1. Introduction

All civilizations understand the necessity to safeguard their family members from social risk-related income loss [

1]. This is because the right to social security is recognized as a fundamental human right by international legal treaties such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 22) [

2], and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (article 9 and 10) [

3]. However, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reported that nearly 5.1 billion people, or 75% of the global population, do not have access to social security [

4]. While social security is comprehensive (including provisions for old age) in industrialized countries (mostly members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have a trivial coverage of less than 10% of the population to only a few contingencies (e.g., old age, disability, survivorship) [

5].

Meanwhile, the older population is continually growing globally. The older population over 60 age is predicted to increase to 2.6 billion by 2050, up from 600 million in 2000 [

6,

7]. This rapid population expansion of the older population will not exempt countries in Africa and Asia. For example, the proportion is projected to go to halving levels in sub-Saharan Africa. The World Health Organization has predicted that by the year 2050, 80% of older people will live in low- and middle-income countries [

8]. One in four Asians will reach 60 by 2050; meanwhile, in countries like Sub-Saharan Africa, the number of people over 60 will triple from 53 million in 2009 to 150 million by 2050 [

9].

The World Bank reported that around one in five low-income countries lack a safety net for the older, while most family members serve as their primary social safety net [

10]. Several studies have predicted that an ageing population will adversely affect the quality of life in resource-poor countries of Africa and Asia in the future [

11,

12]. In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports a high prevalence of disability among older people in rural areas of low and middle-income countries, such as Ghana, Pakistan and Myanmar, due to their economic and social circumstances [

13]. It is also noted that communicable diseases are prevalent among the older as a part of the global disease trend, particularly among the older in the global south [

14]. This suggests that as most older people become susceptible to chronic diseases, their conditions may warrant various support, including pension schemes. In fact, the pension system is an integral part of political economy of overall planetary wellbeing which minimizes the social and financial inequality and ensures access to safe water, sanitation, and healthcare for all. However, the older population in Global South are vulnerable due to dwindling resource, and considerate pension schemes are essential for both formal and informal older adult workers. As part of these state-managed contributory pension plans, employees are able to prepare for retirement and increase their retirement income security [

15]. Most importantly, at a time when there has been a change in family dynamics due to globalization, and people are migrating worldwide in search of jobs, businesses, marriages, and higher education, which affects the family role as a social safety net to older people. The provision of pensions is in reaction to seeking alternatives for extended family assistance, which has sustained society in times of need and catastrophe [

16]. Pensions are the most frequent social protection for workers.

This research holds significance because Ghana, Myanmar, and Pakistan employees have different savings habits than those in other countries [

17,

18,

19]. The socio-economic indicators of these countries position them as low-middle income countries with similar development indicators and Human Development Index. Due to this, there is a strong emphasis on public sector employees in designing these countries’ pension systems for the older population. Other demographics, such as young people, women, and public sector employees, have been prioritised in social policy to the detriment of older populations. The most significant difficulty for these countries has been developing long-term social programmes that account for their growing elderly population. Research has also demonstrated that the level of formal social protection for older people varies widely among countries with middle incomes, ranging from hardly any assistance to elaborate programmes that can compete with those in the global north [

20]. Studies have noted that increased pension spending in many countries is often followed by substantial pensioner insecurity due to higher rising life expectancy and a lower birth rate [

21]. Moreover, policymakers and scholars have debated the type of pension plan that applies to individual countries and demonstrated the need to support older people in society as ageing is unavoidable, which is crucial for many governments around the globe [

22,

23]. Despite this, no sufficient comparative, large-scale research has been conducted on implementing pension schemes and policy gaps involving African and Asian nations. While some research has attempted to compare pension programmes, a comparative study including two large continents with expanding older populations is still lacking. Important questions still have to be answered. Against this backdrop, this study analyses the existing pension schemes for older adults in Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar to understand the current pension policies in these countries with their implementation challenges and policy gaps. This study will therefore contribute to the existing pension scheme debates and policy discourse in these countries. This study aims to answer the following question;

What pension programmes exist for older adults in Ghana, Pakistan and Myanmar?

What are the trichotomies and dichotomies in these pension programmes in Ghana, Pakistan and Myanmar?

What are the implementation issues and policy gaps in these countries’ pension schemes?

2. Literature Review on Existing Pension Policies for Older Adults

We present below a review of current pension schemes available and their modes of operation in the three countries:

2.1. Country Profile- Ghana

The population of Ghana is around 32 million [

24]. The older population in Ghana is estimated to reach 2.5 million in 2025 and 6.3 million by 2050 [

25]. The majority of older people live in rural areas, and there is a higher proportion of females over the age of 65 than males [

26]. Some studies noted that the decline in natality and improvements in public health, hygiene, sanitation, and nutrition has resulted in the ageing of the Ghanaian population [

27,

28]. There has been a recent uptick in advocacy in Ghana for expanding access to social protections for those in the informal sector [

29]. The fact that the vast majority of Ghana’s working population is employed in the informal sector has piqued public attention since the entitlement to social protection is not yet a reality for them [

30]. Because of this, the Informal Sector Social Security Scheme was established by the Social Security and National Insurance Trust Fund (SSNIT) in 2005 [

31]. However, there was hardly any participation from the labour force [

32]. In 2009, the government passed the National Pensions Act, Act 766, which established a third-tier pension system by integrating obligatory and voluntary retirement plans in an effort to address diminishing investment returns and, in particular, to enhance access to the informal sector [

33]. Over a decade has passed since the implementation of the third-tier pension system, yet the challenge of fulfilling the programme’s original intent to provide a complete and well-organised retirement plan has persisted. This is recognised because informal sector employees consistently show poor patronage and understanding of the new pension system [

34,

35,

36].

