1. Introduction

Lateral elbow pain, affecting 1-3% of the population annually, is a common musculoskeletal disorder primarily associated with occupational activities and repetitive biomechanical stress on the joints, including the intricate support systems within the hand and wrist [

1,

2]. The resulting pain and sensory aberrations significantly contribute to the etiology of myofascial pain syndrome (MPS), particularly in muscles such as the m.

Extensor Carpi Radialis Brevis (ECRB), m.

Extensor Carpi Radialis Longus (ERDL), m.

Brachioradialis (BR), and m.

Extensor Digitorum Communis (EDC) [

3]. Myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) within these muscles or fascial structures are prevalent in MPS, characterized by palpable and taut hyperirritable regions linked to mechanical perturbations [

4]. Histological investigations reveal MTrPs as discernible muscular nociceptors capable of inciting spontaneous nociceptive responses [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The close relationship between MTrPs and sensory-motor connections in the spinal cord and possibly the brainstem suggests the generation of reflex circuits responsible for local spastic responses, referred pain, and motor dysfunction in affected individuals. This mechanism implies that allodynia, referred pain, and hyperalgesia in MPS patients result from peripheral sensitization by active muscle nociceptors [

9].

Persistent peripheral stimuli may induce changes in the central nervous system (CNS), transitioning from primary to secondary sensitization, as indicated by ionotropic ASIC receptors. ASIC-1 and ASIC-3 play distinct roles in primary and secondary hyperalgesia, contributing to the development of central sensitization (CS) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Sustained noxious stimulation of muscle nociceptors to the CNS is believed to activate neuro-immune responses in glial cells (GCs). While the mechanism by which MTrPs activate GCs lacks complete data, it is evident that it may be related to the prolonged release of proinflammatory substances in the MTrP environment, such as SP [

12], glutamate [

2], or CGRP [

6]. Epigenetic processes also play a crucial role in CS, encoding changes associated with neuronal functions during prolonged afferent discharge, as seen in MTrPs in the context of MTrPs [

9].

Conservative approaches like deep dry needling (DDN) have significantly impacted elbow MTrPs. DDN involves rhythmic transcutaneous needling of MTrPs to reduce pain and improve sensory-motor variables. Its therapeutic mechanism links to needle action at the endplate, causing increased discharges hypothetically reducing acetylcholine (Ach) reserves and lowering spontaneous electrical activity [

6].

Recent studies on animal models’ biopsies after DDN reveal increased neurotransmitters and proinflammatory substances, including endogenous opioids (endorphins). These inhibit pain transmission by activating enkephalinergic inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn, alongside reductions in bradykinin, substance P, CGRP, TNF, IL-1β, serotonin, and norepinephrine. The pH increase in the MTrP region deactivates ASIC ion channels and TRPV, potentially reducing mechanical hyperalgesia and limiting CS onset. At the central level, fibers can be indirectly stimulated through the release of inflammatory mediators, activating dorsal tracts of the spinal cord and supra-spinal centers involved in pain processing [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Post-DDN, late pain termed post-needling pain involves peripheral mechanisms, like the release of algogenic substances, fostering nociceptive tissue sensitization and promoting vasodilation, resulting in increased inflammation [

18]. Therapies such as ischemic compression (IC), cold spray with stretching (STR), and mirror visual feedback therapy (MFT) aim to treat these symptoms. IC, based on compression theory, enhances blood perfusion, oxygen, and nutrient supply, activating endogenous analgesic mechanisms, effective in relieving pain and accelerating healing after DDN. Cold spray acts physiologically, reducing skin temperature and blood flow, slowing post-needling edema. Although the stretching mechanism after needling is not precisely known, clinical studies show a rapid effect in decreasing pain intensity and increasing pain threshold to pressure afterward [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

MFT, activating mirror neurons during movement execution or observation, aids in reducing pain and restoring voluntary motor representations. Visual-motor feedback for patients with epicondylalgia aids in restoring sensorimotor coherence and voluntary motor performance. Despite potential, the combined effect of IC, STR, and MFT in managing post-needling pain requires further understanding. Clinical studies are warranted to justify its analgesic capacity, leading to the proposal of a pilot study in asymptomatic subjects to demonstrate short-term effects, assessing whether MFT reduces pain and mitigates sensorimotor disturbances post-needling. This study aimed to investigate the effect of adding Mirror Visual Feedback Therapy (MFT) after Dry Needling (DDN) on sensitivity and motor performance in patients diagnosed with Post-Needling pain from Myofascial Trigger Points (MTrPs) in the elbow.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

