1. Introduction

Surgery combines knowledge of anatomy with skills such as cutting, dissection, bleeding control, and suturing. Electrosurgery was introduced more than 100 years ago [

1] to facilitate cutting and control of bleeding and has been widely used since the introduction of Bovie’s first electrosurgical unit [

2]. Other energy sources, such as lasers, ultracision and plasma jets, were added later.

Electrosurgery uses a high-frequency alternative current of more than 100.000 Hertz to prevent depolarisation of cellular membranes and muscular contractions or nerve stimulation. Electrosurgical devices have changed over time, with voltage stabilizers, separate high-frequency generators for coagulation and cutting for safety reasons [

3], and devices measuring resistance or temperature during coagulation, such as PK and sealing devices.

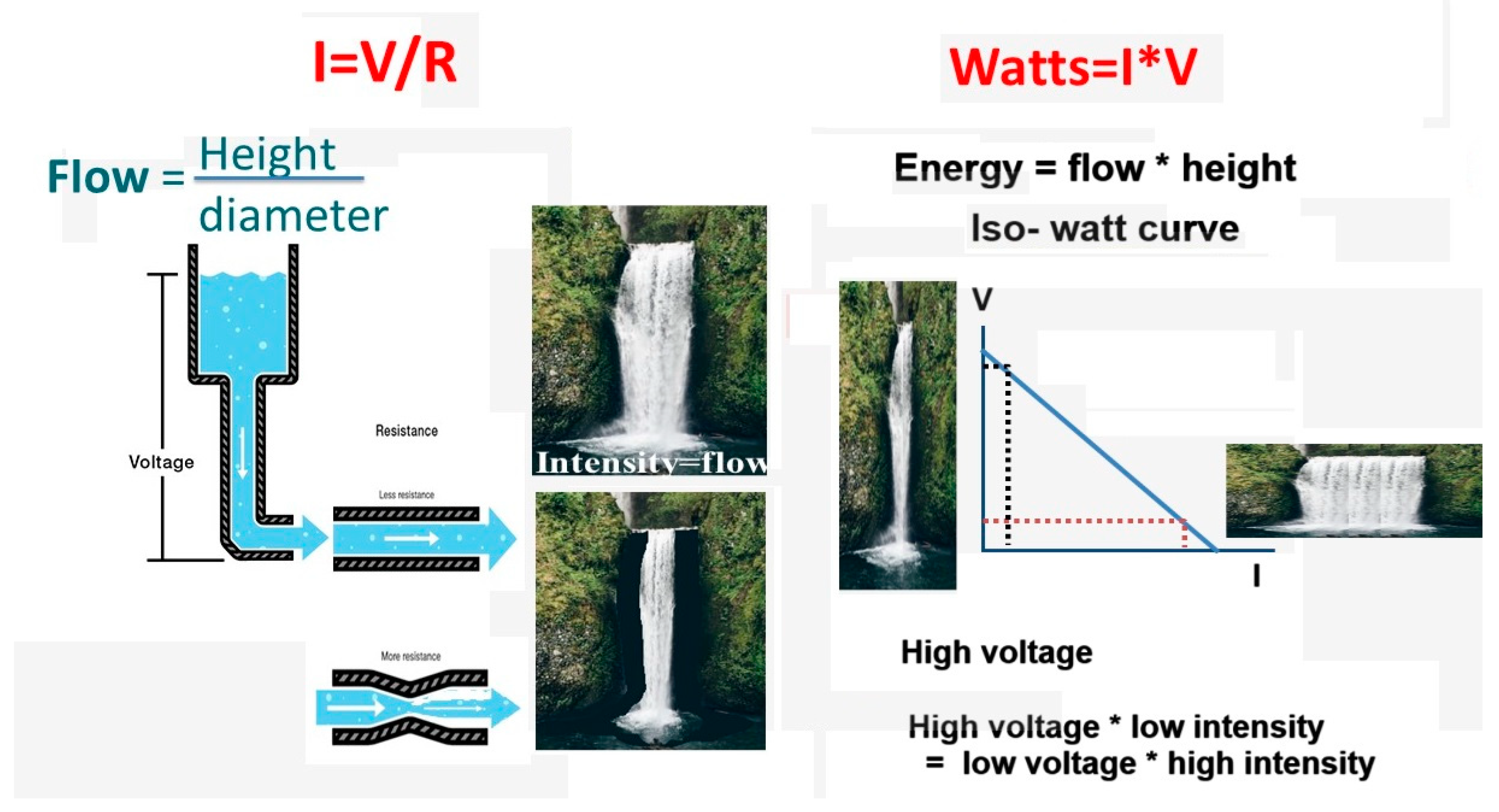

An alternative electrical current is characterized by its frequency, voltage (V) and intensity (I). A fundamental law of electricity is the linear increase of intensity with the voltage and decreases with resistance (R) or I= V/R. The amount of energy in Watts is V*I/sec. It can be confusing for surgeons to translate V, I, R, and W into the electrosurgical device settings and practical surgery, with cutting and coagulating with the same instrument, such as an electric bistouri and controlling the depth of tissue damage. Depth of tissue damage can be critical, knowing that the wall of the colon measures only 1.5 to 3 mm [

4].

Being 100 years old, the terminology used is confusing and lacks precision. Irreversible cellular damage starts at 44°C although slow, and accelerates with temperature becoming almost immediate above 80°C. Damage consists of unwinding the 3D structure or denaturation of proteins forming a coagulum. Coagulation describes three effects: reorganization of proteins, and of collagen forming a coagulum, and desiccation of tissue becoming electrically resistant. All currents have a sinusoidal waveform. Therefore, cutting, blended or coagulating waveforms, as frequently used in the literature [

5] and during live surgery, misleadingly suggest a different waveform, although they only differ in voltage and duty cycle. Radiofrequency [

5], although an electromagnetic wave, and a high-frequency alternative electric current, are often used interchangeably for historical reasons to indicate that the frequency is similar to those used in radio transmission. Impedance and resistance are also often used interchangeably, although the difference is clinically not significant. Impedance is used for alternative currents with the changing voltage over time, resulting in alternating intensity and resistance.

Since understanding electrosurgery is important for the surgeon [

6] we planned to review electrosurgery. A discussion of when to use other energies, such as lasers and ultracision, is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

