1. Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) aged between 15 and 24 are at a higher risk of being exposed to HIV infection than older women and their male peers. This is particularly true for those who sell sex, who are highly vulnerable to HIV transmission [

1,

2,

3]. The precarious circumstances of sex work often expose vulnerable populations, particularly young female sex workers (YFSW), to a variety of challenges that increase their risk of contracting HIV. Vulnerability of female sex workers (FSW) to HIV infection is a major public health concern, especially among AGYW in diverse socio-cultural settings [

4]. Economic pressures, customer retention problems, and forced sex are just a few of the factors that YFSWs must navigate, which make engaging in risky sexual practices more likely [

5]. Studies have shown that compared to older FSWs, YFSWs negotiate condom use less, are more likely to have sex with older partners, and are less likely to benefit from HIV prevention and other health services due to their fear of stigmatization and discrimination by medical staff [

6,

7,

8,

9]. In addition, during forced sex, preventive measures such as condom use may not be employed. Sarkar et al. [

10] found that HIV infection among YFSWs was 2.4 times higher than in older FSWs, as YFSWs' professional immaturity may lead to more unprotected sex [

10]. A Chinese study by Su et al. [

11] confirmed that AGYW new to sex work are more likely to be victims of physical and sexual abuse, which can double or quadruple HIV prevalences. The stigma surrounding AIDS and sexuality as well as ignorance of the use of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after forced sex add a layer of complexity to understanding the risk factors involved in HIV transmission [

12]. These situations highlight the increased risk of HIV infection among YFSWs.

Despite the well-known risks associated with YFSWs, it is important to understand the high-risk sexual behaviours associated with HIV transmission to develop effective interventions and policies aimed at reducing the spread of HIV and improving the health and well-being of FSWs.

The HIV and AIDS epidemic in the DRC is considered a mixed health public problem due to its varying impact on the different provinces. According to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)’s HIV and AIDS programme’s 2021 estimate, 0.7% of adults aged 15–49 are HIV-positive [

13]. HIV prevalence rates vary significantly among provinces, with the highest rates found in Maniema (4%), Province Orientale (2.3%), Kasaï Oriental (1.8%), Kinshasa (1.6%), and Haut-Katanga (1.5%) [

14]. Compared to the general population, FSWs consistently have a higher prevalence of HIV. For example, a study conducted in Lubumbashi found that 8.2% of FSWs were HIV-positive [

15]. If not properly managed, the HIV prevalence among FSWs could increase among the general population due to interactions with FSWs. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct an in-depth investigation into the prevalence and determinants of HIV infection among YFSWs in the bustling city of Lubumbashi in southeastern DRC. This study aims to unravel the complexities surrounding HIV transmission among this demographic group by determining the HIV prevalence and identifying high-risk sexual practices associated with HIV infection among YFSWs in Lubumbashi. The central aim of this study is to gain a comprehensive understanding of the HIV/AIDS situation among this specific population, which is considered to be one of the most vulnerable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

Lubumbashi, the capital of the province of Haut-Katanga, is the second largest city in the DRC and covers an area of 747 km². It is a major economic center due to its leading role in the mining industry, particularly copper and cobalt. Lubumbashi has a diverse population, including various ethnic groups and communities, but faces challenges such as urbanization and infrastructure problems, as well as economic and social disparities. According to estimates for 2024, Lubumbashi's population will reach 2,933,962. Rapid population growth may exacerbate urbanization and attract people to economic centers such as Lubumbashi for employment opportunities and other advantages of urban living [

16]. The town's centrality in the mining industry attracts a migrant population from other provinces linked to extractive activities, creating a demand for sexual services. Despite the benefits of the mining industry, persistent economic inequality may push some women into sex work as a means of subsistence. The rapid urbanization of Lubumbashi is also a significant factor in attracting people in search of economic opportunities.