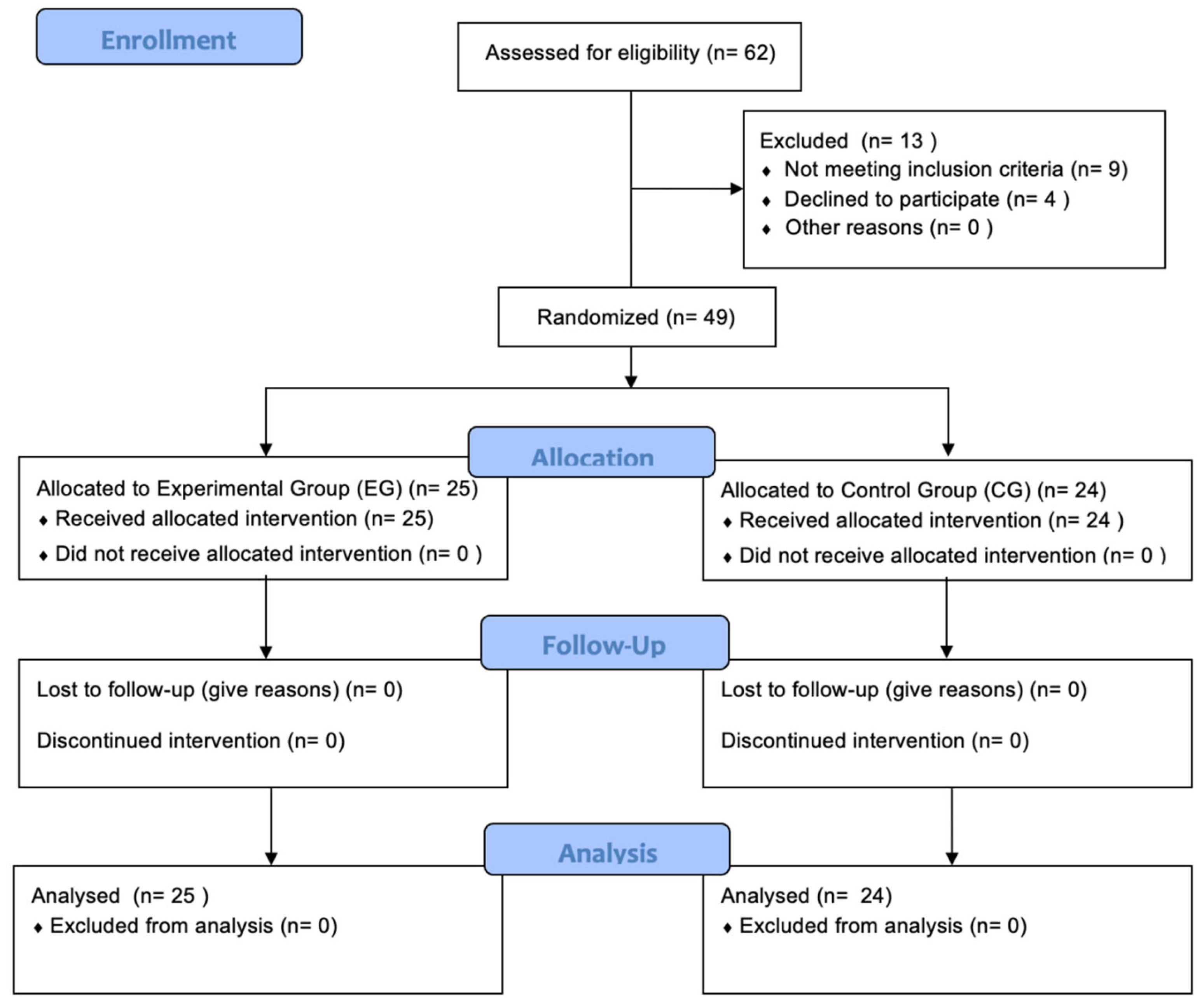

A randomized, controlled, two-arm pilot trial was conducted between February 1, 2023, and June 2, 2023, rigorously adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT, guidelines. The research meticulously followed ethical principles as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received formal approval from the hospital ethics committee (23/107-EC X TFM CEIm Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain). The study protocol was developed by researchers DSB, IRV, and AGM, and AK, JDR, PMR were responsible for administering written informed consent, intervention and assessments.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram. Flow-chart showing enrollment, allocation, follow-up and analysis throughout the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram. Flow-chart showing enrollment, allocation, follow-up and analysis throughout the study.

2.2. Participants

Participants were recruited through consecutive non-probabilistic sampling from February 20, 2023, to June 1, 2023. The recruitment strategy involved a combination of word-of-mouth referrals, social media outreach, bulletin board postings, and leveraging researcher networks. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) adults aged over 18 years, (2) experiencing lateral elbow pain caused by MTrPs for less than three months, without concurrent upper limb or spine pain, (3) no history of trauma, (4) not currently using relevant drugs, (5) no history of musculoskeletal surgeries, and (6) absence of toxic habits. All participants provided written consent to participate in the study.

