1. Introduction

An ambulance in an emergency (AIAE) faces a critical dilemma upon encountering a red light at a traffic signal: the driver must decide to wait, wasting vital time, or to cross the road, with the risk of accidents. Every year, [

1] a lot of accidents happen at the traffic light because the red light isn’t respected: in numerous newspaper articles, the focus is on incidents at traffic lights involving an AIAE disregarding the red signal. Ray and Kupas [

2] have concluded also that ambulance crashes occur more frequently at intersections and traffic lights and involve more people and more injuries than those of similar-sized generic vehicles. Furthermore, the analysis of Kahn et al. [

3] shows that most crashes and fatalities occurred during emergency use. The implementation of a well-designed system that timely grants a green light to the ambulance could prevent such occurrences. Also, studies [

4] show the annual toll of traffic congestion, encompassing fuel wastage, time lost and carbon emissions. Furthermore, the main factor that causes ambulance delays is traffic congestion (other factors are the bad location to be reached and the lack of personnel) and the traffic congestion often occurs especially at the traffic light [

5], and at one-way restrictions (e.g. due to repair works). Notably, the traditional traffic lights following a rigid fixed-time policy substantially contributes to these inefficiencies, which can be minimized through the adoption of intelligent policies, as demonstrated in the works of Mousavi et al. [

6], Zhao et al. [

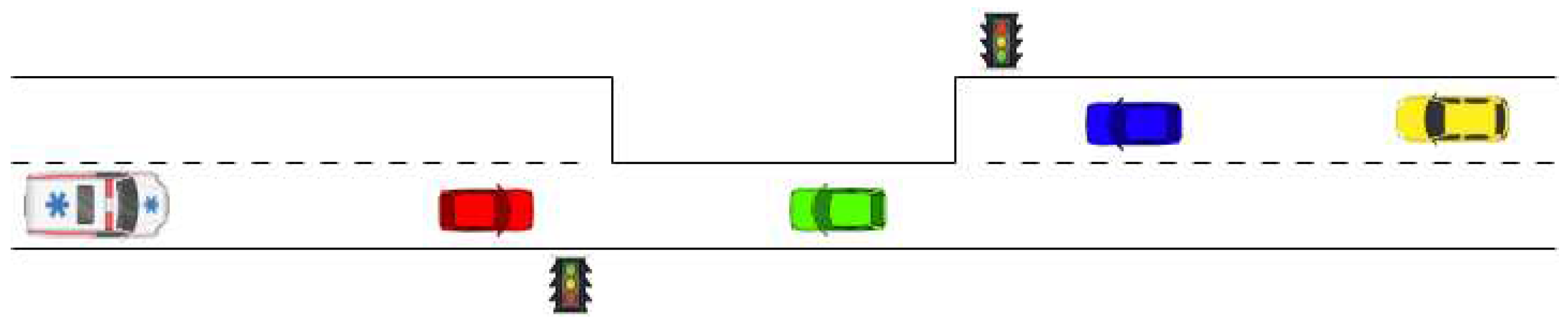

7] and many others. Traffic lights serve two primary purposes: first, they regulate traffic flow at typical four-way intersections; second, they manage unidirectional traffic in scenarios where road restrictions, such as repair works or other impediments, are in place. Existing literature extensively covers the former, particularly addressing the coordination of consecutive four-way intersections. However, this paper specifically focuses on the latter case (reported schematically in

Figure 1), where unidirectional traffic conditions prevail, often resulting in prolonged red-light durations (in fixed-time policies). The prolonged red phase is imperative to ensure the thorough clearance of unidirectional traffic before permitting the activation of the green light.

In

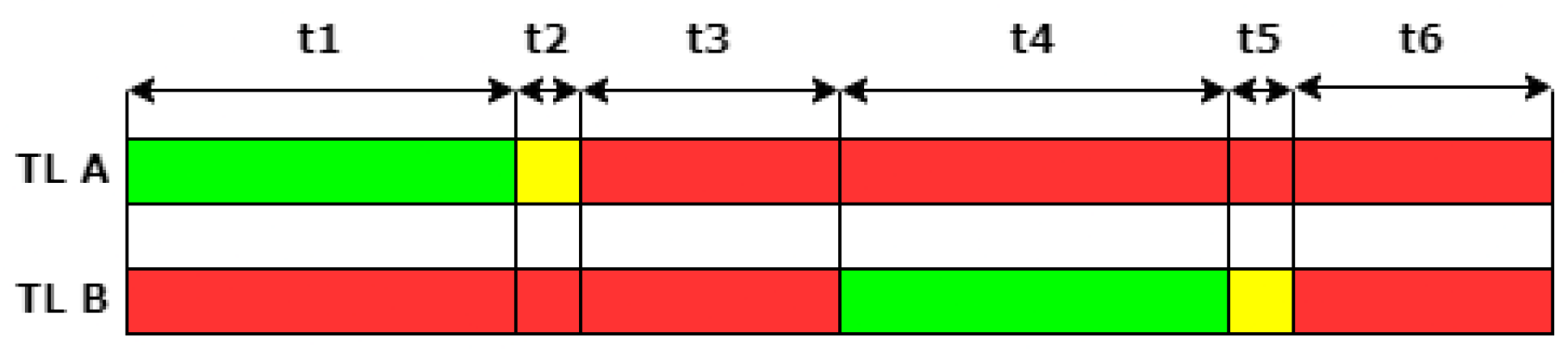

Figure 2 a schema of the traffic light (TL) cycle in the case of unidirectional traffic management is reported.

The intervals t3 and t6 (the "double red" periods) report the time needed for a vehicle to fully transverse the restriction from its start to the end at a typical speed. After this time interval the restriction can be assumed to be clear from vehicles. The "double red" intervals duration depends on the length of the restriction and on the speed-limit applied to ensure the safety of the vehicles traveling in it. For this reason, the “double red” duration can’t be changed to ensure vehicles safety. Our proposed solution solely alters the intervals t1 and t4, while leaving t2 and t5 to the minimum time required by law. When at a Lookout Station (LS) an Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE) is detected (provided that the LS is situated at a certain optimal distance from the traffic light), the t1 or the t4 is shrinked to zero depending on the direction according to which the AIAE is approaching the one-way tract. This way, the system is able to guarantee a green light when the AIAE arrives at the traffic light controlling the one-way restriction. The detector we propose, termed the Real-Time Ambulance in an Emergency Detector (RTAIAED), exploits elementary detectors combined together in a "part-based model" architecture to achieve robust and quick predictions. The RTAIAED combines a feedforward neural network for the audio analysis aspects and several detectors based on YOLOv8 for the visual analysis phase, both working in synergy to improve the global performance. The solution presented in this paper, while detecting AIAE, also provides seamless adaptability without requiring additional hardware components for monitoring traffic conditions and implementing optimization techniques. Notably, it provides the advantage of anticipating the arrival of vehicles at traffic lights from both sides, seconds (or even minutes) in advance.

The main contributions of this paper are outlined as follows:

The development of a new architecture (called RTAIAED), inspired by the Deformable Part Model [

8] capable of accurately and reliably detecting Ambulances in Emergency. The system is composed of some elementary detectors based on Deep Learning, operating in synergy, each specialized in the recognition of a specific sub-part. The system runs in real-time even on an average Single Board Computer;

the development of a Lookout Station (LS) capable of running the RTAIAED at a certain distance from the corresponding traffic light. The early detection of an AIEA can be communicated remotely to grant a timely action of the Traffic Light Controller (TLC) to minimize (or even cut to zero) the waiting time of the Ambulance as it reaches the one-way restricted road;

a methodology to change the traffic light cycle in the unidirectional traffic case, so as to reducing the Ambulance waiting time while preserving the safety of the involved vehicles in transit in the restricted tract.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a review of related works,

Section 3 presents the proposed methodology, the software and the hardware involved,

Section 4 reports the experimental results and

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

In current literature, the focus of optimization of the traffic light systems is put on the case of intersections management. To enhance the behavior of traffic lights in comparison to the fixed-time policy, contemporary literature frequently turns to reinforcement learning techniques, as exemplified by prior work of Liang et al. [

9] or Wiering et al. [

10].

Some works, like the one of Liu et al. [

11], employ reinforcement learning with multi-agents to orchestrate all the traffic lights in a city (or at least those at adjacent road intersections), achieving significant results in terms of decongestion. However, it’s noteworthy that these approaches do not prioritize emergency vehicles.

