1. Introduction

The field of 3D motion analysis, particularly in sports, home fitness, and healthcare, is rapidly evolving with several advanced technologies emerging in the market. In 2023, the global 3D motion capture market is anticipated to generate US

$ 377.3 million. To reach a market size of US

$ 1,165.1 million by 2033, the market is likely to expand at a CAGR of 11.9% [

1].

There are two clear options in motion capture technology – marker/optical systems that often use infrared cameras and reflective markers, and markerless motion capture (MLMC) system that are growing in popularity due to lower costs and ease of use for less complex tasks like treadmill analysis in running. This technology offers detailed 3D analysis of the body's walking pattern or gait, which is instrumental in identifying neurological conditions like Parkinson's disease [

2]. Unlike traditional motion analysis, MLMC system doesn't require markers on the body, thus simplifying the process significantly.

An alternative method for motion capture involves the use of IMU Sensors, which encompass accelerometers and gyroscopes [

3]. Although they don't offer the exhaustive data capture of full-body systems, these sensors effectively capture motion to a significant degree. Wearable body suits equipped with IMU Sensors are gaining popularity due to their portability. Commonly utilized in clinical environments, they offer less data detail and precision compared to high-performance systems, yet remain a practical choice for certain applications.

Motion capture technology is widely used in gait analysis for sports, essential in activities involving running motions. In sports medicine, it is employed to study athletes' movements, identifying dysfunctions related to injuries [

4]. This technology is crucial in understanding athletes' success and handling complex injuries. Additionally, MLMC technology has been tested in community settings. It's particularly useful for identifying neurological impairments and tracking rehabilitation progress.

Current 3D HPE methods trained on laboratory-based motion capture data encounter challenges such as limited training data, depth perception ambiguity, left/right switching and issues with occlusions when applied in real-world environments [

5]. To analyze these issues, we applied motion recognition to various real-life videos using two representative 3D HPE (Human Pose Estimation) methods: MediaPipe Pose (MPP) [

6] and HybrIK [

7]. MPP estimates a total of 33 landmarks of human body joints based on the Blaze Pose Model. Recently, research on analyzing motions in Activities of Daily Living [

8] and activities such as karate using MPP has been gaining momentum [

9]. HybrIK is an inverse kinematics solution that combines the strengths of 3D keypoint estimation and body mesh recovery into a unified framework. It achieves top-ranking performance in the HPE area.

This paper compares performance of the two 3D HPE methods by assessing their strengths and weaknesses with real-world videos. Then, we propose data processing techniques to eliminate and correct anomalies like left/right joint position inversion and false detections in daily life motions. Finally, we obtain joint angle trajectories of a 3D humanoid simulator using an optimization method called uDEAS, which is already proven to be successful with 2D joint coordinates in [

8], taking as input the 3D joint coordinate data corrected by applying the proposed data correction technique. If the accuracy of joint angle-based 3D posture estimation through a monocular camera is acceptable, it can be applied in a wide range of fields such as recognizing hazardous behaviors in daily life, autonomous driving, personalized home care, the metaverse, healthcare, and medical clinical rehabilitation therapy.

Section 2 introduces existing research on monocular image-based 3D posture estimation. In

Section 3, we explain and compare the performances of two representative HPE methods, using videos filmed in real-world environments. Additionally, we detail the proposed outlier detection and correction algorithms and demonstrate their application through example videos. Moreover, the joint angle estimation scheme, which uses an optimization method and a 3D humanoid model, is briefly described.

Section 4 presents experiment result of the proposed HPE based on joint angles, applied to a standing rowing exercise.

Section 5 concludes our work with future possibilities for application.

2. Related Work

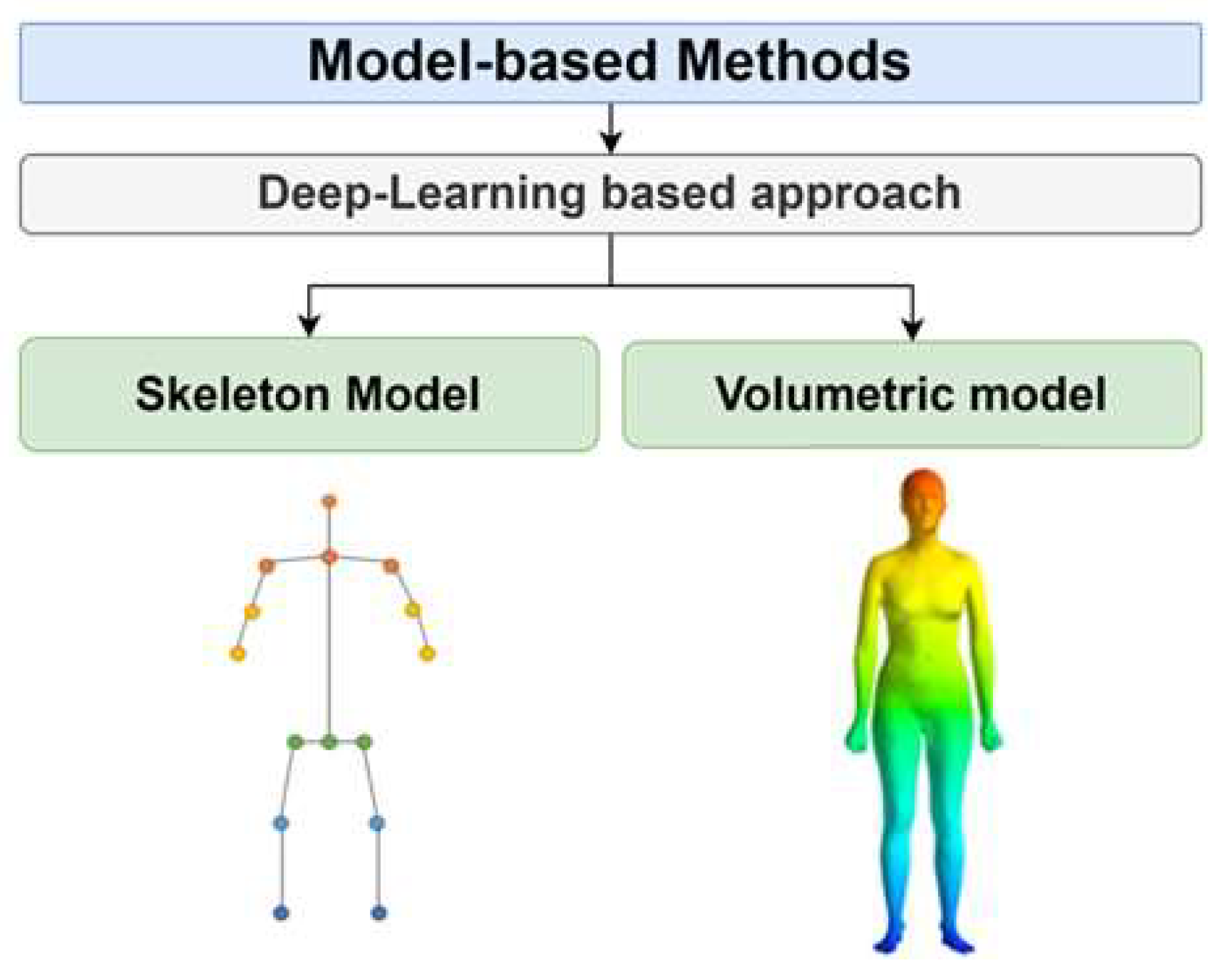

The study of 3D pose estimation is divided into research targeting a single person and multiple people. We focus on the existing algorithms for 3D HPE of a single person. Two models, namely the skeleton model and the volumetric model, are used for single-view single-person 3D HPE using a monocular camera.

