Submitted:

23 January 2024

Posted:

24 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

2. METHODS

2.1. Identification and selection of websites

2.2. Data extraction

2.3. Data capture forms

2.4. Scoring

2.5. Data analysis

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Website navigation

3.2. Council MoWs provision

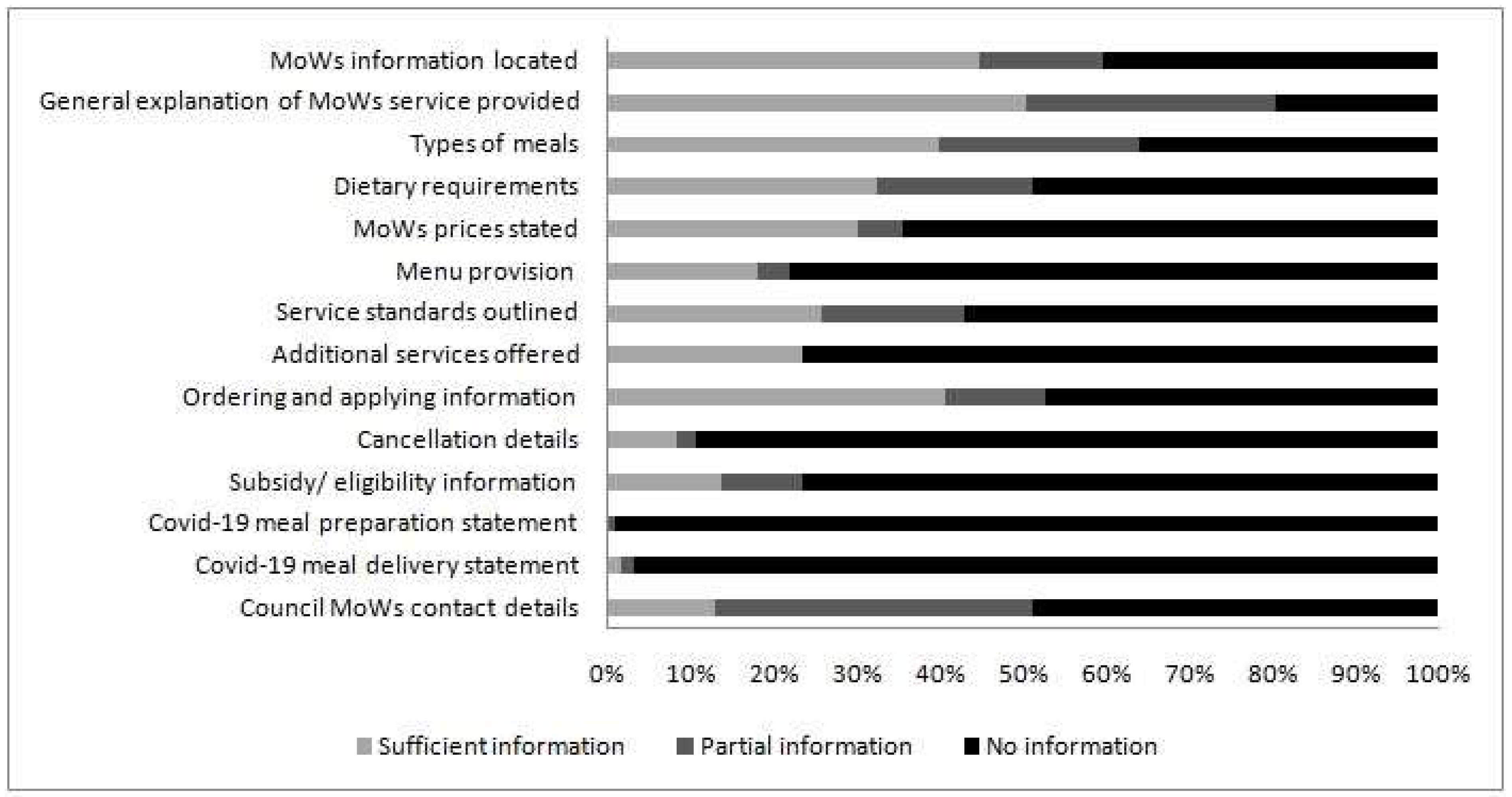

3.3. MoWs information provision

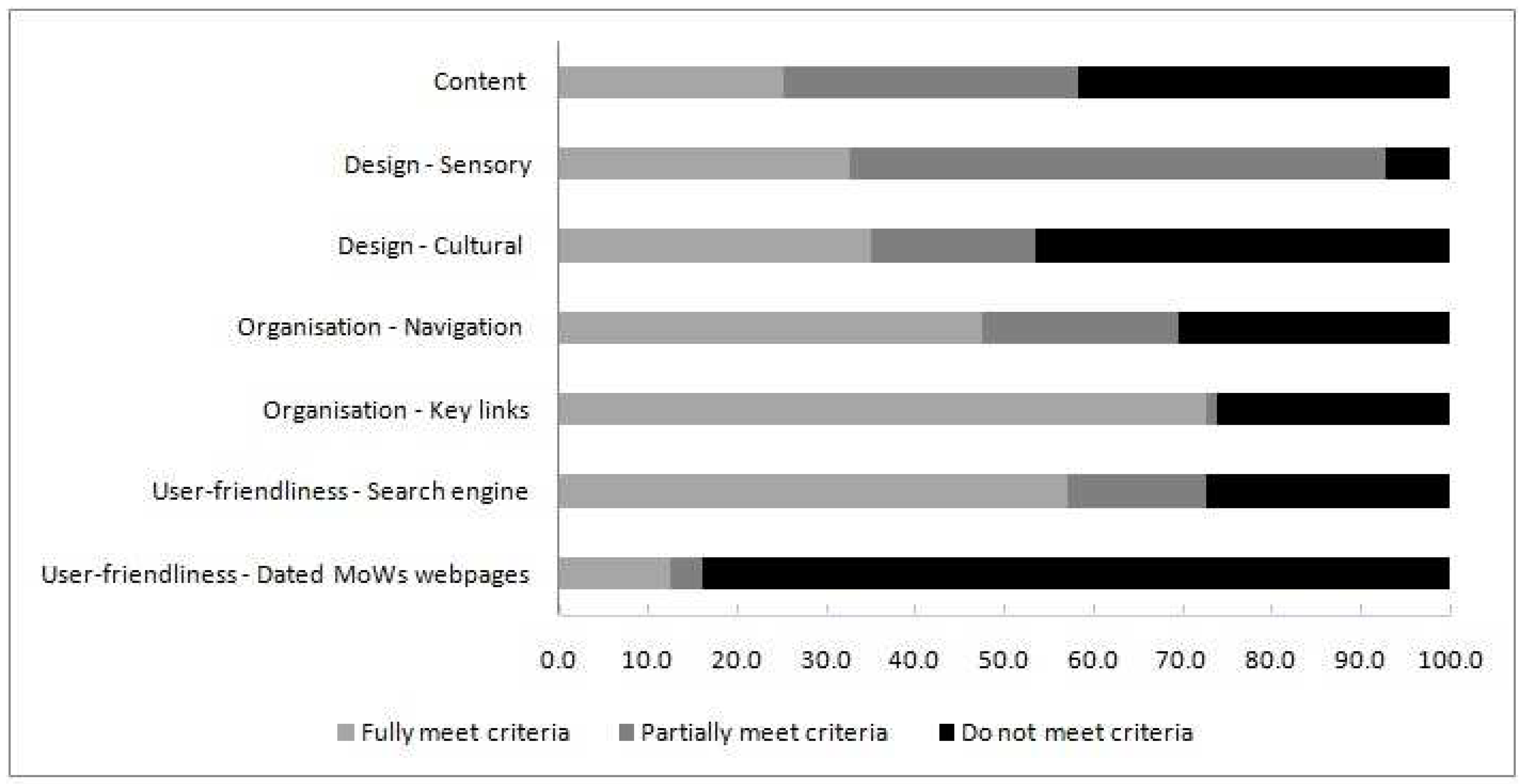

3.4. Website quality

3.5. Overall scores

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Strengths and limitations

4.2. Implications

5. CONCLUSIONS

Supplementary material

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, H. and R. An, Impact of home-delivered meal programs on diet and nutrition among older adults: a review. Nutr Health, 2013. 22(2): p. 89-103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.S., U. Akobundu, and D. Dosa, More Than A Meal? A Randomized Control Trial Comparing the Effects of Home-Delivered Meals Programs on Participants' Feelings of Loneliness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 2016. 71(6): p. 1049-1058. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, A., et al., 'It's not just about the dinner; it's about everything else that we do': A qualitative study exploring how Meals on Wheels meet the needs of self-isolating adults during COVID-19. Health Soc Care Community, 2022. 30(5): p. e2012-e2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.S., et al., "It's Not Just a Simple Meal. It's So Much More": Interactions Between Meals on Wheels Clients and Drivers. J Appl Gerontol, 2020. 39(2): p. 151-158. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, M.C., et al., Home Delivered Meals to Older Adults: A Critical Review of the Literature. Home Healthc Now, 2018. 36(3): p. 159-168. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahyoun, N.R. and A. Vaudin, Home-Delivered Meals and Nutrition Status Among Older Adults. Nutr Clin Pract, 2014. 29(4): p. 459-465. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, S.A., et al., Meal Delivery Programs Reduce The Use Of Costly Health Care In Dually Eligible Medicare And Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood), 2018. 37(4): p. 535-542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Age UK, Older people stripped of their meals on wheels. Available at: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/latest-press/archive/older-people-stripped-of-their-meals-on-wheels-service/. Accessed 18 June 2022. 2015.