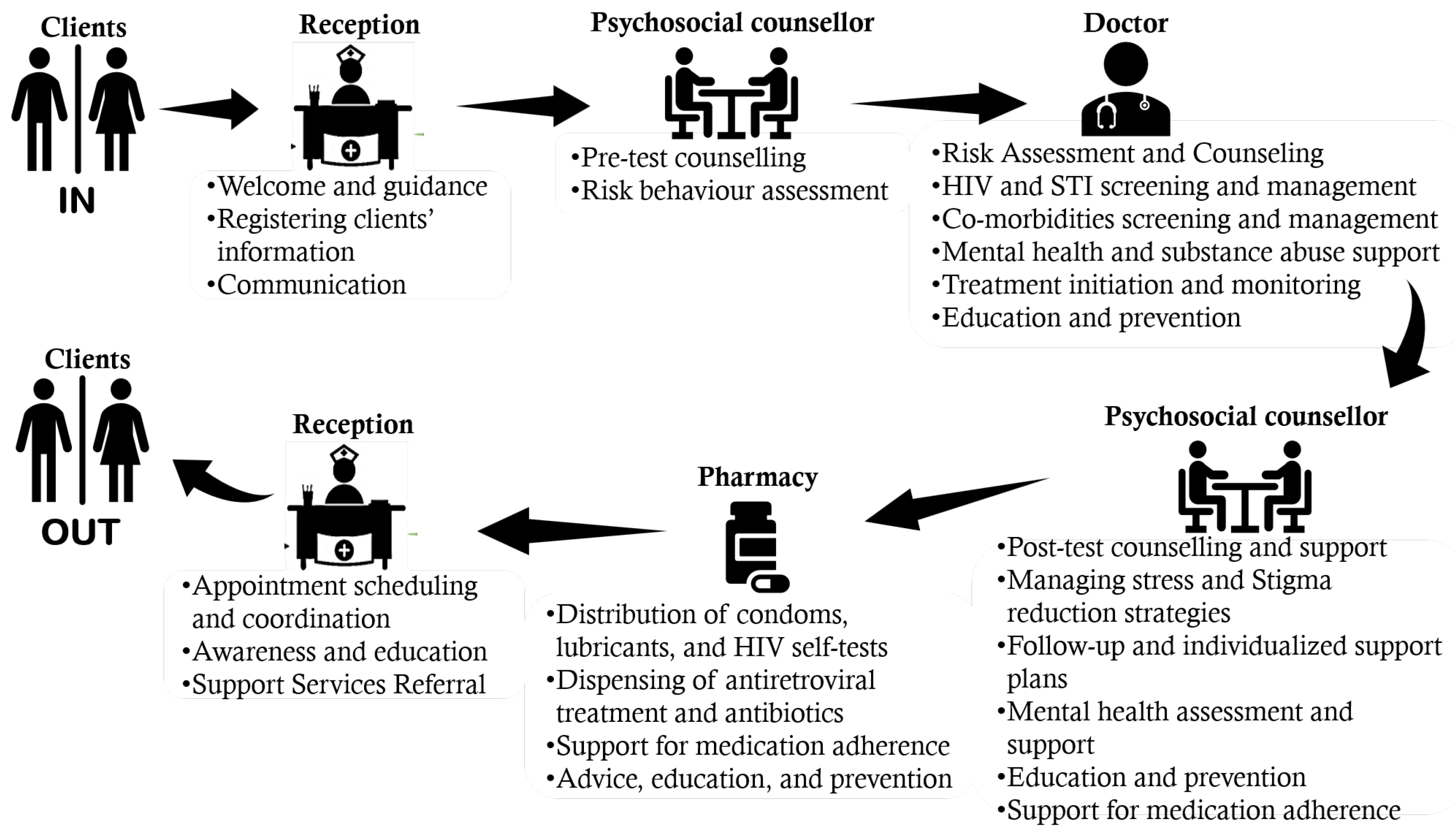

The rapid urbanization and increasing population in Lubumbashi have led to a rise in the demand for sexual services, which has resulted in the emergence of sex workers. Unfortunately, sex workers in Lubumbashi often face marginalization, which affects their access to healthcare services and their safety. In response to these challenges, two health facilities were established in 2016 in the municipalities of Katuba and Kampemba dedicated solely to the care of HIV infection and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among key populations (sex workers, injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, and transgender people). This study took place in one of these health facilities, which is located in the municipality of Katuba. In this HIV/STI screening and treatment center for key populations, the client circuit is designed to meet the needs of these populations. The healthcare services provided are adapted and sensitive to the particular needs of key populations, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Study Design and Population