2. Electrosurgery Basics

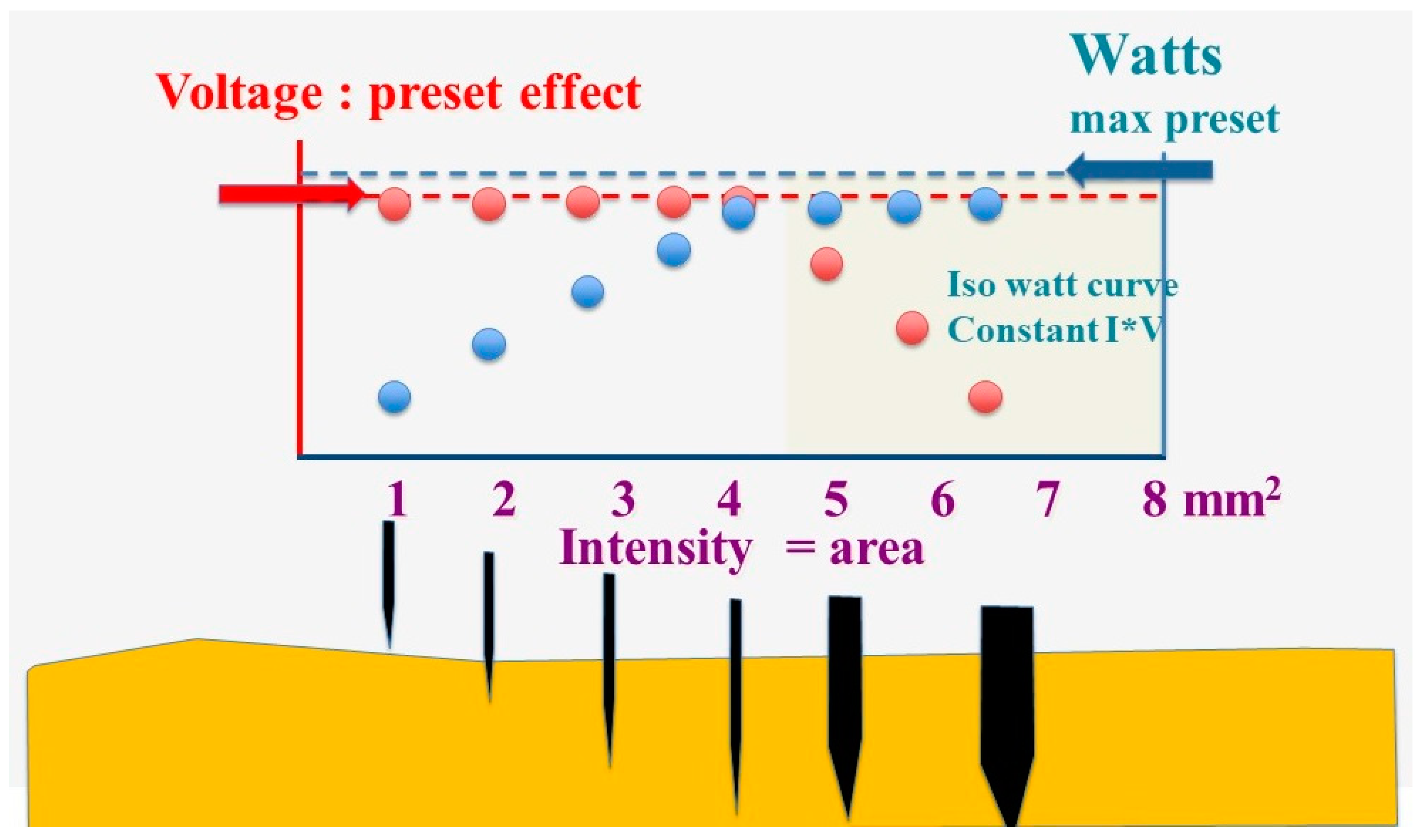

Electrosurgery uses an alternating current with a frequency of more than 100.000 Hertz, generally between 250.000 and 500.000 Hertz, to avoid depolarization of cell membranes, muscle contractions and nerve stimulation. Voltage is defined as the peak or highest voltage of an alternating current. Electricity follows Ohm’s law, I= V/R, describing the relationship between voltage, resistance and intensity. The resistance of wet tissue, such as in gynaecological or abdominal surgery, is low. Therefore, the intensity of the current varies only with the voltage and the contact area of the instrument with the tissue (

Figure 1).

The energy (Watts, W) increases with the voltage and the intensity (W=I*V/sec). Therefore, the same amount of energy can be obtained with a low voltage and high intensity or high voltage and low intensity, also called the iso-Watt curve.

The electrosurgical device permits limiting the maximal output (W) and setting of the voltage, generally indicated as the force. If the voltage is fixed, the intensity varies only with the contact area of the surgical instrument with the tissue. The intensity is low when the contact area is small and only a tiny part of the available Watts are used. The intensity increases with the contact area till the preset maximal output is reached. When the contact area increases further, the intensity rises further, and the voltage has to drop when V*I exceeds the preset output.

Figure 2.

The electrosurgery unit’s maximal output (Watts) and the voltage (or force) are preset. The intensity (blue dots) is minimal when the contact area is small and increases with the contact area, but voltage (red dots) remains constant till the preset maximal output is reached (left white area). When the contact area increases further, the increasing intensity results in I*V exceeding the maximal preset output, and the voltage has to decrease according to the isowatt curve (right yellow area).

Figure 2.

The electrosurgery unit’s maximal output (Watts) and the voltage (or force) are preset. The intensity (blue dots) is minimal when the contact area is small and increases with the contact area, but voltage (red dots) remains constant till the preset maximal output is reached (left white area). When the contact area increases further, the increasing intensity results in I*V exceeding the maximal preset output, and the voltage has to decrease according to the isowatt curve (right yellow area).