2.1.1. The Three-Tier Pension Scheme and Mode of Operation in Ghana

The Ghana pension scheme was upgraded to a three-tier pension scheme in 2008. The employer contributes 13 %, and the employee contributes 5.5 %, for a combined fund contribution of 18.5 %. The retirement plan benefits include a monthly pension income, a lump sum payout, invalidity benefits, survivor benefits, and a favourable National Pension Regulatory Authority tax exemption on assets [

37,

38]. Ghana’s pension scheme consists of two mandatory schemes and one voluntary scheme under the National Pension Act 2008 [

39,

40] and each with its objectives as the following:

As part of the First Tier, the SSNIT administers a mandatory Basic National Social Security Scheme (BNSSS) for both the public and private sectors. This second tier is a mandatory occupational pension plan that pays a lump sum to all workers on the formal labour market. In both the first and second tiers, contributions are mandatory and deducted from an individual’s basic pension pay; however, each tier operates differently. Governments manage the first tier through the SSNIT, whereas private operators manage the second tier.

Thirdly, informal workers are encouraged to participate in voluntary pension funds and to set up personal pension plans funded by tax benefits. Third-tier voluntary individual pension plans are designed specifically for employees in the informal sector. Those in the formal sector who wish to contribute to their pension benefits have access to a separate fund. Furthermore, this voluntary scheme allows individuals to open new or additional pension funds to complement their mandatory pension schemes. The National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA) regulates pension schemes on behalf of the state. As part of its mandate, the institution licenses pension fund managers and monitors their performance.

2.2. Country Profile-Pakistan

Pakistan is home to 231.9 million people, 2.83% of the world’s population [

41]. Approximately 4.3% of the population of Pakistan was 65 years and older in 2022. The proportion of people aged 65 and over in Pakistan increased from 3.3% in 1973 to 4.3% in 2022, representing an annual increase of 0.51% [

42]. Despite the low older population, only 3 % of the older person received some pension [

43]. The population growth rate in Pakistan is 2.4, higher than in the neighbouring countries. People over the age of 60 are expected to grow to 43.3 million by the year 2050, accounting for approximately 15.8 %of its population [

44]. The increased life expectancy and population growth in Pakistan have increased the number of older persons dependent on government assistance. The existing dependency ratio of over 65% increases demands on healthcare and pension contributions [

45].

Pensions in Pakistan are limited to employees of the formal sector, excluding those who are employed in the informal sector. Since its inception in 1947, it has undergone many changes. Currently, the following are the eligibility criteria and benefits of the current Pakistan pension scheme:

A person over the age of 60 is only eligible for pension schemes if they have served for 25 years, and voluntary retirement is permitted

A person who has served for 30 years is entitled to receive 70% of their last drawn pay as a pension. Nevertheless, if the service is less than 30 years, the drawn payment will be based on the service experience

35% of gross income is given as commutation

To qualify for the pension scheme, retirees must have contributed a certain percentage of their salary while in service.

In addition to the above benefits, gratuities, family pensions, mandatory contributions in the general provident fund, benevolence fund survivor benefits, group insurance life insurance, and access to medical facilities [

46]. Employees Old-Age Benefit Institutions (EOBI) are maintained at the federal level, while Employees Social Security Institutions (ESSI) are maintained in each of Pakistan’s four provinces [

47]. Putting the Pakistan pension scheme in the world bank model shows in

Table 1 below.

2.3. Country Profile-Myanmar

Myanmar is a Southeast Asian country surrounded by India, Bangladesh, China, Laos, and Thailand. The current population of Myanmar is 55 million, and the life expectancy is 67.78 years [

49]. The older population over the age of 60 constituted more than 5,236,716 people in 2018, accounting for 9.7 % of the total population. The number is expected to rise by 11 million by 2050, accounting for 21.4 % of the total population [

50].

Myanmar has two types of pensions: Social Pensions and Civil Service Pensions. The term “social pension” refers to a pension provided to a general civilian who does not serve in public service or government. The Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief, and Resettlement 2017 introduced a social pension for the general population. Social pensions were available to older persons over the age of 90 and above and were paid at a rate of 10,000 Kyat (local currency) per month or USD 8 per month during the 2017-2018 fiscal year [

51]. The government allocated a budget for social pensions during the 2017-2018 fiscal year of 420 million kyats, and more than 32000 eligible applications were distributed [

52]. Nearly 168,000 older individuals aged 85 were entitled to a social pension in the 2019-2020 fiscal year. Reports indicate that the government spent 72.244.4 Kyat billion on social pensions in 2017-2018 and 5 billion in 2018-2019 [

53].

2.4. Summary of the Literature

The literature review on the various existing pension schemes in the three selected countries has revealed that with different population sizes and national economic strength in each country, public pension plans come in various forms, including direct financial investment from the governments, joint contributions from the governments and individuals, little private pension schemes among others. The literature also showed that different public pension plans have different requirements for national finance, personal income, family economic status and the general working population. Building on the arguments in the literature regarding the different types of pensions in the three countries, we used the theory of change model to analyse how pension schemes operate in the three countries and their outcomes on older populations.