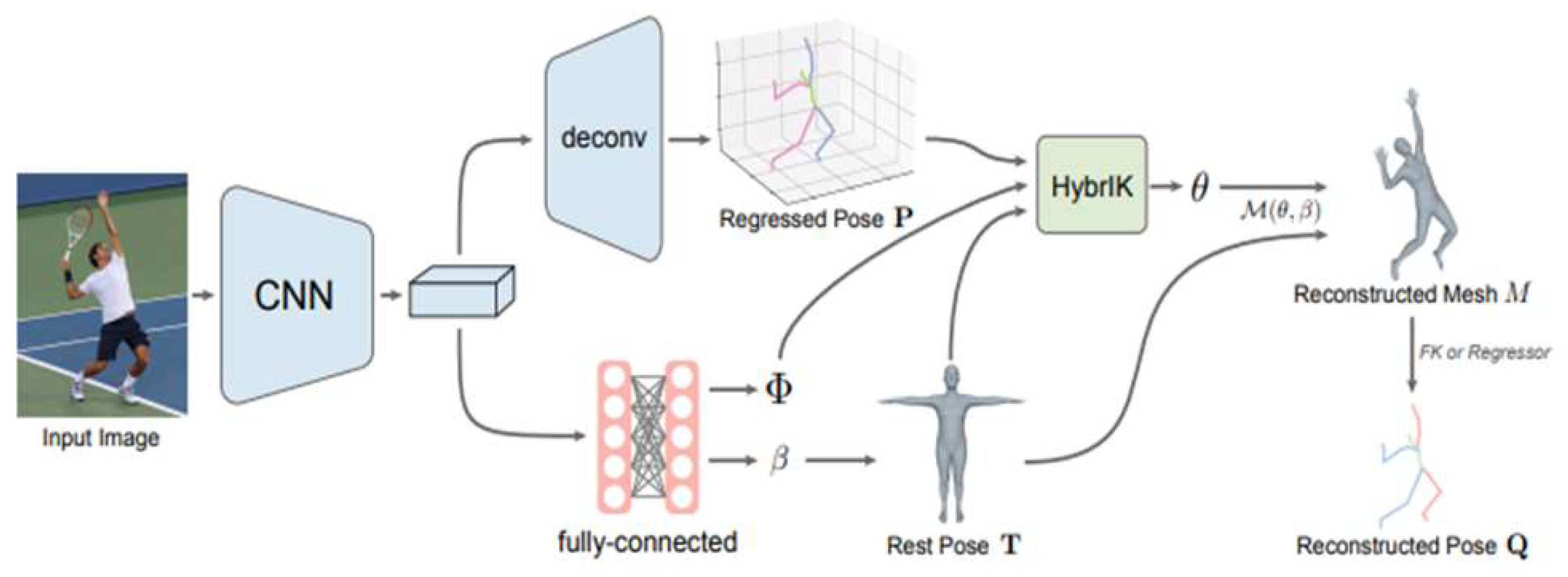

Figure 1 shows the configuration of a model-based deep learning (DL) approach.

2.1. Skeleton Model

The human skeleton model is advantageous as it intuitively describes the structure of the human body with a tree structure linking joints with lines. This model is not only used in 3D pose estimation but also widely in 2D pose estimation due to its simple structure, which requires lower computational cost and time. The model works by detecting key joints in images or videos and estimating their positions in 3D space. Common techniques include Direct Regression, where the joint positions of the human model are directly estimated from the input image, allowing for end-to-end training, and the Heatmap-based method, which predicts approximate joint positions from the image and then uses heatmap probability information for pose estimation [

10]. Recent research often combines these two approaches in a hybrid method for 3D pose estimation. However, the skeleton model has limitations, such as predicting body structures in unrealistic or asymmetric poses. Additionally, it struggles to represent external body shape and kinematic details like joint bending (swing) and rotation (twist).

2.2. Volumetric Model

The Human Mesh Recovery (HMR) technique, which represents the human body in 3D mesh form from a single image, has gained attention in recent developments. This method involves reconstructing the human body from an input image or video into a 3D volumetric mesh model. A notable 3D mesh model used in this context is the SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear model) [

11]. DL algorithms based on the 3D mesh model demonstrate high accuracy in pose estimation by considering the body shape and rotation matrices, thus accounting for twisting movements. However, these algorithms require high computational costs and processing time. Additionally, due to the limitation of 3D joint coordinate datasets used for DL training, they often exhibit lower accuracy for untrained poses. Training with datasets containing 3D information typically involves data captured in laboratory settings using motion capture equipment. This can lead to a higher likelihood of false detections in various clothing and real-world environments. Notable previous studies based on HMR include Pose2Pose [

12], HybrIK [

7], and FrankMoCap [

13]. These research efforts reflect the ongoing challenges and developments in the field of 3D human pose estimation.

3. Methodology

In this study, we implement and conduct a comparative analysis between MPP, a prominent algorithm based on the human skeleton model, and HybrIK, an algorithm based on the volumetric model. The implementation environments for these methods are detailed in

Table 1.

3.1. Pose Estimation Methods

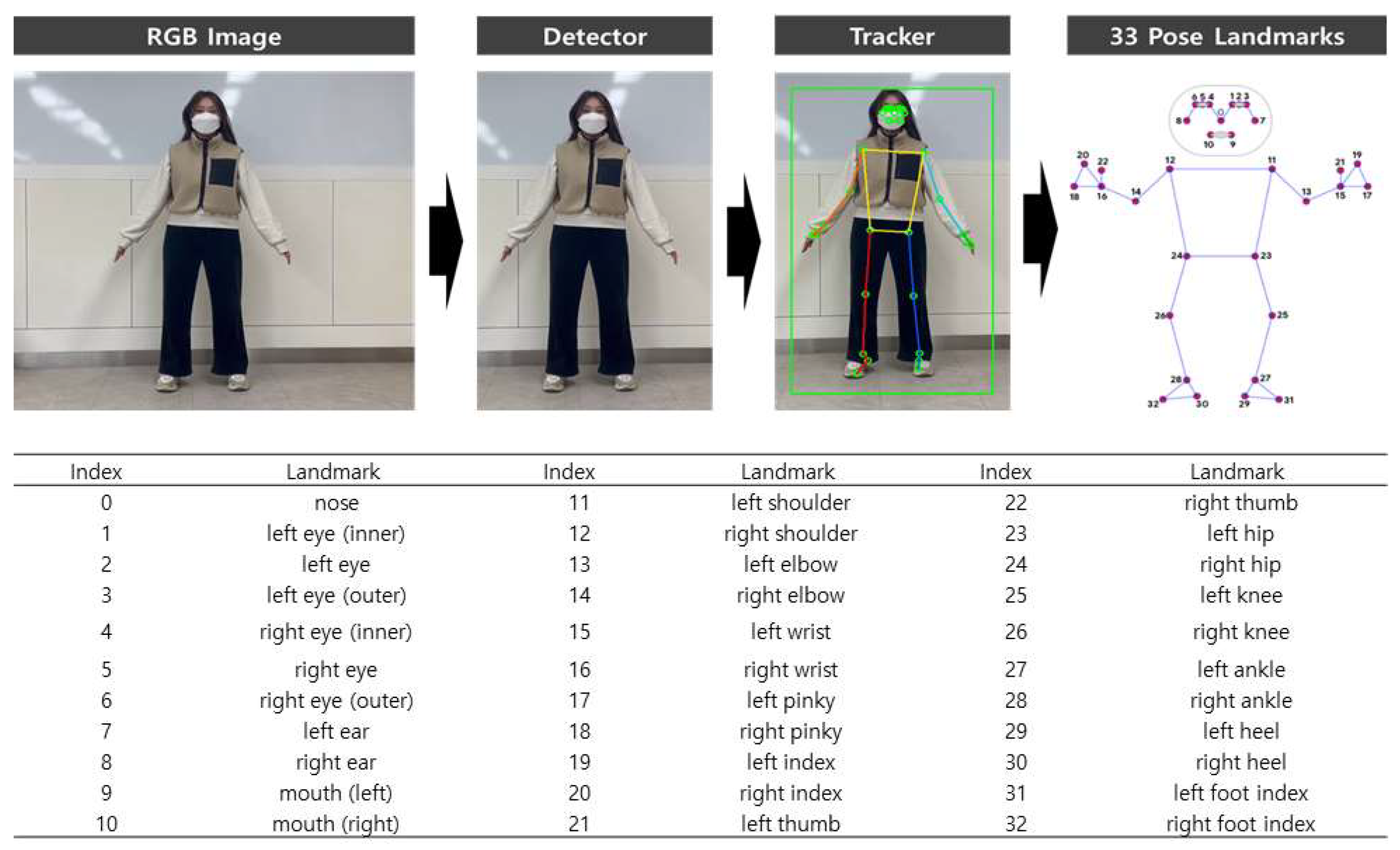

3.1.1. MediaPipe Pose

MPP is an open-source framework provided by Google, delivering estimation results for a total of 33 landmarks. MPP is based on the Blaze Pose Model [

14] and offers three different models depending on their size: Lite (3MB size), Full (6MB size), and Heavy (26MB size). The training dataset typically includes 60K images of individuals or small groups in common poses and 25K images of an individual performing fitness exercises.