It should be realized that over time, the same amount of energy can be delivered by a continuous alternative current (I*V) or by a current with twice the voltage during half the time or 4 times the voltage a quarter of the time. This is the duty cycle, although often erroneously described as an altered waveform or a wave modulation.

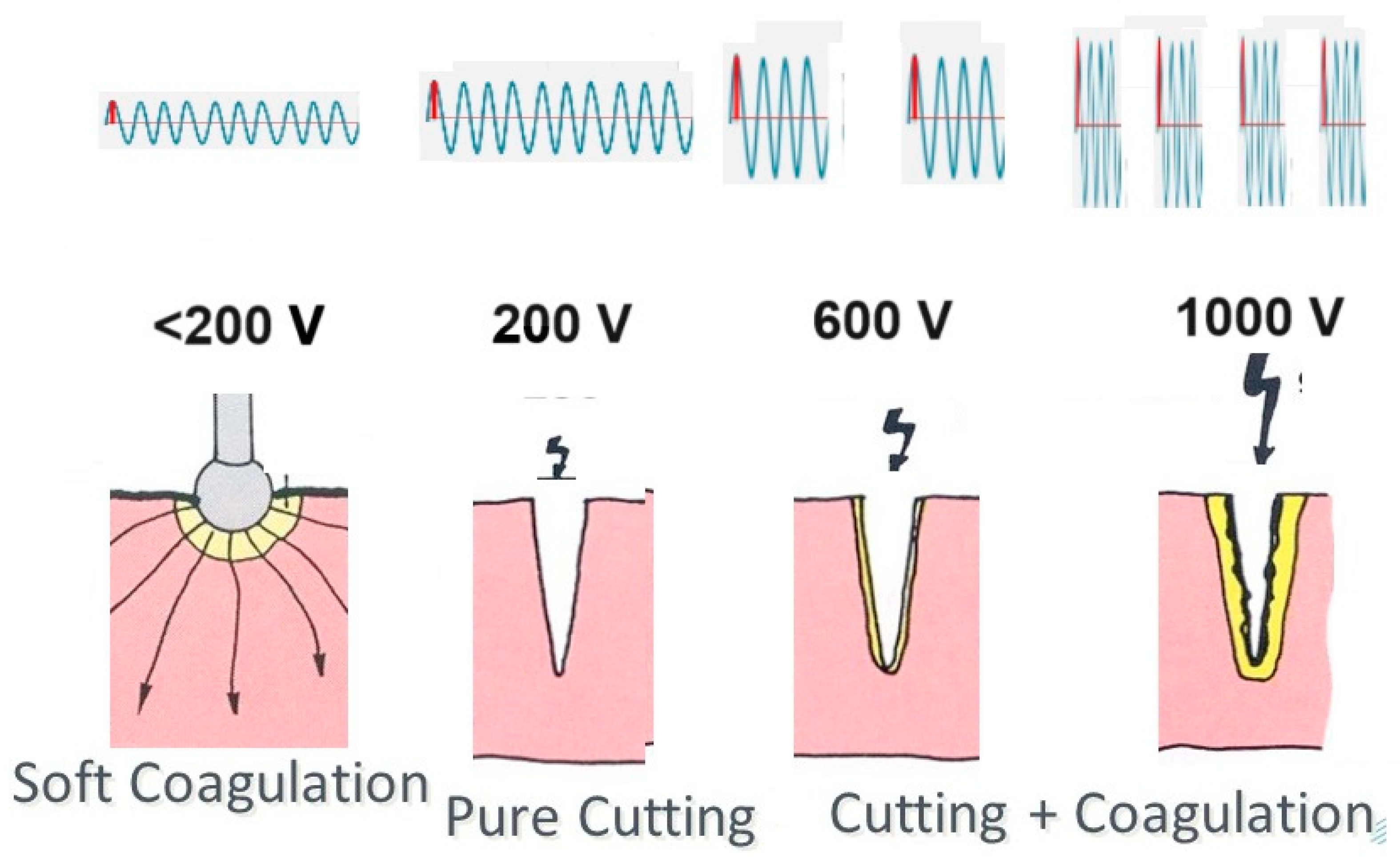

Sparks occur between the electrosurgical instrument and the tissue if the voltage is higher than 200V and the distance is short. A spark initiates more quickly when the instrument has a sharp edge or a point, but the electric arc is maintained more easily once started.