2.5. Theoretical Framework-Theory of Change

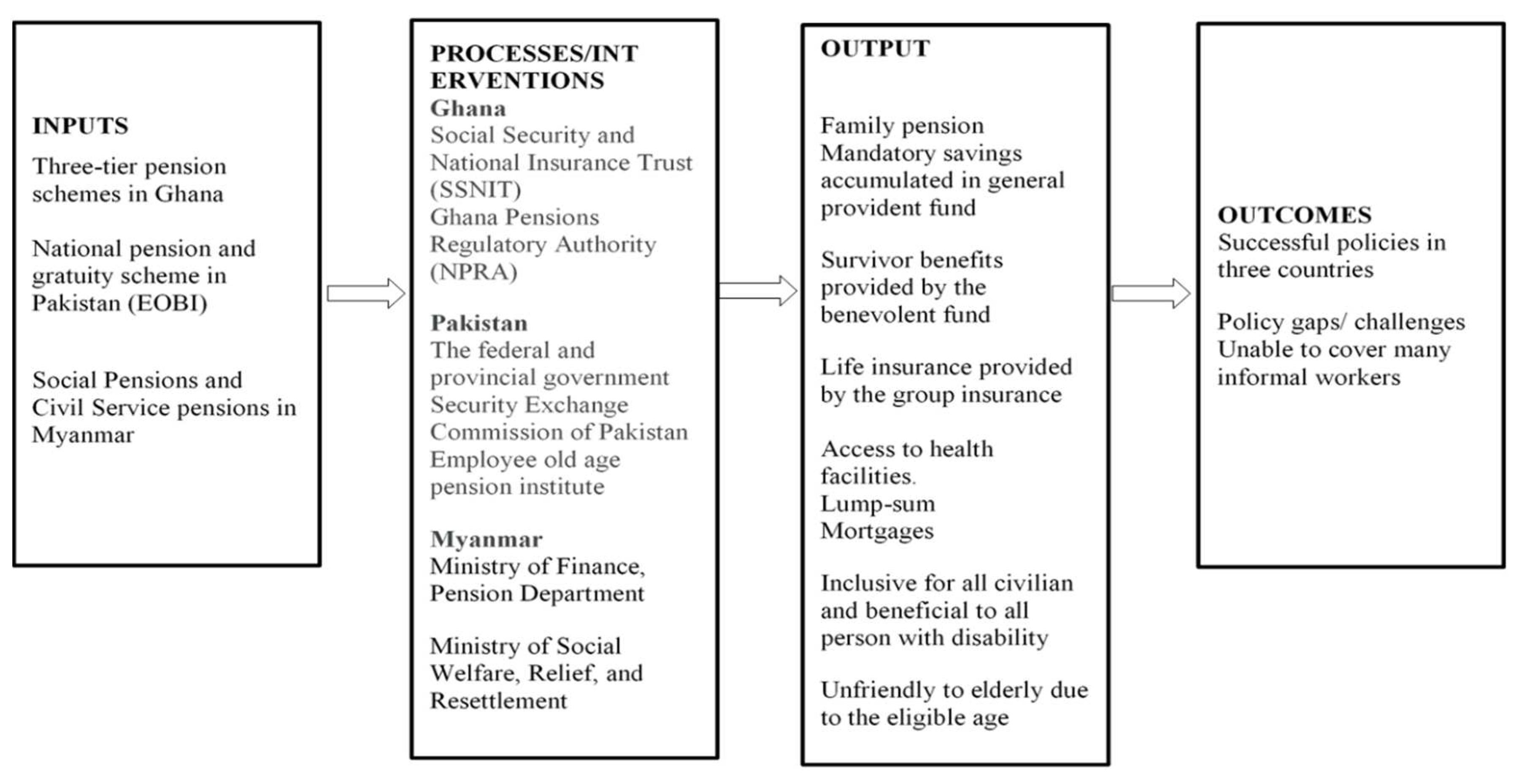

Retirement decision-making, retirement transition, and retiree satisfaction have been the subject of numerous theoretical arguments. Some of these theories include disengagement theory, the life course perspective, and role theory. Much research has been done on retirement, but not much on the theoretical postulates of comparative pension research. Therefore, this research used a theory of change to analyse the pension schemes for older people in Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar. The cases shown in

Figure 1 demonstrate how the theory of change (input, output, and result) in policy analysis may be implemented in practice.

This theory was applicable to the study because the study aims to examine existing pension schemes and how such projects contribute to the anticipated target or consequence through a series of intermediate outcomes. A theory of change is commonly used in policy assessments, forming the basis of theory-based evaluations [

54,

55,

56,

57]. The model clearly states that if [inputs] and [activities or processes – interventions] result in [outputs], then [outcomes] should be generated, resulting in [results]. In other words, “results” refer to outputs, consequences, and impacts that directly impact well-being. Intervention refers to a particular procedure or intervention that results in a significant change in the results and impacts concerned. For this study, the theory was selected due to its ability to examine the implementation of pension schemes in Ghana, Pakistan and Myanmar to determine their outcomes. We believe that the kind of pension policy inputs and processes will determine its significance on the elderly population and its implementation challenges and gaps.

