Submitted:

24 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings and Population

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Sampling and Sampling Procedure

2.5. Data Collection Procedures

2.7. Wealth Index Determination

2.8. Dietary Assessment

2.9. Anthropometrics Indices

2.10. Statistical Analysis Methods

2.11. Data Quality Control

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Caregivers/Parents and Children

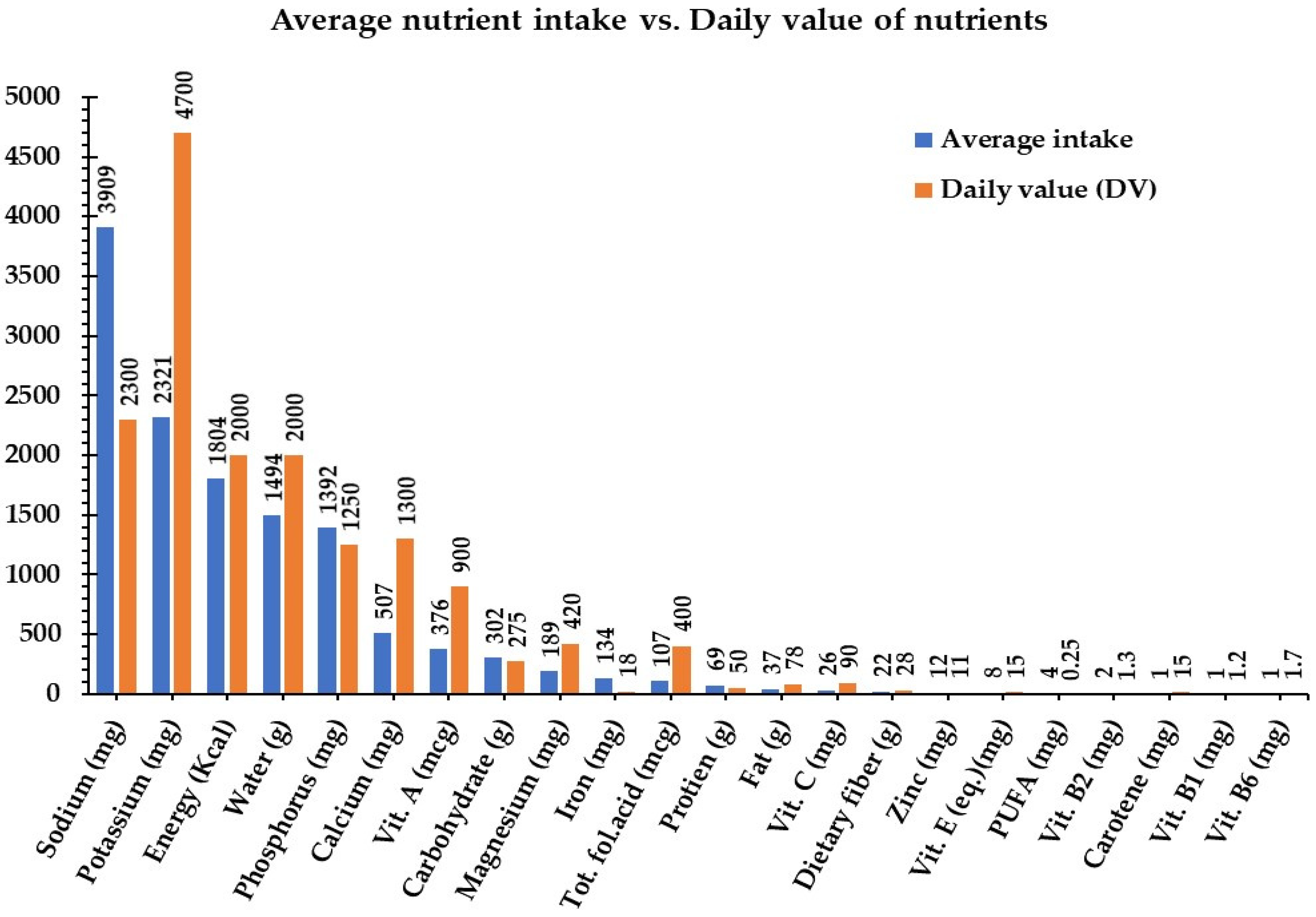

3.2. Macro and Micronutrient Nutrient Intake of School-Age Children

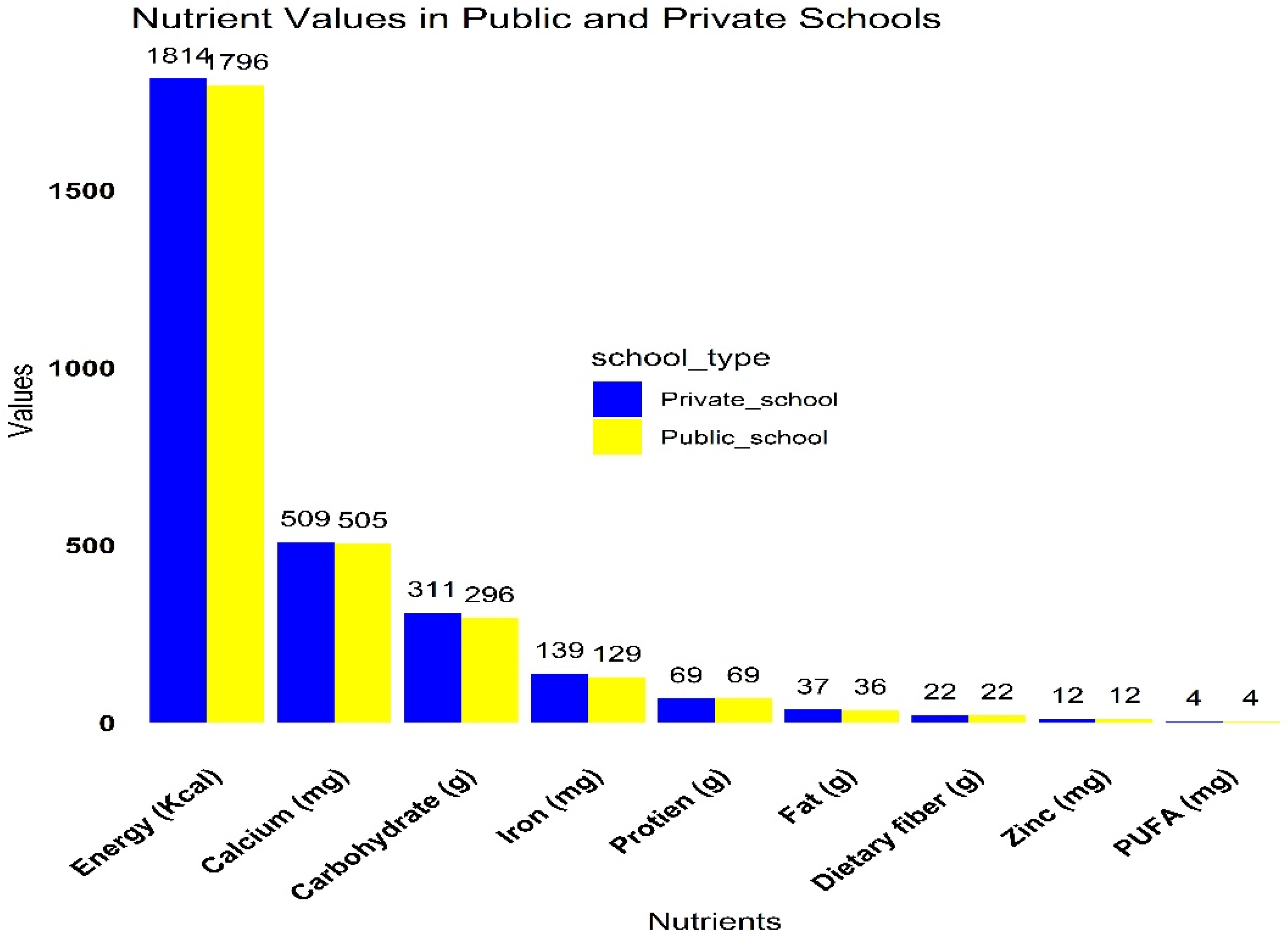

3.3. Macro and Micronutrient Intake by School Type

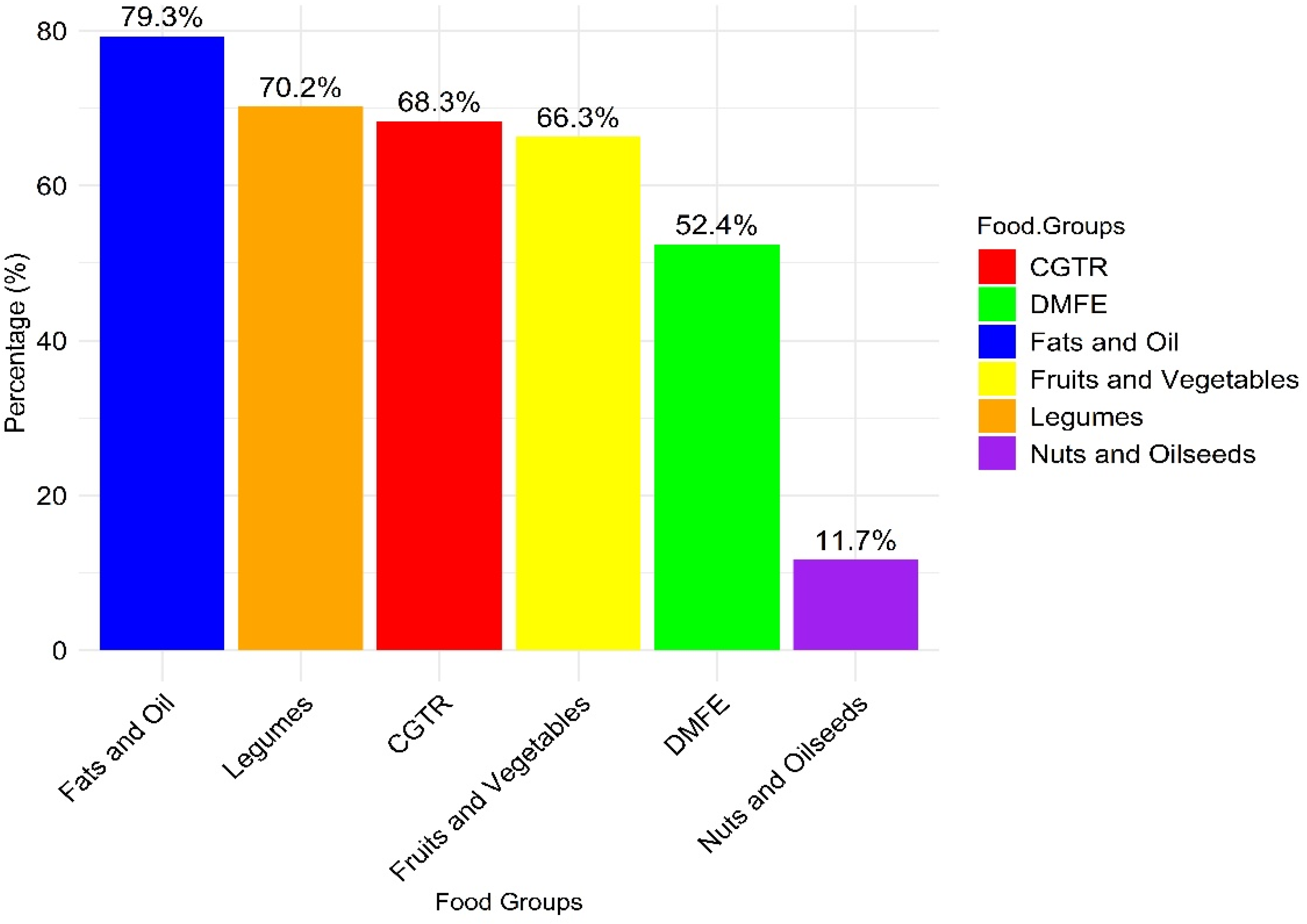

3.4. Dietary Diversity and Nutritional Gaps in Urban Low-Income School Children

3.5. Nutritional Status of School-Age Children

3.6. Factors Associated with Stunting among School-Age Children

3.7. Factors Associated with Wasting among School-Age Children

3.8. Factors Associated with Underweight and Overweight among School-Age Children

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Muthuri, S.K.; Oti, S.O.; Mutua, M.K.; Van De Vijver, S.; Kyobutungi, C. Evidence of a double burden of malnutrition in urban poor settings in Nairobi, Kenya. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malnutrition. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: key findings of the 2021 edition. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025257 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- UNICEF Ethiopia Country Office Annual Report 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/country-regional-divisional-annual-reports-2021/Ethiopia (accessed on March 2022).