- Sustain. British pensioners need meals on wheels to beat Covid-19. Available at: https://www.sustainweb.org/blogs/apr20_one_million_pensioners_need_meals_on_wheels/#:~:text=This%20week%2C%20government%20food%20parcels,week%20over%20the%20next%20month. Accessed 10 March 2021. 2020.

- Charlton, K.E., et al., Meals on Wheels: Who's referring and what's on the menu? Australas J Ageing, 2019. 38(2): p. e50-e57. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center, Tech Adoption Climbs Among Older Adults. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/. Accessed 21 June 2022. 2017.

- Office for National Statistics, Internet users, UK: 2020. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2020. Accessed 21 June 2022. 2020.

- UK Government, Care Act 2014. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/pdfs/ukpga_20140023_en.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2022. 2014.

- UK Government, The Adult Social Care Outcomes Framework 2018/19 Handbook of Definitions. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/687208/Final_ASCOF_handbook_of_definitions_2018-19_2.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2022. 2018.

- UK Government, Get meals at home (meals on wheels). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/meals-home. Accessed 14 October 2022. n.d.

- National Association of Care Catering, Meals on Wheels Survey 2018. Available at: https://www.publicsectorcatering.co.uk/sites/default/files/attachment/nacc_-_meals_on_wheels_report_2018.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2021. 2018.

- Lloyd, L. and T. Jessiman, Support for Older Carers of Older People: The Impact of the 2014 Care Act Phase 1: Review of information on support for carers on local authority websites in England. Available at: https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/187889890/Support_for_older_carers_of_older_people.pdf. Accessed 15 October 2022. 2017.