Figure 1 and

Table 2 illustrate this.

Figure 1 and

Table 2 show that all employees in the three countries can access pension schemes. There are three tiers of pension schemes for workers in Ghana, whereas the EOBI is available in Pakistan. In Myanmar, two pensions are available to older adults: Social Pensions and Civil Service Pensions. Several government regulatory systems have been created to ensure the smooth operation of pension plans in the three nations, leaving little to no involvement for the private sector in pension administration. Ghana’s pension system is governed by the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SNNIT) and the Ghana Pensions and Regulatory Authority. Pensions in Pakistan are governed by the Security Exchange Commission and the Employee Old Age Pension Institute, both branches of the federal and provincial governments. The Ministries of Finance and Social Welfare, Relief, and Settlement govern pensions in Myanmar. In all three countries, the processes and institutions ensure smooth operation and successful implementation of these schemes. Depending on each country’s pension system specifics, older people may benefit in various ways. This is because public pension plans come in various forms, including direct financial investment from the governments, joint contributions from the governments and individuals, etc. The successful implementation of the schemes has resulted in benefits for beneficiaries, including family pensions, required contributions accrued in the general provident fund, survivor benefits provided by the benevolent fund, life insurance provided by community insurance, access to health services, lump sums of money, and mortgages. Consequently, many informal workers are left out in the cold when it comes to pension policy-making in the three countries.

3. Materials and Methods

Our study is based on existing literature and document analysis in the three countries. Document analysis is a systematic method for assessing and evaluating both printed and electronic documents. Documents analysis was used, as with other qualitative methods, as it consists of examining and interpreting data to extract meaning, gain understanding, and generate empirical findings [

59,

60]. The use of documents can provide valuable information and insights that can be used to expand one’s knowledge base [

61]. In this study, we reviewed government documents along with 28 available articles focusing on pension and social security for older people in the three countries.

Table 3 below outlines the various documents analyzed and the articles reviewed.

In accordance with the study objectives, we thematically analysed on what are the existing pension policies available in the three countries, what they focus on, their selection criteria and the benefits those pension schemes and social security schemes cover, whether such projects are run by the government or the private sector along with the implementation challenges and gaps exist in these policies and documents.

4. Results

4.1. Type of Pension Schemes and Social Security Plans in the Three Countries

4.1.1. Ghana

The previous Ghanaian pension scheme had an age requirement before the current three-tier pension system was introduced. Although the minimum/maximum age for participation in social security has been raised, the minimum/maximum age for participation remains unchanged. The existing age limit of 20 years has been reduced to 15 years, with a new maximum age of 45 years. Furthermore, future lump-sum pension payments may be used as collateral to purchase a home before retirement, allowing workers to protect mortgages. Additionally, it will enable companies to leverage their pension schemes across the second and third tiers of systems, all of which are privately managed. Since no arbitrary withdrawals are permitted, it encourages funds to grow, enables individuals to know how much payment they will receive each month, and facilitates the procedures for determining retirement payouts. Furthermore, the scheme appears to provide the opportunity for contributors to feel that they are part of the whole implementation process, which promotes trust in the scheme’s functioning.

Furthermore, despite the many advantages and changes in the current three-tier pension plan, the system still faces some challenges and policy concerns. For example, many low-income individuals cannot participate and reap the benefits of old age because of poverty. Few conservatives oppose the policy. Moreover, there is no provision for overseas citizens to contribute voluntarily to the program to receive benefits upon their return to the country. The registration and certification of trustees, pension fund managers, and customs officers also present a problem [

62,

63]. A concern is the mismanagement of individual contributions by the NPRA’s management [

64]. The NPRA has been unable to implement Ghana’s three-tier pension structure completely.

4.1.2. Pakistan

As in most countries, the Pakistani government manages pensions for the older and allocates payroll funds according to the pay-as-you-go (PAYO) method. Across the globe, such a system is characterised by significant constraints [

65]. In addition, Pakistan’s PAYO system is a major hindrance to economic development [

46]. Pensions are not provided to the entire older population in Pakistan. Due to this, older people are heavily dependent on their family members and children’s support. In addition, a collapse of the government would be a significant burden for the government. The informal sector does not have a strong market for private annuities, resulting in an imbalance and a massive divide between the public and private sectors. Public sector employees receive generous pensions, whereas private sector workers do not. Although some proposals, such as voluntary pension systems and parametric reform, have been announced at the rhetorical stage, they have yet to be implemented. Pakistan has a huge informal sector, including agriculture which the government can capitalise on by introducing policies which will help the government to generate revenues as well as provide a social safety net to the workers in the informal sectors [

66]

4.1.3. Myanmar

The older population in Myanmar face longevity risks when accessing pension benefits. Generally, longevity risk is the uncertainty surrounding the older average death rate. This is because the older population are eligible for pensions at 865. Approximately 168,000 older people over the age of 85 were eligible for a social pension in fiscal years 2019-2020 with a monthly payment of 10,000 Kyat (local currency) or

$8 per month [

67]. Thus, even if population ageing controls, thus maintaining life expectancy at 65 for the near future, the older will still face a prolonged period of uncertainty regarding their entitlement to pension benefits. There are some older people who are unlucky and die before they can receive their pension benefits.