- Mohammed, S.H.; Habtewold, T.D.; Arero, A.G.; Esmaillzadeh, A. The state of child nutrition in Ethiopia: an umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analysis reports. BMC Pediatr 2020, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degarege, D.; Degarege, A.; Animut, A. Undernutrition and associated risk factors among school-age children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Global health. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 7. Unicef. UNICEF, WHO, The World BANK. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition, Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates 2020 Edition. 2020 Edition 2020.

- Hirvonen, K.; de Brauw, A.; Abate, G.T. Food Consumption and Food Security during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Addis Ababa. Am J Agric Econ 2021, 103, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Compte, M.; Burrola-Méndez, S.; Lozano-Marrufo, A.; Ferré-Eguiluz, I.; Flores, D.; Gaitán-Rossi, P.; Teruel, G.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Urban poverty and nutrition challenges associated with accessibility to a healthy diet: a global systematic literature review. International Journal for Equity in Health 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. The Lancet 2020, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.; Zhao, Y.; Slivka, L.; Wang, Y. Double burden of diseases worldwide: coexistence of undernutrition and overnutrition-related non-communicable chronic diseases. Obes Rev 2018, 19, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthy Eating Learning Opportunities and Nutrition Education. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/school_nutrition_education.htm (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Central Statistical Agency - CSA/Ethiopia; ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016; CSA and ICF: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Population Projection. Available online: http://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/population-projection/ (accessed on July 2023).