A cross-sectional study was conducted using an exhaustive sample of all FSWs aged between 18 and 24 who visited the HIV/STI screening and treatment center of the Katuba municipality in Lubumbashi between April 2016 and December 2017. Peer educators (i.e. current or former FSWs working closely with this center) sensitized FSWs from their places of sex work and invited them to visit the center for free health care. The study focused on 572 participants who identified as FSWs and met the inclusion criteria of being born biologically female, aged between 18 and 24, and having engaged in sexual activity in exchange for money or gifts within the last six months.

According to the definition in this study, any woman who reports having exchanged regular or occasional sexual acts (such as oral, vaginal, and/or anal intercourse) with anyone other than her established partner in the last six months for something of value (money and material goods) that would not have been extended to them by their sexual partners is considered a FSW [

5,

17]. In the DRC, the legal age for consensual sex is 18 years and over; thus, women under the age of 25 who regard themselves as involved in the sex work are classified as YFSW. They may or may not identify as FSW [

4].

The clinical psychologists and doctors working at the center used structured questionnaires to conduct face-to-face interviews in French or Kiswahili. All the rooms in which the biological samples were collected and the face-to-face interviews were conducted offered a degree of privacy to the interviewees. All HIV testing were performed in the doctor’s office after obtaining written informed consent from FSW and were accompanied by pre- and post-test counselling. HIV testing followed the national HIV testing protocol recommending the use of an Alere Determine™ HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo rapid test; if this test is positive, confirmation with a Uni-Gold™ (Trinity Biotech) or VIKIA® HIV1/2 (bioMerieux) rapid test should be done as a second-line test. Individuals reacting to both tests were classified as HIV-positive. For FSWs who tested positive for HIV, antiretroviral treatment was immediately initiated in accordance with the DRC’s national HIV and AIDS management guidelines. All FSWs also received health education and free condoms as shown in

Figure 1.

2.3. Study Variables

The dependent variable was HIV status (negative or positive). We used the medical forms and the center’s registers to collect the following independent variables: the participant’s age, the number of years she had been selling sex, the regular consumption of alcohol before sex, the average number of sexual encounters per day, the number of clients per week (paying sexual partners during the previous week), the fact of having had an STI during the previous 12 months (“No” or “Yes”), systematic condom use by the client in the last 12 months (“No” or “Yes”), anal sex in the last 12 months (“No” or “Yes”), forced sex in the last 12 months (“No” or “Yes”).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data collected were recorded in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using STATA version 16. We used descriptive statistics to calculate the proportion and mean (± standard deviation). For bivariate analysis, we used the Chi-squared test to check the association between the independent variables and the dependent variable, which was HIV status. To account for possible confounding factors, we entered all independent variables into the final model using multiple logistic regression by the block entry method. We calculated adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and considered p-values <0.05 statistically significant.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Lubumbashi and adhered to the guidelines for the ethical review of research involving human subjects in the DRC as well as the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments (World Medical Association, 2001). As the study involved a retrospective secondary analysis of existing data collected as part of routine care and there was no contact with YFSWs, individual informed consent was not required, in accordance with the guidelines for the Ethical Review of Research Involving Human Subjects in the DRC. Patient identifiers were not collected to protect the anonymity and confidentiality of all participants.

3. Results

A total of 572 YFSWs were included in the study, of whom 30.8% were aged between 18 and 19, 26.7% between 20 and 21 and 42.5% between 22 and 24. The mean age of the YFSWs was 20.8 ± 2.1 years. The mean duration of sex work was 2.0 ± 1.6 years, and 54.9% of YFSWs had been selling sex for one year. The majority (76.1%) of YFSWs stated that they regularly consumed alcohol before sex and 78.1% admitted having suffered from an STI in the last 12 months. The mean number of sexual encounters per day was 6.4 ± 3.3 and 50.5% of YFSWs reported having more than 5 sexual encounters per day. The majority (83.7%) of YFSWs had ≥3 paying clients per week. Over the last 12 months, the proportions of YFSWs who reported that they did not systematically use condoms, that they had had anal sex and that they had forced sex were 21.7%, 4.7%, and 5.1% respectively (

Table 1).

