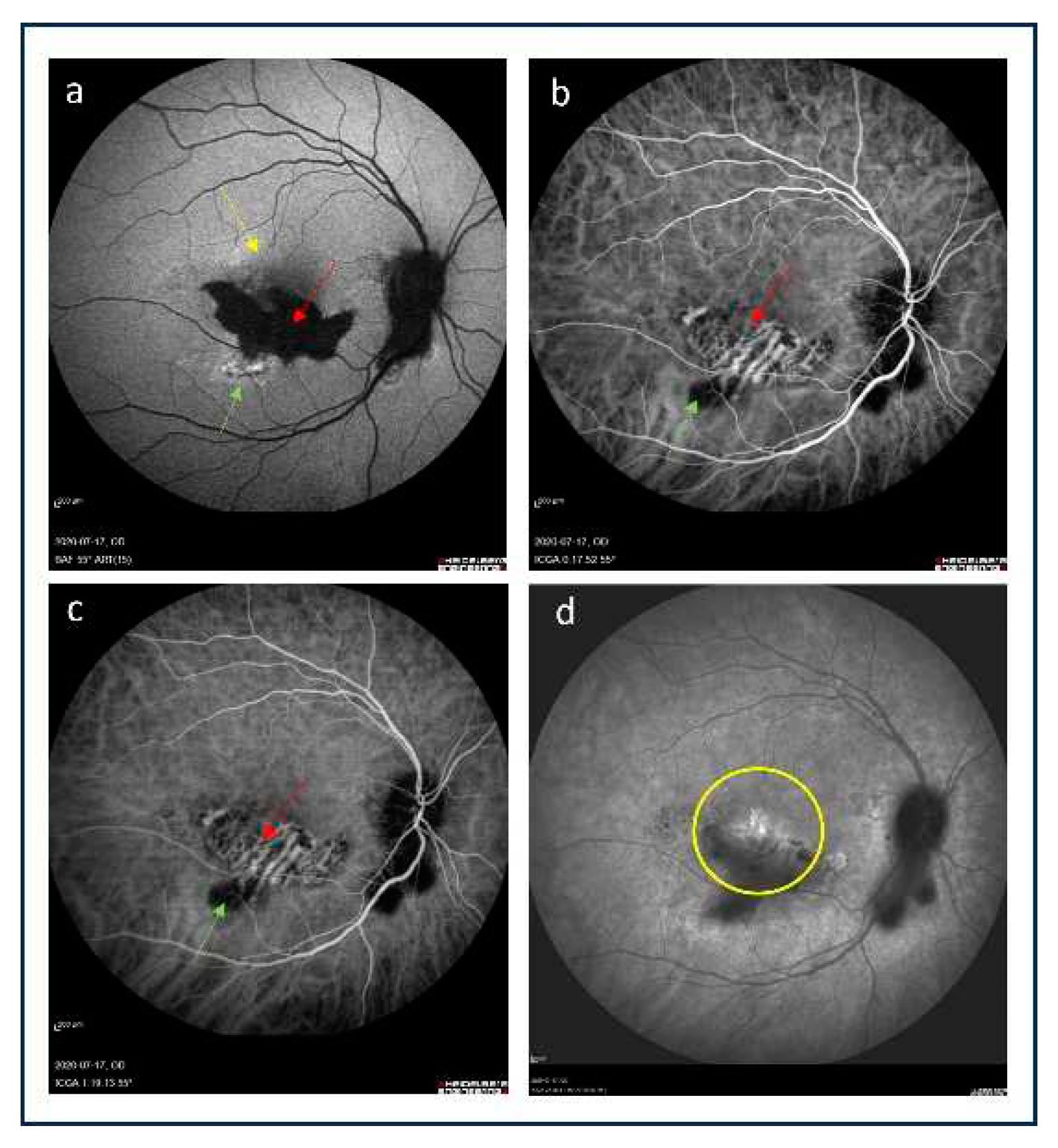

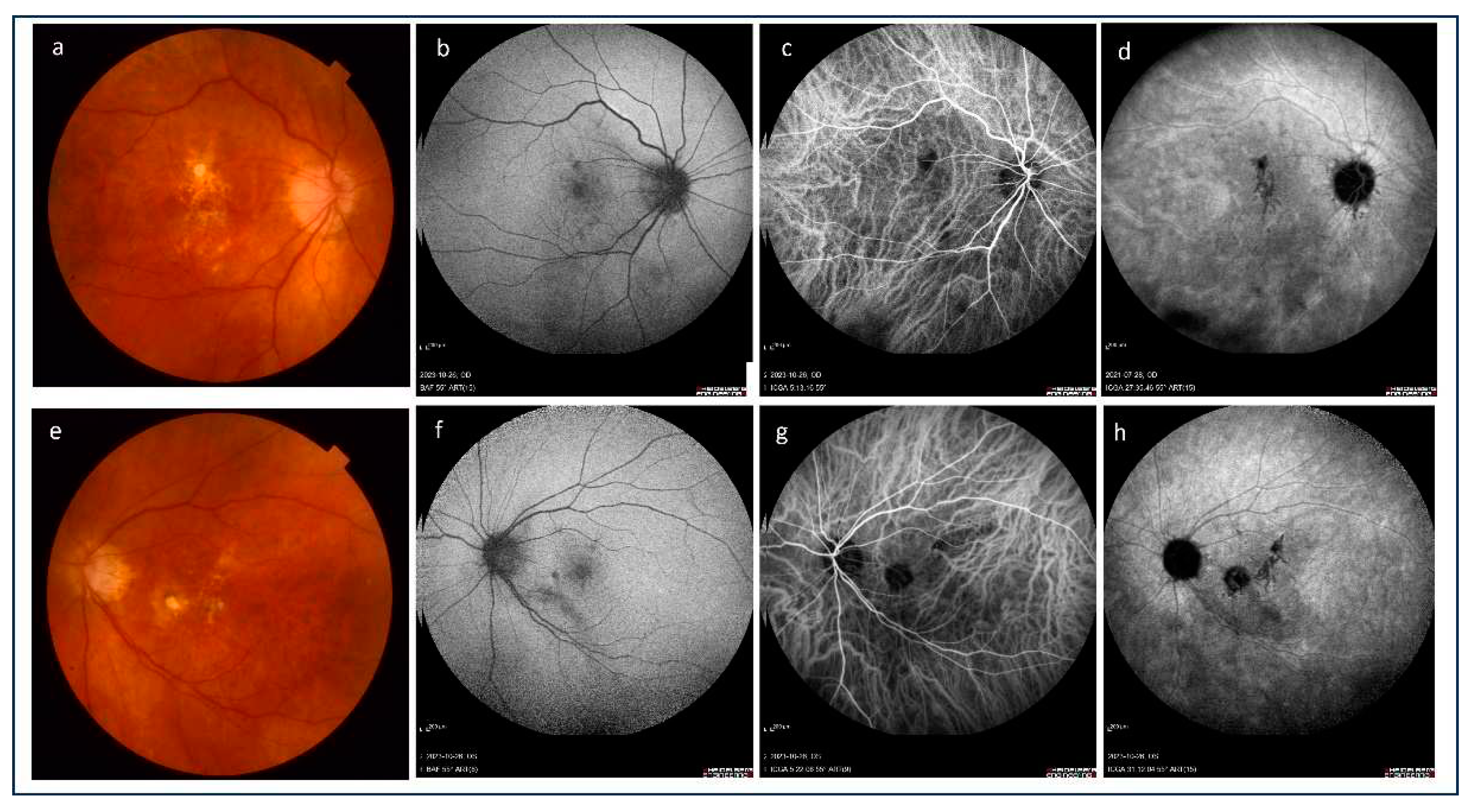

2.2. Indocyanine green angiography

2.3. Optical coherence tomography

2.4. Optical coherence tomography angiography

2.5. Near-infrared autofluorescence imaging

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, A.; Invernizzi, A.; Singh, R.B.; Foulsham, W.; Aggarwal, K.; Handa, S; Agrawal, R.; Pavesio., C.; Gupta, V. An update on inflammatory choroidal neovascularization: epidemiology, multimodal imaging, and management. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, N.; Kelly, S.; Majid, M.A.; Bailey, C.B.; Dick, A.D. Inflammatory choroidal neovascular membrane in posterior uveitis-pathogenesis and treatment. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 58, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, P.; Lettieri, M.; Fortuna, C.; Manoni, M.; Giovannini, A. Inflammatory choroidal neovascularization. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009, 16, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.L.; Pistilli, M.; Pujari, S.S.; Liesegang, T.L.; Suhler, E.B.; Thorne, J.E.; Foster, C.S.; Jabs, D.A.; Levy-Clarke, G.A.; Nussenblatt, R.B.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; Kempen, J.H. Risk of choroidal neovascularization among the uveitides. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 156, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyer, R.F.; Gass, D.J. Multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. A syndrome that mimics ocular histoplasmosis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1984, 102, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.M.; Schatz, H. Recurrent Multifocal Choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 1986, 93, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J., Jr.; Folk, J.C.; Reddy, C.V.; Kimura, A.E. Visual prognosis of multifocal choroiditis, punctate inner choroidopathy, and the diffuse subretinal fibrosis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1996, 103, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnood, D.; Madhusudhan, S.; Tsaloumas, M.D.; Waheed, N.K.; Keane, P.A.; Denniston, A.K. Punctate inner choroidopathy: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017, 62, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, I.C.; Cunningham, E.T., Jr. Ocular neovascularization in patients with uveitis. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2000, 40, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatci, A.O.; Ayhan, Z.; Engin Durmaz, C.; Takes, O. Simultaneous Single Dexamethasone Implant and Ranibizumab Injection in a Case with Active Serpiginous Choroiditis and Choroidal Neovascular Membrane. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2015, 6, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kępka, M.; Brydak-Godowska, J.; Ciszewska, J.; Turczyńska, M.; Ciszek, M.; Kęcik, D. Clinical features, diagnosis and management of serpiginuos choroiditis. Ophthalmol. J. 2022, 7, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.A.; Gupta, A.; Dustin, L.; Chee, S.P.; Okada, A.A.; Khairallah, M.; Bodaghi, B.; Lehoang, P.; Accorinti, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Prabriputaloong, T.; Read, R.W. Frequency of distinguishing clinical features in Vogt Koyanagi-Harada disease. Ophthalmology. 