- Issa, E.H. Life in a slum neighborhood of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: morphological facts and their dysfunctions. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Ogston, S.A.; Lemeshow, S.; Hosmer, D.W.; Klar, J.; Lwanga, S.K. Adequacy of Sample Size in Health Studies. Biometrics 1991, 47, 347–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerfu, M.; Mekasha, A. Anthropometric assessment of school-age children in Addis Ababa. Ethiopian Medical Journal 2006, 44, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heidari, S.; Babor, T.F.; De Castro, P.; Tort, S.; Curno, M. Sex, and Gender Equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Research Integrity and Peer Review 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutstein, S.O. Steps to constructing the new DHS wealth index. Rockville, MD: ICF International 2015, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia: Food-Based Dietary Guidelines-2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/ethiopia/en/ (accessed on March 2014).

- 24-hour dietary recalls. IN: DAPA Measurement Toolkit. Available online: https://dapa-toolkit.mrc.ac.uk/diet/subjective-methods/24-hour-dietary-recall (accessed on September 2020).

- Medicine, I.o. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2006; p. 1344. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Anthro for personal computers. Available online: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/ (accessed on September 2020).

- Guide to Anthropometry: A Practical Tool for Program Planners, Managers, and Implementers. Available online: https://www.ennonline.net/fex/58/guidetoanthropometry (accessed on Sep 13, 2018).

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 23.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on Jun 27, 2022).

- EpiData Software Available online:. Available online: https://www.epidata.dk/ (accessed on June 2004).