2.3. Sample Size Determination

G*Power 3.1 software was utilized for the computation of sample size and power. The estimations were based on a clinically detectable minimum difference (MCID) in the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) of 30 mm for healthy subjects. Assuming a confidence interval (CI) of -36.4 to -23.6, a two-tailed test, alpha level of 0.05, and desired power of 80%, the estimated sample size for each arm was 23 individuals.

2.4. Randomized Allocation

Participants were allocated randomly to intervention groups through a number sequence generated by an independent researcher. The randomization process utilized a random sequence generator available at

http://www.random.org The concealment of allocation was appropriately maintained throughout the study.

2.5. Intervention

The intervention, conducted from February 1, 2023, to June 2, 2023, took place in a simulated hospital consultation room at the European University. The administration of the intervention was consistently supervised by a physiotherapist with over 10 years of clinical experience in applying DDN. Clear and uniform instructions regarding treatment efficacy were communicated to both groups. Subsequently, participants were categorized into two distinct treatment groups:

Experimental Group: Deep Dry Needling (DDN), Ischemic Compression, Cold Spray with Stretching + MFT.

The DDN intervention targeted the proximal third of the m. Brachioradialis (BR) with the patient seated, and the therapist positioned on the same side as the needle insertion. Dry needling involved a lateral-to-medial needle insertion direction toward the clinician’s finger, with a precision grip. In lean patients, precautions were taken to avoid accidental finger puncture by inserting the needle between the clinician’s fingers. DDN was performed with needle (AguPunt® Barcelona, Spain) seeking three local twitch responses. For subjects without such responses, 10 needle insertions and withdrawals at a frequency of 1 Hz were performed.

Following needling, ischemic compression (IC) was applied using a sphygmomanometer on the seated subject’s arm. Pressure was increased until ischemic pain appeared (approximately 200 mmHg), maintained for 90 seconds. This was combined with three applications of cold spray (Cryos Phyto Performance 400 ml) from origin to insertion, synchronized with m. Brachioradialis (BR) stretching consisting of passive sustained mobilization with elbow extension and forearm pronation for 10 seconds.

The intervention concluded with Mirror Therapy (MFT). The patient, seated with forearms resting on the bed, faced a 35 x 35 cm mirror (Mirror Box, EDGE Mobility System®, United States) covering the punctured side at a 45-degree angle for proper hand visualization. The punctured limb was positioned behind the mirror, out of the subject’s view. Any identifying objects (rings, bracelets, etc.) on the healthy limb were removed or covered. The MFT protocol consisted of two phases, each lasting 2 minutes. In the first phase, the therapist performed hand exercises while the subject observed the therapist’s hand reflected in the mirror. In the second phase, the subject executed hand opening and closing movements while observing their hand in the mirror. All movements were conducted at a frequency of 1 Hz with 40 repetitions.