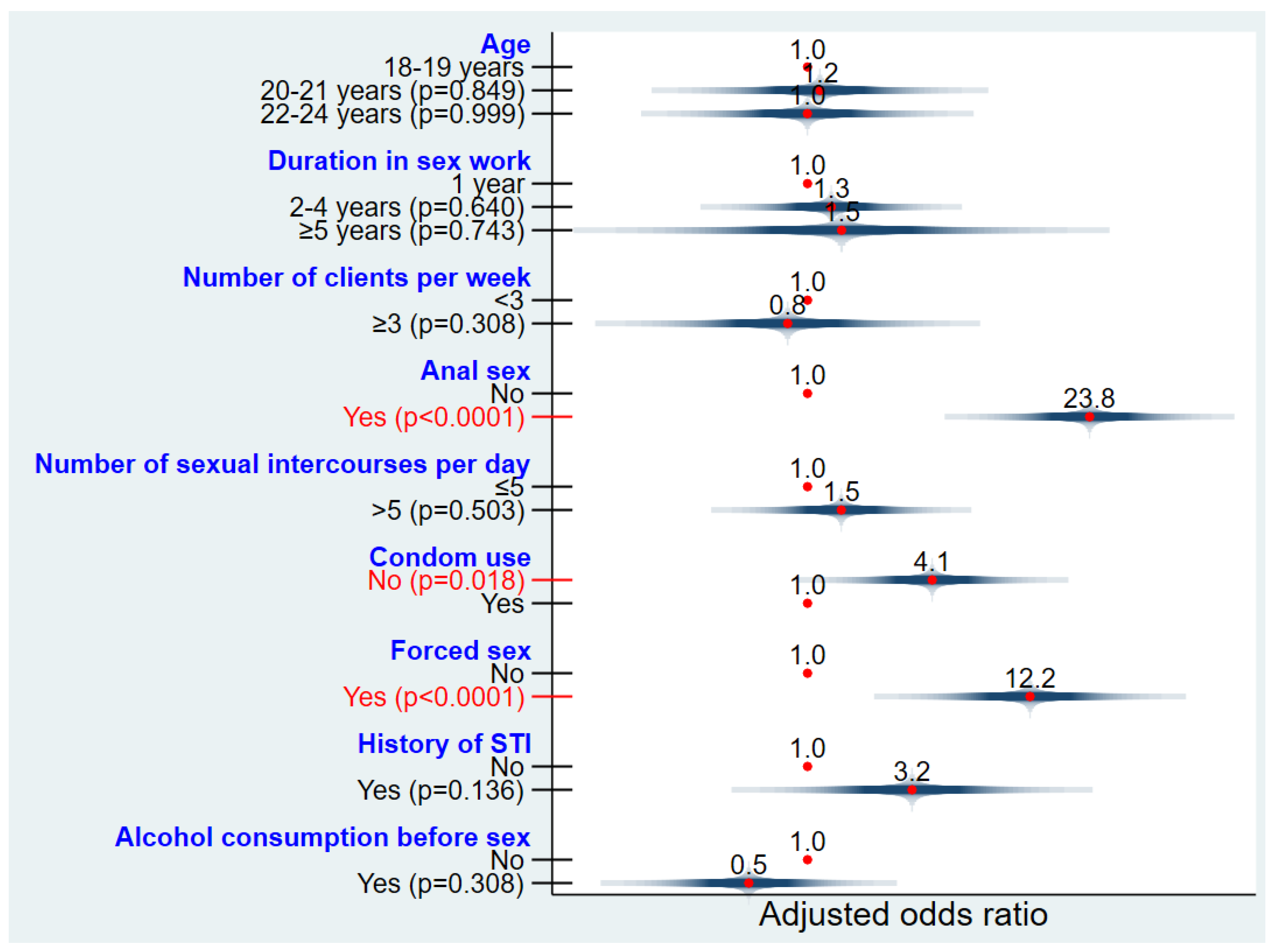

HIV prevalence among YFSW was 3.3% (19/572) with a confidence interval of 2.1% to 5.1%. The mean age of HIV-negative YFSWs was 20.8 ± 2.1 years, while that of HIV-positive YFSWs was 21.2 ± 2.1 years. HIV prevalence was not statistically associated with age, duration of sex work or alcohol consumption before sex (p=1.000). YFSWs who had had an STI in the last 12 months were more likely to be diagnosed as HIV-positive than those who had not had an STI, but the difference in HIV prevalence between these two groups was not statistically significant (3.6% versus 2.4%; p=0.777) (table 1).