- Lázaro Cuesta, L.; Rearte, A.; Rodríguez, S.; Niglia, M.; Scipioni, H.; Rodríguez, D.; Salinas, R.; Sosa, C.; Rasse, S. Anthropometric and biochemical assessment of nutritional status and dietary intake in school children aged 6-14 years, Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Arch Argent Pediatr 2018, 116, e34–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Sobaler, A.M.; Aparicio, A.; Rubio, J.; Marcos, V.; Sanchidrián, R.; Santos, S.; Pérez-Farinós, N.; Dal-Re, M.; Villar-Villalba, C.; Yusta-Boyo, M.J.; et al. Adequacy of usual macronutrient intake and macronutrient distribution in children and adolescents in Spain: A National Dietary Survey on the Child and Adolescent Population, ENALIA 2013-2014. Eur J Nutr 2019, 58, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, K.H.; Belachew, T. Care and not wealth is a predictor of wasting and stunting of 'The Coffee Kids' of Jimma Zone, southwest Ethiopia. Nutr Health 2017, 23, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariku, E.Z.; Abebe, G.A.; Melketsedik, Z.A.; Gutema, B.T. Prevalence and factors associated with stunting and thinness among school-age children in Arba Minch Health and Demographic Surveillance Site, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0206659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getaneh, Z.; Melku, M.; Geta, M.; Melak, T.; Hunegnaw, M.T. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and wasting among public primary school children in Gondar town, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr 2019, 19, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogale, T.Y.; Bala, E.T.; Tadesse, M.; Asamoah, B.O. Prevalence and associated factors for stunting among 6-12 years old school-age children from rural community of Humbo district, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantie, G.M.; Aynie, A.A.; Akenew, K.H.; Belete, M.T.; Tena, E.T.; Gebretsadik, G.G.; Tsegaw, A.N.; Woldemariam, T.B.; Woya, A.A.; Melese, A.A.; et al. Prevalence of stunting and associated factors among public primary school pupils of Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia: School-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0248108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfin, F.; Worku, A.; Birhane, Y. Prevalence and associated factors of stunting among primary school children in Eastern Ethiopia. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements 2015, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, J.; Lang, C.; du Randt, R.; Gresse, A.; Long, K.Z.; Ludyga, S.; Müller, I.; Nqweniso, S.; Pühse, U.; Utzinger, J.; et al. Prevalence of Stunting and Relationship between Stunting and Associated Risk Factors with Academic Achievement and Cognitive Function: A Cross-Sectional Study with South African Primary School Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metwally, A.M.; El-Sonbaty, M.M.; El Etreby, L.A.; El-Din, E.M.S.; Hamid, N.A.; Hussien, H.A.; Hassanin, A.; Monir, Z.M. Stunting and its determinants among governmental primary school children in Egypt: A school-based cross-sectional study. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Macías, N.; Rivera, M.; Barquera, S.; Hernández, L.; García-Guerra, A.; Rivera, J.A. Energy and nutrient intake among Mexican school-aged children, Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. Salud Publica Mex 2009, 51 Suppl 4, S540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksono, A.D.; Sukoco, N.E.W.; Rachmawati, T.; Wulandari, R.D. Factors Related to Stunting Incidence in Toddlers with Working Mothers in Indonesia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, F.; Asim, M.; Salim, S.; Humayun, A. House ownership, frequency of illness, fathers' education: the most significant socio-demographic determinants of poor nutritional status in adolescent girls from low-income households of Lahore, Pakistan. Int J Equity Health 2017, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yisak, H.; Tadege, M.; Ambaw, B.; Ewunetei, A. Prevalence and Determinants of Stunting, Wasting, and Underweight Among School-Age Children Aged 6-12 Years in South Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2021, 12, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hailegebriel, T. Prevalence and Determinants of Stunting and Thinness/Wasting Among Schoolchildren of Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Food Nutr Bull 2020, 41, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Mahmood, S.E.; Srivastava, P.M.; Shrotriya, V.P.; Kumar, B. Nutritional status of school-age children - A scenario of urban slums in India. Arch Public Health 2012, 70, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altare, C.; Delbiso, T.D.; Mutwiri, G.M.; Kopplow, R.; Guha-Sapir, D. Factors Associated with Stunting among Pre-school Children in Southern Highlands of Tanzania. J Trop Pediatr 2016, 62, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuwaja, S.; Selwyn, B.J.; Shah, S.M. Prevalence and correlates of stunting among primary school children in rural areas of southern Pakistan. J Trop Pediatr 2005, 51, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Agardh, A.; Ma, J.; Li, L.; Lei, Y.; Stafford, R.S.; Prochaska, J.J. National trends in stunting, thinness and overweight among Chinese school-aged children, 1985-2014. Int J Obes (Lond) 2019, 43, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, A.L.; Hentschel, E.; Fulcher, I.; Ravà, M.S.; Abdulkarim, G.; Abdalla, O.; Said, S.; Khamis, H.; Hedt-Gauthier, B.; Wilson, K. Caregiver parenting practices, dietary diversity knowledge, and association with early childhood development outcomes among children aged 18-29 months in Zanzibar, Tanzania: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, W.; Argaw, D.; Kabthymer, R.H.; Wudneh, A. Prevalence and associated factors of wasting among school children in Ethiopia: Multi-centered cross-sectional study. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2022, 14, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, M.; Nibret, E.; Munshea, A. Prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and malnutrition among schoolchildren of the Zegie Peninsula, northwestern Ethiopia. J Infect Public Health 2017, 10, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mationg, M.L.S.; Williams, G.M.; Tallo, V.L.; Olveda, R.M.; Aung, E.; Alday, P.; Reñosa, M.D.; Daga, C.M.; Landicho, J.; Demonteverde, M.P.; et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections and nutritional indices among Filipino schoolchildren. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021, 15, e0010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiadas, M.G.; Antonyraja, A.; Viswalingam, A.; Thangaraja, K.; Wickramasinghe, V.P. Nutritional status of school children living in Northern part of Sri Lanka. BMC Pediatr 2021, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dela Luna, K.L.G.; Talavera, M.T.M. Factors Affecting the Nutritional Status of School-aged Children Belonging to Farming Households in the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Science 2021, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, T.M.; Andargie, K.T.; Alula, R.A.; Kebede, B.M.; Gujo, M.M. Factors associated with wasting and stunting among children aged 06-59 months in South Ari District, Southern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr 2023, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hioui, M.; Ahami, A.; Fadel, H.; Azzaoui, F.