In this paper, we use the widely adopted MPP Full model for real-time evaluation. MPP extracts a total of 33 landmarks as illustrated in

Figure 2. In the first stage, a pose detector identifies the region of interest (ROI) within an RGB image, using facial landmarks to determine the presence of a person. Subsequently, a pose tracker infers the 33 landmarks within the ROI. This approach enables accurate and efficient pose estimation in various contexts.

3.1.2. HybrIK

HybrIK is an Inverse Kinematics solution that considers the volume of the human body in 3D. Previous estimation methods based on HMR reconstruct a 3D Mesh through the estimation of multiple parameters. However, learning abstract parameters can lead to lower model performance. To address this, HybrIK, as depicted in

Figure 3, employs an inverse kinematics approach to bridge the gap between Mesh estimation and 3D skeletal coordinate estimation.

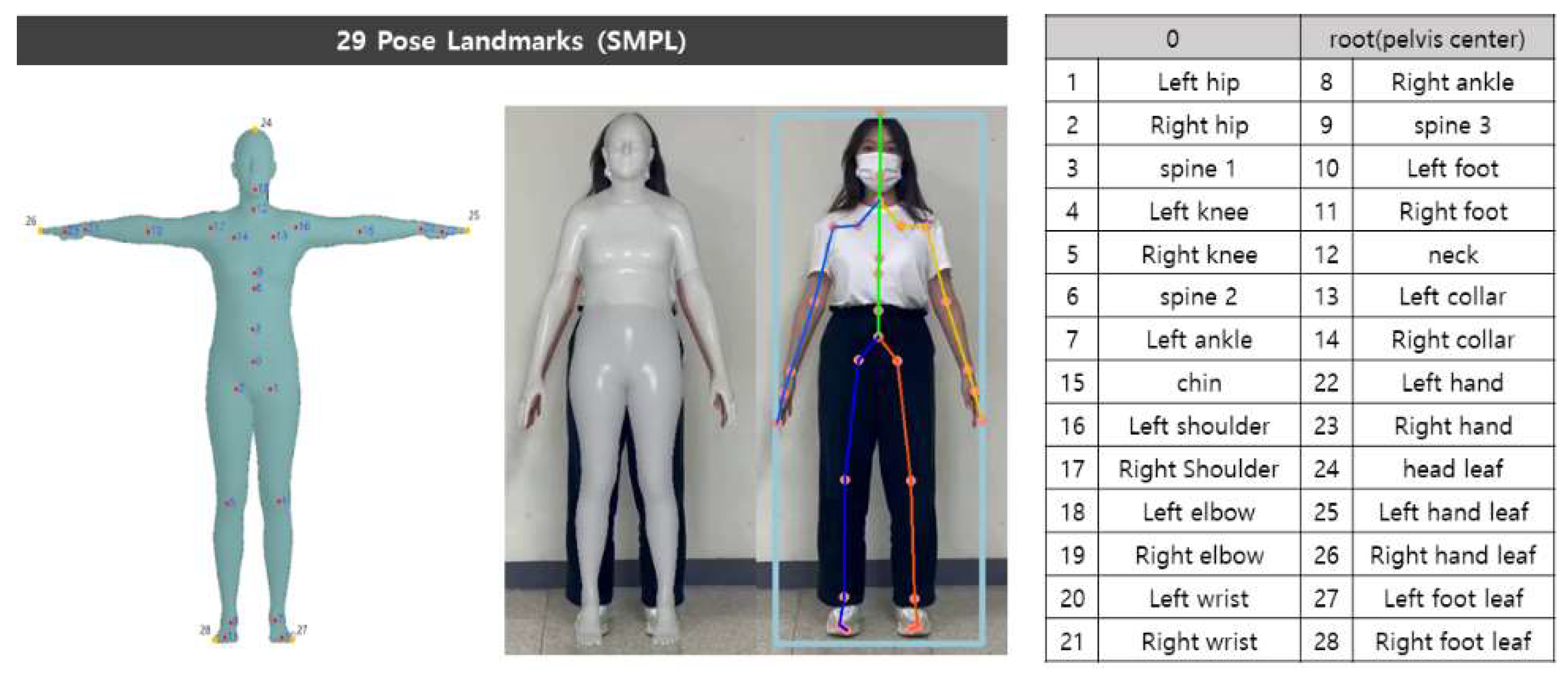

HybrIK supports two models: SMPL [

11] and SMPL-X [

15]. In this research, focusing on the body joints of the human figure, we usedd the SMPL model to extract a total of 29 landmarks.

Figure 4 illustrates the definitions the 29 landmarks of HybrIK skeletal model.

3.2. Performance Comparison in Real-World Environments

To compare the accuracy of DL models in real-world environments, we conducted a comparison using video footage. To this end, RGB videos were used as input for the DL models, shot at a resolution of 1280x720 and 30 FPS. The selected input videos included complex postures, scenes with objects resembling human figures, footage shot from a distance, and videos with various lighting conditions.

Figure 5 depicts the first video, featuring a complex yoga pose with intertwined human joints. In

Figure 5(a), the skeleton model estimated by MPP is overlaid, with the right-side joints indicated in shades of red and the left-side joints in shades of blue. The area recognizing the person is marked with a green bounding box. Even in a single image, it can be observed that the model accurately detects the left leg bending upwards. This demonstrates the effectiveness of MPP in complex pose recognition.

Figure 5(b) shows the estimation results of HybrIK where the estimated SMPL model overlaid on the image. The algorithm accurately estimates leg positions within a certain angle range. However, as the complexity of the pose increases, the accuracy of the estimation decreases. Additionally, it is observed that the estimation accuracy for extremities, such as feet, is lower. This highlights the challenges in accurately estimating complex poses and the limitations in detecting extremity joints with HybrIK.

Figure 5.

Estimation Results of a yoga pose: (a) MPP; (b) HybrIK.

Figure 5.

Estimation Results of a yoga pose: (a) MPP; (b) HybrIK.

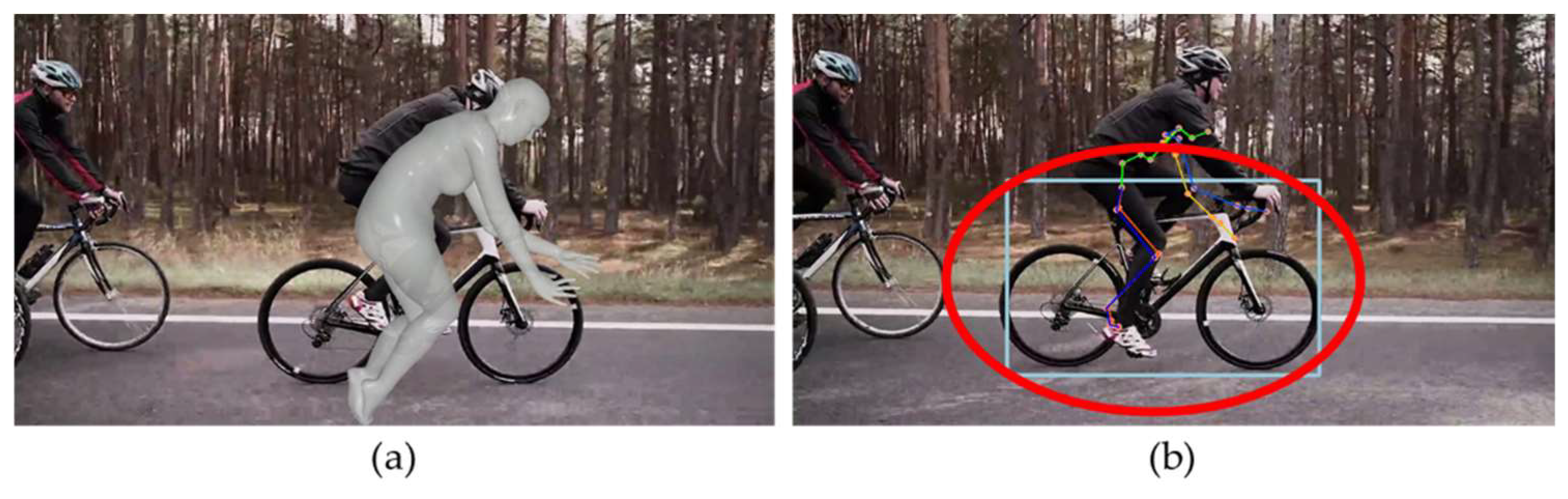

Next, we compare the estimation results for a person riding a bicycle.