Electrosurgery devices do not indicate the precise preset voltage but rather a range like force 1 to 4. Historically, electrosurgical currents were short sequences of high voltages decreasing rapidly until voltage stabilizers became available. Another reason is that the voltage can vary slightly with intensity during surgery because of the device’s internal resistance.

3. Tissue effects

Electrosurgery heats tissue, and the temperature varies with the energy delivered over time, tissue volume, and cooling or diffusion of heat. Tissue effects vary with the temperature and its duration. Tissue damage starts at 44°C but is slow. With increasing temperatures damage accelerates, becoming immediate above 80°C with denaturation of proteins. At 100°C, water starts boiling with desiccation of tissue. Minor variations of boiling temperature because of pressure or electrolytes are irrelevant for electrosurgery. Slow boiling causes desiccation by evaporation of water leaving the minerals. At much higher temperatures, all water transforms suddenly into steam, causing an explosion of cells, called vaporization. Above 300°C, proteins and nucleic acids start to oxidize, combining the hydrogen or organic molecules with the oxygen in the air and leaving the carbon, called charring.

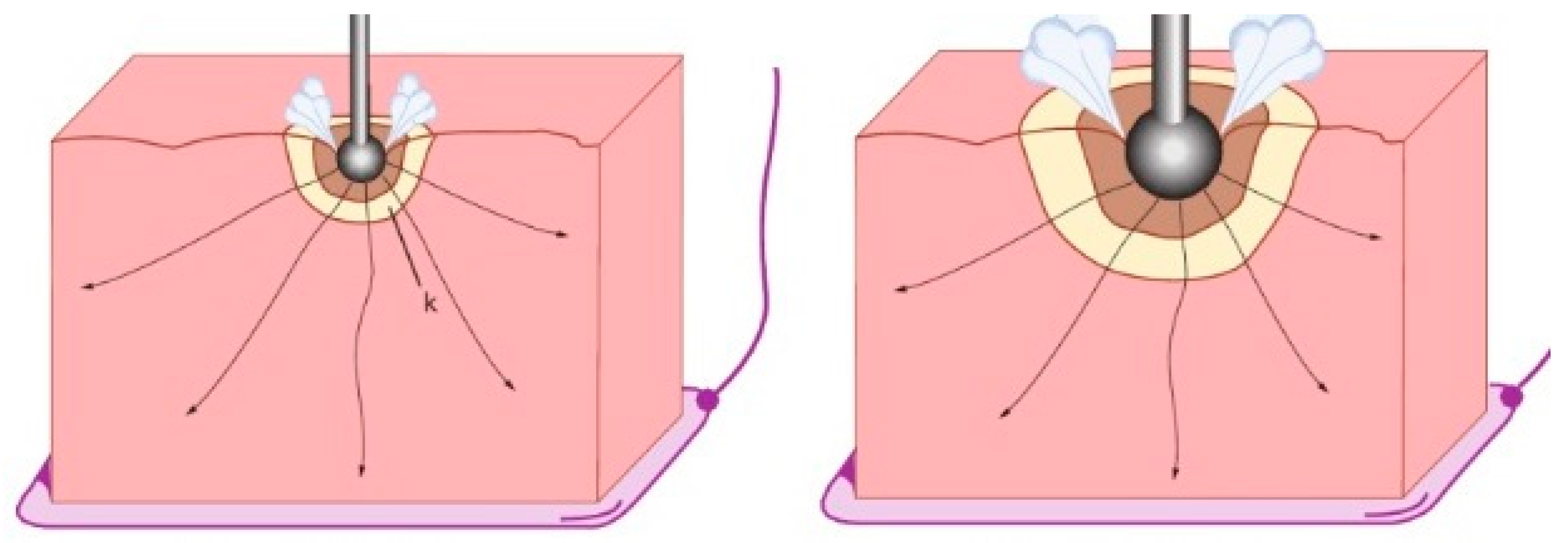

In the absence of sparks, the tissue in close contact with the instrument starts to heat since the tissue’s resistance is higher than that of the instrument. Heating is mainly local because the power density decreases exponentially (to the third power) with the volume of tissue in all directions.