-Z. Anthropometric measurements of school children in North-Eastern Morocco. International Research Journal of Public and Environmental Health 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fufa, D.A.; Laloto, T.D. Factors associated with undernutrition among children aged between 6–36 months in Semien Bench district, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rah, J.H.; Akhter, N.; Semba, R.D.; Pee, S.D.; Bloem, M.W.; Campbell, A.A.; Moench-Pfanner, R.; Sun, K.; Badham, J.; Kraemer, K. Low dietary diversity is a predictor of child stunting in rural Bangladesh. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, B.; Abbasalizad Farhangi, M.; Asghari, S.; Amirkhizi, F.; Dahri, M.; Abedimanesh, N.; Farsad-Naimi, A.; Hojegani, S. Child-specific food insecurity and its sociodemographic and nutritional determinants among Iranian schoolchildren. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 2016, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otuneye, A.T.; Ahmed, P.A.; Abdulkarim, A.A.; Aluko, O.O.; Shatima, D.R. Relationship between dietary habits and nutritional status among adolescents in Abuja municipal area council of Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics 2017, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getaneh, Z.; Melku, M.; Geta, M.; Melak, T.; Hunegnaw, M.T. Prevalence and determinants of stunting and wasting among public primary school children in Gondar town, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatrics 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Cooten, M.H.; Bilal, S.M.; Gebremedhin, S.; Spigt, M. The association between acute malnutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene among children aged 6-59 months in rural Ethiopia. Matern Child Nutr 2019, 15, e12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Asif, C.A.A.; Barua, A.; Banerjee, A.; Kalam, M.A.; Kader, A.; Wahed, T.; Noman, M.W.; Talukder, A. Association of access to water, sanitation and handwashing facilities with undernutrition of children below 5 years of age in Bangladesh: evidence from two population-based, nationally representative surveys. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebeje, D.B.; Agitew, G.; Mengistu, N.W.; Aychiluhm, S.B. Under-nutrition and its determinants among school-aged children in northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.A.; Shukla, N.K.; Mandala, S.R. "Assessment of Nutritional Status of Rural Children (0-18 years) in Central India Using World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards 2007". Indian J Community Med 2020, 45, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrie, A.; Alebel, A.; Zegeye, A.; Tesfaye, B.; Ferede, A. Prevalence and associated factors of overweight/ obesity among children and adolescents in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Obes 2018, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, R.H.; Hakim, B.N.A.; Mitra, A.K.; Shahril, M.R.; Mohamed, W.; Wafa, S.; Burgermaster, M.; Mohamed, H.J.J. Higher Parental Age and Lower Educational Level are Associated with Underweight among Preschool Children in Terengganu, Malaysia. J Gizi Pangan 2022, 17, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanam, S.J.; Haque, M.A. Prevalence And Determinants Of Malnutrition Among Primary School Going Children In The Haor Areas Of Kishoreganj District Of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyallo, F.; Makokha, A.; Mwangi, A.M. Overweight and obesity among public and private primary school children in Nairobi, Kenya. Health 2013, 05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosha, T.C.; Fungo, S. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children aged 6-12 years in Dodoma and Kinondoni municipalities, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res 2010, 12, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Lahham, S.; Jaradat, N.; Altamimi, M.; Anabtawi, O.; Irshid, A.; AlQub, M.; Dwikat, M.; Nafaa, F.; Badran, L.; Mohareb, R.; et al. Prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity among Palestinian school-age children and the associated risk factors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr 2019, 19, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagbo, H.; Ekouevi, D.K.; Ranjandriarison, D.T.; Niangoran, S.; Bakai, T.A.; Afanvi, A.; Dieudonné, S.; Kassankogno, Y.; Vanhems, P.; Khanafer, N. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among children from primary schools in urban areas of Lomé, Togo. Public Health Nutr 2018, 21, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumena, W.A.; Francis-Granderson, I.; Phillip, L.E.; Gray-Donald, K. Rapid increase of overweight and obesity among primary school-aged children in the Caribbean; high initial BMI is the most significant predictor. BMC Obes 2018, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene-Obong, H.; Ibeanu, V.; Onuoha, N.; Ejekwu, A. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and thinness among urban school-aged children and adolescents in southern Nigeria. Food Nutr Bull 2012, 33, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalskys, I.; Rausch Herscovici, C.; De Gregorio, M.J. Nutritional status of school-aged children of Buenos Aires, Argentina: data using three references. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011, 33, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarp, J.; Jarani, J.; Muca, F.; Spahi, A.; Grøntved, A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and anthropometric reference centiles for Albanian children and adolescents living in four Balkan nation-states. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018, 31, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariqujjaman, M.; Sheikh, S.P.; Smith, G.; Hasan, A.M.R.; Khatun, F.; Kabir, A.; Rashid, M.H.; Rasheed, S. Determinants of Double Burden of Malnutrition Among School Children and Adolescents in Urban Dhaka: A Multi-Level Analyses. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 926571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Z.; Kong, Z.; Jia, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Multiscale Impact of Environmental and Socio-Economic Factors on Low Physical Fitness among Chinese Adolescents and Regionalized Coping Strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, T.; Tariku, A.; Abebe, S.M. Overweight/obesity among school-aged children in Bahir Dar City: Cross-sectional study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2018, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desalew, A.; Mandesh, A.; Semahegn, A. Childhood overweight, obesity and associated factors among primary school children in dire dawa, eastern Ethiopia; a cross-sectional study. BMC Obes 2017, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjari, M.; Amirkhosravi, L.; Hosseini, S.E.; Tavakolinejad Kermani, M.; Abdollahi, F.; Maghfoori, A.; Eghbalian, M. Underweight, overweight, obesity and associated factors among elementary school children: A cross-sectional study in Kerman province, Iran. Obesity Medicine 2023, 38, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; López-Benavente, A.; Tárraga López, P.J.; Yuste Lucas, J.L. Sociodemographic Correlates of Obesity among Spanish Schoolchildren: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children (Basel) 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background characteristics | Categories | n / (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Caregivers/parents Age | 18-25 years | 94(30.4) |

