Submitted:

23 January 2024

Posted:

25 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

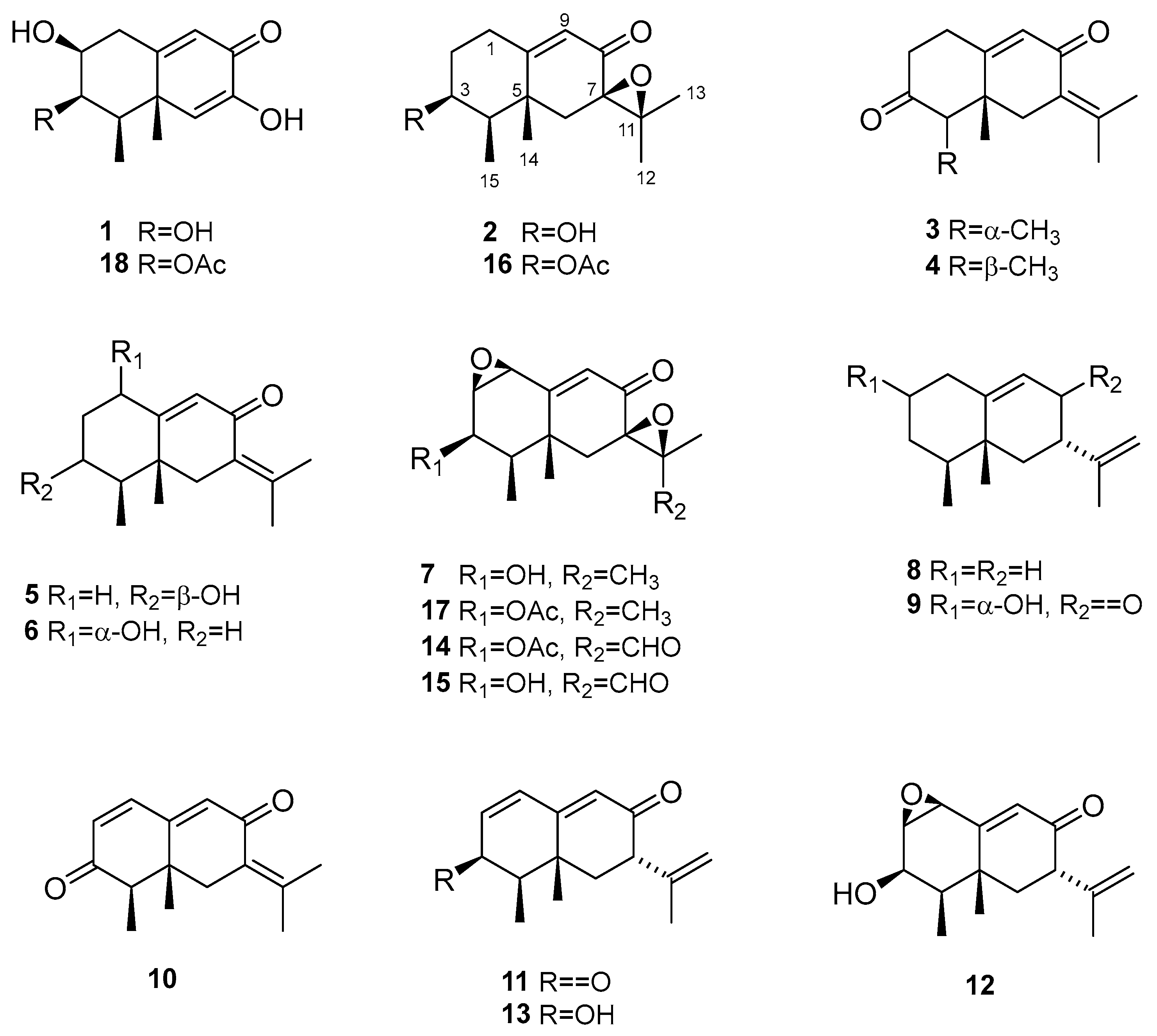

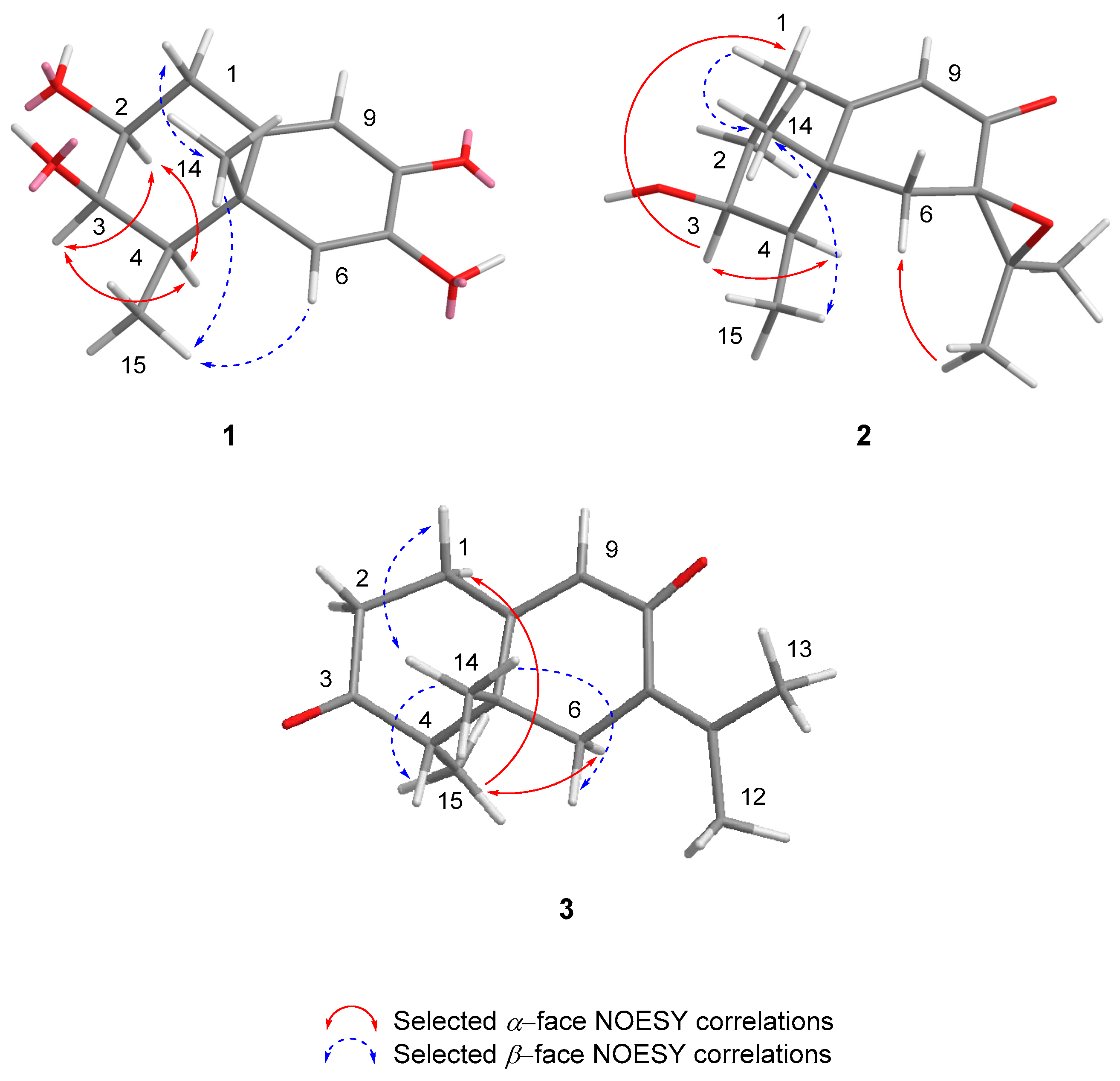

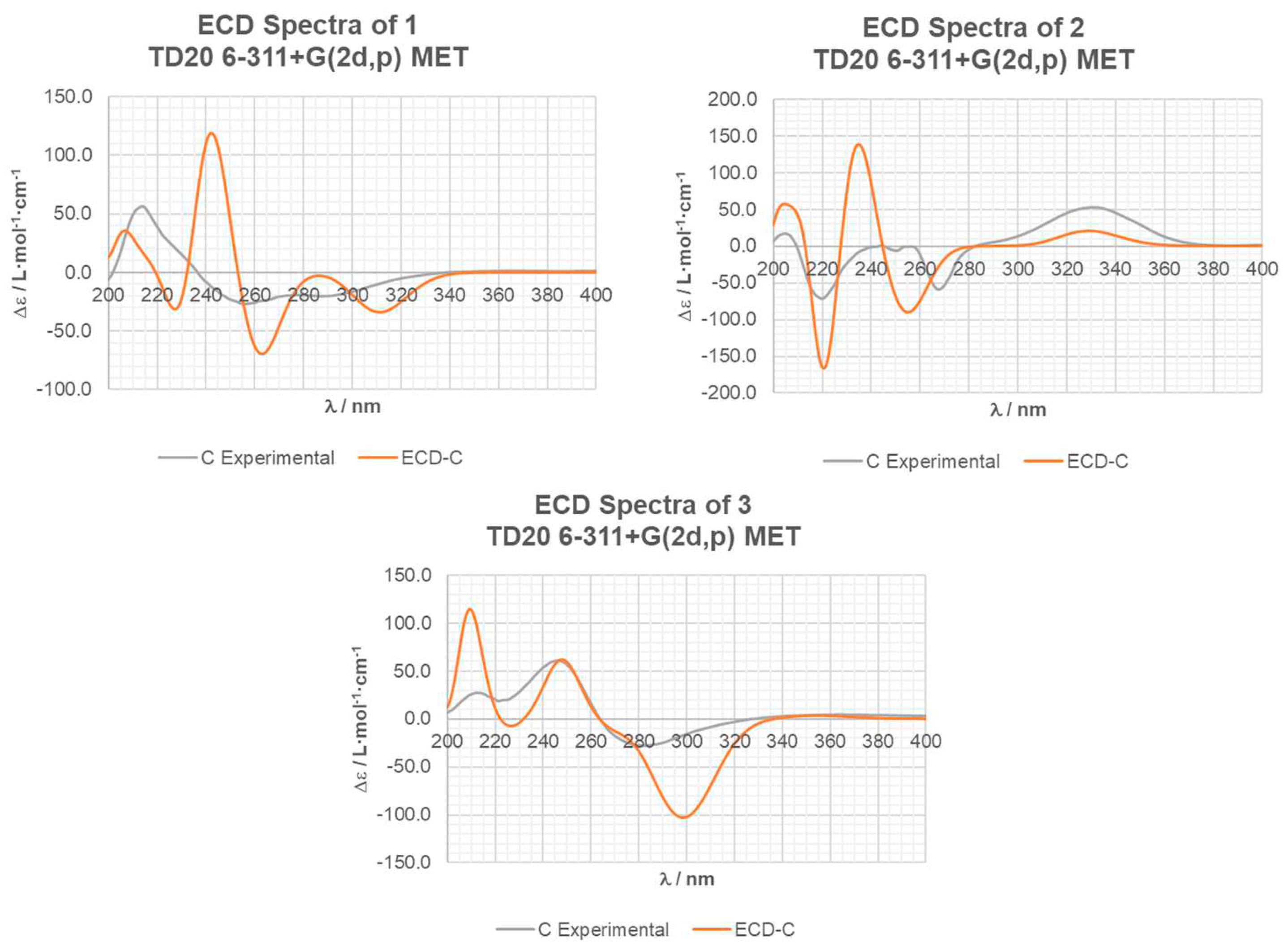

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Fungal Material

3.3. General Culture Conditions

3.4. Surface Culture Fermentation

Czapek-Dox Medium Fermentation

PDB Medium Fermentation

3.5. Shaken Culture Fermentation

Czapek-Dox Medium Fermentation

PDB Medium Fermentation

3.6. Acetylation of compound 15

3.7. Computational Details of EDC Calculations

3.8. In Vitro Antimicrobial Assays

3.9. In Vitro Antitumoral Assays

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, S.; Dufossé, L.; Deshmukh, S.K. Antibacterial metabolites from an unexplored strain of marine fungi Emericellopsis minima and determination of the probable mode of action against Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S.aureus. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 70, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Meng, W.; Cao, C.; Wang, J.; Shan, W.; Wang, Q. Antibacterial and antifungal compounds from marine fungi. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3479–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grum-Grzhimaylo, A.A.; Georgieva, M.L.; Debets, A.J.M.; Bilanenko, E.N. Are alkalitolerant fungi of the Emericellopsis lineage (Bionectriaceae) of marine origin? IMA Fungus 2013, 4, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccaro, A.; Summerbell, R.C.; Gams, W.; Schroers, H.-J.; Mitchell, J.I. A new Acremonium species associated with Fucus spp., and its affinity with a phylogenetically distinct marine Emericellopsis clade. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Vicente, T.F.L.; Esteves, A.C.; Alves, A. Novel halotolerant species of Emericellopsis and Parasarocladium associated with macroalgae in an estuarine environment. Mycologia 2020, 112, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiese, J.; Ohlendorf, B.; Blümel, M.; Schmaljohann, R.; Imhoff, J.F. Phylogenetic identification of fungi isolated from the marine sponge Tethya aurantium and identification of their secondary metabolites. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuvarina, A.E.; Gavryushina, I.A.; Kulko, A.B.; Ivanov, I.A.; Rogozhin, E.A.; Georgieva, M.L.; Sadykova, V.S. The emericellipsins A-E from an alkalophilic fungus Emericellopsis alkalina show potent activity against multidrug-resistant pathogenic fungi. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogozhin, E.; Sadykova, V. A lipoaminopeptaibol secreted by alkalophilic fungus Emericellopsis alkalina demonstrates a strong cytotoxic effect against tumor cell lines. In Proceedings of The 2nd Molecules Medicinal Chemistry Symposium (MMCS): Facing Novel Challenges in Drug Discovery, Barcelona, Spain, 15–17 May 2019; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, A.; Lara, L.; Paz, C.; Perez, A.; Galleguillos, F.; Hernandez, V.; Becerra, J.; González-Rocha, G.; Silva, M. Antibiotic activity of Emerimicin IV isolated from Emericellopsis minima from Talcahuano Bay, Chile. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Saha, S. The genus Simplicillium and Emericellopsis: A review of phytochemistry and pharmacology. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-García, R.A.; Kumar, V.V.; Ariste, A.; Tovar-Herrera, O.E.; Savary, O.; Peidro-Guzmán, H.; González-Abradelo, D.; Jackson, S.A.; Dobson, A.D.W.; Sánchez-Carbente, M. del R.; et al. Simple screening protocol for identification of potential mycoremediation tools for the elimination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and phenols from hyperalkalophile industrial effluents. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 198, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovio, E.; Garzoli, L.; Poli, A.; Prigione, V.; Firsova, D.; McCormack, G.P.; Varese, G.C. The culturable mycobiota associated with three atlantic sponges, including two new species: Thelebolus balaustiformis and T. spongiae. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2018, 1, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virués-Segovia, J.R.; Millán, C.; Pinedo, C.; González-Rodríguez, V.E.; Papaspyrou, S.; Zorrilla, D.; Mackenzie, T.A.; Ramos, M.C.; de la Cruz, M.; Aleu, J.; et al. New eremophilane-type sesquiterpenes from the marine sediment-derived fungus Emericellopsis maritima BC17 and their cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Qu, J.; Ma, S.; Zang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S. Eremophilane sesquiterpenes and polyketones produced by an endophytic Guignardia fungus from the toxic plant Gelsemium elegans. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-C.; Ferreira, D.; Ding, Y. Determination of absolute configuration of natural products: Theoretical calculation of Electronic Circular Dichroism as a tool. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 1678–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamakawa, K.; Izuta, I.; Oka, H.; Sakaguchi, R. Total synthesis of (±)-Isopetasol, (±)-3-Epiisopetasol, and (±)-Warburgiadion. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974, 15, 2187–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.J.W.; Draffan, G.H. Sesquiterpenoids of Warburgia species. I. Warburgin and warburgiadione. Tetrahedron 1969, 25, 2865–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarah, M.W.; Puniani, E.; Sørensen, D.; Blackwell, B.A.; Miller, J.D. Secondary metabolites from anti-insect extracts of endophytic fungi isolated from Picea rubens. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohlmann, F.; Knoll, K.H. Naturally occurring terpene derivatives. 200. Two new eremophilane derivatives from Senecio suaveolens. Liebigs Ann. der Chemie 1979, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S.; Cacan, M.; Lablache-Combier, A. Eremofortin C, a new metabolite obtained from Penicillium roqueforti cultures and from biotransformation of PR toxin. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 2632–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demyttenaere, J.C.R.; Adams, A.; Van Belleghem, K.; De Kimpe, N.; König, W.A.; Tkachev, A.V. De novo production of (+)-Aristolochene by sporulated surface cultures of Penicillium roqueforti. Phytochemistry 2002, 59, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daengrot, C.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Tansakul, C.; Thongpanchang, T.; Phongpaichit, S.; Bowornwiriyapan, K.; Sakayaroj, J. Eremophilane sesquiterpenes and diphenyl thioethers from the soil fungus Penicillium copticola PSU-RSPG138. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. Eremophilane type sesquiterpenoid compound and medical application for treating glioma. China, CN105503556 A, 20 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, S.; Biguet, J.; Lablache-Combier, A.; Baert, F.; Foulon, M.; Delfosse, C. Structures and stereochemistry of the sesquiterpenes of Penicillium roqueforti, PR toxin, and eremofortins A, B, C, D and E. Tetrahedron 1980, 36, 2989–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Wu, G.; Gu, Q.; Zhu, T.; Li, D. New eremophilane-type sesquiterpenes from an Antarctic deep-sea derived fungus, Penicillium sp. PR19 N-1. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, R.; Borrelli, V.; Iacobellis, N.S.; Basile, G. Preparation of derivatives of phomenone and PR toxin to study structure-biological activity correlations of eremophilanic sesquiterpenes. Ann. della Fac. di Sci. Agrar. della Univ. degli Stud. di Napoli, Portici, IV 1986, 20, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R.; Schnoes, H.K.; Hart, P.A.; Strong, F.M. The structure of PR toxin, a mycotoxin from Penicillium roqueforti. Tetrahedron 1975, 31, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.J.P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods V: Modification of NDDO approximations and application to 70 elements. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 1173–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauernschmitt, R.; Ahlrichs, R. Treatment of electronic excitations within the adiabatic approximation of time dependent density functional theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 256, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casida, M.E.; Jamorski, C.; Casida, K.C.; Salahub, D.R. Molecular excitation energies to high-lying bound states from time-dependent density-functional response theory: Characterization and correction of the time-dependent local density approximation ionization threshold. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 4439–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancès, E.; Mennucci, B.; Tomasi, J. A new integral equation formalism for the polarizable continuum model: Theoretical background and applications to isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 3032–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennucci, B.; Cancès, E.; Tomasi, J. Evaluation of solvent effects in isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics and in ionic solutions with a unified integral equation method: Theoretical bases, computational implementation, and numerical applications. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 10506–10517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ravipati, A.S.; Koyyalamudi, S.R.; Jeong, S.C.; Reddy, N.; Bartlett, J.; Smith, P.T.; de la Cruz, M.; Monteiro, M.C.; Melguizo, Á.; et al. Anti-Fungal and anti-bacterial activities of ethanol extracts of selected traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2013, 6, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Position | δH, Mult (J in Hz)a | δC, Typeb | δH, Mult (J in Hz)c | δC, Typed | δH, Mult (J in Hz)e | δC, Typed |