5. Similarities and Differences in the Three Countries’ Elder Pension Schemes and Social Security Plans

As we compare the three pension plans, we observe certain similarities. For example, all pension plans protect formal jobs, and informal jobs have fewer opportunities. For example, Pakistan’s EOBI serves the private sector. In contrast, Ghana’s SSNIT and the Social Pension in Myanmar are intended for a general civilian who does not necessarily need to have served in a public service or government sector. Additionally, the age at which one can access a pension varies in the three countries. In Ghana and Pakistan, the eligibility criteria for access to older people is 60. However, Myanmar differs in that it has eligibility criteria of 85 years of age. Ghana offers lump-sum pensions, Pakistan offers pensions and commutations of 70% of current wages, and Myanmar offers monthly pensions. Moreover, Pakistan has additional benefits and pension plans, which are not reflected in the pension systems of Ghana and Myanmar.

6. Implementation Challenges and Policy Gaps

Our analysis shows that the existing pension policies and security plans focus more on the formal sector, leaving space for the informal sector. Pakistan has a weak pension provision like other countries, and older people rely on family support and the next generation for support in their old age. The existing pension scheme requires a huge budget and political will, which seems quite challenging currently [

68,

69]. Similarly, in Ghana, it is observed that broad dissatisfaction with retirement income replacement levels and concerns connected with institutional fragmentation existed against a backdrop of a variety of challenges. Also, no provision for overseas citizens who wish to voluntarily contribute to the program to be eligible for benefits when they return in old age. The registration and certification of trustees, pension fund managers, and customs officers also presents a problem. The "National Basic Social Security Scheme" (SSNIT) [

70] is the first tier of social security, and its participation is required for all employees in the formal sector (public and private), but voluntary for the self-employed and those in the informal sector. The program is self-sustaining, funded by a combined contribution from employers and employees.

The second tier is an occupational pension program with a defined contributions structure that is privately administered. Managers in this tier compete for the right to oversee the investments made with employee contributions or on their behalf, following the free market principles. In the third tier, members are offered tax breaks to join a private pension plan that is entirely voluntary. The second tier is meant to supplement the primary curriculum, and so is the upper tier.

Contributions made to retirement plans in the second and third tiers are invested by pension fund managers according to strict guidelines established by the Trustees. However, they do not have control over or access to any retirement funds.

Consequently, some institutions play a role in the governance structure of the Ghanaian pension system. Retirement benefit levels may be negatively impacted, however, if various parties are involved in managing employees’ retirement funds. Similarly, Myanmar has a longevity challenge, which means most elders die before they reach the pension entitlement. The informal sector is a neglected part of the pension scheme.

In all three countries, government collaboration and partnership with private firms to properly institutionalise pension schemes and reforms to cover the majority of workers is lacking. Governments in the three countries lack the capacity to check private firms pension plans for their workers properly. Governments also contribute little to private pension funds.

7. Discussion and Policy Implications

The study has revealed that Government pension programmes come in various forms, including direct financial investment from the governments, joint contributions from the governments and individuals, etc. Different public pension plans have different requirements and implications for national finance, personal income, family economic status, and older populations in the three countries. Governments commitments to the informal sector and private workers is low, which may have implications on national development and the general well-being of workers, particularly older adults. Since the majority of the active working populations are found in the informal and private sectors, it depicts that low pension coverage will mean low tax contributions, which may hamper the development of the countries. The governments of Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar must ensure their Ministries, Departments, and Agencies prioritise elder pensions, especially for older persons who work in the informal sector. A comprehensive and holistic national plan would be required to address this social issue as a development metric. A two-generation approach would be necessary to guide the formulation and implementation of pension policy. The implications are that pension policies and programs must consider both formal and informal workers simultaneously. A two-generation strategy is essential rather than optional since an individual’s well-being while working is intrinsically linked to their well-being after retirement. The various Acts and similar legislation in respective countries often stipulate that various government institutions will implement programs and policies to provide all pension benefits. However, these programs are not developed holistically and benefit some categories of older populations. This study suggests that a single governmental entity should be responsible for elder welfare, providing policies, programs, and services such as pension benefits.

8. Policy Suggestions for the three countries

After analyzing the three pension schemes, although Ghana, Pakistan and Myanmar differ significantly in terms of population sizes, GDP and investment levels, we propose policy guidelines to the governments and agencies so that coverage can be improved and enforced effectively. To ensure that a pension scheme enhances elder security is sustainable and does not adversely impact workforce incentives and income distribution, it is essential to consider both pension benefits and financing simultaneously. Therefore, we suggest the following:

Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar do not require a complete overhaul of their pension programmes, but they will need to expand upon the existing pension plans they already have in place. It is recommended that policymakers in the three countries broaden the coverage of old-age pensions to include all older people, including those in the informal and private sectors. Thus, policymakers must assess the relative size of the formal sector versus the informal sector, the public versus private sector, and the degree to which the country’s financial institutions and markets have developed. These factors will affect the wide range of options available for financing and determining cash benefits, as well as how pension payments and reserve funds can be productively invested.

Pakistani authorities must reform the country’s pension system to achieve an effective, equitable, and ethically desirable social security system. Create a pension fund to regulate it and abandon the conventional care method to encourage more labour and savings.