Other approaches, like that of Navarro-Espinoza et al. [

12], attempt to predict future traffic flow (the next 5 minutes) based on past flow (the last hour). Nonetheless, they neglect to exploit the current traffic flow to acquire information about the prospective flow in an alternative location. The foresight into the anticipated arrival time of each detected vehicle yields noteworthy advantages, particularly in scenarios where, at a specific moment, a substantial number of vehicles are observed arriving from one side while none or significantly fewer are coming from the other.

Another important aspect is linked to the communication between the traffic light controller and the “outside world”. To notify the Traffic Light Controller of an approaching AIAE, it must be equipped with a receiver so that the controller itself can adjust the sequence and duration of the lights upon receiving specific signals and commands. These signals may be transmitted either by a human operator or by an automated system utilizing various sources (radio, audio, visual) to identify the presence of an AIAE. In the "VAI 118" system [

13], for example, constant communication takes place between the Urgency and Medical Emergency Service (SUEM) operations center and the Municipality’s Mobility Center. Ambulance arrivals are signaled using on-board Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs), requiring each ambulance to be consistently equipped with a functional PDA. Ford has also proposed a comparable solution [

14], which is currently in progress, wherein the emergency vehicle communicates directly with the traffic light upon its approach. However, this approach alerts the traffic light when the emergency vehicle is already in close proximity. Ford’s strategy involves reducing the need for a complete stop by decreasing the vehicle’s speed through proprietary software. This ensures that by the time the vehicle reaches the traffic light, the signal will have already switched to green. Both of these solutions require installing a dedicated device in each ambulance, imposing additional hardware for both traffic lights and ambulances. Siddiqi et al. [

15] proposed a system in which the communication between ambulances and traffic lights is provided through a mobile application developed by them and operated by ambulances teams. This application controls the traffic lights via SMS. However, all these solutions require the remote manipulation of traffic lights by human operators. Moreover, neither of these approaches addresses the objective of minimizing traffic congestion. In contrast, Islam et al. propose an alternative approach [

16] in which only the traffic lights require additional hardware to detect emergency vehicles. Their solution entails installing multiple microphones to detect the presence of a siren and determine its direction. This approach eliminates the need for additional equipment in each ambulance and addresses some limitations of the previously mentioned solutions. A more accurate approach relying solely on audio data, has been introduced by Pacheco-Gonzalez et al. [

17]. However, these approaches do not guarantee the reliable detection of an ambulance’s arrival at a traffic light, as the siren sound may propagate from parallel roads, and adverse weather conditions and ambient noises can obscure the ambulance’s presence. Additionally, these methods cannot be leveraged to alleviate traffic congestion. In an alternative strategy, using visual data, Barbosa et al. [

18] developed a system to distinguish between different types of vehicles (ambulances, police cars, fire trucks, buses and regular cars), assigning each a different priority. However, their system doesn’t verify if the emergency vehicles are genuinely in an emergency, prioritizing them even when unnecessary.

In conclusion, another alternative approach uses Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), a technique that uniquely identifies objects by exploiting radio waves. This method was proposed by Sharma et al. [

19], in which the emergency vehicles broadcast messages to signal their presence, allowing the messages to be read by the Traffic Light Controller (TLC). This approach requires the installation of a radio frequency reader on each road managed by a traffic light system and a RFID tag on each emergency vehicle, resulting in a not so well scalable model. Similarly, in the solution by Eltayeb et al. [

20], each ambulance and TLC is equipped with a Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) module (with a SIM card) to communicate via SMS the position of the ambulance, thanks to a GPS embedded in the vehicle.

Existing approaches predominantly center around vehicles currently positioned at the traffic light. What distinguishes RTAIAED is fourfold: firstly, it doesn’t require any additional hardware in the ambulances; secondly, it emphasizes the estimation of the expected arrival time of vehicles identified at a considerable distance, enabling prompt and proactive actions; thirdly, it is very reliable in detecting a genuine AIAE (Ambulance in an Emergency), discarding the ambulances not in an emergency and the ones not going towards the traffic lights; fourthly, it is capable to manage also the traffic flow in normal conditions without additional hardware.

Regarding the architecture of RTAIAED, it draws inspiration from the "Parts and Structure" concept inherent in Part-Based Models, first introduced by Fischler and Elschlager in 1973 [

21]. These models detect the presence of an object of interest in an image by analyzing various parts within the image. An evolution of Part-Based Models is the Constellation Model, proposed by Fergus et al. [

22], wherein a small number of features, their relative positions, and mutual geometric constraints are leveraged to determine the presence of an object of interest.

The RTAIAED extends these ideas beyond the visual field, incorporating the audio and temporal fields in a pyramidal approach to reach the final decision. Additionally, it employs Deep Learning Models [

23] as elementary detectors to identify relevant features, departing from classic stochastic learning methods.

3. The RTAIAED: Hw and Sw architecture

In laying the groundwork for the implementation of the proposed RTAIAED it’s crucial to take into account three key factors: the passage of an ambulance, the existence of an emergency situation and the direction of travel. To improve the system performance, we consider the fact that a typical ambulance incorporates distinctive elements, like:

the symbol of the star of life;

the symbol of the red cross;

the written text “ambulanza” (mirrored or not).

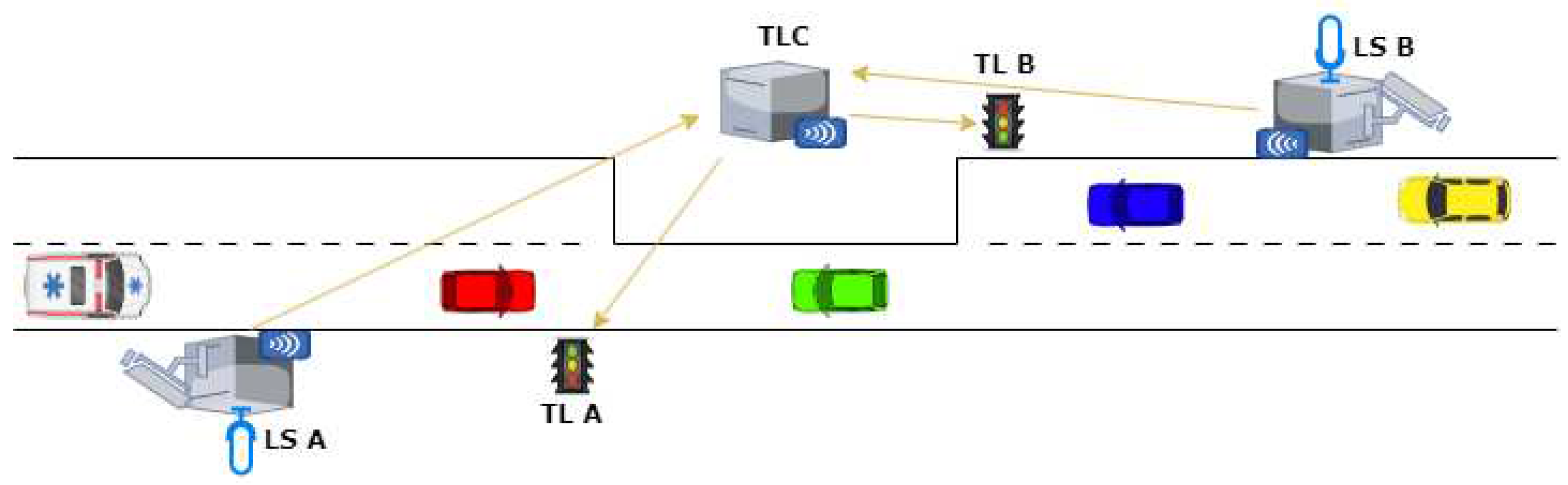

Even if the previous elements relate to the Italian Ambulances, similar distinctive elements are present in all Ambulances around the world and the general approach proposed in this paper can be easily adapted by training the recognition module to detect and identifying each specific set of elements. Additionally, the direction of travel is pivotal; only ambulances approaching the traffic light should receive a green signal. Moreover, in emergency scenarios, Ambulances will activate their flashing lights and sirens. All these elements, except the siren, can be captured through images. Processing the siren signal, however, necessitates audio capabilities. Hence, a camera and a microphone are essential components. Furthermore, it’s imperative to obtain this information from a distance, specifically at a LS, necessitating the inclusion of a transceiver module. Another crucial constraint is obtaining real-time information. As we will show, a single-board computer is sufficient for this objective. Referring back to the preceding statements, the RTAIAED is built upon these essential software and hardware components and it is expected to be mounted at each LS, as shown in

Figure 3. In it, each LS communicates the presence of an AIAE to the Traffic Light Controller (TLC), to enable the manipulation of the sequence of colors and their duration at the traffic lights at both ends of the one-way restriction. The camera of each LS is deliberately pointed in the opposite direction of the road restriction, to be able to catch the AIAE as far as possible from the tract of unidirectional traffic (i.e. as early as possible).