Figure 6 shows an image of the person cycling shot from the side and includes occlusion areas where some joints are obscured, and external objects are present. In

Figure 6(a), MPP accurately identifies the joints of the person without mistaking the bicycle as a human figure. However, it occasionally produces inaccurate estimations for the occluded areas as shown in

Figure 6(b).

Figure 7 displays the estimation results of HybrIK for the same image. HybrIK shows inaccurate estimations for all frames.

Figure 7(a) shows that estimated SMPL model deviates much from the target person, which is due to erroneous person recognition area of HybrIK as shown in

Figure 7(b). It can be observed that HybrIK mistakenly identifies the bicycle as a person and attempts to estimate its 3D posture. This highlights a limitation of HybrIK in differentiating between human figures and inanimate objects in complex scenes.

The third video is shot from a distance, featuring a person in a pitching stance. Due to the camera angle, some joints of the person are in self-occlusion areas.

Figure 8(a) and

Figure 8(b) present the estimation results of MPP and HybrIK, respectively. Both algorithms demonstrate high accuracy in their estimations in this scenario. This indicates their effectiveness in dealing with challenges such as distance and partial occlusions, particularly in capturing and analyzing the posture of a person engaged in a specific activity like pitching.

The final case involves a video with varying light intensity due to shadows. In real-world environments, shadows occur due to sunlight or artificial lighting, and people often wear clothing with various patterns. This can lead to frequent and abrupt changes in the colors of RGB images.

Figure 9 presents the estimation results of MPP, which demonstrates the capability to estimate poses even from the back of a person. However, there are frequent occurrences of coordinate inversions on the left and right sides due to changes in lighting conditions.

Figure 10 displays the estimation results of HybrIK. Similar to MPP, HybrIK accurately estimates the posture of a person from the back. Furthermore, it shows more robustness in handling changes in light intensity compared to MPP, providing more stable estimation results under varying lighting conditions. This suggests that HybrIK has a certain level of resilience to changes in environmental lighting, which is crucial for practical applications in diverse real-world scenarios

To summarize the findings so far in real-world environments, MPP is capable of real-time analysis and demonstrates high accuracy in person recognition through its method of finding regions of interest based on facial landmarks. In addition, including individual fitness data in the dataset results in high estimation performance for complex poses. However, MPP is sensitive to changes in light intensity and clothing patterns in RGB images and exhibits some inaccuracies in depth estimation.

On the other hand, HybrIK, based on the SMPL model, shows relatively better performance in depth estimation. However, when applied to real-world settings, it demonstrates reduced accuracy in person recognition and in estimating complex joint positions. Lastly, it is important to note that the open-source versions of both DL models don’t provide 3D joint angles. For moving beyond person recognition from 2D images to recognizing and predicting 3D human actions, accurate estimation based on joint angles is essential. Therefore, this study aims to further research the removal and correction of anomalies in DL models and a method that finds the angles of each joint with reference to a 3D humanoid model using an optimization method to improve HPE accuracy and applicability.

3.3. Improving Pose Recognition Performance

3.3.1. Improving Human Recognition Accuracy

To enhance the accuracy of DL models, improving human recognition performance is a prerequisite. In real-world environments, video data often contains multiple people and objects resembling human figures. Thus, for 3D HPE technology focusing on a single person to be effectively utilized in real environments, it is crucial to continuously recognize an individual in the video.

The comparative study revealed instances where non-human objects were mistakenly recognized as humans. Originally, HybrIK utilized the fasterrcnn_resnet50_fpn algorithm [

16] provided by PyTorch for rapid object detection in images, with the detected region of interest then input into the HybrIK model. However, this method only estimates the object with the highest recognition score and largest recognized area in the image, not specifically focusing on human figures. As a result, non-human objects like bicycles could be misidentified as humans, leading to inaccurate estimations by the HybrIK model. In this paper, to improve recognition accuracy, the fasterrcnn_resnet50_fpn trained on the COCO dataset was applied to HybrIK. We used 2017 version of COCO dataset [

17]. Excluding the background, 11 out of 91 categories in the dataset are omitted, and classification is conducted on a total of 80 objects. This enhancement aims to refine the object detection process, focusing specifically on human figures and reducing the likelihood of misidentifying non-human objects as people.

Firstly, the target person for analysis is identified in the first frame. The object recognition algorithm predicts significantly more bounding boxes (BB) than there are actual objects. Therefore, to adopt the most accurate BB for human recognition, the following steps are taken to eliminate unnecessary BBs:

Remove all BBs whose confidence scores are below a certain threshold;

Eliminate all detected BBs that are not identified as humans.

From the remaining BBs, keep only the one with the largest area and remove the rest.

If, in the first frame, there are no BBs with confidence scores above the threshold, the threshold is adjusted and the process is repeated. This approach ensures that the most probable human figure is selected for analysis, enhancing the accuracy of subsequent pose estimation.

Then, once the subject for analysis has been determined, the information from the previous frame is used to continuously recognize the target. The process is as follows:

In the current frame, remove all BBs that are not identified as humans;

Calculate the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the BB recognized in the previous frame and the BBs in the current frame. IoU is a common measure used in object detection to assess the similarity between two sets. It is calculated as the ratio of the intersection area (

) of the recognized regions in the current (

) and previous (

) frames to their union area, as expressed below:

Finally, adopt the BB that has the highest sum of confidence score and IoU score.

This approach ensures continuous and accurate tracking of the target across frames, leveraging the similarity of detected regions between consecutive frames and the reliability of the detection.

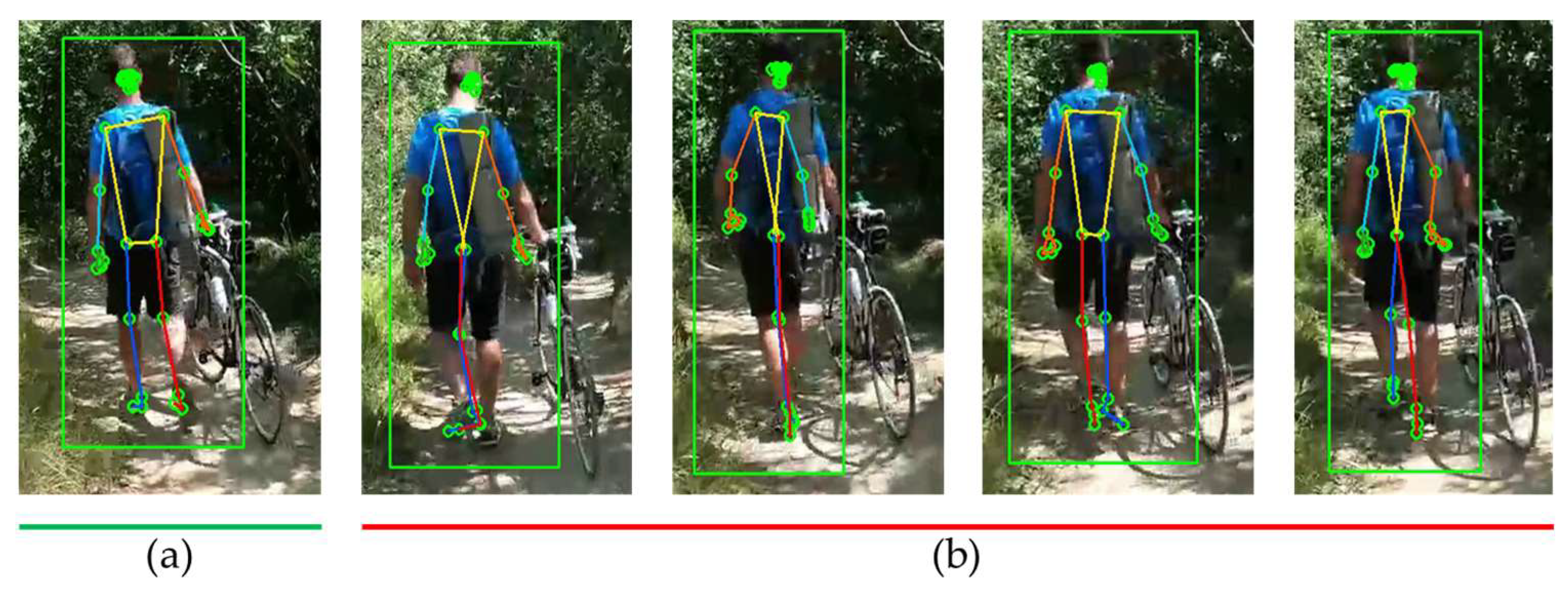

Figure 11 illustrates the results of applying the proposed human recognition algorithm to the HybrIK model, which shows an improvement in the accuracy of human pose estimation compared to previous results.