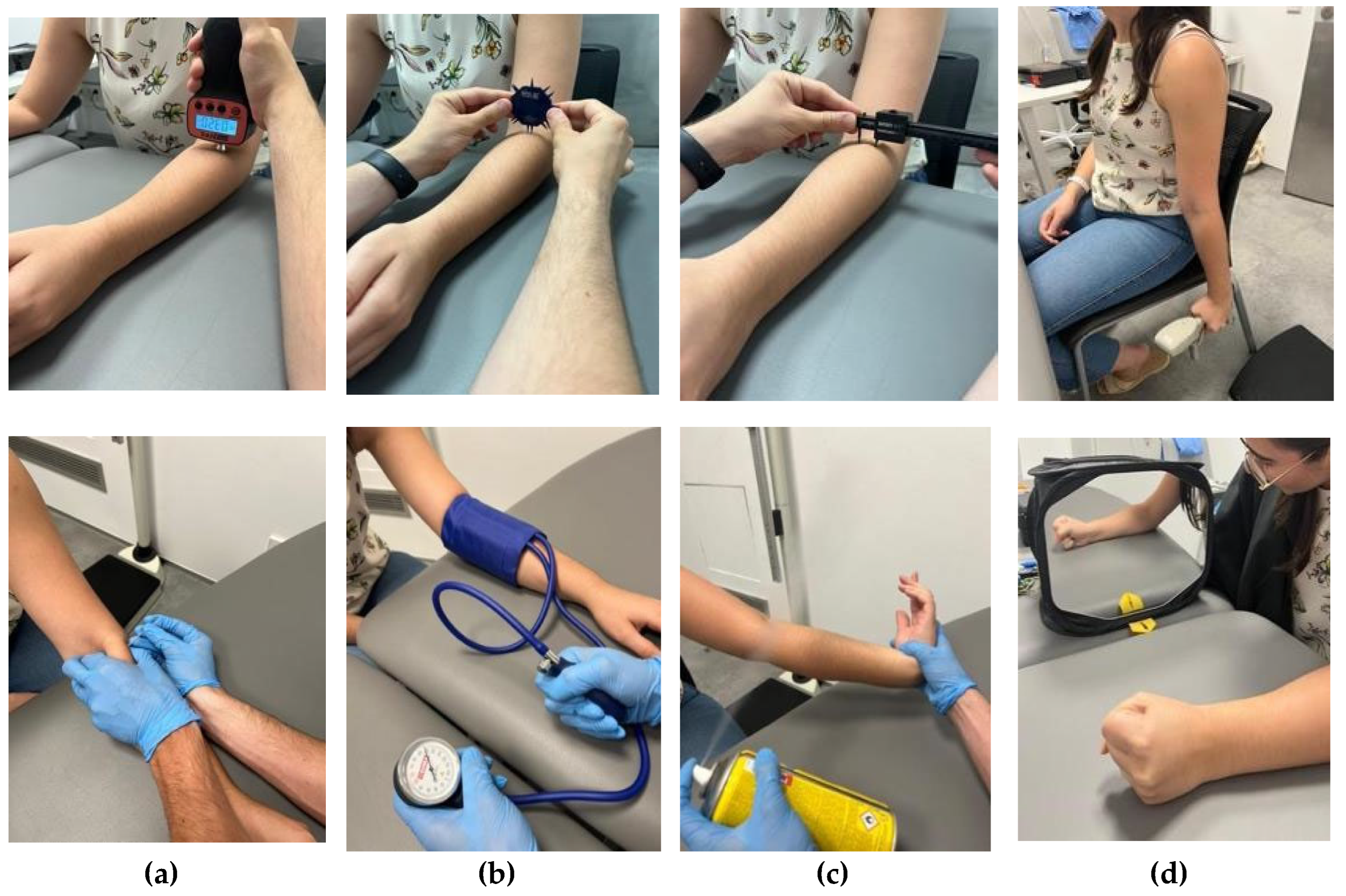

Figure 2.

Intervention. (a) Deep Dry Needling (DDN), (b) ischemic compression, (c) cold spray, stretching, and (d) Mirror Therapy (MFT).

Figure 2.

Intervention. (a) Deep Dry Needling (DDN), (b) ischemic compression, (c) cold spray, stretching, and (d) Mirror Therapy (MFT).

Control Group: Deep Dry Needling (DDN), Ischemic Compression, Cold Spray with Stretching.

Group 2 underwent deep dry needling (DDN), ischemic compression, cold spray, and stretching. Notably, this group did not undergo Mirror therapy (MFT).

2.6. Outcome Measures

The assessments encompassed pain intensity (VAS), pain pressure threshold (Wagner™ FPX Algometer 50, United States), two-point discrimination threshold (Baseline® 12-1480 skin caliper, 2-point discriminator, United States), and maximum hand grip strength (JAMAR® Hand Dynamometer J00105, United States). Measurements were documented both before commencing the intervention and within 5 minutes after concluding the treatment for pre- and post-intervention assessments.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed, encompassing measures of central tendency and dispersion parameters. To assess the normality of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was systematically applied to all study variables. Following the verification of data normality, intra-group variations were quantified utilizing the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, while inter-group differences were appraised through the Mann-Whitney U test. Subsequently, the calculation of effect size was performed using the Point-biserial correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were executed with the SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp.®, Armonk, NY, United States). Significance was established considering p-values below 0.05 as indicative of statistically significance.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Description of the Sample

A total of 49 participants (F=23, M=26) were selected, with an average age of 24.9 (10.9) in the Experimental group (n=25) and 24.9 (9.5) years in the Control group (n=24). The mean weight of participants was 75.8 (5.7) kg for the Experimental group and 73.3 (10.5) kg for the Control group. Regarding height, the intervention group had a slightly higher stature at 1.77 (0.06) m compared to the Control group at 1.72 (0.08) m. The body mass index (BMI) was very similar between the two groups, with values of 24.2 (1.7) and 24.7 (3.5) respectively. No statistically significant differences were identified between the two experiment groups. Further details can be found in

Table 1.

3.2. Description of Study Variables

In terms of pre- and post-needling pain intensity (VAS 0-10), Experimental group showed a mean of 1.416 and 1.064, respectively, with Control group showing values of 1.150 and 1.633. Pain pressure threshold (PPT) readings (Kg/cm

2) indicated Group 1 means of 1.485 (pre) and 1.77 (post), while Group 2 had means of 1.843 (pre) and 1.72 (post). Two-point discrimination thresholds (TPDT) in millimeters revealed pre-values of 12.3 (Group 1) and 12.7 (Group 2), with post-values of 13.5 and 13.7, respectively. Maximum hand grip strength (MHGS) displayed pre-values of 37.96 (Group 1) and 34.04 (Group 2), while post-values were 37.712 Kg/F and 34.867 Kg/F. Due to the presence of violations of the normality assumptions, a decision was made to employ non-parametric analysis for examining intra-group and inter-group differences in the study. More details in

Table 2.