2010, 117, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucker, A.J.; Deglin, E.A.; Bene, C.; Hoffman, M.E. Subretinal Choroidal Neovascularization in Birdshot Retinochoroidopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1985, 99, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.; Hariharan, L.; Ho, A.C.; Kempen, J.H. Peripapillary choroidal neovascularization in pars planitis. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2013, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nageeb, M.R. Intermediate Uveitis Complicated by Peripapillary Choroidal Neovascularization. Cureus. 2022, 14, e31040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, M.; Harada, T.; Kiribuchi, T.; Ohashi, T.; Majima, J. Subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in uveitis. Ophthalmologica. 1996, 210, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliarini, S.; Piguet, B.; Ffytche, T.J.; Bird, A.C. Foveal involvement and lack of visual recovery in APMPPE associated with uncommon features. Eye (Lond). 1995, 9, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, E.M.; Sletten, K.R.; Kayser, D.L.; Folk, J.C.; James, C. Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy And Choroidal Neovascularization. Retina 2005, 25, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatci, A.O.; Ayhan, Z.; Ipek, S.C.; Soylev Bajin, M. Intravitreal Aflibercept as an Adjunct to Systemic Therapy in a Case of Choroidal Neovascular Membrane Associated with Sympathetic Ophthalmia. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 48, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouvas, A.A.; Ladas, I.D.; Papakostas, T.D.; Moschos, M.M.; Vergados, I. Intravitreal ranibizumab in a patient with choroidal neovascularization secondary to multiple evanescent white dot syndrome. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 17, 996–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burova, M.; Stepanov, A.; Almesmary, B.; Jiraskova, N. Choroidal neovascularization in a patient after resolution of multiple evanescent white dot syndrome: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2022, 10, e05802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Y.A.; Zhang, A.Y.; Wenick, A. Evolution of Choroidal Neovascularization due to Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome on Multimodal Imaging including Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2018, 13, 2018:4098419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Hoang, Q.V.; Chau, F.Y.; Blair, M.P.; Lim, J.I. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for choroidal neovascularization in ocular histoplasmosis. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2014, 8, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.S.; Fick, T.A.; Saggau, D.D.; Barnes, C.H. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for choroidal neovascularization secondary to ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Retina 2012, 32, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, H.S.; Shah, G.K.; Blinder, K.J. Treatment of CNV secondary to presumed ocular histoplasmosis with intravitreal aflibercept 2.0 mg injection. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 51, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonnevylle, K.E.; Stanescu-Segall, D. Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Treatment of Bilateral Candida Chorioretinitis Complicated with Choroidal Neovascularization. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2020, 28, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampol, L.M.; Sung, J.; Walker, J.D.; Folk, J.C.; Townsend-Pico, W.A.; Lowder, C.Y.; Dodds, E.M.; Westrich, D.; Terry, J. Choroidal neovascularization secondary to Candida albicans chorioretinitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 121, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makragiannis, G.; Vahdani, K.; Carreño, E.; Lee, R.W.J.; Dick, A.D.; Ross, A.H. Bevacizumab for treatment of choroidal neovascularization secondary to candida chorioretinitis. Int. Ophthalmol. 2018, 38, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, S.L.; Owens, S.L.; Haller, J.A.; Knox, D.L.; Patz, A. Choroidal neovascularization as a late complication of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1981, 91, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willerson, D.; Aaberg, T.M.; Reeser, F.; Meredith, T.A. Unusual ocular presentation of acute toxoplasmosis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1977, 61, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevento, J.D.; Jager, R.D.; Noble, A.G.; Latkany, P.; Mieler, W.F.; Sautter, M.; Meyers, S.; Mets, M.; Grassi, M.A.; Rabiah, P.; Boyer, K.; Swisher, C.; McLeod, R. Toxoplasmosis Study Group. Toxoplasmosis-associated neovascular lesions treated successfully with ranibizumab and antiparasitic therapy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008, 126, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienicka, P. Eye toxoplasmosis complicated by choroidal neovascularization effectively treated with the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor aflibercept. Klin. Oczna 2022, 124, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampariello, D.A.; Primo, S.A. Ocular toxocariasis: a rare presentation of a posterior pole granuloma with an associated choroidal neovascular membrane. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1999, 70, 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lyall, D.; Hutchison, B.; Gaskell, A.; Varikkara, M. Intravitreal Ranibizumab in the treatment of choroidal neovascularisation secondary to ocular toxocariasis in a 13-year-old boy. Eye 2010, 24, 1730–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.Y.; Woo, S.J. Intravitreal Administration of Ranibizumab and Bevacizumab for Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Ocular Toxocariasis: A Case Report, Ocular Immunol. Inflamm. 2018, 26, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.M.; Yeh, T.S.; Sheu, S.J.; Liu, J.H. Macular subretinal neovascularization in choroidal tuberculosis. Ann. Ophthalmol. 1989, 21, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee Kim, E.; Rodger, D.C.; Rao, N.A. Choroidal neovascularization secondary to tuberculosis: Presentation and management. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2017, 6, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Fu, H.Y.; Guan, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Bai, H.Z. Concurrent tuberculous chorioretinitis with choroidal neovascularization and tuberculous meningitis: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol 2020, 20, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interlandi, E.; Pellegrini, F.; Pavesio, C.; De Luca, M.; De Marco, R.; Papayannis, A.; Mandarà, E.; Cuna, A.; Cirone, D.; Ciabattoni, C.; Liberali, T.; Zappacosta, A.; Latanza, L. Intraocular Tuberculosis: A Challenging Case