An electric spark occurs when a sufficiently high electric field creates an ionized, electrically conductive channel through a normally insulating medium such as air or CO2, resulting in an electric arc with very high temperatures above 1000°C. The fact that distances to initiate a spark are slightly shorter in a CO2 environment than in air is clinically insignificant [

7]. These high temperatures cause an explosion of the superficial cells or vaporization, resulting in tissue cutting. With increasing voltage, sparks become stronger and cause, besides superficial vaporization, progressively deeper heating of tissue and coagulation (

Figure 3).

3. Electrosurgical coagulation

Soft coagulation occurs when the voltage is below 200V, preventing sparks. The electric current heats the tissue progressively until at 100°C, steam development stops electricity, air or steam being a good isolator. A lower voltage results in less intensity and slower heating and, thus, deeper coagulation before the steam of boiling under the contact area stops the current. Similarly, a larger contact area increases the coagulation depth (

Figure 4). However, slow coagulation can be challenging to control or inefficient during surgery if the coagulation area is large and cooled by bleeding. Therefore, many surgeons prefer to use higher energy and or voltage settings.

Coagulation with higher energy settings or voltages is tricky and must be understood to be controlled by the surgeon. Higher energy settings (W) might seem incompatible with slow and deep coagulation. However, the surgeon can grasp a large area of tissue, increasing the contact area (and I), thus decreasing the V. Alternatively, tissues can be prevented from reaching 100°C and boiling by intermittent coagulation, permitting cooling or by actively cooling the coagulation area by irrigation. Thus, voltages above 200V can be used without sparking by taking advantage of a higher intensity by grasping a larger area, decreasing the voltage if the output (Watts ) is limited. This also explains that grasping and coagulating repetitively for short periods can be an effective method of coagulation, which is faster and more versatile than soft coagulation. Another example of manipulating voltage during surgery is the electrical bistouri. The sharp edge cuts tissue by multiple sparks, but the flat area coagulates when the high intensity decreases the voltage because of the large contact area. This voltage drop is illustrated in the right half of

Figure 2.

4. Electrosurgical cutting

Electrosurgical cutting equals sparking and vaporization of tissue. Therefore, superficial cutting of thin tissues, such as the peritoneum, is similar with a 15 or 30 or 300 Watts setting. This is illustrated in the left part of

Figure 2 when the watts used are much less than the maximal watt output. However, cutting a larger amount of tissue, such as 1 cm with the electrical bistouri, generates multiple sparks along the contact area, requiring a higher power setting to prevent a voltage drop. The maximal output setting (Watts) thus determines the maximal area that can be sectioned without dropping the voltage.

During monopolar cutting, the superficial coagulation of the tissue increases with the voltage (

Figure 3).

5. Comments on coagulation and cutting during surgery

Monopolar versus bipolar coagulation or cutting are not discussed separately to emphasize that they are not fundamentally different besides electricity flowing between 2 electrodes instead of between one electrode and the return plate.

Bipolar coagulation is localized between the two tips, permitting underwater coagulation. Clinically, this can be used for pinpoint coagulation by limiting the lateral spread of heat and damage by continuous irrigation, as we used to do in microsurgery. Coagulation during irrigation and intermittent coagulation retain their full importance when coagulating bleeding following ovarian cyst excision to prevent oocyte damage.

Figure 4.

The depth of coagulation increases with a longer duration of heating and more heat diffusion before the current is stopped by steam development. Deeper coagulation thus occurs when the voltage is lower or when the contact area is larger.

Figure 4.

The depth of coagulation increases with a longer duration of heating and more heat diffusion before the current is stopped by steam development. Deeper coagulation thus occurs when the voltage is lower or when the contact area is larger.