HIV prevalence among YFSWs who had ≥3 paying clients per week was higher than among YFSWs who had <3 paying clients per week; but with no statistically significant difference (3.6 versus 2.1; p=0.752). As for the number of sexual encounters per day, YFSWs who had ≤5 sexual encounters were less HIV-positive than those who had more than 5 sexual encounters, but there was no significant statistical difference (3.2 vs 3.5; p=1.000) (table 1). We observed that the odds of being diagnosed with HIV among YFSWs who did not use condoms systematically were significantly higher than among YFSWs who reported using condoms systematically (adjusted OR=4.1; 95% CI: 1.3 - 13.0; p=0.018). YFSWs who had forced sex were more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than those who had not (adjusted OR=12.2; 95% CI: 3.2 - 46.4; p<0.0001). Anal sex was more susceptible to HIV diagnoses in YFSWs (adjusted OR=23.8; 95% CI: 6.9 - 82.4; p<0.0001) (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In Lubumbashi, the second largest city in the DRC, it is crucial to understand the prevalence and determinants of HIV among YFSWs in order to develop targeted interventions. This study provides insight into the complex dynamics surrounding HIV risk factors within the city’s sex work industry, taking into account the nuanced factors that influence HIV transmission. By unraveling the risky sexual behaviors that shape the HIV landscape within this vulnerable demographic group, this study adds to the existing knowledge base. The World Health Organization categorizes the vulnerability of the global population to HIV/AIDS into different groups, and FSWs are considered a key population susceptible to high HIV infection rates [

17].

The prevalence of HIV among YFSWs is a major concern globally, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. This study, for the first time, determines the prevalence and determinants of HIV infection among YFSWs (<25 years old) in the DRC, reporting a prevalence of 3.3%. This prevalence is higher than that observed in the general Congolese population, which stands at 0.7% [

13]. Contrastingly, in a Zimbabwean study by Hensen et al. [

4], HIV prevalence among 2387 YFSWs was significantly higher at 23.6%. These results raise questions about the regional determinants and socio-economic factors that could contribute to these variations, such as differences in access to health services, sex education, condom availability, and other socio-economic variables including limited access to education and lack of employment alternatives that could influence HIV prevalence rates among YFSWs in different regions.

This study highlights significant variations in HIV prevalence rates among YFSWs across different age groups. YFSWs aged 18 to 19 exhibit a rate of 2.3%, while those aged 20 to 21 have a rate of 3.3%, and the rate increases to 4.1% for those aged 22 to 24. These statistics reveal a worrying trend of increasing HIV prevalence as YFSWs age, suggesting the need for targeted interventions tailored to each age group. Similar findings were also reported in the Zimbabwean study, which observed a correlation between age and HIV prevalence among YFSWs (18-24 years), indicating that HIV prevalence increases as FSWs get older [

4]. Several factors contribute to this trend, including prolonged exposure to risky sexual behaviors, unsafe sexual practices, social stigma, and limited access to health services. YFSWs who have been working for several years also face increased challenges due to growing stigmatization and persistent social vulnerability, coupled with difficult socio-economic situations and the lack of a social safety net. The Ghanaian study by Guure et al. [

5] found variations in HIV prevalence rates between the two age groups studied, with the under-20s having a higher rate of 4.22% and the 20-24s having a slightly lower rate of 2.93%. These differences highlight the need for a comprehensive analysis of the socio-cultural contexts, risky sexual practices, and HIV prevention interventions specific to each region.