- Local Government Information Unit, Local government facts and figures: England. Available at: https://lgiu.org/local-government-facts-and-figures-england/#section-3. Accessed 15 October 2022. 2021.

- UK Government, Local government structure and elections. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/local-government-structure-and-elections. Accessed 15 October 2022. 2019.

- Law Wales, Local government bodies. Available at: https://law.gov.wales/local-government-bodies. Accessed 29 June 2022. 2021.

- Scottish Government, Organisations. Available at: https://www.mygov.scot/organisations#scottish-local-authority. Accessed 15 October 2022. n.d.

- NI Direct, Local councils in Northern Ireland. Available at: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/contacts/local-councils-in-northern-ireland. Accessed 29 June 2022. n.d.

- Wilson, A., The use of mystery shopping in the measurement of service delivery. Service Industries J, 1998. 18(3): p. 148-163. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.-L., et al., Supporting carers following the implementation of the Care Act 2014: eligibility, support and prevention. The Carers in Adult Social Care (CASC) study end-of-project report. Available at: https://www.lse.ac.uk/cpec/assets/documents/cascfinalreport.pdf. Accessed 15 October 2022. 2020.

- Healthwatch Islington, Phoning Adult Social Services A mystery shopping investigation. Available at: https://www.healthwatchislington.co.uk/sites/healthwatchislington.co.uk/files/Phoning%20Adult%20Social%20Services.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2021. 2017.

- Sandwell & West Birmingham CCG, CCG Mystery Shoppers. Available at: https://sandwellandwestbhamccg.nhs.uk/mysteryshopper. Accessed 10 June 2021. 2019.

- Willis, P., et al., Online advice to carers: an updated review of local authority websites in England. Available at: https://www.sscr.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/SSCR-research-findings_RF163.pdf. Accessed 15 October 2022. 2021.

- Choudrie, J., G. Ghinea, and V. Weerakkody, Evaluating global e-government sites: A view using web diagnostic tools. Electronic Journal of E-Government, 2004. 2.

- Kokkinaki, A.I., S. Mylonas, and S. Mina, E-Government Initiatives in Cyprus. In: Proceedings of E-Government Workshop’05 (EGOV05). 2005.