3.3.2. Detection of Outliers

In the context of real-world environments, issues commonly encountered in the recognized human model can be categorized into jitter, switching, and miss-detection [

5]. Therefore, the process of detecting outliers and correcting them is essential. In this study, a 3D joint coordinate correction step is conducted to address the shortcomings typically associated with DL-based human pose estimation algorithms and improve accuracy.

When capturing movements using a single monocular camera, occlusion areas occur due to the fixed field of view. These occlusion areas can be categorized as self-occlusion, where some joints are obscured by one's own body, and external occlusion, where joints are obscured by external objects. Capturing the same pose, but with different camera positions, results in different obscured joints. In these occlusion areas, low confidence estimates from the DL model are often generated.

Another challenging factor in pose estimation from RGB images is the variation in lighting intensity. Irregular changes in lighting can lead to phenomena such as left/right inversion or sudden coordinate distortion. In this research, inaccurate estimations in occlusion areas commonly occurring in DL models and the phenomenon of left/right switching are defined as outliers, and detection and correction are performed. Miss-detection in occlusion areas mostly involves the inclusion of end joints.

Symmetrical inversion of the human body shape occurs when there is a switch between left and right, often around the center points of the pelvis or the joints at the center of the shoulders and pelvis.

Figure 12 illustrates the 3D coordinate trajectory of the right shoulder in the case of switching, with the segments affected by outliers marked in red. Since this occurs across the entire body, all joints need to be adjusted in such cases.

In this study, outliers are detected through changes in the lengths of 10 major links, which include the shoulder, pelvis, thigh, shin, upper arm, and lower arm. Link length is calculated as the Euclidean distance between two joints in a 3D pixel coordinate system. It is important to note that the link lengths on the pixel frame are measured differently depending on the distance from the camera. Therefore, to standardize the link measurements, we normalize them using the average height information from the Size Korea [

18], which states the average height for women as 160cm and for men as 175cm.

Figure 13 illustrates the changes in the lengths of the 10 links for each frame during a walking motion shown in

Figure 12. Joint lengths vary linearly when a person performs dynamic motions. The proposed algorithm differentiates the length changes per frame and detects non-linear segments.

Figure 14 presents the results of differentiating lengths of the 10 links shown in

Figure 13, with the red areas indicating cases of left/right inversion, and the blue areas representing instances of partial joint mis-detection.

3.3.3. Outlier Correction

In this study, we propose an outlier detection and correction method, whose structure is shown in

Figure 15, using the lengths of human body links.

Figure 16 represents the process of outlier correction for the 3D coordinates of the right shoulder. First, we analyze the variations in the lengths of major links to observe changes.

Figure 16(a) examines the length variations of the right shoulder to detect outliers. The segments where outliers are detected are marked in red on the graph, and the solid lines in

Figure 16(b) and 16(c) represent the corrected data after outlier removal, while the red dashed line represent the original data. In

Figure 16(b), the removed segments are interpolated using the mean interpolation method, where the average values of frames before and after the outlier segments are used for interpolation. In

Figure 16(c), a median filter is applied to smooth the corrected trajectories. Applying the filter helps minimize frame-by-frame errors in the DL model.

3.3.4.3. D Pose Estimation Based on Humanoid Model

To estimate joint angle trajectories of human motion, a 3D humanoid robot model and an optimization algorithm are employed using joint coordinate trajectories corrected by the data processing algorithm described so far. The univariate Dynamic Encoding Algorithm for Searches (uDEAS) is chosen as the optimization method due to its high speed and accuracy, which was proven in the previous work [

8].

uDEAS is a global optimization method that combines local and global search schemes by representing real numbers into binary matrices. Among local search, a session composed of single bisectional search (BSS) and multiple unidirectional search (UDS) is executed for each row. BSS adds a new bit at the right most position, and UDS increases or decreases each binary row (the encoded representation for each variable) depending on the BSS result. As to the global optimization scheme, uDEAS restarts the local search procedure from random binary matrices. Among the local minima found so far, the one with the minimum cost function is selected as the global minimum.

In the present work, during the optimization process a set of candidate joint angle variables is fed into the humanoid model, and the model simulates a 3D pose. The objective is to seek for joint angle values that minimize the Euclidean distance between the coordinates of each simulated joint and the corresponding measured joints.

Humanoid model is more elaborated to have a total of 26 DoF by adding transversal shoulder joints and a coronal neck joint as shown in

Figure 17, compared with the recent model in [

8]. In the figure, the variables shaded in orange represent the 17 joint angles used for HPE, and three variables,

,

, and

, are body angle values related with the relative camera view angle, where

,

, and

denote joint angles rotating on the sagittal, coronal, and transversal planes, resepectively. For estimation of arbitrary poses at any distance from camera, a size factor,

, is also necessary, which is multiplied to

each link length. Thus, as the camera moves away from human,

decreases, and vice versa. Therefore, a complete optimization vector for pose estimation consist of 21 variables as follows:

The cost function to be minimized by uDEAS is designed to minimize Mean Per Joint Position Error (MPJPE) for the 3D estimated model and the fitted one, which is calculated as mean Euclidean distance between the 3D joint coordinates estimated by MPP or HybrIK,

, and those fitted by the 3D humanoid model in

Figure 17,

:

When the two models overlap exactly, this value is reduced to zero.

4. Experiment

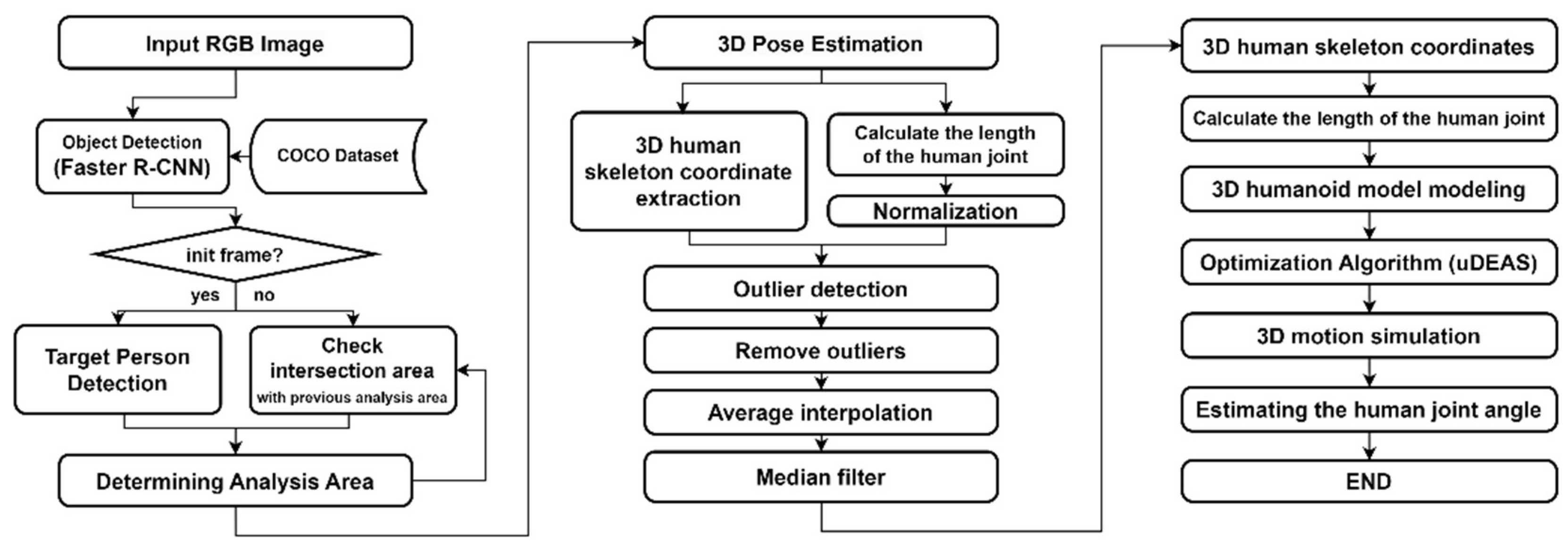

In this study, we aim to improve the accuracy of human joint angle estimation through the aforementioned data processing steps and the application of a humanoid model and optimization algorithms to estimate accurate joint angles. The proposed algorithm in this study consists of three major steps, as outlined in

Figure 18.