The results of the study indicate that YFSWs engaged in anal sex face a significantly elevated risk of being HIV-positive, with an aOR of 23.8 (95% CI: 6.9 - 82.4; p<0.0001). This underscores a robust association between anal sex and HIV prevalence within this specific population. According to current knowledge, the risk of HIV transmission through anal sex is markedly higher compared to penile-vaginal intercourse, with studies suggesting that it is approximately 16-18 times greater [

18]. Several mechanisms may elucidate this observed correlation. Anal intercourse can compromise the natural barriers to HIV transmission and cause microtrauma to the rectal mucosa. Notably, rectal tissue is more susceptible to injury than vaginal mucosa, creating a more accessible entry point for HIV and escalating the risk of infection [

19,

20]. Additionally, the rectum is rich in immune cells that can be susceptible to HIV infection [

20].

YFSWs who are subjected to forced sex can face significant barriers when it comes to condom use. Physical or psychological coercion during sex can compromise the ability to negotiate condom use, thereby increasing the risk of HIV transmission. The correlation between forced sex and HIV infection among YFSWs raises major public health concerns. According to the present study, forced sex is significantly associated with an increased risk of HIV infection, with an aOR of 12.2 (95% CI: 3.2 - 46.4; p<0.0001). This finding is similar to that of Sarkar et al. [

21] who found that sexual violence was significantly associated with HIV infection in FSWs (aOR =2.3; 95% CI: 1.2-4.5). Forced sex can expose women to high-risk sexual partners, such as people living with HIV who do not know their HIV status. This increased exposure to infected partners naturally increases the risk of HIV transmission. In addition, AGYW who have been victims of forced sex may develop significant psychological trauma, which may lead them to adopt risky behaviors such as substance use, engagement in unprotected sex, and reduced compliance with HIV prevention measures. A Russian study reported a strong association between drug use, unprotected anal sex and forced sex among FSWs [

22]. According to Shannon and Csete, the isolation and marginalization experienced by FSWs makes it difficult for them to negotiate safer sex practices, thereby increasing their risk for HIV infection [

23]. The partial or total absence of condom use during sex considerably increases their vulnerability to HIV infection. Previous studies have shown that regular condom use significantly reduces the risk of HIV/STIs transmission among FSWs [

24,

25]. When unprotected sex becomes the norm, the probability of contracting HIV increases considerably, as suggested by the analysis of our results with an adjusted odds ratio of 4.1 (95% CI: 1.3 - 13.0; p=0.018). According to Onyango et al. [

26], condom non-use during sex among Ghanaian YFSWs was influenced by higher payments, drug and/or alcohol use, fear of violence sexual, and police harassment.

YFSWs’ motivation to engage in risky sexual behavior can be influenced by a variety of complex and interconnected factors, including economic, social, psychological, and cultural aspects. Economic and financial pressures may push YFSWs to provide specific sexual services, such as not using condoms and/or anal sex, which may enable them to receive higher remuneration for such services, thus encouraging them to respond. Fear of losing clients or being rejected may also deter them from refusing specific requests [

5]. The lack of adequate sex education and access to accurate information on risky sexual practices can lead to an underestimation of the dangers of sex. Stigmatization and marginalization can also lead YFSWs to adopt risky sexual behaviors in order to meet clients’ expectations [

23]. The pursuit of acceptance and inclusion can drive some YFSWs to adopt more risky sexual practices. Psychosocial factors, such as trauma, violence, or poor past treatment, can also influence YFSWs’ sexual choices. The interconnection between the three high-risk sexual practices – unprotected sex, anal sex, and forced sex – creates a complex and interdependent dynamic that amplifies vulnerability and the risk of HIV transmission. This interconnection between these risky sexual behaviors generates a spiral of risk and vulnerability, with each practice reinforcing the others. Anal sex can lead to opportunistic decisions not to use a condom and is often associated with higher financial compensation [

27]. Forced sex, by creating situations where control over condom use is limited, increases the risk of HIV transmission and establishes a climate of persistent vulnerability. To break this spiral, targeted interventions such as HIV prevention programs, psychological support services, and awareness-raising campaigns are crucial. A comprehensive approach aimed at empowering YFSWs, promoting systematic condom use, and combating sexual violence is essential to reverse this damaging dynamic and improve the overall sexual health of this vulnerable population.