3.1. SW architecture

To accurately detect AIAE, the presence of an Ambulance with its peculiar elements, its motion direction, and the status of its siren must be assessed. The RTAIAED thus is based on several elementary detectors, that can be divided into two fundamental modules:

some visual object detectors, that process in real-time the frames coming from the camera and are based on some customized YOLOv8 models, each of them with the task of detecting a component of the ambulance or the ambulance in its entirety, distinguishing its front part from its rear part;

an audio detector, that processes in real-time the audio coming from the microphone exploiting a feedforward neural network based on Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs).

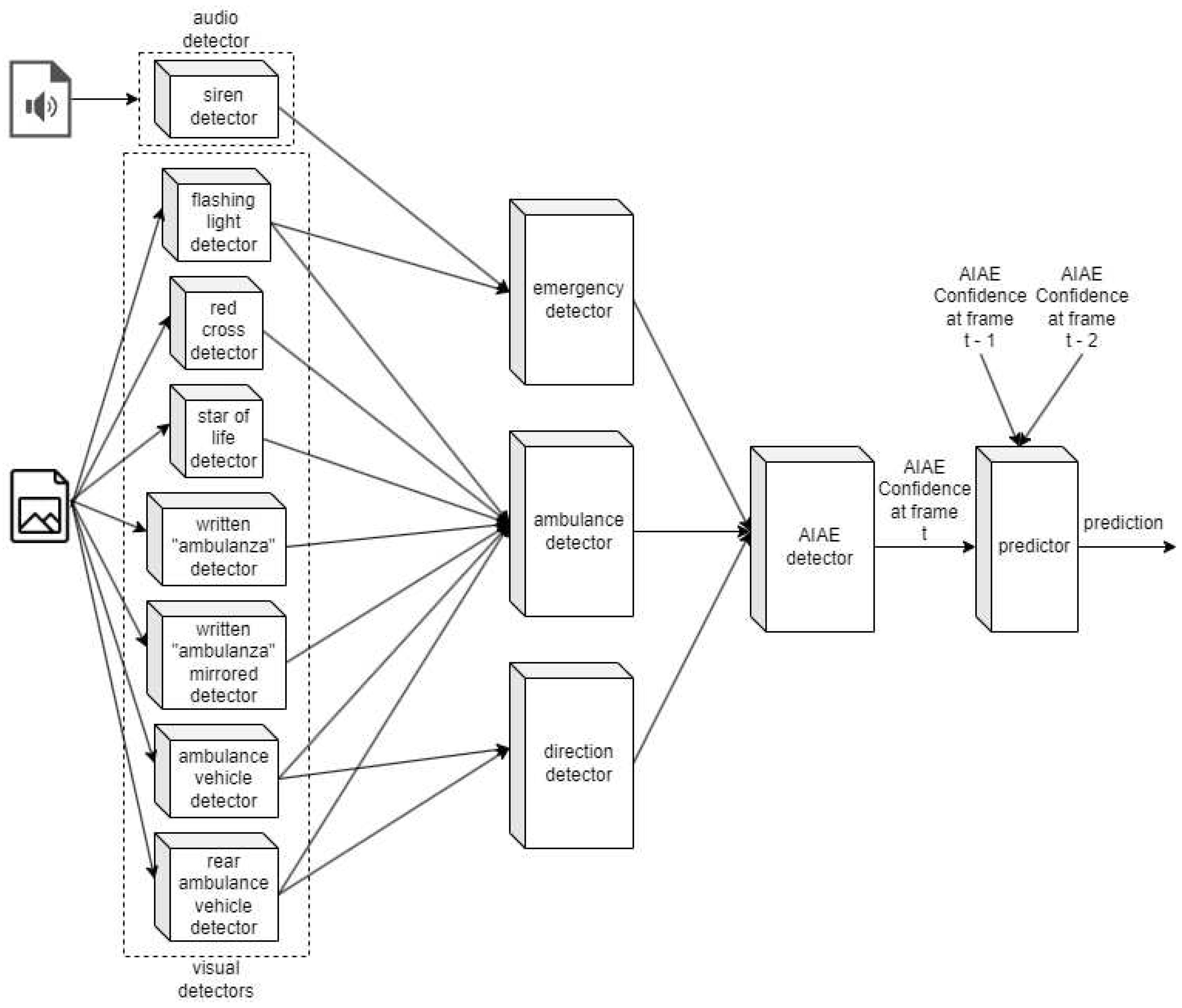

Every frame, the visual detectors give a prediction valid for the current frame. Simultaneously, the audio signal undergoes processing every one and a half seconds, maintaining the validity of its prediction until the subsequent processing cycle. The overall architecture of RTAIAED, depicted in

Figure 4, showcases a pyramidal structure comprising elementary detectors, including audio and object detectors. These detectors comprise an emergency, an ambulance, and a direction detector, and their outcomes are leveraged by the AIAE detector to output the confidence level regarding the presence of an Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE) in the current frame. This result is then combined with the one from the previous two frames to yield a final prediction. In simpler terms, the confirmation of an Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE) is established only when, over at least three consecutive frames, an ambulance is detected moving in the correct direction toward the traffic lights, concurrently with the identification of an emergency.

In the following, each part composing the model is discussed in the following order: the elementary audio detector, the elementary visual detectors, the ambulance detector, the emergency detector, the direction detector, the AIAE detector.

3.1.1. The Elementary Audio Detector

The audio detector, also referred to as a siren detector, is employed to detect the typical sound of an ambulance siren, with the primary objective of being a pillar for the emergency detector. It has been developed by extracting Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) features from two-second audio samples and feeding them into a feedforward neural network. MFCCs have been chosen due to their ability to offer a condensed representation of the spectrum of an audio signal, encapsulating information about rate changes across various spectrum bands [

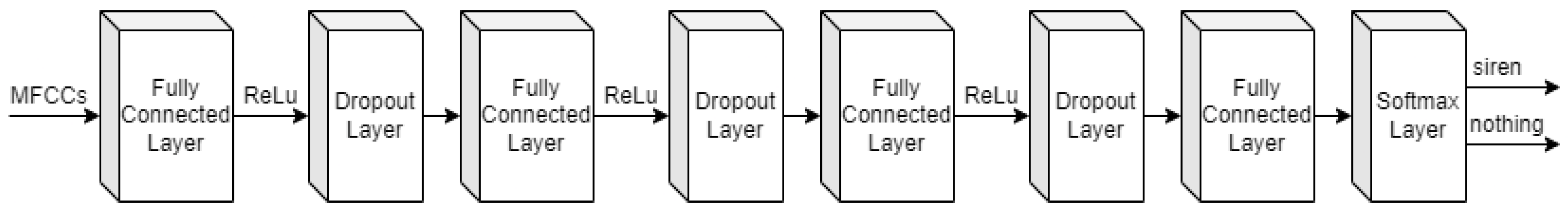

30]. The NN used to detect the siren has the following architecture:

4 fully connected layers;

3 dropout layers, each of which randomly sets input units to 0 with a predetermined frequency to prevent overfitting;

3 reLu;

A final softmax, to decide about the two output classes (siren or nothing).

In

Figure 5 a schema of the NN is reported.

The siren detector has been implemented by using Tensorflow and Keras and then it has been exported to the ONNX format. The training dataset comprises 1,240 .wav files featuring the presence of a siren (one or more), alongside 4,805 files with silence or different kinds of sounds (airplanes, trains, rain, storms, chainsaws, helicopters, traffic noises, anti-theft alarms, fireworks, animal sounds). For training purposes, 90% of the dataset has been used, while the remaining 10% has been reserved for validation.

3.1.2. The Elementary Visual Detectors

The elementary visual detectors play a crucial role in accurately detecting the ambulance vehicle and its parts within video frames. Additionally, they help disambiguating the direction of the ambulance, enhancing overall detection precision. The parts to be detected are:

the ambulance vehicle, with the distinction between the front and the rear;

the flashing light;

the symbols of the star of life and of the red cross;

the text “ambulanza”, in the normal or reversed sense.