Firstly, our algorithm detects the analysis region in the image data captured by a monocular camera. This involves detecting the person of interest in the RGB image using bounding boxes, and with the help of information from analysis region of the previous frame, we can stably continue tracking the same person. Next, 3D human joint coordinates are extracted using MPP based on the skeleton model or HybrIK based on the volumetric model. In the following step, outliers are corrected, which may occur in the DL model. Outliers refer to jitter in the 3D human skeletal coordinates caused by errors in the DL model, mis-recognition in occluded areas, left/right inversion due to changes in lighting and clothing patterns. These are addressed through the detection of non-linear changes in joint length in the human body. Finally, the 3D human skeletal coordinates processed through the correction procedure are reconstructed into a humanoid model with the optimization method, uDEAS, enabling the estimation of joint angles.

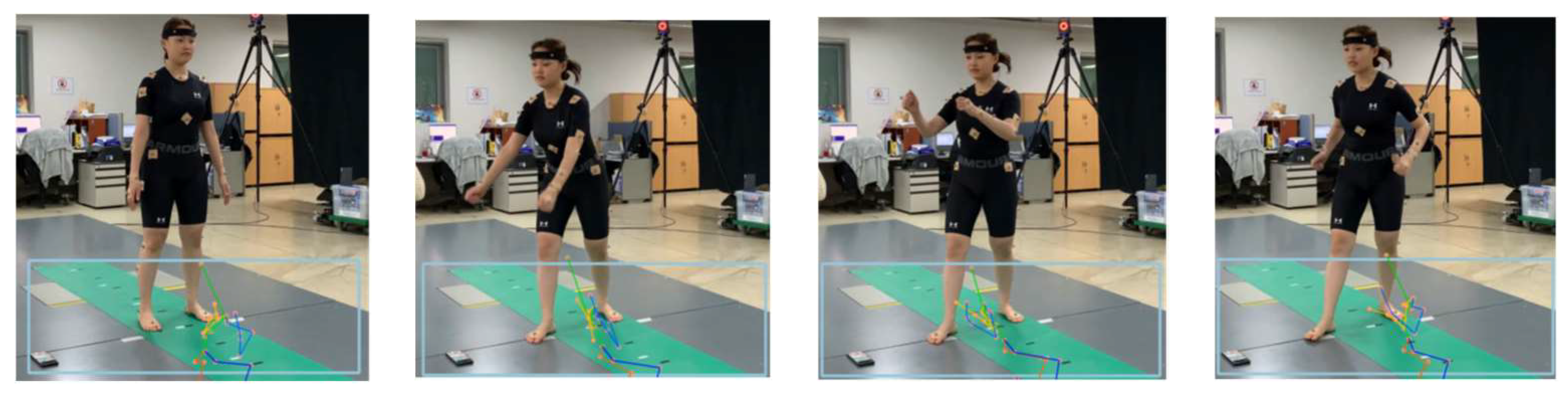

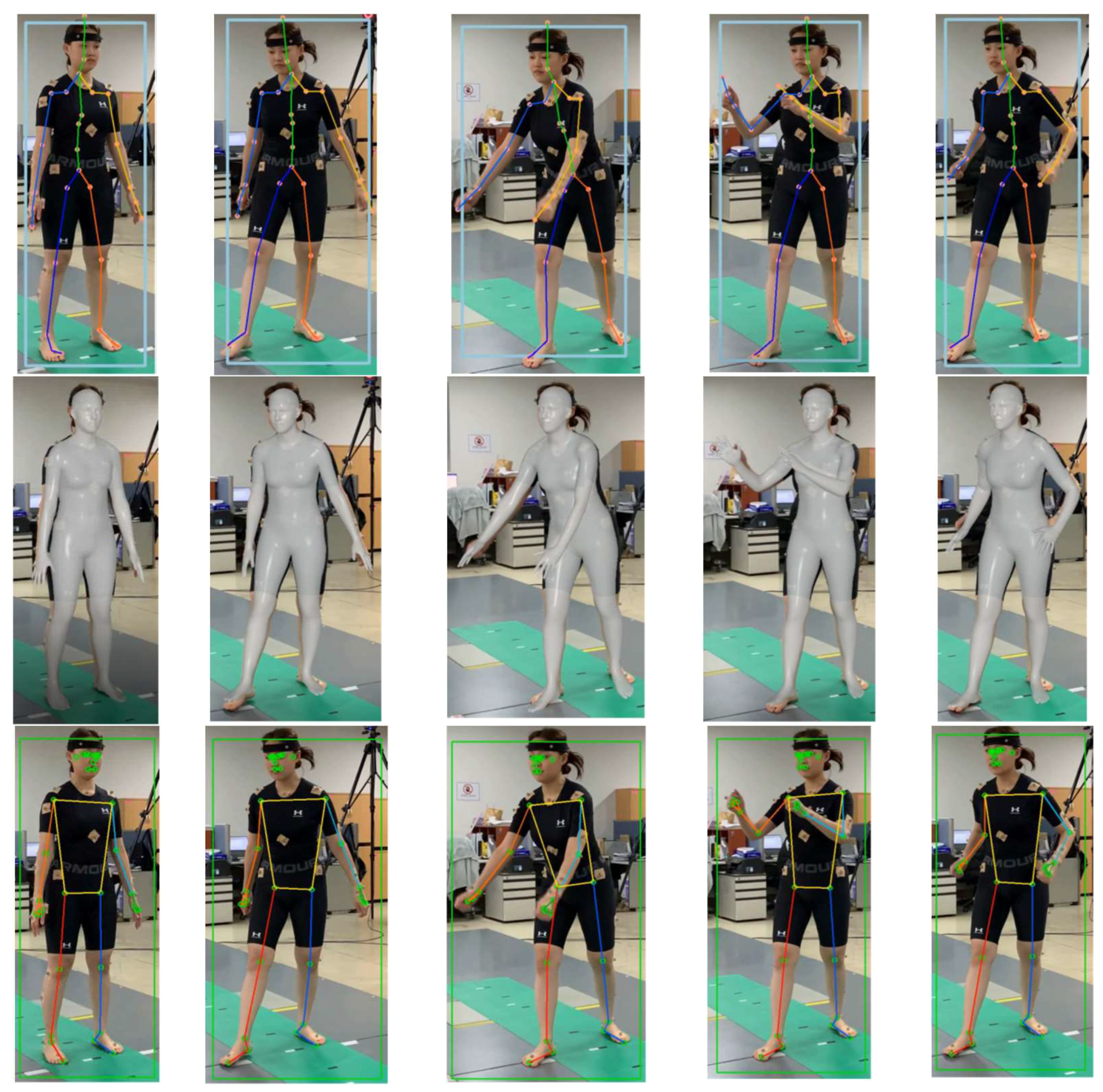

Figure 19 captures the process of analyzing a video shot from the side of a subject doing free gymnastics similar to rowing in a motion capture lab equipped with a Vicon equipment [

20]. In the video, the light-blue boxes represent bounding boxes that detect the area of a person using the HybrIK's original code, mistakenly identifying the area from below the knees to the floor as the presence of a person. As a result, there is a significant error in HPE results. It is speculated that images taken from the side were insufficient in HybrIK's training data, because the area with the person was well detected in a video shot from the front for the same motion.

Figure 20 shows the results of pose recognition using HybrIK and MPP after undergoing the proposed filtering algorithm on RGB images of the same motion. The first and second rows of images in

Figure 20 represent the results of pose recognition using HybrIK, estimated with a skeletal model and SMPL, respectively. The third row in

Figure 20 shows

Figure 19.

Images captured from a standing rowing exercise video and bounding boxes generated by HybrIK for HPE process (light blue).

Figure 19.