- Food Standards Agency, Adapting food manufacturing operations during COVID-19. Available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/adapting-food-manufacturing-operations-during-covid-19. Accessed 15 June 2021. 2020.

- Food Standards Agency, Adapting restaurants and food delivery during COVID-19. Available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/adapting-restaurants-and-food-delivery-during-covid-19. Accessed 15 June 2021. 2021.

- Hasan, L. and E. Abuelrub, Assessing the quality of web sites. Appl Comp Informatics, 2011. 9: p. 11–29. [CrossRef]

- Worsell, D., Putting customers at the heart of your services. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/guidance-and-resources/comms-hub-communications-support/futurecomms-building-local-14. Accessed May 2021. 2021.

- Porter, J., Testing the Three-Click Rule. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265283936_Testing_the_Three-Click_Rule. Accessed 10 June 2021. 2003.

- Porter, T. and R. Miller, Investigating the Three-Click Rule: A Pilot Study. MWAIS 2016 Proceedings. 2. Available at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/mwais2016/2. Accessed 10 June 2021. 2016.

- Plain English Campaign, Tips for clear websites. Available at: http://www.plainenglish.co.uk/files/websitesguide.pdf. Accessed 2 August 2021. n.d.

- Fernandez, J.-L., T. Snell, and J. Marczak, An assessment of the impact of the Care Act 2014 eligibility regulations. Available at: https://www.pssru.ac.uk/pub/5141.pdf. Accessed 9 September 2023. 2015.

- Charnock, D., et al., DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health, 1999. 53(2): p. 105-11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, C.E., J.E. Ford, and C.E. Sheard, Evaluating the reliability of DISCERN: a tool for assessing the quality of written patient information on treatment choices. Patient Educ Couns, 2002. 47(3): p. 273-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Directors of Adults Social Services, Socitm Insight, and Local Government Association, Methodology for developing the online user journey. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/download-briefing-2-metho-21f.pdf. Accessed 28 November 2022. 2015.

- Cichero, J.A.Y., Age-Related Changes to Eating and Swallowing Impact Frailty: Aspiration, Choking Risk, Modified Food Texture and Autonomy of Choice. Geriatrics (Basel), 2018. 3(4). [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, S., et al., The risk of dysphagia is associated with malnutrition and poor functional outcomes in a large population of outpatient older individuals. Clin Nutr, 2019. 38(6): p. 2684-2689. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. and K. Dennison, Meals on wheels service: Knowledge and perceptions of health professionals and older adults. Nutr Diet, 2011. 68: p. 155–160.

- The Health Foundation, Spring Statement 2022: What does rising inflation mean for health and social care?. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/spring-statement-2022. Acessed 30 November 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Berg, V., Care home fees and costs: How much do you pay? Available at: https://www.carehome.co.uk/advice/care-home-fees-and-costs-how-much-do-you-pay. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2022.

- Wright, L., et al., The Impact of a Home-Delivered Meal Program on Nutritional Risk, Dietary Intake, Food Security, Loneliness, and Social Well-Being. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr, 2015. 34(2): p. 218-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Government, Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK. Available at: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases. Accessed 28 August 2022. 2022.

- Mohapatra, R.K., et al., SARS-CoV-2 and its variants of concern including Omicron: A never ending pandemic. Chem Biol Drug Des, 2022. 99(5): p. 769-788. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19: Understanding risk. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/understanding-risk.html. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2022.

- UK Government, The Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) Accessibility Regulations 2018. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2018/852/signature/made. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2018.

- UK Government, Understanding accessibility requirements for public sector bodies. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/accessibility-requirements-for-public-sector-websites-and-apps. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2022.

- Frongillo, E.A., et al., Who are the recipients of Meals-on-Wheels in New York City?: A profile of based on a representative sample of Meals-on-Wheels recipients, Part I. Care Manag J, 2010. 11(1): p. 19-40. [CrossRef]

- Choudrie, J., G. Ghinea, and V. Songonuga, Silver Surfers, E-government and the Digital Divide: An Exploratory Study of UK Local Authority Websites and Older Citizens. Interact Comput, 2013. 25: p. 417-442. [CrossRef]

- NHS, Loneliness in older people. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/feelings-and-symptoms/loneliness-in-older-people/. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2022.

- Greenwood, N., et al., Barriers to access and minority ethnic carers' satisfaction with social care services in the community: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative literature. Health Soc Care Community, 2015. 23(1): p. 64-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laubheimer, P., The 3-click rule for navigation is false. Available at: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/3-click-rule/. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2019.