The front part and the rear part of the ambulance have two different labels to distinguish when an ambulance is approaching the traffic light and when it is going away from it. These detectors have been created with a customized YOLOv8 model. YOLO is a deep learning model introduced in 2015 by Redmon et al. [

24]. It is a cutting-edge deep learning model designed for real-time object detection. It rapidly identifies specific objects in videos, live feeds, or images. Leveraging deep convolutional neural networks, YOLO extracts features from input images, enabling the prediction of bounding boxes with confidence scores for each recognized object. Its speed is a result of segmenting an image into smaller units, processed only once by the algorithm: an innovation compared to multi-stage or region-based methods. YOLO models, including the latest iteration, YOLOv8, developed by Ultralytics [

25], can be efficiently trained on a single GPU, ensuring high accuracy while retaining a compact size.

Under YOLOv8, there are multiple models of different sizes, ranging from smaller to larger, namely: YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8m, YOLOv8l, YOLOv8x. All YOLOv8 models come pre-trained on the COCO dataset [

26], a comprehensive collection of images spanning 80 different object categories. By default, the size of the input images is set at 640 x 640 pixels, but any size multiple of 32 is accepted. For the elementary visual detectors, the model n has been exploited as a starting point, leading to a customized model with less parameters, similar to that demonstrated by Ke et al. [

27] in the domain of license plate recognition or by Xiao et al. [

28] in the domain of pedestrian detection and tracking. The customized model (the tiny model t) has been created through adjustments to the settings in the yolov8.yaml file, reducing the number of channels and layers in the final part of the backbone, passing from 225 layers, 3012213 parameters, 3012197 gradients, 8.2 GFLOPs of the model n to 218 layers, 1357013 parameters, 1356997 gradients, 6.3 GFLOPs.

Both model n and model t have been trained with two different input resolutions: 640 x 640 pixels and 480 x 480 pixels, leading to the creation of the models 640n, 640t, 480n, 480t. For simplicity, only the results of the best model in terms of speed and final performance will be reported (i.e. 480t), while providing aggregated comparisons with the other models. Each candidate to be the elementary visual detector (i.e. the models 640n, 640t, 480n, 480t) has been trained on a dataset containing 2,172 images, collected from photos and videos with heterogeneous resolutions, with every object manually labelled with the tool labelImg [

29].

In addition to labeled images, the dataset includes background images devoid of labeled objects, strategically incorporated to mitigate false positives. The model 640n underwent iterative training using incremental learning, with evaluations conducted after each iteration to pinpoint instances of suboptimal performance. Following each iteration, new images resembling those where the model exhibited shortcomings were introduced, enhancing the model’s proficiency in addressing these specific scenarios. Using the model 640n as a starting point, further iterations have been incorporated to refine and train the models 640t and 480n. Thereafter, the insights gained from model 480n have been leveraged to develop the derivative model 480t.

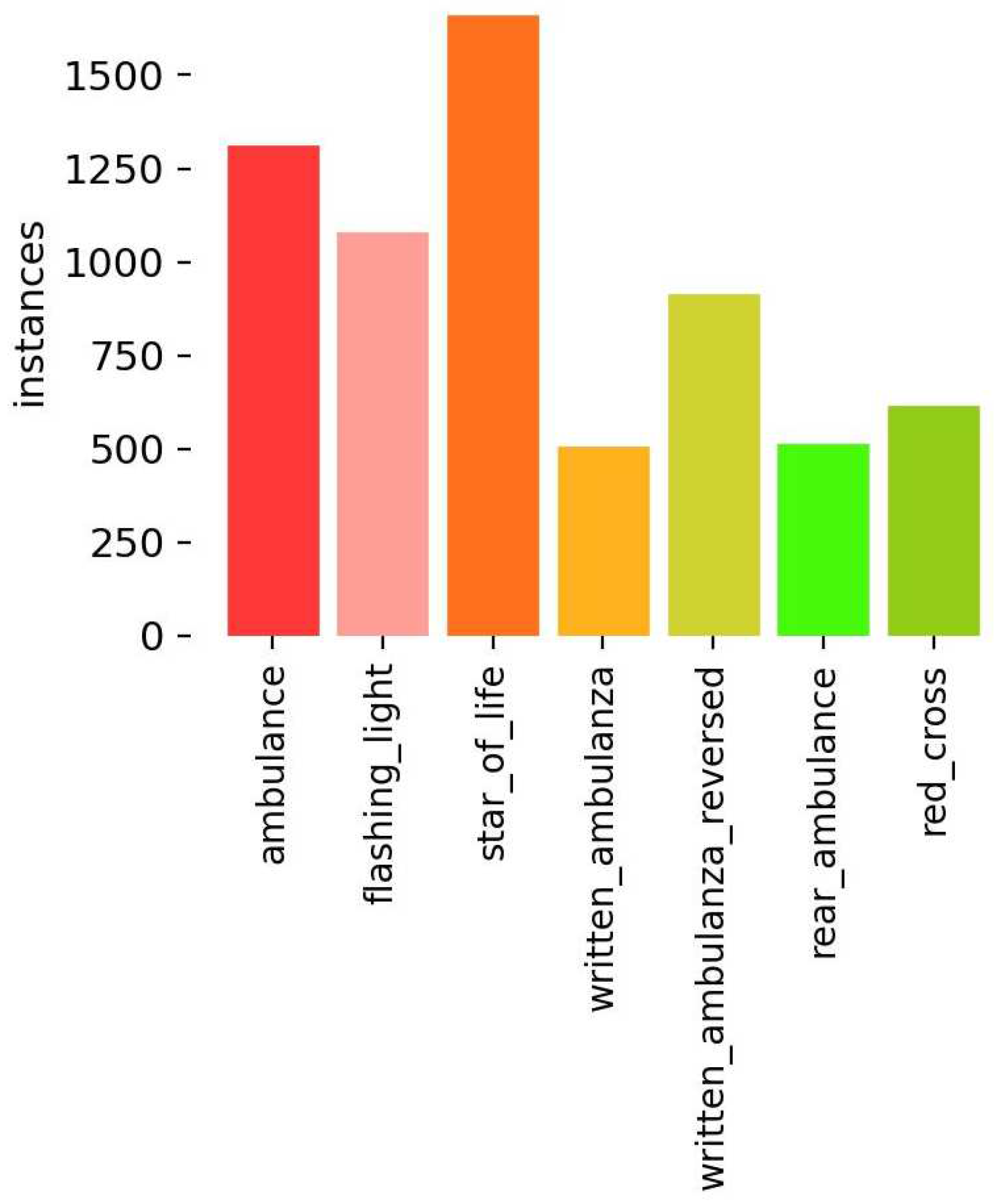

The distribution of the instances used in the training dataset is shown in the histogram of

Figure 6.

3.1.3. The Ambulance Detector

The so-called ambulance detector takes as input the results from all elementary visual detectors and undergoes additional processing to confirm the presence of at least one ambulance within the scanned frame. More specifically, it checks whether the elementary ambulance vehicle detector has predicted the presence of an ambulance. In the affirmative scenario, the remaining elementary visual detectors are considered; otherwise, no further action is taken, and no ambulance presence is assumed. If the additional detectors identify some specific sub-parts, they adjust the confidence that an ambulance is truly present within the current frame based on their findings. The positions of all predicted sub-parts are scrutinized for location consistency. Specifically, the flashing light detection concentrates on the upper portion of a recognized ambulance. Instances where flashing lights are not detected in this region are filtered out and labeled as false positives. Regarding written or symbolic elements (such as "ambulanza", "ambulanza" reversed, the symbol of the star of life and the symbol of the red cross, illustrated in

Figure 7), they are considered correctly detected only if they appear within a region recognized as an ambulance vehicle. Detections outside this context are filtered out. Additionally, the detection of the rear part of an ambulance results in the prediction being discarded because if the rear part is identified, it is assumed that the ambulance is traveling in the opposite direction, away from the traffic light.

Each detected element that survives the filtering process is then assigned a weight, which is subsequently multiplied by its corresponding confidence score from the object detector’s prediction. The formula used to determine the presence of an ambulance is as follows:

Here,

represents a threshold, N is the count of detected elements within an object identified as an ambulance,

is the confidence of the prediction for the ith element of class j, and

represents the weight assigned to the corresponding jth class. This mechanism, inspired by Deformable Parts Models [

8], plays a crucial role in affirming that an object identified as an ambulance truly aligns with the characteristics of an ambulance. The underlying intuition is that a higher count of elements specific to an ambulance within the detection region increases the likelihood of it being a genuine ambulance. Elements not contributing to detecting an ambulance vehicle are filtered out, as they could be errors or elements found in other vehicles, such as a Social Service car.