| 26-35 years | 102(33.0) | |

| 36 and above | 113(36.6) | |

| Gender | Male | 146(47.2) |

| Female | 163(52.8) | |

| Family size | 1-4 family size | 142(46.0) |

| 5-8 family size | 94(30.4) | |

| Above 8 families | 73(23.6) | |

| Marital status | Married | 207(67.0) |

| Single | 53(17.2) | |

| Divorced | 29(9.4) | |

| Widowed | 20(6.5) | |

| Educational status | Diploma and above | 189(61.2) |

| 9-12 grade | 62(20.1) | |

| 1-8 grade | 23(7.4) | |

| Read and write only | 18(5.8) | |

| Unable to read and write | 17(5.5) | |

| Occupation | Government | 72(23.3) |

| Private | 108(35.0) | |

| Farmer | 11(3.6) | |

| Merchant | 68(22.0) | |

| Housewife | 50(16.2) | |

| Household income | Low | 88(28.5) |

| Middle | 78(25.2) | |

| High | 143(46.3) | |

| Religion | Orthodox Christian | 141(45.6) |

| Muslim | 75(24.3) | |

| Protestant | 64(20.7) | |

| Others* | 29(9.4) | |

| House owner | Private Owned | 162(52.4) |

| Rent from private | 105(34.0) | |

| Rent from gov't | 42(13.6) | |

| Wealth index | Poor | 85(27.5) |

| Middle | 106(34.3) | |

| Rich | 118(38.2) |

| Characteristics | Categories | n / (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 6-10 years | 154(49.8) |