Mimicking Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2021, 12, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutman, A.F.; Grizzard, W.S. Rubella retinopathy and subretinal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978, 85, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, M.B.; Romano, F.; Montagna, M.; Bandello, F. Large choroidal excavation in a patient with rubella retinopathy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 28, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, L.; Hasan, N.; Aron, N.; Chawla, R.; Sundar, D. Rubella retinopathy with choroidal neovascular membrane in a 7-year-old. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 1176–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, K.; Tanikawa, A.; Miyake, Y. Neovascular maculopathy associated with rubella retinopathy. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 44, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, M.; Ben Yahia, S.; Attia, S.; Jelliti, B.; Zaouali, S.; Ladjimi, A. Severe ischemic maculopathy in a patient with West Nile virus infection. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2006, 37, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, R.K.; Stoessel, K.M.; Adelman, R.A. Choroidal neovascularization associated with West Nile virus chorioretinitis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2007, 22, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zito, R.; Micelli Ferrari, T.; Di Pilato, L.; Lorusso, M.; Ferretta, A.; Ferrari, L.M.; Accorinti, M. Clinical course of choroidal neovascular membrane in West Nile virus chorioretinitis: a case report. J. Med. Case Reports 2021, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campa, C.; Costagliola, C.; Incorvaia, C.; Sheridan, C.; Semeraro, F.; De Nadai, K.; Sebastiani, A.; Parmeggiani, F. Inflammatory mediators and angiogenic factors in choroidal neovascularization: pathogenetic interactions and therapeutic implications. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 2010, 546826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Ambrosio, E.; Tortorella, P.; Iannetti, L. Management of uveitis-related choroidal neovascularization: from the pathogenesis to the therapy. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 450428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerquaglia, A.; Fardeau, C.; Cagini, C.; Fiore, T.; LeHoang, P. Inflammatory Choroidal Neovascularization: Beyond the Intravitreal Approach. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2018, 26, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Takeda, A.; Hasegawa, E.; Jo, Y.; Arima, M.; Oshima, Y.; Ryoji, Y.; Nakazawa, T.; Yuzawa, M.; Nakashizuka, H.; Shimada, H.; Kimura, K.; Ishibashi, T.; Sonoda, K.H. Interleukin-6 plays a crucial role in the development of subretinal fibrosis in a mouse model. Immunol. Medicine 2018, 41, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, O.; Adam, A.; Shinoda, K.; Stalmans, P.; Eckardt, C.; Lüke, M.; Bartz-Schmidt, K.U.; Grisanti, S. Expression of VEGF and PEDF in Choroidal Neovascular Membranes Following Verteporfin Photodynamic Therapy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 142, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, E.T. Jr; Pichi, F.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Freund, K.B.; Zierhut, M. Inflammatory Choroidal Neovascularization. Ocular Immunol. Inflamm. 