The threshold and weights can be determined empirically or through alternative methods, such as employing a dynamic programming algorithm to assess each final prediction generated by the model based on various thresholds and weights. Eventually, the best-performing combination is selected according to a predefined criterion.

The trade-off arises from the fact that reducing the threshold increases the likelihood of detecting more true positives but also leads to an uptick in false positives. Therefore, the threshold should not be set excessively low (to avoid an excess of false positives) nor too high (to prevent overlooking genuine ambulances).

In our solution, three thresholds (0.8, 0.85, and 0.9) have been considered, and the weights have been learned according to the following formula:

Where FP and TP are respectively the False Positives and the True Positives of the presence of an ambulance going towards the camera, according to each of the T thresholds. TP values are squared to assign them less significance in comparison to FP, given that both values range between 0 and 1. Squaring TP reduces its impact, considering the possibility that an unnoticed ambulance can be identified in subsequent frames. The emphasis lies in avoiding the error of predicting an object as an ambulance when it is not, rather than missing the recognition of an actual ambulance. S is the number of samples (images) on which the weights are learned, N is the number of objects detected in each sample, and j is the class of the detected object.

denotes the confidence of an object inside an image without an ambulance going towards the camera that has produced a false positive, along with the other objects inside the same image using the Formula

1, according to the threshold t and c denotes the confidence of an object in an image containing one or more ambulances going towards the camera that has produced a true positive according to the threshold t. The weights w follow the constraints:

With z

.

The weights have been learned using a dataset with challenging samples of ambulances or vehicles that may resemble ambulances. The dataset comprises 559 images with hard to be recognized ambulances, 501 images without it, and with 320 images of the rear part of an ambulance. The output of this detector is the overall confidence of the presence of an ambulance, according to Formula

1.

3.1.4. The Emergency Detector

Even when an ambulance is visible in the scene, it’s crucial to reliably assess whether it is in an emergency state or not. The determination of an actual emergency is made by the siren detector and the flashing light detector. Specifically, the emergency detector, upon detecting a flashing light (only if observed within an object recognized as an ambulance vehicle), retains this information for the subsequent 4 frames. This compensates for the intermittent nature of flashing lights, which might be detectable in one frame but not in the next due to their pulsating nature – they are only detectable when emitting light. Additionally, since the siren detector is executed every one and a half seconds, its result is retained until its next execution. Therefore, the Emergency Detector combines the outcomes of the flashing light detector and the siren detector to raise a flag indicating the presence of an emergency. This information is crucial for determining whether an Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE) is approaching a traffic light. The output of this process includes a flag indicating the predicted emergency and also conveys information about the presence or absence of the siren.

3.1.5. The Direction Detector

As mentioned earlier, the direction of motion of the Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE) provides crucial information, as it determines whether its transit should be prioritized or not. An AIAE that is moving away from the traffic lights is not to be considered. The motion of the ambulance is determined through a series of checks. Initially, the elementary visual ambulance vehicle detector must identify an ambulance while excluding the ones showing their rear part, and the elementary visual rear ambulance detector must identify the rear parts, to correct the mistakes done by the other detector. In fact, in instances where one ambulance (or more) and one rear part (or more) are detected in the same frame, the Intersection over Union (IoU) of the rear part with respect to the ambulance is calculated to ascertain if it belongs to the same vehicle. In a positive case, the ambulance is filtered out, indicating that it is moving away from the traffic light. Following this, the ambulance vehicle, identified by the elementary visual detector, is compared with that from the previous frame, stored in memory. If the width of the ambulance has increased, the direction is considered towards the traffic light. The output is a simple flag indicating the predicted direction.

3.1.6. The AIAE Detector

This final detector takes the outputs of the: emergency detector, ambulance detector, and direction detector, to formulate the ultimate prediction. Specifically, the emergency detector and the direction detector must have their respective flags raised, indicating the detection of an emergency and the correct motion of the ambulance towards the traffic light. If these conditions are met, the overall confidence output by the ambulance detector is harnessed and stored in memory, becoming the output of the Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE) detector.

If, for three consecutive frames, the confidence returned by the AIAE detector exceeds the threshold the presence of an AIAE is stated. Also, a detected siren, retained by the emergency detector, imparts a slight boost to the confidence of AIAE obtained from the ambulance detector. Additionally, with each successive frame where the presence of an ambulance vehicle is identified, another small bonus is assigned based on its confidence.

In the tests and experiments with the Real-Time Ambulance in an Emergency Detection (RTAIAED), the threshold used is 0.85, and a detected siren contributes 0.05 towards reaching it.

3.1.7. Sw and Hw implementation of the LS

The whole set of previously described detectors has been developed using Python 3.8 (and its libraries) on a laptop running Windows 10 Home, with a NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU, an AMD Ryzen 9 5900HX with Radeon Graphics 180 3.30 GHz CPU, and 16 GB of RAM. The LS has been implemented and tested both on a Jetson Nano, equipped with NVIDIA Maxwell 182 GPU, Quad-core ARM Cortex-A57 Processor, and 4GB LPDDR4 Memory; and on a Raspberry Pi 5, featuring a 64-bit quad-core Cortex-A76 Processor with 8GB LPDDR4X Memory. All this equipment has been enclosed in a robust IP68 box, and connected to a camera and a microphone, thus forming an instance of the Lookout Station (LS).

3.2. Optimal distance of the Lookout Stations

To manage a one-way traffic scenario (for example in a rural environment where a certain road has been restricted due to repair works), we assume the presence of two traffic lights controlling alternate vehicle access. These traffic lights are positioned at both ends of the restricted tract, as depicted in

Figure 1. In this setup, two Lookout Stations are suitably positioned nearby the controlled area. One station is positioned at a certain distance before one of the two traffic lights and the other is positioned before the second traffic light on the other side, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Their primary objective is to reliably detect every AIAE approaching the restricted track from either side, thanks to the RTAIAED mounted on them. This information is then transmitted to the traffic light controller, to adjust the timing of the two traffic lights accordingly. Two cases may emerge when an AIAE is detected:

The first case is the simplest one because it’s solvable extending the duration of the green light till, at least, the entering of the ambulance in the road restriction. The second case is the one that requires the positioning of the Lookout Stations at an optimal distance from the traffic lights, to guarantee the green light to the AIAE when it enters in the road restriction. This is because the double red time (i.e., the time t3 and t6 of

Figure 2, namely the time to safely free the track of road restriction) isn’t suppressible without losing the safety of the road. So, finding the optimal distance of the Lookout Stations is crucial because they must grant the early detection of the AIAE so as to allow sufficient time to the Traffic Light Controller to change the timing of the lights properly.

The optimal position of the Lookout Stations depends on: the speed of the ambulance (e.g. 90 km/h in the majority of instances), the minimum duration time of yellow light allowed by the regulations (e.g., in Italy, according to “risoluzione del Ministero dei Trasporti n. 67906 del 16.7.2007” [

31], 3, 4 and 5 seconds respectively for the speed limits of 50, 60, 70 km/h on the road) and the duration time of the double red. This last parameter is established by companies specialized in the design, supply and installation of traffic light systems. Their goal is to deliver a secure product customized for the particular road where the system is deployed. However, for our discussion and to provide a broad understanding of the distances involved, it can be simplified as contingent on the separation between the two traffic lights placed at the ends of the constriction section. Additionally, it is influenced by the speed of the vehicles passing through the section under repair, and estimated according to the following formula:

The required time for safely changing the traffic light under the worst-case scenario where the green light is on the opposite side of the road in relation to the AIAE (ensuring the segment between the two traffic lights is entirely clear of cars), is as follows:

The calculated required time stems from the consideration that, in the worst-case scenario, a yellow light is immediately activated on the opposite side, followed by the red light. Once the red signal is initiated on the other side, the double red time commences, and only upon its completion the green light can be activated on the side of the AIAE.

Some examples of the optimal Lookout Station position respect to the nearest traffic light (optimal distance) are shown in

Table 1.

The optimal distance is based on the assumption that the ambulance is traveling at a speed of 90 km/h, as per the following formula:

This way, putting the Lookout Station at the optimal distance it’s guarantee that in the worst case, according to the hypothesis, the ambulance will arrive at the traffic light when the green light is firing at it, given that the time required for the traffic light to switch safely the lights is the one required for the ambulance at high speed to reach the nearest traffic light from the Lookout Station.