In Ghana, the government must provide some tax deductions for those who contribute to retirement funds, whether employers or individuals.

Tax-deductible benefits are available to Pakistani citizens. The results would be improved by ongoing and productive co-operation between all stakeholders. Additionally, fund managers, custodians, the NPRA, and SSNIT must make sure that the government, politicians, and employers are implementing the duties, obligations, and sanctions required to achieve the scheme’s target.

It is necessary to improve public education and sensitisation to understand the policy and increase enrolment fully. Financial literacy and information sharing about how the pension system works are essential for individuals. Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar have a tradition of emphasising the individual’s decision regarding how pension contributions are invested and when the pensions (annuities) are first paid. While these concerns are most frequently associated with defined contribution plans, they are also critical to the inclusive and transparent operation of defined benefit plans, particularly when early retirement decisions are needed [

71].

In connection with the above, the information demands of older persons and how such information might be effectively communicated must be carefully considered [

72]. Evidence from the OECD indicates that information should be made available to scheme members in general, with more comprehensive information available upon request. The dissemination of information, however, is not sufficient in and of itself. Financial education and community-based assistance may be required to reach hard-to-reach communities effectively. Developing countries like Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar, where access to old-age pensions is limited, can improve their financial literacy and awareness of pensions by shifting from day-to-day planning to long-term planning [

73]. Pension scheme members who have investment options are exposed to significant risks. The potential for financial (welfare) losses because of such risks may justify arguments in favour of restricting individual choice in some cases [

74].

Pakistan’s current pension system focuses on fixed benefits provided to employees without using a pension fund. Allocating the annual budget is the responsibility of the government for all expenditures. Moreover, the pension is not systematically indexed to keep pace with market inflation; it is merely increased by a small amount, barely sufficient to control retirees’ daily expenditures. Therefore, the pension scheme agreement should be converted into a fixed contribution plan to minimise the scheme’s financial burden. There have been numerous complaints against EOBI for attacking people and mishandling their information. In this regard, it is crucial to strengthen the supervisory and control mechanisms [

75].

9. Common Policy Lessons the Three Countries Can Adapt

In these three countries, where the "self-employed" under the informal and private sectors may constitute the majority of the working population, it is essential to pay particular attention to the demands of these workers. Regardless of governments’ efforts to ensure mass inclusion, the self-employed have difficulty receiving coverage under contribution social security programmes because of their more personal work and earnings patterns, making it difficult to accommodate their needs within predetermined contribution collection strategies designed for large-scale employer-employee relationships. It would benefit governments in these three countries to learn from Argentina’s monotributo strategy, which uses a single unified payment to cover tax and social security contributions as an alternative method of collecting contributions from small irregular contributors working in the informal sector [

5]. Uruguay has a contribution system like that of the United States. Other options that these three countries can consider include subsidising contribution levels and providing more flexibility in circumstances to allow contributions to be paid based on unpredictable income flows, including seasonality [

5].

10. Conclusions

The study findings provide a comparative policy perspective of two different continents’ older pension schemes, which serve as a foundation for further analyses of pension policy and further pension debate in such settings. According to the findings of this study, pension schemes and other forms of social security for informal workers are insufficient to safeguard older and near-retirement workers. The analysis reveals that pension schemes cover only a small portion of the pension-eligible older in the public sector and do not cover most older population employed in the informal sector and private sectors in the three countries. Several policy gaps exist in the three countries, which need policy adaptation and lessons from other countries. A significant proportion of the older population in these countries will continue to experience a gap in pension coverage for the older population if no action is taken to bridge this gap. Therefore, the design of a pension scheme in these countries must consider the changing environment. It is necessary for a system to be flexible, the inclusion and extension of pension coverage to workers in the informal and private sectors.

11. Limitations

This study used the documentary analysis design to study three pension schemes in Ghana, Pakistan, and Myanmar. Our study method prevented us from covering all government documents and publications regarding pension plans in the three countries. This would not have been the case with a systematic literature review. The only sources we used for our research were recent papers, government pension schemes reports and articles about pension plans in the three countries. The research findings may not have covered all government pension policy documents.

12. Suggestions for Future Research

Future research may investigate this issue through a systematic review to enhance the reliability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, TSK, NOJ, AWK, MA; Methodology, TSK, NOJ, AWK; Formal Analysis, TSK, NOJ, AWK and MA; Validation, TSK, NOJ, AWK and MA; Resources, MA; Data Curation, TSK, NOJ, AWK and MA; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, TSK; Writing – Review & Editing, NOJ, AWK and MA; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mokomane, Z., Social protection as a mechanism for family protection in sub-Saharan Africa 1. International Journal of Social Welfare, 2013. 22(3): p. 248-259. [CrossRef]

- Assembly, UG, Universal declaration of human rights. UN General Assembly, 1948. 302(2): p. 14-25.

- Commissioner, U.N.H.R.O.o.t.H. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. 1966 [cited 2022 December 23]; Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights. 23 December.

- Bachelet, M. and IL Office, Social protection floor for a fair and inclusive globalisation. 2012: International Labour Office Geneva.

- Bloom, D.E. and R. McKinnon, The design and implementation of pension systems in developing countries: issues and options, in International handbook on ageing and public policy. 2014, Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 108-130.