The maximal power output determines the amount of tissue that can be cut. Therefore, it is also a safety feature, limiting accidents during inadvertent movements by dropping the voltage if the contact area becomes large. For example, a 30 watt output permits cutting 0.5 cm of tissue but prevents accidentally cutting a bowel over 2 cm.

Using the drop in voltage by increasing the contact area requires a limited output. Therefore, a power setting of around 30 Watts is a logical and nice compromise for most gynaecologic surgeons.

To cut, electricity needs to be activated before contact, permitting sparks, whereas, for coagulation, electricity is activated after contact. This is valid for soft coagulation below 200V, and when voltage needs to be dropped by a higher contact area.

A specific application is bipolar cutting. For example, to penetrate the peritoneum, a bipolar with a sparking voltage close to the peritoneum can cut the peritoneum superficially, which is subsequently entered with simple pressure.

Other applications are so-called intelligent instruments, registering resistance and temperature to optimize coagulation. During bipolar coagulation, the rapid temperature increase and steam development can be prevented by intermittent cooling periods until an acute increase in resistance indicates desiccation (PK devices). A combination of tissue compression and controlling temperature around 80°C results in the fusion of proteins and collagen with limited lateral spread. This is achieved in sealing devices, permiting to secure larger vessels and coagulate fat tissue, fat having a much higher impedance and a low water content.

6. Electrosurgical safety

Electrosurgery requires a grounding plate to return the electrical current. This plate should have a large contact area over a well-irrigated muscle mass without areas of higher resistance between the active electrode and the plate. The plate should not be placed under the knee since bone has a higher electric resistance than soft tissues, with a risk of local heating and damage. As a safety measure to avoid partially detached grounding plates, resistance between 2 halves can be monitored. Direct coupling permits energy transmission from one instrument to another, as done in open and laparoscopic surgery before the grasping bipolar forceps became available. Insulation failure results in unintended electric current, sparking and accidents. Capacitive coupling is the transmission of an alternating electric current without contact: with two opposing metal plates, the second becomes positive or negative, when the first is negative or positive, respectively. This can occur during surgery when a metal trocar, insulated from the abdominal wall with a plastic screw, picks up the alternating current from an inserted instrument. Electrosurgery instruments can remain hot after being used, occasionally damaging other tissues [

8].

7. Discussion

Electrosurgery is regulated by the power (Watts) and voltage settings (Forces) generating heat and the balance between energy delivery over time and the cooling or diffusion of heat. Although the principles are straightforward, the role of the surgeon is important. The surgeon chooses a voltage and a maximal output for cutting and coagulation that are appropriate to his skills, his choice of instruments, and his technique for the intervention. Changing electrosurgery settings during surgery is rarely done, mainly because it is impractical and interrupts the flow of surgery. Therefore, the power setting at the beginning of an intervention is fundamental. Permitting the same instrument to cut and coagulate by modifying the contact area (and, thus, the voltage), contributes to the versatility of electrosurgery.

Depth of Coagulation and depth of heat damage are critical in ovarian and bowel surgery. The wall of the colon is only 1.5 to 3 mm thick and thus requires very superficial coagulation. Coagulation of bleeding during ovarian surgery is unavoidably associated with some tissue damage when heated above 45 °C. Limiting the coagulation depth means pinpoint coagulation, as short as possible, e.g. 1 sec [

9] with a voltage as close as possible to 200 V, and using bipolar instruments with a small tip. The importance of short coagulation was illustrated by the damaged volume [

10] and depth being 1.1 and 1.3 mm after a 2 or 4 sec of bipolar coagulation with a setting of coag force three and 30W without mentioning the tip size. Plasma jets or plasma scalpels [

11] are unlikely to permit pinpoint coagulation since a spark at a distance is not suited for intermittent or underwater coagulation or for localized coagulation.

Blended current was a concept of the past when the electricity used in electrosurgery was generated using capacitators without a voltage stabilizer, causing a burst of alternating current starting with a high voltage that decreased rapidly. These currents initially coagulate and are later pure cut.