Images captured from a standing rowing exercise video and bounding boxes generated by HybrIK for HPE process (light blue).

the results of pose recognition using MPP. As seen in the figure, both methods accurately recognize the human pose in videos shot from the side owing to preprocessing

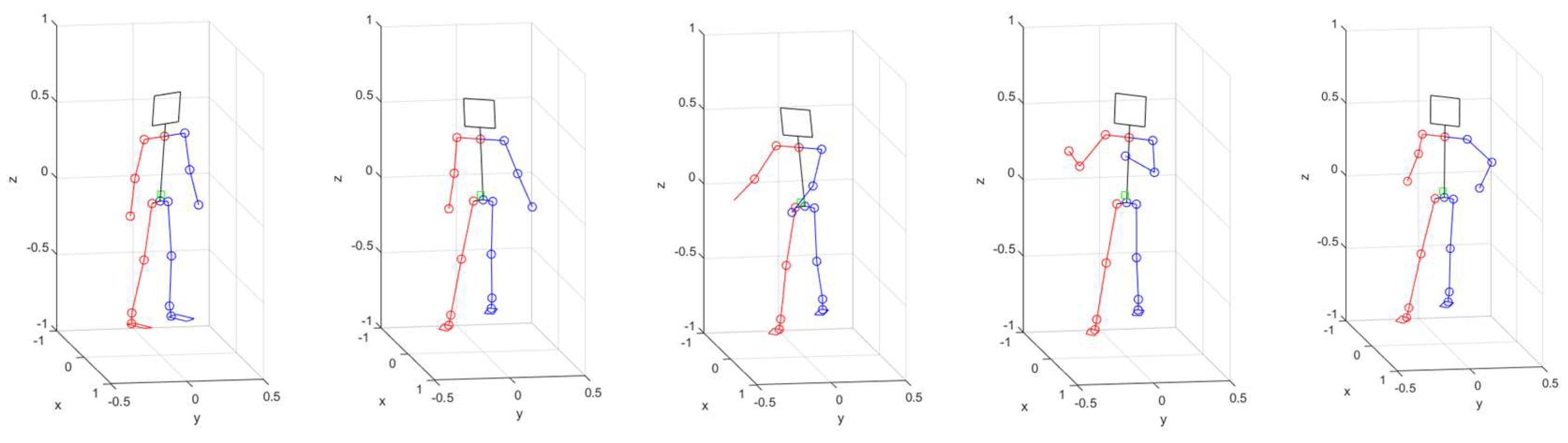

Figure 21 shows the body reconstruction results by estimating each joint angle of the humanoid model shown in

Figure 17 with uDEAS using 3D joint coordinate values recognized by HybrIK. It looks almost identical to each pose in

Figure 20.

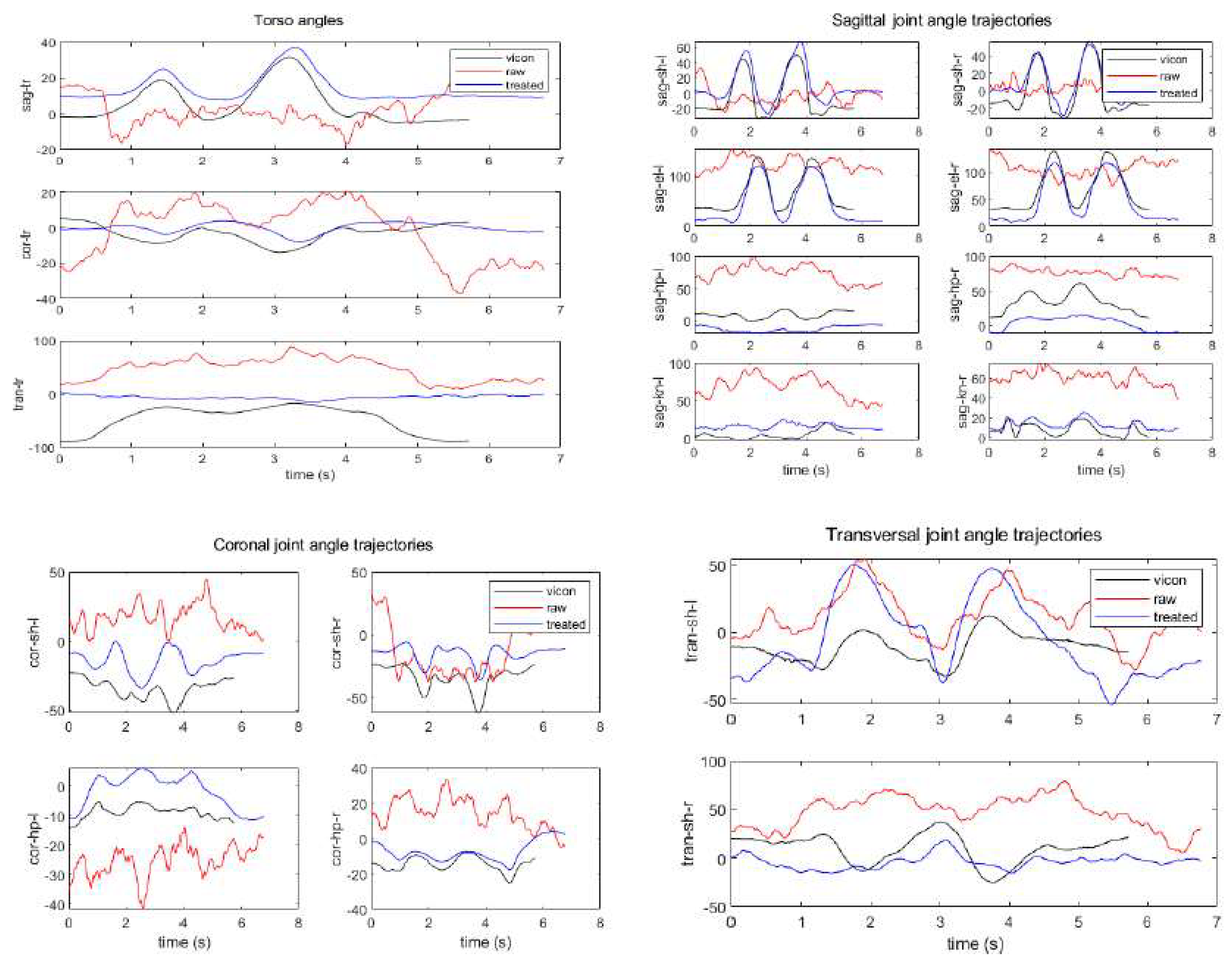

Figure 22 shows the joint angle profiles calculated using uDEAS from the joint coordinate values estimated by the original HybrIK during the standing-rowing action, displayed in red. It also presents, in blue, the joint angle profiles estimated in the same manner from the joint coordinate values obtained by applying the data correction technique proposed in this paper to HybrIK. Furthermore, the black graphs in the figures represent the joint angle profiles calculated in the Vicon laboratory. The Vicon angles are displayed for reference as they differ somewhat in landmark and joint angle definitions from HybrIK.

Figure 21.

Body reconstruction results attained by calculating each joint angle of the humanoid model with uDEAS using 3D joint coordinate values recognized by HybrIK.

Figure 21.

Body reconstruction results attained by calculating each joint angle of the humanoid model with uDEAS using 3D joint coordinate values recognized by HybrIK.

Overall, it can be seen that the blue and black graphs exhibit similar variation patterns, except for certain joints. However, the red graph shows a complete difference from the blue graph, indicating that the original HybrIK incorrectly recognizes the human presence area, as shown in

Figure 19, resulting in highly inaccurate joint angle estimates from its model. For reference, the cost function of uDEAS for the red joint angle graph (original) is on average 0.0147, while for the blue joint angle graph (processed), it is only 0.0046, which is about 31% of the former cost.

In

Figure 22, the processed HybrIK and its joint angle estimation results for the joint angle profiles of the waist's sagittal/coronal joint angle, the left/right sagittal joint angle of the shoulder/elbow, the sagittal right knee joint, and the coronal right hip joint show shapes that are quite similar to the results from Vicon. Even in other joints, one can observe similar patterns of angle profiles, albeit with some differences in offsets.

5. Conclusions

In this study, two representative algorithms for 3D HPE, MPP and HybrIK, are applied to videos in the wild, revealing limitations of deep learning models such as mis-detections in occluded areas and left/right inversion due to changes in lighting. To resolve these problems, corrective methods are proposed by using link length derivative information, mean interpolation, and median filter. Additionally, the study applied optimization algorithms and humanoid models to estimate human joint angles and compared these with results measured in Vicon. The proposed pose correction and joint angle estimation approach produced better and acceptable HPE result.

MPP was found to be fast in computation speed and highly accurate in human recognition through facial landmarks. However, the inaccuracy in depth perception needs improvement. Particularly, standing postures and postures shot from the back showed low accuracy in depth, while the accuracy of estimation for postures with bent joints or shot from the side was relatively high. It also demonstrated high estimation accuracy for complex postures like yoga poses. The HybrIK model, based on the SMPL model, showed high accuracy in depth estimation. However, it exhibited low accuracy in postures with complex joint entanglements or severe bending.