Another issue that arises pertains to how much time the green light should be maintained after the detection of an AIAE. This is crucial as the green signal must persist at least until the ambulance has reached and moved beyond the location of the nearest traffic light to the LS. Two possible approaches can be used for achieving this: installing another station at the traffic light to monitor the ambulance’s position as it passes, or, without adding any extra station, estimating a sufficiently extended time to ensure the ambulance has reached and moved past the traffic light. The minimum duration time of the green light depends on the two following scenarios:

MinGreenTime1, if there’s already a green light towards the AIAE, calculated with the formula:

MinGreenTime2, if there’s a red light towards the AIAE, that has to be switched to green light according to the required time of the formula

6:

Table 2 shows these minimum times for the duration of the green light taking the examples shown in

Table 1 and assuming the ambulance’s low speed is 40 km/h, this ensures its passage even in cases where it cannot travel at high speeds.

3.3. Communication with the Traffic Light Controller

Considering that the distances between the Lookout Station (LS) equipped with the RTAIAED and the nearest traffic light can exceed 200 meters, a long-range wireless solution is necessary to transmit the alarm signals. To optimize the implementation costs, the LoRa technology [

32] has been selected for its cost-effective modules and its ability to offer a low-power solution, reaching distances of up to 15 km with high immunity to interference. More specifically, LoRa transceiver modules, such as the SX1276 from Semtech, have been designated for placement at the Traffic Light Controller (operating as a receiver) and at each LS (operating as a transmitter).

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

The elementary detectors are evaluated according to the following metrics, where TP stands for true positives, TN for true negatives, FP for false positives and FN for false negatives. In particular, the accuracy has been used for the audio detector, calculated as follows:

For the visual detectors the metrics used are the precision and the recall, calculated as follows:

Also, the mAP50 and the mAP50-95 have been used. These metrics use the intersection over union (IoU), calculated as:

Basically, it is the ratio of the area of intersection between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes to the area of their union. mAP is then calculated as:

In it, AP (standing for average precision) is the area under the Precision-Recall curve and N is the number of object classes. mAP50 is obtained with mAP calculated for an IoU threshold of 0.5, while mAP50-95 is the mAP calculated over different IoU thresholds, from 0.5 to 0.95 with step 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the elementary audio detector

The following paragraph presents the results of the audio detector. In the validation phase, an accuracy of 99.5% was achieved after 150 epochs. During the testing phase, a distinct dataset was employed, encompassing 459 audio samples with sirens, 3,368 audio samples containing various other sounds, and 52 synthetic audio samples. The synthetic audios were generated using Audacity 3.3.3 [

33], combining siren sounds with other noisy and intense sounds. The results of the testing phase are: 418 out of 459 sirens correctly detected (8.9% of False Negatives), 3364 out of 3367 audio without sirens correctly detected (0.09% of False Positives), 56 out of 65 sirens correctly detected in the synthetic audios (13.8% of False Negatives).

Examining audio instances where sirens are not detected reveals scenarios characterized by excessively strong background noise or faint siren signals. Such cases are not deemed critical errors for the performance of the RTAIAED: since sound is assessed every second and a half, instances where a siren is not detected at a specific moment may be captured in the subsequent one. Moreover, even if the siren remains undetected throughout an ambulance’s transit, the flashing lights can still be detected, ensuring an emergency detection in any case. False negatives do not pose a significant issue, as their occurrence without concurrent ambulance detection in the video does not lead to an AIAE detection.

4.2. Results of the elementary visual detectors

The results of the model 480t on the evaluation dataset, containing 421 images, after the final iteration, are reported in

Table 3, according to the metrics usually used with YOLO models: precision, recall, mAP50 and mAP50-95.

The data shows the high performance of the ambulance’s class detection compared to the other classes. Also, the low values obtained for certain classes (in particular the mAP50-95 of flashing light, written ambulanza and red cross) are in line with or better than the values obtained in recent literature with YOLOv8 in similar detection applications [

34,

35,

36,

37] (note that the official documentation of YOLOv8 [

25] reports a 37.3% mAP50-95 on COCO with the model n).

Table 4 presents the consolidated results for all classes, sequentially listing the performance of models 640n, 640t, 480n, and 480t.

The performance of the 480t model is slightly inferior to that of the 640n model, though not significantly distant, with a small gap visible passing from the models with 640 pixels to the ones with 480 pixels. Nevertheless, owing to the implementation of the part-based-pyramidal model within the comprehensive system, it manages to yield equivalent results in terms of final predictions compared to the other three models, as demonstrated later.

4.3. Results of the ambulance detector

The learnt weights for each of the classes in input to the elementary visual detectors are: 0.9 for the ambulance vehicle (denoting only the one moving toward the camera), -0.8 for the rear ambulance vehicle (indicating the one moving away from the camera), 0.5 for the flashing light, and 0.25 for the other elements. Using these weights and setting the threshold at 0.85, with the model 480t only 12 images out of 501 without an ambulance (2.4%) resulted in false positives (from now on denoted as FPO). Conversely, 405 images out of 559 featuring an ambulance were correctly identified as true positives (72.5%) (from now on denoted as TPA), while 7 out of 320 images featuring a rear ambulance were incorrectly predicted as ambulances (2.2%) (from now on denoted as FPR).

With a threshold of 0.9, the results are respectively 10 instead of 12 (2.0%) for the FPO, 397 instead of 412 (71.0%) for the TPA and 7 like before (2.2%) for the FPR.

Instead, using a threshold of 0.8, the results are respectively 14 (2.8%) for the FPO, 427 (76.4%) for the TPA and 7 (2.2%) for the FPR. This shows that a small quantity of the images remains detected as false positive regardless of the threshold, varying less than 1% within the three thresholds, while the number of the true positives varies more.

The other models obtained similar results, reported in

Table 5 with each threshold.

Figure 8 reports the images that exceed the threshold without containing ambulances. As we can see, most of the cases are vehicles very similar to ambulances.

Figure 9 reports the images with the rear part of the ambulance that exceed the threshold. We can see that most of them have obstacles in the middle or the ambulance really far.

Also, the low rate of true positives (around 70%-80% depending on the threshold and on the model) must not be considered as a problem because a lot of images were chosen containing ambulances really distant from the camera, with poor image quality, bad lighting effect or too many obstacles in front of it, as shown in

Figure 10. Even the occurrence of false positives in images devoid of an ambulance is not problematic. This is due to the fact that even if an object is mistakenly identified as an ambulance, it will be filtered out because neither flashing lights are detected nor a siren is heard, so the "false" ambulance is not regarded as an Ambulance in an Emergency (AIAE).

4.4. Results of the RTAIED

The entire system underwent testing on 85 videos, totaling 2312 seconds (i.e. almost 39 minutes), captured during both day (70) and night (15 videos). These videos contain 94 instances of Ambulances in an Emergency (AIAEs) along with other vehicles, including emergency vehicles with sirens and trucks resembling ambulances. 13 of these videos exclusively featured vehicles similar to ambulances, all equipped with flashing lights and/or sirens, ranging from fire trucks and police cars to blood transport and civil protection vehicles. Also, 5 ambulances not in an emergency are present. Each model of the object detector was evaluated on both the Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi 5, using both default (the PyTorch one, with extension .pt, that is the official one) and ONNX formats. The smallest model, 480t, demonstrates comparable performance to other models, achieving the same detections due to additional checks implemented for consecutive frames. The RTAIAED using the 480t model produced zero false positives across all 85 videos, successfully detecting all 94 AIAEs approaching the traffic light. Notably, the system avoided misclassifying ambulances moving away from the camera as AIAEs approaching it, thanks to the double-check on the direction. Moreover, we successfully identified partially occluded AIAEs. Notably, AIAEs that were lined up and partly concealed by other vehicles were detected by focusing solely on the upper part of their vehicles. The siren of every AIAE with an activated siren was consistently recognized, typically preceding the AIAE’s appearance in the video. Although other emergency vehicles with activated sirens were detected, they were not classified as ambulances, resulting in the absence of AIAE detection. AIAEs equipped only with flashing lights were effectively identified, thanks to the detection of the emergency condition signaled by these lights. Remarkably, the RTAIAED demonstrated exceptional proficiency in detecting flashing lights during the night, facilitating the identification of a vehicle as an ambulance even when confidence was low due to limited lighting. This underscores the critical synergy between each component of the RTAIAED.

To assess the standalone performance of the elementary ambulance detector and the elementary siren detector in predicting an AIAE, a specific test has been done. For the elementary ambulance detector, confidence thresholds of 0.85 and 0.90 have been used. In

Table 6, the results of each individual detector are compared with those achieved by the overall RTAIAED, emphasizing the improvement of the RTAIAED in comparison to its elementary components.