3.3. Main Findings

3.3.1. Intra-Group Differences

Experimental group: Deep Dry Needling (DDN), Ischemic Compression, Cold Spray with Stretching + MFT

Post-needling pain intensity in participants of the experimental group (EG) showed statistically significant findings (MD = 0.400, SEM = 0.271, W = 137.00, p = 0.047) immediately after the addition MFT to DDN protocol. Similarly, the Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) demonstrated significant results (MD = 0.148 Kg/cm

2, SEM = 0.271, W = 262.00, p < 0.001). In contrast, Two-Point Discrimination Threshold (TPDT) (MD = -0.000 mm, SEM = 0.674, W = 121.00, p = 0.711) and Maximum Hand Grip Strength (MHGS) (MD = 0.200 Kg/F, SEM = 0.1999, W = 177.00, p = 0.224) did not exhibit statistically significant differences between initial and post-treatment measurements. Intra-group Differences of Experimental Group are detailed in

Table 3.

Control group: Deep Dry Needling (DDN), Ischemic Compression, Cold Spray with Stretching

Post-needling pain intensity in participants assigned to the control group (CG), as assessed by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS 0-10), did not reveal statistically significant differences (MD = -0.400, SEM = 0.247, W = 105.50, p = 0.643). Similarly, the Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) displayed non-significant results (MD = 0.029 Kg/cm

2, SEM = 0.073, W = 163.00, p = 0.648), as did the Two-Point Discrimination Threshold (TPDT) (MD = 1.999 mm, SEM = 1.047, W = 207.00, p = 0.983) following 5 minutes of the control intervention. Conversely, in the case of Maximum Hand Grip Strength (MHGS), there was a notable trend toward improvement in the CG, although without reaching statistical significance (MD = -0.799 Kg/F, SEM = 1.051, W = 83.00, p = 0.081). Intra-group Differences of Control Group are in details in

Table 4.