| 11-14 years | 155(50.2) | |

| Sex | Male | 131(42.4) |

| Female | 178(57.6) | |

| School type | Public school | 172(55.7) |

| Private school | 137(44.3) | |

| Children school grade | 1-4 Grade | 150(48.5) |

| 5-8 Grade | 159(51.5) | |

| Meal frequency | Less than three meal times | 153(49.5) |

| Three and above 3 meal times | 156(50.5) | |

| Dietary diversity score | <4 food groups | 203(65.7) |

| 4 and above food groups | 106(34.3) | |

| Skipping meal | Not skipped | 134(43.4) |

| Skipped | 175(56.6) | |

| Dietary habit | Good dietary habit | 125(40.5) |

| Poor dietary habit | 184(59.5) | |

| Absorption inhibitor | No | 145(46.9) |

| Yes | 164(53.1) | |

| Water supply | No | 122(39.5) |

| Yes | 187(60.5) | |

| Toilet | No | 173(56.0) |

| Yes | 136(44.0) | |

| Wasting | Wasting | 46(14.9) |

| Stunted indices | Stunted | 75(24.3) |

| BMI Indices | Underweight | 111(35.9) |

| Overweight | 58(18.8) | |

| Height for age | Mean±SD | -.78±1.59 |

| BMI for age | Mean±SD | -1.03±2.08 |

| MUAC (mm) | Mean±SD | 194±29 |

| Weight (kg) | Mean±SD | 32.1±9.7 |

| Height (cm) | Mean±SD | 139.8±15.3 |

| Predictor variables | Stunting (Height for age) HAZ<-2SDa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Yes (%) | COR (95%CI) | p<0.05 | AOR (95%CI) | p<0.05 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 103(44.0) | 43(57.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female | 131(56.0) | 32(42.7) | 0.59(0.35,0.99) | 0.046 | 0.69 (0.35,1.38) | 0.297 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 174(74.4) | 33(44.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Single** | 29(12.4) | 24(32.0) | 4.36 (2.26,8.41) | 0.000 | 5.19(2.37,11.4) | 0.000 |

| Divorced** | 18(7.7) | 11(14.7) | 3.22 (1.39,7.44) | 0.006 | 3.15(1.17,8.48) | 0.023 |

| Widowed | 13(5.6) | 7(9.3) | 2.84 (1.06,7.65) | 0.039 | 1.59(0.45,5.57) | 0.469 |

| House owner | ||||||

| Private Owned | 139(59.4) | 23(30.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Rent from private** | 68(29.1) | 37(49.3) | 3.29 (1.81,5.97) | 0.000 | 3.76(1.82,7.79) | 0.000 |

| Rent from gov't** | 27(11.5) | 15(20.0) | 3.36 (1.55,7.25) | 0.002 | 3.86(1.55,9.59) | 0.004 |

| Education level of parents | ||||||

| Diploma and above | 161(68.8) | 28(37.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 9-12 grade** | 41(17.5) | 21(28.0) | 2.95 (1.52,5.71) | 0.001 | 3.60(1.61,8.07) | 0.002 |

| 1-8 grade** | 13(5.6) | 10(13.3) | 4.42 (1.77,11.06) | 0.001 | 4.14(1.46,11.72) | 0.008 |

| Read and write only** | 10(4.3) | 8(10.7) | 4.60 (1.67,12.66) | 0.003 | 4.98(1.49,16.64) | 0.009 |

| Unable to read and write* | 9(3.8) | 8(10.7) | 5.11 (1.82,14.37) | 0.002 | 4.16(1.19,14.51) | 0.025 |

| Child gender | ||||||

| Male | 87(37.2) | 44(58.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Female* | 147(62.8) | 31(41.3) | 0.42 (0.25,0.71) | 0.001 | 0.43 (0.22,0.83) | 0.012 |

| Meal skipping | ||||||

| Not skipped | 115(49.1) | 19(25.3) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Skipped** | 119(50.9) | 56(74.7) | 2.85 (1.60,5.09) | 0.000 | 2.77 (1.35,5.66) | 0.005 |

| Information about nutrition | ||||||

| Awareness | 157(67.1) | 32(42.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Lack of awareness* | 77(32.9) | 43(57.3) | 2.74 (1.61,4.67) | 0.000 | 1.99 (1.05,3.79) | 0.035 |