The improvement becomes evident through the elimination of False Positives and False Negatives when employing the RTAIAED, a contrast to the occurrences observed with each elementary detector used in isolation. Specifically, when each elementary visual detector is utilized independently, it tends to misclassify all (5) non-emergency ambulances present in the videos as AIAEs. Additionally, adjusting the threshold for the elementary visual detector to classify something as an AIAE leads to a reduction in False Positives; however, this adjustment results in the omission of some AIAEs, causing an increase in False Negatives. In the case of the elementary siren detector, False Negatives were observed in instances where AIAEs had only the flashing light activated. Notably, False Positives were only registered when there was no AIAE present in the video, as the detector, when operating independently, fails to recognize the direction of ambulances. This results in a higher count of False Positives every time an AIAE moves in the opposite direction of the camera.

All YOLO models were also evaluated in terms of speed, and

Table 7 presents the mean frames per second (fps) for each model using the Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi 5. The model 480t exhibited the best results, both with the default model on the Jetson Nano and the ONNX model on the Raspberry Pi 5.

The model 480t is the preferred choice due to its high speed without compromising the accuracy of Ambulances in an Emergency (AIAEs) detection. It consistently delivers satisfactory results, especially noteworthy is its capability to perform well on the Raspberry Pi 5. Despite the Jetson Nano achieving a 44% higher frames per second (fps) compared to the Raspberry Pi 5, the latter’s fps of 8.2 is still adequate for the RTAIAED.

Tests further indicate that on a clear road without traffic, when an AIAE is moving at high speed, the detection by RTAIAED occurs 3-4 seconds before the AIAE disappears from the camera’s field of view, surpassing it. This highlights the RTAIAED’s ability to detect AIAEs even at a distance, providing crucial additional time to take timely proactive actions.

5. Discussion

The executed tests demonstrate the robust performance of the Real-Time Ambulance in an Emergency Detection (RTAIAED) system across diverse conditions. The pyramidal part-based system plays a crucial role in efficiently mitigating false positives generated by individual elementary detectors, highlighting the synergy among its multiple components in accurately detecting targeted objects while filtering out irrelevant information.

Our solution has been implemented successfully for Italian ambulances, demonstrating its capability to detect all types currently in circulation in Italy. The adaptable nature of the concept allows for its potential extension to ambulances from other nations or states, incorporating specific elements or even expanding its application to other emergency vehicles by training the elementary object detector models accordingly.

Moreover, the architecture of the RTAIAED is versatile and can be applied to various domains where different features of an object of interest can be independently detected and then merged in a pyramidal manner to yield a robust final decision. While future developments and fine-tuning, such as speeding up with quantization or pruning techniques [

38], are feasible, the current state establishes it as a fully operational product.

It is crucial to highlight the importance of optimal camera placement for achieving the best results. The camera should be positioned at a sufficient height to detect ambulances even when partially obstructed by vehicles or obstacles, facing the opposite direction compared to the traffic flow. Without the need for additional hardware, a simple modification to the object detector introduces two new classes for detecting vehicles in different directions of travel, paving the way for implementing solutions to alleviate traffic congestion.

The RTAIAED not only serves as an effective tool for emergency vehicle detection but also holds potential applications in intelligent traffic management. It can send signals to smart or autonomous vehicles in the proximity where an AIAE has been detected, alerting them or even lowering automatic road bollards when an AIAE is approaching.

In conclusion, the proposed work exhibits significant potential impact due to its cost-effectiveness, performance, and accuracy. Its practical applicability makes it a viable and versatile solution for various real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and C.G.; methodology, A.M. and C.G.; software, C.G.; validation, C.G.; formal analysis, C.G.; investigation, C.G.; resources, C.G.; data curation, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, C.G.; supervision, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A.I. |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AIAE |

Ambulance in an Emergency |

| AP |

Average Precision |

| FPO |

Other vehicle or other parts in an image classified as ambulance |

| FPR |

Rear ambulance classified as ambulance |

| GSM |

Global System for Mobile Communications |

| IoU |

Intersection over Union |

| LS |

Lookout Station |

| NN |

Neural Network |

| MFCCs |

Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| PDA |

Personal Digital Assistant |

| RFID |

Radio Frequency Identification |

| RTAIAED |

Real-Time Ambulance in an Emergency Detector |

| SUEM |

Urgency and Medical Emergency Service |

| TL |

Traffic Light |

| TLC |

Traffic Light Controller |

| TPA |

True Positive of ambulance |

References

- ISTAT. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2023/07/REPORT_INCIDENTI_STRADALI_2022_IT.pdf; p. 12; (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Ray, A.F.; Kupas, D.F. Comparison of crashes involving ambulances with those of similar-sized vehicles. Prehospital emergency care 2005, 9, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, C. A.; Pirrallo, R. G; Kuhn, E. M., Characteristics of fatal ambulance crashes in the United States: An 11-year retrospective analysis. Prehospital Emergency Care, Volume 5, Issue 3, 2001, Pages 261-269. [CrossRef]

- Inrix. Available online: https://inrix.com/scorecard/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Wiwekananda, K.S.; Hamukti, R.P.; Yogananda, K.S.; Calisto, K.E.; Utomo, P.S., Understanding factors of ambulance delay and crash to enhance ambulance efficiency: an integrative literature review. 2020.

- Mousavi, S.S.; Schukat, M.; Howley, E., Traffic light control using deep policy-gradient and value-function-based reinforcement learning. IET Intell. Transp. Syst., 11: 417-423, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Hu, X.; Wang, G., PDLight: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Traffic Light Control Algorithm with Pressure and Dynamic Light Duration. 29 September 2020. [CrossRef]

- Felzenszwalb, P. F.; Girshick, R. B.; McAllester, D.; Ramanan, D., Object Detection with Discriminatively Trained Part-Based Models. In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 32, no. 9, pp. 1627-1645, September 2010. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Du, X.; Wang, G.; Han, Z., A Deep Reinforcement Learning Network for Traffic Light Cycle Control. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 1243-1253, February 2019. 20 February. [CrossRef]

- Wiering, M.A.; van Veenen, J.; Vreeken, J.; Koopman, A., Intelligent Traffic Light Control. Utrech University: Utrech, The Netherlands, 2004.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, W.-P., Intelligent traffic light control using distributed multi-agent Q learning. 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Yokohama, Japan, 2017, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Espinoza, A.; López-Bonilla, O.R.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; López-Mancilla, D.; Hernández-Mejía, C.; Inzunza-González, E. Traffic Flow Prediction for Smart Traffic Lights Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Technologies 2022, 10, 5 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronanetwork. Available online: https://daily.veronanetwork.it/economia/vai-118-codice-rosso-scattare-verde/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Ford Media Center. Available online: https://media.ford.com/content/fordmedia/feu/en/news/2022/03/29/ford_s-smart-traffic-lights-go-green-for-emergency-vehicles-.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Siddiqi, M.H.; Alruwaili, M.; Tarimer, İ.; Karadağ, B.C.; Alhwaiti, Y.; Khan, F. Development of a Smart Signalization for Emergency Vehicles. Sensors 2023, 23, 4703 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Abdel-Aty, M., Real-time Emergency Vehicle Event Detection Using Audio Data, 3 February 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Gonzalez, A.; Torres, R.; Chacon, R.; Robledo, I., Real-Time Emergency Vehicle Detection using Mel Spectrograms and Regular Expressions. 25 September 2023. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Barbosa, R.; Shoaib Ayub, M.; Lopes Rosa, R.; Zegarra Rodríguez, D.; Wuttisittikulkij, L. Lightweight PVIDNet: A Priority Vehicles Detection Network Model Based on Deep Learning for Intelligent Traffic Lights. Sensors 2020, 20, 6218 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Pithora, A.; Gupta, G.; Goel, M.; Sinha, M. Traffic light priority control for emergency vehicle using RFID. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2, 363–366. [Google Scholar]

- Eltayeb, A.S.; Almubarak, H.O.; Attia, T.A., A GPS based traffic light pre-emption control system for emergency vehicles. In 2013 international conference on computing, electrical and electronic engineering (icceee) (pp. 724-729), IEEE, August 2013. [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M. A.; R. A. Elschlager, R. A., The Representation and Matching of Pictorial Structures. IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. C-22, no. 1, pp. 67-92, January 1973. [CrossRef]

- Fergus, R.; Perona, P.; Zisserman, A., Object class recognition by unsupervised scale-invariant learning. 2003 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2003. Proceedings., Madison, WI, USA, 2003, pp. II-II. [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron Markets 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A., You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. 8 June 2015.