- Cohen, J.E., Human population: the next half century. science, 2003. 302(5648): p. 1172-1175. [CrossRef]

- Dadush, U.B. and B. Stancil, The world order in 2050. 2010: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Washington, DC.

- WHO. Ageing and health. 2022 [cited 2023 March 23]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Shetty, P., Grey matter: ageing in developing countries. The Lancet, 2012. 379(9823): p. 1285-1287. [CrossRef]

- Bank, W. Safety Nets: Social safety net programs protect families from the impact of economic shocks, natural disasters, and other crises. 2019 [cited 2023 March 01]; Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/safetynets. 01 March.

- Geffen, L.N., et al., Peer-to-peer support model to improve quality of life among highly vulnerable, low-income older adults in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC geriatrics, 2019. 19: p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P.E. and T. Yamamoto, Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 2005. 33(2): p. 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Organisation, WH, World report on ageing and health. 2015: World Health Organization.

- WHO, The global burden of disease 2004. 2008: World Health Organization.

- Arza, C., The gender dimensions of pension systems. UN Women, 2015.

- Doh, D., S. Afranie, and E.B.-D. Aryeetey, Expanding social protection opportunities for older people in Ghana: A case for strengthening traditional family systems and community institutions. Ghana Social Science Journal, 2014: p. 26-52.

- Deaton, A., Saving and liquidity constraints. 1989, national bureau of economic research Cambridge, Mass., USA.

- Gersovitz, M., Saving and development. Handbook of development economics, 1988. 1: p. 381-424.

- Schmidt-Hebbel, K., S.B. Webb, and G. Corsetti, Household saving in developing countries: first cross-country evidence. The world bank economic review, 1992. 6(3): p. 529-547.

- Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Social policy and population ageing: challenges for north and south. International journal of epidemiology, 2002. 31(4): p. 754-757. [CrossRef]

- Auer, P. and M. Fortuny, Ageing of the labour force in OECD countries: Economic and social consequences. 2000: Citeseer.

- Been, J., et al., Public/private pension mix, income inequality and poverty among the elderly in Europe: An empirical analysis using new and revised OECD data. Social Policy & Administration, 2017. 51(7): p. 1079-1100. [CrossRef]

- Organisation, WH, WHO Ageing, and LC Unit, WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2008: World Health Organization.

- Worldometer. Ghana Population. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 2, 2023]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ghana-population/.

- Badasu, D. and A. Forson, Population & Housing Census Report: The Elderly in Ghana. Ghana Statistical Service and United Nations Population Fund, Accra, 2013.

- Pillay, N.K. and P. Maharaj, Population ageing in Africa, in Aging and health in Africa. 2012, Springer. p. 11-51.

- Aganiba, B.A., et al., Association between lifestyle and health variables with nutritional status of the elderly in the northern region of Ghana. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 2015. 15(4): p. 10198-10216. [CrossRef]

- Mba, CJ, Population ageing and survival challenges in rural Ghana. Journal of Social Development in Africa, 2004. 19(2). [CrossRef]

- Adzawla, W., S.A. Baanni, and R.F. Wontumi, Factors influencing informal sector workers’ contribution to pension scheme in the Tamale Metropolis of Ghana. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 2015. 5(2): p. 37-45. [CrossRef]

- Collins-Sowah, P.A., J.K. Kuwornu, and D. Tsegai, Willingness to participate in micro pension schemes: Evidence from the informal sector in Ghana. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 2013. 5(1): p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Kubuga, K.K., D.A. Ayoung, and S. Bekoe, Ghana’s ICT4AD policy: between policy and reality. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 2021. 23(2): p. 132-153. [CrossRef]

- Osei-Boateng, C. and E. Ampratwum, The informal sector in Ghana. 2011: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Ghana Office Accra.

- Nunoo, N.O., An evaluation of the old and new pension schemes in Ghana and their effects on the informal sector. 2013.

- Anku-Tsede, O. Inclusion of the Informal Sector Pension: The New Pensions Act. in Advances in Social and Occupational Ergonomics: Proceedings of the AHFE 2019 International Conference on Social and Occupational Ergonomics, July 24-28, 2019, Washington DC, USA 10. 2020. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Anku-Tsede, O., A. Amankwaa, and A. Amertowo, Managing pension funds in Ghana: An overview. Business and Management Research, 2015. 4(1): p. 25-33. [CrossRef]

- Boyetey, D.B., O. Boampong, and F. Enu-Kwesi, Effect of institutional mechanisms on micropension saving among informal economy workers in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. Heliyon, 2021. 7(9): p. e08004. [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F., The informal sector in Ghana under siege. Journal of Developing Societies, 2011. 27(3-4): p. 355-392. [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, E., Population ageing in Ghana: a profile and emerging issues. African Population Studies, 2011. 25(2). [CrossRef]

- Appiah, P.O., The National Pensions Act, 2008 (Act 766) and Challenges of Pension Fund Administration in Ghana. Journal of Legal Subjects (JLS) ISSN 2815-097X, 2023. 3(02): p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Ashidam, B.N.A., The problem of the cap 30 pension scheme in ghana. 2011.

- Worldometer. Pakistan Population. 2023 [cited 2023 February 02]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/pakistan-population/.

- Knoema. Pakistan Population aged 65 years and above, 1960-2022 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 2, 2023]; Available from: https://knoema.com//atlas/Pakistan/Population-aged-65-years-and-above.