| 1α | 2.45, dd (12.0, 4.5) | 37.5, CH2 | 2.16, m | 28.0, CH2 | 2.55, m | 29.0, CH2 |

| 1β | 2.90, td (12.0, 1.5) | 2.90, m | 2.87, dddd (14.7, 11.3, 7.6, 1.8) | |||

| 2α | 3.53, ddd (12.0, 4.5, 3.2) | 74.6, CH | 1.67, m | 37.2, CH2 | 2.19, ddt (14.2, 4.7, 2.3) | 37.4, CH2 |

| 2β | - | 2.16, m | 2.50, m | |||

| 3α | 3.70, td (3.2, 3.0) | 74.1, CH | 3.97, brs | 70.8, CH | - | 212.1, C |

| 3β | - | - | - | |||

| 4 | 1.41, qd (7.0, 3.0) | 43.4, CH | 1.75, qd (7.1, 3.3) | 43.7, CH | 2.60, qd (7.0, 3.3) | 53.6, CH |

| 5 | - | 45.0, C | - | 42.2, C | - | 42.2, C |

| 6α | 6.30, s | 127.4, CH | 2.08, d (15.0) | 38.1, CH2 | 2.34, d (15.0) | 37.5, CH2 |

| 6β | - | 1.99, d (15.0) | 2.49, d (15.0) | |||

| 7 | - | 147.9, C | - | 65.6, C | - | 127.0, C |

| 8 | - | 183.9, C | - | 195.2, C | - | 190.5, C |

| 9 | 6.17, d (1.5)- | 124.4, CH | 5.92, d (1.3)- | 123.6, CH | 5.90, d (1.8)- | 128.2, CH |

| 10 | 171.1, C | 172.4, C | 162.6, C | |||

| 11 | - | - | - | 64.7, C | - | 146.1, C |

| 12 | - | - | 1.41, s | 21.3, CH3 | 1.85, d (1.4) | 23.1, CH3 |

| 13 | - | - | 1.30, s | 19.1, CH3 | 2.15, d (2.0) | 22.8, CH3 |

| 14 | 1.35, s | 22.0, CH3 | 1.36, s | 24.5, CH3 | 1.20, s | 25.1, CH3 |

| 15 | 1.28, d (7.0) | 13.2, CH3 | 1.15, d (7.1) | 12.6, CH3 | 1.10, d (7.0) | 11.0, CH3 |

| MIC (µg/mL) | ||||||||

| Compound | A. fumigatus ATCC46645 | C. albicans ATCC64124 | K. pneumonia ATCC700603 | E. coli ATCC25922 | MSSA ATCC29213 | MRSA MB5393 | A. baumannii ATCC19606 | P. aeruginosa PAO-1 |

| 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| 3 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| 11 | >24 | >24 | >24 | >24 | >24 | >24 | >24 | >24 |

| 15 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| IC50 (µM) | |||||

| Compound | HepG2 | MCF7 | A549 | A2058 | Mia PaCa-2 |

| 1 | >45 | >45 | >45 | >45 | >45 |

| 3 | >172 | >172 | >172 | >172 | >172 |

| 11 | >33 | >33 | >33 | >33 | >33 |

| 15 | 7.6 (6.8-7.9) | 4.7 (4.0-5.4) | 14.7 (12.6-17.3) | 12.2 (10.8-14.0) | 2.5 (2.2-2.9) |

| Doxorubicin | 0.21 (0.19-0.23) | 0.21 (0.16-0.28) | 0.90 (0.70-1.00) | 0.10 (0.08-0.13) | 0.43 (0.36-0.50) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).