- Github. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- COCO. Available online: https://cocodataset.org/#home (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Ke, X.; Zeng, G.; Guo, W. An Ultra-Fast Automatic License Plate Recognition Approach for Unconstrained Scenarios. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 5172–5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Feng, X. , Multi-Object Pedestrian Tracking Using Improved YOLOv8 and OC-SORT. Sensors 2023, 23, 8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Github. Available online: https://github.com/HumanSignal/labelImg (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Abdul, Z. K.; Al-Talabani, A. K., Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficient and its Applications: A Review. IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 122136-122158, 2022. [CrossRef]

- ASAPS. Available online: https://www.asaps.it/56495-_nota_16_07_2007_n_67906_-_ministero_dei_trasporti_tempi_della_durata_del_giallo.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Sneha; Malik, P. K., Naveen Bilandi, N.; Gupta, A., Narrow band-IoT and long-range technology of IoT smart communication: Designs and challenges. Computers & Industrial Engineering, Volume 172, Part A, 2022, 108572, ISSN 0360-8352. [CrossRef]

- Audacity, T., Audacity. The Name Audacity (R) Is a Registered Trademark of Dominic Mazzoni, 2017. Retrieved from http://audacity.sourceforge.net; (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; An, P.; Hong, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, T. UAV-YOLOv8: A Small-Object-Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8 for UAV Aerial Photography Scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23, 7190 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Duan, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, H.; Gu, J.; Bi, L.; Chen, H. DC-YOLOv8: Small-Size Object Detection Algorithm Based on Camera Sensor. Electronics 2023, 12, 2323 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Hao, F.; Ma, D. Research on Polygon Pest-Infected Leaf Region Detection Based on YOLOv8. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2253 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Muhammad, N. Object Detection in Adverse Weather for Autonomous Driving through Data Merging and YOLOv8. Sensors 2023, 23, 8471 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadera, S.; S. Ameen, S., Methods for Pruning Deep Neural Networks. In IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 63280-63300, 2022. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Unidirectional traffic managed by a traffic light system.

Figure 1.

Unidirectional traffic managed by a traffic light system.

Figure 2.

Traffic light cycle to manage unidirectional traffic.

Figure 2.

Traffic light cycle to manage unidirectional traffic.

Figure 3.

Unidirectional traffic managed by a traffic light system with the proposed solution.

Figure 3.

Unidirectional traffic managed by a traffic light system with the proposed solution.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the RTAIAED.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the RTAIAED.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the siren detector

Figure 5.

Architecture of the siren detector

Figure 6.

Histogram of the instances used in the training dataset

Figure 6.

Histogram of the instances used in the training dataset

Figure 7.

Written texts and symbols shown as they appear in the frames

Figure 7.

Written texts and symbols shown as they appear in the frames

Figure 8.

False positives: other vehicles identified as ambulances in at least one model.

Figure 8.

False positives: other vehicles identified as ambulances in at least one model.

Figure 9.

False positives: rear ambulances identified as ambulances (so, front part) in at least one model.

Figure 9.

False positives: rear ambulances identified as ambulances (so, front part) in at least one model.

Figure 10.

Some of the false negatives: ambulances not detected

Figure 10.

Some of the false negatives: ambulances not detected

Table 1.

Examples of recommended distances for the lookout station from the nearest traffic light.

Table 1.

Examples of recommended distances for the lookout station from the nearest traffic light.

Yellow

Time (s)

|

Vehicle

Speed (km/h)

|

Road

Length (m)

|

Required

Time (s)

|

Optimal

Distance (m)

|

| 3 |

50 |

200 |

17.4 |

435 |

| 5 |

70 |

200 |

15.2 |

382 |

| 3 |

50 |

400 |

31.8 |

795 |

| 5 |

70 |

400 |

25.6 |

639 |

| 3 |

50 |

600 |

46.2 |

1155 |

| 5 |

70 |

600 |

35.9 |

896 |

Table 2.

Examples of minimum time of green light.

Table 2.

Examples of minimum time of green light.

Yellow

Time (s)

|

Vehicle

Speed (km/h)

|

Road

Length (m)

|

Min Green

Time 1 (s)

|

Min Green

Time 2 (s)

|

Optimal

Distance (m)

|

| 3 |

50 |

200 |

39.2 |

21.8 |

435 |

| 5 |

70 |

200 |

34.4 |

19.2 |

382 |

| 3 |

50 |

400 |

71.6 |

39.8 |

795 |

| 5 |

70 |

400 |

57.5 |

31.9 |

639 |

| 3 |

50 |

600 |

104.0 |

57.8 |

1155 |

| 5 |

70 |

600 |

80.6 |

44.7 |

896 |

Table 3.

Results on the evaluation dataset of the object detector model 480t.

Table 3.

Results on the evaluation dataset of the object detector model 480t.

| Class |

Instances |

Precision |

Recall |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

| All |

1758 |

81.6% |

70.9% |

78.1% |

54.6% |

| Ambulance |

314 |

82.9% |

89.7% |

93.3% |

80.0% |

| Flashing Light |

196 |

76.3% |

69.9% |

77.0% |

43.7% |

| Star of Life |

482 |

87.7% |

71.0% |

80.6% |

52.5% |

| Written Ambulanza |

130 |

72.6% |

53.8% |

58.1% |

38.5% |

| Written Ambulanza Reversed |

200 |

81.1% |

82.0% |

86.1% |

55.9% |

| Rear Ambulance |

161 |

81.3% |

77.0% |

86.5% |

68.8% |

| Red Cross |

275 |

89.5% |

52.5% |

65.3% |

42.6% |

Table 4.

Aggregated results on the evaluation dataset of the models 640n, 640t, 480n, 480t.

Table 4.

Aggregated results on the evaluation dataset of the models 640n, 640t, 480n, 480t.

| Model |

Precision |

Recall |

mAP50 |

mAP50-95 |

| 640n |

85.7% |

76.0% |

82.6% |

60.6% |

| 640t |

88.4% |

73.4% |

83.5% |

59.7% |

| 480n |

82.3% |

70.0% |

77.0% |

54.6% |

| 480t |

81.6% |

70.9% |

78.1% |

54.6% |

Table 5.

False positives and false negatives of all the models with 0.8, 0.85 and 0.9 thresholds.

Table 5.

False positives and false negatives of all the models with 0.8, 0.85 and 0.9 thresholds.

| Model |

FPO - TPA - FPR 0.8 |

FPO - TPA - FPR 0.85 |

FPO - TPA - FPR 0.9 |

| 640n |

3.8% - 79.8% - 1.9% |

3.0% - 76.0% - 1.6% |

2.8% - 74.8% - 1.6% |

| 640t |

3.8% - 78.2% - 0.9% |

3.2% - 74.8% - 0.9% |

3.0% - 73.5% - 0.9% |

| 480n |

3.2% - 77.1% - 1.6% |

2.2% - 72.5% - 1.6% |

2.0% - 71.7% - 1.3% |

| 480t |

2.8% - 76.4% - 2.2% |

2.4% - 72.5% - 2.2% |

2.0% - 71.0% - 2.2% |

Table 6.

True Positives, False Positives and False Negatives of the RTAIAED and its elementary detectors alone.

Table 6.

True Positives, False Positives and False Negatives of the RTAIAED and its elementary detectors alone.

| Detector |

TP |

FP |

FN |

Ambulance Detector

with threshold 0.85 |

94 |

21 |

0 |

Ambulance Detector

with threshold 0.90 |

92 |

7 |

2 |

| Siren Detector |

89 |

11 |

5 |

| RTAIAED |

94 |

0 |

0 |

Table 7.

Comparison of the fps reached by the various models.

Table 7.

Comparison of the fps reached by the various models.

| Model |

Format |

FPS

Jetson Nano

|

FPS

Raspberry Pi 5

|

| 640n |

default |

6.3 |

2.0 |

| 640n |

onnx |

6.8 |

3.9 |

| 640t |

default |

6.9 |

2.0 |

| 640t |

onnx |

7.8 |

4.5 |

| 480n |

default |

10.1 |

2.6 |

| 480n |

onnx |

9.7 |

7.0 |

| 480t |

default |

11.8 |

2.8 |

| 480t |

onnx |

10.1 |

8.2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).