This cross-sectional analytical study examines risky sexual practices among YFSWs in Lubumbashi. However, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. The study's cross-sectional design prohibits the establishment of causal relationships between high-risk sexual practices and HIV infection, and recall bias may exist due to the difficulty participants have in accurately remembering their past sexual practices. Furthermore, the sample's representativeness may be limited, restricting the generalizability of the results to all Congolese YFSWs. Lastly, socially desirable responses could potentially affect the validity of the data collected.

Despite the limitations mentioned, this study has several strengths. It offers an insight into the actual sexual practices of YFSWs at a given point in time, which is essential in comprehending the current situation. The statistical analyses used establish significant associations between high-risk sexual practices and HIV infection, thereby guiding future research and public health interventions. Moreover, the ease of data collection in a cross-sectional study can contribute to a rapid response to urgent public health needs. The results of this study provide a foundation for more in-depth investigations and targeted interventions aimed at reducing risky sexual practices and improving the sexual health of YFSWs in Lubumbashi.

5. Conclusions

The results highlight a complex interconnection between risky sexual practices, including unprotected sex, anal sex, and forced sex, contributing to higher HIV prevalence in YFSWs. It is clear that HIV prevalence is influenced by multiple dynamics, ranging from economic pressure and barriers to condom use to episodes of forced sex. These factors, often intertwined, form a spiral that reinforces vulnerability and amplifies the risk of HIV transmission.

Based on these findings, it is imperative to implement targeted and comprehensive interventions. It is crucial to develop HIV prevention programs that address the multiple dimensions of vulnerability, including improving access to condoms, lubricants, and self-tests, providing psychological support services, and devising strategies to economically empower these AGYW. Future efforts should focus on increasing their engagement with HIV-related services, enhancing the accessibility and comprehensiveness of these services, and eliminating the socio-cultural barriers that hinder their use of these services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M., Y.N.K. and C.K.; methodology, O.M., C.K. and J.K.K.; software, O.M. and G.Y.N.; validation, J.K.K. and C.M.M. and O.M.; formal analysis, O.M., Y.N.K. and C.K.; data collection, O.M., C.K. and G.Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M., Y.N.K. and C.K.; writing—review and editing, O.M., J.K.K. and C.M.M.; visualization, O.M., J.K.K. and C.M.M.; supervision, J.K.K. and C.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Lubumbashi (Approval number UNILU/CEM/036/2023; December 2nd, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

As the study involved a retrospective secondary analysis of existing data collected as part of routine care and there was no contact with YFSWs, individual informed consent was not required, in accordance with the guidelines for the Ethical Review of Research Involving Human Subjects in the DRC. It was a retrospective case record study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (O.M.).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Cowan, F.M.; Busza. J.; et al. Providing comprehensive health services for young key populations: Needs, barriers and gaps. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2015, 18 2 (Suppl. 1), 19833. [CrossRef]

- Busza, J.; Mtetwa, S.; Mapfumo, R.; Hanisch, D.; Wong-Gruenwald, R.; Cowan, F. Underage and underserved: Reaching young women who sell sex in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 2016, 28 Sup2, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, L-G.; Hosek, S. HIV and adolescents: Focus on young key populations. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2015, 18 2(Suppl. 1), 20076. [CrossRef]

- Hensen, B.; Chabata, S.T.; Floyd, S.; Chiyaka, T.; Mushati, P.; Busza, J.; et al. HIV risk among young women who sell sex by whether they identify as sex workers: Analysis of respondent-driven sampling surveys, Zimbabwe, 2017. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2019, 22, e25410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guure, C.; Dery, S.; Afagbedzi, S.; Maya, E.; da-Costa Vroom, F.B.; Torpey, K. Correlates of prevalent HIV infection among adolescents, young adults, and older adult female sex workers in Ghana: Analysis of data from the Ghana biobehavioral survey. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahmanesh, M.; Cowan, F.; Wayal, S.; Copas, A.; Patel, V.; Mabey, D. The burden and determinants of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in a population-based sample of female sex workers in Goa, India. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2009, 85, 50–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couture M-C, Sansothy N, Sapphon V; et al. Young women engaged in sex work in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, have high incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted infections, and amphetamine-type stimulant use: New challenges to HIV prevention and risk. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2011, 38, 33–9. [CrossRef]