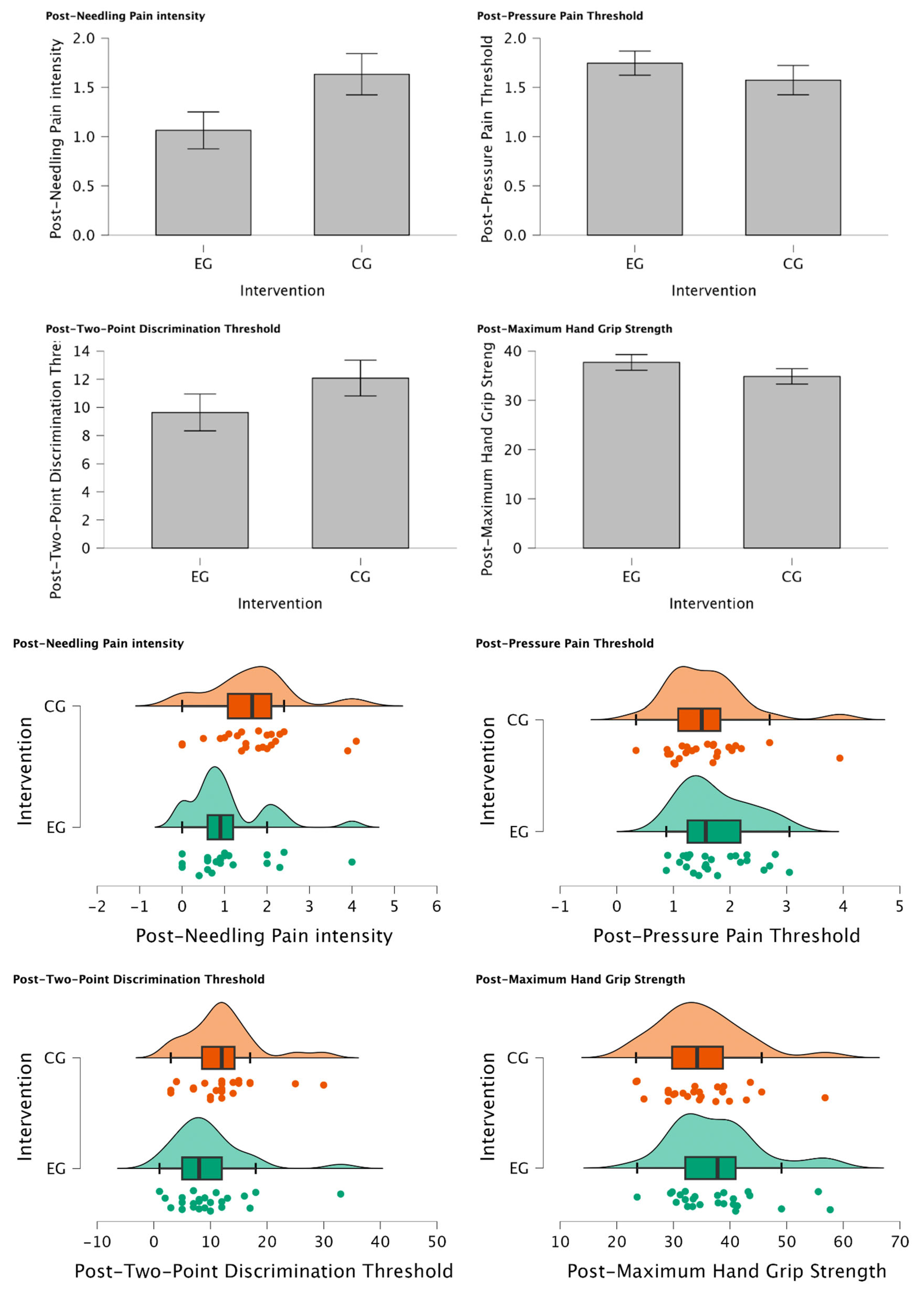

3.3.2. Inter-Group Differences

There was a statistically significant reduction in Post-Needling pain intensity (VAS 0-10) (U=188.00, p=0.034) suggesting a meaningful shift towards lower pain levels in individuals of EG treated with MFT with those who were not (CG) for managing post-needling pain. Furthermore, Post-TPDT (mm) exhibits a trend towards significance (U = 212.00, p = 0.079), signifying a notable group difference and a substantial reduction in values among participants assigned to the EG. In contrast, Post-PPT (Kg/cm

2) and Post-MHGS (Kg/F) show non-significant distinctions between groups (U = 354.00, p = 0.862; U = 365.0, p = 0.905, respectively). Intergroup Differences are explained in detail in

Table 5.

Figure 2a.

Intergroup Differences between Experimental vs Control Group after intervention. (*) Mann-Whitney U test was considered statistically different p=0.025. (a) Post-needling Pain intensity (VAS), (b) Post-PPT (Kg/cm2), (c) Post-TPDT (mm), (d) Post-MHGS (Kg/F).

Figure 2a.

Intergroup Differences between Experimental vs Control Group after intervention. (*) Mann-Whitney U test was considered statistically different p=0.025. (a) Post-needling Pain intensity (VAS), (b) Post-PPT (Kg/cm2), (c) Post-TPDT (mm), (d) Post-MHGS (Kg/F).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effect of adding Mirror Feedback Training (MFT) after Dry Needling (DDN) on sensitivity and motor performance in patients diagnosed with Post-Needling pain from Myofascial Trigger Points (MTrPs) in the elbow. Our findings align with previous studies that have demonstrated the efficacy of MFT in alleviating pain and improving motor performance in various musculoskeletal conditions [

32,

33] Specifically, the statistically significant increase in post-needling pain intensity within the experimental group (EG) echoes the positive outcomes reported in studies exploring MT applications in diverse pain-related contexts [

34,

35]

Moreover, the significant improvement observed in Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) following the combined MFT and DDN intervention aligns with the broader literature indicating the positive impact of MT on pain thresholds [

36,

37] Notably, the lack of significant changes in Two-Point Discrimination Threshold (TPDT) and Maximum Hand Grip Strength (MHGS) post-treatment suggests that the combined intervention might have selective effects on certain sensory and motor aspects, reflecting the nuanced nature of these interventions [

38,

39]

Contrastingly, the control group (CG) results, which did not reveal statistically significant differences in post-needling pain intensity and PPT, are consistent with the limited impact observed in similar control interventions reported in the literature [

40,

41] Interestingly, the observed trend toward improved Maximum Hand Grip Strength (MHGS) in the CG, although not statistically significant, underscores the need for further exploration of potential benefits arising from control interventions.

According to inter-group differences the results of our study unveil compelling insights into the impact of MFT on post-needling pain and related outcomes. A statistically significant reduction in Post-Needling pain intensity (VAS 0-10) among individuals in the experimental group (EG), compared to the control group (CG), suggests the potential efficacy of MFT in managing post-needling pain (U=188.00, p=0.034). This aligns with previous research that has highlighted the analgesic effects of MFT in various pain conditions [

42,

45].

Moreover, the trend towards significance in Post-Two-Point Discrimination Threshold (Post-TPDT) (mm) (U = 212.00, p = 0.079) further emphasizes the nuanced impact of MFT on sensory discrimination. The notable group difference and substantial reduction in TPDT values within the EG hint at potential neurosensory changes facilitated by MFT [46,47].

In contrast, the non-significant distinctions observed in Post-Pressure Pain Threshold (Post-PPT) (Kg/cm2) and Post-Maximum Hand Grip Strength (Post-MHGS) (Kg/F) between the EG and CG (U = 354.00, p = 0.862; U = 365.0, p = 0.905, respectively) indicate that the effects of MFT may be more specific to pain perception and sensory discrimination rather than overall pressure pain tolerance and muscle strength. These findings align with the notion that MFT may have selective effects on different aspects of sensorimotor function [48].