2020, 28, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Ghanem, G.; Neri, P.; Dolz-Marco, R.; Albini, T.; Fawzi, A. Review for Diagnostics of the Year: Inflammatory Choroidal Neovascularization - Imaging Update. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2023, 31, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, S.; Fujiwara, T.; Murai, K.; Kubo, M.; Kurosaka, D. Idiopathic choroidal neovascularization as an early manifestation of inflammatory chorioretinal diseases. Retina 2008, 28, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Bansal, P.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, V.; Dogra, M.R.; Singh, R.; Katoch, D. Diagnostic challenges in inflammatory choroidal neovascular membranes. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2017, 25, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, L.S.; Batioğlu, F.; Atmaca, P. Evaluation of choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with fluorescein and indocyanine green videoangiography. Ophthalmologica 1996, 210, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsolis, A.I.; Killian, F.A.; Ladas, I.D.; Yannuzzi, L.A. Fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography concordance for choroidal neovascularisation in multifocal choroidtis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 94, 1506–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaide, R.F.; Goldberg, N.; Freund, K.B. Redefining multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis and punctate inner choroidopathy through multimodal imaging. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 2013, 33, 1315–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perentes, Y.; Van Tran, T.; Sickenberg, M.; Herbort, C.P. Subretinal neovascular membranes complicating uveitis: frequency, treatments, and visual outcome. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2005, 13, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, P.M.; Flower, R.W. Ten years’ experience with choroidal angiography using indocyanine green dye: a new routine examination or an epilogue? Doc. Ophthalmol. 1985, 60, 235–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.V.; Biswas, J.; Gunasekaran, D. Indocyanine green angiography in posterior uveitis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 61, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbort, C.P. Fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography for uveitis. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 16, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulzbacher, F.; Kiss, C.; Munk, M.; Deak, G.; Sacu, S.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U. Diagnostic evaluation of type 2 (classic) choroidal neovascularization: optical coherence tomography, indocyanine green angiography, and fluorescein angiography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 152, 799–806.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, R.B.; Rush, S.W. Evaluation of idiopathic choroidal neovascularization with indocyanine green angiography in patients undergoing bevacizumab therapy. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 642624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrejen, S.; Spaide, R.F. Optical coherence tomography: imaging of the choroid and beyond. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2013, 58, 387–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, R.; Priel, E.; Kramer, M. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomographic features of choroidal neovascular membranes in multifocal choroiditis and punctate inner choroidopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2015, 253, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, A.; Luiselli, C.; Esmaili, D.D.; Salvetti, P.; Cigada, M.; Miller, J.W.; Staurenghi, G. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography as an indicator of fluorescein angiography leakage from choroidal neovascularization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 5579–5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shang, Q.; Duan, J. Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography retinal biomarkers in choroidal neovascularization of multifocal choroiditis, myopic choroidal neovascularization, and idiopathic choroidal neovascularization. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Saurabh, K.; Bansal, A.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, A.K.; Paul, S.S. Inflammatory choroidal neovascularization in Indian eyes: etiology, clinical features, and outcomes to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 65, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, A.M.; Mackensen, F.; Arevalo, J.F.; Ziemssen, F.; Mahendradas, P.; Mehio-Sibai, A.; Hrisomalos, N.; Lai, T.Y.; Dodwell, D.; Chan, W.M.; Ness, T.; Banker, A.S.; Pai, S.A.; Berrocal, M.H.; Tohme, R.; Heiligenhaus, A.; Bashshur, Z.F.; Khairallah, M.; Salem, K.M.; Hrisomalos, F.N.; Wood, M.H.; Heriot, W.; Adan, A.; Kumar, A.; Lim, L.; Hall, A.; Becker, M. Intravitreal bevacizumab in inflammatory ocular neovascularization. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 146, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karti, O.; Ipek, S.C.; Ates, Y.; Saatci, A.O. Inflammatory Choroidal Neovascular Membranes in Patients With Noninfectious Uveitis: The Place of Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Therapy. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. 2020, 9, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mansour, A.M.; Arevalo, J.F.; Ziemssen, F.; et al. Long-term visual outcomes of intravitreal bevacizumab in inflammatory ocular neovascularization. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 148, 310–316.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrè, C.; Marchese, A.; Fogliato, G.; Miserocchi, E.; Modorati, G.M.; Sacconi, R.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Miere, A.; Amoroso, F.; Capuano, V.; Souied, E.; Bandello, F.; Querques, G. The "Sponge sign": A novel feature of inflammatory choroidal neovascularization. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, A.; Pichi, F.; Symes, R.; Zagora, S.; Agarwal, A.K.; Nguyen, P.; Erba, S.; Xhepa, A.; De Simone, L.; Cimino, L.; Gillies, M.C.; McCluskey, P.J. Twenty-four-month outcomes of inflammatory choroidal neovascularisation treated with intravitreal anti vascular endothelial growth factors: a comparison between two treatment regimens. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 104, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zuo, C.; et al. Clinical characteristics of inflammatory choroidal neovascularization in a Chinese population. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2016, 24, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, X.; Weng, S.; Mao, L.; Gong, Y.; Yu, S.; Xu, X. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography angiography findings in multifocal choroiditis with active lesions. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 169, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, S.; Chen, K.C.; Jung, J.J.; Balaratnasingam, C.; Ghadiali, Q.; Sorenson, J.; Rofagha, S.; Freund, K.B.; Yannuzzi, L.A. Optical coherence tomography angiography of chorioretinal lesions due to idiopathic multifocal choroiditis. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 2017, 37, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, H.Y.; Keane, P.A.; Ho, S.L.; Agrawal, R. Optical coherence tomography angiography of choroidal neovascularization associated with tuberculous serpiginous-like choroiditis. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2016, 24, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, K.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, K.; Gupta, V. OCTA Study Group. Detection Of Type 1 Choroidal Neovascular Membranes Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography In Tubercular Posterior Uveitis. Retina 2019, 39, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astroz, P.; Miere, A.; Mrejen, S.; Sekfali, R.; Souied, E.H.; Jung, C.; Nghiem-Buffet, S.; Cohen, S.Y. Optical coherence tomography angiography to distinguish choroidal neovascularization from macular inflammatory lesionns in multifocal choroiditis. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa) 2018, 38, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theelen, T.; Berendschot, T.T.J.M.; Hoyng, C.B.; Boon, C.J.F.; Klevering, B.J. Near-infrared reflectance imaging of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 247, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toju, R.; Iida, T.; Sekiryu, T.; Saito, M.; Maruko, I.; Kano, M. Near-infrared autofluorescence in patients with idiopathic submacular choroidal neovascularization. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 153, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samy, A.; Lightman, S.; Ismetova, F.; Talat, L.; Tomkins-Netzer, O. Role of autofluorescence in inflammatory/infective diseases of the retina and choroid. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 2024, 418193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of uveitis | Prevalence of iCNV, [references] |

|---|---|

| Non-infectious | |

| Multifocal choroiditis | 32–50% [4,5,6,7] |

| Punctate inner choroidopathy | 17-40% [1,4,8,9] |

| Serpiginous choroidopathy | 10-25% [4,10,11] |

| Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease | 9-15% [4,7,9,12] |

| Birdshot chorioretinitis | 5% [4,13] |

| Intermediate uveitis | single cases reported [14,15] |

| Behçet disease | very rare [4,16] |

| Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy | single cases reported [4,16,17,18] |

| Sympathetic ophthalmia | single cases reported [16,19] |

| Sarcoidosis | single cases reported [4,9,16] |

| Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome | single cases reported [4,20,21] |

| Infectious | |

| Histoplasmosis | 5-17.4% [4,9,16,22,23,24,25] |

| Candidiasis | rare; prevalence unknown [26,27,28] |

| Toxoplasmosis | 0.3-19% [29,30,31,32] |

| Toxocariasis | single cases reported [33,34,35] |

| Tuberculosis | single cases reported [36,37,38,39] |

| Rubella retinopathy | single cases reported [40,41,42,43] |

| West Nile virus | single cases reported [44,45,46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).