- Busza J, Mtetwa S, Chirawu P, Cowan F. Triple jeopardy: Adolescent experiences of sex work and migration in Zimbabwe. Health Place. 2014, 28, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E; et al. ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: Sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 450–65. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, K., Bal, B., Mukherjee, R., Saha, M. K., Chakraborty, S., Niyogi, S. K., & Bhattacharya, S. K. Young age is a risk factor for HIV among female sex workers—An experience from India. Journal of Infection 2006, 53, 255–259. [CrossRef]

- Su S., Li X., Zhang L., Lin D., Zhang C., & Zhou Y. Age group differences in HIV risk and mental health problems among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS care 2014, 26, 1019–1026. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, D., Couto, M. T., Zucchi, E. M., Calazans, G. J., Dos Santos, L. A., Mathias, A., & Grangeiro, A. (). AIDS-and sexuality-related stigmas underlying the use of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in Brazil: Findings from a multicentric study. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2019, 27, 107–121. [CrossRef]

- Programme National de Lutte contre le Sida et les IST (PNLS). Baromètre analytique de la lutte contre le VIH/Sida en République Démocratique du Congo : Progrès dans la réalisation des objectifs 95-95-95. Kinshasa: PNLS ; 2021.

- Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en œuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM), Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP) et ICF International. Enquête Démographique et de Santé en République Démocratique du Congo 2013-2014. Rockville, Maryland, USA: MPSMRM, MSP et ICF International, 2014.

- Kakisingi C, Muteba M, Mukuku O, Kyabu V, Ngwej K, Kajimb P, Manika M, Situakibanza H, Mwamba C, Ngwej D. Prevalence and characteristics of HIV infection among female sex workers in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 280. [CrossRef]

- World Population Review. Lubumbashi Population 2024. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/lubumbashi-population (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- UNAIDS Global AIDS Update—Confronting inequalities—Lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS. 2021. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2021/2021-global-aids-update (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Baggaley RF, Dimitrov D, Owen BN, Pickles M, Butler AR, Masse B; et al. Heterosexual anal intercourse: A neglected risk factor for HIV? Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 69 (Suppl. 1), 95-105. [CrossRef]

- Shayo, E.H., Kalinga, A.A., Senkoro, K.P. et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with female anal sex in the context of HIV/AIDS in the selected districts of Tanzania. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 140. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, A., DiNenno, E., Honeycutt, A. et al. Contribution of Anal Sex to HIV Prevalence Among Heterosexuals: A Modeling Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 2895–2903. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar K, Bal B, Mukherjee R, Chakraborty S, Saha S, Ghosh A, Parsons S. Sex-trafficking, violence, negotiating skill, and HIV infection in brothel-based sex workers of eastern India, adjoining Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2008, 26, 223–31.

- Wirtz, A. L.; Peryshkina, A.; Mogilniy, V.; Beyrer, C.; Decker, M.R. Current and recent drug use intensifies sexual and structural HIV risk outcomes among female sex workers in the Russian Federation. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, K.; Csete, J. Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. JAMA 2010, 304, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutagoma, M.; Samuel, M.S.; Kayitesi, C.; Gasasira, A.R.; Chitou, B.; Boer, K.; et al. High HIV prevalence and associated risk factors among female sex workers in Rwanda. Int. J. STD AIDS 2017, 28, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Reilly, K. H., Brown, K., Jin, X., Xu, J., Ding, G.; et al. HIV incidence and associated risk factors among female sex workers in a high HIV-prevalence area of China. Sexually transmitted diseases 2012, 39, 835–841.

- Onyango, M.A.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Agyarko-Poku, T.; Asafo, M.K.; Sylvester, J.; Wondergem, P.; et al. “It's all about making a life”: Poverty, HIV, violence, and other vulnerabilities faced by young female sex workers in Kumasi, Ghana. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 68, S131–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwandt, M.; Morris, C.; Ferguson, A.; Ngugi, E.; Moses, S. Anal and dry sex in commercial sex work, and relation to risk for sexually transmitted infections and HIV in Meru, Kenya. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2006, 82, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).