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations that could have influenced the results. Firstly, the sample is small and non-probabilistic, limiting result generalization. Secondly, the study focused on the acute effects of therapy, neglecting potential long-term effects. Thirdly, a control group without intervention was not included, which could have provided additional insights into intervention effects. Furthermore, considering that our MFT intervention lasts approximately 2 minutes, we are unaware of whether a more extended intervention could generate more significant changes.

5. Conclusion

MFT reduced post-needling pain and influenced on sensory perception with MTrPs in lateral elbow pain patients. The significant pain reduction and notable trend in sensory discrimination imply MFT's positive effects. Non-significant differences in pressure pain and grip strength suggest specificity in MFT outcomes. These findings emphasize the need for deeper mechanistic understanding and underscore MFT's potential as a complementary intervention in myofascial pain management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R.R. and M.D.S.R.; methodology, S.M.P.; software, I.M.P.; validation, J.L.A.P.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, D.S.B.; resources, I.R.V.; data curation, A.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.R., A.K., P.M.R., writing—review and editing, S.M.P.; visualization, I.M.P., M.D.S.R.; supervision, J.L.A.P; project administration, J.L.A.P.; funding acquisition, J.L.A.P.

Funding

The research received financial supported from the European University of the Canary Islands, located at C/Inocencio García 1, 38300 La Orotava, Tenerife, 38300 Canary Islands, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain (23/107-EC X TFM, 07/03/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on demand.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A., Pecos-Martin, D., Rodríguez-Fernández, et al. Ischemic Compression After Dry Needling of a Latent Myofascial Trigger Point Reduces Post-Needling Soreness Intensity and Duration. PM&R. 2015;7(10):1026-1034. [CrossRef]

- Dommerholt, J. Dry needling - peripheral and central considerations. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19(4):223-7. [CrossRef]

- Shushkevich, Y., Kalichman, L. Myofascial pain in lateral epicondylalgia: a review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013; (4):434-9. [CrossRef]

- Borg-Stein, J., Iaccarino, M.A. Myofascial pain syndrome treatments. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(2):357-74. [CrossRef]

- Ivan Urits, Karina Charipova, Kyle Gress, Amanda L. Schaaf, Soham Gupta et.al. Treatment and management of myofascial pain syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34(3):427-448. [CrossRef]

- Cagnie, B., Dewitte, V., Barbe, T., et al. Physiologic effects of dry needling. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(8):348. [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.Z., Simons, D.G. Pathophysiologic and electrophysiologic mechanisms of myofascial trigger points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(7):863-72. [CrossRef]

- Chou, L.W., Hsieh, Y.L., Kuan, T.S., Hong, C.Z. Needling therapy for myofascial pain: recommended technique with multiple rapid needle insertions. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2014;4(2):13. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., Dommerholt, J. Myofascial trigger points: peripheral or central phenomenon? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(1):395. [CrossRef]

- Gerard A. Malanga, Ning Yan & Jill Stark. Mechanisms and efficacy of heat and cold therapies for musculoskeletal injury: Postgrad Med. 2015;127(1):57-65. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., Li, J., Tian, Y., et al. Effect of ischemic compression on myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022;30(34):2-11. [CrossRef]

- Siegfried Mense. How Do Muscle Lesions such as Latent and Active Trigger Points Influence Central Nociceptive Neurons? J. Musculoskelet. Pain. 2010;18(4):348-353. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A., Mayoral Del Moral, O., Gerwin, R.D., Fernández-Carnero, J. Post-needling soreness after myofascial trigger point dry needling: Current status and future research. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(4):941-946. [CrossRef]

- Simons, D.G. Symptomatology and clinical pathophysiology of myofascial pain. Schmerz. 1991;5(1):29-37. [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.P., Thaker, N., Heimur, J., Aredo, J.V., Sikdar, S., et al. Myofascial Trigger Points Then and Now: A Historical and Scientific Perspective. PM&R. 2015;7(7):746-761. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C., Nijs, J. Trigger point dry needling for the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome: current perspectives within a pain neuroscience paradigm. J Pain Res. 2019; 12:1899-1911. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A., Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.L., García-Muro, F., et al. Effects of spray and stretch on post-needling soreness and sensitivity after dry needling of a latent myofascial trigger point. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(10):1925-1932. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., Li, J., Tian, Y., Lu, X. Effect of ischemic compression on myofascial pain syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2022;30(1):34. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A., Mayoral Del Moral, O., Gerwin, R.D., Fernández-Carnero, J. Post-needling soreness after myofascial trigger point dry needling: Current status and future research. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(4):941-946. [CrossRef]

- Shushkevich, Yaniv et al. Myofascial pain in lateral epicondylalgia: A review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013;17(4):434-439. [CrossRef]