Although this study corrected anomalies through simple correction methods, future research involving anomaly correction through behavior analysis will enhance its applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kim, J.-W. and Choi, J.-Y.; software, Choi, J.-Y., Ha, E., and Kim, J.-W.; validation, Kim, J.-W.; formal analysis, Choi, J.-Y.; investigation, Choi, J.-Y.; data curation, Choi, J.-Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Choi, J.-Y.; writing—review and editing, Kim, J.-W.; project administration and funding acquisition, Kim, J.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) with a grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2021R1A4A1022059).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 3D Motion Capture Market. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/3d-motion-capture-market#:~:text=In%202023%2C%20the%20global%203D,up%20of%203D%20motion%20capture (accessed on 10 Dec. 2023).

- Yehya, N.A. Researchers analyze walking patterns using 3D technology in community settings. Available online: https://health.ucdavis.edu/news/headlines/researchers-analyze-walking-patterns-using-3d-technology-in-community-settings-/2023/01 (accessed on 15 Nov. 2023).

- Seel, T.; Raisch, J.; Schauer, T. IMU-based joint angle measurement for gait analysis. Sensors 2014, 14, 6891–6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vithanage, S. S.; Ratnadiwakara, M. S.; Sandaruwan, D.; Arunathileka, S.; Weerasinghe, M.; Ranasinghe, C. Identifying muscle strength imbalances in athletes using motion analysis incorporated with sensory inputs. IJACSA 2020, 11(4), 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 5. Ronchi, M.R.; Perona, P. Benchmarking and error diagnosis in multi-instance pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, Venice, Italy, 22-29 Oct. 2017. pp. 369-378.

- MediaPipe Pose. Available online: https://github.com/google/mediapipe/blob/master/docs/solutions/pose.md (accessed on 25 Nov. 2023).

- 7. Li, J.; Xu, C.; Chen, Z.; Bian, S; Yang, L.; Lu, C. Hybrik: A hybrid a nalytical-neural inverse kinematics solution for 3d human pose and shape estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, virtual, 19-25 June 2021. pp. 3383-3393.

- Kim, J.-W.; Choi, J.-Y.; Ha, E.-J.; Choi, J.-H. Human pose estimation using MediaPipe Pose and optimization method based on a humanoid model. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkess, G.; Elmoushy, S.; Atia, A. Karate first Kata performance analysis and evaluation with computer vision and machine learning. In Proceedings of the International Mobile, Intelligent, and Ubiquitous Computing Conference, Cairo, Egypt, 27-28 Sept. 2023. pp. 1-6.

- Zheng, C.; Wu, W.; Chen, C.; Yang, T.; Zhu, S.; Shen, J.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Shah, M. Deep learning-based human pose estimation: a survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 56(11), pp 1-37.

- Loper, M.; Mahmood, N.; Romero, J.; Pons-Moll, G.; Black, M. J. SMPL: a skinned multi-person linear model. ACM Trans. Graph 2015, 34(248), pp. 1-16.

- Moon, G.; Lee, K. M. Pose2pose: 3d positional pose-guided 3d rotational pose prediction for expressive 3d human pose and mesh estimation. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2011.11534, 1(2).

- FrankMocap: A Strong and Easy-to-use Single View 3D Hand+Body Pose Estimator. Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/frankmocap (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- BlazePose: A 3D Pose Estimation Model. Available online: https://medium.com/axinc-ai/blazepose-a-3d-pose-estimation-model-d8689d06b7c4 (accessed on 20 Nov. 2023).

- SMPL eXpressive. Available online: https://smpl-x.is.tue.mpg.de/ (accessed on 28 Sept. 2023).

- FASTERRCNN_RESNET50_FPN. Available online: https://pytorch.org/vision/main/models/generated/torchvision.models.detection.fasterrcnn_resnet50_fpn.html (accessed on 25 Sept. 2023).

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN, In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 13 Dec. 2015, pp. 1440-1448.

- Size Korea. Available online: https://sizekorea.kr/ (accessed on 10 Dec. 2023).

- Kim, J.-W.; Kim, T.; Park, Y.; Kim, S.W. On load motor parameter identification using univariate dynamic encoding algorithm for searches (uDEAS). IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2008, 23, 804–813. [Google Scholar]

- Vicon. Available online: https://www.vicon.com/ (accessed on 2 Jan. 2024).

Figure 1.

Configuration of model-based deep learning approaches for HPE.

Figure 1.

Configuration of model-based deep learning approaches for HPE.

Figure 2.

33 Landmarks and Estimation Process of MPP.

Figure 2.

33 Landmarks and Estimation Process of MPP.

Figure 3.

The Algorithmic Structure of HybrIK [

7].

Figure 3.

The Algorithmic Structure of HybrIK [

7].

Figure 4.

29 landmarks of HybrIK.

Figure 4.

29 landmarks of HybrIK.

Figure 6.

Estimation Results of MPP for videos including objects: (a) accurate estimation; (b) inaccurate estimation of occlusion area.

Figure 6.

Estimation Results of MPP for videos including objects: (a) accurate estimation; (b) inaccurate estimation of occlusion area.

Figure 7.

Estimation Results of HybrIK for videos including objects: (a) SMPL; (b) 29 Pose Landmarks.

Figure 7.

Estimation Results of HybrIK for videos including objects: (a) SMPL; (b) 29 Pose Landmarks.

Figure 8.

Estimation Results of MPP and HybrIK for Long-Distance Videos: (a) MPP; (b) HybrIK.

Figure 8.

Estimation Results of MPP and HybrIK for Long-Distance Videos: (a) MPP; (b) HybrIK.

Figure 9.

Estimation results of MPP for videos with changing light intensity: (a) accurate estimation; (b) inaccurate estimation.

Figure 9.

Estimation results of MPP for videos with changing light intensity: (a) accurate estimation; (b) inaccurate estimation.

Figure 10.

Estimation results of HybrIK for videos with changing light intensity: (a) accurate estimation; (b) inaccurate estimation.

Figure 10.

Estimation results of HybrIK for videos with changing light intensity: (a) accurate estimation; (b) inaccurate estimation.

Figure 11.

Estimation comparison of recognition results in HybrIK with proposed human recognition algorithms: (a) Before processing; (b) After processing.

Figure 11.

Estimation comparison of recognition results in HybrIK with proposed human recognition algorithms: (a) Before processing; (b) After processing.

Figure 12.

3D coordinate trajectories of the right shoulder with outliers detected (MPP).

Figure 12.

3D coordinate trajectories of the right shoulder with outliers detected (MPP).

Figure 13.

Changes in the lengths of major links.

Figure 13.

Changes in the lengths of major links.

Figure 14.

Differentiation results of the lengths of major links.

Figure 14.

Differentiation results of the lengths of major links.

Figure 15.

Structure of the proposed outlier detection and correction algorithm.

Figure 15.

Structure of the proposed outlier detection and correction algorithm.

Figure 16.

Outlier correction results for the right shoulder joint positions: (a) removing outliers; (b) average interpolation; (c) median filter.

Figure 16.

Outlier correction results for the right shoulder joint positions: (a) removing outliers; (b) average interpolation; (c) median filter.

Figure 17.

3D humanoid robot model with 26 DoF.

Figure 17.

3D humanoid robot model with 26 DoF.

Figure 18.

Structure of the proposed 3D pose estimation algorithm.

Figure 18.

Structure of the proposed 3D pose estimation algorithm.

Figure 20.

HPE results using HybrIK (top and middle rows) and MPP (bottom rows) after the proposed preprocessing for five RGB images from the same video shown in

Figure 19.

Figure 20.

HPE results using HybrIK (top and middle rows) and MPP (bottom rows) after the proposed preprocessing for five RGB images from the same video shown in

Figure 19.

Figure 22.

Joint angle profiles calculated by uDEAS from the joint positions estimated by the original HybrIK (red line) and processed HybrIK (blue line), and Vicon angles (black line).

Figure 22.

Joint angle profiles calculated by uDEAS from the joint positions estimated by the original HybrIK (red line) and processed HybrIK (blue line), and Vicon angles (black line).

Table 1.

System Device Specifications and Implementation Environment.

Table 1.

System Device Specifications and Implementation Environment.

OS

CPU

RAM |

Ubuntu 20.04

11th Gen Intel Core (TM) i7-11700 @ 2.50GHzTitle 3

32.0 GB |

GPU

Language |

NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060

Python 3.8 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).