Lasers and ultrasonic devices have specific characteristics and advantages. Because of the nearly 100% adsorption in water, a focused, intermittent, high-density CO2 laser is close to perfect for the superficial vaporization of tissue with minimal lateral spread, such as the vaporization of superficial endometriosis. Ultrasonic devices generate less lateral heat and are not hampered by fat, e.g. during bowel surgery. However, electrosurgery remains the most versatile allround instrument for dissection and coagulation in laparoscopic surgery. The electrosurgical units and instruments have improved progressively, with the grasping bipolar forceps as an example. Unfortunately, all bipolar forceps are a compromise between grasping strength and a tip small enough to permit pinpoint coagulation. Also, the surgeon’s choice of using the tip of scissors, a needle, or a hook for electrosurgical cutting mainly varies with experience and not because of underlying electricity rules. This explains the development of coagulation and sealing devices controlling temperature, resistance and pressure with new developments in the pipeline, such as deep learning and artificial intelligence [

12] or the introduction of acoustic signals signalling the instrument tissue interaction [

13].

8. Conclusions

Electrosurgery is the most versatile source of energy during surgery, permitting dissection, cutting and coagulation. Voltages are primarily important for tissue effects, but the absence of a voltage setting on the electrosurgical devices and non-precise terminology risks causing confusion among surgeons when choosing their energy sources.

Author Contributions

This manuscript resulted from many discussions between the authors and others. The final text was approved by all authors.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gmbh, E. The beginnings of electrosurgical technology 1923-1962. Available online: https://en.erbe-med.com/en-en/company/history/3rd-generation/.

- Bovie, W.T. A preliminary note on a new surgical-current generator. 1928. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Farin, G. High-frequency surgical apparatus. 4,171,700, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Farin, G.; Grund, K.E. Principles of electrosurgery, laser, and argon plasma coagulation with particular regard to endoscopy. In Advanced Digestive Endoscopy: Practice and Safety; Cotton, P.B., Ed.; John Wiley & sons, 2009; pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, M.G. Fundamentals of Electrosurgery Part I: Principles of Radiofrequency Energy for Surgery. In The SAGES Manual on the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE); Feldman, L.S., Fuchshuber, P.R., D.B., J., Eds.; Springer, 2012; pp. 15–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vilos, G.A.; Rajakumar, C. Electrosurgical generators and monopolar and bipolar electrosurgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013, 20, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culp, W.C., Jr.; Kimbrough, B.A.; Luna, S.; Maguddayao, A.J.; Eidson, J.L.; Paolino, D.V. Use of the electrosurgical unit in a carbon dioxide atmosphere. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2016, 40, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, F.; Hüttner, R.; Mehner, P.J.; Henkel, K.; Paschew, G.; Herzog, M.; Martens, N.; Richter, A.; Hinz, S.; Groß, J.; et al. Temperature profile and residual heat of monopolar laparoscopic and endoscopic dissection instruments. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 4507–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanovic, S.; Sütterlin, M.; Gaiser, T.; Scharff, C.; Neumann, M.; Berger, L.; Froemmel, N.; Tuschy, B.; Berlit, S. Microscopic, Macroscopic and Thermal Impact of Argon Plasma, Diode Laser, and Electrocoagulation on Ovarian Tissue. In Vivo 2023, 37, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siracusano, S.; Marchioro, G.; Scutelnic, D.; Brunelli, M.; Talamini, R.; Porcaro, A.B.; Fiorini, P.; Muradore, R.; Daffara, C. Measuring thermal spread during bipolar cauterizing using an experimental pneumoperitoneum and thermal sensors. Frontiers in Surgery 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Liu, D.; He, D.; Lu, X.; Ostrikov, K. Plasma Scalpels: Devices, Diagnostics, and Applications. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Rahul; De, S. A deep learning-based hybrid approach for the solution of multiphysics problems in electrosurgery. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2019, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostler, D.; Seibold, M.; Fuchtmann, J.; Samm, N.; Feussner, H.; Wilhelm, D.; Navab, N. Acoustic signal analysis of instrument–tissue interaction for minimally invasive interventions. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2020, 15, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).