- Lenoir H, Mares O, Carlier Y. Management of lateral epicondylitis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105(8):241-246. [CrossRef]

- Crosby PM, Dellon AL. Comparison of two-point discrimination testing devices. Microsurgery. 1989;10(2):134-7. [CrossRef]

- Deconinck FJ, Smorenburg AR, Benham A, Ledebt A, Feltham MG, et al. Reflections on mirror therapy: a systematic review of the effect of mirror visual feedback on the brain. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(4):349-61. [CrossRef]

- Yueh-Hsia Chen, Tiing-Yee Siow, Ju-Yu Wang et al. Greater Cortical Activation and Motor Recovery Following Mirror Therapy Immediately after Peripheral Nerve Repair of the Forearm. Neuroscience. 2022;15(481):123-133. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto M, Muraoka T, Mizuguchi N, Kanosue K. Combining observation and imagery of an action enhances human corticospinal excitability. Neurosci Res. 2009;65(1):23-7. [CrossRef]

- Ol, H., Van Heng, Y., Danielsson, L. & Husum, H. Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: a randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia. Scand. J. Pain. 2018;18(4):603-610. [CrossRef]

- Heyes C, Catmur C. What Happened to Mirror Neurons? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022;17(1):153-168. [CrossRef]

- Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE, Crosby PM. Reliability of two-point discrimination measurements. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12(51):693-6. [CrossRef]

- Brodie EE, Whyte A, Niven CA. Analgesia through the looking glass? A randomized controlled trial investigating the effect of viewing a ‘virtual’ limb upon phantom limb pain, sensation, and movement. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(4):428–436. [CrossRef]

- Chan BL, Witt R, Charrow AP, Magee A, Howard R, Pasquina PF, et al. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):220-6. [CrossRef]

- Thieme H, Morkisch N, Rietz C, Dohle C, Borgetto B, Theilig S, et al. Mirror therapy for patients with severe arm paresis after stroke—a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(7):614-25. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Lin L, Xiong Q, Zeng W, Yu L, Hou Y. Effect of mirror therapy on recovery of stroke survivors: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Neurosci Lett. 2018; 662:292-300. [CrossRef]

- Karthikbabu S, Nayak A, Suresh M. Mirror therapy enhances motor performance in the paretic upper limb after stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(9):1839-47. [CrossRef]

- Savva C, Giakas G, Efstathiou M. The effect of mirror therapy on lower extremity muscle strength and ambulation in stroke patients. J Novel Physiother Phys Rehabil. 2020;7(1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Hall C, Hu YC, Nahm FS. Mirror therapy for improving motor function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017(11):CD008449. [CrossRef]

- Sim YJ, Kim HJ, Ku J. Effect of virtual reality on cognition in stroke patients. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015;39(4):585-91. [CrossRef]

- Alharbi HA, Eng JJ, Lam T. The effect of visual feedback on power output during circuit-based power training in individuals with chronic stroke. Physiother Can. 2017;69(1):45-53. [CrossRef]

- Lewis GN, Polus B, Rome K. The efficacy of dry needling and procaine in the treatment of myofascial pain in the jaw muscles. J Man Manip Ther. 2019;27(4):220-8.

- Blanton S, Wolf SL, Annetta M, Winstein C. Effect of intensive compared with conventional physical therapy on upper-extremity motor recovery after stroke: the ICARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;313(6):569-78. [CrossRef]

- Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery for pathologic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2006 Dec 26;67(12):2129-34. [CrossRef]

- Cacchio A, De Blasis E, De Blasis V, Santilli V, Spacca G. Mirror therapy in complex regional pain syndrome type 1 of the upper limb in stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009 Oct;23(8):792-9. [CrossRef]

- Ruf SP, Hetterich L, Mazurak N, Rometsch C, Jurjut AM, Ott S, Herrmann-Werner A, Zipfel S, Stengel A. Mirror Therapy in Patients with Somatoform Pain Disorders-A Pilot Study. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023 May 20;13(5):432. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Samuelkamaleshkumar S, Reethajanetsureka S, Pauljebaraj P, Benshamir B, Padankatti SM, David JA. Mirror therapy enhances motor performance in the paretic upper limb after stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Nov;95(11):2000-5. [CrossRef]

- Bowering KJ, O'Connell NE, Tabor A, Catley MJ, Leake HB, Moseley GL, Stanton TR. The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2013 Jan;14(1):3-13. [CrossRef]

- Thieme H, Morkisch N, Rietz C, Dohle C, Borgetto B. The Efficacy of Movement Representation Techniques for Treatment of Limb Pain--A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):167-80. [CrossRef]

- Al Shrbaji T, Bou-Assaf M, Andias R, Silva AG. A single session of action observation therapy versus observing a natural landscape in adults with chronic neck pain - a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023 Dec 19;24(1):983. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).