- Williams, N., Why GOV.UK content should be published in HTML and not PDF. Available at: https://gds.blog.gov.uk/2018/07/16/why-gov-uk-content-should-be-published-in-html-and-not-pdf/. Accessed 30 November 2022. 2018.

- Office for National Statistics, Internet access – households and individuals, Great Britain: 2018. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2018. Accessed 29 November 2022. 2018.

- Manthorpe, J., et al., Local Online Information for Carers in England: Content and Complexity. Practice, 2023: p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Willis, P.B., et al., Online advice to carers: an updated review of local authority websites in England. NIHR School for Social Care Research. 2021.

- NHS, The NHS Long Term Plan. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf. Accessed 18 October 2022. 2019.

- Social Care Institute for Excellence, Prevention in social care. Available at: https://www.scie.org.uk/prevention/social-care. Accessed 29 November 2022. 2021.

- Malnutrition Taskforce, Malnutrition in England factsheet. Available at: https://www.malnutritiontaskforce.org.uk/resources/malnutrition-england-factsheet. Accessed 14 October 2022. 2019.

- Lee, J.S., E.A. Frongillo, and C.M. Olson, Understanding targeting from the perspective of program providers in the elderly nutrition program. J Nutr Elder, 2005. 24(3): p. 25-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, A., et al., Accessing Meals on Wheels: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Experiences of Service Users and People Who Refer Them to the Service. 2023, Preprints. [CrossRef]

| England (n = 158) |

Wales (n = 22) |

Scotland (n = 32) |

Northern Ireland (n = 11) |

Total (local authority) (n = 223) |

3rd-party providers (n = 48) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website navigation | ||||||

| Home page directs to MoWs (yes) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 46 (95.8) |

| Sub-pages direct to MoWs (yes) | 107 (67.7) | 9 (40.9) | 16 (50.0) | 1 (9.1) | 133 (59.6) | 40 (83.3) |

| Search engine available (yes) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12 (25.0) |

| Navigation issues necessitated search engine use (yes) | 72 (45.6) | 15 (68.2) | 20 (62.5) | 10 (90.9) | 117 (52.5) | 2 (4.2) |

| Navigation issues necessitated search engine use and MoWs information was successfully locateda | 27 (17.1) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (14.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Use of search engine successfully located MoWs information (yes)b | 98 (62.0) | 9 (40.9) | 15 (46.9) | 1 (9.1) | 123 (55.2) | 5 (10.4) |

| Council MoWs provision | ||||||

| Council key provider (yes) | 21 (13.3) | 7 (31.8) | 6 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (15.2) | N/A |

| Council contracts out to external supplier (yes) | 13 (8.2) | 1 (4.5) | 5 (15.6) | 1 (9.1) | 20 (9.0) | N/A |

| 3rdparty supplier with link (yes) | 74 (46.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 77 (34.5) | N/A |

| 3rdparty supplier without link (yes) | 7 (4.4) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.0) | N/A |

| Council does not provide MoWs, does not signpost or provides no information about who the MoWs provider is | 43 (27.2) | 13 (59.1) | 17 (53.1) | 10 (90.9) | 83 (37.2) | N/A |

| MoWs information provisionc | ||||||

| MoWs information located | 106 (67.1) | 10 (45.4) | 16 (50.0) | 1 (9.1) | 133 (59.6) | N/A |

| General explanation of MoWs service providedd | 85 (80.2) | 9 (90.0) | 12 (75.0) | 1 (100.0) | 107 (80.5) | 45 (93.8) |

| Types of meals outlinedd | 64 (60.4) | 8 (80.0) | 12 (75.0) | 1 (100.0) | 85 (63.9) | 44 (91.7) |

| Specific dietary requirements catered ford | 53 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 9 (56.3) | 0 (0.0) | 68 (51.1) | 37 (77.1) |

| Prices statedd | 30 (28.3) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (62.5) | 1 (100.0) | 47 (35.3) | 33 (68.8) |

| Menu publishedd | 22 (20.8) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (21.8) | 37 (77.1) |

| Service standards outlinedd | 42 (39.6) | 5 (50.0) | 10 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 57 (42.9) | 39 (81.3) |

| Extra services offeredd | 22 (20.8) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (100.0) | 31 (23.3) | 15 (31.3) |

| How to order/apply informationd | 50 (47.2) | 8 (80.0) | 11 (68.8) | 1 (100.0) | 70 (52.6) | 39 (81.3) |