- Clark, G., Pakistan’s Zakat system: A policy model for developing countries as a means of redistributing income to the elderly poor. Social Thought, 2001. 20(3-4): p. 47-75. [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, U. and A.Z. Asad, The rising old age problem in Pakistan. Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan–Vol, 2017. 54(2).

- Alam, A., M. Ibrar, and P. Khan, Socio-Economic and psychological problems of the senior citizens of Pakistan. Peshawar Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences (PJPBS), 2016. 2(2): p. 249-261. [CrossRef]

- Arif, U. and E. Ahmad, Pension Reforms: A Case for Pakistan. Journal of Economic Co-operation & Development, 2012. 33(1): p. 113.

- Gazdar, H., Social protection in Pakistan: in the midst of a paradigm shift? Economic and Political Weekly, 2011: p. 59-66.

- Pakistan, S.B.o. Ffinancial stability review. 2017 [cited 2022 December 23]; Available from: https://www.sbp.org.pk/FSR/2017/boxes/Box-4.2.1.pdf. 23 December.

- Worldometer. Myanmar Population. 2023 [cited 2023 January 31]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/myanmar-population/.

- International, H. Myanmar Country profiles Pension watch. 2021 [cited 2023 Feb 2, 2023]; Available from: http://www.pension-watch.net/country-fact-file/myanmar.

- Knodel, J. and B. Teerawichitchainan, Aging in Myanmar. The Gerontologist, 2017. 57(4): p. 599-605. [CrossRef]

- Mekong, OD. Elderly social pension for 2017/18 to be allocated in June. 2017 [cited 2023 February 02]; Available from: https://opendevelopmentmekong.net/news/elderly-social-pension-for-201718-to-be-allocated-in-june/#!/story=post-5756709&loc=16.647565,96.1129218,7.

- Group, EM. More than 168000 elderly aged 85 and above entitled to social pension. 2019 [cited 2022 December 22]; Available from: https://elevenmyanmar.com/news/more-than-168000-elderly-aged-85-and-above-entitled-to-social-pension.

- Coryn, C.L., et al., A systematic review of theory-driven evaluation practice from 1990 to 2009. American journal of Evaluation, 2011. 32(2): p. 199-226. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S.I., Program theory-driven evaluation science: Strategies and applications. 2007: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Funnell, S.C. and P.J. Rogers, Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models. 2011: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rogers, P.J. and C.H. Weiss, Theory-based evaluation: Reflections ten years on: Theory-based evaluation: Past, present, and future. New directions for evaluation, 2007. 2007(114): p. 63-81. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.I., Social security for the elderly: Experiences from South Asia. 2014: Routledge.

- Rapley, T., Doing conversation, discourse and document analysis. Vol. 7. 2018: Sage.

- Service, RW, Book Review: Corbin, J., & Strauss, A.(2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Organisational Research Methods, 2009. 12(3): p. 614-617. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.E. and W. Reiboldt, The multiple roles of low income, minority women in the family and community: A qualitative investigation. The qualitative report, 2004. 9(2): p. 241-265.

- Agyepong, I.A. and S. Adjei, Public social policy development and implementation: a case study of the Ghana National Health Insurance scheme. Health policy and planning, 2008. 23(2): p. 150-160. [CrossRef]

- Obiri-Yeboah, D. and H. Obiri-Yeboah, Ghana’s pension reforms in perspective: Can the pension benefits provide a house a real need of the retiree?’. European Journal of Business and Management, 2014. 6(32): p. 121-133.

- Darko, E., ’’The effectiveness of the current three-tier pension scheme in providing adequate social security for Ghanaians: evidence from the eastern region of Ghana,‟ Mphil organisation and human resource management degree. University of Ghana, 2016.

- Holzmann, R., The World Bank approach to pension reform. International Social Security Review, 2000. 53(1): p. 11-34.

- Shaikh, S.A., Welfare potential of zakat: An attempt to estimate economy wide zakat collection in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 2015: p. 1011-1027.

- Group, EM. More than 168000 elderly aged 85 and above entitled to social pension. 2019 [cited 2023 February 02]; Available from: https://elevenmyanmar.com/news/more-than-168000-elderly-aged-85-and-above-entitled-to-social-pension.

- Arif, U. and E. Ahmed, Pension system reforms for Pakistan: Current situation and future prospects. 2010: Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

- Jalal, S. and M.Z. Younis, Aging and elderly in Pakistan. Ageing International, 2014. 39: p. 4-12. [CrossRef]

- Quartey, P., M.E. Kunawotor, and M. Danquah, Sources of retirement income among formal sector workers in Ghana. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 2016.

- Regúlez-Castillo, M. and C. Vidal-Meliá, Individual information for pension contributors: Recommendations for Spain based on international experience. International Social Security Review, 2012. 65(2): p. 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Sarpong-Kumankoma, E., Financial literacy and retirement planning in Ghana. Review of Behavioral Finance, ahead-of-p (ahead-of-print). 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S. and M.G. Asher, Micro-pensions in India: Issues and challenges. International Social Security Review, 2011. 64(2): p. 1-21.

- Barr, N. and P. Diamond, Reforming pensions: Principles and policy choices. 2008: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N. and Z.M. Nasir, Pension and social security schemes in Pakistan: Some Policy Options. 2008, East Asian Bureau of Economic Research.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).