| Predictor variables | Wasting (MUAC in cm) (Z<-2SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Yes (%) | COR (95%CI) | p<0.05 | AOR (95%CI) | p<0.05 | |

| Parents occupation | ||||||

| Government | 68(25.9) | 4(8.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Private | 86(32.7) | 18(39.1) | 0.28 (0.09,0.87) | 0.028 | 0.35(0.09,1.29) | 0.115 |

| Farmer | 15(5.7) | 4(8.7) | 0.22 (0.05,0.98) | 0.047 | 0.37(0.06,2.24) | 0.277 |

| Merchant | 46(17.5) | 10(21.7) | 0.27 (0.08,0.92) | 0.035 | 0.33(0.08,1.33) | 0.119 |

| Housewife | 48(18.3) | 10(21.7) | 0.28 (0.08,0.95) | 0.042 | 0.51(0.13,2.05) | 0.341 |

| Wealth Index (WI) | ||||||

| Poor | 115(43.7) | 7(15.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Middle | 78(29.7) | 17(37.0) | 0.28 (0.11,0.71) | 0.007 | 0.40(0.13,1.23) | 0.109 |

| Rich** | 70(26.6) | 22(47.8) | 0.19 (0.08,0.48) | 0.000 | 0.19(0.07,0.54) | 0.002 |

| Child age | ||||||

| 6-10 years | 140(53.2) | 14(30.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 11-14 years* | 123(46.8) | 32(69.6) | 0.38 (0.20,0.75) | 0.005 | 0.36(0.16,0.82) | 0.015 |

| Meal skipping | ||||||

| Not skipped | 107(40.7) | 27(58.7) | Ref | |||

| Skipped | 156(59.3) | 19(41.3) | 2.07(1.09,3.92) | 0.025 | 1.57(0.71,3.50) | 0.267 |

| Child DDS# | ||||||

| <4 food groups | 181(68.8) | 22(47.8) | Ref | Ref | ||

| ≥4 and above** | 82(31.2) | 24(52.2) | 0.42 (0.22,0.78) | 0.007 | 0.28(0.12,0.64) | 0.002 |

| Dietary habit | ||||||

| Good DH | 95(36.1) | 30(65.2) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Poor DH** | 168(63.9) | 16(34.8) | 3.32 (1.35,6.39) | 0.000 | 3.18(1.44,7.02) | 0.004 |

| Absorption Inhibitor (AI) | ||||||

| No | 112(42.6) | 33(71.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes** | 151(57.4) | 13(28.3) | 3.42 (1.72,6.80) | 0.000 | 3.87(1.59,9.44) | 0.003 |

| Water Access | ||||||

| No | 114(43.3) | 8(17.4) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes** | 149(56.7) | 38(82.6) | 3.63(1.63,8.09) | 0.002 | 0.15(0.06,0.39) | 0.000 |

| Toilet facility | ||||||

| No | 156(59.3) | 17(37.0) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes* | 107(40.7) | 29(63.0) | 0.40 (0.21,0.77) | 0.006 | 0.45(0.21,0.96) | 0.04 |

| Variables | Underweight (Z<2SD) | Overweight (Z<2SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Yes (%) | AOR (95%CI) | p<0.05 | AOR (95%CI) | p<0.05 | |

| Caregivers/parents Age | ||||||

| 18-25 years | 56(28.3) | 38(34.2) | 0.96(0.50,1.83) | 0.901 | ||

| 26-35 years* | 77(38.9) | 25(22.5) | 0.44(0.23,0.87) | 0.018 | ||

| 36 and above | 65(32.8) | 48(43.2) | Ref | |||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 122(61.6) | 85(76.6) | 0.58(0.19,1.79) | 0.343 | ||

| Single | 39(19.7) | 14(12.6) | 0.36(0.10,1.28) | 0.115 | ||

| Divorced* | 26(13.1) | 3(2.7) | 0.11(0.02,0.59) | 0.010 | ||

| Widowed | 11(5.6) | 9(8.1) | Ref | |||

| Family size | ||||||

| 1-4 family size | 107(54.0) | 35(31.5) | 0.58(0.19,1.79) | 0.343 | ||

| 5-8 family size | 55(27.8) | 39(35.1) | 0.36(0.10,1.28) | 0.115 | ||

| ≥8 families | 36(18.2) | 37(33.3) | Ref | |||

| Meal frequency | ||||||

| <3 meal times* | 89(44.9) | 64(57.7) | 1.83(1.08,3.12) | 0.026 | ||

| ≥3 meal times | 109(55.1) | 47(42.3) | Ref | |||

| School type | ||||||

| Public school** | 152(60.6) | 20(34.5) | 0.35(0.18-0.67) | 0.002 | ||

| Private school | 99(39.4) | 38(65.5) | Ref | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).