| Cancellation detailsd | 9 (8.5) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (10.5) | 14 (29.2) |

| Subsidy/eligibility information and/or contact detailsd | 18 (17.0) | 5 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (23.3) | N/A |

| COVID-19 safe meal preparation statementd | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (4.2) |

| COVID-19 safe delivery statementd | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.0) | 6 (12.5) |

| Council/ 3rd-party provider MoWs contact detailsd | 49 (31.0) | 6 (60.0) | 12 (75.0) | 1 (100.0) | 68 (51.1) | 4 (8.3) |

| Website qualityc | ||||||

| Content | 104 (65.8) | 10 (45.5) | 15 (46.9) | 1 (9.1) | 130 (58.3) | 48 (100.0) |

| Design - Sensory | 150 (94.9) | 21 (95.5) | 26 (81.3) | 10 (90.9) | 207 (92.8) | 4 (8.3) |

| Design - Cultural | 77 (48.7) | 21 (95.5) | 11 (34.4) | 10 (90.9) | 119 (53.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Organisation - Navigation | 96 (60.7) | 21 (95.5) | 27 (84.4) | 6 (54.5) | 155 (69.5) | 48 (100.0) |

| Organisation - Key links | 104 (65.8) | 21 (95.5) | 29 (90.6) | 11 (100.0) | 165 (73.9) | 48 (100.0) |

| User-friendliness - Search engine | 135 (85.4) | 10 (45.5) | 16 (50.0) | 1 (9.1) | 162 (72.7) | 8 (16.7) |

| User-friendliness - Dated MoWs webpages | 23 (14.5) | 6 (27.3) | 6 (18.8) | 1 (9.1) | 36 (16.2) | 10 (20.8) |

| England (n = 158) |

Wales (n = 22) |

Scotland (n = 32) |

Northern Ireland (n = 11) |

Total (local authority) (n = 223) |

3rd-party providers (n = 48) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website navigationa (maximum score = 4 for local authority websites; maximum score = 5 for 3rd-party provider websites) |

1.8 (1.2, 0-3) | 1.1 (1.4, 0-3) | 1.3 (1.4, 0-3) | 0.3 (0.9, 0-3) | 1.6 (1.3, 0-3) | 3.1 (0.8, 2-5) |

| Council MoWs provisiona (maximum score = 4 for local authority websites) |

0.7 (0.6, 0-2) | 0.4 (0.5, 0-1) | 0.4 (0.5, 0-1) | 0.1 (0.3, 0-1) | 0.6 (0.6, 0-2) | N/A |

| MoWs information provisiona (maximum score = 28 for local authority websites; maximum score = 24 for 3rd-party provider websites) |

5.8 (6.6, 0-21) | 5.9 (8.3, 0-22) | 5.7 (7.6, 0-24) | 0.9 (3.0, 0-10) | 5.6 (6.9, 0-24) | 12.3 (3.8, 3-21) |

| Website qualitya (maximum score = 14) |

7.1 (3.1, 1-13) | 8.3 (2.4, 6-13) | 6.9 (3.2, 1-14) | 7.3 (1.1, 6-10) | 7.2 (3.0, 1-14) | 6.0 (1.4, 4-11) |

| Total scorea (maximum score = 50 for local authority websites; maximum score = 43 for 3rd-party provider websites) |

15.5 (10.4, 1-38) | 15.7 (12.0, 6-37) | 14.4 (11.9, 3-40) | 8.9 (5.2, 6-24) | 14.9 (10.6, 1-40) | 21.4 (5.3, 10-35) |

|

Overall quality of MoWs online provisionb Very good (total score ≥35 points for local authority websites; total score ≥30 points for 3rd-party provider websites) Good (total score = 30-34 points for local authority websites; total score = 25-29 points for 3rd-party provider websites) Acceptable (total score = 25-29 points for local authority websites; total score = 20-24 points for 3rd-party provider websites) Requires improvement (total score ≤24 points for local authority websites; total score ≤19 points for 3rd-party provider websites) |

4 (2.5) 19 (12.0) 14 (8.9) 121 (76.6) |

4 (18.2) 1 (4.5) 0 (0.0) 17 (77.3) |

1 (3.1) 5 (15.6) 4 (12.5) 22 (68.8) |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 11 (100.0) |

9 (4.0) 25 (11.2) 18 (8.1) 171 (76.7) |

3 (6.3) 9 (18.8) 19 (39.6) 17 (35.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).